Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between Cultural Intelligence (CI) and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) and to test the mediating role of Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE). A correlational survey design was employed with full-time academics in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (N = 391). Standardised instruments were administered: the Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS), the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS), and the Internationalisation Perception Scale for Academics (IPSA). Construct validity and reliability were verified via confirmatory factor analysis, and the structural model was estimated using structural equation modelling (SEM) in SPSS–AMOS. The analysis revealed that CI exerts a positive and statistically significant effect on IS. CI was also found to be positively associated with IHE, and IHE demonstrated a positive and significant effect on IS. Mediation testing indicated that IHE functions as a significant partial mediator of the CI–IS relationship. Robustness checks with control variables showed that academic rank and faculty type have small but significant positive associations with IS. Overall, the findings suggest that the development of CI among academic staff directly enhances intercultural responsiveness and, additionally, strengthens IS through engagement with internationalisation processes. The results provide practical guidance for universities seeking socially sustainable internationalisation, indicating that institution-level strategies that embed intercultural learning and support academics’ international engagement may amplify the translation of CI into demonstrable intercultural sensitivity.

1. Introduction

Intercultural competence is defined as the capacity of individuals to interact effectively and appropriately across diverse cultural contexts. To account for the cognitive and behavioural dimensions of this competence, Cultural Intelligence (CI) has been conceptualised as the ability to function effectively in culturally diverse settings [1]. Intercultural Sensitivity (IS), in contrast, is considered an affective domain reflecting individuals’ awareness of, respect for, and positive attitudes towards cultural differences [2]. These constructs constitute the core human dimensions of Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE).

Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE) is defined as the process through which international and intercultural dimensions are systematically integrated into the teaching, research, and service functions of higher education institutions [3]. Within this framework, the development of intercultural competence among both students and academic staff has been recognised as a fundamental requirement for higher education systems operating in developing and globalising contexts [4,5]. However, progress continues to be constrained by fragmented IHE strategies, limited learning opportunities, and misalignment between global and local goals [6,7]. Building on this critique, meaningful internationalisation is understood to require the deliberate integration of intercultural learning outcomes into curricula and pedagogy, rather than being treated as an ancillary or mobility-centred activity [6]. Furthermore, the literature highlights the prevalence of superficial approaches to IHE that prioritise student mobility over deeper structural and pedagogical transformation [3,8].

This critique is consistent with arguments suggesting that internationalisation in higher education is frequently reduced to mobility-driven indicators, while its deeper curricular, pedagogical, and intercultural dimensions remain underdeveloped, resulting in superficial forms of internationalisation rather than transformative institutional change [8,9]. From an interculturality perspective, internationalisation is conceptualised not merely as an institutional strategy but as a relational and process-oriented practice through which intercultural meanings are co-constructed within everyday academic interactions, rather than generated solely through mobility-based activities [8].

Fostering local sustainable development goals (SDGs) with global curricula is accompanied by inequities in sustainable development goals progress. SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) lack progress due to insufficient intercultural sensitivity (IS) and preconceptions [10,11]. It is common for institutions to lack the capacity to develop the cultural intelligence (CI) gap, the ability to operate effectively in diverse contexts, which further prolongs the intercultural gap [1,12,13]. There is a need for education and policy models within higher education institutions that incorporate sustainability and pervasive intercultural competence throughout the institution [5].

In advanced higher education, sustainability refers to the implementation of internationalisation across its social, cultural, and ethical dimensions. The integration of internationalisation and global citizenship competencies supports flexibility, reduces bias, and encourages engagement with global contexts [14,15]. However, without the corresponding affective dimension—namely Intercultural Sensitivity (IS), which involves the ability to appreciate and respect differences—and without sufficient Cultural Intelligence (CI), meaningful engagement with the world is unlikely to occur [2,16]. Hence, IS is the result of, and at the same time, the outcome of true internationalised learning [17,18,19].

What is underexamined is the influence of CI within the processes of internationalisation in IS. Internationalisation does not have to be a static background; it can actively facilitate the conversion of cultural understanding to real participation [20,21]. Academic staff have a crucial role as both enablers and active participants in the implementation of the institutional framework within a teaching and cooperative context [4]. The internationalisation of higher education (IHE) can, in this respect, be constructively transformative, increasing the depth of intercultural engagement while addressing the sustainability of education [22].

Although the relationship between Cultural Intelligence (CI) and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) has received substantial empirical attention, existing studies have predominantly framed this relationship at the individual level, focusing on personal traits, motivational orientations, and cognitive-affective mechanisms [1,23,24,25]. These constructs have largely been conceptualised as individual competencies developed through personal experiences or learning strategies, with limited attention to the role of institutional structures in shaping them. What remains underexplored is how institutional mechanisms—particularly the organisational processes of Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE)—mediate the transformation of cognitive–behavioural competencies associated with CI into the affective and participatory orientations reflected in IS. Prior research has typically treated IHE as a static context or an outcome, focusing on aspects such as student mobility or curriculum policy, rather than as a dynamic and transformative mediating factor in intercultural competence development [3,6,8,26]. By positioning IHE as a mediating variable, this study shifts the analytical focus from individual-level traits to institutional-level processes, offering a novel and contextually grounded understanding of how intercultural learning and engagement can be structured and enhanced in globalised academic environments.

The aim of this study is to examine the relationship between Cultural Intelligence (CI) and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) by testing the mediating role of Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE), thereby contributing to the theoretical and practical understanding of sustainable internationalisation and intercultural competence development in higher education.

1.1. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

1.1.1. Cultural Intelligence (CI)

Cultural Intelligence is the construct that explains the effectiveness of individuals in intercultural situations. CI is a capacity developed through social learning theory [27]. Cultural Intelligence (CI) was first defined as the ability to work and behave appropriately in different cultural contexts [14]. People learn to practice social behaviors through observation and integration of the concept of self-regulated learning as elaborated in context communication theory [28]. Imbued in these theoretical constructs, CI is definable as a type of intelligence that is adaptive in nature and facilitates the dexterous maneuvering within cultural differences.

- Metacognitive CI: One’s cultural learning strategies and assumptions,

- Cognitive CI: Understanding culturally regulated norms and behaviors,

- Motivational CI: The willingness to engage and immerse oneself in different cultures,

- Behavioural CI: The ability to employ appropriate verbal and non-verbal actions [1,12].

With globalised classrooms and research networks, CI has become more integrated into every facet of higher education, including classroom settings [29]. Also, in discussing the profession of academics, the authors define “Intercultural communication in teaching, collaboration, and curriculum design” as a primary professional skill [13]. Achieving cross-disciplinary interactions develops not just the level of integration, but higher-level capabilities like empathy and perspective versatility [30]. Advocates for higher education propose that the system aims to produce responsible global citizens. This social aspect is very important, especially in teaching, to be inclusive towards every learner.

Professionally sociable individuals are defined as those who demonstrate a high level of cross-disciplinary interaction [10]. They see cultural differences as barriers. This trait, implicitly defined from a UNESCO perspective, develops working and educational atmospheres that are social and inclusive [8]. Academics with strong cross-disciplinary interactions are capable of curriculum and pedagogy design that is inclusive, leads diverse international teams, and fosters intercultural understanding [4,20].

