Abstract

This study explores the relationship between board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in explaining the financial performance of firms listed on the Lima Stock Exchange during 2022–2023, using 242 firm year observations for 121 firms. The research addresses a broader question on how gender representation in corporate governance and engagement in social and environmental policies influence firms’ profitability and liquidity in an emerging market context. Using a multiple linear regression model, financial performance was measured through return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), asset turnover (ATO), and the current liquidity ratio (LIQ). The results indicate that CSR is positively associated with profitability indicators (ROA, ROE, ATO), while board gender diversity shows a negative short term relationship with these variables. Both CSR and board gender diversity are negatively associated with liquidity, reflecting short term financial commitments arising from sustainability and inclusion initiatives. These findings suggest that the financial implications of diversity and CSR initiatives may vary across temporal horizons and institutional contexts. The study contributes empirical evidence from a Latin American emerging market and underscores the importance of evaluating corporate governance and sustainability practices by considering the short term financial trade-offs of diversity and CSR initiatives and their potential longer term implications.

1. Introduction

High level corporate positions remain largely inaccessible to women, who occupy less than one quarter of senior management roles worldwide [1]. Although women have gradually gained representation on company boards in many countries, their trajectory toward such positions tends to be longer and hindered by structural barriers compared with that of men [2,3]. Empirical evidence indicates that a greater presence of women on boards may influence diverse organizational domains, including financial performance [4]. Nevertheless, most studies on board gender diversity have been conducted in developed regions such as North America [5,6], Western Europe [7,8], and Asia [9,10]. By contrast, Latin America remains relatively underexplored, leaving a substantive gap in literature.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has also become a major field of inquiry, yet its implications for corporate outcomes remain contested due to heterogeneous empirical findings. Some studies show that gender diverse boards are positively related to CSR engagement [11,12,13,14] whereas others report neutral or even insignificant effects [15,16,17]. The same pattern of inconsistency appears in the relationship between board gender diversity and financial performance: certain works identify a positive association [18,19,20], while others fail to confirm such effects [5,21,22]. More recent scholarships have begun to address these relationships in emerging economies, where firms often face higher exposure to environmental and social risks due to the prioritization of short-term profitability [23].

Existing studies examining board gender diversity and CSR can be broadly grouped into three perspectives: those finding a positive influence on financial performance, those reporting a negative impact, and those detecting no statistically significant association [4,24,25]. These divergent outcomes may arise from contextual differences across firms [26], the cultural and demographic characteristics of countries with distinct levels of gender equality [27], and the limited number of available business case studies [28]. A key challenge in this field lies in identifying explanatory variables that clarify the connection between board gender diversity, CSR, and financial performance [29]. As theoretical perspectives continue to evolve, these relationships require further empirical testing to consolidate consistent evidence.

In Latin America, the literature remains scarce regarding women’s participation on boards of directors and its connection to CSR and financial performance. Avolio et al. (2023) underscore two main reasons for deepening this analysis: first, the region has undergone profound labour market transformations with increasing female participation in professional and academic spheres; and second, Latin American societies have historically exhibited gendered power relations embedded in androcentric and patriarchal structures, often expressed through machismo [30].

Consequently, business practices in Latin America have gradually evolved toward more inclusive talent management strategies. However, the role of women on boards still demands comprehensive study to understand their influence on strategic and financial outcomes [18,31,32]. Comparative and longitudinal analyses are particularly relevant to capturing institutional and cultural specificities, shaping corporate behavior across the region.

The Peruvian context offers a compelling case study due to its mixed record on gender equality in the corporate sphere. Peru ranks 40th out of 146 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index 2024, with a score of 0.755, representing a decline of six positions from the previous year [1]. Although this drop is concerning, moderate gains have occurred in female economic participation. In regional comparison, neighboring countries such as Ecuador, Chile, Argentina, and Mexico outperform Peru overall, yet Peru leads in certain micro level indicators such as the proportion of female entrepreneurs and professionals in management roles [33,34]. This apparent discrepancy between macro level rankings and micro level realities suggests unique structural and cultural conditions shaping gender dynamics and CSR orientation within Peruvian corporations. Moreover, the Lima Stock Exchange provides a suitable empirical setting to examine these phenomena, as corporate decisions made there directly influence both financial and environmental outcomes. Analyzing this market thus enhances regional understanding and supports the design of strategies fostering genuine gender inclusion in business leadership.

Considering these contextual complexities, the present study investigates how board gender diversity and CSR relate to the financial performance of firms listed on the Lima Stock Exchange. The guiding question is: How are board gender diversity and CSR associated with the financial performance of companies operating in Peru? This inquiry responds to the broader need to determine whether female participation in corporate boards and the implementation of CSR practices exert measurable financial effects in emerging economies. Focusing on Peru contributes to global evidence on how gender diversity and sustainability interact as determinants of firm performance. The empirical analysis focuses exclusively on firms listed on the Lima Stock Exchange, so that the discussion of board gender diversity and CSR is framed in the context of publicly traded corporations rather than the overall population of firms.

This research offers both theoretical and practical contributions. It provides empirical support for agency theory, critical mass theory, upper echelons theory, and stakeholder theory, analyzing firms’ data for 2022 and 2023 through multiple regression models. While centred on Peru, the results may be generalized to the Latin American context, contributing to comparative debates on corporate governance, CSR, and financial performance in emerging markets.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Gender equality constitutes a persistent global challenge, formally recognized by the United Nations (UN) as the fifth Sustainable Development Goal [35]. Scholarly interest in women’s participation in the business environment dates to the 1970s, when researchers first sought to explain the persistent underrepresentation of women within organizations [36]. In the corporate context, gender is largely understood as a socio cultural construct that extends beyond biological distinctions to encompass differences in attitudes, cognitive frameworks, expectations, and socially assigned roles [37]. From an anti-feminist standpoint, traditional gender norms have historically prescribed domestic and caregiving responsibilities to women while assigning leadership and breadwinning roles to men [38,39]. Such socially embedded conventions perpetuate gender bias in professional evaluation processes, thereby influencing perceptions of competence and suitability for leadership positions [40].

