Abstract

The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into medical services in Saudi Arabia offers a substantial opportunity. Despite the increasing integration of AI techniques such as machine learning, natural language processing, and predictive analytics, there persists an issue in the thorough comprehension of their applications, advantages, and issues within the Saudi healthcare framework. This study aims to perform a thorough systematic literature review (SLR) to assess the current status of AI in Saudi healthcare, determine its alignment with Vision 2030, and suggest practical recommendations for future research and policy. In accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology, 699 studies were initially obtained from electronic databases, with 24 studies selected after the application of established inclusion and exclusion criteria. The results indicated that AI has been effectively utilised in disease prediction, diagnosis, therapy optimisation, patient monitoring, and resource allocation, resulting in notable advancements in diagnostic accuracy, operational efficiency, and patient outcomes. Nonetheless, limitations to adoption, such as ethical issues, legislative complexities, data protection issues, and shortages in worker skills, were also recognised. This review emphasises the necessity for strong ethical frameworks, regulatory control, and capacity-building efforts to guarantee the responsible and fair implementation of AI in healthcare. Recommendations encompass the creation of national AI ethics and governance frameworks, investment in AI education and training initiatives, and the formulation of modular AI solutions to guarantee scalability and cost-effectiveness. This breakthrough enables Saudi Arabia to realise its Vision 2030 objectives, establishing the Kingdom as a global leader in AI-driven healthcare innovation.

1. Introduction

In over a decade, medical care in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has experienced swift change. This change is due to population increase, changes in epidemiology, and governmental advancement programmes like Vision 2030 [1]. The KSA healthcare systems, offering complementary healthcare services to citizens and residents, have traditionally encountered issues concerning the affordability of services, stressed public hospitals, a high incidence of chronic ailments, and a deficiency of specialised medical practitioners [2,3]. Moreover, medical facilities have faced challenges related to geographical inequities, suboptimal distribution of resources, prolonged patient wait times, and disjointed healthcare information systems [4]. The systemic challenges have underscored the necessity for an evolutionary shift regarding streamlined, effective, and highly advanced medical solutions such as AI-powered diagnostic tools and electronic health record integration, which guarantee improved health outcomes, administrative optimisation, and sustainability in service delivery.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to computer systems capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, and problem-solving [5]. Artificial intelligence encompasses numerous fields, including machine learning (ML), natural language processing (NLP) [6,7,8], computer vision [9], and robotics [10,11]. These innovations can evaluate extensive amounts of sophisticated medical data, identify trends, forecast results, and assist physicians in the detection of diseases, formulating treatment plans, and overseeing healthcare activities [12,13]. Artificial intelligence is crucial in improving health management through statistical modelling, tailored care, and effective resource allocation. In Saudi Arabia, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in health management encompass disease prediction utilising machine learning and deep learning models for early detection and mitigation, diagnosis and treatment optimisation through AI-enhanced examinations and tailored treatment strategies, patient monitoring and involvement via automated wearable devices and mobile apps [14]. These technologies offer continuous health monitoring and personalised recommendations, resource allocation and workflow optimisation through machine learning models that eliminate wait times and enhance overall healthcare efficiency. These applications illustrate the revolutionary capacity of AI in tackling significant health problems in the KSA. Recent changes in the KSA healthcare systems encompass the implementation of Vision 2030 projects, the improvements of healthcare infrastructure, improved utilisation of digital health technology, and strategies to enhance accessibility and quality of care.

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 has emphasised the emergence of digital health, positioning AI as crucial to advancements in healthcare [15]. The formation of the Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority (SDAIA) in 2019 and the initiation of the National Strategy for Data and AI (NSDAI) demonstrate the nation’s dedication to the incorporation of AI into various fields, including healthcare [16]. The Ministry of Health (MoH), in partnership with both domestic and foreign entities, has launched various AI-driven initiatives, including virtual healthcare consultations, AI-enhanced COVID-19 monitoring, and intelligent triage systems [17,18]. Institutions like King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre (KFSHRC) and King Abdullah Medical City have adopted AI-driven technologies for radiography, cancer therapy, intensive care, and hospital management systems [19]. Furthermore, AI algorithms are being investigated for diabetic retinopathy screening, breast cancer diagnosis, medical records automation, and intelligent mobile health applications designed for Saudi patients [20]. Furthermore, AI has been extensively utilised in clinical image analysis, predictive analytics, personalised medicine, robotic-assisted surgery, and the automation of managerial tasks [21,22]. Global data indicates that AI may enhance diagnostic precision, minimise human errors, decrease expenses, and boost consumer satisfaction. Recent advancements in 3D graph deep learning and non-contact gesture recognition, demonstrated by studies on hand segmentation utilising laser point clouds [23] and 3D graph techniques for contactless rehabilitation [24], highlight promising technical avenues for scalable, remote rehabilitation. While primarily assessed in laboratory environments, these methodologies possess significant implications for sustainable health management in Saudi Arabia by facilitating remote care for ageing demographics and mitigating infection risks in post-epidemic contexts; nevertheless, clinical validation and local customisation are essential before extensive implementation.

Few reviews and surveys have been conducted on this study’s domain. For instance, habbash, Saleh Almansour [25] examined the role of artificial intelligence in shaping the healthcare sector of Saudi Arabia. The researchers opined that the powers of AI can be harnessed to enhance disease diagnosis and improve health-related recommendations. The investigation revealed that machine learning algorithms can be employed in formulating models that predict the outbreak of a pandemic, enhance the treatment of ailments, improve prediction precision, and pave the way for personalised medication. Nonetheless, the investigation emphasised the need for a partnership between the healthcare sector, the technology sector, and lawmakers to propagate practices that stimulate the adoption of artificial intelligence in the health sector. Conversely, the research by Al-Jehani, Hawsawi [26] further exposed the potential of artificial intelligence to boost the GDP of Saudi Arabia by the year 2030. The researchers expounded on the country’s healthcare technologies, which have led to the development of unique AI techniques for the kingdom. The investigators explained the adoption of frameworks for a smart city that utilised robots to enhance productivity and efficiency. The research further examined the global contribution of AI in curbing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many of these reviews fail to thoroughly examine the complex issues associated with AI deployment in Saudi Arabia, such as socio-cultural resistance, legal uncertainties, privacy concerns, ethical issues, and geographic variations in technological resources. Additionally, there is insufficient discourse on the compatibility of AI initiatives with Saudi national policy frameworks and educational preparedness for the incorporation of AI into medical environments. This review seeks to address these deficiencies identified from the previous reviews by offering a comprehensive examination of the role of AI in improving health management in Saudi Arabia. It differentiates itself by analysing both clinical and administrative applications of AI, the national digital health policy framework, issues in implementation, and new technologies. This review is motivated by the pressing necessity to comprehend the impacts of AI on health administration processes in Saudi Arabia and to assist stakeholders in enhancing AI implementation to elevate healthcare quality, efficiency, and equity.

This systematic literature analysis seeks to thoroughly analyse the current academic research about the implementation of artificial intelligence in the healthcare system in Saudi Arabia. The analysis specifically examines the deployment of AI technologies in health management and service delivery, evaluates their stated efficiency, and identifies critical challenges and barriers affecting their acceptance. The study aims to assess the degree of integration of AI-driven healthcare efforts within national health policies, specifically in accordance with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, and to highlight practical avenues for further research and policy creation. This review employs a systematic literature review (SLR) technique in accordance with the standards established by Kitchenham and Charters [27]. Peer-reviewed articles published from 2021 to 2025 that critically assess AI applications within the Saudi healthcare setting were discovered and assessed across various dimensions, including application areas, implementation outcomes, adoption barriers, and future prospects. After an exhaustive search of nine academic bibliographic databases, twenty-four (24) relevant publications fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were chosen for in-depth study.

