Abstract

Effective anomaly detection in vehicle trajectories is crucial for developing sustainable and safe urban transportation systems. However, current research faces three main challenges including scarce anomaly data, inadequate spatial feature extraction in complex road networks, and limited capability in identifying complex behaviors. To address these issues, this paper proposes a Multi-scale Temporal and Road Network Interaction Anomaly Detection model (MTRI). Our framework leverages a Contrastive Learning-based Conditional Diffusion Model (CL-CD) to generate synthetic anomalous trajectories across diverse scenarios. It then employs an Urban road Network Interaction Modeling model (UNIM) to capture the profound interactions between trajectories and the road network. Finally, a Long-Short Temporal Anomaly Detection model (LSTAD) is designed to learn multi-scale temporal features for detecting sophisticated anomalies. Extensive experiments on real-world datasets from various urban scenarios demonstrate the superiority of our approach, which achieves high accuracy and adaptability (AUC-ROC > 0.85). This work contributes to sustainable urban mobility by providing a reliable solution for enhancing road safety through proactive anomaly detection.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

The widespread adoption of mobile devices and sensor technologies has led to a massive increase in the volume and velocity of trajectory data generation [1]. As a pivotal technology in intelligent transportation systems, trajectory mining can uncover traffic flow patterns, optimize resource allocation, and provide critical support for traffic management and decision-making [2,3]. It has found applications across various fields such as traffic monitoring, urban planning, and public safety. Anomalous vehicle trajectories often indicate irregular driving behaviors, which are closely associated with traffic accidents, route deviations (detours), or fraudulent activities. Consequently, the timely and accurate identification of anomalous trajectories is crucial for mitigating traffic risks and ensuring transportation safety [4,5]. This is especially critical for the safety of vulnerable road users, such as pedestrians and cyclists, who lack physical protection. Trajectory anomalies that signify aggressive or irregular driving behaviors directly elevate collision risks for these individuals. Therefore, accurately identifying such risky vehicle trajectories is a key step toward building safer and more equitable urban transportation systems [6].

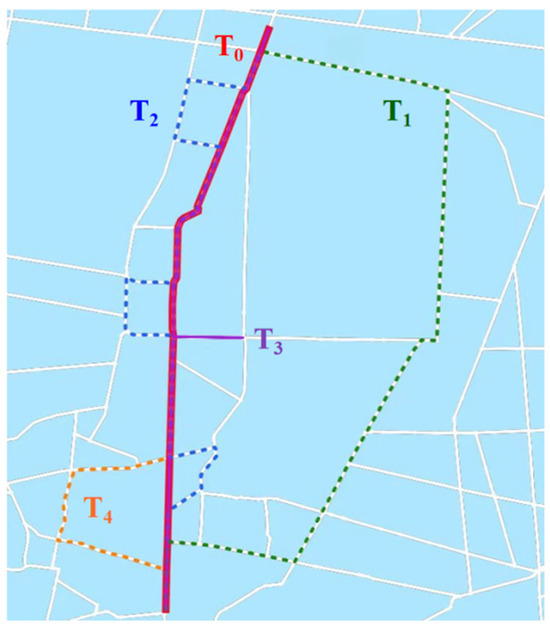

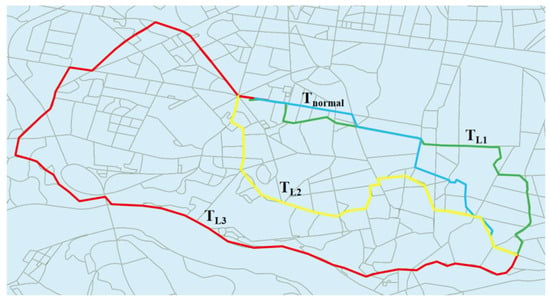

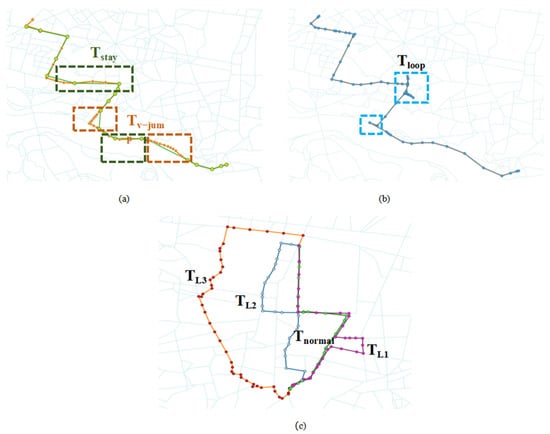

This paper categorizes anomalous trajectories into several typical behaviors, including detours, looping, prolonged low-speed driving, and sudden acceleration/deceleration [7,8]. These categories are illustrated in our original schematic (Figure 1), which visualizes a set of origin destination (OD) trajectory groups extracted from our dataset.

Figure 1.

Schematic of anomalous trajectories. The red solid line () denotes the normal route. Anomalous trajectories include: long-range detour (green dashed line, ), multiple micro-detours (blue dashed line, ), looping behavior (purple line, ), and local detour (orange dashed line, ).

In Figure 1, the red primary path () represents the normal route, serving as a baseline. The green dashed trajectory () depicts a “long-range detour,” where the vehicle significantly deviates from the normal path. The blue dashed trajectory () shows “multiple micro-detours,” characterized by frequent, short-distance deviations. The purple trajectory () indicates “looping behavior,” where the vehicle circulates repeatedly within a confined area. The orange dashed trajectory () represents a “local detour,” involving a minor deviation over a short segment. Other critical anomalies, such as extended low-speed driving and sudden speed changes, are not visually depicted but are equally considered in our detection framework. These defined anomalous behaviors provide a foundation for our detection task.

1.2. Literature Review

Following the context established above, a systematic examination of existing methodologies is essential to pinpoint the precise limitations motivating this work. This review is structured around the three pivotal challenges confronting trajectory anomaly detection: (1) data scarcity and generation, (2) modeling of spatial interactions with complex road networks, and (3) capturing multi-scale temporal patterns. We synthesize prior work in these domains to clarify the current state and the persistent gaps.

1.2.1. Review of Anomalous Trajectory Generation Methods

In trajectory anomaly detection, anomalous samples are generally scarce and unevenly distributed, which limits the training and generalization performance of deep models. To alleviate the data insufficiency problem, researchers have begun to focus on trajectory generation, aiming to enhance model robustness and detection performance by constructing high-quality synthetic anomalous samples. Research in this area has evolved through stages of rule-based models, deep generative models, and diffusion probabilistic models.

- (1)

- Rule-Based and Statistical Models Stage

Early methods were often based on motion rules or statistical distributions, generating anomalous samples by adding perturbations or noise to normal trajectories. While such methods are simple in structure and offer strong interpretability, they struggle to capture the high-dimensional nonlinear characteristics of traffic behavior. The generated samples exhibit shortcomings in both spatio-temporal consistency and diversity [9,10].

- (2)

- Deep Generative Models Stage

With the introduction of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [11,12,13], deep generative models became the primary means for trajectory generation. Real trajectory data is often limited by privacy protection, undersampling, and cross-regional transfer difficulties [14], making it inadequate for fully reflecting the diversity of real-world scenarios. To address this, researchers utilized deep generative models to synthesize high-quality trajectories that better capture complex trajectory distributions. GANs learn trajectory distributions through adversarial training and can generate representative anomalous patterns; for instance, Privacy-Aware Trajectory Generation Model (TrajGAN) and Privacy-Aware Trajectory Generation Model with Differential Privacy (DP-TrajGAN) perform well in privacy protection and pattern transfer [12,15]. However, they suffer from issues like mode collapse and structural distortion, making it difficult to maintain the geographic plausibility of trajectories. VAEs [16] model trajectory distributions using latent variables, resulting in better overall coherence of samples, but they struggle to represent abrupt behavioral changes. Some studies map trajectories into grid or image formats for easier training [17,18,19], but this conversion loses topological semantics and spatial continuity.

- (3)

- Diffusion Models and Conditional Diffusion Models Stage

Recently, Diffusion Probabilistic Models have demonstrated outstanding performance in high-fidelity data generation and have been introduced into the trajectory generation field. Spatial-temporal Diffusion Probabilistic Model for Trajectory Generation (DiffTraj) [13] learns trajectory distributions through a diffusion-denoising process, achieving fine-grained trajectory synthesis. However, existing research predominantly focuses on single-type trajectories and finds it difficult to balance controllability, realism, and generalizability in anomalous sample generation. The generation process lacks control over anomaly types, road network topology, and environmental constraints. Furthermore, the generated samples often lack support from real traffic semantics, limiting their cross-domain transferability. Zhu et al. [20] focused on the robustness of Graph Convolutional Networks in traffic prediction, evaluating model resistance through diffusion attacks. To enhance controllability and diversity, researchers have proposed conditional diffusion models. For example, Controllable trajectory generation with topology-constrained diffusion model (ControlTraj) [21] embeds road network topology into the diffusion process, enabling geographically constrained controllable generation, but it remains primarily oriented towards normal trajectories and fails to effectively model the complex patterns of anomalous behaviors.

