Abstract

Socialized agricultural services (SASs) play a crucial role in enhancing grain production capacity, promoting environmentally friendly and sustainable practices, and integrating smallholder farmers into modern agriculture. Our study applies the Super-Efficiency SBM (slack-based measure) model to measure the green grain production efficiency (GGPE) of farmers. We then employ the Tobit model, the threshold regression model, and the moderated effect model to empirically analyze the influence of SASs on farmers’ GGPE. SASs are found to significantly enhance farmers’ GGPE. Furthermore, the relationship between the scale of utilization of farmers’ services (SUFS) and GGPE exerts a single-threshold effect. Among government environmental regulations (GERs), both constrained and guided regulation measures significantly positively moderate the relationship between SASs and farmers’ GGPE. We recommend that governments tailor SASs to address specific farmer needs; develop differentiated support policies for service utilization scales based on local conditions; and strengthen the environmental regulatory framework through a multi-pronged approach, by reinforcing constrained environmental regulations, refining incentive environmental regulations, and deepening guided environmental regulations, to consistently elevate farmers’ GGPE.

1. Introduction

The global food system has undergone significant transformation in recent years, with an increasing emphasis on sustainability [1]. As a leading global producer of grain with the highest cereal output worldwide, China has maintained a total grain production exceeding 650 million metric tons for ten consecutive years, according to data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Notably, in 2024, the nation’s grain output surpassed 700 million metric tons for the first time. However, China’s attainment of twenty-one consecutive years of grain abundance has been accompanied by emerging challenges, as the conventional extensive farming model “characterized by intensive input, high resource consumption, and elevated output” has led to increasing resource overuse and aggravated agricultural non-point source pollution [2]. To address the increasingly severe environmental influences, including strict restrictions on production factors, inefficient and excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides [3], and severe non-point source pollution [4], the Chinese government has prioritized and actively promoted green grain production. The Communist Party of China Central Committee and the State Council have unveiled a plan to strengthen China’s position in agriculture at a faster rate for the 2024 to 2035 period, with the dual goals of comprehensively strengthening national food security and accelerating the green transformation of agriculture. As the separability of agricultural production from operational activities has gradually increased [5], socialized agricultural services (SASs) have gradually become widespread. Data released by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China indicates that, by the end of 2024, a total of 1.094 million business entities nationwide had engaged in SASs, covering an annual service area exceeding 142.67 million hectares. SASs enable grain production activities without altering farmland management rights, gradually becoming a crucial means of ensuring food security [6]. Given this context, what impact do SASs have on the green grain production efficiency (GGPE) of farmers? How do different scales of utilization of farmers’ services (SUFSs) influence their GGPE? Do government environmental regulations (GERs) play a moderating role between SASs and farmers’ GGPE?

Currently, scholars both in China and internationally have conducted in-depth research on SASs and GGPE. Many researchers have employed methods such as stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) [7], data envelopment analysis (DEA) [8], and the super slack-based measure (SBM) to assess GGPE. Environmental pollutants are incorporated as non-expected outputs in these efficiency calculations [9,10]. Research indicates that China’s green production efficiency for grain exhibits an overall upward trend, while it shows a declining trend at the regional level [11]. Improving grain GGPE can promote stable grain growth while protecting the ecological environment [12]. Meanwhile, scholars have empirically analyzed the influencing factors of GGPE [13] and found that factors such as green technology application [14], land transfer [15], urbanization [16], farmers’ digital literacy [17], and agricultural technology services [18] all have a significant impact on farmers’ GGPE. Among them, SASs, as a key force in promoting agricultural modernization, are complementary and mutually reinforcing to grain production [19,20]. On the one hand, SASs promote the “grain-oriented” development of farmland [21], which can effectively reduce production costs and increase grain output [22]. In the long run, SASs help improve farmers’ GGPE and achieve sustainable development of agricultural production [23,24]. On the other hand, with the continuous growth of grain demand and intensified market competition, farmers’ demands for SASs are becoming increasingly diversified and personalized. The larger the scale of a farmer’s operation, the higher their demand for SASs in grain production, which makes the spillover effects of optimizing SASs more significant [25,26].

In summary, existing research provides a scientific basis for exploring the relationship between SASs and GGPE. However, previous studies focusing on the impact of SASs on GGPE have not considered the potential mechanisms and failed to fully distinguish the heterogeneity in farmers’ SASs adoption levels and utilization scales. Additionally, there remains a lack of research on the regulatory effect of GERs on SASs on farmers’ GGPE. Due to the failure to consider the impact of the level of SASs on farmers’ GGPE, it is difficult to accurately determine the effect of its implementation. Therefore, this paper constructs a theoretical and logical framework, and based on micro-level data of farmers, employs the Stata software (version 19) to evaluate the impact of SASs on farmers’ GGPE through Tobit Model, Threshold Regression Model and Moderated Effect Model, examine how differences in SUFSs affect farmers’ GGPE, and further explore the regulatory role of GERs in influencing the SASs and farmers’ GGPE. The overall goal is to fully understand the impact of SASs on farmers’ GGPE and the regulating effect of the relationship between the two, thereby providing a scientific basis for the government to improve SASs.

2. Theoretical Analysis Framework

The development model of green grain production is ultimately a combination of land, capital, labor, and other production factors, along with their internal and external allocation [27]. Improving its efficiency depends on the introduction of advanced production technology and equipment, which accelerates the optimal allocation of production factors, adjusts the production input structure, and facilitates the coordinated development of the agricultural economy and the environment [28]. Therefore, as a new form of productivity organization, the service model, scale, and impact of SASs allow them to significantly influence specific grain production processes, surpass traditional grain production modes, and support farmers towards green development.

2.1. Direct Impact

Schultz’s theory of farmers’ behavior posits that farmers are rational economic subjects, and their decision-making with regard to grain production is generally guided by the principle of profit maximization. Therefore, when choosing SASs, farmers may pay more attention to expected output and overlook or disregard non-expected output. However, with the continued increase in grain yield, the rough farming method employed by small farmers frequently leads to environmental external problems, such as reductions in soil organic matter, soil acidification, soil plate knotting, thinning of the topsoil layer, and a decline in farmland quality, and the problem of green grain production is increasingly prominent. With the increase in the number of farmers employed part-time and population aging, farmers’ decisions on SASs may no longer be based solely on grain production. Compared with traditional farming methods, farmers are increasingly inclined to adopt time-saving, effort-saving, and worry-saving SASs at some or even all stages of production, whether due to considerations of capital investment, time investment, or remuneration or because of their own resource limitations. Farmers’ use of SASs can not only improve grain production efficiency and maximize output and profits but also alleviate some environmental problems in the production process and promote green agricultural development. Therefore, SASs are increasingly becoming a key measure to solve the contradiction between food production and environmental pollution.

