Abstract

This study introduces an Impact Thinking Approach (ITA) as a strategic framework to strengthen traceability implementation in the fashion and textile industry. The research examines how ESG impact dimensions shape sustainable strategy definition and how traceability can act as a strategic enabler rather than a mere compliance tool. A mixed-method design combining a narrative literature review, content analysis of 69 sustainability sources, and a two-round Delphi study with 19 experts was employed to identify, evaluate, and prioritize impact drivers related to traceability adoption. The resulting ITA framework connects regulatory requirements, impact materiality, and traceability demands into a unified structure that clarifies the strategic relevance of environmental, social, and governance dimensions. Findings reveal that governance-related factors—particularly data transparency, stakeholder engagement, innovation capacity, and cross-sector partnerships—are the strongest enablers for activating effective traceability schemes. The framework provides practitioners with structured guidance for integrating traceability into sustainable business strategies and for developing impact-aligned KPIs and decision-making mechanisms. The study contributes theoretical insights into the ESG–traceability nexus and offers a practical model to support regulatory alignment, organizational readiness, and long-term strategic planning.

1. Introduction

The importance of sustainability has grown, evolving from an ancillary consideration to a core strategic priority. As organizations increasingly aim to address complex global challenges, there is a growing need to integrate sustainability principles into all levels of decision-making and operations. Elkington’s Triple Bottom Line framework [1] established the need to integrate social, environmental, and economic dimensions. This perspective later evolved through the inclusion of governance [2] and the emergence of ESG as a multidimensional performance framework [3], laying the foundations for what are now the ESG dimensions. A significant portion of the ESG literature focuses on reporting sustainability practices rather than on understanding ESG dimensions as impact categories [4]. This introduced a shift in perspective, offering a more forward-looking view of how impact analysis can connect strategy and management with everyday practices across the value chain. This strategic interpretation of sustainability is consistent with the impact-based governance perspective advanced by Van Tulder et al., who conceptualize corporate sustainability as a system of interdependent stakeholders, cross-sector partnerships, and SDG-oriented coordination structures [5]. A comparable shift is visible in how traceability has been theorized and implemented. Earlier literature largely described it as an operational capability intended to strengthen sustainable supply chain management and improve performance [6]. Nevertheless, more recent contributions position traceability as a strategic lever that can reshape organizational capabilities and support long-term growth [7,8].

Building on this stream of work, this paper proposes ITA as a novel strategic framework, drawing from a review of the following existing research-based models: the conceptual framework proposed by Garcia-Torres et al. [9], which states the systemic but still partial treatment of traceability due to its predominant focus on operational supply chain processes; the life-cycle thinking model applied by Luján-Ornelas et al. [10] to map environmental impacts across value-chain stages; the classification of technological traceability approaches developed by Gayialis et al. [11], oriented toward product authenticity and operational transparency; the high-level structure for lifecycle traceability planning introduced by [12]; the multi-tier sustainability assessment model by Riemens et al. [13], combining empirical and fuzzy methods to support decision-making; and the framework outlined by Warasthe et al. [14], which connects sustainability with supply chain risk and performance. Unlike prior models, which tend to isolate specific dimensions of sustainability (e.g., lifecycle monitoring, technological solutions, risk mitigation, or multi-tier supply chain assessment), ITA offers a relational and integrative perspective that explicitly connects traceability requirements with ESG in a unified structure. The framework departs from existing approaches by expanding the scope of traceability beyond its traditional treatment as a stand-alone system or narrow compliance tool, aligning it instead with material sustainability performance drivers [15,16]. Our proposal redefines traceability as a strategic enabler that both shapes and is shaped by multiple impact dimensions. It also integrates managerial, organizational, and operational factors, addressing the concurrency and interdependence of drivers that earlier frameworks typically analyzed in isolation. Furthermore, ITA introduces an impact-oriented logic that links sustainability objectives with traceability priorities, allowing practitioners to understand how each impact driver contributes to strategic decision-making, capability development, and long-term transformation. From this standpoint, traceability becomes central to sustainability initiatives, providing continuous oversight and governance. Zhang et al. [17] argue that assessing impact performance requires examining how traceability contributes to innovation, resource efficiency, and the strengthening of organizational capabilities, ultimately enhancing Total Factor Productivity (TFP). Such alignment shows that productivity performance has also evolved by incorporating impact considerations into its measurement, which enables organizations to reconfigure their strategic capacities and reinforce business practices oriented toward measurable impact. However, to ensure effective traceability, it is important not only to develop the right tools but also to build a culture that supports the adoption and continued use of these practices [18,19]. Furthermore, the combination of increasingly stringent regulatory frameworks and rising stakeholder expectations has made traceability indispensable for identifying relevant impact areas and mitigating adverse effects on stakeholders [20]. In this context, stakeholder collaboration has emerged as an important driver to overcome the decoupling between governments, the private sector, and society. This outcome is consistent with the findings of Sancha et al. [21], who argue that assessment is a necessary precondition for effective collaboration, reinforcing the view that rigorous evaluation mechanisms are essential to advancing collaborative efforts toward sustainability objectives. Wohlrab et al. [22] provide an empirical understanding of the relationship between collaborative aspects and traceability management, expanding the concept of traceability management as a driver of social collaboration. However, there is still little quantitative empirical evidence on the relationship and practical intersections between traceability and stakeholder collaboration [23]. Similarly, there is limited observational evidence on the relationship between behavioral dynamics and traceability. Few studies demonstrate how the assignment of roles and the assumption of responsibilities remain a central challenge for traceability management in collaborative environments, particularly due to asymmetries in the benefits perceived by different stakeholders. Likewise, Schaëfer et al. [24] support this idea by stating that involving stakeholders is especially difficult when efforts and benefits are unevenly distributed across roles. Hristov et al. [25] provide evidence that integrating stakeholders into performance management systems improves decision-making and enhances value creation. At the same time, active stakeholder engagement is also assumed to positively influence the credibility and transparency of sustainability reporting [26].

Clearly, a consensus framework is needed to support the highly complex nature of this field. Indeed, recent reports stress the necessity of policy harmonization, an unprecedented degree of commitment, collaboration, and innovation, and greater technical convergence [27,28]. The sustainability landscape requires system-level alignment through common criteria and harmonized models that bridge theoretical foundations with practice. In response, our research introduces ITA as a model created to contribute to the impact-oriented perspective by providing empirical evidence of theoretical assumptions that connect ESG and traceability. To this end, the study integrates both primary and secondary data to assess traceability performance and to identify its key drivers. This methodological approach allows us to propose a framework that shows how addressing impact-related challenges can enhance understanding of their role in systematically shaping traceability adoption. To address this gap in the literature, the study proposes two Research Questions (RQs) aimed at clarifying the current state of impact assessment within the industry context:

RQ 1: How do ESG impact dimensions influence the formulation of sustainability strategies within the fashion and textile industry?

RQ 2: Which impact drivers most effectively enable the strategic adoption of traceability?

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 of this study provides a comprehensive overview of the State-of-the-Art upon which the research is based. Section 3 provides an overview of the research methodology employed in this study. In Section 4, the empirical results are presented through the ITA framework. In Section 5, the findings and their implications are discussed. Finally, Section 6 presents the conclusions drawn from this research.