Thus, while significant progress has been made in general trajectory generation, a dedicated and effective paradigm for generating anomalous trajectories remains notably underdeveloped. Existing methods, whether rule-based, deep generative, or diffusion-based, predominantly focus on synthesizing normal trajectories or employ simplistic perturbations to simulate anomalies. They lack a dedicated framework to controllably generate diverse, semantically rich, and geographically plausible anomalous patterns that mirror the complexity of real-world irregular behaviors. This specific gap in targeted anomalous trajectory generation critically limits the availability of high-quality training data, which in turn constrains the advancement of robust anomaly detection models.

1.2.2. Review of Spatial Feature Extraction Methods

Anomalous trajectories often exhibit complex patterns, primarily due to the high dimensionality, sparsity, and rarity of anomalies in trajectory datasets, coupled with the inherent difficulty in capturing hidden relationships between nodes during spatial modeling [22,23]. Consequently, exploring and capturing these complex spatial relationships is crucial for effective anomaly detection. Early research widely adopted Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to extract spatial features from trajectories. For instance, the RioBus data system proposed by Bessa et al. [24] utilizes CNNs to analyze local variations, while DeepAnT (Novel Deep Learning-based Anomaly Detection Approach), introduced by Munir et al. [25], demonstrates the potential of CNNs in unsupervised anomaly detection. Although CNNs demonstrate proficiency in capturing local spatial features, their capability to handle non-Euclidean data (e.g., graph structures) and model long-range dependencies remains limited.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have demonstrated significant advantages in modeling the spatio-temporal dependencies of trajectory data. Typical models include the Graph Attention Network (GAT), Graph Auto-Encoder (GAE), and Graph Convolutional Network (GCN). Among them, GAT adaptively adjusts the weights between nodes via an attention mechanism to capture complex spatial relationships. Zhao et al. [26] verified the effectiveness of GAT in multivariate time series anomaly detection. GAEs learn latent features of graphs through an auto-encoder structure for anomaly detection, as seen in models like DeepSphere (Deep into Hypersphere) [27]; however, their high computational complexity limits real-time application. GCNs exhibit good performance in spatial feature extraction through node embedding and graph structure reconstruction [28]. Furthermore, Spatial Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks for Skeleton-based Action Recognition (StrGNN) [29] combines GCN with Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) to achieve joint modeling of spatio-temporal features, yielding positive results in dynamic graph anomaly detection. Nevertheless, these methods primarily focus on the internal structure of trajectories and insufficiently consider the spatial dependency between trajectories and the road network environment.

In recent years, researchers have begun to focus on the role of road network topology in trajectory anomaly detection. Road network features can effectively reflect the spatial boundaries and semantic constraints of vehicle behavior, such as road connectivity, intersection structure, and traffic regulations. The RL4OASD (Online anomalous sub-trajectory detection on road networks with deep reinforcement learning) model proposed by Zhang et al. [30] represents the road network as a directed graph, learns road segment features via RSRNet (Road Segment Representation Network), and combines them with ASDNet (Anomalous Subtrajectory Detection Network) to achieve online anomalous sub-trajectory detection, demonstrating excellent performance in both accuracy and real-time processing. Ding et al. [31] proposed the MST-GAT (Multimodal Spatial-temporal Graph Attention Network for Time Series Anomaly Detection) method for multi-modal spatio-temporal modeling, which utilizes a multi-modal graph attention network and a temporal convolutional network to capture spatio-temporal correlations in multi-modal time series.

However, existing road network-based detection methods still have limitations. First, they often remain at the road-segment level of modeling and fail to adequately characterize the hierarchical topology of the road network. Second, the lack of joint modeling of upstream-downstream dependencies and interactions between adjacent roads makes it difficult to reflect the spatial propagation characteristics of traffic flow. Simultaneously, the trade-off between feature extraction accuracy and computational efficiency continues to constrain their real-time application. Collectively, these limitations indicate that current approaches lack a comprehensive mechanism to capture the multi-scale and interactive nature of trajectory-road network dynamics. This deficiency hinders the accurate disambiguation between environmentally induced deviations and genuine anomalous behaviors, representing a key gap in spatial modeling for robust anomaly detection.

1.2.3. Review of Temporal Feature Extraction Methods

Trajectory data exhibits significant temporal dependencies, with anomalies often manifesting as abrupt changes in speed, direction, or behavioral patterns. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants are widely used to model such sequential dependencies, such as in Natural Language Processing (NLP) [32], speech recognition [33], and image captioning [34]. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [35] and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) [36], which mitigate the vanishing gradient problem through gating mechanisms, have been applied to traffic prediction and trajectory analysis [37]. Malhotra et al. [38,39] utilized multi-layer LSTM to capture long-term dependencies, while ATD-RNN (Anomalous trajectory detection using recurrent neural network) [40] employed bidirectional LSTM to improve detection accuracy. However, traditional RNNs still face limitations in modeling long sequences and coupling spatial features. To address this, Cheng et al. [41] proposed a Spatial-Temporal RNN, and MSCRED [42] model combined CNNs with LSTM for joint spatio-temporal feature modeling. The Sequence to Sequence (Seq2Seq) model [43] enhances the modeling capability for variable-length trajectories through its encoderdecoder structure, albeit with high computational complexity.

With the development of the self-attention mechanism, Transformer [44] has demonstrated stronger capabilities in learning global dependencies within long sequences. Wang et al. [45] combined Transformer with Variational Auto-encoders (VAE) to enhance generation and detection performance, but its complex structure limits real-time applicability. Auto-encoders (AE) and VAEs have also been used for temporal feature extraction [46,47]. Meanwhile, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) improve the quality of anomalous sample generation through adversarial training; for instance, both Time series anomaly detection with generative adversarial networks (TAnoGAN) [48] and Multivariate anomaly detection for time series data with generative adversarial networks (MAD-GAN) [49] perform well in multivariate time series anomaly detection.

Despite progress in temporal modeling, prevailing methods are often constrained by a trilemma between granularity, flexibility, and efficiency. They may capture precise short-term anomalies or long-term trends, but struggle to adaptively model both. Furthermore, dependence on fixed time windows can disperse anomalous signatures, while complex architectures incur high computational costs, limiting real-time applicability.

In summary, while significant progress has been made in data generation, spatial modeling, and temporal analysis for trajectory anomaly detection, these advancements often remain siloed. Current methods struggle to simultaneously ensure data authenticity, capture complex road network semantics, and model multi-scale temporal patterns within a unified framework. This fragmentation constitutes a primary bottleneck for robustness in real-world applications.

1.3. Research Gaps

The compartmentalized progress identified in Section 1.2 leaves critical, interconnected research gaps unresolved. Synthesizing the limitations discussed, we formally define the following three core challenges that this study aims to address:

- (1)

- Data Scarcity and Ineffective Generation.

The scarcity of anomalous samples and the difficulty of data labeling fundamentally hinder the performance of supervised learning approaches. Consequently, existing semi-supervised or unsupervised methods often exhibit reduced accuracy when dealing with complex anomalies. To mitigate data insufficiency, some studies have employed data augmentation techniques to generate anomalous trajectories. However, the generated samples often lack the complexity and diversity of real-world anomalies, thus limiting model generalization.

- (2)

- Inadequate Modeling of Trajectory-Road Network Interactions.

Numerous trajectory anomaly detection methods have been proposed, such as the TRAjectory Outlier Detection (TRAOD) algorithm by Lee et al. [50], the Isolation-Based Anomalous Trajectory (iBAT) algorithm by Zhang et al. [51], and Isolation-based Online Anomalous Trajectory Detection (iBOAT) algorithm by Chen et al. [52]. While these algorithms perform well in specific scenarios, their effectiveness is often limited in complex, dynamic urban road networks [53]. The complexity of urban road networks and dynamic traffic states makes accurately modeling the nuanced interactions between trajectories and their environment a major challenge. Although some studies have considered trajectory-road network interactions, prevailing methodologies often fail to fully incorporate road network information. This inadequacy makes it difficult to distinguish between trajectory deviations caused by environmental factors (e.g., traffic congestion) and genuine anomalous behaviors, ultimately affecting the reliability of practical applications. A more sophisticated model is required to capture these complex spatial-environmental interdependencies.

- (3)

- Insensitivity to Multi-Scale Temporal Anomalies.

