1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the global tourism industry’s sustained expansion, the sector’s significant ecological footprint exerts persistent pressure on natural resource consumption, exacerbates carbon emissions, and complicates waste management challenges [

1,

2]. Within this context, fostering tourists’ pro-environmental behavioral intention (PEBI) has emerged as a critical prerequisite and a vital pathway for sustainable tourism development [

3]. As a direct psychological precursor to individual eco-friendly actions, PEBI not only reflects tourists’ subjective perceptions of environmental responsibility but also governs their propensity to minimize energy consumption, opt for low-carbon transportation, and support green consumption schemes during travel [

4]. Consequently, PEBI is widely regarded as a pivotal psychological linkage connecting environmental awareness, decision-making processes, and the effectiveness of destination governance [

5]. However, existing research has mostly focused on the roles of environmental knowledge, attitudes, or policy interventions [

6]. Growing evidence indicates that sustainable decisions are not formed in isolation but are deeply embedded within dynamic social communication and information environments [

7].

With the rapid evolution of the sharing economy and the advancement of social ecological civilization, Social Media Influencers (SMIs) have emerged as pivotal mediating forces in the context of digital tourism consumption [

8]. Through consistent content creation and interactive engagement, SMIs do not merely reconfigure how tourists acquire information, but also subtly reshape social norms, aspirational identities, and actionable behavioral cues, thereby impacting individual conduct [

9]. Distinct from traditional top-down environmental communication paradigms, SMIs often occupy a dual role as both knowledge disseminators and constructors of social norm. Their influence is deeply rooted in established trust, emotional connection, and the authentic representation of everyday life [

10,

11]. Furthermore, leveraging their expansive reach within digital ecosystems, SMIs increasingly function as framers of public awareness and catalysts for participatory action in sustainability issues [

7,

12]. Although the practical significance of SMIs in sustainability communication is growing increasingly evident [

13,

14,

15], existing theoretical frameworks remain insufficient in explaining how digital influence is trans-formed into multidimensional pro-environmental behavioral intentions and through which underlying psychological mechanisms [

7]. There remains a clear need for more systematic theoretical integration and mechanistic elaboration in this domain.

Three interrelated gaps characterize the existing literature. First, most studies adopt a trait-based analytical approach, treating influencer attributes—such as expertise, attractiveness, or authenticity—as parallel and independent predictors [

10,

11,

16,

17]. This perspective fails to capture how audiences integrate multiple cues to form holistic evaluations of influencers as coherent social agents, particularly in tourism contexts where consumption is experiential, symbolic, and context dependent. Second, prior research has disproportionately emphasized cognitive persuasion mechanisms (e.g., credibility or informativeness) at the expense of relational and identity-based processes. Crucial dynamics central to influencer–follower interactions, such as parasocial relationships (PSR) and wishful identification (WI) remain underexamined [

11,

18,

19]. Consequently, the psychological internalization processes through which sustainability-related messages are transformed into concrete behavioral intentions remain insufficiently theorized. Third, pro-environmental behavior is often treated as a homogeneous outcome. Existing studies tend to prioritize offline behavioral intentions while neglecting digitally mediated forms of environmental participation [

20,

21], such as online pro-environmental advocacy and sustainability-related word-of-mouth [

7]. Moreover, limited attention has been paid to socioeconomic heterogeneity—particularly education and income—as boundary conditions shaping individuals’ cognitive resources and perceived behavioral feasibility, implicitly assuming that influencer effects are socially uniform [

12,

13].

