Abstract

Lithium–sulfur batteries (LSBs) are a promising emerging technology due to their high energy density, low-cost materials, and safety. However, their environmental sustainability is not yet well understood. This study conducted a prospective life cycle assessment (LCA) on two patented LSB models, using data from patents as the inventory: one with a standard sulfur cathode and another with a graphene–sulfur composite (GSC). The assessment is conducted for a functional unit of 1 Wh of produced electricity, adopting a cradle-to-gate system boundary and a prospective time horizon set to 2035. The LSB GSC model battery showed significantly better performance in terms of climate change and fossil depletion, with a 42% lower impact, mainly due to a reduction in the lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) content from 1205 mg Wh−1 to 250 mg Wh−1. However, the GSC model also had significant drawbacks, showing a 93% higher metal depletion and 49% higher water depletion than the standard sulfur battery. Building on an established patent-based prospective LCA approach, this work applies patent-derived quantitative inventories and patent-informed eco-design analysis to support environmentally informed design decisions for emerging LSB technologies prior to large-scale commercialization.

1. Introduction

The global energy transition urgently demands next-generation energy storage solutions, and the lithium–sulfur battery (LSB) has emerged as a leading candidate. Due to its high theoretical energy density, the use of abundant and cost-effective materials, and enhanced safety, the LSB is considered a key enabling technology for decarbonization across strategic sectors [1]. Its applications range from long-range electric road transport [2] and electric aircraft [3] to grid storage for renewable energies [4]. The significant industrial and academic interest is supported by clear indicators: the global LSB market is projected to grow from USD 0.4 billion in 2020 to USD 5.6 billion by 2030 [5]. From a technical perspective, LSBs exhibit a theoretical energy density of approximately 2500–2600 Wh kg−1, which is much higher than that of conventional lithium-ion batteries [6,7]. In reported laboratory-scale and pre-industrial LSB configurations, sulfur loadings have been reported as 2.5 mg.cm−2 and 5 mg.cm−2 [8], and as a range of 1.5–15 mg.cm−2 [9]. Major public funding initiatives, such as the HELIS, ALISE, and LISA projects in the European Union and the ARPA-E and Battery500 Consortium in the United States, are driving advancements.

However, as LSB technology advances from laboratory-scale prototypes towards commercial viability, its environmental sustainability must be rigorously and proactively assessed. Given that LSBs are currently characterized by a relatively low technology readiness level (TRL) [10], a traditional life cycle assessment (LCA) cannot be applied. Instead, a prospective LCA approach is required to analyze this technologically immature product and predict its environmental impacts at large-scale diffusion [11]. A key challenge in prospective LCA is selecting reliable, representative documentary sources that reflect the future industrial state-of-the-art rather than current laboratory practices [12].

This reveals a critical gap in the existing literature. An analysis of published LCA studies shows a reliance on a very limited number of sources for life cycle inventories (LCIs). For instance, [13] mainly retrieves their inventory from another article, which in turn adopts an inventory proposed by [14] for a 2010 lithium-ion battery scenario. Other studies, such as [15] and [9], model the LSB using the inventory of [16] without modification. Consequently, original primary data are almost exclusively drawn from a narrow set of studies [7,16,17], some of which are based on coin cells created in a purely academic context and are distant from industrial experimentation. This concentration of sources raises a fundamental question regarding whether current LCA models are sufficiently representative of the diversity and industrial orientation of recent technological developments in the LSB field.

The main weakness of existing battery LCA models therefore does not lie in the mathematical structure of the impact calculation itself, but in the limited and non-representative parameterization of the inventory. Laboratory-scale battery models typically assume fixed material ratios, simplified electrode architectures, and electrolyte formulations that are not necessarily representative of future industrial designs [18]. As a result, existing models are poorly suited to capture design variability, material substitution strategies, and eco-design solutions that are actively being developed at the industrial level.

Building on previously established patent-based prospective LCA frameworks [19,20], this study applies and extends this approach to LSBs, an emerging technology for which industrially relevant environmental data remain scarce. While the prior literature has typically assessed the environmental impacts of LSBs using limited academic datasets, or proposed sustainability improvements disconnected from quantitative environmental assessments, this paper demonstrates how patent-derived quantitative inventories can complement and extend conventional academic data by capturing forward-looking, industrially oriented design solutions.

Rather than proposing a new methodological framework, the contribution of this study lies in the application of an established patent-based prospective LCA approach to a new technological domain. The added value of this application resides in its ability to reveal environmental hotspots and material-related trade-offs that are not fully captured by laboratory-based LCAs. In addition, the same patent corpus used to construct the LCI is systematically analyzed to identify eco-design strategies aimed at mitigating the most significant environmental impacts identified by the LCA results. This creates a direct and operational link between environmental assessment and industrial innovation pathways.

Although a wide range of battery chemistries are currently investigated in both industry and academia [21,22], this study intentionally focuses exclusively on lithium–sulfur batteries. LSBs are widely recognized as a leading post-lithium-ion technology due to their exceptionally high theoretical energy density, reliance on abundant materials, and potential to reduce dependence on critical metals such as cobalt and nickel.

Lithium-ion batteries are therefore not evaluated as an alternative technology in this study but are referenced solely as a technological and environmental benchmark to contextualize the maturity level, performance limitations, and sustainability challenges of LSBs, in line with the established literature. Other battery chemistries are excluded because they either target different application domains, rely on fundamentally different electrochemical mechanisms, or lack sufficient patent-level quantitative disclosure to support a robust and consistent patent-based prospective LCI. Expanding the scope to multiple battery families would compromise the methodological coherence and depth required for a prospective assessment of low-TRL technologies.

Accordingly, this paper should be understood as an application-driven contribution rather than a methodological innovation. Its novelty lies in extending a validated patent-based prospective LCA framework to the LSB domain and in integrating quantitative environmental assessment with patent-derived eco-design insights to inform sustainability-oriented technology development prior to large-scale commercialization.

Therefore, this paper has two primary objectives. First, to assess the environmental impacts of patented LSBs by modeling the LCI with data extracted directly from a broad selection of recent patents. Second, to leverage the same patent documents to identify the eco-design solutions that the industry is already developing to mitigate the most significant environmental impacts, even before large-scale commercialization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Life Cycle Assessment

The environmental impacts of the LSB sulfur and LSB graphene–sulfur composite (GSC) are quantified using the prospective LCA methodology [11]. This approach follows the standard LCA framework defined in ISO 14040 [23] and ISO 14044 [24], while extending it to assess technologies expected to be developed and implemented in the future. The prospective LCA framework enables the evaluation of environmental impacts associated with future products at an anticipated temporal context.

The steps of the methodology are as follows.

- Definition of the goal and scope, including the identification of the technical systems under assessment, the functional unit, and the system boundaries.

- Compilation of a prospective LCI to identify sources of environmental impacts across system components and life cycle stages, incorporating data from patents related to future LSB technologies.

