Abstract

The utilization of recycled materials in experimental product design has gained increasing importance in recent years due to heightened environmental concerns and the pursuit of sustainable development. Recycled products are not only made by recycling materials but also by taking discarded or abandoned waste treated by simple physical processes and reusing them to create new products. Many independent designers and small-scale labs focus on designing recycled products from such discarded materials. As recycled products increasingly enter intimate and high-frequency touch contexts, psychological factors such as hygiene concerns, perceived risks, disgust, and trust change, especially in the absence of regulation and compliance pressures. This scoping review synthesizes data from 12 articles using evidence matrices and heatmaps to reveal directional effects and proof density. The scoping review aims to (1) analyze the acceptance outcomes associated with varying degrees of use distance; (2) map the distribution of existing experimental evidence across recycled materials to identify remaining quality gaps; and (3) propose evidence-based recommendations to enhance the future use acceptance of experimental recycled products. Findings highlight significant research gaps and emphasize the importance of considering use distance and psychological barriers in the design and promotion of experimental sustainable products. These insights are intended to support scholars and designers in advancing sustainable product innovation.

1. Introduction

Statistics indicate that only a minority of all materials used globally come from recycled sources, and consumer waste contributes a relatively small proportion to recycled materials, emphasizing opportunities for expanding recycled material utilization across different sectors [1]. In product design, recycled materials serve not only to reduce waste but also to drive innovation by inspiring people to rethink habits, routines, or choices, thereby fostering sustainable production–consumption cycles [2]. This paradigm shift is critical to achieving environmental sustainability goals and developing experimental products that balance ecological responsibility with user acceptance and market viability.

With the global Sustainable Development Goals emphasizing responsible consumption and production, products made from recycled materials have become an important part of sustainable product design [3]. More independent designers and small laboratories are carrying out innovative work that explores the reutilization of discarded material as a sustainable life style [4]. The “Palavras para Movimentar e Sentar” exhibition from artist and designer Wesley Sacardi (Lisbon, Portugal) in 2025 [5] increased visitors’ emotional experience through perception. Walker (2016) constantly advocates for the role of experimental and exploratory making as design research, generating new knowledge in tangible forms [6]. However, consumers have different psychological thresholds for experimental products made from recycled materials in different contexts of use. Product use distance is categorized by different product attributes: close to the skin or not close to skin. Here, experimental products made from recycled materials are defined as recycled products using discarded or abandoned waste from independent designers and small-scale labs with low mass production through simple physical processes. But studies applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and related models indicate that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are influenced by context factors, including use distance or product intimacy, of products from the same origin of waste material at different use distances, which affect use acceptance and satisfaction [7]. For example, cleaning soap made from waste oil may be hard to accept, but bike chain lubricant made from waste oil is easy to accept, creating different emotional factors.

While consumers may readily accept waste-derived products like door handles using discarded festival ribbons from designer Sandra Neto Mess (Portugal) (see Figure 1) and benches using abandoned wood from Wesley Sacardi (Lisbon, Portugal), they often resist those intended for intimate use due to cognitive biases that are preconceived knowledge and understanding of products made from recycled material, health concerns, and limited material transmission, such as eco soap made from kitchen frying oil from Joosoap Lab (Helsinki, Finland) [8]. There is often a lack of confidence surrounding the bad mental imagery of products made from recycled materials as the origin of material, resulting in psychological barriers that hinder the acceptance and popularity of experimental sustainable products. Designers seeking to address concerns of sustainability therefore need to consider behavior and use, sometimes more so than production [9]. The desire to create sustainable products is meaningless if users do not recognize and use the potential of products to support sustainable behavior [9]. Additionally, consumers are not individual sovereigns in a free market, people are largely unable to make prudent choices about what to consume and what not to consume [10] and are extremely easily influenced by trends and role models. However, the role of role models is changing and heavily influenced by marketing and advertising, and convenient conditions (product availability and ease of use) will also change due to different use distances, affecting the occurrence of usage behavior [11].

Figure 1.

Door handle using discarded festival ribbons. Hualan Gou (Photographer). Movimentos Infinity, Casa do Jardim da Estrela, Portugal, 10 May 2025.