SASs achieve a rationalized division of labor and professional services through the three dimensions of technology embedding, factor substitution, and service standardization, thereby improving farmers’ GGPE. First of all, technology embedding mainly refers to the service institutions providing professional services such as precise fertilization, green pest prevention and control, and water-saving irrigation. Technology embedding directly incorporates external green technology into farmers’ grain production systems, lowers the threshold for technology adoption, overcomes the constraints on the limited ability of small farmers to adopt technology, and encourages farmers to outsource grain production links that lack comparative advantages, thereby facilitating the adaptive restructuring of the technical system. While ensuring grain production, it is also necessary to improve the GGPE of farmers. Secondly, factor substitution is mainly reflected in the structural transformation of advanced production factors, systematically replacing traditional production factors, replacing high-energy-consuming labor through green agricultural machinery services to improve energy efficiency, replacing coarse input with precise technical schemes to optimize the input structure, and replacing polluting factors with green production factors to reduce waste materials. Source utilization and other paths promote the green production of grain for farmers. Thirdly, service standardization mainly involves establishing a standardized operational system that is quantifiable, supervisable, and traceable. This refers to transforming the green concept into standardized operation procedures to ensure the quality of green production technologies. It is possible to avoid technical distortions in how farmers operate such technology through standardization of the operation process, input management, and supervision and evaluation. Moreover, under the market’s competitive “survival of the fittest” mechanism, SASs continuously enhance proficiency and indirectly boost production levels across all grain production stages [29], providing farmers with superior services and driving improvements in GGPE.

2.2. Threshold Effect of Service Scale

The widespread adoption of SASs has gradually made them an effective measure for enhancing farmers’ GGPE. However, the relationship between the scale of SASs and the green production efficiency of grain is not a simple linear one; instead, it exhibits a certain degree of nonlinearity. Based on the scale of service utilization by farmers, first, when the service scale is relatively small, fixed costs are difficult to amortize, making it impossible to achieve effective economies of scale and resource integration. According to the theory of induced institutional change, the implementation of new green technologies often cannot be separated from high economic and cognitive costs. Furthermore, the increasing fragmentation of operations and the piecemeal utilization of farmland further raise the threshold for farmers to adopt green technologies. This results in high costs and low benefits for the use of green technologies, making it challenging to overcome the constraints on farmers’ adoption of new technologies. Consequently, the promotion of green production efficiency in grain farming through the use of these technologies is limited or even insignificant. Secondly, when the scale of service exceeds a certain threshold, although it may continue to improve farmers’ GGPE, its promoting effect will gradually weaken. A possible reason for this is that the structural mismatch between service supply and farmers’ needs, as well as the increase in management complexity, will lead to higher regulatory costs, reduce the accuracy and responsiveness of services, and hinder the improvement in farmers’ GGPE. Finally, when the service scale reaches an appropriate level, SASs can use the resource integration and scale effects brought about by expanding the scale to reduce production costs and improve the efficiency of chemical inputs; as a result, this would increase expected output or reduce unexpected output and achieve the goal of improving farmers’ GGPE. The double improvement in the “efficiency” and “effectiveness” of green production provides an effective solution to meet the above challenges.

At the appropriate stage of the service scale, based on the configuration of production factors, the scale effect brought about by the expansion of SASs can achieve a Pareto improvement in farmers’ green input. By integrating decentralized demand, centralized procurement of agricultural inputs, and unified operating standards, SASs reduce farmers’ unit production costs and expenditures related to the search for food production factors, technology, and training. On the whole, SASs can alleviate the constraints on the input of resource factors, optimize the allocation of grain production factors, and solve problems such as the aging and low-quality labor force of farmers, the deterioration and fragmentation of farmland, and rough operation. Therefore, SASs have promoted the intensive development of green grain production. Furthermore, at the level of technology diffusion, the expansion of the scale of services has promoted the non-competitive supply of green technologies, overcome the limitations of resource endowment, and produced a knowledge spillover effect. Large-scale centralized procurement of technical services such as soil testing and formula fertilization, along with green pest control, not only spreads the cost of adopting new green technologies but also breaks down barriers to technology adoption faced by smallholder farmers due to high investment costs and long payback periods. This approach enhances farmers’ capacity to absorb and access green agricultural production technologies. At the same time, SASs integrate green production technology into mechanized operations and unified pest control efforts to improve the efficiency of the utilization of chemical inputs in grain production, reduce the intensity of the use of high-pollution emission input factors [30], effectively give full play to the economies of scale of farmers’ use of SASs, and achieve the embedding of green technology to promote green grain production. The analysis indicates that the impact of service scale on farmers’ GGPE is complex and cannot be simply summarized as a linear relationship.

2.3. Moderating Effects of Government Environmental Regulations

As an important external factor influencing farmers’ behavior and decision-making, GERs play a key regulatory role in the relationship between SASs and GGPE. Based on Pigouvian theory and property rights theory, on the one hand, the individual marginal costs and benefits of farmers’ participation in management can be balanced with the social marginal costs and returns through direct regulatory measures such as government environmental pollution taxes and environmental management subsidies to internalize the externality of environmental pollution in grain production. On the other hand, we should solve environmental problems by clarifying the definition of property rights, such as standardizing service contracts and other economic means to quantify environmental constraints, and encourage farmers to use resource-saving services. However, the inherent attributes of public goods in the environment itself make property rights difficult to define during the grain production process, which often leads to “market failure”. In addition, farmers often overlook environmental problems to some extent in their pursuit of high yield, which can lead to increased environmental pollution levels as grain production increases. In view of this, GERs are undoubtedly the key driving force behind farmers’ efforts to achieve green grain production [31]. Scholars both in China and abroad mainly divide environmental regulation tools into three types based on their characteristics: constrained, incentive, and guided [32,33,34]. Research indicates that government environmental regulations have a significant impact on farmers’ agricultural production [35], which is beneficial for enhancing their green production technology and thereby improving agricultural productivity [36].

