Abstract

Against the backdrop of rising global carbon emissions, promoting active transportation modes such as walking and cycling has become a key strategy for countries worldwide to meet carbon reduction targets and advance the goals of sustainable development. In China, the concept of low-carbon mobility has gained rapid traction, leading to a significant increase in public demand for non-motorized travel options like walking and cycling. From the perspective of inclusive urban development, gender imbalances in sample representation during design and evaluation processes have contributed to homogenization and a lack of diversity in urban slow-traffic environments. To address this issue, this study adopts a problem-oriented approach. First, we collect street scene images of slow-traffic environments through self-conducted field surveys. Concurrently, we gather satisfaction survey responses from 511 urban residents regarding existing slow-traffic streets, identifying three key environmental evaluation indicators: safety, liveliness, and beauty. Second, an experimental analysis is conducted to compare machine-generated assessments based on self-collected street view data with manual evaluations performed by 27 female participants. The findings reveal significant perceptual differences between genders in the assessment of slow-moving environments, particularly regarding attention to environmental elements, challenges in utilizing non-motorized lanes, and overall environmental satisfaction. Moreover, notable discrepancies are observed between machine scores and manual assessments performed by women. Based on these findings, this study investigates the underlying causes of such perceptual disparities and the mechanisms influencing them. Finally, it proposes female-inclusive strategies aimed at enhancing the quality of slow-traffic environments, thereby addressing the current absence of gender considerations in their design. This research seeks to provide a robust female perspective and empirical evidence to support improvements in the quality of slow-moving environments and to inform strategic advancements in their design. The findings of this study can provide a theoretical and empirical basis for the optimization of gender-inclusive non-motorized transportation environment design, policy formulation, and subsequent interdisciplinary research.

1. Introduction

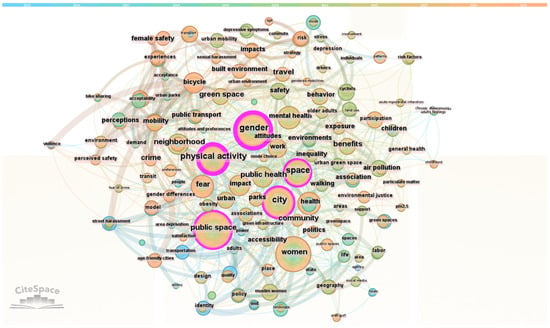

The United Nations Women Friendly Cities Joint Program proposes to provide inclusive green spaces [1,2] for women, children, the elderly, and disabled groups by 2030 [3]. This program aims to ensure women and other groups can thrive in cities. Using the Web of Science as the database, the literature from over the past ten years was searched using the keyword “slow-moving environment” [4,5]. After visual analysis was performed with VOSviewer 1.6.17, a keyword burst analysis diagram (Figure 1) and a keyword co-occurrence analysis diagram were created (Figure 2). We found that current gender-based research has become an important topic (see Figure 1), but women are much less involved in the process of urban planning and management than men, which highlights the survival pressure under the dual responsibilities of society and family [3,6,7].

Figure 1.

Graph showing research keyword appearance in different periods.

Figure 2.

Global network of scholarly research on gender differences.

According to China MIIT data, by the end of 2024, the number of electric bicycles in China exceeded 350 million, and many groups choose to ride slowly [8]. However, existing research on urban slow-moving streets mostly focuses on group commonality [9,10,11], neglecting gender differences in spatial experience and overlooking women’s special needs in urban cycling spaces and social evaluations.

In the realm of environmental studies, global scholarly research centered on gender differences has experienced a continuous upward trajectory [12,13]. As illustrated in Figure 2, this trend indicates that the integration of gender difference perspectives into public space planning research and practice has entered a phase of rapid development. Within the scope of research on slow-moving environments, academic focus primarily converges on four core themes: cyclists [14,15], crash involvement [16,17], inclusive urban rights [18,19], slow-moving system planning [20,21], and characteristics of the bicycle infrastructure and services [22]. Specifically, existing studies on women’s cycling environments are concentrated in three key areas: e-bike safety [23,24], perceived safety [25,26], and design strategies from the female perspective [27,28]. Current urban studies conducted from a feminist perspective have revealed the problems faced by women in spatial planning, transportation spaces, workspaces, and supporting facility design [29,30]. Overall, current research remains largely confined to the dimensions of psychological perception and behavioral analysis [31,32], while research on street environments’ inclusiveness for female cyclists is still in its early stages. Therefore, this study adopted a self-collected street scene method with higher timeliness to collect images of the main slow-traffic roads in Changsha, and then representative street scene pictures were selected as scoring samples. Subsequently, the scores generated by the research and training model were compared with those assigned manually by female evaluators to examine potential discrepancies in scoring criteria between the two approaches. Concurrently, a dataset comprising 511 online questionnaires was analyzed to investigate gender-based differences in perception within chronic environments. This study aims to contribute robust female perspectives and empirical data to help enhance chronic environmental quality and to inform strategic improvements in slow-traffic environment design.