Polyportis et al., in 2022 [12], studied 46 articles and have demonstrated that factors such as environmental benefits, perceived quality, safety, risks, emotions, and individual differences influence consumer acceptance of products made from recycled materials. Even though perceived quality is a key consideration for recycled products, perceived product contamination and disgust are only important for products that are used next to skin [13]. Materials discarded after use by consumers, like used plastic bottles or paper collected from households or businesses, are often more mixed and contaminated [14]. When consumers know the source of the waste, it is easy for them to have negative mental imagery through perception, especially related to the use distance between the body and products. This highlights the ongoing challenge: while innovations in recycled materials and products are accelerating, consumer engagement with these sustainable choices progresses more slowly. Consumers are more likely to use products made from recycled plastic bottles when they are not touching the skin (e.g., handbags) compared to those that are in contact with skin (e.g., T-shirts), revealing an important boundary condition [13]. Experimental products from independent designers or small-scale labs lack background support and role models’ influence from big companies and big brands [10,15]. The trust crisis caused by greenwashing [9,16] has led to questions about the standardization and information integrity of these products. Current research has not focused on experimental products beyond clothes in fashion to discuss use acceptance from consumers at different use distances and the potential influence factors.

Given the novelty and complexity of these interactions, this review focuses on experimental recycled products across varying use distances to address critical gaps in understanding use acceptance patterns. The scoping review is guided by the primary research question: How do different use distances and material origins interact to influence use acceptance of experimental recycled products? To address this, three sub-questions are defined: (1) What acceptance outcomes are linked to different degrees of use distance? (2) How is the existing experimental evidence distributed across use distance and recycled material, and where do quality gaps remain? (3) What evidence-based recommendations can enhance future use acceptance of experimental recycled products? The scoping review offers a new perspective, supposing that use acceptance is impacted by use distance related to product intimacy, highlighting the balance between sustainable production and consumption. The findings not only deepen academic understanding but also provide theoretical and practical insights for advancing sustainable development of this type of product.

2. Conceptual Framework

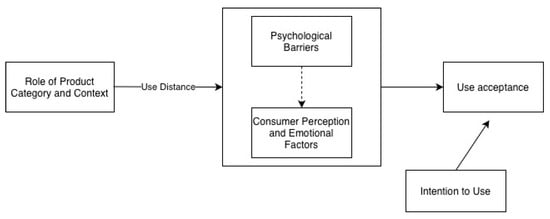

In the scoping review, we adopt the core constructs of the TAM and IBM as a light categorization framework (see Figure 2) to organize our analysis. Specifically, we utilize these established theoretical dimensions to guide our exploration of acceptance patterns. This approach allows us to cluster diverse findings, ranging from functional utility to social norms, into coherent themes, helping us identify how specific factors shift in importance regarding the “use distance” of recycled products changes.

Figure 2.

Light Categorization Framework.

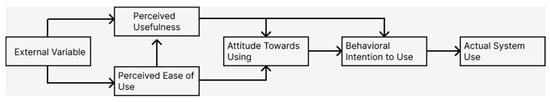

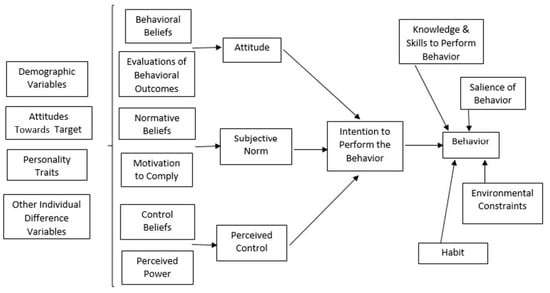

In this framework, we treat “use acceptance” as a parent concept, with attitude, intention to use, purchase intention, adoption, willingness to pay, and actual use serving as explicit indicators. Integrating the TAM (see Figure 3) and IBM (see Figure 4) enables a holistic classification of these factors: we utilize the TAM to identify primarily cognitive dimensions (e.g., perceived usefulness), while the IBM provides the lens for categorizing social–emotional dimensions (e.g., social norms and perceived behavioral control). This dual-lens approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the drivers behind recycled material product acceptance without restricting the analysis to strict causal pathways.

