Abstract

This research examines the influence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) strategies on corporate financial performance (CFP) in China’s automotive industry, characterized by intense regulatory pressure and fast-paced technological transformation. Using an unbalanced panel dataset of A-share listed automotive firms from 2009 to 2024, this paper combines ESG scores from the Huazheng ESG index with firm-level financial data from CSMAR. CFP is measured through both accounting-based (ROA) and market-based (Tobin’s Q) indicators. Panel regression models are applied to evaluate the influence of overall ESG performance and the three individual pillars, and to assess heterogeneity across ownership types, firm type, and firm age. The results show that ESG performance is significantly and positively associated with ROA, but is insignificantly associated with Tobin’s Q. It is suggested that ESG engagement improves accounting profitability but is not fully reflected in the capital market. Among the three ESG pillars, governance shows the strongest positive link with ROA, while environmental and social performance are weakly associated with ROA. Furthermore, the heterogeneity study shows that the positive relationship between ESG and CFP is more pronounced for non-state-owned firms, vehicle manufacturers, or mature firms. Overall, this paper presents fresh evidence on whether and how ESG initiatives can facilitate sustainable value in China’s automotive sector, offering insights for policymakers and management that may help this industry achieve sustainable growth.

1. Introduction

In recent years, global concern for ESG performance has increased significantly, with more countries incorporating ESG issues into their national development strategies [1]. ESG provides a multidimensional framework for evaluating corporate behavior along environmental, social, and governance dimensions [2], and its performance metrics serve as an institutionalized mechanism that aligns firms’ economic objectives with wider social and regulatory expectations [3]. As the world’s second-largest economy, China has incorporated ESG principles into a series of top-down regulatory and industrial policies that directly shape firms’ strategic and operational decisions. The ‘dual carbon’ policy, for instance, which was put forward in 2020, aims to achieve a national carbon emission peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 [4,5]. To attain these goals, China’s State Council [6] has released the ‘2024–2025 Energy Conservation and Carbon Reduction Action Plan’, which specifies detailed and quantifiable carbon reduction requirements across industries. In the automotive industry, this plan explicitly mandates that at least 80% of newly added or upgraded urban buses, taxis, and logistics vehicles must be new-energy vehicles (NEVs). Consequently, for firms in the automotive industry, ESG engagement is no longer discretionary but has become a determinant of their financial performance.

In China, the automotive industry acts as an essential driver for economic growth [7]. This industry has rapidly transformed and expanded over the past two decades, driven by technological advancements, government subsidies, and demand growth [8]. Meanwhile, Chinese automakers face increasing pressure to adopt ESG strategies not only to meet regulatory requirements and social expectations but also to maintain competitiveness in both global and domestic markets [9]. Accordingly, this dual pressure of regulatory compliance and market competition makes the automotive industry a theoretically meaningful setting to examine how ESG engagement translates into CFP. Despite the growing literature on ESG and firm performance in China’s automotive sector, several critical gaps remain. First, the existing literature rarely examines how the three ESG pillars operate through different economic mechanisms, leaving unclear why certain dimensions matter more than others for financial performance. Second, most studies rely on static correlation-based analyses and pay limited attention to how institutional conditions and firm characteristics shape heterogeneous relationships between ESG and CFP.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to investigate the relationship between ESG practices and CFP within the Chinese automotive industry. Firstly, this paper will investigate whether ESG performance primarily affects accounting-based performance, market-based valuation, or both. Second, this paper will examine whether the environmental, social, and governance pillars operate through different channels and exhibit divergent effects on CFP. Finally, this study will analyze how ownership structure, firm type, and firm age affect the effectiveness of ESG strategies, and thereby reveal the institutional mechanisms behind heterogeneous outcomes. By answering these questions, the study clarifies why ESG engagement in a transition industry may improve accounting performance without being fully reflected in market valuation.

The remaining sections are structured as follows. Section 2 reviews theoretical frameworks, analyzes existing empirical studies, and develops hypotheses. Then, Section 3 elaborates on the data selection and methodology. Section 4 reports regression results on the impact of overall ESG performance and its three individual pillars on CFP, and further explores the heterogeneity in ownership structure, firm type, and firm age on the ESG-CFP relationship. Next, Section 5 discusses the main findings and their corresponding implications. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the key findings, underscores limitations, and suggests directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. ESG Strategies

The notion of ESG originated in the 1970s, when a small group of investors began paying attention to the environmental and social practices of the firms in which they placed their capital [10], and is based on the studies of corporate social responsibility (CSR) [11]. Unlike CSR practice, which relies on qualitative narratives, ESG performance depends on quantitative indicators, allowing for systematic comparisons of companies and industries. In this sense, standardization makes ESG a powerful tool for regulators, investors, and scholars to consistently and effectively assess corporate behavior.

ESG as a concept is a combination of three separate dimensions, which are environment (E), social (S), and governance (G) [12]. The environmental aspect refers to the company’s impact on the natural environment, including emissions, resource use, and pollution. The social factor describes how a company deals with its employees, customers, suppliers, and other stakeholders, which practically refers to human capital, product responsibility, supply chain, social contribution, and data security. Governance depicts a company’s governance, which concentrates on the structures, policies, leadership accountability, ethics, and stakeholder rights.

At present, there are different ESG rating institutions around the globe, such as MSCI, LSEG, Bloomberg, and Huazheng, which lead to an inconsistent ESG assessment system. This inconsistency would result in divergence in ESG scores at the firm level, which is often viewed as a form of market uncertainty. Notably, evidence suggests that ESG rating divergence serves as a negative signal that hinders corporate resource allocation and reduces investment efficiency through both under- and over-investment channels [13]. Such inconsistency may change the sign and magnitude of the estimation results [14]. To mitigate noise caused by global-local rating discrepancies, the ESG rating compiled by Huazheng is adopted in this study. This index offers the most complete coverage of Chinese A-share-listed businesses. Unlike other international rating agencies, which predominantly focus on large-cap firms in their global indices, Huazheng covers all listed firms on the Chinese stock exchanges. This extensive coverage minimizes sample selection bias and ensures that our analysis captures the ESG performance of small and medium-sized enterprises. Additionally, Huazheng’s methodology is tailored to the unique institutional context of the Chinese market, incorporating localized metrics, such as poverty alleviation, and distinct environmental compliance standards that other agencies often overlook [15]. The detailed depiction of the rating system is illustrated in Table A1 in Appendix A.

2.2. Corporate Financial Performance

CFP reflects a company’s overall financial health and its ability to create value for shareholders by effectively utilizing available resources [16]. In academia, factors that can enhance firms’ financial level have always been closely researched, and there are several theoretical perspectives that provide insights into how firms can enhance their financial performance. Based on stakeholder theory, it is suggested that firms could enhance operational stability and long-term financial profitability by reducing conflicts, improving stakeholder satisfaction, and strengthening relationships by considering the interests of multiple stakeholders [17]. Legitimacy theory and reputation theory point out that if organizations conform to social norms and demonstrate responsible behavior to society, they are more likely to gain social recognition and win a positive reputation [18,19]. Such legitimacy and reputational advantages help attract high-quality employees, loyal customers, and long-term investors, thereby reinforcing a firm’s financial performance. In addition, the resource-based view claims that firms can achieve better financial performance by acquiring valuable, scarce, and inimitable resources, including superior human capital and innovative capabilities [20]. Integrating these theoretical perspectives, ESG practices can be regarded as an effective strategy to improve CFP, since effective ESG implementation could enhance stakeholder satisfaction, bolster legitimacy and reputation, and acquire scarce resources [21,22]. Accordingly, superior ESG performance is expected to be positively associated with CFP, primarily through improvements in operational efficiency and market trust.