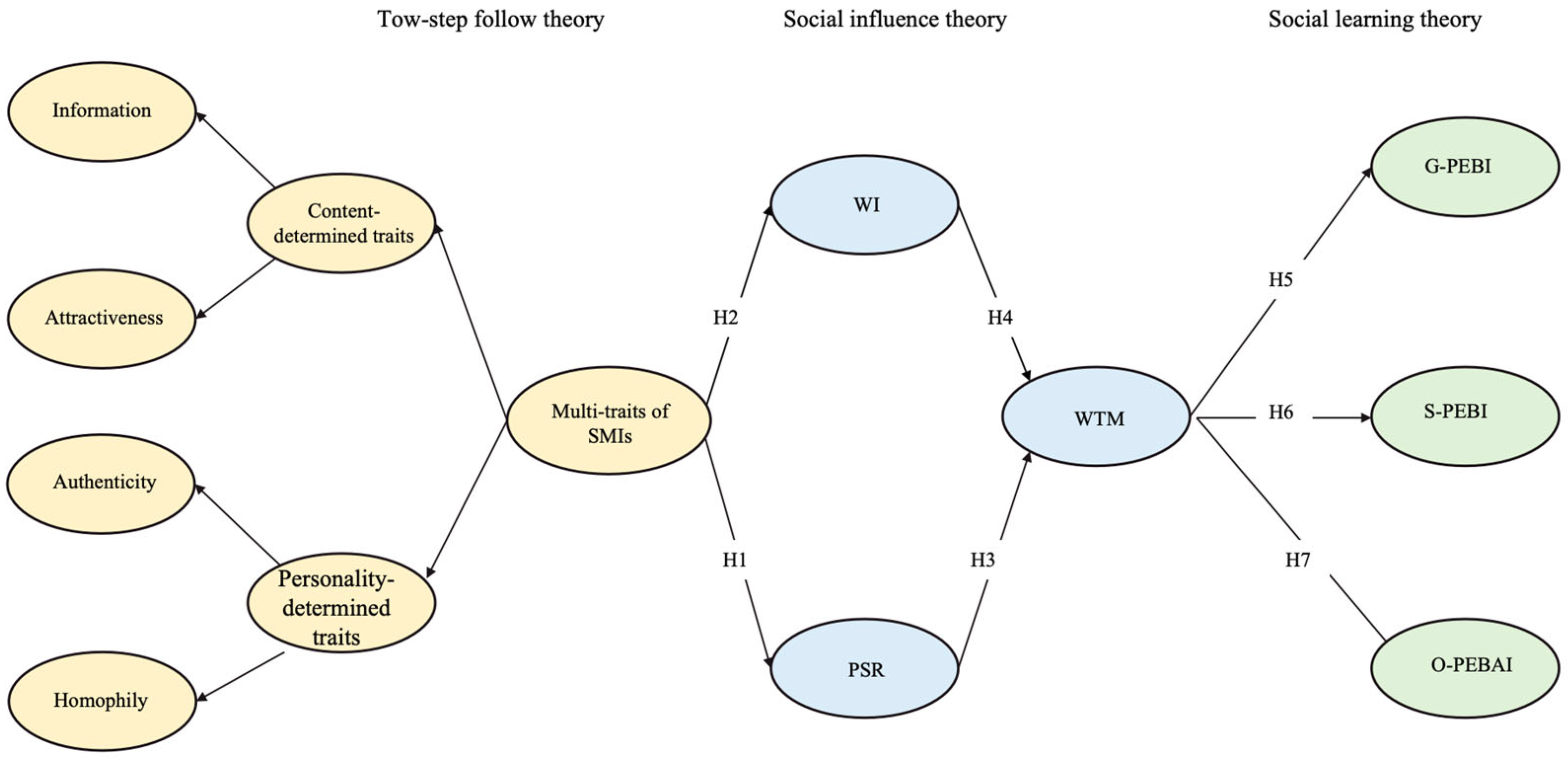

To address these interconnected gaps, this study integrates two-step flow theory, social influence theory, and social learning theory to construct a sequential mediation model elucidating influencer-driven pro-environmental intention formation. Specifically, the multi-traits of SMIs are conceptualized as a hierarchical, multidimensional construct, capturing audiences’ integrated evaluations of influencers as coherent social agents. The proposed model further explicates how these consolidated traits cultivate parasocial relationships and wishful identification, which jointly activate individuals’ willingness to mimic. This mimetic motivation subsequently serves as a pivotal mechanism, subsequently driving multiple dimensions of pro-environmental behavioral intention, including general, travel-specific, and online advocacy intentions. In addition, this study examines whether the efficiency of these psychological transformation pathways is conditioned by socioeconomic characteristics, particularly education and income, thereby identifying the theoretical boundaries under which influencer-driven sustainability communication operates. By transcending fragmented trait-based explanations and average-effect assumptions, this research offers a more systematic and context-sensitive theoretical framework. It reveals how social media influencers activate pro-environmental behavioral intentions through psychologically mediated and socially differentiated processes, thereby advancing scholarship on digital influence and sustainable tourism communication.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Social Media Influencers’ Multi-Traits

Social media influencers (SMIs), as a contemporary form of opinion leaders in the digital era, derive their influence from audiences’ holistic evaluations of their multiple traits rather than from any single attribute in isolation [

16,

17]. In tourism consumption contexts, these traits can be systematically conceptualized as SMI multi-traits—an integrated evaluative system formed through audiences’ synthesis of content-related attributes (e.g., attractiveness, information quality) and personality-related attributes (e.g., authenticity, homophily) [

5,

22]. This integrated perception constitutes the theoretical foundation of influencer effectiveness and serves as a core driver of influence in digitally mediated environments [

10,

23].

With the evolution of social media, influencers have become hybrid digital actors who simultaneously perform the roles of opinion leaders, content creators, and symbolic lifestyle representatives [

11,

18,

24]. Prior studies consistently demonstrate that influencer-related traits shape audience trust, attitudinal responses, and behavioral intentions. These traits include the perceived usefulness and relevance of information, the consistency and sincerity of self-presentation, aesthetic and interpersonal appeal, and perceived value congruence between influencers and followers [

11,

25]. Rather than operating independently, such traits interact dynamically and are cognitively integrated by audiences, making influencer influence inherently relational, cumulative, and affect-laden rather than purely informational [

11].

From a theoretical perspective, two-step flow theory provides a robust foundation for understanding this integrated evaluation process [

10]. The theory posits that information does not flow directly from media to audiences but is filtered and interpreted through opinion leaders who function as key intermediaries. In digital tourism communication contexts, SMIs assume precisely this mediating role [

26]. Their influence stems not from isolated trait cues but from audiences’ ongoing and systematic evaluation of their multidimensional characteristics [

26,

27]. Through repeated exposure, observation, and interaction, followers synthesize fragmented trait information into a coherent overall judgment regarding an influencer’s credibility, resonance, and persuasive potential [

16,

25,

28,

29,

30]. This process supports conceptualizing SMI multi-traits as a higher-order, multidimensional construct, reflecting a unified object of audience evaluation rather than a checklist of discrete attributes.

Despite this theoretical relevance, existing research remains limited in two important respects. First, many studies operationalize influencer traits as parallel and independent predictors [

11,

16,

19,

31,

32], overlooking their potential hierarchical structure and integrated nature within the two-step flow mechanism [

11]. Second, empirical inquiry has predominantly focused on commercial consumption settings, leaving public-interest domains—such as sustainable tourism—relatively underexplored [

9,

33]. In particular, there is insufficient theoretical explanation of how integrated evaluations of influencer traits translate into tourists’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions through psychological mechanisms. To address these gaps, this study moves beyond a fragmented trait-based perspective and reconstructs SMI multi-traits as a higher-order integrated construct encompassing both content-driven and personality-driven attributes.

Building on this integrated trait framework, the study further examines how holistic evaluations of SMIs activate followers’ parasocial relationships and wishful identification, thereby facilitating the psychological internalization of sustainability-related messages. Through these dual pathways, influencer-driven communication enables the transformation of externally presented environmental meanings into self-relevant motivations, laying the groundwork for willingness to mimic and subsequent pro-environmental behavioral intentions. In doing so, this framework not only advances influencer theory but also provides a coherent theoretical basis for understanding how influencer-based communication operates as a psychologically embedded mechanism in sustainable tourism contexts.

2.2. Parasocial Relationship, Wishful Identification and Willingness to Mimic

Grounded in social influence theory, the persuasive power of social media influencers is primarily realized through psychologically mediated processes rather than direct informational persuasion [

10,

11]. Among these processes, parasocial relationships (PSR) and wishful identification (WI) constitute two closely related yet conceptually distinct mechanisms through which audiences internalize influencer-driven messages [

10,

11,

16,

18].

Parasocial relationships refer to one-sided but emotionally meaningful bonds that audiences develop with media figures, characterized by perceived intimacy, familiarity, and pseudo-social interaction [

34,

35]. In social media environments, such relationships are cultivated through continuous content exposure, interactive affordances, and consistent self-presentation, which together foster a sense of virtual reciprocity and relational closeness [

25,

36]. Prior research has demonstrated that parasocial relationships enhance trust, facilitate message acceptance, and increase susceptibility to influence [

10,

19,

37]. This relational bond is further strengthened when influencers share similar values, lifestyles, or worldviews with their followers—a condition often described as homophily [

38,

39]. In the context of sustainable tourism communication, parasocial relationships play a critical role in transforming environmental messages from abstract or distant information into personally relevant and emotionally resonant guidance, thereby establishing the affective foundation for subsequent motivational processes.