This review paper’s principal contributions are enumerated below.

- This research integrates diverse knowledge regarding AI applications across multiple healthcare sectors in Saudi Arabia, encompassing disease prediction, diagnosis, treatment optimisation, patient monitoring, and resource allocation.

- The study assesses the alignment of AI-powered healthcare programmes with the main goals of Saudi Vision 2030, specifically on the improvement of healthcare quality, availability, and sustainable development.

- The paper offers actionable recommendations for subsequent research and policy, including the creation of national AI ethics frameworks, investment in workforce training, and the formulation of modular AI solutions to guarantee scalability and cost-effectiveness.

- This review thoroughly identifies and examines the barriers that impede the effective application of AI in Saudi Arabia’s medical sector.

- This review highlights an agenda for forthcoming advancements in AI-powered health management in Saudi Arabia, based on the identified challenges and potential.

The following is the remainder of this systematic review: The methods and processes of the SLR, including the research objectives, search strategy, and selection criteria, are explained in Section 2. The results of the research are covered in Section 3. Section 4 presents research on potential future directions for AI research and development within the Saudi healthcare system. Limitation of the study is presented in Section 5, whereas the study is finally concluded in Section 6.

2. Research Method

The SLR is a technique for locating, assessing, and interpreting existing research literature that is appropriate to a certain study topic or needed to address a specific research question [27]. This SLR’s objective is to identify the research gaps in the current literature, which will aid in future investigations. To ensure the rigour, transparency, and reproducibility of the review process, this SLR adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) best practices [27]. The main steps of the method are: formulating research questions, developing a search strategy, applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, and systematically extracting and synthesising data. The steps taken from the adopted review method are elaborated as follows:

2.1. Research Question

After identifying the need for a review, the next step is to define research questions. This section establishes the research questions and their corresponding objectives that will be addressed in the course of this review. Kitchenham and Brereton [28] assert that research questions are intended to delineate the issues under investigation and the objectives of the study’s methodology. This systematic research aims to examine the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in improving health management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. To fulfil the requirement for systematic literature research and achieve the research purpose, the study particularly addressed the following research questions:

- RQ1:

- What are the current applications of AI in health management within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and how have these applications impacted healthcare delivery and patient outcomes?

- RQ2:

- How does the integration of AI in health management align with the Saudi Vision 2030 goals, particularly in terms of improving healthcare services and achieving sustainable development?

- RQ3:

- What are the ethical, legal, and regulatory considerations associated with the use of AI in health management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and how are these considerations being managed?

- RQ4:

- What are the key performance metrics used to evaluate the effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in enhancing healthcare management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia?

- RQ5:

- What are the challenges and barriers to the adoption and implementation of AI technologies in health management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and how can these challenges be addressed?

2.2. Search Strategy

We employed three sequential processes to locate relevant articles: defining keywords, formulating a search strategy, and selecting data sources. The content of the study topic was utilised to identify keywords and build a suitable search strategy. Subsequent to the initial search, the keywords were enhanced. Multiple iterations of searches were conducted, and specific phrases were merged. This analysis incorporated articles published from 2019 to 2025. This systematic literature review utilised a rigorous search methodology to identify significant scholarly works regarding the role of artificial intelligence in improving health management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia across academic databases. In this context, nine research databases, including Science Direct, MDPI, PubMed, Springer, Wiley Online, Taylor and Francis, IEEE Xplore, ProQuest, and Google Scholar, were thoroughly searched for appropriate articles as shown in Table 1. The search technique began with a comprehensive approach, employing keywords to locate publications on “The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Health Management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.” Synonyms and search terms were generated based on relevant research, employing artificial intelligence and health management. The Search Query (SQ) encompassed all of the following phrases and synonyms, as illustrated below:

Query-1 = “Artificial Intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “Natural language processing” OR “NLP” OR “AI” OR “DL” OR “Predictive analytics” OR “Machine Intelligence” OR “Computational Intelligence” OR “Intelligent Systems” OR “Intelligent Automation.”

Query-2 = “Healthcare management” OR “clinical management” OR “Healthcare administrations” OR “clinical administrations” OR “Healthcare Operations”, OR “Health Service Delivery” OR “Healthcare Governance” OR “Patient Care Management.”

Query-3 = “Saudi Arabia” OR “SA” OR “The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia” OR “KSA” OR “Saudi” OR “Saudi Peninsula” OR “Riyadh-based Nation.”

SQ = Query_1 AND Query_2 AND Query_3

The search string searches were utilised on the chosen database to extract the academic literature. Literature was thoroughly chosen from publications exclusively in the English language, resulting in a total of 699 research articles identified by the search approach.

Table 1.

Study selection process.

Table 1.

Study selection process.

| Bibliographical Database | Initial Search Results | Selected Papers |

|---|---|---|

| IEEE Xplorer | 86 | 2 |

| Science Direct | 112 | 4 |

| Wiley Online | 83 | 1 |

| Springer | 97 | 1 |

| Google Scholar | 66 | 2 |

| Taylors and Francis | 56 | 1 |

| MDPI | 101 | 8 |

| ProQuest | 36 | 1 |

| PubMed | 42 | 4 |

| Snowballing | 20 | 0 |

| Total | 699 | 24 |

2.3. Articles Selection Criteria

Selection criteria for identifying suitable papers are established in this section. These criteria set a standard for assessing extracted articles to ascertain their inclusion in the study. To enhance the article’s selection process, the study protocol delineates the inclusion criteria, which clearly define the scope of the review questions. The search criteria encompass the collection of suitable data from conferences and peer-reviewed research articles published in English within nine recognised academic databases: Science Direct, MDPI, PubMed, Springer, Wiley Online, Taylor and Francis, IEEE Xplore, ProQuest, and Google Scholar, published in the past seven years (2019 to 2025). The study must also satisfy the minimum quality threshold criteria specified in the subsequent portion of the quality assessment. This study employed a systematic screening procedure that methodically directed the literature choice procedure. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were designed to ensure that only publications related to the established research questions were selected. Table 2 delineates the employed inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Selection Criteria.

2.4. Screening Process and Results

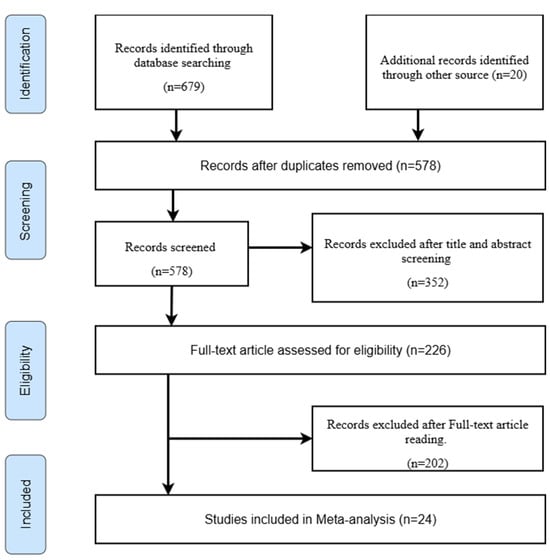

Using the chosen search approach, 699 articles from various academic databases were found in the first search. With careful attention to the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria, these publications were reviewed step-by-step using the PRISMA methodology for performing systematic literature reviews. The number of papers obtained was reduced to 578 after duplicate items were eliminated. After the initial 578 articles were subjected to screening based on the predefined exclusion criteria, including reading of titles and abstracts, a total of 352 articles were excluded. This resulted in 226 articles remaining for full-text assessment. Next, a full-text screening was carried out, and 202 articles were excluded after reading the articles in full text. 24 relevant studies were found when the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria were used. Ultimately, 24 articles were chosen based on the standards for quality evaluation outlined in Section 2.5. The screening procedure utilising the PRISMA diagram is depicted in Figure 1 (Supplementary Materials).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

2.5. Quality Assessment

A set of criteria was established and applied to evaluate the quality and applicability of each chosen article for the systematic literature review [27]. The quality of the publications from the previous phase is assessed using quality assessment criteria. A checklist for quality assessment was adapted from Papamitsiou and Economides [29] guideline. Table 3 presents an outline for conducting quality evaluation for every study selected for the SLR. Consequently, the table indicates the suitability of the investigation and can produce findings that can expand the research’s scope. The studies that were selected underwent a thorough quality evaluation procedure to make sure they matched the study’s goals, methodological reliability, and applicability in order to improve the quality, reliability, and credibility of the results. Consequently, the chosen papers were assessed using a set of predetermined quality evaluation criteria. The QA criteria used are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quality Assessment Question.

