Digital Transformation and New Quality Productivity in SMEs: Evidence of Corporate Managerial Ability in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Digital Transformation and New Quality Productivity

2.3. The Role of Managerial Ability in the Relationship Between Digital Transformation and New Quality Productivity

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Industry Technological Turbulence

2.5. The Moderating Effect of ESG Ratings

2.6. The Moderating Effect of Digital Intellectual Property Protection

3. Research Design

3.1. Regression Models

3.2. Definition of Variables

3.3. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Correlation Analysis

4.2. Regression Results

4.3. Robustness Tests

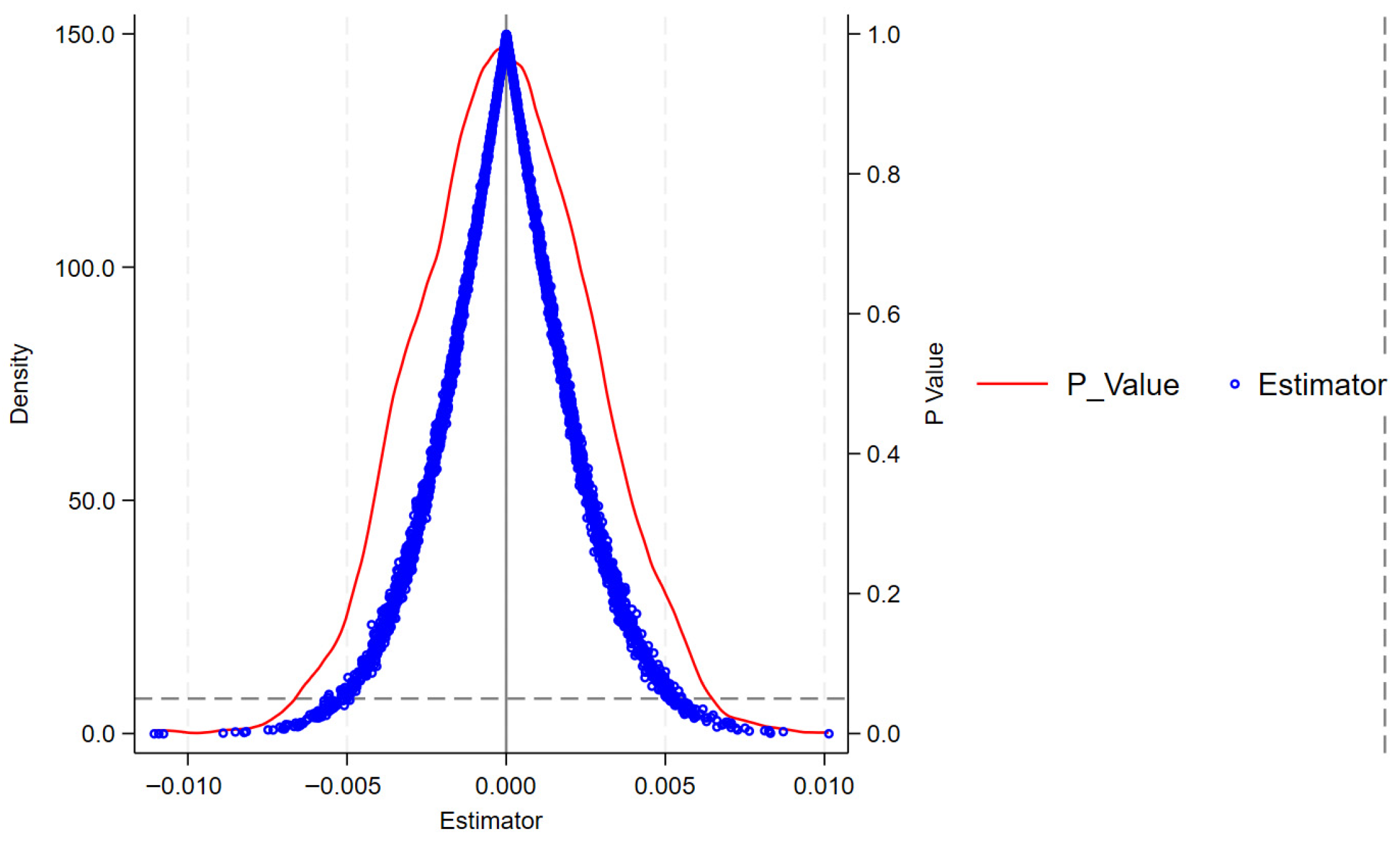

4.4. Endogeneity Test

4.5. Test for Mediating Effects of Managerial Ability

4.6. Test for Moderating Effects of Industry Technological Turbulence, ESG Ratings, and Digital Intellectual Property Protection