- Impact assessment using selected environmental impact indicators.

- Interpretation and discussion of the results.

The following sections describe each methodological step in detail.

2.2. Compared Products

Two models of LSBs are analyzed in this study, which differ only in the type of active material in the cathode. In the LSB sulfur (model 1), the active material is pure sulfur, while in the LSB GSC (model 2), the active material is GSC [6]. The LSB GSC was developed to give LSB sulfur great chemical stability and better conductivity, although the synthesis and preparation of the graphene/sulfur composite is an additional process that must be carried out in the production of the LSB. However, the potential advantages of the LSB GSC over LSB sulfur have yet to be demonstrated on a large scale, outside of academic testing, and according to a multi-criteria perspective [25]. For this reason, these two LSB models are analyzed in this study.

The other materials of the two compared LSBs are the same. Carbon black (CB) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) complete the cathode structure. CB is used to improve electrical conductivity and structural stability, while PVDF is a binder that contributes to the adhesion of sulfur and SB/graphene particles, structural stability, and electrical conductivity. The anode is made of lithium metal foil. The electrolyte is made up of lithium salts, i.e., lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) and lithium nitrate (LiNO3), and an organic solvent, i.e., a mixture of 1,2-Dimethoxyethane (DME) and 1,3-Dioxolane (DOL). In particular, the organic solvent facilitates the electrical and chemical stability of the electrolyte, the ionic conductivity, and the overall compatibility with the battery materials. The separator consists of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polypropylene (PP). Finally, the current collectors between the electrodes (cathode and anode) and the external circuit are made of conductive materials such as copper, nickel, or stainless steel.

2.3. Scope, Functional Unit, and System Boundary

The time scope of this analysis is set to the year 2035, representing the anticipated commercialization timeframe for the LSBs described in patents filed between 2014 and 2024. This projection is based on the average development and market adoption period for battery-related innovations [26]. The geographical scope is defined as the European context, reflecting typical regional conditions and regulatory frameworks. The functional unit for the study is the production of 1 Wh of electricity using an LSB, serving as the basis for the comparative assessment. In this cradle-to-gate prospective assessment, the functional unit is employed as a normalization basis for comparing material intensity and production-stage environmental impacts across battery configurations, rather than as a representation of delivered energy over the battery’s lifetime. Accordingly, the use of a 1 Wh functional unit does not imply any assumption of equal cycle life, durability, or degradation behavior among the assessed battery designs. It is not intended to represent lifetime energy throughput or service delivered by the battery.

The system boundary is of the cradle-to-gate type, including the manufacturing of all the materials constituting the core of the LSB, which consists of a cathode, anode, electrolyte, and separator. The use-phase and end-of-life stages are excluded from the quantitative assessment due to the lack of reliable, comparable, and patent-based data on battery lifetime, degradation behavior, and recycling pathways for emerging LSB technologies. Cycle life, degradation mechanisms, and recyclability are nevertheless recognized as dominant drivers of battery sustainability and may outweigh production-stage impacts. As a result, the scope of the analysis is intentionally limited to production-stage impacts.

Consequently, the results of this study should be interpreted strictly as cradle-to-gate environmental trade-offs associated with material selection and battery design, rather than as indicators of overall life cycle sustainability or long-term performance. Any conclusions regarding environmental superiority are therefore confined to the production phase and do not extend to the use or end-of-life stages.

The scope of this study is limited to LSB technologies. No other battery chemistry is modeled or compared within the LCA. This restriction is intentional and reflects the objective of applying a patent-based prospective LCA framework to a single emerging technology at a low TRL, where design variability and industrial uncertainty are already high. Including multiple battery families would introduce additional layers of heterogeneity in functional performance, system boundaries, and maturity assumptions, which would hinder meaningful comparison and weaken the analytical focus of the study.

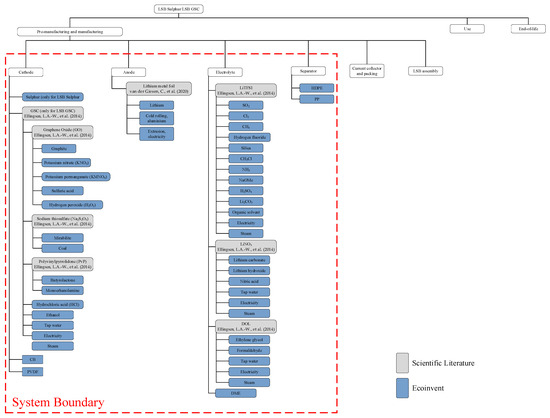

A graphical representation of the system boundary is provided in Figure 1 along with all the materials considered.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting the key steps in the LSB production process. This figure illustrates the materials involved and the system boundaries considered in the study. The values corresponding to the blue boxes were taken from the Ecoinvent database, while gray boxes were found in the academic literature [12,14].

2.4. Inventory

To guarantee time consistency to the analysis, all the collected documents used to model the compared LSBs are published between 2014 and 2024.

The patents about LSB sulfur and LSB GSC were collected by applying the suggestions provided by [19,20] in their methods for systematically retrieving patents and data for inventories in prospective LCA. This methodology has already been applied to carry out the patent-based prospective LCA of a similar product, i.e., a solid oxide fuel cell [20]. First, the search query “(SULFUR+ OR SULFUR+ OR “LI-S”)” was launched within the title, abstract, and keywords in the entire world’s patent database using Orbit by Questel. Only granted patents, currently alive, and those having the publication of the application from 2014 to today, were preserved in order to increase the reliability of testimony interest by the patent owner. All the retrieved patents were then filtered on the basis of their relevance and we only retained those reporting numerical data relating to the mass of the constituent materials of the LSBs included in the system boundary.

Since reliance on patent data raises questions about the reliability and completeness of the inventory used for the LCA, patent analysis and data extraction were conducted in a systematic way, taking advantage of the author’s vast experience in the patent field. In fact, as demonstrated in [20] through case examples, the involvement of a patent analyst is crucial for patent-based prospective LCAs, given that patents may not always provide exhaustive or entirely accurate data on material usage or environmental impacts. This is because data disseminated in the patent literature can be more challenging to locate and more susceptible to noise compared to those from the scientific literature. In addition, in this study, following the methodology of [19], only inventory data were extracted from patents after a rigorous selection of sources, while environmental impacts were not directly taken from patents. Instead, they were meticulously calculated using the LCA methodology and up-to-date impact databases.

Tables S1 and S2 report all data extracted from the patents of LSB sulfur and LSB GSC.

To compare the results, the impacts of an LSB sulfur modeled as in [13] and an LSB GSC modeled as in [16] were also assessed.

