Abstract

In recent years, long-term vehicle rental has gained importance as a flexible and cost-effective mobility solution. This model reduces the high initial costs associated with vehicle purchases, ensures predictable expenses through fixed monthly payments, reduces the risk of depreciation, and enables systematic fleet renewal, supporting its adaptation to changing environmental regulations and technological advancements. This paper proposes a tool to support the process of selecting propulsion technologies in long-term rental fleets, taking into account their economic, technical, environmental, and social implications for sustainable fleet management. The developed procedure combines secondary fleet data analysis, expert research conducted among service providers, and multi-criteria analysis conducted using the Analytic Hierarchy Process method. The results indicate that under current conditions in Poland, combustion vehicles remain the optimal solution for fleet operators, while electric vehicles—despite their environmental benefits and additional benefits—remain the least competitive. The proposed approach is comprehensive, adaptable, and easy to implement, providing a practical tool for fleet operators and end users. The results also provide guidance for public decision-makers on strengthening the market position of low- and zero-emission vehicles.

1. Introduction

Managing in accordance with the principles of sustainable development requires making rational and balanced decisions. Balancing social, economic, and environmental aspects should be based on reliable analyses that take into account a wide range of issues.

Every decision-making process is multi-criteria in nature due to the complexity and intricacy of the decision-making situation. The choice of a solution is often simplified by reducing the decision-making process to a single criterion (usually costs or benefits), which allows for quick, but not always correct, decisions [1]. Applying a single criterion in sustainable development is unacceptable, therefore selecting the optimal solution is complex and complicated. One proposal is the use of multi-criteria analyses, which create a set of interrelated criteria that enable the creation, justification, and transformation of preferences in the decision-making process [2].

Multi-criteria decision support (MCDM) is a dynamically developing field of knowledge, originating from operations research. Its goal is to equip decision makers (DMs) with modern methodological tools that allow them to efficiently solve complex decision-making problems in which different, often conflicting, points of view/interests must be taken into account [3,4].

Unlike classical operations research techniques, multi-criteria decision support methods do not allow for determining a single, unambiguously best solution to a given decision problem. Finding a solution that would be best from multiple perspectives simultaneously is simply impossible. Hence, multi-criteria decision support methods employ concepts such as the Pareto-optimal solution, also called the efficient or non-dominated solution, or the compromise solution [2,3]. The origins of multi-criteria decision support methods date back to the 1950s. It was then that the concept of efficient/non-dominated solutions was introduced, and the first multi-objective vector maximization problems were formulated mathematically (T. Koopmans, H. Kuhn, and A. Tucker—1951) [5].

Multi-criteria decision support methods have developed in two basic directions, creating two distinct schools of decision support: the American and European schools.

The first group of methods, based on the outranking relation, originated in France, laying the foundations for the European multi-criteria decision support methods school. B. Roy is considered the founder of this school. The essence of these methods lies in modeling the decision-maker’s preferences using the so-called outranking relation, which allows for the occurrence of incomparability between alternatives, i.e., a situation in which the decision-maker is unable to identify the better of two alternatives [2]. Examples of methods from this group include Electre I-IV.

The second group of methods, originating from the American tradition (e.g., R.L. Keeney and H. Raiffa, 1993), is based on multi-attribute utility theory. The essence of these methods is the construction of a single additive or multiplicative utility function, obtained through the transformation and scaling of criteria to make them mutually comparable. In this sense, these approaches do not ignore the issue of incomparability but resolve it by adjusting the criteria and expressing them in a common preference scale, which then allows the optimization of the aggregated utility function. Typical representatives of this group are the UTA (French: Utilite Additive) or AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) methods [3].

1.1. Features of the AHP Method

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), a widely used multi-criteria decision-making method, was proposed by T. Saaty in 1980. This method utilizes the principles of multi-attribute utility theory and allows for the decomposition of a complex decision problem, leading to the ordering of a finite set of decision variants [6]. It is based on a hierarchical approach to multi-criteria decision-making, combining quantified and non-quantified criteria and objectively measurable and subjective criteria. It is useful in cases where the functional relationship between the elements of a decision problem described in the form of a hierarchy of objectives is unknown, but the effect of data occurrence and their practical impact can be estimated [7].

The AHP method is based on three basic rules: the structure of the decision problem is presented in the form of a hierarchy of objectives, criteria, subcriteria and variants, preference modeling is performed by pairwise comparison of elements at each level of the hierarchy, and the ranking of variants is performed by synthesizing preference assessments from all levels of the hierarchy [8,9,10].

The AHP algorithm operation process can be divided into four stages:

Stage 1: Building a hierarchical model.

Stage 2: Evaluation through pairwise comparison. Collecting pairwise comparison scores for criteria and decision options using the relative dominance scale adopted in the AHP method.

Stage 3: Determining global preferences. Determining the relative priorities (importance) of the criteria and decision options.

Stage 4: Final ranking of decision options.

The basis of the AHP method is a hierarchical tree structure representing the structure of the decision problem—stage 1. The hierarchical structure of the decision problem is divided and includes the goal of the decision process, criteria, subcriteria for evaluation, and options to be evaluated. The overarching goal of the decision process is assigned to level 0. Level 1 contains the criteria and subcriteria for evaluating options, and level 2 contains the decision options.

Stage 2 involves determining the subjective preferences of the decision maker and intervenors and expressing them in a manner characteristic of the AHP method [11]. At this stage, relative importance ratings are defined at each level of the hierarchy on a standard AHP rating scale of 1–9 points, respectively, for pairs of criteria, subcriteria, and decision options, creating quadratic preference matrices at each level of the hierarchy [12]. Equivalent elements, characterized by equal importance, receive a rating of 1. An extreme value of −9 is assigned to an element that has an extremely strong advantage over the other element being compared. Intermediate values reflect the proportional intensity of the relative advantage of one element over the other. All coefficients are compensatory in nature, meaning that the rating value for the less important (less preferred) element in a given pair is the inverse of the value assigned to the more important (more preferred) element.

On this basis, the pairwise comparison matrix Ω = [ωk′k]K×K is constructed, in which each element ωk′k indicates the relative advantage of criterion k′ over criterion k. The elements on the diagonal satisfy the condition ωkk′ = 1, which reflects the fact that each criterion is equally important relative to itself. The values in the matrix are related to each other in a way that maintains consistency of evaluations: if the comparison of criterion k′ with respect to k has the value ωk′k, then the reverse comparison is equal to ωkk′= 1/ωk′k. This relationship of the matrix elements reflects the principle that the less preferred alternative receives the opposite rating to that assigned to the more preferred element, i.e.,

where ωk’k—assessment of the advantage of the k-th criterion over the k’-th.

Next, for each matrix of relative importance ratings, the eigenvalue search problem [12] is solved, which ultimately yields a vector of normalized, absolute importance ratings for criteria, subcriteria, and variants. After establishing the preference matrix, the results are normalized across columns and summed across rows.

Stage 3 examines the global consistency of the matrix at each level of the hierarchy, i.e., examines the extent to which the preferential information provided by decision-makers in Stage II is consistent with the criteria, subcriteria, and alternatives. The reliability and consistency of the assessments are verified by calculating one of two indices: the consistency index (CI) and/or the consistency ratio (CR), which are calculated according to (5) and (6), respectively.

The calculation of the consistency index requires multiplying two components: the pairwise comparison matrix Ω = [ωk′k]K×K and the priority vector of the decision criteria W = [wk]K×1. The weights wk are derived from the normalized principal eigenvector of the matrix Ω. In practical terms, each weight wk can be computed as the average of the normalized values in the corresponding column of the matrix, where

Then the result of the product is divided by the priority for each criterion, and then the average of these values is determined, which allows us to obtain the λ index and, together with the RI index reading, to determine the CR consistency index:

ΩW = C = [ck]K×1

CI—coherence index,

K—number of compared criteria (or variants),

RI—random index, which would be obtained for K elements, for which the comparison would be made completely randomly [12,13].

The importance ratings for hierarchy elements are more consistent the lower the calculated consistency index values. If the CR and the associated CI values at each hierarchy level are equal to 0, the preferential information provided by decision-makers at those levels is perfectly consistent. If the CR index exceeds the allowable value (CR > 0.1), then it is necessary to verify the preferential information provided by decision-makers, as it is characterized by excessive inconsistency. In such a situation, the AHP algorithm returns to Phase II.

The decision-making procedure using the AHP method, which aims to construct a final ranking and identify a rational arrangement of alternatives, is described in detail in [14,15,16].