Strategies for internationalization, which up to this point have mainly been assessed through quantity of mobility and partnerships, and in this case, intercultural engagement, have been replaced by quality and sustainability [22]. Culture is a core building block of this process. Well-cultured and intelligent people synthesize multiple viewpoints, educate themselves in cross-cultural environments, and exhibit creative and productive solutions to problems [18,31]. In the case of scholars, these abilities are expressed through responsive pedagogy, productive partnerships, and steering internationalization of the domain [6,32], thus equipping them to be global citizens and agents of sustainable change.

1.1.2. Cultural Intelligence (CI) and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS)

Almost every context nowadays involves a cross-cultural setting, which brings with it the need for and application of cultural intelligence [14]. IS represents: “the ability and disposition to appreciate cultural differences and to engage with members of diverse cultural groups” [2]. The synergy of both IS and CI is necessary in all layers of internationalized higher education, particularly faculty members whose scholarship and teaching determine the structures of the cross-cultural climates [4,13].

A combination of intercultural communication with constructivist learning approaches shows how understanding a culture is not only conceptual but involves feeling and doing. CI offers frameworks for navigating different cultures, and IS ensures that these frameworks are enacted with empathy and ethical awareness [33]. High worldmindedness combined with low CI can result in limited active participation and engagement [34,35]. Similarly, IS without adequate CI may remain well intentioned but constrained by unexamined cultural assumptions [24]. Such an imbalance for educators drains motivation and awareness to embrace intercultural competencies [5].

Studies have shown that CI is associated with tolerance, open-mindedness, and adaptability, which are important parts of IS [15,36]. Some motivational and metacognitive aspects of CI facilitate IS by fostering self-reflective awareness and active participation across cultures [1,25]. Recent empirical evidence further indicates that individuals with higher levels of cultural intelligence demonstrate stronger intercultural sensitivity through enhanced adaptive communication, perspective-taking, and sustained engagement in culturally diverse interactions [37]. For faculty, these characteristics inform their pedagogy, scholarly collaboration, and engagement with the international community [20].

IS and CI are essential in converting internationalisation to meaningful learning within globally-engaged universities. Culturally intelligent individuals with high levels of intercultural sensitivity (IS) are able to circumvent ethnocentric attitudes and approach diversity with curiosity and humility [19], which contributes to SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) [10]. Culturally intelligent and integratively socially inclusive faculty are able to perform intercultural role-modeling and go beyond symbolic diversity to inclusion [5,6].

Together, these competencies strengthen social sustainability in international education. Curriculum design that combines multicultural content, experiential learning, and reflective dialogue enhances both constructs [18,38]. The systematic institutionalization of these competencies hinges on faculty development programs [13,32].

CI supplies the intercultural interaction cognitive and behavioral frameworks [1,33], while IS provides the emotional and ethical grounding for authentic participation [2,16]. The deepening of both is critical for the development of responsive and enduring, culturally diverse contexts in higher education [6,8,11]. The goal of this study is to understand the influence of CI on IS, and how this interplay is influenced by the processes of institutional internationalisation.

Given that Cultural Intelligence encompasses cognitive, motivational, and behavioral competencies essential for effective intercultural engagement [39], individuals with higher levels of Cultural Intelligence are expected to demonstrate increased openness, empathy, and adaptive communication—core elements of Intercultural Sensitivity as conceptualised in the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity [40]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1:

Cultural Intelligence has a positive and significant effect on Intercultural Sensitivity.

1.1.3. Cultural Intelligence (CI) and Internationalization in Higher Education (IHE)

Internationalisation of education has redefined the fundamental working tenets of contemporary higher education institutions. The advanced strata of education in every region seek to attain internationalisation as one of its main strategic priorities. Internationalisation is understood as an ongoing institutional process integrating international and intercultural dimensions into the core functions of higher education [3]. This makes it essential for institutions to promote sustained staff and student intercultural interactions. One of the leading factors in enabling this process is Cultural Intelligence (CI), which allows for contextually appropriate engagement across diverse academic and cultural settings [1,6].

CI is now widely acknowledged as a highly valued competence in universities [32,41]. The dynamic nature of Cultural Intelligence (CI) is achieved through cultural awareness, cultural reflexivity, and continuous development of CI itself [12,15]. The academic contribution of the institution’s workforce in the internationalization makes it possible for these competences to be used in governance, scholarship, and pedagogy [5,13].

The curriculum is better able to support internationalisation from several perspectives. For students, it fosters global citizenship and constructive engagement with intercultural issues [11]. For academic staff, it addresses critical inclusive teaching, curriculum development, and intercultural teaching and learning [20,42]. At the micro-institutional level, CI supports the development of pragmatic and sustainable approaches that go beyond performative partnerships [8], especially with regard to SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) [10]. Academic staff with high CI are able to directly influence the transformational change of the institution [5,6].

There is a clear body of evidence that supports the link between CI and the enhancement of global learning opportunities. Academic research has shown a positive impact of international placements and inclusive pedagogy on international students [32,43,44]. Within this evolving literature, CI is increasingly recognised as a mechanism through which internationalisation can move from symbolic engagement toward culturally sustainable and ethically grounded practice [6,7], nurturing compassion, responsibility, and enduring partnerships.

In summary, CI is more than individual competency; it is a foundational element for profound and enduring internationalisation that is structural in nature [1,8]. Institutions that systematically integrate CI with all constituents are better positioned to cultivate global respect and CI [12,32].

H2:

Cultural Intelligence has a positive and significant effect on Internationalization in Higher Education.

1.1.4. Internationalization in Higher Education (IHE) and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS)

Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE) entails blending international or global dimensions into the aims, activities, and processes of postsecondary education [3]. In the context of globalization, it has increasingly become a means of enhancing academic competitiveness, knowledge diplomacy, and institutional viability [7,45]. It is now beyond just mobility and transnational education as IHE is also described as the fostering of intercultural social learning and social sustainability within academic communities [21]. Academic staff members are in a key position since their participation in international curricula, pedagogy, and collaboration contributes to shaping institutions’ intercultural learning climate [5,13].

IS refers to the ability to identify, comprehend, and respond appropriately to cultural differences [16]. It is a central component of inclusive and transformative internationalisation [46]. Cultural IS stems from a social position that has the greatest impact on international relations, which is the national level. Without IS, globalisation attempts are doomed to sustain cultural hierarchies and the silencing of minority narratives [47]. Faculty lacking IS are a danger (inadvertently) of exclusion through unresponsive cultural teaching or implicit biases [4].

Within this framework, internationalisation operates not merely as an institutional condition but as a structured learning environment through which sustained intercultural engagement and pedagogical practices facilitate the affective development of intercultural sensitivity [17,21].

Students and faculty IS development is influenced by policies combining experiential learning, multilingualism, and intercultural pedagogy [4,48]. IS furthers global citizenship and sustainable partnerships by lowering intercultural tensions and promoting mutual respect [49,50]. Professional development and intercultural training improve faculty IS in providing equitable and globally engaged learning environments [13,20].

From a sustainability perspective, IHE contextualised in intercultural sensitivity supports SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) [10]. IS functions as both an interpersonal competency and an institutional condition for equitable internationalisation. When incorporated in policy and pedagogy, it shifts from individual skill to organisational ethos [6].

In summary, IHE and IS create the base for social sustainability of the universities that are globally mobile and locally rooted [7,21,51]. This research examines how IS functions within internationalized higher education systems and how faculty development, curriculum design and inclusive teaching reinforce IS as a fundamental element of sustainable internationalisation [4,32,48].