In the inventory of the patented LSB sulfur and LSB GSC, reported in Table 1, the mass of each constituting material is the arithmetic mean of all the masses of the same material retrieved from the patents. The use of arithmetic means is not intended to suggest that patented designs represent a statistically distributed, equally probable, or scalable set of industrial products. Patent documents describe alternative embodiments and design spaces rather than realizable production statistics; accordingly, the arithmetic mean is employed here as a normalization strategy to synthesize heterogeneous patented configurations into a single, comparable LCI. The resulting inventory should therefore be interpreted as a central design envelope within the patented solution space, rather than as a physically realizable average battery. This level of abstraction is consistent with the objectives of prospective LCAs for low-TRL technologies, which aim to support comparative analysis and environmental hotspot identification rather than to represent a specific commercial product.

Table 1.

Inventory of LSB sulfur and LSB GSC models based on patents and the literature.

For the patented LSB sulfur model, quantitative patent data were available for all materials within the system boundary. For the patented LSB GSC model, however, quantitative patent data for selected electrolyte components, namely LiTFSI, LiNO3, DME, and DOL, were not consistently reported across the analyzed patents. To avoid introducing speculative assumptions or incomplete parameterization, these components were conservatively modeled using the literature values reported in [16], which represent a widely adopted reference inventory for LSB electrolyte formulations. This results in a hybrid inventory construction for the patented LSB GSC model, where patent-derived data are used wherever sufficient quantitative information is available, and literature-based values are applied only for parameters lacking adequate patent coverage.

The production processes of the materials constituting the LSB sulfur and LSB GSC were modeled using data from the scientific literature [15,16] and Ecoinvent v3.8 datasets.

In Figure 1, the flowchart for LSB sulfur/LSB GSC production is provided.

2.5. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

The impacts of the compared products were assessed using the ReCiPe midpoint (H) model [27]. The interpretation of the results was made by comparing LSB sulfur and LSB GSC from patents and from articles.

The life cycle impact assessment is based on a deterministic mass-based inventory–impact formulation, consistent with ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 standards [23,24]. For each battery configuration (j) and each impact category (k), the total environmental impact is calculated using Equation (1).

where is the impact score for category k associated with battery model j, is the mass of material i normalized to the functional unit (mg/Wh), is the ReCiPe midpoint (H) characterization factor for material i and impact category k, and n is the total number of materials included within the system boundary.

The average impacts of each technology were determined using the average data of each parameter and were considered in order to offer a comparison between the different products. In this way, having considered many sources from which to extract data, with average data and average impacts, it is possible to increase the significance of the analysis and level out specific differences. This is especially true in the context of prospective LCA, when the technologies are not mature and the data are not forecast [28].

To support interpretation and hotspot identification, the contribution of each material, i, to a given impact category, k, was calculated as a percentage of the total impact using Equation (2).

where represents the relative contribution (%) of material i to impact category k for battery model j.

All percentage differences discussed in Section 3 are calculated as relative changes between impact scores using Equation (3).

where and are the impact scores of the two compared battery configurations for impact category k.

All the specific impact coefficients used to assess the impacts of the materials considered and processes are reported in Tables S10–S18.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents and discusses the results of the prospective LCA within the cradle-to-gate system boundary defined in Section 2.3. All results reported below refer exclusively to production-stage environmental impacts and should be interpreted as material- and design-related trade-offs occurring during battery manufacturing. Given the exclusion of the use phase and end-of-life, the results do not support conclusions regarding the overall life cycle sustainability, operational performance, or long-term environmental benefits of the assessed battery configurations.

3.1. Impact Comparison

The impacts for each model of LSB sulfur and LSB GSC derived from patents and the literature according to the ReCiPe midpoint (H) model are reported in Tables S6–S9.

All percentage differences reported in this section represent relative changes between point-estimate inventory values and are intended to illustrate comparative trends between battery configurations. These values need to be interpreted together with the uncertainty analysis presented in Section 3.2, which reflects the variability associated with inventory data and modeling assumptions.

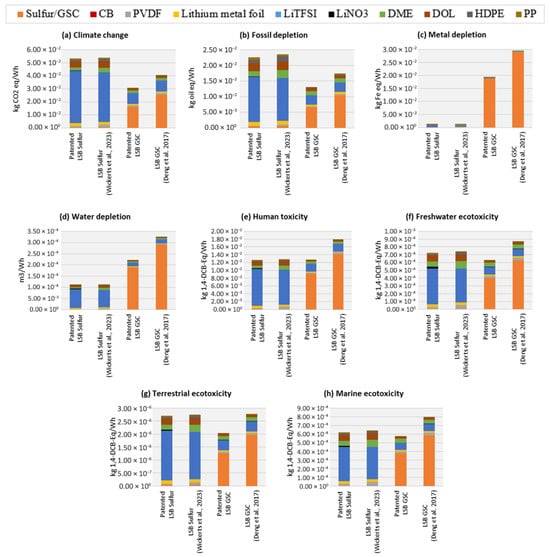

Figure 2 presents a structured comparison of the environmental impacts of the considered LSBs, organized into three homogeneous analytical dimensions. The environmental dimension includes climate change and fossil depletion (Figure 2a,b), while the material and technological dimension comprises metal depletion and water depletion (Figure 2c,d); all four impact categories are identified as key indicators for LSB assessment in line with [13]. The anthropocentric–human dimension is addressed through toxicity-related indicators, including human toxicity, freshwater ecotoxicity, terrestrial ecotoxicity, and marine ecotoxicity (Figure 2e–h), which are particularly relevant for battery technologies due to their potential implications for human health and ecosystems.

Figure 2.

Comparative environmental impacts of LSB models, broken down by material contributions, compared to [13] and [16]. This visualization highlights the primary drivers of (a) climate change, (b) fossil depletion, (c) metal depletion, (d) water depletion, (e) human toxicity, (f) freshwater toxicity, (g) terrestrial ecotoxicity, and (h) marine ecotoxicity for each battery type.

3.1.1. Environmental Dimension

The climate change and fossil depletion of the patented LSB GSC are significantly lower (42%) than those of the patented LSB sulfur (Figure 2a,b). This is mainly due to the drastic reduction, when moving from the patented LSB sulfur to the patented LSB GSC, of climate change (140%) and fossil depletion (120%) associated with LiTFSI. These reductions largely balance the increases in climate change (71%) and fossil depletion (67%) that occur when switching from sulfur to the GSC.

Compared to the studies in the literature, both the patented LSB sulfur and the patented LSB GSC have lower climate change and fossil depletion. The patented LSB sulfur reduces climate change by 1% and fossil depletion by 4% compared to the LSB sulfur of [13]. This is due to the reductions in these two impact categories, especially in DME, PVDF, and HDPE, which balance the increases in LiTFSI and PP. The patented LSB GSC reduces climate change by 24% and fossil depletion by 25% compared to the LSB GSC of [16]. This is due to the reduction in the same impact categories in the GSC, equal to 88% and 81%, respectively, and of the CB, equal to 4% and 9%, respectively.

