Abstract

Organic food consumption exemplifies the broader shift toward sustainable lifestyles and environmentally responsible choices in the current market generation. Despite the extensive use of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explain consumer purchase intentions, its predictive power for decision making has come into question. This paper aims to enhance the relevance of using TPB in an emerging country to forecast consumer behavior in contemporary conditions. This study set out to investigate the determinants of organic food purchase intention and behavior among South African Generation Y consumers by applying the TPB model. By combining structural equation modeling (SEM) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA), the research could capture both the symmetrical (linear) and asymmetrical (configurational) causal mechanisms underlying purchase intention. While symmetrical results highlight that attitude, subjective norms, and purchase intention predict purchase behavior, asymmetrical findings indicate that no single antecedent is necessary for high purchase intention; rather, two sufficient causal configurations emerge, in which either attitude or perceived behavioral control acts as a core condition, depending on its combination with other antecedents. Attitude and perceived behavioral control thus serve as core conditions leading to high purchase intention among South African Generation Y consumers. In sum, the findings suggest that strengthening pro-environmental attitudes through targeted communication strategies and improving the accessibility and perceived ease of purchasing organic food can serve as practical and implementable pathways to foster more sustainable consumption in emerging markets.

1. Introduction

The intensification of global environmental issues, such as natural resource depletion, climate change, and pollution, has made the notions of sustainability and ethical consumption critical priorities for societies worldwide [1,2]. Increasing awareness of these challenges has prompted consumers to shift from purchasing traditional products to adopting more eco-friendly alternatives and engaging in environmentally responsible practices [3,4]. Environmentally conscious consumers now demonstrate a strong preference for sustainable products and behaviors that promote efficient resource use, environmental protection, and long-term socio-economic well-being [4,5]. This transformation aligns directly with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #12, which advocates for ethical, responsible consumption and production as essential pathways to achieving a more equitable, balanced, and sustainable global future.

The consumption of organic food exemplifies the broader shift towards sustainable lifestyles and environmentally responsible choices. This movement is strongly influenced by society’s growing emphasis on sustainability, ethical consumption, and the recognition of the environmental consequences of individual consumption behaviors [6]. Many consumers now prioritize organic products, acknowledging their role in promoting health and well-being [7] and their close alignment with the implementation of the SDGs, particularly those addressing sustainable agriculture, responsible consumption, and environmental preservation [8].

Although the current consumer market expresses some level of ‘concern’, few consistently purchase organic products, creating an attitude–behavior gap and making organic food still a niche market [4,9,10]. Especially in developing countries, consumers face barriers that prevent them from translating their positive beliefs into actual purchases [11,12]. This is the case in South Africa. As a developing nation with emerging markets, South Africa faces the task of balancing its economic growth and pro-environmental efforts [13]. South African citizens are among those in the world worst affected by the environmental crisis [14,15]. The South African consumer market has been developing a heightened awareness of nutrition and its potential impact on both individual health and the natural environment [16].

As a developing country, South Africa is characterized by pronounced cultural and ethnic diversity, as well as high levels of income inequality and uneven access to goods and services. These contextual characteristics shape consumer decision-making by influencing values, social norms, perceptions of affordability, and access to sustainable products. In such contexts, purchasing behavior is not driven solely by individual attitudes, but is also affected by social influence, cultural identity, and structural constraints related to price sensitivity and product availability. Consequently, sustainable consumption choices, such as organic food purchasing, reflect a complex interplay among cultural norms, economic feasibility, and perceived behavioral control, making emerging markets a particularly relevant setting for examining both linear and configurational drivers of consumer behavior.

Generation Y, also referred to as Millennials, represents a critical consumer segment due to their distinct socio-cultural formation and growing influence on global market dynamics. Born between the 1980s and mid-1990s [10,17], Generation Y consumers exhibit heightened concern for environmental and health issues. They are increasingly motivated to purchase eco-friendly and organic products, reflecting their desire to contribute to sustainability with responsible consumption choices [5,6]. This generational cohort is often characterized by conscientious and socially aware purchasing behavior, making them an essential target for organic food marketing strategies and an important group for understanding sustainable consumption trends in emerging markets [18].

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) by [19] is a well-known theoretical model that is frequently used to forecast consumer behavior [1]. The theory has been used to predict consumer behavior in various fields, including green-oriented consumer behavior [4,20,21,22]. The TPB has four factors that explain behavior that favors such products: (a) the attitude, which refers to a favorable or unfavorable valuation of organic food purchase behavior; (b) the social aspect (or subjective norms), which refers to the individual view and social reference group with respect to the behavior to execute; (c) perceived behavioral control, which refers to the ease or difficulty to execute an action; and (d) purchase intention, which depicts consumer strength to perform or make a decision [23].

The TPB has been applied extensively to predict intentions to purchase organic food [24,25,26,27,28]. Yet, a literature gap still remains if considering: (a) the lack of clarity regarding the determinants that shape consumers’ green purchase decisions, especially in relation to organic food consumption [4,29] in emerging markets [12,30]; (b) insufficient empirical examination of the complex relationship between sustainable intentions and consumption decisions [31]; (c) limited understanding of how the antecedents of these behaviors diverge [32]; and (d) security investigation into Generation Y’s green behavior [10,23].

As such, this study sought to investigate the elements of organic food purchase intentions among South African Generation Y consumers by applying the TPB model. By combining structural equation modeling (SEM) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) techniques, the research aimed to capture both the symmetrical (linear) and asymmetrical (configurational) causal mechanisms underlying purchase intentions. The TPB provides predictive capacity [21], as many recent studies have applied [17]’s theory to analyze green consumers’ intentions and behaviors [1,4,8]. On the other hand, the TPB combined with the complementary perspectives of SEM and fsQCA, can provide a more fine-grained approach to examining the determinants of organic food purchase intentions and behavior among South African Generation Y consumers [33]. This integrated analytical strategy can enhance understanding of how attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control interact to shape purchase intentions and behavior, while also providing valuable insights for marketers and policymakers seeking to promote environmentally responsible consumption [9,30,34].