Building upon parasocial relationships, wishful identification represents a deeper level of psychological engagement in which audiences perceive influencers as embodiments of their ideal selves [

10]. Unlike simple admiration, wishful identification involves aspirational self-alignment, whereby followers desire to emulate the values, lifestyles, and behavioral patterns displayed by influencers [

11]. Through this process, sustainability-related cues embedded in influencer content are no longer perceived as external norms but become integrated into individuals’ self-concept [

11,

18]. In tourism consumption contexts—where behaviors are closely tied to identity expression and lifestyle choice—wishful identification is particularly salient [

12]. When influencers model responsible travel practices, followers may cognitively and emotionally position such behaviors as desirable, attainable, and identity-consistent [

11], thereby strengthening pro-environmental behavioral intentions [

40].

However, psychological connections and identification alone are insufficient to produce behavioral outcomes [

11]. Willingness to mimic (WTM) serves as a crucial conversion mechanism that bridges psychological internalization and behavioral intention formation [

16]. Drawing on social learning theory, willingness to mimic reflects individuals’ conscious motivational readiness to reproduce observed behaviors after evaluating their desirability and feasibility [

41,

42]. Once trust has been established through parasocial relationships and values have been internalized via wishful identification, individuals assess influencer-modeled behaviors as viable reference points for action [

16,

43]. In this sense, willingness to mimic operationalizes observational learning by translating psychological engagement into action-oriented motivation.

2.3. Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intentions in Tourism Consumption Contexts

Pro-environmental behavior (PEB) broadly refers to actions that minimize environmental harm and contribute to sustainable development [

44]. In the tourism literature, PEB has been widely discussed under related labels such as environmentally responsible behavior, sustainable behavior, and green behavior, all of which reflect individuals’ behavioral orientations toward mitigating the negative environmental impacts of tourism activities [

45,

46].

Early conceptualizations emphasize that PEB represents a coherent set of actions aimed at reducing environmental degradation and, in some cases, generating positive ecological outcomes [

44]. Empirical studies have operationalized PEB across multiple domains, including recycling, energy conservation, transportation choices, sustainable purchasing, and waste management [

2,

21,

45,

47]. As tourism intensifies pressures on destination ecosystems, scholars increasingly recognize that tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviors play a pivotal role in balancing tourism development and environmental protection [

48,

49].

A critical refinement in tourism research is the distinction between general pro-environmental behavior and situation-specific pro-environmental behavior [

50,

51]. General pro-environmental behavioral intention (G-PEBI) reflects individuals’ habitual environmental orientations and everyday environmentally friendly practices, whereas situation-specific pro-environmental behavioral intention (S-PEBI) captures context-dependent behaviors enacted during travel, such as complying with environmental regulations, minimizing ecological disturbance, and engaging in environmentally responsible activities at destinations l [

20,

21]. This distinction acknowledges that environmental behavior is not uniform across contexts and that tourism settings impose unique situational constraints and opportunities for sustainable action l [

21].

Beyond offline behaviors, sustainable tourism outcomes increasingly depend on the diffusion of environmental norms through digital communication [

52]. In this regard, online pro-environmental advocacy intention, commonly conceptualized as sustainability-related online word-of-mouth (WOM), represents an important yet underexplored dimension of PEB. Online WOM refers to individuals’ intentions to share, recommend, or advocate environmentally responsible practices through social media platforms [

12,

53]. From a sustainability perspective, such digital advocacy constitutes a meaningful form of pro-environmental participation by reinforcing social norms, extending the reach of sustainability messages, and mobilizing collective environmental engagement [

54].

Importantly, the theoretical connotation of online environmental advocacy behavior extends beyond the consumer perspective of traditional word-of-mouth marketing [

23]. It represents individuals’ orientation toward environmental value expression and social participation through digital platforms [

55]. In the digital era, this persuasive function increasingly manifests through low-threshold online actions, such as liking, reposting, commenting on, and disseminating sustainability-related content [

14]. Within tourism consumption contexts, online pro-environmental advocacy therefore reflects individuals’ willingness to participate in digitally mediated environmental communication rather than merely expressing private attitudes or offline intentions [

54].

Taken together, contemporary tourism sustainability research suggests that pro-environmental engagement should be conceptualized as a multidimensional outcome, encompassing general behavioral intentions, travel-specific behavioral intentions, and online advocacy intentions. However, existing studies have paid limited attention to how these different forms of pro-environmental behavioral intention are jointly activated through social influence processes in digital environments [

7]. In particular, the mechanisms through which social media influencers translate digital exposure into offline and online sustainability-oriented intentions remain insufficiently theorized.

Building on this perspective, the present study integrates general pro-environmental behavioral intention, travel-specific pro-environmental behavioral intention, and online pro-environmental advocacy intention as three complementary outcome variables. By examining how social media influencers activate willingness to mimic through psychologically mediated pathways, this study develops a comprehensive framework to explain how digital influence is transformed into multidimensional pro-environmental behavioral intentions within tourism consumption contexts.

2.4. Hypotheses Development

Synthesizing the above literature, this study conceptualizes influencer-driven sustainability communication in tourism as a psychologically mediated and sequential process. Drawing on two-step flow theory, social influence theory, and social learning theory, the proposed framework explains how social media influencers (SMIs) translate their integrated personal and content-related traits into followers’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions through layered psychological mechanisms.

From a two-step flow perspective, SMIs function as contemporary opinion leaders who interpret, frame, and transmit sustainability-related meanings to audiences in an accessible and socially resonant manner [

10,

28,

29]. Rather than exerting influence through isolated attributes, influencers are evaluated holistically as social agents, with their multi-traits operating as an integrated external stimulus [

10,

19,

56]. Social influence theory further suggests that such evaluations shape individuals’ judgments and behavioral tendencies by activating relational bonds and normative cues embedded in influencer–follower interactions [

57]. In this context, parasocial relationships (PSR) capture followers’ perceived intimacy and emotional trust toward influencers, whereas wishful identification (WI) reflects aspirational self-alignment with influencers’ values and lifestyles [

42].

Building on these perspectives, this study posits that SMIs’ multi-traits strengthen both PSR and WI, which together constitute complementary psychological pathways of influence [

10,

11,

16,

18]. While PSR emphasizes relational closeness and WI highlights identity projection. These psychological responses, however, do not directly result in behavioral outcomes. Consistent with social learning theory, willingness to mimic (WTM) is conceptualized as a proximal motivational state that bridges psychological internalization and behavioral intention formation [

10,

18]. Through observational learning and evaluative judgment, followers assess the desirability and feasibility of influencer-endorsed practices, forming a readiness to emulate such behaviors [

10,

42]. The theoretical framework proposed in this study essentially constructs an expanded S-O-R (stimulus-organism-response) model to systematically elucidate the mechanism through which social media influencers exert their influence in sustainable tourism communication. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1. Social media influencers’ multi-traits positively influence followers’ parasocial relationships.

H2. Social media influencers’ multi-traits positively influence followers’ wishful identification.

H3. Parasocial relationships positively influence individuals’ willingness to mimic social media influencers.

