Abstract

Leadership speeches delivered within the United Nations and UNESCO play an active role in shaping global policy discourse. As widely circulated texts, they influence how policymakers understand sustainability, responsibility, and education by defining global challenges, allocating responsibility, and communicating shared priorities. This study examines how these concepts are articulated in selected leadership speeches delivered between 2022 and 2025. The analysis adopts a pragmatic framing approach informed by non-linear pragmatic theory. It focuses on six interrelated dimensions: problem definition, causal responsibility, treatment responsibility, value framing, future-oriented framing, and education-specific framing. The findings show that sustainability is consistently framed as a complex ethical challenge linked to climate change, social inequality, and global injustice. Responsibility is presented as shared but uneven, with greater obligations assigned to high-income countries, international institutions, and education systems. Education is addressed both directly, through references to curriculum reform, teacher preparation, and higher education leadership, and indirectly as a means of supporting climate resilience, ethical technological development, and global citizenship. Overall, the study demonstrates that leadership speeches function as influential discursive sites through which sustainability narratives are advanced and priorities for Education for Sustainable Development are communicated, highlighting the value of pragmatic framing for research on international sustainability communication.

1. Introduction

Sustainability is a pressing issue in the current global governance landscape. In the face of rising global challenges, including rising temperatures, social inequalities, and the interdependence of social, economic, and environmental systems [1], organizations such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the United Nations (UN) together with their affiliated institutional actors play critical roles in articulating global perspectives on issues related to sustainability. Education is frequently described as a key driver in shaping a more equitable and sustainable society [2]. This perspective is evident in UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) initiatives, where education is presented as a value-driven process that prepares learners not only to understand the world around them but also to change it [3,4,5].

Sustainability, Responsibility, and Education in Global Discourse

Although sustainability and education feature prominently in global reports and policy documents, there has been comparatively less examination of how they are framed discursively in global leadership speeches. Speeches matter because they articulate the narrative frameworks through which global publics and national governments interpret sustainability challenges [6,7,8]. Yet despite their visibility, speeches have received far less scholarly attention than formal policy documents [9,10]. Most existing analyses focus on strategies [2,11], frameworks [12,13], or curricular models [14,15,16] for sustainable development while overlooking the rhetorical spaces where leaders publicly negotiate urgency, blame, responsibility, and the imagined futures of education. This leaves a gap in understanding how leadership framing contributes to sustainability meaning-making.

This study addresses this gap through an in-depth qualitative framing analysis rather than a large-scale corpus approach. Its aim is not statistical generalization but the close examination of how sustainability, responsibility, and education are discursively constructed within high-salience leadership communication. Focusing on a small, carefully selected set of authoritative speeches enables analytical depth and theoretical precision in tracing meaning-making strategies within institutional discourse.

Framing theory [6] provides a useful lens for addressing this literature gap, as it shapes public interpretation by outlining problems, attributing causes, offering moral interpretations, and suggesting solutions [6,17]. Studies on responsibility framing [18,19,20,21] describe differences between causal responsibility (identifying who or what is to blame) and treatment responsibility (identifying who should act), revealing important cultural and geopolitical differences in the allocation of responsibility. For instance, the comparative study in [21] shows how media frames responsibility for climate issues differently in China and the United States. Such findings, which reflect how language reveals ideological positions or national interests, emphasize the importance of examining responsibility framing at the UN and UNESCO levels, given accountability negotiations at the global level [7,21,22]. Yet, this field has not been thoroughly investigated because previous studies have mostly focused on media or national-level politics rather than global institutional leadership [21,22,23].

Leadership speeches also serve as platforms for expressing shared values and for conceptualizing visions for the future [21,22,23,24]. UNESCO’s “Reimagining Our Futures Together” [24] asserts the need for shared narratives grounded in solidarity, human rights, and ethical accountability. Accordingly, leadership discourses become performative, that is, they motivate, legitimize, and communicate institutional priorities along with the competencies and responsibilities that need to be developed and cultivated through education [4,7,24]. Parallel to this, research on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) shows that education becomes increasingly understood as a transformative approach toward the challenges of sustainable development, influencing learners’ knowledge, skills, values, and capacity for action [4,23,25]. Yet little is known about how global leaders themselves frame education and ESD within the sustainability discourse.

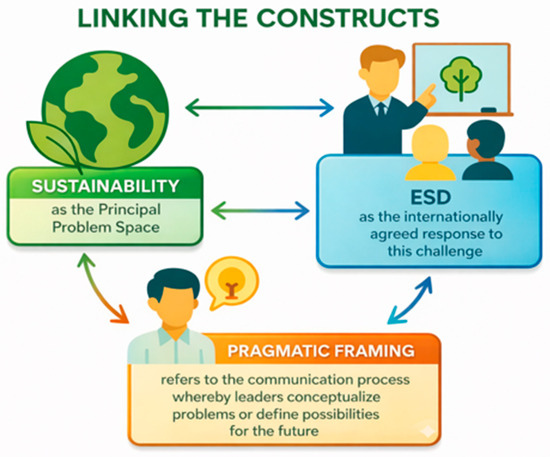

This paper adopts a conceptual framework that originates from the concepts of sustainability, Education for Sustainable Development, and the principles of pragmatic framing theory [6]. Sustainability is understood as a multifaceted ethical issue in which eco-logical integrity is intertwined with social justice and global accountability [26,27,28]. Education for Sustainable Development is viewed as a paradigm shift that aims to promote the knowledge, values, and competencies essential to achieving the concept of sustainability [3,4,23,29]. Pragmatic framing theory, on the other hand, serves as a conceptual lens for analyzing the construction of meaning, the identification of responsibilities, and the communication of possible futures through language use, appeals, and contextual parameters [6,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Figure 1 outlines the linkages between the three constructs; it was generated through Gemini (Google AI).

Figure 1.

Linking the three constructs.

