1. Introduction

As environmental pressures escalate, the financial sector increasingly acknowledges the need for instruments that deliver both economic returns and sustainable outcomes. Green bonds (GBs) and green banking loans (GBLs) have emerged as central tools in financing low-carbon initiatives [

1,

2]. GBs, introduced by the European Investment Bank in 2013, rapidly expanded as climate-related risks reshaped investor preferences toward sustainable assets [

3]. GBLs, structured to fund projects meeting strict environmental criteria, further reinforced the role of banks in sustainability transitions [

4,

5].

Both instruments are grounded in sustainable finance, integrating ESG factors into investment decisions. GBs enable long-term financing of climate policies while delivering favorable market outcomes, including enhanced corporate performance and investor trust [

6,

7,

8]. Empirical studies also highlight improved profitability and ESG ratings for issuers [

9].

The literature devotes particular attention to the greenium, defined as the yield differential between GBs and conventional bonds [

10]. Evidence is mixed: some studies report lower spreads for green issuers [

11], while others find no significant association [

12]. Market conditions, issuer credibility, and external reviews are critical determinants, with the energy sector often displaying stronger effects [

13]. The greenium’s presence can lower capital costs, promote green infrastructure, and reinforce demand in both primary and secondary markets [

14].

Research on GBLs indicates positive effects on financial stability, including reduced default risk and alignment of profitability with environmental responsibility [

15,

16]. Global agreements, notably the Paris Agreement, have been instrumental in shaping lending practices [

17]. However, both markets face persistent barriers: risks of greenwashing, limited liquidity, and high issuance costs [

18,

19]. Overcoming these requires stronger regulatory standards, verification mechanisms, and policy incentives [

20,

21].

Despite growing attention, comparative systematic reviews of GBs and GBLs remain scarce. This study addresses that gap through a systematic literature review (SLR) aimed at (i) evaluating their effectiveness for corporate performance, sustainability maturity, and investor behavior; (ii) identifying issuance drivers and barriers; (iii) assessing the influence of international policy frameworks; and (iv) providing recommendations for policymakers and practitioners (financial institutions and investors). By consolidating existing evidence, this SLR advances our understanding of sustainable debt instruments, highlights unresolved debates such as the greenium, and identifies opportunities for further research.

The main objective of this study is to conduct a systematic narrative review of the academic literature comparing green bonds and green banking loans. Specifically, we aim to identify and categorize the main research themes and theoretical frameworks that underpin both GB and GBL studies; examine the empirical evidence regarding pricing behavior, market maturity, and the existence of a greenium; analyze the role of regulation, governance, and certification in shaping market credibility and performance; and highlight research gaps and propose future directions for the development of an integrated understanding of green finance instruments.

This study contributes to the literature in three key ways. First, it provides the first comprehensive synthesis directly comparing GBs and GBLs within a unified analytical framework. Second, it develops a conceptual model linking market characteristics, regulatory quality, and financial outcomes, thereby advancing theoretical integration in sustainable finance research. Third, it establishes an agenda for future empirical investigation, forming the conceptual basis for ongoing quantitative studies on the determinants of the greenium and strategic decision-making in green financing.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the methodological approach and selection criteria used in the systematic narrative review.

Section 3 presents the results, organized by key analytical dimensions such as market development, financial performance, and regulatory context.

Section 4 offers a detailed discussion of the findings, connecting them to theoretical perspectives and regional differences.

Section 5 concludes by summarizing the study’s main insights, discussing its limitations, and outlining recommendations for both policy and future research.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic review is a structured methodology that identifies, evaluates, and synthesizes existing studies to draw clear conclusions about current knowledge [

22]. It enhances reliability and validity by ensuring inclusivity and reducing bias [

23], while also exposing research gaps that inform future studies and theory development [

24]. Adherence to predefined protocols further strengthens replicability, verification, and credibility [

25].

2.1. Scope

The scope of this review encompasses studies that primarily address the rapidly evolving field of GBs and GBLs, which have attracted substantial attention in recent years for their potential to tackle environmental and social challenges.

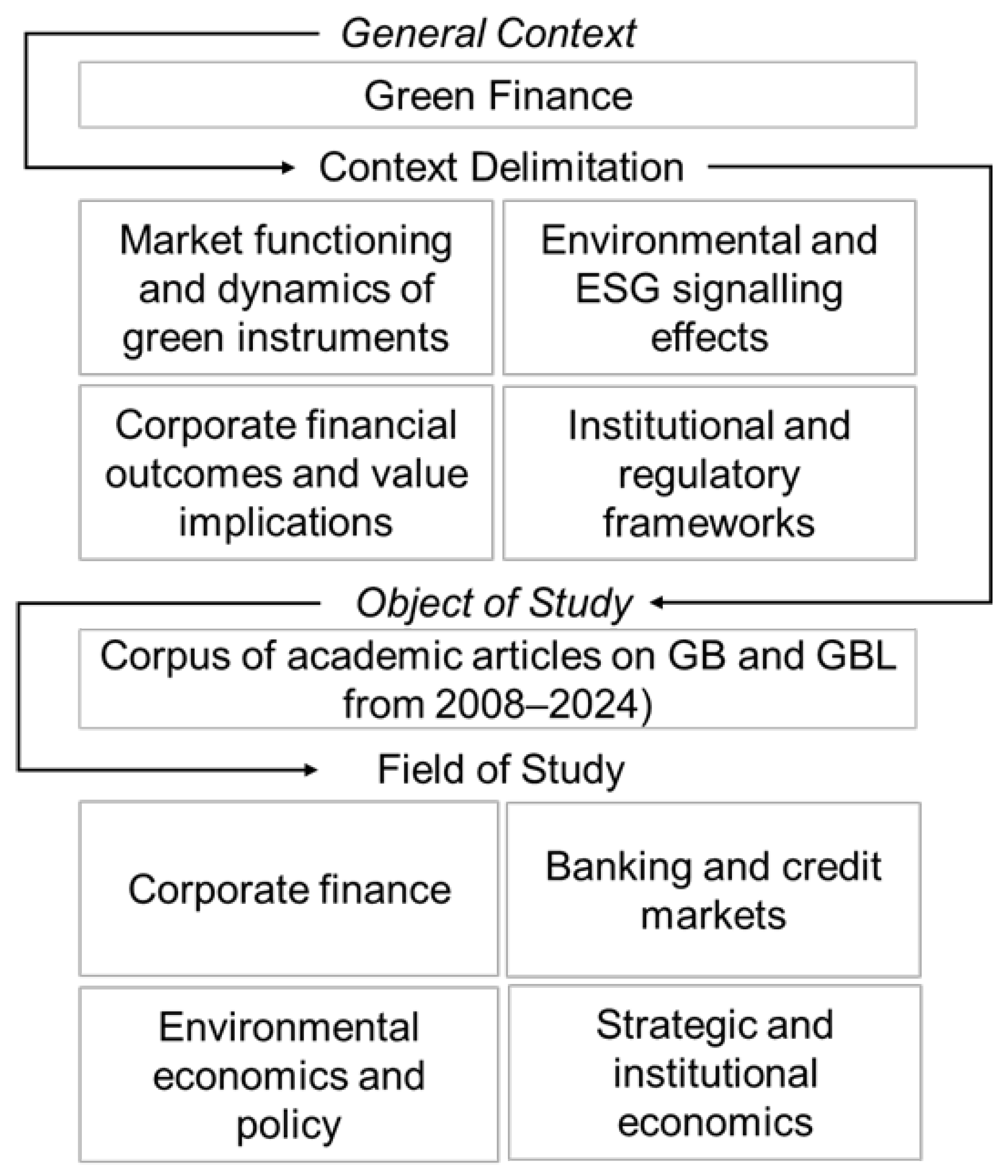

Figure 1 presents the conceptual structure guiding the SLR. The review is methodologically delimited around a set of macro-thematic domains that reflect the principal areas of academic inquiry within the green finance literature.

These domains include market dynamics and the development of green debt instruments, ESG signaling and environmental impact, corporate financial performance, regulatory and policy frameworks, and the strategic behavior of issuers and financial agents. Rather than outlining procedural steps, the diagram defines the analytical scope and thematic boundaries of the review, positioning the study within the broader field of sustainable finance and applied financial economics.

The review covers publications from 2008, marking the inception of green debt, through the first quarter of 2024. While highlighting global trends, it also considers regional developments, with emphasis on Europe, North America, and China, where green finance has advanced most rapidly. The study follows a systematic methodology with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure relevance and quality, retaining only peer-reviewed works. Eligible studies provide empirical evidence or theoretical insights into GBs and GBLs. An integrative analytical framework synthesizes findings across multiple dimensions, including the effectiveness of these instruments in achieving environmental and financial outcomes, the drivers and barriers to their adoption, and the policy and regulatory contexts shaping their evolution.

2.2. Search Strategy and Sample Selection

The research aims to analyze the main debt instruments used to finance ESG-based projects, focusing on green bonds (GB) and green banking loans (GBLs), and to explore potential correlations between them. To achieve this, a systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted, limited to studies published in recognized international journals to ensure relevance and academic rigor. On 26 April 2024, we assessed two databases: Web of Science and Scopus, to select suitable articles for this review.

Following the guidelines of [

24], the process began with the identification of keywords and search terms. An initial list was tested for relevance using Google Scholar to eliminate unsuitable terms. Four keywords were retained: green bonds, green loans, greenium, and green banking. These terms enabled the construction of search strings using Boolean operators (AND, OR, *).