To address the limitations of purely linear modeling approaches, this study also employs fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). fsQCA is a set-theoretic, case-oriented method grounded in fuzzy logic that allows conditions to be partially present or absent, capturing degrees of membership rather than assuming binary relationships. Unlike symmetric techniques, which estimate average net effects, fsQCA identifies multiple sufficient combinations of conditions (configurations) that can lead to the same outcome, thereby embracing causal asymmetry and equifinality. In this study, fsQCA is used as a complementary analytical approach to uncover distinct configurational pathways leading to high organic food purchase intention among Generation Y consumers, while the detailed calibration procedures and analytical steps are described in Section 3.

After this introductory section, this paper is organized as follows: The next topic presents a literature review, addressing the consumer behavior and sustainability context (Section 2.1), Generation Y (Section 2.2), the TPB (Section 2.3), and the conceptual model for the research (Section 2.4). Section 3 outlines the materials and methods. Section 4 presents the result, followed by the discussion (Section 5). Finally, Section 6 presents the conclusions, and the sources used are listed subsequently.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Behavior and Sustainability Context

There is currently a growing market for sustainable and environmentally friendly products, as sustainability and ethical consumption have become increasingly important to consumers. Ethical food consumption encompasses a broad set of moral principles that guide individuals to evaluate the societal and environmental consequences of their dietary choices. It expands the discussion beyond material resource use to include considerations of moral responsibility, animal welfare, fairness in labor, and broader social justice concerns [5]. As consumers become more aware of the social and ecological implications of their food purchases, ethical consumerism gains prominence, reflecting decisions driven by personal and moral beliefs rather than solely economic motivations [29]. Within this context, the ethical eating movement encourages individuals to choose foods that they believe will bring positive change to the food system, including organic, plant-based, fair trade, and locally sourced products [35]. It also includes a high regard for ecological sustainability and care for farmers’ and animals’ welfare [36].

Ethical consumption behavior can take many forms, including purchasing ethically aligned products, paying premium prices for them, boycotting unethical brands, and reducing unsustainable consumption practices [37]. Scholars increasingly conceptualize ethical consumption as a holistic process involving pre-purchase evaluations, responsible use, and post-consumption disposal, highlighting a heightened awareness of the environmental and social, and economic consequences of consumption [38]. Moreover, the continued growth of ethical consumption has been supported by globalization, civic engagement, technological advancements, and effective market campaigns, all of which collectively reinforce consumers’ moral orientation in food decision-making [38].

Buying organic food products can be seen as a form of ethical consumption because these products are produced without using harmful chemical pesticides and/or growth hormones, bioengineering, ionizing radiation, artificial fertilizers, or sewage sludge [29,39,40]. Organic food consumption is strongly linked to enhanced quality of life, generating positive emotions, inner assurance, and increased self-confidence among consumers [41]. Consumers prefer organic products because they are perceived as ‘natural’, containing fewer unhealthy substances, allergens, artificial additives, salt, and fat, while offering higher levels of vitamins and minerals [6]. As global concern over pollution, illness, and environmental deterioration grows, organic food has become increasingly important for sustainable consumption, prompting consumers worldwide to adopt organic products as a form of environmental protection [3].

Organic foods are considered more sustainable due to differences in production methods, resource use, and environmental impact compared to conventional foods [6]. Producers also benefit from the organic market because it offers higher incomes and supports sustainable development [39]. Organic agriculture relies on ecological protection technologies, regulated standards, crop rotation, proper certification, and informed labeling practices across the entire value chain [8]. Organic practices also enhance biodiversity, improve soil quality, reduce ecological risks, and decrease consumers’ exposure to pesticides, positioning organic farming as a long-term pathway to more sustainable and health-supportive food systems [7].

In developed markets such as Europe and North America, organic food marketing is characterized by mature regulatory frameworks, high consumer awareness, and well-established retail infrastructures that support premium pricing and sophisticated branding strategies [11]. Consumers in these regions are generally motivated by strong environmental values, health consciousness, and trust in certification systems, enabling companies to position organic products as mainstream lifestyle choices [40]. In contrast, in emerging markets like South Africa, organic food marketing operates in a context of lower consumer awareness, greater price sensitivity, and limited accessibility [12]. Recent studies have adopted the South African case to study purchase intentions of green products [13], green beauty products [15], and organic personal care products [16]. However, none has addressed Generation Y’s influence on the organic food market as in this paper.

2.2. Generation Y (Sustainable) Consumer Behavior

When individuals are exposed to the same economic, societal, cultural, and political experiences during their formative years, their values, beliefs, and consumption patterns are shaped throughout life in a similar manner forming a “generational cohort” [5]. The Generation Y cohort are individuals born between 1986 and 2005, according to [14]. In 2024, the Generation cohort in South Africa made up 33% of the country’s population [42]. This cohort possesses a large amount of spending power.

An essential factor in promoting sustainability is the focus on encouraging environmentally friendly consumer behavior and aspirations to make green purchases, especially among Generation Y [18,29,43,44]. Generation Y consumers are often early adopters of emerging green technologies, and they demonstrate an eager drive to use environmentally friendly products [29]. This cohort plays a pivotal role in shaping lifestyles that align with both personal preferences and broader environmental considerations [23]. Their food choices are influenced not only by self-expression and socio-cultural values but also by a commitment to environmental stewardship [10].

Studies consider members of Generation Y to be intelligent, digital natives, and cynical of conventional marketing approaches. Also, they are more diversified in ethnicity and culture, and their media use is more fragmented [23]. Digital connectivity embodies this generation’s consumption preferences. Social media platforms expose them regularly to sustainability narratives and ethical consumption models via content created by eco-conscious brands, environmental influencers, and even fast fashion advocates [5]. In sum, they are the agents of change in the modern-day green movements [16,45]. This group is anxious about the future and concerned with safety, social equality, and environmental sustainability [6]. They are in pursuit of brand authenticity in addition to social validation and ethical transparency [10].

As stated in Section 1, the TPB is used extensively across multiple contextual studies [19]. In this study, the TPB is adopted to understand the complex nature of Generation Y’s green behavior with respect to green food.

2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior

The TPB framework is most commonly used to explore the process of organic food purchase intention and behavior [4,20,32,46,47].

Purchase behavior is understood as the process by which a consumer integrates affective, cognitive, and behavioral aspects as they relate not only to consumption but are also linked to beliefs, attitudes, and values [48]. From the standpoint of consumer behavior, choosing organic products extends beyond price and availability, encompassing ethical and practical considerations regarding their effects on health and environmental sustainability [34]. Organic food purchase is a way to protect the environment, live a healthy life, and encourage long-term sustainability [6]. Therefore, it is crucial to consider that consumer behavior influences the demand for organic food [21]. The intention of the person shapes behavior and includes the motivating factors that affect the behavior [49].