H4. Wishful identification positively influences individuals’ willingness to mimic social media influencers.

Extending this psychological-to-behavioral logic, this study adopts a multidimensional view of pro-environmental behavioral intention. Pro-environmental engagement is expected to manifest across daily life, tourism consumption contexts, and digital interaction spaces. Willingness to mimic, as the final conversion mechanism, is therefore hypothesized to translate influencer-driven motivation into three distinct yet related forms of pro-environmental behavioral intention: general pro-environmental behavioral intention, specific pro-environmental behavioral intention, and online pro-environmental advocacy intention. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5. Willingness to mimic positively influences general pro-environmental behavioral intention.

H6. Willingness to mimic positively influences specific pro-environmental behavioral intention.

H7. Willingness to mimic positively influences online pro-environmental advocacy intention.

Finally, consistent with prior research in sustainable tourism and green consumption [

13,

58], education, and socio-demographic variables—including age, education, and income—are included as control variables to account for potential confounding effects on pro-environmental behavioral intentions. The research model is presented in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

All measurement items used in this study were adapted from well-established scales that have been widely validated in prior tourism, sustainability, and social media influencer research. Minor wording modifications were applied to ensure contextual relevance to tourism consumption and pro-environmental travel contexts. All constructs were operationalized as multi-item reflective measures.

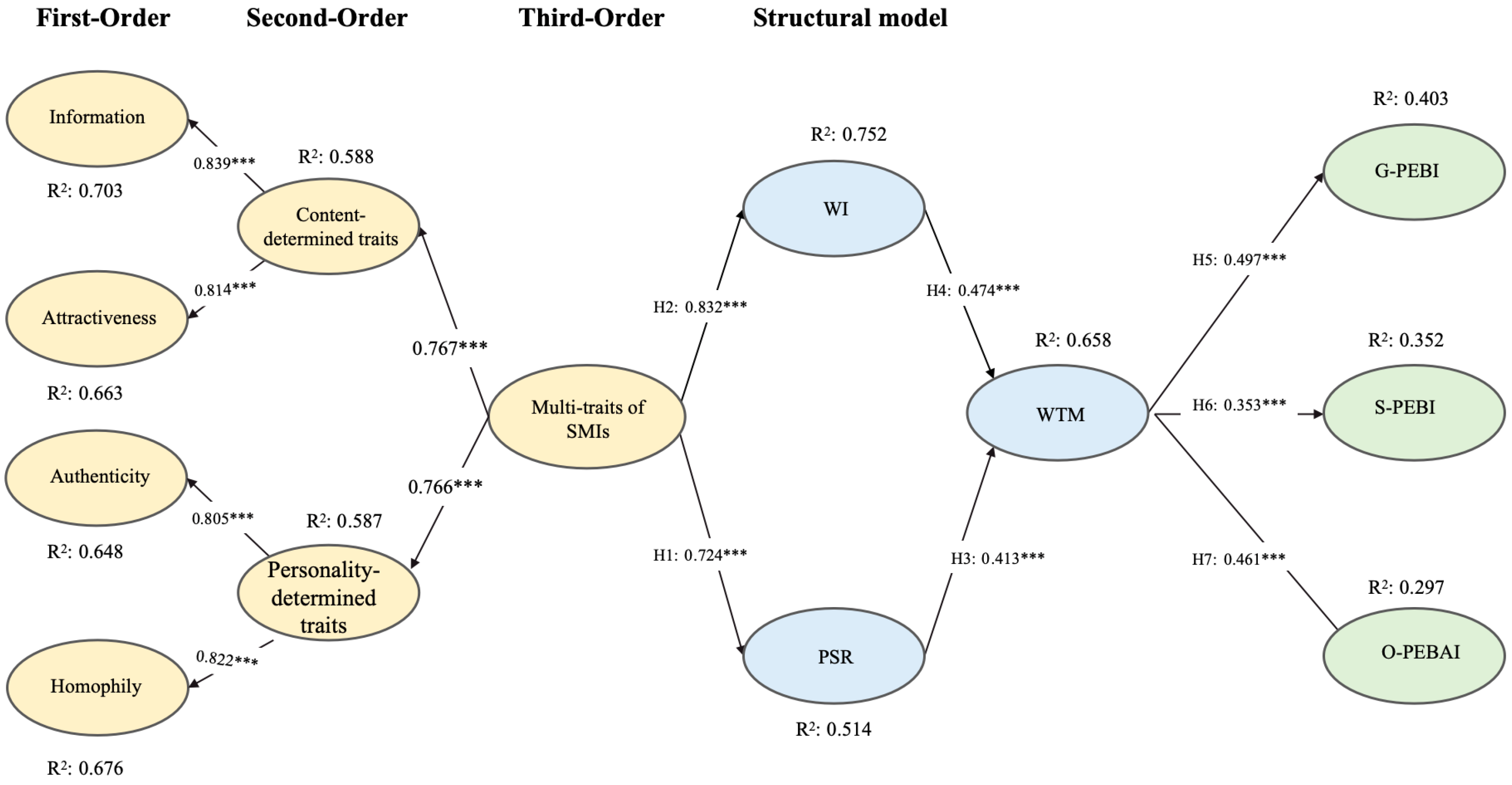

Consistent with the proposed conceptual framework, social media influencers’ (SMIs’) multi-traits were modeled as a hierarchical multi-trait construct. Specifically, TSMIs’ multi-traits were conceptualized as a third-order reflective construct, comprising two second-order dimensions—content-determined traits and personality-determined traits—which were further reflected by four first-order traits: information, attractiveness, authenticity, and homophily. A total of 15 items were adapted from Kim and Kim (2021) [

16] and Lou and Kim (2019) [

25], with minor contextual refinements to fit the tourism influencer setting.

Followers’ psychological responses to TSMIs were captured through parasocial relationship (PSR) and wishful identification (WI). Measurement items for PSR and WI were adapted from Hu et al. (2020) [

18] and Cheung et al. (2022) [

10], respectively, reflecting affective bonding and aspirational self-alignment with travel influencers.

Willingness to mimic TSMIs (WTM) was measured using items adapted from Ki and Kim (2019) [

16] and Chloe Ki et al. (2022) [

11]. Following expert recommendations, the original lifestyle-oriented mimicry items were reworded to emphasize eco-friendly and responsible travel-related behaviors, while preserving their core meaning of aspiration-based imitation. This adjustment ensured conceptual consistency between influencer-driven mimicry and sustainability-oriented behavioral outcomes in tourism consumption context.

Regarding outcome variables, this study explicitly operationalized all behavioral outcomes at the intention level, rather than as direct observations of realized behaviors. Accordingly, three outcome constructs were specified: general pro-environmental behavioral intention (G-PEBI), travel-specific pro-environmental behavioral intention (S-PEBI), and online pro-environmental advocacy intention (O-PEBAI).