3.1.2. Materials and Technological Dimension

The total metal depletion of the patented LSB sulfur is 93% lower than that of the patented LSB GSC (Figure 2c). This difference is due to the fact that the metal depletion of GSC in the patented LSB GSC is 105% higher than that of sulfur in the patented LSB sulfur. The only advantage arising by switching from the patented LSB sulfur to the patented LSB GSC is the 3% decrease in the metal depletion of LiTFSI. Compared to the LSB GSC of [16], the patented LSB GSC allows us to reduce the total metal depletion by 35%, thanks exclusively to the 100% reduction in the metal depletion associated with the GSC, moving from the first to the second.

When switching from the patented LSB GSC to the patented LSB sulfur, the total water depletion decreases by 49% (Figure 2d). This is mainly due to the 176% reduction that occurs when switching from the GSC to sulfur in the cathode, which largely compensates for the increase in water depletion of LiTFSI, which is greater than 61% in the patented LSB sulfur. Finally, the total water depletion of the patented LSB GSC is 32% lower than that of the LSB GSC of [16]. This is almost exclusively due to the water depletion of the GSC, which decreases by 98%.

3.1.3. Anthropocentric–Human Dimension

Across all toxicity categories, a significant contribution comes from specific materials such as CB, PVDF, lithium metal foil, and LiTFSI. In fact, these materials are known for their environmental and health impacts. The results indicate that patented Li-S sulfur batteries tend to have lower toxicity impacts compared to the LSB GSC batteries from the literature [16], particularly in human toxicity and ecotoxicity categories. The variation between different studies suggests that the choice of materials and processing methods can significantly influence the environmental burden. Compared to [16], the patented Li-S batteries analyzed here seem to perform better in terms of toxicity impacts. This improvement may stem from advancements in material synthesis, reduced reliance on highly toxic solvents, or optimization in the battery architecture. The results align with the recent literature suggesting that Li-S batteries can have a lower toxicity impact than traditional lithium-ion batteries, primarily due to the replacement of nickel and cobalt, which are notorious for their high toxicity and environmental burden. However, the continued presence of polymer binders, electrolytes, and lithium salts remains a challenge [29].

In summary, the results show that the transition from sulfur to the GSC significantly increases the impacts associated with the active part of the cathode. This is mainly due to the production process of graphene and the consumption of electrical and thermal energy to chemically weld to other materials in the GSC [9,16,30]. However, the use of the GSC allows for a reduction in the quantity of LiTFSI to be used in the electrolyte, which allows for a considerable reduction in the overall climate change and fossil depletion of the LSB GSC, making it more sustainable than the LSB sulfur in relation to these impact categories. In fact, the incorporation of graphene into the LSB cathode enhances conductivity by maximizing sulfur utilization, mitigates the polysulfide shuttle effect, and provides structural stability. These improvements are critical to increasing the energy density and duration of LSBs, reducing the cost at the same time [25].

Beyond numerical comparisons of environmental impacts, a qualitative analysis provides deeper insight into why certain materials contribute to better environmental performance in LSBs. The composition and processing of key materials, such as sulfur, the GSC, electrolytes, and binders, influence their environmental footprint in distinct ways.

Sulfur, as a cathode material, is abundant and requires minimal processing, contributing to its relatively lower environmental impact. In contrast, the GSC has a higher environmental impact due to the energy-intensive synthesis of graphene. The production of graphene often involves high-temperature chemical vapor deposition or chemical exfoliation processes, both of which require substantial energy inputs and generate emissions. Consequently, while the GSC offers performance advantages, its inclusion in LSBs leads to increased metal depletion and water consumption impacts compared to sulfur alone [31].

Electrolyte composition also plays a significant role in determining the overall environmental impact. The use of LiTFSI has been identified as a major contributor to climate change and fossil depletion impacts due to its complex synthesis process and reliance on fluorinated compounds. The reduction in LiTFSI in the patented LSB models aligns with industry efforts to optimize electrolyte formulations and minimize the use of high-impact materials. Similar trends are observed in emerging battery technologies, where researchers are looking for alternative electrolyte compositions to improve sustainability without compromising the electrochemical performance [32].

Binders and conductive additives further influence the environmental performance of LSBs. PVDF is derived from fluoropolymers, which have notable environmental concerns related to their production and disposal [33]. CB has a relatively moderate impact but still contributes to fossil resource depletion due to its petroleum-based origin. The eco-design of binders, such as water-based or bio-derived polymers, reflects an industry-wide effort to reduce reliance on fluorinated materials and improve the life cycle sustainability of next-generation batteries [34].

These material choices highlight the inherent trade-offs in battery design. While sulfur-based cathodes reduce environmental impacts in some categories, the introduction of the GSC improves battery performance at the cost of higher resource depletion. Similarly, electrolyte optimization is essential to mitigate climate change and toxicity impacts, but viable alternatives to LiTFSI remain under active research [13].

While this study excludes the use-phase and end-of-life stages from the quantitative assessment, it is important to acknowledge their potential influence on the overall sustainability of LSBs. The exclusion is a deliberate methodological choice aligned with the prospective, patent-based LCA approach, which focuses on the production phase due to the limited availability of reliable operational and disposal data in the patent literature. Nonetheless, a qualitative discussion provides valuable insights into these life cycle stages.

The environmental performance of LSBs during the use phase largely depends on factors such as energy efficiency, cycle life, and degradation mechanisms. Compared to lithium-ion batteries, LSBs offer higher theoretical energy density, which could lead to lower energy consumption per functional unit over the battery’s lifetime. However, challenges such as the polysulfide shuttle effect and lithium metal dendrite formation could lead to a shorter cycle life and increased material consumption due to premature failure or additional electrolyte replenishment. Thus, addressing these challenges through improved electrolyte formulations and cathode designs could significantly enhance the sustainability of LSBs during operation [35].

The recyclability of LSBs remains a critical concern, particularly due to the complexity of recovering key materials such as sulfur, lithium, and graphene-based composites. While sulfur is abundant and has a relatively low environmental burden, the separation of sulfur from carbon matrices in composite cathodes presents technical challenges. Moreover, the presence of fluorinated electrolytes (e.g., LiTFSI) introduces additional environmental risks due to the persistence and potential toxicity of fluorinated compounds. Future advancements in closed-loop recycling strategies, solvent-free electrode processing, and alternative binder formulations could mitigate some of these end-of-life concerns [36].

To enhance the reliability of the inventory data extracted from patents, a comparative analysis was conducted with the existing academic literature and industry reports. While patents provide insight into the latest technological developments, they may not always include comprehensive environmental data. Therefore, cross-referencing with peer-reviewed studies and industrial sources helps to contextualize the findings. Several key parameters from the patent-derived inventory were compared with values reported in LCA studies on LSB. For instance, the specific material compositions and processing conditions in this study were contrasted with those in [7,13,16].