Furthermore, CFP captures both firms’ internal operational efficiency and external market evaluation. Existing studies generally classify CFP measures into accounting-based and market-based indicators [23]. In detail, accounting-based indicators reflect internal profitability and resource utilization efficiency. Typical examples are Return on Assets (ROA), Return on Equity (ROE), and earnings per share, while market-based indicators reflect external evaluations and investors’ expectations of a firm’s performance in capital markets. Stock annual returns, the market-to-book ratio, and Tobin’s Q (TQ) are commonly used examples [24]. In this paper, ROA and TQ are employed to represent accounting-based and market-based financial performance, respectively. ROA is the rate of the company’s operational efficiency, showing the net income generated by its assets, and is a favorable measure of internal profitability [25]. Market-based performance is measured by Tobin’s Q, the ratio of a firm’s market value to the replacement cost of its assets. This ratio indicates shareholders’ perceptions of the company’s growth potential and the value of intangible assets [26]. Together, these two indicators allow us to examine whether ESG engagement affects firms through operational channels, valuation channels, or both.

2.3. The Impact of ESG and Corporate Financial Performance

Existing empirical research reports mixed evidence on the relationship between ESG engagement and CFP. Some researchers have shown that ESG engagement facilitates firm growth by improving operational efficiency, strengthening stakeholder relationships, and encouraging innovation [2,27,28,29]. Consistently, the meta-analytic study by Friede, Busch, and Bassen [30] reports that, although results vary, the existing literature indicates a predominantly positive correlation between ESG and firm performance, with substantial heterogeneity across industries, performance measures, and research designs. Other scholars, however, contend that ESG engagements may exert limited or even negative effects on CFP when the associated costs exceed potential profits [31,32,33]. For instance, Krüger [34] indicated that ESG activities may yield adverse or negligible financial effects when they involve excessive expenditures or are perceived by stakeholders as symbolic “greenwashing”. Moreover, some papers show that ESG activities generate positive effects mainly in the short term, primarily through reputation enhancement and signaling effects [35]. In contrast, another stream of literature argues that the benefits of ESG are more likely to materialize in the long run, as firms become more resilient and develop sustainable competitive advantages [36,37,38]. Firm-level analyses by Eccles, Ioannou, and Serafeim [21] further show that firms with stronger sustainability practices tend to outperform peers in both accounting-based and market-based indicators, suggesting that ESG initiatives can generate both short-term operational gains and long-term valuation benefits. Hence, such mixed results underscore that the financial consequences of ESG engagement are highly context-dependent and sensitive to institutional environments, industry characteristics, and measurement choices.

Compared with developed markets, the relationship between ESG engagement and CFP in emerging economies remains underexplored. This is especially true in China, where regulatory reforms and rapid industrial transformation have created a unique institutional environment for corporate sustainability practices. China’s automotive industry, one of the most carbon-intensive and policy-sensitive sectors, provides an ideal setting to examine how ESG engagement operates under intense governmental supervision aimed at reducing emissions and accelerating the transition to NEVs. Theoretically, ESG participation in this industry is expected to enhance CFP primarily through operational efficiency improvements and strengthened relationships with key stakeholders. Existing empirical evidence in China provides only partial and inconclusive support for this expectation. For example, Wang and Law [39] reported that listed automotive firms with higher ESG performance exhibit superior financial outcomes, while Chen [40] believes that ESG investments may reduce short-term profitability but generate positive economic returns in the long run. Despite these findings, there remains no consensus on how and through which channels ESG practices affect financial performance in China’s automotive industry. Given the mixed evidence, this study develops hypotheses to examine how ESG engagement affects both accounting-based and market-based financial performance in China’s automotive sector:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

ESG performance has a significantly positive effect on the CFP of Chinese automotive firms.

Decomposing ESG into its environmental, social, and governance dimensions is essential for identifying the distinct economic mechanisms through which ESG engagement affects CFP. Prior studies suggest that after disaggregating ESG, the governance dimension tends to exert the most important influence on accounting-based performance, since strong governance improves decision-making efficiency and risk management effectiveness; in contrast, environmental and social improvements often impact financial performance indirectly or conditionally, depending on industry-specific risk, regulatory pressure, and stakeholder engagement [41,42]. In other words, governance improvements can more directly enhance operational efficiency and thereby improve financial performance, while environmental and social initiatives may require a longer time or a favorable institutional environment to achieve some financial returns. However, existing research on the Chinese automotive industry tends to treat ESG as a single composite score and rarely distinguishes between the three pillars, each of which may exert distinct effects on CFP. In this case, three hypotheses are proposed below to bridge the existing gap by separately examining the influence of each ESG dimension:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Environmental performance has a significantly positive effect on the CFP of Chinese automotive firms.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Social performance has a significantly positive effect on the CFP of Chinese automotive firms.

Hypothesis 2c (H2c).

Governance performance has a significantly positive effect on the CFP of Chinese automotive firms.

