Abstract

Agrivoltaic systems, which integrate solar energy generation with agricultural production, offer a promising solution to optimize land use efficiency. This work presents a case study for the assessment of an agrivoltaic pilot project in a small-scale solar farm operated by SOLENIUM in San Diego (Cesar, Colombia), located in the Colombian tropical dry forest. The project evaluated environmental conditions, selected melon and watermelon as shade-tolerant crops, and assessed technical challenges, including mechanization constraints. Preliminary results indicated that agrivoltaic systems can maintain agricultural productivity while generating renewable energy, with photosynthetically active radiation measurements averaging 1342 μmol/m2/s in cultivation areas. This case study demonstrates the viability of agrivoltaic systems as a scalable model for sustainable rural development in the Colombian tropical dry forest.

1. Introduction

The depletion of fossil fuel resources and the detrimental environmental impacts associated with their combustion are strong reasons to push humanity towards a global transition by promoting the use of clean energy sources to mitigate the climate emergency [1,2]. This transition has been further accelerated by advances in photovoltaic technology and significant cost reductions in solar installations, with the median levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) from utility-scale solar photovoltaics declining by 85% between 2010 and 2019 (excluding the 30% investment tax credit), reaching approximately 40 USD/MWh [3,4].

The increasing deployment of solar photovoltaic installations has created concerns about competition for land use between energy production and agricultural activities [5]. This challenge is particularly acute in developing countries where food security and energy access are both critical priorities. According to the World Bank collection of development indicators, the global agricultural sector currently occupies approximately 12% of available land for crop production, while in Colombia, this figure reaches approximately 35% of the national territory, which can trigger competition over land usage [6]. Agrivoltaic systems, defined as the co-location of solar photovoltaic panels and agricultural production on the same land area, have emerged as a promising solution to address this land-use competition while providing multiple benefits [7,8].

Recent research has demonstrated that optimized agrivoltaic configurations can achieve land equivalent ratios (LERs) above 1.2, indicating more efficient land use than separate agricultural and energy production systems [9]. Studies have shown variable crop responses to partial shading, with some crops experiencing yield increases under optimal shading conditions, particularly in high-irradiance environments [10,11]. The economic viability of agrivoltaic systems has been demonstrated through lifecycle analyses, showing favorable LCOE compared to diesel alternatives and potential for income diversification [12,13].

In Colombia, the renewable energy sector has experienced significant growth, with solar energy capacity increasing substantially in recent years. However, the implementation of agrivoltaic systems remains limited, despite the country’s favorable solar irradiance conditions and significant agricultural sector [14,15]. The Colombian Caribbean region has seen the implementation of several small-scale solar farms (SSSFs). Many of these SSSFs are located in the tropical dry forest, which opens the question of whether agrivoltaic systems could be deployed in such ecosystems [16,17,18].

This study’s main objective was to present a case study to assess an agrivoltaic system deployed in an SSSF. Our results provide positive evidence towards the development of agrivoltaic systems in SSSFs based on the following points: the study (i) characterized the environmental and technical conditions of SSSFs for agrivoltaics implementation; (ii) selected and evaluated crop species adapted to local conditions and moderate shading; and (iii) implemented a pilot agrivoltaic project with continuous monitoring. The research focused on a pilot of 50 melon plants that were successfully characterized and a follow-up watermelon plantation pilot study in 2.5 ha in an SSSF operated by Unergy & Solenium in San Diego (Cesar, Colombia). The overall results provided evidence for a replicable model that can be expanded to other SSSFs across Colombia’s rural regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

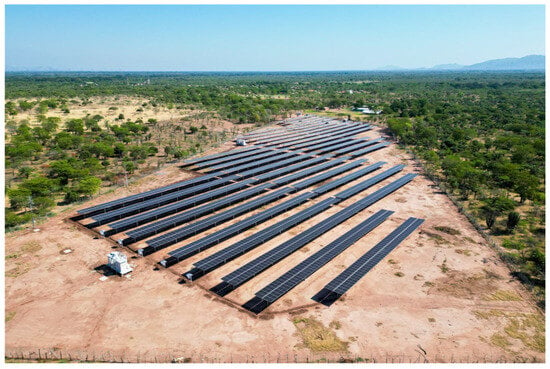

The Valle de Gandalf SSSF (see Figure 1), operated by the companies Unergy & Solenium, located in the municipality of San Diego-Cesar (10°20′05.2″ N 73°13′45.1″ W), was selected as a case study. The SSSF has an area of 2.5 ha for the establishment of an agricultural production system.

Figure 1.

Valle de Gandalf SSSF in San Diego (Cesar, Colombia). No crops planted, only an energetic solution.

2.2. Phase 1: Environmental Characterization

2.2.1. Climate Analysis

A climatological characterization was conducted using data from a meteorological station (climate station Aeropuerto Alfonzo Lopez, Valledupar, Cesar, 28025502) located a few kilometers away from the SSSF. Historical climatological averages (1991–2020) from the Colombian Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies (IDEAM, by its acronym in Spanish) were analyzed to determine monthly precipitation patterns (±15% error margin) and potential evapotranspiration. Temperature and relative humidity were measured in situ using portable thermometers located in the SSSF and were compared with the climate station data. It is important to highlight that the historical climatological data were chosen to avoid atypical years during crop selection.