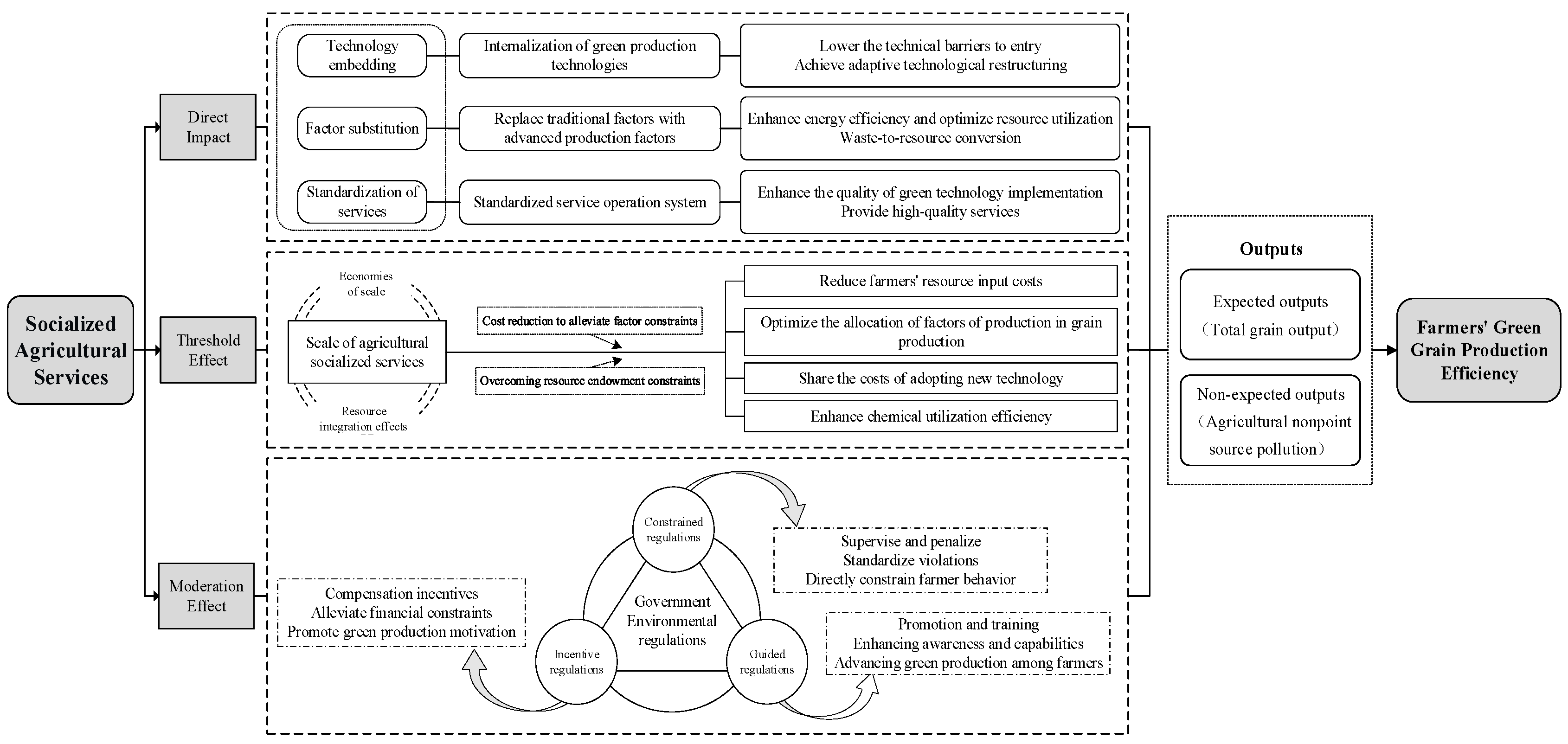

In the actual grain production process, constrained environmental regulations refer to the government’s regulations on farmers’ violations, enforced through supervision and punishment. The government formulates green production standards and establishes a green operation quality traceability system for service organizations. By linking test results with service qualifications, the government has imposed strict restrictions on service providers, compelling them to translate ecological requirements into specific operating standards. At the same time, by standardizing the service links of grain production services, the efficiency of fertilizer use can be improved, thereby directly standardizing farmers’ green grain production behavior. Incentive environmental regulations refer to the government’s use of economic compensation or incentive policies to increase farmers’ income and alleviate their economic pressure, thereby improving their enthusiasm for green grain production. For example, green service subsidies and ecological compensation policies. Guided environmental regulations focus on the promotion of and provision of training in green production by the government. The government aims to raise farmers’ awareness of green grain production and enhance their capabilities by establishing demonstration bases and other means. It also encourages farmers to pay attention to previously neglected environmental issues, thereby promoting a transformative leap in green grain production initiatives. The specific research logic framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Logical framework diagram.

Therefore, based on the above analytical framework, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

Socialized agricultural services (SASs) can enhance farmers’ green grain production efficiency (GGPE).

Hypothesis 2.

The impact of the scale of utilization of farmers’ services (SUFS) on farmers’ GGPE exhibits a threshold effect.

Hypothesis 3.

Government environmental regulations (GERs) exert a moderating effect on the relationship between SASs and farmers’ GGPE.