2. Research Framework

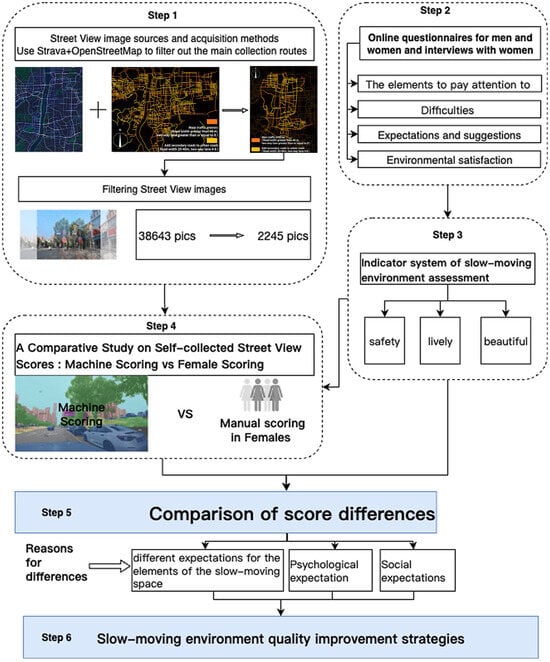

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating qualitative research—comprising 511 online questionnaires and in-depth interviews with 27 female participants conducted offline—with quantitative analysis involving a comparative assessment of machine-based and human-based scoring systems. The research investigates the influence of slow-traffic environments on women’s perceptual experiences and examines the discrepancies and underlying logic between automated and manual evaluation methods within the context of machine learning. The findings aim to inform the development of gender-sensitive strategies for enhancing slow-traffic infrastructure and to contribute a more equitable perspective to urban renewal initiatives, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Conceptual diagram of the proposed research framework.

2.1. Research and Application of Perception of Slow-Moving Environment

In machine perception evaluation, the MIT Place Pulse 2.0 dataset is widely used. First, it correlates data such as violent crime and economic growth to explore the potential relationship between urban perception and related factors, providing a multi-dimensional perspective for urban governance and economic strategy formulation. Second, its crowdsourced data and street score, street change, and other derivative algorithms provide urban planners with innovative tools to help optimize planning decisions and understand the dynamic changes in public perception regarding urban development [33].

This dataset plays a significant role in multiple fields: In urban planning and design, it clarifies public preferences through scores for indicators such as streetscape safety and esthetics, guiding the optimization of street landscapes. Regarding safety improvement, it identifies visual elements (e.g., building proportions) that influence safety perception, providing support for enhancing public security. Additionally, it can be combined with geographic information to construct urban perception maps reflecting the public’s subjective feelings, visualize the perceptual conditions of regions, and provide a basis for the allocation of planning resources [34].

Therefore, we conduct a comparative analysis based on this dataset to explore the similarities and differences between machine and female perceptions. From the 511 valid questionnaire responses collected, it can be inferred that female perception of slow-moving environments primarily relies on three indicators: safety, liveliness, and beauty. Current machine perception models are typically trained on aggregated population data, which may overlook gender-specific perceptual differences. The findings provide empirical support for more inclusive and accurate urban street planning strategies, such as targeted improvements in lighting conditions and pedestrian infrastructure to better accommodate the needs of diverse user groups.

2.2. Evaluation and Practice of Slow-Moving Environments from a Gender Perspective

In the context of spatial justice, women should not be regarded as a vulnerable group; instead, they should be entitled to equal rights to urban public spaces, just like men. At the urban planning level, most existing studies and discussions focus solely on the perspective of childcare [35], with relatively little systematic consideration of the impact of urban spatial elements on women’s development [36]. In real life, an increasing number of women not only participate in social work but also must take on household responsibilities. As a result, compared with men’s travel, women’s travel is characterized by more multi-destination and multi-mode features [36]. Women often need to transport daily supplies or travel with children, yet urban transportation spaces have not effectively responded to their travel needs [37,38,39]. For instance, the occupation of non-motorized lanes and sidewalks by private cars has caused significant inconvenience for women using slow-moving streets. This has also led to a disconnect and inadequacy between theoretical research and social practice. Therefore, with the efforts of various countries, the construction of women-friendly cities is gradually advancing.

At the design level, ensuring street spaces are safety-oriented and applying intelligent facilities are conducive to the creation of women-friendly transportation spaces [3]. Measures such as adding lighting and monitoring facilities to slow-moving streets [40,41,42] and reducing the green view index can improve the visual integration of the environment and reduce visual depth, thereby reshaping women’s sense of safety in street spaces. For example, the Women-Specific Design District in Area 2-2 of Sejong City, South Korea, has developed multiple “safe streets” based on the concept of a smart city [43].

However, in real-life scenarios, women still experience many travel dilemmas when using slow-moving systems. For instance, issues such as the lack of family-friendly toilets, the scarcity of public space nodes along streets, and the inadequate development of street furniture in slow-moving systems persist. All of these problems give rise to safety concerns and mobility difficulties for women during their travels.