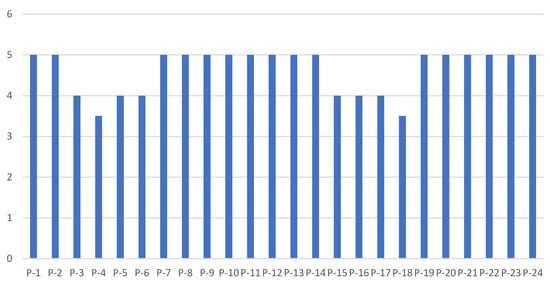

A three-point Likert scale with different interpretations is used to rate each item on the checklist. A summary of the quality of the included studies has been compiled using the obtained results. The research questions RQ1 through RQ5 presented in this extensive investigation have been addressed using the results of the evaluation of articles related to QA1 through QA5. The following is the definition of the paper scoring system: Partial = 0.5, No = 0, and Yes = 1. If the paper satisfies the requirements, it receives a score of 1. If the article just partially satisfies the quality standard, it receives a score of 0.5. If the article does not meet any of the quality standards, it receives a score of 0. As a result, the best paper will be rated at five, while the worst will be rated at zero. However, if the total score is less than 3, the work is rejected, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Visualising the Quality Assessment Results.

2.6. Data Extraction and Synthesis

After 24 papers were chosen for synthesis, data extraction was performed to wrap up the process. The method used for extracting data was developed based on a basic research topic. Each of the 24 selected papers was thoroughly analysed in order to develop a template for collecting information during the data extraction phase. The purpose of this form was to collect the essential information needed to fulfil the study’s objectives, which are detailed in Table 4. To ensure consistency, data were collected from a sample of selected papers using the Barbara [28] guideline form. The EndNote citation manager was used to arrange the “paper title, authors, publication date, Digital Object Identifier (DOI), and publication specifics” in an organised manner. After that, important information was taken from the papers in line with the primary study classification. An Excel application was used by the authors to save the collected data. To collect the information required during the analysis, eight columns in an Excel spreadsheet were utilised: Paper ID, References, AI Application, Architecture, Input, Dataset, Metrics, Key Findings, Challenges and Barriers, and Databases. Data synthesis attempts to give a thorough summary of past research by condensing the material acquired during the information-gathering stage, giving new researchers insights.

Table 4.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Health Management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Review, Challenges, and Future Directions.

3. Findings and Discussions

This part describes the findings of the systematic literature review derived from the analysis of the chosen primary studies, initially presenting the framework of the selected studies as illustrated in Table 4, followed by the outcomes corresponding to each research question of the SLR. From an initial total of 699 papers retrieved from the databases, 24 were selected for further analysis following the application of research selection criteria and quality assessment of the papers. Table 4 enumerates these 24 papers together with details regarding their authors, article classifications, and databases. Table 1 displays the number of papers identified using a certain data source. A category for snowballing data sources was established by integrating backward and forward snowballing methods. The subsequent subsections address each of the five research questions outlined in Section 2.

3.1. What Are the Current Applications of AI in Health Management Within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and How Have These Applications Impacted Healthcare Delivery and Patient Outcomes? (RQ1)

The findings from the current application of AI in health management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia with respect to research question 1 indicate a substantial number of AI applications employed in health management within KSA. This study revealed ten (10) distinct applications in healthcare administration. Table 4 illustrates the applications utilised in the selected papers, indicating that each study employed one or more AI applications. AI is currently utilised in health management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) across multiple healthcare areas, including disease prediction, diagnosis, therapy optimisation, patient monitoring, and resource allocation. As outlined in [54], AI techniques such as predictive modelling, automated messaging, and data-driven guidance not only enhance exercise programme delivery but also support broader health management goals by improving personalised care, promoting adherence, and enabling more effective monitoring and intervention strategies. These applications have profoundly influenced healthcare delivery and patient outcomes by enhancing the efficiency, accuracy, and accessibility of healthcare services. This section presents a comprehensive examination of these applications and their effects, substantiated by references from the selected papers.

3.1.1. Medical Imaging and Diagnosis

Artificial Intelligence (AI), characterised by the ability of computers and applications to replicate human intelligence, including learning, reasoning, and making decisions, is swiftly revolutionising health services worldwide. Artificial intelligence has transformed medical imaging and diagnostics by facilitating quicker, more precise, and effective identification of diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and neurological problems [55]. Artificial intelligence in healthcare, particularly deep learning, may analyse medical images and detect conditions such as tumours, bone fractures, and lesions, among others. The application of AI in diagnosis facilitates physicians in obtaining accurate diagnoses from patient data, laboratory tests, and imaging, thereby reducing the likelihood of erroneous diagnoses and overlooking significant treatment options [13] Several selected studies have applied AI in medical imaging and diagnosis. For instance, Dahan, Alroobaea [33] created an IoMT-based e-healthcare system utilising a hybrid ResNet-18 + GoogleNet (HRGC) model, attaining 99.69% accuracy in vital sign classification and surpassing conventional classifiers such as VGG16 and AlexNet. Furthermore, El-Sherif, Abouzid [51] demonstrated AI-assisted chest X-ray and symptom-based models for COVID-19 diagnosis, with an accuracy of 84% and an AUC of 0.82. These developments enhance diagnostic precision and alleviate the workload of healthcare personnel, facilitating early diagnosis and prompt therapies. Nonetheless, issues including limited sample sizes, data noise from sensors, and the necessity for empirical validation persist as significant areas requiring enhancement.

3.1.2. AI-Powered Virtual Health Assistants and Chatbots

AI-powered virtual health assistants and chatbots are revolutionising patient engagement and care delivery by offering accessible, personalised, and immediate support. The virtual health assistant and chatbot system automates critical patient contacts by addressing frequently asked questions, scheduling appointments, and delivering timely prescription notifications to enhance patient compliance [56]. Patients are independently guided and assisted in symptom assessment. Symptom checkers offer first guidance [57]. Only a limited number of the chosen papers have utilised the system in their research on AI applications in healthcare. For example, Rathee, Garg [31] devised a hybrid Generative AI framework (RLHF + ANP) for healthcare decision assistance, attaining 98.8% accuracy with reduced latency and overhead, rendering it a significant asset for disabled and elderly patients. Similarly, Al-Jehani, Hawsawi [26] emphasised the efficacy of the Sarah chatbot in enhancing patient engagement and compliance with treatment protocols, in accordance with the objectives of Saudi Vision 2030. Moreover, El-Sherif, Abouzid [51] illustrated the function of AI-driven chatbots in enhancing access to healthcare and mitigating exposure risks during the COVID-19 pandemic. These applications augment patient-centred treatment, alleviate administrative constraints, and boost accessibility, especially in underprivileged regions. Nonetheless, issues include noise in raw data, real-time adaptability, and the assurance of data privacy and security must be addressed.

