Abstract

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) are a promising technology for simultaneously treating wastewater and recovering energy, yet scaling them from lab prototypes to practical systems poses persistent challenges. This review addresses the scale-up gap by systematically examining recent pilot-scale MFC studies from multiple perspectives, including reactor design configurations, materials innovations, treatment performance, energy recovery, and environmental impact. The findings show that pilot MFCs reliably achieve significant chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal (often 50–90%), but power densities remain modest (typically 0.1–10 W m−3)—far below levels needed for major energy generation. Key engineering advances have improved performance; modular stacking maintains higher power output, low-cost electrodes and membranes reduce costs (with some efficiency trade-offs), and power-management strategies mitigate issues like cell reversal. Life cycle assessments indicate that while MFC systems can outperform conventional treatment in specific scenarios, overall sustainability gains depend on boosting energy yields and optimizing materials. The findings highlight common trade-offs and emerging strategies. By consolidating recent insights, a roadmap of design principles and research directions to advance MFC technology toward sustainable, energy-positive wastewater treatment was outlined.

1. Introduction

Global demand for clean water and sustainable energy has intensified interest in technologies that can treat wastewater while recovering useful energy. Conventional wastewater treatment technologies are highly energy-intensive and account for about 1–2% of the electricity usage in industrialized countries [1,2]. Aeration can consume 25–60% of the energy consumed in treatment plants because of the large volume of air required to oxygenate municipal wastewater [3], which contributes significantly to operational costs and greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, wastewater contains rich chemical energy in the form of organic matter that typically remains unused in conventional processes [2]. These twin challenges of high energy demand and lost energy potential have prompted the search for more sustainable wastewater treatment solutions.

Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) have emerged as a promising technology that addresses both issues by directly converting the chemical energy in wastewater into electricity through the metabolism of electrogenic microorganisms [4,5]. An MFC typically comprises an anode and a cathode connected by an external circuit, configured either as a two-chamber system separated by a membrane/separator or as a single-chamber air cathode design. At the anode, electroactive microorganisms oxidize organic matter and transfer electrons to the anode; the electrons flow through the external circuit to the cathode to generate current, while charge balance is maintained by ion transport through the electrolyte and/or membrane. At the cathode, a terminal electron acceptor—most commonly oxygen—is reduced, completing the circuit, with overall performance governed by activation losses, ohmic resistance, and mass-transfer limitations [6]. This bioelectrochemical approach enables concurrent wastewater remediation and energy recovery, distinguishing MFCs from conventional treatment and from other renewable energy technologies [7]. Notably, MFC operation does not require energy-intensive aeration of water, thus potentially cutting energy usage, and it produces far less residual sludge than aerobic processes [8]. MFCs also align with emerging goals of resource recovery from waste, having been explored not only for power generation but also for nutrient removal and recovery [9], biosensing applications [10], and even the degradation of recalcitrant pollutants that traditional methods struggle to eliminate [11,12]. Over the past two decades, intensive research has improved MFC performance at the laboratory scale—increasing power densities from the microwatt to watt range and developing diverse reactor configurations [13,14]. These advances show that treating wastewater while recovering electricity is feasible at small scales.

Transforming MFC technology from the lab to practical applications, however, requires scaling up reactor sizes and operating with real wastewater under pilot conditions. Pilot-scale MFC systems (typically tens to hundreds of liters in volume) are a critical stepping stone toward commercialization, providing insight into the challenges of full-scale operation [15,16,17]. Early efforts to build larger MFCs revealed significant hurdles. For example, initial trials that simply stacked dozens of small MFC units achieved only marginal power outputs and proved excessively expensive due to the use of costly membranes and noble metal catalysts [18]. To address the stated issue, research has been directed to investigate designs and materials better suited for MFC scaling up. Strategies such as employing low-cost separators (e.g., replacing nafion with inexpensive ceramics or membranes formed by biofilms) and using catalyst-free electrodes or biocathodes (microbial catalysts in place of platinum) have been pursued to drive down costs [19,20,21]. Likewise, modular reactor configurations are favored over enlarging one cell. The modular approach to scale-up has been widely adopted. Significant examples include a system of 12 MFC units (a total volume of around 110 L) treating swine farm wastewater for over 200 days [22], a stacked array of MFC subunits containing a 720 L integrated system for municipal sewage for 255 days [18], and a 1000 L stack MFC composed of 64 units with more than three years of operation [23].

The recent pilot MFC projects demonstrate that larger MFCs can achieve stable wastewater treatment with measurable energy recovery, but they also reveal systematic performance issues at a real scale. In many cases, encouraging levels of organic removal (often 50–80% COD removal) have been reported alongside only small electrical outputs, typically in the milliwatt range [22,24]. Pilot experiments in niche applications—for example, MFC-based sanitation systems that treat human urine while powering small off-grid devices [25]—further confirm the feasibility of coupling treatment and energy generation. However, the gap between proof-of-concept demonstrations and robust, energy-positive large-scale operation remains substantial.

One of the major challenges is the scalability of electrochemical performance. As reactor size increases, power density and energy recovery generally decrease due to higher internal resistance, longer ion transport pathways, and more pronounced mass transfer limitations [25,26]. Larger reactors are more prone to concentration gradients, pH shifts, and uneven substrate distribution, especially when fed with real wastewater of low conductivity and variable composition. At the same time, many early pilot systems relied on materials that are not suited for long-term, large-scale operation, such as ion exchange membranes and precious metal catalysts, which increase capital and maintenance costs and are vulnerable to fouling [26,27]. Fouling of membranes and electrodes by organic matter or mineral precipitates is frequently reported as a cause of performance decline over time [26,28], emphasizing the need for robust, low-cost materials tailored to wastewater environments. Alternative approaches, including ceramic or cloth separators, dynamic biofilm-based membranes, and biocathodes, have been explored to reduce cost and improve sustainability [29,30,31]. Yet, their performance at large-scale and over long durations remains incompletely understood, and each option introduces trade-offs between electrical output, durability, and treatment efficiency.

Another critical bottleneck in scaling up MFCs is the electrical integration and configuration of multiple cells. Because a single MFC typically generates only a few hundred millivolts, practical systems commonly employ series and parallel connections of many units. The stacked approach can increase overall voltage and current but introduces new failure modes, most notably voltage reversal, in which individual cells invert polarity and consume power from the rest of the stack [23,32]. Voltage reversals are often triggered by uneven substrate distribution, heterogeneous microbial activity, or local depletion in certain modules [2]. Various mitigation strategies, including electronic control circuits, bypass configurations, and maximum power point tracking, have been proposed [23]. While these can improve stack stability, they also add complexity and cost, and a universally reliable solution has not yet emerged. In addition, large modular arrays pose practical challenges in monitoring and maintenance. Cells can foul or degrade at different rates, making it difficult to detect and correct underperforming units without extensive instrumentation [23]. Consequently, reactor design and electrical configuration are tightly coupled in determining the performance and robustness of upscaled MFC systems.

Beyond engineering limitations, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the biological and electrochemical behavior of large-scale MFCs. Many pilot studies prioritize demonstrating overall COD removal and power generation, while providing limited insight into microbial community dynamics, spatial distribution of electrogenic biofilms, or local electrode kinetics within large reactors. Only a few investigations have examined how microbial communities vary across extended electrodes or between modules and how this heterogeneity affects performance and stability [33]. The influence of inoculum source, microbial diversity, and biofilm structure on long-term operation at large-scale also remains unresolved, with sometimes conflicting observations across different studies.

