Assessing the Suitability of Digestate and Compost as Organic Fertilizers: A Comparison of Different Biological Stability Indices for Sustainable Development in Agriculture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Description and Sample Characterization

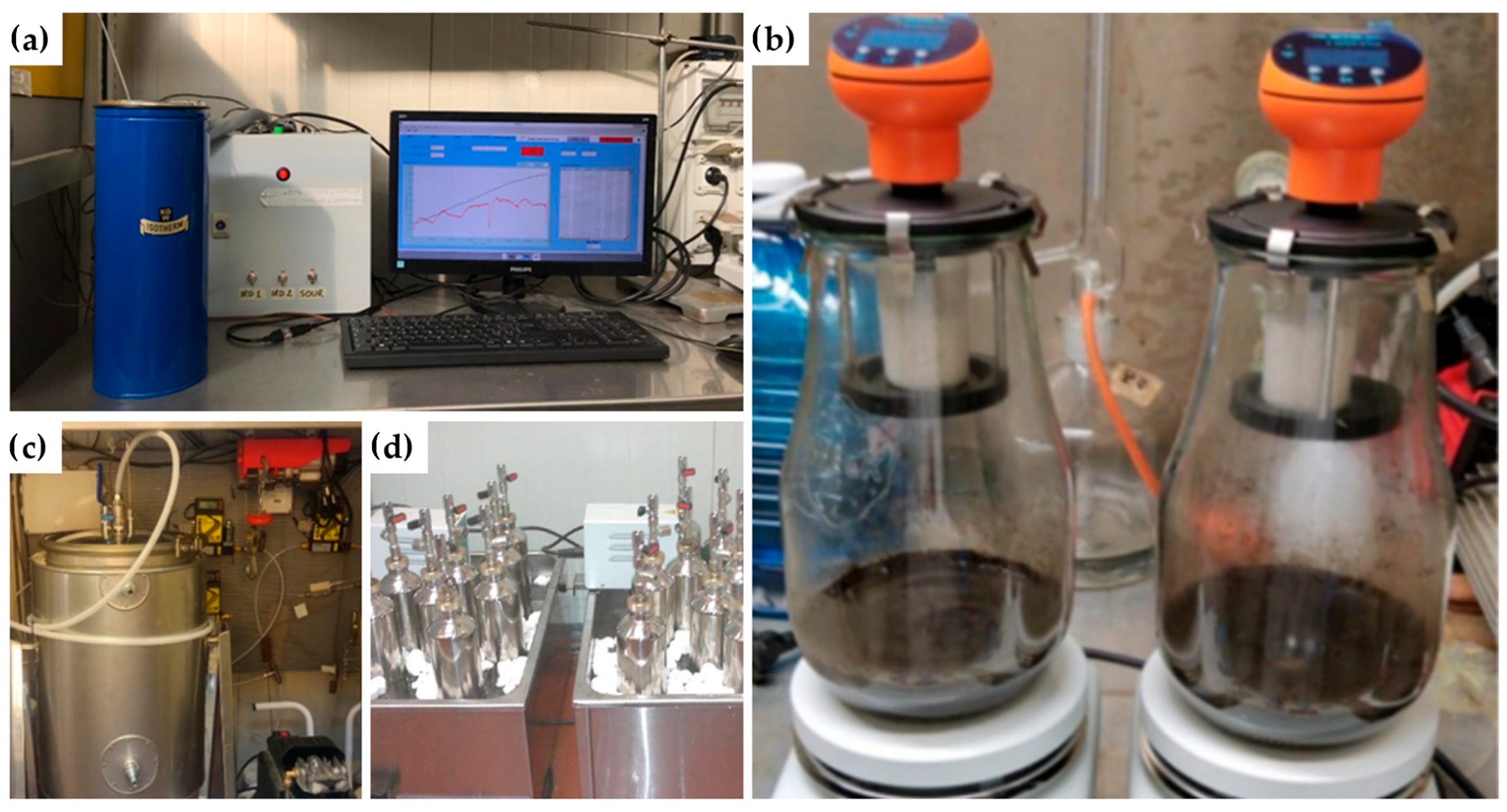

2.1.1. Self-Heating (SH)

2.1.2. Oxygen Uptake Rate (OUR) Test

- 180 mL of demineralized water;

- 10 mL of a complete nutrient solution;

- 10 mL of buffer solution;

- 5 mL of ATU solution.

- OC is the oxygen consumption [mmolO2 per kg of organic matter].

- ΔP is the change in pressure in the reactor’s headspace [kPa].

- R is the gas constant [8.314 L ∙ kPa K−1 mol−1].

- T is the test temperature [°C].

- W is the initial mass of the sample [kg].

- DM is the dry matter content [% by weight].

- OM is the organic matter content [%TVS/TS].

- Vgas is the volume of the gas phase in the reactor [ml].

2.1.3. Dynamic Respirometric Index (DRI) Test

2.1.4. Residual Biogas Potential (RBP) Test

2.2. Predictive Model and Analytical Relationships Between the Analyzed Indices

- Standardization of the variables X (“zX”) and Y (“zY”), which are re-expressed to have means equal to 0 and standard deviation (s.d.) equal to 1 (Equations (2) and (3)).

- Calculation of the correlation coefficient as the mean product of the paired standardized scores, considering sample size n (Equation (4)).

- Relationship between RBP, OUR, and SH, representing a comparison between the biological stability indices permitted by European Fertilizer Regulation (EU) 2019/1009.

- 2.