3.1.3. Predictive Analysis and Patient Care

AI-driven predictive analysis is crucial in strengthening patient care through early disease identification, resource optimisation, and improved healthcare decision-making. In terms of resource allocation, one of the applications of AI in healthcare is predicting patient inflow at hospitals to optimise the distribution of human and other resources [58]. In the realm of risk management, machine learning algorithms assess the dangers patients might face, such as hospital readmission, the development of additional illnesses, and worsening of existing conditions, thereby facilitating the implementation of appropriate preventative measures [58]. Some selected studies have applied predictive analysis and patient care in the healthcare domain. AlMuhaideb, Alswailem [32] employed JRip and Hoeffding Tree models for predicting outpatient no-show appointments, attaining an accuracy of 77.1% and an AUC of 0.861, thereby identifying high-risk time frames for specific treatment. Similarly, Daghistani, Elshawi [43] demonstrated the effectiveness of Random Forest (RF) in predicting in-hospital length of stay (LOS) for cardiac patients, and the experimental analysis showed that the RF model attained 80% predictive accuracy and an AUROC of 0.94. Furthermore, Alkattan, Al-Zeer [45] demonstrated the efficiency of AI in the early prediction of Type 2 Diabetes. The authors tested and compared the predictive performance of RF and Logistic regression (LR) models. The comparative results showed that the RF surpassed the LR, attaining an AUROC of 0.944. These prediction models enhance patient outcomes, optimise healthcare resources, minimise expenses, and facilitate proactive care. Nonetheless, issues such as single-centre studies, class imbalance, and restricted generalisability persist as critical areas

3.1.4. Remote Monitoring and Telemedicine

Remote monitoring and telemedicine, facilitated by AI and IoT, are enhancing access to healthcare services, especially for patients in isolated or underserved regions. Wearable devices equipped with AI technology provide continuous health monitoring by detecting vital signs, diagnosing pathophysiological abnormalities, and alerting clinicians to take timely action. Artificial intelligence (AI) enhances the creation of telehealth services, diagnostic gadgets, patient condition tracking, and virtual consultations, hence optimising healthcare delivery to specific areas [59]. Some selected studies applied telemedicine and remote monitoring in healthcare settings in the KSA. For example, Qaffas, Hoque [39] built an IoT-driven machine learning system for predicting chronic diseases, specifically hypertension, obtaining an accuracy of 71.15% using support vector machines, thus illustrating the promise of IoT and big data analytics for early disease diagnosis. Dahan, Alroobaea [33] demonstrated an IoMT-based e-healthcare system for remote patient monitoring, with the HRGC model attaining 99.69% accuracy in vital sign classification. Furthermore, El-Sherif, Abouzid [51] emphasised the significance of artificial intelligence in telehealth and remote patient monitoring during the COVID-19 pandemic, enhancing access to healthcare and mitigating exposure hazards. These applications boost patient outcomes while improving healthcare accessibility and efficiency, in accordance with the objectives of Saudi Vision 2030. Nonetheless, obstacles such as limited sample sizes, interference in sensor data, and the necessity of protecting data privacy and security must be tackled to completely actualise their promise.

AI applications in medical imaging and diagnosis, virtual health assistants and chatbots, predictive analytics and patient care, as well as remote monitoring and telemedicine, have impacted healthcare delivery and enhanced patient outcomes in Saudi Arabia. For instance, these technologies facilitate early disease identification, tailored healthcare, and enhanced accessibility, in accordance with governmental objectives such as Vision 2030. These aforementioned studies illustrate the impact of AI in improving diagnostic precision, delivering personalised treatment, optimising resource distribution, and facilitating remote monitoring. Nonetheless, challenges including data constraints, integration intricacies, and privacy issues persist as vital domains for enhancement. Mitigating these challenges would augment the uptake and efficacy of AI in healthcare.

3.2. How Does the Integration of AI in Health Management Align with the Saudi Vision 2030 Goals, Particularly in Terms of Improving Healthcare Services and Achieving Sustainable Development? (RQ2)

The findings from the alignment of the integrations of AI in health management with the Saudi Vision 2030 show that there is an integration of AI into the healthcare domain in the KSA. The use of AI in health management strongly aligns with the goals of Saudi Vision 2030, especially with the enhancement of healthcare services and the attainment of sustainable development. This research question provides details descriptions of the alignment of the AI integration in healthcare with the Saudi Arabia 2030 vision.

Saudi Arabian healthcare has undergone a significant transformation as a result of support for the Vision 2030 goals, which prioritise patient-centred treatment and encourage technological advancement. In order to facilitate the implementation of innovative technologies like AI, telemedicine, and data analytics, Vision 2030 places a strong emphasis on modernising healthcare facilities. These technologies improve the effectiveness of therapy programmes, the accuracy of evaluations, and the efficiency of administrative procedures [60]. For example, the Kingdom has implemented Electronic Health Records (EHRs) as a result of programmes like the National Health Transformation Scheme, which have improved care coordination, decreased medical errors, and simplified patient administration. These advancements have guaranteed high-quality results while significantly improving healthcare efficiency.

Accessibility and fairness in medical treatment are also given top priority in Vision 2030. The government has made it easier for rural and isolated communities to receive medical treatments by growing telemedicine platforms like “Seha” and investing more in rural healthcare facilities [61]. This pledge supports Vision 2030’s objective of improving public well-being and lifespan by early detection and preventative treatment. In addition, the number of cases of chronic diseases has decreased, and the general well-being of citizens has improved as a result of public awareness campaigns and digital tools that enable people to take charge of their own health.

Artificial intelligence is crucial in achieving Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 goals, since it improves the accessibility, quality, and adoption of sophisticated technologies, especially within the healthcare domain. Utilising AI, Saudi Arabia can more effectively predict healthcare needs, enhance facilities utilisation, and support the sustainable expansion of healthcare outsourcing. AI-driven predictive analytics, illustrated by AlMuhaideb, Alswailem [32] in predicting outpatient no-shows, facilitate improved resource allocation and operational efficiency. This corresponds with Vision 2030’s focus on effective healthcare provision and sustainable advancement. Moreover, AI’s contribution to enhancing the efficiency of drug discovery, genomics, and personalised treatment facilitates the establishment of novel healthcare research and development centres in Saudi Arabia, thereby reinforcing Vision 2030’s objective of positioning Saudi Arabia as the world’s leader in technological advancement and innovation.

AI enhances customer satisfaction by delivering individualised care and enhancing the quality of medical services. For instance, Rathee, Garg [31] devised a hybrid Generative AI framework (RLHF + ANP) for accessible healthcare decision support, which attained 98.8% accuracy with reduced latency and overhead. This system offers rapidly tailored services for disabled and older adults, in accordance with Vision 2030’s objective of enhancing the quality of life for all inhabitants. AI-driven virtual health assistance systems and chatbots, exemplified by the Sarah chatbot discussed by Al-Jehani, Hawsawi [26], improve consumer engagement and compliance with medical procedures, guaranteeing timely and individualised care for patients. These types of applications enhance patient experiences and support the operational objectives of healthcare systems, particularly during large-scale events like Hajj, where AI-powered monitoring and decision-making devices facilitate effective coordination and protection.

The incorporation of AI in healthcare enhances financial stability through process automation, increased diagnostic precision, and decreased operational expenses. For example, AI-driven diagnostic instruments, such as the hybrid ResNet-18 + GoogleNet (HRGC) model created by Dahan, Alroobaea [33], attain 99.69% accuracy in vital sign classification, thereby diminishing the probability of diagnostic inaccuracies and enhancing operational efficiency. This corresponds with Vision 2030’s objective of attaining financial stability in healthcare through job automation and cost reduction. Furthermore, AI’s impact on enhancing employees’ human resources via knowledge-based systems enhances the transformative objectives of Vision 2030. By providing healthcare workers with AI-driven tools and training, Saudi Arabia can augment the skills and competencies of its staff while ensuring that the healthcare industry remains creative and adaptive to the population’s requirements.