3. Research Data and Methods

3.1. Data and Variables

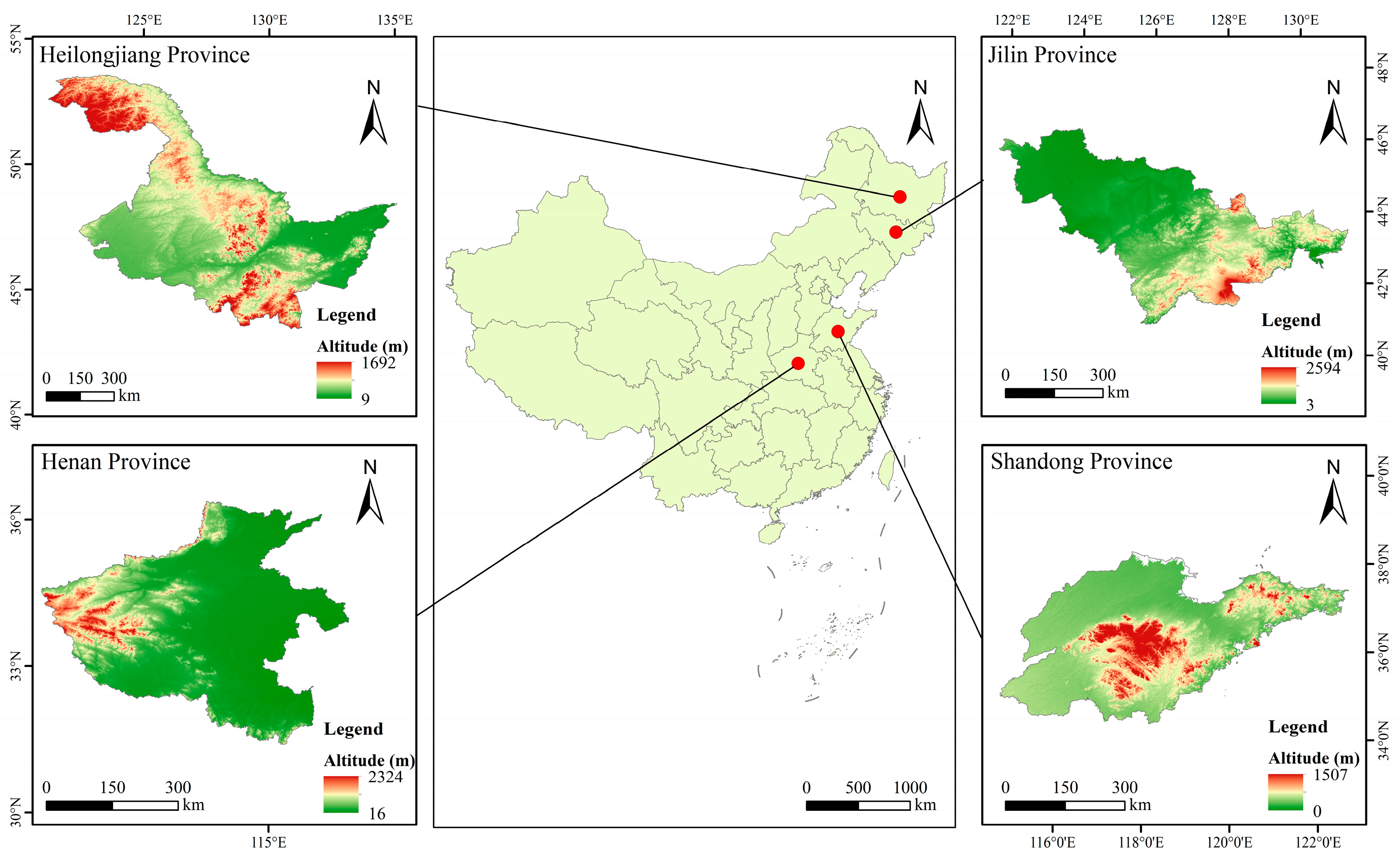

This study mainly explores the impact of SASs on GGPE, focusing on corn farmers. The team traveled to Heilongjiang, Henan, Shandong, and Jilin—four major grain-producing provinces—to conduct field research and collect relevant data. The selection of study regions was primarily based on the following dimensions: First, the strategic significance of major grain-producing areas ensures national representativeness. In 2024, Heilongjiang, Henan, Shandong, and Jilin ranked among China’s top four grain-producing provinces, with yields of 80.017 million tons, 67.194 million tons, 57.102 million tons, and 42.66 million tons, respectively. Their combined output exceeded one-third of the country’s total grain production. Second, these regions exemplify the challenges of green transformation in grain production. As intensively utilized granaries, Heilongjiang, Henan, Shandong, and Jilin collectively face environmental pressures such as degraded farmland quality and non-point source pollution. Their urgent need for green transformation in grain production provides a practical and representative observation window for examining how SASs can integrate and enhance GGPE. Third, robust policy support and data foundations enhance universality. As the “ballast stones” for national grain stability and security, the four provinces in the study region possess typical supportive policies for green grain production and SASs under the dual objectives of ensuring food security and advancing green agriculture. Extensive accumulated research data further enhances the universality of the findings by analyzing the varying development levels of SASs and grain production across these provinces. Although this study comprehensively considers each province’s grain production capacity, structure, and role in national grain production, making the selected research areas nationally representative, it must be acknowledged that the conclusions and policy recommendations may have limited explanatory power and applicability to provinces with different functional roles—such as major grain-consuming regions and balanced grain-producing–consuming regions—due to the concentration of research samples in major grain-producing areas. Therefore, this study focuses on farmers as the primary research subjects, calculates the GGPE of farmers based on field survey data, and examines the impact of SASs on GGPE. The survey data covered four provinces, 21 counties (cities), and 51 townships, resulting in a total of 783 valid questionnaires collected. Figure 2 shows the selected provinces in a map of China.

Figure 2.

Overview map of the research areas in China. Note: The base map was produced using the standard map of the Ministry of Natural Resources (Review No.GS (2024)0650), and there are no modifications to the base map.

3.1.1. Core Explanatory Variables

Socialized agricultural services (SASs): The binary indicator of whether farmers use such services fails to capture usage disparities among different farmers, and absolute metrics such as per-mu service expenditure or number of contracted processes cannot isolate differences in service utilization behavior caused by regional variations in service market development. Therefore, this study primarily employs the relative indicator of the proportion of farmers’ expenditures on SASs relative to their total grain production costs to measure the level of agricultural socialization. Additionally, considering that, in some regions, certain SASs segments are provided free of charge to farmers based on policy factors (where the government directly disburses subsidies to the owners of agricultural machinery that provides the services), this subsidy amount is factored into household expenditures on SASs when measuring such services.

The scale of utilization of farmers’ services (SUFS): The scale of farmer service utilization is largely determined by the actual cultivated land area managed by farmers when accessing SASs, with less emphasis on contiguous service coverage. Therefore, selecting the scale of farm service utilization as the threshold variable and measuring it through the actual cultivated land management scale provides a more intuitive and fundamental way to assess the specific direction and extent of impact that SASs exert on farmers’ green grain production efficiency (GGPE). Considering that farmers’ actual cultivated plots may be scattered, this study calculates the actual cultivated land management scale using the ratio of grain planting area to the number of cultivated plots.

Government environmental regulations (GERs): Drawing on existing measurement methods for GERs, this study examines the moderating effects of three types of environmental regulations—constrained regulations (CRs), incentive regulations (IRs), and guided regulations (GRs) [37]—on the impact of SASs on farmers’ GGPE. Table 1 presents the definitions of relevant variables and descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and descriptive statistics for the impact of SASs on farmers’ GGPE.

3.1.2. Dependent Variable

Input–output indicators were selected to examine farmers’ green grain production efficiency (GGPE). With reference to the existing literature [38], and based on data availability, this study selected seven production factor input indicators: land, labor, machinery, water use, seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. Furthermore, two output indicators were selected, primarily categorized as expected and non-expected outputs. The detailed indicator system for calculating farmers’ GGPE is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Construction of the indicator system for measuring GGPE at the farm level.

In calculating agricultural non-point source pollution emissions, the pollution-generating units are defined as nitrogen, phosphorus, and compound fertilizers. The nitrogen and phosphorus pollution emissions are calculated per unit area. Referencing the studies by Luo et al. and Min and Kong [39,40], the formula for agricultural non-point source pollution (ANSP) emissions is as follows:

where represents the statistical indicator for pollution-generating unit , i.e., the pure-element equivalent application rate of nitrogen, phosphorus, and compound fertilizers; is the pollution generation coefficient for pollution-generating unit . The pollution generation coefficient is calculated based on the chemical composition of the fertilizer conversion. The pollution generation coefficient for a specific element is the proportion of that chemical element in the fertilizer conversion. The nitrogen pollution generation coefficients for nitrogen, phosphorus, and compound fertilizers are 1.00, 0.00, and 0.33, respectively. The phosphorus pollution generation coefficients are 0.00, 0.44, and 0.15, respectively. denotes the pollutant generation quantity of pollution-generating unit ; denotes the pollution emission coefficient for . According to Annex 1 “Agricultural Pollution Source Pollutant Production and Emission Coefficient Manual” in the “Manual on Pollutant Production and Emission Calculation Methods and Coefficients for Emission Source Statistical Surveys” issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China in 2021, the nitrogen and phosphorus emission (loss) coefficients for crop cultivation are as follows: the total nitrogen emission (loss) coefficients for Heilongjiang Province, Shandong Province, Henan Province, and Jilin Province are 1.028 kg/hm2, 0.817 kg/hm2, 2.976 kg/hm2, and 0.532 kg/hm2, respectively; the total phosphorus discharge (loss) coefficients are 0.104 kg/hm2, 0.019 kg/hm2, 0.234 kg/hm2, and 0.015 kg/hm2, respectively.