Figure 3.

Technology Acceptance Model adapted from Davis et al. (1989) [17].

Figure 4.

Integrated Behavior Model (IBM) reproduced from Cao et al. (2023) [18].

In the process of study selection, we developed keywords around core concepts, which are recycled materials, use distance, experimental products, and use acceptance. Recycled material here is related to discarded or abandoned material, broadly including recycled material, discarded material, and upcycled material. We consider “use acceptance” a broad concept measured through observable indicators such as attitude, intention to use or purchase, likelihood of choice, willingness to pay, and actual use. To address interdisciplinary terminology differences, we created a mapping of relevant core concepts: use acceptance, consumer acceptance, adoption, and intention. “Use distance” is defined as the spatial or contact intensity between a product and the body, and we created a mapping of related core concepts: product intimacy, proxemics, use distance, physical distance, and contact. “Experimental products” is a term that appropriately relaxes restrictions and broadens keywords to include experimental products, innovative products, and product design.

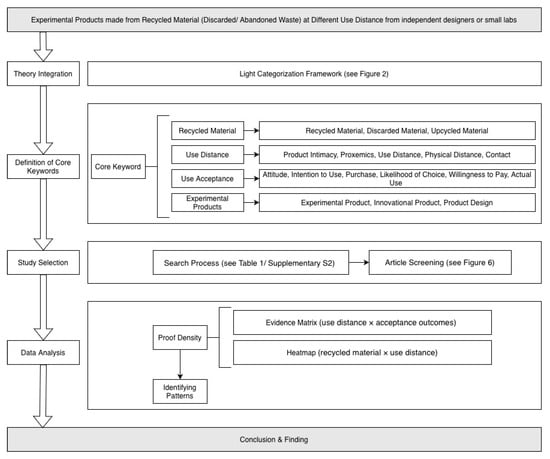

3. Methodology

3.1. A Scoping Review

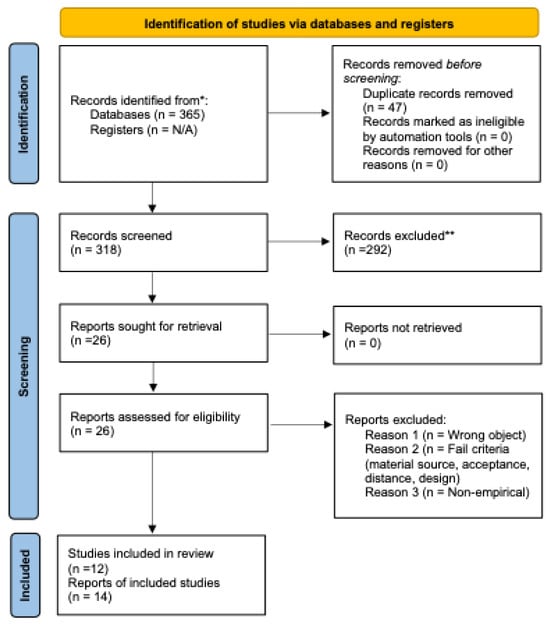

The present review is based on the scoping review approach, an increasingly adopted methodology for summarizing and reporting research evidence [19,20]. This scoping review was conducted without prior registration of a formal protocol in any public database. A scoping review is usually applied to summarize the streams of literature on a general research topic and highlight key trends and research gaps for future research [20]. The review process (see Figure 5) includes three steps: (1) inclusion criteria focus on empirical studies containing any of the mapped core constructs related to recycled materials, use distance, experimental products, and use acceptance; (2) synthesis uses evidence matrices (use distance × acceptance outcomes) and heatmaps (recycled material × use distance) to show directional effects and evidence density, highlighting research gaps; (3) patterns focusing on what the studies are related to are defined and the conceptual framework is deepened, developing a future agenda.

Figure 5.

Review Process.