Ultimately, AI improves decision-making and policymaking in Saudi Arabia, facilitating the growth of innovative health systems that correspond with Vision 2030. AI-driven prediction analytics, demonstrated by Alkattan, Al-Zeer [45], for predicting Type 2 Diabetes, yield significant insights that guide public health policy and actions. These techniques augment the responsiveness of healthcare systems and strengthen their capacity to tackle growing challenges, including chronic diseases and infectious epidemics. Table 4, which provides the details of the data extractions from the selected studies, examines diverse healthcare applications that utilise AI to augment adaptation and advance innovative health systems in accordance with Vision 2030. Integrating AI into health management will enable Saudi Arabia to realise its Vision 2030 goals of enhancing medical services, ensuring sustainable growth, and establishing the Kingdom as a global leader in healthcare innovation. Nonetheless, issues such as data privacy, integration complexity, and the necessity for continual training and adaptation must be resolved to fully harness the potential of AI in attaining these goals.

3.2.1. Measurable Impact of AI on Vision 2030 Goals

The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into Saudi Arabia’s healthcare system might substantially advance the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 goals, especially in improving healthcare quality, efficiency, and accessibility. We have identified many measurable metrics to quantify this impact, which fit with the Vision 2030 aims. Initially, AI-driven diagnostic instruments and personalised medicine are expected to enhance the healthcare quality index by 25% by the year 2030, aligning with the Vision 2030 objectives. Research has shown that AI-augmented diagnostic systems can enhance diagnostic precision by as much as 15%, hence decreasing misdiagnosis rates and improving patient outcomes. Secondly, AI-driven triage systems and resource allocation models seek to minimise healthcare wait times by 30%, a primary objective identified in Vision 2030. Case studies, including the implementation of AI-driven COVID-19 monitoring systems, have demonstrated a 20% decrease in hospitalisation rates, directly aiding this objective. The integration of AI in virtual healthcare consultations and mobile health applications corresponds with the Vision 2030 goal of enhancing digital health usage by 50% by 2030. These technologies have facilitated remote patient monitoring and tailored care, especially in underprivileged areas, thus enhancing access to healthcare services. Moreover, AI-driven predictive analytics and therapy optimisation tools are anticipated to increase patient outcomes, aiding in the Vision 2030 objective of decreasing preventable mortality rates. AI algorithms for chronic illness management have demonstrated a 10% enhancement in treatment adherence and a 15% decrease in readmission rates. These quantifiable metrics illustrate the concrete influence of AI on Vision 2030 objectives and emphasise the necessity for ongoing investment in AI-driven healthcare advancements to fulfil the Kingdom’s long-term aims.

3.2.2. Interdisciplinary Integration of AI in Healthcare: Complementary Roles, Overlaps, and Sustainability Implications

The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into healthcare in Saudi Arabia has shown considerable promise in multiple areas, such as disease prediction, diagnosis, therapy optimisation, patient monitoring, and resource allocation. This section examines the interplay between several AI techniques, including machine learning (ML), natural language processing (NLP), and predictive analytics, in their capacity to either complement or contradict one another in solving complicated healthcare issues. For example, machine learning models could predict disease outbreaks or patient outcomes, and natural language processing technologies can analyse unstructured medical data (such as clinical notes and patient feedback) to improve decision-making [62]. Nonetheless, these tools may conflict in specific contexts, for instance, when a machine learning model predicts a high-risk patient outcome that contradicts an NLP-based sentiment analysis indicating patient satisfaction, underscoring the necessity for interdisciplinary strategies to resolve such inconsistencies [63]. Moreover, the applications of AI technologies frequently intersect, especially in domains like predictive analytics and personalised medicine, where both machine learning and natural language processing can be employed to analyse patient data for early disease identification. Comprehending these intersections is essential for developing integrated AI systems that optimise efficiency and precision, such as merging machine learning with natural language processing to improve diagnostic accuracy by utilising both structured and unstructured data sources [64]. The patterns of AI application in Saudi Arabia’s healthcare system have considerable implications for sustainability research, particularly regarding resource allocation (e.g., optimising hospital bed utilisation or minimising wait times), which directly aligns with the sustainability goals established in Vision 2030. The implementation of AI tools must also take into account their environmental implications, including energy usage and hardware demands, to ensure conformity with overarching environmental and social sustainability goals [65,66]. A multidisciplinary strategy is necessary to fully harness the potential of AI in healthcare, integrating various AI tools and techniques, such as the combination of computer vision for medical imaging and machine learning for predictive analytics, to improve diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning [67]. Future research should focus on establishing frameworks for interdisciplinary integration, examining the ethical and regulatory challenges of converging AI applications, and assessing the environmental and social sustainability of AI-driven healthcare solutions, emphasising energy efficiency and equitable access. The new discussion explains relationships among the literature, offering a more thorough comprehension of AI’s role in sustainable health management in Saudi Arabia by addressing these topics.

3.3. What Are the Ethical and Regulatory Considerations Associated with the Use of AI in Health Management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and How Are These Considerations Being Managed? (RQ3)

The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health management within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a strategic plan consistent with the objectives of Saudi Vision 2030. Vision 2030 underscores the paradigm shift in the medical field aimed at improving the quality of medical services, enhancing access, and guaranteeing sustainable development. Artificial intelligence is essential for accomplishing these goals by facilitating early disease identification, individualised treatment, optimised resource distribution, and effective decision-making. The implementation of AI in healthcare presents significant ethical, legal, and regulatory issues that require careful management to guarantee the appropriate and equitable application of AI technologies. These considerations encompass concerns pertaining to fairness, transparency, patient confidentiality, accountability, data protection, and adherence to regulations. Tackling those issues is crucial for fostering confidence among healthcare practitioners, patients, and the public, while guaranteeing that AI is consistent with the objectives of Vision 2030. This research question consists of three sub-components in order to provide a comprehensive answer to this research question. These include the ethical consideration, the regulatory consideration, and the management of ethical and regulatory considerations. Details of each component are provided below.

3.3.1. Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are crucial in the implementation of AI in healthcare, as they handle challenges related to fairness, transparency, accountability, and patient rights. A significant issue is the possibility of bias in AI systems, stemming from biassed training data, which may result in inequitable treatment of specific patient populations. AI models trained on imbalanced datasets may exhibit lower results for minority groups, as evidenced by research like Dahan, Alroobaea [33], which underscored the necessity of diverse training datasets for attaining high accuracy in vital sign classification. Transparency and explainability are essential, as AI systems frequently function as “black boxes,” complicating the comprehension of decision-making processes. This absence of transparency can undermine confidence between healthcare practitioners and patients. Moreover, patient privacy and autonomy are essential, as AI systems frequently depend on the acquisition and examination of sensitive patient information. Securing patient permission and safeguarding their privacy is crucial for upholding trust and ethical norms. Ultimately, accountability is a significant issue, as ascertaining culpability for AI-generated decisions, particularly in instances of errors or harm, is intricate. In response to these ethical challenges, Saudi Arabia has implemented ethical principles for AI, prioritising fairness, openness, and responsibility. The Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority (SDAIA) has established standards to guarantee the responsible utilisation of AI systems. Initiatives are underway to recognise and rectify biases in AI models through the utilisation of varied training datasets and systematic audits, as exemplified in the HRGC model [33]. Alongside universal ethical norms, the Saudi healthcare framework necessitates conformity with Islamic ethical philosophy, integral to the legal and cultural foundation of the national health system. The Kingdom’s ethical assessment of AI applications in healthcare is informed by both international norms and values from Maqāṣid al-Sharīʿah, encompassing the preservation of life, dignity, privacy, and justice. These principles are integrated into current healthcare governance and guarantee that AI implementation aligns with religious and cultural norms. Integrating this ethical principle enhances the reliability and societal acceptance of AI implementation in Saudi Arabia and aligns with national directives established by SDAIA and the Ministry of Health.