Given this background, a focused synthesis of recent large-scale MFC research is needed to clarify how these interconnected issues are being addressed and where critical gaps remain. The progress from milliliter-scale reactors to hundred- and thousand-liter systems provides a rich body of experience, but the results are scattered across studies that differ in design, materials, and operating conditions. Moreover, most existing reviews either emphasize lab-scale systems or treat reactor design, materials, and performance metrics separately, making it difficult to extract scale-up principles for real wastewater applications. This review is a focused narrative synthesis of peer-reviewed, pilot-scale MFC studies treating real wastewater streams. Studies were included when they reported pilot-scale operation across the themes reviewed. Hence, the present review concentrates on MFCs that have been upscaled beyond the laboratory scale and systematically examines their performance from five complementary perspectives: (i) reactor design and configuration optimization, including modular architectures and stacking strategies; (ii) electrode and membrane material innovations aimed at reducing cost and fouling while maintaining electrochemical performance; (iii) COD removal and wastewater treatment efficiency under realistic operating conditions; (iv) power density and energy recovery, including approaches for electrical integration and system level optimization; and (v) life cycle assessment (LCA) studies evaluating the environmental challenges and benefits of scaled MFCs. This review aims to identify consistent trends, highlight trade-offs, and outline design and research directions to advance large-scale MFCs toward practical, sustainable wastewater treatment with concurrent energy recovery by organizing and critically analyzing the state of the art in these five areas.

2. Reactor Design and Configuration Optimization

Scaling MFCs from bench-top reactors to pilot units demands designs that preserve electrochemical performance at larger scales. To tackle rising internal resistance, non-uniform flow, and cell imbalances that accompany scale, researchers have pursued two broad strategies: numbering up modular cells and refining single-reactor geometries. A fundamental approach has been to subdivide the total volume into multiple modules rather than building a single large cell. In this regard, Zhang and Liu [26] compared a unit stacked array of small MFCs (parallel/series connections) with a single enlarged reactor of equal volume and found that stacking better maintained power output and treatment efficiency. At the pilot scale, Liang et al. [15] built a 1000 L system of fifty modules packed with granular activated carbon electrodes for municipal wastewater, while Blatter et al. [2] implemented a 1000 L single chamber reactor containing sixty-four subunits sharing a common electrolyte to limit ohmic losses.

Several novel configurations have also been explored. Feng et al. [16] developed a stackable horizontal plug-flow MFC (250 L per module) to impose plug-flow hydrodynamics. Chen et al. [34] introduced a stacked anaerobic fluidized bed MFC comprising forty-five miniature air cathode units within a shared chamber to treat benzene-laden industrial wastewater. Integration with conventional treatment trains has also been assessed. Liu et al. [29] retrofitted a 1 m3 MFC into an anaerobic–anoxic–oxic system (MFC-AA/O), indicating compatibility with existing process flows. Design choices also extended to electrical configuration. Walter et al. [32] and Das et al. [18] assembled stacks (fifteen to eighteen cells and six cells, respectively) to directly power small devices, and Maye et al. [23] implemented an electronic control system that actively blocked voltage reversal in a sixty-four-cell stack to protect weaker cells.

Results across these studies reveal consistent patterns. Modular stacking generally outperforms simple size enlargement. As reported by Zhang and Liu [26], the stacked system achieved near complete inorganic nitrogen removal (about 99% nitrate and 92% ammonium) and a maximum power density of about 3.2 W m−3, whereas the single enlarged reactor of equal volume underperformed. Large modular systems also sustained stable operation. Liang et al. [15] operated their 1000 L, 50-module reactor continuously for one year, reaching 70–90% COD removal with effluent COD below 50 mg L−1 and peak power densities around 125 W m−3 (7.58 W m−2) under optimized conditions; on real wastewater, typical outputs were 7–60 W m−3. Blatter et al. [2] reported the stable, eighteen-month operation of a shared electrolyte 1000 L stack, capturing 5.8–12.1% of wastewater COD energy as electricity—among the highest reported energy conversion efficiencies. Novel stacked configurations performed well under industrial loads. Chen et al. [34] achieved 89% COD removal for benzene-contaminated waste and observed near linear scaling of power with unit number (a forty-five-unit stack produced around 43 times the power of a single unit), indicating minimal loss during numbering up. Practical bottlenecks were addressed through engineering controls. Dong et al. [30] used a parallel flow distribution manifold in a 1.5 m3 biocathode MFC to equalize substrate delivery and prevent downstream anode starvation, and Maye et al. [23] showed that active circuitry to prevent voltage reversal can prevent cell damage and extend the operating life of a 1000 L series/parallel stack.

Critical evaluation of the studied pilot plants points to a clear preference for modular layouts to control-scale-related performance drawbacks. While subdividing volume reduces average ion/electron transport distances and helps sustain power density, multicell architecture introduces challenges in electrical and hydraulic integration. Voltage reversal shows this tension. Blatter et al. [2] observed occasional, self-correcting reversals in a shared electrolyte stack, whereas Maye et al. [23] reported severe reversals in strictly serial connections that required active intervention. Connecting modules through a shared electrolyte or in parallel reduces differences between units but lowers the voltage delivered by each cell. Conversely, connecting modules in series gives a higher total voltage but increases the risk of voltage reversal when loads are uneven and, therefore, demands closer monitoring. Hydrodynamics is also another matter that has become increasingly significant with scaling up. Dong et al. [30] demonstrated that appropriate manifolds and alternating flow directions promote uniform nutrient access and mitigate downstream underperformance. Moreover, environmental factors, typically controlled in the laboratory, also matter in real field conditions. Liu et al. [29] reported that wintertime performance declines with lower water temperatures. Maintenance demand is another factor that should be considered more seriously in large-scale applications. In a large-scale study by Liang et al. [15], periodic membrane replacement and fouling control in their 1000 L plant were reported.

Another important point is that few systems exceed a few cubic meters, and cross-study comparison is limited by non-standardized reactor designs and the absence of common operating and reporting protocols. Differences in reactor architecture, electrode and membrane materials, electrical configuration (series/parallel/shared electrolytes), influent composition, loading regime, and hydrodynamics mean that results are generated and reported on bases that are not directly comparable, complicating extrapolation of both performances. Nevertheless, the scale-up outlook reported in the literature is encouraging for the realization of large-scale MFCs. Several pilots have operated for months to years [2,15,22], indicating that well-engineered configurations of MFCs can be robust and practical. Modular designs offer practical benefits—serviceability of individual units without full shutdown, incremental capacity expansion by numbering up, and site-specific modifications—but these gains are offset by the additional balance of plant requirements (flow distribution hardware and voltage management/anti-reversal electronics) that increase complexity and energy demand. Progress toward real-scale application of MFCs will largely depend on simplifying stack hydraulics and electrical management, for example, via fundamentally balanced stacks and passive flow distribution patterns that reduce maintenance. The outcomes from pilots suggest that shared electrolyte layouts, fluidized electrode beds, and automated anti-reversal controls can be combined in next-generation reactors. Advances in reactor design are moving MFCs toward practical application by addressing scale-dependent limitations and providing a basis for engineered modules in wastewater treatment facilities. As shown in Table 1, recent pilot-scale MFC studies show a wide range of reactor configurations and volumes. Table 1 summarizes the key design parameters of these systems—including reactor size, number of cells, feed substrate, electrode materials, and operating mode—highlighting the diversity of approaches used to scale up MFCs.

Table 1.

Summary of recent pilot-scale MFC configurations used for wastewater treatment.