The climatological data were combined into a Thornthwaite and Mather water balance model to identify seasonal water shortages and times of crop stress [19,20]. This information was crucial for determining irrigation needs and scheduling in agrivoltaic production systems [21].

2.2.2. Soil Analysis

Physicochemical soil analyses were performed by the Soil and Water Laboratory at Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano’s Center for Biosystems (Bogotá, Colombia). A total of 10 samples were collected from random locations in the SSSF at two depths, 0 cm–20 cm and 20 cm–40 cm. The samples were collected and prepared following the procedure by Gelvez et al. [22]. The tests measured texture, pH, electrical conductivity, organic matter, cation exchange capacity, and the contents of macro- and micronutrients.

2.2.3. Solar Infrastructure Characterization

Technical specifications of the solar installations were documented, including panel configuration, tracker system specifications, and inter-row spacing. This information was essential for determining agricultural implementation constraints and energy generation monitoring protocols.

2.2.4. Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) Distribution

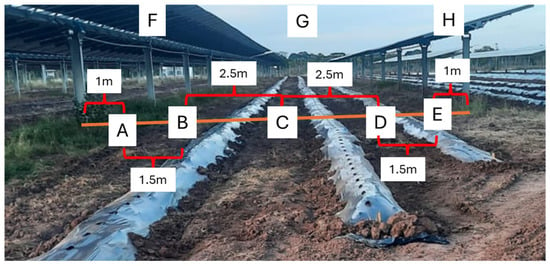

Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) was measured using an Advanced Quantum PAR meter (Quantico APM130, range: 0 μmol/m2/s–3999 μmol/m2/s) at five (5) strategic positions between panel rows at a height of 30 cm (see positions labeled as A, B, C, D, and E in Figure 2), as well as 3 (three) positions over the height (2.5 m) of the solar panels (see Figure 2; positions F, G, and H). Measurements were taken at three daily intervals: morning (08:00–09:00), midday (12:00–13:00), and afternoon (16:00–17:00) every 4 days for one month, to characterize temporal radiation distribution. Only data during sunny days was considered. The PAR sensor was placed at a 0° inclination for all the positions. The available cultivation area was determined based on PAR availability and panel movement trajectories.

Figure 2.

Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) sampling scheme. The PAR sensor was placed in positions labeled as A, B, C, D, and E at a height of 30 cm. For positions labeled as F, G, and H, the PAR sensor was placed at a height of 2.5 m.

2.3. Phase 2: Crop Selection

Crop selection was conducted based on the following conditions: (i) crops that could growth normally and have high yields under moderate shade conditions (15–40% PAR reduction); (ii) crops that could adapt to local climatic conditions in San Diego (Cesar, Colombia); (iii) crops with a history of traditional cultivation in the region; (iv) crops with commercial viability on local markets; (v) crops with a short production cycle, allowing multiple harvests per year and rapid cash turnover at small scale. The selection criteria prioritized species with demonstrated shade tolerance and established local market channels.

2.4. Phase 3: Pilot Implementation and Monitoring

Following crop selection, a pilot project was established in the Valle de Gandalf SSSF. Implementation included (i) a 50-plant melon pilot plot; (ii) a drip irrigation system installation connected to a deep well; (iii) soil mechanization using adapted machinery; and (iv) full-scale cultivation across 0.5 ha in the SSSF. The total cultivation area was determined based on the distance between crop plants and keeping a safe distance of 2 m away from the base of the solar trackers, which was set by the SSSF operator.

Crop nutrition was managed via fertigation using a commercial water-soluble compound fertilizer (SOLUTEC® 20-20-20, Cosmoagro S.A., Colombia), formulated for soil application through irrigation systems. The fertilizer supplied a balanced macronutrient composition (20% N, 20% P2O5, and 20% K2O) and included micronutrients, namely boron (0.02%) and copper (0.01%), with metallic micronutrients chelated with EDTA. Fertigation was conducted on three occasions: at 8, 30, and 50 days after transplanting, applying the fertilizer at a concentration of 0.5 g/L of irrigation water each time. This fertilization regime was designed to ensure adequate nutrient availability during early establishment and vegetative growth, thereby reducing the risk of soil nutrient limitations under agrivoltaics conditions.

No synthetic fungicides or insecticides were applied. The absence of chemical plant protection treatments was associated with the presence of seven managed honeybee hives within the experimental mini farm, which were installed to enhance crop pollination. To safeguard pollinators’ health and activity, a pollinator-friendly phytosanitary strategy was adopted. This low-input phytosanitary approach was applied consistently across all treatments and aligns with sustainability principles emphasizing pollinator conservation and minimal chemical inputs under alternative production systems.

2.5. Soil Mechanization

Soil mechanization was performed using a Ford 5000 tractor. Two passes were made using a disc plow with a width of 4 m and a working depth of 25 cm; subsequently, a pass was made using a 13-horsepower rotary tiller with a working depth of 10 cm.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard deviation were calculated for all data, and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed using STATGRAPHICS Centurion XVI (Statpoint Technologies, Inc., Warrenton, VA, USA). The statistical significance was established at a 5% significance level (p ≤ 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Characterization

3.1.1. Climate

The study site was located in a tropical dry forest zone characterized by mean annual temperatures between 24.0 °C and 34.7 °C (see Table 1). Average annual precipitation during 30 years of data was 1016.7 mm, concentrated primarily from May to October, with a pronounced dry season from December to March. Potential evapotranspiration reached 2662 mm, creating a water deficit during several months. The mean relative humidity was ~65.3%, but there could be peaks over 70%, creating conditions favorable for fungal disease development, which suggested the necessity of appropriate phytosanitary management protocols.