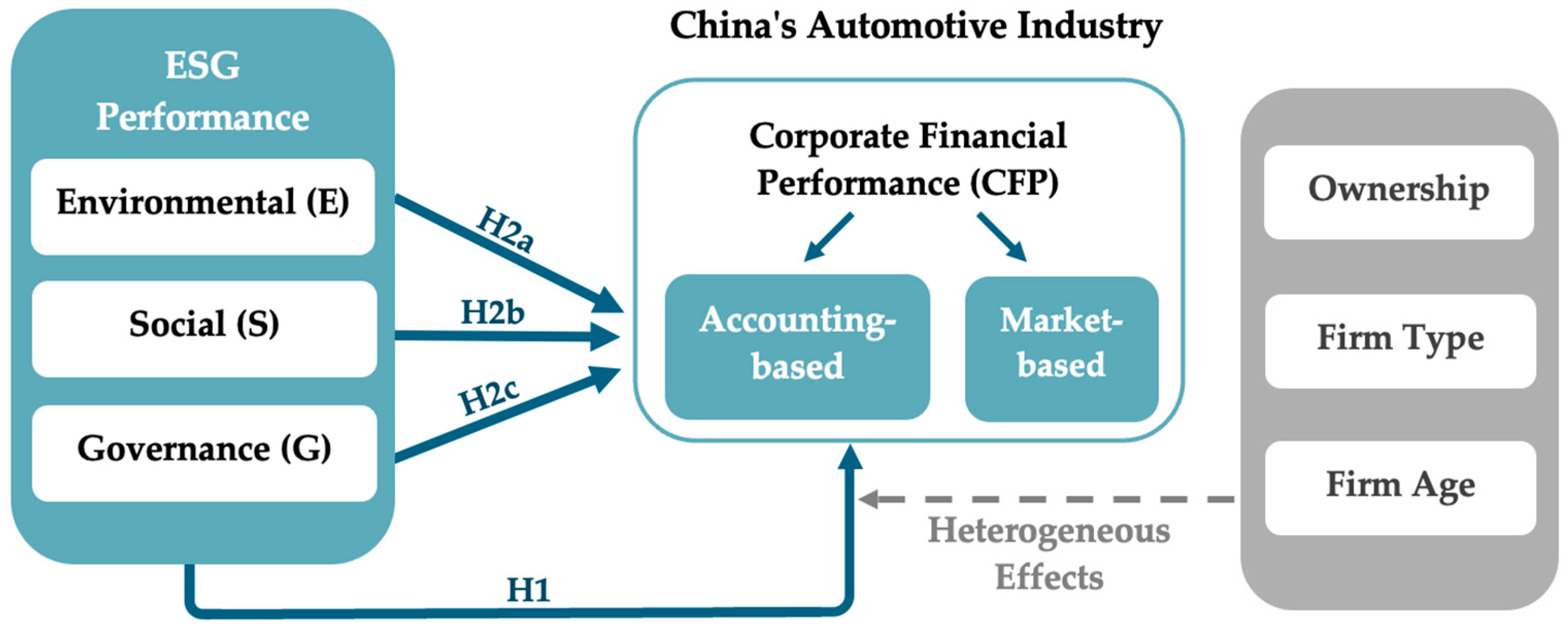

Figure 1, shown below, illustrates the conceptual framework of this study, which highlights how ESG performance and its individual pillars relate to accounting-based and market-based CFP in China’s automotive industry. Ownership, firm type, and firm age are considered sources of heterogeneity in this relationship.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Selection

The empirical analysis for this paper utilizes panel data from Chinese automobile manufacturing companies from 2009 to 2024. ESG performance data were obtained from the ESG database of Huazheng, one of the largest index providers for the Chinese capital markets. The ESG data in this database can be traced back to 2009, which allows us to construct the longest possible panel for Chinese listed firms. Notably, the period starting from 2009 coincides with the gradual institutionalization of environmental regulation and corporate sustainability practices in China, making it a meaningful starting point for examining the ESG and CFP relationship [43]. The end year, 2024, is chosen to capture recent developments in China’s ESG regulations and the automotive industry’s rapid shift toward new energy vehicles, ensuring our analysis reflects the latest policy and market conditions. The firm-level financial data were obtained from the CSMAR (China Stock Market and Accounting Research) database. The sample data of A-share listed automotive companies in China encompass both automotive manufacturing firms and auto parts supplying firms. There are a total of 1775 panel data entries from 192 listed companies.

In particular, this paper adopts an unbalanced panel dataset. The unbalanced structure arises naturally due to firm entry and exit in the capital market. Maintaining an unbalanced panel helps preserve the characteristics of the sample and avoids survivorship bias that could result from forcing a balanced panel. Panel data estimators, such as fixed-effects and random-effects estimators, are robust to unbalanced situations, which guarantees the reliability and consistency of inference.

To maintain the quality of the data, companies with missing or conflicting values in key variables were excluded from the final sample. Additionally, all variables were winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels to reduce the influence of extreme values, except for the firm size (SIZE), the logarithm of firms’ total assets, which was retained due to its stable nature. The statistical analyses in this report were conducted using STATA 18.0.

3.2. Variables Construction

For dependent variables, ROA and Tobin’s Q are utilized as the representative of CFP, which represent both accounting-based and market-based financial performance indicators.

In terms of independent variables, ESG performance was represented by the score of an aggregate ESG as well as its three individual pillars. The ESG composite score captures a firm’s overall sustainability engagement, while sub-dimensional scores measure the differential impacts of environmental, social, and governance practices on financial outcomes.

With respect to control variables, firm size (SIZE), measured as the natural logarithm of total assets, is used to control for scale effects. Leverage (LEV), the ratio of total debt to total assets, is set to capture the impact of firms’ capital structure and financial risk. Growth (GROWTH) is measured as the percentage change in total revenue and serves as an indicator of a firm’s expansion potential. The specific descriptions of all variables are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The definitions and descriptions of variables.

3.3. Baseline Model Specification

Based on the above framework, the following regression models are employed to test the H1:

For the H2a, the model is constructed as follows:

For the H2b, the model is constructed as follows:

For the H2c, the model is constructed as follows:

In these models, subscripts i and t denote firm and year, respectively. refers to firm fixed effects; represents year fixed effects; is the idiosyncratic error term.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