3.1.3. Control Variables

To avoid interference from other factors, this study controlled for 10 variables: the characteristics of farmers’ own endowments such as their age (AGE), education level (EDU), village-level position (VLP), employment status (ES), and years of farming experience (YFE), and the characteristics of their household resource endowments, such as proportion of income from migrant work (PIMW), agricultural insurance (AGI), disaster situation (DS), grain subsidies (GS), and regional dummy variable (RDV).

3.2. Model Construction

3.2.1. Super-Efficiency SBM Model

The Super-Efficiency SBM model incorporates non-expected outputs [41]. In grain production, besides expected outputs such as yield, there also exist non-expected outputs resulting from fertilizer application. The Super-Efficiency SBM model demonstrates superior handling of non-expected outputs in GGPE, effectively avoiding input–output slack phenomena. It provides a more comprehensive assessment of farmers’ GGPE, accurately reflecting their actual grain production conditions. It is expressed as follows:

where represents the optimal solution (GGPE value); denotes the weight variable; signifies the decision-making unit; respectively, represent inputs, expected outputs, and non-expected outputs; denote the number of variable types for inputs, expected outputs, and non-expected outputs (where are the variables); and , respectively, represent the slack variables for inputs, expected outputs, and non-expected outputs.

3.2.2. Tobit Model

This study used a Super-Efficiency SBM model to calculate the explanatory variable, the GGPE of farmers, which ranged from 0 to 2 and consisted of truncated data. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression is commonly used in analyses to perform linear regression on entire samples; however, nonlinear disturbance terms are included in the disturbance term, which can lead to inconsistent estimates. In contrast, the Tobit model is estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method. It has the characteristic of bilateral broken tails and can convert censored data into a probability model, featuring high estimation accuracy and reliability. Therefore, drawing on existing research [42,43], the model is as follows:

where represents the GGPE of the ith farmer; denotes SASs; indicates control variables, such as the characteristics of farmers’ own endowments and their household resource endowments, and regional characteristics; is the constant term; is the regression coefficient of the core explanatory variable; is the regression coefficient of the control variables; and represents the random error term.

3.2.3. Threshold Regression Model

A threshold regression model was constructed to examine the nonlinear and heterogeneous characteristics of farmers’ GGPE in relation to the scale of their SAS utilization [44]. Compared to grouped regression, the threshold regression model can partition the data into intervals and identify thresholds, thereby avoiding the subjectivity inherent in grouping. It employs rigorous statistical inference methods for parameter estimation and hypothesis testing of threshold values. The model is established as follows (single-threshold model):

where is the threshold variable; is the threshold value to be estimated; is the indicator function, taking 1 if the expression in parentheses is true and 0 otherwise; and represent the coefficient of the explanatory variable on the dependent variable when and , respectively; and the other parameters have the same meanings as in Equation (4).

3.2.4. Moderated Effect Model

This study employs a moderated effect model [45] to empirically examine the moderating role of government environmental regulations (GERs) between SASs and farmers’ GGPE. To avoid multicollinearity, interaction terms undergo centering. The moderated effect model is established as

where represents the moderator variable; denote the coefficients for the core explanatory variable, the moderator variable, and the interaction term between the core explanatory variable and the moderator variable, respectively. Other parameters retain the same meanings as in Equation (4).

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of the Impact of SASs on Farmers’ GGPE

4.1.1. Multicollinearity Test

To ensure the stability and accuracy of the Tobit model, this study employed the variance inflation factor (VIF) for multicollinearity testing. According to the test results (see Table 3), this confirms the absence of multicollinearity among the variables in the model, allowing for further analysis and testing.

Table 3.

Multicollinearity test results for explanatory variables.

4.1.2. Analysis of Tobit Model Regression Results

Based on the measurement results of the Super-Efficiency SBM model, the impact of SASs on farmers’ GGPE is analyzed in depth using the Tobit model. As shown in Table 4, at the significance level of 1%, the impact of SASs on the GGPE of farmers is significantly positive. This indicates that, when farmers’ cultivated land area remains relatively fixed, the proportion they are willing to pay for agricultural socialized services increases under constraints on total production costs for grain production. This suggests that farmers may demonstrate stronger willingness to invest in specialized, intensive, and green services, indicating greater acceptance and utilization of advanced green production technologies. Consequently, farmers can ensure grain output while simultaneously prioritizing green production practices.

Table 4.

Model estimation results.

Among the characteristics of farmers’ own endowments, the village-level positions and employment status of decision-makers have a significant positive impact on farmers’ GGPE at a level of 1%. This implies that, as farmers’ political awareness increases, their understanding of the importance of green grain production may partially improve, thereby stimulating their enthusiasm for adopting such practices. Simultaneously, among farmers with different employment statuses, those engaged in full-time farming often devote greater attention and specialized management to grain production compared to non-agricultural workers or part-time farmers. Consequently, they may place higher value on the efficiency and environmental sustainability of grain production. This enables them to build sustained expertise in technology adoption and ecological management, thereby enhancing farmers’ GGPE. The educational attainment level of decision-makers has a positive but insignificant impact on farmers’ GGPE, indicating that higher education levels often correlate with stronger awareness of green grain production practices. This heightened environmental consciousness may encourage farmers to adopt green production behaviors, thereby improving their GGPE. Conversely, the age of decision-makers and their years of farming experience exert a negative yet insignificant influence on farmers’ GGPE. Older farmers with more experience may have a relatively limited understanding of green grain production and exhibit weaker willingness and adaptability toward adopting new cultivation techniques and methods. These cognitive and behavioral limitations often result in insufficient motivation to implement green production practices.