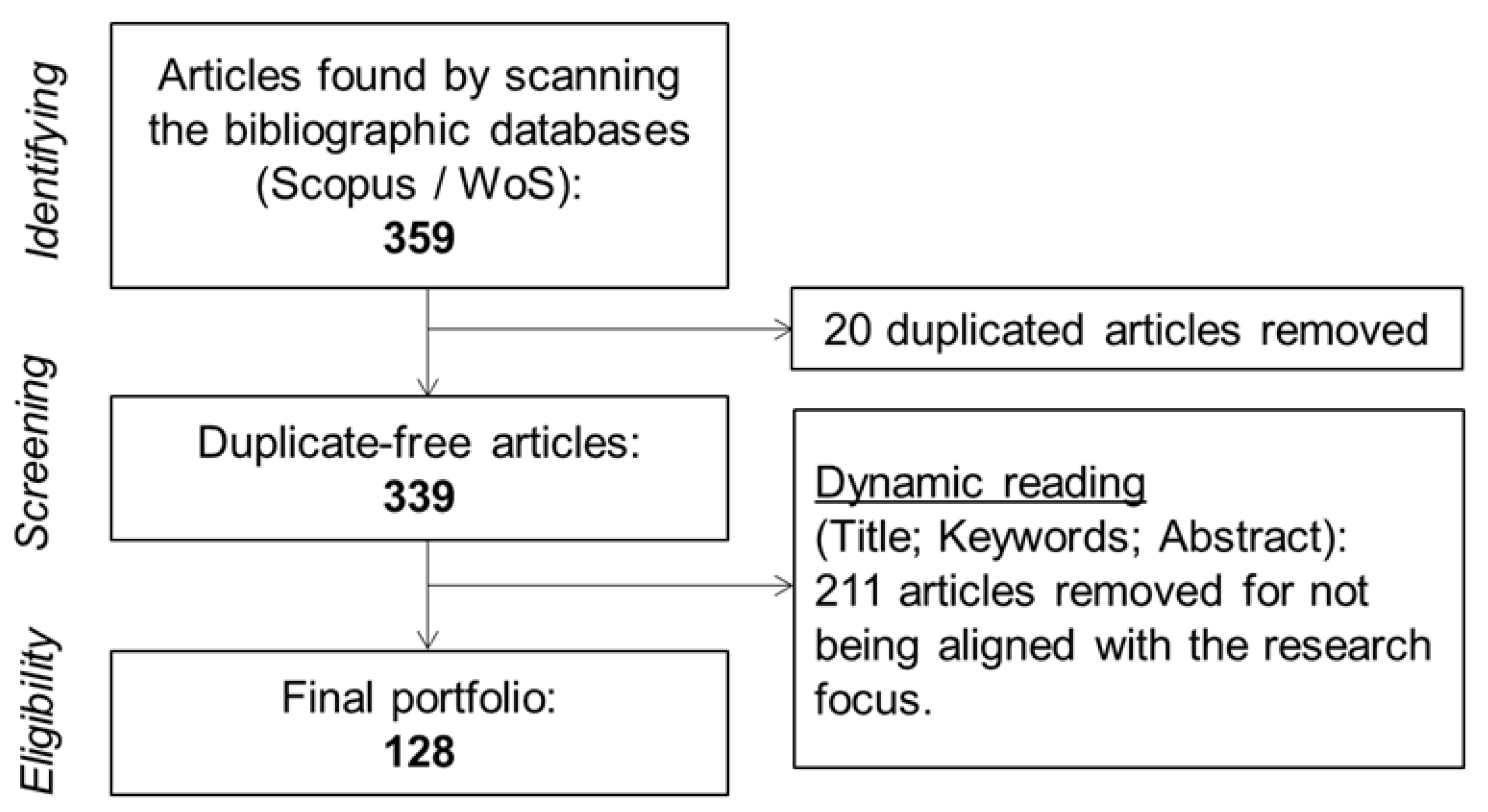

The review considered articles published between 2008 and March 2024, including earlier contributions from 2007 as GBs began to attract attention. Only English-language, peer-reviewed works were included, restricted to subject areas such as Management, Business, Accounting, Economics, Econometrics, and Finance. The initial search yielded 359 references, summarized in

Table 1.

The 359 results were imported into EndNote X7 to organize the references. Initially, duplicate references were removed using the software’s built-in duplication detection capability. Then, after seeing further duplicate references that the program had missed, a second filter was created, this time manually. This resulted from inconsistencies in the imported references, such as variations in the spelling of authors’ names, with some entries listing only initials while others included full names. Consequently, 20 duplicate references were identified out of the 359 original references assessed, leaving 339 after deletion.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied to assess each study’s relevance and determine whether it addresses the research question [

22]. Hence, only studies that meet all the inclusion criteria and exhibit none of the exclusion criteria should be incorporated into the review [

24]. The 339 papers were then screened for relevance to the study’s issue and objectives. This involved a dynamic reading (screening) of crucial components—Title, Abstract, Keywords, and Results. The main reasons for exclusion were: (a) references that were merely news, indexes, or summaries; (b) search keywords that appeared in the title or abstract but were not central to the article’s focus and did not align with the research objectives; (c) terms used with a different meaning; (d) lack of access to information from the abstract and, especially, from the full article; (e) studies that were too regional or had a peripherical emphasis. After this first reading and filtering, 211 items that weren’t aligned were eliminated, leaving 128 articles that made up the final portfolio for the SLR on green debt.

Figure 2 displays a flowchart that provides a concise overview of the SLR review technique. It outlines the criteria used to determine whether references are included or excluded and the process for selecting the corpus and final portfolio.

Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and full texts against the pre-specified eligibility criteria; disagreements were resolved by consensus or, when needed, a third reviewer. Duplicates were removed in EndNote prior to screening.

Figure 2 displays a flowchart that provides a concise overview.

2.2.1. Full Search Strategy

To ensure transparency according to PRISMA 2020, the complete search strings for each database are reported below. The completed PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided in the

Supplementary Materials. Searches were conducted on 26 April 2024.

Web of Science

TS=(“green bond*” OR “green loan*” OR greenium OR “green bank*”)

AND PY=(2008–2024)

AND LA=(English)

AND WC=(Economics OR Business OR Business Finance OR Management)

Scopus

TITLE-ABS-KEY (“green bond*” OR “green loan*” OR greenium OR “green bank*”)

AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2008–2024))

AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”))

AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “ECON”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “DECI”))

No additional filters were applied.

2.2.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

A formal risk-of-bias assessment was not performed. The review includes heterogeneous conceptual, qualitative and quantitative studies for which no single validated tool applies uniformly. Consistency of findings across independent empirical datasets and across thematic clusters was used as the primary basis for robustness appraisal.

2.3. Study Quality Assessment

The academic discussion on sustainable financing products, namely GBs and loans, is expanding and multifaceted. The increasing volume of study on this subject is proof of the growing recognition of finance’s pivotal role in achieving sustainable development goals.

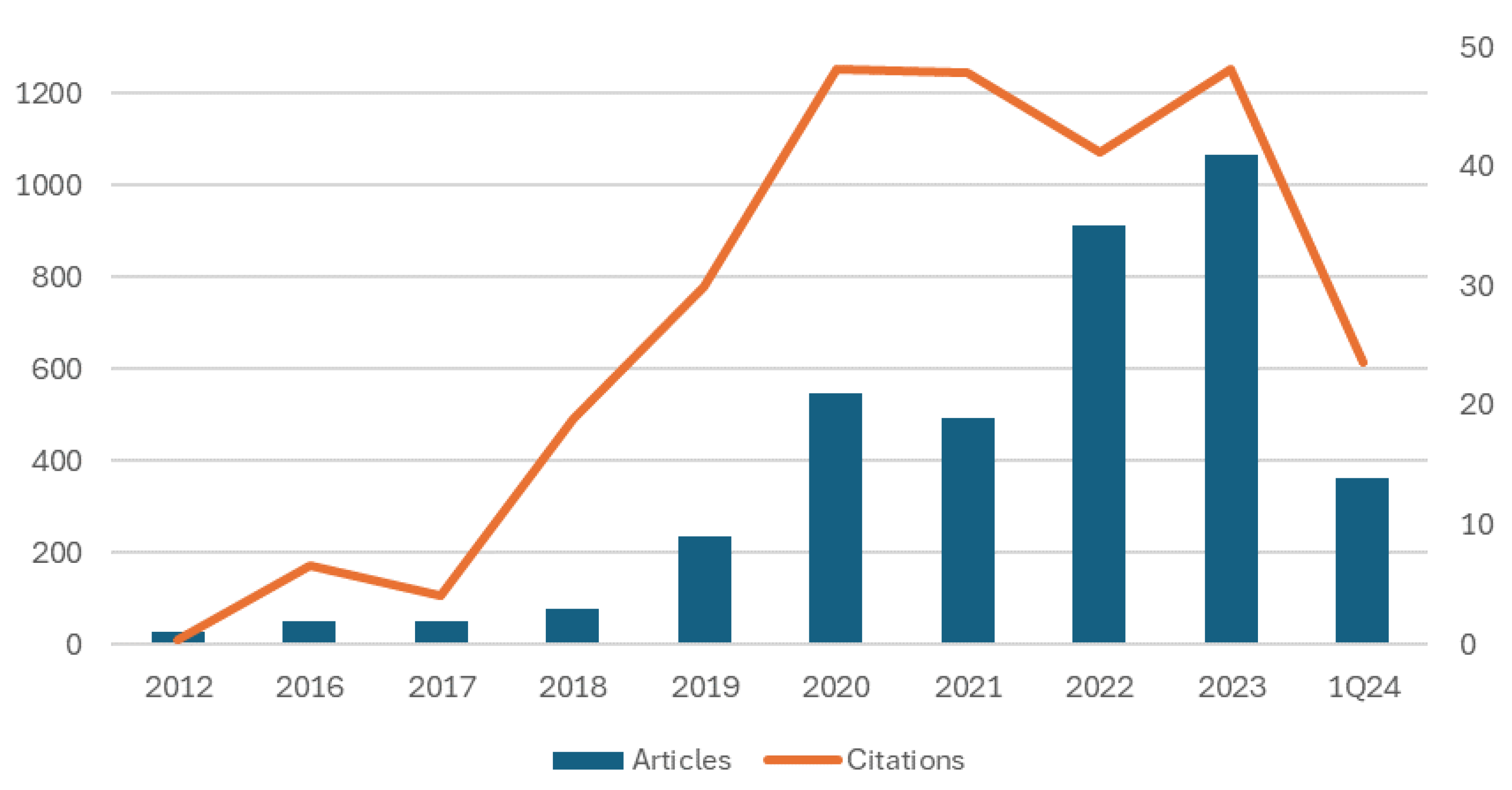

Figure 3 displays published papers’ yearly development and associated citation counts from 2012 to the first quarter of 2024.