3. Human–Machine Perception Comparison: Experimental Design and Results

This section describes the experimental design and data processing workflow to compare human–machine perceptions. We collected street view videos along selected routes, and image samples were generated through time-based frame extraction. Concurrently, three key perceptual indicators—safety, liveliness, and beauty—were obtained from 511 valid responses to an online questionnaire administered to participants. Machine-derived perception scores were computed based on the extracted image samples, while the same images were independently rated by 27 female participants to obtain human perception scores. The resulting paired scores were analyzed to quantify the discrepancies between human and machine perceptions across the three dimensions.

3.1. Controlled Study Sample

In previous small-sample studies, the sample generally comprised 8–30 participants [44]. For example, one study conducted an experiment with eight participants to explore the impact of natural environments on emotional well-being [45]; another study employed 10 participants to investigate the influence of safety-oriented street designs on women’s perceived safety [25,26]. This study, informed by the demographic profiles of primary age groups associated with cycling and slow-moving environments, categorized female respondents into four age cohorts. Participants were specifically recruited based on three distinct identities: cycling enthusiasts, environmental designers, and urban residents. Offline interviews were conducted with 27 participants in the form of focus groups, each consisting of 3 people and lasting 30 min. The interviewees ranged in age from 20 to 63 years old, which is consistent with the common setting for small-sample research (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample age statistics.

3.2. Street View Data Analytics Experiment Process

The “Research Report on the Development of Green Travel in Typical Cities (2024)” reveals that China’s slow-traffic system is plagued by problems such as mixed traffic including motor vehicles and non-motor vehicles and unclear road rights, which seriously reduce safety and comfort in the slow-traffic environment. In recent years, the number of electric bicycles in Changsha has soared, with the total number of registered electric bicycles reaching 1.957 million as of May 2025. Issues such as parking on the road, illegal driving, and speeding have also risen sharply. As a result, the demand for the construction and expansion of non-motorized vehicle lanes and the improvement of the environment has gradually increased. Therefore, this study selects slow traffic lanes in Changsha City as the object, representing a typical complex slow-traffic environment in a high-density city in China.

The experimental process was carried out in four main steps. Step 1: We screened road networks with more than four lanes in central Changsha based on OSM map information; then, we combined the cycling heatmaps uploaded by cycling enthusiasts on the Strava platform to filter out the street view collection routes. We collected street view images of the slow-moving system along the planned routes. Steps 2 and 3: Concurrently, three key perceptual indicators—safety, liveliness, and beauty—were obtained from 511 valid responses to an online questionnaire administered to participants. Steps 4 and 5: An experiment was conducted on a self-collected dataset of street view images, comparing machine-generated scores with manual scores provided by 27 female participants, aiming to examine the discrepancies between the two scoring methods and explore the underlying reasons for those discrepancies. Steps 5 and 6: We studied the differences between human and machine perceptions by comparing the scoring results, explored the impact mechanism of the slow-moving environment on women, and proposed construction strategies for a women-friendly slow-moving system (Figure 3).

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Street View Scoring Comparison: To ensure the authenticity and timeliness of street view data, urban street view images were collected from April to June 2025, adopting a perspective that simulates cycling. Insta360 GO3s portable cameras (Insta360, Shenzhen, China) were combined with mobile terminals (mobile phone GPS) and vehicle-mounted bracket systems to record street view videos along the roads in the study area. The recording routes were pre-planned using the Amap software (v.15.16.1), and shooting was conducted during both off-peak hours (13:00–16:30) and peak hours (17:00–19:00). Geographical location information was simultaneously recorded for all collected routes and stored in GPX (GPS Exchange Format), which includes latitude and longitude coordinates and timestamps, for subsequent spatial matching.

In the data preprocessing stage, we used Python 3.10 to process GPX trajectory files. The video data was frame-extracted at one frame per second, and the extracted images were matched with GPX points that had the same timestamps, achieving precise time-aligned spatial mapping. Time-driven sampling was adopted instead of distance-based sampling because vehicle speed could not be maintained at a constant level due to traffic conditions, intersections, and road characteristics. Under such conditions, distance-based sampling would require highly accurate speed and distance measurements and could lead to uneven temporal coverage. By contrast, frame extraction at regular time intervals provides a stable and consistent representation of the continuously recorded street environment. A total of 38,643 street view images were obtained, each with 1280 × 720 pixels.

To compare gender-neutral and female perceptions of street view images, this study adopts a road segment-based extreme value sampling method. First, the original urban road vector layer was preprocessed, and intersections were used to divide roads into minimal spatial units, resulting in 286 road segments with a total length of approximately 207.61 km, which served as the basic analysis units. Each image point was matched to its nearest road segment using spatial nearest-neighbor matching.

Machine-based perceptual scores were then generated for each street view image using a deep learning image perception model. In this study, machine scoring refers to the automated estimation of human-like perceptual judgments—specifically safety, liveliness, and beauty—directly from visual features of street view images. The model was pre-trained on the Place Pulse 2.0 dataset and adopts a Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture, following a transfer learning strategy from ImageNet. This approach has been widely used in recent studies to quantify subjective urban perceptions in a scalable and consistent manner [46,47].

For each road segment, images with the highest score, lowest score, and median machine-perceived scores were extracted as representative samples. This sampling method ensures that the extreme values of each road segment in the perception dimension are reflected, facilitating subsequent horizontal and human–machine perception comparisons.