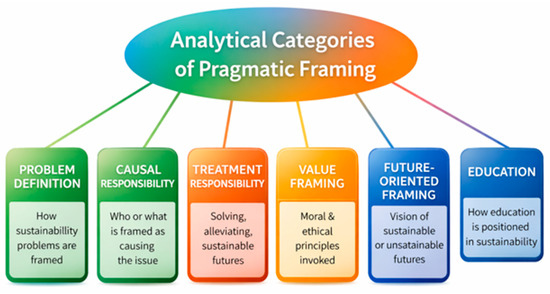

Building on this theoretical foundation, the present study is organized within six practical framing categories, which are continuously evident within sustainability communication discourse: Problem Definition [6,7], Causal Responsibility [6,21], Treatment Responsibility [6,22], Value Framing [7,23], Futures-Oriented Framing [24,30], and Education-Specific Framing [4,23]. These enable a practical, theoretically informed exploration of how leaders encode meaning, negotiate accountability, and convey future intentions. Individually and cumulatively, such framing categories comprise a practical analytical tool for interpreting sustainability meaning-making, obligation allocation, and the role of education, specifically ESD, within global transformation.

To summarize, the literature discussed above reveals that there are three overlapping gaps:

- (1)

- a lack of research on how sustainability is framed through senior speeches at the UN and UNESCO;

- (2)

- insufficient understanding of how responsibility is negotiated in institutional discourse;

- (3)

- a lack of analysis of how education in general, and ESD in particular, is positioned within these framings.

To address these gaps, the present study examines five speeches delivered by senior leaders and institutional representatives of the United Nations or UNESCO between 2022 and 2025, using a pragmatic framing approach that integrates the six frames discussed above. Pragmatic framing explains how meaning is made by language choices, appeals, and contextual features, making it the ideal approach for examining leadership discourse [6]. Accordingly, the study emphasizes analytical generalization and theoretical insight into elite institutional discourse rather than empirical representativeness.

Three questions guide the present study:

- How do UN and UNESCO leaders frame sustainability in their public speeches?

- How is causal and treatment responsibility negotiated within these speeches?

- What role does Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) play in these framings of sustainability?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The current research employs an interpretive qualitative research paradigm [31] to investigate how sustainability, responsibility, and education have been framed in high-level speeches within UN and UNESCO governance contexts. This approach is grounded in the Pragmatic framing theory [32], which holds that communicative meaning is determined by the context of communication, the speaker’s intent, value appeals, and selective emphasis. This approach is particularly appropriate for analyzing leadership discourses, where language is used not only to inform but also to motivate, legitimize, and influence public understanding [32].

2.2. Speech Selection and Sampling Criteria

Five speeches given by senior leaders and institutional representatives within the United Nations and UNESCO governance settings between 2022 and 2025 (see Table 1) were purposively sampled. They were selected because they reflect moments in which sustainability was explicitly articulated as a policy priority and directly linked to the future of education within global governance discourse. The speeches constitute a purposively selected, meaning-dense corpus that characterizes how sustainability, education, and global governance are articulated within UN and UNESCO leadership discourse. They include diversity in terms of voice, themes, and educational level, ranging from primary or secondary education to tertiary education.

Table 1.

Selected leadership speeches delivered within UN and UNESCO governance contexts (2022–2025).

The inclusion criteria involved:

- Institutional relevance: speeches given by senior leaders and institutional representatives of the United Nations or UNESCO that express global policies;

- Thematic relevance: the topics of sustainability, responsibility, climate action, or Education for Sustainable Development are prominently featured;

- Temporal significance: speeches that coincide with large-scale globally significant events (TES 2022, COP28, General UNESCO Conference 2025) that specifically addressed concepts of sustainability and educational futures (see Table 1).

This corpus preserves the crucial institutional contexts in which the discourse on sustainability is defined. This strategy corresponds with the model of qualitative discourse analysis that prefers meaning-dense texts. Although the corpus is small, this selection strategy aligns with qualitative discourse-analytic and framing-based research, where depth of interpretation and contextual sensitivity are prioritized over breadth. Recurrent authorship within the corpus is treated analytically rather than as a limitation, as it enables the examination of discursive consistency and institutional voice rather than individual variation.

2.3. Analytical Framework

The analysis applies a pragmatic framing model integrating six dimensions:

- (1)

- problem definition;

- (2)

- causal responsibility;

- (3)

- treatment responsibility;

- (4)

- value framing;

- (5)

- futures-oriented framing;

- (6)

- education-specific framing.

Figure 2 illustrates the six-dimensional model, which was generated by Gemini (Google AI).

Figure 2.

Pragmatic framing categories used in the coding scheme.

The Pragmatic framing theory emphasizes how speakers encode assumptions, highlight certain realities, and construct moral or future-oriented stances. This makes it well-suited for sustainability discourse, where leaders negotiate urgency, accountability, and pathways for global transformation.

2.4. Coding and Analytical Procedures

Data analysis involved three phases. Firstly, open coding was conducted using close reading to track recurring phrases/statements regarding notions of sustainability, responsibility, action, and education. Axial coding was used to link these notions into larger ones to aid in developing patterns across speeches. Lastly, selective coding was performed using these larger notions and pragmatically formulated questions about how leaders explain urgency and how they explain education transformation.

2.5. Trustworthiness and Reliability

To enhance the credibility and dependability of the findings:

- ▪

- Reflexive memoing was used throughout coding to track analytical decisions and avoid researcher bias.

- ▪

- Code recode reliability: The researcher conducted a second coding round after a two-week interval to ensure internal consistency.

- ▪

- Triangulation of institutional perspectives: Speeches were sourced from both the UN and UNESCO, enabling comparison across organizational discourses and reducing Single institution bias.

- ▪

- Only official, public-domain transcripts were used, ensuring the accuracy and verifiability of the analyzed texts.

Although the study is interpretive in nature, these steps align with qualitative reliability standards and strengthen the rigor of the analysis.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

All the speeches analyzed are public domain documents published by global organizations. No human subjects have been involved, nor has any personal or confidential information been considered in the analysis to make ethical clearance necessary. Each speech text has been annotated through direct quotes, analysis remarks, or interpretations.