Given that internationalisation structures sustained intercultural exposure through curricula, pedagogy, and professional practices, and that such exposure facilitates affective learning and reflective engagement, it is expected that internationalisation in higher education contributes directly to the development of intercultural sensitivity among academic staff and students.

H3:

Internationalization in Higher Education has a positive and significant effect on Intercultural Sensitivity.

1.1.5. The Mediating Role of Internationalization in Higher Education on Cultural Intelligence (CI) and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS)

The variation of Cultural Intelligence (CI) and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) has been covered in the literature concerning intercultural communication. Cultural Intelligence (CI) refers to the cognitive and behavioural capacities that enable individuals to function effectively across diverse cultural contexts, whereas Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) reflects the emotional ability to engage with cultural differences in an empathetic and respectful manner [1,16]. While both constructs support each other, their interaction has to do with contextual elements, particularly the operational framework of Internationalization in Higher Education (IHE), which serves an important intermediary role [21,36]. For academic staff, the provision of intercultural teaching, research, and collaboration is frequently the point of the conversion of CI to IS [13,20].

Internationalization functions as a developmental context through which individuals with higher cultural intelligence gain sustained intercultural exposure, thereby increasing their intercultural sensitivity. This perspective positions internationalisation in higher education not only as an institutional mechanism but also as a psychological and experiential pathway linking CI and IS [3,6,8].

Globalised curricula, international partnerships, and multicultural campus activities enable higher education institutions to serve as facilitators of students’ intercultural advancement [45,48]. Faculty members involved in international teaching or other development programmes tend to apply intercultural sensitivity (IS) at much higher rates than their counterparts [4,5]. Empirical studies confirm IHE’s mediatory function in enhancing the CI–IS connection. Research indicates that internationalized contexts, such as English as a Second Language programs and faculty exchanges, increase learning outcomes and intercultural competencies [32,52,53].

IHE integrates intercultural ethics and global competence into curricula, thereby facilitating emotional and intellectual development [6,46]. In this regard, this work defines IHE as a transformational institutional tool that defines the CI and IS gap [7,21]. It defines the institutional elements that promote internationalized curricula and intercultural engagement, generating attitudes of empathy, awareness, and responsibility among academic staff, and positioning them as enablers and active participants of this transformational process [4,5].

H4:

Internationalization in Higher Education has significant mediating effects on the relationship between Cultural Intelligence and Intercultural Sensitivity.

2. Materials and Methods

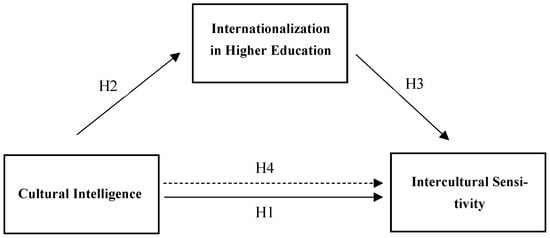

In analyzing how Cultural Intelligence (CI) impacts Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) and the Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE) mediation between them, a quantitative approach was used. A correlational survey strategy was used to collect the required data. A proposed model was designed based on the research question and the corresponding research hypotheses (Figure 1). A methodological approach was designed to create a conceptual model showing the proposed underlying relationships between the variables. The model attempts to measure the direct impact of CI on IS and examines the IHE as a mediating institutional process. Under this model, the assumption was that higher levels of cultural intelligence would mean higher levels of intercultural sensitivity, and that this appreciated relationship would be the outcome of partially internationalised higher education engagement.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

2.1. Samples

This research was designed to target full-time faculty working across all accredited universities in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). To enhance variety between institutions and to gain a wider scope of the internationalization of academics, a stratified random sampling technique was utilized. In the stratified sampling process, strata were explicitly defined based on academic rank, faculty type, and institution type (public, semi-public, and private). Two major determinants were used for stratification: rank and type of faculty. In this regard, the sample aimed for a broadly balanced representation of research assistants, lecturers, assistant professors, associate professors, and full professors.

At the stratified level, the type of faculty was used as a stratification criterion because of the higher international student enrollment in certain faculties, including engineering, health, and business. Faculty members in these areas are believed to have higher levels of contact and engagement with intercultural and cross-border professionally related activity, which in turn might be connected to the aspects of Cultural Intelligence (CI), Intercultural Sensitivity (IS), and Internationalization in Higher Education (IHE) in a theoretical framework.

Looking at the higher education framework of the TRNC, there is one fully public university, one semi-public university, and 21 private universities. The type of institution (public vs. private) was therefore explicitly incorporated as an additional stratification variable, ensuring proportional representation across institutional categories. Within each stratum, participants were selected using simple random sampling procedures, which were implemented to minimise sampling bias and enhance the representativeness and generalisability of the findings within the specific institutional and socio-political context of the TRNC.

Data collection was conducted from 11 to 21 November 2025. The questionnaire was distributed electronically via institutional email lists and shared through official academic communication platforms. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained prior to questionnaire completion. A total of 417 questionnaires were returned. Of these, 26 responses were excluded from further analysis due to incomplete or inaccurately completed questionnaires, resulting in 391 valid responses included in the final analysis. In total, 391 valid responses were collected and included in the final analysis. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Section 3.

Because the questionnaire was disseminated through institutional mailing lists and academic communication platforms, the exact number of faculty members who received the survey invitation could not be determined. Therefore, an exact response rate could not be calculated, and comparisons between respondents and non-respondents were not feasible; this issue is acknowledged as a methodological limitation.

A post-hoc power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 to assess the adequacy of the sample size. Assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) and a significance level of α = 0.05, the sample size of N = 391 yielded statistical power exceeding 0.95, indicating that the sample size was sufficient for detecting meaningful effects within the proposed structural model.

Table 1 illustrates the demographic profile of the 391 respondents to this particular study. Out of the total, 60.6% are males and 39.4% are females. The largest age group in the sample is 31–40 years old (33.2%), followed by 41–50 years (24.6%) and 21–30 years (24.3%). The least number of respondents are in the 51–60 years (10.2%) and above 60 years (7.7%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

The data also suggest that the majority of study participants were Research Assistants (26.9%) and Lecturers/Instructors (25.6%). In a downward trend in frequency, there were Assistant Professors (16.9%), Associates (16.4%), and Full Professors (14.3%). The largest group of respondents works in the Social Sciences and Humanities (23.3%), followed by Engineering and Technology (21.0%), Business and Economics (18.4%), Health Sciences (18.2%), and other faculties (19.2%).

Within the participants, 22.0% have 11–15 years of total working time. 21.2% have less than one year or 6–10 years of experience, while 19.2% have 1–5 years. 16.4% of participants have over 15 years of professional experience. On balance, the participants’ demographic profile suggests that the sample is reasonably well-spread, balanced by gender, age, academic position, and faculty position.

2.2. Measures

This part of the study analyzes the perceptions of the academics using the Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS), the Internationalisation Perception Scale for Academics (IPSA), and the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS).

The Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS) was developed to measure individuals’ ability to engage and interact effectively with people from different cultural backgrounds. The Turkish version of the scale was developed by İlhan and Çetin and verified the four-factor model of the original framework: Metacognition, Cognition, Motivation, and Behaviour [54]. The adaptation process followed standard translation and cultural adaptation procedures, including linguistic equivalence assessment and psychometric validation, as reported by the original adaptation study. The scale consists of four subscales, Metacognition, Cognition, Motivation, and Behavior, and has a total of 20 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale from (1) Strongly Disagree to (5) Strongly Agree. The reverse-scored items were excluded. The scale has good internal consistency with a 0.85, test-retest reliability of 0.81, and item total correlations from 0.33 to 0.64. Confirmatory factor analysis substantiated the Turkish version of the CQS as a valid and reliable tool for measuring cultural intelligence. In this research, the CQS was given to academic staff for a quantitative analysis of the participants on the cultural dimensions, as well as to assess their motivational and behavioral levels with respect to intercultural interactions.

The first version of the Internationalisation Perception Scale for Academics (IPSA) was developed to gauge internationalisation perceptions among academic peers regarding the processes and procedures of educational institutions [55]. The scale was based on theories proposed by Knight and by Dijk and Meijer, and it was developed through an exploratory sequential mixed-methods approach beginning with qualitative data [3,56]. The instrument has 33 items and four subdimensions: Policy, Implementation, Support, and Global Engagement. Respondents are asked to select one of five options on a Likert scale: 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). No items are reverse-coded. EFA (Exploratory Factor Analysis) results are consistent with a four-factor structure that together account for 84.6% of total variance. CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) provided evidence that the model was structurally valid and had an acceptable fit. The overall scale’s internal consistency coefficient was extraordinarily high at α = 0.985 and ranged from subdimension coefficients of 0.945 to 0.989. This evidence leads to the conclusion that IPSA is a valid and reliable measure of perceptions of internationalisation of higher education. The IPSA was selected for the present study because it is specifically designed to capture academics’ perceptions of institutional internationalisation processes, is theoretically grounded, and is particularly appropriate for higher education contexts in which internationalisation is shaped by institutional and policy-level dynamics [3].

The Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS) was developed to measure individuals’ sensitivity when interacting with people from diverse cultural backgrounds [2]. The scale comprises 24 items, and each is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). The scale was translated into Turkish by Üstün [57]. In this adaptation study, the author asserted that linguistic equivalence was achieved, and the psychometric properties of the scale were analyzed. A strong positive correlation was established for the English and Turkish versions (r = 0.82, p < 0.05), and the two versions were not significantly different from each other (t = 1.89, p > 0.05). Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) supported the initial five-factor structure and accounted for 63% of the total variance. The original form’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.88, while the Turkish version’s was 0.90. These results demonstrate that the ISS is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring intercultural sensitivity. The results also suggest that the Turkish version of the ISS is reliable and valid. Although the factor structure of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale has shown variability across different cultural contexts in previous studies, the Turkish adaptation demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties and preserved the original factor structure, supporting its suitability for use in the present study.

2.3. Data Analysis

Prior to conducting the main analyses, several preliminary procedures were undertaken to assess the suitability of the dataset for statistical evaluation. Data obtained from academic staff members were analysed using SPSS 26 and AMOS 24. Initially, the dataset was screened for missing values and response irregularities, and the normality of the variables and their distributions was assessed using skewness and kurtosis coefficients. All values were found to fall within the acceptable range of ±1.5, thereby satisfying the assumption of normal distribution. Participants’ gender, age, academic rank, faculty type, and total working time were summarised using frequency and percentage distributions.

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and intercorrelations among the study variables, were computed and are reported in Section 3. The mean values ranged from moderate to relatively high levels across all constructs, while standard deviations indicated acceptable variability. Skewness and kurtosis coefficients further confirmed univariate normality.

Bivariate correlation analyses revealed statistically significant and positive associations between Cultural Intelligence (CI), Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE), and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS), providing preliminary support for the hypothesised relationships. These findings justified the subsequent application of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM).

To assess the potential presence of common method variance (CMV), Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The unrotated exploratory factor analysis indicated that the first factor accounted for 26.23% of the total variance, which is well below the commonly accepted threshold of 50%. This result suggests that common method bias is unlikely to have substantially influenced the observed relationships.

Following confirmation of data suitability, the three instruments employed in the study—the Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS), the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS), and the Internationalisation Perception Scale for Academics (IPSA)—were subjected to validity and reliability analyses. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) results demonstrated acceptable model fit across widely reported indices (χ2/df, GFI, CFI, AGFI, NFI, RMSEA, and SRMR), thereby confirming the structural validity of the measurement models [58,59,60].

Prior to estimating the structural model, multicollinearity diagnostics were examined. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for the predictor variables were 1.181, with corresponding tolerance values of 0.847, indicating the absence of multicollinearity concerns. These values are well below the commonly accepted cut-off thresholds, confirming that the independent variables do not exhibit problematic intercorrelations.

After confirming the adequacy of the measurement models, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was employed to evaluate the proposed relationships among the variables. SEM was selected because it allows for the simultaneous estimation of direct, indirect, and mediating effects. The structural model’s fit indices were consistent with those of the measurement model, reinforcing the psychometric adequacy of the scales and confirming a strong correspondence between the theoretical and empirical models.

To evaluate the mediating effect of Internationalisation in Higher Education, a bootstrap procedure with 5000 resamples was applied. Bias-corrected 95% bootstrap confidence intervals were used to assess the significance of indirect effects.

2.4. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Cyprus Aydin University Ethics Committee (Approval No: 2025/11.001) on 11 November 2025. The study was reviewed and approved in accordance with the university’s ethical standards for research involving human participants. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

3. Results

Prior to testing the hypothesised relationships, descriptive statistics, normality indicators, and bivariate correlations among the main study variables were examined. Mean values, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis coefficients were calculated to assess the distributional properties of the data, while Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to explore preliminary associations between Cultural Intelligence, Intercultural Sensitivity, and Internationalisation in Higher Education.

As presented in Table 2, the mean scores indicate moderate to relatively high levels of Cultural Intelligence (M = 3.50, SD = 0.69), Intercultural Sensitivity (M = 3.77, SD = 0.66), and Internationalisation in Higher Education perceptions (M = 3.39, SD = 0.39) among academic staff. Skewness and kurtosis values for all variables fall within the acceptable range of ±1.5, suggesting that the assumption of normality was satisfied.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics, Normality Indicators, and Correlations Among Study Variables.

The correlation analysis revealed positive and statistically meaningful associations among all variables. Cultural Intelligence was moderately correlated with Intercultural Sensitivity (r = 0.502) and Internationalisation in Higher Education (r = 0.391). In addition, a moderate positive relationship was observed between Internationalisation in Higher Education and Intercultural Sensitivity (r = 0.541). The magnitude of these correlations remained below commonly accepted thresholds for multicollinearity, indicating that the variables were sufficiently distinct and suitable for subsequent structural equation modelling analyses.

3.1. Evaluating the Measurement Model

The results derived from Table 3 are sufficient to prove that the measurement instrument for the CQS (Cultural Intelligence Scale) variable is reliable and valid. Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated at 0.888, Composite Reliability (CR) was 0.967, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was 0.601. A Cronbach’s Alpha and CR scores that exceed 0.70 are deemed to reflect a high degree of internal consistency and reliability of the scale [61,62]. Also, an AVE score that is greater than 0.50 affirms the construct’s convergent validity. In addition, the factor loadings of 0.572 to 0.924, and all loadings exceeding 0.60, are ample construct validity [58]. This suggests that the CQS scale is reliable and valid in measuring the cultural intelligence of the respondents.