Most existing methods focus on global anomalies while overlooking local anomalies [40,54]. Furthermore, many current methods fail to precisely identify local anomalies [47,55]. Strategies based on fixed time windows can fragment anomalous segments across multiple sub-trajectories, leading to diminished detection accuracy or the omission of complex features [50,56]. There is a notable lack of models capable of simultaneously capturing both short-term behavioral spikes and long-term evolutionary trends within trajectories, which is crucial for the precise detection and localization of fine-grained anomalies.

In summary, the fragmentation of progress across data generation, spatial modeling, and temporal analysis has left the aforementioned three gaps unresolved. Addressing these interconnected challenges is crucial for advancing robust trajectory anomaly detection.

1.4. Proposed Framework and Contributions

To address these challenges, we propose a Multi-scale Temporal model based on Road network-environment Interactions (MTRI) for vehicle trajectory anomaly detection. Our framework consists of three key components. First, to tackle data scarcity, we employ a Conditional Contrastive Diffusion Model (CL-CD) to generate diverse and realistic anomalous trajectories, effectively expanding the training set and bridging the gap between synthetic and real data. Second, to model the complex interactions in urban environments, we introduce an Urban road Network Interaction Modeling (UNIM) module. By integrating features of the road network environment, UNIM can accurately distinguish between deviations caused by traffic conditions and genuine anomalies, thereby improving matching and detection accuracy. Finally, we propose a Long-Short Temporal Anomaly Detection model (LSTAD) that incorporates multi-scale temporal features and a sliding window mechanism. This model effectively captures both long- and short-term temporal dependencies, enhancing the detection capability for complex anomalies.

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

- CL-CD is proposed to generate trajectory data with varying degrees and categories of anomalies. By using a cross-attention mechanism with normal and abnormal trajectories as dual conditions, the CL-CD model effectively diversifies abnormal samples while preserving complex behavioral patterns.

- UNIM is introduced to capture the deep interactions between trajectories and factors such as road networks and traffic flow. UNIM comprises an Edge-Augmented Heterogeneous Attention Network (EA-HAN) and a Time-Decoupled GCN-GAT module (TDC-GCN-GAT) for spatial feature extraction, which improve trajectory matching accuracy and reduces false positives and negatives.

- LSTAD is presented to capture both short-term spikes and long-term trends. The model integrates a Bidirectional Attention Residual Depth-Separable Convolution Module (BARDSC) and a Dual-Stage Temporal Network (DSTN), enhancing temporal dependency modeling and improving the detection of local anomalies.

- A hybrid framework is designed that combines an offline model for learning road network features with an online model for real-time detection, thereby balancing accuracy with computational efficiency.

The primary aim of this work is to propose a novel, integrated framework (MTRI) that advances vehicle trajectory anomaly detection by simultaneously addressing data scarcity, complex spatial interactions, and multi-scale temporal modeling, thereby enhancing reliability for sustainable transportation safety.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 defines the problem and details the proposed MTRI model, including the experimental setup and design. Section 3 presents and analyzes the experimental results, including comparative experiments, ablation studies, and a case study. Finally, Section 4 concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Definition

This paper focuses on detecting anomalous sub-trajectories for vehicles traveling between the same origin O and destination D. First, a sliding window technique is applied to partition each complete trajectory into multiple sub-trajectories. These sub-trajectories are then segmented based on the real urban road network. Through map matching, GPS points within each sub-trajectory are aligned to their corresponding road segments. Finally, anomalies are identified by measuring the deviation between each sub-trajectory and its adjacent counterparts.

Formally, the trajectory data is defined as a database , where each trajectory represents a sequence of GPS points from O to D, denoted as . Each point in trajectory is defined by its longitude, latitude, and timestamp, i.e., .

We employ a map matching algorithm to project all historical trajectories T onto the physical road network. Consequently, each GPS point p is mapped to a specific road segment v. For instance, after map matching, a trajectory can be represented as an ordered sequence of road segments , where denotes the -th road segment traversed by the i-th trajectory.

2.2. Framework Overview of MTRI

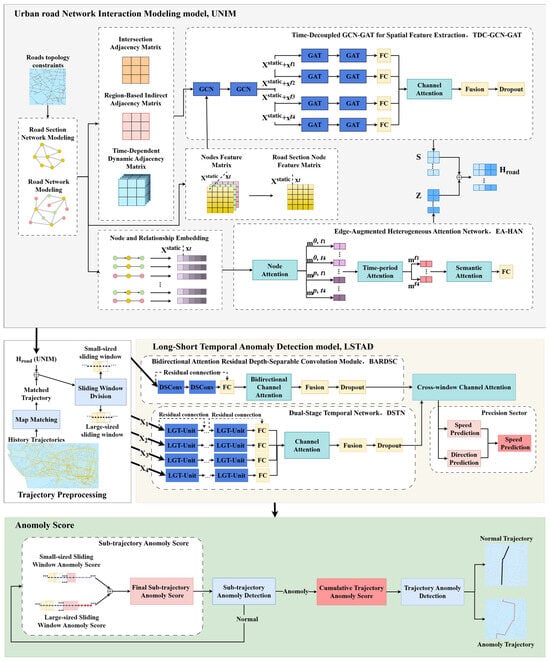

The overall architecture of our proposed trajectory anomaly detection framework, MTRI, is depicted in Figure 2. To enhance clarity, the key mathematical symbols and abbreviations appearing in Figure 2 are summarized in Table 1 below.

Figure 2.

Framework overview of Multi-scale Temporal model based on Road network-environment Interactions (MTRI). The colored dots represent different node types in the urban road network: red for intersection nodes, yellow for road segment nodes, and green for zone nodes. The symbol ⊕ represents the concatenation operation.

Table 1.

Nomenclature of key symbols and modules in the MTRI framework (Figure 2).

The framework, which comprises four dedicated modules, operates as follows:

CL-CD: This module augments the training data by generating trajectory samples with varying degrees of anomaly severity. It enhances the model’s generalization capability under conditions of anomalous data scarcity, thereby improving overall detection performance.

UNIM: Operating as an offline component, UNIM captures the high-order interactions between trajectories and environmental factors (e.g., road network structures and traffic flows). It integrates EA-HAN with TDC-GCN-GAT to facilitate more accurate trajectory matching and anomaly detection.

LSTAD: Designed as an end-to-end online model, LSTAD extracts multi-scale temporal features and models complex temporal dependencies. It combines BARDSC with DSTN to achieve efficient and real-time anomaly detection.

Anomaly Scoring Module: Based on a sliding window mechanism, this module calculates anomaly scores for individual sub-trajectories. These scores are then aggregated with historical window information to assess the anomaly level of the entire trajectory.

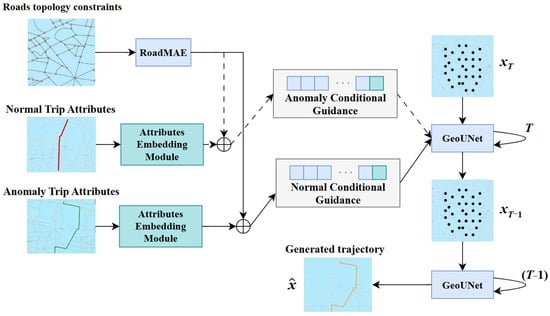

2.3. CL-CD

To address the scarcity of anomalous trajectory samples and the lack of realism in generated data, we propose CL-CD model. Figure 3 depicts the reverse denoising process: starting from pure Gaussian noise , the model performs T iterative denoising steps (from step T to T − 1 as shown) through the GeoUNet module. This process is guided by the dual conditional embeddings (derived from normal and anomalous trip attributes and road topology) to ultimately generate the target anomalous trajectory, denoted as . This model is designed to generate anomalous trajectory data that is both diverse and geographically plausible, thereby providing high-quality augmented samples for downstream detection models.

Figure 3.

Structure of Conditional Contrastive Diffusion Model (CL-CD). The red and green lines denote the normal and anomaly trips, respectively, while the orange line represents the generated trajectory. The blue and teal blocks indicate the outputs of the RoadMAE module and the Attributes Embedding Module, respectively. The black dots represent the intermediate diffusion states in the GeoUNet denoising process. The symbol ⊕ represents the concatenation operation.

Our approach builds upon the topology-constrained diffusion model architecture of ControlTraj [21] but introduces critical enhancements. While ControlTraj primarily utilizes road network topology as a single condition for generating trajectories, focusing on normal trajectory generation, we introduce a dual-condition contrastive generation mechanism. This key innovation tailors the model for the task of anomalous trajectory generation, enabling it to produce diverse trajectories that faithfully reflect real-world anomalous patterns.