3. Results

3.1. Framing Sustainability as a Systemic and Ethical Crisis

Throughout these five speeches, the theme of sustainability is treated not only as an environmental problem but, more importantly, as a structural problem of interdependence that translates into a crisis. There is a focus on how UN and UNESCO leaders and institutional actors define the challenges associated with sustainability, including climate disruption, increasing inequality, geopolitical instability, and global injustice. There is an emphasis on an ethics-based form of language in how these leaders define sustainability challenges. The selected excerpts presented in Table 2 illustrate how UN leaders frame sustainability (See Appendix A.1 for more illustrative examples).

Table 2.

Excerpts illustrating the United Nations leadership’s framing of sustainability.

3.2. Causal Responsibility: Structural Drivers over Individual Failure

The speeches focus more on systemic or institutional factors than on individual behavior when attributing responsibility for sustainability-related crises. Responsibility for these crises is assigned based on patterns of exploitation, development, conflict, and decisions by influential parties and wealthy countries. This position aligns with responsibility framing studies that distinguish between institutional and individual responsibility. The selected excerpts presented in Table 3 illustrate how UN/UNESCO leaders depict causal responsibility (see Appendix A.2 for more illustrative examples):

Table 3.

Excerpts illustrating the United Nations leadership’s framing of causal responsibility.

3.3. Treatment Responsibility: States, Institutions, and Education Systems

Causal responsibility rests with structural forces, while treatment responsibility is diffused among state actors, global institutions, and education systems. UN speeches appeal to state and global actors to act swiftly on climate action, conflict resolution, and inequality reduction. The UNESCO discourse can be said to expand the scope of responsibility into the education sector and to pinpoint education institutions, teachers, and universities as major players in shaping sustainable futures. Throughout these texts, responsibility for treatment is constructed as jointly undertaken and prospective. The excerpts presented in Table 4 illustrate how UN/UNESCO leaders depict responsibility for treatment (See Appendix A.3).

Table 4.

Excerpts illustrating UNESCO leadership’s framing of treatment responsibility.

3.4. Values Framing: Justice, Solidarity, and Shared Humanity

All speeches embed the theme of sustainability into a value-based narrative. Words such as justice, solidarity, dignity of humankind, peace, and reciprocity were used with considerable regularity. The emphasis on sustainability has not been just on the technical aspects, but also on the value-based effort that requires empathy, cooperation, and collectivity. The language of solidarity assumes particular importance when UNESCO reports emphasize education as an environment that nurtures empathy and citizenship. The excerpts presented in Table 5 illustrate the value-based narrative (See Appendix A.4).

Table 5.

Excerpts illustrating the UN and UNESCO leadership’s framing of values.

3.5. Future-Oriented Framing: Transformation Rather than Adjustment

The future is shaped by decisions made today, with leaders making it clear that continued inaction can lead to catastrophic consequences. Instead, transformation rather than gradual evolution of models of the economy, education systems, and societal values has been advocated in these speeches. Urgency and limited time scales associated with UN General Assembly messages define United Nations discourses on education. On the other hand, UNESCO speeches adopt a hopeful, visionary tone, encouraging societies to re-imagine futures through education, cooperation, and ethical leadership. Across the corpus, the future is constructed as both fragile and improvable. The selected excerpts presented in Table 6 illustrate how UN/UNESCO leaders frame the future:

Table 6.

Excerpts illustrating the United Nations leadership’s framing of the future.

3.6. Education-Specific Framing: Education as the Infrastructure of Sustainable Futures

Education appears to be an important theme running across all speeches, though with varying degrees of emphasis. UNESCO considers classroom environments, universities, and teachers to be important spaces where justice, gender equity, democratic principles, and sustainable knowledge outcomes need to be fostered. UN stresses how education can empower societies to cope with technological, environmental, and other societal transitions. Throughout these selected speeches, education has been framed as transformative because it can shift mindsets and make societies more resilient through active citizenship. The selected excerpts presented in Table 7 illustrate how UN/UNESCO leaders frame sustainability:

Table 7.

Excerpts illustrating the United Nations leadership’s framing of education.

3.7. Synthesis of Findings

Throughout the speeches, the concepts of sustainability and inequality are presented not just as problems but also as phenomena culturally, structurally, and economically embedded, and not the result of individual failure but of society. UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay recognizes that gender inequality not only has roots in structural and cultural factors but also permeates society and sees education as the chief agent that can instill sustainability and dignity in the present and future generations of girls and women. Sustainability and inequity, as the UN chief noted, are structurally embedded problems.

The speeches portray education as a strategic and moral catalyst for systematic transformation and sustainable development. The role of education becomes much more explicit in the speeches of the United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres, during the Transforming Education Summit (TES) and COP28, where he sketches a global education crisis marked by inequalities, learning poverty, outdated curricula, and underinvestment. He reiterates the importance of commitment to teachers, curricula, digital connectivity, safe learning spaces, and the development of skills relevant to an uncertain future, to prepare the world for a new social contract and to facilitate a just transition in a decarbonizing world. Hilligje van’t Land, Secretary-General, IAU’s input focuses on the roles and responsibilities of educational institutions, along with governments and UNESCO, to maintain a focus on trust-building, relevance, and leadership in fast-changing technological and geopolitical landscapes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Framing Sustainability in UN and UNESCO Leadership Discourse

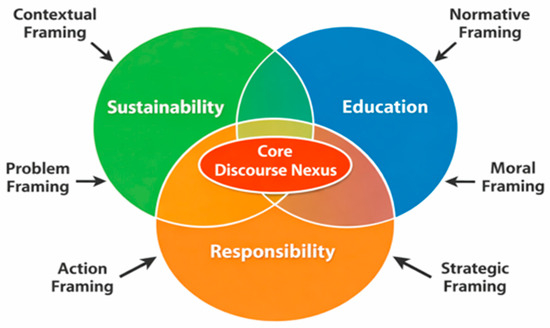

The analysis shows how senior-level officials at the UN and UNESCO, and institutional actors, frame the idea of sustainability in public dialogue, focusing on systemic challenges, collective but differentiated responsibility, morality, and the future-oriented prospects of transformation. These results directly fulfill the study’s objective of explaining the discursive construction of sustainability within the top strata of global governance. The analysis indicates that speeches are not merely conveying information about sustainability priorities but actively constructing narratives that shape how audiences interpret responsibility, agency, and desired futures. This aligns with literature on leadership for sustainability that highlights the integrative role of discourse in shaping strategic priorities and stakeholder engagement [33]. All these fit into the above-stated conceptual and theoretical frameworks on framing [32] and contribute to ongoing discussions around sustainability discourse and ESD [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Figure 3 visually synthesizes these interrelated framing dimensions, highlighting the conceptual linkages among sustainability, responsibility, and education in leadership discourse.