Empirical research supports this view. Cuddy et al. (2007) demonstrated that gender stereotypes and the emotions they evoke can significantly shape behavioral tendencies toward social groups, reinforcing asymmetric treatment of women and men in managerial contexts [41]. Building on this, Laique et al. (2023) argued that analyzing gender diversity on boards through a single theoretical perspective is insufficient, as it overlooks the multidimensional nature of gendered interactions in decision-making bodies [4]. Consequently, this study adopts a multifaceted analytical approach to examine the complex relationships among board composition, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and financial performance.

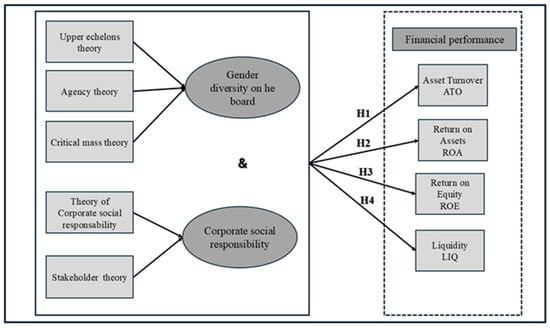

Accordingly, this literature review synthesizes previous contributions to these topics through the theoretical lenses of Upper Echelons Theory, Agency Theory, Critical Mass Theory, Corporate Social Responsibility Theory, Stakeholder Theory, and Financial Performance Theory. These frameworks jointly provide the conceptual foundation for understanding how gender diversity and CSR interact to influence organizational outcomes in emerging markets.

This study therefore adopts an explicitly multi theoretical framework in which upper echelons theory provides the primary overarching lens, while agency and CSR/stakeholder theories play complementary roles. From an upper echelon’s perspective, the gender composition of boards is a salient demographic attribute that shapes strategic choices, risk preferences and the attention devoted to social and environmental issues. Agency theory further specifies how boards perform their monitoring and incentive alignment functions vis-vis shareholders, whereas CSR and stakeholder perspectives highlight why boards may orient firms towards the interests of a broader set of stakeholders and towards responsible business practices. Finally, the critical mass and tokenism literature clarify the conditions under which the presence of women on boards translates into substantive influence rather than merely symbolic representation. Taken together, these lenses support the expectation that gender diversity and CSR will be associated with financial performance in emerging markets.

The Upper Echelons Theory posits that organizational outcomes mirror the values, cognitive orientations, and personal experiences of senior executives. Hambrick and Mason (1984) argue that the social and psychological attributes, skills, and demographic profiles of members of the board of directors and top management teams are reflected in strategic decision-making processes and, ultimately, in firm performance [42]. Building on this premise, subsequent studies emphasize that demographic characteristics such as gender, age, and ethnic origin act as observable proxies for underlying cognitive frameworks that shape strategic choices [43,44]. Within this framework, research in psychology and behavioral economics has identified systematic gender-based differences in overconfidence, risk tolerance, and access to information [45], as well as in socio psychological orientations [46], supervisory quality [47], and engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives [48]. These behavioral distinctions suggest that gender diversity at the upper echelons can alter group dynamics and influence how strategic decisions are conceived and implemented, prompting empirical studies to examine whether shifts in board composition; particularly, whether the inclusion of women affects operational decisions, governance practices, and overall company performance [48].

The Agency Theory conceptualizes the firm as a nexus of contracts where the separation of ownership and control generates potential conflicts of interest between principals (owners) and agents (managers). Jensen and Meckling (1976) define this relationship as arising from a contract in which one or more principals engage an agent to perform a service on their behalf, thereby delegating decision making authority and creating potential for opportunistic behavior [49]. They argue that agency costs including monitoring, bonding, and residual loss emerge when such separation occurs, primarily due to information asymmetry. Fama and Jensen suggest that these asymmetries can be mitigated by aligning managerial incentives with shareholders’ objectives. In this regard, the composition of the board of directors becomes a crucial mechanism for controlling agency problems [50]. Francoeur et al. (2008) and Chang et al. (2024) emphasized that the inclusion of women on boards enhances independence, strengthens monitoring functions, reduces informational biases, and improves problem solving processes, thereby aligning the interests of shareholders and directors while adding value to the firm [48,51]. Consequently, greater female representation contributes to more balanced oversight, increased board independence, and stakeholder alignment, ultimately leading to a reduction in agency costs [45,52]. While classic formulations of agency theory emphasize conflicts between dispersed shareholders and professional managers in widely held firms, many listed firms in emerging markets, including Peru, exhibit concentrated ownership and the presence of a controlling shareholder. In such settings, agency problems may also arise between controlling and minority shareholders, and the board’s composition including its gender diversity can affect both managerial agency costs and the protection of non-controlling owners.

The Critical Mass Theory originates from nuclear physics, where it denotes the minimum quantity required to initiate a chain reaction leading to an irreversible tipping point [53]. In the social sciences, this concept was adapted by Schelling (1971), Kanter (1977) and Granovetter (1978) to explain group behavioral thresholds in collective decision making [54,55,56]. Kanter (1977) underscored that the interaction dynamics between dominant and minority groups determine whether prevailing stereotypes can be neutralized, thereby enhancing the quality of group decisions [55]. To analyze these processes, Kanter (1977) proposed a typology of four gender composition structures: uniform groups (0:100), skewed groups dominated by one gender (85:15), tilted groups (65:35), and balanced groups (60:40) [57]. She argued that in tilted groups those approaching a 65:35 distribution women can overcome tokenism and exercise greater influence, having reached the threshold of critical mass. Within boards of directors, minority-gender members, typically women, are thus unlikely to exert substantial influence until this proportion is achieved [57,58]. Extending this reasoning, Konrad et al. (2008) proposed that the transition from tokenism to critical mass occurs once boards include at least three female members [59]. Supporting this notion, Joecks et al. (2013) identified a U-shaped relationship in which gender diversity initially exerts a negative effect on firm performance but becomes positive once women reach approximately 30% representation the so-called “magic number” [22].