Table 2 shows the ten studies with the highest number of citations.

The dataset shows steady growth in publications and citations, reflecting rising interest and influence in this field. From a single article with nine citations in 2012, output expanded to 41 articles and 1253 citations by 2023 (

Figure 3). A sharp increase occurred between 2016 and 2018, when citations more than doubled despite only a modest rise in publications, indicating particularly impactful studies. A further surge in 2019–2020 confirmed the field’s rapid expansion and consolidation.

By 2023, record highs in publications and citations confirmed the field’s vitality and established contribution to knowledge. Data from early 2024, with 14 articles and 615 citations, indicate that momentum is being sustained and possibly accelerating. The selected works are spread across several journals, notably Finance Research Letters (9 articles), Journal of Cleaner Production (7), Energy Economics (6), Journal of Risk and Financial Management (5), and Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment (5). The high citation count of Flammer’s article in the Journal of Financial Economics illustrates the growing interest of leading finance journals in green financing, particularly studies on the financial and environmental impact [

7].

2.4. Definition of the Theoretical Framework

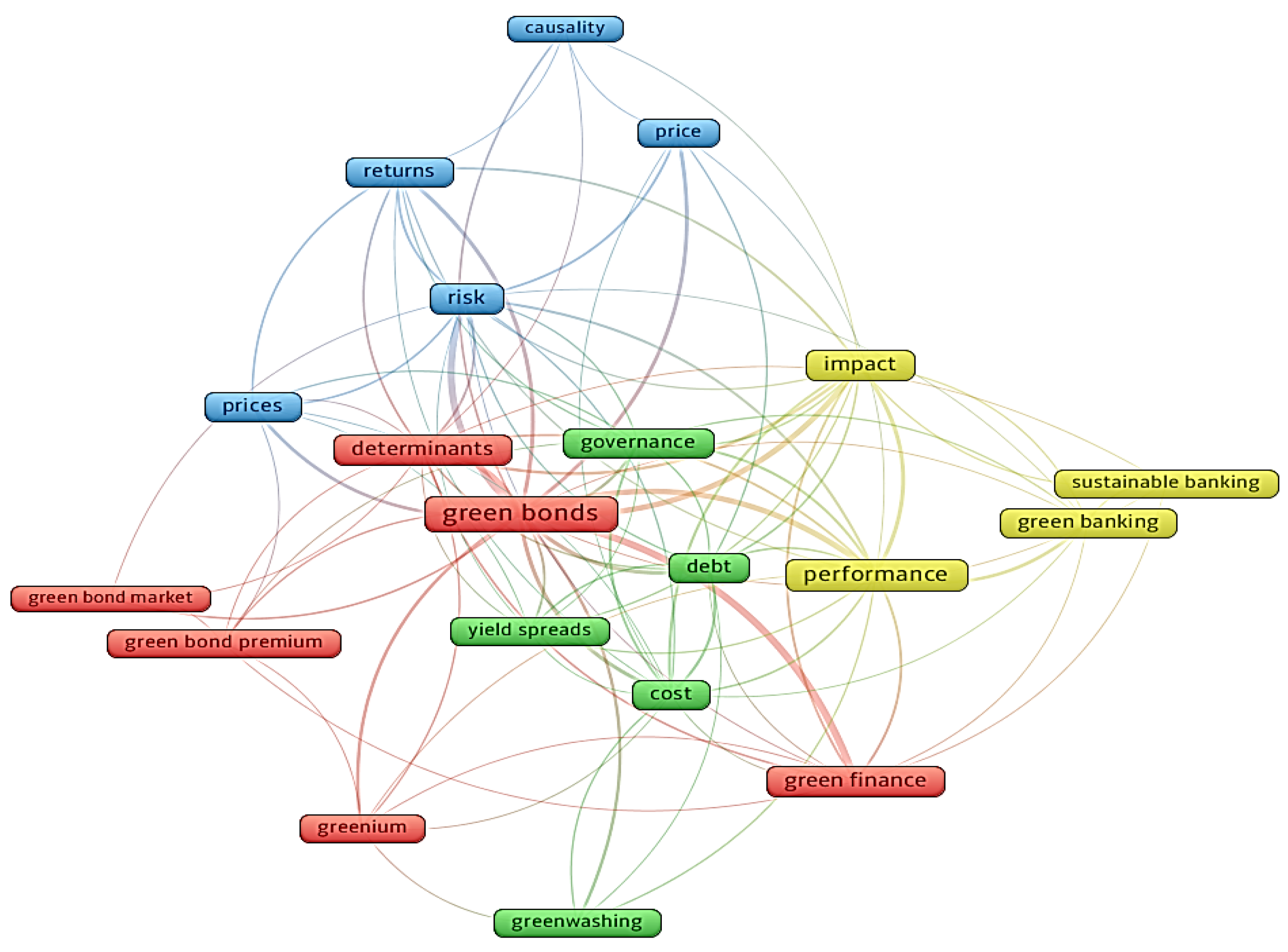

To establish the conceptual-theoretical framework of the SLR, we employed VOS viewer software version 1.6.20, which analysed the content of published literature, generating data clusters on the text to cluster related ideas.

The data were analyzed through content analysis to define study categories. Using VOS Viewer, clusters of related concepts were generated from published literature. The analysis showed that author-assigned keywords, refined during database indexing, are well suited for bibliometric analysis of debt instruments. Both author and indexed terms were used for a co-occurrence analysis. Of 475 keywords, only 20 met the minimum threshold of four occurrences. For these, the total strength of co-occurrence links was calculated.

Figure 4 presents the results, identifying four main clusters: GB, green banking, greenium/price, and governance/greenwashing.

Two reviewers independently extracted data using a piloted extraction form in [Excel], covering study metadata, context, instrument type (green bond or green banking loan), determinants and outcomes (financial performance, cost of debt, investor behaviour/greenium). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or, when needed, a third reviewer. Besides VOS Viewer no automation tools were used; entries were double-checked and version controlled.

2.5. Outcomes and Data Items

This review extracted data on five outcome domains: (i) determinants of issuance; (ii) financial performance; (iii) environmental performance; (iv) pricing outcomes including greenium; and (v) governance and regulatory mechanisms. For each study, the following items were collected: bibliographic data, study design, type of instrument analysed, variables related to financial and ESG outcomes, pricing characteristics, and documented spillovers. When information was unclear, assumptions followed standard definitions in sustainable finance literature.

2.6. Reporting Bias and Certainty Assessment

Reporting-bias assessment tools and certainty-of-evidence frameworks (e.g., GRADE) were not applicable due to the mixed methodological nature of the included studies and absence of comparable quantitative effect estimates. This limitation is acknowledged in the Discussion.

A formal certainty-of-evidence assessment (e.g., GRADE) was not applicable because the included studies were methodologically heterogeneous and did not yield comparable effect estimates.

2.7. Synthesis Methods

Given substantial heterogeneity in study designs and outcomes, a meta-analysis was not feasible. No statistical effect measures (e.g., risk ratios or mean differences) were applicable because the review synthesizes heterogeneous qualitative and quantitative evidence narratively. A narrative synthesis approach was applied, grouping studies by thematic domain. No statistical heterogeneity measures or sensitivity analyses were applicable. Data were tabulated in summary tables (

Appendix A), and no data transformations were required.

3. Results

The syntheses are organized according to the predefined thematic domains (green bonds, green banking loans, greenium, governance). For each domain, we summarize study characteristics and provide a narrative assessment of consistency across studies. Because no meta-analysis was possible, no pooled effect estimates, heterogeneity statistics, or sensitivity analyses were produced.

This section presents and synthesizes the main findings of the SLR concerning GBs and GBLs. It is structured to offer a detailed examination of each financial instrument, encompassing their definitions, market dynamics, financial and environmental impacts, and associated pricing phenomena such as greenium. By analyzing empirical and conceptual studies, the discussion highlights key patterns, identifies challenges and opportunities in the green debt market, and explores the broader implications for investors, issuers, and policymakers. The goal is to provide a comprehensive and critical understanding of the current state of research and practice in sustainable debt financing.

3.1. Green Bonds

3.1.1. Definition and Trends

Unlike traditional fixed-income bonds, green bonds (GB) allocate proceeds exclusively to environmentally sustainable projects [

1] (p. 25). According to ICMA (2022) [

33] (p. 3) green bonds are “instruments where the proceeds are exclusively applied to finance or refinance, in part or in full, new and/or existing eligible Green Projects”, underscoring their role in advancing sustainable development [

34].