2.3.1. Embedding Module

- (1)

- Attributes Embedding

We extract attributes for each trajectory point, including departure time, travel time, total distance, average speed, and direction angle. These attributes are mapped to a fixed-dimensional vector representation using a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). For a trajectory , the attribute embeddings of all its points are concatenated to form a holistic attribute vector , which serves as part of the conditional information.

- (2)

- Road Segment Embedding

We employ a pre-trained RoadMAE model to encode the road segment corresponding to each trajectory point. For a given trajectory, its sequence of road segments is fed into the RoadMAE model, yielding a sequence of road segment embeddings . Since different trajectories contain a variable number n of points, we apply a linear interpolation resampling method to standardize to a fixed length L, resulting in . This is subsequently flattened into a one-dimensional vector .

2.3.2. Anomalous Trajectory Generation Module

- (1)

- Contrastive Geo-Denoising U-Net Architecture (C-UNet)

We design C-UNet as the core noise predictor for our conditional diffusion model. The key innovation of this architecture is its ability to simultaneously process and fuse conditional information from both normal and anomalous trajectories, thereby guiding the model to generate trajectories with anomalous characteristics. The noise prediction function of this C-UNet is defined as:

where is the noisy trajectory at step t, () is the conditional embedding of the anomalous (or normal) trajectory, formed by concatenating the attribute embedding and the road segment embedding of the anomalous (or normal) trajectory.

Building upon the standard encoderdecoder structure of a U-Net, our C-UNet integrates a Dual-Path Cross-Attention mechanism and a Conditional Weighted Fusion module into each sampling block.

Dual-Path Cross-Attention Mechanism: For the input features, we compute two independent cross-attention paths in parallel. One path interacts the features with the anomalous condition embedding , aiming to capture the anomalous patterns that should be imitated. The other path interacts the features with the normal condition embedding , serving to identify the normal patterns that should be avoided.

Conditional Weighted Fusion: To achieve contrastive control over the generated trajectories, we perform a weighted fusion of the attention outputs from the two paths. This guides the model to focus more on anomalous features while deviating from normal patterns. The fused feature at layer l is computed as:

where represents the features at layer l, and γ is a weighting coefficient used to balance the contribution of abnormal and normal conditions in feature fusion and is set to 0.6 by validation set adjustment. The Negate function is applied to implement a “repulsion” effect from the normal condition.

Finally, the output feature of the block is obtained via a residual connection between the fused feature and the original self-attention feature:

By repeating this process across multiple scales throughout the U-Net, our model consistently receives contrasting signals from both normal and anomalous trajectories at every denoising step. This enables the final generation of trajectory data that maintains geographical plausibility while exhibiting distinct anomalous characteristics.

- (2)

- Conditional Diffusion Model

The conditional diffusion model generates data through a forward noise addition process and a reverse conditional denoising process. The innovation of our framework lies in the reverse process, which is jointly guided by the normal trajectory condition and the anomalous trajectory condition , enabling contrastive control over the generated trajectories. Following the works of [57,58], the forward process is defined as:

where is the weight of noise. Using reparameterization, can be sampled directly from , , where , and . When T is sufficiently large, is guaranteed to follow an isotropic Gaussian distribution.

The reverse process starts from noise and reconstructs the data distribution through iterative denoising. This process is regulated by the dual conditions and , and is defined as:

where the mean at each step is derived from the noise predicted by our dual-condition C-UNet, parameterized according to the work of Ho et al. [59]. The variance is set to a fixed value related to the noise schedule.

- (3)

- Loss Function

The model is trained under the joint guidance of a diffusion loss and a contrastive loss.

The diffusion loss minimizes the KL divergence between the model’s generated distribution and the real data distribution, ensuring the generated trajectories conform to the true data manifold. The contrastive loss explicitly constrains the generated trajectory to be closer to a real anomalous trajectory and farther from a real normal trajectory . This is measured using the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) metric [60]. The total loss is the weighted sum of the two components:

where is the true noise added during the forward process, and is the noise estimated by the model based on the noisy trajectory , the step t, and the dual conditions. , and is the alignment path. is a hyper-parameter that balances the weight of the two loss terms, which is determined by grid search, and the optimal value is 0.5.

Through this mechanism, at each reverse denoising step, the model receives contrasting guidance from both normal and anomalous trajectories, thereby progressively generating trajectories from random noise that are both realistic yet exhibit specific anomalous patterns. The optimization of this process is driven by our proposed contrastive loss function (Equation (8)), ensuring semantic controllability over the generated trajectories.

2.4. UNIM

To deeply model the dynamic interactions between trajectories and the complex urban road network, we propose the UNIM model. This UNIM innovatively integrates EA-HAN and TDC-GCN-GAT. This integration enables UNIM to model the spatio-temporal characteristics of urban traffic flows offline, capturing both global traffic trends and local interactions between road segments, thereby effectively enhancing trajectory anomaly detection capability.

2.4.1. EA-HAN

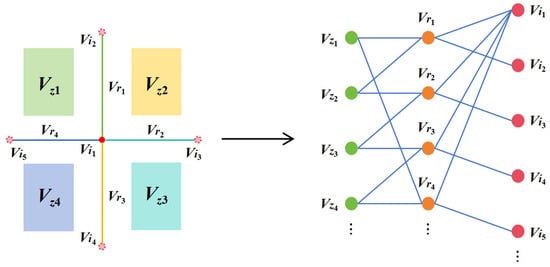

Building upon [61], we define a dynamic heterogeneous traffic network graph , as shown in Figure 4. It comprises three node types: road segment nodes , intersection nodes , and zone nodes . Each node type possesses its own set of static features .

Figure 4.

Schematic of the heterogeneous graph definition.

To capture high-order semantic relationships between nodes, we define three meta-paths:

- The undirected meta-path : “road segment–zone–road segment”.

- The undirected meta-path : “road segment–intersection–road segment”.

- The directed meta-path : “inbound road segment–intersection–outbound road segment”.

Based on a meta-path , the neighborhood of node i during time period t is defined as the set of all nodes j connected to i via an instance of this meta-path. Specifically, for the directed meta-path , its instance takes the form , where is the mediating intersection node.

To simulate traffic dynamics, the edges E in the graph are assigned timestamps. We define four typical time periods , representing morning peak, noon peak, evening peak, and off-peak hours, respectively, to characterize the network connectivity states under different temporal contexts.

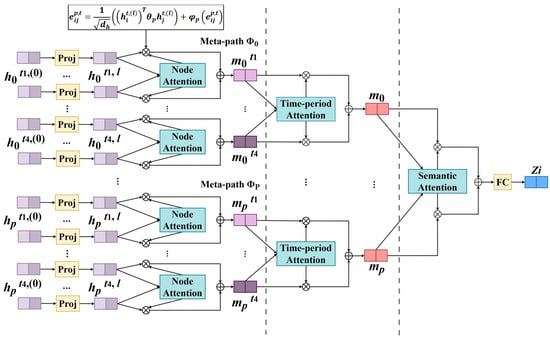

To achieve fine-grained spatio-temporal interaction modeling within the heterogeneous traffic graph, we design the EA-HAN based on the heterogeneous graph attention mechanism [62]. Figure 5 illustrates the internal structure of the EA-HAN. This study innovatively introduces the directed meta-path “inbound road segment–intersection–outbound road segment” and a time-aware multi-level aggregation mechanism. This design aims to more realistically simulate the directed flow characteristics inherent in traffic networks. By explicitly modeling the transitivity of flow directions and local path constraints, it enhances the model’s ability to capture the spatio-temporal features of upstream and downstream traffic flows.

Figure 5.

Structure of Edge-Augmented Heterogeneous Attention Network (EA-HAN) module. The symbol ⊕ represents the concatenation operation.

The model input denotes the representation of each node i during time period t. This representation is obtained by applying a specific time-decoupled projection to the concatenation of the node’s static features and its dynamic temporal features .

- (1)

- Meta-Path Aware Attention Mechanism

To capture the high-order semantic relationships between nodes, we design specific attention computations for each meta-path. The core innovation lies in introducing an edge feature encoding function for the directed meta-path, thereby enhancing the model’s capacity to model directed traffic behaviors. The correlation weight between node i and its neighbor node j under meta-path is computed as follows:

Here, is the transformation matrix specific to meta-path . is the edge feature encoding function: for undirected meta-paths and , ; for the directed meta-path, , where is a weight vector for edge feature encoding. An additional non-linear MLP layer is incorporated to enhance the representational capacity of the edge features, explicitly encoding the directional characteristics of traffic flow. The attention weight from node i to node j is subsequently obtained by normalizing the correlation weights using the Softmax function.

