Abstract

Within the global sustainable development agenda, Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) highlights improving the accessibility, quality, and learning experience of technical and vocational education and training (TVET). In China, students in vocational colleges often face greater disparities in academic preparation and access to educational resources than their peers in general higher education. Although artificial intelligence (AI) can provide additional learning support and help mitigate such inequalities, there is little empirical evidence on whether and how Gen-AI usage is associated with vocational students’ learning experiences and emotional outcomes, particularly academic anxiety. This study examines how Gen-AI usage is related to academic anxiety among Chinese vocational college students and explores the roles of class engagement and teacher support in this relationship. Drawing on Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, we analyse survey data from 511 students using structural equation modelling (SEM) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). The SEM results indicate that Gen-AI usage is associated with lower academic anxiety, with class engagement mediating this relationship. Teacher support for Gen-AI usage positively moderates the association between Gen-AI usage and class engagement. The fsQCA results further identify several configurations of conditions leading to low academic anxiety. These findings underscore AI’s potential to enhance learning quality and experiences in TVET and provide empirical support for advancing SDG 4 in vocational education contexts.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of AI technology has made its use in education a subject of significant academic and practical interest [1]. Generative AI (Gen-AI) has emerged as a powerful tool in the modern workplace, delivering significant benefits to both employees and organisations. Gen-AI also plays a significant role in education [2]. As an innovative educational and learning tool, Gen-AI has become an important pillar of education [2]. This aligns closely with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) [3], which calls for expanding access to equitable, high-quality learning opportunities and strengthening lifelong learning pathways [4]. Meanwhile, SDG 4 emphasises “ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education,” with a particular focus on leveraging technology to bridge learning resource gaps and enhance educational opportunities for disadvantaged groups [5]. Therefore, integrating Gen-AI into vocational education settings not only reflects trends in pedagogical innovation but also represents a critical pathway toward achieving educational equity and sustainable development. In this context, understanding how Gen-AI shapes students’ learning experiences is not only a technological or pedagogical issue but also an essential component of advancing educational sustainability and promoting learning equity.

Against this backdrop, numerous studies have begun to focus on the impact of Gen-AI on students’ actual learning outcomes and cognitive levels. The existing literature indicates that Gen-AI can improve students’ motivation, engagement, and academic performance in higher education [6]. Furthermore, some studies have also noted that students’ use of AI can not only provide learning feedback [7] but also offer psychological support, thereby improving mental health [8]. However, most existing research on the integration of Gen-AI and education has focused on higher education institutions and primary and secondary education, with insufficient attention to vocational education. In fact, vocational education is recognised by the United Nations as a vital component for achieving the goal of “enhancing employability skills and lifelong learning opportunities” under SDG4 [9,10]. However, compared to general higher education, the vocational education sector globally continues to face challenges such as insufficient resource allocation and weak learning support systems, making it a critical area requiring urgent attention in the advancement of SDG4. In China, vocational education is an important component of cultivating socially skilled talent [11], and the academic and mental health issues faced by students in this field have unique characteristics. Due to the influence of traditional societal and historical perspectives, the social recognition of vocational education may not be as high as that of higher education [12], thereby exacerbating psychological stress among vocational education students. Additionally, influenced by the stratified education system, vocational education students generally have weaker academic foundations and insufficient confidence in their learning, which can lead to greater academic anxiety [13]. Therefore, the academic anxiety issues faced by vocational education students are being highly addressed.

As an innovative and powerful learning tool [14], Gen-AI can play a significant role in student learning in vocational education. Some studies have begun to explore the application of Gen-AI in vocational education [5,15], such as the introduction of intelligent training systems and virtual simulation platforms by some higher vocational colleges to assist in skill development [16], and preliminary investigations into the role of Gen-AI in optimising classroom teaching organisation [17]. However, overall, the application of Gen-AI in vocational education is still mostly limited to teaching tools, lacking systematic attention to students’ actual usage and its impact on class engagement and mental health variables (such as academic anxiety). Therefore, the first research objective of this study is to explore how the use of Gen-AI affects academic anxiety among vocational education students.

The conservation of resources (COR) theory provides a powerful framework for understanding how Gen-AI use affects academic anxiety among vocational education students [18]. According to this theory, when faced with potential stress and challenges, individuals not only strive to prevent resource loss but also to acquire and utilise internal and external resources to increase their coping resources [18]. Students can access new learning resources and tools through instant feedback, diverse learning content, and interactive experiences provided by Gen-AI [19]. The input of these external resources helps stimulate students’ class engagement. Class engagement may play a key mediating role in the impact of Gen-AI usage on academic anxiety. Therefore, the second research objective of this study is to explore the mediating mechanism of class engagement in the impact of Gen-AI usage on academic anxiety among vocational education students within the framework of COR theory.

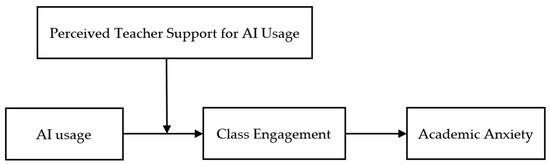

In addition, perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage is considered another important moderating factor. In educational settings, teachers not only organise classroom teaching but also guide students in adopting new technologies [20]. Students’ perceptions of teacher encouragement, guidance, and support for Gen-AI usage directly affect their trust in, enthusiasm for, and ability to use Gen-AI tools [21], which may moderate the positive impact of Gen-AI usage on class engagement. Previous studies have shown that when students receive greater technical support and emotional encouragement from teachers, they are more willing to transform external resources into class engagement [21], which, in turn, stimulates higher levels of learning motivation and concentration [22]. Based on this, the third research objective of this study is to examine the moderating role of perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage in the relationship between Gen-AI usage and class engagement. Based on the above discussion, the theoretical model of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model Diagram.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Gen-AI Usage and Academic Anxiety