Although interest in GBs emerged after the 2007 financial crisis, they gained traction only in 2013, when the European Investment Bank issued the first large-scale GB to fund renewable energy and energy efficiency projects. The World Bank’s issuance that same year marked another milestone.

Since then, GB issuance has expanded sharply [

2], particularly in Europe, driven by growing demand from investors and issuers for environmentally oriented projects [

3,

35]. This trend reflects both strong investor response and the increasing market value placed on environmental commitments.

The range of GB instruments is expanding. Ref. [

36] highlights the emergence of blue bonds, first issued by Seychelles in 2018, which fund ocean and freshwater projects but still account for less than 0.5% of the sustainable debt market. Between 2018 and 2022, 26 blue bond transactions totaled USD 5 billion, with a 92% annual growth rate.

Most GB funding supports renewable energy, energy efficiency, sustainable waste management, land use, biodiversity, and clean transport [

16,

37]. As ref. [

38] (p. 39) notes, leveraging investor preferences for sustainability could mobilize trillions needed to mitigate climate change. GBs thus represent a crucial mechanism for financing global sustainable development [

21]. Ref. [

6] (p. 29) argues that long-maturity climate bonds provide “an immediately implementable opportunity” for significant climate mitigation. Rising interest in corporate GBs further reflects the growing weight of ESG criteria in investment decisions, with strong ESG performance enhancing access to finance [

7,

39].

Investor behavior in GB markets is characterized by buy-and-hold strategies, linked to liquidity premiums compensating for maturity risks [

40]. This contributes to price stability and lower volatility [

41]. European mutual and pension funds show particular preference for GB, holding larger shares and exhibiting lower price sensitivity [

42].

Investment levels are shaped by bond features, issuer characteristics, and market conditions [

43]. Substantial disparities in bond ratings reflect heterogeneous risk perceptions, influencing issuance volumes. While GB popularity has grown, average issue size has not increased, pointing to wider participation without proportional capital growth [

43]. Key drivers of larger issuances include coupon rates, credit ratings, collateral, issuer health, and tax incentives [

32,

44].

Nonetheless, the GB market faces structural challenges beyond greenwashing, such as high issuance costs, procedural complexity, and supply-demand mismatches with conventional bonds [

18,

45]. Bracking [

46] (p. 13) emphasizes that despite expectations, the “revolutionary growth in GB (…) has not materialized,” citing volatility and systemic weaknesses. Similarly, Bracking et al. (2023) [

47] argues that balancing environmental and financial objectives is deeply tied to broader socio-economic institutions. In developing countries, additional barriers include weak institutional frameworks, minimum size requirements, and high transaction costs [

28].

3.1.2. Spillovers

Flammer [

7] compares GB and non-GB issuers, finding stronger ESG ratings, profitability, and market valuations for GB firms. Ref. [

9] also concludes that while both bond types enhance performance, GBs have a more significant impact. Green bond issuance improves corporate metrics: within three years, EBITDA/Assets rise by 7.3 basis points, and a 10% increase in GB share in total debt adds 1–3 bp [

9]. However, ref. [

48] notes that firm performance does not necessarily influence issuance decisions.

Market studies reveal mixed reactions. Refs. [

3,

8,

49] find positive abnormal returns around announcements, supported by [

50], who link GBs to stronger ESG ratings and investor appeal. Conversely, Lebelle et al. [

51] and Wu [

52] report negative abnormal returns (−0.5% to −0.2%), particularly in developed markets. Wu [

52] and Jakubik & Uguz [

53] also suggest lower equity returns post-issuance. Yet, Bagnoli & Watts [

54] argue that GBs benefit firms in less competitive markets by capturing consumer willingness to pay for socially responsible products. Overall, Ahmed et al. (2023) [

55] reaffirm predominantly favorable market responses.

GBs are also valued as stabilizing assets. They show positive correlations with climate risk indices [

56] and serve as safe havens during uncertainty [

57,

58,

59]. Mezghani et al. [

60] demonstrate their diversification benefits, outperforming traditional hedges such as gold and Brent. Portfolio studies confirm that including GBs enhances risk management and hedging effectiveness [

1,

58,

61,

62].

For issuers, GBs reduce financing costs and expand access to capital. Larger firms are more likely to issue them [

48], and advantages extend into secondary markets [

26,

63]. Key drivers include reputational benefits, climate commitments, and eco-innovation [

45,

64]. Despite higher issuance costs, issuers view them as justified [

65]. Governments further support adoption through tax incentives, subsidies, and tax-exempt bonds, with dynamic indexed incentives proving most effective [

66].

Table A1 (see

Appendix A) details these mechanisms.

Finally, Agliardi & Agliardi [

13] highlights green securitization as an innovative tool for managing climate risks and strengthening sustainable finance institutions, underscoring its potential in advancing resilient, mission-aligned financing.

3.1.3. Liquidity and Volatility

Febi et al. [

67] (p. 53) observes a declining impact of liquidity risk over time, suggesting market maturation: “Overall, however, the impact of LOT decreases over time, implying that, nowadays, liquidity risk is negligible for GB”. This trend indicates reduced investor concerns over liquidity, a key determinant of GB investment behavior [

40]. Still, risk perception rises during downturns, discouraging issuance and investment [

68].

Despite these improvements, liquidity concerns persist. Studies report significant volatility clustering and spillovers between GB and other markets [

31,

41,

62,

69]. Ref. [

31] (p. 263) notes “an upward trend in the correlation of volatility in the labelled green bond segment with the conventional bond market,” implying convergence as the GB market diversifies. Ferrer et al. [

70] similarly finds GB performance to be closely aligned with Treasuries and investment-grade corporate bonds, while ref. [

2] stresses the influence of investor sentiment, interest rates, and economic stability.

Geopolitical risks also shape GB markets. Sohag et al. [

71] show heightened sensitivity during bullish conditions, while ref. [

72] finds GBs may be more vulnerable to contagion. Tang et al. [

73] report short-term declines in response to U.S. policy uncertainty and geopolitical acts but positive reactions to rising geopolitical threats. Liu et al. (2024) [

74] views GBs as potential hedging assets, though high geopolitical risks depress prices. Broader uncertainty, especially economic policy shocks, significantly affects GB returns [

75,

76,

77,

78].

COVID-19 further highlighted market dynamics. Perote et al. (2023) [

79] shows non-linear effects, with low cases boosting and high cases reducing GB returns). Arat et al. [

80] & Giovanardi et al. [

81] report a negative pre-pandemic greenium of ~1.5–1.6 bps, which widened to 3.5 bps during the pandemic, reflecting GB outperformance in stressed markets. Evidence shows GBs offered greater resilience and stability compared to conventional bonds during the pandemic, supporting their role as safer assets [

30,

82]. Post-pandemic growth in GB issuance underscores their increasing appeal.

Table A2 (see

Appendix A) summarizes findings on GB liquidity and volatility.

3.2. Green Banking Loans

3.2.1. Definition and Trends

Green banking refers to practices that integrate environmental considerations into banking operations [

4,

5,

16,

83,

84], emphasizing the sector’s role in supporting sustainable development and managing environmental risks [

85]. A distinction must be made between green loans and green banking loans (GBLs): while green loans broadly finance environmentally friendly projects, GBLs are specifically offered by commercial banks, adding credibility through rigorous assessment [

86].

Financial institutions provide GBLs to fund sustainable projects that comply with environmental standards, thereby facilitating the global transition to a low-carbon economy [

16,

87,

88]. Their adoption is strongly influenced by “green values,” where altruism and environmental awareness drive uptake [

89] (p. 12). Structurally, GBLs often feature fewer covenants, higher collateralization, and longer maturities, which improve performance, though larger syndicates may reduce profitability [

17,

90].

Standardization of green banking disclosure is increasing, making reporting a routine practice for commercial banks [

34,

91]. The Paris Agreement further reinforced this trend, with green banks offering more favorable terms to sustainable firms only after its adoption [

17].

Technology and trust also shape green banking uptake. Trust in digital platforms and personal innovativeness encourage adoption [

89], while financial literacy and individual financial well-being remain barriers. Regional banks, despite their potential role in promoting SME sustainability, often lack expertise and resources to assess environmental impacts effectively [

92].

3.2.2. Spillovers

Green banking sustains the green economy by financing environmentally friendly enterprises [

93]. It promotes eco-innovation in SMEs [

94] and enhances banks’ financial stability by reducing default risks when environmental criteria guide lending [

16]. Empirical evidence shows a positive link between green banking performance, cost efficiency, and profitability [

15]. Green disclosures also increase firm value, though high non-performing loans may offset this effect [

95].

Spillovers extend to borrowers: green banks provide cheaper loans to green firms, especially after the Paris Agreement [

17], reinforcing the “green meets green” effect [

96]. Aligning green services with customer expectations strengthens reliability and responsiveness [

97]. Green practices also shape trust and loyalty by enhancing banks’ green image [

98].

Table A3 (see

Appendix A) summarizes the main findings of the literature about GBLs, trends and spillovers.

At the systemic level, climate stress tests are recommended to assess resilience of financial institutions, as underpricing climate-transition risks may generate systemic vulnerabilities [

21].

3.3. Greenium

The greenium—a blend of green and premium—refers to the yield discount of green financial instruments (bonds and loans) compared to conventional ones. It reflects growing demand for sustainable investments and incentivizes the issuance of green bonds (GB) and green bank loans (GBLs).