- (2)

- Time-Sensitive Information Aggregation

To capture the temporal relationships between nodes in the traffic network across different time periods, the model employs a multi-head attention mechanism and aggregation strategy for each time period and meta-path, enabling time-sensitive information interaction and high-order dependency modeling. The model first performs time-sensitive, weighted aggregation of neighbor node information within a single meta-path:

Here, denotes the concatenation operation of the H attention heads, and represents the representation of node j at time period t after processing by the l-th network layer. Specifically, for the directed meta-path , a direction-preserving signal term and a direction encoding matrix are introduced, enforcing the retention of directional information: , thereby better emphasizing the directional properties of traffic flow.

Subsequently, the aggregated representations from different time periods are integrated into a comprehensive representation for meta-path p using learnable cross-time attention, allowing the model to adaptively focus on critical periods. The attention weight coefficient for each time period is computed as:

This mechanism enables the model to adaptively aggregate information from different time periods, enhancing its perception of temporal dynamics.

- (3)

- Hierarchical Information Fusion

Finally, the model performs a global integration of features across different meta-paths. The importance of each meta-path is weighted using learnable coefficients :

Here, denotes the attention weight associated with meta-path p, reflecting its contribution to the node representation. represents the updated representation of node i at layer .

Following the aggregation of meta-path representations, a residual connection mechanism is applied. This preserves information from previous layers while introducing non-linear mapping and dropout operations, enhancing the model’s ability to handle complex traffic scenarios.

Here, denotes the final fused representation for node i, incorporating multi-modal information from all time periods.

This design balances dynamic features from different time periods and meta-paths, effectively improving the model’s robustness and adaptability in downstream tasks such as anomaly detection.

2.4.2. TDC-GCN-GAT

To address the limitations of EA-HAN in modeling local topology, we propose TDC-GCN-GAT. This module constructs a comprehensive adjacency matrix that integrates static topology with dynamic traffic states. Building upon this, it achieves fine-grained modeling of dynamic interactions between local road segments through the synergistic use of GCN [28] and GAT [63].

First, by combining different adjacency matrices, the module captures both static topological relationships and dynamic traffic states, enabling preliminary information integration via neighbor-based smooth aggregation in the GCN layer. Specifically, using the set of road segment nodes , where N is the number of segments, the node features include static features and dynamic temporal features across four time periods. We comprehensively characterize the road network structure by integrating three types of adjacency matrices:

- Intersection Direct Adjacency Matrix . This matrix is used to reflect whether two road segments are directly connected via an intersection. We construct intersection direct adjacency matrices of three adjacent orders. If road segments i and j are connected via a k-order direct connection at intersection k, then:

- Regional Indirect Adjacency Matrix . This matrix is used to model the indirect relationships between road segments belonging to the same region. We construct three regional indirect adjacency matrices. If road segments i and j belong to the same region but are not connected via an intersection, then:

- Time-Slot Dynamic Adjacency Matrix . This matrix is computed based on the dynamic traffic characteristics (e.g., flow, speed, stay time) for each time slot t. It is dynamically calculated using the time-slot features:

Subsequently, the model integrates the three adjacency matrices using the following formula to form the final comprehensive adjacency matrix :

where , and are learnable parameters (with being a shared weight across time slots). These parameters are initialized and then optimized during the model training process, allowing the framework to dynamically adjust and balance the contributions of static topological connections and dynamic temporal states.

Based on the constructed comprehensive adjacency matrix, we adopt a hierarchical feature learning strategy, leveraging the synergistic work of GCN and GAT to achieve progressive learning from basic structural features to refined interactive features. We perform feature propagation on the comprehensive adjacency matrix using a two-layer GCN to obtain structure-aware basic node representations. This stage incorporates a residual connection mechanism to ensure training stability:

where , is the ReLU activation function, and is the learnable parameter matrix for the l-th layer.

Building upon the basic features output by the GCN, GAT is introduced for representation refinement, achieving more fine-grained modeling of spatial relationships through differential weighting of neighboring nodes. The attention coefficients are computed as follows:

where is a learnable linear transformation matrix, and is a learnable attention vector. The attention weights are obtained by softmax normalization, enabling the weighted aggregation of neighbor information.

The GAT outputs for each time slot t are fused using time-slot specific learnable weights , forming the final local feature representation for the node. This representation is further integrated by summation with the global semantic features generated by EA-HAN module, constituting the complete spatial representation for the node.

The TDC-GCN-GAT module, through its meticulously designed method for constructing the comprehensive adjacency matrix and the synergistic GCN-GAT modeling architecture, achieves fine-grained characterization of local traffic dynamics. It effectively complements the global heterogeneous semantic modeling performed by the EA-HAN module. Together, they provide comprehensive and accurate spatial context information for the trajectory anomaly detection task.

2.5. LSTAD

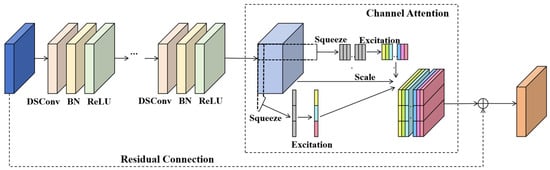

2.5.1. BARDSC

To effectively capture short-term abrupt anomalies in trajectories, this paper proposes BARDSC. Building upon the Residual Depthwise Separable Convolution (RDSC) [64], this module innovatively incorporates a bidirectional channel attention mechanism. The detailed structure of this mechanism is illustrated in Figure 6. By performing adaptive weighting of features along the trajectory point and channel dimensions, it significantly enhances the capability to extract complex spatio-temporal features.

Figure 6.

Structure of the Bidirectional Channel Attention Mechanism. The colored blocks are for illustration purposes only and do not represent specific categories.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the module first encodes the input sliding window features using a residual depthwise separable convolution, obtaining the initial feature representation . This structure substantially reduces the number of parameters through the separation of depthwise and pointwise convolutions, while residual connections mitigate the vanishing gradient problem. Subsequently, the core bidirectional channel attention mechanism refines the features along two distinct dimensions.

The Horizontal Attention Mechanism focuses on dependencies between different trajectory points. It computes the weight of each trajectory point’s contribution to the output features, which is then used to weight the original features , resulting in trajectory-direction weighted features . Specifically, a squeeze operation aggregates the feature map along the temporal dimension, followed by an excitation operation to generate the attention weights in the trajectory point direction:

where, denotes Global Average Pooling along the channel dimension, and are the learnable weight and bias for the trajectory point direction, and is the Sigmoid activation function.

The Vertical Attention Mechanism emphasizes the correlations between different feature channels. It calculates the importance weight of each channel for the output, yielding channel-direction weighted features . The attention weights for the channel direction are computed as follows:

where, denotes Global Average Pooling along the trajectory point dimension, and and are the learnable weight and bias for the channel direction.

Finally, the enhanced features from both directions, and , are summed and fused, and passed through a fully connected layer to obtain the module’s final feature vector .

Furthermore, we incorporate dilated convolutions into the depthwise separable convolution framework. By adjusting the dilation rate, the convolutional kernel can selectively skip over pixels, thereby expanding the receptive field. This dilated convolution capability effectively captures long-range dependencies, aiding the model in learning and understanding complex spatio-temporal patterns.

This module ensures gradient flow through residual connections, maintains computational efficiency via depthwise separable convolution, and achieves refined feature reconstruction through the innovative bidirectional attention mechanism, effectively enhancing the model’s sensitivity to short-term anomalous behaviors.

2.5.2. DSTN

To effectively detect anomalous behaviors, such as a vehicles traveling at low speeds over long segment, which require long-term dependency modeling, this paper designs DSTN. This module adopts a multi-branch parallel architecture aimed at collaboratively extracting macro-level temporal features from different time scales.

The core of this module consists of four parallel processing branches, with each branch dedicated to a specific temporal span. The input for the i-th branch is defined as the combination of the current trajectory point and the preceding i historical trajectory points, which can be expressed as , thereby capturing contextual information at different granularities.

Within each branch, we employ a cascaded structure of a Dilated Temporal Convolutional Network (D-TCN) [65] and a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) [66]. The D-TCN is responsible for expanding the receptive field through dilation rates to efficiently capture long-range dependencies; the output sequence features from the D-TCN are then refined by the GRU to model dynamic temporal patterns. We denote the output feature from this two-stage processing in the i-th branch as .

To adaptively fuse the features from these four different temporal perspectives, we introduce a channel attention fusion layer. This layer calculates a weight for the features of each branch, indicating its contribution to the final anomaly detection task:

where and are learnable parameters, and the Sigmoid function ensures the weights fall within the range [0, 1].