2. Conceptual Background

Organizations face persistent challenges when implementing sustainable practices, including regulatory pressure, limited internal capabilities, and organizational resistance to integrating sustainability into core business strategy [16,29]. Many of these challenges stem from the difficulty of managing dynamic systems and adaptive strategies [30,31]. Observations from Doppelt [32] underline the persistent challenge organizations face in implementing consistent sustainability strategies, emphasizing the need for structured planning and execution. Although recent studies highlight the growing importance of incorporating ESG considerations into the orientation of sustainable business practices in the fashion and textile industry [33,34,35], there is still little empirical evidence on how ESG integration positively influences overall business performance [16]. Existing literature has primarily focused on how ESG responsibility performance affects business innovation [36,37], market value, and financial constraints [38,39]. As a result, organizations continue to face considerable complexity in linking ESG disclosure with effective assessment practices, largely due to fragmented data management and a lack of alignment between purpose, impact knowledge, and assessment criteria [16,40]. In response, greater attention has been given in recent years to the conceptualization and characterization of material elements for SSC. Materiality is defined as the process of identifying and assessing the ESG issues most relevant to an organization’s ability to sustain value creation over time [30,39]. Formalized by the Global Reporting Initiative [41], materiality has become the foundation for transparent sustainability reporting. Additionally, Nielsen [42] introduces the concept of impact materiality, which focuses on how an organization affects its most relevant stakeholders and is intended primarily for external, non-financial audiences in sustainability reporting. This definition aligns with Clément et al.’s [43] discussion of ESG as primarily non-financial indicators, rooted in the United Nations Global Compact’s [3] introduction of the framework, which assesses corporate performance across ESG dimensions. By integrating the concept of materiality into fashion and textile value chain management discourse, organizations are progressively transforming their strategies to ensure alignment with the most critical impact issues. It is important to point out that materiality is increasingly recognized in the literature as a fundamental mechanism for embedding sustainability efforts within overarching comprehensive performance and stakeholder expectations. Nielsen [42] builds on this by suggesting that materiality assessments are pivotal for risk management, seizing opportunities, and enhancing stakeholder cooperation. They emphasize the need for rigorous due diligence processes to validate impact assessments across the value chain. This leads to more accurate identification and reporting, based on traceability, aligning business models with impact performance indicators. Building on this, Dziubaniuk and Aarikka-Stenroos [44] highlight how value co-creation processes shape stakeholder interactions, emphasizing that collaborative engagement is essential for embedding materiality into sustainable business practices. Recent research further advances the discourse by integrating financial value and metrics alongside traditional non-financial indicators through the application of the double materiality concept [42,45]. This approach enhances analytical depth by recognizing the reciprocal influences between operations and external conditions, linking impact, financial performance, and risk management. From an organizational perspective, Belas et al. [46] further show that ESG is not only a reporting construct but also a multidimensional managerial phenomenon shaped by corporate social responsibility, business ethics, and human resource management practices. Their empirical findings from SMEs highlight that perceptions of ESG are strongly influenced by internal governance-related factors and managerial culture, which suggests that ESG adoption reflects deeper organizational commitments to sustainability-oriented business practices beyond mere external disclosure. This argument is reinforced by Porter and Kramer’s concept of Creating Shared Value (CSV), which posits that economic success and socio-environmental challenges are not mutually exclusive but rather interconnected [47]. This combination enables organizations to move beyond traditional static evaluations [39] while still incorporating traceability into compliance-oriented assessment frameworks.

Regulatory Complexity and Its Implications for ESG and Traceability

The fashion and textile industry faces increasing pressure to comply with overlapping regulations [48,49] while balancing economic interests and traceability imperatives. Despite this growing pressure, a substantial implementation gap remains between the formal awareness of policy frameworks and their practical application. Legal provisions are often interpreted inconsistently, and their implementation is frequently unclear and insufficiently scalable [50]. Several sources of inconsistency and uncertainty demonstrate this gap. First, many governance frameworks operate under a comply-or-explain approach rather than binding legislation. Second, evolving instruments such as the European Social Taxonomy remain under development. Its future requirements, particularly regarding social impacts and corporate contributions to social objectives, are still insufficiently defined. This lack of clarity leads to interpretive ambiguities, methodological divergence, and limited comparability across organizations [39,51]. Regulatory fluctuation further complicates the landscape. The Green Claims Directive, initially proposed as a harmonized framework for environmental claims, stalled in the legislative process, generating renewed uncertainty for both brands and consumers. If ultimately withdrawn, its greenwashing criteria are expected to be redistributed across existing instruments—including the CSDDD, the ESPR, and the Omnibus Directive—rather than consolidated into a single regulation, thereby increasing dispersion across compliance requirements. In parallel, the adoption of the revised Omnibus Directive represents a major inflection point in the ESG agenda. By amending core regulations such as the CSRD, the CSDDD, and the EU Taxonomy, the directive seeks to harmonize obligations, reduce administrative burden, and enhance competitiveness while preserving the objectives of the European Green Deal. Key elements include the shift toward a risk-based approach (removal of mandatory climate transition plans), reduced value-chain mapping requirements, and greater alignment across Member States. The updated ESRS standards reinforce this simplification through a substantial reduction in datapoints, clearer distinctions between mandatory and voluntary disclosures, and stronger guidance on applying materiality. The revision also enhances consistency with other EU legislation and improves interoperability with global standards [52]. Together, these developments underscore the growing need for coherent traceability systems capable of supporting ESG reporting within an increasingly streamlined yet multi-source regulatory environment. They also reinforce the importance of embedding anticipation, integration, and policy awareness into traceability schemes to ensure that they remain adaptable and aligned with evolving regulatory expectations and sustainability standards [53]. Although data collection and preliminary analysis are often regarded as relatively simple, formulating forward-looking strategies that embed ESG principles necessitates a coherent strategic vision, solid leadership commitment, and an organizational culture that prioritizes data-informed decision-making [15,40].

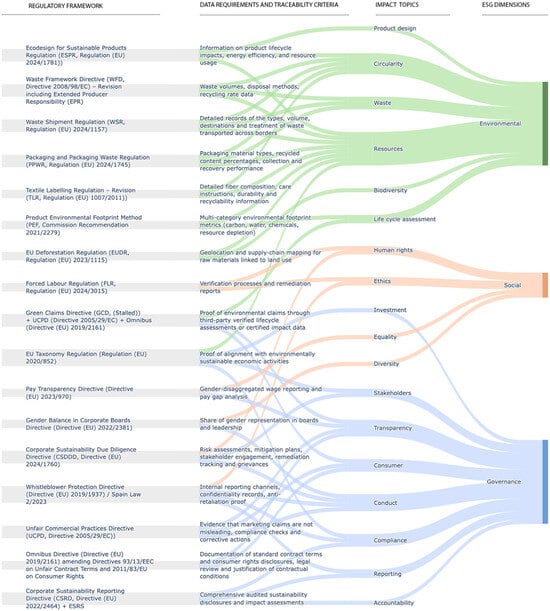

As mentioned above, the vision of traceability as a transformative system is gaining momentum, particularly in this volatile context. Figure 1 illustrates the regulatory landscape linked to ESG dimensions and their relationship with traceability requirements and impact topics. Figure 1 is structured as a left-to-right flow that visually links those four layers of information. On the left are the relevant EU regulations and directives, grouped by ESG focus. The middle column summarizes the data and traceability requirements introduced by each regulation. These requirements are then linked to a set of impact topics shown in the next column. Finally, on the right, these impact topics are mapped onto the corresponding ESG dimensions. This visualization clarifies how regulatory obligations translate into operational and strategic sustainability priorities.

Figure 1.

Sankey Diagram illustrating the linkage between the European Textile Regulatory Landscape (left) [48,49], the corresponding data and traceability requirements (center), and the associated impact topics mapped onto ESG dimensions (right). Color coding represents each ESG dimension and highlights the dominant impact focus of each regulatory instrument. Own elaboration.

3. Materials and Methods

In this research, we followed a mixed-methods approach. Our methodology is an adaptation of the Delphi procedures [54] in which the definition of impact items was obtained from a narrative literature review [55] of consolidated recent publications on sustainability in the fashion and textile industry. From these, we identified the frequency of occurrence of impact items associated with each ESG dimension using ATLAS.ti software (version 22.4; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) [56]. Then, we designed an online survey containing these impact items to be evaluated by three initial experts, who assessed the clarity and perceived importance of the items. Once corrected, we sent it to a panel of traceability experts from the fashion and textile industry (including brands and retailers, manufacturers, suppliers, NGOs, auditing companies, society, and academia) until consensus was reached (2 rounds were needed). Later, we conducted a validation of the overall clarity of the survey and its individual items with the judgment of eight experts. This process enabled the establishment of a ranking of impact items, as discussed in Section 4. We carried out the calculations using Jupyter Notebooks running on Python (version 3.12.11; Project Jupyter, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) [57]. This approach bridges abstract theoretical insights with real-world context, adding valuable nuance to traditional Delphi results. Although robust, the methodology also presents inherent constraints. The Delphi panel was relatively small, and expert selection may introduce biases related to professional background or prior exposure to traceability practices. However, these limitations were partially mitigated by the consistency of responses across both rounds, the diversity of stakeholder profiles involved, and an additional clarity check. The mixed-methods design also helps reduce methodological bias. By combining a narrative literature review with a systematic extraction and coding of impact items, the development of the constructs is grounded in independently validated evidence rather than relying solely on expert opinion. Together, these measures strengthen the applicability, robustness, and transferability of the results. The research framework describes three scenarios: exploration, analysis, and evaluation, which were conducted in seven phases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phases of Delphi-based methodology. Own elaboration.