4.7. Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xi, J. Accelerating the Development of New Productive Forces and Promoting High-Quality Development. People Dly. 2024, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Jian, H.; Li, B. Does Digital Innovation Improve Carbon Productivity? A New Perspective Based on Industrial Upgrading. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lin, X.; Wang, T. The Impact of Digital Transformation Strategy and Capability on Product-Service Systems: Evidence from Foreign Economic and Management. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Z. Digital Transformation, Competitive Strategy Selection, and High-Quality Development of Enterprises: Evidence from Machine Learning and Text Analysis. Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Li, J. Does Enterprise Digital Transformation Enable New Quality Productivity Development? Micro Evidence from Chinese Listed Firms. Rev. Ind. Econ. 2024, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G. Digital Transformation and the Development of New Quality Productivity: Impact Mechanism and Empirical Testing. Econ. Probl. 2025, 7, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; An, H.; Yang, G. Digital Transformation and the Improvement of New Quality Productive Forces: An Empirical Study of Listed Chinese Enterprises. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2025, 42, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Digital Economy and High-Quality Development of Enterprises: Empirical Evidence Based on Total Factor Productivity. Reform 2022, 9, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wager, M. Building Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation: An Ongoing Process of Strategic Renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y. Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbaxani, V.; Dunkle, D. Gearing Up for Successful Digital Transformation. MIS Q. Exec. 2019, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, M.; Wang, Z. Enhancing the Core Competitiveness of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises with Digital Power. Macroecon. Manag. 2024, 6, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Zhan, R.; Zhao, F. The Measurement of New Quality Productivity and New Driving Force of the Chinese Economy. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2024, 41, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y. New Quality Productivity and Its Cultivation and Development. Econ. Dyn. 2024, 1, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, R. Index Construction and Spatiotemporal Evolution of New Quality Productivity. J. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 37, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, F. Digital Transformation and New Quality Productive Forces: A Perspective Based on Dynamic Capabilities. Financ. Res. 2024, 4, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, H. Digital Transformation and New Quality Productivity in the Chinese Path to Modernization: A Supply Chain Resilience Perspective. J. Hohai Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2024, 26, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; He, Z. Urban Digital Intelligence Development and Corporate New Quality Productive Forces: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on National AI Innovative Development Pilot Zones. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2025, 27, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banalieva Elizaveta, R.; Dhanaraj, C. Internalization Theory for the Digital Economy. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ni, Z.; Qiu, R. The Impact of Digital Transformation Rate on Total Factor Productivity: A Study Based on New Quality Productivity. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 45, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Lelarge, C.; Restrepo, P. Competing with Robots: Firm-Level Evidence from France. AEA Pap. Proc. 2020, 110, 26738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Pan, W.; Yuan, K. Digital Transformation and the Development of China’s Real Economy. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2022, 39, 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Yang, M. Persistent Innovation Effect of Digital Transformation. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2025, 42, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Ren, X. Digital Transformation and Capital Market Performance: Empirical Evidence from Stock Liquidity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144+10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Digital Economics. J. Econ. Lit. 2019, 57, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Yu, M.; Tan, K.H. Cooperative Innovation Behavior Based on Big Data. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, Z. From Digital Transformation to Green Innovation: A Study on the Causal Mediating Effects of the Environment. Sci. Sci. Manag. S.&T. 2026, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, D.R.; Hoskisson, R.E. Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases: Competitiveness and Globalization; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Luo, J.; Jiang, X.; Geng, X. Top Management Teams’ IT Background and Digital Transformation Strategy: A Cognitive Framework of Digital Strategy. Sci. Sci. Manag. S.&T. 2024, 45, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yu, R. How Does Digital Transformation Affect Corporate Risk-Taking? Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 97, 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chu, Z. Digitization Technology and Servitization Transformation Performance of Manufacturing Firms under Technological Turbulence: A Chain Mediation Model. Sci. Sci. Manag. S.&T. 2022, 43, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Xu, X. Knowledge Interdisciplinarity, Technological Turbulence, and Enterprise Core Technology Innovation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y. The Impact of ESG Development on New Quality Productive Forces of Enterprises: Empirical Evidence from Chinese A-Share Listed Companies. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2024, 46, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, H.; Wang, X.; Fang, H. Intellectual Property Administrative Protection and Enterprise Digital Transformation. Econ. Res. 2023, 58, 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. The Development of Methods and Models for Mediating Effects. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerjian, P.R.; Lev, B.; Lewis, M.F.; McVay, S.E. Managerial Ability and Earnings Quality. Account. Rev. 2013, 88, 463–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Zeng, D.; Qualls, W.J.; Li, J. Do social ties matter for the emergence of dominant design? The moderating roles of technological turbulence and IRP enforcement. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2018, 47, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Lian, Y. Estimation of Total Factor Productivity of Industrial Enterprises in China: 1999–2007. China Econ. Q. 2012, 11, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, H.; Long, Z.; Tang, X. Digital Transformation and the Geographic Distribution of Supply Chain. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2023, 40, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espina, E.M. Gaps in the Digital Transformation of Public Health in Latin America. Ceniiac 2025, 1, e0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First-Level Indicator | Second-Level Indicator | Third-Level Indicator | Indicator Description | Attributes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The elements of new quality productivity | New laborers | Staff quality | R&D personnel salary ratio | R&D personnel salary/operating revenue | + |