Finally, the features from the four branches are aggregated via a weighted sum based on their importance weights, forming the comprehensive macro-level feature representation . This multi-branch parallel design coupled with the attention fusion mechanism enables the DSTN to flexibly and efficiently integrate multi-scale temporal information, significantly improving the model’s capability to detect long-term trend-based anomalies and its robustness across different scenarios.

2.5.3. Trajectory Prediction

Trajectory prediction is based on the fusion of the short-term features from BARDSC and the long-term features from DSTN, providing the critical basis for subsequent anomaly scoring.

The core of this module is a cross-window channel attention mechanism. It employs a learnable weight vector to adaptively balance the importance of short-term and long-term features, generating the final fused feature representation:

where the attention weight is a learnable parameter computed through a fully connected layer followed by a Sigmoid activation function, ensuring normalized weights and allowing the model to adaptively balance short-term with long-term features.

Based on the fused features , the module directly predicts the motion states (including direction and speed) for the next N trajectory points through a fully connected network. Finally, based on these predicted states, the specific longitude and latitude coordinates of the future trajectory points are recursively calculated using a standard kinematic model.

This design, through the cross-window channel attention mechanism, ensures that the predicted trajectory is responsive to both short-term driving behaviors and long-term travel trends, thereby providing an accurate and reliable benchmark for trajectory anomaly detection.

2.5.4. Anomaly Scoring

This paper employs a sliding window-based anomaly scoring mechanism to determine trajectory anomalies. This method calculates an anomaly score for each window and accumulates them based on a dynamic threshold, ultimately achieving anomaly judgment at the entire trajectory level.

- (1)

- Sliding Window Anomaly Score

The anomaly score for each sliding window is determined by the weighted distance between the predicted and actual positions of the trajectory points within it. To capture temporal dynamics, this score further considers the influence of the most recent historical windows, with their weights decaying as the temporal distance increases. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where (, ) and (,) are the predicted and actual coordinates of the n-th trajectory point, respectively. Here, N = 5 is the prediction horizon, and K = 3 is the number of historical windows considered for temporal smoothing. These values were configured based on the system’s real-time requirements and the temporal characteristics of driving anomalies (see Section 2.8.2 for details).

To adaptively determine whether a window is anomalous, a dynamic baseline threshold is established, calculated from the mean and standard deviation of the scores from the recent t windows:

where k is used to adjust the sensitivity of the threshold.

- (2)

- Trajectory Cumulative Anomaly Score

Based on the comparison between the window score and the dynamic threshold, the trajectory’s cumulative anomaly score is updated according to the following rule:

If , the cumulative score remains unchanged. When the cumulative score exceeds a pre-defined fixed threshold T, the entire trajectory is flagged as anomalous.

This method, by combining local window anomalies and global trajectory cumulative anomalies, achieves anomaly detection that is both fine-grained and robust.

2.6. Loss

To co-optimize the trajectory prediction and anomaly detection tasks, the model is trained end-to-end. The overall loss function is defined as the weighted sum of the prediction loss and the anomaly detection loss:

where is the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss for the trajectory prediction task, and is the Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss for the anomaly detection task. The hyper-parameters and are used to balance the relative importance of the two tasks during training. Through empirical tuning on a validation set, both are set to 0.5 to assign equal initial weighting to both tasks, with their final effective balance being achieved through joint training.

This multi-task loss function ensures that the model enhances trajectory prediction accuracy while simultaneously optimizing its discriminative capability for anomalous behaviors.

2.7. Model Complexity and Real-Time Analysis

This paper adopts an offline-online decoupled architecture to meet the stringent real-time requirements of practical applications while ensuring model detection performance. As described in Section 2.3 and Section 2.4, both CL-CD and UNIM are executed in the offline stage. Specifically, the CL-CD module is responsible for generating augmented anomalous trajectory data, and the UNIM module is responsible for learning and outputting the static embedding representations of road network nodes. The computational complexity of these two modules does not affect the system’s online inference performance. The online deployment part only includes LSTAD and the lightweight anomaly scoring mechanism, significantly reducing the real-time computational burden.

The complexity of the core online module, LSTAD, warrants specific attention. Its theoretical time complexity primarily stems from the horizontal attention mechanism within the BARDSC described in Section 2.5.1. This mechanism needs to compute the correlations between all trajectory point pairs within the sliding window, resulting in a theoretical time complexity of O(n2), where n represents the number of trajectory points in the sliding window.

Nevertheless, the feasibility of this model in a practical system is fundamentally guaranteed by a key system parameter. To ensure real-time response, the system sets the sliding window size n to a very small fixed value (n = 3–5). This implies that, even in the worst case, the model only needs to process a maximum of 25 element-wise relation pairs. This design confines the computational load of the core attention mechanism to a very low constant range, thereby circumventing the potential computational bottleneck posed by the quadratic complexity.

Based on the above deliberate design, the online part of the model demonstrates excellent operational efficiency. In evaluations, the online modules process a single trajectory with a latency consistently within 1–5 ms on an Intel Core i7-1360P CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). This result indicates that the proposed MTRI method not only holds advantages in detection accuracy (as shown in the experiments in Section 3) but also possesses the superior computational efficiency required to handle the high-concurrency and low-latency demands of real-world intelligent transportation scenarios, laying a solid foundation for its practical application.

2.8. Experimental Setup: Datasets and Implementation

2.8.1. Datasets Description

This study is conducted based on a real-world taxi trajectory dataset from Porto, Portugal [67]. Additionally, we integrated high-precision road network data constructed based on map data [68] and historical weather data [69] to build richer trajectory context information. The key attributes of the various data sources, along with their descriptions and roles in the study, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of Core Data Attributes.

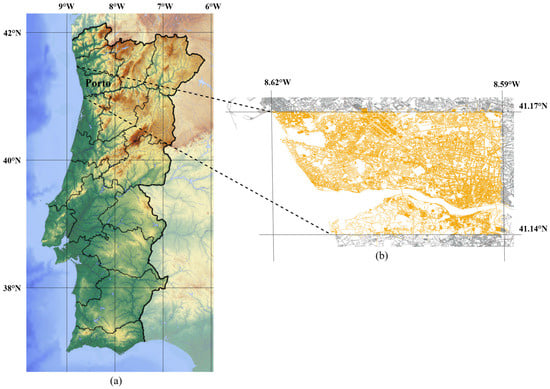

To ensure that the experiment is relevant and representative, we limited the scope of the study to the central urban area of Porto (latitude and longitude boundaries: [41.14° N, 8.62° W] to [41.17° N, 8.59° W]), as illustrated in the map presented in Figure 7. Figure 7 provides a two-level geographical context: (a) a map of Portugal with the location of Porto city marked, adapted from Reference [70]; and (b) a detailed road network map of our defined study area generated for this work. This combined visualization clearly delineates the geographic location of the study area and provides a detailed analysis of its internal road network structure. The area covers a continuous gradient from the busy city center to the outer suburbs, containing diverse urban functional scenarios such as commercial districts, residential areas and transportation hubs. Furthermore, by analyzing traffic flow variations across road segments, we divided a day into four typical periods: morning peak, noon peak, evening peak, and off-peak, thereby delineating periodic traffic pattern changes.

Figure 7.

Geographical context and road network of the study area in Porto, Portugal. (a) Geographic location of the study area in Portugal. (b) Road network of the study area with latitude and longitude references.

This study aims to detect abnormal driving behaviors of taxis under a clear passenger-carrying state. To address the absence of a direct “empty/occupied” status label in the dataset and precisely align with our research objective, we conducted systematic data preparation. First, to establish a well-defined passenger-carrying scenario, we restricted the analysis to all trips with CALL_TYPE = ‘A’ (central dispatch). This methodological choice is critical, as such trips have a predetermined destination, ensuring the taxi operates under the “pre-booked at a stand or hailed on-street” from the start. This approach fundamentally excludes reasonable detours arising from other operational states, such as empty cruising or random passenger-seeking, thereby focusing the anomaly detection on abnormal paths and behaviors during assigned trips. Second, to ensure the quality and consistency of the trajectory data, we performed fundamental quality preprocessing. This involved processing trajectories for continuity and applying length-based filtering to remove excessively short records, thereby eliminating invalid fragments caused by signal loss or recording errors. Finally, to further enhance data reliability, we established cleaning rules based on physical plausibility. Grounded in common sense regarding passenger trips, we removed trajectory points with instantaneous speeds exceeding the reasonable urban road limit of 120 km/h, as well as trips where the actual path exhibited unreasonable deviation (e.g., a detour distance exceeding three times the shortest feasible path) compared to the shortest feasible route between the origin and destination.