Figure 3.

Conceptual linkages among sustainability, education, and responsibility through pragmatic framing.

The speeches refer to sustainability as an interrelated framework of structural issues rather than as environmental or educational issues compartmentalized in any manner, reflecting how sustainability is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct that integrates environmental integrity, social equity, and economic well-being [33,34]. This is supported by the findings of the present study, which show that sustainability is represented as a crisis within a system rather than a concern relevant to specific areas. In line with the Road Map on ESD 2030 [4] and the ethical and value-driven dimension of sustainability [5,7,23], sustainability can be viewed as a relational construct grounded in obligations to people and planet.

The study extends existing research by demonstrating how global leadership discourse shapes the meaning-making processes surrounding ESD and sustainability at the international level [6,7]. The speeches, particularly in the UN and UNESCO, are powerful rhetorical tools [5,8]. They go beyond merely expressing the challenges of sustainability; instead, they contribute to the creation of collective storytelling about urgency, responsibility, and potential. The same applies to the theoretical suggestion that sustainability represents not merely an area of policy but itself an object of communication [32], because UNESCO’s Futures of Education highlight public discourse as essential for defining visions of desirable collective futures [24,30]. The speeches under analysis play a role in using metaphors, appeals to morality, appeals to institutional legitimacy, and future-oriented imaginaries to advocate political will. They offer examples of how global leaders use discourse to manage expectations and align global publics with sustainability concerns.

An analysis of the literature shows that the theme of sustainability has been framed comprehensively in UN and UNESCO terminology: as a justice-driven, future-shaping challenge that calls for systemic change, differentiated responsibility, and education. All these aspects align with the existing literature [6,7,21,23,24] and the UNESCO definition of ESD.

4.2. Negotiating Responsibility for Global Sustainability

Responsibility becomes an important discursive theme, with leaders engaging with both the origins and the entities involved in addressing those origins of sustainability problems. In accordance with research on responsibility framing [6,21,22], the discourse focuses on two areas of responsibility: causal responsibility (who contributed to current problems) and treatment responsibility (who should act now). This distinction serves as the foundation for the study’s aim to explain how global leaders grapple with accountability within the discourse on sustainability. While causal responsibility rests with structural or historical circumstances such as differences in development patterns [1], contributions of high-polluting countries, and global inequities, this style of discussion makes sure to distance itself from individualistic interpretations of human behavior and instead emphasizes that problems related to sustainability stem from collective actions rather than individual ones [41,42].

This framing is supported by the existing literature, which suggests that global institutions are generally more likely to take up systemic rather than individual responsibility in discourses on climate and sustainability [41,42,43,44,45,46]. The issue of attributing treatment responsibilities [45,46] is viewed as resting on several actors, each with unique yet interlinked spheres of responsibility. This confirms the study’s finding of shared but unequal responsibilities, with more responsibilities resting on developed countries and global institutions. In this way, the speeches construct a clear hierarchy of obligation, reinforcing global norms that link capacity, historical contribution, and moral duty.

4.3. The Central Role of Education and ESD

One of the most important findings emerging from this research is the recurring theme of education as a key enabler of the sustainability transition. This aligns with the findings of [3,4,23,29]. The Transforming Education Summit (TES) Report (2022) outlines several closely interwoven priorities, including building teachers’ capacity, reframing curricula and assessments, building digital literacy, integrating climate-related learning, and furthering inclusion and gender equity in education systems. While the COP28 Summit has thematic discussions on women’s participation in higher-education leadership, the ethics of new information and communications technology, and the importance of intercultural understanding, the discourse on climate at COP28 specifically focuses on building capacity for a just transition, which aligns with the existing literature on sustainability transitions [5].

Individually and collectively, these viewpoints support UNESCO’s vision of ESD as a transformative agent, as defined by [3,4,5]. These also align with other scholarly discourses on the role of education, wherein it is considered paramount to facilitate changes at the system level to support transitions to sustainability, largely due to its importance for values and ethics, along with collective capabilities [3,4,7,23,29]. These findings support the assertion that education serves as a multidimensional catalyst, influencing knowledge, skills, attitudes, and governance capabilities in the sustainability agenda [4,23,25].

These speeches verify the roadmap statement that sustainability means changing “mindsets, competencies, and institutional cultures” [3] (p. 8) to “realize [their] goals in and through education” [3] (p. 8) because it “is the most direct means of achieving the changes in mindsets, competencies, and institutional cultures” [3] (p. 8) required by sustainability. At the same time, these speeches demonstrate another important theme of the Commission on the Futures of Education:

“We need to rebuild trust in education as an engine of progress; support the ethical use of technology to strengthen our individual and collective humanity; and strengthen education so that it prepares our societies, our children, and our grandchildren for all manner of uncertain futures” [3] (p. 4).

In all these ways, education can help build trust, a critical foundation from which to advance further gains in the future [3,4,5]. It follows, therefore, that selected speeches support the role of education as both driving sustainable development and resulting from it, which aligns with [4,5].