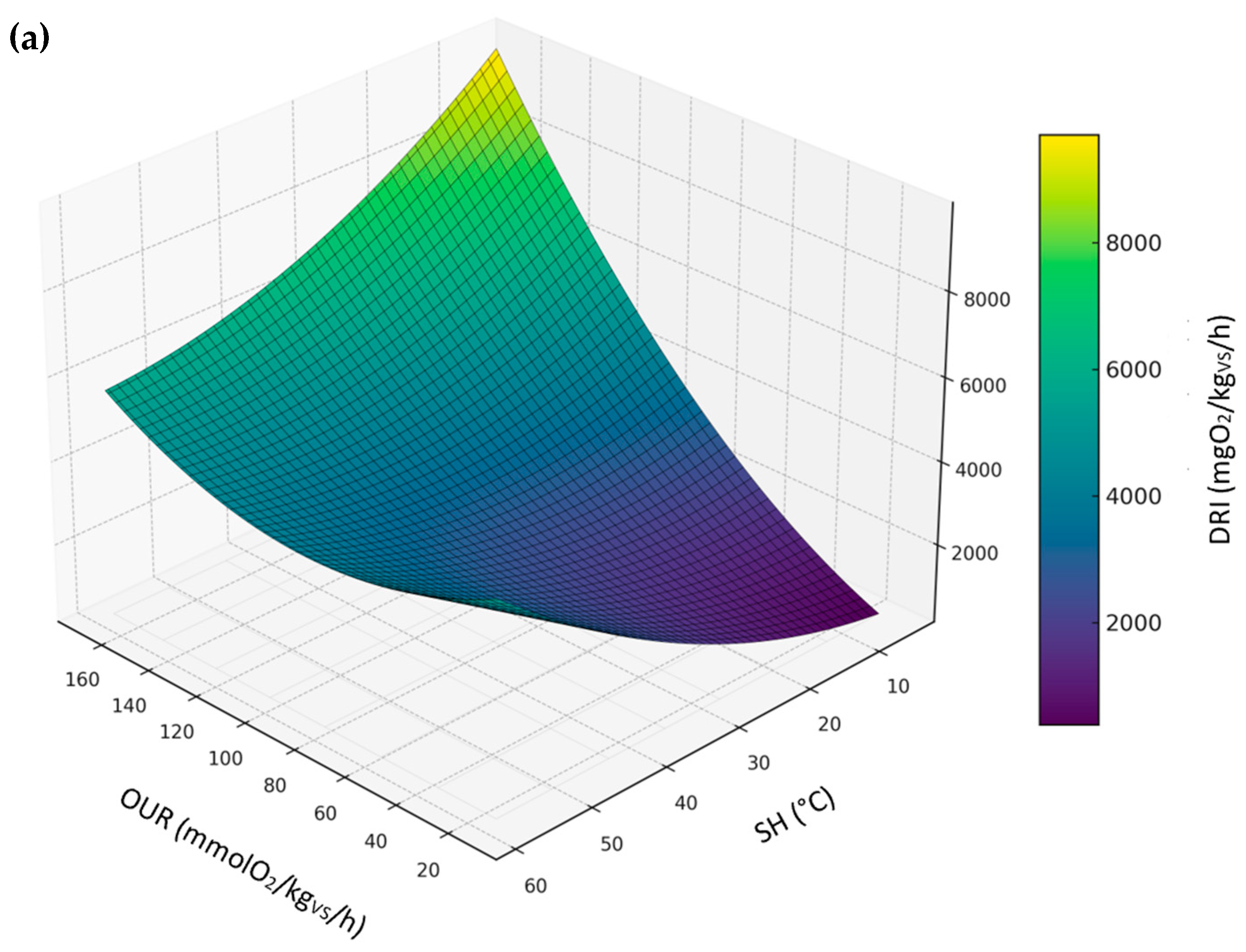

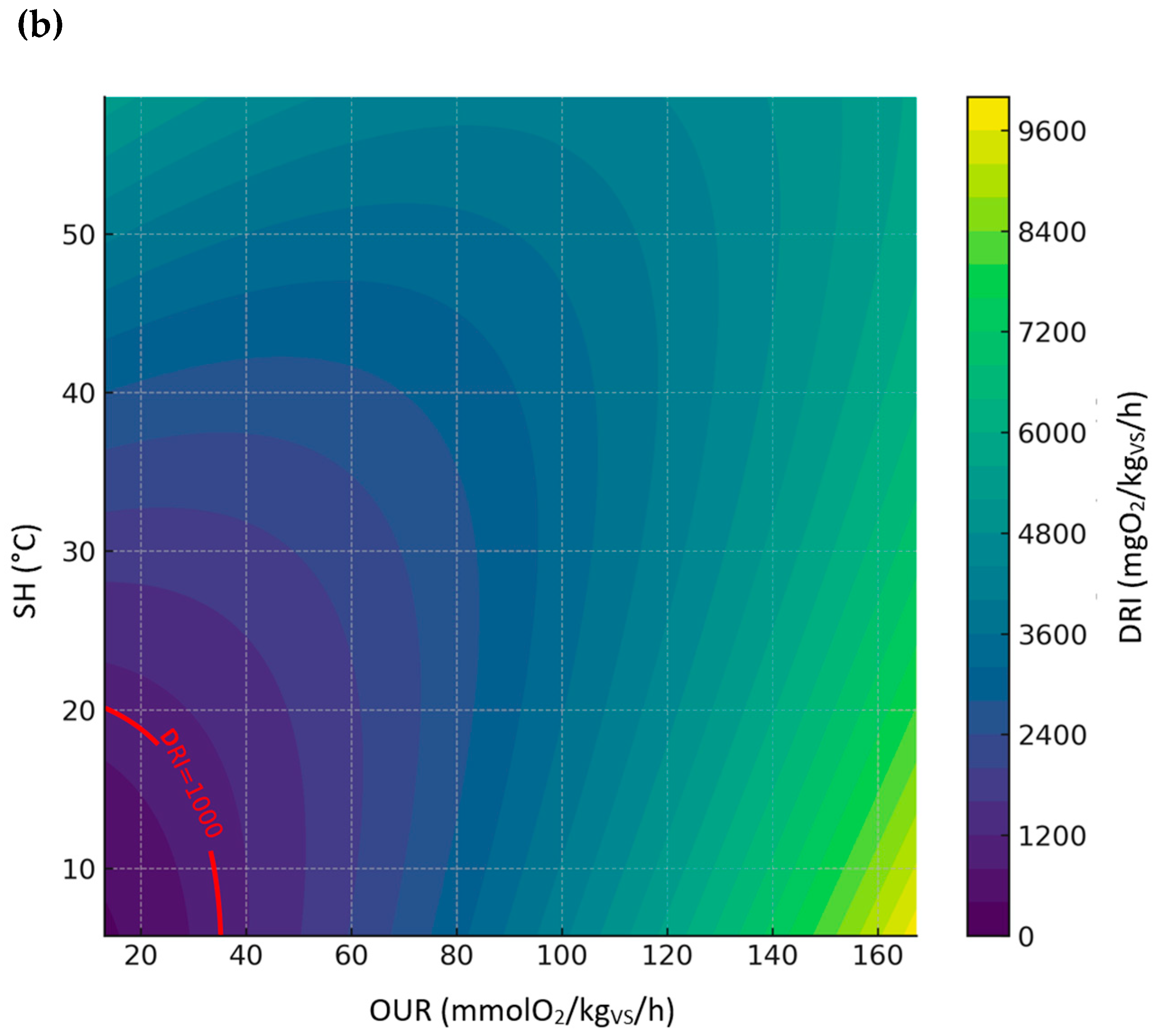

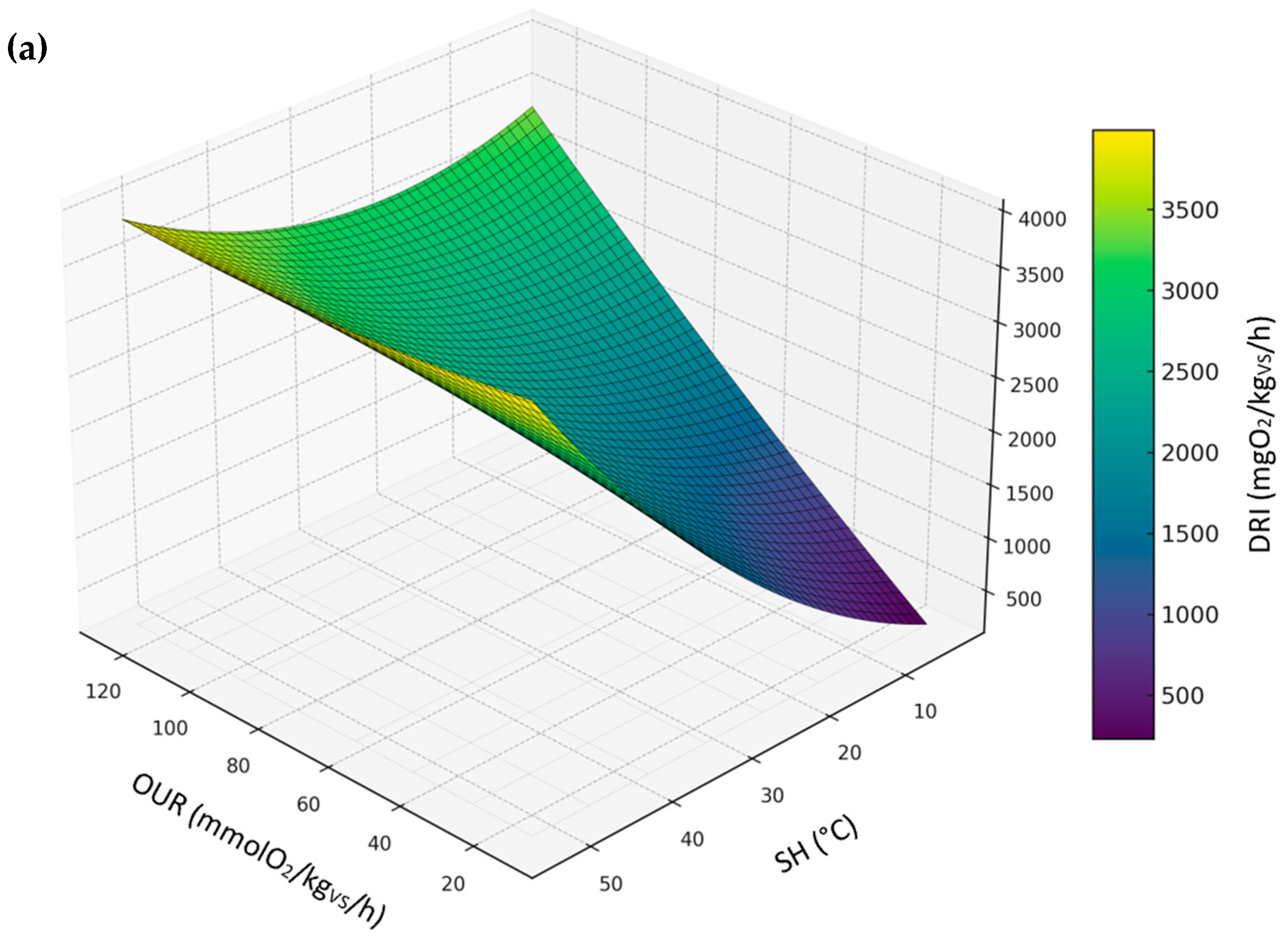

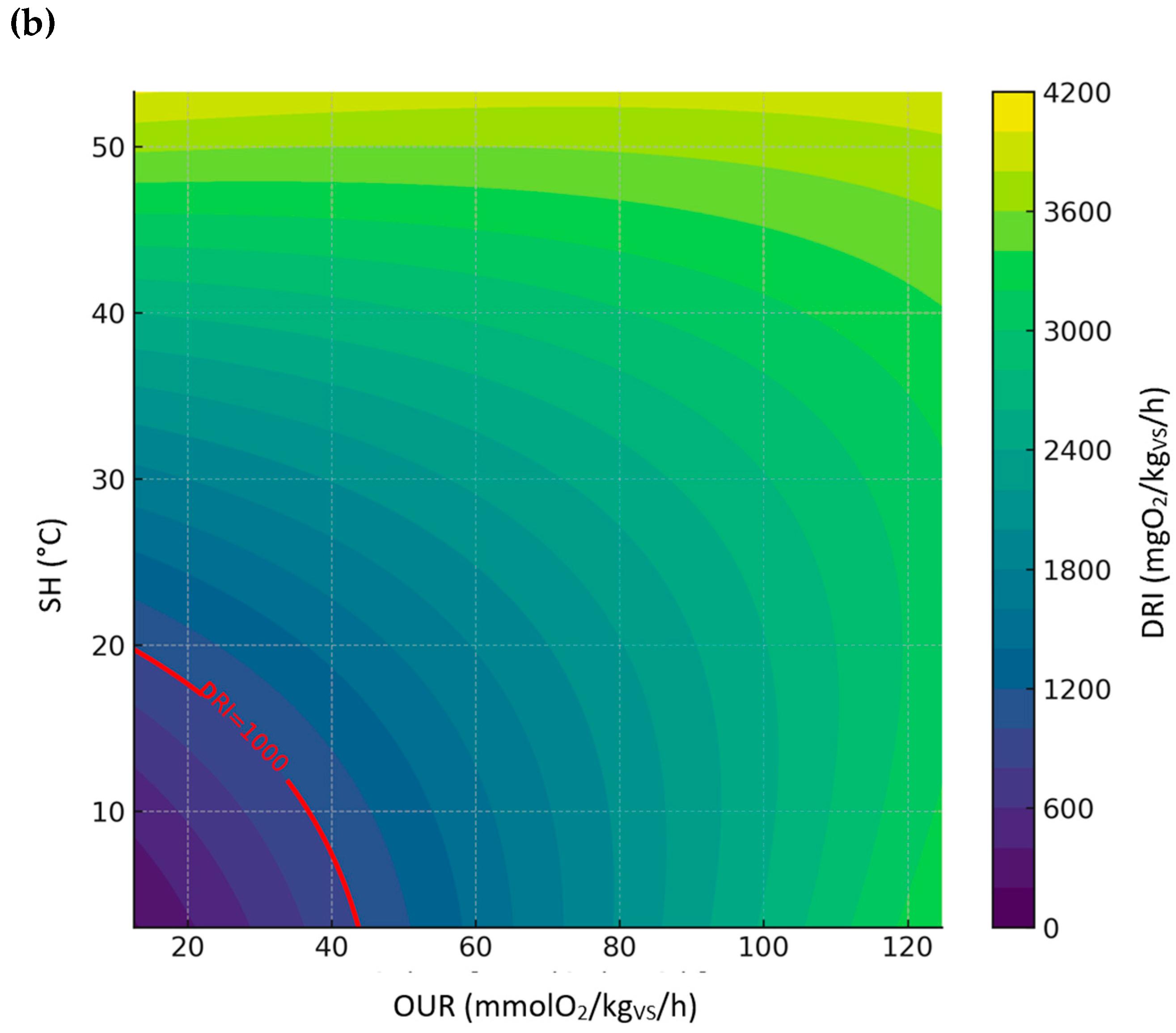