| R&D personnel quantity ratio | R&D personnel quantity/total number of employees | + | |||

| Management quality | Executives’ green cognition | ln(the frequency of keywords related to green development in the company’s annual report + 1) | + | ||

| CEO functional experience diversity | The count of CEO functional experience | + | |||

| New labor objects | New business | R&D depreciation and amortization ratio | R&D depreciation and amortization/operating revenue | + | |

| R&D lease fees ratio | R&D lease fees/operating revenue | + | |||

| New industries | Manufacturing costs ratio | CSMAR database | + | ||

| Whether the company belongs to strategic emerging industries | If the enterprise belongs to strategic emerging industries, the value is 1; otherwise it is 0 | + | |||

| New labor materials | Innovative technologies | Utility model patent quantity | ln(annual number of utility model patents + 1) | + | |

| Green technologies | Green invention patent quantity | ln(annual number of green invention patents + 1) | + | ||

| Green utility model patent quantity | ln(annual number of green utility model patents + 1) | + |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Symbols | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | New quality productivity | NQPi,t | Constructed indicators |

| Independent variable | Digital transformation | Digiti,t | Constructed indicators |

| Mediator variable | Managerial ability | MAi,t | Constructed indicators |

| Moderator variables. | Industry technological turbulence | TBi,t | Refer to Dai et al. [37] |

| ESG ratings | ESGi,t | Huazheng ESG rating data | |

| Digital intellectual property protection | IPi,t | Data from National Intellectual Property Administration | |

| Control Variables | Total asset size of the enterprise | Size | ln(the total assets of the enterprise) |

| Asset liability ratio | Lev | Liability/asset | |

| Return on equity | ROE | Net profit/average shareholder equity | |

| Cash flow | Cashflow | Net cash flow generated from operating activities/total assets | |

| Growth capability | Growth | Growth rate of operating revenue | |

| Property rights nature | SOE | State-owned enterprise’s value is 1; otherwise, it is 0 | |

| Ownership concentration | TOP | The top ten majority shareholding ratio | |

| Integration of the roles of Chairman and General Manager | Duality | The value of combining two positions is 1; otherwise, it is 0 | |

| Proportion of independent directors | Indep | Proportion of independent directors | |