3.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews and is reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The completed PRISMA-ScR checklist is provided as Supplementary File S1. To our knowledge, no other scoping review has examined use acceptance of experimental products made from recycled (discarded) materials at different use distances. However, we found a related review on consumer acceptance of products made from recycled materials [12], which did not discuss the use of distance grading. However, a separate manual search for use distance grading revealed that it was explicitly mentioned in the clothing category, where consumers’ attitudes differed regarding clothing made from recycled plastic bottles when it is not touching the skin (e.g., carrying bags) compared to those that are in contact with skin (e.g., T-shirts) [13]. Six additional articles were identified through manual snowballing search based on the reference lists and citations of these two core papers. Articles were selected for the scoping review by searching the major academic databases Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus for relevant publication from 2020 to 2025. We screened titles, abstracts, and keywords using a predefined selection process and Boolean operators (AND, OR, and AND NOT). We established keywords to track publications based on four dimensions: material source, product category, acceptance index, and distance.

3.3. Study Selection

During the study selection process, we applied specific inclusion and exclusion criteria based on title, keywords, and abstract (TKA). These criteria are explained in detail in the following paragraph. The final selection process included articles that explored the use acceptance of experimental products using recycled materials at different use distances. The scoping review considered both theoretical and empirical research articles in English from the period identified. However, only empirical studies are included in the final evidence synthesis.

We included studies that examined consumer-facing products made from waste-derived materials, including recycled, discarded, or upcycled materials. To be eligible, a study needed to report at least one outcome related to acceptance, such as attitudes, intention to use or purchase, likelihood of choosing the product, willingness to pay, or actual use or choice behavior. The study also had to provide enough information to determine how close the product is to the body during use (use distance or product intimacy), either stated directly or clear from the product type and context. For the synthesis, the scoping review includes empirical research using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods, such as experiments, surveys, interviews, choice tasks, or ethnographic studies that report acceptance-related evidence. The core search window covers 2020 to 2025 and includes 223 articles from Web of Science and 134 articles from Scopus and 8 additional studies identified by citation, reference, and related work chasing, including 2 core articles. The total is 318 articles after deduplication by Zotero (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

PRISMA flow diagram. * “Records identified from databases and registers” means all references we found from bibliographic databases and study/clinical trial registers. ** indicate how many records were excluded. “N/A” means “not applicable” or “none”.

The scoping review excludes papers that focus solely on engineering or materials science without any use acceptance or acceptance data from consumers, as well as studies on civil or infrastructure applications (for example, concrete, asphalt, aggregates, fly ash, roads, wastewater, or sludge). The selected document types without empirical acceptance data are not included in the synthesis, and medicine, engineering, chemistry, and biomedical implants are excluded unless acceptance outcomes clearly relate to the type of product.

Studies that examined only non-recycled or purely virgin and bio-based materials were excluded, unless recycling-specific results were reported separately. We also excluded studies where the use distance could not be determined and could not reasonably be inferred from the product described, as well as studies written in languages outside our declared scope. Due to the exceptionally low number of results yielded by the first screening (5 from WoS and 3 from Scopus after searching with keyword queries only) on 30 December 2025, we broadened our search string and performed the second search (see Table 1) on 30 December 2025. Twenty-six articles are selected after the first decision based on the above exclusion criteria by the authors. They were manually checked, after which 14 were excluded due to the papers being non-empirical and not fitting the inclusion criteria by the second decision (see Supplementary File S2). Finally, twelve articles are selected of which one included report comprised three empirical essays from “Four Essays on Consumption Behavior in the Circular Economy,” which were treated as three separate studies in the synthesis (see Figure 6 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Identifying process. The asterisk (*) is a truncation symbol/wildcard that indicates “any ending”. In WoS and Scopus, * can represent zero or more characters to include different forms of the same stem at once. Bold words are title.

Table 2.

Information about the included publications.

3.4. Charting the Data

We analyzed literature trends from 2020 to 2025 based on the number of articles published annually. To further extract data, we created a data extraction grid, which includes general information about publications (title, journal name, and year of publication) and information on the research perspectives involved (see Table 2) based on the selected 12 articles (see Figure 6). Then we constructed and reported the review findings using an evidence matrix (use distance × use acceptance outcomes) and a heatmap (recycled material × use distance), visually displaying directional effects and evidence density based on the available information, providing an informed basis for future research.