3. Electrode and Membrane Materials Innovation

Electrode and membrane materials strongly influence both the performance and the cost of MFCs, and the high expense of conventional components such as platinum cathodes and nafion proton-exchange membranes is a barrier to scale-up [35,36]. Pilot studies have, therefore, pursued new materials and configurations—including inexpensive membranes, alternative catalysts, and high-surface-area electrodes—to improve durability, reduce cost, and enhance electrochemical performance. A key objective has been to replace costly or short-life components with sustainable alternatives. Suransh et al. [27] built a pilot MFC using low-cost earthenware membranes instead of ion-exchange membranes, aiming for an affordable decentralized treatment unit. Walter et al. [32] compared a membrane-less “self-stratifying” MFC, where the anolyte and catholyte form layers in one vessel, with a conventional ceramic membrane MFC to determine whether membranes are necessary. Zhang and Liu [26] integrated a filtration membrane cathode in an up-flow MFC so that the membrane not only separated chambers but also functioned as the cathode and effluent filter, thereby maintaining water quality and reducing fouling. Many pilots exploited high-surface-area electrodes. Liang et al. [15] filled their 1000 L modules with 375 kg of granular activated carbon (GAC), providing a three-dimensional anode that also adsorbed organics. Hiegemann et al. [28] fabricated 85 × 85 cm multi-panel air cathodes using stainless steel mesh coated with activated carbon for a 255 L reactor. Non-precious catalysts and biocathodes also featured prominently. Das et al. [18] employed a low-cost anode and cathode and membranes in a 720 L field MFC (Co0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 and Sn5Cu84 as the cathode catalysts, goethite as the anodic catalyst, and an inexpensive clayware ceramic membrane), replacing expensive materials with inexpensive carbon-based and metal oxide catalysts to reduce cost. Dong et al. [30] used microbial oxygen-reducing biofilms on carbon brushes as biocathodes in a 1.5 m3 system and partially coated these brushes with hydrophobic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) to entrap oxygen and enhance diffusion. Sugioka et al. [24] selected an anion exchange membrane (AEM) for a 226 L air cathode MFC, hypothesizing that AEMs could reduce pH imbalances and ammonia crossover. In other cases, the electrode architecture itself was treated as a material innovation. Leininger et al. [33] compared large three-dimensional electrodes with flat plates in an 800 L MFC to see how structure affects microbial colonization and performance.

A careful analysis shows that the performance outcomes of the applied material innovations were mixed but generally positive. Earthen separators used in the pilot MFC study by Suransh et al. [27] retained high treatment performance, removing about 90% of COD and substantial nitrogen (75% ammonium and 85% nitrate) in domestic wastewater. However, the power output remained low at around 23.5 mW m−3, suggesting that earthen membranes may have higher internal resistance. The membrane-less MFC used in the study by Walter et al. [25] achieved a peak power density of 69.7 W m−3 at a short 3 h hydraulic retention time (HRT), which was more than double the power reported by a ceramic MFC of 32.2 W m−3. That result aligns with the point that removing the membrane reduces internal resistance and increases current. Interestingly, the energy recovery per unit of COD for the membrane-less design (0.34 kWh kg−1 COD) was much lower than that of the ceramic MFC (2.09 kWh kg−1 COD at 24 h HRT). This implies that while membrane-less reactors deliver higher instantaneous power, membrane-equipped systems convert substrate energy more efficiently over longer residence times.

The filtration cathode MFC assessed by Zhang and Liu [26] maintained excellent effluent quality (>99% COD removal). Moreover, optimizing the influent carbon–nitrogen ratio by adding urea reduced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) buildup on the cathode by about 52% and boosted COD removal capacity to 4.23 kg COD m−3 day−1. High-surface-area electrodes like GAC deliver dual benefits. Liang et al. [15] achieved high COD removal (70–90%) and, under ideal conditions, a volumetric power density of 125 W m−3. However, under continuous real wastewater, their power output dropped to several tens of W m−3, and periodic regeneration or replacement of the GAC was necessary as adsorption sites became saturated or biofouled. Replacing precious metal catalysts with cheaper alternatives also showed promising results. Das et al. [18] maintained continuous operation for roughly eight months with COD removal of 60–87% in their 720 L MFC and produced enough power to light an LED, despite a maximum power density of only 0.36 W m−3. Dong et al. [30] found that a partially PTFE-coated carbon brush cathode improved power output by 15% under oxygen-limited conditions, as the hydrophobic coating retained oxygen and facilitated a thicker aerobic biofilm. In a study by Sugioka et al. [24], using an AEM allowed for 90% COD removal over a year with moderate power (0.072–0.51 W m−3). Although the internal resistance associated with AEM increased due to fouling after about five months, soaking the membrane in NaCl solution restored its low resistance, suggesting that fouling was reversible. Their coulombic efficiency remained around 15%, and the ability of the AEM to allow anions to move likely helped minimize pH gradients. Another important matter in MFC performance is electrode architecture. Leininger et al. [33] reported that a three-dimensional large brush electrode oriented to promote flow through it developed a highly electrogenic biofilm. However, their study showed that surface-oriented brush biocathodes were not effective for power generation in a large wastewater MFC system, possibly because of significant internal current within the cathodes, indicating that simply enlarging an electrode does not guarantee high performance.

Studies on large-scale MFCs highlight several dependable, cross-cutting material trends. The foremost trade-offs are between cost and performance and between simplicity and durability. Low-cost ceramics and stainless steel reduce capital costs but often introduce higher internal resistance or lower conductivity [27]. Membrane-less designs eliminate membrane cost and fouling but require careful operation, as Walter et al. [25] showed that a short HRT was necessary to maintain stratification and high power, and energy recovery per COD was lower [37]. Fouling and maintenance are major challenges for high-surface-area electrodes and coatings. Hiegemann et al. [28] observed inorganic scaling on large activated carbon cathodes, which cut power by more than 90% and could only be partially restored by aggressive cleaning. Liang et al. [15] emphasized the need for periodic GAC regeneration. The role of membranes remains debated. Some pilots with membranes achieved excellent pollutant and nutrient removal (e.g., Zhang and Liu [26]), yet membranes are often expensive and prone to fouling. Moreover, long-term durability data are still scarce. Although few pilot studies extend beyond one year, Babanova et al. [22] reported stable performance over two years using carbon-based electrodes; however, the lifespans of ceramic membranes and coated electrodes remain uncertain. Supplying large quantities of materials (e.g., 375 kg of GAC or large stainless-steel panels) and managing their end of life may be challenging at full scale. The results also indicate that bigger electrodes do not proportionally increase performance if biofilms cannot penetrate them; structured or flow-through designs, as demonstrated by Leininger et al. [33], may be necessary. Moreover, Zhang and Liu [26] demonstrated that nutrient balance influences membrane cathode fouling, and Dong et al. [30] showed that hydrophobic coatings can supplement material performance by creating microenvironments for oxygen, which shows the interaction of operational parameters with materials.

Looking forward, material innovation is gradually reducing costs and increasing practicality. The successful use of ceramics, carbon, and stainless steel shows that MFCs can be built without precious metals or proprietary membranes, making the technology more accessible. However, full-scale systems must incorporate fouling control mechanisms, whether through design (fluidized particles scouring electrodes or accessible membranes for cleaning) or routine maintenance (chemical cleaning and back-flushing). Simple interventions such as PTFE coatings [30] or salt soaking [24] can sustain performance and should be integrated into operating protocols. Maximizing surface area through porous electrodes will remain crucial, but these structures must be engineered for long-term stability, potentially through anti-clogging measures or modular replacement of used media. The shift toward membrane-less or alternative membrane systems could significantly lower costs if comparable treatment goals are achieved. Overall, the future direction points toward durable, scalable materials replacing laboratory-grade components, a necessary step for real-world deployment. Future work should evaluate large-scale implementation of nano-structured carbons, conductive polymers, and biologically enhanced electrodes to further improve the balance between cost and performance and to bring MFC technology closer to commercial reality.