In general, material compositions in patents showed alignment with academic studies, though some differences emerged. Concerning the electrolyte composition, patents tended to report lower LiTFSI content compared to earlier studies, reflecting industry efforts to optimize electrolyte formulations. Regarding the active material ratios, the sulfur-to-carbon ratios in the patented cathodes differed slightly from the values in the literature, likely due to improvements in cathode design and conductivity-enhancement strategies. Energy consumption in the literature studies, often based on laboratory-scale processes, is reported to be higher per unit due to small-scale inefficiencies, whereas the patents suggest more industrially viable pathways.

Industry reports, such as market analyses on Li-S battery commercialization [5], were also considered. These sources provide context on expected production trends, material sourcing, and scalability challenges. The patent-based LCA results align with industry trends, indicating a growing focus on reducing electrolyte toxicity through material substitution. In addition, the increasing adoption of graphene–sulfur composites for cathode stabilization is a trend reflected in both patents and industry developments. Finally, the continued challenge of recyclability and resource depletion is noted in both patents and industry projections.

3.2. Uncertainties Analysis

The prospective nature of the LCA performed in this study introduces uncertainties due to the reliance on patent data and the projection of future environmental impacts [11,12,19]. To strengthen the study’s reliability, a comprehensive approach to uncertainty management was adopted by integrating uncertainty quantification, sensitivity analysis, and scenario modeling [12,30].

The variability of the impacts was analyzed by calculating the standard deviation and relative variation across the different categories. In this regard, climate change, fossil depletion, freshwater toxicity, marine toxicity, and terrestrial toxicity exhibit the highest relative variability, exceeding 200%. This suggests a strong influence of data assumptions and methodological choices on the final outcomes.

To identify the key drivers of uncertainty, a correlation analysis was conducted between the inventory parameters and impact assessment results. The findings indicate that no single parameter exhibits a dominant effect due to the correlation coefficient (r > 0.6). However, moderate correlations were observed for selected parameters, suggesting that impact variation arises from a combination of multiple factors rather than a single dominant contributor.

Finally, to assess the potential range of environmental impacts, three distinct scenarios were considered:

- Optimistic Scenario: assumes the lowest observed impact values, reflecting potential technological advancements and efficiency improvements.

- Realistic Scenario: represents the mean impact values, providing a balanced estimate based on current projections.

- Pessimistic Scenario: considers the highest observed impact values, capturing potential worst-case assumptions.

The results indicate that in the pessimistic scenario, environmental impacts can be up to 50 times higher than the realistic estimate, underscoring the critical role of assumptions in prospective assessments. At the same time, the optimistic scenario highlights potential avenues for improvement through process optimization and material innovation.

3.3. Eco-Design Solutions from Patent Analysis

The analysis of the considered patented LSBs allows for the identification of several eco-design solutions aimed at reducing the environmental impacts associated with graphene–sulfur composite (GSC) cathodes and lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI), which were identified in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 as the dominant contributors to cradle-to-gate impacts. The environmental relevance of the identified eco-design solutions is quantitatively supported by the patent-derived inventory data reported in Tables S1 and S2, which explicitly document how patented design strategies modify material loadings per unit of stored energy (mg/Wh), areal loadings (mg/cm2), electrolyte-to-sulfur ratios (µL/mg), and separator properties.

3.3.1. Cathode Porosity Optimization

To reduce the mass of the GSC, the porosity of the specific surface area and the pore volume in the graphene part of the GSC are optimized according to certain ranges, so as to better distribute the sulfur powder (patents EP3813156 and EP3940822). The principle behind this solution is that a better distribution of the sulfur powder allows for an increase in the electrical conductivity and therefore the performance of the LSB at the same mass, or to guarantee the same conductivity if the mass of the carbon part decreases [8]. In particular, EP3813156 reduces the graphene mass by maintaining the sulfur–carbon mass ratio equal to 0.45.

The quantitative impact of porosity optimization is reflected in Table S2, where the patented GSC loadings range from approximately 232 to 609 mg/Wh, demonstrating that cathode architecture directly controls the amount of graphene-containing material required per unit of stored energy. This variability directly explains the increased metal depletion and water depletion impacts observed for GSC-based configurations in Section 3.1.

With porosity optimization, in addition to the reduction in graphene, improving the efficiency of the LSB, it is also possible to reduce LiTFSI while guaranteeing the same performance [37]; this option is exploited by EP3940822. This effect is quantitatively captured in Tables S1 and S2 through lower LiTFSI areal loadings (mg/cm2) and reduced electrolyte-to-sulfur ratios (µL/mg), which directly influence climate change and fossil depletion impacts at the production stage.

Some patented LSBs sulfur also optimize the porosity of the carbon in the cathode to better distribute the sulfur and improve the conductivity and efficiency of the LSB, thus reducing the mass of LiTFSI (US20180190973, CN112928255, US20240145706, EP4231433, US20180083289, and EP4032137). As given in Table S1, sulfur loadings vary widely (approximately 214–1190 mg/Wh), illustrating how cathode design strategies directly modify material intensity per Wh and associated production-stage impacts.

An alternative to porosity exploitation is the optimization of the carbon particle size in order to improve the mixing and arrangement of the sulfur in the cathode, improving the LSB performance and reducing LiTFSI (CN112909248 and KR10-2020-0094883). This strategy is reflected in Table S1 by reduced electrolyte-to-sulfur ratios and LiTFSI areal loadings for optimized cathode formulations.

3.3.2. Core–Shell Structure Sulfur

Another solution to reduce the mass of the GSC is to act on a higher level of detail, on the shape of the GSC instead of the porosity, with the same objective of distributing the sulfur powder in an optimal way to improve the electrical conductivity. The most considered option is the core–shell structure in which the sulfur particle is encased in carbon during the solidification of the composite (EP3813156). This solution allows the achievement of electrical conductivity performance results in the cathode that are partially similar to the use of the GSC, even when another form of carbon is used instead of graphene [38].

From a quantitative perspective, core–shell strategies enable lower GSC loadings per Wh, as evidenced by the lower bound values reported in Table S2, thereby reducing the amount of graphene-containing material required per unit of stored energy. Consequently, in this way it is possible to reduce the environmental impact resulting from the production of graphene (US20240145706).

An intermediate solution is to combine graphene with other forms of carbon, such as CB, in the GSC (EP3940823). By increasing the performance of the LSB, this solution is also used to reduce the LiTFSI content (US20240145706). This approach is reflected in Table S2 by intermediate GSC loadings and contributes to reduced LiTFSI areal loadings, as reported in the corresponding electrolyte data.

3.3.3. Introduction of Transition Metal Composites

A further solution to reduce the mass of graphene is transition metal doping in the GSC (EP3940823). The goal is always to raise the electrical conductivity of the cathode and reduce the graphene content [39]. This effect is quantitatively captured in Table S2 through lower GSC mass per Wh in patented designs employing composite cathode formulations, contributing to reduced production-stage impacts associated with graphene synthesis.