4. Evidence Synthesis and Reporting

4.1. Literature Trend

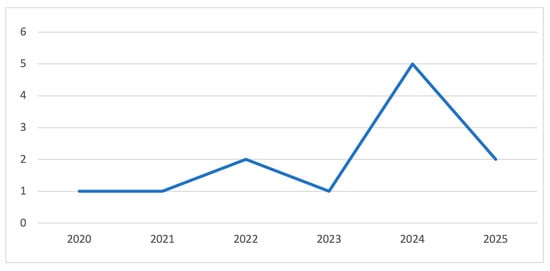

According to data collected from 2020 to 2025 (see Figure 7), research on recycled materials is not new and has particularly increased since 2024. Current literature predominantly investigates generic recycled plastics and mass-produced goods, neglecting the unique implications of using raw discarded or abandoned materials directly in product design. This limitation extends to the variable of “use distance.” Although physical proximity is discussed in fashion studies (via skin contact), these inquiries typically rely on processed recycled plastics, thereby overlooking the sensory and psychological impact of raw abandoned materials near the body in design. Many references mentioned perception through sensory interaction with materials, which is different from use distance that indicates physical proximity (see Table 2). We present the results of our evaluation using an “evidence mapping” methodology. The implicit definition of an evidence map (as defined by most studies reporting its components) is a systematic search of a broad field [32] that visually identifies knowledge gaps and/or future developments.

Figure 7.

Trend in the number of articles per year from 2020 until December 2025.

Figure 8 is an evidence map (use distance × acceptance outcomes) that presents the strength of the evidence using specific article serial numbers. In this map, “low” indicates weak or ambiguous evidence, “middle” indicates general evidence, and “high” indicates strong evidence. The figure shows that the existing literature is rarely fully aligned with the core concept. Use acceptance outcomes are related to acceptance at different use distances, including attitudes, intention to use, likelihood of choosing the product, willingness to use, and actual use. Use distance mainly refers to the physical distance between people and products and is linked to product intimacy and proxemics.

Figure 8.

Evidence map (use distance × acceptance outcomes) based on 12 relevant articles. The plot depicts the serial numbers of articles (bubbles), the strength of acceptance outcomes (y-axis), and the strength of use distance (x-axis).

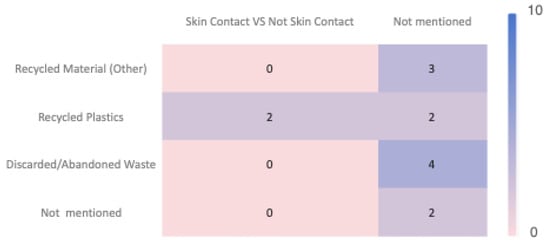

Figure 9 is a heatmap that shows intensity by the number of articles, across two dimensions: recycled material type and use distance for product attributes. The x-axis represents use distance categories, skin contact vs. not skin contact, and includes a “not mentioned” category because many articles do not explicitly address this dimension, ranging from low (blue) to high (red). The main arguments and research subjects across all reviewed texts were categorized and statistically analyzed to generate these scores. Combining Figure 8 and Figure 9 visually presents the relationship between use distance, material type, and acceptance outcomes, thus providing a reference for design and research direction.

Figure 9.

Heatmap (recycled material × use distance) showing the intensity of evidence through the number of articles. The two categories of use distance (x-axis), the four types of recycled material (y-axis).

4.2. Identifying Patterns

These patterns were identified by synthesizing the chosen articles with TAM and IBM constructs to explain resistance toward waste-derived products. As illustrated in the framework (see Figure 2), the process begins with product category and context, which interacts with the user through use distance (physical or sensory proximity). This proximity determines the intensity of psychological barriers (like disgust), which directly influence consumer perception and emotional factors (such as trust). The diagram shows that these internal factors do not operate in isolation; rather, barriers actively shape perceptions, ultimately determining the user’s intention to use and final use acceptance.