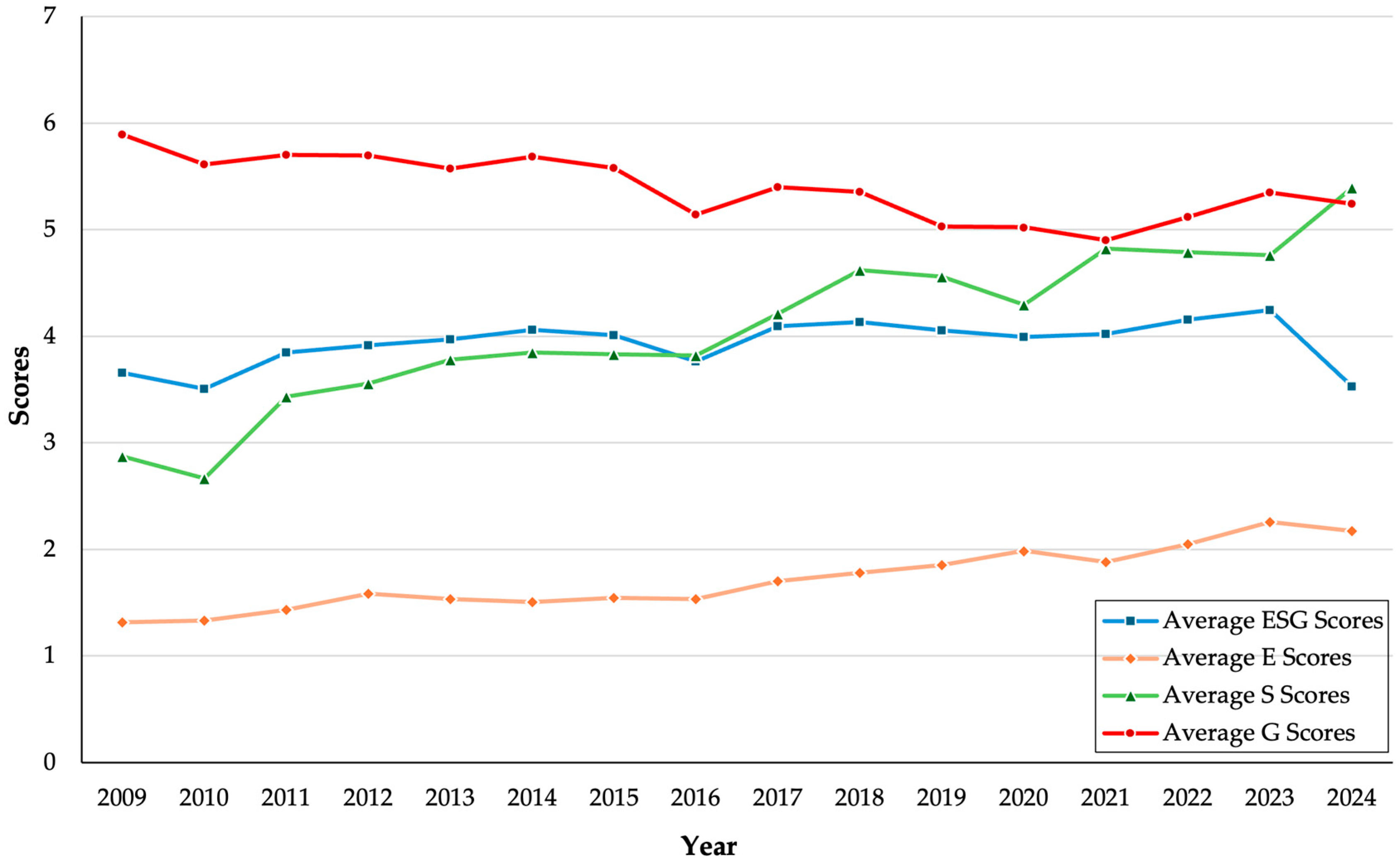

The descriptive statistical results for all variables are shown in Table 2. As shown in the following table, the mean ROA is 0.035, and the standard deviation is 0.055, indicating that firms’ accounting-based profitability varies moderately. In addition, Tobin’s Q (TQ) has a mean of 1.675, suggesting that the market value of corporations is approximately 1.7 times their book value. Notably, a small number of firms report that their TQ values are close to zero. These observations generally arise from severe financial distress, low market valuation, or trading suspensions. Zotye Auto in 2015 and Baling in 2014 and 2017 could exemplify such cases, in which persistent losses and regulatory scrutiny resulted in impaired market prices. Thus, these data were retained but winsorized at 1% level to reduce the influence of extreme values. Regarding overall ESG performance, the average ESG score is 3.962, implying that the overall ESG engagement of the sample companies is at a medium level. With respect to those three components, the governance pillar (G) shows the highest mean score (5.308), followed by the social pillar (S) at 4.35 and the environmental pillar (E) at 1.817. It is suggested that Chinese automotive firms tend to prioritize corporate governance and social responsibility over environmental practices, as seen in Figure 2, where the G scores are mostly above the S scores and then the E scores.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of main variables.

Figure 2.

Average annual ESG scores and component scores (E, S, G) for listed Chinese automotive firms, 2009–2024.

In terms of the control variables, firm size (SIZE), indicating the size of an organization’s operations, varies moderately across observations, with a mean of 22.336 and a range of 19.892 to 26.487. In addition, the leverage (LEV), which reflects the capital structure and financial risk, has a mean value of 0.455 and a sample range of 0.086 to 0.945. This suggests that there are relatively huge differences in financial limitations between observations. Additionally, revenue growth (GROWTH), which demonstrates a firm’s operational ability and marketing performance, has a relatively high standard deviation of 3.021 and a mean growth rate of −18.2%. It is implied that there are significant variations in the growth dynamics of different enterprises. Overall, the descriptive results present a prominent distinction in financial performance and ESG engagement among listed Chinese automotive firms.

4.2. Correlation Results

The Pearson correlation matrix, presented in Table 3, reveals the relationship among the variables used in this study, including financial performance indicators (ROA and TQ), ESG scores (ESG, E, S, and G), and control variables (SIZE, LEVERAGE, and GROWTH). ESG performance and ROA show a positive correlation (r = 0.253, p < 0.01), indicating that companies with higher ESG scores tend to have superior accounting-based financial performance. Among these sub-dimensions, the governance score (G) has the largest positive correlation with ROA (r = 0.376, p < 0.01), followed by the environmental (E) and then the social (S) dimensions. This suggests that good governance practices may be essential to increasing a company’s profitability. On the other hand, TQ exhibits a negative association with overall ESG performance (r = −0.100, p < 0.01), suggesting that ESG participation may not always be reflected in market-based corporate valuation.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficient matrix.

In terms of control variables, company size (SIZE) and TQ have a negative correlation (r = −0.337, p < 0.01), which implies that larger companies usually have lower market valuations in relation to their book values. Leverage (LEV) and ROA exhibit a negative correlation (r = −0.043, p < 0.01), and this relationship indicates that businesses with more debt typically report marginally lower profitability. The relationship between ROA and the revenue growth rate (GROWTH) is positive (r = 0.188, p < 0.01), illustrating that faster-growing companies generate higher returns on assets. Furthermore, there exist positive correlations among the sub-dimensions (namely E, S, and G), and their values range from 0.078 to 0.423. This suggests that companies that perform well in one ESG dimension also typically perform well in the others.

4.3. Regression Results

Before the regression test, potential multicollinearity was investigated, and the result suggests low multicollinearity among the explanatory variables. In addition, the Hausman test was used to identify suitable estimators, and the fixed-effects model is preferred. Detailed explanations of pre-regression preparation are provided in Table A2 and Table A3 of Appendix B.

In this study, statistical significance is reported at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels. However, the discussion centers on findings significant at the 5% level or lower, treating the 10% level as indicative of weaker evidence. The panel regression results are presented in Table 4. Panel A and Panel B report fixed-effects estimates for ROA and TQ, respectively. Column (1) in both panels corresponds to H1 and examines the effect of overall ESG performance on CFP. Columns (2)–(4) in these panels present the results for H2a–H2c, showcasing the impact of individual ESG components.

Table 4.

Estimation of panel regression coefficient.

For the overall ESG score, the results indicate that superior ESG performance could increase accounting-based profitability, as reflected by a positive and significant coefficient on ESG in the ROA regression (β = 0.0049, p < 0.01). In contrast, ESG performance does not show a statistically significant effect on TQ (p > 0.1). Although ESG and TQ display a significant association in the Pearson correlation matrix, this relationship weakens after controlling for additional firm-level factors, suggesting that the correlation may be absorbed by other firm-level elements.

Among the three ESG pillars, governance (G) exerts strongest positive and statistically significant influence on firm accounting performance (β = 0.0044, p < 0.01), followed by the social (S) pillar (β = 0.0022, p < 0.05), and the environmental (E) pillar shows the weakest yet still positive effect (β = 0.0027, p < 0.1). In contrast, none of the ESG components display statistically significant impacts on TQ.

Regarding the control variables, their effects are mixed. Firm size (SIZE), in all ROA regressions, consistently yields a positive and significant coefficient, but it exerts a negative and significant influence on TQ in all specifications. Leverage (LEV) shows the opposite pattern, and it depresses ROA while strongly promoting TQ. These contrasting effects suggest that accounting- and market-based performance capture different aspects of financial outcomes. Moreover, a higher growth rate (GROWTH) predicts better ROA across all specifications but shows no statistically significant association with TQ.

4.4. Robustness Check

To further ensure the robustness of these models, a one-year lag of the ESG variable was introduced to re-estimate the model. Considering that ESG initiatives typically take time to influence firms’ operational and financial outcomes, the use of one-period lagged ESG performance could help mitigate potential endogeneity concerns arising from reverse causality and contemporaneous shocks. The lagged models are specified as follows:

In addition, replacing ROA with return on equity (ROE) and replacing TQ with market-to-book ratio (M/B) is an alternative way to test whether the results are robust across different profitability indicators. The models are shown as follows:

The results in Table 5 illustrate that one-period lagged ESG is still positive in the ROA regression, with a coefficient of 0.0028, significant at the 5% level. The magnitude is close to the baseline estimate, suggesting that ESG continues to enhance firms’ accounting performance over time. Similarly, in the ROE regression, it is indicated that the coefficient (0.0123) is positive and significant. This value is slightly larger than that in the baseline model, indicating ESG is more strongly associated with ROE than with ROA. Furthermore, in the regression of TQ and M/B, their coefficients are both positive but insignificant, which is also in line with the baseline estimation. Thus, for overall ESG, the robustness analyses show effects that are consistent with the baseline results, thereby enhancing the credibility of the main conclusion.