General pro-environmental behavioral intention (G-PEBI) captures respondents’ general readiness to engage in environmentally responsible actions and information-related behaviors beyond specific travel contexts. Travel-specific pro-environmental behavioral intention (S-PEBI) reflects respondents’ intentions to adopt environmentally responsible practices within tourism and travel scenarios. Measurement items for both constructs were adapted from Wu et al. (2022) [

51] and Qin and Hsu (2022) [

59], capturing both habitual and context-specific environmentally responsible intentions relevant to tourism consumption context.

Online pro-environmental advocacy intention (O-PEBAI) represents respondents’ intention to engage in digital environmental advocacy related to tourism sustainability, including content sharing, reposting, recommendation, and persuasion behaviors on social media platforms. Consistent with prior sustainability communication research, online advocacy is treated as a distinct form of pro-environmental behavioral intention that operates through symbolic influence and normative signaling rather than direct resource consumption. Measurement items were adapted from Ki and Kim (2019) [

16] and Dhanesh and Duthler (2019) [

60]. All items were measured using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A complete list of measurement items is provided in

Appendix A.

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling Context

Data for this study were collected via a self-administered online questionnaire using Wenjuanxing (

www.wjx.cn), a professional online survey platform in China. The platform was responsible for recruiting eligible participants in accordance with predefined screening criteria, and the survey link was distributed through social media channels and tourism-related online communities.

To ensure that the proposed model was tested explicitly under a tourism consumption scenario rather than a general social media context, several screening and contextualization procedures were implemented at the questionnaire design stage. First, only respondents aged 18 years or above who provided informed consent were allowed to proceed with the survey. Second, respondents were required to be active social media users and to report that they followed at least one travel-related social media influencer (TSMI). Third, respondents must have been exposed to tourism- or sustainability-related influencer content within the past six months and must have had at least one travel experience within the previous year. These criteria were designed to ensure meaningful cognitive and behavioral exposure to tourism-related influencer content and to minimize recall bias.

Rather than evaluating a hypothetical or artificially assigned influencer, respondents were instructed to recall a real travel social media influencer whom they actively followed and considered representative of their typical exposure. All subsequent measurement items referring to “the influencer” were anchored to this recalled individual, thereby capturing authentic parasocial interaction, identification, and mimicry processes grounded in respondents’ actual media consumption experiences.

The survey context primarily reflected mainstream Chinese social media platforms commonly used for tourism-related content consumption, including TikTok (Douyin), Bilibili, Weibo, Xiaohongshu (Red Book), and WeChat. These platforms differ in affordances such as content format, interaction intensity, and algorithmic recommendation mechanisms; however, all enable repeated exposure to travel-related narratives, visual storytelling, and pro-environmental messaging. By anchoring respondents’ evaluations to their primary platform of use, the study captures tourism influencer effects as they naturally occur across dominant digital tourism media ecosystems in China.

Given that the original measurement items were developed in English, a back-translation procedure was employed to ensure linguistic equivalence. Prior to data collection, the translated questionnaire was reviewed by five academic experts specializing in tourism and marketing to verify content clarity and semantic consistency. A pilot test with 100 respondents was conducted before the formal survey, and the results indicated satisfactory reliability and clarity, requiring no further revisions.

The formal data collection was conducted between July and December 2022 using an anonymous, non-invasive online survey. At the time of data collection, all participants were provided with a detailed informed consent statement, participation was voluntary, no personally identifiable information was collected, and responses were analyzed only in aggregate form. After excluding responses that failed attention checks, did not meet screening criteria, originated from non–mainland China IP addresses, or were incomplete, a total of 598 valid responses were retained for subsequent data analysis. Preliminary analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (Version 25; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) was performed using AMOS (Version 24; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3.3. Research Methods

The multi-traits of social media influencers were modeled as a third-order reflective construct in this study. This specification is grounded in the theoretical premise that the perceived effectiveness of an influencer represents an underlying latent evaluation that manifests through multiple interrelated traits, rather than a simple aggregation of independent attributes. Consistent with social influence theory and social learning theory, followers tend to form a holistic judgment of an influencer, whereby dimensions such as information quality, attractiveness, authenticity, and homophily co-vary and jointly reflect an overall perception of influence effectiveness.

Accordingly, the reflective specification assumes that changes in the higher-order latent construct are expected to induce simultaneous changes across its lower-order dimensions, and that these dimensions are conceptually interchangeable manifestations of the same underlying evaluation [

61,

62,

63]. This assumption is appropriate in the context of tourism-related influencer perception, where followers typically do not compartmentalize influencer traits in isolation, but instead evaluate them as an integrated influence system.

The third-order reflective construct was estimated using covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) with the repeated indicators approach [

63]. Specifically, all observed indicators of the first-order constructs were assigned to the corresponding higher-order latent constructs, allowing for simultaneous estimation of the measurement and structural models within a single SEM framework. This approach preserves measurement error, avoids information loss associated with factor score estimation, and has been widely adopted in prior research for estimating higher-order reflective constructs. Model identification and estimation followed established CB-SEM guidelines, and the adequacy of the measurement model was evaluated before proceeding to the structural model analysis [

64,

65].

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in

Table 1. The sample consisted of 52.17% female and 47.83% male participants. Regarding age, most respondents were between 18 and 25 years (35.12%) and 26–33 years (36.96%), followed by those aged 34–41 years (17.73%), while 10.20% were over 41 years old. In terms of occupation, students (31.61%) constituted the largest group, followed by self-employed respondents (15.72%) and company staff (14.38%). Regarding educational attainment, more than half of the respondents held a bachelor’s degree or above (58.86%). Concerning income, a monthly income above RMB 4000 represented the largest category (52.01%). Beyond basic socio-demographic characteristics, respondents demonstrated substantial engagement with travel-related social media content and tourism influencer interactions. As shown in

Table A2 and

Table A3 in

Appendix B, a large proportion of respondents reported frequent exposure to TSMIs’ content, following multiple travel influencers, and actively engaging with tourism-related posts through liking, commenting, reposting, and forwarding. Importantly, all respondents reported having adopted recommendations provided by travel-related social media influencers (TSMIs), and all indicated having visited destinations recommended by travel influencers at least once. These behavioral patterns confirm that the sample represents individuals with meaningful and repeated exposure to tourism influencer content, thereby supporting the validity of situating the proposed model within a tourism consumption context.

4.2. Measurement Model Analysis

This study conceptualizes social media influencer multi-traits (SMIs’ multi-traits) as a third-order reflective latent construct to capture respondents’ holistic evaluations of travel-related social media influencers. Within the covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) framework, the higher-order structure was estimated using the repeated indicators approach, which enables the simultaneous estimation of the measurement and structural models.