5. Conclusions

5.1. Principal Findings

In this research, the framing of sustainability in five high-level speeches delivered within the United Nations and UNESCO institutional settings between 2022 and 2025 has been explored. Using the pragmatic framing approach, the analysis reveals that sustainability is framed as a systemic, multidimensional problem based in issues of inequality, climate, and justice; where the responsibility for the cause can be ascribed to global systemic issues rather than persons, but where responsibility regarding treatment can instead be framed as collective but differentiated, where greater responsibility lies with developed countries, global agencies, or education systems. Throughout all of these speeches, sustainability is portrayed as an ethical good that relates to justice, dignity, and solidarity. Education is depicted as a tool that enables sustainable futures, either through direct means, such as changes in the curriculum, or through indirect means, such as the acquisition of skills relevant to climate change or digital transformation. In conclusion, global leaders use public speech to articulate sustainability issues, especially to build public narratives around responsibility, ethical mission, and collective futures. These speeches can thus be considered discursive tools that articulate and frame expectations about the pivotal role of education in times of global crises

5.2. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this study is based on a small, purposively selected set of five leadership speeches. While this constrains claims of empirical representativeness, it enables a focused and theoretically informed examination of elite institutional discourse. Consistent with qualitative pragmatic framing research, the study prioritizes analytical depth and meaning-making processes over breadth.

Second, the analysis focuses on elite institutional discourse produced within the United Nations and UNESCO contexts. As such, the findings primarily reflect global organizational priorities and normative frameworks rather than the perspectives of local educational actors, practitioners, or community stakeholders operating within specific national or cultural settings. Similar qualitative research in educational governance shows that leadership discourse often frames sustainability commitments in ways that reflect institutional priorities and constraints [47,48,49].

Finally, in line with pragmatic framing theory, the study focuses on the construction of meaning and rhetorical function within leadership discourse. This emphasis limits insight into how these messages are interpreted, negotiated, or enacted in practice by audiences, policymakers, or educational practitioners. These interpretive insights resonate with studies that emphasize the role of leadership narratives in fostering transformational engagements with sustainability goals [50].

5.3. Implications

First, the ethical perspective in both UN and UNESCO speeches highlights the need for a curriculum that equips learners with knowledge of power relations and historical responsibilities related to sustainability. Second, the recurring theme of differentiated responsibilities in climate and development discussions suggests that ESD should engage more actively with the geopolitical dimensions of sustainability. ESD can help its audience understand how issues of responsibility, vulnerability, and capacity interact in different settings. Third, the speeches emphasize that education is an instrument of transformation rather than support. Teacher education programs need to embed sustainable thinking skills such as critical thinking, systemic thinking, digital literacy, climate literacy, and participatory pedagogy in all disciplinary majors, rather than confining them to environmental majors. Finally, empowering learners to decode the sustainability narratives disseminated by government and institutional communication helps fortify their ability to deal with competing messages and assess the validity of these claims.

5.4. Future Research

Looking ahead, there are several directions in which future studies can continue this work. One such line of inquiry would involve examining speeches at larger UN or UNESCO events and studying changes in the framing of sustainability in these settings. An interesting follow-up line of research would involve studying the influence such speeches have had on shaping educational policy or public knowledge, bringing both discourses and policy impacts under a single analytical framework. Further studies could involve other voices, such as students, teachers, or education communities, examining institutional framing alongside personal understandings of sustainability.

Author Contributions

F.M.T. conceptualized the study, led the research design, conducted the analysis, and drafted the original manuscript. N.A.M. contributed to the study design, data interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. M.I.T. supported the theoretical framework, contributed to the literature review, and reviewed the manuscript. K.Y.A. contributed to methodological refinement and provided substantive feedback on the manuscript. M.K.M. assisted with conceptual development, interpretation of findings, and manuscript review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval because it involves the analysis of publicly available documents and does not include human subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. The study uses publicly accessible speeches for which informed consent is not required.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this research are openly available and consist of public speeches delivered by United Nations and UNESCO officials. These materials are publicly accessible without restriction via the organizations’ official websites, as detailed below: Transcript 1. UNESCO Director-General. Address at the Samarkand Conference (2025). Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000396522 (accessed on 12 December 2025). Transcript 2. United Nations Secretary-General. Remarks to the High-Level Opening of COP27 (2022). Available online: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statements/2022-11-07/secretary-generals-remarks-high-level-opening-of-cop27-delivered-scroll-down-for-all-english-version (accessed on 12 December 2025). Transcript 3. United Nations Secretary-General. Remarks at the Opening of the High-Level Special Event on Climate Action. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/latest/announcements/un-secretary-generals-remarks-opening-high-level-special-event-climate-action (accessed on 12 December 2025). Transcript 4. United Nations Secretary-General. Opening Remarks at the Transforming Education Summit (2022). Available online: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statements/2022-09-19/secretary-generals-opening-remarks-the-transforming-education-summit-bilingual-delivered-follows-scroll-down-for-all-english-and-all-french-versions (accessed on 12 December 2025). Transcript 5. van’t Land, H. Address at the UNESCO General Conference (on behalf of the UNESCO Director-General); International Association of Universities: Paris, France, 2025. Available online: https://www.iau-aiu.net/Address-at-the-UNESCO-General-Conference (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Gemini (Google AI) to generate illustrative figures. The authors reviewed and edited the generated content, and they take full responsibility for the integrity of the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

| UN | United Nations |

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| TES | Transforming Education Summit (UN-led summit, 2022) |

| IAU | International Association of Universities |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Sustainability Framing in UN/UNESCO Leadership Discourse

Table A1.

Excerpts illustrating the UN/UNESCO leadership’s framing of sustainability.

Table A1.