The Theory of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) asserts that firms, beyond their economic objectives, threshold social and ethical obligations toward the communities and stakeholders with which they interact. Carroll (1979) argued that all companies display some degree of social performance, although they do not share identical responsibilities nor express CSR uniformly [60,61]. While no single definition dominates, CSR is generally understood as encompassing activities, organizational processes, and moral commitments oriented towards social or stakeholder welfare [62,63]. Carroll’s (1979) conceptual framework remains the most influential, portraying CSR as a proactive set of corporate actions that exceed minimal legal compliance, seeking simultaneously to promote social welfare and strengthen corporate success [60,64]. His model delineates four interrelated dimensions of responsibility: economic (profit generation), legal (compliance with laws), ethical (meeting societal expectations), and discretionary (voluntary engagement in socially desirable activities). Building upon this foundation, scholars such as Baron (2001), McWilliams and Siegel (2001), Waldman et al. (2006) and Vishwanathan et al., 2020 have conceptualized CSR as a strategic instrument that enhances corporate reputation, mitigates risk, fosters reciprocity among stakeholders, and stimulates innovation capacity [65,66,67,68].

The Stakeholder Theory posits that organizations operate within a network of relationships whose members and stakeholders affect and are affected by corporate decisions. Freeman (1984) argued that strategic and operational choices can significantly influence the interests of multiple stakeholder groups, either advancing or constraining the achievement of organizational objectives [69]. Because corporate actions may benefit or harm different groups, stakeholders themselves can be helped or hindered in pursuing their own goals [70]. Valentinov and Chia (2022) emphasized the importance of determining to whom firms are accountable and the specific nature of such accountability [71]. Building on this, Freeman et al. (2021) contended that effective stakeholder identification requires recognizing the needs and expectations of actors who can influence the firm’s access to critical resources such as employees, partners, suppliers, shareholders, and investors thereby ensuring organizational efficiency and legitimacy [72]. In this framework, corporate social responsibility initiatives serve as mechanisms for demonstrating social performance and accountability. Beyond ethical imperatives, they yield tangible benefits by enhancing corporate reputation, attracting diverse talent, and fostering innovation and creativity [73,74,75].

The concept of financial performance encompasses multiple dimensions through which a firm’s efficiency, profitability, and market valuation can be assessed. Orlitzky et al. (2003) and Abdullah et al. (2016) classify corporate financial performance into three broad categories: accounting performance, market performance, and perceptual performance [76,77]. Accounting measures capture objective financial realities and reflect the internal operational efficiency of firms through indicators such as asset turnover (ATO), return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and liquidity ratio (LIQ) [5,78,79]. For instance, Jang and Ahn (2021) employed asset turnover to evaluate the relationship between financial factors and managerial effectiveness in Korean companies, whereas Hassan and Marimuthu (2018) distinguished ROA as a managerial efficiency measure and ROE as an indicator of shareholder profitability [80,81]. Similarly, Nguyen et al. (2024) used the liquidity ratio to assess the ability of manufacturing firms listed on the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange (HSX) to convert assets into cash and meet short term liabilities [10]. Market performance indicators such as share price and share revaluation represent the satisfaction of shareholders as a primary stakeholder group, whose confidence is fundamental to corporate survival [78]. These market-based metrics respond to stock market dynamics shaped by perceptions of past, present, and expected returns and risks [76]. Finally, perceptual performance captures subjective evaluations by stakeholders regarding a company’s financial soundness, prudent asset management, and achievement of financial objectives relative to competitors [82,83,84].

The relationship between gender diversity and corporate financial performance remains one of the most debated topics in corporate governance research [22,36,85,86]. Hussain et al. (2024) through a systematic review of 113 studies, reported that 88 identified a positive impact of women’s presence on boards, nine indicated negative effects, and sixteen found no significant relationship [86]. Although these results appear to favor a positive association, their interpretation becomes complex when contextual and institutional contingencies are considered [5]. Joecks et al. (2013) and Marques et al. (2023) argue that such inconsistencies may stem from differences in country contexts, time periods, firm size, industry type, diversification strategies, performance metrics, estimation methods, and levels of female representation often influenced by gender quota legislation [8,22]. In this regard, research on Latin American firms remains scarce [87]. Hussain et al. (2024) noted only one regional study Husted and De Sousa (2019) which reported a negative relationship between female management and firm outcomes [86,88]. Hence, analyzing the effects of gender diversity on boards in Latin America is both timely and relevant. Most of these empirical contributions are based on samples of large, publicly listed corporations, which align with the focus of the present study on listed firms and cautions against generalizing the evidence to small or privately held companies.

Recent work further refines the link between board gender diversity and strategic outcomes by emphasizing the quality and depth of board level heterogeneity. Veltri et al. (2025) show that the relationship between women directors and firms’ R&D investments depends critically on women directors’ intellectual capital, as foreign, interlocked and tenured female directors strengthen the positive effect of board gender diversity on R&D expenditure [89]. Likewise, Chen et al. (2025) distinguish between surface level and deep level board diversity and find that these two forms of diversity have opposing effects on innovation, moderated by formal and informal board social structures [90]. Taken together, these studies suggest that the impact of board diversity on firm outcomes is contingent on the specific attributes of diverse directors and the internal dynamics of the board, reinforcing the need to consider contextual and institutional conditions when examining the effects of board gender diversity.

Similarly, empirical evidence on the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and financial performance has produced divergent conclusions. While Tsoutsoura (2004) found no significant association, Margolis et al. (2009) after reviewing a wide range of studies, observed a modest positive link [91,92]. Empirical works by Zu and Song (2009), Lenssen et al. (2011), and Sohn et al. (2020) further supported a positive relationship between CSR, particularly environmental responsibility, and improved financial outcomes [93,94,95]. Sohn et al. for instance, examined 714 North American firms between 2003 and 2010 and confirmed the financial benefits of proactive environmental engagement [95]. Complementarily, Van Beurden and Gössling (2008) conducted a meta-analysis of 57 studies, reporting that 68% found a positive CSR financial performance relationship, 26% found no relationship, and 6% identified a negative correlation [95,96]. Moreover, the meta analyses and large sample studies discussed here predominantly examine large and often publicly listed firms, so their implications are most directly applicable to the segment of corporations analyzed in this article.