The initial measurement specification included five first-order dimensions. During model evaluation, however, the indicators intended to capture expertise exhibited extremely high inter-item correlations and estimation instability under the CB-SEM framework. To ensure proper model identification and empirical stability, the expertise dimension was excluded from the final measurement model. Accordingly, the finalized SMIs’ multi-traits construct comprises four first-order dimensions: information, attractiveness, authenticity, and homophily.

These four dimensions were hierarchically organized into two second-order factors—content-driven traits and personality-driven traits—which were further represented by a third-order latent construct capturing overall influencer multi-traits. For model identification, the path from the third-order construct to one second-order factor was fixed to unity, while all remaining paths were freely estimated.

All retained indicators demonstrated significant and substantial standardized factor loadings (λ > 0.70, p < 0.001). The higher-order paths were also highly significant (β = 0.974–0.987), supporting the internal coherence of the hierarchical structure. The third-order submodel exhibited excellent fit (χ2/df = 1.173; CFI = 0.984; RMSEA = 0.017), indicating satisfactory representation of the data. The full measurement model showed good overall fit (χ2/df = 1.132; CFI = 0.996; RMSEA = 0.015).

As shown in

Table 2, skewness and kurtosis values were within acceptable ranges, supporting the normality assumption [

66]. Standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.70 for all items, average variance extracted (AVE) values were above 0.50, and both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values exceeded 0.70, indicating satisfactory internal consistency and convergent validity [

67]. As shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4, discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratios, both of which met conservative thresholds [

68,

69]. These results indicate that the measurement model is reliable, valid, and empirically stable, providing a solid foundation for subsequent structural model analysis.

4.3. Common Method Bias

As shown in

Table 5, common method bias was assessed using two complementary approaches. First, Harman’s single-factor test revealed that the first factor accounted for 31.9% of the total variance, which is below the recommended threshold of 50% [

70]. Second, consistent with Liang et al. (2007) [

71], the average substantive variance (0.6217) was substantially greater than the average method-based variance (0.0826), yielding a ratio of approximately 7:1. This indicates that common method bias does not pose a serious threat to the validity of our results.

4.4. Structural Model Analysis

The structural model demonstrated excellent fit to the data (χ

2 = 1167.884, df = 629

p < 0.000, χ

2/df = 1.857; GFI = 0.915; AGFI = 0.900; NFI = 0.920; IFI = 0.962; TLI = 0.957; SRMR = 0.077; RMSEA = 0.038; PCLOSE = 1.000), meeting the recommended thresholds for model fit [

72]. As shown in

Table 6 and

Figure 2, both content-determined traits (β = 0.767,

p < 0.001) and personality-determined traits (β = 0.766,

p < 0.001) significantly contributed to the higher-order construct of SMI multi-traits. Furthermore, SMI multi-traits exerted significant positively influences parasocial relationship (β = 0.724,

p < 0.001) and wishful identification (β = 0.832,

p < 0.001), thereby supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2. In turn, both parasocial relationship and wishful identification positively influence willingness to mimic: parasocial relationship (β = 0.413,

p < 0.001) and wishful identification (β = 0.474,

p < 0.001), providing support for Hypotheses 3 and 4, respectively. Moreover, willingness to mimic was found to positively influence individuals’ G-PBEI (H5: β = 0.497,

p < 0.001), S-PEBI (H6: β = 0.353,

p < 0.001), and O-PEBAI (H7: β = 0.461,

p < 0.001), thus confirming Hypotheses 5, 6, and 7.

The model accounted for substantial variance in key constructs: 51.4% in parasocial relationships, 58.8% in content-determined traits, 58.7% in personality-determined traits, and 65.8% in willingness to mimic. It also explained 40.3% of the variance in G-PEBI, 35.2% in S-PEBI, and 29.7% in O-PEBAI, indicating strong explanatory power. These findings corroborate the proposed psychological linkage mechanism, the multi-traits of social media influencers foster affective bonds—through parasocial relationship and wishful identification—which subsequently activate willingness to mimic, ultimately driving both offline and online pro-environmental behavioral intentions. This provides robust theoretical evidence for our conceptual framework.

4.5. Mediation Effect

To test the hypothesized mediation effect, we conducted a bootstrap analysis with 5000 resamples using the bias-corrected percentile method. As show in

Table 7 all indirect effects were statistically significant (

p < 0.05), with 95% confidence intervals that did not include zero. Specifically, the total indirect effect of SMI multi-traits on willingness to mimic was β = 0.694, 95% CI [0.620, 0.754]. This effect was transmitted through two parallel psychological pathways: parasocial relationship (β = 0.299) and wishful identification (β = 0.394). Furthermore, willingness to mimic significantly mediated the influence of SMI traits on three behavioral intentions: G-PEBI (total indirect effect = 0.345, 95% Bica CI [0.266, 0.421]), S-PEBI (0.245, [0.168, 0.325]), and O-PEBAI (0.320, [0.230, 0.420]). These results support a sequential mediation process in which emotional bonding with influencers translates into behavioral intentions through the mechanism of willingness to mimic. These results validate the sequential mediation model, SMI multi-traits foster affective bonds (via parasocial relationship and wishful identification), which activate mimicry motivation, ultimately translating into diverse pro-environmental behavioral intentions.

4.6. Control Variable Effects and Robustness Checks

To further explore whether demographic characteristics directly influence behavioral intentions, this study regressed the control variables on the outcome variables to assess their effects. The results revealed meaningful differences in how digital influencer effects translate into pro-environmental behaviors. Specifically, age exerted significant negative effects on general pro-environmental behavioral intention (β = −0.252,

p < 0.001), specific pro-environmental behavioral intention (β = −0.193,

p < 0.001), and online word-of-mouth (WOM) intention (β = −0.095,

p < 0.05). Educational level showed positive effects on general behavioral intention (β = 0.059,

p < 0.01) and online WOM (β = 0.232,

p < 0.001), whereas income negatively predicted specific behavioral intention (β = −0.304,

p < 0.001) and online WOM (β = −0.152,

p < 0.01). In contrast, gender and occupation did not exhibit significant effects across any of the behavioral outcomes (see

Table 8).