4. COD Removal and Wastewater Treatment Efficiency

Efficient removal of pollutants, expressed as chemical oxygen demand (COD), is a primary requirement for any wastewater treatment technology. At the pilot scale, demonstrating high COD removal and meeting effluent standards is essential to validate the viability of MFCs beyond the laboratory. Pilot studies have, therefore, assessed treatment performance alongside electricity generation, examining how well MFCs reduce COD, nutrients, and other pollutants under realistic conditions. The types of wastewaters treated in pilot MFC studies range from low-strength municipal sewage to high-strength industrial or animal waste. Babanova et al. [22] evaluated swine wastewater rich in COD and solids to determine whether an MFC could handle concentrated waste with a short hydraulic retention time. Their pilot MFC (110 L) was continuously operated for more than 200 days with an HRT of 4 h. Very stable electrochemical and waste treatment performance was observed, with up to 65% of COD removed and a maximum treatment rate of 5 kg COD m−3 day−1. Robust microbial enrichment was performed and adapted to metabolize and transform a diversity of compounds present. The reported energy recovery of 0.11 kWh/kg COD was not only competitive with conventional cogeneration processes but was also sufficient to sustain the operational energy requirements of the system. Chen et al. [34] targeted a refractory benzene-laden industrial effluent using a specialized stacked fluidized-bed MFC with excellent COD removal of about 89%. Other studies focused on typical municipal wastewater (200–500 mg L−1 COD), trying to meet discharge standards; He et al. [31] (COD removal of 91%, effluent COD of 25 mg L−1, and HRT of 5 h), Sugioka et al. [24] (COD removal of 58%, effluent COD of 45 mg L−1, and HRT of 42 h), Liang et al. [15] (COD removal of 80%, effluent COD below 50 mg L−1, and HRT of 0.5 h), and Suransh et al. [27] (COD removal of 94%, effluent COD of below 50 mg L−1 and HRT of 48 h) are among the pilot MFC studies who fall into this category. Some research teams assessed and tested operational parameters such as HRT and flow regimes; for instance, Das et al. [18] studied different HRTs (18 h vs. 36 h) in a 720 L field MFC and found that longer retention improved removal (78% vs. 87%). Feng et al. [16] recirculated flow in a horizontal plug-flow MFC to increase contact and enhance removal. Mohamed et al. [3] combined the use of polarized electrodes with MFCs to develop a switchable dual-mode bioelectrochemical wastewater treatment system. The system was switched to either a self-powered MFC mode or a potentiostatically controlled mode, which both showed enhanced COD removal vs. the control (42% and 38% vs. 29%). Enhanced COD removal was also explored through integration with existing processes. Liu et al. [29] coupled an MFC with an aerobic–anoxic–oxic process, using the MFC for initial COD removal and leaving polishing to the conventional process (with effluent COD of 25–35 mg L−1). Many pilot MFCs also monitored nitrogen removal, since full-scale treatment must meet nutrient limits. The dual cathode designed by Zhang and Liu [26] explicitly created aerobic and anoxic zones to enable nitrification and denitrification concurrently with COD removal.

In general, pilot MFCs have achieved substantial COD removal across wastewater types, with effluents often meeting first-grade A limits (≤50 mg L−1) when design and operation are well matched to the influent. In a 1.5 m3 municipal pilot, He et al. [31] reported 91% removal at an HRT of 5 h, yielding 25 mg L−1 effluent. By contrast, Sugioka et al. [24] obtained 58% removal at a much longer 42 h HRT (effluent 45 mg L−1), highlighting that configuration and influent characteristics are also among the most important parameters. Liang et al. [15] maintained about 80% removal at only 0.5 h HRT while keeping effluents below 50 mg L−1 in a 1000 L modular system, suggesting advantages from intensified hydraulics and the reactor architecture. At the high end, Suransh et al. [27] achieved 94% removal with effluents <50 mg L−1 at a 48 h HRT. Overall, these pilot studies show that >80% COD removal and ≤50 mg L−1 effluents are attainable across diverse designs. Higher-strength waste or shorter treatment times yield lower removal. Babanova et al. [22] reported about 65% removal when treating swine waste at a 4 h HRT, but the volumetric removal rate was high at 5 kg COD m−3 day−1, indicating fast treatment. Das et al. [18] observed HRT-dependent performance; at an 18 h HRT, COD removal was 78% (an effluent COD of about 303 mg L−1), increasing to about 87% at a 36 h HRT; even so, the effluent COD remained above typical discharge standards, suggesting that a longer retention or secondary treatment is needed. Kinetic analyses support the importance of residence time. Walter et al. [25] reported that removal efficiency increased with HRT (3% at a 24 h HRT vs. 25% at a 65 h HRT).

Other nutrient removal performances were different in pilot MFC research. Zhang and Liu [26] achieved nearly complete nitrogen removal (99% nitrate and 92% ammonia) alongside >99% COD removal by employing a nitrifying membrane cathode by adjusting influent C/N. Suransh et al. [27] also achieved substantial nutrient removal (about 75% ammonia and 84% nitrate), which was reported due to concurrent nitrification (via limited oxygen intrusion), NH4+ transport across the membrane, anaerobic ammonium oxidation, and heterotrophic denitrification, consistent with a design enabling simultaneous nitrification–denitrification. By contrast, in the 255 L pilot MFC by Hiegemann et al. [28], total nitrogen removal was markedly lower. The authors linked it to thin biofilm development and extensive Ca/Mg-carbonate scaling on air cathodes that impeded ORR and limited nitrifier establishment—highlighting the strong configuration and operation dependence of nutrient outcomes.

Seasonal effects were clear in the studies, with colder months slowing microbial and electrochemical processes and reducing COD and nutrient removal and decreasing power, which highlights the need for temperature-aware operation (e.g., adjusted HRT, insulation/heating, and load management). Liu et al. [29] reported stable effluent quality during warm periods but a drop in COD and nutrient removal in winter, likely due to reduced microbial activity.

Pilot-scale systems also showed resilience under variable influent and operating conditions. Babanova et al. [22] found that despite processing highly variable swine waste, the microbial community structure in effluent remained consistent across all twelve units, suggesting stability at a 4-h HRT. They reported a normalized energy recovery of 0.11 kWh kg−1 COD removed—on par with or higher than the electrical energy typically obtained from anaerobic digestion—while Sugioka et al. [24] estimated that using an MFC as pretreatment could reduce downstream aeration energy requirements by about 70%. The high COD removal achieved in pilot MFCs is encouraging, but several concerns may emerge. Many systems achieving >85% removals were treating low-strength waste; conventional activated sludge processes also achieve >90% removal with shorter HRTs (6–8 h), whereas MFCs often require longer residence. Das et al. [18] needed 36 h to approach 87% removal, highlighting slower kinetics associated with electroactive bacteria. Strategies such as plug-flow designs and recirculation [16] attempt to increase effective contact time without enlarging reactors. Multi-stage or multi-module systems can incrementally improve COD removal. For example, running units in series or parallel, as Chen et al. [34] did, improved both removal rate and total power. However, high-strength waste still remains challenging. Swine waste [22] and raw sewage [18] cannot meet effluent standards without longer HRTs or additional treatment.

Completeness of treatment is another concern. Many pilot MFCs did not remove nitrogen effectively unless designed to do so. The near-total nitrogen removal reported by Zhang and Liu [26] required dual cathodes and careful engineering. Simpler designs left significant amounts of ammonia or nitrate. Environmental variability (temperature, toxic spikes, and salinity) affects performance, and few studies evaluated responses to shock loads or toxic compounds. Hiegemann et al. [28] highlighted that high salinity caused salt buildup on electrodes, drastically reducing COD removal—MFCs may, therefore, need pretreatment or adaptive controls for such influents.

Across pilot studies, coulombic efficiency (CE) was limited. Sugioka et al. [24] reported CE values of 20–41% (29% on average, with no clear HRT trend) and an energy generation efficiency that declined with increasing HRT (maximum 0.11 kWh kg−1 COD at 9 h). Liang et al. [15] observed CE falling from 75% to 41% as the cathode chamber HRT increased from 15 to 60 min due to greater cathodic heterotrophic oxidation. Both studies indicate that a substantial share of COD is consumed via non-electrogenic pathways; nonetheless, at high volumetric processing rates, a normalized energy recovery near 0.11 kWh kg−1 COD can compete or exceed anaerobic digestion [22].

The implications for wastewater treatment are twofold. First, pilot MFCs demonstrate that the core task of wastewater purification is achievable. Effluent quality meeting strict discharge standards has been produced in several studies [15,24,31]. This means that MFCs could, in principle, be adopted as primary or secondary treatment units. Second, MFCs offer energy-efficient treatment. They treat wastewater while producing electricity, potentially lowering net energy demands. For example, integrating an MFC can reduce aeration requirements by 70% [24] or generate enough electricity to power small devices [32]. These benefits could be especially attractive in decentralized or rural locations, where a self-powered treatment system could handle domestic wastewater while powering lights or sensors. However, the requirement for longer retention times implies larger reactors and potentially higher capital or land costs than conventional systems. Improving kinetics through better electrodes, microbial selection, or supplementary electrical stimulation (e.g., [3]) will, therefore, be critical. Where MFCs cannot consistently hit all targets, they may serve as pretreatment or improving units in line with conventional processes, cutting overall energy and chemical use. Hence, pilot studies confirm that high COD and pollutant removal efficiencies are attainable; the next step is to make this performance robust across seasons and waste types while ensuring cost-effectiveness, enabling MFCs to help move wastewater treatment toward energy neutrality or positivity.