Table 5.

Results for robustness check (overall ESG).

In addition, the same robustness tests were conducted for the three ESG pillars. The detailed results are reported in Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6 of Appendix C. The pillar-level results broadly corroborate the baseline findings, though magnitudes and significance levels differ across pillars. Specifically, Governance (G) remains the most influential pillar. The G component exhibits a strong and significant effect on ROE, with a coefficient of 0.0134, while its lagged impact on ROA is statistically insignificant. This pattern suggests that governance improvements primarily influence financial outcomes through relatively immediate channels, such as enhanced decision-making efficiency and internal controls, resulting in operational gains in the current period rather than delayed effects. By contrast, the social (S) pillar does not indicate significant effects in any specification. The environmental (E) pillar yields a positive coefficient for ROE that is marginally significant (β = 0.0070, p < 0.1), whereas its lagged value does not predict ROA. Moreover, none of the three pillars shows a statistically significant relationship with TQ or M/B. Accordingly, these robustness analyses strengthen the conclusion that corporate governance plays a crucial role in driving accounting performance, primarily through contemporaneous effects. The environmental practices also offer limited and primarily immediate accounting benefits. However, these results reveal that the linkage between the social pillar and corporate performance is sensitive to the specific performance measures employed, suggesting that its effects may be more context-dependent. Finally, these analyses further support the conclusion that there is no detectable association between ESG pillars and market valuation.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Ownership

Theoretically, the ownership structure influences how ESG engagement translates into financial performance, as state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs) differ systematically in terms of reputation incentives and access to policy support [44,45]. Thus, examining ownership heterogeneity helps to assess whether ESG creates financial value primarily through reputation mechanisms and policy support. An investigation of the heterogeneous effect of ownership structure is conducted, and its results are presented in Panel A of Table 6. Column (1) demonstrates the estimated result of SOEs, and column (2) represents those for non-SOEs. As shown in the table, ESG demonstrates positive coefficients for both groups, but the connection is statistically significant solely for non-SOEs (β = 0.0056, p < 0.01). This result suggests that ESG initiatives translate more effectively into financial performance for non-SOEs than for SOEs. One possible explanation is that non-SOEs are more sensitive to market competition and stakeholders’ judgment, so engaging in ESG is an important way to improve reputation and attract investment [46]; conversely, SOEs could obtain implicit governmental support, which may mitigate financial risks and weaken the benefits gained from ESG engagement [47]. Hence, ESG engagement may improve CFP through enhancing reputation rather than relying on implicit governmental assistance.

Table 6.

Results for heterogeneity.

4.5.2. Firm Type

Along the automotive value chain, automotive companies can be divided into two types: vehicle manufacturers and auto parts suppliers. Firm type matters since the financial value of ESG depends on the visibility of corporate actions and the strength of stakeholder responses. In Table 6, Panel B presents the heterogeneity analysis by firms’ categories. Column (1) demonstrates the estimated result of vehicle manufacturers (Vehicle), while column (2) represents those for the auto-part suppliers (Parts). The results indicate that ESG practices have a significant influence on the accounting-based performance of manufacturers (β = 0.0118, p < 0.01), but less significance and smaller effects on parts producers (β = 0.0033, p < 0.05). Vehicle manufacturers are subject to greater public supervision, since their products are closer to the end users. Accordingly, their ESG efforts are more visible to stakeholders and therefore make ESG a more effective instrument for reputation building and demand stimulation [48]. Parts suppliers, on the other hand, mostly operate in B2B markets, where ESG visibility is lower and financial returns take longer to materialize.

4.5.3. Firm Age

Firm age is closely related to resource availability and organizational capability, which determine whether ESG initiatives can be effectively implemented and transformed into financial performance. One common approach in academia to distinguish young and old firms is to use the median as the cut-off point [49]. In our sample, the median age is approximately 25. Thus, firms older than 25 years are classified as mature firms, and those under 25 as young firms. The regression results in Panel C of Table 6 indicate that ESG engagement has a stronger and more significant impact on mature firms, with a coefficient of 0.0053 (p < 0.01), compared to younger firms, where the coefficient is smaller at 0.0042 and is only marginally significant (p < 0.1). This finding supports the resource-based view. Mature companies typically possess more stable resources, well-established governance systems, and greater capacity to implement ESG strategies. These advantages enable mature firms to more effectively convert ESG engagement into financial returns through enhanced credibility, stakeholder trust, and operational efficiency. On the other hand, younger companies may not be able to fully benefit from ESG initiatives because they lack the resources, experience, or stakeholder trust. Similar findings have been reported in prior literature showing that firm age conditions the connection between ESG performance and CFP, with stronger effects observed in older firms [50,51].

5. Discussion

5.1. Results Interpretation

The empirical findings of this study reveal that ESG performance significantly enhances accounting-based financial outcomes (ROA). While this result is broadly in agreement with evidence from previous studies that document a significantly positive linkage of ESG and CFP [21,30], our study extends the literature by showing that this positive effect in China’s automotive industry is concentrated mainly in accounting-based performance rather than market-based valuation. Specifically, there is no statistically significant relationship between market-based valuation (TQ) and ESG performance or its three pillars. This insignificant relationship with TQ suggests that China’s capital market may not yet fully incorporate ESG information into firm valuation. This finding aligns with evidence that the financial markets in emerging economies are less responsive to non-financial disclosures due to insufficient ESG awareness or inconsistent information transparency [52], thereby weakening the signaling and reputational effects. Apart from market inefficiency, investors may remain skeptical of the credibility of ESG disclosures, particularly in the presence of greenwashing concerns and uneven assurance practices [34], which reduce the informational content of ESG signals. Additionally, ESG investments, primarily environmental and social initiatives, often entail longer time horizons, so their economic benefits may materialize with a lag that is not immediately capitalized into market valuation [53]. Moreover, even when ESG engagement is viewed positively, higher discount rates applied to Chinese automotive firms due to policy uncertainty and technology transition risk may offset perceived ESG-related benefits in pricing [54]. Moreover, a comparable outcome is reported in Velte [35], who finds that, in Germany, ESG performance has a positive effect on accounting performance but no impact on market value gains, suggesting that the accounting–market divergence may reflect a broader feature of ESG pricing rather than a country-specific anomaly.

Furthermore, it is found that the governance factor exerts the strongest positive impact on ROA in comparison to environmental and social factors, highlighting the central role of internal governance quality in translating ESG engagement into tangible financial outcomes. These estimation results are consistent with the findings of Khan, Serafeim, and Yoon [41], who illustrated that not all ESG dimensions contribute equally to financial performance, and solely the factors that are material to crucial business operations and stakeholders’ concerns are able to create measurable value. Strong governance can enhance stakeholder trust and operational discipline, therefore promoting short-run CFP [55,56]. In the Chinese automotive sector, governance elements appear particularly important owing to their close connection with state ownership, regulatory compliance, and risk management, while social and environmental initiatives are more difficult to be perceived by stakeholders. A comparable pattern is also observed in the German and Korean automotive markets, as indicated by Velte [35] and Kim, Im & Gim [57], suggesting that the dominance of governance may be a general feature of capital-intensive and regulation-sensitive industries.