| Corporate age | Age | ln(number of years since the company went public) | |

| Board size | Bsize | ln(number of board members) |

| Variables | Sample Size | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Median | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NQP | 17,620 | 0.0700 | 0.0400 | 0 | 0.0700 | 0.340 |

| Digit | 17,620 | 0.0900 | 0.0800 | 0 | 0.0600 | 0.500 |

| MA | 10,878 | 0.0200 | 0.150 | −0.470 | 0.0500 | 0.380 |

| Size | 17,620 | 21.84 | 0.980 | 19.97 | 21.73 | 26.36 |

| Lev | 17,620 | 0.370 | 0.190 | 0.0600 | 0.350 | 0.880 |

| ROE | 17,620 | 0.0500 | 0.140 | −0.730 | 0.0600 | 0.310 |

| Cashflow | 17,620 | 0.0500 | 0.0700 | −0.150 | 0.0400 | 0.240 |

| Growth | 17,620 | 0.180 | 0.370 | −0.540 | 0.120 | 2.240 |

| SOE | 17,620 | 0.820 | 0.380 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| TOP | 17,620 | 57.52 | 14.15 | 22.71 | 58.39 | 90.30 |

| Duality | 17,620 | 0.380 | 0.490 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Indep | 17,620 | 37.86 | 5.280 | 33.33 | 36.36 | 57.14 |

| Age | 17,620 | 1.570 | 0.800 | 0 | 1.790 | 3.220 |

| Bsize | 17,620 | 2.080 | 0.190 | 1.610 | 2.200 | 2.640 |

| NQP | Digit | Size | Lev | ROE | Cashflow | Growth | SOE | TOP | Duality | Indep | Age | Bsize | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NQP | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Digit | 0.392 *** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Size | 0.342 *** | 0.083 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Lev | 0.131 *** | −0.00600 | 0.438 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| ROE | 0.026 *** | −0.072 *** | 0.095 *** | −0.255 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Cashflow | 0.019 ** | −0.059 *** | 0.075 *** | −0.174 *** | 0.329 *** | 1 | |||||||

| Growth | 0.026 *** | −0.00400 | 0.091 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.290 *** | 0.031 *** | 1 | ||||||

| SOE | −0.046 *** | 0.017 ** | −0.130 *** | −0.113 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.0110 | 0.033 *** | 1 | |||||

| TOP | −0.138 *** | −0.163 *** | −0.057 *** | −0.147 *** | 0.240 *** | 0.095 *** | 0.112 *** | 0.048 *** | 1 | ||||

| Duality | 0.0120 | 0.084 *** | −0.086 *** | −0.069 *** | 0.00400 | −0.015 ** | 0.014 * | 0.191 *** | 0.025 *** | 1 | |||

| Indep | 0.016 ** | 0.083 *** | −0.045 *** | −0.028 *** | −0.027 *** | 0.00800 | −0.017 ** | 0.071 *** | 0.015 * | 0.132 *** | 1 | ||

| Age | 0.212 *** | 0.109 *** | 0.402 *** | 0.271 *** | −0.159 *** | 0.066 *** | −0.119 *** | −0.162 *** | −0.473 *** | −0.119 *** | 0.00600 | 1 | |

| Bsize | −0.00900 | −0.074 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.067 *** | 0.059 *** | 0.014 * | 0.034 *** | −0.181 *** | 0.00500 | −0.146 *** | −0.639 *** | 0.028 *** | 1 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+3 | |