5. Power Generation and Energy Recovery

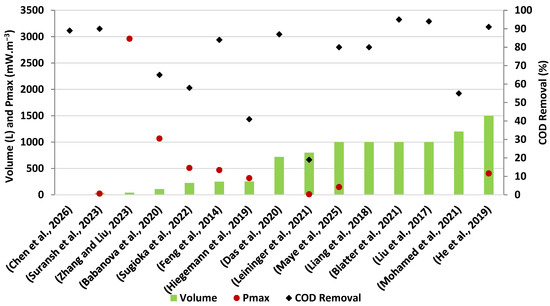

One of the features that defines MFCs is their ability to convert organic waste directly into electricity. At the pilot scale, however, achieving high power densities and useful energy output has been challenging. Therefore, strategies to enhance power generation, such as stacking cells to increase voltage or current, optimizing operational conditions for maximum power, and demonstrating real-world energy use of MFCs, have been practiced. Series and parallel stacking are the primary methods. Walter et al. [32] connected fifteen MFC units in series to power LED lights without external transformers. Chen et al. [34] operated forty-five units in parallel to multiply the total current. Some pilots incorporated power-management systems to harvest the energy from low-voltage MFC modules and boost it [38,39]. Suransh et al. [27] used a DC-DC boost converter to raise stack voltage from 0.7 V to 4.1 V for lighting an LED, acknowledging that raw MFC voltages are low. However, the use of power management systems was not that common in pilot-scale MFCs. Blatter et al. [2] and Maye et al. [23] built large stacks (sixty-four cells) to achieve higher voltages. The latter used a control circuit to block cell reversal under uneven loads. Beyond stacking, many studies performed polarization curves to select external resistances that maximize power, and some adjusted loading rates and flow conditions. Walter et al. [25] showed that a short HRT (3 h) increased power in a stratified MFC, while a longer HRT reduced output. Increasing feed concentration or delivering batch pulses of substrate was also tested, though most pilots operated in continuous flow. Material improvements—better catalysts and larger surface area—were inherently intended to reduce overpotentials and boost power. Crucially, several pilots aimed to demonstrate practical energy use. Walter et al. [32] and Das et al. [18] used MFC power to run lights in real sanitation facilities, showing that even modest output can be utilized on site. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between reactor size and performance in pilot MFCs.

Figure 1.

Reactor volume, maximum power density (mW m−3), and COD removal efficiency (%) of pilot-scale MFC systems reported in the literature (Pmax value of 60,000 mW m−3 reported by Liang et al. [15] is not shown due to its much higher magnitude compared with the other studies) [2,3,15,16,18,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,31,33,34].

Power densities achieved in pilot MFCs remain limited compared with laboratory cells but show incremental improvements. Many systems report power densities between 0.1 and 10 W m−3. Sugioka et al. [24] measured maximum power around 0.5 W m−3 in their 226 L sewage MFC, and Hiegemann et al. [28] obtained 0.32 W m−3 in a 255 L unit before fouling occurred. He et al. [31] reported a stable output of 0.41 W m−3 from a 1500 L microbial electrochemical system. By contrast, the low-cost MFC built by Suransh et al. [27] produced only 0.024 W m−3, reflecting the trade-off associated with inexpensive materials and higher internal losses. Liang et al. [15] reported a maximum power density of 125 W m−3 under optimized conditions using an artificial high-strength substrate; however, under continuous real wastewater, the system delivered 7–60 W m−3, a more realistic range. Walter et al. [25] showed that a membrane-less self-stratifying MFC could reach 69.7 W m−3 at a 3 h HRT, more than double the 32.2 W m−3 of a ceramic membrane MFC, indicating that eliminating the membrane reduces internal resistance and boosts current, though at the expense of energy efficiency per COD removed. Chen et al. [34] demonstrated linear scaling of power with unit number. A forty-five-unit stack produced 43.5 times the power of a single unit, suggesting that modules do not significantly interfere with each other when aggregated. Real-world demonstrations of pilot MFCs were limited but representative. Walter et al. [32] powered LED lighting in a public toilet continuously for six days using only MFC stacks fed by urine; their fifteen-module stack provided between 0.28 and 0.86 W (280–860 mW) over 136 h, directly lighting LEDs. An eighteen-module stack with an LED driver delivered 0.49–0.68 W, showing that direct connection was more efficient as the MFCs self-adjusted to the load. Das et al. [18] used their 720 L system to generate a maximum of 61 mW to illuminate toilet premises.

Energy conversion efficiencies were also reported in a few studies. Blatter et al. [2] achieved 5.8–12.1% of energy efficiency (by comparing generated energy per kilogram of COD in wastewater with the theoretical maximal recoverable energy of 3.86 kWh kg−1 COD). Babanova et al. [22] reported a normalized energy recovery of 0.11 kWh kg−1 COD removed (higher than the normalized energy recovery of an anaerobic digestion treatment plant with energy recovery from methane). Sugioka et al. [24] produced only 1.7–4.6 Wh m−3 of treated sewage, illustrating the modest energy yields typical of pilot MFCs.

Critical evaluation reveals that despite notable advances, pilot MFCs deliver relatively low power densities in absolute terms. Even the best continuous outputs—a few watts per cubic meter—are orders of magnitude too low to power substantial equipment at wastewater plants. Scale-up intensifies this challenge. Larger reactors have higher internal resistance and lower substrate concentrations, reducing current. The drop reported by Liang et al. [15] from 125 W m−3 in ideal tests to 7–60 W m−3 under real conditions exemplifies how laboratory-scale peaks do not translate directly. Trade-offs between optimizing power and treatment or energy efficiency are evident. Operating at a short HRT or high loading boosts current [25] but often reduces COD removal or energy efficiency per kg COD. Adding aeration or minimizing resistance can raise power, but at the cost of external energy input or stability. These contradictions raise a key question: is the priority energy production or treatment? Most pilots attempted to balance both, but if power output is prioritized, one might accept lower treatment to operate the MFC as a power generator. The successful lighting demonstrations, though small, prove that MFC energy can be directly utilized; however, they also underline how limited the energy is—powering a few LEDs for a week is a milestone for off-grid sanitation but does not significantly offset energy use in a treatment plant. Reliability is another concern; many pilots report initial peak power, but few maintain high output over long periods. Fouling, biofilm shifts, and environmental factors often cause power to decay. Large electrodes behave like capacitors or batteries; power measurements based on short polarization tests may be inflated by stored charge and not reflect sustainable output [15]. Efficiently harnessing energy from dozens of MFC cells also remains largely unexplored; apart from LED lighting, no pilots have attempted to invert power to alternating current or run motors. The complexities of wiring, sealing, and controlling many units—and preventing voltage reversal—add to the challenge. Nevertheless, some positive pathways are apparent; increasing electrode surface area, minimizing resistance, stacking cells with proper control, and using hydrophobic coatings or catalysts can incrementally improve power density. The linear scaling demonstrated by Chen et al. [34] and the self-regulating stack by Blatter et al. [2] suggest that modular approaches can accumulate power but at the cost of complexity.