Excerpts illustrating the UN/UNESCO leadership’s framing of sustainability.

| # | Excerpts | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “there are places where access to education no longer exists for women and girls.” “…women make up just a third of scientists worldwide, and only 10% of computer science graduates and 2% of job applicants in the quantum sector.” (UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay Samarkand (2025, p. 2) | The speech frames gender inequality as a systemic problem rooted in stereotypes, unequal access, and global disparities in science, technology, and education. |

| 2 | “We are in the fight of our lives. And we are losing. Greenhouse gas emissions keep growing. Global temperatures keep rising.” (p. 1) “The deadly impacts of climate change are here and now. Loss and damage can no longer be swept under the rug.” (pp. 2–3) (UNSG António Guterres, COP27, 2022) | The speech constructs climate change as an escalating, existential, and immediate crisis. It defines the problem in catastrophic, urgent, and global terms. |

| 3 | “Our planet is minutes to midnight for the 1.5 degree limit”. “There are still large gaps that need to be bridged.” (UNSG António Guterres Press Encounter, COP28, 2023) | The problem is framed as urgent, escalating, structural, and directly caused by fossil fuels. The system is nearing irreversible limits. |

| 4 | “Instead of being the great enabler, education is fast becoming a great divider”. “Some 70 percent of 10-year-olds in poor countries are unable to read a basic text”. “UNSG António Guterres (Keynote Speech at the Transforming Education Summit, 2022) | Education is framed as a systemic global crisis marked by inequity, inadequate learning, structural failures, and widening gaps. |

| 5 | “Universities face growing scrutiny. Questions about relevance, impact, and credibility are intensifying amid rapid technological advances and societal change”. “Higher education… must rebuild trust at a time when evidence shows its importance, yet support is uneven”. Hilligje van’t Land (on behalf of UNESCO DG) UNESCO General Conference (2025) | Higher education is framed as facing a credibility, relevance, and trust crisis intensified by rapid societal and technological change. |

Appendix A.2. Causal Responsibility Framing in UN/UNESCO Leadership Discourse

Table A2.

Excerpts illustrating causal responsibility framing.

Table A2.

Excerpts illustrating causal responsibility framing.

| # | Excerpts | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “…stereotypes that continue to fuel the gender gap in science and technology.” UNESCO DG Andrey Azoulay (Samarkand, 2025, p. 2) | Responsibility is placed on social norms, stereotypes, political regression, and structural inequities, not individuals. |

| 2 | “Human activity is the cause of the climate problem.” “Those who contributed least to the climate crisis are reaping the whirlwind sown by others.” UNSG António Guterres (2022) | Responsibility is placed on human systems, fossil fuel dependence, high-emitting nations, and geopolitical dynamics. |

| 3 | “The root cause of the climate crisis—fossil fuel production and consumption.” (UNSG António Guterres Press Encounter, COP28, 2023) | Causal responsibility is assigned particularly to the fossil fuel economy, historical emitters, and wealthier nations whose emissions have intensified global vulnerability. |

| 4 | “Education systems… are failing students and societies, by favoring rote learning and competition for grades”. “Curricula are outdated and narrow”. “The digital divide penalizes poor students.” UNSG António Guterres (Keynote Speech at the Transforming Education Summit, 2022) | Responsibility is placed on structural deficiencies, outdated systems, insufficient investment, the pandemic, and persistent inequalities. |

| 5 | “Growing scrutiny” and “intensifying questions” are tied to rapid technological advances and societal change.” “Transforming higher education” is necessary due to external expectations and internal capacity challenges.” Hilligje van’t Land (on behalf of UNESCO DG) UNESCO General Conference (2025) | Responsibility is attributed to external pressures, societal transformations, and inadequate investment in higher education systems. |

Appendix A.3. Treatment Responsibility Framing in UN/UNESCO Leadership Discourse

Table A3.

Excerpts illustrating treatment responsibility framing.

Table A3.

Excerpts illustrating treatment responsibility framing.

| # | Excerpts | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “This report also calls on us to uphold this commitment…” (p. 1) “We are advocating for their right to go to school… and working to facilitate community literacy classes and distance learning.” (p. 2) UNESCO DG Andrey Azoulay (Samarkand, 2025) | UNESCO, states, communities, and the international system share collective but differentiated responsibility to address gender inequality. |

| 2 | “Human action must be the solution” “All G20 countries must accelerate their transition now—in this decade. Developed countries must take the lead”. “We need a historic Pact between developed and emerging economies—a Climate Solidarity Pact.” UNSG António Guterres, COP 27, 2022) | Responsibility for action is shared but differentiated, with developed nations, financial institutions, governments, and fossil fuel companies assigned heavier obligations. |

| 3 | “We need all commitments made by developed countries on finance and adaptation to be met—fully and transparently”. “Doubling adaptation finance to $40 billion by 2025 must be an initial step.” (UNSG António Guterres Press Encounter, COP28, 2023) | The speech frames treatment responsibility as shared, but places greater obligations on developed nations, financial institutions, and high-emitting countries. |

| 4 | “Now is the time to transform education systems.” “We must protect the right to quality education for everyone, especially girls”. “We need to tackle the global shortage of teachers… raise their status… ensure decent working conditions.” UNSG António Guterres (Keynote Speech at the Transforming Education Summit, 2022) | Responsibility falls on governments, education systems, and global institutions to reform education, protect rights, support teachers, and address vulnerabilities. |

| 5 | “We urge governments to support [higher education] politically, financially, and culturally”. “Reflections are already taking place on how to reinforce the vital role of higher education… beyond 2030.” Hilligje van’t Land, Secretary-General, International Association of Universities (IAU) (on behalf of UNESCO DG) UNESCO General Conference (2025) | Treatment responsibility is shared by governments, universities, and international bodies (UNESCO and IAU) to invest, coordinate, and lead systemic improvement. |

Appendix A.4. Value Framing in UN/UNESCO Leadership Discourse

Table A4.

Excerpts illustrating value framing in leadership speeches.

Table A4.