3.3.2. Regulatory Considerations

Regulatory considerations relate to the supervision and regulation of AI systems to guarantee their safety, efficacy, and conformity with national objectives. A primary concern is the rigorous testing and validation of AI systems to ensure their security and efficient performance in real-world healthcare environments. Dahan, Alroobaea [33] illustrated the significance of validation in attaining a high accuracy of 99.69% in vital sign classification utilising the HRGC model. Standardisation is a crucial concern, as the establishment of standards for AI research and implementation guarantees consistency and interoperability among medical systems. Ongoing surveillance of AI systems is essential to detect and rectify problems such as reductions in performance or unforeseen repercussions. El-Sherif, Abouzid [51] emphasised the necessity for ongoing surveillance in AI-driven telehealth and remote monitoring systems throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Regulatory frameworks are required to comply with the objectives of Saudi Vision 2030, including enhancements in healthcare quality, accessibility, and sustainability. Saudi Arabia has instituted regulatory agencies, including the SDAIA and the Ministry of Health (MOH), to supervise artificial intelligence in healthcare. Those bodies are tasked with establishing standards, sanctioning AI systems, and monitoring adherence. The Ministry of Health has established rules for the implementation of AI systems, whilst the Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority assures compliance with ethical and legal requirements for these systems. This evaluation examined national policy frameworks regulating AI and health data to ensure compliance with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s regulatory and ethical standards. Ethical concerns were guided by the Saudi Data and AI Authority (SDAIA) National Data Governance Framework, the National Data Management Office Data Sharing Framework, the Saudi Principles of AI Ethics, and the Ministry of Health’s Health Sector Data Privacy Regulations. These rules outline mandates for data security, informed consent, privacy, accountability, transparency, and the proper implementation of AI in healthcare environments. The ethical framework for AI deployment is associated with Vision 2030’s Health Sector Transformation Program, which prioritises secure digital health ecosystems and regulated data utilisation. This evaluation assesses the included studies in accordance with national requirements to ensure that ethical issues align with the unique regulatory expectations of Saudi Arabia, rather than generic worldwide norms.

Furthermore, AI systems are subjected to extensive testing and validation prior to implementation, encompassing clinical trials and evaluations of real-world performance, as evidenced by the HRGC model developed in [33].

3.3.3. Management of Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

Saudi Arabia is employing a comprehensive strategy to tackle ethical and regulatory issues. This includes the collaboration with international agencies like the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), to guarantee that Saudi regulations conform to worldwide best practices. The Ministry of Health engages with international organisations to establish standards for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Capacity building is crucial, as educating healthcare professionals, developers, and policymakers in AI ethics, legal compliance, and regulatory frameworks guarantees ethical AI implementation. The HRGC model proposed by Chau, Rahman [68] underscores the necessity of teaching healthcare professionals to utilise AI-driven solutions proficiently. Public awareness is a crucial element, as teaching patients and the general public about the advantages and disadvantages of AI in healthcare fosters confidence and guarantees informed consent. El-Sherif, Abouzid [51] emphasised the significance of public knowledge in the effective implementation of AI-driven telehealth systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ultimately, innovation and adaptation are promoted while maintaining adherence to ethical and legal standards, creating a balanced methodology for AI research and implementation. By handling these problems, Saudi Arabia is establishing itself as a leader in the ethical and responsible application of AI in healthcare, in accordance with Vision 2030 goal.

In a nutshell, the ethical, legal, and regulatory implications of employing AI in health management within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia are substantial yet manageable. Saudi Arabia is guaranteeing the responsible and equitable use of AI through the implementation of ethical frameworks, formulating thorough legal and regulatory structures, and interacting with stakeholders. These initiatives correspond with the Vision 2030 objectives of enhancing healthcare quality, accessibility, and sustainability, while tackling issues like as bias, privacy, and accountability. By means of ongoing surveillance, cooperation, and innovation, Saudi Arabia is establishing itself as a frontrunner in the legal and ethical application of AI in healthcare.

3.4. What Are the Key Performance Metrics Used to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Enhancing Healthcare Management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia? (RQ4)

The deployment of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in managing medical services in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a strategic scheme in line with the objectives of Saudi Vision 2030. Vision 2030 underscores the change in the healthcare sector to improving care quality, augmenting accessibility, and guaranteeing sustainable development. Artificial intelligence is crucial for accomplishing these goals by facilitating early disease identification, tailored treatment, optimised resource distribution, and effective decision-making. The efficacy of AI in healthcare is assessed by various key performance indicators that measure its influence on diagnostic precision, operational efficiency, patient outcomes, system responsiveness, financial viability, and workforce advancement. These metrics offer a thorough framework for comprehending the role of AI in transforming the landscape of medical services in Saudi Arabia, assuring alignment with the nation’s overall development objectives. Detailed descriptions of each of the metrics are provided below:

3.4.1. Diagnostic Accuracy and Precision

Diagnostic accuracy and precision serve as vital parameters for assessing the efficacy of AI in healthcare. These metrics assess the capability of AI systems to accurately diagnose health conditions, thereby minimising diagnostic errors and enhancing clinical results. For instance, Dahan, Alroobaea [33] demonstrated that the hybrid ResNet-18 + GoogleNet (HRGC) model achieved a classification accuracy of 99.69% for vital signs, surpassing standard classifiers such as VGG16 and AlexNet. In another study, Tzeng, Hsieh [69] also showed that AI-assisted chest X-ray models for COVID-19 diagnosis, attaining 84% accuracy and an AUC of 0.82. The improvements in accuracy rates underscore AI’s capacity to improve diagnostic precision, facilitating early disease identification and prompt medical treatment. By minimising diagnostic inaccuracies, AI enhances patient results and alleviates the workload of healthcare personnel, in accordance with the objectives of Vision 2030 to deliver better healthcare services.

3.4.2. Operational Efficiency and Resource Utilisation

Operational efficiency and resource utilisation are critical measures for evaluating AI’s effectiveness in healthcare management. These measures assess the efficacy of AI in optimising processes, minimising wait times, and enhancing the distribution of resources such as hospital beds, healthcare workers, and medical supplies. Several selected studies demonstrated the operational efficiency and resource utilisation in Saudi healthcare management. For instance, AlMuhaideb, Alswailem [32] employed JRip and Hoeffding Tree models for predicting outpatient no-shows, attaining an accuracy of 77.1% and an AUC of 0.861. This predictive potential allows healthcare practitioners to enhance appointment booking and minimise the use of resources. Similarly, Daghistani, Elshawi [43] proved the efficacy of the Random Forest (RF) model in predicting in-hospital length of stay (LOS) for cardiac patients, and the predictive outcome attained an accuracy of 80% and an AUROC of 0.94. Thus, hospitals may optimise resource allocation and mitigate operational inefficiencies by accurately predicting length of stay. The enhancements in performance foster the sustainable development of healthcare systems, in accordance with Vision 2030’s focus on efficient and cost-effective healthcare provision.