The heterogeneity analysis further refines our findings by revealing how institutional conditions shape the relationship between ESG and CFP. The relationship between ESG and CFP is more pronounced among non-SOEs, vehicle manufacturers, and mature firms. This finding indicates that ESG creates greater financial value when market discipline, reputational exposure, and organizational capability are stronger. Specifically, non-SOEs are more likely to improve their reputations and attract outside investment through ESG initiatives because they are more exposed to market competition. SOEs, on the other hand, may rely on government support instead of creating ESG value through the market. Also, vehicle manufacturers gain more reputational benefits from ESG efforts than parts suppliers since their products are more visible to end consumers, reinforcing the role of reputation and signaling channels. Furthermore, mature companies have more resources, experience, and stakeholder trust, which makes it easier for them to turn ESG efforts into financial gains than younger companies.

5.2. Applied Implications

The insignificant effect of ESG on Tobin’s Q implies that the capital market does not fully price ESG information. From a regulatory perspective, this insignificance underscores persistent market inefficiencies and information asymmetries. To address this, policymakers could transition from general disclosure mandates to industry-specific ESG reporting standards for the automotive sector, complemented by third-party assurance, to enable capital markets to more accurately price the long-term value of ESG engagement [58]. Second, the environmental and social practices show a weaker financial influence on CFP. This outcome suggests that, in China’s automotive sector, actions in these two pillars may face weak external incentives and a long payback period, making it hard for firms to obtain measurable benefits. In this case, the government could implement targeted fiscal incentives, such as green tax credits or preferential financing, to mitigate the short-term financial burdens on firms pursuing decarbonization. Meanwhile, management could address this issue by aligning their ESG investments with business goals and by improving communication with stakeholders to clarify the value of their actions. Third, governance acts as the most influential ESG component. Strengthening board independence, internal controls, and risk management can improve governance effectiveness and help increase CFP. Moreover, the heterogeneity analysis illustrates that ESG benefits are stronger for non-SOEs, vehicle manufacturers, and mature companies. For SOEs, they gain government support and face less pressure, and thus lack strong incentives to convert ESG into financial gains. Thereby, integrating ESG performance, particularly governance and environmental metrics, into the formal Key Performance Indicator (KPI) and compensation frameworks for executives may help SOEs improve their CFP. For auto parts suppliers, they are less noticeable to consumers and operate in B2B markets where ESG returns materialize slowly. To address this issue, policymakers should increase transparency in the supply chain. For example, regulators could require mandatory disclosure of ESG-related data for parts suppliers. Finally, young firms face resource and experience constraints in converting ESG initiatives into tangible financial outcomes. Hence, setting detailed ESG strategies and allocating limited resources to the ESG factors most critical to their business survival, such as R&D in clean energy and intellectual property governance, may mitigate this problem.

6. Conclusions

This research empirically examines the impact of ESG performance on financial performance in China’s automotive sector, employing both accounting-based and market-based indicators. In our empirical models, several key firm-level characteristics, such as firm size, leverage, and industry effects, are controlled to mitigate potential confounding influences. The results indicate a strong positive relationship between ESG performance and ROA, but no significant relationship with Tobin’s Q. Compared with studies in developed markets, where ESG often affects market valuation [37,38], this finding suggests that in China’s automotive industry, ESG initiatives primarily enhance operational efficiency while their market valuation effects remain limited. This pattern is consistent with evidence that emerging capital markets are less responsive to ESG information [52]. Among the three ESG pillars, governance has the most substantial impact on financial performance, underscoring its central role in transforming ESG engagement into financial value, similar to patterns observed in other capital-intensive and regulation-sensitive industries [57]. This finding indicates that favorable corporate governance, such as adequate internal control and sophisticated regulatory compliance, could improve CFP in the Chinese automotive market. Moreover, heterogeneity results show that the correlation between ESG performance and CFP varies by corporate attributes. It is suggested that the positive connection between ESG performance and CFP is significant only for non-SOEs, car manufacturers, and mature firms, and not for SOEs, parts producers, or younger firms. These outcomes could be due to stronger pressure on reputation and external supervision, greater consumer visibility, and greater capacity to translate ESG efforts into financial gains. Based on the above findings, for management, these findings suggest the importance of reinforcing corporate governance and aligning segmented ESG strategies with business goals and organizational capacity. For regulators, enhancing ESG disclosure consistency and promoting transparency across the supply chain could improve the informational value of ESG signals in capital markets.

This paper contributes to the literature in several ways. First, this study enriches ESG research on CFP in China’s automotive sector, which has received relatively less scholarly attention than other sectors. More importantly, this study identifies an uncommon divergence between accounting-based and market-based financial outcomes in China’s automotive industry. This finding provides new evidence that ESG engagement primarily creates value through internal operational and governance channels, while its reputational and market valuation effects remain limited in emerging capital markets. This finding enriches the understanding of how ESG functions across different institutional environments. Second, existing research on the Chinese automotive sector rarely decomposes ESG into its three dimensions. This paper breaks down overall ESG performance into three dimensions, namely environmental, social, and governance, helping us understand how different ESG factors affect a company’s value. Third, this research presents novel evidence on the heterogeneous impacts of ESG performance across ownership types, firm categories, and firm age. The evidence shows that ESG engagement yields greater financial benefits for non-SOEs, vehicle manufacturers, and mature firms. These findings highlight the importance of market discipline, reputational exposure, and organizational capability in transforming ESG efforts into financial value, thereby deepening the theoretical understanding of legitimacy, reputation, and resource-based mechanisms. Therefore, this paper bridges these research gaps, extending the ESG literature and offering actionable guidance to managers and regulators to develop ESG strategies that enhance sustainable competitiveness in the automotive sector.

Finally, several directions for future research are suggested. First, this study relies on a single ESG rating index. Since different rating agencies use distinct evaluation frameworks, ESG scores may vary across providers [13]. Utilizing only one index may, therefore, introduce measurement bias. Future research could combine multiple ESG databases or construct self-developed ESG indicators to improve measurement reliability. Second, although lagged ESG variables and fixed-effects models are applied to alleviate endogeneity concerns, they cannot fully resolve endogeneity [59]. Future studies could adopt stronger identification strategies, such as instrumental variables and policy-based quasi-natural experiments, to enhance causal inference [60]. Finally, other factors, aside from the control variables, such as macroeconomic conditions and unobservable managerial quality, may also affect financial performance and cannot be fully captured in the current analysis. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F. and B.F.; methodology, Y.F.; software, Y.F.; validation, Y.F. and B.F.; formal analysis, Y.F.; investigation, Y.F.; resources, Y.F. and B.F.; data curation, Y.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F.; writing—review and editing, Y.F. and B.F.; visualization, Y.F.; supervision, B.F.; project administration, B.F.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the Huazheng ESG database and the CSMAR database, which are available on a subscription basis from the respective data providers. Due to licensing restrictions, these data cannot be shared publicly. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| E | Environmental |

| S | Social |

| G | Governance |

| CFP | Corporate financial performance |

| NEVs | New energy vehicles |

| SOEs | State-owned enterprises |

| Non-SOEs | Non-state-owned enterprises |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| CSMAR | China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| p | p-value |

| H | Hypothesis |

| Obs. | Observations |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Evaluation dimensions of ESG (source: Huazheng’s ESG rating framework).

Table A1.