3.1. Literature Review

The objective of this narrative review was to identify ESG-related impact drivers for traceability adoption in the fashion and textile industry. Based on this analysis, preliminary items and a conceptual framework were developed. This narrative literature review includes recent and rigorous peer-reviewed papers, technical reports, policy reports, standards, and regulations. Academic literature was complemented with industry reports, policy documents, technical studies, and white papers/playbooks, which provide timely, sector-specific data and insights. Such sources capture emerging trends, regulatory developments, and market dynamics, thereby bridging science, practice, and policy and supplying recent evidence not yet extensively addressed by academic studies. An overview of the items and framework extracted from the literature is provided in Figure 2. Once the items were developed, a screening and content-based evaluation of 69 sustainability sources with an industry focus—classified into Regulations (21), Reports (21), Standards (18), and White Papers (9)—was conducted. Impact-related items were evaluated through a systematic content analysis using ATLAS.ti software (version 22.4; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). An AI-based codification was first carried out, followed by a human-in-the-loop revision to ensure accuracy and validate consistency. We adopted this method because it provides an objective approach and produces reproducible outcomes. From the coded content, we identified the frequency of each impact item and assigned scores based on their citation frequency. This scoring was subsequently integrated into the overall prioritization framework based on the frequency of occurrence across the analyzed reports, as shown in the “Frequency, n = 69” column in Table A2 (Appendix A). This additional step in the narrative review process serves as a validation stage to determine how the frequency of occurrence of identified categories indicates the items’ taxonomic evolution and semantic meaning. The expert consultation step was built upon this phase.

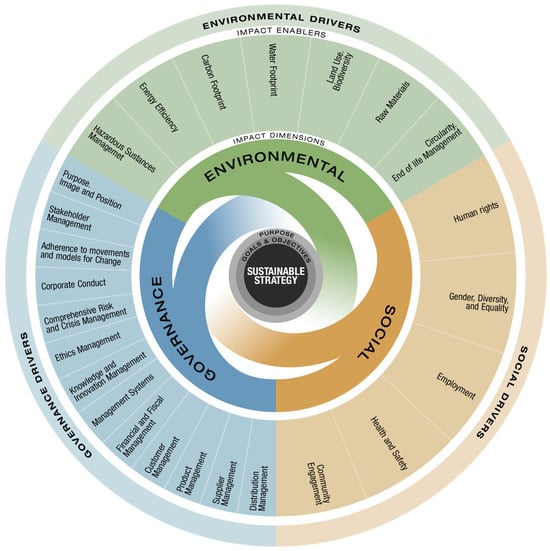

Figure 2.

ITA framework. Impact thinking for traceability adoption. Own elaboration.

3.1.1. Exploring Impact Dimensions and Drivers for Introducing Traceability Influencing Sustainable Strategy Schemes (SSC) Assessment from the Literature

Integrating scientific research and empirical data into the decision-making process can lead to more effective and sustainable strategies [58,59]. Drivers for adopting and using traceability schemes are influenced by impact contexts. ITA shows an architecture based on impact drivers that promotes effective traceability, encompassing the integration of adaptive technologies, the establishment of supportive organizational policies, the use of standardized development methodologies, and an integrated perspective on lifecycle costs and associated benefits. Conversely, several barriers can hinder progress, including the regulatory requirements, the lack of clearly defined implementation strategies, dependence on external resources, and the persistence of unsystematic practices. These limitations are shaped by Sustainable Strategy Schemes (SSC), which offer structured frameworks to guide the integration of sustainability objectives across different areas of organizational activity, thereby promoting a more harmonized and consistent application [29,37]. As illustrated in Figure 2, a structured ITA framework is presented, showing the relationship between impact drivers and traceability adoption. The research examines how aligning such practices with ESG objectives and traceability contributes not only to operational transparency but also to the advancement of sustainability performance. Each ESG dimension is further individually developed below.

Environmental

In the fashion and textile industry, the environmental dimension of sustainability centers on reducing the ecological footprint across the entire product life cycle. A critical aspect concerns the management of hazardous substances, including identifying and restricting chemicals of concern and controlling their use in production [60,61]. Traceability data helps ensure compliance with international standards and certification schemes. It also supports energy efficiency and carbon reduction by making energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions visible across production stages, thereby informing decarbonization strategies [62,63,64,65]. Intensive water use is another pressing challenge, particularly in dyeing and finishing, where traceability tools enable more precise monitoring of withdrawals, discharges, and reuse practices [66,67]. At the upstream level, mapping the origins of raw materials helps mitigate land-use pressures and biodiversity loss by identifying risks in agricultural and forestry supply chains and preventing soil degradation [68,69]. Monitoring raw material impact also supports reductions in material footprints, promotes more conscious material sourcing based on preferred fibers, and ensures transparency into origin and composition [70,71,72]. Finally, the literature highlights the role of traceability in supporting the circular transition, particularly its relevance for tracking closed-loop flows and accelerating end-of-life management [73,74], through downstream strategies such as waste valorization, recycling performance, and safe disposal practices [7,32,75,76,77,78]. From a circular governance perspective, D’Adamo et al. [79] emphasize that this transition requires not only technological solutions but also systemic governance frameworks capable of coordinating industrial actors, policy instruments, and impact assessment mechanisms.

Social

The social dimension encompasses the impacts of business operations on workers, communities, and consumers. Traceability reinforces accountability by providing verifiable data on labor conditions, equity, and community well-being. Protecting human rights remains a fundamental driver, as traceability ensures transparency in working conditions and facilitates corrective action when international labor standards are not met [44,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88]. Traceability can contribute to the collection and disclosure of workforce data to support inclusive practices and equal opportunities [27,34], as issues of gender, empowerment, and diversity are gaining increasing weight and relevance in the sustainability agenda. Employment-related aspects, including incentives, occupational protection, training, and career development, are well covered in the literature. Alongside topics such as well-being and satisfaction, the literature also addresses responsibility and commitment, where traceability plays a key role in generating and monitoring indicators of worker engagement and retention across supply chain tiers [85,89,90]. We have identified that traceability with a focus on health and safety encompasses both workplace and product conditions [41,91,92]. Finally, community engagement represents a social and governance challenge, as it is directly linked to stakeholder management. From a social perspective, it preserves interactions with local communities, respects cultural traditions, and supports efforts to sustain living standards in contexts affected by relocation or migration pressures [89,93,94]. In this scenario, traceability reinforces the need for sustainability strategies that truly protect human rights and promote equity across the value chain. However, in practice, social mechanisms often remain too weak or too vague to ensure that improvements are captured and represented in measurable indicators.

Governance

The governance dimension highlights how sustainability is integrated into corporate culture, shaping both the organizational structure and its orientation towards commitment and innovation [95]. Previous research has highlighted the importance of cultivating a culture of ethical behavior [96], noting that over-reliance on external actors can lead to solutions that do not align with corporate values and hinder the effective integration of sustainability. However, more recent empirical studies have shifted this perspective, showing how organizations are establishing governance systems to reconfigure sustainability priorities [33,97] and align governance with the collective interests of stakeholders [16]. Stakeholder engagement and collaboration have become one of the most frequently covered issues in recent research, as they are fundamental to this vision of synergistic change and support traceability initiatives that aim to demonstrate their influence on decision-making, seeking a balance between profitability and expectations [22]. Latest studies further emphasize the importance of data-driven governance in addressing both regulatory and reputational risks [34]. The existing literature offers limited observational research addressing how relational flows [19,42,98], role models, and behavioral patterns shape organizational dynamics and influence sustainability-related practices [51,99]. In this study, customers and suppliers were extracted from the stakeholder category and assigned to their own analytical groups to examine their relational impacts. Although both are formally part of the stakeholder concept, their roles, information needs, and responsibilities within traceability differ. Suppliers contribute to upstream data provision and compliance processes, whereas customers influence downstream demand, product communication, and transparency expectations. Therefore, successfully integrating traceability into the core of business requires not only internal expertise, leadership commitment, and rigorous strategic planning, but also a deeper understanding of the interplay between structural, relational, and behavioral factors.