Taken together, prior theoretical and empirical studies suggest that board gender diversity and CSR are jointly related to corporate financial performance, although the sign and magnitude of these effects vary across contexts [76,86,96]. Figure 1 presents the theoretical framework that summarizes these relationships. In this study, financial performance is operationalized through four complementary accounting-based indicators asset turnover (ATO), return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE) and the current liquidity ratio (LIQ) which have been widely used to capture operational efficiency, economic profitability, shareholder value creation and short term solvency [10,78,80,81]. Previous research has linked board gender diversity and CSR to these and related measures, generally finding positive associations but also reporting null or negative results depending on country characteristics, board structures and CSR regimes [19,20,51,52,92,95]. In the Peruvian and broader Latin American context, where female representation on boards remains low and firms seldom reach the 30% critical mass threshold, existing evidence is scarce and sometimes inconclusive [8,22,55,57,88]. Given this heterogeneity and the limited regional evidence, it is appropriate to formulate non-directional hypotheses on the associations between board gender diversity, CSR and ATO, ROA, ROE and LIQ, which are tested empirically below.

Figure 1.

Illustrate the theoretical model.

H1.

Board gender diversity (BGD) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) are associated with the firm’s asset turnover (ATO).

H2.

BGD and CSR are associated with return on assets (ROA).

H3.

BGD and CSR are associated with return on equity (ROE).

H4.

BGD and CSR are associated with the liquidity ratio (LIQ).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Measures

All observable variables representing theoretical constructions were obtained from publicly available, audited corporate documents for firms listed on the Lima Stock Exchange (BVL). The initial population comprised all firms continuously listed on the BVL during the 2022–2023 period. From this population, I retained those firms that, for both years, disclosed (i) audited annual financial statements, (ii) an annual report or corporate governance report specifying the composition of the board of directors, and (iii) a sustainability, ESG or integrated report. Firms with incomplete information in any of these sources for either 2022 or 2023 were excluded. The resulting balanced panel consists of 121 firms observed over two years (242 firm—year observations) across all economic sectors. Table 1 summarizes the variables used in the analysis, their operational definitions, formulas and data sources. The 2022–2023 window was chosen to capture the most recent configuration of board gender diversity, CSR disclosure and financial performance under current reporting practices in Peru, while ensuring a balanced panel with complete and comparable information for all firms.

Table 1.

Variables used in the analysis.

The construction of financial performance was operationalized through four dependent variables: asset turnover (ATO), return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and the current liquidity ratio (LIQ). These indicators capture distinct yet complementary dimensions of firm efficiency, profitability, and short term solvency, offering a multidimensional perspective of financial performance relevant to management and external stakeholders. All four indicators were computed from audited annual financial statements published by the firms under Lima Stock Exchange (BVL) and securities regulator (SMV) oversight (see Table 1).

The main independent variables correspond to Board Gender Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

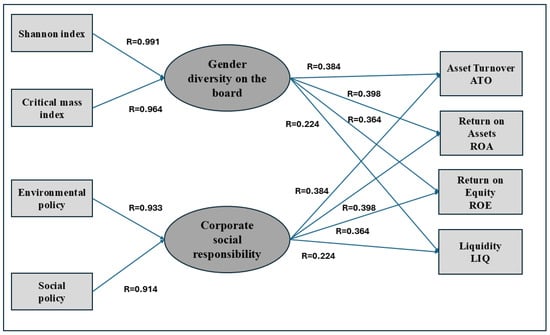

Board gender diversity (BGD) was operationalized using two continuous indices derived from the proportion of female and male directors on each board: the Shannon index and a critical mass index based on gender segregation. The Shannon index is an entropy-based measure that increases as the board composition becomes more balanced between female and male directors; it takes its minimum value when all directors belong to the same gender and its maximum value when women and men are represented in similar proportions (see Table 1). The critical-mass index is a normalized gender segregation index ranging from 0 to 1 (see Table 1), where 0 indicates no gender segregation (mixed boards, consistent with the idea of reaching a critical mass of women) and 1 indicates maximum gender segregation (boards dominated by a single gender). Using both indices allows us to capture complementary dimensions of board gender diversity: overall heterogeneity in gender composition and the extent to which one gender dominates the board structure. As a validity check, both indices exhibited very high positive correlations with the percentage of female directors on the board (R = 0.991 for the Shannon index and R = 0.964 for the critical-mass index), confirming that they consistently capture the underlying dimension of female representation.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) was measured through a content analysis of published corporate sustainability, ESG or integrated reports using a dichotomous checklist of 22 indicators grouped into two dimensions: environmental policy (12 items) and social policy (10 items). For each firm year observation, each item was coded as 1 when the corresponding policy or practice was disclosed in the report and 0 otherwise. Dimension scores were obtained by summing the items within each domain, and an overall CSR index was computed as the average of the environmental and social scores, so that higher values indicate broader and more comprehensive CSR engagement and disclosure (see Table 1). The environmental and social subindices were highly correlated with the overall CSR index (R = 0.933 and R = 0.914, respectively), supporting the internal coherence and convergent validity of the measure.

2.2. Data Analysis

The empirical analysis was performed using multiple linear regression (MLR) to examine the relationships between board gender diversity, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and financial performance. According to Hair et al. multiple linear regression enables the simultaneous assessment of the effects of several independent variables on one or more dependent variables, thereby allowing a comprehensive evaluation of complex organizational dynamics [97]. This modelling approach is consistent with prior empirical research on board gender diversity, CSR and financial performance, where multiple linear regression is widely used to estimate firm-level relationships [5,19,20,22].

2.3. Regression Models

The statistical model employed is broadly specified as follows:

where

represents each financial performance indicator (ATO, ROA, ROE, LIQ).

is the constant.

and are the coefficients that capture the effect of BGD and CSR.

corresponds to the error term.

Model specified for each research hypothesis.