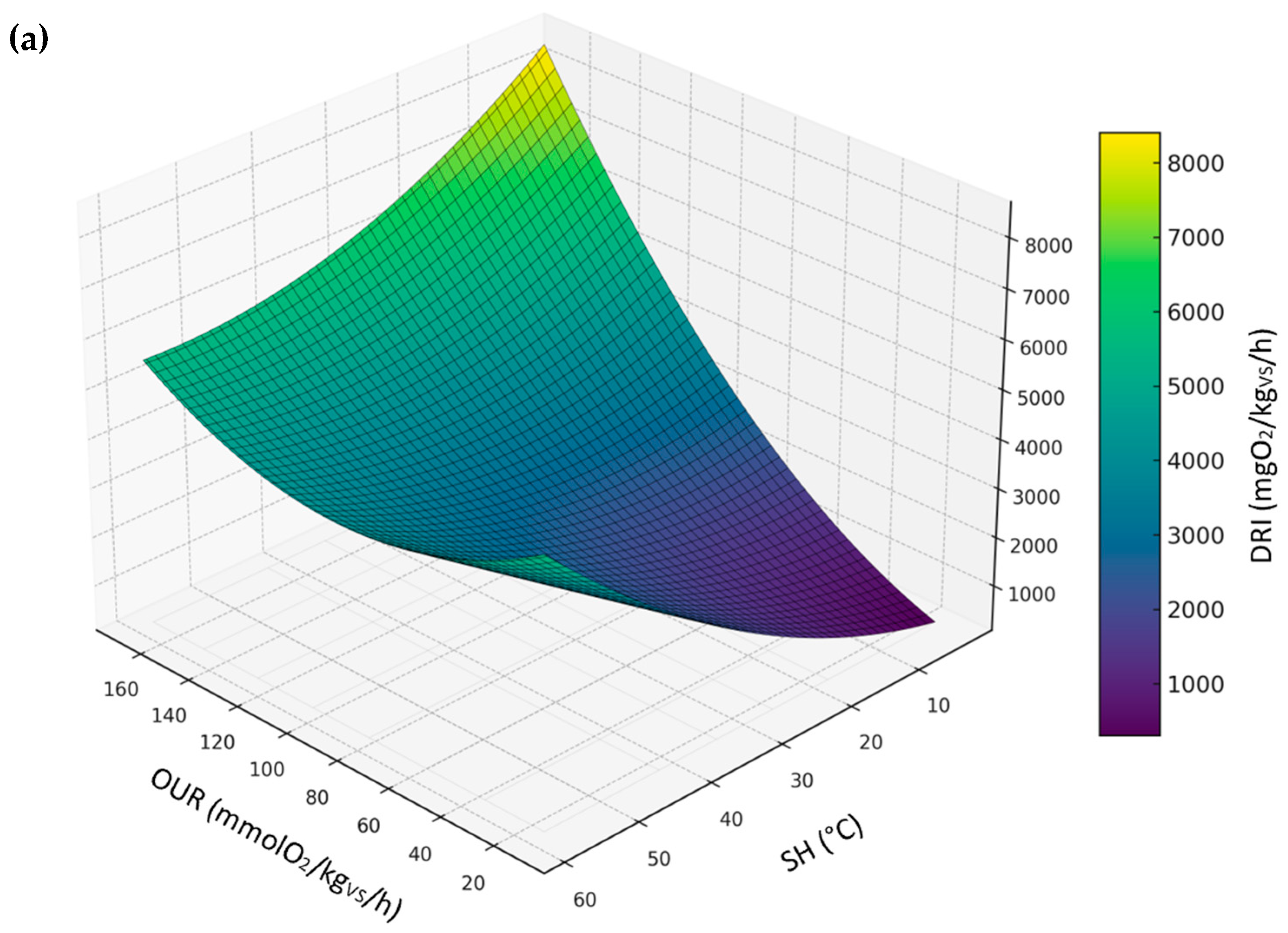

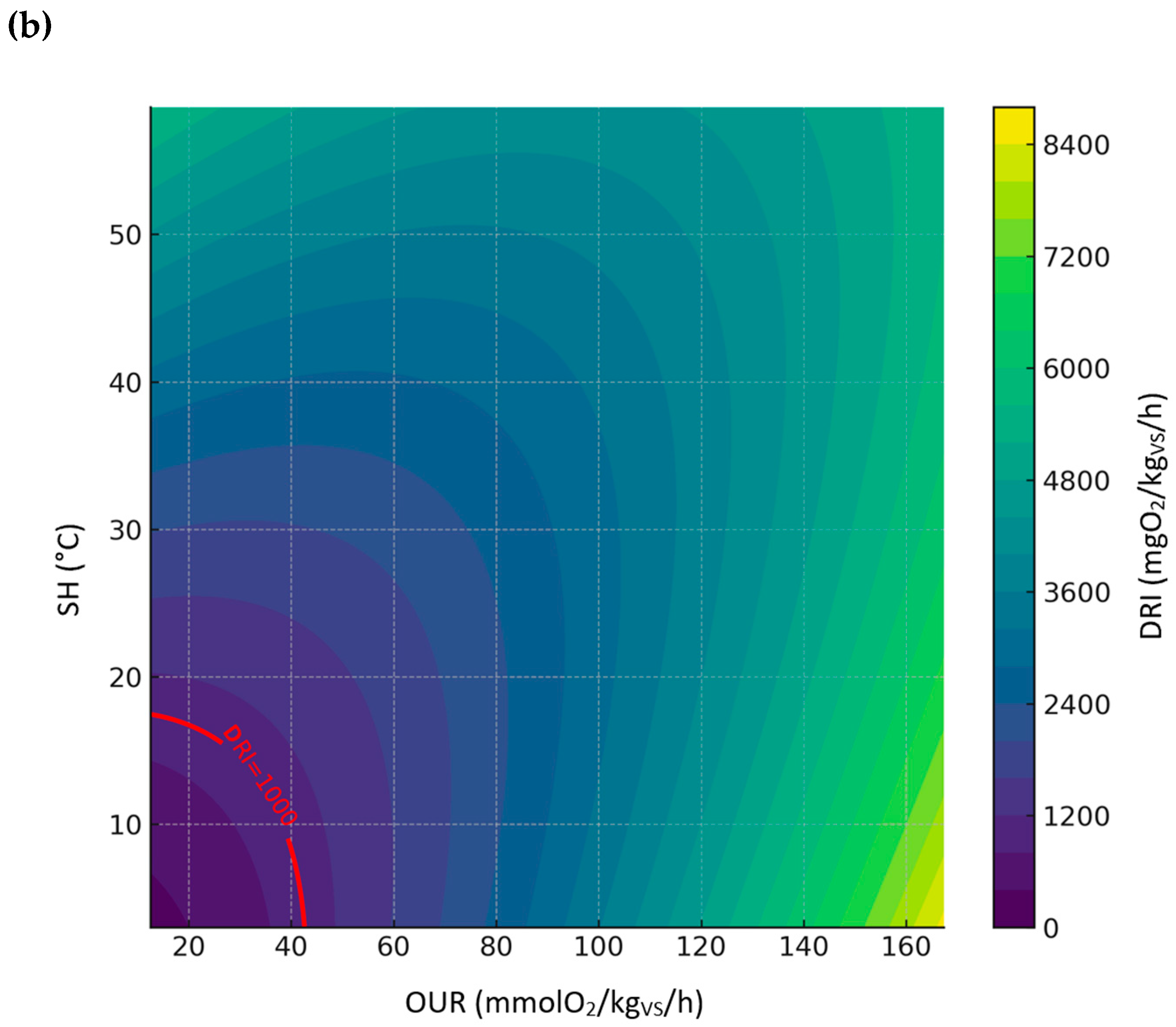

- DRI as a function of OUR and SH, representing a comparison between biological stability indices conducted under aerobic conditions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Insights from the Analysis of Biological STABILITY Indices