Among the characteristics of farmers’ household resource endowments, the purchase of agricultural insurance has a significant positive impact on GGPE at the level of 1%. This suggests that agricultural insurance may serve as a reassuring safeguard by stabilizing farmers’ production expectations and reducing operational risks. Consequently, it enhances their willingness and confidence to adopt green production technologies, thereby boosting their enthusiasm for green grain production. At a 1% significance level, the disaster situation has a significant negative impact on GGPE. This indicates that natural disasters disrupt the continuity of agricultural production and compel farmers to invest additional resources in recovery efforts, thereby increasing production costs and consequently constraining improvements in farmers’ green production efficiency. The proportion of family income from outbound workers has a negative but non-significant impact on farmers’ GGPE. This implies that the increasing share of income derived from off-farm employment may marginalize grain production within household economies, relegating it to a supplementary source of income. To some extent, this diminishes the importance some farming households place on green grain production and their willingness to invest in production factors, thereby dampening their enthusiasm for adopting green production practices. Income from household grain subsidies exerts a positive but insignificant influence on farmers’ GGPE. This implies that, while government-issued grain subsidies, as a policy tool, can provide some positive incentives for farmers to adopt resource-conserving and environmentally friendly production technologies, their overall promotional effect on green grain production practices remains relatively limited. It is insufficient to support farmers in achieving a substantive transition from traditional production models to green production models.

4.2. Analysis of Threshold Effects in the Scale of Service Utilization by Farmers

The above research shows that, in general, SASs significantly improved farmers’ GGPE. However, can the SUFS continue to increase GGPE? Is there a critical threshold? After exceeding the threshold, how will the SUFS affect farmers’ GGPE? This study employs a threshold regression model and the SUFS as the threshold variable to analyze a sample of 729 farmers using SASs. In order to facilitate the determination of the threshold, this study uses the original value to calculate the SUFS.

This study examined the significance of the threshold effect and examined the impact of different SUFSs on the GGPE of farmers (as shown in Table 5). Among the surveyed farmer samples, only a single threshold passed the significance test. The estimated threshold was 8.18, and the 95% confidence interval was [7.67, 8.18]. The double threshold failed the significance test. The threshold regression results show that the threshold of SUFS is 8.18, with a negative effect before and a positive effect after the threshold. This demonstrates that larger land parcel sizes can significantly leverage economies of scale by enabling centralized management of cultivated land. This reduces the unit usage costs of large-scale green agricultural machinery, facilitates the implementation of standardized production processes, and optimizes the allocation efficiency of resources such as water, soil, and fertilizers. This effectively internalizes the additional coordination costs and efficiency losses caused by land fragmentation, thereby laying the foundation for enhancing farmers’ green grain production efficiency.

Table 5.

Threshold regression results.

4.3. Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Government Environmental Regulations

Table 6 shows that GERs have a positive adjustment effect between SASs and GGPE. Specifically, at the 1% and 5% significance levels, the interactions between SASs and both constrained and guided environment regulatory interactions have a significant positive impact. The direction of these effects is consistent with the direction of the main effect, indicating that constrained and guided environmental regulation have significant positive regulating effects on the relationship between SASs and GGPE. The basic principle is consistent with the theoretical analysis; that is, adopting the two-pronged method of constrained and guided environmental regulation can alleviate the constraints and capacity gap in the transformation of farmers’ green grain production. On the one hand, constrained environmental regulations set a clear “bottom line” and “red line” and impose strict restrictions on farmers’ production behavior. Such regulations are usually accompanied by supervision and certification of the production process, which indirectly impose quality restrictions on institutions that provide SASs. This effectively reduces their marginal costs and operational risks, thus improving the quality of services. On the other hand, guided environmental regulation flexibly guides farmers’ green grain production behavior by promoting green technology, organizing technical training, implementing ecological production certifications, and establishing demonstration areas. This method reduces the cognitive barriers and learning costs for farmers in green production technology, and addresses the problem of information asymmetry, which occurs when farmers lack knowledge, familiarity, and understanding of how to utilize green production technology. In addition, the guiding measures for green grain production (green certification, brand building) have significant positive externalities. They enable farmers to obtain the premium of high-quality green products, open up new value-added channels, and offer positive external benefits for individual farmers. This fundamentally stimulates the endogenous motivation of farmers to improve GGPE. The interaction between SASs and incentive regulation is positive but not significant. This may be because government subsidies are directly issued to farmers with farmland contracting rights, rather than to actual farmers, or because subsidies are diluted by land rent. Therefore, even if subsidies can play a certain incentive role, the amount of subsidies may not be enough to support the transformation of actual growers from traditional farming to green production. Farmers have a weak perception of the actual incentives of subsidies and fail to establish an effective incentive mechanism, so they cannot significantly improve their GGPE.

Table 6.

Estimation results of the moderation effect model.

4.4. Robustness Tests

In order to test reliability, this study uses the replacement core explanatory variable method to test the robustness of the regression results. The core explanatory variable SASs is replaced with the proportion of SAS usage segments by farmers relative to the total number of SAS segments. By comparing the test results in Table 7 with the regression results in Table 4, it is found that the robustness test results are basically consistent with the previous empirical results, indicating that the conclusion of this study is robust.

Table 7.

Estimation results for the model.

5. Discussion

In summary, the findings of this study align with the existing literature. First, this study demonstrates that SASs enhance farmers’ GGPE. This confirms that such services serve as a crucial mechanism for promoting the green transformation of smallholder farming and grain production [46]. Through pathways including technology embedding, factor substitution, and service standardization, SASs enable farmers to reduce costs, thereby boosting their green production efficiency. Second, this study reveals a single threshold effect in the scale of service utilization by farmers. This nonlinear relationship highlights the principle of optimal scale prevalent in grain production and management [20]. When service scale reaches the optimal range, SASs leverage economies of scale and resource integration effects to optimize the allocation of grain production factors and enhance chemical utilization efficiency, thereby boosting farmers’ GGPE. Compared to existing research, this study further employs threshold regression models to quantify the optimal scale, deriving specific threshold values. It then proposes tailored policy recommendations for promoting green grain production through distinct pathways based on farm size. Finally, at the policy level, the study confirms that GERs facilitate farmers’ green grain production, aligning with the findings of Guo and Li [47]. However, unlike previous studies, this research further categorizes GERs and conducts detailed analyses of the moderating effects of constrained, incentive, and guided regulations on the impact of SASs on farmers’ GGPE. Constrained regulations directly constrain farmers’ grain production behaviors through supervision and penalties; guided regulations enhance their awareness of green production through promotion and training; while incentive regulations boost production motivation through compensation and rewards. Comparatively, the promotional effects of constrained and guided regulations are more pronounced than those of incentive regulations. Although the impact of different environmental regulation types on farmers’ GGPE varies, their overall direction is positive, indicating that GERs can moderate the impact of SASs on GGPE to a certain extent.