Use Distance: Physical or sensory proximity between products and the user based on products’ attributes (e.g., skin contact vs. distant use) significantly influences consumer acceptance. Use distance as a moderator that shapes how product attributes influence key constructs in both the TAM and IBM. When use distance is high, as with intimate or skin-contact products (e.g., T-shirts), information about a waste-based origin (such as being made from recycled bottles) more strongly activates contamination schemas and disgust responses. This affective barrier directly reduces perceived usefulness in the TAM, as consumers may doubt the safety and cleanliness of such products for their skin. At the same time, high-intimacy products demand greater trust in production quality because users feel they have less personal control over hygiene, which lowers perceived behavioral control in the IBM and heightens perceived risk. In contrast, low use distance products (e.g., bags, furniture) do not provoke such strong contamination concerns, and users feel they can manage hygiene through external cleaning, resulting in higher perceived control and weaker negative effects on usefulness and risk perceptions. Empirical evidence supports this mechanism by showing that contamination and disgust effects are proximity-dependent in clothing design, with contact source becoming especially salient when products touch the skin [13]. However, no specific research was conducted on sustainable recycled products made from discarded waste and more evidence is needed to prove the relationship between consumers’ acceptance of product use and “product intimacy.”

Psychological Barriers: Negative mental imagery related to the origin of recycled materials (e.g., waste, discarded sources) induces psychological barriers such as disgust, perceived contamination, and mistrust, especially for products that contact the skin. This “bad origin” effect leads to lower acceptance rates for intimate contact recycled products even if they meet functional standards. Different degrees of use distance may also affect users’ psychology.

Psychological barriers function as negative mediators between stimuli and acceptance outcomes. The IBM posits that those behavioral beliefs (expectations about outcomes) shape attitude. For recycled products, belief that “recycled = contaminated” → negative outcome expectation → negative attitude. Even if a recycled shirt is functionally identical to new fabric, disgust creates a “bad origin” effect, which overrides perceived usefulness assessments in the TAM. Users cannot cognitively separate performance from affective response. Research shows that contamination perceptions are not rational, they persist even with no actual quality difference.

Consumer Perception and Emotional Factors: Environmental benefits, perceived quality, health safety, sustainability value, and trust are pivotal in shaping acceptance across all use distances but act more strongly for high-intimacy products (skin contact). Emotional responses and consumer values (e.g., sustainability awareness and design aesthetics) modulate user attitudes toward recycled products. Emotional factors create alternative pathways to use intention that can compensate for weak perceived usefulness caused by barriers. They shift the cost–benefit calculation in the user’s internal attitude formation (IBM). Moreover, psychological barriers (such as contamination beliefs) act as “lenses/filters” that distort consumers’ specific perceptions of a product.

Role of Product Category and Context: Acceptance patterns vary by product category, with utilitarian products (e.g., household items) facing less psychological resistance than intimate products (e.g., wearables). The context of use and sensory experience also influence acceptance and are impacted by the variable of use distance. The same source of material but uses at different use distances result in different psychological barriers, consumer perceptions, and emotional factors.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The reviewed studies show research gaps in use acceptance related to experimental recycled products made from discarded or abandoned materials at various use distances. At present, in sustainable product design, there is no clear discussion of user acceptance based on the dimension of use distance depending on the role of product category and context. User acceptance and use acceptance are two different concepts. User acceptance focuses on whether users might appreciate a product’s creativity, design philosophy, or social value, demonstrating “tolerance” or “appreciation.” For example, a user seeing a radio made from a soda can might indicate acceptance but not necessarily acceptance of using it. Use acceptance is a kind of “use presupposition,” very close to Donald Norman’s perceptible affordances, which states that seeing an object evokes an understanding of how to use it, generating an impulse to interact, and contextual relevance [33]. And there is an even greater gap between the two in the dimension of use distance, which needs more nuanced models integrating psychological barriers due to the origin of material [22,24,28,29,31], consumer perception and emotional factors [21,30], and use intimacy [13], which are needed to better predict use acceptance. There are huge differences in the use acceptance of products with the same origin of recycled material with different degrees of product intimacy [13,31].

These 12 articles are mainly divided into two categories: one group shows resistance/complexity under high intimacy (skin contact), and the other group shows greater acceptance under low intimacy (visual/abstract). When waste material is physically too close, it feels invasive rather than helpful [28]. Furthermore, for clothing (close to skin), passive consumption leads to failure, and resistance must be overcome through active participation (such as repair/DIY) or uniqueness. This demonstrates that high intimacy requires completely different strategies from those for low intimacy [22,24,30]. However, many highly relevant papers focus on clothing to explore acceptance at different usage distances, lacking discussions on the use acceptance of experimental products made from discarded waste at different use distances.