The implications for energy recovery are realistic but optimistic. Pilot MFCs will not be major power generators in the near term; instead, their value lies in offsetting a portion of the energy used in wastewater treatment. They may, therefore, be marketed not as power plants but as energy-saving treatment units. The ability to generate any electricity from wastewater is a unique selling point, especially for remote or resource-poor locations where small, autonomous power sources for lighting or sensing can improve sanitation. Future improvements may come from stacking and parallelization combined with integrated control to avoid voltage reversal and reduce losses. Modular “MFC cartridges” could be standardized, enabling arrays to scale power by adding units, much like solar panels; however, each module increases maintenance demands, and balance-of-plant engineering (pumps, wiring, and control circuits) will be crucial to ensuring reliability. Some pilots achieved relatively high energy conversion efficiencies (Walter et al. [25] reported 50% theoretical energy conversion in a ceramic MFC at a 24 h HRT), hinting that, with the right design, a large fraction of organic energy can be captured. If materials and architectures can raise both efficiency and power density, future MFCs might produce tens of kilowatt-hours from treating 1000 m3 of wastewater, significantly offsetting plant energy consumption. Until then, niche applications such as off-grid sanitation or sensor networks may pave the way, demonstrating reliability and benefit. Overall, pilot studies imply that MFC technology can gradually shift wastewater treatment from an energy sink toward energy neutrality or positivity, provided that continued innovation in power density, materials, and system integration addresses the remaining limitations. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of the operating conditions and performance metrics of various pilot-scale MFCs treating real wastewater. Key outcomes, such as COD removal percentages, loading rates, and achieved power densities, are compiled in Table 2, highlighting typical performance ranges and efficiencies observed under field conditions.

Table 2.

Operating conditions and performance metrics of pilot-scale MFC systems treating real wastewater.

6. MFC Life Cycle Assessment

Life cycle assessment (LCA) has become an essential tool for evaluating the environmental viability of MFC systems for wastewater treatment and resource recovery. Recent studies have applied LCA to MFCs in a range of frameworks, from heavy metal removal [40] to actual wastewater treatment [41,42]. LCA establishes a foundation for understanding the potential benefits and drawbacks of MFC technology in sustainability terms. However, LCA approaches vary considerably across studies. Researchers have defined different functional units and system boundaries—for instance, one analysis used 1 kg of pollutant removed as the basis [40], whereas others used a standard volume of wastewater (often 1 L or 1 m3) over an assumed reactor lifespan [41,43]. Most studies follow widely accepted LCA guidelines and include cradle-to-gate or cradle-to-grave scopes, but the selection of impact assessment methods and categories is not uniform. As a result, direct comparisons between studies must be made cautiously, yet common themes emerge regarding MFC environmental performance.

A key focus in the literature has been the comparative performance of MFC-based systems versus conventional wastewater technologies. LCA results so far draw a mixed picture of when MFCs provide environmental advantages. In an application of hexavalent chromium removal, an MFC-based process demonstrated a dramatically lower carbon footprint than traditional treatment methods—on the order of –0.44 to +0.8 kg CO2-eq per unit pollutant treated versus 2.8 kg for ion exchange and 28.8 kg for chemical reduction [40]. This indicates that for certain high-impact pollutants, MFCs can outperform incumbent technologies in terms of global warming impact. However, in more general wastewater treatment scenarios, MFCs alone have not consistently outperformed conventional systems. For example, a constructed wetland (CW) was found to have a lower overall climate impact (142.3 kg CO2-eq) than an equivalently sized stand-alone MFC, largely because the wetland relies on passive biological processes with minimal inputs [44]. Yet, integrating an MFC with CW (a hybrid CW-MFC) yielded other benefits; the combined system enhanced pollutant removal efficiency (e.g., achieving >80% removal of COD and nitrogen compounds) and produced 2.68 kWh of electricity [44]. This integration slightly increased GHG emissions compared to the natural wetland but significantly reduced nutrient emissions (lowering eutrophication potential) due to the improved treatment. Similarly, in an industrial application, adding a tubular MFC to an anaerobic treatment line for beef-processing wastewater cut net greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 36%—capturing energy that would otherwise be lost—though it also reduced biogas output, resulting in a trade-off of higher fossil fuel use elsewhere in the process [42]. On the other hand, some studies have highlighted that if the energy recovery of an MFC is too low, its manufacturing and operation can lead to higher impacts than conventional methods. An LCA of a novel osmotic MFC, for instance, reported a higher GWP than a benchmark conventional treatment plant, attributable to resource-intensive components like polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) casing and stainless steel cathodes [45]. Likewise, an early evaluation of MFC-integrated wetlands showed comparable or slightly greater impacts than standard wetlands in most categories, with one MFC design doubling the abiotic depletion impact due to extensive stainless steel electrodes [43].

Another frequent insight is that MFC design and configuration choices strongly influence LCA outcomes. Across the literature, various MFC architectures (single vs. double chamber, batch vs. continuous flow, etc.), electrode materials, and cathode designs in search of more sustainable configurations have been explored. Material selection, in particular, can affect the environmental results. One study focusing on the cathode found that using a graphite electrode instead of a platinum-coated titanium one reduced the cradle-to-gate GWP of MFC by roughly 99%, essentially eliminating most of the burden associated with precious metal production [46]. Another work compared five distinct MFC configurations from an air cathode MFC, an H-type MFC, a U-type MFC, a flat MFC, and a modularized MFC [47]. Notably, a flat-plate MFC design that required a long hydraulic retention time to treat the water showed overall impacts about 60% higher than those of the other four designs, indicating that reactor efficiency and scaling are crucial—prolonged treatment time can result in excessively higher energy use and material requirements. In contrast, the other configurations, which operated more efficiently, had considerably lower and fairly similar impact profiles.

Moreover, coupling MFCs with additional treatment or resource recovery processes can also shift results. Chin et al. [41] evaluated advanced hybrids like an MFC coupled with membrane distillation (to purify water) and a microbial electrolysis cell (to produce hydrogen gas). These integrated designs were among the most environmentally favorable in that study because their value-added outputs (reusable clean water and hydrogen fuel) effectively offset some of the environmental costs. In general, any configuration that yields useful co-products or higher power output tends to improve the LCA balance for MFCs. Conversely, designs that incorporate materials like platinum catalysts or extensive stainless steel tend to drive up impacts, notably in categories such as human toxicity and metal depletion [41,43]. For instance, using a gravel-based anode with large stainless steel current collectors in a wetland MFC doubled the abiotic resource depletion impact compared to a graphite-based anode [43]. Similarly, the innovative OsMFC mentioned above, while technologically promising, underscored how novel components (e.g., osmotic membranes and specialized structural materials) can introduce new environmental burdens if not carefully managed [45].

The LCA studies reveal a few frequent environmental impact hotspots in the MFC life cycle, alongside potential mitigation strategies. The fabrication and materials of the reactor often dominate the embodied impacts. For example, producing the MFC unit for a metal-waste recovery system was responsible for roughly 11 kg CO2-eq of emissions, overshadowing many downstream process contributions [40]. High-impact materials such as metals (steel and copper), membranes, and catalysts appear frequently as major contributors in categories like climate change, resource depletion, and toxicity [41,45].

Another hotspot is energy consumption during operation. Several analyses reveal that running pumps, maintaining flow, or supplying aeration/heat (depending on the design) can account for between 60 and 90% of the total global warming impact of MFC wastewater treatment systems [41,47]. This is problematic because, in their current state, MFCs typically generate only a modest amount of energy—insufficient to offset more than a small fraction of what they consume. Chin et al. [47] found that the electricity produced by their MFC setups could counteract at most 2.7% of the system’s own energy demand (in the best case). This imbalance between energy input and output means that unless MFCs achieve much higher power densities, they risk remaining net energy consumers with associated emissions. A related issue is incomplete pollutant removal; while MFCs reliably reduce, they may only partially remove nutrients, which can lead to environmental impacts when the effluent is discharged. In a study by Chin et al. [47], nitrogen and phosphorus left in the MFC effluent contributed up to 86% of that system’s freshwater eutrophication impact, highlighting the need for integrated nutrient removal in MFC-based treatment systems.