In the field of education, Gen-AI usage usually refers to the extent to which Gen-AI is used to assist in completing learning tasks and achieving learning goals [23]. Academic anxiety usually refers to the emotional reactions of tension, uneasiness, and fear that individuals experience during learning activities due to pressure or concerns about academic failure [24]. It is often closely related to learning motivation, academic self-efficacy, and academic performance [25]. In China, students in the vocational education system often exhibit high levels of academic anxiety due to weak foundational learning, low confidence in learning, confusion about future career paths, and relatively low social recognition [13]. This usually manifests as concern about exam results, fear of failure, and high academic pressure. With the widespread use of Gen-AI in education [8], Gen-AI usage is likely to help reduce academic anxiety among vocational education students. On the one hand, the use of AI enables anytime, anywhere learning and personalised learning feedback tailored to individual needs, thereby improving learning motivation, efficiency, and outcomes [26], which in turn alleviates anxiety. On the other hand, the use of Gen-AI helps understand complex knowledge and complete complex learning tasks [27], further enhancing learning confidence and self-efficacy [28] and reducing anxiety levels. Overall, Gen-AI provides students with some academic assistance, which in turn helps alleviate the anxiety they experience. Therefore, we believe that the use of Gen-AI can alleviate the academic anxiety levels of vocational education students.

The resource gain perspective of the COR theory [18] provides an important theoretical basis for our view. The COR theory initially emphasised that resource loss exacerbates an individual’s stress and anxiety responses. This theory was expanded in subsequent studies, highlighting the important roles of resource acquisition, accumulation, and appreciation in an individual’s resistance to stress and sustained effort [29]. It also emphasises that individuals form a “resource enhancement spiral” after acquiring resources, meaning that those who obtain resources will continue to invest more resources to acquire even more, thereby experiencing less stress and anxiety [30]. In vocational education, we believe that Gen-AI usage itself constitutes an important technical resource [31], helping students acquire more knowledge and information resources [32]. The accumulation of these initial resources helps form a resource-value-added spiral, further increasing the cognitive and emotional resources of vocational education students, such as improving their sense of learning efficacy, autonomy, and control [33], and ultimately significantly alleviating academic anxiety. In summary, from a COR perspective, Gen-AI usage can be understood as an initial resource investment that enhances students’ cognitive, emotional, and control-related resources, thereby reducing academic anxiety. Building on this core logic, the following hypotheses further specify how these resource gains are translated into learning behaviours and emotional outcomes under different conditions. Therefore, we propose the first hypothesis:

H1.

Gen-AI usage is negatively correlated with academic anxiety.

2.2. Gen-AI Usage and Class Engagement

Class engagement refers to the degree to which students show focus and actively interact in class and is a key indicator of the quality of the learning process [34]. Higher class engagement not only helps students master knowledge but also improves teacher-student relationships, promotes critical thinking, and enhances problem-solving skills [35]. However, in China, vocational education students are often reluctant to participate in class [11] due to weak foundational learning and limited self-directed learning skills [12]. The emergence of Gen-AI can help improve this situation. First, the use of Gen-AI helps students develop personalised learning plans based on their learning situations, thereby improving learning relevance and confidence [36]. Research shows that increased learning confidence helps students participate more actively in class [11]. Second, the use of Gen-AI provides timely feedback, which helps reduce learning difficulties and associated anxiety [37] and enhances the willingness to express oneself in class. Finally, for vocational education students, the use of Gen-AI helps improve the efficiency of answering questions in class [20]. It further strengthens students’ and teachers’ willingness to interact, stimulates students’ interest in practice and motivation to explore, and encourages them to participate more actively in classroom activities [38,39]. Therefore, we believe that Gen-AI use by vocational education students can increase their class engagement.

Building on the resource-gain logic of the COR theory outlined above [18], this study further argues that Gen-AI usage promotes class engagement by encouraging vocational education students to invest their accumulated resources in classroom learning activities. Rather than reiterating the general stress-reduction mechanism of COR theory, this hypothesis focuses on class engagement as a behavioural manifestation of students’ active resource investment enabled by Gen-AI usage [9,10].

Specifically, Gen-AI usage in the classroom can lower engagement barriers and enhance students’ readiness to engage in learning activities. By providing timely feedback and adaptive learning support [21], Gen-AI helps students better understand instructional content and learning requirements [27], thereby increasing their confidence and sense of control in classroom settings. As a result, students are more willing to participate in discussions, practical activities, and collaborative tasks, translating the supportive functions of AI into more active class engagement [40]. Therefore, we propose the second hypothesis:

H2.

Gen-AI usage and class engagement are positively correlated.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Class Engagement in the Relationship Between Gen-AI Usage and Academic Anxiety

From the perspective of COR theory [18], class engagement can be understood as a key process through which learning-related resources are translated into psychological outcomes [23]. When students actively engage in classroom activities—such as interacting with teachers and peers or participating in practical learning tasks [26]—they receive clearer feedback, social affirmation, and a stronger sense of involvement in the learning process [41]. These experiences help reduce uncertainty and perceived academic pressure, thereby alleviating academic anxiety associated with fears of failure or falling behind [42].

In this sense, class engagement does not merely reflect students’ learning enthusiasm but also functions as a mediating mechanism that links Gen-AI use to academic anxiety [36]. By promoting higher levels of class engagement, Gen-AI usage facilitates the effective utilisation and consolidation of learning-related support, which in turn contributes to lower levels of academic anxiety [21,43]. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3.