Table 1.

Climatic conditions in San Diego (Cesar, Colombia).

Crop health was monitored during the entire growing cycle through systematic visual assessments conducted at least weekly across all plots. Despite partial shading and relatively high humidity conditions under the agrivoltaic system, no foliar fungal disease outbreaks or pest infestations reached levels requiring phytosanitary intervention. Observed foliar symptoms were sporadic and incidental, consistent with background incidence typical of the region’s production systems and did not negatively impact crop development.

According to the climate station data, the average high and low temperatures during the melon crop period (conducted between April and June 2024) were 34.8 °C and 24.5 °C, respectively. Likewise, the average relative humidity and accumulated precipitation were 67.3% and 343 mm. Our field measurements yielded temperatures at the site between the averages of the climate station and a humidity of 68.5%.

3.1.2. Soil Properties

Soil analysis revealed a loam texture composition (41.5% sand, 33.8% silt, and 24.6% clay), providing balanced drainage and water retention, characteristics that were suitable for diverse crop cultivation [23]. Field organoleptic tests (from samples taken on shaded and unshaded areas in the SSF) indicated higher soil moisture levels in the shaded areas, which was expected as the soil sample was taken from areas under the solar panels. The soil had a pH of 7.4, indicating slight alkalinity. This condition could reduce the availability of phosphorus and manganese, which was confirmed in the laboratory analysis.

The soil analysis also revealed nitrogen deficiency, which was critical for vegetative development; hence, the soil required supplementation through nitrogenous fertilizer applications, as has been conducted for soils under similar environmental conditions [24]. Potassium and chloride levels were optimal, indicating good general fertility, as has been shown in other studies [25]. However, excesses of calcium, magnesium, and sulfur levels detected in the soil analysis could create nutrient absorption imbalances that require careful fertilization management and periodic monitoring [26].

3.1.3. Solar Infrastructure and Cultivation Space

The SSSF contained 2500 bifacial solar panels (610 W each) mounted on solar tracking systems at 2.4 m height, providing a total installed capacity of 1300 kW DC (direct current) and 900 kW AC (alternating current). The bifacial panels captured both direct and reflected radiation, making high soil albedo beneficial for energy production. Integration with agricultural systems requiring white plastic mulch (i.e., agromulch) could potentially enhance energy generation [27,28,29].

Tracker rows were separated by 10 m, with 60-degree tracking angles leaving a 6 m clear area between rows for cultivation while maintaining safety margins for panel movement. It is important to highlight that even small obstructions or shading on photovoltaic modules could cause non-linear energy losses; hence, shading risks must be minimized [30]. From an agronomic standpoint, the area directly under the module experienced high shade, as is shown later in the PAR measurements. This high shade was insufficient to support high-yield potential. Therefore, the planting area was considered only in the area between the rows of the solar panels and not the area within the photovoltaic project. This configuration guaranteed the entry of personnel and equipment. The present area configuration provided approximately 0.5 ha of cultivable area within the 2.5 ha of the SSSF.

3.1.4. Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR Distribution)

The results from PAR measurements during sunny days are displayed in Table 2. The PAR measurements revealed similar availability in the central areas between panel rows, experiencing minimal shade from tracker movement. Peak midday values exceeded 2000 μmol/m2/s, with daily averages of 1342 μmol/m2/s in the five positions under the solar panels, sufficient for adaptation of numerous crop species. ANOVA showed that during the morning and midday, there was a significant difference (p ≤ 0.0.5) between the PAR measurements above and below the panels (i.e., between positions ABCDE and FGH in Figure 2). Meanwhile, the same analysis conducted for the afternoon revealed that there is no difference (p > 0.05). These results could be expected as positions ABCDE (see Figure 2) were below the solar panels.

Table 2.

PAR radiation (μmol/m2/s) for the positions relative to solar trackers located as displayed in Figure 2.

3.2. Crop Selection

Based on the literature [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] and local environmental conditions, traditional regional crops with moderate shade tolerance were identified: melon (Cucumis melo), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), chili pepper (Capsicum annuum), bunching onion (Allium Fistulosum), and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata). Table 3 shows the criteria for crop selection, considering shade, suitability under climate conditions, historic tradition, trading availability, and short production cycle. Based on Table 3, the more suitable crops were melon, watermelon, and chili pepper.

Table 3.

Criteria for crop selection.

Chili pepper is commonly grown in Mediterranean-type horticulture. It is often cultivated under photo-selective or black shade nets that provide about 30% to 40% shade. These nets help to reduce excess radiation and sunburn. They also speed up uniform ripening. In most cultivars, these nets improve marketable yield and quality compared to open-field production with no cover [39]. In San Diego’s conditions, the first harvest could start 90 to 120 days after transplanting. Fruit picking then continues over many successive rounds, often between 24 and 40 harvests, for several more months. This delays full revenue recovery and complicates short-term cash flow for small farmers [40].