Excerpts illustrating value framing in leadership speeches.

| # | Excerpts | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Instilling gender equality in our societies starts… with the youngest learners.” (p. 1) “It must be paired with a profound shift in mindset…” (p. 1) “What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.” (p. 3) UNESCO DG Audrey Azoulay (Samarkand, 2025) | Values invoked include justice, equality, solidarity, human rights, and moral responsibility. |

| 2 | “It is a moral imperative. It is a fundamental question of international solidarity, and climate justice.” (on loss and damage) “Humanity has a choice: cooperate or perish”. “Solidarity that respects all human rights… a safe space for environmental defenders”. (UNSG António Guterres, COP27, 2022) | Central values include justice, solidarity, human rights, shared humanity, and moral responsibility. |

| 3 | “Maximum ambition and maximum flexibility.” “Climate justice” as a central value. “A just, equitable and orderly energy transition for all”. “A framework without the means of implementation is like a car without wheels.” (UNSG António Guterres Press Encounter, COP28, 2023) | Values invoked include justice, equity, solidarity, ambition, fairness, and multilateral cooperation. |

| 4 | “Quality education must support the development of the individual learner throughout his or her life”. “Help us learn… our responsibilities to each other and to our planet”. UNSG António Guterres (Keynote Speech at the Transforming Education Summit, 2022) | The speech emphasizes equity, dignity, lifelong learning, inclusion, human rights, and global responsibility. |

| 5 | “Fostering philosophical dialogue… to shape a just, inclusive, and human-centred integration of AI.” “Comprehensive internationalization… is essential to foster intercultural dialogue, learning, and understanding.” Hilligje van’t Land, Secretary-General, International Association of Universities (IAU) (on behalf of UNESCO DG) UNESCO General Conference (2025) | Core values include justice, inclusivity, intercultural understanding, cooperation, and human-centered technological development. |

Appendix A.5. Futures-Oriented Framing in UN/UNESCO Leadership Discourse

Table A5.

Excerpts illustrating futures-oriented framing.

Table A5.

Excerpts illustrating futures-oriented framing.

| # | Excerpts | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “…young girls’ minds tend to be highly scientific—it is only once stereotypes take hold that they begin to turn away.” (p. 2) We know where we want to head—and we know how to get there”. (p. 3) UNESCO DG Andrey Azoulay (Samarkand, 2025) | The speech frames the future as transformable through mindset change, equitable opportunity, and sustained action. |

| 2 | “A window of opportunity remains open, but only a narrow shaft of light remains”. “The global climate fight will be won or lost in this crucial decade—on our watch”. “We know what to do and we have the financial and technological tools to get the job done. (UNSG António Guterres, COP27, 2022) | Future-oriented rhetoric emphasizes urgency, narrow opportunity, intergenerational responsibility, and the possibility of success through transformative action. |

| 3 | “Decarbonization will create millions of decent new jobs…” (positive future scenario) “Transformation won’t happen overnight” “Looking ahead, the next two years are vital.” “We must conclude COP28 with an ambitious outcome… to keep 1.5 alive”. (UNSG António Guterres Press Encounter, COP28, 2023) | The future is framed as narrow but still actionable, dependent on coordinated global action and structural transformation. |

| 4 | “A new vision for education in the 21st century is taking shape”. “It must develop students’ capacity to adapt to the rapidly changing world of work”. “It must help us learn to live and work together… and understand our responsibilities to our planet.” UNSG António Guterres (Keynote Speech at the Transforming Education Summit, 2022) | The future is framed as requiring adaptive, ethical, collaborative, and environmentally conscious education systems. |

| 5 | “Higher education is key to driving social progress and economic growth.” Hilligje van’t Land, Secretary-General, International Association of Universities (IAU) (on behalf of UNESCO DG) UNESCO General Conference (2025) | The future is framed around strengthened global partnerships, renewed trust, and higher education as a driver of post-2030 societal progress. |

Appendix A.6. Education-Specific Framing in UN/UNESCO Leadership Discourse

Table A6.

Excerpts illustrating education framing.

Table A6.

Excerpts illustrating education framing.

| # | Excerpts | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Instilling gender equality in our societies starts… in the classroom for even the youngest learners.” (p. 1) “…our mandate—through culture, through education, through science—can help those societies recover.” (p. 3) UNESCO DG Andrey Azoulay (Samarkand, 2025) | Education is framed as a starting point for equality, a tool for mindset transformation, human rights, and a vehicle for societal recovery and resilience |

| 2 | “What will we answer when Baby 8 billion is old enough to ask: What did you do for our world?” “We must rebuild trust… and ensure a safe space for environmental defenders and all actors in society to contribute.” “We need all hands-on deck for faster, bolder climate action.” (UNSG António Guterres, COP27, 2022) | Unlike UNESCO speeches, this text frames education not in formal schooling terms but as societal learning, public responsibility, and intergenerational transmission of values. |

| 3 | “Governments must also ensure support, training and social protection for those who may be negatively impacted.” “Ministers and negotiators must move beyond… entrenched positions” (UNSG António Guterres Press Encounter, COP28, 2023) | Education appears implicitly as the need to reskill workforces and support institutional learning within governments, enabling policy decisions that are grounded in scientific knowledge and responsive to climate realities. |

| 4 | “Quality education… must provide the foundations for learning… scientific, digital, social and emotional skills”. “Girls’ education is among the most important steps to deliver peace, security and sustainable development”. “Today’s teachers need to be facilitators… and receive continuous training and adequate salaries”. “Schools must become safe, healthy spaces…” UNSG António Guterres (Keynote Speech at the Transforming Education Summit, 2022) | Education is framed as the primary driver of equity, sustainability, and human development, positioning schools and teachers as catalysts for systemic transformation. |

| 5 | “Higher education… is key to driving social progress and economic growth”. “IAU’s initiatives align with and support UNESCO’s programme and priorities… fostering and strengthening higher education worldwide”. “We stress the importance of renewing trust in higher education… so that societies can build the knowledge and educate citizens to address global challenges.” Hilligje van’t Land, Secretary-General, International Association of Universities (IAU) (on behalf of UNESCO DG) UNESCO General Conference (2025) | Education, especially higher education, is framed as an essential global public good, central to building knowledge, citizenship, and societal capacity for sustainable futures. |