In the notation used in Table 1, and denote the proportions of female and male directors on firm ’s board, respectively, and terms such as follow the standard Shannon entropy formulation for diversity indices. In the Peruvian sample analysed, the Shannon Index ranges from 0 to 0.66, with most boards lying between 0.10 and 0.20 (see Table 1), which reflects relatively low levels of gender diversity and the absence of a critical mass of women in most firms.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive analysis indicates that board gender diversity in Peru remains low, with women occupying approximately 15% of board positions. This limited participation, coupled with a moderate standard deviation, reveals significant inter firm variability. These findings are consistent with previous evidence highlighting persistent gender gaps in Latin American corporate structures, where female representation seldom exceeds the 30% critical mass threshold [22]. In contrast, European Union firms reported an average of 32% women on boards in 2022, largely due to legislative enforcement [11,98].

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) scores show moderate average values but high dispersion, reflecting heterogeneity in the adoption of sustainability policies across sectors and company sizes. Such variability aligns with literature that identifies sectoral and internationalization differences as key determinants of CSR engagement in emerging economies [99,100].

Regarding financial indicators, the average values of return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and asset turnover (ATO) are positive but exhibit wide variability, reflecting volatility typical of emerging markets. The average liquidity ratio (LIQ) of approximately 1.2 indicates that most firms maintain current assets slightly above short term liabilities, though several display solvency risks.

Overall, descriptive statistics confirm the suitability of the data for econometric testing, showing (i) sufficient variability in board gender diversity (BGD) and CSR, and (ii) heterogeneous distributions of financial indicators that justify multivariate regression analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the variables studied.

Additionally, the correlation matrix demonstrates that no multicollinearity problem exists among the main variables (R < 0.70), ensuring the robustness of regression estimates. (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Correlation matrix between key variables.

3.2. Multiple Regression Model and Hypotheses

The multiple linear regression models (Table 3) reveal that BGD and CSR jointly explain between 12% and 14% of the variation in profitability (ATO, ROA, ROE) and about 3% of the variation in liquidity (LIQ). All models are statistically significant (p < 0.05), confirming the explanatory relevance of the independent variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Model summary of regression analyses.

ANOVA results (Table 4) show strong significance for the profitability models H1 (F = 10.227, p = 0.000), H2 (F = 11.133, p = 0.000) and H3 (F = 10.216, p = 0.000) indicating that BGD and CSR are significantly associated with accounting profitability, while constituting only a subset of the broader set of factors that influence firm profitability. The liquidity model (H4) is also significant (F = 3.119, p = 0.048), albeit with lower explanatory power, consistent with the short term sensitivity of liquidity to external conditions. These findings are broadly consistent with meta-analytic evidence from developed economies, where CSR is generally positively related to accounting-based performance indicators [76,92,96]. By contrast, the negative short term association between BGD and profitability in the Peruvian sample resembles the initial segment of the nonlinear patterns documented in some European settings, where the impact of board gender diversity becomes positive only after a critical mass of women is reached [11,22]. The regression coefficients for the model variables are also presented. Table 5. In addition, the mixed and context-dependent results reported for board diversity and CSR in other emerging markets [19,88,99] suggest that the Peruvian evidence should be interpreted as one case within a broader, heterogeneous landscape rather than as a generalized Latin American pattern.

Table 4.

Anova results for multiple linear regression analyses.

Table 5.

Regression coefficients for H1–H4 models.

Regression equations derived from these results are as follows:

H1: ATO = −0.559 − 0.932 BGD + 2.108 CSR.

H2: ROA = −0.564 − 0.902 BGD + 2.151 CSR.

H3: ROE = −0.557 − 0.925 BGD + 2.100 CSR.

H4: LIQ = 2.018 − 1.165 BGD − 0.761 CSR.

4. Discussion

The results provide nuanced insights into the complex relationship between board gender diversity (BGD), corporate social responsibility (CSR), and financial performance in an emerging market context. The findings contribute to both theoretical refinement and empirical understanding of how governance and sustainability mechanisms interact in Latin American firms.

First, the positive and statistically significant effect of CSR on profitability supports the premise that responsible corporate practices enhance stakeholder trust, operational efficiency, and firm legitimacy. These findings are consistent with Stakeholder Theory [69] and with meta analytic evidence demonstrating that CSR activities can generate tangible short-term financial returns [76,101]. In line with Birindelli et al. (2019) this result reinforces the notion that responsiveness to environmental and social expectations should not be regarded as a cost but as a strategic intangible asset that strengthens competitiveness and reputation [99]. For emerging economies such as Peru, CSR initiatives appear to play a compensatory role, signaling corporate reliability in institutional contexts marked by regulatory asymmetries and weaker governance mechanisms.

Second, the negative short-term association between board gender diversity and accounting profitability diverges from the findings in developed markets, where gender-diverse boards have been shown to enhance firm performance once a critical mass is achieved [11,22]. In the Peruvian sample, women held only around 15% of board positions, indicating that none of the analyzed firms reached the 30% threshold identified by Critical Mass Theory [55,57,59]. Under these conditions, gender diversity may initially generate transitional frictions, organizational adaptation costs, or limited access to influential corporate networks [5]. Consequently, diversity effects are not linear or universal but contingent upon institutional maturity, inclusion mechanisms, and cultural norms. In this regard, the negative association between board gender diversity and financial performance should not be interpreted as evidence that the presence of women on boards “destroys value”, but rather as a reflection of the specific institutional and cultural context in which these boards operate. The tokenism and critical mass literature suggests that, if women remain a numerical minority on predominantly male boards, they are likely to face heightened visibility, pressure to conform to existing norms and limited access to informal power networks, which constrains their ability to translate task conflict into higher quality strategic decisions [55,57]. In Latin America, prior studies show that the effect of board gender diversity on firm performance is often weak or neutral because of the persistent underrepresentation of women and cultural features that tend to dampen the potential benefits of diversity [30,87]. In the Peruvian case, women directors still operate in predominantly male dominated corporate environments, where nomination processes, informal networks and expectations about the “appropriate” role of women in top management may favor symbolic or legitimacy-driven appointments rather than substantive inclusion [30].