Watermelon and melon were prioritized based on farmer expertise and market trading availability. Catalayud et al. [41] have shown that optimal watermelon yield can be achieved under shade conditions at PAR levels as low as 800 μmol/m2/s [41]. Similarly, a 50% shade does not reduce melon fruit mass production compared to full sun cultivation [42]. Additionally, a short cycle (i.e., 60 days) at San Diego’s conditions and its creeping growth habit ensured zero interference with light capture by solar panels, allowing for better planting densities as well, and therefore a greater number of plants per area. International agrivoltaic trials with these crops have demonstrated minimal to negligible yield reductions at low PAR values [43]. Therefore, the crops selected for the pilot implementation were melon and watermelon.

3.3. Pilot Implementation

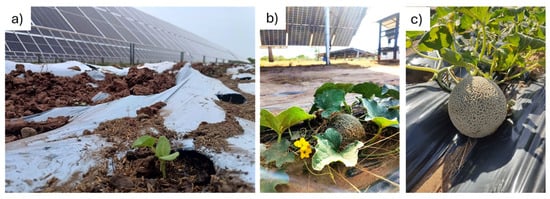

Initially, a 50-plant pilot plot with melon plants was implemented with an inter-plant spacing distance of 45 cm [44]. The 50-plant pilot plot with melon plants achieved 100% establishment success, with normal plant development patterns (see Figure 3). A drip irrigation system was installed and connected to an existing deep well, providing a reliable water supply for crop irrigation throughout the growing cycle, varying the amount of water supplied according to the specific demand for each phenological cycle. According to Baquero Maestre et al. [44], the amount of water consumed for each melon plant per day during the vegetative growth period was 1 L, 1.2 L during the reproduction period, and 3 L during the fruit set period.

Figure 3.

Experimental melon pilot plot on the Solar Valle de Gandalf SSSF, San Diego (Cesar, Colombia): (a) melon seedling; (b) melon fruit beginning the fruit-filling stage; (c) melon fruit in the middle of the fruit-filling stage, diameter ~135 mm.

Despite being the first crop established on this land after several years of extensive cattle ranching (which typically results in compacted soil), the plants exhibited adequate vigor throughout the production cycle under the management provided. Canopy expansion, flowering, and fruit filling occurred within the timeframes reported for melon cultivation under drip irrigation in Colombia’s hot tropical environments, where production cycles typically range from 60 to 70 days depending on the cultivar and management practices [44]. Under the partial shading conditions imposed by the agrivoltaic structure, the plant architecture remained compact and prostrate. By the fruit-filling stage, 70% of the plants produced an average of two fruits each, measuring approximately 10 cm to 12 cm in diameter.

Given that melon production required higher investment than watermelon in our local market, it was decided to select watermelon for the full-scale pilot implementation in the 2.5 ha SSSF.

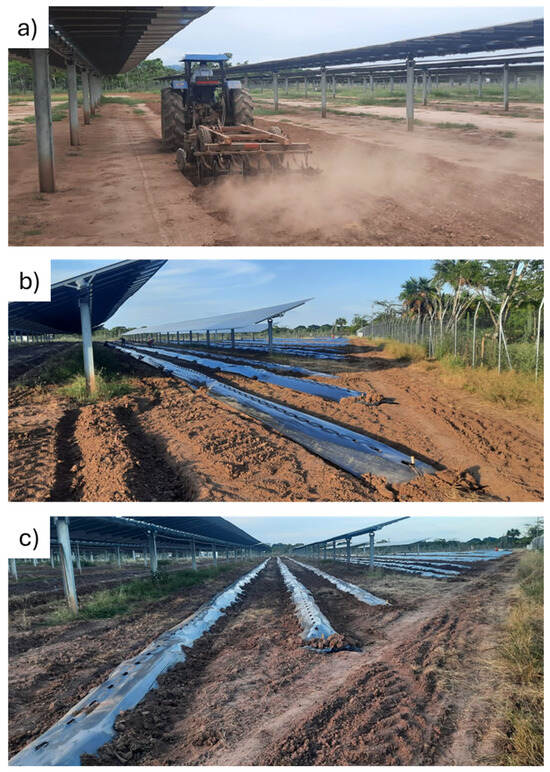

The full-scale pilot implementation for the watermelon crop was initiated across the SSSF, accommodating a total of 4500 watermelon plants in the 2.5 ha of the SSSF. The inter-plant spacing distance was 45 cm [45], and three crop rows were established between the photovoltaic module rows (see Figure 4). The total effectively cultivated area in the SSSF was 0.5 ha out of the 2.5 ha of the SSSF. All watermelon plants had normal growth and development, without evident phenological delays at the selected planting density.

Figure 4.

(a) Mechanization process for watermelon cultivation on the Solar Valle de Gandalf SSSF, San Diego (Cesar, Colombia); (b,c) show different views of the watermelon crop plantations.

Soil mechanization between panel rows was a critical technical challenge, which was successfully addressed through the identification and adaptation of appropriately sized tractors capable of operating without interfering with the photovoltaic infrastructure (see Figure 4a). Meanwhile, Figure 4b,c show different views of the watermelon plantations. A drip irrigation system provided water for the watermelon crop (following the procedures by Cohen-Manrique et al. [45]) to be 1.5 L of water for each watermelon plant per day during the vegetative growth period, 3.0 L during the reproduction period, and 4 L during the fruit set period. The crop was successfully established across the entire effective cultivated area, showing vigorous vegetative growth and normal canopy development, reaching flowering within the expected timeframe (33 to 40 days) reported for watermelon production under drip irrigation in Colombia’s warm region [46], as can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Experimental watermelon pilot plot on the Solar Valle de Gandalf SSSF, San Diego (Cesar, Colombia).