3.4.3. Patient Outcomes and Satisfaction

Another crucial metric for evaluating the efficacy of AI in healthcare is patient outcomes and satisfaction. These measures evaluate the enhancement of therapy efficiency, recovery durations, and the overall patient experience through AI. Few studies evaluated the effectiveness of the patient outcomes and satisfaction. It is crucial to acknowledge that patient satisfaction in the analysed studies is predominantly reported indirectly or qualitatively, with a limited number of studies utilising standardised or validated measurement tools. For example, Rathee, Garg [31] created a hybrid Generative AI framework (RLHF + ANP) for healthcare decision support, which attained 98.8% accuracy with reduced latency and overhead. This technology delivers faster, tailored services for disabled and elderly patients, enhancing patient satisfaction and compliance with the treatment plans. In a related study, Al-Jehani, Hawsawi [26] emphasised the efficacy of the Sarah chatbot in improving patient involvement and adherence to treatment protocols. By prioritising patient-centred care, AI guarantees that individuals have prompt and tailored attention, in accordance with Vision 2030’s goal of enhancing the quality of life for all citizens. Moreover, AI’s capacity to minimise re-admission rates while improving recovery durations further improves patient results, so increasing to the overall effectiveness of healthcare reform.

3.4.4. System Responsiveness and Innovation

System responsiveness and innovation constitute vital measures for assessing AI’s influence on healthcare operations. These measures evaluate the extent to which AI improves healthcare systems’ responsiveness to emerging challenges and facilitates technological improvements. To measure the effectiveness of AI based on system responsiveness and innovation, Qaffas, Hoque [39] developed an IoT-driven machine learning system for chronic disease prediction, attaining an accuracy of 71.15% using support vector machines. This approach facilitates the early identification of chronic illnesses, enhancing the responsiveness of healthcare systems to patient requirements. Similarly, El-Sherif, Abouzid [51] demonstrated the utilisation of AI-driven telehealth and remote monitoring during the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby enhancing access to healthcare and mitigating exposure risks. These applications underscore AI’s contribution to improving system responsiveness and fostering innovation, in accordance with the objectives of Vision 2030 to advance innovative health systems. Through the utilisation of AI, Saudi Arabia can tackle growing health concerns, enhance system reliability, and cultivate a culture of ongoing innovation in healthcare.

3.4.5. Financial and Economic Impact

The financial and economic impact of AI in the health sector is assessed using measures including cost savings, income generation, and return on investment (ROI). These metrics evaluate the extent to which AI enhances the financial stability of healthcare systems by decreasing operating expenses and optimising resource utilisation. The economic savings reported in the reviewed research were varied, with many based on approximated or simulated cost models rather than directly observed financial effects. This indicates a significant barrier in the existing literature, wherein empirical economical evaluations of AI-driven healthcare interventions are sparse. Dahan, Alroobaea [33] illustrated the HRGC model’s efficacy in minimising diagnostic mistakes, resulting in cost reductions for treatment and follow-up care. In another study, Alkattan, Al-Zeer [45] demonstrated AI’s efficacy in the initial identification of Type 2 Diabetes, hence decreasing the long-term expenses associated with chronic disease management. Through process automation and enhanced diagnostic precision, AI decreases the probability of expensive errors and optimises resource distribution. These financial advantages correspond with Vision 2030’s objective of attaining financial stability in healthcare, guaranteeing the sector’s sustainability and resilience against future problems.

3.4.6. Human Capital Development and Workforce Efficiency

Human capital development and workforce efficiency are other important parameters for evaluating AI’s impact on healthcare management. These measures evaluate the extent to which AI improves the knowledge and performance of healthcare workers, facilitating the provision of high-quality care with greater efficiency. The study by Dahan, Alroobaea [33] emphasised the HRGC model’s function in automating vital sign classification, hence alleviating stress for healthcare workers. Likewise, Rathee, Garg [31] underscored the knowledge-centric training facilitated by AI frameworks, augmenting the competencies of healthcare professionals. By providing employees with AI-powered tools and training, Saudi Arabia may create an exceptionally skilled staff capable of advancing the evolution agenda of Vision 2030. These enhancements in personnel efficiency strengthen patient care as well as help in the long-term viability of the healthcare sector.

In a nutshell, these key performance indicators are employed to measure the efficacy of AI in facilitating healthcare management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, offering a thorough framework for evaluating AI’s influence on healthcare delivery, ensuring alignment with the objectives of Saudi Vision 2030 to enhance healthcare services and attain sustainable development. Utilising these measures, stakeholders may enhance AI integration, foster innovation, and guarantee that AI remains pivotal in revolutionising the healthcare industry in Saudi Arabia.

3.5. What Are the Challenges and Barriers to the Adoption and Implementation of AI Technologies in Health Management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and How Can These Challenges Be Addressed? (RQ5)

The implementation of AI in Saudi Arabia brings about ground-breaking and lasting changes within the healthcare sector. This shift has several challenges that must be swiftly addressed to guarantee cohesive development and national acceptance [70]. The main barriers are data privacy and security, workforce management, high implementation costs, cultural concerns over AI adoption, and integration with current healthcare facilities [71,72]. Resolving these issues necessitates a planned, integrated strategy. This strategy enhances the digital infrastructure to facilitate a sustainable AI ecosystem within the healthcare sector. Addressing these barriers allows Saudi Arabia to leverage the capabilities of AI in the healthcare sector in accordance with Saudi Vision 2030. The prospective barriers to AI integration within the Saudi Arabian Public Healthcare System encompass Data Privacy and Security Issues, Insufficient Skilled Workforce, Implementation Costs, Resistance to Change, Regulatory and Ethical Challenges, Algorithmic Bias and Local Impact, and Infrastructure and Technological inefficiencies. The comprehensive description of each of the barrier is as follows:

3.5.1. Data Privacy and Security Issue

The misuse of healthcare data can erode patient trust and provide substantial ethical and operational issues for healthcare organisations [73]. In Saudi Arabia, these issues are exacerbated by stringent national data governance mandates, including data sovereignty requirements under SDAIA regulations and the Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL), which limit cross-border data transfer and necessitate the localisation of sensitive health information. To combat these challenges, privacy-preserving AI methodologies, especially federated learning, provide a feasible solution by facilitating model training on decentralised datasets without the need to upload raw patient data. When executed in accordance with Saudi data-governance principles, federated learning fosters adherence to national data sovereignty regulations, improves the confidentiality of personal medical records, and mitigates legal risk. Furthermore, incorporating this method into a data-governance framework guarantees that privacy technology functions not only as an operational instrument but also as a means of imposing policy, accountability, and institutional transparency. This technique fosters patient trust, complies with national regulations, and conforms to international best practices for the ethical implementation of AI in healthcare [74]. In addition, the Data Sovereignty Privacy Technology Balance Model (DSPTBM), is yet another framework developed to incorporate federated learning within the context of Saudi data sovereignty regulations, including the Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL) [75]. This model guarantees adherence to regulations by executing local data processing to retain raw data within the territory of Saudi Arabia, developing a regulatory compliance framework to synchronise federated learning procedures with national legislation, and managing cross-border data transfer through secure aggregation methods. The model also incorporates verification mechanisms, including regulatory audits, technical substantiation through cryptographic techniques such as secure multi-party computation (SMPC), and stakeholder feedback, to consistently enhance compliance and operational efficiency while protecting sensitive data.

3.5.2. Insufficient Skilled Workforce

The effective implementation of AI in healthcare necessitates a workforce proficient in data analytics, AI, and healthcare application skills in domains where Saudi Arabia presently encounters considerable deficiencies [70]. To tackle this challenge, Saudi healthcare institutions should prioritise training programmes and create specialised academic pathways centred on the integration of AI and healthcare. These programmes may create an expert regional talent pool by offering experiential education and practical exposure in AI applications. Furthermore, the government may significantly contribute by establishing worldwide collaborations with prominent AI research institutions. Such alliances can promote exchange programmes, knowledge dissemination, and joint research projects, allowing local professionals to acquire exposure to international best practices. To enhance career growth, the government might provide grants to healthcare workers seeking higher specialisation in AI, thereby ensuring a continuous influx of experienced specialists to foster innovation and acceptance in the healthcare industry.