After completing the above key data selection and quality preprocessing, the original trajectory data then undergoes a systematic preprocessing process. First, data cleaning was performed to filter out obvious positional outliers, duplicate records, and invalid trajectory segments containing missing values. To address inherent GPS signal drift and “jump” anomalies, a map-matching technique was employed to project the noisy trajectory points precisely onto the actual road network. This step corrects positional deviations and ensures the topological continuity of trajectories within the road network. Subsequently, key kinematic features (including instantaneous speed, acceleration, heading, and turning rate) were extracted from the cleaned trajectories. Furthermore, leveraging the historical trajectory data, we conducted a statistical analysis of the road network to derive key traffic state indicators for different peak periods. These indicators encompass multi-faceted traffic rates, including the traffic flow per peak (calculated as vehicle count per road segment and intersection) [71], the historical average travel speed, and a measure of congestion levels reflected in the average stop delay at roads and intersections. They were computed for each road segment and intersection, thereby thoroughly characterizing the dynamic traffic conditions of the network.

Given the scarcity of real anomalous trajectory annotations, we computed a comprehensive anomaly score based on trajectory geometry, travel frequency, and the aforementioned spatio-temporal context to generate reliable trajectory labels.

Building upon this solid spatio-temporal framework, and acknowledging the scarcity of anomalous trajectories in real data, we constructed a benchmark dataset covering multi-dimensional scenarios to comprehensively evaluate model performance. We systematically introduced control variables along two dimensions: The first is multi-level anomaly intensity. Using a combination of data augmentation and the CL-CD module, by controlling key parameters such as detour distance and frequency, persistence of looping behavior, and degree of speed mutation, we generated anomalous trajectories ranging from L1 (Minor) to L3 (Severe). The second is multi-level anomaly prevalence. Following related research [72], We set anomaly ratios of 0.1%, 0.3%, and 0.5% to simulate different real-world situations.

Ultimately, although the data used in this study relies on trajectory data from a single city, it integrates an inherently diverse geographical scope and temporal periods with different traffic patterns, and further introduces the two key variables of multi-level anomaly intensity and multi-level anomaly prevalence. This strategy enables us to effectively evaluate the model’s robustness and adaptability in a controlled experimental environment when facing various complex scenarios, ranging from city center to suburbs, peak to off-peak hours, minor to severe anomalies, and sparse to prevalent occurrences.

This gradient design of anomaly intensity can be visually validated through the generated trajectories. As shown in Figure 8, the blue trajectory represents the normal driving path without external interference. In contrast, the red trajectory exhibits a severe detour anomaly, where the vehicle selects a complex, circuitous path that significantly deviates from the normal route; the yellow trajectory represents a medium-degree detour, with the vehicle showing identifiable path deviations on certain road segments; and the green trajectory displays only minor anomalies, where the vehicle deviates from the regular path in a few instances. This continuum of anomaly scenarios from minor to severe provides a solid foundation for comprehensively evaluating the model’s detection accuracy.

Figure 8.

Schematic of detour abnormal trajectory generated by CL-CD. The blue line denotes the normal trajectory (), while the green, yellow, and red lines represent detour anomalies of increasing severity, corresponding to minor (), medium (), and severe () deviations, respectively.

2.8.2. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

All experiments are conducted in a Python 3.9.13 environment (Python Software Foundation, Fredericksburg, VA, USA) on an Intel Core i7-1360P CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The CL-CD module is extended based on the open-source implementation of the ControlTraj model [21]. The forward diffusion process is set to 1000 steps with a linear noise schedule and a maximum noise level of 0.02. Unlike the original model, the weights for KL divergence and DTW-based contrastive loss in the objective function are both set to 0.5, while other parameters remain at their default values.

For the EA-HAN module, three meta-paths and eight attention heads are used. The temporal feature dimension is set to 128, and the node feature dimension is 64. The sampling temperature for the residual connection is set to 1.0. In the TDC-GCN-GAT module, both the GCN and GAT layers are two-layer architectures with a hidden dimension of 32. Each GAT layer includes 8 attention heads.

In the BARDSC module, the convolution kernel size is set to 3, with 3 and 11 channels, respectively. The DSTN module consists of three parallel branches with dilation rates of 1 and 2, and a hidden dimension of 128. The model predicts the positions of the next N = 5 trajectory points in each forward pass, which provides a sufficient look-ahead for timely anomaly detection while keeping the prediction task tractable for real-time operation.

For anomaly scoring, the decay parameter K = 3 for historical window weights strikes a balance between incorporating recent context and avoiding over-smoothing. The dynamic baseline is calculated using the mean and standard deviation of the most recent 15 sliding windows. The threshold T for cumulative anomaly detection is set to 300. The model is trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 64.

2.9. Experimental Design: Baselines and Evaluation Metrics

2.9.1. Baseline Methods

To validate the effectiveness of the CL-CD in the anomalous trajectory generation task, we selected several representative trajectory generation models as baselines, covering mainstream paradigms of generative models:

VAE [16]: As a representative of likelihood-based latent variable models, it generates coherent trajectories but may be overly smooth, struggling to capture complex anomalies.

TrajGAN [15]: An application of Generative Adversarial Networks in the trajectory domain, it produces high-quality samples but may suffer from mode collapse and training instability.

DiffTraj [13]: Represents the current advanced application of diffusion models for trajectory generation; however, its generation process lacks fine-grained control over anomalous semantics.

ControlTraj [21]: As the state-of-the-art conditional diffusion trajectory generation model, it serves as the most direct and powerful comparative baseline for our CL-CD model. However, it was originally designed to generate normal trajectories that conform to road network constraints.

To validate the effectiveness and robustness of our proposed trajectory anomaly detection method, we selected five representative methods for comparison, ensuring breadth and depth. These methods cover various technical routes, from traditional rule-based to cutting-edge deep learning approaches:

TROAD [50]: Detects anomalies by partitioning sub-trajectories and employing a hybrid distance metric, representing the classic paradigm based on partitioning and distance.

iBAT [51]: Utilizes the isolation forest principle and rasterizes trajectories, serving as a typical model based on isolation-based anomaly detection and symbolic representation.

ATDC [73]: Focuses on using a custom-defined Distance (DIS) to quantify trajectory similarity for classifying anomaly types.

GM-VASE [47]: Employs a Gaussian Mixture Variational Autoencoder to model normal routes in the latent space, representing a strong baseline based on deep generative models.

GCSSL-ASD [74]: Adopts Graph Convolutional Networks and contrastive learning for anomalous sub-trajectory detection, representing one of the current state-of-the-art methods based on graph-structured self-supervised learning.

The above baseline forms a three-dimensional comparison framework in terms of trajectory representation, detection mechanism, and modeling granularity, providing a solid foundation for verifying the comprehensive performance of the MTRI model.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed trajectory prediction module, we selected five representative temporal models as baselines, constituting a technological evolution path from classical recurrent networks to complex hybrid architectures.

LSTM [75]: A type of recurrent neural network with gating mechanisms, known for its superiority in capturing long-term dependencies.

GRU [36]: A simplified variant of LSTM, containing only reset and update gates, offering lower computational complexity.

Dual-LSTM [76]: Models vehicle interactions using two LSTM branches to enhance prediction accuracy.

EMD-CNN-RNN [77]: Applies Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) to extract sub-sequences, followed by CNN and RNN for multi-scale feature modeling.

AMGB [78]: Combines attention, graph convolution, and bidirectional LSTM to extract multi-modal features, enhancing spatial and temporal resolution in trajectory prediction.

The models listed above encompass different modeling paradigms, including traditional recurrent networks, hybrid architecture models, and graph neural networks, providing a solid basis for the systematic comparison of our proposed model. Comparisons with these methods allow for a comprehensive evaluation of the advantages of our approach in terms of temporal modeling accuracy, robustness, and architectural innovation.

2.9.2. Evaluation Metrics

For a comprehensive evaluation of the quality of generated trajectories, we adopted the following three metrics:

Density Error: Measures the spatial density discrepancy between the distribution of generated trajectory points and that of real trajectory points. A lower error indicates better geographical coverage rationality of the generated trajectories.

Trip Error: Assesses the deviation in trip coherence (e.g., origin-destination matching, path reasonableness) of the generated trajectories.

Length Error: Measures the consistency in average length between the generated trajectories and the real trajectories.

For the trajectory prediction task, we selected a series of metrics that measure the discrepancy between predicted values and ground truth, including Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Average Displacement Error (ADE), and Final Displacement Error (FDE). Furthermore, to calculate the true geographical distance between two points on the Earth’s surface, we employed the Haversine distance, which is calculated as follows:

where denotes latitude in radians, denotes longitude, and is the Earth’s radius, typically taken as 6371 km.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Comparative Experiments

3.1.1. Anomalous Trajectory Generation Comparison Results

This section provides a comprehensive evaluation of the CL-CD model’s performance in generating trajectory data across varying anomaly levels through systematic generation experiments. Based on the quantitative results presented in Table 3, the following key conclusions can be drawn: our CL-CD model significantly outperforms existing baseline methods in both the geographical plausibility of the generated trajectories and the fidelity of the anomalous patterns.