6. Conclusions, Policy Recommendations, and Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

Based on field survey data, this study empirically analyzes the impact of SASs on farmers’ GGPE. It draws the following conclusions: First, SASs help to improve the GGPE of farmers, and the higher the level of SASs, the more significant the promoting effect. This indicates that enhancing utilization of SASs can directly lower the financial, technical, and risk barriers for farmers adopting green technologies. Simultaneously, by improving resource utilization efficiency and output quality, these services help farmers to achieve cost-saving benefits, transforming green production from a high-cost constraint into a profitable choice. Secondly, the scale of farmers’ utilization of SASs shows a clear threshold effect, with a threshold value of 8.18. This indicates that when service scale falls below the optimal level, farmers may face relatively high costs for input factors and technology adoption due to insufficient allocation of fixed costs. However, when service scale exceeds the optimal level, diminishing marginal returns may occur due to increased difficulties in management coordination or reduced resource matching efficiency. Only when service scale falls within the optimal range does service provision reach the critical point for economies of scale. Farmers can then access more stable and efficient services at lower marginal costs, reducing unit output costs. This approach optimizes resource allocation and enhances chemical utilization efficiency. Third, in GERs, at the 1% significance level, both restrictive constrained regulations and guided regulations exert a significant positive moderating effect on the efficiency of SASs and farmers’ GGPE. Meanwhile, the impact of incentive regulations is positive but not significant. This implies that within GERs, constrained regulations internalize environmental externalities by establishing baseline standards and supervising farmers’ production practices. Guided regulations enhance farmers’ awareness of green production through training and information dissemination, thereby reducing information asymmetry. Conversely, the lack of a significant effect from incentive regulations may stem from current subsidy levels failing to sufficiently stimulate farmers’ motivation for green production.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the above conclusions, the following policy recommendations are proposed: First, governments should tailor agricultural social service offerings to meet farmers’ specific needs. It is recommended to establish a national guidance framework and standards for SASs, promoting the creation of a standardized, convenient “menu-based” and “custodial” green service supply system. Local governments should flexibly implement and refine the national service guidance framework based on local agricultural production realities and specific farmer needs. This will achieve cost-effective service provision, reduce transaction costs for farmers seeking and adopting green technologies, enhance farmers’ enthusiasm for SASs, and improve their GGPE. Second, differentiated scale support policies should be formulated for agricultural social services to maximize their economies of scale. Local governments should refine support policies based on regional resource endowments and farmers’ varying operational scales. For small-scale farmers, it is important to encourage village collectives or service alliances to consolidate fragmented service demands into scalable offerings. Additionally, models like “field nannies” or “plowing and planting services” should be adopted to achieve green grain production while ensuring quality and efficiency gains. Governments should also support the transition of large-scale farmers toward comprehensive, integrated, full-process green management services. This leverages economies of scale to solidify practical safeguards for green and sustainable grain production. Third, at the national level, it is recommended that the government strengthens constrained regulations to establish a baseline for green production; deepens guided regulations to foster a green production environment; and optimizes incentive regulations to enhance policy precision and effectiveness. At the local level, governments should establish clearer negative lists and standards, implement strict fertilizer and pesticide reduction initiatives, refine agricultural input usage standards linked to arable land fertility subsidies, strengthen enforcement oversight and traceability management, and impose rigid constraints on non-compliant practices. It is important to implement green technology training programs based on local conditions, making green production techniques core components of training for new professional farmers and skill enhancement for social service providers. Furthermore, governments should identify exemplary green production models to create demonstration effects, shift farmer perceptions, and stimulate intrinsic motivation; reform existing subsidy mechanisms to provide farmers with targeted performance incentives; and directly link portions of subsidy funds to regional green production outcomes (e.g., soil organic matter enhancement, green pest control coverage rates) or service utilization behaviors (e.g., area covered by green farming services), ensuring incentives effectively target critical behavioral change points.

In summary, with SASs as the core carrier, it is possible to improve farmers’ GGPE by optimizing the scale of services. At the same time, the Chinese government should formulate accurate environmental regulations to assist in regulation and encourage farmers to actively participate in SASs. This model integrates small-scale family businesses under the background of China’s “small farmers” into the general pattern of socialized division of agricultural labor, which not only improves the sustainable agricultural production capacity of farmers but is also central to national food security and supporting China’s development into a powerful agricultural country.

6.3. Limitations

This study has certain limitations. For one, the research focuses on China’s top four grain-producing provinces: Heilongjiang, Henan, Shandong, and Jilin. While this focus allows for in-depth analysis of the general patterns of agricultural socialized services’ impact on farmers’ GGPE in major grain-producing provinces, the geographic limitation means we cannot yet comprehensively obtain relevant information from farmers in other major grain-producing regions. Differences in topography, landforms, and resource endowments across China’s regions may lead to inconsistencies in the research findings. The primary reason for this geographical limitation is the extremely high research costs and feasibility constraints associated with obtaining in-depth farmer data across China’s 13 major grain-producing regions. Therefore, this study builds upon existing research foundations, concentrating on representative regions to obtain detailed data. Furthermore, the research content itself has certain limitations. SASs are supplied not only within provinces but also from outside provinces. For measurement convenience, this study did not distinguish the source of SASs. In reality, while inter-provincial supply is limited, it differs from intra-provincial supply. The omission of this aspect in the study stems from the difficulty in quantifying or directly observing factors such as farmers’ subjective preferences and social networks regarding the use of provincial or extra-provincial SASs. The extremely high cost of data collection necessitated trade-offs in the scope and depth of the research, leading to the exclusion of certain potential influencing factors. Consequently, in subsequent research, we plan to expand the scope to China’s 13 major grain-producing regions. This will enable the construction of a more comprehensive framework for analyzing how SASs influence farmers’ green grain production efficiency. We will conduct multi-level analysis involving farmers, organizations, and village collectives to reveal policy transmission chains. However, in this study, we progressively addressed the challenge of missing variables cross-method approaches and complementary data. We conducted a detailed analysis of SAS supply across provinces and explored the heterogeneity of SASs from both intra- and inter-provincial sources. This enables a more accurate and comprehensive study of how SASs influence farmers’ GGPE.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18031371/s1, File S1: data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L. and X.L.; methodology, F.L.; software, F.L.; validation, L.G., X.L. and M.Z.; formal analysis, F.L. and L.G.; investigation, F.L., L.G., X.L. and M.Z.; resources, L.G.; data curation, F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L., X.L. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, F.L. and L.G.; visualization, F.L. and M.Z.; supervision, L.G.; project administration, F.L. and L.G.; funding acquisition, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (18BJY150); the Science and Technology Research Project of the Education Department of Jilin Province (JJKH20250605BS); and the Innovation and Development Strategy Research Project of the Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province (20240701020FG).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the participants are completely voluntarily participating in the survey. The survey questionnaire does not involve personal names and ages. All information is anonymized and only uses numbers to store the farmers’ data. The collected data is only used for academic research purposes, and personal information is absolutely confidential. The “Notice on Issuing the Measures for Ethical Review of Human Life Sciences and Medical Research” issued by the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Article 32 stipulates that research that meets certain conditions can be exempt from ethical review. This research fell into the category of “not causing harm to the human body, not involving sensitive personal information or commercial interests”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SASs | socialized agricultural services |