Table 3.

Reliability and Convergent Validity Analysis of CQS.

The results derived from Table 4 point out the reliability and the construct validity of the measurement of the variable IPSA (Internationalisation Perception Scale for Academics). Cronbach’s Alpha was found to be 0.822, Composite Reliability (CR) was 0.976, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was 0.554. Cronbach’s Alpha and CR scores beyond 0.70 attest to the scale’s internal consistency and reliability to be substantial [61,62]. An AVE score of more than 0.50 establishes that the construct has adequate convergent validity [58]. Also, all the factor loadings (0.517 to 0.880) suggest that all the items of the construct are significant to it, and scores above 0.50 are considered acceptable for convergent validity [58]. Therefore, it can be concluded that the IPSA scale has good reliability and validity for measuring the perception of internationalisation of the respondents.

Table 4.

Reliability and Convergent Validity Analysis of the IPSA Scale.

The outcomes in Table 5 provide evidence for the reliable and valid measurement of the ISS (Intercultural Sensitivity Scale) variable. The Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.921, the Composite Reliability (CR) was 0.964, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was 0.540. Cronbach’s Alpha and CR values that are greater than 0.70 demonstrate a substantial internal consistency and reliable scale for the measurement [61,62]. An AVE value that is greater than 0.50 provides evidence that the construct has adequate convergent validity [58]. Also, the factor loadings between 0.598 and 0.892 suggest that all the indicators on the latent construct are useful, as these values are above the 0.50 thresholds that are commonly accepted [58]. For these reasons, the ISS scale can be considered a valid and reliable measure of intercultural sensitivity for use with an academic audience.

Table 5.

Reliability and Convergent Validity Analysis of ISS.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on the entire dataset (N = 391) in order to validate the factorial structure of the measurement models in the main study. The purpose of the analysis was to determine the construct validity pertaining to the CQS (Cultural Intelligence Scale), ISS (Intercultural Sensitivity Scale), and IPSA (Internationalisation Perception Scale for Academics) scales by evaluating how the actual data aligned with the proposed measurement model. The model fit was assessed using standard goodness-of-fit criteria such as χ2/df, GFI, CFI, AGFI, NFI, RMSEA, and SRMR. Table 5 contains all the results of the CFA for each construct, and as it shows, the model fit results were sufficient, thus confirming the measurement instruments’ factorial validity.

The outcomes in Table 6 illustrate the results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the measurement models of CQS, IPSA, and ISS, pertaining to the main sample (N = 391). The model fit indices were considered based on the widely established criteria for sufficient and borderline sufficient model fit.

Table 6.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results.

In the case of the Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS), the result reveal the model fit is satisfactory: χ2/df = 2.76 (acceptable), GFI = 0.984 (good), CFI = 0.991 (good), AGFI = 0.934 (good), NFI = 0.945 (acceptable), RMSEA = 0.058 (acceptable), and SRMR = 0.0368 (good). These indicators strengthen the case that the measurement model for CQS has a robust and well-fitting factor structure.

The Internationalisation Perception Scale for Academics (IPSA) also shows a model fit at an acceptable level: χ2/df = 3.11 (acceptable), GFI = 0.921 (acceptable), CFI = 0.940 (acceptable), AGFI = 0.915 (good), NFI = 0.919 (acceptable), RMSEA = 0.072 (acceptable), and SRMR = 0.0697 (acceptable). All indices are within the acceptable fit range, showing that the IPSA model is a good fit for the data and adds support for the construct validity of the scale.

The ISS also returned reasonable scores: χ2/df = 2.82 (acceptable); GFI = 0.933 (acceptable); CFI = 0.947 (acceptable); AGFI = 0.918 (good); NFI = 0.945 (acceptable); RMSEA = 0.068 (acceptable); SRMR = 0.0581 (acceptable). Such scores suggest that the ISS model possesses a narrowly aligned configuration of the facets based on the theory. To put it concisely, the three scales: CQS, IPSA, and ISS, cumulatively affirm the acceptable to good fit levels. Thus, their factorial and structural validity is confirmed.

3.2. Evaluation of the Structural Model

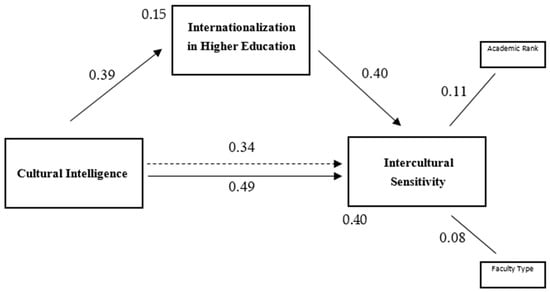

After confirming the validity and reliability of the measurement models, the structural model was set under examination. SEM was used to assess the model. It was used not only to measure the hypothesized interrelationships among latent variables, but also to measure the overall model fit. This is a multivariate technique, meaning several dependent relationships can be measured together in the proposed framework. The more complex the framework, the more intricate the dependencies among the variables. The analysis is complex, but so is the framework and the proposed relationships among the different variables. Figure 2 demonstrates the SEM results and is supported by the analysis in Table 7. The results support the model proposed, giving further evidence to the relationships among cultural intelligence, cultural sensitivity, and the perceptions held by academics toward internationalisation.

Figure 2.

Structural Model of the Proposed Research Framework.

Table 7.

Structural model results.

After the confirmation of the measurement model’s validity and reliability, the structural model was set under examination. A SEM analysis technique was used to assess the framework. This analysis offered the capability of directly measuring several proposed relationships simultaneously, defining latent variables and incorporating control variables to define external relationships.

Figure 2 and Table 7 highlight that all proposed routes were positive and significant in some manner. In H1, the respondent’s Cultural Intelligence (CI) was found to have a positive and direct effect on Intercultural Sensitivity (IS). This relationship was confirmed (β = 0.49, p < 0.001), suggesting that a higher level of cultural insight among the academics results in higher IS.

In H2, Cultural Intelligence (CIs) and Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE) were also positive. This means academics who have strong Cultural Intelligence are more likely to have positive attitudes about internationalisation in their institutions (β = 0.39, p < 0.001).

In the same manner, H3 proposed that Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE) would have a positive effect on Intercultural Sensitivity (IS). This too was confirmed (β = 0.40, p < 0.001) in suggesting that more involvement in internationalisation activities leads to greater awareness and responsiveness to other cultures.

Concerning H4 pertaining to the Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE) Mediating Impact on Cultural Intelligence (CI) and Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) Relationships, the findings indicate the presence of an indirect effect (β = 0.33, p < 0.001), which is statistically significant. This suggests that IHE partially mediates the relationship between CI and IS, which means that cultural intelligence, in addition to directly improving intercultural sensitivity, has an indirect effect that is carried through academics’ favorable views about the internationalisation of their institution.

In terms of explanatory power, the structural model accounted for a meaningful proportion of variance in the endogenous variables. Cultural Intelligence explained 15% of the variance in Internationalisation in Higher Education (R2 = 0.15), while the combined effects of Cultural Intelligence, Internationalisation in Higher Education, and control variables explained 40% of the variance in Intercultural Sensitivity (R2 = 0.40). These values indicate a moderate to substantial level of explanatory power for the proposed model within the context of social science research.