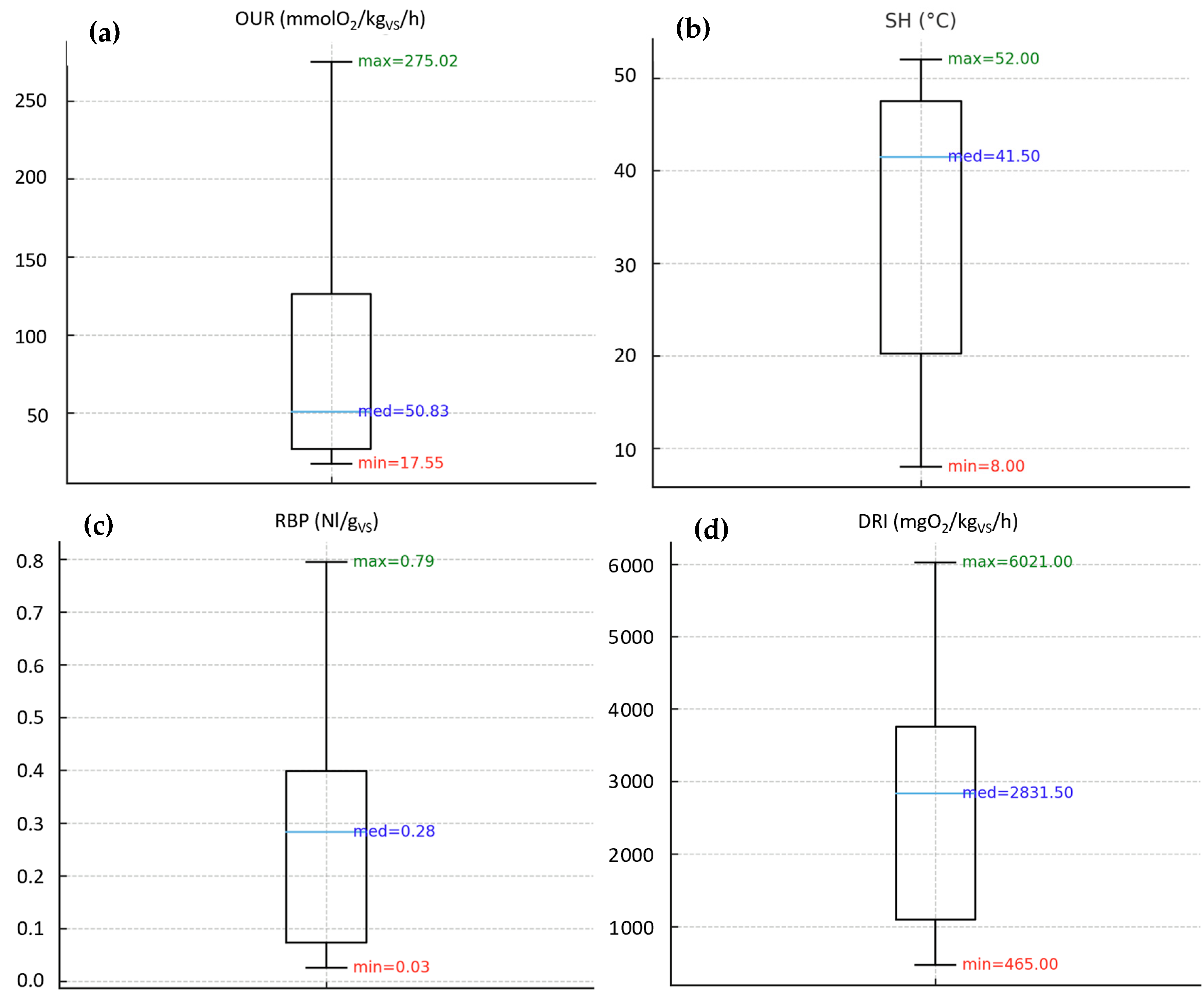

3.1.1. Biological Stability Indices on Compost Samples

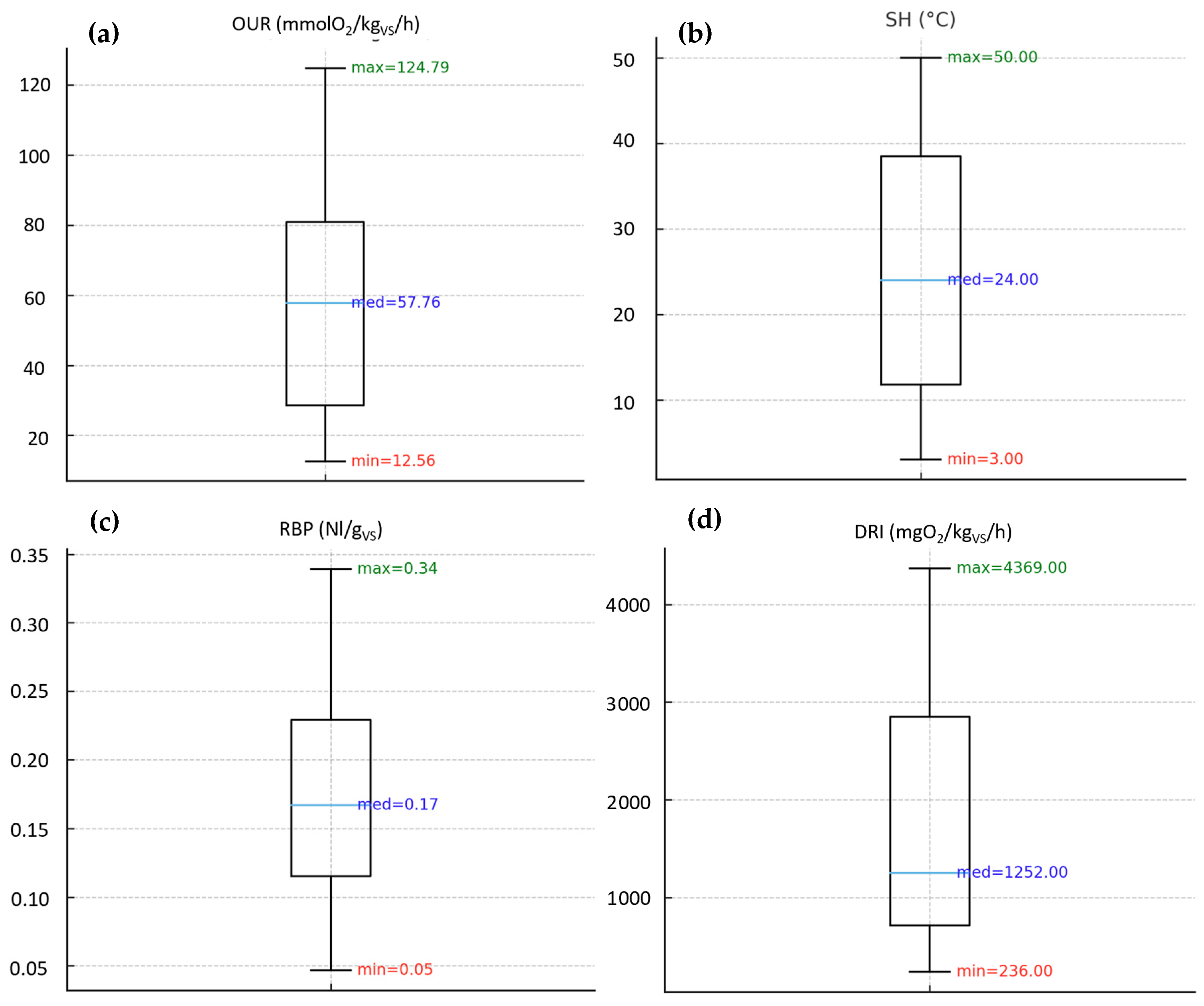

3.1.2. Biological Stability Indices on Digestate Samples

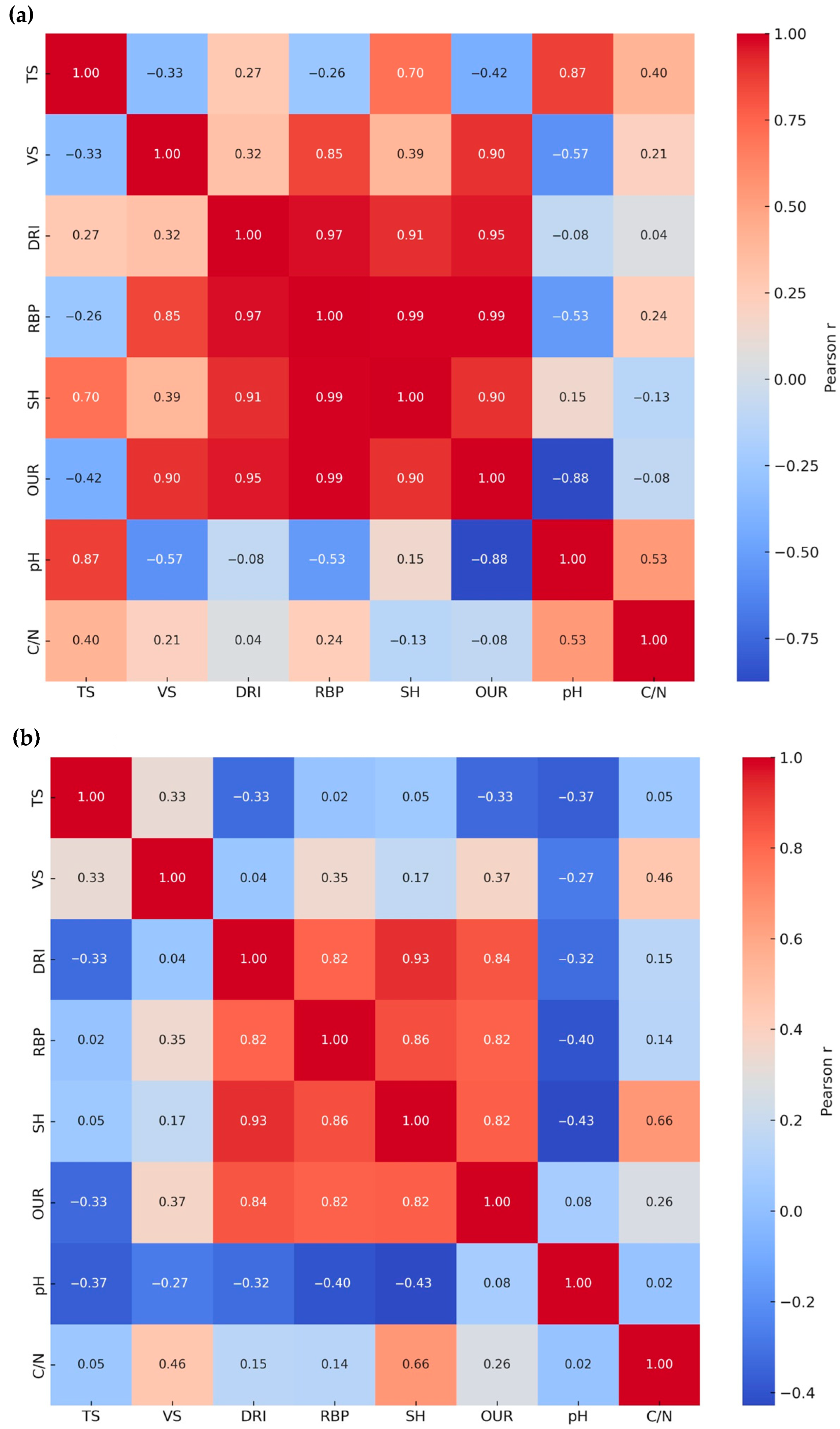

3.2. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient r

3.3. Second-Order Polynomial Regression Predictive Model

3.3.1. Overview of Predictive Model Equations

3.3.2. Relationship Between RBP, SH, and OUR (Compost Dataset)

3.3.3. Relationship Between RBP, SH, and OUR (Digestate Dataset)

3.3.4. Relationship Between RBP, SH, and OUR (All Sample Dataset)

3.3.5. Relationship Between DRI, SH, and OUR

4. Conclusions

- Biological stability indices permitted under EU Regulation 2019/1009 are strongly correlated but not equivalent in terms of stability classification.

- DRI emerged as the most stringent aerobic index (probably due to methodological procedure, ensuring complete and continuous aeration of samples); whereas RBP appeared to be the least restrictive, particularly for digestate samples [13].

- Regression analysis demonstrated that different indices and thresholds may lead to inconsistent regulatory outcomes, despite similar trends in experimental data.

- The current flexibility in index selection under EU Regulation 2019/1009 may result in non-uniform stability assessments across facilities and Member States.

- Matrix-specific criteria and multi-level assessment strategies could improve harmonization and reduce misclassification risks.