3.2. Online Survey

After analyzing the State-of-the-Art, a survey was used to complement the literature review. A quantitative online survey was conducted, engaging key experts who provided practical perspectives on existing issues, consolidating valuable insights from experienced professionals, and uncovering unique challenges faced by different stakeholder groups. The group of experts was configured to gather opinions through a detailed questionnaire.

3.2.1. Delphi Subjects (Experts) Selection and Sample Definition

The study involved 21 stakeholders from the fashion and textile industry. The sample was largely composed of professionals from brands and retail companies, followed by individuals from auditing firms and manufacturing organizations. Most participants held executive or managerial positions and brought expertise in areas such as sustainable fashion, supply chain management, traceability, compliance, and ESG issues. We applied the Delphi method for its adaptable nature across disciplines, applicable to fashion and textiles. In addition, it is especially effective for exploring a variety of research questions, particularly in emerging areas [100,101], and is known for fostering expert consensus, which makes it perfectly suitable for the purpose analysis of this research. Although there is no universally agreed-upon ideal size for a Delphi panel, existing research suggests a range of 10 to 20 participants [102]. Some studies suggest that smaller groups of at least six participants are valuable [103,104], while groups of more than twelve may be appropriate when participants share a disciplinary background [100]. Our panel selection was based on the following criteria: professional roles, technical knowledge, and relevant expertise [101,105], to gather expert views on key concepts related to traceability, impact, and sustainability strategy. For this study, participants were intentionally selected from different areas of the global fashion and textile value chain to ensure a rich range of perspectives and insights. The final panel represented a diverse group of stakeholders, considering geographic locations, organizational types, and fields of expertise. A summary of the panel is presented in Table A2 in Appendix A. Factors influencing consensus metrics include sample size and the degree to which experts align with the group’s opinions [106].

3.2.2. Structured Questionnaire Based on Phase 1 (Literature Review)

Considering the outputs from Phase 1, the Delphi Study Questionnaire was developed based on predefined criteria, including the use of the English language, structural coherence, and content relevance. It comprises 110 questions, combining quantitative assessment via structured rating scales and predefined multiple-choice items, and qualitative insights through short-answer questions, to ensure objectivity, making it a mixed-methods instrument designed to validate and refine the impact drivers supporting traceability adoption in sustainability-focused contexts. Its structure aims to collect background information, contextual insights, and expert evaluations of impact dimensions related to traceability within the fashion and textile industry. Section 1, Background Information, includes six questions focused on the respondent’s country of residence, educational background, role in the supply chain, stakeholder group affiliation, current job position, field of expertise, and years of experience. These are mostly multiple-choice questions. Section 2, Context Information, consists of seven questions designed to evaluate expert perspectives on enabling drivers, strategic priorities, areas for refinement, barriers to implementation, and the relevance of adaptability and impact thinking in traceability adoption. These questions primarily use five-point Likert scales, with options ranging from low to high importance, appropriateness, or priority. Section 3 is the most extensive section and focuses on the Impact Dimensions Ranking, which is divided into three dimensions: Environmental, Social, and Governance, totalling 97 questions, including both Likert-scale items and open-ended inputs. Participants were asked to rank the appropriateness and the importance of each driver along a five-point Likert scale. Each point on the scale reflects a specific degree of perceived relevance, ranging from “Very Low Importance” to “Very High Importance.” A rating of 1 (Very Low Importance) indicates that the item is considered to have minimal significance or relevance. A rating of 2 (Low Importance) suggests that the item holds less-than-average importance. A score of 3 (Neutral) represents a midpoint on the scale, indicating that the respondent neither considers the item particularly important nor unimportant. A rating of 4 (High Importance) reflects that the item is viewed as having above-average relevance. Finally, a score of 5 (Very High Importance) signifies that the item is perceived as critically important and highly relevant. To control for potential sources of bias inherent to narrative review methods, experts were requested to contribute any missing impact drivers through open-ended items.

Furthermore, the questions within each dimension were presented in a structured order to ensure a coherent response flow. A progress bar was displayed to help maintain participants’ attention throughout the questionnaire, considering the high number of items. Additionally, a pre-survey was conducted with a sample of three collaborators to identify potential limitations and instrument design flaws, enabling appropriate refinements before distributing the final version to expert participants. Minor adjustments were made to enhance clarity and optimize question formulation, minimizing the risk of misinterpretation. However, no substantial modifications were introduced to the original structure or content. The complete survey instrument is available from the authors upon request.

3.2.3. Delphi Survey Round 1

The online survey was conducted through Microsoft Forms between April and September 2025. A total of 94 individuals representing key stakeholder groups within the fashion and textile industry were invited to participate. Potential participants were approached through direct email, personalized LinkedIn messages, and referrals from academic partners. Ultimately, 21 experts agreed to take part in the study. These experts were provided with clear, detailed instructions on how to access and complete the survey to ensure a smooth, consistent response process. They were also contacted individually whenever additional clarification was required or technical issues were encountered. Of the 21 experts who initially agreed to participate, 19 provided valid responses in both Delphi rounds; two responses were excluded due to inconsistencies and incomplete submissions.

A first round was carried out to evaluate the clarity and importance of the items using the Delphi method, which enabled us to capture the panel of experts’ opinions in a structured way through the questionnaire.

3.2.4. Evaluation and Analysis of Results from Rounds 1 and 2

In the Delphi process, each item was evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = lowest importance, 5 = highest importance). To assess the level of agreement among experts, both measures of central tendency and dispersion were applied. Following [107], three complementary metrics were used, as defined in [108] as follows:

Interquartile Range (IQR) is defined in Equation (1), where the first quartile corresponds to the 25th percentile of the ordered data, and the third quartile corresponds to the 75th percentile of the ordered data. A value of ≤1.0 indicated high consensus among experts.

Mean score (M), where items with an average score ≥ 4.0 were considered relevant, that is, values equal to or approximately 4.0. The percentage of agreement consisting of at least 75% of the responses within the 4–5 rating range was achieved.

Additionally, standard deviation (s) was reported as an auxiliary indicator of variability as expressed in Equation (2):

where x represents each observation, is the sample mean, n is the number of observations in the sample, and n − 1 corresponds to the degrees of freedom. The IQR therefore measures the spread of the middle 50% of the data by subtracting the lower quartile from the upper quartile. This makes it a robust measure of variability, less sensitive to extreme values and outliers than the standard deviation [108]. Consensus for an item was reached when it simultaneously met the thresholds of IQR ≤ 1.0, M ≥ ~4.0, and ≥75% agreement. Items not fulfilling one or more of these conditions were carried forward to the next round.

3.2.5. Validation of the Survey

To validate the clarity of the questionnaire, we began with an initial round of qualitative consultation with eight experts, followed by two Delphi rounds in which the consensus on the items was evaluated. Subsequently, following [109,110], we assessed the clarity of the retained items using the Item Content Validity Index (I-CVI) and Scale Content Validity Index (S-CVI). In this regard, an S-CVI = 0.865 was obtained with eight experts consulted, based on an extensive and unmodified scale of 78 items. If seven items with lower ratings were eliminated, we would obtain an abbreviated scale of 71 items with an S-CVI = 0.898, without the need for further rounds. To do this, we calculated each I-CVI according to Equation (3), where N is the number of experts who evaluate the item, and A is the number of those who rate it as acceptable (3–4 on a scale of 1–4).

The average scale validity (S-CVI) was measured using Equation (4), where M is the total number of items in the questionnaire M and is the I-CVI of item j as defined in Equation (3)

Considering that eight experts responded to the item clarity validation questionnaire, if the [106] interpretation criterion is used, an I-CVI ≥ 0.78 is considered excellent. At the same time, an S-CVI ≈ 0.90 reflects an excellent content validity scale.

In accordance with [110], we transformed the I-CVI to a modified kappa ( that adjusts for random agreement, where pc is the probability of random agreement for a threshold considered relevant. This allows items to be classified as excellent, good, or fair according to (Equation (5)).

Likewise, pc is calculated according to Equation (4), where N is the number of experts who evaluated the item, and A is the number of experts who rated the clarity of the item between 3 and 4 (Equation (6)).

With this criterion, I-CVI ≥ 0.78 is considered excellent, while S-CVI ≥ 0.90 expresses excellent validity and excellent content validity of the scale.