While this pilot crop was established, operation and maintenance work was carried out on the photovoltaic plant with normality. This work included cleaning the panels, which was carried out normally thanks to the safety distance between the crops and the panels. Additionally, the washing process was conducted using biodegradable soaps that did not generate any negative effects on the plants.

4. Discussion

This study shows that the technical implementation of agrivoltaic systems in Colombian SSSFs under tropical dry forest conditions can be achievable. The 6 h–7 h of direct sunlight between panel rows, combined with average PAR values of 1342 μmol/m2/s (82–92% of full sun depending on position), provided sufficient photosynthetically active radiation for shade-tolerant crop cultivation, exceeding threshold values (600 μmol/m2/s–800 μmol/m2/s) identified in previous research for maintaining adequate photosynthesis in moderately shade-tolerant species [47,48].

The use of bifacial panels on single-axis tracking systems represented a dual-optimization strategy particularly well-suited to agrivoltaics applications: (i) maximizing energy capture through both direct irradiance on the front surface and ground-reflected albedo on the rear surface, with bifacial gain potentially enhanced by high-albedo mulching materials used in horticultural production [49]; and (ii) maintaining agricultural productivity through dynamic shade patterns that distribute light more evenly throughout the day compared to fixed-tilt systems, reducing periods of excessive shading [12].

The measured PAR distribution revealed that there was no significant difference between positions A, B, C, D, and E (see Figure 2). These results can be attributed to the SSSF configuration and geographical location. Depending on the SSSF configuration, careful spatial planning within the installation can optimize crop placement according to light requirements, thereby maximizing overall system productivity through spatial heterogeneity management [50]. This strategy aligned with recent agrivoltaics research emphasizing the importance of matching crop light requirements to the spatial light gradient created by panel configurations [51]. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that PAR measurements should be conducted daily and characterized for different weather conditions, for example, cloudy, sunny, or partially cloudy days. These results will provide a deeper understanding of the long-term impact of the light environment.

The slight soil alkalinity (i.e., pH 7.4) and identified nutrient deficiencies represented manageable challenges through targeted fertilization programs. An organoleptic field test revealed evidence for soil moisture retention in the areas between rows of photovoltaic modules in front of areas that do not have shade at any moment of the day, which can reduce the amount of water in the irrigation system. This finding aligned with those from arid agrivoltaic systems in Arizona, California, and India, where it was concluded that moisture can potentially reduce irrigation requirements by 10–29% compared to conventional cultivation [52]. This water conservation benefit is particularly significant in the study region, where annual potential evapotranspiration (2500 mm) substantially exceeds precipitation (1315 mm), and water scarcity limits agricultural development [53,54]. Nevertheless, soil moisture sensors should be installed for detailed monitoring. Additionally, irrigation volume tracking will be essential for economic analysis and water-saving potential.

The selection of watermelon and melon capitalized on existing local knowledge while leveraging species-specific shade tolerance characteristics. This adaptive management approach was consistent with successful agrivoltaics implementations in temperate climates and arid regions [55,56]. The limited crop height imposed by 2.4 m panel elevation constrained species selection but aligned with ground-level cultivation systems proven effective in other agrivoltaics contexts. Future installations could consider elevated mounting structures to accommodate taller crop species or perennial systems, as demonstrated in vertical agrivoltaic configurations [12]. Our case study positively assessed the feasibility of agrivoltaic systems; however, pre-trials and control experiments will be needed to provide a full comparison for crop selection.

The successful adaptation of mechanization equipment represented a critical achievement for scalable agrivoltaics implementation. This challenge has been identified as a primary barrier in other agrivoltaic systems, often requiring minimum tillage approaches or specialized equipment. The identification of appropriately sized tractors enables conventional soil preparation while respecting structural constraints, potentially reducing long-term operational costs compared to manual labor alternatives [57]. The implementation of mechanization equipment is crucial for the adoption of agrivoltaics in developing countries such as Colombia, where cost considerations often drive technological choices [58,59].

The integration of drip irrigation systems connected to deep wells addresses the fundamental challenge of water availability in Colombia’s high-radiation zones. With annual evapotranspiration (2500 mm) substantially exceeding precipitation (1315 mm), the irrigation solution is a must for the case of commercial production. The potential for reduced irrigation requirements under partial shade conditions, as suggested by international studies, could provide significant resource conservation benefits in water-limited environments.

While complete energy production data waits for the SSSF’s full operation, the integration of white plastic mulch (i.e., agromulch) for crop cultivation had an intriguing synergy: agronomic benefits (i.e., weed suppression, soil moisture retention, temperature modification) combined with increased albedo for enhanced bifacial panel performance should be further evaluated in the following studies. This mutual benefit exemplifies the optimization potential inherent in well-designed agrivoltaic systems. However, potential trade-offs must be acknowledged. Panel shading may favor fungal disease development in high-humidity conditions, as noted in the environmental characterization. This necessitates enhanced phytosanitary monitoring and potentially increased management input compared to open-field cultivation.