- A regulatory framework integrating complementary indices may better support circular economy objectives and the safe agricultural use of compost and digestate [46].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATU | Allylthiourea |

| BOD | Biological Oxygen Demand |

| BMP | Biochemical (Residual) Methane Potential |

| BMP28 | BMP measured after 28 days |

| C/N | Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratio |

| CE | CE marking (EU conformity) |

| CMC | Component Material Category; CMC3 = Compost; CMC5 = Digestate other than fresh crop digestate |

| DM | Dry Matter |

| DRI | Dynamic Respirometric Index |

| DW | Dry Weight |

| EoW | End-of-Waste |

| EU | European Union |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

| Nl | Normal liters (standard conditions) |

| OC | Oxygen Consumption |

| OFMSW | Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste |

| OM | Organic Matter |

| OUR | Oxygen Uptake Rate |

| R2 | R-squared |

| RBP | Residual Biogas Potential |

| RBP28 | RBP measured after 28 days |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| S/I | Substrate-to-Inoculum Ratio |

| SH | Self-Heating (Dewar/Rottegrad) |

| TS | Total Solids |

| TVS | Total Volatile Solids |

| Vgas | Gas Volume |

| VS | Volatile Solids |

References

- Lin, L.; Xu, F.; Ge, X.; Li, Y. Improving the Sustainability of Organic Waste Management Practices in the Food-Energy-Water Nexus: A Comparative Review of Anaerobic Digestion and Composting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas-Méndez, M.Á.; Sosa-Martínez, J.D.; Castrillón-Duque, E.X.; Cossio-Carrillo, C.S.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Salmerón, I.; Montañez, J.; Morales-Oyervides, L. Waste Valorization Through Eco-Innovative Technologies and Yeast Conversion into High-Value Products. In Food Byproducts Management and Their Utilization; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. End-of-Waste Criteria for Biodegradable Waste Subjected to Biological Treatment (Compost & Digestate): Technical Proposals; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pajura, R. Composting Municipal Solid Waste and Animal Manure in Response to the Current Fertilizer Crisis—A Recent Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Moustakas, K. Anaerobic Digestate Management for Carbon Neutrality and Fertilizer Use: A Review of Current Practices and Future Opportunities. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 180, 106991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambone, F.; Genevini, P.; D’Imporzano, G.; Adani, F. Assessing Amendment Properties of Digestate by Studying the Organic Matter Composition and the Degree of Biological Stability during the Anaerobic Digestion of the Organic Fraction of MSW. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3140–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alburquerque, J.A.; de la Fuente, C.; Bernal, M.P. Chemical Properties of Anaerobic Digestates Affecting C and N Dynamics in Amended Soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 160, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (Eu) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019; Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection Between Economy, Society and the Environment Updated Bioeconomy Strategy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, S.; Ali, M.H.; Samal, K. Assessment of Compost Maturity-Stability Indices and Recent Development of Composting Bin. Energy Nexus 2022, 6, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamolinara, B.; Pérez-Martínez, A.; Guardado-Yordi, E.; Guillén Fiallos, C.; Diéguez-Santana, K.; Ruiz-Mercado, G.J. Anaerobic Digestate Management, Environmental Impacts, and Techno-Economic Challenges. Waste Manag. 2022, 140, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecorini, I.; Peruzzi, E.; Albini, E.; Doni, S.; Macci, C.; Masciandaro, G.; Iannelli, R. Evaluation of MSW Compost and Digestate Mixtures for a Circular Economy Application. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitti, A.; Elshafie, H.S.; Logozzo, G.; Marzario, S.; Scopa, A.; Camele, I.; Nuzzaci, M. Physico-Chemical Characterization and Biological Activities of a Digestate and a More Stabilized Digestate-Derived Compost from Agro-Waste. Plants 2021, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Ocaña, E.R.; Torres-Lozada, P.; Marmolejo-Rebellon, L.F.; Hoyos, L.V.; Gonzales, S.; Barrena, R.; Komilis, D.; Sanchez, A. Stability and Maturity of Biowaste Composts Derived by Small Municipalities: Correlation among Physical, Chemical and Biological Indices. Waste Manag. 2015, 44, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Decision (EU) 2015/ 2099 of 18 November 2015 Establishing the Ecological Criteria for the Award of the EU Ecolabel for Growing Media, Soil Improvers and Mulch (Notified under Document C(2015) 7891); Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Government. Decreto Legislativo 29 Aprile 2010, n. 75; Italian Council of Ministers: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, M.; Foster, P. Comprehensive Evaluation and Development of Irish Compost and Digestate Standards for Heavy Metals, Stability and Phytotoxicity. Environments 2023, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Domínguez, D.; Guilayn, F.; Patureau, D.; Jimenez, J. Characterising the Stability of the Organic Matter during Anaerobic Digestion: A Selective Review on the Major Spectroscopic Techniques. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 21, 691–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.; Pecorini, I.; Paoli, P.; Iannelli, R. Plug-Flow Reactor for Volatile Fatty Acid Production from the Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste: Influence of Organic Loading Rate. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ochoa, F.; Gomez, E.; Santos, V.E.; Merchuk, J.C. Oxygen Uptake Rate in Microbial Processes: An Overview. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010, 49, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, W.; Longhurst, P.; Jiang, Y. Shortening the Standard Testing Time for Residual Biogas Potential (RBP) Tests Using Biogas Yield Models and Substrate Physicochemical Characteristics. Processes 2023, 11, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Frunzo, L.; Liotta, F.; Panico, A.; Pirozzi, F. Bio-Methane Potential Tests to Measure the Biogas Production from the Digestion and Co-Digestion of Complex Organic Substrates. Open Environ. Eng. J. 2012, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adani, F.; Ubbiali, C.; Generini, P. The Determination of Biological Stability of Composts Using the Dynamic Respiration Index: The Results of Experience after Two Years. Waste Manag. 2006, 26, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglia, B.; Tambone, F.; Genevini, P.L.; Adani, F. Respiration Index Determination: Dynamic and Statistic Approaches. Compost. Sci. Util. 2000, 8, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adani, F.; Confalonieri, R.; Tambone, F. Dynamic Respiration Index as a Descriptor of the Biological Stability of Organic Wastes. J. Environ. Qual. 2004, 33, 1866–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglia, B.; Acutis, M.; Adani, F. Precision Determination for the Dynamic Respirometric Index (DRI) Method Used for Biological Stability Evaluation on Municipal Solid Waste and Derived Products. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baffi, C.; Dell’Abate, M.T.; Nassisi, A.; Silva, S.; Benedetti, A.; Genevini, P.L.; Adani, F. Determination of Biological Stability in Compost: A Comparison of Methodologies. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena, R.; d’Imporzano, G.; Ponsá, S.; Gea, T.; Artola, A.; Vázquez, F.; Sánchez, A.; Adani, F. In Search of a Reliable Technique for the Determination of the Biological Stability of the Organic Matter in the Mechanical-Biological Treated Waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrczak, A.; Suchowska-Kisielewicz, M. A Comparison of Waste Stability Indices for Mechanical–Biological Waste Treatment and Composting Plants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, W.F.; Evans, E.; Droffner, M.L.; Brinton, R.B.. A Standardized Dewar Test for Evaluation of Compost Self-Heating. Biocycle 1995, 36, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- UNI EN 16087-2:2011; Soil Improvers and Growing Media—Determination of the Aerobic Biological Activity—Part 2: Self Heating Test for Compost. UNI Ente Italiano di Normazione: Milan, Italy, 2011.