Third, the negative association between both BGD and CSR with liquidity suggests that equity and sustainability initiatives require short term financial commitments that temporarily constrain firms’ solvency. This finding is consistent with prior studies noting that investments in CSR and governance restructuring entail immediate costs before long-term benefits accrue [78,101]. Firms in emerging economies may face liquidity pressures due to the reallocation of resources towards compliance, training, or social projects; however, these expenditures often yield delayed returns through improved reputation, customer loyalty, and reduced risk exposure. From this perspective, the negative association between current liquidity, board gender diversity and CSR can be interpreted as reflecting short term costs arising from more active investment and working capital decisions. More gender diverse and stakeholder oriented boards are likely to authorize upfront cash outlays in environmental compliance and adaptation projects, health and safety programmers, community and stakeholder initiatives, the implementation of more demanding reporting and disclosure systems, and training and capacity building activities. These expenditures are typically recognized as operating expenses or long term investments rather than as current assets, and in emerging markets they are often financed with internal funds and short term liabilities, which temporarily depress liquidity ratios without necessarily implying a deterioration in solvency [76,78,101]. In addition, more active boards with a stronger CSR orientation may be less inclined to hoard idle cash for precautionary motives and more willing to deploy liquid resources in productive or reputation enhancing projects, consistent with the view of CSR as a strategic intangible asset [99].

From a methodological perspective, the study confirms the adequacy of multiple linear regression models for evaluating governance performance relationships in emerging markets. The statistical robustness of the models (significant ANOVA tests) validates the approach, while the moderate explanatory power (adjusted R2 values between 0.12 and 0.14 for profitability and 0.03 for liquidity) indicates that additional firm level and contextual variables should be incorporated. Future studies could control firm size, leverage, ownership structure, or industry heterogeneity to further clarify these associations.

Overall, the evidence underscores the context dependent nature of corporate governance effects. In markets characterized by low institutional maturity and limited gender inclusion, the immediate financial impact of diversity and sustainability initiatives may appear muted or even negative. Nevertheless, as female representation and CSR integration progress over time, their joint influence is likely to shift toward positive outcomes. This trajectory reinforces the importance of adopting a long term analytical horizon and of employing dynamic or longitudinal designs to capture the evolving financial implications of inclusion and sustainability strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the relationship between board gender diversity, corporate social responsibility, and financial performance among firms listed on the Lima Stock Exchange during 2022 and 2023. Using multiple linear regression, the research demonstrates that CSR is positively associated with accounting profitability measured by ATO, ROA, and ROE whereas board gender diversity exhibits a negative short term relationship with profitability and liquidity.

CSR contributes positively to short term profitability, confirming its role as a strategic lever for value creation even when liquidity may be temporarily constrained by sustainability investments. By contrast, board gender diversity shows a negative short term association with ROA, ROE and ATO, which is consistent with the idea that, under low female representation and the absence of a critical mass of women, early stages of inclusion may entail adjustment costs, learning processes and organizational frictions. According to Critical Mass Theory and evidence from other countries, it is plausible that, once more balanced boards are achieved and inclusive practices consolidate, the impact of gender diversity on profitability may become neutral or positive; however, this remains a theoretically informed conjecture, as the two year Peruvian panel analyzed here does not observe such thresholds and does not allow these longer term dynamics to be tested directly. These potential medium and long term effects should therefore be understood as theoretically grounded expectations and an avenue for future research rather than as conclusions derived directly from the present data.

The findings are consistent with and help contextualize Stakeholder Theory and Critical Mass Theory within the Latin American context, suggesting that the benefits of governance diversity and CSR are likely to depend on reaching a threshold of board inclusion and institutional maturity, rather than operating in a purely linear fashion. However, these threshold related implications should be understood as theoretically grounded interpretations informed by international evidence, as the two year Peruvian panel analyzed here does not observe boards surpassing such thresholds. They also provide evidence that CSR functions as a strategic mechanism for corporate legitimacy and risk management in emerging markets, where firms face heightened scrutiny and institutional voids. More broadly, the study advances a multi theoretical view of corporate governance by integrating upper echelons, agency and CSR/stakeholder perspectives in an emerging market setting, showing that board gender composition and CSR policies should be understood jointly as part of the board’s strategic, monitoring and boundary spanning roles. In doing so, the article links board level demographic attributes to firm level financial outcomes through a theoretically grounded configuration of governance, CSR and institutional context, thereby refining existing theories of board diversity and CSR in the specific case of Latin American capital markets.

For practitioners and policymakers, the results highlight the need to foster inclusion and sustainability policies through gradual implementation and long-term commitment. Firms should design governance structures that ensure women’s substantive participation, not merely symbolic representation, while aligning CSR investments with core business strategies to balance financial stability and social performance.

In conclusion, the evidence derived from this underexplored Latin American setting confirms that corporate social responsibility acts as a catalyst for improved financial performance, while gender diversity on boards, in the absence of a critical mass and enabling institutional frameworks, can temporarily hinder profitability. These findings invite a reevaluation of traditional governance paradigms and highlight the need for comparative, interdisciplinary, and longitudinal approaches to capture the dynamic interplay between sustainability practices, board composition, and corporate financial outcomes.

Moreover, the empirical design relies on a relatively short balanced panel, consisting of 121 firms observed over the 2022–2023 period (242 firm year observations). This time window allows me to capture the most recent configuration of board gender diversity, CSR and financial performance, but it limits the ability to analyze dynamic or long term effects and constrains the strength of any causal inference. Accordingly, the estimated coefficients should be interpreted as contemporaneous associations that are consistent with the theoretical frameworks employed, rather than as definitive causal impacts. In addition, the sample is restricted to firms listed on the Lima Stock Exchange, which ensures data availability but limits the external validity of the findings for smaller or unlisted companies. Consequently, the evidence reported here should be interpreted as pertaining primarily to relatively large, listed corporations, and future research should replicate and extend the analysis to SMEs, family owned and unlisted firms.