| Digiti,t | 0.1353 *** | 0.1119 *** | 0.1060 *** | 0.0836 *** |

| (12.6105) | (12.3015) | (8.3116) | (7.6148) | |

| Size | 0.0116 *** | 0.0114 *** | ||

| (13.4721) | (11.2596) | |||

| Lev | 0.0025 | −0.0004 | ||

| (0.8764) | (−0.1182) | |||

| ROE | 0.0173 *** | 0.0251 *** | ||

| (6.5761) | (7.7570) | |||

| Cashflow | 0.0111 ** | 0.0199 *** | ||

| (2.2109) | (3.2483) | |||

| Growth | −0.0003 | 0.0022 ** | ||

| (−0.3418) | (2.2522) | |||

| SOE | −0.0051 *** | −0.0064 *** | ||

| (−3.2678) | (−3.2368) | |||

| TOP | −0.0000 | −0.0000 | ||

| (−1.0781) | (−0.6960) | |||

| Duality | 0.0015 | 0.0022 * | ||

| (1.5091) | (1.7974) | |||

| Indep | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | ||

| (−0.8393) | (−0.6471) | |||

| Age | −0.0006 | −0.0004 | ||

| (−0.9448) | (−0.4659) | |||

| Bsize | 0.0023 | 0.0032 | ||

| (0.7310) | (0.7951) | |||

| _cons | −0.0059 *** | −0.2413 *** | 0.0449 *** | −0.1930 *** |

| (−2.7181) | (−11.6722) | (6.0917) | (−7.7131) | |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 14,855 | 14,855 | 10,854 | 10,854 |

| adj. R2 | 0.3980 | 0.4790 | 0.3292 | 0.4122 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City-Level Clustering | Industry-Level Clustering | Excluding Certain Industries | ||||||||

| Variables | TFPi,t+1 | TFPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 |

| Digiti,t | 0.5311 *** | 0.4286 *** | 0.1119 *** | 0.0836 *** | 0.1119 *** | 0.0836 *** | 0.1150 *** | 0.0864 *** | ||

| (7.4256) | (4.4621) | (13.0521) | (7.7910) | (11.0587) | (7.7942) | (10.2013) | (6.4082) | |||

| Digit_2i,t | 0.0936 *** | 0.0765 *** | ||||||||

| (26.1549) | (17.7925) | |||||||||

| _cons | −2.9601 *** | −2.5561 *** | −0.2619 *** | −0.2141 *** | −0.2413 *** | −0.1930 *** | −0.2413 *** | −0.1930 *** | −0.2185 *** | −0.1569 *** |

| (−19.3651) | (−13.0970) | (−28.2704) | (−18.0857) | (−13.3366) | (−9.1087) | (−9.1135) | (−6.5627) | (−8.8818) | (−5.4639) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 14,701 | 10,753 | 14,538 | 10,547 | 14,855 | 10,854 | 14,855 | 10,854 | 11,183 | 8233 |

| adj. R2 | 0.6026 | 0.5284 | 0.4732 | 0.4056 | 0.4790 | 0.4122 | 0.4790 | 0.4122 | 0.4719 | 0.4023 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NQPi,t+1 | Digiti,t | NQPi,t+1 | ||

| Mean_Digit | 15.0446 *** | |||

| (16.50) | ||||

| Digiti,t | 0.1276 *** | 0.6597 *** | ||

| (30.24) | (3.73) | |||

| BroadBand | 0.0041 *** | |||

| (4.00) | ||||

| IMR | −0.4960 ** | |||

| (−2.74) | ||||

| _cons | −3.2965 *** | −0.0901 * | ||

| (−10.16) | (−1.66) | |||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kleibergen-Paap rk LM | 16.088 [0.0001] | |||

| Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F | 16.009 {8.96} | |||

| N | 17,620 | 17,315 | 17,315 | 17,315 |

| adj. R2 | 0.0606 | 0.5013 | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MA | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | |

| Digit | 0.1242 *** | 0.1041 *** | 0.0794 *** |

| (3.5337) | (9.4005) | (7.2476) | |

| MA | 0.0422 *** | 0.0345 *** | |

| (10.3671) | (8.1317) | ||

| _cons | −0.2039 ** | −0.2120 *** | −0.1931 *** |

| (−2.4771) | (−8.1349) | (−7.6599) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 10,596 | 10,308 | 10,294 |

| adj. R2 | 0.3644 | 0.4819 | 0.4007 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBi,t | ESGi,t | IPPi,t | ||||||

| NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | |

| Digiti,t | 0.1119 *** | 0.0836 *** | 0.1090 *** | 0.0834 *** | 0.1108 *** | 0.0851 *** | 0.1420 *** | 0.0828 *** |