Class engagement mediates the relationship between Gen-AI usage and academic anxiety.

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Perceived Teacher Support for Gen-AI Usage

Perceived teacher support refers to the extent to which students believe that teachers care about them and can provide assistance when needed [44]. In vocational education, teacher support has been shown to play a significant role in enhancing students’ motivation and engagement in learning [45]. This study argues that perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage is the extent to which students subjectively feel that teachers encourage, support, guide, or recognise their use of AI tools to aid learning in teaching activities. On the one hand, teachers who actively guide and support the use of AI can make students feel that AI is understood and encouraged [22]. This emotional support can significantly reduce students’ doubts and stress about technology use [46] and enhance their confidence and interest in classroom learning. On the other hand, the specific guidance and support provided by teachers are seen as key instrumental and informational support, which improve students’ motivation and ability to engage in class [43].

According to COR theory, perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage can be understood as an important social resource that enhances students’ sense of resource security when engaging in AI-assisted learning. When vocational education students perceive their teachers as supportive of Gen-AI usage, they are more likely to feel confident about investing their attention, time, and emotional commitment in AI-enabled learning activities [29]. Such support reduces students’ anxiety and uncertainty when experimenting with new learning technologies. It helps mitigate potential risks, such as hesitation or inappropriate reliance on AI tools [22,47], thereby reinforcing the positive resource-enhancing effects of Gen-AI usage on classroom engagement.

Moreover, teacher support for Gen-AI use extends beyond emotional affirmation and can be conceptualised as both a conditional and an instrumental resource [29]. As a conditional resource, teachers’ encouragement and recognition establish supportive norms that legitimise AI use in the classroom [41], creating an environment that allows exploration and experimentation without fear of misunderstanding or blame [30]. As an instrumental resource, teachers’ concrete guidance on how to use AI tools effectively helps students develop greater competence and control over Gen-AI applications [48], providing the necessary conditions for acquiring cognitive, skill-related, and control resources [49]. Under such supportive conditions, the resources enabled by Gen-AI usage are more likely to be translated into active class engagement, fostering a virtuous cycle of resource accumulation and learning engagement [30]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.

Perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage moderates the positive correlation between Gen-AI usage and class engagement. That is, the higher the perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage, the stronger the positive correlation between Gen-AI usage and class engagement.

In addition, since class engagement mediates the relationship between Gen-AI usage and academic anxiety, perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage moderates this relationship. Therefore, this study further shows that perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage can moderate the indirect effect of class engagement. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5.

Perceived teacher support for Gen-AI use moderates the indirect effect of Gen-AI use on academic anxiety via class engagement. Specifically, the higher the perceived teacher support for Gen-AI use, the stronger the indirect effect of Gen-AI use on academic anxiety via class engagement.

3. Methods

3.1. Samples and Collection

This study employed random sampling and distributed electronic questionnaires online to students at multiple vocational colleges in Sichuan, Chongqing, Henan, and Shanghai via the “Question Star” platform (Appendix A). At the beginning of the questionnaire, we explained the research objectives and the principle of voluntary engagement to participants, informing them that the data would be used solely for scientific research and that personal information would be strictly confidential. Those who did not consent could withdraw from the survey at any time. Before the formal survey, we included a screening question: “Do you use artificial intelligence in your daily learning and life?” Participants who selected “no” were excluded from the sample. To encourage engagement, after manual review, respondents were given a 4-yuan red envelope as a token of appreciation. To minimise common method bias, the questionnaire was distributed and collected in three rounds, each two weeks apart. Demographic variables and Gen-AI usage were collected at TIME 1 (T1). Perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage and class engagement were collected at TIME 2 (T2). Academic anxiety was collected at TIME 3 (T3). We matched the questionnaires using the last four digits of the mobile phone number and obtained a total of 564 matched data sets. To ensure data quality, we excluded invalid questionnaires that selected the same option 10 times in a row, resulting in 511 valid questionnaires and an efficiency rate of 90.6%.

Among the 511 questionnaires, 54.6% were from males and 45.4% from females. First-year students accounted for 16.2%, second-year students for 52.1%, and third-year students for 31.7%. The average age was 20.4 years. Other demographic information is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Variables.

3.2. Measurement

The measurement tools used in this study were selected based on the following criteria: (1) They were sourced from internationally recognised, authoritative journals and widely accepted. (2) Validated across multiple cultural contexts, including China, demonstrating good reliability and validity. Additionally, to enhance the accuracy and adaptability of the measurement items, this study employed the widely used “back-translation method” to repeatedly revise and refine the wording of the original scale, ultimately developing a 5-point Likert-scale questionnaire incorporating core variables. Options are labelled with numerical values: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Undecided, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree.

3.2.1. Main Variables

Gen-AI usage was measured using a three-item scale developed by Tang et al. [23], with example items such as “I use Gen-AI to complete most of my learning tasks.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.812.

Perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage was measured using an eight-item scale developed by Patrick et al. [50]. An example item is “When I need help using AI, I have a teacher I can rely on.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.950.

Class engagement was measured using a 12-item scale [34]. An example item is “I try my best to learn in class.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.927.

Academic anxiety was measured using a seven-item scale [25]. An example item is “Completing my homework makes me feel stressed.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.915.