3.4. Spatial Distribution of Machine Perception Scores

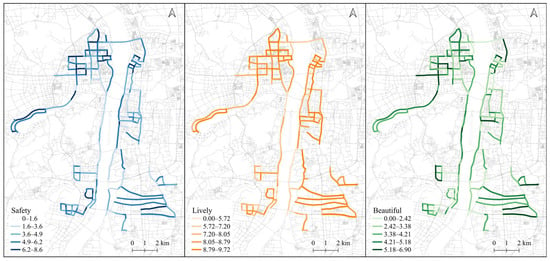

This subsection presents a descriptive spatial visualization of road segment median perceptual scores derived from a machine. As shown in Figure 4, median scores were classified using the natural breaks (Jenks) method and visualized with a sequential color scheme to emphasize intrinsic groupings and contrast in perceptual intensity across road segments.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of median perceptual scores.

Among the three perceptual dimensions, liveliness exhibits the strongest spatial clustering effect. High-score areas form large, continuous clusters, and the upper bound of liveliness scores (9.72) is substantially higher than that of the other dimensions, indicating a strong centripetal concentration of perceived urban vitality in core street areas. High safety scores display a more axial spatial pattern, extending from the central area toward the western and northeastern parts of the study area. This suggests that perceived safety is structured along major corridors rather than concentrated in compact clusters. In contrast, the beauty dimension shows the most compressed score range, with a maximum value of only 6.9. Spatially, beauty scores do not form large continuous high-value areas; instead, higher scores appear in a scattered and point-like manner, indicating localized improvements in perceived esthetic quality rather than broad spatial dominance.

Overall, areas with high liveliness and safety scores exhibit a relatively high degree of spatial overlap, whereas the spatial distribution of beauty scores shows a certain degree of mismatch with the other two dimensions. This pattern reveals an asynchronous development of urban spatial quality across different functional perception dimensions.

3.5. Difference Between Machine Scoring and Human Scoring

Building on the machine-based perception scores generated by the Place Pulse 2.0-based model, this subsection focuses on comparing machine scoring with female participants’ ratings. For extreme value sampling, three dimensions most relevant to this study—safety, liveliness, and beauty—were selected, and duplicate images were removed. Street view images taken inside tunnels and on viaducts were manually excluded. A total of 2245 images were obtained, forming a unified dataset for comparative analysis. These machine scores were then compared with female participants’ ratings to identify differences and preferences in streetscape perception (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of differences between manual and machine scoring and statistical significance analysis.

Table 2 shows that women’s ratings are higher than machine ratings for safety and beauty, while machine ratings are far higher than women’s ratings for liveliness. Specifically, the mean safety ratings range from 4.76 (machine) to 5.01 (manual), indicating a relatively close agreement in average perception. The liveliness dimension shows the widest range of mean values, from 3.57 (manual) to 7.59 (machine), reflecting a substantial divergence between human and machine evaluations. For the beauty dimension, mean ratings range from 3.96 (machine) to 4.64 (manual), suggesting moderate differences between the two scoring approaches. The standard deviation of manual ratings is less than 0.001, which indicates consensus among the 27 female participants, especially the high degree of overlap in the street view images that women rated low. In contrast, the machine ratings show a high degree of dispersion, which may be because the dataset used for model training was constructed based on scores from volunteers recruited globally, with each volunteer having different nationalities and life backgrounds. Paired-samples t-test results reveal significant gaps between manual ratings and machine ratings across the three dimensions (safety, liveliness, and beauty). This also indicates that there are obvious differences between women’s evaluations of the slow-moving environment and machine ratings in terms of focus points, influencing factors, and other aspects.

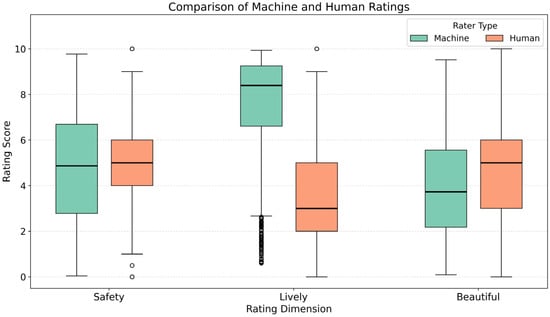

To systematically compare the distribution differences between machine scoring and manual scoring in different perceptual dimensions, box diagrams are used to visually analyze the scores of the safety, liveliness, and beauty dimensions (see Figure 5). Detailed summary statistics, including the mean, median, and quartiles, are reported in Table 3. Starting from the aspects of a centralized trend, dispersion degree, and outlier distribution, we explore the consistency and deviation of machine scoring and human scoring in subjective perception.

Figure 5.

Comparison of machine and human ratings.

Table 3.

Box plot-related values.

In the safety dimension, the human and machine scores showed a high degree of consistency in the centralized trend: the mean human score was 5.01 with a median of 5.00, and the mean machine score was 4.76 with a median of 4.87, showing small differences. However, there was a significant difference in the score discreteness between the two. The box of the machine score was significantly higher than the manual score, and its upper whisker line extended to nearly 10, which was higher than the upper whisker line of the manual score; for the lower whisker line, the machine score was close to 0. This shows that the machine model has more volatility in the safety evaluation, reflecting higher uncertainty, despite the close average.