In addition, two control variables were incorporated in the model. Academic Rank has a statistically significant and positive effect on intercultural sensitivity (β = 0.11, p < 0.001), which means that the more senior an academic is, the more likely he or she is to display intercultural sensitivity and awareness, likely the result of wider international exposure and experience. In the same way, Faculty Type has a smaller but still statistically significant positive relationship to intercultural sensitivity (β = 0.08, p < 0.001), which suggests that the faculty context, particularly for those academics working in areas of high international student enrollment, stimulates their intercultural responsiveness.

In conclusion, these findings provide strong evidence for validating the proposed conceptual model, illustrating that cultural intelligence positively impacts intercultural sensitivity directly and through internationalisation in higher education.

Analysis of Total and Indirect Effects

To further examine the hypothesised mediating mechanism, a bootstrap-based analysis of the indirect effects was conducted. Table 8 presents the unstandardised indirect effect of Cultural Intelligence (CI) on Intercultural Sensitivity (IS) through Internationalisation in Higher Education (IHE), together with the associated standard error, 95% bootstrap confidence intervals, and significance levels.

Table 8.

Bootstrap Indirect Effect of CI on IS via IHE.

As reported in Table 8, the bootstrap analysis revealed a statistically significant indirect effect of Cultural Intelligence on Intercultural Sensitivity through Internationalisation in Higher Education (β = 0.15, 95% CI [0.096, 0.194], p < 0.001). The fact that the confidence interval does not include zero provides robust evidence for the mediating role of IHE. These findings indicate that Internationalisation in Higher Education partially mediates the relationship between CI and IS, suggesting that cultural intelligence is associated with higher levels of intercultural sensitivity not only through direct pathways but also indirectly via academics’ perceptions of and engagement with internationalisation practices within higher education institutions.

4. Discussion Conclusions and Recommendations

The results indicate a strong association between cultural intelligence and intercultural sensitivity, suggesting that academics with higher cultural intelligence tend to display greater affective openness and responsiveness in intercultural contexts [1,33]. The relative strength of this relationship may be attributed to the fact that both constructs primarily operate at the individual level and share closely aligned cognitive, motivational, and behavioural components that support intercultural engagement [14,23]. Intercultural sensitivity, encompassing empathy, openness, and tolerance towards cultural differences, has been consistently linked to lower bias and greater communicative flexibility among individuals with higher cultural intelligence [2,12,63]. However, given the cross-sectional design of the study, this association should be interpreted as relational rather than causal, as reciprocal or bidirectional influences cannot be ruled out [17]. An alternative explanation may involve self-selection effects, whereby academics who are already internationally oriented are more likely to report both higher cultural intelligence and greater intercultural sensitivity due to sustained exposure to diverse academic environments [26,64]. These dynamics appear particularly salient in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, where intercultural interaction constitutes a routine institutional condition rather than a mobility-driven or supplementary internationalisation practice [5,6,22].

The findings further indicate a meaningful association between cultural intelligence and internationalisation processes in higher education, suggesting that academics with higher cultural intelligence tend to engage more positively with institutional internationalisation practices [5,65]. The comparatively weaker strength of the CI → IHE pathway, relative to the CI → IS relationship, may be explained by the fact that internationalisation is shaped not only by individual competencies but also by organisational structures, policies, and access to institutional opportunities [3,26]. In this respect, cultural intelligence appears to function as a facilitating condition rather than a direct driver of institutional internationalisation. Given the cross-sectional design, this relationship should be interpreted as associative rather than causal, as internationally active institutions may also attract or retain culturally intelligent academics [66]. This interpretation aligns with evidence that internationalisation outcomes depend on the interaction between individual readiness and institutional capacity [67,68]. Such dynamics are particularly evident in the TRNC context, where internationalisation operates as a structural necessity shaping everyday academic governance rather than as a selectively implemented policy initiative.

The results indicate that higher levels of internationalisation in higher education are associated with higher levels of intercultural sensitivity, suggesting that sustained intercultural exposure within academic institutions is linked to greater affective openness and responsiveness [66,69]. The relative strength of this relationship may be explained by the experiential character of internationalisation practices, which provide repeated opportunities for intercultural interaction, reflection, and perspective-taking beyond purely cognitive engagement [17,70]. In this respect, internationalisation appears to operate as a social learning environment rather than solely as an administrative or policy-driven initiative [26,71]. However, given the study’s cross-sectional design, the observed association should be interpreted within an associative framework, as individuals with higher intercultural sensitivity may also be more inclined to participate in internationalised academic settings [2]. This alternative interpretation points to the possibility that both institutional exposure and individual predispositions jointly shape intercultural sensitivity [5,64]. These dynamics are particularly evident in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, where international interaction constitutes a routine component of academic life rather than a peripheral or mobility-centred experience, offering potentially transferable insights for similarly structured higher education systems.

The findings further indicate that internationalisation in higher education is associated with the relationship between cultural intelligence and intercultural sensitivity, reflecting a statistically supported mediating pattern. This pattern may be interpreted by considering internationalisation as a contextual setting in which individual cultural capacities are more likely to be expressed, practiced, and reinforced through sustained intercultural engagement [17,72]. Rather than functioning as a direct causal mechanism, internationalisation appears to provide structured social and academic environments that link individual cultural intelligence with affective and behavioural dimensions of intercultural sensitivity [5,26]. In this respect, the mediating role of internationalisation can be understood as conditional and context-dependent, shaped by both individual predispositions and institutional opportunities [66]. Given the cross-sectional nature of the study, the observed mediation should be interpreted cautiously, as alternative explanations such as the attraction of culturally oriented individuals to internationalised academic settings cannot be excluded [73]. These dynamics are particularly visible in the TRNC context, where internationalisation constitutes a routine institutional condition rather than a selectively implemented policy initiative.

In addition to the primary relationships, findings related to academic rank and faculty type suggest that intercultural sensitivity is also shaped by positional and disciplinary contexts within higher education institutions. Prior research suggests that senior academics are more likely to accumulate sustained international exposure through collaboration, mobility, and leadership roles, which may be associated with higher intercultural awareness over time [4,17,74]. Similarly, disciplines characterised by higher levels of international student engagement tend to offer more frequent opportunities for informal intercultural learning, which may support the enactment of intercultural sensitivity in everyday academic practice [5,6,11]. These patterns should not be interpreted causally, particularly given the cross-sectional design of the study, and alternative explanations such as the self-selection of internationally oriented academics into more internationalised faculties cannot be excluded [7,26]. From a theoretical perspective, these subgroup-related findings reinforce the view that internationalisation functions as a contextual mechanism through which individual cultural intelligence is more likely to be translated into intercultural sensitivity, rather than as a direct causal driver. Accordingly, universities are encouraged to adopt targeted policies such as discipline-specific faculty development, structured intercultural mentoring for early-career academics, and the integration of intercultural learning objectives into teaching and promotion criteria [5,21].

Cultural intelligence and internationalization in higher education collaborate to demonstrate how intercultural competencies are reshaping global engagement in academia. In this sense, higher education institutions in the TRNC are required to rethink internationalization as more than a checklist to tick, and more as an inclusive, participatory, iterative goal. Incremental, and more accessible, faculty-led, virtual exchange programs, co-created global curricular, and international joint research mentoring programs are some of the other scalable and structured initiatives to facilitate intercultural learning. These initiatives also enhance equity in internationalization by enabling participation of more non-elites beyond a restricted academic circle [6,11,26].