The standardized 2.5 ha SSSF format has both advantages and constraints for agrivoltaics scaling. The distributed nature of multiple small installations across diverse regions enables adaptive management and regional crop optimization—valuable for a geographically diverse country like Colombia. However, economies of scale in installation and management might be reduced compared to utility-scale implementations. The model’s primary strength lies in its accessibility for rural electrification and agricultural development in regions lacking grid infrastructure or large-scale investment capacity. This aligns with the distributed generation paradigm increasingly recognized as appropriate for Latin American energy transitions [51].

5. Conclusions

This pilot implementation demonstrated the technical feasibility of implementing agrivoltaic systems in Colombian solar SSSFs, specifically in the tropical dry forest conditions of San Diego, Cesar. The integration of watermelon and melon cultivation with bifacial solar panels on tracking systems represented a viable approach to optimizing land use efficiency while addressing both energy generation and agricultural production objectives. However, definitive conclusions regarding crop yields, economic returns, water use efficiency quantification, and long-term system sustainability require completion of full growing cycle monitoring, multi-season data collection, and replicated experimental studies. The current pilot project represents an essential initial phase, generating preliminary evidence and operational experience upon which expanded research and implementation can be built.

Agrivoltaic systems represent a promising pathway for Colombia’s dual energy transition and agricultural development objectives in rural regions, offering sustainable solutions that address food security, renewable energy generation, water conservation, and rural employment simultaneously. The successful establishment of this pilot project provided a foundation for expanded research across Colombia’s diverse agroecological zones and contributed valuable evidence to the growing global knowledge base on tropical agrivoltaic systems.

Future research should address: (i) comparative yield analyses between agrivoltaics and conventional cultivation systems; (ii) economic return on investment calculations incorporating both agricultural and energy revenues including a preliminary cost-benefit analysis framework; (iii) water use efficiency quantification under partial shade conditions for water saving potential, as well as continuous soil moisture sensing for reducing irrigation; (iv) evaluation of alternative crop species and rotation systems based on pre-trials and control groups; and (v) assessment of panel maintenance implications from agricultural activities. Additionally, expansion to other Colombian regions with different climatic conditions (i.e., Andean highlands, humid tropics) would enhance understanding of agrivoltaics applicability across the country’s diverse agricultural zones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.B.-D.L.C., D.C.D., D.F.T. and L.V.; Data curation, C.M.B.-D.L.C., D.F.T. and L.V.; Formal analysis, C.M.B.-D.L.C., B.J.A., D.F.T. and L.V.; Funding acquisition, L.V.; Investigation, C.M.B.-D.L.C. and L.V.; Methodology, C.M.B.-D.L.C., D.C.D., D.F.T. and L.V.; Project administration, L.V.; Resources, C.M.B.-D.L.C. and L.V.; Software, C.M.B.-D.L.C. and L.V.; Supervision, D.F.T. and L.V.; Validation, C.M.B.-D.L.C., D.F.T. and L.V.; Visualization, B.J.A., D.F.T. and L.V.; Writing—original draft, B.J.A., D.C.D., D.F.T. and L.V.; Writing—review and editing, D.F.T. and L.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, project reference Hermes 57862.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

C.M.B.-D.L.C. expresses his gratitude to the Universidad Nacional de Colombia for academic support and guidance throughout the development of this project. The authors express their gratitude to Unergy and Solenium for providing access to the solar infrastructure, technical coordination, and on-site operational assistance. The authors also extend sincere appreciation to Edgardo Oñate, a local farmer whose collaboration, field knowledge, and support during pilot implementation were essential to the success of the agrivoltaics demonstration.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Carlos M. Burgos-De La Cruz is employed by SOLENIUM S.A.S. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations were used in this manuscript:

| LCOE | Levelized cost of electricity |

| LERs | Land equivalent ratios |

| IDEAM | Colombian Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies |

| PAR | Photosynthetically active radiation |

| AC | Alternating current |

| DC | Direct current |

References

- Kalair, A.; Abas, N.; Saleem, M.S.; Kalair, A.R.; Khan, N. Role of energy storage systems in energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables. Energy Storage 2021, 3, e135. [Google Scholar]

- Svanera, L.; Ghidesi, G.; Knoche, R. Agrovoltaico®: 10 years design and operation experience. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2361, 090002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolinger, M.; Seel, J.; Robson, D.; Warner, C. Utility-Scale Solar Data Update: 2020 Edition; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL): Berkely, CA, USA, 2020.