3.3.4. Introduction of Organic Ionic Receptors

The introduction of organic ionic receptors in the electrolyte allows us to reduce the LiTFSI content by effectively trapping polysulfides, maintaining high ionic conductivity, and stabilizing the electrolyte environment, reducing impacts and costs and increasing LSB performance [40,41]. This solution is implemented in the patented LSB sulfur (EP3951992 and EP4231433) and in the patented LSB GSC of EP3813156. Tables S1 and S2 quantitatively reflect this strategy through lower LiTFSI areal loadings (mg/cm2), which directly reduce the contribution of LiTFSI production to climate change and fossil depletion impacts.

3.3.5. Introduction of Ionic Liquid

The introduction of a small amount of an organic ionic liquid into the electrolyte enhances the ionic conductivity, improves the electrochemical stability and has a synergistic effect with sulfur electrode, thus allowing us to reduce the most impacting LiTFSI [42]. This solution was implemented in JP6481989. The associated reduction in LiTFSI content is explicitly reported in Table S1 through reduced LiTFSI areal loadings and electrolyte thickness values.

3.3.6. Introduction of Composite Binder

The use of a composite binder including styrene–butadiene rubber (implemented in CN113809332 and US20150311489) enhances the mechanical and electrochemical properties of the electrode, thus allowing for lower concentrations of LiTFSI [43]. This effect is quantitatively reflected in Table S1 by lower LiTFSI mass per unit of stored energy in the patented designs employing composite binders.

Overall, although individual eco-design strategies were not modeled as isolated LCA scenarios, their quantitative influence is directly embedded in the patent-derived inventory reported in Tables S1 and S2. These parameters form the basis of the LCI and therefore establish a direct quantitative link between patented eco-design solutions and the production-stage environmental impacts identified in the prospective LCA.

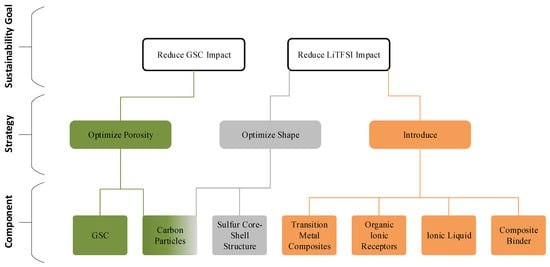

Figure 3 graphically summarizes the eco-design solutions identified in the analyzed patents to reduce the impacts of the GSC and LiTFSI.

Figure 3.

Overview of eco-design strategies derived from patent analysis. Each proposed solution targets key materials and process improvements aimed at reducing the environmental impact of LSB production. Green-colored elements indicate strategies based on porosity optimization, gray-colored elements indicate strategies based on shape or structural optimization, and orange-colored elements indicate strategies based on the introduction of new materials. Connections illustrate the logical progression from sustainability goals to strategies and finally to material- or component-level solutions.

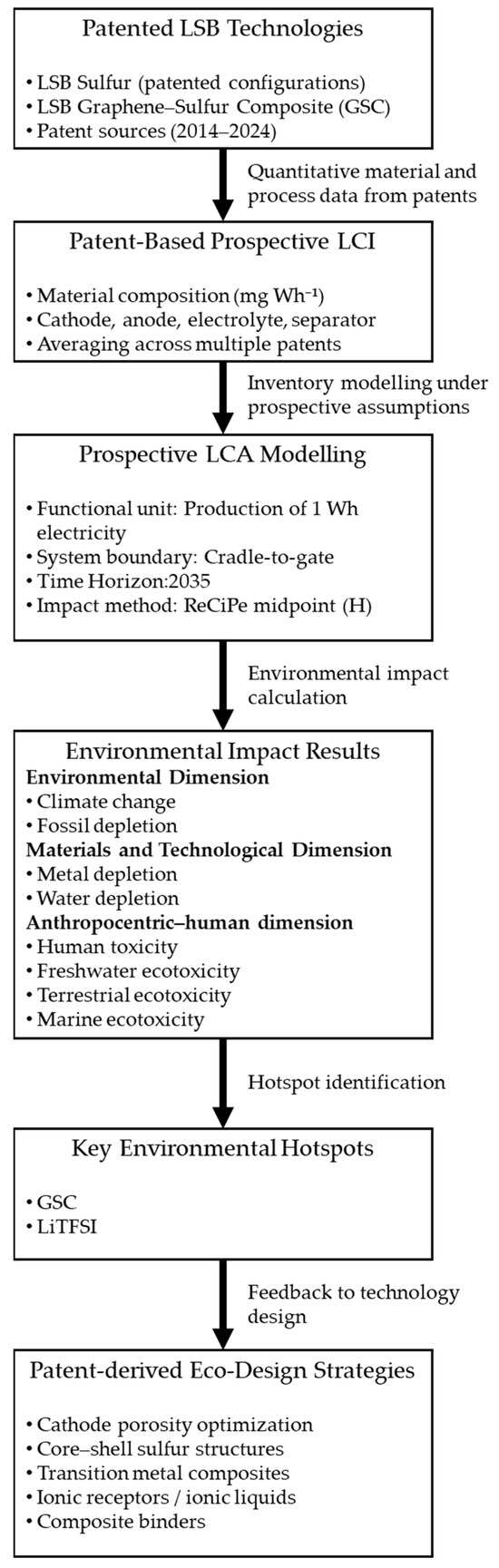

3.4. Integrated Prospective LCA Framework for Patented LSB Technologies

This subsection provides an integrated synthesis of the prospective LCA framework applied in this study, explicitly linking the technological analysis, inventory construction, impact assessment, and eco-design interpretation discussed in Section 3. While each analytical component was presented separately in Section 3, this subsection consolidates them into a coherent methodological structure.

Figure 4 graphically illustrates the coordination between patented LSB technologies, patent-based LCI modeling, environmental impact assessments, and the identification of eco-design strategies. The framework starts with patented LSB sulfur and LSB GSC configurations, from which quantitative material and process data are extracted and aggregated to build a prospective LCI representative of future industrial implementations.

Figure 4.

Integrated patent-based prospective LCA framework for LSB technologies, illustrating the coordination between patented LSB configurations, inventory modeling, impact assessment, hotspot identification, and eco-design feedback across environmental, materials and technological, and anthropocentric–human dimensions.

The patent-based LCI is then evaluated using a prospective LCA approach, adopting a functional unit of 1 Wh of produced electricity, a cradle-to-gate system boundary, and a future time horizon set to 2035. Environmental impacts are assessed using the ReCiPe midpoint (H) method, allowing the identification of impact hotspots across environmental, materials and technological, and anthropocentric–human dimensions.

Based on the impact assessment results, key environmental hotspots are identified, notably the graphene–sulfur composite and the lithium salt LiTFSI. These hotspots are subsequently linked to eco-design strategies derived directly from the same patent corpus, establishing a feedback loop between environmental assessment and technological innovation. This iterative structure enables the proactive identification of design solutions capable of reducing environmental impacts before large-scale commercialization.

The general specifications and preconditions of the proposed prospective LCA framework are summarized as follows:

- Functional unit: production of 1 Wh of electricity.