3.3.1. Is There Such a Thing as Greenium?

Evidence is mixed. Some studies confirm a positive premium [

38,

99], while others report no significant differences [

7,

100]. Green bond issuance can lower funding costs: 3–8 bp [

101], 63 bp [

102], 18 bp [

26], and 68–81 bp for German sovereign GBs [

103]. Certain markets show larger premiums, e.g., China [

104].

Conversely, some findings indicate a negative premium linked to green risk [

21] or diminishing returns over time [

105,

106]. GB fund performance remains inconsistent [

107]. Public and multilateral-backed GBs reduce risks and volatility [

108], while government GBs may trade at wider spreads [

27]. Non-linear estimations suggest the greenium increases with higher spreads of conventional bonds [

109].

Overall, the benefit of GB issuance may rely more on signaling environmental commitment than on direct financing advantages [

101].

For loans, Pohl et al. [

110] shows that GBLs exhibit a greenium, particularly when borrowers have strong ESG profiles and syndicates maintain high environmental standards.

Additionally, the pricing of GBLs is influenced by the ESG characteristics of the lending syndicate. Loans issued by syndicates with high environmental scores offer more favourable terms, underscoring the growing importance of environmental considerations in financial decisions”. The greenium literature is summarized in

Table A4 (see

Appendix A).

3.3.2. Greenium Factors

The greenium varies across issuers and bond characteristics. Hachenberg & Schiereck [

27] found that AA–BBB-rated GB trade marginally tighter than comparable non-GB. ESG scores negatively correlate with yields, suggesting stronger ESG practices lower financing costs [

111,

112,

113]. Higher ratings also enhance market response [

114].

Greenness assessments, such as second-party opinions (SPOs), increase liquidity [

81,

115], with external reviews reducing asymmetry and supporting yield advantages [

107,

116,

117]. Wu [

52], however, reports that certification may increase costs. A notable greenium emerged in 2019, linked to EU regulations and sustainable finance growth, especially for corporate and municipal issuers [

81,

101]. Demand pressures, such as oversubscription and GB index inclusion, reinforce lower borrowing costs [

42].

Issuer type also matters, as financial and corporate GBs trade tighter, while government-related GBs trade wider [

27,

51]. Supranational and corporate issuers show premiums, but financial institutions less so [

116]. GBs can mitigate country risk, serving as a cheaper source of capital for sovereign debt [

113].

Currency choice influences spreads: local-currency GBs trade tighter than foreign-currency ones [

101,

102]. Domestic bias strengthens European investors’ preference for local GBs [

42]. Traditional characteristics—issue size, maturity, currency—do not significantly affect pricing differentials [

27].

Market interconnections shape GB pricing. The GB market is influenced by fixed-income and FX markets but transmits negligible reverse spillovers, remaining weakly connected to equities, energy, and high-yield bonds [

1]. Shocks in conventional bond markets spill into GBs [

1,

31].

Differences arise between markets: first issuances show weaker investor response [

51]. The primary market displays little or no premium due to issuance processes, whereas the secondary market consistently reveals a greenium [

14,

38]. The greenium factors literature is summarized in

Table A5 (see

Appendix A).

3.4. Governance and Compliance

The expansion of GB and GBL markets has intensified scrutiny of their legal and policy frameworks [

118]. High demand risks diluting standards, potentially undermining environmental outcomes (green defaults) [

119]. Integrity has been strengthened by the ICMA’s Green Bond Principles (GBP), which set global standards for eligible projects [

1,

7,

26,

120]. National sustainability policies also drive issuance, highlighting the role of international frameworks in maintaining credibility [

64]. Reliable information significantly boosts GB investment [

84], reinforcing calls for clearer taxonomies and harmonized regulation [

45,

69].

Regulators play a critical role. The EBA integrates ESG into loan origination, risk management, and disclosure, requiring banks to assess environmental risks and borrower viability [

121]. The ECB incorporates climate risk into monetary policy and supervision, urging banks to perform climate stress tests [

122]. The FED has progressed more cautiously, focusing on research, interagency cooperation, and integrating climate risks into risk management frameworks [

123].

3.4.1. Adverse Selection: Greenwashing and Taxonomy

While GB issuance correlates with higher environmental scores, reduced CO

2 emissions, and stronger CSR practices [

7,

19], lack of harmonized standards creates adverse selection risks akin to Akerlof’s “lemons” problem [

18,

20]. Voluntary disclosure cannot reliably distinguish genuine GB, enabling mislabeling and misallocation [

20]. Greenwashing raises yields as investors demand a premium for risk [

112]. Certification can strengthen credibility but may also serve firms with weak ESG performance [

19]. Risks are higher in manufacturing than services [

112]. Clear criteria, such as the EU taxonomy, are vital to curb mislabeling and restore confidence [

124].

Banks must integrate ESG into credit operations [

16], supported by transparency and standardized reporting [

93]. CSR mechanisms such as sustainability reporting enhance accountability [

125], though internal committees often remain symbolic. Broader environmental policies are necessary, as central bank tools alone are insufficient [

4,

126,

127].

3.4.2. Policy Recommendations

Policies fostering GB/GBL issuance are widely endorsed [

13,

26,

43,

45,

71,

112,

113]. Effective measures include clear guidelines, certification, and transparency [

6,

84,

128]. Challenges persist as markets evolve [

37], requiring regulatory enforcement, audits, and costly disclosure regimes to deter mislabeling [

20,

21,

118].

Governance is key: disclosure depends more on governance scores than environmental ones [

111]. Larger boards and institutional ownership enhance green disclosure [

91], whereas independent directors have little effect. Robust governance frameworks improve transparency, reduce greenwashing, and ensure funds are allocated to genuinely sustainable projects [

18].

The literature relating to governance and compliance is summarized in

Table A6 (see

Appendix A).

This SLR consolidates research on GBs and GBLs as instruments for financing sustainable projects, their effectiveness in advancing environmental goals, and the role of international policies. It highlights key themes, trends, and implications for theory and practice, offering an integrative framework that identifies patterns, gaps, and inconsistencies in the literature.

Evidence shows that GB issuance correlates with higher environmental scores, lower CO

2 emissions, and continued sustainability efforts [

34], supporting stakeholder theory [

129,

130,

131]. GBs function not only as financial tools but also as strategies for corporate engagement [

7,

19], consistent with enlightened value maximization.

The greenium remains contested: some studies find a yield discount, while others suggest no premium [

38,

99]. These mixed results challenge market efficiency [

132] and call for refined models of ESG pricing. Still, GB issuance improves both environmental and financial performance [

8,

9], with the premium shaped by ESG scores, certification, market demand, issuer type, currency, and geography [

111,

112,

113].

Market growth is evident, but challenges persist—greenwashing, liquidity, and lack of harmonized standards. Liquidity has improved, yet returns remain sensitive to volatility, geopolitics, and policy uncertainty [

40,

67,

68,

71,

72,

73]. Calls for stronger certification and third-party verification are widespread [

20,

111]. Investor demand for ESG-aligned instruments is growing [

42,

133], and alignment with international frameworks is essential for credibility [

45,

69].

Governance and regulation remain central. Institutional theory [

134,

135,

136] underscores the role of frameworks such as GBP and GLP in ensuring transparency and market stability [

64,

119,

120]. Harmonization of standards and global coordination are crucial to reduce fragmentation and scale sustainable finance [

45,

69].

Investors and financial institutions increasingly integrate ESG factors in portfolio decisions [

61]. GBs and GBLs help align lending portfolios with sustainability goals, lowering default risks and improving performance [

9]. Transparency through standardized reporting strengthens confidence and stakeholder engagement [

93].

Methodologically, most studies use empirical analyses of financial metrics (ROA, leverage, stock responses) to assess impacts [

3,

8,

9]. While these validate financial benefits, they also reveal a need for more longitudinal research to capture long-term effects.

4. Discussion

This SLR provides an integrative synthesis of literature on green bonds (GB) and green banking loans (GBLs), highlighting their evolution, determinants, and impacts within the broader field of sustainable finance. The evidence confirms that both instruments have become increasingly important in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy, yet their diffusion, market depth, and regulatory maturity differ markedly across regions and sectors.

A key finding is the asymmetry in maturity and institutionalization between GBs and GBLs. GBs have achieved a higher level of market standardization, supported by legal and policy frameworks (e.g., GBP/GLP) and sovereign/multilateral issuance that foster transparency and comparability. This finding is in line with literature (e.g., [

119,

120]). Their market infrastructure benefits from transparency mechanisms, credit ratings, and external verification that enhance investor confidence and liquidity. This is supported by literature [

111,

116,

117]. In contrast, GBLs remain largely embedded in relationship-based intermediation and depend strongly on banks’ internal ESG integration practices [

15,

16,

83,

84].

Both instruments share similar objectives—mobilizing capital towards environmentally sustainable projects—but they operate through distinct transmission mechanisms. GBs channel funds via capital markets and deliver reputational/signaling benefits to issuers [

7,

8], while a GBL functions through direct credit allocation, embedding sustainability criteria within loan origination and monitoring processes [

16].

Across the reviewed studies, the financial impact of issuing or obtaining green finance remains heterogeneous. For GB, evidence of a greenium emerges in several markets, with documented discounts in primary or secondary markets and particularly in Europe and China [

10,

101,

102,

103,

104]. However, other studies [

52,

100] find no significant price differential once risk and payoff are equal or even report higher costs in some settings. Overall, the presence of a greenium appears contingent upon certification/verification quality, issuer reputation and credit quality, and market liquidity [

14,

51,

111,

114,

116,

117]. This mixed evidence is consistent with the coexistence of economic and behavioral drivers—some investors accept lower returns for environmental benefits while others demand full risk-adjusted compensation [

10,

38].