Table 3.

Comparison of anomalous trajectory generation under different anomaly degrees.

First, the CL-CD model achieves comprehensive across multiple generative quality metrics. As shown in Table 3, for the three anomaly levels from L1 to L3, CL-CD consistently achieves the lowest values on the most representative metrics, namely Trip Error and Length Error. For instance, in the critical L2 anomaly scenario, its Trip Error (0.0074) and Length Error (0.0086) are substantially lower than those of the closest-performing baseline, ControlTraj. This robustly demonstrates its unique advantage in controlling trajectory trip coherence and length consistency, enabling the generation of trajectory data that not only adheres to road network constraints but also accurately reflects anomalous behaviors.

Second, the CL-CD model demonstrates strong robustness, showing low sensitivity to variations in anomaly intensity. As the anomaly degree escalates from L1 to L3, the errors of all baseline models exhibit an increasing trend, whereas the metrics for CL-CD remain consistently high with minimal fluctuation. Notably, for the Trip Error, which best reflects complex anomalous behaviors, CL-CD’s value under severe L3 anomalies (0.0065) even surpasses the performance of other models under minor L1 anomalies. This confirms that its dual-condition generation mechanism can effectively adapt to a broad spectrum from minor deviations to severe anomalies, ensuring the diversity and authenticity of the generated samples.

Finally, the experimental results validate the exceptional effectiveness of the dual-condition contrastive generation framework. The comparison with the strongest baseline, ControlTraj, reveals that although ControlTraj excels in spatial distribution density (Density Error), it falls short in capturing anomalous semantics (Trip Error and Length Error). This contrast precisely illustrates that the dual-condition contrastive mechanism between normal and anomalous trajectories, introduced by CL-CD, is pivotal for achieving high-quality anomalous trajectory generation. This mechanism enables the model to deeply understand and replicate the essential characteristics of anomalous behaviors while conforming to geographical topology, thereby achieving an optimal balance across all metrics and providing unprecedented high-quality data support for downstream detection tasks.

3.1.2. Anomaly Detection Comparison Results

This section presents a systematic comparative evaluation of the MTRI model’s performance across various scenarios characterized by different anomaly ratios and anomaly degrees. Based on these experimental results, a clear conclusion can be drawn: our model significantly outperforms existing baseline methods in both detection stability and scenario generalization capability.

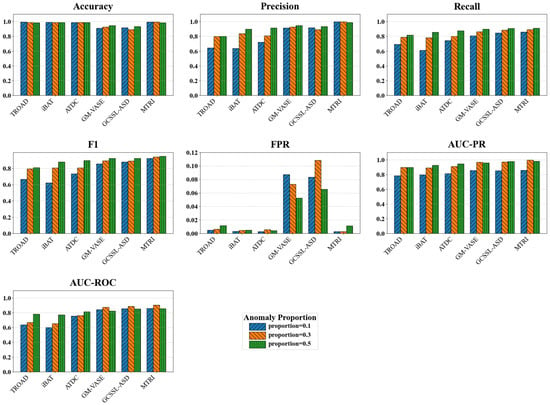

First, the MTRI model exhibits strong robustness, being largely insensitive to the distribution of anomalies. This is validated through comprehensive tests under varying anomaly ratios, as summarized in Table 4 and visualized in Figure 9. Table 4 provides a quantitative comparison of detection performance metrics across different anomaly proportions, while Figure 9 graphically illustrates the trends of these core metrics. The model’s core performance metrics consistently maintained the highest levels with minimal fluctuation. For instance, its F1-score steadily increased from 0.9231 at the 0.1% anomaly ratio to 0.9485 at the 0.5% ratio. This demonstrates that regardless of whether anomalous behaviors are sparse or prevalent in the data, our method can dynamically adjust the balance between precision and recall through its internal mechanisms, thereby achieving stable and reliable detection.

Table 4.

Comparison of anomaly detection methods under different anomaly proportion scenarios.

Figure 9.

Comparison of anomaly detection performance under anomaly proportion scenarios.

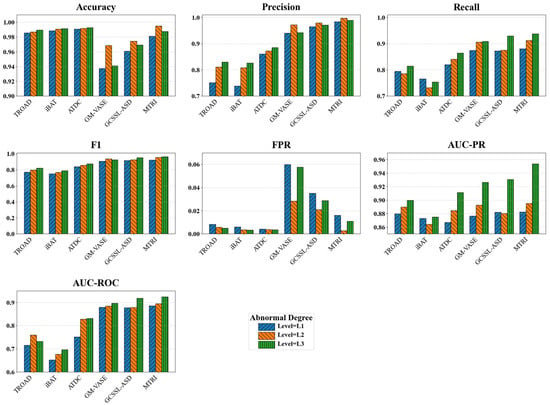

Second, the model demonstrates exceptional capability in identifying and discriminating anomalies of varying intensities. Results in Table 5 and Figure 10 further show that the MTRI model performs excellently across all anomaly degrees, and its effectiveness improves as the anomaly severity increases. This result strongly indicates that for the most practically significant L3 (severe) anomaly detection, our model achieved the highest F1-score of 0.9633 among all scenarios, coupled with a high recall of 0.9378. This finding powerfully demonstrates that our model can accurately capture those highly significant anomalies that deviate fundamentally from normal patterns, which are often of greater value. In practical applications, identifying these severe anomalies is typically more critical than detecting minor deviations.

Table 5.

Comparison of anomaly detection performance under different anomaly degree scenarios.

Figure 10.

Comparison of anomaly detection performance under anomaly degree scenarios.

In summary, these experimental results validate the effectiveness of our model’s design philosophy. The multi-modal trajectory embedding and spatio-temporal relationship extraction mechanisms employed by the model enable it to deeply understand complex traffic dynamics. Consequently, it exhibits superior ranking capability as reflected in metrics like AUC-PR and maintains consistently high performance across various challenging scenarios. This not only confirms the advancement of MTRI in the anomaly detection task but also highlights its significant potential for real-world application.

3.1.3. Trajectory Prediction Comparison Results

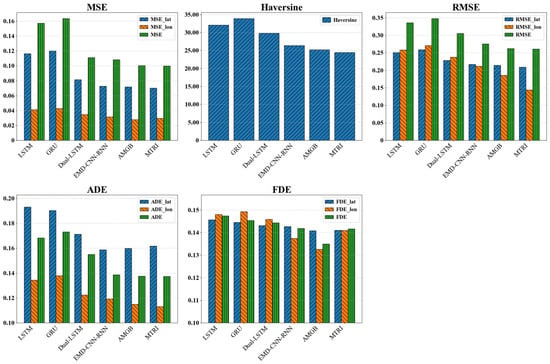

The accuracy of trajectory prediction forms the foundation for the reliability of the anomaly detection task. The comparative experiments in this section demonstrate that our proposed MTRI model exhibits significant precision advantages in the trajectory prediction task. Table 6 quantitatively summarizes the performance evaluation results of various trajectory prediction models across multiple error metrics, while Figure 11 provides a visual comparison of these metrics across different models. These results provide high-quality assurance for subsequent anomaly score calculation.

Table 6.

Performance evaluation results of trajectory prediction model.

Figure 11.

Comparison of different evaluation indicators of the trajectory prediction model.

First, the MTRI model achieved the optimal level in overall prediction error. As shown in Table 6, our model leads comprehensively across key error metrics. Its Haversine distance (24.46 m) and MSE (0.0999) are the lowest among all compared models, providing direct evidence of the model’s high accuracy in predicting absolute geographical location. Simultaneously, its ADE (0.1374) and RMSE (0.2608) also reach the best or near-best levels, indicating outstanding performance in the smoothness and consistency of the entire trajectory sequence.

More importantly, the MTRI model maintains strong competitiveness compared to advanced deep learning models. Analysis combined with Figure 10 shows that although specialized prediction models like AMGB perform closely to ours on some metrics, MTRI establishes a clear advantage in the critical geographical distance error (Haversine). This result validates the effectiveness of our design that integrates trajectory embedding with spatio-temporal relationship modeling. It enables the model to better understand the movement intent of objects, resulting in predictions closer to the real path, rather than merely optimizing numerical errors.

In summary, the trajectory prediction experiments validate the effectiveness of the MTRI framework at a fundamental task level. The accurate and reliable trajectory predictions it provides establish a solid data foundation for the anomaly detection method based on the deviation between predicted and actual trajectories, ensuring the confidence in the final anomaly detection results.

3.2. Ablation Study