Studies often apply behavior and acceptance theories [12] like the TAM and IBM, highlighting the perceived ease of use and usefulness of recycled products. To develop more specific experiments, analysis the different use acceptances of products made from recycled materials (discarded or abandoned waste) at different use distances should be carried out. The use distance classification might be combined with Hall’s proxemics [34] and product contact science to construct a use-distance-based hierarchical classification system depending on product category. Pino et al. noted that online retailers must compensate for the lack of physical touch by stimulating “imagined touch” [21]. Similarly, Tu et al. stressed the importance of all five senses in driving consumer emotion [29]. Thus, in the future context of contactless retail, how to use interface design, storytelling, and interaction to compensate for the lack of tactile feedback is a key research topic affecting the use acceptance of recycled material products and the effective communication of information. Experiments are needed to verify the real effects of different information strategies.

This scoping review helps designers and researchers understand the intersection of four dimensions: material source, product category, acceptance index, and distance. And it reveals a trade-off in recycled product design: as products become closer to the body, the focus of design intervention must shift from “visual storytelling” to “substantial sensory optimization” or “deep behavioral engagement.” Simply transplanting “green explicitness strategies” applicable to low-intimacy products (such as packaging) to high-intimacy products (such as clothing) not only fails to increase acceptance but may also lead to a collapse in “use acceptance” by triggering consumers’ “pollution defense mechanisms.” However, existing research has not addressed this issue for general products other than clothing. We propose the hypothesis that use acceptance towards experimental products using recycled materials (discarded waste) depends on the physical distance between the product and the user (the closer the use distance, the lower the acceptance) for future research, especially for independent designers or small labs without the halo of professionalism of big brands. It highlights the crucial need for design strategies targeted at use distance to improve use presets of sustainable recycled products in the context of use distance. And it proposes directions for thinking about how to conduct information interaction with products and people when conducting contactless retail in the context of the digital world.

Limitations of the Review Methodology

While this review provides a novel mapping of the intersection between material source and use distance, several methodological limitations must be acknowledged. First, regarding the review process, screening and data extraction were primarily conducted by a single reviewer. Although a standardized data extraction form was rigorously applied to minimize inconsistency, the absence of double-blind screening may introduce potential selection bias. Second, consistent with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines for scoping reviews, a formal quality assessment (QA) of the included studies was not performed. The objective of this review was to map the scope of existing literature across four specific dimensions: material source, product category, acceptance index, and distance. Consequently, the included studies vary significantly in rigor. This implies that the findings represent a descriptive overview of design strategies and the current landscape of these intersections, rather than statistically generalized truths.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18031288/s1, Supplementary File S1. PRISMA-ScR Checklist [35]; Supplementary File S2. Master screening table.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G., C.B. and P.D.; methodology, H.G. and C.B.; formal analysis, H.G.; investigation, H.G.; resources, C.B. and P.D.; data curation, H.G.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G.; writing—review and editing, C.B. and P.D.; visualization, H.G.; supervision, C.B. and P.D.; project administration, C.B.; funding acquisition, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financed by national funds through Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), I.P., under the Strategic Project with the reference UID/04008: Centro de Investigação em Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be made directly to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBM | Integrated Behavior Model |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