For GBLs, empirical work shows that borrowers with stronger ESG credentials and transparency benefit from lower loan spreads and more favorable conditions, confirming the ‘green meets green’ hypothesis [

17]. Banks with higher environmental scores or robust ESG policies tend to offer preferential rates, reflecting lower perceived credit risk and alignment with regulatory expectations [

15,

16]. However, GBL markets remain less developed than GBs markets, limiting cross-country comparability and statistical robustness [

83,

84].

The regional distribution of studies underscores significant geographical disparities. Europe leads in both issuance and research, reflecting the strength of its regulatory framework and the EU’s proactive stance in developing taxonomies, disclosure requirements, and green bond standards [

120,

121,

122,

124]. North America, while hosting large-scale corporate issues, shows more heterogeneity in adoption due to a fragmented regulatory environment. In Asia—particularly China—government support and state-owned financial institutions have accelerated market growth, although transparency and verification practices remain uneven [

104].

Beyond financial metrics, the reviewed studies reveal notable behavioral dimensions. Investors in GBs often display buy-and-hold preferences and lower price sensitivity, consistent with preferred-habitat demand among European mutual and pension funds [

42]. This behavior can enhance price stability but may also reduce secondary-market liquidity [

40,

41]. For banks, green lending fosters reputational benefits and institutional legitimacy, strengthening their strategic positioning within the sustainability agenda [

16,

93].

Several studies document increasing spillovers between green and conventional financial markets, particularly in volatility and pricing co-movements. The GB market is tightly linked to Treasuries and investment-grade bonds and is influenced by shocks from conventional bond markets [

1,

31,

41,

69,

70]. Geopolitical and policy-uncertainty shocks also matter, with effects varying across horizons [

71,

72,

73]. During the COVID-19 period, GBs tended to outperform comparable benchmarks, offering partial safe-haven properties and widening premia in stressed markets [

30,

79,

80,

82].

At the systemic level, the expansion of green lending can contribute to financial resilience by aligning credit risk with environmental performance—banks with greener portfolios tend to exhibit lower defaults and improved long-term stability [

15,

16]. Nonetheless, macro-prudential frameworks still lack climate-sensitive risk weights or capital buffers that would fully internalize environmental externalities [

122].

5. Conclusions

This review compares GBs and GBLs through a capital-structure and intermediation lens. Common drivers—issuer quality, credible external review, and taxonomy alignment—support issuance and, in some contexts, modest pricing benefits. Channels differ: GBs scale labelled finance via liquid public markets, benchmark eligibility and secondary-market liquidity; GBLs embed sustainability into lending relationships through measurable sustainability performance targets (SPTs), ongoing monitoring and covenant design. Pricing evidence is mixed and context-dependent: in bonds, any greenium is small and more persistent when disclosure and assurance are strong; in loans, benefits arise mainly through ratchet mechanics tied to ambitious, verified SPTs. Financial performance is not systematically inferior when governance and project evaluation are robust.

The implications are as follows. Issuers should match instrument choice to project pipelines, reporting capacity and desired depth of engagement with investors or lenders. Banks can operate transition plans and portfolio steering by standardizing SPT ambition, verification frequency and fallback mechanics in bilateral and syndicated deals. Investors should prioritize framework integrity, use-of-proceeds traceability and comparable impact metrics; long-horizon asset owners seeking influence may allocate to co-lending or private credit mandates, accepting lower liquidity.

This SLR has limits. Database and language coverage may under-represent non-English and practitioner work. Heterogeneity of research designs, time windows and outcome measures constrains comparability and precludes formal meta-analysis and study-level risk-of-bias scoring. Given the heterogeneity of methods and the absence of a unified RoB appraisal, our statements prioritize robust regularities and avoid causal claims where identification is weak. Publication bias towards statistically significant pricing results may persist. Rapid regulatory change—taxonomies and assurance standards—also means earlier findings may not generalize to current settings.

Future research should harmonize definitions and measurement of green premia across bonds and loans, including realized margins net of ratchets; exploit regulatory or disclosure shocks to identify signaling versus monitoring channels; link instrument choice to decarbonization outcomes and capex efficiency; and expand micro-data on SPT ambition, verification and covenant enforcement, especially for SMEs and emerging markets.

Overall, GBs and GBLs are complementary; convergent standards and interoperable data are pivotal for market integrity, cost of capital and real-economy impact.

Author Contributions

The main contributions of the authors are as follows: Conceptualization, J.P. and P.A.; Data curation, P.A.; Formal analysis, L.P. and P.A.; Investigation, J.P., L.P. and P.A.; Methodology, M.M., P.A. and T.B.; Project administration, J.P. and P.A.; Supervision, J.P. and P.A.; Validation, J.P. and P.A.; Visualization, M.M. and P.A.; Writing—original draft, P.A. and T.B.; Writing—review & editing, P.A. and T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financed by portuguese national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, under the project UID/05422/2025: Centre for Organisational and Social Studies of Polytechnic of Porto.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available with the authors and may be shared if requested.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT5 for the purpose of reviewing and improving English. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GBs | Green Bonds |

| GBLs | Green Banking Loans |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| S&P | Standard & Poor’s |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| EBITDA | Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization |

| APC | Article Processing Charge |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| GBP | Green Bond Principles |

| GLP | Green Loan Principles |

| EBA | European Banking Authority |

| ECB | European Central Bank |

| FED | Federal Reserve System |

| EU | European Union |

| FX | Foreign Exchange |

| bp | Basis Points (1 bp = 0.01%) |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Summary of main findings of literature about GB trends and spillovers.

Table A1.

Summary of main findings of literature about GB trends and spillovers.

| Paper | Research Design | Main Results/Conclusions |

|---|

| [54] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs advantageous in less competitive markets, helping cover socially responsible costs. |

| [49] | Empirical (quant.) | Positive abnormal returns after GB announcements; higher coupons negative; firm size, Tobin’s Q, and growth positive. |

| [43] | Empirical (quant.) | Issuance influenced by bond traits, issuer characteristics, and market conditions; effects vary across ratings. |

| [44] | Empirical (quant.) | Larger GBs linked to coupon, rating, collateral, issuer stability; emerging markets (esp. euro) attract more. |

| [26] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs lower issuers’ annual interest by ~18 bp, strongest for corporates in environmental sectors. |

| [137] | Conceptual | Assesses GBs as ethical finance, questioning measurable ethical value. |

| [9] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs improve corporate metrics (ROA, ROE, EBITDA/Assets); stronger short-term impact than traditional bonds. |

| [53] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs and green funds positively priced, but policies show mixed equity impacts. |

| [51] | Empirical (quant.) | Negative stock reactions (−0.5% to −0.2%), stronger at first issuance; skepticism across sectors. |

| [1] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs tightly integrated with treasury & corporate bonds; weak ties to stocks, energy, high-yield. |

| [1] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs linked to fixed-income & FX markets; little reverse spillover; weak stock/energy ties. |

| [13] | Conceptual | Green securitization can hedge climate risks, supporting sustainable finance. |

| [117] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs correlate with climate risk indices, improve hedging in uncertain periods. |

| [7] | Empirical (quant.) | Corporate GBs boost stock performance, attract long-term ESG investors, and enhance environmental outcomes. |

| [3] | Empirical (quant.) | GB issuance raises stock prices; short-term abnormal returns; supports long-term sustainability strategy. |

| [2] | Empirical (mixed) | Investor sentiment on social media correlates with GB index returns; lack of standards reduces confidence. |

| [138] | Empirical (quant.) | Project traits and ESG commitment drive GB performance; country factors matter. |

| [57] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs hedge effectively during calm phases and COVID-19, improving resilience. |

| [66] | Empirical (quant.) | Incentives (tax credits, subsidies) critical for GB attractiveness; indexed incentives preferred. |

| [50] | Empirical (qual.) | GBs fund green projects, improve ESG goals; challenges include investor risk aversion; calls for clearer guidelines. |

| [58] | Empirical (qual.) | GBs correlate positively with climate risks; improve risk-adjusted returns in uncertainty. |

| [35] | Empirical (quant.) | ESG disclosure, not brand reputation alone, drives successful issuance. |

| [41] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs attract long-term investors; diversification and regulation shape strategies. |

| [62] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs show spillovers with stock, energy, commodity volatilities; dynamic hedging needed. |

| [2] | Empirical (quant.) | Twitter sentiment affects GB returns; sentiment key in evolving niche market. |

| [52] | Empirical (quant.) | No significant negative premium in China/global; Yuan issuance reduces premium; certification may raise costs. |

| [55] | Empirical (qual.) | GB announcements yield positive abnormal stock returns; key for SDG financing. |

| [56] | Empirical (quant.) | GB indices don’t outperform market; crude oil strongly impacts returns. |

| [63] | Empirical (mixed) | Smaller banks issue GBs persistently; frequent issuers improve ESG scores and reduce polluting loans. |

| [36] | Conceptual | Blue bond market constrained by lack of standards/metrics; risk of “bluewashing.” |

| [39] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs enhance corporate performance via R&D, green innovation, and signalling. |

| [64] | Empirical (quant.) | Eco-innovative and policy-driven firms more likely to issue; transparency effects mixed. |

| [59] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs provide diversification, safe-haven, and hedging, esp. during COVID-19. |

| [48] | Empirical (quant.) | Larger firms, capitalization, and market size drive issuance; liquidity effect insignificant. |

| [139] | Empirical (quant.) | Repeated issuers reduce CO2 and improve efficiency; long-term performance stronger. |

| [60] | Empirical (quant.) | Gold drives GB shocks; GBs effective for diversification and hedging. |

| [34] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs lower emissions, raise renewable use, advance ESG—but require institutional quality. |

| [45] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs offer reputational benefits; barriers: immaturity, awareness, lack of projects; call for standardization. |

| [61] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs weakly linked to systemic factors; sustainability investors can use factor returns strategically. |

| [83] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs encourage green consumption, restructure industries, and foster eco-friendly growth. |

| [32] | Empirical (quant.) | ESG ratings, credit ratings, tax incentives, and awareness drive GB investments. |

| [140] | Empirical (quant.) | GB issuers face higher financial constraints, intensified post-first issuance. |

| [37] | Empirical (qual.) | GB research highlights role in climate action, sustainable finance, and financial markets. |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Summary of main findings of literature about GB liquidity and volatility.