- System boundary: cradle-to-gate.

- Time horizon: 2035.

- Data source: quantitative material and process data extracted from granted patents (2014–2024).

- Impact assessment method: ReCiPe midpoint (H).

- Intended applicability: emerging battery technologies at low-to-medium technology readiness levels.

This structured framework enhances methodological transparency and supports the transferability of the proposed approach to other emerging technologies and industrial contexts.

It is important to note that no single environmental assessment method is designed to address all sustainability-related questions for battery technologies simultaneously. Existing approaches differ in scope, system boundaries, data requirements, and intended applicability depending on technology maturity and study objectives, as presented in Section 1. Conventional LCA methods are well-suited for mature battery technologies with stable industrial inventories, whereas emerging technologies such as LSBs require prospective approaches that prioritize design variability and forward-looking data sources. Accordingly, the present study adopts a set of explicit restrictions, including a cradle-to-gate system boundary, a production-stage focus, a functional unit of 1 Wh, and the use of patent-derived quantitative data. These restrictions are intentional and necessary to ensure methodological consistency, transparency, and comparability within a patent-based prospective LCA framework, rather than to provide a comprehensive assessment of all life cycle stages or battery chemistries, as discussed previously.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluates the environmental impacts of patented LSBs featuring sulfur (referred to as LSB sulfur) and a graphene–sulfur composite (LSB GSC) as cathode materials, using prospective LCA and identifies eco-design solutions derived from the same patents to mitigate these impacts.

The prospective LCA reveals that the patented LSB GSC exhibits lower climate change and fossil depletion impacts, primarily due to reduced LiTFSI usage, but higher metal depletion and water depletion impacts compared to the patented LSB sulfur. These results highlight the trade-offs involved in incorporating graphene into LSBs. Both patented LSB models demonstrate overall lower environmental impacts compared to those reported in the scientific literature. The patented LSB sulfur reduces climate change and fossil depletion impacts relative to its counterpart from the literature, primarily through reductions in DME, PVDF, and HDPE usage, which offset increases in LiTFSI and PP. Similarly, the patented LSB GSC achieves lower impacts compared to its literature-based counterpart, mainly by reducing the GSC load.

The identified eco-design solutions from patented LSBs were searched and collected from those related to graphene and LiTFSI, which are the main sources of impacts. These solutions include optimizing cathode porosity, employing core–shell structures, introducing transition metal composites, incorporating organic ionic receptors, using ionic liquids, and utilizing composite binders.

It is important to note that cycle life, degradation behavior, and end-of-life performance are not addressed within the cradle-to-gate scope of this study. Accordingly, the reported results should be interpreted as production-stage environmental trade-offs associated with material selection and design choices, rather than as indicators of overall life cycle sustainability or durability-related performance.

In conclusion, this study has shown how patent analysis can be instrumental in providing precise information derived from the latest developments of LSBs in the industry. For the prospective LCA, the patent analysis provided data to expand the inventory, which, in studies in the scientific literature, is typically very focused on only a few selected sources. As proof of the strategic nature of patents, their prospective LCA provided different impacts from studies in the scientific literature. In the field of eco-design, the analysis of the same patents used for the prospective LCA made it possible to determine which solutions reduce impacts. Overall, while LSBs hold significant promise for the future of energy storage and decarbonization, their environmental sustainability requires careful consideration and continuous improvement. Integrating up-to-date industrial data from patents into future LCA studies is essential to accurately predict and minimize the environmental impacts of LSBs towards commercialization.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18020711/s1. Table S1. Data of LSB Sulphur from patents; Table S2. Data of LSB GSC from patents; Table S3. Data of LSB Sulfur from papers [13]; Table S4. Data of LSB GSC from papers [16]; Table S5. Inventory of LSB Sulfur and LSB GSC from patents and papers [13,16,44,45]; Table S6. Impacts of the patented LSB Sulfur; Table S7. Impacts of LSB Sulfur from [13]; Table S8. Impacts of the patented LSB GSC; Table S9. Impacts of LSB GSC from [16]; Table S10. Ecoinvent v 3.8 cut-off, ReCiPe Midpoint (H); Table S11. Inventory of 1 kg of LiNO3 [16]; Table S12. Inventory of 1 kg LiTFSI production [16]; Table S13. Inventory of 1 kg of DOL production [16]; Table S14. Inventory of 1 kg of Lithium metal foil [15]; Table S15. Inventory of 1 kg of GSC [16]; Table S16. Inventory of 1 kg of GO [16]; Table S17. Inventory of 1 kg of Na2S2O3 [16]; Table S18. Inventory of 1 kg of PvP [16].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.; methodology, C.S.; software, C.S.; validation, C.S.; formal analysis, B.Ö. and C.S.; investigation, C.S.; resources, C.S.; data curation, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S. and B.Ö.; writing—review and editing, B.Ö. and C.S.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, C.S.; project administration, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Luca Alghisi for his support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jan, W.; Khan, A.D.; Iftikhar, F.J.; Ali, G. Recent Advancements and Challenges in Deploying Lithium Sulfur Batteries as Economical Energy Storage Devices. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pilla, S.; Rao, A.M.; Xu, B. Application of a New Type of Lithium-sulfur Battery and Reinforcement Learning in Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Energy Management. J. Energy Storage 2023, 59, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barke, A.; Cistjakov, W.; Steckermeier, D.; Thies, C.; Popien, J.-L.; Michalowski, P.; Pinheiro Melo, S.; Cerdas, F.; Herrmann, C.; Krewer, U.; et al. Green Batteries for Clean Skies: Sustainability Assessment of Lithium-Sulfur All-Solid-State Batteries for Electric Aircraft. J. Ind. Ecol. 2023, 27, 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, N.; Ahn, S.; Momma, T.; Osaka, T. Future Potential for Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. J. Power Sources 2023, 558, 232566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Prasad, E. Lithium Sulfur Battery Market Forecast-2030. Available online: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/lithium-sulfur-battery-market-A12076 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Tian, H.; Su, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, G. Advances in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries: From Academic Research to Commercial Viability. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2003666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, R.; Janssen, M.; Svanström, M.; Johansson, P.; Sandén, B.A. Energy Use and Climate Change Improvements of Li/S Batteries Based on Life Cycle Assessment. J. Power Sources 2018, 383, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Lin, Y.; Yang, L.; Lu, D.; Xiao, J.; Qi, Y.; Cai, M. Cathode Porosity Is a Missing Key Parameter to Optimize Lithium-Sulfur Battery Energy Density. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.; Akizu-Gardoki, O.; Lizundia, E. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of High Performance Lithium-Sulfur Battery Cathodes. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.-C.; Wang, P.-F.; Wang, J.-C.; Tian, S.-H.; Yi, T.-F. Key Challenges, Recent Advances and Future Perspectives of Rechargeable Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 124, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, R.; Svanström, M.; Sandén, B.A.; Thonemann, N.; Steubing, B.; Cucurachi, S. Terminology for Future-Oriented Life Cycle Assessment: Review and Recommendations. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Giesen, C.; Cucurachi, S.; Guinée, J.; Kramer, G.J.; Tukker, A. A Critical View on the Current Application of LCA for New Technologies and Recommendations for Improved Practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickerts, S.; Arvidsson, R.; Nordelöf, A.; Svanström, M.; Johansson, P. Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Sulfur Batteries for Stationary Energy Storage. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 9553–9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, L.A.-W.; Majeau-Bettez, G.; Singh, B.; Srivastava, A.K.; Valøen, L.O.; Strømman, A.H. Life Cycle Assessment of a Lithium-Ion Battery Vehicle Pack. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 18, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdas, F.; Titscher, P.; Bognar, N.; Schmuch, R.; Winter, M.; Kwade, A.; Herrmann, C. Exploring the Effect of Increased Energy Density on the Environmental Impacts of Traction Batteries: A Comparison of Energy Optimized Lithium-Ion and Lithium-Sulfur Batteries for Mobility Applications. Energies 2018, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Gao, X.; Yuan, C. Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium Sulfur Battery for Electric Vehicles. J. Power Sources 2017, 343, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, D.; Canals Casals, L.; Benveniste, G.; Corchero, C.; Trilla, L. The Effects of Lithium Sulfur Battery Ageing on Second-Life Possibilities and Environmental Life Cycle Assessment Studies. Energies 2019, 12, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, K.; Bernardinis, A.D.; Itani, K.; Bernardinis, A.D. Review on New-Generation Batteries Technologies: Trends and Future Directions. Energies 2023, 16, 7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreafico, C.; Landi, D.; Russo, D. A New Method of Patent Analysis to Support Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of Eco-Design Solutions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreafico, C. Prospective Life Cycle Assessment to Support Eco-Design of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2024, 17, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargos, P.H.; dos Santos, P.H.J.; dos Santos, I.R.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Caetano, R.E. Perspectives on Li-Ion Battery Categories for Electric Vehicle Applications: A Review of State of the Art. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 19258–19268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houache, M.S.E.; Yim, C.-H.; Karkar, Z.; Abu-Lebdeh, Y.; Houache, M.S.E.; Yim, C.-H.; Karkar, Z.; Abu-Lebdeh, Y. On the Current and Future Outlook of Battery Chemistries for Electric Vehicles—Mini Review. Batteries 2022, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 578, pp. 235–248.