Although age demonstrated consistent negative effects across all three pro-environmental behavioral intentions, educational level and income exhibited heterogeneous influence patterns—these two demographic variables showed inconsistent effects on different behavioral outcomes in the structure model. These differential patterns suggest potential heterogeneity in the psychological mechanisms through which social media influencers’ traits translate into environmental actions across socioeconomic groups. Given this observed inconsistency, we conducted multi-group structural invariance tests based on education and income levels to examine the robustness of the proposed theoretical pathways across distinct subgroups. Grouping criteria were defined as follows: education: High = Bachelor’s degree or above (

n = 376); Low = Below Bachelor’s (

n = 222); income: High ≥ ¥4001 per month (

n = 294); Low ≤ ¥4001 per month (

n = 304). Given these differential impacts, we examined whether the structural relationships in our model varied between high- versus low-education and high- versus low-income groups. First, we tested overall model equivalence by comparing unconstrained models (all parameters freely estimated) with fully constrained models (all structural parameters constrained to be equal across groups). As shown in

Table 9, chi-square difference tests were significant for both education (Δχ

2 = 51.961, Δdf = 7,

p < 0.001) and income (Δχ

2 = 43.790, Δdf = 7,

p < 0.001), indicating that the two groups differ significantly at the model level.

We then conducted path-by-path structural invariance tests by constraining each structural coefficient to be equal across groups and evaluating the resulting change in model fit (Δχ

2). As reported in

Table 10 and

Table 11, several key paths differed significantly between groups. For example, the effect of SMI multi-traits on wishful identification was stronger among low-education individuals (β = 0.955) than among high-education individuals (β = 0.635), whereas the effect of parasocial relationships on willingness to mimic was more pronounced in the high-education group (β = 0.564) than in the low-education group (β = 0.196). For income level, the path from SMI traits to parasocial relationship was stronger in the high-income group (β = 0.843) than in the low-income group (β = 0.438), and the path from willingness to mimic to online environmental advocacy was also stronger among high-income respondents (β = 0.634 vs. 0.411). These findings suggest that the psychological mechanisms linking social media influencers’ traits to pro-environmental behaviors are not uniform across socioeconomic groups. While the overall theoretical framework holds, the strength—and in some cases, the direction—of specific pathways varies systematically with education and income, highlighting the importance of contextual factors in understanding digital influence dynamics.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study investigates how social media influencers (SMIs) shape pro-environmental behavioral intentions within tourism consumption contexts through psychologically mediated mechanisms. By systematically deconstructing the dynamic interplay among influencer traits, internalization–transformation processes, and socioeconomic boundary conditions, this research offers several theoretical contributions to the literature on digital influence and sustainable tourism.

First, this study conceptualizes SMI multi-traits as a hierarchical third-order reflective construct, transcending prior approaches that treat influencer characteristics as isolated evaluative cues. By integrating content-driven dimensions (e.g., information and attractiveness) and personality-driven dimensions (e.g., authenticity and homophily), this higher-order construct captures individuals’ holistic cognitive evaluations of tourism-focused influencers rather than fragmented perceptions of discrete attributes. This conceptualization aligns with the core premises of two-step flow of communication theory and holistic impression formation theory, both of which emphasize that influencer effectiveness stems from integrated cognitive representations rather than from single attributes in isolation, these findings extend the results of previous single-trait studies [

16,

17,

25].

Notably, while expertise is traditionally viewed as a distinct dimension, it did not emerge as an independent factor in the present tourism-related social media context. This finding implies that within experiential and consumption-oriented domains like tourism, perceived expertise is cognitively embedded within information quality. In such contexts, audiences appear to infer expertise implicitly through cues related to the usefulness, relevance, and clarity of content rather than through explicit signals of professional credentials, this finding differs from previous research results [

11,

17,

18]. This insight deepens understanding of the contextual sensitivity of influencer credibility assessments and highlights that in non-technical, high-involvement consumption settings, expertise operates in an implicit and integrative manner.

Second, by integrating two-step flow of communication theory, social influence theory, and social learning theory, this study establishes a unified framework that clarifies the dynamic “internalization–transformation” mechanism underlying SMI effectiveness. The results demonstrate that SMIs do not rely solely on direct persuasion, rather, their multi-traits activate a sequential psychological process in which parasocial relationships (reflecting emotional trust and relational bonding), and wishful identification (reflecting aspirational self-alignment) jointly enhance willingness to mimic. This willingness functions as a proximal motivational state, bridging digital exposure with pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Theoretically, this sequence explicates how sustainability messages are transformed from external stimuli into internalized motivations and subsequently into behavioral intentions through three interrelated stages: relationship formation, value internalization, and action readiness. By empirically modeling this chain of mediation, the study extends existing theories S-O-R (stimulus-organism-response) by illustrating how digital influence facilitates the internalization of environmental values and their translation into behavioral intentions in social media–mediated tourism contexts [

11,

16].

Third, multi-group analyses reveal that education level and personal income constitute critical socioeconomic boundary conditions that systematically shape the effectiveness of this psychological mechanism. From an educational perspective, the findings indicate a substitution of psychological pathways rather than a simple difference in susceptibility to influencer effects. Individuals with lower educational attainment demonstrate a heightened reliance on influencers’ observable multi-traits to form wishful identification, and this aspirational alignment plays a dominant role in activating mimicking intentions. In contrast, higher-educated individuals exhibit a stronger conversion from parasocial relational bonds to mimicking willingness, suggesting that influence among this group is more strongly grounded in perceived relational authenticity and credibility rather than idealized self-projection. This pattern refines social influence theory by demonstrating that internalization routes vary across educational levels, aspirational identification is more salient when cognitive and media literacy resources are limited [

1], whereas relational trust becomes the key driver when audiences possess greater reflective and evaluative capital [

9]. Consequently, education conditions are not the existence of influence per se, but the specific psychological routes and behavioral expressions through which influencer-driven sustainability communication becomes effective [

13].

Furthermore, income level conditions the downstream expression of mimicking motivation, particularly in distinguishing between offline pro-environmental behavioral intentions and online advocacy intentions. These findings are consistent with previous research: income levels significantly influence individuals’ pro-environmental behaviors [

2,

4]. While higher-income individuals show a stronger translation of willingness to mimic general and travel-specific pro-environmental behavioral intentions, lower-income individuals are more inclined to convert mimicking motivation into online pro-environmental advocacy. This divergence suggests that economic resources shape not only the feasibility of action but also the preferred mode of behavioral expression. Offline pro-environmental practices often entail time, financial capital, or opportunity costs, making them more accessible to individuals with greater economic flexibility, whereas online advocacy provides a lower-cost channel through which environmentally motivated individuals can express support, signal eco-identity, and participate symbolically.

Taken together, the education- and income-based heterogeneity identified in this study advances a nuanced conceptualization of influencer-driven sustainability communication as a contingent behavioral activation architecture. This architecture reveals a dual-layered stratification, education primarily differentiates which psychological mechanism activates mimicking (aspirational versus relational), whereas income governs how mimicking motivation is behaviorally manifested (offline action versus online advocacy). These findings extend two-step flow theory and social learning theory by highlighting that opinion leadership and observational learning do not operate through a single universal pathway, but through socially stratified mechanisms reflecting differences in cognitive resources and material constraints. Consequently, influencer effectiveness in sustainability contexts should be understood as mechanism-sensitive and context-dependent rather than inherently scalable or universally transferable across audiences [

73]. By moving beyond average effects, this study advances sustainable communication theory toward a more refined understanding of heterogeneity in digital influence mechanisms.