Table A2.

Summary of main findings of literature about GB liquidity and volatility.

| Paper | Research Design | Main Results/Conclusions |

|---|

| [31] | Empirical (quant.) | Volatility clusters in GB; shocks from conventional bonds spill into GB, varying over time. |

| [67] | Empirical (quant.) | Liquidity risk explains GB yield spreads; impact declines over time; GBs more liquid than conventional bonds (2014–2016). |

| [141] | Empirical (quant.) | Investor attention plays a critical, time-varying role in GB market. |

| [30] | Empirical (qual.) | Despite COVID-19, issuance rose to USD 269.5bn, showing resilience. |

| [70] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs strongly connected to Treasuries & corporate bonds; limited distinctiveness as an asset class. |

| [127] | Empirical (quant.) | QE boosts GB issuance in Eurozone; liquidity (M3) also supports green investments. |

| [40] | Empirical (quant.) | GB liquidity premiums affected by instability & policy; investors prefer buy-and-hold strategies. |

| [82] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs more resilient to shocks; uptake rose post-pandemic. |

| [68] | Empirical (quant.) | Liquidity risks influence investor choice; issuance rises under stability and low risk. |

| [69] | Empirical (quant.) | Financial markets affect GB volatility; GBs more sensitive to positive shocks during COVID-19. |

| [71] | Empirical (quant.) | Geopolitical risks hurt GBs & green equity, especially in bullish markets. |

| [75] | Empirical (quant.) | Commodity & financial prices predict GB returns; speculation negative; markets strongly interconnected. |

| [76] | Empirical (quant.) | Green QE boosts sentiment in stable times; weaker during crises; effects nonlinear. |

| [80] | Empirical (quant.) | Pre-COVID greenium ~1.6 bp, widened to 3.5 bp during pandemic; transparency reduced asymmetry. |

| [81] | Empirical (quant.) | Greenness ratings raise liquidity & greenium; stronger in eco-friendly countries; GBs improve EBITDA/assets short term. |

| [79] | Empirical (quant.) | GB & ESG returns respond non-linearly to COVID-19 cases; lockdowns help, simultaneous measures harm. |

| [72] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs more sensitive to geopolitical risks than conventional bonds; corporate bonds exert stronger influence. |

| [73] | Empirical (quant.) | Short-term GB returns fall with USEPU & GPRA but rise with GPRT; long-term effects mostly negative. |

| [77] | Empirical (quant.) | Economic policy uncertainty positively impacts GB market efficiency. |

| [78] | Conceptual | Policy uncertainty strongly influences GB markets, especially during volatile periods. |

| [74] | Empirical (quant.) | Geopolitical risk positions GBs as hedges but may lower demand; rising prices could intensify energy conflicts. |

Appendix A.3

Table A3.

Summary of main findings of literature about GBL trends and spillovers.

Table A3.

Summary of main findings of literature about GBL trends and spillovers.

| Paper | Research Design | Main Results/Conclusions |

|---|

| [85] | Empirical (quant.) | Environmental uncertainty shapes hybrid organizations like green banks; strategies align with shifting resource environments. |

| [21] | Empirical (quant.) | Negative greenium: investors accept lower returns for greener firms. Transparency valued; climate stress tests recommended to mitigate systemic risks. |

| [5] | Empirical (qual.) | Literature categorized into ethical, product, and business domains; highlights governance, risk, and inclusion in sustainable banking. |

| [15] | Conceptual | Green banking improves financial performance via cost efficiency, but political ties weaken benefits through reputational risks. |

| [94] | Empirical (quant.) | GBLs drive renewable energy adoption and SME eco-innovation by reducing financial barriers. |

| [15] | Empirical (quant.) | Green disclosures raise bank firm value, but effects depend on managing non-performing loans. |

| [16] | Empirical (quant.) | More green exposure increases spreads, reduces defaults, and strengthens system resilience. |

| [90] | Empirical (quant.) | Higher GBLs lower profitability, raise moderate risks; collateral and loan duration improve performance. |

| [97] | Empirical (quant.) | Banks should align green services with customer needs; students in emerging economies show awareness, key for adoption. |

| [65] | Empirical (qual.) | Only 51 studies focus on green banking adoption; gaps in customer/employee perspectives and performance outcomes. |

| [98] | Empirical (quant.) | Green practices improve image and trust; loyalty depends mainly on strengthened green image, not trust. |

| [17] | Empirical (quant.) | Green banks provide cheaper, less restrictive loans to green firms—“green meets green” effect. |

| [92] | Empirical (qual.) | Regional banks overlook environmental aspects; integrating climate risk into SME lending needs local expertise. |

| [93] | Empirical (quant.) | Stakeholder knowledge gaps and weak disclosure limit green supply chains; awareness improves image and sustainability. |

| [89] | Empirical (qual.) | Altruism and green values drive adoption; green savings mediate; literacy and financial well-being may limit uptake. |

| [96] | Empirical (quant.) | ESG practices strengthen GBLs’ role in promoting sustainability. |

Appendix A.4

Table A4.

Summary of main findings of literature about greenium.

Table A4.

Summary of main findings of literature about greenium.

| Paper | Research Design | Main Results/Conclusions |

|---|

| [102] | Empirical (quant.) | GB trades at 63 bp premium vs. corporates; local currency bonds tighter than foreign; spreads widen with market risk and U.S. Treasury rates, tighten with GDP growth. |

| [99] | Conceptual | Mixed evidence on greenium; some investors pay more for societal benefits; others see no premium. Legal concerns stress third-party verification. |

| [105] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs offer positive but diminishing returns and lower risks; outperformance over conventional bonds is waning. |

| [100] | Empirical (quant.) | Green and non-green bonds priced identically when risk/payoff equal; no premium observed. |

| [107] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs often show greenium (lower yields), though fund/index performance is mixed; pricing influenced by issuer, project, and certifications. |

| [142] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs generally yield less, providing hedging benefits against climate risks and enhancing financial stability; premium varies with market and issuer traits. |

| [108] | Empirical (quant.) | Public/multilateral backing reduces GB risks and costs; long-maturity public GBs show lower yields and volatility. |

| [38] | Empirical (qual.) | Greenium confirmed in 56% of primary and 70% of secondary market studies; averages −1 to −9 bp in secondary market; influenced by issuer type, grade, and reporting. |

| [133] | Empirical (quant.) | Firms with ESG concerns show lower bondholder returns, especially in crises, due to higher default risk. |

| [104] | Empirical (quant.) | China’s GB market shows stronger greenium than global markets; driven by lower information asymmetry, regulation, and environmental awareness. |

| [103] | Empirical (quant.) | German government GBs show 68–81 bp greenium; higher rates increase greenium, uncertainty reduces it; lower liquidity partially offsets. |

| [106] | Empirical (quant.) | Green assets expected to underperform long-term; climate concerns raise green asset prices; German twin bonds confirm greenium. |

| [39] | Empirical (quant.) | Greenium grows non-linearly with higher non-GB spreads; credit spread and coupon differences explain variation. |

| [110] | Empirical (quant.) | GBLs priced lower than conventional loans, especially for high-ESG borrowers and syndicates; environmental factors drive favourable terms. |

Appendix A.5

Table A5.

Summary of main findings on greenium factors.

Table A5.

Summary of main findings on greenium factors.

| Paper | Research Design | Main Results/Conclusions |

|---|

| [102] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs trade at 63 bp premium; local currency tighter than foreign. Spreads widen with market risk and U.S. rates, tighten with GDP growth. |

| [99] | Conceptual | Evidence on greenium mixed: some pay for societal benefits, others see no premium. Highlights need for third-party verification. |

| [105] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs show positive but declining returns and risk advantage; outperformance over conventional bonds is fading. |

| [100] | Empirical (quant.) | Green and non-green bonds priced identically when risk/payoff equal; no premium detected. |

| [107] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs often show lower yields (greenium), though fund/index performance mixed; pricing shaped by issuer, project, and certifications. |

| [142] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs generally yield less, offering hedging benefits and stability. Premium varies by issuer and market. |

| [108] | Empirical (quant.) | Public/multilateral backing lowers GB risk and cost; long-maturity public GBs show reduced yields and volatility. |

| [38] | Empirical (qual.) | Greenium confirmed in 56% of primary and 70% of secondary studies; −1 to −9 bp in secondary markets; driven by issuer type, rating, and governance. |

| [133] | Empirical (quant.) | Firms with ESG concerns yield lower bondholder returns, especially in crises, reflecting higher default risk. |

| [104] | Empirical (quant.) | Chinese GB market shows larger greenium than international, due to regulation, lower asymmetry, and environmental focus. |

| [103] | Empirical (quant.) | German GBs show 68–81 bp greenium; higher rates enlarge premium, uncertainty reduces it; lower liquidity partly offsets. |

| [106] | Empirical (quant.) | Green assets expected to underperform long-term, though climate concerns raise prices. German twin bonds confirm greenium. |

| [39] | Empirical (quant.) | Greenium increases non-linearly with non-GB spreads; credit and coupon differences explain variation. |

| [110] | Empirical (quant.) | GBLs priced lower than conventional loans, especially for high-ESG borrowers/syndicates, confirming environmental factors’ role. |

Appendix A.6

Table A6.