3.2.2. Control Variables

This study, drawing on existing research on academic anxiety among vocational education students [51], controlled for gender, age, grade, and subject to avoid interference with the conclusions.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study utilised SPSS 27.0 software to examine descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and common method bias. AMOS 24.0 software was employed for confirmatory factor analysis, structural equation modelling, path coefficient testing, and testing for mediation and moderation effects. Among them, the mediation and moderation effect tests used the bias-corrected nonparametric percentile Bootstrap method to perform 2000 random repetitions on the sample (n = 511). The fsQCA 4.1 was used to perform fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis to test the configuration path of low academic anxiety.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test

Although this study employed a multi-time-point approach to collect data, common-method bias (CMB) may still be present, given the self-reported nature of the data. This study utilised SPSS 27.0 to conduct Harman’s single-factor analysis on four key variables. The results showed that the first principal component accounted for 39.172% of the variance, below the 40% threshold [52]. Additionally, this study employed a common-methods latent factor test, treating the common-method factor as a latent variable in the structural equation model. The results showed that the model fit indices did not improve significantly (ΔCFI = 0.008, ΔTLI = 0.006, ΔRMSEA = 0.002, ΔSRMR = 0.005). These methods indicate that the common method bias is not severe.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To test the discriminant validity of the variables, this study conducted confirmatory factor analysis. As shown in Table 2, the four-factor model fits better than alternative models, indicating that the four factors in the study have good discriminant validity and that the variables belong to different constructs.

Table 2.

Results of Confirmatory Factor Analyses.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 shows the results of the correlation analysis of each variable. The results indicate that the correlation coefficients among the main variables are significant, providing preliminary support for our hypothesis.

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of Variables.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

This study follows standard practice in social science and educational research by adopting a statistical significance level of 0.05 (α = 0.05) for hypothesis testing. To enhance the robustness and interpretability of findings, significant results at both the 0.01 and 0.001 levels are reported concurrently.

This study used AMOS 24.0 software to test the fit indices and related hypotheses of the structural equation model. The results of the fit index tests for the structural equation model are shown in Table 4. The primary fit indices of the structural equation model are all at acceptable levels (χ2/df = 2.224; CFI = 0.929; TLI = 0.924; RMSEA = 0.049; SRMR = 0.041), so the overall fit of the structural equation model is good.

Table 4.

Summary of Path-analytic Results.

As shown in Table 4, Gen-AI usage and academic anxiety show a negative correlation (B = −0.281, SE = 0.054, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. Gen-AI usage and class engagement showed a positive correlation (B = 0.257, SE = 0.053, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2.

This study used the Bootstrap method to test the mediating and moderating effects. The test results at Bootstrap = 2000 are shown in Table 5. The indirect effect of Gen-AI usage on academic anxiety through class engagement is significant (B = −0.086, SE = 0.020, p < 0.05), and the 95% confidence interval is [−0.129, −0.050], which does not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect is valid. Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Table 5.

Bootstrapping Results for Testing Mediation Effect and Moderated Mediation Effect.

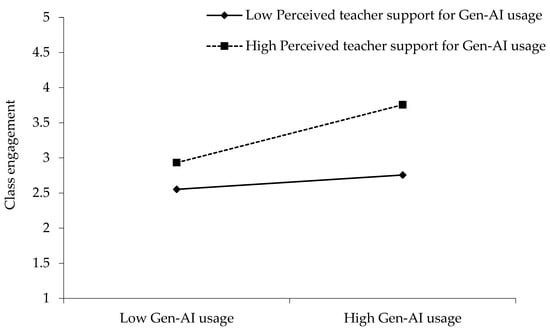

Table 4 shows that the interaction term between Gen-AI usage and perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage has a significant effect on class engagement (B = 0.155, SE = 0.049, p < 0.05), supporting Hypothesis 4. In addition, this study conducted a simple slope test, and the results are shown in Figure 2. When perceived teacher support for Gen-AI use is high, the correlation between Gen-AI use and class engagement is strong; when perceived teacher support for Gen-AI use is low, the correlation between Gen-AI use and class engagement is weak.

Figure 2.

The Moderating Effect of Class Engagement on the Relationship between Perceived Teacher Support for Gen-AI usage and Academic Anxiety.

This study used the Bootstrap method of structural equation modelling to conduct 2000 self-sampling tests of the moderated mediating effect. As shown in Table 5, when perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage was high, the indirect effect value of Gen-AI usage on academic anxiety through class engagement was 0.468, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.362, 0.585], which did not include 0, indicating that Gen-AI usage had a significant indirect effect on academic performance through class engagement. When perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage was low, the indirect effect value of Gen-AI usage on academic anxiety through class engagement was 0.222, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.100, 0.347], not including 0, indicating that the indirect effect of Gen-AI usage on academic anxiety through class engagement was not significant. The difference between the high and low groups is significant (B = 0.245, SE = 0.079, p < 0.05, 95% confidence interval = [0.095, 0.400]). This indicates that the moderated mediating effect holds, supporting Hypothesis 5.

4.5. Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA)

The SEM analysis results indicate that the use of Gen-AI is negatively correlated with the academic anxiety levels of vocational education students. SEM reflects the “net effect” between variables and is grounded in assumptions of linearity and symmetry. As a result, it has limitations in capturing the complex causal relationships that emerge from the interactions among multiple factors, particularly in contexts characterised by substantial individual differences. Academic anxiety among vocational education students may arise from various combinations of different conditions, and the same outcome might be achieved through different pathways.

To further unravel this complexity, this study introduces fsQCA as a crucial complement to SEM. From a configuration perspective, fsQCA identifies multiple combinations of sufficient conditions that lead to low academic anxiety. It reveals causal asymmetry and equivalent polysexuality, thereby addressing SEM’s limitations in interpreting multi-path causal relationships. This enhances the richness of theoretical explanations and the robustness of research conclusions.