Future studies should incorporate broader time series or panel data, multi country comparisons, and advanced modelling techniques such as structural equation modelling (SEM), threshold regressions, or machine learning (e.g., neural networks) to detect non-linear effects. Mixed method approaches combining qualitative insights with quantitative analysis could also illuminate the organizational processes behind the observed relationships. From a methodological perspective, future research could also explore deep learning approaches that rely on more advanced pooling strategies; in particular, singular pooling has recently been proposed as a spectral pooling paradigm that aggregates high dimensional feature maps via singular value decomposition while reducing information loss in deep neural networks [102]. Although such techniques are beyond the scope of the present study, they could be employed in future work that integrates richer, high-dimensional ESG/CSR indicators or textual disclosures to model more complex, nonlinear relationships between board gender diversity, CSR and financial performance.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from publicly accessible sources. Specifically, financial and corporate information was extracted from the Lima Stock Exchange (BVL) and the Superintendency of the Securities Market (SMV) official databases. All data are publicly available through the institutional websites https://www.bvl.com.pe (accessed 20 May 2025) and https://www.smv.gob.pe (accessed 20 May 2025). No proprietary or confidential data were used in this research.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5, 2025 version) to assist with language refinement, structural alignment to the MDPI Journal of Sustainability template, and improvement of academic style and consistency. The author reviewed, verified, and edited all AI-assisted content and assumes full responsibility for the accuracy, interpretation, and conclusions presented in this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BGD | Board Gender Diversity |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