The liveliness dimension has the largest difference between the machine and manual scores. The mean machine score is 7.59 with a median of 8.39, which are much higher than the manual score’s mean of 3.57 and median of 3.00, indicating that the model has a tendency to systematically overestimate this dimension. In the box plot, there is almost no overlap between the two scoring boxes, indicating that there is a fundamental deviation in the score distribution. The upper whisker line of the machine score extends to near 10, and the lower whisker line is higher than the manual score, but there are multiple outliers below it, reflecting the model’s extremely negative judgment of some samples. This may be due to the over-reliance of the algorithm on some visual features. Overall, the machine rating not only tends to be higher in the liveliness dimension but also has a large fluctuation range and dense outliers, reflecting its instability in subjective perception processing.

In the beauty dimension, the difference between machine ratings and human ratings is relatively small. The mean of human ratings is 4.64 and the median is 5.00, while the mean of machine ratings is 3.96 and the median is 3.73, which are more conservative values. The box height of machine ratings is slightly higher than that of human ratings. This result shows that although the machine model has a slight tendency to underestimate in this dimension, it shows good consistency with human ratings in scoring range control and concentration trends.

In summary, machine scoring exhibits different degrees of systematic bias in the three dimensions. In the liveliness dimension, machine scoring is much higher than that of manual scoring and fluctuates greatly, showing significant deviation; in the beauty dimension, it is more conservative and the difference is relatively controllable; and in the safety dimension, the average human–machine scores are the closest, but the discreteness difference cannot be ignored. These results show that the current scoring model is still quite different from humans when dealing with subjective dimensions such as perception, esthetics, and emotion.

4. Gender Differences Based on Questionnaire Survey

4.1. Questionnaire Overview

This study was conducted among urban cycling enthusiasts, urban residents, food delivery riders, and practitioners in related industries. A total of 511 online questionnaires were collected, including 303 responses from women and 208 from men. Distinct from the human–machine perception experiment in Section 3, this section presents gender differences in perceptions of the slow-moving system based on the questionnaire responses (n = 511).

4.2. Gender Differences in Spatial Perception of Slow-Moving Systems

Among the collected online questionnaires, men and women reported significantly different difficulties regarding the slow-moving system (Figure 6). Women generally reported more difficulties than men during cycling. Specifically, traffic safety is the primary concern for female cyclists, with a proportion as high as 78.22% compared to 65.87% for men. Women also reported notably higher proportions than men regarding issues such as unclear cycling routes and road congestion. This indicates that women may encounter more safety and environmental challenges during cycling, and relevant authorities should pay greater attention to the needs of female cyclists when improving cycling conditions.

Figure 6.

Differences in spatial elements of concern between men and women during cycling.

Significant gender differences were observed regarding spatial elements of non-motorized lanes (Figure 5). Women pay more attention to road obstacles (71.29%), sky openness (42.24%), and the green view index (44.88%), all of which are higher than men’s scores of 55.77%, 31.73%, and 33.65%, respectively, reflecting their focus on environmental safety and comfort. Men show relatively low attention to parking facilities (25.48%) and road enclosure (18.27%). Overall, women’s elements of concern are more diverse, and their emphasis on safety and comfort is particularly prominent.

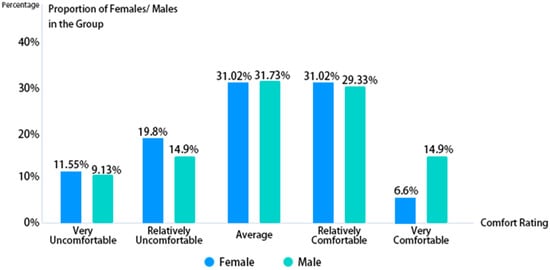

Overall, regarding satisfaction with slow-moving spaces, the proportion of women who consider such spaces “very uncomfortable” or “relatively uncomfortable” is far higher than that of men, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of satisfaction with slow-moving spaces between men and women.

5. Discussion

5.1. Differences Between Machine Perception and Female Perception from a Gender-Neutral Perspective

Machine scoring has limitations regarding safety. First, it over-relies on the model. For instance, it may give high scores based on elements such as zebra crossings, which do not necessarily improve the safety of non-motorized lanes and may even lead to collisions when there are no traffic lights. Second, it only makes judgments based on pixel shapes and lacks real-world reasoning. For example, it may misclassify moving vehicles that block the view as road obstacles and thus give low scores, which contradicts the logic of manual scoring.

Regarding liveliness scoring, the machine only refers to elements such as commercial shops and pedestrian and vehicle flow, which leads to significant discrepancies with the female perspective. Beyond the aforementioned elements, women also comprehensively consider humanistic environmental factors like street furniture and open spaces when judging liveliness.

Third, regarding beauty, the dataset training process involved volunteers from around the world, which also led to differences in the perception of “beauty”. When studying urban issues in Central China, it is necessary to train the dataset with reference to China’s national conditions. Obviously, there is a significant discrepancy between the conclusions of Place Pulse 2.0 and the manual ratings obtained from women.