5.2. Managerial Implications

The findings of this study offer several actionable implications for sustainability communication and tourism governance in digital environments, particularly for social media influencers, destination management organizations (DMOs), and public-sector stakeholders seeking to promote pro-environmental behavioral intentions among tourists.

First, regarding SMIs, the results underscore the importance of positioning sustainability communication beyond factual persuasion and toward relational and aspirational engagement. The identified sequential mechanism indicates that influencers are most effective when their sustainability-related content fosters parasocial relationships and wishful identification, thereby activating willingness to mimic. In practice, influencers should prioritize consistent self-presentation, authenticity, and value congruence rather than overt expertise signaling. Since perceived expertise is cognitively embedded within information quality, explicit professional credentials are less critical than the delivery of clear, relevant, and experience-based content. Consequently, influencers should integrate environmental messages organically into relatable travel narratives and aspirational lifestyles, rather than framing sustainability as a rigid technical requirement or moral obligation.

Second, for destination management organizations and tourism marketers, the observed heterogeneity across education and income groups highlights the necessity for precision marketing and differentiated segmentation strategies rather than uniform influencer campaigns. For audiences with lower educational attainment, where influencer traits predominantly drive wishful identification, suggesting that campaigns targeting these segments may benefit from visually engaging and emotionally resonant influencers who embody accessible and desirable travel identities. In contrast, higher-educated audiences rely more heavily on parasocial bonds when translating influencer exposure into mimicking intentions, indicating that DMOs should collaborate with influencers who emphasize transparency, narrative depth, and long-term relationship building. Income-based heterogeneity further reveals channel-specific patterns in the conversion of mimicking motivation into pro-environmental intentions. Higher-income individuals demonstrate a robust translation of mimicking motivation into offline, travel-specific pro-environmental behaviors, likely reflecting greater financial flexibility, access to sustainable options, and perceived behavioral control. In contrast, lower-income individuals are more inclined to express influencer-induced motivation through online pro-environmental advocacy, such as sharing and recommending sustainability-related content, which offers a lower-cost and more accessible mode of participation. From a managerial perspective, these findings caution against one-size-fits-all influencer strategies and call for audience-sensitive campaign designs that align content formats and behavioral prompts with socioeconomic conditions.

Third, at the macro-level of public sustainability communication and digital governance, the findings challenge the “one-size-fits-all” assumptions underlying many influencer-based environmental campaigns. The evidence that influencer-driven intention formation is socially contingent suggests that platform-level guidelines and public–private partnerships should support audience-sensitive content design. The empirical evidence that influencer-driven intention formation is socially contingent necessitates a shift in platform-level guidelines and public–private partnerships toward audience-adaptive content design. Policymakers and sustainability advocates may leverage influencers as strategic intermediaries for environmental education and online advocacy, while remaining cautious about equating digital engagement with actual behavioral change. Given that this study focuses on intention-based outcomes, influencer marketing should be viewed as a tool for motivational activation rather than a substitute for structural or policy interventions. To effectively narrow the gap between pro-environmental intentions and real-world action, influencer communication should be integrated with supportive infrastructures, such as accessible sustainable services, clear behavioral prompts, and institutional incentives.

5.3. Conclusions

Positioned within a tourism consumption context, this study advances understanding of how travel-related social media influencers (SMIs) function as psychologically embedded intermediaries that activate pro-environmental behavioral intentions in the digital era. Drawing on an integrative framework combining two-step flow theory, social influence theory, and social learning theory, the study conceptualizes SMIs’ characteristics as a hierarchical multi-trait construct and empirically examines a sequential mechanism linking influencer traits to followers’ relational and aspirational psychological responses, willingness to mimic, and multiple forms of pro-environmental behavioral intention, including general, specific, and online advocacy intention. The findings provide consistent support for a mechanism-based explanation of influencer effectiveness in sustainable tourism communication.

The multi-group analyses further demonstrate that this intention-formation process is socially contingent rather than uniform. Education and income systematically condition the extent to which influencer-driven psychological mechanisms translate into pro-environmental and advocacy-oriented intentions, indicating that identical influencer traits and persuasive functions may yield differentiated motivational outcomes across socio-economic segments. This result underscores the importance of recognizing socioeconomic boundary conditions when assessing the effectiveness of influencer-based sustainability communication.

Overall, this study positions SMIs’ multi-dimensional traits and relational mechanisms as a scalable architecture for activating pro-environmental behavioral intentions in tourism consumption contexts, while emphasizing that such influence is psychologically mediated and socially differentiated rather than universally uniform. These insights contribute to a more nuanced understanding of digital influence processes in sustainable tourism and offer a foundation for developing more targeted and context-sensitive sustainability communication strategies.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations for future research. First, this study relies on self-reported survey data and intention-based outcome measures rather than observed pro-environmental behaviors. Although behavioral intention is widely recognized as a strong and theoretically meaningful predictor of actual behavior in sustainability research, intention–behavior gaps may still exist, particularly in tourism contexts where situational constraints and opportunity costs vary across individuals. Future studies may benefit from incorporating behavioral tracking data, experimental designs, or longitudinal approaches to examine whether and how influencer-induced intentions translate into sustained pro-environmental actions over time [

1,

6]. Second, although this study models social media influencers’ multi-traits as a hierarchical construct and examines key psychological mediators, it does not explicitly account for platform-specific affordances or content-format characteristics (e.g., short videos versus long-form posts, algorithmic exposure, or interactive features). Such platform-level factors may shape how influencer traits are perceived and how psychological engagement is formed. Future research could integrate platform characteristics, content strategies, or algorithmic visibility into the analytical framework to further refine understanding of how digital environments condition influencer effectiveness in promoting pro-environmental intentions [

15]. Third, the empirical data were collected from social media users in China, which may limit the cross-cultural generalizability of the findings. Social media ecosystems, influencer–follower dynamics, and norms surrounding environmental responsibility differ across cultural and institutional contexts. While the present study provides valuable insights into influencer-driven sustainability communication in an emerging digital tourism market, future research should replicate and extend the proposed model in different cultural settings or conduct cross-national comparative studies to assess the robustness and contextual sensitivity of the identified psychological mechanisms. Expertise characteristics were used as valid measurement in previous studies, that the absence of expertise may limit generalizability to contexts where technical knowledge is paramount (e.g., health or finance) and call for cross-context comparisons in future research.