To address these issues, several improvement strategies and future directions have been proposed. A common recommendation is to substitute or reduce the use of environmentally intensive materials. For instance, avoiding precious metal catalysts [46] and minimizing stainless steel components [43] can significantly cut toxicity and resource-depletion impacts. Process optimization is another important avenue; operating conditions that maximize power output or treatment efficiency can improve the benefit-to-cost ratio of impacts. Indeed, researchers often emphasize that increasing MFC power density and longevity is crucial—one projection held that raising power production to around 500 W m−3 could make MFCs net contributors of renewable energy rather than net consumers [41]. Such leaps in performance might be achieved through strategies like stacking multiple cells (as discussed in the previous sections), enhancing biocatalyst activity, or improving electrode architecture. Additionally, integrating MFCs with other treatment steps offers synergistic benefits, as seen with hybrid systems that generate clean water or utilize waste biomass. At the same time, integration must be managed carefully to avoid merely shifting burdens; the trade-off observed by Li et al. [42]—where adding an MFC stage reduced methane (biogas) generation in an anaerobic digester—is a reminder that a holistic design of hybrid systems is needed.

Studies call for moving beyond lab-scale analyses and conducting pilot- or full-scale LCAs to capture realistic efficiency losses and material demands at scale [40,47]. As discussed earlier, research readily acknowledges that lab-scale prototypes may not scale linearly to real-world systems. Lifespan assumptions (often around 10 years) and other uncertainties (e.g., future electricity mix and material recycling rates) also introduce variability in the results. Despite these uncertainties, the collective research provides a clearer picture of where to focus improvements. Overall, the evidence so far suggests that while MFCs are a promising and innovative approach, they still have a long way to go before they can be considered a broadly sustainable solution. The path forward will likely require continued innovations in materials, system integration, and—especially—major gains in energy efficiency to truly unlock the potential environmental benefits of MFCs.

7. Challenges

As discussed, scaling up MFCs from lab prototypes to pilot-scale systems has been a difficult path, revealing several fundamental challenges. A primary challenge is the severe decline in power output observed at larger scales. Many pilot-scale MFC studies report that power densities in scaled MFCs are far lower than in the lab scale due to increased internal resistance and mass transfer overpotentials [18,34]. The intrinsic low power density of single enlarged MFC units means that even big reactors produce limited power, which limits their practical economic viability [26,34]. This intense performance gap suggests that simply enlarging reactor size does not linearly convert to higher power. In fact, scaling often increases inefficiencies. Hence, many scaled-up MFCs struggle to maintain stable electrical outputs, highlighting that power recovery must be improved by an order of magnitude for MFCs to compete with conventional energy systems [18].

Another constant challenge is material fouling and maintenance [18]. Large-scale MFCs operating on real wastewater frequently show clogging and material (electrode and membrane) fouling [28]. Similarly, biofouling (e.g., fungal growth on air cathodes) has been reported to significantly reduce MFC performance [18]. These fouling issues necessitate regular electrode cleaning or replacement, which is impractical at scale, challenging long-term operation and operational stability.

Multicell stacks often face voltage reversal phenomena, where individual cells in series become polarized incorrectly under uneven loads or fuel distribution [23,32]. Without careful management, stacked MFC units can destabilize each other, which is not an issue at the lab scale [23]. Real wastewater adds another layer of complexity through its inherent changes in composition and temperature. Pilot-scale experiments have shown that low- or variable-strength wastewater can lead to periods of substrate starvation and anode potential decline, further limiting power generation [18,24]. Additionally, natural environmental conditions (e.g., lower temperatures and presence of competing microbes) often cause slower acclimation and less reproducible performance compared to controlled lab conditions [2,29], illustrating the prolonged startup times required at a large scale.

High costs and material limitations also slow down scaling efforts. Early pilot MFCs relied on expensive components such as proton exchange membranes (e.g., nafion) and platinum catalysts, which make large reactors prohibitively costly [18,31,46]. Even basic construction expenses scale up quickly; for instance, building robust, large-area air cathodes that can withstand continuous use has proven to be challenging and expensive [2,31]. Thus, many research teams have identified material cost and availability as key bottlenecks in moving MFCs to industrial scales [15,26].

An equally critical barrier involves the substantial material and environmental footprint associated with scaling up MFCs. Life cycle assessments consistently reveal that manufacturing reactor components (electrodes, membranes, catalysts, etc.) can incur significant greenhouse gas emissions and resource consumption relative to the system’s outputs. For instance, producing a pilot-scale MFC reactor can emit on the order of 10–12 kg CO2-equivalent per unit—largely due to energy-intensive metals and plastics—while polymer components, such as PMMA sheeting and PTFE binders, further contribute substantially to the overall global warming potential [40,45]. These findings indicate that simply building an MFC infrastructure can create a large environmental debt upfront, especially when unsustainable materials are used. Moreover, LCA results are highly sensitive to material choices. Small substitutions (for example, using a graphite electrode in place of titanium) have been shown to dramatically shrink an MFC system’s carbon footprint [40,46]. The heavy initial impacts of current designs thus remain a core concern, casting doubt on the ecological viability of scaling up without significant material innovations.

Finally, there are biological and scaling issues that remain problematic. Maintaining an electroactive biofilm without any major community shift or stratifying in a large reactor was reported to be difficult. For example, scaled systems have shown spatial variation in microbial activity—certain regions of a big electrode become less active, possibly due to nutrient or oxygen gradients, leading to underutilized zones [33]. Moreover, as wastewater is treated along the flow path, the remaining degradable organics decrease to low levels that can decline electrogenic biofilm strength toward the outlet, causing power output to fall [2]. Hence, low energy recovery, fouling and maintenance demands, control difficulties in stack configurations, high capital cost, unresolved biological complexities, long-term stability, maintenance requirements, and integration into existing wastewater treatment infrastructure are still poorly understood and among the major challenges in pilot-scale MFCs. These challenges have, so far, kept MFCs from realizing their full promise at a real scale. Nevertheless, recognition of these barriers has driven researchers to explore innovative solutions, discovering encouraging prospects for scaling up MFC technology.

8. Prospects

Despite the mentioned challenges, recent pilot studies have provided proof of concept that larger MFC systems can operate successfully, treating waste and even generating usable power. A number of studies report that pilot-scale MFCs have achieved significant pollutant removal under real-world conditions while maintaining electricity generation [15,22]. Moreover, the reported large-scale systems showed stable performance over long periods. In domestic wastewater studies, pilot MFCs have not only met effluent standards but also generated enough energy to power small devices (e.g., light LED lamps). This simultaneous waste treatment and energy recovery is convincing proof that the MFC concept works at a large scale, even if power levels are still low. The pilot study results confirm that MFC technology can “close the loop” by using waste as a fuel to support its own operation or auxiliary functions.

Moreover, studies have engineered innovative designs and strategies that mitigate some scale-up issues and improve performance. One successful approach is the modular stacking of MFC units rather than building a single huge reactor. By electrically or hydraulically linking many smaller cells, total volume and power can increase while keeping each unit at an optimal size. The findings showed that stacking multiple up-flow MFC modules yielded higher treatment efficiency and power density than simply enlarging one reactor, thanks to improved mass transfer in each unit [26]. Several projects have demonstrated near-linear scaling of power with the number of modules, indicating that power outputs can scale almost linearly with cell count when modules are integrated effectively [34]. Smart power management systems have also further enhanced multiunit MFCs [23]. Such results show that technical adjustments, like voltage control circuits, maximum power point tracking, and independent electrode control, can overcome the instabilities that previously challenged MFC stack systems, enabling sustained power generation.

Another promising strategy has been the use of alternative low-cost materials to address economic challenges. Some pilot studies replaced expensive proton exchange membranes with cheap separators or omitted membranes entirely yet still achieved good performance [25,29]. For example, ceramic-based membranes and earthenware components have been used in place of nafion and found to be effective and durable in field studies [27]. Likewise, non-precious catalysts have successfully substituted platinum on cathodes without significant loss of efficiency while cutting costs and lowering embedded emissions [42,46]. These material innovations greatly reduce the cost per volume of scaled MFCs and improve their practicality. The prospects for economic scalability are reinforced by such measures, which suggest that future MFC systems can be built and operated at a fraction of previous costs. Moreover, from an LCA perspective, innovations in how MFCs are built, from advanced cathode materials to more efficient configurations, suggest a viable path toward mitigating the footprint of larger-scale systems.