Evaluation dimensions of ESG (source: Huazheng’s ESG rating framework).

| Three Pillars | Themes | Key Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Environment (E) | Climate change | Greenhouse gas emissions |

| Carbon reduction pathways | ||

| Climate change adaptation | ||

| Sponge cities and green finance | ||

| Resource Utilization | Land use and biodiversity | |

| Water and Material consumption | ||

| Environmental Pollution | Industrial emissions | |

| Hazardous and electronic waste | ||

| Eco-friendliness | Renewable energy | |

| Green buildings and eco-friendly factories | ||

| Environmental Management | Sustainability certification | |

| Supply chain management | ||

| Environmental penalties | ||

| Social (S) | Human Capital | Employee health, safety, incentives and development |

| Labor relations | ||

| Product Responsibility | Quality certification | |

| Recalls and Complaints | ||

| Supply Chain | Supplier relations, risk and management | |

| Social Contribution | Philanthropy | |

| Community investment | ||

| Employment | ||

| Technological innovation | ||

| Data Security and Privacy | Data security and privacy protection | |

| Governance (G) | Shareholder Rights | Protection of shareholder interests |

| Governance Structure | ESG and risk control | |

| Board composition | ||

| Management stability | ||

| Disclosure Quality | ESG external assurance | |

| Reliability of information disclosure | ||

| Governance Risks | Behavior of controlling shareholders | |

| debt-paying ability | ||

| legal disputes | ||

| tax transparency | ||

| External Penalties | External penalties | |

| Business Ethics | Business ethics | |

| Anti-corruption, Anti-bribery |

Appendix B

Pre-Regression Preparation

Potential multicollinearity problems were investigated using variance inflation factor (VIF) tests, with the results displayed in Table A2. The results show that the mean VIF ranges from 1.20 to 1.28, lower than the commonly accepted threshold of 5, indicating low multicollinearity among the explanatory variables in the regressions. Thus, the estimates of the model parameters are stable and reliable.

Table A2.

Estimation results of multicollinearity via VIF.

Table A2.

Estimation results of multicollinearity via VIF.

| Variables | VIF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | 1.15 | |||

| E | 1.21 | |||

| S | 1.07 | |||

| G | 1.14 | |||

| SIZE | 1.49 | 1.58 | 1.40 | 1.35 |

| LEV | 1.42 | 1.34 | 1.32 | 1.48 |

| GROWTH | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 |

| Mean VIF | 1.27 | 1.28 | 1.20 | 1.24 |

In addition, this study examines the relationship between corporate financial performance and ESG performance using a firm-level panel regression model. The Hausman test was used to evaluate the fixed-effects (FE) and random-effects (RE) estimators to identify a more suitable panel data model, and the results are shown in Table A3. The test statistics are statistically significant at the 5% level for both ROA and TQ. The Chi-square statistics for ROA models vary from 32.21 to 58.59, yielding p-values of 0.000; for TQ models, the statistics range from 12.71 to 15.38, with p-values below 0.05. These findings reject the null hypothesis, asserting that the disparity in coefficients between the FE and RE estimators is systematic. Consequently, the fixed-effects model is preferred, indicating that unobserved firm-specific effects are associated with the explanatory variables across all model specifications.

Table A3.

Results of the Hausman test.

Table A3.

Results of the Hausman test.

| Variables | Chi-Square Statistic | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | TQ | ROA | TQ | |

| ESG | 45.04 | 12.71 | 0.000 | 0.013 |

| E | 52.14 | 13.18 | 0.000 | 0.010 |

| S | 58.59 | 15.38 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

| G | 32.21 | 13.46 | 0.000 | 0.009 |

Furthermore, the regression model incorporates company fixed effects to account for time-invariant heterogeneity among firms, such as management culture or industry characteristics, and year dummies to capture unobserved macroeconomic or policy shocks that may change over time but affect all firms similarly. Additionally, to provide more reliable statistical inference, standard errors are clustered at the firm level, taking into consideration serial correlation and potential heteroscedasticity within enterprises over time. This approach ensures that the calculated coefficients appropriately reflect the diversity in ESG performance within an organization and its relationship to financial results, net of firm- and time-specific elements.

Appendix C

Table A4.

Results of dimensional robustness check (environmental pillar).

Table A4.

Results of dimensional robustness check (environmental pillar).

| Variables | (1) ROA | (2) TQ | (3) ROE | (4) M/B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0015 | −0.0165 | |||

| (0.0017) | (0.0190) | |||

| E | 0.0070 * | −0.0021 | ||

| (0.0040) | (0.0061) | |||

| SIZE | 0.0160 *** | −0.4197 *** | 0.0344 | 0.1426 *** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0770) | (0.0225) | (0.0201) | |

| LEV | −0.1688 *** | 0.6259 * | −0.3523 *** | −0.1807 ** |

| (0.0202) | (0.3222) | (0.0799) | (0.0882) | |

| GROWTH | 0.0021 *** | −0.0003 | 0.0053 *** | −0.0010 |

| (0.0005) | (0.0053) | (0.0017) | (0.0012) | |

| CONS | −0.1962 * | 10.9280 *** | −0.4961 | −2.4459 *** |

| (0.1098) | (1.5741) | (0.4591) | (0.4019) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Obs. | 1581 | 1581 | 1775 | 1775 |

| R-squared | 0.2976 | 0.1722 | 0.1686 | 0.3897 |

| F-statistic | 12.48 | 11.22 | 7.17 | 37.01 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Note: Standard error in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table A5.

Results of dimensional robustness check (social pillar).

Table A5.

Results of dimensional robustness check (social pillar).

| Variables | (1) ROA | (2) TQ | (3) ROE | (4) M/B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0010 | 0.0100 | |||

| (0.0010) | (0.0195) | |||

| S | 0.0032 | −0.0052 | ||

| (0.0030) | (0.0044) | |||

| SIZE | 0.0160 *** | −0.4244 *** | 0.0351 | 0.1434 *** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0759) | (0.0227) | (0.0203) | |

| LEV | −0.1697 *** | 0.6274 * | −0.3563 *** | −0.1782 ** |

| (0.0201) | (0.3200) | (0.0798) | (0.0885) | |

| GROWTH | 0.0021 *** | 0.0000 | 0.0053 *** | −0.0009 |

| (0.0005) | (0.0053) | (0.0017) | (0.0012) | |

| CONS | −0.1967 * | 10.9762 *** | −0.5093 | −2.4510 *** |

| (0.1096) | (1.5658) | (0.4597) | (0.4051) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Obs. | 1581 | 1581 | 1775 | 1775 |

| R-squared | 0.2978 | 0.1722 | 0.1677 | 0.3906 |

| F-statistic | 13.92 | 11.31 | 6.81 | 36.11 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Note: Standard error in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table A6.

Results of dimensional robustness check (governance pillar).

Table A6.