| GGPE | green grain production efficiency |

| SUFS | scale of utilization of farmers’ services |

| GERs | government environmental regulations |

References

- Jia, F.; Shahzadi, G.; Bourlakis, M.; John, A. Promoting resilient and sustainable food systems: A systematic literature review on short food supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, X.; Dong, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, L.; Qi, X.; Lin, N. Spatiotemporal drivers of agricultural non-point source pollution: A case study of the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, China. J. Environ. Manage 2024, 370, 122606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Y. Impact of fertilizer and pesticide reductions on land use in China based on crop-land integrated model. Land Use Pol. 2024, 141, 107155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, L.; Sun, X. Temporal and spatial evolution of non-point source pollution of chemical fertilizer in main grain producing areas of China. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2024, 38, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, M.; Dai, Y. Mechanization services, technology introduction and technical efficiency in China’s grains production. Commer. Res. 2023, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M. Agricultural productive service industry: The third momentum in Chinese agricultural modernization history. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 3, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.J. The measurement of productive efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1957, 120, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J. Development of green and low-carbon agriculture through grain production agglomeration and agricultural environmental efficiency improvement in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 141128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, V.; Bureau, J.; Butault, J.; Nehring, R. Levels of farm sector productivity: An international comparison. J. Product. Anal. 2001, 15, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ma, L.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Z. The role of agricultural production trusteeship in improving green production efficiency of grain. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 2248–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, P. Study on green production efficiency of grain and its influencing factors in China: A comparative analysis based on the grain functional area. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 36, 116–120. Available online: https://stjj.cbpt.cnki.net/portal/journal/portal/client/paper/a6c148691c557c84bb0bde76502d0689 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Xue, L.; Niu, H.; Cui, W. Spatio-temporal evolution and influencing factors of grain green production efficiency in China under the human capital perspective—A study based on geographic detector. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 9123–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qin, Y.; Xu, J.; Ren, W. Analysis of the evolution characteristics and impact factors of green production efficiency of grain in China. Land 2023, 12, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, Q. Threshold effects of green technology application on sustainable grain production: Evidence from China. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, J. Research on factors influencing green production efficiency of grain and its associative pathways. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 4959–4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J. Study of spatial spillover effects and threshold characteristics of the influence of urbanization on grain green production efficiency in China under carbon constraints. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 56827–56841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, M. How does farmers’ digital literacy affect green grain production? Agriculture 2025, 15, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, J. The impact of agricultural technology services on the efficiency of green grain production: An analysis based on the generalized stochastic forest model. J. Resour. Ecol. 2024, 15, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Li, Y. Mechanism, practice and strategies on promoting the construction of an agricultural power through socialized services. Reform 2024, 83–92. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/50.1012.F.20240702.0913.002 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F. “Consistency” effect or “Seesaw” effect—The impact of agricultural socialization service on grain production and grain planting income. J. Northwest AF Univ. 2025, 25, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Han, X. Analysis on the threshold effect of agricultural socialized service on the “Grain Orientation” of agricultural land. J. Manag. 2022, 35, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, J.; Xu, D. The impact of agricultural socialized service on grain production: Evidence from rural China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Yi, X.; Zhou, L. Impacts of agricultural production services on green grain production efficiency: Factors allocation perspective. J. Environ. Manage 2025, 380, 125136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, L.; Zhang, L. Impact and Spatial Effects of Agricultural Socialization Services on Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 45, 151–160+191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Zhou, W.; Song, J.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Impact of outsourced machinery services on farmers’ green production behavior: Evidence from Chinese rice farmers. J. Environ. Manage 2023, 327, 116843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Rizwan, M.; Abbas, A. Exploring the role of agricultural services in production efficiency in Chinese agriculture: A case of the socialized agricultural service system. Land 2022, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Guo, C.; Cai, B. Agricultural socialized service development and urban-rural income gap under the background of common prosperity—On the threshold effect of rural labor transfer and human capital. Theory Pract. Financ. Econ. 2023, 44, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tong, T.; Chen, Z. Can socialized service of agricultural production improve agricultural green productivity? South China J. Econ. 2023, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Leng, L.; Yang, S.; Lin, X.; Chen, S.; Li, G. Impact of land circulation and agricultural socialized service on agricultural total factor productivity. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 181–189+240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Rao, F.; Zhu, P. The impact of specialized agricultural services on land scale management: An empirical analysis from the perspective of farmers’ land transfer-in. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2019, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Zhang, J. Environmental policies and farmers’ environmental behaviors: Administrative restriction or economic incentive-based on the survey data of farmers in Hubei, Jiangxi and Zhejiang provinces. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 147–157. Available online: https://zgrz.chinajournal.net.cn/WKI/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=50f1c865-0bce-45ad-88c4-e4e15995fb47 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Wang, C.; Gu, H. The market vs. the government: What forces affect the selection of amount of pesticide used by China’s vegetable grower? J. Manag. World 2013, 50–66+187–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, D.; Yu, L.; Yang, H. Influence of a new agricultural technology extension mode on farmers’ technology adoption behavior in China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.; Sun, M.; Wang, L. Decision making of farmers’ black land conservation tillage behavior: Value perception or policy driving? J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 2218–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, E.; Young, M. Integration of environmental concerns into agricultural policies of industrial and developing countries. World Dev. 1992, 20, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yang, L.; Xu, C.; Fu, T.; Lin, J. Exploring the nonlinear association between agri-environmental regulation and green growth: The mediating effect of agricultural production methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cui, H.; Zong, Y.; Yan, Y. Impact of ecological literacy and environmental regulation on farmers’ participation in pesticide packaging waste management: Evidence from 1118 households in Hebei province. Issues Agric. Econ. 2025, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ma, Y. Impacts of agricultural scale operation on the environmental efficiency: An analysis based on land plots data. China Environ. Sci. 2020, 40, 4631–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; He, K.; Zhang, J. The more grain production, the more fertilizers pollution? Empirical evidence from major grain-producing areas in China. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2020, 108–131. Available online: https://zgncjj.ajcass.com/?jumpnotice=201606270007#/search?year=2020&issue=1 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Min, J.; Kong, X. Research development of agricultural non-point source pollution in China. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2016, 59–66+136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of super-efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 143, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z. The impact of agricultural machinery service on technical efficiency of wheat production. Chin. Rural Econ. 2018, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A.; Tan, J. Empowering agricultural resilience by rural industrial integration: Influence mechanism and effect analysis. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2023, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Sample splitting and threshold estimation. Econometrica 2000, 68, 575–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Hou, J.; Zhang, L. A comparison of moderator and mediator and their applications. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 37, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Kong, R. How Do Agricultural Socialized Services Promote Farmers’ Behavior of Emission Reduction and Carbon Sequestration: A Transaction Cost Perspective. Issues Agric. Econ. 2025, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, H. Research on farmers’ pro-environmental behaviors from the dual perspectives of environmental literacy and environmental regulations. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2025, 39, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.