References

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2024; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2024/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Lee, J.S.; Lan, L.L.; Rowley, C. Why might females say no to corporate board positions? The Asia Pacific in comparison. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2014, 20, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, G.; Huang, W.; Han, S.H.C. Conceptual review of underrepresentation of women in senior leadership positions from a perspective of gendered social status in the workplace: Implication for HRD research and practice. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2017, 16, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laique, U.; Abdullah, F.; Rehman, I.U.; Sergi, B.S. Two decades of research on board gender diversity and financial outcomes: Mapping heterogeneity and future research agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2121–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; Ferreira, D. Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.H.; Tasnia, M.; Mostafiz, M.I. Board gender diversity and environmental, social and governance performance of US banks: Moderating role of environmental, social and corporate governance controversies. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachouri, M.; Salhi, B.; Jarboui, A. The impact of gender diversity on the relationship between managerial entrenchment and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from UK companies. J. Glob. Responsib. 2020, 11, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Pascaru, O. Voluntary gender diversity targets and their impact on firm performance and firm value. J. Int. Account. Res. 2023, 22, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, Y.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Hsu, Y.J.; Lu, C.H.; Chang, M.L. Gender diversity in top management team and corporate social responsibility performance: Examining the moderating nature of TMT international experience. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2024, 39, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.Q.; Phan, T.H.N.; Hang, N.M. The effect of liquidity on firm’s performance: Case of Vietnam. J. East. Eur. Cent. Asian Res. 2024, 11, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.; Byron, K. Women on boards and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1546–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setó-Pamies, D. The relationship between women directors and corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.C.; Carmenate, J. Does board diversity influence firms’ corporate social responsibility reputation? Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 1299–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjahjadi, B.; Hapsari, A.P.; Soewarno, N.; Sutarsa, A.A.P.; Fairuzi, A. Women on boards, corporate environmental responsibility engagement and corporate financial performance: Evidence from Indonesian manufacturing companies. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2024, 39, 1017–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanwick, P.A.; Stanwick, S.D. The determinants of corporate social performance: An empirical examination. Am. Bus. Rev. 1998, 16, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, F.; Locke, S. Board structure, ownership structure and firm performance: A study of New Zealand listed firms. Asian Acad. Manag. J. Account. Financ. 2012, 8, 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jhunjhunwala, S.; Mishra, R. Board Diversity and Corporate Performance: The Indian Evidence. IUP J. Corp. Gov. 2012, 11, 71. Available online: www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/board-diversity-corporate-performance-indian/docview/1034107201/se-2 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Arioglu, E. Female board members: The effect of director affiliation. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N.; Baydauletov, M. Corporate social responsibility strategy and corporate environmental and social performance: The moderating role of board gender diversity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera-Alvarado, N.; Bravo-Urquiza, F. The impact of board diversity and voluntary risk disclosure on financial outcomes: A case for the manufacturing industry. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, L.; Humphrey, J.E. Does board gender diversity have a financial impact? Evidence using stock portfolio performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 122, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joecks, J.; Pull, K.; Vetter, K. Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm performance: What exactly constitutes a “critical mass”? J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sial, M.S.; Zheng, C.; Cherian, J.; Gulzar, M.A.; Thu, P.A.; Khan, T.; Khuong, N.V. Does corporate social responsibility mediate the relation between boardroom gender diversity and firm performance of Chinese listed companies? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J.; Shum, P. Do customer satisfaction and reputation mediate the CSR–FP link? Evidence from Australia. Aust. J. Manag. 2012, 37, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M.; Uyar, A. Board attributes, CSR engagement, and corporate performance: What is the nexus in the energy sector? Energy Policy 2020, 143, 111582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. An institutional approach to gender diversity and firm performance. Organ. Sci. 2020, 31, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, B.S. Perspective—The black box of organizational demography. Organ. Sci. 1997, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoobler, J.M.; Masterson, C.R.; Nkomo, S.M.; Michel, E.J. The business case for women leaders: Meta-analysis, research critique, and path forward. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2473–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Oever, K.; Beerens, B. Does task-related conflict mediate the board gender diversity–organizational performance relationship? Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.; Pretell, C.; Valcazar, E. Women on corporate boards in a predominantly male-dominated society: The case of Peru. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 38, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Anca, C.; Gabaldon, P. Female directors and the media: Stereotypes of board members. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2014, 29, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, L.; Gabaldon, P. Women on boards of directors in Latin America: Building a model. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2018, 31, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. International Labour Organization Annual Report 2023; ILO Publications: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/annual-report-2023 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- World Bank. Data on Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina and Mexico; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://datos.bancomundial.org/?locations=CL-AR-BR-PE-CO (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Cano, C.; Gonzalez-Perez, M.A. Representation of women on corporate boards of directors and firm financial performance. In Diversity Within Diversity Management: Types of Diversity in Organizations; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, A.; Francoeur, C.; Labelle, R.; Laffarga, J.; Ruiz-Barbadillo, E. Appointing women to boards: Is there a cultural bias? J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pride, M. The Way Home: Beyond Feminism, Back to Reality; Home Life Books: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Schlafly, P. Feminist Fantasies; Spence Publishing Company: Dallas, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, C. Women, careers, and work-life preferences. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2006, 34, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezsö, C.L.; Ross, D.G. Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernile, G.; Bhagwat, V.; Yonker, S. Board diversity, firm risk, and corporate policies. J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 127, 588–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciappei, C.; Liberatore, G.; Manetti, G. A systematic literature review of studies on women at the top of firm hierarchies: Critique, gap analysis and future research directions. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14, 202–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croson, R.; Gneezy, U. Gender differences in preferences. J. Econ. Lit. 2009, 47, 448–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.U.; Zahid, M. Women directors and corporate performance: Firm size and board monitoring as the least focused factors. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 36, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wu, K.T.; Lin, S.H.; Lin, C.J. Board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2024, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francoeur, C.; Labelle, R.; Sinclair-Desgagné, B. Gender diversity in corporate governance and top management. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, H.; Mallin, C. Board diversity and financial fragility: Evidence from European banks. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2017, 49, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefley, F.; Janeček, V. Board gender diversity, quotas and critical mass theory. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2024, 29, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelling, T.C. Dynamic models of segregation. J. Math. Sociol. 1971, 1, 143–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.M. Men and Women of the Corporation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. Threshold models of collective behavior. Am. J. Sociol. 1978, 83, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.M. Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 965–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, C.; Alves, S.; Quaresma, B. Women on boards in Portuguese listed companies: Does gender diversity influence financial performance? Sustainability 2022, 14, 6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.M.; Kramer, V.; Erkut, S. Critical mass: The impact of three or more women on corporate boards. Organ. Dyn. 2008, 37, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D. Corporate Citizenship in Australia: Some Ups, Some Downs. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2002, 2002, 73–84. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/jcorpciti.5.73 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Wood, D.J. Corporate social performance revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. How does corporate social responsibility benefit firms? Evidence from Australia. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2010, 22, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.P. Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2001, 10, 7–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D.S.; Javidan, M. Components of CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1703–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanathan, P.; van Oosterhout, H.; Heugens, P.P.M.A.R.; Duran, P.; Van Essen, M. Strategic CSR: A concept building meta-analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 314–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Marom, I.Y. Toward a unified theory of the CSP–CFP link. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinov, V.; Chia, R. Stakeholder theory: A process-ontological perspective. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 762–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Dmytriyev, S.D.; Phillips, R.A. Stakeholder theory and the resource-based view of the firm. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1757–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.W. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Account. Organ. Soc. 1992, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter-Hayashi, D.; Vermeulen, P.; Knoben, J. Is this a man’s world? The effect of gender diversity and gender equality on firm innovativeness. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Minutiello, V.; Tettamanzi, P. Gender disclosure: The impact of peer behaviour and the firm’s equality policies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.N.; Ismail, K.N.I.K.; Nachum, L. Does having women on boards create value? The impact of societal perceptions and corporate governance in emerging markets. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, P.L.; Wood, R.A. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S.A.; Ryan, M.K.; Kulich, C.; Trojanowski, G.; Atkins, C. Investing with prejudice: The relationship between women’s presence on company boards and objective and subjective measures of company performance. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.W.; Ahn, W.C. Financial analysis effect on management performance in the Korean logistics industry. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2021, 37, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Marimuthu, M. Contextualizing comprehensive board diversity and firm financial performance: Integrating market, management and shareholder’s perspective. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 634–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, B.C. Organizational effectiveness and management’s public values: A canonical analysis. Acad. Manag. J. 1975, 18, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conine, T.E.; Madden, G.P. Corporate social responsibility and investment value: The expectational relationship. In Handbook of Business Strategy; Warren Gorham and Lamont: Boston, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wartick, S.L. How issues management contributes to corporate performance. Bus. Forum 1988, 13, 16. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/how-issues-management-contributes-corporate/docview/210204027/se-2 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Carter, D.A.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financ. Rev. 2003, 38, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.M.; Ahmad, N.; Fazal, F.; Menegaki, A.N. The impact of female directorship on firm performance: A systematic literature review. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 913–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Cardenas, V.; Gonzalez-Ruiz, J.D.; Duque-Grisales, E. Board gender diversity and firm performance: Evidence from Latin America. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 12, 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; de Sousa-Filho, J.M. Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, S.; Mazzotta, R.; Cambrea, D.R.; Ferrigno, G. Women Directors and R&D Investments Relationship: Does Their Intellectual Capital Matter? R&D Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hsu, P.H.; Lee, Y.T.; Mack, D.Z. How Deep-Level and Surface-Level Board Diversity, Formal and Informal Social Structures Affect Innovation. J. Manag. Stud. 2025, 62, 65–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoutsoura, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance. In Applied Financial Project; University of California at Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/111799p2 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does It Pay to be Good…and Does it Matter? A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Corporate Social and Financial Performance. Working Paper; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, L.; Song, L. Determinants of managerial values on corporate social responsibility: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, G.; Blagov, Y.; Bevan, D.; Chen, H.; Wang, X. Corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance in China: An empirical research from Chinese firms. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2011, 11, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, N. Going green inside and out: Corporate environmental responsibility and financial performance under regulatory stringency. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beurden, P.; Gössling, T. The worth of values—A literature review on the relation between corporate social and financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C.P.; Homroy, S.; Liang, W. Female directors, board committees and firm performance. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2018, 102, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindelli, G.; Iannuzzi, A.P.; Savioli, M. The impact of women leaders on environmental performance: Evidence on gender diversity in banks. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1485–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Muñoz, A.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Boiral, O. Board gender and nationality diversity and corporate human rights performance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2024, 33, 760–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, P. Corporate goodness and shareholder wealth. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Cai, J.; Xiong, R.; Zheng, L.; Ma, D. Singular pooling: A spectral pooling paradigm for second-trimester prenatal level II ultrasound standard fetal plane identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 12508–12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.