5.2. Mechanism of Street View Scoring and Environmental Impact from a Female Perspective

First, in terms of safety, women’s evaluation criteria include not only elements such as zebra crossings, traffic lights, and orderly pedestrian and vehicle flow, but also clear scoring standards and expectations for the design of slow-moving systems. The top-ranked keyword is “physical segregation”. Women expect motor vehicles, non-motorized vehicles, and pedestrians to travel in their respective lanes, with no mutual interference between the three groups. Second, factors like sufficient lighting, unobstructed views, and moderately dense vegetation indicate that women’s demands for street safety are not limited to physical aspects, but also reflect the psychological impact of the visual environment. Finally, the participants mentioned that the width of slow-moving lanes, as well as monitoring and alarm devices, directly affect the scoring results. From the perspective of the gender social role theory, women often assume the role of family caregiver (involving picking up and dropping off children and accompanying elderly family members on trips), making their need for risk avoidance in the traffic environment both altruistic and comprehensive. The essence of physical partition and security facilities is to build a double safety barrier for themselves and their care objects. From the perspective of risk perception theory, women are more sensitive to uncontrollable risks than men. Scenes such as vegetation obstruction and dim lighting can intensify environmental uncertainty and insecurity; thus, the demand for visual transparency and environmental controllability is even stronger.

Second, regarding liveliness, women’s scoring criteria refer to the following elements: the density and newness/oldness of buildings; pedestrian density; and public facilities (garbage bins, public toilets, and rain shelters). Female participants who are urban residents stated that in addition to commercial shops and large shopping malls, which directly affect street liveliness, daily scenarios—such as trips with children or elderly family members—require the integration of appropriate resting nodes into the slow-moving system, along with supporting infrastructure like family-friendly and elderly-accessible public toilets. These street infrastructure facilities can directly determine the duration of urban residents’ leisure trips. In particular, when urban residents have no consumption needs, public nodes that allow for staying and recreational activities should be provided.

Third, regarding esthetics, first, women have a greater preference for slow-moving systems with unobstructed views. Second, there is a clear distinction between the “green coverage rate” and the “green view index”: women expect vegetation to provide shade while not blocking the line of sight. Finally, higher requirements are put forward for the tidiness of the built environment around roads, the pruning of vegetation, vegetation diversity, pavement variations, and the orderly arrangement of street furniture within the slow-moving system. From the perspective of environmental preference theory, humans have an instinctive preference for open, clean, and orderly environments. Women, who have long taken on the role of managing the household environment, are more sensitive to the tidiness and order of the space and thus have higher demands for the refined quality of the street environment. From the perspective of gender construction theory, women’s precise demand for balance between “green coverage rate and green view rate” is essentially a gendering expression of safety and esthetic needs. The traditional male-dominated space design often focuses on the esthetics of green landscapes while neglecting safety hazards. Women’s vigilance against vegetation blocking their view is a correction of the “gender blindness” in traditional space design.

6. Creating a Female-Friendly Slow-Moving System Space: Insights Based on Street View Image Scoring

6.1. Design of Female-Friendly Spatial Elements

First, regarding street furniture, priority should be given to addressing the shortage of family-friendly toilets in public washrooms to make up for this gap. Second, by leveraging well-positioned slow-moving space nodes, appropriate “safety zones” for women should be established to ensure they have completely independent safe spaces. Third, on-street alarm devices should be installed and the illumination of street lamps should be enhanced to guarantee women’s safety during travel around the clock. Finally, more seating benches should be added at suitable public space nodes, and these benches should be comfortable.

Second, regarding slow-moving street spaces, the widths of non-motorized lanes and sidewalks should be appropriately expanded. After that, at intersections and key nodes, road differentiation should be achieved through ground colors and height differences; for instance, color guidance is required within the scope of 20 m extending from crossroads to direct non-motorized vehicles into the correct lanes. Finally, according to spatial conditions, vegetation or railings should be reasonably used for physical space segregation to prevent mutual interference among the three groups (motor vehicle users, non-motorized vehicle users, and pedestrians) and reduce conflicts between motor vehicles and non-motorized vehicles.

6.2. Creation of Public Space Scenarios That Address Women’s Psychological Needs

First, a comprehensive monitoring system should be established to ensure continuous monitoring of slow-moving streets both at night and during the day. Second, when using green belts to separate motor vehicle lanes from non-motorized lanes, a combination of tall arbors (with no lateral branches below 3 m) and ground-covering plants should be adopted. This ensures unobstructed horizontal visibility for cyclists and pedestrians, creating visual safety. Third, node plazas and pocket parks should be set up near commercial plazas or urban natural landscapes. These nodes should be equipped with appropriate green plants (that do not block visibility), seating benches, and coat racks, among other facilities. This promotes full utilization of public spaces and provides necessary non-consumption venues for parent–child recreation. Fourth, street trees and roadside vegetation should be pruned in a timely manner. This not only contributes to the refined management of the city but also enhances women’s psychological sense of safety.