1.2. Application of the AHP Method—Literature Review

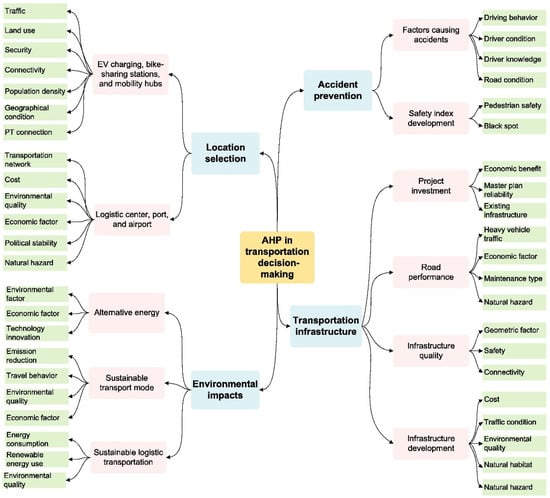

The AHP method has been used in many areas, both in its classic and modified form, including the higher education sector [17], the health sector [18], IT [19], energy [20], manufacturing [21], ecology [22], and transport. As the authors of [23,24] prove, it is currently the most frequently used multi-criteria decision support method in this area, primarily in the selection of infrastructure location, assessment of investment options, safety and environmental impact (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of the most important factors of AHP decision-making in the field of transportation [23].

An important area of research on the use of the AHP method in transport is the identification and assessment of factors influencing the risk of road accidents [25,26,27,28,29,30]. Due to the dominant role of human factors in their occurrence, the authors [31,32] defined key areas of knowledge in the field of road safety. They indicated that drivers should be specifically trained in behavior in specific road situations, such as overtaking maneuvers, navigating roundabouts, as well as awareness of the risks of driving under the influence of alcohol, speeding, and the need-to-know emergency numbers.

Safety issues are also analyzed in the context of maritime transport. In [33,34] it was shown that human factors and meteorological conditions are crucial in the case of maritime accidents. Meanwhile, in [35] it was proven that training in teamwork culture plays a key role in preventing maritime incidents caused by human errors.

In addition to safety aspects, a significant area of application of the AHP method in transport is location issues, which require consideration of many diverse criteria. As evidenced by the literature review, the AHP method is widely used in urban mobility research, particularly in selecting locations for electric vehicle (EV) charging stations [36,37,38,39,40], bike-sharing points [41,42], and mobility hubs [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

The AHP method is also widely used to prioritize criteria and support investment decisions in transport. Many authors emphasize that multi-criteria analysis, including AHP, better reflects the preferences and objectives of decision-makers than classic cost–benefit analysis [53,54]. In the context of infrastructure project evaluation, particular importance is attached to economic benefits and efficiency [55,56,57]. In research on the design and modernization of transport networks, infrastructure reliability and compatibility with existing public transport systems are crucial [58,59]. Damage levels and economic factors are crucial when establishing repair priorities [60], while traffic volume is crucial in pavement management [61]. Other studies point to the importance of lighting quality, cleanliness, and pedestrian infrastructure [62]. When planning forest transport routes, it is also necessary to consider natural factors, such as terrain slope, soil structure, and landslide risk [63].

Planning the development of transport infrastructure requires the identification of risk factors and setting priorities. The most important include public transport frequency [64], road traffic volume and composition [65], as well as political and legal risks in urban rail projects [66] and public–private partnerships for electromobility [67]. Technical risks [68,69], costs [70], as well as the potential for obtaining EU funds [71] and the availability of financial resources, particularly in developing countries [72]. In capital-intensive projects, such as the construction of freight corridors, increasing capacity is crucial [73], while when selecting a contractor—in addition to costs—experience and quality are taken into account [74].

Another important area of research in which the AHP method has been widely applied is the selection of the most appropriate strategies, technologies, or solutions to reduce the negative environmental impacts of transport activities. One of the most frequently analyzed issues in this context is the identification of optimal energy sources and alternative fuels in transport. The authors of [75] compared ammonia and hydrogen as fuels for maritime navigation, pointing to the former’s greater environmental sustainability. A study on public transport in Istanbul [76] identified compressed natural gas as the most favorable fuel option for city buses. Interesting conclusions were presented in [77], which prioritized environmental criteria over economic ones when evaluating alternative fuels for aircraft. However, as noted in [78], in practice, airlines are more likely to consider aircraft price than their environmental impact, such as emissions or noise.

In the transport of end-of-life goods, the AHP method was used in [79] to select the most cost-effective methods of collecting used tires, indicating the effectiveness of collecting them locally after pre-processing.

With respect to road transport, ref. [80] analyzed the environmental impact of various modes of transport and concluded that the most important factors are the potential for emission reduction and the efficiency of energy resource use. Ref. [81] emphasized that a clean environment and changes in travel behavior are crucial for the development of a sustainable transport system. However, other studies indicate that operational efficiency [82] or economic criteria [83] often have a greater impact than environmental considerations. Despite this, tax policies promoting eco-friendly modes of transport are considered the most effective policies for mitigating climate change [84]. According to [85], sustainable transport also contributes to reducing negative impacts on public health and mitigating the urban heat island effect. Other studies indicate that air pollution and noise should be key criteria for selecting a mode of transport, especially in densely populated areas [86]. To reduce road noise, the use of asphalt mixtures with added rubber and acoustic barriers [87] and limiting the speed and movement of heavy goods vehicles [88] are proposed. In rural areas, rail transport is considered a more sustainable alternative to investing in road transport [89].

Despite the wide range of applications of the AHP method in transport, no studies have been reported to evaluate fleet vehicle propulsion options in the context of long-term rental services, while taking into account criteria relevant to both operators and end users.

In light of the considerations presented above, the aim of this research is to carry out a multi-criteria evaluation of vehicles with different types of drives, i.e., combustion (a vehicle with a spark ignition engine (SI), a vehicle with a compression ignition engine (CI), hybrid (PHEV—Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle, MHEV—Mild Hybrid Electric Vehicle) and electric (BEV—Battery Electric Vehicle), from the perspective of the long-term rental operator and customers of such services.

The technological structure of vehicle fleets has a direct impact on emissions, energy consumption, and air quality in cities. Long-term rentals are playing an increasingly important role in transforming the vehicle market, and fleet operators’ decisions are crucial for achieving climate policy goals. The choice of drive type affects not only operating costs but also carbon footprint and compliance with environmental regulations. Therefore, assessing drive options using a multi-criteria approach is an important element of sustainable mobility management and can support decision-making processes at both the operational and strategic levels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Purpose of Research

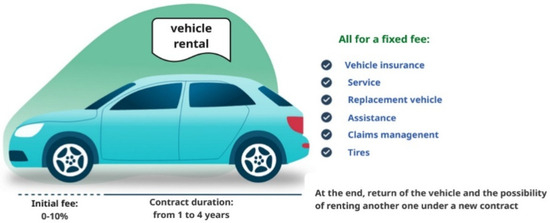

From a legal and formal perspective, long-term rental is a leasing agreement with a high buyout of the used vehicle and additional services included in the monthly payment. Under a long-term rental agreement, the user uses the leased vehicle for the entire duration of the agreement (at least 12 months), returning it to the rental company at the end. The costs incurred by the lessee during the agreement period include only the cost of fuel or energy, while all other costs related to vehicle use are included in the monthly payment (Figure 2) [90]. A significant advantage of long-term rental is the simplicity of the procedure and minimal formalities associated with renting a vehicle—many companies offer online contract conclusion [91].

Figure 2.

Long-term vehicle rental.

2.2. Subject of Research

The passenger vehicles used in this research were produced in 2024, belong to the market segment C (compact car segment) and represent different drive variants of the same model and brand V = {vi: i = 1, 2, …,5}, namely:

- v1—a vehicles with an electric engine (BEV).

- v2—a vehicle with a hybrid drive (MHEV).

- v3—a vehicle with a plug-in hybrid drive (PHEV).

- v4—a vehicle with a spark ignition engine (SI).

- v5—a vehicle with a compression ignition engine (CI).