References

- Circle Economy. The Circularity Gap Report 2025; Circle Economy: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, E.; Veelaert, L.; Ragaert, K. Design from Recycling: A Material-Driven Design Method. In Springer Handbooks; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume Part F590, pp. 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Consumption and Production. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Foster, H. Design and Crime: And Other Diatribes; Verso eBooks. 2003. Available online: https://e-artexte.ca/id/eprint/17207/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Sacardi, W. Palavas para Movimentar e Sentar [Exhibition]; Galeria do Palácio Gama Lobo: Loulé, Portugal, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S. Design for Meaningful Innovation. In The Routledge Companion to Design Studies; Sparke, P., Fisher, F., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 395–408. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Kim, C.; Kang, R. Positive User Experience over Product Usage Life Cycle and the Influence of Demographic Factors. Int. J. Des. 2020, 14, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- JooSoap Studio. Eco Soap Made from Frying Oil. Available online: https://www.joosoap.org/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Micklethwaite, P. Design Against Consumerism. In A Companion to Contemporary Design Since 1945; Massey, A., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2019; pp. 436–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behaviour and Behavioural Change; Report to the Sustainable Development Research Network; Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey: Guildford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, A. Design’s Role in Sustainable Consumption. Des. Issues 2010, 26, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyportis, A.; Mugge, R.; Magnier, L. Consumer Acceptance of Products Made from Recycled Materials: A Scoping Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.D.; Leary, R.B. It Might Be Ethical, but I Won’t Buy It: Perceived Contamination of, and Disgust towards, Clothing Made from Recycled Plastic Bottles. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C.A.; de Oliveira, M.A.; Jacinto, C.; Mondelli, G. Challenges to Reducing Post-Consumer Plastic Rejects from the MSW Selective Collection at Two MRFs in São Paulo City, Brazil. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2022, 24, 1140–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürn, M.K.; Kronmüller, A.; Layrisse Villamizar, F. Branding in the Circular Economy; Nuremberg Institute for Market Decisions (NIM): Nuremberg, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.nim.org/en/publications/detail/branding-in-the-circular-economy (accessed on 9 January 2026).

- Futerra. The Greenwash Guide; Futerra Sustainability Communications: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M. Self-Identity Matters: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Decode Tourists’ Waste Sorting Intentions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Drey, N.; Gould, D. What Are Scoping Studies? A Review of the Nursing Literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1386–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daudt, H.M.; Van Mossel, C.; Scott, S.J. Enhancing the Scoping Study Methodology: A Large, Inter-Professional Team’s Experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s Framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, G.; Amatulli, C.; Nataraajan, R.; De Angelis, M.; Peluso, A.M.; Guido, G. Product Touch in the Real and Digital World: How Do Consumers React? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, H.; Fahy, F. Sew What for Sustainability? Exploring Intergenerational Attitudes and Practices to Clothing Repair in Ireland. IrishGeog 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuojua, S.; Pahl, S.; Thompson, R. Ocean connectedness and consumer responses to single-use packaging. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, D. Recrafting Futures: Post-Material Transformations Toward Clothing Longevity; Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero-Regis, T.; Lindquist, M.; Van Lunn, C.; Hopper, C. Mapping Fashion Networks and Pre-Consumer Textile Flows for Circular Communities. Int. J. Sustain. Fash. Text. 2024, 3, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Passaro, R.; Ulgiati, S. Evaluating Good Practices of Ecological Accounting and Auditing in a Sample of Circular Start-ups. In Place Based Approaches to Sustainability: Volume II; Palgrave Studies in Sustainable Business in Association with Future Earth; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyportis, A.; Mugge, R.; Magnier, L. To See or Not to See: The Effect of Observability of the Recycled Content on Consumer Adoption of Products Made from Recycled Materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T. Four Essays on Consumption Behavior in the Circular Economy. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, J.-C.; Yang, C.-H.; Lin, S.-H.; Creativani, K. Exploring Consumer Perception and Acceptance of Recycled Merchandise under Five-Sense Design. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 6393–6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H. Green or Unique? How Design Typicality and Material Domain Distance Influence Purchase Intentions for Upcycled Clothing. Ph.D. Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R.; Dvorsky, J.; Tewari, A.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Kumar, M.; Singh, M.; Sharif, T. Do Gen Y and Gen Z Differ in Their Purchase Intention towards Recycled Products? A Moderation Study. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2534852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miake-Lye, I.M.; Hempel, S.; Shanman, R.; Shekelle, P.G. What Is an Evidence Map? A Systematic Review of Published Evidence Maps and Their Definitions, Methods, and Products. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, D.A. The Design of Everyday Things, Revised and Expanded ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T.; Birdwhistell, R.L.; Bock, B.; Bohannan, P.; Diebold, A.R.; Durbin, M.; Edmonson, M.S.; Fischer, J.L.; Hymes, D.; Kimball, S.T.; et al. Proxemics [and Comments and Replies]. Curr. Anthropol. 1968, 9, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.