6.3. Functional Planning and Social Governance of a Socially Friendly Slow-Moving System for Women

Compared with the quality improvement and management of physical spaces, attention should also be paid to the cleanliness of public toilets and roadside trash cans. Additionally, for non-motorized vehicles that violate traffic rules by running red lights or jaywalking, traffic police should impose certain administrative penalties during peak hours—such as small fines or traffic police education with records kept on file—to serve as a warning to others and gradually correct improper usage habits of slow-moving lanes. After the construction of women’s “safety zones”, timely maintenance of these spaces should be carried out to ensure women’s absolute safety. Finally, at the social management level and against the background of pro-natal policies, the government should call on the public to be more tolerant of parent–child trips while enhancing the public’s sense of social responsibility.

7. Conclusions

In the process of improving the quality of urban slow-moving road spaces, women’s genuine needs should be taken seriously; the design enhancement strategies that address these needs should not be treated as a form of accommodation for vulnerable groups. Through qualitative research, interviews, and a comparative study of machine scoring and manual scoring results, this research provides an in-depth understanding of women’s real demands in using slow-moving systems and explores the mechanism by which the slow-moving system environment affects women. Specifically, the liveliness dimension shows the widest range of mean values, from 3.57 (manual) to 7.59 (machine), reflecting a substantial divergence between human and machine evaluations, while the beauty dimension has mean ratings ranging from 3.96 (machine) to 4.64 (manual), suggesting moderate differences between the two scoring approaches. Based on the conclusions of scoring comparisons and one-on-one interviews, three key aspects for improving the quality of the slow-moving system environment are proposed: improving the design of spatial elements required by society, creating women-friendly spatial scenarios, and optimizing the spatial planning and social governance of slow-moving systems. The environmental design of slow-moving streets bears the responsibility of guiding social lifestyles and creating social and cultural landscapes. Proactively addressing the significant challenges faced by women in their social and family roles during the process of urban transformation and upgrading is a crucial part of building a city and social environment characterized by spatial justice.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: (a) The differences between men and women in street view assessment were compared through an online questionnaire. Three important indicators were selected for slow-moving environmental street view assessment: safety, liveliness, and beauty. (b) By comparing the results of machine scoring and female manual scoring, we explored the influence mechanism of slow driving environments on women and demonstrated through data that the pre-trained model of machine scoring has gender imbalance issues. (c) We proposed a female-friendly update strategy for slow-moving spaces.

The limitations of this study are as follows: due to the large workload and long time required for manual scoring, this study focused on exploring the differences between machine scoring and female scoring, and data on male scoring was not introduced for the time being. In future research, we will continue to study the differences in street view perceptions between men and women.

Author Contributions

Z.Y.: conception, design of the work, the acquisition, Investigation, analysis, drafted the work, substantively revised. J.Z.: interpretation of data, the acquisition, software used in the work, the acquisition, substantively revised. Y.R.: the acquisition, Investigation, Layout. J.W.: the acquisition, Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Hunan Provincial Social Science Foundation (No. 24YBQ116); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42301537).