4.5.1. Variable Selection and Calibration

In the study, we demonstrated significant correlations among Gen-AI usage, perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage, class engagement, and academic anxiety. Therefore, this section conducts a configurational analysis of low academic anxiety using Gen-AI usage, perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage, and class engagement as antecedent conditions.

Based on previous research [53], we first calculated the mean values of the variables Gen-AI usage, perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage, class engagement, and academic anxiety. Then we used the quartile method to calculate the 75%, 50%, and 25% measurement values as the three anchor thresholds.

After data calibration, an analysis of the necessity and sufficiency of every single antecedent condition revealed that, as shown in Table 6, none of the single antecedent conditions met the absolute necessity criterion (consistency scores were all less than 0.9); simultaneously, none of the antecedent conditions were sufficient conditions for the outcome. Therefore, this study required combining multiple antecedent conditions for configurational analysis.

Table 6.

Results of the Necessary Conditions Analysis.

4.5.2. fsQCA Results

This study utilised the fsQCA 4.1 software for analysis and constructed a truth table. First, the consistency threshold was set to 0.8, the PRI consistency threshold to 0.75, and the case frequency threshold to 1 to construct the truth table. In which “🗹” indicates that the antecedent condition exists, “🗷” indicates that the antecedent condition does not exist, and “blank” indicates that the condition may or may not exist in the configuration. The results are shown in Table 7. This study found three patterns of low academic anxiety. The first is the combination of Gen-AI usage and perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage, the second is the combination of Gen-AI usage and class engagement, and the third is the combination of perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage and class engagement. The consistency level of each path across the three configurations in this study was greater than 0.8. The overall consistency was also greater than 0.8, with an overall coverage of 0.821 (>0.5), indicating that the three combination paths are sufficient conditions for low academic anxiety among students, that is, all configurations are effective forms of result realisation. The overall model has strong explanatory power. The above findings indicate that Gen-AI usage, perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage, and class engagement do not all need to reach high levels; the presence of any two of these conditions can still lead to low academic performance.

Table 7.

Configuration Analysis Results.

4.5.3. Robustness Test

To test the robustness of the configuration paths influencing low academic anxiety and determine whether the explanatory power of the analysis results is stable, this study used a variable consistency threshold to verify this, that is, by raising the original consistency threshold level of the case. We raised the consistency value from 0.8 to 0.9, reran the software, and obtained new conditional configuration results for low academic anxiety that were consistent with those in Table 7, indicating that the results had not changed. The obtained conditional configuration path has good robustness in explaining low academic anxiety.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Significance

Firstly, AI technology has been highly touted in education for its powerful capabilities [54], but its mechanisms of impact on student mental health, particularly academic anxiety, require further exploration [7]. This study systematically examined the effects of Gen-AI usage on academic anxiety among vocational education students, validating hypothesis 1: Gen-AI usage is negatively correlated with academic anxiety. These findings not only broaden the research perspective of educational technology in the field of mental health but also provide empirical evidence for the interdisciplinary integration of AI and educational psychology [9,10]. Furthermore, by focusing on the vocational education population, this study addresses recent calls for research attention to the learning foundation disparities and unique psychological adaptation challenges faced by this group.

Secondly, this study validated the mediating role of class engagement in the relationship between Gen-AI usage and academic anxiety. It validated hypothesis 2: Gen-AI usage and classroom engagement exhibit a positive correlation, and confirmed hypothesis 3: classroom engagement mediates the relationship between Gen-AI usage and academic anxiety. These findings deepen understanding of the psychological mechanisms in digital learning environments. Vocational education students often face multiple pressures, including weak learning foundations and insufficient learning confidence [13]. The classroom serves not only as a vital arena for acquiring knowledge and skills but also as a crucial context for their psychological adaptation. Findings indicate that AI facilitates students’ transition from passive learning to active engagement by providing personalised support, immediate feedback, and contextualised learning resources [20].

Notably, AI does not exert a stable direct effect on academic anxiety; its positive impact primarily depends on whether students can invest attention, time, and emotional resources in the class [20]. This finding further illustrates, from the COR theory perspective, that technological resources are more likely to be latent or conditional [10]. Only when effectively activated and transformed into learning engagement can they yield psychological benefits [55]. This result partially revises the implicit assumption in existing research that AI functions as a “direct psychological resource” [5].

Thirdly, this study reveals the moderating role of teacher support, validating hypothesis 4: perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage moderates the relationship between Gen-AI usage and class engagement. These findings expand the extent of prior research on teacher support in the context of educational technology by revealing the moderating effect of perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage. Findings indicate that teachers’ encouragement, recognition, and guidance regarding Gen-AI usage can strengthen students’ positive perceptions of AI and facilitate the translation of technological resources into actual classroom engagement behaviours [21]. Previous research indicates that in contexts lacking clear norms or effective guidance, Gen-AI usage may also trigger student anxieties regarding technological dependency, ambiguous evaluation criteria, or the legitimacy of learning methods, thereby diminishing its positive effects [42]. Our findings highlight teachers’ role as “boundary regulators” in AI-enhanced learning, rather than mere technology promoters.

Finally, this study used the fsQCA method to reveal the multiple conditions that trigger low academic anxiety, enriching the understanding of the complexity of the causes of academic anxiety among vocational education students. Results indicate that low academic anxiety can be achieved not only through simultaneously high levels of Gen-AI usage, class engagement, and teacher support, but also through various resource combinations that may exert equivalent effects. These findings complement and extend beyond the average effect mechanisms revealed by SEM, indicating that AI is not a prerequisite for alleviating academic anxiety but can form substitute or complementary relationships with other learning and contextual resources. This outcome not only validates COR theory’s perspectives on resource equivalence and multi-path dependency but also reminds researchers to avoid simplistic linear causal interpretations when understanding psychological adaptation in digital learning environments.