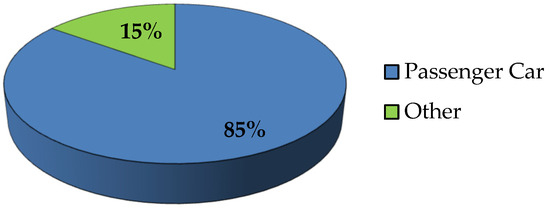

The author identified the vehicles for the study based on secondary research he conducted in 2025 among long-term rental operators operating in Poland. Based on this research, it was determined that in 2024, the number of vehicles offered as part of long-term rental services was over 270,000, the vast majority of which were passenger cars (Figure 3), including Skoda, Toyota, Kia, and Hyundai vehicles.

Figure 3.

Poland vehicle rental market share, by vehicle, 2024 [92,93].

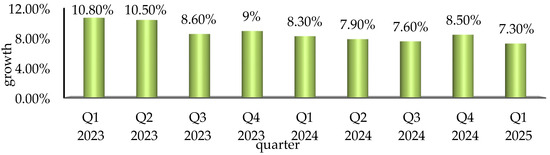

The Polish long-term rental market was not chosen by chance. Its systematic development has been observed for many years. This is confirmed by data for the first quarter of 2025. Fleet operators purchased and registered 6.7% more new vehicles than a year earlier, and the number of cars they rented during the same period increased by 7.3% year-on-year [93] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Year-on-year growth rate of the long-term car rental in Poland (total number of vehicles) [93].

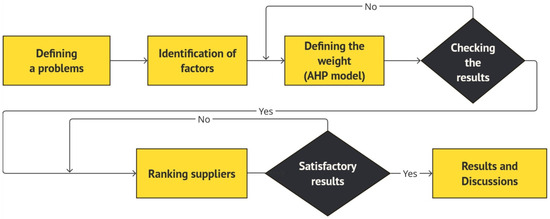

The analysis considered a set of criteria for evaluating the v-th variant: economic, technical, environmental, and social, which are important from the perspective of vehicle fleet managers and customers. Based on this, a tool was proposed to support the selection of optimal vehicles, the structure of which is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Procedure for assessing vehicles used in long-term rental systems.

The developed solution is comprehensive, reflecting various aspects related to vehicle selection. It is flexible, allowing it to be used for various vehicle classes, tailored to the specific needs of long-term rental companies. It is also simple and quick to implement. It can therefore serve as a practical tool for both current and future long-term vehicle rental service providers in optimizing and modernizing their fleets, as well as for end users, supporting them in selecting suppliers with vehicles that meet their preferences and expectations.

2.3. Selection of Criteria

In the process of multi-criteria evaluation of decision-making options, the proper selection of evaluation criteria for the established options is crucial, as they will enable a reliable and discriminating comparison of the analyzed alternatives. According to the Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDMA) approach, it is possible to take into account both quantitative and qualitative parameters, with the latter requiring prior quantification to ensure the comparability of criteria (assessments) [94].

In this study, a set of seven evaluation criteria was adopted, G = {gk: k = 1, …, 7}, including six quantitative measures and one qualitative discrete criterion. These criteria represent the key factors influencing decision-making by fleet operators and long-term rental clients.

The selection of criteria was based on the literature [95], supplemented by recommendations from a group of experts and the author’s arbitrary recommendations.

The expert team consisted of specialists representing long-term vehicle rental companies operating in the Polish market, including fleet managers, purchasing coordinators, and decision-makers responsible for vehicle selection and fleet policy. All experts had at least 8–12 years of professional experience in fleet management, operational planning, and purchasing decision-making in vehicle propulsion technologies. Their practical knowledge and direct involvement in long-term rental processes ensured that the evaluation criteria reflected actual market practices and operational requirements.

The experts assessed the decision-making criteria and options individually, which allowed them to avoid groupthink.

At the same time, the set of criteria (ratings) was ensured to meet the requirements of exhaustiveness, uniqueness of criteria, consistency of assessment, and minimizing the number of criteria to a level that would allow for differentiation between the evaluations of individual alternatives [2,3].

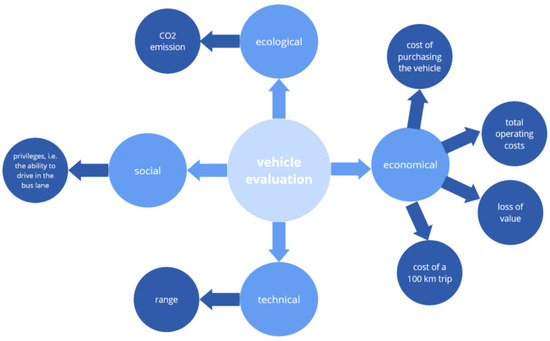

The selected criteria were divided into economic, environmental, technical, and social (Figure 6) and described using data from industry reports, vehicle specifications published by manufacturers, and benchmarking analyses available in public sources such as automotive databases and expert publications.

Figure 6.

Classification of criteria influencing the selection of vehicles in long-term rental systems.

The set of evaluations of decision options based on the established evaluation criteria is therefore as follows:

The selection of evaluation criteria reflects the specific decision-making process of fleet operators in the long-term rental sector and the variability of economic and technical parameters over time.

Economic criteria, including purchase and operating costs, are crucial because fleet profitability is directly determined by the TCO (Total Cost of Ownership). These parameters are characterized by high variability (e.g., fuel and electricity prices), which increases the importance of considering them in the variant evaluation process.

Technical criteria refer to the functional characteristics of vehicles, such as range and energy consumption. These determine the ability to perform specific transport tasks under predictable operating conditions. Their importance is particularly significant for corporate fleets, where route repeatability and reliability directly impact ongoing workflow and downtime costs.

The environmental criterion, although presented in a discrete form, reflects growing regulatory pressure and customer expectations regarding reduced emissions. Its role has steadily increased over time due to tightening EU standards, city policies, and ESG reporting requirements, which are gradually changing fleet operator preferences. Meanwhile, the social criterion has been defined as a set of “soft” benefits and conveniences offered to vehicle users under regulations and local policies (e.g., free parking in paid parking zones, access to bus lanes). In this study, this criterion was presented in a discrete form (0/1), where a value of 1 indicates that a given drive option benefits from specific privileges in the analyzed context, while a value of 0 indicates that such privileges do not exist. It should be emphasized that these privileges are strongly dependent on local and regulatory conditions and their validity over time (for example, access to bus lanes for BEVs is planned until 1 January 2026). Therefore, the social criterion serves as a contextual indicator in the model, influencing the practical attractiveness of the option in the short and medium term, but its importance may change significantly with changes in policies and regulations.

Incorporating these four groups of criteria allows for the capture of both current choice determinants and their potential evolution over time, ensuring consistency between industry practice and the theoretical foundations of multi-criteria decision support methods.

2.3.1. Economic Criteria

The purchase price of a vehicle is the highest unit cost throughout the entire ownership period. Regardless of list prices, buyers, especially institutional ones, can receive a number of additional discounts and bonuses, including those related to purchasing multiple vehicles at once or establishing a long-term relationship with a given supplier.

Due to the broad and difficult-to-standardize scope of such individual commercial arrangements, the purchase cost of the tested vehicles was determined solely based on official data provided by the manufacturer [96].

Administrative costs, which include all expenses related to vehicle registration and branding, were omitted from the analysis because they do not differentiate between electric and combustion vehicles.

Vehicle depreciation is the difference between the vehicle’s initial value and its residual value after a specified period of use. It reflects the decline in the vehicle’s value over time, resulting from its physical and moral wear and tear, as well as market changes (e.g., demand, technological development, or legal regulations) [97]. For the purposes of this study, the depreciation of the analyzed vehicles was determined for a 36-month period using the “INFO-PROGNOZA” computer program for estimating the residual value of vehicles on the Polish market [98]. According to [99], most long-term vehicle lease agreements are concluded for a period of 3 years.

In this analysis, the total operating costs of vehicle Cekspl incurred by the long-term rental operator in the year under review include the costs of vehicle insurance, periodic technical inspections, service packages, repairs, and tire costs.

The cost of fuel or energy consumption was identified as a separate evaluation criterion because it is borne by the end user, and therefore

where

t—year of operation.

—the annual cost of the insurance package for OC (Third Party Liability), AC/KR (Auto Casco and Theft) and NNW (Personal Accident Insurance) was adopted based on the offer of the car importer.

In Poland, the insurance rate for a given vehicle is determined based on many factors, including the vehicle’s value, engine power, vehicle model, and intended use. Third-party liability insurance (OC) is mandatory, but to ensure full coverage for damage resulting from collisions, natural disasters, vehicle theft, or vandalism, as well as to protect the life and health of the driver and passengers, comprehensive (AC) and personal accident (NNW) insurance premiums must also be paid. The analysis takes all of these components into account.