Results of dimensional robustness check (governance pillar).

| Variables | (1) ROA | (2) TQ | (3) ROE | (4) M/B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0020 | −0.0032 | |||

| (0.0013) | (0.0211) | |||

| G | 0.0134 *** | 0.0071 | ||

| (0.0046) | (0.0049) | |||

| SIZE | 0.0157 *** | −0.4213 *** | 0.0318 | 0.1401 *** |

| (0.0049) | (0.0757) | (0.0226) | (0.0203) | |

| LEV | −0.1674 *** | 0.6283 ** | −0.3319 *** | −0.1674 * |

| (0.0200) | (0.3179) | (0.0795) | (0.0886) | |

| GROWTH | 0.0021 *** | −0.0003 | 0.0052 *** | −0.0010 |

| (0.0005) | (0.0054) | (0.0017) | (0.0012) | |

| CONS | −0.2009 * | 10.9594 *** | −0.5247 | −2.4447 *** |

| (0.1095) | (1.5726) | (0.4647) | (0.4014) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Obs. | 1581 | 1581 | 1775 | 1775 |

| R-squared | 0.2989 | 0.1719 | 0.1757 | 0.3908 |

| F-statistic | 12.69 | 12.10 | 6.96 | 35.82 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Note: Standard error in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

References

- Carreira, F.; Silva, A.; Cepêda, C. Does Profitability Support Sustainability? Examining the Influence of Financial Performance and ESG Controversies on ESG Ratings. Systems 2025, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wu, M.; Li, D.; Zhou, Y.; Kang, J. ESG and Corporate Financial Performance: Empirical Evidence from China’s Listed Power Generation Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, N. The Effect of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance on Corporate Financial Performance in China: Based on the Perspective of Innovation and Financial Constraints. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030. Available online: https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/policies/202110/t20211027_1301020.html (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Working Guidance for Carbon Dioxide Peaking and Carbon Neutrality in Full and Faithful Implementation of the New Development Philosophy. Available online: https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/policies/202110/t20211024_1300725.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- The State Council of China. China to Take Action for Energy Conservation, Carbon Reduction. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202405/29/content_WS66570ed0c6d0868f4e8e79d0.html (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Sun, T.; Abdullah, M.A.B. Impact of Industrial Agglomeration on the Upgrading of China’s Automobile Industry: The Threshold Effect of Human Capital and Moderating Effect of Government. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, F.; Liu, Z. How Does China Explore the Synergetic Development of Automotive Industry and Semiconductor Industry with the Opportunity for Industrial Transformation? Sustainability 2025, 17, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, P.; Zhu, D. Overview of Chinese New Energy Vehicle Industry and Policy Development. Green Energy Resour. 2024, 2, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. ESG in Focus: The Australian Evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak, M. A Literature Review on the Difference between CSR and ESG. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2022, 2022, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirino, N.; Santoro, G.; Miglietta, N.; Quaglia, R. Corporate Controversies and Company’s Financial Performance: Exploring the Moderating Role of ESG Practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Fang, X.; Shen, Z. ESG Rating Divergence and Stock Price Crash Risk. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2025, 76, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Yang, F.; Xiong, L. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance and Firm Value: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P.J.; Devinney, T.M.; Yip, G.S.; Johnson, G. Measuring Organizational Performance: Towards Methodological Best Practice. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 718–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Hitt, M.A., Freeman, R.E., Harrison, J.S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Wang, H. ESG and Customer Stability: A Perspective Based on External and Internal Supervision and Reputation Mechanisms. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A. Intellectual Capital and Firm Performance: Differentiating between Accounting-Based and Market-Based Performance. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2018, 11, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The Corporate Social Perforance-Financial Performance Link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.H.; Pruitt, S.W. A Simple Approximation of Tobin’s q. Financ. Manag. 1994, 23, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. The Impact of ESG on Financial Performance: An Empirical Analysis of Listed Companies in China. Adv. Econ. Manag. Polit. Sci. 2024, 83, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğmuş, M.; Gülay, G.; Ergun, K. Impact of ESG Performance on Firm Value and Profitability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, S119–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Ma, L.; Wu, D. ESG Performance and Corporate Innovation under the Moderating Effect of Firm Size. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 97, 103774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More than 2000 Empirical Studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarna, K.; Garde Sánchez, R.; López-Pérez, M.V.; Marzouk, M. The Effect of Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure and Real Earning Management on the Cost of Financing. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3181–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, P.; Shome, S. ESG–CFP Linkages: A Review of Its Antecedents and Scope for Future Research. Indian J. Corp. Gov. 2022, 15, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsali, C.; Skordoulis, M.; Papagrigoriou, A.; Kalantonis, P. ESG Scores as Indicators of Green Business Strategies and Their Impact on Financial Performance in Tourism Services: Evidence from Worldwide Listed Firms. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, P. Corporate Goodness and Shareholder Wealth. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Does ESG Performance Have an Impact on Financial Performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M.M.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, X. Short-Term Costs and Long-Term Gains of ESG Initiatives in High-Risk Environments: Evidence from UK Firms. Dev. Sustain. Econ. Financ. 2025, 7, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, G.; Kihle Fagernes, R.V.; Elmarzouky, M.; Afzal Hossain, K.A.B.M. The ESG Disclosure and the Financial Performance of Norwegian Listed Firms. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiraj, R.; Demiraj, E.; Dsouza, S. The Moderating Role of Worldwide Governance Indicators on ESG–Firm Performance Relationship: Evidence from Europe. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Law, P. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) and Financial Performance of Listed Companies in the Automotive Industry in China. J. Account. Tax. 2025, 17, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. The Impact of ESG Performance on Corporate’s Financial Performance: Evidence from China’s Automobile Manufacturing Industry. Highlights Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 37, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the Relation between Environmental Performance and Environmental Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Qian, C. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in China: Symbol or Substance? Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ren, G.; Li, J. State-Owned Shares, Government Background Customer Relationship and Non-State-Owned Enterprises’ Financing Cost. Pac. Account. Rev. 2025, 37, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. State-Owned Enterprises in China: A Review of 40 Years of Research and Practice. China J. Account. Res. 2020, 13, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Xiong, R.; Peng, H.; Tang, S. ESG Performance and Private Enterprise Resilience: Evidence from Chinese Financial Markets. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 98, 103884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervits, I. CSR Reporting in China’s Private and State-Owned Enterprises: A Mixed Methods Comparative Analysis. Asian Bus. Manag. 2023, 22, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; She, G.; Yoon, A.; Zhu, H. Shareholder Value Implications of Supply Chain ESG: Evidence from Negative Incidents. Rev. Account. Stud. 2025, 30, 2185–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.A.; Jenatabadi, H.S. The Influence of Firm Age on the Relationships of Airline Performance, Economic Situation and Internal Operation. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2014, 67, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.R.; Shepherd, D.A. Stakeholder Perceptions of Age and Other Dimensions of Newness. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, T.; Nur, T. The Effect of ESG Sustainability on Firm Performance: A View Under Size and Age on BIST Bank Index Firms. Ekon. Polit. Finans Araştırmaları Derg. 2023, 8, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adwani, A. ESG Investing Trends in Emerging Markets: A Behavioral Finance Perspective. Int. J. Soc. Impact 2025, 10, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J.; Hauptmann, C.; Serafeim, G. Material Sustainability Information and Stock Price Informativeness. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 513–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Zhang, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Risk: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4451–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.; Krajcsák, Z. The Impacts of Corporate Governance on Firms’ Performance: From Theories and Approaches to Empirical Findings. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2024, 32, 18–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natto, D.; Mokoaleli-Mokoteli, T. Short- and Long-Term Impact of Governance on Firm Performance in Emerging and Developed Economies: A Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2025, 22, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Im, E.; Gim, G. The Impact of ESG Management by Automobile Companies on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simnett, R.; Vanstraelen, A.; Chua, W.F. Assurance on Sustainability Reports: An International Comparison. Account. Rev. 2009, 84, 937–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F.; Masaki, T.; Pepinsky, T.B. Lagged Explanatory Variables and the Estimation of Causal Effect. J. Polit. 2017, 79, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeb, D.; Sakakibara, M.; Mahmood, I.P. From the Editors: Endogeneity in International Business Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.