3.2.6. Results of Round 1

Consensus was achieved in most items because they reached the predefined thresholds. Experts’ ratings were generally consistent, showing both high average scores and low dispersion (see Table A2 in the Appendix A). Moreover, we found no redundancies, as open-ended sections confirmed that items were neither overlapping nor redundant. Most participants did not suggest new drivers, and occasional proposals were already included within broader categories. In addition, four items failed to meet the criteria:

HS4: Enhancing overall productivity and morale (IQR = 1.75; M = 3.9; 72.2% in 4–5).

CEOL2: Streams revalorization (IQR = 1.75; M = 3.7; 61.1% in 4–5).

CEOL5: Promoting regenerative systems (IQR = 1.75; M = 3.8; 72.2% in 4–5).

AAR1: Market position advantage through awards and recognitions (IQR = 2.0; M = 3.2; 38.9% in 4–5).

These results reflected high variability (IQR well above 1.0) and insufficient levels of agreement in the proportion of experts scoring in the top categories.

3.2.7. Results of Round 2

To address these divergences, a second round was conducted. Participants were shown the aggregated results from Round 1, including mean, IQR, standard deviation, and distribution of responses. They were asked to reassess their initial ratings and provide justifications or reformulations. The objectives were to re-evaluate the four items lacking consensus and to eliminate those that remained below the thresholds. Additionally, descriptive and open-ended questions were included to allow participants to suggest item reformulations and to freely express insights regarding the perceived relevance, clarity, and applicability of each impact driver within the traceability context. After completing the second Delphi round, consensus was successfully achieved for two of the four items initially flagged for insufficient agreement in Round 1:

CEOL2: 100% agreement in the 4–5 range, with a mean of 4.65 and an IQR of 1.0.

CEOL5: 88.2% agreement in the 4–5 range, with a mean of 4.53 and an IQR of 1.0.

These items were retained in the final model, as they met the established statistical criteria for consensus. It is important to note that their initial lack of consensus in the first round was not attributable to a perceived lack of relevance, but rather to limited explanatory power at that stage and insufficient convergence in expert evaluations. After reconsideration, participants aligned more closely, validating their inclusion. By contrast, the remaining two items, HS4 and AAR1, failed to meet the minimum consensus criteria in the second round as well. Consequently, they were excluded from the final framework on both statistical and conceptual grounds, given their persistently low agreement levels and limited theoretical relevance. Table A2 in Appendix A presents the Likert-scale results, with the final values for each driver after the two rounds highlighted in bold.

3.3. Scoring Process

Each impact driver was evaluated by integrating its frequency of appearance in the content analysis with the consensus level from the Delphi rounds. The scoring framework consisted of four sequential components (see the three rows on the right side of Table A2 in the Appendix A):

Firstly, we determined the Frequency Score (FS), a factor that represents how often each impact driver was cited in the analyzed reports. This normalization expresses each driver’s frequency on a 0–1 scale as in Equation (7), where is the number of times that the driver i appears in the content analysis, and represents the maximum frequency observed across all drivers.

Secondly, a Consensus Score (CS) for any survey item i was defined (Equation (8)). This index quantifies the degree of expert agreement in Delphi assessments by incorporating both central tendency and dispersion. Specifically, a median rating Mi, on a five-point Likert scale, is combined with the interquartile range IQR (Equation (1)) to represent the variability of responses.

Thirdly, the Overall Score (OS) combines citation frequency (FS) and judgment evaluations (CS) additively for each item i. Moreover, x and y represent the weighting coefficients assigned to the FS and CS components, reflecting different sensitivity scenarios (0.3–0.7, 0.5–0.5, and 0.7–0.3) (Equation (9)).

Lastly, to facilitate interpretation and comparison, the Overall Scores were normalized to a 0–10 scale. Therefore, the Scaled Overall Score (SOSi) for any item i can be computed following Equation (10), where OSi is the Overall Score of any item i and is the highest Overall Score obtained across all drivers within each scenario.

The weighting configurations were designed as exploratory scenarios rather than definitive coefficients. A symmetric weighting (0.5–0.5) was used as a neutral baseline, while asymmetric scenarios (0.7–0.3 and 0.3–0.7) were introduced to reflect alternative strategic priorities across impact dimensions. This scenario-based approach enables a transparent examination of how different emphasis levels influence the combined index, without assuming a single optimal weighting scheme.

4. Results

Secondary literature provides a preliminary conceptualization of the impact landscape, identifying the principal drivers behind traceability initiatives, as outlined in ITA’s framework (see Figure 2). Our research demonstrates that traceability has served as a unifying thread in the development of the comprehensive impact assessment framework presented. Data demands can be covered through widely traceable schemes, which we have demonstrated are not only related to operational performance but also to managerial and strategic ones, covering this integral perspective. Moreover, the framework is closely aligned with the European regulatory landscape, as illustrated in Figure 1. It is harmonized with recognized international reporting frameworks and standard setters, including GRI, ESRS, IFRS/ISSB, EFRAG, ISO, and the B Impact Assessment (B Corp) model. As we discuss in Section 2, while literature has increasingly addressed the integration of materiality in ESG information disclosure, it presents a significant limitation in its treatment of traceability as a connector to practical assessment. While the predominant focus has been on how materiality facilitates strategic alignment with sustainability goals, the results provide a detailed exploration of how traceability can enhance the precision of these assessments from an integrated impact perspective. Based on the 19 valid expert responses collected across both Delphi rounds, the results reveal a reciprocal relationship between the two research questions and demonstrate a moderately high level of consensus between the literature and the aggregated responses of the Delphi panel. Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 synthesize the results derived from the mixed-method analysis combining literature-driven frequency scores and expert consensus scores obtained through two Delphi rounds. Relevance levels (Low, Medium, High) are based on normalized Final Scores (FS), using natural breaks in the distribution (High ≥ 5.20, Medium = 4.20–5.19, and Low < 4.20).

Table 2.

Enabling environmental impact drivers for traceability adoption influencing sustainable strategy schemes (SSC) assessment. Own elaboration.

Table 3.

Enabling social impact drivers for traceability adoption influencing sustainable strategy schemes (SSC) assessment. Own elaboration.

Table 4.

Enabling governance impact drivers for traceability adoption influencing sustainable strategy schemes (SSC) assessment. Own elaboration.

5. Discussion and Implications of Findings

The results of this study reveal a structural reconfiguration of how impact considerations shape traceability adoption in the fashion and textile industry. To provide a clearer overview of the main findings, Table 5 synthesizes the key results alongside their implications for both researchers and practitioners. These findings enable practitioners to critically reflect on how traceability is currently used within their organizations, particularly from an ESG perspective and in relation to decision-making processes, regulatory alignment, and value-chain collaboration. Table 5 aligns each research question (RQ1–RQ2) with its corresponding synthesized findings (F1–F5) and practitioner-oriented implications (I1–I5). Table 5 explicitly provides an integrated understanding of how ESG dimensions collectively materially influence the mechanisms through which traceability is implemented in practice. Governance drivers shape the structural and procedural foundations required for interoperable data flows, compliance processes, and cross-tier coordination. Environmental drivers operationalize traceability by linking product-level information to hotspots such as circularity and chemical management, while social drivers anchor traceability to human rights due diligence and ethical labor practices across the value chain.

Table 5.

Summary of Findings and Practitioner Implications. Own elaboration.