Currently, insurance premiums for electric vehicles are higher than for their conventional counterparts, primarily due to the vehicle’s higher initial value. The analysis used actual premiums for the vehicles studied, as reported in their insurance policies.

Another cost incurred by long-term rental operators is periodic technical inspections of vehicles . According to applicable Polish regulations, a newly registered vehicle is subject to its first mandatory technical inspection within three years of its initial registration, another after two years, and then annually. Therefore, the analysis, covering 36 months of operation, included only one technical inspection—in the third year of use. The cost of the inspection was assumed at the currently applicable rate, i.e., PLN 99 (including the registration fee) [100].

Service costs service related to operation depend on the type of vehicle, purpose, distance traveled annually and include all repairs and replacements of consumables in the vehicle, e.g., brake pads, throughout the entire period of use.

Service costs are lower for electric cars, which is due to the fact that electric vehicles have fewer moving parts, for example, there are no engine oil or fuel filters to replace (Table 1). Brake disks and pads also wear much slower due to the significant braking potential of the electric machine [101,102].

Table 1.

Maintenance service of an electric and combustion-powered vehicle [103].

This study assumes sample market rates for individual repairs and estimates the expected replacement frequency based on manufacturer data and service company recommendations (including the planned replacement of braking system components: front disks and pads at 30,000 km and rear disks at 60,000 km).

Among the recurring costs associated with vehicle use, it is also important to highlight expenses for ongoing vehicle maintenance. This is a specific amount allocated to keeping the vehicle clean and replenishing basic operating fluids (coolant, brake fluid, windshield washer fluid, and transmission oil). Such costs were not included in this study because they are borne by the person renting the vehicle.

The annual tire cost tires includes the purchase of a set of tires every 45,000 km and seasonal replacement twice a year. Unit tire prices and replacement costs were determined based on available market data.

The costs of a 100 km trip were determined based on the consumption of the energy carrier used to propel the vehicle, in accordance with the vehicle’s technical parameters [104]. Long-term rental vehicles travel different routes with different driving dynamics, which results from factors such as the driver’s driving style and road conditions. To determine the costs of a 100 km trip, electricity consumption and fuel consumption were averaged to ensure a consistent value for the entire analysis period, i.e., 3 years. The costs of refueling combustion vehicles and charging electric vehicles were determined for mixed driving, based on market data applicable in Poland in 2025, taking into account retail prices for individual customers. The costs of charging electric vehicles were calculated assuming a typical charging cycle (from 20% to 80% battery capacity) at publicly available charging stations in Poland, while average energy consumption was based on data regarding battery capacity and the manufacturer’s declared average WLTP (Worldwide Harmonized Light-Duty Vehicles Test Procedure) range.

The model does not make any assumptions regarding a possible increase in vehicle operating costs.

2.3.2. Technical Criterion

Vehicle range is defined as the maximum distance a vehicle can travel on a single fuel tank or full battery charge. Data is based on manufacturer declarations and test standards (WLTP—Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure) [96].

2.3.3. Social Criterion

Privileges are defined as additional facilities and amenities offered to vehicle users under applicable legal regulations and local transport policies, known as “soft” support mechanisms. This particularly applies to the benefits granted to BEV users resulting from activities promoting electromobility. Section 1 of Article 39 of the Act on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels states that in a municipality with a population of over 100,000, for the downtown area or part thereof, constituting a cluster of intensive developments within the downtown area, as defined in the local spatial development plan, or in the absence thereof, in the municipality’s study of conditions and directions of spatial development, a clean transport zone may be established within the area encompassing roads managed by the municipality, restricting entry to vehicles other than electric, hydrogen-powered, or natural gas-powered vehicles (the combustion of which (residual amounts of sulfur compound pollution) reduces SOx emissions but also causes CO2 emissions as a greenhouse gas).

Another benefit granted to BEV users is the ability to park free of charge in paid parking zones in cities [105], without the need for any additional vehicle markings, such as stickers or license plates.

Another incentive to encourage drivers to use electric cars in Poland is the ability to drive such vehicles in bus lanes designated by the road authority until January 1, 2026 [106].

Therefore, the analysis assumes

2.3.4. Environmental Criterion

CO2 emissions were determined for the vehicle’s use phase. For electric vehicles, the emission value was estimated taking into account the Polish energy mix [96,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115].

Table 2 presents the input data used to evaluate vehicles with different powertrain types in long-term rental systems.

Table 2.

Input data used for multi-criteria evaluation of cars used in long-term rental companies.

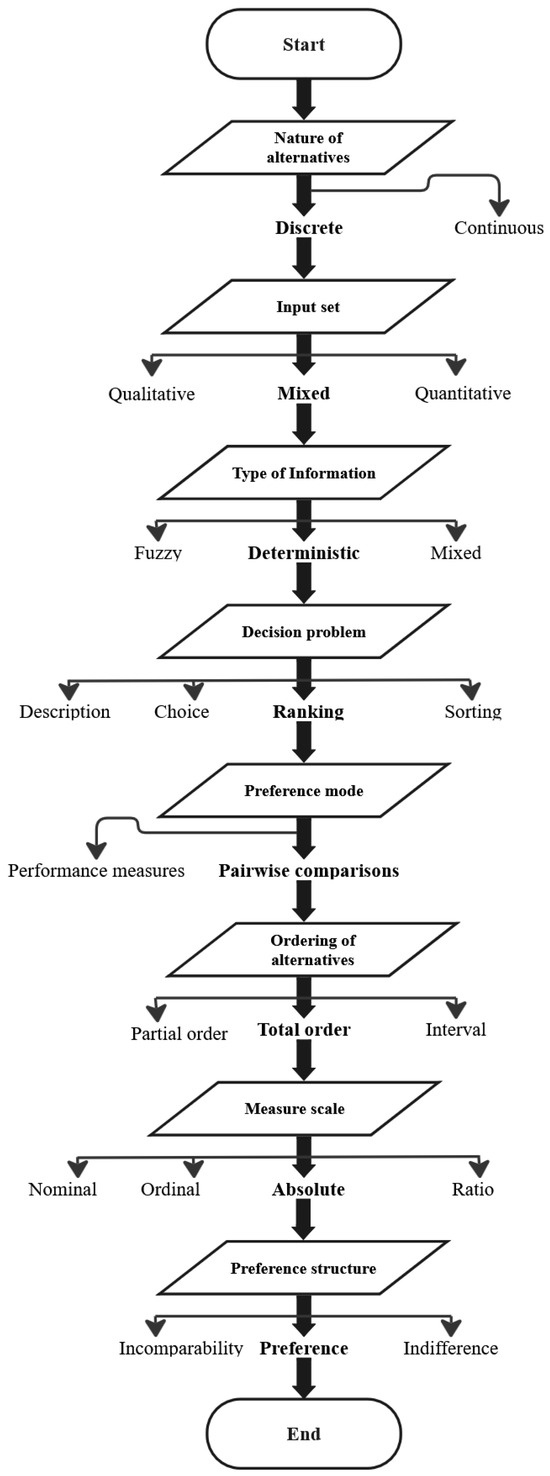

2.4. Method Selection

Due to the huge variety of available multi-criteria decision support methods MCDA, including both classical pari-comparison techniques and modern reference methods, i.e., SPOTIS, COMET, RANCOM, SIMUS, each of which has specific advantages, disadvantages and limitations [116,117,118,119,120,121,122], it is necessary to conduct a detailed qualitative analysis to select the appropriate tool for the decision-making problem under consideration. It has been observed that using the same input data, i.e., variant evaluations, criterion weights, and different MCDMA methods, different results can be obtained [123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130]. Consequently, the method selection itself can be treated as a multi-criteria problem [13,117].

For this reason, it is justified to use formal procedures supporting the selection of an appropriate multi-criteria evaluation method [131,132,133,134,135,136]. In this study, the Tecle model [137] was used, based on which it was determined that the most appropriate multi-criteria method for the analyzed problem is the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). A diagram of the selection of a multi-criteria optimization method depending on the conditions is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Algorithm for selecting a multi-criteria evaluation method for fleet vehicles in the long-term rental system, developed based on the Tecle model.

The AHP method was ultimately selected as the analytical tool due to the specific nature of the problem under consideration and the nature of the available data. First, AHP allows for the simultaneous consideration of quantitative, qualitative, and discrete criteria, which is particularly important given the heterogeneous data structure encompassing costs, technical parameters, and binary criteria. Second, the method provides a hierarchical model structure, facilitating the interpretation and transparency of results for fleet decision-makers. Third, AHP is one of the few MCDA methods that allows for the formal assessment of the consistency of expert assessments, which was crucial due to the use of individual, rather than group, expert opinions.