Another major finding of this study is that internationalization itself contributes to enhancing intercultural sensitivity, functioning as a social learning mechanism. Academic leaders are recommended to formally, systematically, and strategically link these by incorporating intercultural learning outcomes into course syllabi, expanding cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary teaching teams, and micro-credentialing on global citizenship and cultural literacy. Instead of framing these as optional, they should be treated as key components of graduate transferable skills and academic quality and rigor [5,17,21].

The statistically significant effects derived from rank and faculty type on intercultural sensitivity further highlight the need for equitable capacity-building. Focused activities, such as intercultural mentoring for junior scholars and the establishment of professional learning communities in STEM, can help mitigate inequities and foster more inclusive academic environments. Furthermore, the academic development divisions of universities should also integrate intercultural competence as a fundamental element in instructional advancement and strategic faculty development [4,13,20].

At the institutional level, these findings call for the formalisation of intercultural competence within university governance and quality assurance mechanisms. Universities in the TRNC may operationalise this by embedding intercultural competence indicators into academic promotion and performance evaluation criteria, mandating periodic intercultural professional development for faculty members, and allocating dedicated budget lines for faculty-led internationalisation-at-home initiatives. In addition, the establishment of institution-wide intercultural coordination units or designated faculty-level intercultural leads could ensure the systematic implementation, monitoring, and sustainability of these policies across disciplines. Such measures would move intercultural competence from an aspirational objective to an accountable and measurable component of institutional strategy.

Building on this governance-oriented framework, universities may further support implementation through targeted and scalable practices. Each faculty may designate an intercultural leadership representative trained to mobilise colleagues and embed intercultural initiatives into daily academic practice. Complementary mechanisms such as global classroom fellowships and cross-cutting micro-grant schemes may support curriculum internationalisation and interdisciplinary collaboration [3,8,32].

Taken together, these measures illustrate how internationalisation may be operationalised as a coherent institutional system rather than a symbolic or fragmented set of practices, thereby strengthening the socially responsible dimension of sustainability in higher education [5,6,22]. Appreciating cultural diversity within academia and enhancing innovation at the institutional level can substantially reduce the ethical, pedagogical, and developmental gaps to be addressed in globalized contexts of higher education [5,6].

This study is subject to certain limitations that should be acknowledged. As the data were collected through self-report instruments, the findings may be influenced by response-related biases, including social desirability bias and tendencies toward extreme or neutral response patterns. In addition, acquiescence or dissent bias may have affected participants’ responses. Although these limitations do not undermine the overall validity of the results, they should be considered when interpreting the findings and addressed more explicitly in future research through the use of mixed methods or complementary data sources. This study contributes to understanding how internationalization practices relate to faculty intercultural competence. Future research should employ longitudinal or experimental designs to examine developmental processes and to explore institutional conditions that strengthen or weaken the CI-IHE-IS pathway.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y., T.G. and M.Y.K.; methodology, A.Y. and M.Y.K.; software, M.Y.K.; validation, T.G. and M.Y.K.; formal analysis, M.Y.K.; investigation, A.Y., T.G. and M.Y.K.; resources, A.Y. and M.Y.K.; data curation, A.Y. and M.Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y., T.G. and M.Y.K.; writing—review and editing, A.Y., T.G. and M.Y.K.; visualization, A.Y. and M.Y.K.; supervision, T.G. and M.Y.K.; project administration, A.Y., T.G. and M.Y.K.; funding acquisition, A.Y., T.G. and M.Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Cyprus Aydin University. The approval was granted in the 11 November 2025 meeting, and the approval number is 2025/11.001.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors received no specific support beyond the contributions mentioned above.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI | Cultural Intelligence |

| IS | Intercultural Sensitivity |

| IHE | Internationalization in Higher Education |

References

- Ang, S.; Van Dyne, L.; Koh, C.; Ng, K.Y.; Templer, K.J.; Tay, C.; Chandrasekar, N.A. Cultural Intelligence: Its Measurement and Effects on Cultural Judgment and Decision Making, Cultural Adaptation and Task Performance. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2007, 3, 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.M.; Starosta, W.J. The Development and Validation of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale; Howard University: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED447525 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Knight, J. Internationalization Remodelled: Definition, Approaches, and Rationales. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2004, 8, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen-Hermans, J. Intercultural Competence Development in Higher Education. In Intercultural Competence in Higher Education; Deardorff, D.K., Arasaratnam-Smith, L.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.; Whitsed, C. (Eds.) Critical Perspectives on Internationalising the Curriculum in Disciplines: Reflective Narrative Accounts from Business, Education and Health; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, B. Internationalizing the Curriculum; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit, H.; Hunter, F. The Future of Internationalisation of Higher Education in Europe. Int. High. Educ. 2015, 83, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, U.; de Wit, H.; Jones, E.; Leask, B. Defining Internationalisation in Higher Education for Society; University World News: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190626135618704 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- de Wit, H. Internationalisation of Higher Education in Europe and Its Assessment, Trends and Issues; European Association for International Education (EAIE): Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Cooperation Association (ACA): Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Jones, E.; Killick, D. Graduate Attributes and the Internationalized Curriculum: Embedding a Global Outlook in Disciplinary Learning Outcomes. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2013, 17, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D. Leading with Cultural Intelligence: The Real Secret to Success; AMACOM: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov, N.; Dawson, D.L.; Olsen, K.C.; Meadows, K.N. Developing the Intercultural Competence of Graduate Students. Can. J. High. Educ. 2014, 44, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P.C.; Ang, S. Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne, L.; Ang, S.; Ng, K.Y.; Rockstuhl, T.; Tan, M.L.; Koh, C. Sub-Dimensions of the Four-Factor Model of Cultural Intelligence. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2012, 6, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M.; Bennett, M.J. Developing Intercultural Sensitivity: An Integrative Approach to Global and Domestic Diversity. In Handbook of Intercultural Training; Landis, D.R., Ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; p. 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D.K. Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2006, 10, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manera, A.; Dulay, M.; Liquigan, M.L.; Milanes, S.; Pagay, L.A.; Barotas, L. From Classroom to Community: Using AI to Foster Intercultural Dialogue and Global Citizenship Education. Int. J. Cult. Hist. Relig. 2025, 7, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonfeld, M.; Abu Ahmad, M.Y.; Liverant, R.C.; Amichai-Hamburger, Y. Reducing Technological Anxiety through Intercultural Competence. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L.T.; Dempsey, K. (Eds.) Internationalization in Vocational Education and Training: Transnational Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, B.; Bridge, C. Comparing Internationalisation of the Curriculum in Action across Disciplines: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives. Compare 2013, 43, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Leask, B.; Brandenburg, U.; de Wit, H. Global Social Responsibility and the Internationalisation of Higher Education for Society. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2021, 25, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.-Y.; Van Dyne, L.; Ang, S. Developing Global Leaders: The Role of International Experience and Cultural Intelligence. In Advances in Global Leadership; Mobley, W.H., Wang, Y., Li, M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 5, pp. 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, O.E. Multicultural Competence: An Empirical Comparison of Intercultural Sensitivity and Cultural Intelligence. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2019, 13, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racicot, B.M.; Ferry, D.L. The Impact of Motivational and Metacognitive Cultural Intelligence (CQ) on the Study Abroad Experience. J. Educ. Issues 2016, 2, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelen, J.; Jones, E. Redefining Internationalization at Home. In The European Higher Education Area; Curaj, A., Matei, L., Pricopie, R., Salmi, J., Scott, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T. Beyond Culture; Anchor Press: Garden City, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Butac, S.; Manera, A.; Gonzales, E.; Paller, R.; Eustaquio, M.T.; Tandoc, J.J. Forging Global Citizens: A Comparative Study of Intercultural Pedagogical Practices of Higher Educational Institutions in the Philippines. Int. J. Cult. Hist. Relig. 2025, 7, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, D.R.; Huang, A.; Avalos, A.R. Willingness to Learn: Cultural Intelligence Effect on Perspective Taking and Multicultural Creativity. Int. Bus. Res. 2018, 11, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.Z.; Iqbal, J.; Özbilen, F.M.; Abedin, J.; Järvenoja, H.; Widanapathirana, U. The Nexus of Artificial Intelligence Literacy, Collaborative Knowledge Practices and Inclusive Leadership Development among Higher Education Students in Bangladesh, China, Finland and Turkey. Discov. Comput. 2025, 28, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Montoya, M.-S.; Hernández Montoya, D.; Zavala, G.; Montoya, M.A.; Martínez-Arboleda, A. Building the Future of Education Together; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.C.; Elron, E.; Stahl, G.K.; Ekelund, B.Z.; Ravlin, E.C.; Cerdin, J.-L.; Poelmans, S.; Brislin, R.; Pekerti, A.; Aycan, Z.; et al. Cultural Intelligence: Domain and Assessment. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2008, 8, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainio, E.; Escurra Ferreira, L. Becoming Competent for the Globalized World; Laurea University of Applied Sciences: Vantaa, Finland, 2025; Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/897590 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Butal, R.J.; Cañete, E. The Mediating Effect of Cultural Identity between the Relationship of Intercultural Sensitivity and Cultural Competence of Elementary Teachers. Int. J. Multidiscip. Educ. Res. Innov. 2026, 4, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y. SNS-Based Intercultural Contact in an EMI Context: Fostering EFL Learners’ Motivation and Intercultural Competence. J. Asia TEFL 2025, 22, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.D.; Noels, K.A. Cultural Empathy in Intercultural Interactions: The Development and Validation of the Intercultural Empathy Index. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2024, 45, 4572–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañez, R.M.; Arañez, R.M.; Veneranda, J.M.B.; Veneranda, J.M.B. Fostering Cross-Cultural Understanding through Southeast Asian Multicultural Literature: Insights from Preservice ESL Teachers’ Learning Experiences. Community Soc. Dev. J. 2025, 26, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.; Van Dyne, L. Handbook of Cultural Intelligence; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.J. Toward Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity. In Education for the Intercultural Experience; Paige, R.M., Ed.; Intercultural Press: Yarmouth, ME, USA, 1993; pp. 21–71. [Google Scholar]