5.2. Practical Significance

First, this study reveals that AI can serve as a significant learning support resource with positive effects. However, existing research indicates that AI’s beneficial impact depends on appropriate guidance and standardised use [49]. This suggests that vocational education administrators should view AI’s tool-like nature rationally, deploying it as a supplementary resource to enhance student engagement in classroom learning and alleviate academic anxiety [49]. Students should be guided to correctly understand the functions and limitations of AI in learning, fostering a rational and cautious—rather than dependent—attitude toward using AI tools [27]. Therefore, administrators must provide corresponding institutional and technical support to help students use AI efficiently and responsibly [56]. This includes conducting AI awareness and application training, establishing AI learning spaces or learning communities, and providing necessary equipment and platform support to reduce anxiety risks stemming from technical barriers or skill disparities.

Second, fsQCA analysis revealed multiple configuration pathways leading to low academic anxiety, suggesting that single or homogeneous intervention strategies are impractical. Significant variations exist across classes or student groups regarding AI proficiency, classroom engagement foundations, and perceived teacher support. Administrators should therefore flexibly allocate technological and instructional resources to specific contexts, rather than solely emphasising high-level investment in a single factor. This finding also alerts practitioners to address disparities in AI resource accessibility and usage proficiency across student groups, preventing existing learning pressures from intensifying due to the digital divide or technological mismatches.

Third, the results indicate that teacher support for Gen-AI usage significantly amplifies its positive impact on class engagement. Thus, teachers should transcend the role of mere “permitters” of technology use and instead become facilitators and regulators of AI-assisted learning. On one hand, teachers should adopt an open and inclusive attitude toward students’ use of Gen-AI tools in class [49]. By explicitly expressing approval and support, they can foster a safe learning environment, reducing students’ psychological burden stemming from fears of rejection or misunderstanding [1]. On the other hand, teachers must provide necessary demonstrations and guidance to help students understand the appropriate contexts and potential limitations of Gen-AI tools, preventing misuse or overreliance [48]. For instance, teachers can demonstrate appropriate Gen-AI applications in smart Q&A, information retrieval, writing support, and lesson planning, while providing targeted feedback on students’ Gen-AI use through classroom practice.

Finally, for vocational education students, it is important to proactively understand and use AI technology to assist learning, take the initiative to use intelligent technology to strengthen their learning foundation and build confidence in class engagement, and alleviate their academic anxiety. On the one hand, they should correctly understand the role and functions of Gen-AI, overcome their fear of the unknown and the perceived technical barriers to using Gen-AI technology [2], recognise that AI-assisted learning can play a positive role, and embrace Gen-AI with an open and confident attitude [16]. On the other hand, they should actively learn to use AI technology, such as by watching online courses and consulting teachers and classmates, to understand the diverse tools and related search commands, to fully leverage Gen-AI technology’s powerful capabilities to support learning and class engagement.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

The main limitations of this study should be acknowledged and addressed in future research. First, all data were collected through student self-reports. Although multiple statistical procedures were employed to assess CMB, and the results suggested that CMB was not severe, its complete elimination cannot be guaranteed. Future studies may adopt more objective or multi-source measurement approaches, such as teacher evaluations of class engagement and academic anxiety, to further enhance data robustness. Second, although the survey samples were drawn from vocational education institutions across multiple regions in China, including Sichuan, Chongqing, and Shanghai, thereby improving the representativeness of the sample, the geographic coverage remains limited. Moreover, the participants in this study were exclusively vocational college students, and whether the observed relationships can be generalised to other student populations (e.g., general higher education students or secondary school students) remains an open question. Meanwhile, the research samples primarily originate from China’s vocational education environment, and the generalizability of the findings to other educational systems or cultural contexts requires further validation. Third, while this study employed a multi-wave data collection design and applied the fsQCA method to infer causal relationships, the data remain essentially cross-sectional, which restricts strong causal interpretations of the proposed model. Future research could adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to capture dynamic changes in academic anxiety and provide stronger causal evidence. Fourth, this study examined the moderating role of perceived teacher support in the relationship between AI usage and learning outcomes. Future research may further explore additional individual- and organisational-level factors to extend the explanatory scope of the model. Finally, the findings of this study are primarily applicable to learning contexts involving generative AI usage, and their applicability to other forms of AI tools or educational applications should be examined in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H., J.L. and H.H.; Formal analysis, J.L. and B.H.; Funding acquisition, X.H.; Investigation, X.H., J.L. and H.H.; Methodology, X.H., J.L., H.H. and B.H.; Project administration, X.H.; Software, J.L., H.H. and B.H.; Supervision, X.H. and H.H.; Validation, J.L., H.H. and B.H.; Visualisation, X.H.; Writing—original draft, J.L., H.H. and B.H.; Writing—review and editing, X.H. and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by the 2025 Chengdu Soft Science Research Project, “Assessment of High-Level Talent Supply-Demand Matching and Training Pathways for the Intelligent Industry in the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Zone” (Grant No. 2025-RK00-00138-ZF); and the 2025 Project of the 14th Five-Year Plan of the Sichuan Provincial Social Sciences Research Program, “Digital and Intelligent–Driven Pathways and Effects of Promoting High-Quality and Balanced Development of Compulsory Education at the County Level in Sichuan Province” (Grant No. SC25T001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Institute for Advanced Study in Humanities and Social Sciences, Chengdu University (approval date: 5 September 2024, approval number: CDUSSD202402).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- Gen-AI usage

- 1

- I use AI to fulfil most of my learning functions.