Modern MCDA methods, such as SPOTIS and COMET, while offering numerous advanced computational mechanisms (including resistance to ranking inversion and modeling of ideal reference profiles), require a clear definition of the ideal/anti-ideal for each criterion or characteristic object structure and extensive rule bases. In the case of seven mixed criteria and limited input data availability, this would lead to a significant increase in computational complexity, a loss of interpretability, and difficulties in practical application by fleet operators. Rule-based and optimization methods (e.g., SIMUS) are particularly effective in situations with extensive continuous data sets, which this decision-making problem does not address.

In light of the above conditions, AHP proved to be the most adequate, transparent, and operationally useful tool for evaluating drive variants in the context of long-term rentals.

2.5. Application of the AHP Method to the Selection of Means of Transport

2.5.1. Development of a Hierarchical Structure for the Decision-Making Process

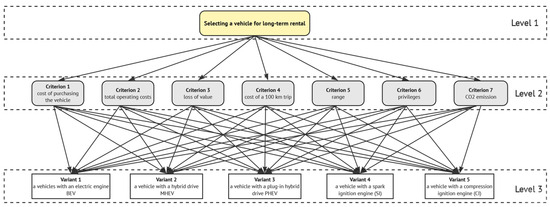

The use of the AHP method requires the development of a decision model with a hierarchical structure. Such a structure includes the goal of the decision, evaluation criteria, and decision options, and is usually presented in the form of a decision tree [138].

When analyzing the selection of motor vehicles with different types of propulsion for long-term rental fleets, taking into account their economic efficiency, technical parameters, and environmental impact, three levels were planned, creating a hierarchical structure (Figure 8). The first level refers to the study’s goal of identifying optimal vehicles. The second level comprises evaluation criteria, and the last level comprises decision-making options—vehicles equipped with internal combustion engines (SI, CI), hybrids, and electric vehicles, which constitute solutions to the problem at hand.

Figure 8.

Hierarchical structure of the analyzed decision problem.

2.5.2. Constructing a Matrix of Pairwise Comparisons of Criteria, Setting Priorities and Checking the Consistency of Criteria Weights

The pairwise criterion comparison matrix was created by comparing the hierarchy elements and assigning them scores on a scale of 1 to 9.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the results, this study was conducted in consultation with a group of experts representing companies offering long-term vehicle rentals. Drawing on their knowledge and extensive experience in fleet management and understanding the preferences of institutional clients, the experts determined the relative importance of individual criteria from a practical perspective.

This approach ensured that the decision-making process was based on a solid substantive foundation, took into account diverse perspectives, and facilitated the achievement of credible final results. The results of the pairwise comparison for the analyzed decision-making situation are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Pairwise Criteria Comparison Matrix.

Table 4 presents a normalized matrix with the designation of priorities for individual criteria. Furthermore, the table includes a global priority column, which can be written in a vector of W = [wk]K×1. Consistency testing, i.e., checking how logical and homogeneous the preferential information provided by the experts is, was performed by determining λ, CI, and CR.

Table 4.

Normalized matrix with priority assigned to a given criterion.

For the analyzed case: λ = 7.66, CI = 0.11, CR = 0.08. The values of the random index RI, given by Saaty for decision problems with a maximum number of variants not exceeding 15, are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Random index determination table RI.

The calculations showed that the value of the CR indicator is less than 0.1, and therefore it can be assumed that the decisions regarding the validity of the criteria are consistent, and further calculations can be carried out.

2.5.3. Comparison of Variants According to Each Criterion

Comparisons of decision options against the adopted criteria were performed in a similar manner to the criteria themselves. Individual decision options were compared with the remaining decision elements against a given criterion (Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12), and then the summed scores were used to normalize the scores.

Table 6.

Comparison of variants according to the criterion of vehicle purchase cost.

Table 7.

Comparison of variants according to the criterion of vehicle depreciation.

Table 8.

Comparison of variants according to the criterion of total operating costs.

Table 9.

Comparison of variants according to the criterion of the cost of traveling 100 km.

Table 10.

Comparison of variants according to the range criterion.

Table 11.

Comparison of variants according to the criterion of privileges.

Table 12.

Comparison of variants according to the CO2 emission criterion.

2.5.4. Normalization of Assessments and Setting Local Priorities for Variants with Respect to Each Assessment Criterion

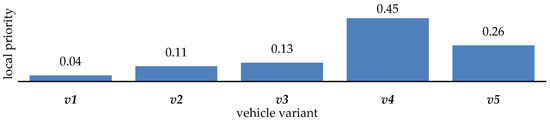

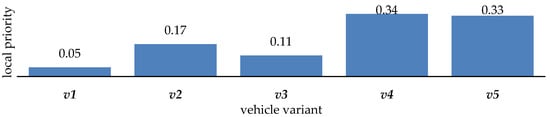

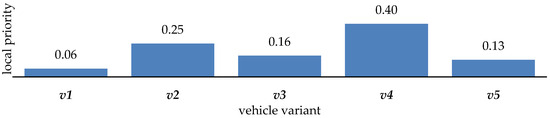

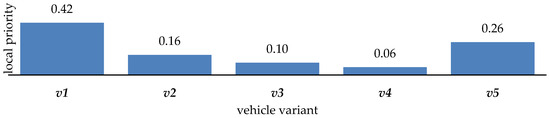

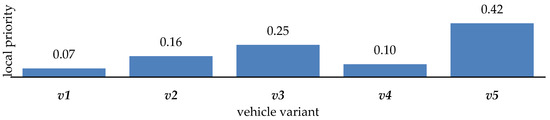

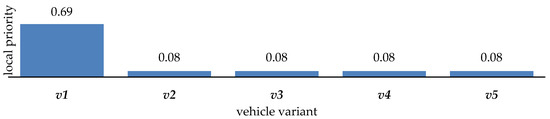

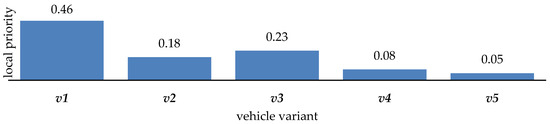

The normalization process involved dividing each element of the pairwise comparison matrix in each column by the sum of all coefficients in that column. The arithmetic mean of all normalized scores in each row is the local priority for a given variant. Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 below present the local priority value for variants with respect to the analyzed criterion.

Figure 9.

Local priority value for variants in relation to the vehicle purchase value criterion.

Figure 10.

Local priority value for variants in relation to the vehicle impairment criterion.

Figure 11.

Local priority value for variants in relation to the total operating costs criterion.

Figure 12.

The value of local priority for variants in relation to the criterion of cost of travel per 100 km.

Figure 13.

The local priority value for variants in relation to the range criterion.

Figure 14.

Local priority value for variants in relation to the privileges criterion.

Figure 15.

Local priority value for variants in relation to the CO2 emission criterion.

2.5.5. Checking the Consistency of Variant Assessments and Developing a Ranking of Decision Variants

The final stage of the analysis was to check the comparison matrix for the tested criteria for consistency. Therefore, for each criterion, λ, CI, and CR were determined according to the AHP algorithm. The results for each criterion are presented in Table 13. All CR values are less than 0.1, which means that the comparisons were found to be consistent for each criterion.

Table 13.

Results of the matrix consistency test for the analyzed variants according to the criteria.

Determining the final ranking of the analyzed variants, in accordance with AHP, required determining the product of two matrices, i.e., the matrix consisting of local priorities Pk = [pik]N×1, where i = 1, …, N is the variant number and k = 1, …K is the criterion number, and the matrix of global priorities W.

PW = Z = [zi]N×1

The product result, in the form of a single-column matrix, contains the evaluation of each variant. The variant with the highest score indicates the most favorable solution:

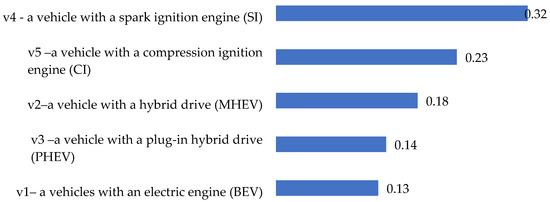

3. Results and Discussion

The final ranking of the analyzed vehicle variants was determined according to the standard aggregation procedure used in the AHP method. In the first step, a global criteria priority vector Ω = [ωk′k], was calculated based on the pairwise comparison matrix, reflecting the relative importance of individual criteria in the decision-making process. Next, for each drive option i, local priorities peak was calculated with respect to each criterion k, creating a local priority matrix P = [pki]. Global values were obtained by multiplying Z = PW, with each element zi representing a synthetic evaluation of a given drive option.