Purchase intention refers to the possibility that individual customers will make a purchase in the future [29]. For [50], intention is an indicator of readiness to perform. For this reason, several authors use intention as an important predictor of behavior [51,52,53,54]. As previously mentioned, the intention of the younger generations to purchase green and healthy products has become more apparent, as the customers’ value orientation towards green products is becoming more positive, increasing the possibility of ethical consumption [21].

The inability of the theory of reasoned action’s (TRA) to predict human behavior based on perceived behavioral control, which is considered a specific case for TPB [6,19], led to the development of the TPB. The TPB posits that human behavior is shaped by an individual’s intentions to act in a particular manner and their perceived control over performing that behavior [19,47,55]. Within this framework, intentions are regarded as the most significant predictor of behavior and are influenced by three key determinants [31]. First, attitudes toward the behavior reflect an individual’s overall positive or negative evaluation of performing the behavior [19,56,57]. Second, subjective norms capture the perceived social pressure from significant others to engage in the behavior [4,19,32,47]. Third, perceived behavioral control refers to an individual’s assessment of the extent to which internal or external factors may facilitate or hinder the performance of the behavior [3,19].

Environmental attitudes consistently emerge as one of the most influential predictors of organic food purchase intention, as they shape consumers’ positive or negative evaluations of environmentally friendly products and thereby guide their behavioral choices [4,12]. Attitude functions as a central antecedent of green consumption, reflecting consumers’ acceptance of innovation and their evaluative judgment of organic products, which strongly determines their willingness to buy [22,30]. Evidence further shows that attitudes towards organic food reliably predict buying intention because they represent individuals’ psychological assessment processes where positive expectations serve as motivation for environmentally responsible decision making [9,40]. Thus, consumer attitudes towards green products serve as a key driver of green purchase intention [50] and partially explain sustainable consumption behaviors under the TPB. The predictive power of the TPB has been reaffirmed across disciplines [46,58].

In addition, subjective norms arise from the support or pressure consumers perceive from others regarding environmentally responsible choices. It consistently shapes their intentions to purchase eco-friendly and organic products [3,4,19,30]. Although some studies report inconsistent findings, showing either direct, indirect, or mediated effects of subjective norms on organic food purchase intention, evidence nevertheless demonstrates that normative influence can significantly motivate sustainable behavior and reinforce green purchasing decisions [9,40,47]. For Generation Y, subjective norms exert an even stronger influence because social approval is increasingly filtered through digital interactions, meaning that peer behavior, online communities, and especially social media endorsements play a powerful role in shaping perceptions of what is socially expected or valued [34]. These digital normative cues amplify group identity and strengthen conformity to pro-environmental behaviors, making subjective norms a particularly salient driver of Generation Y’s intentions to purchase organic products [6,22,59].

Finally, perceived behavioral control captures consumers’ sense of control over purchasing environmentally friendly products, meaning that individuals who believe they possess sufficient knowledge, financial means, time, and access to green alternatives are more likely to form strong intentions to engage in sustainable purchasing [6,19,30]. Empirical evidence shows that perceived behavioral control significantly enhances intentions to buy green and organic foods, especially when product availability, convenience, and supportive conditions reduce perceived barriers [3,9]. This construct exerts a direct influence on green behavioral intentions because consumers who perceive high control feel more capable of translating their pro-environmental motivations into action [32]. In emerging contexts such as South Africa, perceived behavioral control becomes even more important given structural challenges such as uneven access to certified organic products, price sensitivity, and variability in environmental awareness [13]. Thus, when South African consumers perceive adequate access, availability, and resources to purchase organic and green-packaged foods, their intention to engage in sustainable consumption is substantially strengthened, positioning perceived behavioral control as a decisive factor in overcoming contextual constraints and enabling green purchasing behavior [15].

2.4. Research Conceptual Model

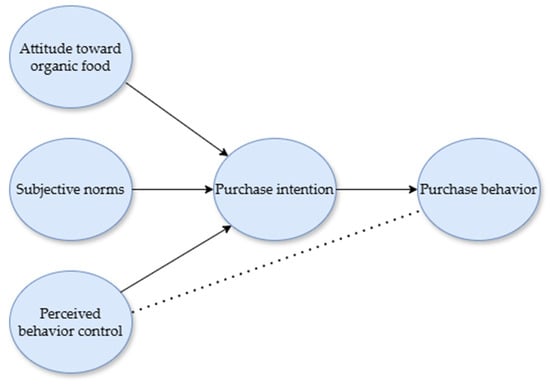

Based on the above, intention to purchase organic food can arise from both linear and configurational patterns for South African Generation Y consumers as predicted by the TPB. While attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control can exert significant (in)direct influence on purchase intention and, consequently, effective behavior, distinct combinations of antecedents can also constitute sufficient causal paths toward strong purchase intentions and behaviors. Against this backdrop, we state the following research propositions:

Proposition 1.

Attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control jointly influence purchase intention and behavior among South African Generation Y consumers of organic food.

Proposition 2.

Distinct combinations of these antecedents are sufficient for strong purchase intention and behavior among South African Generation Y consumers of organic food.

Figure 1 illustrates our conceptual empirical model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual empirical model.

3. Materials and Methods

This study, grounded in a positivist research paradigm, employed a cross-sectional design. Data were collected using a non-probability convenience sampling strategy.

3.1. Sampling Methods

The target population of this study comprised Generation Y consumers currently residing in the Republic of South Africa. Generation Y consumers are defined as individuals born between 1986 and 2005 [14]. This cohort was selected due to their influence on current market trends and growing concerns about sustainability and ethical food consumption patterns. An online survey method was chosen to collect the data, which was conducted by the globally recognized research firm IPSOS South Africa, using a pool panel of roughly 40,000 respondents. IPSOS is a research firm renowned for its methodological rigor and representative sampling capabilities. The survey was distributed online via IPOS’ FastFacts program, which ensures high survey completion rates as respondents are required to complete all questions on a page before proceeding to the next page. The survey remained active for five consecutive days, ensuring timely data collection while maintaining demographic diversity across age, gender, and geographic location. To account for the model complexity criterion, a sample size of 500 voluntary respondents was deemed acceptable, as advised by [60].