- 2

- I use AI most of the time.

- 3

- I use AI when making major learning decisions.

- Perceived teacher support for Gen-AI usage

- 1

- I have a teacher who really understands how I feel

- 2

- I have a teacher who tries to help me when I am sad or upset

- 3

- I have a teacher I can count on when I need help with the usage of AI

- 4

- I have a teacher who respects my opinion

- 5

- I have a teacher who cares about how well I learn about the usage of AI.

- 6

- I have a teacher who likes to look at my work out of concern.

- 7

- I have a teacher who wants me to do my best in school.

- 8

- I have a teacher who will help me learn how to use AI.

- Class engagement

- 1

- I try hard to do well in this class.

- 2

- In this class, I work as hard as I can.

- 3

- I pay attention in class.

- 4

- When I am in this class, I feel good.

- 5

- When we work on something in this class, I feel interested.

- 6

- I enjoy learning new things in this class.

- 7

- Before starting an assignment for this class, I try to figure out the best way to do it.

- 8

- In this class, I keep track of how much I understand the work, not just if I am getting the right answers.

- 9

- If what I am working on in this class is difficult for me to understand, I figure out how to change the way I learn the material.

- 10

- During this class, I ask questions to help me learn.

- 11

- I let the teacher know what I am interested in.

- 12

- During this class, I express my preferences and opinions.

- Academic anxiety

- 1

- To finish my homework makes me feel pressure.

- 2

- My homework is a burden for me.

- 3

- I have a lot of homework to do.

- 4

- Learning tasks in my class are so difficult.

- 5

- In classes, I must learn something hard for me to understand.

- 6

- Exams are usually difficult for me.

- 7

- To solve the problems assigned by teachers is so difficult.