The resulting vector Z clearly indicates the ranking of the analyzed propulsion technologies. The gasoline vehicle achieved the highest global value (z1 = 0.32), followed by the diesel vehicle (z2 = 0.23), MHEV (z3 = 0.18), PHEV (z4 = 0.14), and the BEV (z5 = 0.13) (Figure 16). These values directly result from the aggregation formula zi = , meaning that alternatives performing strongly under highly weighted criteria systematically obtain higher global scores. The structure of vector Z confirms that economic and operational criteria, characterized by the highest weights in vector W, play a key role in shaping the results.

Figure 16.

Final ranking of propulsion variants based on the AHP results.

The obtained results are consistent with actual market trends. According to data from the Polish Vehicle Rental and Leasing Association (PZWLP) for the first quarter of 2025, gasoline vehicles constitute 55.3% of long-term rental fleets in Poland, diesel vehicles 30.4%, and eco-friendly drives (hybrid and electric combined) only 14.3% [93].

The convergence between the AHP model results and the actual fleet structure demonstrates the reliability of the obtained estimates. The dominance of combustion technologies in both the model results and market practice indicates that decisions in the long-term rental sector remain primarily focused on cost and operational reliability, while environmental factors currently have only a marginal impact. These results may suggest the need for further regulatory and financial incentives to increase the attractiveness of low- and zero-emission vehicles in the fleet segment.

4. Conclusions

Long-term vehicle rental is an increasingly popular fleet management solution for both businesses and individuals. This model allows users to use new vehicles without having to purchase them, significantly reducing financial risk, simplifying operational cost planning, and increasing flexibility in mobility management. For fleet operators, selecting the right drive types is crucial to ensuring the profitability of services provided, compliance with environmental regulations, and the attractiveness of the offer to end customers.

The aim of this study was to conduct a multi-criteria evaluation of passenger vehicle powertrain options from the perspective of a long-term rental operator, using the AHP method. Five powertrain options (BEV, MHEV, PHEV, SI, CI) of the same C-segment vehicle model were analyzed, taking into account seven decision criteria grouped into four main categories: economic (purchase cost, depreciation, operating costs, cost of driving 100 km), technical (range), environmental (CO2 emissions), and social (privileges).

Based on comparative analyses and normalization of the preference matrix, local priorities were determined for each option with respect to a given criterion. The resulting priorities were characterized by high logical consistency (CR < 0.1 for all criteria), confirming the validity of the evaluation structure. The final ranking of the options was determined by multiplying the local priority matrix by a vector of criterion weights, which reflected the importance of individual ratings from the operator’s perspective.

The highest synthetic value (0.32) was achieved by the gasoline-powered vehicle (SI), which received particularly high scores for purchase costs, depreciation, and operating costs—which determined its dominance, assuming a high weighting of economic criteria. Subsequent places were occupied by the diesel variant (0.23), MHEV (0.18), PHEV (0.14), and BEV (0.13), respectively. Despite the applicable privileges and the lowest CO2 emissions, the electric variant received the lowest score, due to its high purchase cost and significant operating costs (charging, depreciation).

Based on the obtained results, it is clear that in the current market environment, fleet operators’ decisions are strongly determined by economic, technical, and operational criteria. Environmental and social factors, while important, have a smaller impact on the final rating, which may suggest the limited effectiveness of existing support mechanisms for zero-emission vehicles in the long-term rental sector. This suggests the need for further public policy reforms, such as increasing subsidies, changing depreciation rules or extending fleet privileges for low-emission vehicles, to actually influence the purchasing decisions of fleet operators and their customers.

In addition to the analytical findings, the results obtained allow for the formulation of several practical recommendations that may support both long-term rental operators and public authorities.

From the perspective of fleet operators, a gradual transition toward low- and zero-emission vehicles should be based on a structured assessment of total cost of ownership under real operating conditions. This includes negotiating long-term charging contracts, optimizing fleet utilization models for BEVs (e.g., assigning electric vehicles to predictable and repetitive routes), and diversifying fleet structures to balance economic performance with future regulatory compliance. Operators may also benefit from piloting small-scale BEV deployments supported by operational monitoring, which would allow them to quantify the economic effects of electrification before implementing large-scale changes. From the perspective of policymakers, strengthening the competitiveness of electric vehicles in long-term rental fleets requires targeted and stable support instruments. These include financial incentives (e.g., purchase subsidies for firms, accelerated depreciation schemes, or tax reductions), expanded charging infrastructure tailored to fleet needs, and regulatory measures that increase the operational attractiveness of BEVs—such as extending access to dedicated lanes, expanding zero-emission transport zones, or reducing parking and road use charges. Introducing long-term and predictable policy frameworks may mitigate investment risk for fleet operators and accelerate the adoption of low-emission technologies.

Overall, the combination of market-driven fleet strategies and well-designed public policies can significantly enhance the role of low- and zero-emission vehicles in the long-term rental sector, supporting both economic efficiency and environmental objectives.

Despite its methodological consistency, the study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, fuel and electricity prices were treated as static parameters, whereas in reality they fluctuate significantly. Second, the model does not account for differences in driving style, annual mileage, or vehicle load, which have a significant impact on actual fuel or energy consumption. Third, the hierarchical structure of the criteria simplifies the actual decision-making process and does not encompass all possible determinants, including infrastructure, seasonality, or technological changes. These limitations define the model’s applicability and provide a starting point for further research incorporating operational data and dynamic models.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by Institution Committee due to the Polish Act of 20 July 2018—Law on Higher Education and Science (Journal of Laws 2018, item 1668, as amended) and the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation (EU) 2016/679), ethical approval is required only for studies involving human participants or the processing of personal data. As this survey was anonymous and limited to professional opinions, no approval from an Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board was required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Witkowska, D. Introduction to Operations Research; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej: Łódź, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B. Multi-Criteria Decision Support; WydawnictwaNaukowo-Techniczne Sp. z o.o.: Warsaw, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Vincke, P. Multicriteria Decision-Aid; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Żak, J. The methodology of multiple-criteria decision making in the optimization of an urban transportation system. Case study of Poznan City in Poland. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 1999, 6, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żak, J.; Redmer, A.; Sawicki, P. Wielokryterialnewspomaganiedecyzji w transporciedrogowym. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Poznańskiej 2004, 57, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet-Lagreze, E.; Siskos, J. Assessing a Set of Additive Utility Functions for Multicriteria Decision Making, the UTA Method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1982, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacyna, M. Decision Support in Engineering Practice; Polish Scientific Publishers PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cascales, M.S.; Lamata, M.T. Solving a decision problem with linguistic information. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2007, 28, 2284–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. Axiomatic foundation of the analytic hierarchy process. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tułecki, A.; Król, S. Decision-making models using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method in the transport area. Probl. Eksploat. 2007, 2, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L.; Ozdemir, M. Why the magic number seven plus or minus two. Math. Comput. Model 2003, 38, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, E.; Pereyra-Rojas, M. Practical Decision Making an Introduction to the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Using Super Decisions V2; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, K. Supplier Selection: An MCDA-Based Approach. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 88. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, T.H. Digital Modeling of Economic Systems; PWN Scientific Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J. The Application of Analytic Hierarchy Process Method in the Evaluation of Educational Quality in Colleges and Universities. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 2022, 6, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Awadh, M. Utilizing Multi-Criteria Decision Making to Evaluate the Quality of Healthcare Services. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, M.B. A Fuzzy AHP Approach for Supplier Selection Problem: A Case Study in a Gear Motor Company. Int. J. Manag. Value Supply Chain. 2013, 4, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarife, D.R.; Nakanishi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Estoperez, N.; Tahud, A. Integrated GIS and Fuzzy-AHP Framework for Suitability Analysis of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems: A Case in Southern Philippines. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, G.; Naik, R.; Shiva, P.H.C. A vendors evaluation using AHP for an Indian steel pipe manufacturing company. Int. J. Anal. Hierarchy Process 2016, 8, 442–461. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, L.L.; Ferreira, M.C. AHP Approach Applied to Multi-Criteria Decisions in Environmental Fragility Mapping. Floresta 2020, 50, 1623–1632. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5380/rf.v50i3.65146 (accessed on 15 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kriswardhana, W.; Toaza, B.; Esztergár-Kiss, D.; Duleba, S. Analytic hierarchy process in transportation decision-making: A two-staged review on the themes and trends of two decades. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 261, 125491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Joshi, L.K.; Pamt, S.; Kumar, A.; Ram, M. Exploring the diverse applications of the analytic hierarchy process: A comprehensive review. Math. Eng. Sci. Aerosp. 2024, 15, 423–436. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Zang, X.; Cai, X.; Gong, H.; Yuan, J.; Yang, J. Vehicle lane-changing safety pre-warning model under the environment of the vehicle networking. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Bi, Y.; Han, Y.; Xie, D.; Li, R. Research on safe driving behavior of transportation vehicles based on vehicle network data mining. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2020, 31, e3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, M.; Takemoto, A.; Asano, M.; Takada, T. Study on Improving Worker Safety at Roadway Sites in Japan. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 1, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukesh, M.S.; Katpatal, Y.B. Evaluation of pedestrian safety in fast developing Nagpur City, India. J. Urban Environ. Eng. 2020, 14, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeranurat, W.; Suanmali, S. Determination of black spots by using accident equivalent number and upper control limit on rural roads of Thailand. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2021, 13, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podvezko, V.; Sivilevičius, H. The use of AHP and rank correlation methods for determining the significance of the interaction between the elements of a transport system having a strong influence on traffic safety. Transport 2013, 28, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, D.; Moslem, S. Evaluation and Ranking of Driver Behavior Factors Related to Road Safety by Applying Analytic Network Process. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2020, 48, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón-Biosca, S.A.; Betanzo-Quezada, E.; Romero-Navarrete, J.A.; Ríos-Nuñez, M. Rating road traffic education. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 56, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, O.; Turan, O. Analytical investigation of marine casualties at the Strait of Istanbul with SWOT-AHP method. Marit. Policy Manag. 2009, 36, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, W.K. Ports’ service attributes for ship navigation safety. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kececi, T.; Arslan, O. SHARE technique: A novel approach to root cause analysis of ship accidents. Saf. Sci. 2017, 96, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Ö.; Alemdar, K.D.; Campisi, T.; Tortum, A.; Çodur, M.K. The development of decarbonisation strategies: A three-step methodology for the suitable analysis of current EVCS locations applied to Istanbul, Turkey. Energies 2021, 14, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Ö.; Tortum, A.; Alemdar, K.D.; Çodur, M.Y. Site selection for EVCS in Istanbul by GIS and multi-criteria decision-making. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 80, 102271. [Google Scholar]