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [The street view images collected in the initial phase contain unobscured information, including vehicle license plate numbers and pedestrian facial features.] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Liu, Y.; Kwan, M.-P.; Wong, M.S.; Yu, C. Current methods for evaluating people’s exposure to green space: A scoping review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 338, 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Hu, F.; Hong, X.; Wang, W. Does Urban Green Space Pattern Affect Green Space Noise Reduction? Forests 2024, 15, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Global Sustainable Development Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, L.; Liu, F.; Deng, Y. Analysis of Traffic Conflicts on Slow-Moving Shared Paths in Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhou, W. Exploring the restorative benefits of Kuang-Ao features in urban slow-moving greenways based on the healthy city concept. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guney, M.; Tezcan, S.; Agin, C. Being able to exist in the city in defiance of planning: An examination on a woman-friendly city in Izmir-Konak. J. Plan. 2020, 30, 273–293. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.-I.; Choi, J.; An, H.; Chung, H.-Y. Gendering the smart city: A case study of Sejong City, Korea. Cities 2022, 120, 103422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.A.; Yang, L.C. Study on the Impact of Community Built Environment on Cycling Behavior from the Perspective of Differences in Travel Purposes. South Archit. 2025, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.G.; Liu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Jin, C.H.; Zhuang, X.J. Evaluation of Street Aesthetics and Analysis of Influencing Factors Based on Deep Learning and Multi-Source Data—A Case Study of Shanghai. Urban Plan. Int. 2023, 38, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.D.; Bo, D. The Impact of Shanghai’s Urban Built Environment on Residents’ Commuting Mode Choice. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2015, 70, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.X.; He, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.M.; Jin, S.S.; Wang, X.M.; Zhu, J.; Liu, S.C. Study on the Impact of Green Environment Exposure on Residents’ Mental Health—A Case Study of Nanjing. Prog. Geogr. 2020, 39, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.W.; Zhang, X. Study on the Diurnal Differences of Weekly Time-Space Behavior of Female Residents in the Suburbs of Beijing. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, A.N. Reflection and Enlightenment on Urban Spatial Planning from the Perspective of Feminist Geography. Planners 2022, 38, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Iturra, V. Gender differences in the travel patterns of Chilean workers: Travel time, number of trips, and public transport use. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 127, 104291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmelle, E.C.; Zhang, A.Z.; Fasullo, S.; Casas, I. Women in transport geography: Gender differences in research topics. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 127, 104281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Aria, M.; Mauriello, F.; Riccardi, M.R.; Montella, A. Systematic literature review of 10 years of cyclist safety research. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2023, 184, 106996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.Y.; Xie, T. Study on the Behavioral Characteristics and Experience of Cyclists on Scenic Greenways—A Case Study of Qiandao Lake Scenic Area. Sports Res. Educ. 2023, 38, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’hern, S.; Estgfaeller, N.; Stephens, A.N.; Useche, S.A. Bicycle rider behavior and crash involvement in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Y.; Chu, Z.M.; Zhu, J.A.; Dai, S. Analysis of Causes and Countermeasures for Electric Bicycle Traffic Accidents in China. Urban Transp. China 2021, 19, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopp, J.M.; Petretta, D.L. The urban sustainable development goal: Indicators, complexity and the politics of measuring cities. Cities 2017, 63, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.N.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.W. From Growth to Inclusion: Multi-Dimensional Connotation and Evaluation of Inclusive Cities from the Perspective of the Right to the City. J. Shanghai Adm. Inst. 2023, 24, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Macioszek, E.; Jurdana, I. Bicycle traffic in the cities. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transp. 2022, 117, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Study on Landscape Design of Non-Motorized Traffic Systems in Urban Traffic Roads. Highway 2023, 68, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.L. Exploration on Spatial Planning and Design of Urban Non-Motorized Traffic Systems in the Context of Smart Cities. Intell. Build. Smart City 2024, 11, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S.; Møller, M. E-bike safety: Individual-level factors and incident characteristics. J. Transp. Health 2016, 3, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhou, J.Y.; Li, G. Evolutionary Analysis of Influencing Factors on the Severity of Electric Bicycle Accidents from the Perspective of Technical Standard Updates. J. Transp. Syst. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2025, 25, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Psychology and climate change. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R992–R995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.; Chen, T.; Hem, B.J.; Hua, X.; Tang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yan, W.T.; Yuan, J.C.; Yang, X.C. Climate Adaptability and Spatial Quality Improvement. City Plan. Rev. 2023, 47, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.J.; Ye, C. From Women in the City to Women-Friendly Cities—A Review of Feminist Urban Studies. Urban Plan. Int. 2025, 40, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Yang, R.L.; Li, S.J. From Daily Living Space Design to Master Planning: An International Case Study of Gender—Friendly Urban Planning. Urban Plan. Int. 2025, 40, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Zhong, C.; Suel, E. Unpacking the perceived cycling safety of road environment using street view imagery and cycle accident data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 205, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, L.; Seo, S.H.; He, J.; Jung, T. Measuring perceived psychological stress in urban built environments using google street view and deep learning. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 891736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.M.; Zhou, S.H.; Xie, X.M. Daily Travel Purposes and Influencing Factors of Female Residents in Guangzhou from the Perspective of Feminist Geography. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.P. Analysis of Design Strategies for Women-Friendly Cities from a Female Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2024 Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Urban Destiny and Development Forum; School of Innovative Design, City University of Macau: Macau, China, 2024; pp. 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.W.; Weng, G.L.; Liu, Z.L. Feminist Perspective in the Study of Behavioral Space of Female Residents in Chinese Cities. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 18, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, J.; Cai, C. Plausible or misleading? Evaluating the adaption of the place pulse 2.0 dataset for predicting subjective perception in Chinese urban landscapes. Habitat Int. 2025, 157, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.F. Study on Activity Characteristics and Optimization Strategies of Community Space Based on Women’s Physical Health. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L. Study on Safety Optimization of Street Space in Longtan Industrial Park Area of Chengdu from the Perspective of Safety Perception. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, H.; Feng, H.; Yuan, Q. Spatial Element Identification and Planning Intervention Paths of Healthy Cities from a Fertility-Friendly Perspective. Urban Plan. Int. 2025, 40, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, A. Reflections on Urban Spatial Planning for Promoting Equal Development Opportunities for Women. Planners 2022, 38, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mcguckin, N.; Zmud, J.; Nakamoto, Y. Trip-chaining trends in the United States: Understanding travel behavior for policy making. Transp. Res. Rec. 2005, 1917, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Li, G.B.; Wang, Y. On the Lack of Planning for Women’s Needs and Its Responses—From a Feminist Perspective. Urban Plan. Int. 2014, 29, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Meng, F.X.; Jia, X.M. Environmental Evaluation of Underground Public Space in Central Urban Areas Based on Women’s Sense of Security—A Case Study of Chongqing. Contemp. Archit. 2022, 11, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X.; Wang, Y.J. A Gender-Comparative Study on Urban Residents’ Travel Modes. J. Shanxi Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2018, 45, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Women-Oriented Green Space Environmental Design. Planners 2008, 5, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, N.; Raskar, R.; Hidalgo, C.A. Cities are physical too: Using computer vision to measure the quality and impact of urban appearance. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Zeng, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W. Urban perception evaluation and street refinement governance supported by street view visual elements analysis. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.