3.2. Research Instrument

The online survey was administered in the form of a structured electronic questionnaire, designed to systematically capture the required data from respondents. On the questionnaire’s cover page, an introductory section outlined the purpose and objectives of the study and assured respondents of their anonymity as they participate in the study. The next section captured respondents’ demographic information, and thereafter, all scaled response constructs adapted from existing literature followed. All scaled response items were measured using a six-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The use of a scale that excluded the neutral midpoint was deliberate, as prior studies suggest that this may reduce central tendency bias and encourage decisive responses [61].

The TPB constructs measured in this study included attitudes towards organic food products (four items) [62], subjective norms (three items) [63], perceived behavior control (five items) [64], purchase intention (three items) [65], and purchase behavior (four items) [38].

3.3. Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 30) and the Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) software, versions 30, were used for the SEM quantitative analysis in this study. Furthermore, fsQCA was used to provide configurational insight into the data set. Initial data computations included frequency distributions and percentage analyses to describe the sample demographics. The study performed a common method bias test and conducted Pearson’s bivariate correlation analysis to ensure data integrity and validity. Collinearity diagnostics were used to assess nomological validity and identify potential concerns related to multicollinearity. The measurement model was assessed through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and the structural model was tested using path analysis via the maximum likelihood estimation method. In parallel, fsQCA was employed to identify multiple causal configurations that lead to high levels of organic food purchase intention among Generation Y consumers. This dual-method approach enabled both the identification of statistically significant relationships and the exploration of complex, nonlinear patterns of behavior, thereby enhancing the robustness and depth of the findings.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The selected sample included 500 responses. The sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Sample demographics.

Table 1 shows that all responses fell within the Generation Y age bracket of 18–35, with the highest representation among 27–29-year-olds, followed by 30–32-year-olds. In terms of gender, the dataset was relatively evenly split between males (49%) and females (51%). Additionally, 31% of respondents indicated that English is their first language. Geographically, Gauteng was represented most, with 41% of respondents residing there, followed by KwaZulu-Natal at 16%.

The scaled-response items and statistics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Scaled-response items and descriptive statistics.

All recorded means were well above the middle threshold of 3.0. The largest mean recorded was that of perceived behavior control (mean = 5.01), followed by attitude towards organic food products (mean = 4.95). The remaining constructs yielded high mean values, indicating that South African Generation Y consumers generally hold positive views of organic food products.

4.2. Quantitative Assessment: SEM

In order to assess if any common method bias was present in the data set, Harmon’s one-factor test was conducted using a single factor extraction by principal axis factoring. The single factor accounted for 48.20 percent of the variance, which is below the 50 percent limit [66]. This indicates that there are no concerns about common method bias.

Table 3 below presents the results of the Pearson product-moment correlation analysis, which was used to assess the nomological validity of the measurement model. Additionally, collinearity diagnostics, including tolerance values and variance inflation factors (VIFs), were conducted to identify multicollinearity. The results of both analyses are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis and collinearity diagnostic results.

The correlation coefficients between each pair of latent factors in the measurement model are statistically significant (p ≤ 0.01) and positive, consistent with theoretical expectations and supporting nomological validity [60,67]. Additionally, no major concerns regarding multicollinearity were detected, as all tolerance values exceed 0.10 and all variance inflation factors (VIFs) are below 5 [67,68].

The measurement model was examined using CFA, both to assess the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument and because the construct indicators were adapted from multiple sources. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Measurement model results.

The measurement model yielded standardized factor loadings above 0.50 for all indicators, and their respective error loadings fell within the range of 0 to 1. Furthermore, all average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded the 0.50 threshold, indicating the absence of Heywood cases and simultaneously confirming convergent validity [67,69,70]. The model displayed discriminant validity, as none of the HTMT ratios surpassed the 0.85 threshold, and all the square roots of the AVEs were greater than the correlation between the constructs [60,71].

Internal consistency reliability and composite reliability were confirmed by a and composite reliability (CR) values greater than 0.70 for measuring constructs [60,72]. The model fit was deemed good with the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), normed fit index (NFI), and relative fit index (RFI) fit index all above 0.90, and both the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) indices below 0.08 [67,73,74]. Based on the evaluation of the measurement model’s attributes, structural modeling can now proceed, as the measurement model has been successfully validated. The structural results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Path analysis results.

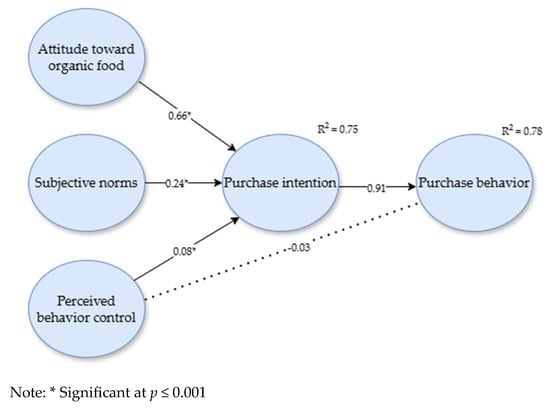

Although perceived behavioral control did not exhibit a statistically significant direct effect on purchase intention (H3) or purchase behavior (H4) in the SEM analysis, this result suggests that perceived behavioral control is not a universal linear predictor among South African Generation Y consumers. In emerging market contexts, external constraints such as price sensitivity, uneven access to organic products, and structural limitations may weaken the average net effect of perceived control. Importantly, this finding does not imply that perceived behavioral control is irrelevant; rather, it suggests that its influence may be contingent upon specific combinations of conditions, as further supported by the fsQCA results (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Complete empirical model.

4.3. Configurational Analysis: fsQCA

Following established fsQCA guidelines, the analysis was conducted using the direct calibration method. Latent variable scores obtained from the SEM were transformed into fuzzy-set membership scores ranging from 0 (full non-membership) to 1 (full membership). For each construct, three qualitative anchors were specified: full membership (0.95), the crossover point (0.50), and full non-membership (0.05). The thresholds for full membership and non-membership were set at the 95th and 5th percentiles, respectively, while the crossover point represents the point of maximum ambiguity, where cases are neither clearly in nor out of the set.

After calibration, truth tables were constructed using attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control as antecedent conditions and purchase intention as the outcome. Consistency thresholds of 0.80 were applied to identify sufficient configurations, in line with prior fsQCA research, while conditions with consistency values above 0.90 were considered necessary. Coverage metrics were used to assess the empirical relevance of each configuration. This systematic calibration and threshold selection ensured analytical rigor and facilitated the identification of multiple configurational pathways leading to high purchase intention.