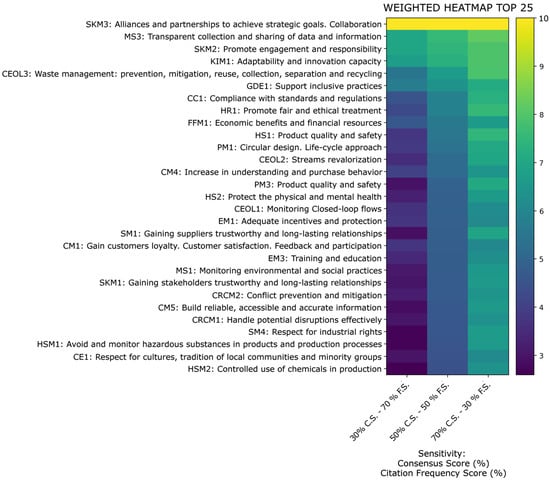

Contrary to the traditional environmental focus that dominates sustainability discourse, our findings demonstrate that governance-related impact drivers emerge as the strongest enablers of traceability implementation. This aligns with recent evidence suggesting that transparency, collaboration, and data governance are increasingly central to sustainability performance. Yet, the magnitude of this shift had not been empirically validated until now. A first key insight concerns the redistribution of relevance across ESG dimensions. An examination of the items reveals that governance-related drivers are the most predominant. Specifically, the distribution of items across ESG dimensions shows that Governance concentrates 47 items, compared to 19 items within the Environmental dimension and 13 items within the Social dimension. The predominance of governance drivers over environmental and social ones can be explained by both institutional dynamics and sector-specific regulatory pressures in the fashion and textile industry. Governance mechanisms—such as data transparency, stakeholder coordination, risk management, and compliance—are increasingly central to European sustainability policy. Regulations, including the CSRD, the ESPR, and the CSDDD, prioritize verifiable, auditable, and interoperable information flows, thereby elevating governance competencies as prerequisites for meeting disclosure and due diligence requirements. In this regulatory landscape, practitioners cannot meaningfully act on environmental or social objectives without first establishing governance structures capable of supporting reliable data collection, cross-tier visibility, and decision-making coherence. Moreover, the fashion and textile sector is characterized by fragmented, multi-tier global supply chains, where operational variability and inconsistent access to primary data make environmental and social assessments more difficult to standardize. This structural fragmentation amplifies the importance of governance as the coordinating layer that enables environmental and social drivers to be operationalized. Consequently, governance emerges not only as a category of impact drivers but as the systemic infrastructure upon which environmental and social performance depends, explaining its higher relevance and stronger consensus among experts. This finding is particularly noteworthy because sustainability discourse in the fashion and textile sector has been dominated by the environmental dimension. The literature consistently frames impact assessment through an environmental lens [64,97,123,157,166], with limited integration of social and governance aspects. While Kozlowski et al. focus specifically on environmental impacts, their observation regarding the lack of integrated and systematic assessment tools and frameworks is consistent with our findings across broader ESG dimensions, where fragmentation similarly constrains strategic evaluation and traceability adoption [64]. This finding reflects a clear transition that moves priorities from operational toward managerial concerns when we integrate risk, innovation, financial, or stakeholder considerations. This indicates a shift in how we interpret traceability requirements within ESG agendas. This reorientation also aligns with the European regulatory context discussed in Figure 1, where regulations were initially conceived to respond to environmental concerns but have progressively expanded to include social and governance dimensions. Thus, Figure 3 provides empirical support for this transition, presenting a weighted heatmap displaying the top 25 impact drivers. A sensitivity comparison is also generated under different thresholds, and an averaged score was calculated combining both methods: consensus-based scoring and citation-based scoring. While no formal sensitivity analysis was conducted, the comparison across the three weighting scenarios (0.3–0.7; 0.5–0.5; 0.7–0.3) showed consistent relative patterns, suggesting that the framework is not overly sensitive to moderate changes in weights. The results show the ranking is highly stable and not significantly affected across multiple sensitivity levels. Hence, the heatmap provides a robust interpretation of the highest-ranked impact drivers, which represent coherent and persistent priorities in both the expert panel assessments and the literature.

Figure 3.

Comparative Heatmap of the Top-25 Impact Drivers across Multi-Sensitivity Analysis.

Beyond these general patterns, two specific insights emerge when comparing expert evaluations with the literature review. A second insight relates to the integration gap between impact materiality and traceability, which becomes evident when contrasting how experts rank different impact items within the Social and Governance dimensions. While social ethics is strongly recognized—illustrated by the high relevance of HR1: Promote fair and ethical treatment (FS = 5.84)—items linked to ethics management within governance receive considerably lower scores (ETM ≈ FS 3.9–4.1). This divergence reinforces our argument that there are still limited perceptions and awareness of the relationship between corporate behavioral dynamics and traceability. In other words, ethical conduct is acknowledged as socially desirable, but experts do not yet interpret ethical governance as a structural enabler of traceability. This finding sharply contrasts with Figure 1, where regulatory frameworks such as the Whistleblower Protection and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) explicitly reinforce ethical governance mechanisms. The misalignment suggests that although regulatory activation is strong, awareness regarding ethical governance as a structural enabler of traceability remains underdeveloped. A third insight emerges in the misalignment between regulatory expectations and organizational readiness, particularly within the Environmental dimension. While waste management for revalorization reaches a strong consensus as highly relevant (FS very high), related operational mechanisms—such as safe disposal, promotion of regenerative systems, inventory reduction, and reverse logistics—score significantly lower (≈FS 4). This may have two interpretations. On the one hand, while the term “circularity” is widely accepted, used, and internalized, more technical concepts within circularity (such as “regenerative systems” or “reverse logistics”) remain less familiar or more difficult to operationalize. On the other hand, the findings reveal a structural disconnection; although logistics and distribution are recognized as essential parts of the value chain, their role in enabling circularity remains underappreciated. This lack of integration between distribution impacts and circularity activation may explain why operational mechanisms are ranked lower despite their linkage to End-of-Life (EoL) management. In practice, organizations often conceptualize circularity at the strategic level but fail to connect it to the operational infrastructures that make circularity viable. These findings expand existing research by offering a multidimensional and empirically validated model that clarifies the relational mechanisms through which traceability supports sustainability performance.

This research has several implications for practitioners. Using the ITA framework may help develop a strong SSC that would benefit overall performance, supporting the complexity faced by the fragmented and heterogeneous fashion and textile industry. Although the factors we have considered differ in scope and contextual impact, the suggested framework should enable researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to understand that global impact issues can determine a business model and value proposition. This understanding can be used to identify areas where measures are lacking, define action plans to begin addressing them, and strategically define indicators for measurement and monitoring. Similarly, this should facilitate the organization and structuring of impact areas that are often intertwined or diluted, frequently resulting in the establishment of very general or even abstract indicators. This work can also strengthen stakeholder management, as setting a clear sustainability strategy activates better dialogue, enabling the identification of key alliances and the implementation of corrective measures to better respond to stakeholder expectations. It can also foster greater flexibility and adaptability to fluctuating contexts. This ordering process enables decision-making, as clearer visualization of each area of action and its specific relevance helps prioritize and assess critical risks and anticipate potential opportunities. It assumes that practitioners interested in applying impact thinking should start in areas where they have a higher degree of control and maturity. The identification of strategic impact schemes, therefore, strengthens understanding of traceability-related relational factors and supports the answer to RQ2 in the article.

We have identified the following limitations of the study to guide further research. Although the proposed work improves understanding and communication with stakeholders, further development is needed when it comes to categorizing and attributing each strategic action to the internal or external context of each organization in order to address the identified gap of the lack of correlation between behavioral dynamics and traceability and to respond to the need to incorporate notions such as commitment and responsibility. Another key area for further research is to work with indicators and define specific Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for each impact item. Specifically, future research should explore which capabilities and mechanisms need to be activated and tailored to each specific business model. For this purpose, further research shall be considered to align the identified items with the appropriate selection of cohesive traceability schemes capable of supporting those efforts with actionable indicators. This could also help practitioners to further promote measuring and monitoring mechanisms to track their progress. This is particularly valuable for practitioners seeking to enhance traceability implementation, as it enables them to map, parameterize, and disseminate each traceability scheme while producing strategic data that reveals its diversity, operational scope, intended use, and strategic function within the organization. A better understanding of detecting whether there is dispersion or concentration of schemes, as well as measuring the effectiveness of each scheme in relation to individual items and their harmonized implications when activated collectively, could lead to new research directions.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes and validates ITA as an integrative framework that strengthens the strategic adoption of traceability within ESG-oriented sustainability strategies in the fashion and textile industry. By combining a narrative literature review, content analysis of 69 sustainability sources, and a two-round Delphi study with 19 valid expert responses, this research bridges theoretical, methodological, and stakeholder-oriented contributions. It foregrounds novel methodological pathways, including the coupling of impact assessment with traceability prioritization through an integrative ESG-oriented framework. This approach offers actionable insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing empirical evidence on how environmental, social, and, most notably, governance-related impact drivers shape the implementation of traceability across complex value chains in the fashion and textile industry. The expert consultation reveals a reciprocal and reinforcing relationship between the theoretical insights and the aggregated judgment of stakeholders, indicating a moderately high level of consensus and validating the coherence and relevance of the framework in complex industry settings.