- Amaducci, S.; Potenza, E.; Colauzzi, M. Developments in agrivoltaics: Achieving synergies by combining plants with solar photovoltaic power systems. In Energy-Smart Farming: Efficiency; Studying the Impact of Agrivoltaic Systems Across the Water-Energy-Food (WEF) Nexus; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Tawalbeh, M.; Al-Othman, A.; Kafiah, F.; Abdelsalam, E.; Almomani, F.; Alkasrawi, M. Environmental impacts of solar photovoltaic systems: A critical review of recent progress and future outlook. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 759, 143528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAAOOTUN. Faostat; Global Agricultural. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/RL (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Livera, A.; Lodolini, E.M.; Saraginovski, N.; Crescenzi, S.; Neri, D.; Manganaris, G.A. Current trends and challenges of agrivoltaic systems towards sustainable production of temperate fruit crops under intensive orchard setups. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 348, 114210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asa’a, S.; Reher, T.; Rongé, J.; Diels, J.; Poortmans, J.; Radhakrishnan, H.S.; van der Heide, A.; Van de Poel, B.; Daenen, M. A multidisciplinary view on agrivoltaics: Future of energy and agriculture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 200, 114515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarr, A.; Soro, Y.M.; Tossa, A.K.; Diop, L. Agrivoltaic, a synergistic co-location of agricultural and energy production in perpetual mutation: A comprehensive review. Processes 2023, 11, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarelli, A.; Mazzeo, A.; Ali, S.A.; Ferrara, G. Shading enhanced microclimate variability, photomorphogenesis and yield components in a grapevine agrivoltaic system in semi-arid Mediterranean conditions in Puglia region, southeastern Italy. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 350, 114311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biró-Varga, K.; Sirnik, I.; Stremke, S. Landscape user experiences of interspace and overhead agrivoltaics: A comparative analysis of two novel types of solar landscapes in the Netherlands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 109, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, P.E.; Stridh, B.; Amaducci, S.; Colauzzi, M. Optimisation of vertically mounted agrivoltaic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 325, 129091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalgynbayeva, A.; Gabnai, Z.; Lengyel, P.; Pestisha, A.; Bai, A. Worldwide research trends in agrivoltaic systems—A bibliometric review. Energies 2023, 16, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Mancebo, J.S.; López-Luque, R.; Fernández-Ahumada, L.M.; Ramírez-Faz, J.C.; Gómez-Uceda, F.J.; Varo-Martínez, M. Spatial distribution model of solar radiation for agrivoltaic land use in fixed PV plants. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahrawi, A.A.; Aly, A.M. A review of agrivoltaic systems: Addressing challenges and enhancing sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Urrego, D.; Rodríguez-Urrego, L. Photovoltaic energy in Colombia: Current status, inventory, policies and future prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.R.; Krumm, A.; Schattenhofer, L.; Burandt, T.; Montoya, F.C.; Oberländer, N.; Oei, P.-Y. Solar PV generation in Colombia-A qualitative and quantitative approach to analyze the potential of solar energy market. Renew. Energy 2020, 148, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra-Fernandez, M.; Sarmiento, A.T.; Cardenas, L.M. Sustainability assessment of the solar energy supply chain in Colombia. Energy 2023, 282, 128735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, C.W. The Water Balance; Drexel Institute of Technology, Laboratory of Climatology: Centerton, NJ, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Dourado-Neto, D.; Jong van Lier, Q.d.; Metselaar, K.; Reichardt, K.; Nielsen, D.R. Critério geral para iniciar o balanço hídrico pelo método de Thornthwaite e Mather. Sci. Agric. 2010, 67, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ezemonye, M.N.; Emeribe, C.N. Irrigation Schedules for Selected Food Crops Using Water Balance Book-Keeping Method. Agric. Trop. et Subtrop. 2014, 47, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, I.M.G.; Rodríguez, J.M.M.; Díaz, A.M.S. Guía de Muestreo de Suelo para Análisis Microbiológico; Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria—AGROSAVIA: Mosquera, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, N.C.; Weil, R.R.; Weil, R.R. The Nature and Properties of Soils; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Havlin, J.L.; Tisdale, S.L.; Nelson, W.L.; Beaton, J.D. Soil Fertility and Fertilizers; Pearson Education India: Noida, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, W.T. Potassium influences on yield and quality production for maize, wheat, soybean and cotton. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Katsikogiannis, O.A.; Ziar, H.; Isabella, O. Integration of bifacial photovoltaics in agrivoltaic systems: A synergistic design approach. Appl. Energy 2022, 309, 118475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Li, S.; Yang, K.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, L.; Liu, P.; She, D. A method for estimating surface albedo and its components for partial plastic mulched croplands. J. Hydrometeorol. 2023, 24, 1069–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarshoud, A.; Abdel-halim, M.; Almasri, R.A.; Alshwairekh, A.M. Experimental Study of Bifacial Photovoltaic Module Performance on a Sunny Day with Varying Backgrounds Using Exergy and Energy Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Mikofski, M. Slope-Aware Backtracking for Single-Axis Trackers; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA; Det Norske: Oslo, Norway, 2020.