- Orduna-Nocito, E.; Sánchez-García, D. Aligning Higher Education Language Policies with Lecturers’ Views on EMI Practices: A Comparative Study of Ten European Universities. System 2022, 109, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dela Cruz, L.; Manera, A.; Ramirez, E.; Macato, D.; Catbagan, R.J.I.; Tulawie, A. Bridging cultures in the classroom: Analyzing pedagogical approaches that promote intercultural competence in multicultural higher education settings. Int. J. Cult. Hist. Relig. 2025, 7, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvilhaugsvik, B.; Almås, S.H.; Aasen, U.M.U. Internationalisation in Norwegian Health and Social Care Curricula: A Document Analysis. Læring Læring 2025, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. Designing an Inclusive Game-Based Framework for Enhancing Chinese Students’ Teamwork in UK Engineering Programmes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2025. Available online: https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/37575/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Wächter, B.; Maiworm, F. English-Taught Programmes in European Higher Education: The State of Play in 2014; Lemmens Medien GmbH: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pastena, A. Intergroup Contact and Intercultural Sensitivity among First-Year Undergraduates in an Internationalised Classroom in Europe: An Exploratory Mixed-Method Study. Intercult. Educ. 2025, 36, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithole, N.V.; Khohliso, X. Western Dominance vs. Local Needs: Mismatches in Internationalised Teacher Training Curriculum in South Africa. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2025, 24, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. Emotion Expression, Regulation and Psychological Outcomes among Highly Sensitive Adolescents in Internationalised Education Contexts. J. Psychol. Hum. Behav. 2025, 2, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariyono, D.; Alifatul Kamila, A.N. Unity in Diversity: Navigating Global Connections through Cultural Exchange. Qual. Educ. All 2025, 2, 114–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enamhe, D.; Ambe, B.; Enamhe, P. Intercultural Competency in a Globalized World: Preparing Learners for Effective Global Citizenship. Transdiscip. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. Stud. 2025, 1, 118–127. Available online: https://tjesds.org.ng/index.php/home/article/view/9 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Liu, J.; Gao, Y. Higher Education Internationalisation at the Crossroads: Effects of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2022, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Norlizah, C.H.; Muhamad, M.; Zhang, S. Empowering STEM Educators in Cross-Cultural Higher Education Contexts: Professional Development Strategies for Sustainable Workforce Readiness. STEM Educ. 2025, 5, 954–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Q.; Li, S.; An, R.; Yasmin, F.; Akbar, A. Deep Learning as a Bridge between Intercultural Sensitivity and Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study of English-Medium Instruction Delivery Modes in Chinese Higher Education. Acta Psychol. 2025, 259, 105410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İlhan, M.; Çetin, B. Validity and Reliability Study of the Turkish Version of the Cultural Intelligence Scale. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. 2014, 29, 94–114. [Google Scholar]

- Taşçı, G. Yükseköğretimde Uluslararasılaşma: Türkiye Örneği (1995–2014). Ph.D. Thesis, Marmara University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2018. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezDetay.jsp?id=xXBHsoXqDdKQ8gyXf5BOEQ&no=66cF4qZHuCsFDLZAJTAvsg (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Dijk, V.; Meijer, B. The Internationalisation Cube: A Tentative Model for the Study of Organisational Designs and the Results of Internationalisation in Higher Education. High. Educ. Manag. 1997, 9, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Üstün, E. Öğretmen Adaylarının Kültürlerarası Duyarlılık ve Etnikmerkezcilik Düzeylerini Etkileyen Etmenler. Master’s Thesis, Yıldız Teknik University, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2011. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezDetay.jsp?id=P3EZ4hzGVrNNba2YDFkE8A&no=N8QBwMXLU9bGERQgM7E3WQ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzberg, B.H.; Changnon, G. Conceptualizing Intercultural Competence. In The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence; Deardorff, D.K., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 2–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, S.; Almeida, J.; Schartner, A. Internationalization at Home: Time for Review and Development? Eur. J. High. Educ. 2018, 8, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, M.; Lisak, A.; Harush, R.; Glikson, E.; Nouri, R.; Shokef, E. Going Global: Developing Management Students’ Cultural Intelligence and Global Identity in Culturally Diverse Virtual Teams. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2013, 12, 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]