- Khalife, A.; Fay, T.A.; Göhlich, D. Optimizing public charging: An integrated approach based on GIS and multi-criteria decision analysis. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaşan, A.; Kaya, İ.; Erdoğan, M. Location selection of electric vehicles charging stations by using a fuzzy MCDM method: A case study in Turkey. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 4553–4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthopoulos, L.; Kolovou, P. A multi-criteria decision process for EV charging stations’ deployment: Findings from Greece. Energies 2021, 14, 5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadori, M.S.; Gonçalves, A.B.; Moura, F. A GIS-MCDM method for ranking potential station locations in the expansion of bike-sharing systems. Axioms 2022, 11, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Wei, W. An AHP-DEA Approach of the bike-sharing spots selection problem in the free-floating bike-sharing system. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2020, 2020, 7823971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N.; Seker, S.; Özkan, B. Planning location of mobility hub for sustainable urban mobility. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 81, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilisik, O.N.; Demirtaş, N.; Tuzkaya, U.R.; Baraçl, H. Garage location selection for public transportation system in Istanbul: An integrated fuzzy AHP and fuzzy axiomatic design based approach. J. Appl. Math. 2014, 2014, 541232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KazaziDarani, S.; AkbariEslami, A.; Jabbari, M.; Asefi, H. Parking lot site selection using a fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS framework in Tuyserkan Iran. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2018, 144, 04018022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palevičius, V.; Paliulis, G.M.; Venckauskaite, J.; Vengrys, B. Evaluation of the requirement for passenger car parking spaces using multi-criteria methods. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2013, 19, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkaya, M.; Keleş, N. Determining criteria interaction and criteria priorities in the freight village location selection process: The experts’ perspective in Turkey. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 1348–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka, B. Application of fuzzy AHP and ELECTRE to China dry port location selection. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2011, 27, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadaifci, C.; Asan, U.; Serdarasan, S.; Arican, U. A new rule-based integrated decision making approach to container transshipment terminal selection. Marit. Policy Manag. 2019, 46, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, K.; Tabak, C.; Yerlikaya, M.A.; Efe, B. A logistics model suggestion for a logistics center to be established: An application in Aegean and Central Anatolia region. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2022, 35, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komchornrit, K. Location selection of logistics center: A case study of greater Mekong subregion economic corridors in Northeastern Thailand. ABAC J. 2021, 41, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Leviäkangas, P.; Lähesmaa, J. Profitability evaluation of intelligent transport system investments. J. Transp. Eng. 2002, 128, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudela, A.; Akiki, N.; Cisternas, R. Comparing the output of cost benefit and multi-criteria analysis: An application to urban transport investment. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2006, 40, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Yang, S.; Dong, S. Sustainability evaluation of high-speed railway (HSR) construction projects based on unascertained measure and analytic hierarchy process. Sustainability 2018, 10, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Tang, T.; Zhang, G.; Lu, L. Study on grey correlation degree decision-making model for investment scheme on high-grade highways in Western China. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6092328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, F.C.M.; de Carvalho, F.S. Multicriteria analysis of inland waterway transport projects: The case of the Marajó Island waterway project in Brazil. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2013, 36, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevadakis, D.; Bury, A.; Ren, J.; Wang, J. A services operations performance measurement framework for multimodal logistics gateways in emerging megaregions. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2021, 44, 63–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, T.; Ribeiro, R.A. A framework for selecting bus priority system locations in medium-sized cities: Case study in Araraquara Brazil. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 2053–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Wang, P.; Chi, H.-L.; Zhong, Y.; Song, Y. Exploring factors affecting transport infrastructure performance: Data-driven versus knowledge-driven approaches. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 24714–24726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnars, H.L.H.S.; Kusnadi, E.; Warnars, L.L.H.S. Prediction of road infrastructure priorities in Banten province using analytical hierarchy process method. Int. J. Eng. Res. Africa 2021, 53, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Dabous, S.; Zeiada, W.; Zayed, T.; Al-Ruzouq, R. Sustainability-informed multi-criteria decision support framework for ranking and prioritization of pavement sections. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromal, V.; Naseer, M.A. Prioritization of influential factors for the pedestrian facility improvement in Indian cities. J. Urban Des. 2022, 27, 348–363. [Google Scholar]

- Hayati, E.; Majnounian, B.; Abdi, E.; Sessions, J.; Makhdoum, M. An expert-based approach to forest road network planning by combining Delphi and spatial multi-criteria evaluation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanadtang, P.; Park, D.; Hanaoka, S. Incorporating uncertain and incomplete subjective judgments into the evaluation procedure of transportation demand management alternatives. Transportation 2005, 32, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rúa, E.; Comesaña-Cebral, L.; Arias, P.; Martínez-Sánchez, J. A top-down approach for a multi-scale identification of risk areas in infrastructures: Particularization in a case study on road safety. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Guo, X.; Wei, B.; Chen, B. A fuzzy analytic hierarchy process for risk evaluation of urban rail transit PPP projects. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 41, 5117–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Khanna, R.; Kohli, P.; Agnihotri, S.; Soni, U.; Asjad, M. Risk evaluation of electric vehicle charging infrastructure using Fuzzy AHP—A case study in India. Oper. Manag. Res. 2023, 16, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, A.O.; Demir, M.; Akgul, M. Assessment of risk factors in forest road design and construction activities with fuzzy analytic hierarchy process approach in Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Sarkar, D.; Vara, D. Comparative study of risk indices for infrastructure transportation project using different methods. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. A 2019, 100, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdiani, M.A.; Mohit, M.A.; Mosayebi, S.A. Investigation and prioritization of railway reconstruction projects by using analytic hierarchy process approach: Case study—Kerman and southeastern areas in Iranian Railways. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2022, 66, 671–680. [Google Scholar]