- EN 16087-1:2020; Soil Improvers and Growing Media—Determination of Aerobic Biological Activity—Part 1: Oxygen Uptake Rate (OUR). UNI Ente Italiano di Normazione: Milan, Italy, 2020.

- Albini, E.; Pecorini, I.; Ferrara, G. Improvement of Digestate Stability Using Dark Fermentation and Anaerobic Digestion Processes. Energies 2019, 12, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI 11184:2025; Waste and Refuse Derived Fuels—Determination of Biological Stability by Dinamic Respirometric Index. UNI Ente Italiano di Normazione: Milan, Italy, 2025.

- Angelidaki, I.; Alves, M.; Bolzonella, D.; Borzacconi, L.; Campos, J.L.; Guwy, A.J.; Kalyuzhnyi, S.; Jenicek, P.; Van Lier, J.B. Defining the Biomethane Potential (BMP) of Solid Organic Wastes and Energy Crops: A Proposed Protocol for Batch Assays. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI/TS 11703:2018; Method for the Assessment of Potential Production of Methane from Anaerobic Digestion in Wet Conditions—Matrix into Foodstuffs. UNI Ente Italiano di Normazione: Milan, Italy, 2018.

- Patten, M.L. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient. In Understanding Research Methods; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Benesty, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Cohen, I. Pearson Correlation Coefficient. In Noise Reduction in Speech Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ratner, B. The Correlation Coefficient: Its Values Range between +1/−1, or Do They? J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2009, 17, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasciucco, F.; Pasciucco, E.; Castagnoli, A.; Iannelli, R.; Pecorini, I. Comparing the Effects of Al-Based Coagulants in Waste Activated Sludge Anaerobic Digestion: Methane Yield, Kinetics and Sludge Implications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotem, A.; Toner, M.; Tompkins, R.G.; Yarmush, M.L. Oxygen Uptake Rates in Cultured Rat Hepatocytes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1992, 40, 1286–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antognoni, S.; Ragazzi, M.; Rada, E.C. Biogas Potential of OFMSW through an Indirect Method. Int. J. Environ. Resour. 2013, 2, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, G.; Frunzo, L.; Panico, A.; Pirozzi, F. Model Calibration and Validation for OFMSW and Sewage Sludge Co-Digestion Reactors. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2527–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, A.; Conte, A.; Belgiorno, V.; Siciliano, A.; Guida, M. The Evolution of Compost Stability and Maturity during the Full-Scale Treatment of the Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradelo, R.; Moldes, A.B.; Prieto, B.; Sandu, R.-G.; Barral, M.T. Can Stability and Maturity Be Evaluated in Finished Composts from Different Sources? Compos. Sci. Util. 2010, 18, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, D.; Cristoforetti, A.; Zanzotti, R.; Bertoldi, D.; Dellai, N.; Silvestri, S. Matured Manure and Compost from the Organic Fraction of Solid Waste Digestate Application in Intensive Apple Orchards. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhylina, M.; Shishkin, A.; Miroshnichenko, D.; Sterna, V.; Ozolins, J.; Ansone-Bertina, L.; Klavins, M.; Goel, G.; Goel, S. Granulation and Pyrolysis of Agricultural Residues for an Enhanced Circular Economy. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sanz-Garrido, C.; Revuelta-Aramburu, M.; Santos-Montes, A.M.; Morales-Polo, C. A Review on Anaerobic Digestate as a Biofertilizer: Characteristics, Production, and Environmental Impacts from a Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature Rise Above Ambient in C | Official Class of Stability | Descriptors of Class or Group | Major Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–10° | V | Very stable, well-aged compost | Finished compost |

| 10–20° | IV | Moderately stable; curing compost | |

| 20–30° | III | Material still decomposing; active compost | Active compost |

| 30–40° | II | Immature, young, or very active compost | |

| 40–50° (or more) | I | Fresh, raw compost, just-mixed ingredients | Fresh compost |

| TS (%) | VS (%) | pH | C/N | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Av. | Min | Max | Av. | Min | Max | Av. | Min | Max | Av. | |

| Digestate | 1.44 | 88.9 | 35.5 | 47.0 | 91.0 | 66.0 | 4.5 | 8.7 | 7.3 | 6.0 | 21.5 | 11.4 |

| Compost | 9.6 | 92.7 | 70.8 | 29.0 | 87.1 | 49.3 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 7.4 | 12.0 | 15.9 | 13.7 |

| Dataset | Target Index | Equation | R2 | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compost | RBP | RBP = −0.0852 + 0.0018·OUR + 0.0104·SH + −0.0000·OUR2 + −0.0002·SH2 + 0.0000·OUR·SH | 0.96 | 0.038 |

| Compost | DRI | DRI = −223.3858 + 21.4709·OUR + 45.2233·SH + −0.0817·OUR2 + −0.7418·SH2 + 0.4477·OUR·SH | 0.97 | 257.85 |

| Digestate | RBP | RBP = 0.0598 + 0.0026·OUR + −0.0003·SH + 0.0000·OUR2 + 0.0002·SH2 + −0.0002·OUR·SH | 0.60 | 0.052 |

| Digestate | DRI | DRI = −173.9605 + 28.1243·OUR + 28.3748·SH + 0.0282·OUR2 + 0.9664·SH2 + −0.6159·OUR·SH | 0.95 | 266.32 |

| All sample | RBP | RBP = 0.0295 + 0.0005·OUR + 0.0046·SH + −0.0000·OUR2 + −0.0001·SH2 + 0.0000·OUR·SH | 0.84 | 0.065 |

| All sample | DRI | DRI = −57.9241 + 19.7859·OUR + 32.0990·SH + −0.0182·OUR2 + 0.1918·SH2 + 0.0046·OUR·SH | 0.96 | 299.58 |

| Dataset | OUR Min (mmol O2/kgVS/h) | OUR Max (mmol O2/kgVS/h) | SH Min (°C) | SH Max (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compost | 12.6 | 42.7 | 3.0 | 17.5 |

| Digestate | 13.1 | 35.3 | 5.7 | 20.2 |

| All sample | 12.6 | 44.1 | 3.0 | 19.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pecorini, I.; Pasciucco, F.; Palmieri, R.; Panico, A. Assessing the Suitability of Digestate and Compost as Organic Fertilizers: A Comparison of Different Biological Stability Indices for Sustainable Development in Agriculture. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031196

Pecorini I, Pasciucco F, Palmieri R, Panico A. Assessing the Suitability of Digestate and Compost as Organic Fertilizers: A Comparison of Different Biological Stability Indices for Sustainable Development in Agriculture. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031196

Chicago/Turabian StylePecorini, Isabella, Francesco Pasciucco, Roberta Palmieri, and Antonio Panico. 2026. "Assessing the Suitability of Digestate and Compost as Organic Fertilizers: A Comparison of Different Biological Stability Indices for Sustainable Development in Agriculture" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031196

APA StylePecorini, I., Pasciucco, F., Palmieri, R., & Panico, A. (2026). Assessing the Suitability of Digestate and Compost as Organic Fertilizers: A Comparison of Different Biological Stability Indices for Sustainable Development in Agriculture. Sustainability, 18(3), 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031196