Theoretically, the study contributes to the ESG–traceability literature by demonstrating the predominance of governance-related drivers—particularly data transparency, cross-stakeholder collaboration, and innovation capacity—in enabling traceability adoption; revealing misalignments between regulatory requirements and organizational readiness, especially within circularity and ethical governance domains; and providing a structured conceptualization of how impact drivers interact and shape SSCs. Practically, ITA provides organizations with a decision-support structure for prioritizing impact areas, assessing internal readiness, and aligning traceability initiatives with sustainability goals and regulatory frameworks. The framework can support the design of impact-aligned KPIs, strengthen interdepartmental coordination, enhance stakeholder engagement mechanisms, and guide resource allocation—particularly in scenarios where operational fragmentation challenges consistent assessment and implementation. Furthermore, the ranked list of impact drivers offers practitioners a concrete roadmap for structuring sustainability strategies anchored in traceability.

The findings reinforce the imperative of site-specific interventions, systems harmonization, and inclusive collaboration to enable scalable and long-term prosperity. Critically reflecting on study limitations, the study identifies opportunities for further research. We suggest further testing the ITA framework in real organizational contexts through multi-case studies to assess how impact drivers evolve across different strategic configurations and how the model can be operationalized in practice. In particular, future research should examine which organizational capabilities and mechanisms must be activated and adapted to different business models to effectively embed ESG-driven traceability. Likewise, subsequent studies should explore the alignment between the identified impact items and the selection of cohesive traceability schemes capable of supporting those efforts with actionable indicators. This would enable practitioners to quantify the contribution of traceability to ESG performance and analyze interdependencies among impact drivers. Ultimately, the research affirms that further investigation into organizational behavioral dynamics—such as leadership commitment, cultural readiness, and cross-functional role distribution—would help address the persistent gap between ethical aspirations and the governance capabilities required to achieve them.

This study advances a theoretically grounded and empirically validated foundation for advancing impact-aligned traceability practices. This would benefit future studies by providing empirical evidence of the interdependencies between practical impact assessment and traceability adoption, evaluating their quantitative implications for ESG performance indicators, and exploring how they can evolve within the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.-S.; methodology, M.T.-S. and D.A.R.; formal analysis, M.T.-S. and D.A.R.; investigation, M.T.-S. and D.A.R.; data curation, D.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.-S. and D.A.R.; writing—review and editing, M.T.-S., D.A.R., and J.G.-P.; validation, D.A.R.; supervision, J.G.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because anonymous expert surveys are not required under Law 14/2007 (Art. 1.a).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Aggregated data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CS | Consensus Score |

| CSDDD | Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence |

| CSV | Creating Shared Value |

| EFRAG | European Financial Reporting Advisory Group |

| EoL | End of Life |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| ESRS | European Sustainability Reporting Standards |

| EU | European Union |

| FS | Final Score |

| FrS | Frequency Score |

| GCD | Green Claims Directive |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| IFRS | International Financial Reporting Standards |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| ISSB | International Sustainability Standards Board |

| ITA | Impact Thinking Approach |

| KPIs | Key Performance Indicators |

| NGOs | Non-Governmental Organizations |

| OS | Overall Score |

| RQs | Research Questions |

| SSC | Sustainable Strategy Schemes |

| TBL | Triple Bottom Line |

| TFP | Total Factor Productivity |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Overview of Delphi Sampling.

Table A1.

Overview of Delphi Sampling.

| Sample (n = 21) | Country | Highest Degree | Stakeholder Group | Job Position | Current Area of Study/Expertise | Years of Expertise |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spain | Bachelor’s degree | Auditing Companies | Executive | Circular Economy | 5–10 |

| 2 | Spain | Master’s degree | NGOs | Management | Supply Chain Management Circular Economy | 5–10 |

| 3 | Denmark | Doctorate | Academia | Project Manager | Industrial ecology | 5–10 |

| 4 | Germany | Bachelor’s degree | NGOs | Executive | Fashion Design Sustainable Fashion Circular Economy End Of Life (EOL) | 10–20 |

| 5 | Spain | Bachelor’s degree | Brands/ Retailers | Management | Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain Management Traceability | More than 20 |

| 6 | Spain | Professional degree | Manufacturer | Senior Team Member | Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain Management Traceability Compliance | More than 20 |

| 7 | Spain | Master’s degree | Auditing Companies | Management | Supply Chain Management Compliance | 10–20 |

| 8 | Pakistan | Bachelor’s degree | Manufacturer | Management | Textile Science and Technology | 10–20 |

| 9 | Australia | Bachelor’s degree | Brands/ Retailers | Project Manager | Supply Chain Management Traceability Apparel Production and Manufacturing Compliance Sustainable Fashion | 10–20 |

| 10 | Republic of Ireland | Bachelor’s degree | Brands/ Retailers | Executive | Sustainable Fashion Circular Economy | More than 20 |

| 11 | Sweden | Master’s degree | Society | Junior Team Member | Sustainable Fashion | Less than 5 |

| 12 | Spain | Master’s degree | Suppliers | Executive | Sustainable Fashion Fashion Innovation Supply Chain Management | 5–10 |

| 13 | Hong Kong | Master’s degree | Manufacturer | Management | Fashion Design | More than 20 |

| 14 | France | Master’s degree | Society | Project Manager | Textile Engineering Circular Economy Sustainable Fashion | Less than 5 |

| 15 | Chile | Professional degree | Sector Associations | Consultant | Textile Engineering | More than 20 |

| 16 | Spain | Master’s degree | Brands/ Retailers | Project Manager | Apparel Production and Manufacturing Sustainable Fashion Circular Economy Supply Chain Management Traceability Compliance ESG Product Lifecycle End Of Life (EOL) | 5–10 |

| 17 | Spain | Professional degree | Auditing Companies | Executive | Fashion Innovation Sustainable Fashion Circular Economy Supply Chain Management Traceability | More than 20 |

| 18 | Belgium | Master’s degree | Brands/Retailers | Executive | Circular Economy Sustainable Fashion Apparel Production and Manufacturing Traceability Supply Chain Management End Of Life (EOL) ESG Product Lifecycle Compliance | 5–10 |

| 19 | Bangladesh | Master’s degree | Sector Associations | Senior Team Member | ESG Compliance Circular Economy | 5–10 |

| 20 | Sweden | Doctorate | Academia | Senior Team Member | Textile Science and Technology | 10–20 |

| 21 | Belgium | Doctorate | Suppliers | Executive | Environmental Science ESG Sustainable Fashion | 10–20 |

Table A2.

Results. Overall score.

Table A2.

Results. Overall score.

| ESG Dimension | Impact Driver | Frequency (n = 69) | Frequency Score (FrS) | IQR R1 | M R1 | IQR R2 | M R2 | Consensus Score (CS) | Weighted Overall (WO) | Final Score (FS) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1. Hazardous Substances Management (HSM) | HSM1: Avoid and monitor hazardous substances in products and production processes | 6 | 0.007712082 | 0.48 | 4.66 | - | - | 0.82016 | 0.413936041 | 4.55 |

| HSM2: Controlled use of chemicals in production | 58 | 0.074550129 | 0.78 | 4.55 | - | - | 0.73255 | 0.403550064 | 4.43 | |

| E2. Energy Efficiency (EE) | EE1: Reduce and monitor energy footprint | 29 | 0.037275064 | 0.50 | 4.38 | - | - | 0.7665 | 0.401887532 | 4.42 |

| EE2: Energy-efficient production systems | 37 | 0.047557841 | 0.68 | 4.33 | - | - | 0.71878 | 0.38316892 | 4.21 | |

| EE3: Use renewable energy | 20 | 0.025706941 | 0.66 | 4.23 | - | - | 0.70641 | 0.36605847 | 4.02 | |

| E3. Carbon Footprint (CF) | CF1: Reduce and monitor carbon footprint | 12 | 0.015424165 | 0.62 | 4.50 | - | - | 0.7605 | 0.387962082 | 4.26 |

| CF2: Prevent greenhouse gas emissions. Decarbonization | 14 | 0.017994859 | 0.51 | 4.44 | - | - | 0.77478 | 0.396387429 | 4.36 | |