- Sivilevičius, H.; Skrickij, V.; Skačkauskas, P. The correlation between the number of asphalt mixing plants and the production of asphalt mixtures in European countries and the Baltic States. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraima, M.B.; Qiu, Y.; Yusupov, B.; Ndjegwes, C.M. A study on the development strategy of the railway transportation system in the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) based on the SWOT/AHP technique. Sci. Afr. 2020, 8, e00388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, V.; Sharma, S.; Bhatia, R. Investment decisions and project management over Indian railways: A case of freight corridors. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2023, 27, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inti, S.; Tandon, V. Application of fuzzy preference-analytic hierarchy process logic in evaluating sustainability of transportation infrastructure requiring multicriteria decision making. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2017, 23, 04017014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inal, O.B.; Zincir, B.; Deniz, C. Investigation on the decarbonization of shipping: An approach to hydrogen and ammonia. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 19888–19900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, M.; Kaya, I. Evaluating alternative-fuel buses for public transportation in Istanbul using interval type-2 fuzzy AHP and TOPSIS. J. Mult. Valued Log. Soft Comput. 2016, 26, 625–642. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, M.; Fawaz, Z. Evaluation of microalgal alternative jet fuel using the AHP method with an emphasis on the environmental and economic criteria. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2013, 32, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiracı, K.; Akan, E. Aircraft selection by applying AHP and TOPSIS in interval type-2 fuzzy sets. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, P.; Król, A. The influence of preliminary processing of end-of-life tires on transportation cost and vehicle exhaust emissions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24256–24269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzkaya, U.R. Evaluating the environmental effects of transportation modes using an integrated methodology and an application. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 6, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atawi, A.M.; Kumar, R.; Saleh, W. Transportation sustainability index for Tabuk city in Saudi Arabia: An analytic hierarchy process. Transport 2016, 31, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.; Lee, G.; Oh, C. A multi-criteria analysis framework including environmental and health impacts for evaluating traffic calming measures at the road network level. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 13, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, L.R.; De Vicente Oliva, M.A.; Romero-Ania, A. Managing sustainable urban public transport systems: An AHP multicriteria decision model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrittella, M.; Certa, A.; Enea, M.; Zito, P. Transport policy and climate change: How to decide when experts disagree. Environ. Sci. Policy 2008, 11, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dano, U.L.; Abubakar, I.R.; AlShihri, F.S.; Ahmed, S.M.S.; Alrawaf, T.I.; Alshammari, M.S. A multi-criteria assessment of climate change impacts on urban sustainability in Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavimasouleh, S.O.; Salehi, I.; Sadeghi, F.; Mohammadi Fard, M.; Roshanghalb, A. Mixed transport network prioritization based on environmental impact and population density. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 6928576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Padillo, A.; Ruiz, D.P.; Torija, A.J.; Ramos-Ridao, Á. Selection of suitable alternatives to reduce the environmental impact of road traffic noise using a fuzzy multi-criteria decision model. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 61, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, F.; Di Mascio, P.; Lombardi, L.; Ridolfi, B. Methodology for the identification of economic, environmental and health criteria for road noise mitigation. Noise Mapp. 2022, 9, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Iglesias, E.; Peón, D.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, J. Mobility innovations for sustainability and cohesion of rural areas: A transport model and public investment analysis for Valdeorras (Galicia, Spain). J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3520–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civil Code, Journal of Laws 2024.1061, i.e. Art. 659 (Lease Agreement). Available online: https://sip.lex.pl/akty-prawne/dzu-dziennik-ustaw/kodeks-cywilny-16785996/art-659 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- 4mobility. What Cars are Most Frequently Chosen for Rental in 2025? Available online: https://4mobility.pl/jakie-auta-sa-najczesciej-wybierane-do-wynajmu-w-2025-roku/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- SAMAR. Available online: https://www.samar.pl/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- PZWLP. Available online: https://pzwlp.pl/wynajem-dlugoterminowy (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Broniewicz, E.; Dziurdzikowska, E. Multi-criteria methods in balancing socio-economic processes. Res. Papers Wrocław Univ. 2017, 491, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jarašūnienė, A.; Batarlienė, N.; Šidlauskis, B. Management of Risk Factors in the Rental Car Market. Future Transp. 2024, 4, 1457–1475. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7590/4/4/70?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 2 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hyundai. Available online: https://www.hyundai.com/pl/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Borkowski, A.; Zawiślak, M. Comparative analysis of the life-cycle emissions of carbon dioxide emitted by battery electric vehicles using various energy mixes and vehicles with ICE. Combust. Engines 2023, 192, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Info-Ekspert. Available online: https://www.info-ekspert.pl/index.php5 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- portalZP. Long-Term Car Rental for Companies—What Does It Involve? Available online: https://www.portalzp.pl/materialy-partnerow/wynajem-dlugoterminowy-samochodu-dla-firm-na-czym-polega-33471.html (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Regulation of the Minister of Infrastructure of 29 September 2004 on the Fees for Running Vehicle Inspection Stations and Carrying Out Technical Inspections of Vehicles. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20042232261 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Hagman, J.; Ritzen, S.; Janhager, J.; Susilo, Y. Total cost of ownership and its potential implications for battery electric vehicle diffusion. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2016, 18, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeau, K.; Lebeau, P.; Macharis, C.; Van Mierlo, J. How expensive are electric vehicles? A total cost of ownership analysis. World Electr. Veh. J. 2013, 6, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendek-Matysiak, E.; Pyza, D.; Łosiewicz, Z.; Lewicki, W. Total Cost of Ownership of Light Commercial Electrical Vehicles in City Logistics. Energies 2022, 15, 8392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.J.; Tate, E.; Wadud, Z.; Nellthorp, J. Total cost of ownership and market share for hybrid and electric vehicles in the UK, US and Japan. Appl. Energy 2018, 209, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 11 January 2018 on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels. 2018. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20180000317/T/D20180317L.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Road Traffic Law. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/home.xsp (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Marczak, H.; Droździel, P. Analysis of Pollutants Emission into the Air at the Stage of an Electric Vehicle Operation. J. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 22, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobol, Ł.; Dyjakon, A. The Influence of Power Sources for Charging the Batteries of Electric Cars on CO2 Emissions during Daily Driving: A Case Study from Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, M.; Żebrowski, A.; Esmer, O. Cumulative Emissions of CO2 for Electric and Combustion Cars: A Case Study on Specific Models. Energies 2022, 15, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gis, M.; Bednarski, M.; Lasocki, J. Determination of pollutant emission of electric vehicle in real traffic conditions in Poland. Combust. Engines 2019, 178, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electric Vehicle Database. Available online: https://ev-database.org/car/1830/Hyundai-Kona-Electric-65-kWh.com (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- CO2 Everything. Available online: https://www.co2everything.com/co2e-of/hyundai-kona-electric-2020 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Everything Electric. Available online: https://fullycharged.show/reviews/hyundai-kona-performance-review.com (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Bieker, G. A Global Comparison of the Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Combustion Engine and Electric Passenger Cars. 2021. Available online: https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/Global-LCA-passenger-cars-jul2021_0.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Plötz, P.; Link, S.; Ringelschwendner, H.; Keller, M.; Moll, C.; Bieker, G.; Dornoff, J.; Mock, P. Real-World Usage of Plug-in Hybrid Vehicles in Europe: A 2022 Update on Fuel Consumption, Electric Driving, and CO2 Emissions. ICCT 2022. Available online: https://theicct.org/publication/real-world-phev-use-jun22 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Vansnick, J.-C. On the problem of weights in multiple criteria decision making (the noncompensatory approach). Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1986, 24, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Ergu, D. When is a decision-making method trustworthy? Criteria for evaluating multi-criteria decision-making methods. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2015, 14, 1171–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B.; Słowiński, R. Questions guiding the choice of a multicriteria decision aiding method. Eur. J. Decis. Process 2013, 1, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezert, J.; Tchamova, A.; Han, D.; Tacnet, J.-M. The SPOTIS Rank Reversal Free Method for Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Support. In Proceedings of the FUSION 2020, 23rd International Conference on Information Fusion, Pretoria, South Africa, 6–9 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shekhovtsov, A.; Kizielewicz, B.; Sałabun, W. Advancing individual decision-making: An extension of the characteristic objects method using expected solution point. Inf. Sci. 2023, 647, 119456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Więckowski, J.; Kizielewicz, B.; Shekhovtsov, A.; Sałabun, W. RANCOM: A novel approach to identifying criteria relevance based on inaccuracy expert judgments. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]