Pilot studies have also started to integrate MFCs into realistic application scenarios, which highlight the potential niche applications of the technology. Rather than aiming to power a grid, scaled-up MFCs can play a critical role in decentralized and sustainable wastewater management. One notable example is the stacking of urine-fed MFC modules, an example of which continuously powered LED lighting in a remote public toilet without any battery, purely on waste-derived electricity [32]. This shows how MFCs could serve off-grid sanitation systems by simultaneously treating waste and providing lighting or sensor power. In municipal sites, the concept can be to retrofit wastewater treatment plants with MFC units to offset some of their energy consumption.

Another promising approach is to integrate MFCs with complementary wastewater treatment processes or to deploy them in niche applications where their strengths can offset their weaknesses. Constructed wetland–MFC hybrid systems are one example that has gained attention. By coupling MFC units with wetland reactors, these designs achieve simultaneous pollutant removal and energy recovery in a largely passive setup, significantly lowering net environmental impacts per volume of wastewater treated [43,44]. This hybrid approach can reduce land footprints by around 20% compared to a conventional wetland, and it maintains low emissions, although the inclusion of MFC components does increase upfront costs.

Even partial integration can have an impact. Some studies suggest that MFCs are “energy-positive” wastewater treatment technology and might one day replace energy-negative processes like aerated activated sludge, at least for small-scale or rural wastewater treatment, where energy is scarce [18,26]. While this goal still seems far off, the early pilot studies highlight a genuine potential that MFCs can treat real waste streams, remain operational for months or years, and yield net energy in certain forms. The progress from improved reactor designs and electronics to cost-cutting and pilot demonstrations draws a cautiously optimistic picture.

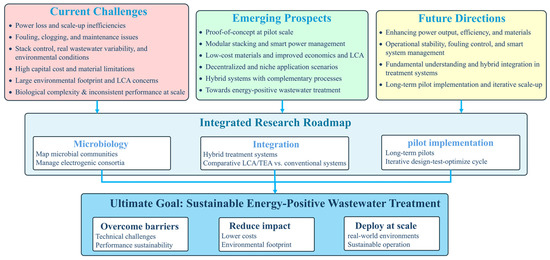

The next section outlines the key research directions that have been proposed to further accelerate this progress. Figure 2 offers a combined roadmap of the challenges, opportunities, and future research directions for scaling up MFCs. It visually summarizes the major challenges identified, the prospects or recent improvements, and the priority areas for upcoming research that are discussed in the next section.

Figure 2.

Summary of challenges, prospects, and future research directions for MFC scaling up, along with a research roadmap.

9. Future Research Directions

Considering the current findings on MFC implementation, the literature highlights several key areas where further research is necessary to overcome remaining barriers and accelerate MFC scaling. One urgent priority is boosting the power output and efficiency of scaled MFC systems. Practically every study acknowledges that without higher current and power densities, MFCs will remain limited to niche uses. Future research, therefore, should be focused on technical innovations to extract more energy per unit volume. This includes reducing internal resistance through better system architecture (e.g., minimizing electrode spacing and using highly conductive materials) and enhancing reaction kinetics with improved catalysts or biocatalysts. For instance, novel electrode configurations like 3D brush anodes or fluidized beds are being explored to increase the electrode surface area accessible to biofilm and thereby drive up currents [24,30]. Likewise, studies are investigating ways to provide sufficient oxygen to large air cathodes without incurring huge energy costs—such as optimizing aeration methods or developing passive aeration cathodes—to improve oxygen reduction reaction at scale. There is also significant interest in new materials and designs that could break the trade-off between cost and performance. Durable, inexpensive catalysts (iron-based, carbon-based, etc.) and separators (ceramic membranes and dynamic biofilm separators) need further evaluation in long-term trials. By systematically selecting and testing the right materials in pilot systems, research should aim to dramatically lower construction and operating costs without sacrificing output. Some projections suggest that through mass production and material innovation, the construction cost of MFC reactors could drop to as low as USD 300 per cubic meter, which would be economically competitive with traditional treatment units [31]. Achieving such cost reductions is crucial for commercialization, so ongoing studies are looking at scaling up manufacturing techniques and using readily available materials. At the same time, the literature argues that new materials and reactor components should be evaluated not only in terms of performance and cost but also through comprehensive LCA, explicitly considering actual energy, emissions, and end-of-life recycling or disposal pathways to ensure that apparent sustainability gains are realized in practice.

Another aspect requiring investigation is how to maintain operational stability and reliability over long periods. Solutions to issues like cathode fouling, mentioned earlier, are being actively researched. Some teams are experimenting with self-cleaning mechanisms or periodic regeneration protocols, while others suggest advanced coatings that prevent biofilm overgrowth or mineral scaling on electrodes. Future work is also expected to address persistent problems such as membrane fouling; the formation of unfavorable by-products; and the maintenance of robust, electrogenic microbial communities under fluctuating hydraulic and loading conditions. In parallel, smarter control strategies are needed to handle the dynamics of multiunit systems, for example, passive control methods that avoid the need for complex electronics or failsafes that prevent cascade failures in large stacks. Future work should likely explore these control aspects, possibly drawing on machine learning to predict and mitigate problems like voltage reversal or performance drift in real time. The goal is to design MFC systems that can run autonomously in the field with minimal human intervention, which is essential for practical deployment in remote or resource-limited settings.

Another important perspective is deepening the fundamental understanding of MFC behavior at real scales, which will inform better designs and operation. Studies note that many phenomena observed in pilot reactors—such as uneven biofilm activity, unexpected limiting factors, or community shifts—are not well understood. Future studies will, therefore, prioritize microbial and electrochemical dynamics in large MFCs. High-resolution analyses of microbial communities in different parts of scaled systems could reveal which organisms thrive or decline and why. Such knowledge may guide strategies to inoculate or maintain desirable electrogenic bacteria in large reactors, ensuring consistent performance. Similarly, understanding how scale-up affects electron transfer mechanisms—for instance, how increased electrode distances or different flow regimes impact the electron flow—should be a subject of ongoing research. In addition, integrative research that combines MFCs with other treatment steps is seen as a promising direction. Since MFCs alone might not fully meet discharge standards, researchers advocate exploring hybrid systems—e.g., MFCs preceding or following conventional processes. Studying how MFC units can be incorporated into existing wastewater infrastructure to upgrade it (for energy recovery or improved removal of certain contaminants) is highly relevant for future deployment. This includes investigating the optimal stage in treatment systems to employ MFCs. Recent review work further recommends that such hybrid and retrofit configurations be evaluated through comparative LCA and technoeconomic analysis, benchmarking MFC-based treatment systems not only against stand-alone MFCs but also against other bioelectrochemical systems and conventional wastewater technologies. Placing MFC units as supplemental secondary-treatment or polishing steps in full-scale plants is frequently highlighted as a realistic near-term role, where their energy recovery function can complement existing infrastructure.

Finally, long-term pilot studies and scale-up demonstrations continue to be crucial. The literature emphasizes that operating MFC prototypes in real environments for months to years is the only way to uncover unanticipated challenges and to validate solutions under practical conditions. As a result, future research will likely involve more pilot projects in various contexts (municipal wastewater, industrial effluents, and rural settings), each contributing empirical data to refine scale-up strategies. This iterative approach—alternating between field experimentation and design optimization—is needed to gradually close the gap between what is achievable in the lab and what is needed in the field. The rationale for such sustained research effort is clear; improving the scalability of MFCs addresses a pressing global need for sustainable wastewater treatment. If power output can be increased and costs driven down, MFC technology could offer a unique solution by turning waste streams into electricity while treating water, aligning well with energy and environmental goals. Given the rising energy costs and climate impact of conventional treatment plants, there is strong motivation to pursue MFC scale-up now. Each incremental advance (whether it is a 10% boost in efficiency or a 20% cost cut) brings MFCs closer to real-world viability, making this an exciting and timely area for continued research.

10. Conclusions