References

- Hariram, N.P.; Mekha, K.B.; Suganthan, V.; Sudhakar, K. Sustainalism: An integrated socio-economic-environmental model to address sustainable development and sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotosho, A.O. Afrocentric perspectives on UNESCO’s education for sustainable development framework: Implications for university leadership. In Qual. Assur. Educ.; 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education in a Post-COVID World: Nine Ideas for Public Action; International Commission on the Futures of Education: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Shulla, K.; Filho, W.L.; Lardjane, S.; Sommer, J.H.; Borgemeister, C. Sustainable development education in the context of the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Flowerdew, J.; Richardson, J.E. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J.; Benavot, A. Can we meet the sustainability challenges? The role of education and lifelong learning. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa’adi, N.; Abd Gapor, S.; Tamrulan, F.; Bohari, A.A.M. Towards a sustainable campus: A review of plans, policies, and guidelines on sustainability in Malaysian public higher education institutions. J. Des. Built Environ. 2025, 1–2. Available online: https://ijeas.um.edu.my/index.php/jdbe/article/view/64799 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Yu, B.; Guo, W.Y.; Fu, H. Sustainability in English language teaching: Strategies for empowering students to achieve the SDGs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, G. The BLK ‘21’ programme in Germany: A Gestaltungskompetenz-based model for education for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 12, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, W.; Martin, M.; Mischo, C.; Kotthoff, H.G.; Waltner, E.M. How can ESD be effectively implemented? An analysis of recommended methods and procedures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Castellanos, P.M.; Queiruga-Dios, A. Education for sustainable development (ESD): An example of curricular inclusion in environmental engineering in Colombia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, U.; Kusanagi, K.; Gougoulakis, P.; Matsuda, Y.; Kitamura, Y. A comparative study of curricula for education for sustainable development (ESD) in Sweden and Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, J.; Omrcen, E.; Weldemariam, K.; Hanning, A.; Lodin, J. Building learning pathways to enhance education for sustainable development (ESD), quality and relevance. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2025, 26, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P. Conceptual issues in framing theory: A systematic examination of a decade’s literature. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardèvol-Abreu, A. Framing theory in communication research: Origins, development and current situation in Spain. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2015, 70, 423–450. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, L.; Jörges, S.; Mahl, D.; Brüggemann, M. Framing as a bridging concept for climate change communication: A systematic review based on 25 years of literature. Commun. Res. 2024, 51, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikström, S.; Mervaala, E.; Kangas, H.-L.; Lyytimäki, J. Framing climate futures: Media representations of climate and energy policies in Finnish Broadcasting Company news. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2023, 20, 2178464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huang, J. Framing responsibilities for climate change in Chinese and American newspapers: A corpus-assisted discourse study. Journalism 2024, 25, 1792–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Tsai, J.Y.; Mattis, K.; Konieczna, M.; Dunwoody, S. Attribution of responsibility in a cross-national study of TV news coverage of the 2009 UN climate change conference. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2014, 58, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbedahin, A.V. Sustainable development, education for sustainable development, and the 2030 Agenda: Emergence, efficacy, eminence, and future. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, S. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty, J.; Liddy, M. Impact of development education and ESD interventions. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2018, 10, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- MbAK, A. The need for a new definition of sustainability. J. Indones. Econ. Bus. 2013, 28, 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.E.; Mascarenhas, A.; Bain, J.; Straus, S.E. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggerio, C.A. Sustainability and sustainable development: A review of principles and definitions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.K.; Siragusa, L.; Guttorm, H. Introduction: Toward more inclusive definitions of sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 43, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousell, D.; Sinclair, M.P. Desiring-futures in education policy: Assemblage theory, artificial intelligence, and UNESCO’s futures of education. Educ. Rev. 2025, 77, 1754–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Verschueren, J. Introduction: The pragmatic perspective. In Key Notions for Pragmatics; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boeske, J. Leadership towards Sustainability: A Review of Sustainable, Sustainability, and Environmental Leadership. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H.; Meijers, F. Education for sustainable development: Exploring theoretical and practical challenges. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, L.W.; Egel, E. Global leadership for sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, J.; Hinder, B.; Rafaty, R.; Patt, A.; Grubb, M. Three decades of climate mitigation policy: What has it delivered? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2023, 48, 615–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Gupta, J.; Lenton, T.M.; Qin, D.; Lade, S.J.; Abrams, J.F.; Jacobson, L.; Rocha, J.C.; Zimm, C.; Bai, X.; et al. Identifying a safe and just corridor for people and the planet. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala-Uddin, M. Sustainable discourse: A critical analysis of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Asia Pac. Media Educ. 2019, 29, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawden, R. Sustainability as emergence: The need for engaged discourse. In Higher Education and the Challenge of Sustainability; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Iliško, D.; Heasly, B. Sustainable research agenda of the International Journal of Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education. In An Agenda for Sustainable Development Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 421–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.S.; Feldman, L. The influence of climate change efficacy messages and efficacy beliefs on intended political participation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ries, L.; Beckmann, M.; Wehnert, P. Sustainable smart product–service systems: A causal logic framework for impact design. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 93, 667–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, M.; Hertz, T.; Mancilla García, M.; Banitz, T.; Grimm, N.; Johansson, L.-G.; Lindkvist, E.; Martínez-Peña, R.; Radosavljevic, S.; Wennberg, K. Navigating causal reasoning in sustainability science. Ambio 2024, 53, 1618–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, G. Causality and responsibility. Cardozo Law Rev. 2000, 22, 1811. [Google Scholar]

- Brulle, R.J.; Carmichael, J.; Jenkins, J.C. Shifting public opinion on climate change: An empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the United States, 2002–2010. Clim. Change 2012, 114, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Citaristi, I. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization—UNESCO. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2022; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M.; Mulà, I. Current practices and future pathways towards competencies in education for sustainable development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Boechat, A.C. How Sustainable Leadership Can Leverage Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A.H.; Pajuelo, M.L.; Almaghaireh, I.; Chaaban, K.; Homsi, I.; Elmassri, M. Fostering Sustainability Leadership Through SDG 13 Integration in Business Curricula. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.