- I. ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 578, pp. 235–248.

- Kamisan, A.I.; Tunku Kudin, T.I.; Kamisan, A.S.; Che Omar, A.F.; Mohamad Taib, M.F.; Hassan, O.H.; Ali, A.M.M.; Yahya, M.Z.A. Recent Advances on Graphene-Based Materials as Cathode Materials in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 8630–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golembiewski, B.; vom Stein, N.; Sick, N.; Wiemhöfer, H.-D. Identifying Trends in Battery Technologies with Regard to Electric Mobility: Evidence from Patenting Activities along and across the Battery Value Chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, M.J.; Heijungs, R.; Huijbregts, M.; De Schryver, A.; Struijs, J.V.Z.R.; Van Zelm, R. A Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method Which Comprises Harmonised Category Indicators at the Midpoint and the Endpoint Level; Report I: Characterisation; 6 January 2009. 2008; 133. Available online: http://www.lcia-recipe.net (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Adrianto, L.R.; van der Hulst, M.K.; Tokaya, J.P.; Arvidsson, R.; Blanco, C.F.; Caldeira, C.; Guillén-Gonsálbez, G.; Sala, S.; Steubing, B.; Buyle, M.; et al. How Can LCA Include Prospective Elements to Assess Emerging Technologies and System Transitions? The 76th LCA Discussion Forum on Life Cycle Assessment, 19 November 2020. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1541–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titirici, M.-M. Sustainable Batteries—Quo Vadis? Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, S.P.; Weil, M.; Baumann, M.; Montenegro, C.T. Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of a Model Magnesium Battery. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2000964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Xing, F.; Gao, Q. Graphene-Based Nanomaterials as the Cathode for Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Molecules 2021, 26, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrabide, A.; Rey, I.; Lizundia, E. Environmental Impact Assessment of Solid Polymer Electrolytes for Solid-State Lithium Batteries. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2022, 3, 2200079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Jin, H.-J. Polymeric Binder Design for Sustainable Lithium-Ion Battery Chemistry. Polymers 2024, 16, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresser, D.; Buchholz, D.; Moretti, A.; Varzi, A.; Passerini, S. Alternative Binders for Sustainable Electrochemical Energy Storage—The Transition to Aqueous Electrode Processing and Bio-Derived Polymers. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 3096–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moo, J.G.S.; Omar, A.; Jaumann, T.; Oswald, S.; Balach, J.; Maletti, S.; Giebeler, L. One-Pot Synthesis of Graphene-Sulfur Composites for Li-S Batteries: Influence of Sulfur Precursors. C 2018, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, W.; Gupta, V.; Gao, H.; Tran, D.; Sarwar, S.; Chen, Z. Current Challenges in Efficient Lithium-Ion Batteries’ Recycling: A Perspective. Glob. Chall. 2022, 6, 2200099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, P.; Shen, C.; Zheng, J.P. Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of Precipitation and Solubility Effects in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 284, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, Q.; Shi, L.; Gai, L.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, F. The Influence of Conductive Additives on the Performance of a SiO/C Composite Anode in Lithium-Ion Batteries. New Carbon Mater. 2017, 32, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, Q.; Chu, W.; Zhao, Y. Transition Metals Doped Borophene-Graphene Heterostructure for Robust Polysulfide Anchoring: A First Principle Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 534, 147575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, D.-Y.; Chen, Q.; Fu, Y. Advances of Organosulfur Materials for Rechargeable Metal Batteries. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Curtiss, L.A.; Zavadil, K.R.; Gewirth, A.A.; Shao, Y.; Gallagher, K.G. Sparingly Solvating Electrolytes for High Energy Density Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koralalage, M.K.; Shreyas, V.; Arnold, W.R.; Akter, S.; Thapa, A.; Narayanan, B.; Wang, H.; Sumanasekera, G.U.; Jasinski, J.B. Functionalization of Cathode–Electrolyte Interface with Ionic Liquids for High-Performance Quasi-Solid-State Lithium–Sulfur Batteries: A Low-Sulfur Loading Study. Batteries 2024, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Huang, J.-Q.; Peng, H.-J.; Titirici, M.-M.; Xiang, R.; Chen, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q. A Review of Functional Binders in Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1802107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Yu, Y.; Huang, K.; Hu, Y. Lithium-air, lithium-sulfur, and sodium-ion, which secondary battery category is more environmentally friendly and promising based on footprint family indicators? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, J.; Ding, F.; Chen, X.; Nasybulin, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.G. Lithium metal anodes for rechargeable batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 513–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.