SEM enables estimation of the average effects of input factors on outcome variables and assessment of their statistical significance. Its coefficients indicate the overall influence that each independent variable exerts on the dependent variable. In contrast, fsQCA uses a case-oriented approach: rather than quantifying the impact of explanatory factors through coefficients, it uncovers multiple configurations of input conditions that can jointly lead to a given outcome [9,75,76,77].

fsQCA was conducted using the latent variable scores obtained from the SEM to complement the linear analysis. Table 6 reports the calibrated fuzzy-set membership scores for each construct.

Table 6.

Calibration.

Following calibration, truth tables were constructed to examine all possible configurations that led to high levels of purchase intention (PI), using attitude (ATT), subjective norms (SN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC) as antecedent conditions. Table 7 presents the resulting truth table, including the frequency, raw consistency, PRI consistency, and SYM consistency values.

Table 7.

Truth table.

The analysis of necessary conditions aimed to identify whether any single antecedent was indispensable for high purchase intention. Following [78], a condition is considered necessary when its consistency exceeds 0.90. As shown in Table 8, none of the antecedents met this threshold, indicating that no single condition is necessary for the outcome. This suggests that high purchase intention arises from combinations of conditions rather than isolated effects.

Table 8.

Necessary condition analysis.

The analysis of sufficient configurations sought to identify different causal paths that led to high levels of purchase intention. Only configurations with a consistency above 0.80 and coverage above 0.20 were retained [78,79]. Two sufficient solutions were identified (Table 9).

Table 9.

Configuration of EE for high levels of PI.

The first configuration highlights attitude as a core condition. According to the truth table, 28 individuals had high purchase intention with only high attitude, even without high subjective norms or perceived behavioral control. Additionally, another 17 individuals reached high purchase intention through a combination of high attitude and high subjective norms, but low perceived behavioral control.

The second configuration emphasizes perceived behavioral control as the main driver. Here, 17 individuals exhibited high purchase intention with high only perceived behavioral control, while 20 others showed high purchase intention when both perceived behavioral control and subjective norms were high, despite low attitude. Thirty individuals had a high purchase intention when both perceived behavioral control and attitude were high, despite low subjective norms.

Although the SEM results did not confirm a significant direct effect of perceived behavioral control on purchase intention (H3 rejected), the fsQCA analysis provides complementary insights by showing that perceived behavioral control can still play a role within specific causal configurations. This apparent divergence reflects the fundamental methodological differences between symmetric (SEM) and asymmetric (fsQCA) approaches rather than a substantive contradiction.

In particular, while no single antecedent was found to be necessary for high purchase intention, two distinct sufficient configurations emerged. The first highlights attitude as a core condition leading to high purchase intention even in the absence of high subjective norms or perceived behavioral control. The second configuration shows that high purchase intention can also arise from the combination of high perceived behavioral control and high subjective norms, despite a lower attitude.

These findings suggest that perceived behavioral control, although not linearly significant in the SEM model, contributes to behavioral intention when acting jointly with other conditions. This reinforces the idea that consumer decision making is complex and context-dependent and supports the principle of equifinality [77], where the same outcome can result from multiple distinct causal paths. The fsQCA thus complements the SEM results by revealing nonlinear interactions and individual-level heterogeneity that linear models cannot capture.

5. Discussion

Green purchasing behavior has become a hot topic due to the benefits it has for society at large [10,23,30]. This study addresses green behavior by investigating the determinants of organic food purchase intention and behavior among South African Generation Y consumers. In line with the TPB and supported by the combined SEM-fsQCA analysis, the determinants of organic food purchase intention among South African Generation Y consumers are both additive and configurational.

Consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior, purchase intention emerged as a strong predictor of purchase behavior, reinforcing the premise that intentions represent motivational readiness and translate into actual consumption decisions. This finding aligns with prior research on green and organic consumption, where intention is typically the most proximal antecedent of behavior.

Attitude showed the strongest positive association with purchase intention, suggesting that favorable evaluations of organic food play a central role in the formation of purchase intention among Generation Y consumers. This result is consistent with previous studies that identify attitude as a key driver of green and organic purchase intentions, particularly among younger cohorts who place a high value on sustainability-related consumption outcomes.

Subjective norms also significantly predicted purchase intention, indicating that perceived social approval and social influence contribute to sustainable consumption decisions. This finding aligns with research highlighting the importance of peer influence, social expectations, and digitally mediated norms in shaping environmentally responsible behavior among Generation Y consumers.

In contrast, perceived behavioral control did not show a statistically significant direct effect on purchase intention or purchase behavior in the SEM model. This suggests that perceived behavioral control does not operate as a universal linear predictor in this context. In emerging market settings such as South Africa, structural constraints—such as price sensitivity, uneven access to organic products, and availability limitations—may weaken the average net effect of perceived control. Similar non-significant effects of perceived behavioral control have been reported in other sustainability-oriented consumption studies, suggesting that control beliefs may lose explanatory power when external barriers dominate decision-making.

SEM results reveal that purchase intention is a very strong predictor of behavior. Attitude is a strong linear predictor of intention, while social norms are also a modest but significant antecedent. Perceived behavioral control is not significant for intention, nor for behavior. In contrast, the fsQCA findings indicate (i) attitude as a core condition leading to high purchase intention, either alone or in combination with subjective norms or perceived behavioral control, and (ii) perceived behavioral control as a core condition. This shows that high purchase intention can also arise when perceived behavioral control is combined with subjective norms or attitude, despite perceived behavioral control’s non-significance in the SEM model.

As expected, and in line with prior works in the literature, purchase intention serves as the primary determinant of purchase behavior. Hence, the greater the purchase intention, the greater the purchase behavior [19,29]. From this finding, we can affirm that Generation Y consumers not only have intention but also purchase organic food. From our research conceptual model, attitude can be considered a central psychological driver of organic food intention among South African Generation Y consumers. Further, the dominance of attitude in predicting purchase intention means that high intention can emerge even when subjective norms or perceived behavioral control are low. With this finding, this study aligns with previous scholars. Research confirmed that having a positive attitude towards green products significantly predicts the willingness to use them [4]. Similarly, that attitude directly and significantly affected the intention to purchase organic food in Iran [40].