| (12.3015) | (7.6148) | (0.0061) | (0.0059) | (0.0045) | (0.0056) | (0.0042) | (0.0050) | |

| TBi,t | 0.0051 | 0.0305 *** | ||||||

| (0.0097) | (0.0096) | |||||||

| Digiti,t × TBi,t | 0.2795 *** | 0.1950 ** | ||||||

| (0.0820) | (0.0817) | |||||||

| ESGi,t | 0.0829 *** | 0.0670 *** | ||||||

| (0.0054) | (0.0058) | |||||||

| Digiti,t×ESGi,t | 0.4320 *** | 0.4221 *** | ||||||

| (0.0658) | (0.0690) | |||||||

| IPPi,t | 0.0227 *** | 0.0197 *** | ||||||

| (0.0024) | (0.0031) | |||||||

| Digiti,t×IPPi,t | 0.0958 *** | 0.0173 * | ||||||

| (0.0348) | (0.0432) | |||||||

| _cons | −0.2413 *** | −0.1930 *** | −0.2010 *** | −0.1876 *** | −0.2121 *** | −0.1670 *** | −0.1902 *** | −0.1702 *** |

| (−11.6722) | (−7.7131) | (0.0127) | (0.0126) | (0.0091) | (0.0117) | (0.0086) | (0.0102) | |

| N | 14,855 | 10,854 | 9882 | 9865 | 14,855 | 10,854 | 14,801 | 10,810 |

| adj. R2 | 0.4790 | 0.4122 | 0.4565 | 0.3853 | 0.4895 | 0.4211 | 0.3991 | 0.3317 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | ||

| Lower Level of Industry Competition | Higher Level of Industry Competition | Lower Level of Industry Competition | Higher Level of Industry Competition | |

| Digit | 0.1085 *** | 0.1159 *** | 0.0819 *** | 0.0865 *** |

| (0.0066) | (0.0064) | (0.0086) | (0.0076) | |

| _cons | −0.2296 *** | −0.1723 *** | −0.2192 *** | −0.1682 *** |

| (0.0125) | (0.0131) | (0.0168) | (0.0161) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 6845 | 7648 | 4552 | 6026 |

| adj. R2 | 0.4718 | 0.4831 | 0.4116 | 0.4129 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | NQPi,t+1 | NQPi,t+3 | ||||

| Non-High-Tech Enterprises | High-Tech Enterprises | Non-High-Tech Enterprises | High-Tech Enterprises | Non-SRDI Enterprise | SRDI Enterprise | Non-SRDI Enterprise | SRDI Enterprise | |

| Digit | 0.1092 *** | 0.1194 *** | 0.0825 *** | 0.0869 *** | 0.1058 *** | 0.1219 *** | 0.0790 *** | 0.0948 *** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0094) | (0.0063) | (0.0120) | (0.0059) | (0.0073) | (0.0071) | (0.0092) | |

| _cons | −0.2490 *** | −0.2317 *** | −0.2008 *** | −0.2283 *** | −0.2311 *** | −0.2134 *** | −0.1848 *** | −0.2075 *** |

| (0.0102) | (0.0210) | (0.0133) | (0.0273) | (0.0113) | (0.0157) | (0.0142) | (0.0204) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 11,907 | 2903 | 8692 | 2128 | 8997 | 5813 | 6659 | 4161 |

| adj. R2 | 0.4840 | 0.4945 | 0.4184 | 0.4244 | 0.4907 | 0.4538 | 0.4191 | 0.3878 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, J.; Yang, D. Digital Transformation and New Quality Productivity in SMEs: Evidence of Corporate Managerial Ability in China. Sustainability 2026, 18, 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020883

Song J, Yang D. Digital Transformation and New Quality Productivity in SMEs: Evidence of Corporate Managerial Ability in China. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020883

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Jia, and Decai Yang. 2026. "Digital Transformation and New Quality Productivity in SMEs: Evidence of Corporate Managerial Ability in China" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020883

APA StyleSong, J., & Yang, D. (2026). Digital Transformation and New Quality Productivity in SMEs: Evidence of Corporate Managerial Ability in China. Sustainability, 18(2), 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020883

_Li.png)