Summary of main findings of literature about governance and compliance.

Table A6.

Summary of main findings of literature about governance and compliance.

| Paper | Research Design | Main Results/Conclusions |

|---|

| [91] | Empirical (qual.) | Board size and institutional ownership raise green banking disclosure; no effect from independent directors. |

| [6] | Empirical (quant.) | GBs effective for climate mitigation if backed by regulation and reliable signals. |

| [28] | Conceptual | GB growth in developing nations hindered by institutional barriers, costs, and bond size; development banks can foster markets. |

| [143] | Empirical (quant.) | Transparent GB ratings enhance credibility, attract investors, and support market growth. |

| [124] | Conceptual | Transition finance depends on politics and markets; EU taxonomy guides but faces external challenges. |

| [18] | Conceptual | GBs lower debt costs and support sustainability; risks include weak standards and greenwashing; clear rules needed. |

| [4] | Empirical (qual.) | Asia-Pacific central banks promote sustainable finance via regulation, green loans, and climate integration. |

| [119] | Conceptual | Standards and certification build credibility; enforcement gaps remain. |

| [118] | Empirical (qual.) | Legal frameworks, interest rates, and stability key for GB markets. |

| [20] | Empirical (quant.) | GB market faces “lemons” problem; regulation, audits, and costly disclosure regimes recommended. |

| [120] | Empirical (quant.) | GBP improve transparency and policy alignment, shaping green finance globally. |

| [128] | Empirical (quant.) | Green finance improves environmental quality, effects vary by country; tailored policies required. |

| [20] | Empirical (quant.) | Voluntary disclosure worsens adverse selection; costly issuance fosters efficiency. |

| [51] | Empirical (quant.) | Better disclosure improves GB liquidity, esp. for non-financial, long-term, and lower-rated bonds. |

| [125] | Empirical (quant.) | ESG mechanisms shape green strategies; committees symbolic; ESG-linked pay may deter green financing. |

| [47] | Empirical (quant.) | Transition bonds sometimes preferred; uneven scientific evidence undermines GB credibility. |

| [64] | Empirical (quant.) | Reputation and strong-policy contexts drive issuance; mixed evidence on investor-driven issuance. |

| [126] | Empirical (quant.) | Green QE minimally reduces emissions; complementary reforms needed. |

| [19] | Empirical (quant.) | GB issuers show stronger ESG, governance, and CO2 cuts; weaker ESG firms rely on certification. |

| [46] | Empirical (quant.) | Questions GB’s transformative role; highlights lack of validation and fragility. |

| [84] | Empirical (quant.) | Certification boosts GB investment; greenwashing undermines trust; unified system essential. |

References

- Reboredo, J.C.; Ugolini, A.; Aiube, F.A.L. Network connectedness of green bonds and asset classes. Energy Econ. 2020, 86, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Chousa, J.; López-Cabarcos, M.; Caby, J.; Šević, A. The influence of investor sentiment on the green bond market. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 120351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborda, J.; Sánchez-Guerra, L. Green Bond Finance in Europe and the Stock Market Reaction. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2021, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, A.; Rosmin, M.; Volz, U. The role of central banks in scaling up sustainable finance—What do monetary authorities in the Asia-Pacific region think? J. Sustain. Finance Investig. 2020, 10, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aracil, E.; Nájera-Sánchez, J.J.; Forcadell, F.J. Sustainable banking: A literature review and integrative framework. Finance Res. Lett. 2021, 42, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, M.; Gevorkyan, A.; Radpour, S.; Semmler, W. Financing climate policies through climate bonds—A three stage model and empirics. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2017, 42, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate green bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.Y.; Zhang, Y. Do shareholders benefit from green bonds? J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 61, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agliardi, E.; Chechulin, V. Green Bonds vs. Regular Bonds: Debt Level and Corporate Performance. Korporativnye Finans. 2020, 14, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbib, O.D. The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: Evidence from green bonds. J. Bank. Financ. 2019, 98, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Bergstresser, D.; Serafeim, G.; Wurgler, J. Financing the Response to Climate Change: The Pricing and Ownership of U.S. Green Bonds; NBER Working Paper 25194; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, K.M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Is it Rewarded by the Corporate Bond Market? A Critical Note. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agliardi, E.; Agliardi, R. Corporate Green Bonds: Understanding the Greenium in a Two-Factor Structural Model. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2021, 80, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, C.; Romana, M.F. Practical Applications of Green Bond Pricing: The Search for Greenium. J. Altern. Investig. 2020, 22, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Khan, H.Z.; Monem, R.M. Does green banking performance pay off? Evidence from a unique regulatory setting in Bangladesh. Corp. Gov. 2021, 29, 162–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Mirza, N.; Huang, L.; Umar, M. Green Banking—Can Financial Institutions support green recovery? Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 75, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degryse, H.; Goncharenko, R.; Theunisz, C.; Vadasz, T. When green meets green. J. Corp. Financ. 2023, 78, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschryver, P.; de Mariz, F. What Future for the Green Bond Market? How Can Policymakers, Companies, and Investors Unlock the Potential of the Green Bond Market? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.J.; Herrero, B.; Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Del Mar Mirallles-Quirós, M. Exploring the determinants of corporate green bond issuance and its environmental implication: The role of corporate board. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 189, 122379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henide, K. Green lemons: Overcoming adverse selection in the green bond market. Transnatl. Corp. 2021, 28, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessi, L.; Ossola, E.; Panzica, R. What greenium matters in the stock market? The role of greenhouse gas emissions and environmental disclosures. J. Financ. Stab. 2021, 54, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D.A., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfrate, G.; Peri, M. The green advantage: Exploring the convenience of issuing green bonds. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachenberg, B.; Schiereck, D. Are green bonds priced differently from conventional bonds? J. Asset Manag. 2018, 19, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, J. The green bond market: A potential source of climate finance for developing countries. J. Sustain. Finance Investig. 2018, 9, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, R.; Singh, S. Sustainable finance: A systematic review. Int. J. Indian Cult. Bus. Manag. 2020, 21, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, M.; Chadha, G.; Prasad, R. Sustainable finance research: Review and agenda. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 29, 4010–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L. Is it risky to go green? A volatility analysis of the green bond market. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2016, 6, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, S.; Devi, S.L.T.; Mishra, A.K. Investing in our planet: Examining retail investors’ preference for green bond investment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 5151–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Capital Market Association (ICMA). Green Bond Principles, Voluntary Process Guidelines for Issuing Green Bonds; ICMA: Zürich, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Nguyen, N.M.; Luu, N.H.; Hoang, A.; Nguyen, M.T.N. Environmental impacts of green bonds in cross-countries analysis: A moderating effect of institutional quality. J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2023, 15, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.T.W.; Sharma, P.; Broadstock, D.C. Interactive effects of brand reputation and ESG on green bond issues: A sustainable development perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmans, P.; de Mariz, F. The Blue Bond Market: A Catalyst for Ocean and Water Financing. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, T.; Selama, A.I.; Nor, N.M.; Hassan, A.F.S. Meaningful Review of Existing Trends, Expansion, and Future Directions of Green Bond Research: A Bibliometric Approach. Stud. Univ. “Vasile Goldiş” Arad. Ser. Ştiinţe Econ. 2024, 34, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAskill, S.; Roca, E.; Liu, B.; Stewart, R.; Sahin, O. Is there a green premium in the green bond market? Systematic literature review revealing premium determinants. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, L.; Wu, N. The positive impact of green bond issuance on corporate ESG performance: From the perspective of environmental behavior. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 31, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutabba, M.A.; Rannou, Y. Investor strategies in the green bond market: The influence of liquidity risks, economic factors and clientele effects. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 81, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchiello, A.F.; Cotugno, M.; Monferrà, S.; Perdichizzi, S. Which are the factors influencing green bonds issuance? Evidence from the European bonds market. Finance Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boermans, M. Preferred habitat investors in the green bond market. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Chiesa, M. Sustainable financing practices through green bonds: What affects the funding size? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1131–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, M.; Barua, S. The surge of impact borrowing: The magnitude and determinants of green bond supply and its heterogeneity across markets. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2018, 9, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgi, I.; Schopohl, L. Explaining green bond issuance using survey evidence: Beyond the greenium. Br. Account. Rev. 2023, 55, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracking, S. Green bond market practices: Exploring the moral ‘balance’ of environmental and financial values. J. Cult. Econ. 2024, 17, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracking, S.; Borie, M.; Sim, G.; Temple, T. Turning investments green in bond markets: Qualification, devices and morality. Econ. Soc. 2023, 52, 626–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, J.; Ferreira, J.; Santibanez-González, E. Green finance sources in Iberian listed firms: A socially responsible investment approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulkaran, V. Stock market reaction to green bond issuance. J. Asset Manag. 2019, 20, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, U.S.; Tariq, A.; Farrukh, M.; Raza, A.; Iqbal, M.K. Green bonds for sustainable development: Review of literature on development and impact of green bonds. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]