In this study, social norms also amplify intention, especially when supported by strong attitudes or high perceived control, reflecting the importance of social approval, peer influence, digital communities, and cultural dynamics [3] in South Africa. It indicates that for Generation Y, consuming organic food has become a societal norm in the country [40]. In an assessment conducted by [30] in Turkey, subjective norms affected green purchasing behavior. However, there was a paradox with respect to perceived behavioral control. It was not significant from SEM but appeared as a core sufficient condition from fsQCA (Path 2). In other words, although perceived behavioral control does not influence intention on average, by a symmetrical logic, for specific consumer segments, high perceived behavioral control is enough to generate high intention even with low attitude or low subjective norms. Perceived behavioral control is therefore not a universal predictor but works for specific configurations of consumers. In this study, perceived behavioral control performed contrary to what the TPB expects. This also happened in a study by [32], who investigated the Slovenian case and did not find perceived behavioral control to be an antecedent to environmentally and socially responsible sustainable consumer behavior. In our study, the perceived control is possibly related to the obstacle of the emerging economy of South Africa. It is common in developing countries for perceived behavioral control to lose predictive power when structural barriers make ‘control’ externally constrained rather than internally felt [40]. Further, maybe Generation Y motivation (attitude) matters more than feasibility (perceived behavioral control) [29].

In synthesis, we can affirm, from our sample, that organic food consumers are not homogeneous. People arrive at sustainable choices for different reasons, and there is no single best explanation for purchase intention. Reducing barriers to intention formation may be more important than focusing on behavior directly. In this scenario, policies and marketing strategies must account for multiple consumer segments and behavioral routes.

Implications and Contributions

Theoretically, the paper supports the TPB, especially regarding the positive influence of attitude and subjective norms in intention. At the same time, despite remaining valuable, the TPB linear assumptions can obscure important consumer heterogeneity, and a single method cannot capture the full complexity of sustainable consumer behavior. This study addressed this limitation by employing fsQCA and advanced methodological pluralism in consumer behavior research. This supports arguments for causal complexity in TPB applications.

In this sense, methodologically, this study advances the TPB model by employing a mixed-method technique, as we introduced the fsQCA technique and combined it with SEM for a mixed-method approach. In other words, from the perspective of causal complexity, this paper identified multiple path-equivalent mechanisms for organic food intentions and purchase behavior, thereby enhancing both explanatory power and practical relevance [80].

An understanding of organic food consumer behavior can lead to more developed marketing strategies and production processes [40]. Thus, as implications for practitioners, we advocate that campaigns should focus on strengthening attitudes. Considering the sophisticated profile of Generation Y, sustainable marketing has the challenge of highlighting the health and environmental benefits of organic food [6,29] for this target. Additionally, marketing campaigns should emphasize attitude-building communications because attitude is the strongest linear predictor. Leveraging social influence (digital communities, influencers, and group norms) is also an interesting option to strengthen subjective norms among Generation Y. Also, as perceived behavioral control appears in sufficient configurations, improving accessibility, affordability, and perceived ease of purchase (wider distribution, price promotions, and clear labeling) can activate purchase intentions in particular segments even when attitudes are weaker.

It is worth mentioning that policymakers have a central role in promoting ecological consciousness, enforcing sustainable regulations [18,59], and formulating appropriate strategies to support sustainable economic growth [30]. It is also imperative to increase consumer/citizen awareness and provide incentives to strengthen individual responsibility through education [81]. Finally, regarding the SDG Agenda, this study identifies psychological and contextual levers (attitude, social norms, and perceived behavioral control) that increase organic-food purchasing—a concrete pathway toward more sustainable consumption patterns, as stated in SDG #12.

6. Conclusions

Aiming to investigate the determinants of organic food purchase intentions among South African Generation Y consumers by applying the TPB, this study combined SEM and fsQCA techniques to capture both the symmetrical and asymmetrical causal mechanisms underlying purchase intention. Results show that attitude and subjective norms significantly predicted purchase intention, while perceived behavioral control did not have a direct linear effect. Nonetheless, fsQCA revealed that perceived behavioral control functioned as a core condition in several sufficient causal configurations, highlighting the presence of multiple pathways that lead to high purchase intention. This methodological association underscores the complexity of consumer decision making in emerging markets and demonstrates the value of combining linear and nonlinear analytical approaches.

From a policy perspective, the findings suggest several practical and implementable actions to promote sustainable consumption among Generation Y consumers in South Africa. First, public policies should prioritize attitude-building interventions, such as nationwide awareness campaigns and sustainability education programs that emphasize the health, environmental, and social benefits of organic food consumption. Second, policymakers can leverage social norms by supporting community-based initiatives, public endorsements, and partnerships with trusted opinion leaders to normalize sustainable food choices. Third, improving perceived behavioral control requires reducing structural barriers through targeted measures such as supporting local organic producers, expanding distribution channels in urban and peri-urban areas, and offering incentives that improve affordability and accessibility. Together, these policy actions can foster more favorable conditions for organic food consumption and contribute to the advancement of responsible consumption patterns in emerging market contexts.

Despite the methodological rigor, the study has limitations. First, the use of nonprobability convenience sampling limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader South African population. Second, the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to infer causality or capture temporal changes in sustainable consumption behavior. Third, self-reported measures may be subject to social desirability bias, particularly in the context of environmentally oriented behaviors. Additionally, the study focuses exclusively on Generation Y, which may overlook important intergenerational differences in organic food consumption patterns.

Future studies are invited to address these limitations by employing probability-based sampling or longitudinal designs to assess behavioral stability over time. Comparative studies across generational cohorts or between developing and developed markets would deepen understanding of cultural and socio-economic influences on organic food purchasing. Further investigations may also extend the TPB by incorporating contextual moderators (such as price sensitivity and product availability, among others) or additional psychological constructs (such as environmental concern, moral norms, or perceived consumer effectiveness). Finally, mixed-method designs combining qualitative insights with configurational analysis may offer richer explanations for the heterogeneity observed in sustainable consumption behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; methodology, C.S. and N.B.d.P.; software, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; validation, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; formal analysis, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; investigation, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; resources, C.S.; data curation, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; writing—review and editing, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; visualization, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; supervision, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; project administration, C.S., N.B.d.P. and G.H.S.M.d.M.; funding acquisition, C.S. and N.B.d.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the WorkWell research entity of the North-West University. They provided funding to collect the data.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research received ethical clearance from the Economic and Management Sciences Research Ethics Committee (EMS-REC) at North-West University, South Africa (reference: NWU-00567-20-A4). The approval was granted on 26 February 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in the study and were assured that their identities would remain confidential.