- Marrou, H.; Guilioni, L.; Dufour, L.; Dupraz, C.; Wery, J. Microclimate under agrivoltaic systems: Is crop growth rate affected in the partial shade of solar panels? Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 177, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Casanovas, N.; Mwebaze, P.; Khanna, M.; Branham, B.; Time, A.; DeLucia, E.H.; Bernacchi, C.J.; Knapp, A.K.; Hoque, M.J.; Du, X.; et al. Knowns, uncertainties, and challenges in agrivoltaics to sustainably intensify energy and food production. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, J.C. Bell pepper (Capsicum annum L.) crop as affected by shade level: Fruit yield, quality, and postharvest attributes, and incidence of phytophthora blight (caused by Phytophthora capsici Leon.). HortScience 2014, 49, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafoya, F.A.; Juárez, M.G.Y.; Orona, C.A.L.; López, R.M.; Alcaraz, T.d.J.V.; Valdés, T.D. Sunlight transmitted by colored shade nets on photosynthesis and yield of cucumber. Ciência Rural. 2018, 48, e20170829. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, B.d.J.; Rodrigues, G.A.; Santos, A.R.d.; Anjos, G.L.d.; Costa, F.M. Watermelon initial growth under different hydrogel concentrations and shading conditions. Rev. Caatinga 2020, 32, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Fukuoka, N.; Noto, S. Improvement of greenhouse microenvironment and sweetness of melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruits by greenhouse shading with a new kind of near-infrared ray-cutting net in mid-summer. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 218, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K. The spectral irradiance, growth, photosynthetic characteristics, antioxidant system, and nutritional status of green onion (Allium fistulosum L.) grown under different photo-selective nets. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 650471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachma, I.A.; Sulistyaningsih, E.; Suci Handayani, V.D. Effects of color shade-net on the growth and yield quality of garlic in the lowlands area. Agric. Sci./Ilmu Pertan. 2025, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Marín, J.; Galvez, A.; del Amor Saavedra, F.; Manera Bassa, F.J.; Carrero-Blanco, J.; Brotons Martínez, J. Photoselective Shade Netting in a Sweet Pepper Crop Accelerates Ripening Period and Enhances the Overall Fruits Quality and Yield. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2025, 24, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar]

- DANE. Boletín Mensual Insumos y Factores Asociados a la Producción Agropecuaria; DANE: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019.

- Calatayud, A.; Deltoro, V.; Alexandre, E.; Barreno, E. Acclimation potential to high irradiance of two cultivars of watermelon. Biol. Plant. 2000, 43, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, T.; Ito, A.; Motomura, Y.; Ito, M.; Togashi, M. Changes in fruit quality as influenced by shading of netted melon plants (Cucumis melo L.’Andesu’and’Luster’). J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2000, 69, 563–569. [Google Scholar]

- Klokov, A.V.; Loktionov, E.Y.; Loktionov, Y.V.; Panchenko, V.A.; Sharaborova, E.S. A mini-review of current activities and future trends in agrivoltaics. Energies 2023, 16, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero Maestre, C.E.; Arcila Cardona, Á.M.; Arias Bonilla, H.; Yacomelo Hernández, M.J. Modelo Productivo del Cultivo de Melón (Cucumis melo L.) para la Región Caribe; Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria—AGROSAVIA: Mosquera, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Manrique, C.S.; Rodríguez Manrique, J.A.; Salgado Ordosgoitia, R.D. Modelado del microclima de un cultivo de candía (Citrullus lanatus) en la sub-región sabana del departamento de Sucre, Colombia. Inf. Tecnológica 2018, 29, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, G.A.; Chacón Díaz, A.; Linares, V.M.; Rey, C.A.; Orduz, J.O. El Cultivo de la Sandia o Patilla (Citrullus lanatus) en el Departamento del Meta; Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria—AGROSAVIA: Villavicencio, Colombia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Y.; Gao, Y. Analysis of light environment under solar panels and crop layout. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 44th Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), Washington, DC, USA, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 2048–2053. [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets, Ü. A review of light interception in plant stands from leaf to canopy in different plant functional types and in species with varying shade tolerance. Ecol. Res. 2010, 25, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.H.; Imran, H.; Younas, R.; Butt, N.Z. The optimization of vertical bifacial photovoltaic farms for efficient agrivoltaic systems. Sol. Energy 2021, 230, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Bopp, G.; Goetzberger, A.; Obergfell, T.; Reise, C.; Schindele, S. Combining PV and food crops to Agrophotovoltaic–optimization of orientation and harvest. In Proceedings of the 27th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition, EU PVSEC, Frankfurt, Germany, 24–28 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dinesh, H.; Pearce, J.M. The potential of agrivoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A.; Minor, R.L.; Sutter, L.F.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Blackett, D.T.; Thompson, M.; Dimond, K.; Gerlak, A.K.; Nabhan, G.P.; et al. Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus in drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino, V.E.d.N.; Studart, T.M.d.C.; Campos, J.N.B.; Pestana, C.J.; Luna, R.M.; Alves, J.M.B. Trends in crop reference evapotranspiration and climatological variables across Ceará State–Brazil. Rev. Bras. de Meteorol. 2019, 34, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Malik, I.; Wistuba, M.; Sun, L.; Yang, M.; Wang, Q.; Yu, R. Water resources evaluation in arid areas based on agricultural water footprint—A case study on the edge of the Taklimakan Desert. Atmosphere 2022, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Hartung, J.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Högy, P. Agrivoltaic system impacts on microclimate and yield of different crops within an organic crop rotation in a temperate climate. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, P.; Meena, H.M.; Yadav, O. Spatial and temporal variation of photosynthetic photon flux density within agrivoltaic system in hot arid region of India. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 209, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M.; Kang, J.; Reise, C.; Schindele, S.; Bopp, G.; Ehmann, A.; Weselek, A.; Högy, P.; Obergfell, T. Combining food and energy production: Design of an agrivoltaic system applied in arable and vegetable farming in Germany. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselek, A.; Ehmann, A.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Schindele, S.; Högy, P. Agrophotovoltaic systems: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Hickey, T.; Pearce, J.M. Solar energy modelling and proposed crops for different types of agrivoltaics systems. Energy 2024, 304, 132074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.