References

- Ma, K.; Zhang, Y.; Hui, B. How Does AI Affect College? The Impact of Gen-AI Usage in College Teaching on Students’ Innovative Behaviour and Well-Being. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahri, N.A.; Yahaya, N.; Al-Rahmi, W.M. Exploring the Influence of ChatGPT on Student Academic Success and Career Readiness. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 8877–8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Hardy, I. Imagining Language Policy Enactment in a Context of Secrecy: SDG4 and Ethnic Minorities in Laos. J. Educ. Policy 2023, 38, 849–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tu, C. Advancing Sustainable Development Goal 4 through a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: The Development and Validation of a Student-Centred Educational Quality Scale in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storonyanska, I.; Benovska, L.; Patytska, K.; Ivashko, O.; Chulipa, I. Redesigning Sustainable Vocational Education Systems to Respond to Global Economic Trends and Labour Market Demands: Evidence from EU Countries on SDGs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Jam, F.A.; Khan, T.I. Is It Harmful or Helpful? Examining the Causes and Consequences of Generative Gen-AI usage among University Students. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Nan, D.; Kim, J.H. Beyond Learning with Cold Machine: Interpersonal Communication Skills as Anthropomorphic Cue of AI Instructor. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Min, Q. Exploring Continued Usage of an AI Teaching Assistant among University Students: A Temporal Distance Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2024, 61, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y. Artificial Intelligence, Technological Innovation, and Employment Transformation for Sustainable Development: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokus, G. A Multi-Stakeholder Vision for Designing AI-Empowered Teacher Education: Exploring Key Components for Sustainable Institutional Change. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hardy, I. Understanding Chinese National Vocational Education Reform: A Critical Policy Analysis. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2023, 75, 1055–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. ‘A Cultured Man Is Not a Tool’: The Impact of Confucian Legacies on the Standing of Vocational Education in China. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2024, 76, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Blair, E. Exploring Conceptualisations of Vocational Education in China: How the Hierarchical Education System Mirrors Social Hierarchy. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2024, 45, 778–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.M.; Koopman, J.; Yam, K.C.; Cremer, D.D.; Zhang, J.H.; Reynders, P. The Self-Regulatory Consequences of Dependence on Intelligent Machines at Work: Evidence from Field and Experimental Studies. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 62, 721–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedungadi, P.; Tang, K.-Y.; Raman, R. The Transformative Power of Generative Artificial Intelligence for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of Quality Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, K.T.; Rahman, J.M.; Islam, M.R.; Dewan, S.M.R. ChatGPT and Mental Health: Friends or Foes? Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Peng, S. The Usage of AI in Teaching and Students’ Creativity: The Mediating Role of Learning Engagement and the Moderating Role of AI Literacy. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualising Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Lin, H.X.; Kong, Y.R. Challenge or Hindrance? How and When Organisational Artificial Intelligence Adoption Influences Employee Job Crafting. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 113987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naffi, N.; Montufar, C.S. Autoformation en outils d’intelligence artificielle générative: Un levier pour guider et optimiser la conception pédagogique. Rev. Int. Technol. Pédagogie Univ. 2025, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, S.I. Enhancing Academic Advising with Real-Time Class Engagement Using AI. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wu, X.; Deris, F.D. Exploring EFL Learners’ Positive Emotions, Technostress and Psychological Well-Being in AI-Assisted Language Instruction With/Without Teacher Support in Malaysia. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.M.; Koopman, J.; McClean, S.T.; Zhang, J.H.; Li, C.H.; Cremer, D.D.; Lu, Y.Z.; Ng, C.T.S. When Conscientious Employees Meet Intelligent Machines: An Integrative Approach Inspired by Complementarity Theory and Role Theory. Acad. Manag. J. 2022, 65, 1019–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shi, L.; Tian, T.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, X.; Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; Ou, J. Associations between Academic Stress and Depressive Symptoms Mediated by Anxiety Symptoms and Hopelessness among Chinese College Students. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, Z. Chinese High School Students’ Academic Stress and Depressive Symptoms: Gender and School Climate as Moderators. Stress Health 2012, 28, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Wang, C.-C. Why Do Graduate Students Use Generative AI in Thesis Writing? The Influence of Self-Efficacy, Time Pressure, and Trust. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 12071–12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. Can Artificial Intelligence Give a Hand to Open and Distributed Learning? A Probe into the State of Undergraduate Students’ Academic Emotions and Test Anxiety in Learning via ChatGPT. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2024, 25, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdenhofa, O.; Kinderis, R.; Berjozkina, G. AI as a Creative Partner: How Artificial Intelligence Impacts Student Creativity and Innovation: Case Study of Students from Latvia, Ukraine and Spain. Balt. J. Econ. Stud. 2024, 10, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Johnson, R.J.; Ennis, N.; Jackson, A.P. Resource Loss, Resource Gain, and Emotional Outcomes among Inner City Women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 632–643, Correction in J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 248. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Stevens, N.R.; Zalta, A.K. Expanding the Science of Resilience: Conserving Resources in the Aid of Adaptation. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.K.Y. AI as the Therapist: Student Insights on the Challenges of Using Generative AI for School Mental Health Frameworks. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajt, B.; Schiller, E. ChatGPT in Academia: University Students’ Attitudes towards the Use of ChatGPT and Plagiarism. J. Acad. Ethics 2025, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Chuang, Y.-W. Artificial Intelligence Self-Efficacy: Scale Development and Validation. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 4785–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Lee, W. Students’ Class Engagement Produces Longitudinal Changes in Classroom Motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.K.; Uddin, M.S. From Data to Insights: Using Gradient Boosting Classifier to Optimise Student Engagement in Online Classes with Explainable AI. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 18089–18130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, Y. Exploring the Effects of Artificial Intelligence Application on EFL Students’ Academic Engagement and Emotional Experiences: A Mixed-Methods Study. Eur. J. Educ. 2025, 60, e12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, F.; Abedi, F.Y.; Ozek Gunyel, F.; Karadeniz, D.; Kuzgun, Y. Incorporating AI in Foreign Language Education: An Investigation into ChatGPT’s Effect on Foreign Language Learners. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 19343–19366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D.; Kapshuk, Y.; Dekel, H. Promoting Perceived Creativity and Innovative Behaviour: Benefits of Future Problem-Solving Programs for Higher Education Students. Think. Ski. Creat. 2023, 47, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Wei, Z. Shaping the Future of Higher Education: A Technology Usage Study on Generative AI Innovations. Information 2025, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okulich-Kazarin, V.; Artyukhov, A.; Skowron, Ł.; Artyukhova, N.; Wołowiec, T. Will AI Become a Threat to Higher Education Sustainability? A Study of Students’ Views. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichterman, B.; Banihashem, S.K.; Verstappen, M.; Schipper, M.; Waisvisz, P.; Noroozi, O.; van Ginkel, S. Can AI feedback stand alone for fostering students’ presentation performance? A comparison of AI-only versus teacher-supported AI feedback. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahi, K.; Hawlader, S.; Hicks, E.; Zaman, A.; Phan, V. Enhancing Active Learning through Collaboration between Human Teachers and Generative AI. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Deng, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Can Generative Artificial Intelligence Be a Good Teaching Assistant?—An Empirical Analysis Based on Generative AI-Assisted Teaching. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2025, 41, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, E.; Moos, R. Social Environment of Junior High and High-School Classrooms. J. Educ. Psychol. 1973, 65, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, J.; Liu, X. A ‘Useful’ Vocational Education English Language Teacher by Any Other Name. Short Stories of Teacher Identity Construction and Reconstruction in Vocational Education in China. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2024, 76, 1205–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, Q. Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Integrated Educational Applications and College Students’ Creativity and Academic Emotions: Students and Teachers’ Perceptions and Attitudes. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ginkel, S.; Gulikers, J.; Biemans, H.; Mulder, M. Towards a Set of Design Principles for Developing Oral Presentation Competence: A Synthesis of Research in Higher Education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 14, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-M.; Shen, T.-C.; Shen, T.-C.; Shen, C.-H. Teachers’ Adoption of AI-Supported Teaching Behaviour and Its Influencing Factors: Using Structural Equation Modelling. J. Comput. Educ. 2024, 12, 853–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.; Ka-mun Sum, C.; Shun-mun Wong, H. Does Perceived Risk of AI Matter? Teachers’ AI Literacy and Institutional Support: Perspective from Self-Determination Theory. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 23271–23293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.; Ryan, A.M.; Kaplan, A. Early Adolescents’ Perceptions of the Classroom Social Environment, Motivational Beliefs, and Engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, M. AI-Empowered Applications Effects on EFL Learners’ Engagement in the Classroom and Academic Procrastination. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioural Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Shao, B.; Zhang, Y. How Does Interactivity Shape Users’ Continuance Intention of Intelligent Voice Assistants? Evidence from SEM and fsQCA. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 867–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.-F.; Shen, W.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Ling, X.; Li, W. Exploring Chinese teachers’ concerns about teaching artificial intelligence: The role of knowledge and perceived social good. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestin, G.; Miller, K.; Klales, A.; Milbourne, T.; Ponti, G. AI Tutoring Outperforms In-Class Active Learning: An RCT Introducing a Novel Research-Based Design in an Authentic Educational Setting. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, C.S.; Mathur, S.; Vishnoi, S.K. Is ChatGPT Enhancing Youth’s Learning, Engagement and Satisfaction? J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.