Data Availability Statement

Due to data protection requirements in South Africa and the access restrictions set by North-West University’s EMS-REC, the dataset used in this research cannot be made openly available. Nonetheless, the corresponding author may share the data upon reasonable request, provided that such disclosure complies with the relevant ethical and legal standards.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AMOS | Analysis of Moment Structures |

| ATT | Attitude |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| fsQCA | fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio of Correlations |

| IFI | Incremental Fit Index |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| PB | Perceived Behavioral |

| PBC | Perceived Behavioral Control |

| PI | Purchase Intention |

| PRI | Parsimony Ratio Index |

| RFI | Relative Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SN | Subjective Norms |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| SYM | Symmetry Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| TRA | Theory of Reasoned Action |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factors |

References

- Laheri, V.K.; Lim, W.M.; Arya, P.K.; Kumar, S. A Multidimensional Lens of Environmental Consciousness: Towards an Environmentally Conscious Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2024, 41, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Pan, J. The Investigation of Green Purchasing Behavior in China: A Conceptual Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and Self-Determination Theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shan, B. Exploring the Role of Health Consciousness and Environmental Awareness in Purchase Intentions for Green-Packaged Organic Foods: An Extended TPB Model. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1528016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, M. Understanding the Drivers of Green Consumption: A Study on Consumer Behavior, Environmental Ethics, and Sustainable Choices for Achieving SDG 12. SN Bus. Econ. 2024, 4, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halibas, A.; Akram, U.; Hoang, A.-P.; Thi Hoang, M.D. Unveiling the Future of Responsible, Sustainable, and Ethical Consumption: A Bibliometric Study on Gen Z and Young Consumers. Young Consum. 2025, 26, 142–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.R. A Longitudinal Study on Organic Food Continuance Behavior of Generation Y and Generation Z: Can Health Consciousness Moderate the Decision? Young Consum. Insight Ideas Responsible Mark. 2023, 24, 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roushan, K.; Om, S. Green on the Rise: Urban Appetites for Organic Vegetables in India. Naveen Int. J. Multidiscip. Sci. (NIJMS) 2025, 1, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaluk, O.; Yatsenko, O.; Zakharchuk, O.; Ovcharenko, A.; Khrystenko, O.; Nitsenko, V. Dynamic Development of the Global Organic Food Market and Opportunities for Ukraine. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M. Applying a Combination of SEM and FsQCA to Predict Tourist Resource-Saving Behavioral Intentions in Rural Tourism: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EL, L. Sustainable Food Habits Among Generation X and Generation Y: Exploring Generational Differences. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2025, 27, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B. Factors Affecting Adoption of Green Products among Youths: A Conceptual Framework Based on Evidence from India. Int. J. Indian Cult. Bus. Manag. 2016, 13, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, S.M.; Rūtelionė, A.; Bhutto, M.Y. The Role of Environmental Values, Environmental Self-Identity, and Attitude in Generation Z’s Purchase Intentions for Organic Food. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2024, 80, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, H.; Bhatti, W.A.; Chwialkowska, A.; Marais, T. Factors Influencing Green Purchases: An Emerging Market Perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan-Dye, A.L. Perceived Value and Purchase Influence of YouTube Beauty Vlog Content Amongst Generation Y Female Consumers. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 2024, 1455264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan-Dye, A.L.; Synodinos, C. Antecedents of Consumers’ Green Beauty Product Brand Purchase Intentions: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupindo, M.; Madinga, N.W.; Dlamini, S. Green Beauty: Examining Factors Shaping Millennials’ Attitudes toward Organic Personal Care Products in South Africa. Eur. J. Manag. Stud. 2024, 29, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masserini, L.; Bini, M.; Difonzo, M. Is Generation Z More Inclined than Generation Y to Purchase Sustainable Clothing? Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 175, 1155–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, B.; Jafarian, A.; Abdi, Z. Nudging towards Sustainability: A Comprehensive Review of Behavioral Approaches to Eco-Friendly Choice. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zulkepeli, L.; Fauzi, M.A.; Mohd Suki, N.; Ahmad, M.H.; Wider, W.; Rahamaddulla, S.R. Pro-Environmental Behavior and the Theory of Planned Behavior: A State of the Art Science Mapping. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2024, 35, 1415–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Escobar-Farfán, M.; Gómez-Bayona, L.; Moreno-López, G.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Gallardo-Canales, R. Influence of Environmental Awareness on the Willingness to Pay for Green Products: An Analysis under the Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in the Peruvian Market. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1282383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.F.; Susainathan, S.; George, H.J.; Parayitam, S. Green Consumption and Sustainable Lifestyle: Evidence from India. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O. Factors Influencing Generation Y Green Behaviour on Green Products in Nigeria: An Application of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2022, 13, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Qalati, S.A.; Naz, S.; Rana, F. Purchase Intention toward Organic Food among Young Consumers Using Theory of Planned Behavior: Role of Environmental Concerns and Environmental Awareness. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 796–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.F.; Barbosa, B.; Cunha, H.; Oliveira, Z. Exploring the Antecedents of Organic Food Purchase Intention: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Hameed, I.; Akram, U. What Drives Attitude, Purchase Intention and Consumer Buying Behavior toward Organic Food? A Self-Determination Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 2572–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Algezawy, M.; Elshaer, I.A. Adopting an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour to Examine Buying Intention and Behaviour of Nutrition-Labelled Menu for Healthy Food Choices in Quick Service Restaurants: Does the Culture of Consumers Really Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.-W.; Akter, N.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M. Organic Foods Purchase Behavior among Generation Y of Bangladesh: The Moderation Effect of Trust and Price Consciousness. Foods 2021, 10, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armutcu, B.; Zuferi, R.; Tan, A. Green Product Consumption Behaviour, Green Economic Growth and Sustainable Development: Unveiling the Main Determinants. J. Enterp. Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2024, 18, 798–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, A.I.; Hurriyati, R.; Wibowo, L.A.; Monoarfa, H. Consumers in Responsible Consumption: What Leads to Sustainable Behavior? Urban. Sustain. Soc. 2025, 2, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosta, M.; Zabkar, V. Antecedents of Environmentally and Socially Responsible Sustainable Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Olya, H. The Combined Use of Symmetric and Asymmetric Approaches: Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling and Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1571–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Roldán, G.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.; García-Umaña, A.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Medina-Miranda, S.; Marchena-Chanduvi, R.; Llamo-Burga, M.; López-Pastén, I.; Veas González, I. Digital Social Influence and Its Impact on the Attitude of Organic Product Consumers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beciu, S.; Arghiroiu, G.A.; Bobeică, M. From Origins to Trends: A Bibliometric Examination of Ethical Food Consumption. Foods 2024, 13, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Liu, H.-B.; Chen, T. Trends in Organic and Green Food Consumption in China: Opportunities and Challenges for Regional Australian Exporters. J. Econ. Soc. Policy 2015, 17, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Md Nor, K.; Ma, X.; Khatib, S.F.A. Trends and Future Directions of Consumers’ Intention to Buy Ethical Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2534528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Opportunities for Green Marketing: Young Consumers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2008, 26, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokaya, A.; Pandey, A. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer Buying Behavior of Organic Products in Surkhet Valley, Nepal. Int. Res. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 9, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhan, M.; Shafiei Sabet, F.; Borumandnia, N. Factors Affecting Purchase Intention of Organic Food Products: Evidence from a Developing Nation Context. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 3469–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, I.D.; Dabija, D.-C. Developing the Romanian Organic Market: A Producer’s Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Statistics South Africa Statistical Release P0302: 2024 Midyear Population Estimates; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2024.