3.5.3. Implementation Cost

The first implementation expenses of AI adoption can provide a considerable barrier, especially for smaller healthcare institutions, rendering the financial commitment seem unaffordable [76]. The government should create a specialised AI in Healthcare Fund to mitigate this barrier, focusing on activities that support Vision 2030 objectives, including the enhancement of preventive medicine and the improvement of chronic disease management. This fund would offer specific financial assistance to healthcare organisations, facilitating the adoption of AI technologies without affecting their operational funds. Additionally, healthcare institutions may employ a modular strategy for AI integration, first with smaller, scalable systems that provide immediate benefits while reducing costs [77]. Through the incremental incorporation of AI tools, organisations can exhibit concrete advantages and foster momentum for extensive adoption, assuring enduring sustainability and alignment with national healthcare goals.

3.5.4. Resistance to Change

The resistance of patients and healthcare providers to accept AI technology frequently arises from worries over job displacement and insufficient understanding of its functionalities [78]. To alleviate these issues, healthcare organisations should implement change management strategies that highlight AI as an instrument for augmenting, rather than substituting, human expertise. Spreading case studies that underscore AI’s beneficial effects on health outcomes, operational efficiency, and decision-making helps foster trust and illustrate its usefulness. Furthermore, appointing “AI Champions” within healthcare organisations, trusted personnel with specialised AI training, can significantly contribute to promoting its advantages and addressing concerns regarding it. These champions can act as ambassadors, promoting a culture of collaboration and innovation by informing patients and other healthcare professionals about AI’s capacity to enhance care delivery and results [79].

3.5.5. Regulatory and Ethical Challenges

The lack of explicit legislative frameworks for AI in healthcare generates ambiguity for supply chain partners and other stakeholders, preventing the efficient development and implementation of AI systems [80]. The formation of a specialised regulatory entity consisting of many healthcare stakeholders is important in addressing this issue. This body would be essential in facilitating the development of AI-specific legislation, ensuring it is thorough, culturally appropriate, and customised to the distinct requirements of the healthcare ecosystem. This legislative framework can promote innovation while ensuring patient safety, data privacy, and ethical AI utilisation through the provision of clear and uniform norms.

3.5.6. Algorithmic Bias and Local Relevance

AI algorithms trained on non-regional data frequently yield unreliable results in Saudi Arabia because of its unique demographic and health-related tendencies that may add substantial biases [81]. To address the issue, legislators should establish regulations requiring bias audits and fairness assessments for AI models. These procedures guarantee that AI systems undergo thorough assessment for any biases and inconsistencies, aligning them with the distinct demands and attributes of the Saudi population. Moreover, establishing collaborative research alliances between AI developers and Saudi Arabian healthcare institutions might improve the precision, equity, and effectiveness of AI models. Utilising local data and expertise, these collaborations can enhance AI algorithms to more accurately represent regional health trends, hence increasing the efficacy and reliability of AI applications for medical services [82].

3.5.7. Infrastructure and Technological Inefficiencies

A reliable digital infrastructure, encompassing high-speed internet connections and sophisticated data storage capabilities, is essential for the effective deployment of AI in healthcare. Confronting this challenge necessitates a planned enhancement of current digital infrastructure to facilitate healthcare AI initiatives [83]. By implementing these essential components, Saudi Arabia can establish a conducive climate that facilitates the seamless integration of AI inside the healthcare sector. These strategic solutions not only address deployment issues but also establish the Kingdom as a global leader in culturally adaptable, secure, and successful AI-powered healthcare innovation. By emphasising digital infrastructure and establishing a partnership ecosystem, Saudi Arabia can synchronise its AI operations with the general goals of Vision 2030, facilitating dramatic improvements in healthcare delivery and patient satisfaction.

4. Potential Future Directions for AI Research and Development Within the Saudi Healthcare System

The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into the Saudi healthcare system offers a significant opportunity to improve healthcare delivery, better patient outcomes, and alignment with the objectives of Saudi Vision 2030. Despite considerable advancements, there exists considerable opportunity for further study and development in various critical domains. This section outlines prospective potential directions for AI in Saudi healthcare, emphasising domains such as drug discovery, workforce optimisation, health data management, public health, AI ethics, chronic disease management, and advancements in AI technology. A detailed description of each of the future directions is provided below.

4.1. Drug Discovery and Development

AI-powered drug discovery and development have a lot to offer Saudi Arabia’s pharmaceutical sector. Complex genetic information can be analysed by AI algorithms to find possible drug candidates, predicting their effectiveness, and enhancing clinical trial designs [84,85]. This minimises the time to market and lowers expenses by speeding up the medication development process. AI, for example, can model the interactions between various chemicals and biological targets, assisting researchers in creating more efficient therapies for conditions like diabetes, cancer, and infectious diseases [84,86]. Furthermore, by predicting how particular patients would react to particular drugs, AI helps personalise medicinal therapy and facilitate the development of individualised treatment plans. This strategy supports Saudi Arabia’s goal to develop a strong pharmaceutical industry and minimise dependency on foreign medications.

4.2. Healthcare Workforce Optimisation

Routine tasks can be automated by AI, which can provide healthcare personnel with decision support tools. This can optimise the healthcare workforce. For instance, AI-powered systems can manage electronic health records (EHRs), process insurance claims, and schedule appointments, thereby enabling physicians and nurses to concentrate on patient care [87]. In addition to assisting medical professionals to make better choices, AI can also provide real-time decision support during operations, examinations, and treatment plans [88]. In Saudi Arabia, where there is an increasing need for medical services, AI might reduce shortages of staff by enhancing efficiency and allowing healthcare providers to manage a greater number of patients without lowering quality.

4.3. Health Data Management and Security

The efficient management and protection of health data are essential for AI-powered advancements in healthcare. Artificial intelligence can analyse extensive datasets from electronic health records, wearable technology, and additional sources to identify trends, predict disease outbreaks, and enhance the management of public health. Nonetheless, protecting data privacy and security is of paramount importance. AI-powered encryption and privacy-preserving methods can protect patient data, while adherence to Saudi Arabia’s data protection laws, including those implemented by the Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority (SDAIA) [89], can guarantee the ethical and legal use of personal health data. By utilising AI for reliable and efficient data management, Saudi Arabia can build trust in AI-driven medical services and achieve the full benefit of big data analytics.

4.4. Public Health and Epidemiology

Artificial intelligence can significantly contribute to public health by facilitating real-time disease monitoring and epidemic prediction. In Saudi Arabia, where significant events such as the Hajj and Umrah draw millions of attendees, AI can analyse health data to swiftly identify and address possible outbreaks. AI systems may examine data from hospitals, pharmacies, and wearable devices to recognise patterns indicating infectious diseases, including COVID-19 and influenza [90]. This facilitates early intervention, resource distribution, and focused public health initiatives. Furthermore, AI can evaluate population-level health data to discern risk factors for chronic diseases, including obesity and diabetes, and guide preventive strategies. Integrating AI into public health plans will enable Saudi Arabia to augment its capacity to protect and strengthen the health of its citizens.

4.5. AI Ethics and Governance

As AI increasingly integrates into healthcare, ethical issues and governance structures are crucial to guarantee appropriate and equitable utilisation. Saudi Arabia can formulate ethical standards for AI development, emphasising transparency, fairness, accountability, and patient consent. AI systems must be engineered to eliminate biases that may result in inequalities in healthcare access or outcomes. Regulatory authorities can collaborate with stakeholders to establish standards for AI implementation, guaranteeing that AI tools are secure, efficient, and consistent with national healthcare regulations. By emphasising AI ethics and governance [87], Saudi Arabia can foster trust in AI-powered healthcare solutions and guarantee their advantages for all societal sectors.

4.6. AI in Chronic Disease Management