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G.; Martínez Quiroz, A.K. The Influence of Price and Availability on University Millennials’ Organic Food Product Purchase Intention. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Vallejo, C.A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.G.; Ortiz-Regalado, O. The Influence of Skepticism on the University Millennials’ Organic Food Product Purchase Intention. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 3800–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Limbu, Y.B.; Pham, L.; Zúñiga, M.Á. The Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth on Green Cosmetics Purchase Intention: Evidence from Young Vietnamese Female Consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 2024, 41, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fan, L.; Xu, Y. An Investigation of Determinants of Green Consumption Behavior: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, E.S.; Ameyibor, L.E.K.; Mokgethi, K.; Kabeya Saini, Y. Healthy Lifestyle and Behavioural Intentions: The Role of Self-Identity, Self-Efficacy, Subjective Norms, and Attitudes. Int. J. Spa Wellness 2024, 7, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharani, K.A.J.; Purwanto, S. The Influence of Green Marketing, Brand Awareness, And Lifestyle on the Purchase Decision of Aqua Life Bottled Water Products in Surabaya. East Asian J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 3, 4887–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataracı, P.; Kurtuluş, S. Sustainable Marketing: The Effects of Environmental Consciousness, Lifestyle and Involvement Degree on Environmentally Friendly Purchasing Behavior. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2020, 30, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ Purchase Behaviour and Green Marketing: A Synthesis, Review and Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhang, M. Assessing Customers’ Perceived Value of the Anti-Haze Cosmetics under Haze Pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, S.; Panagiotarou, A.; Rigou, M. Impact of Environmental Concern, Emotional Appeals, and Attitude toward the Advertisement on the Intention to Buy Green Products: The Case of Younger Consumer Audiences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Impact of Green Advertisement and Environmental Knowledge on Intention of Consumers to Buy Green Products. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A. Understanding Customer Expectations of Service. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991, 32, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.N.; Ogiemwonyi, O.; Hago, I.E.; Azizan, N.A.; Hashim, F.; Hossain, M.S. Understanding Consumer Environmental Ethics and the Willingness to Use Green Products. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440221149727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouse, S.M.; Shekhar, R.; Ali Sulaiman, M.A.B.; Azam, A. Green Purchase Behaviour of Arab Millennials towards Eco-Friendly Products: The Moderating Role of Eco-Labelling. Bottom Line 2024, 38, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Naz, F.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Transforming Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Green Products: Role of Social Media. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Hung, C.-W. Elucidating the Factors Influencing the Acceptance of Green Products: An Extension of Theory of Planned Behavior. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 112, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymanpor, M.; Ajirloo, R.N. Examining the Mediating Role of Subjective Norms in the Relationship between Green Marketing Tools and Green Purchase Intention in Order to Preserve the Natural Environment. J. Environ. Sci. Stud. 2025, 10, 9839–9852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Noida, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Konuk, H.; Aydın Küçük, B.; Tınaztepe Çağlar, C. The Association of Employees’ Perception of the Manager’s Ambiguous Behaviors with Likelihood of Conflict Occurrence: A Cross-Cultural Study. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2024, 17, 255–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to Purchase Organic Food among Young Consumers: Evidences from a Developing Nation. Appetite 2016, 96, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; McDonald, R.; Louis, W.R. Theory of Planned Behaviour, Identity and Intentions to Engage in Environmental Activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of Green Purchase Behavior: An Examination of Collectivism, Environmental Concern, and PCE. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, M.M. A Hierarchical Analysis of the Green Consciousness of the Egyptian Consumer. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 445–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in Second Language and Education Research: Guidelines Using an Applied Example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781003117452. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees, C.M.; Brady, M.K.; Calantone, R.; Ramirez, E. Discriminant Validity Testing in Marketing: An Analysis, Causes for Concern, and Proposed Remedies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting Reliability, Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Structural Equation Modeling: A Review and Best-Practice Recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2024, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780203805534. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyanarayana, S.; Mohanasundaram, T. Fit Indices in Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Reporting Guidelines. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2024, 24, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrés-Sánchez, J.; Puchades, L.G.-V. Combining FsQCA and PLS-SEM to Assess Policyholders’ Attitude towards Life Settlements. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2023, 29, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Bao, Y. A Mixed-Method Approach to Assess Users’ Intention to Use Mobile Health (MHealth) Using PLS-SEM and FsQCA. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 74, 589–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780226702759. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781107013520. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss, P.C. Building Better Causal Theories: A Fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Zhang, C. Social Platform Content Marketing Strategies for Sustainable Sales Growth of Local Specialty Green Agricultural Products. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1609196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, T.; Pacchera, F.; Cagnetti, C.; Silvestri, C. Do Sustainable Consumers Have Sustainable Behaviors? An Empirical Study to Understand the Purchase of Food Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.