| E4. Water Footprint (WF) | WF1: Reduce and monitor water footprint | 9 | 0.011568123 | 0.51 | 4.55 | - | - | 0.793975 | 0.402771562 | 4.43 |

| WF2: Water-efficient production systems. Reuse of water | 16 | 0.020565553 | 0.71 | 4.50 | - | - | 0.74025 | 0.380407776 | 4.18 | |

| E5. Land Use and Biodiversity (LUB) | LUB1: Reduce and monitor biodiversity impacts of activities | 49 | 0.062982005 | 0.68 | 4.33 | - | - | 0.71878 | 0.390881003 | 4.30 |

| LUB2: Avoid land and soil degradation | 16 | 0.020565553 | 0.61 | 4.44 | - | - | 0.75258 | 0.386572776 | 4.25 | |

| E6. Raw Materials (RM) | RM1: Dematerialization. Material use reduction | 52 | 0.066838046 | 0.85 | 4.38 | - | - | 0.68985 | 0.378344023 | 4.16 |

| RM2: Reduce and monitor material footprint | 31 | 0.039845758 | 0.62 | 4.50 | - | - | 0.7605 | 0.400172879 | 4.40 | |

| RM3: Origin, composition, and processing | 38 | 0.048843188 | 0.61 | 4.44 | - | - | 0.75258 | 0.400711594 | 4.40 | |

| E7. Circularity and End-of-Life Management (CEOL) | CEOL1: Monitoring closed-loop flows | 156 | 0.200514139 | 0.73 | 4.22 | - | - | 0.68997 | 0.445242069 | 4.89 |

| CEOL2: Streams revalorization | 102 | 0.131105398 | 0.83 | 3.88 | 0.49 | 4.65 | 0.816075 | 0.473590199 | 5.20 | |

| CEOL3: Waste management: prevention, mitigation, reuse, collection, separation, and recycling | 303 | 0.389460154 | 0.48 | 4.66 | - | - | 0.82016 | 0.604810077 | 6.65 | |

| CEOL4: Safe disposal. Type and method | 4 | 0.005141388 | 0.70 | 4.44 | - | - | 0.7326 | 0.368870694 | 4.05 | |

| CEOL5: Promote regenerative systems | 3 | 0.003856041 | 0.83 | 4.11 | 0.72 | 4.53 | 0.74292 | 0.373388021 | 4.10 | |

| S1. Human Rights (HR) | HR1: Promote fair and ethical treatment | 164 | 0.210796915 | 0.43 | 4.77 | - | - | 0.851445 | 0.531120958 | 5.84 |

| S2. Gender, Diversity and Equality (GDE) | GDE1: Support inclusive practices | 371 | 0.476863753 | 0.73 | 4.22 | - | - | 0.68997 | 0.583416877 | 6.41 |

| S3. Employment (EM) | EM1: Adequate incentives and protection | 171 | 0.219794344 | 0.76 | 4.11 | - | - | 0.66582 | 0.442807172 | 4.87 |

| EM2: Improve well-being and satisfaction | 15 | 0.019280206 | 0.70 | 4.44 | - | - | 0.7326 | 0.375940103 | 4.13 | |

| EM3: Training and education | 119 | 0.152956298 | 0.68 | 4.33 | - | - | 0.71878 | 0.435868149 | 4.79 | |

| S4. Health and Safety (HS) | HS1: Product quality and safety | 104 | 0.133676093 | 0.38 | 4.83 | - | - | 0.87423 | 0.503953046 | 5.54 |

| HS2: Protect the physical and mental health | 80 | 0.102827763 | 0.51 | 4.50 | - | - | 0.78525 | 0.444038882 | 4.88 | |

| HS3: Fosters a safe and supportive workplace culture | 59 | 0.075835476 | 0.70 | 4.44 | - | - | 0.7326 | 0.404217738 | 4.44 | |

| HS4: Enhances overall productivity and morale | 22 | 0.028277635 | 0.80 | 4.05 | 1.05 | 3.81 | 0.561975 | 0.295126317 | 3.24 | |

| S5. Community Engagement (CE) | CE1: Respect for cultures and traditions of local communities and minority groups | 73 | 0.093830334 | 0.70 | 4.39 | - | - | 0.72435 | 0.409090167 | 4.50 |

| CE2: Cultural heritage and belonging | 21 | 0.026992288 | 0.75 | 4.28 | - | - | 0.6955 | 0.361246144 | 3.97 | |

| CE3: Relocation and migration | 17 | 0.0218509 | 0.81 | 4.22 | - | - | 0.67309 | 0.34747045 | 3.82 | |

| CE4: Ensuring living conditions, maintenance of well-being | 13 | 0.016709512 | 0.70 | 4.55 | - | - | 0.75075 | 0.383729756 | 4.22 | |

| G1. Purpose, Image and Position (PIP) | PIP1: Building identity | 9 | 0.011568123 | 0.84 | 4.00 | - | - | 0.632 | 0.321784062 | 3.54 |

| PIP2: Reinforce and protect reputation | 14 | 0.017994859 | 0.84 | 3.67 | - | - | 0.57986 | 0.298927429 | 3.28 | |

| G2. Stakeholder Management (SKM) | SKM1: Gaining stakeholders’ trust and long-lasting relationships | 54 | 0.06940874 | 0.51 | 4.55 | - | - | 0.793975 | 0.43169187 | 4.74 |

| SKM2: Promote engagement and responsibility | 493 | 0.633676093 | 0.68 | 4.33 | - | - | 0.71878 | 0.676228046 | 7.43 | |

| SKM3: Alliances and partnerships to achieve strategic goals. Collaboration | 778 | 1.000000000 | 0.48 | 4.66 | - | - | 0.82016 | 0.91008 | 10.00 | |

| G3. Adherence to Movements and Models for Change (AMMC) | AMMC1: Spotlight notions of aspiration or success | 2 | 0.002570694 | 0.61 | 3.44 | - | - | 0.58308 | 0.292825347 | 3.22 |

| AMMC2: Embrace support dialogue with leadership and policymakers | 58 | 0.074550129 | 0.62 | 4.17 | - | - | 0.70473 | 0.389640064 | 4.28 | |

| G4. Awards and Recognitions (AAR) | AAR1: Market position advantage | 5 | 0.006426735 | 0.96 | 3.11 | 0.75 | 3.23 | 0.524875 | 0.265650868 | 2.92 |

| G5. Corporate Conduct (CC) | CC1: Compliance with standards and regulations | 211 | 0.271208226 | 0.51 | 4.55 | - | - | 0.793975 | 0.532591613 | 5.85 |

| CC2: Formal and informal relational models | 3 | 0.003856041 | 0.70 | 3.55 | - | - | 0.58575 | 0.294803021 | 3.24 | |

| CC3: Spotlight new role models | 2 | 0.002570694 | 0.51 | 3.53 | - | - | 0.615985 | 0.309277847 | 3.40 | |

| CC4: Aligns leadership with broader organizational values. Top-management involvement | 30 | 0.038560411 | 0.63 | 4.11 | - | - | 0.692535 | 0.365547706 | 4.02 | |

| G6. Comprehensive Risk and Crisis Management (CRCM) | CRCM1: Handle potential disruptions effectively | 68 | 0.087403599 | 0.43 | 4.22 | - | - | 0.75327 | 0.420336799 | 4.62 |

| CRCM2: Conflict prevention and mitigation | 82 | 0.105398458 | 0.46 | 4.28 | - | - | 0.75756 | 0.431479229 | 4.74 | |

| G7. Ethics Management (ETM) | ETM1: Strengthen trust | 23 | 0.029562982 | 0.73 | 4.22 | - | - | 0.68997 | 0.359766491 | 3.95 |

| ETM2: Corporate culture. Behavioral performance | 50 | 0.064267352 | 0.68 | 4.11 | - | - | 0.68226 | 0.373263676 | 4.10 | |

| G8. Knowledge and Innovation Management (KIM) | KIM1: Adaptability and innovation capacity | 460 | 0.59125964 | 0.59 | 4.33 | - | - | 0.738265 | 0.66476232 | 7.30 |

| KIM2: Amplify credibility | 17 | 0.0218509 | 0.67 | 3.72 | - | - | 0.61938 | 0.32061545 | 3.52 | |

| KIM3: Community growth and development | 47 | 0.060411311 | 0.72 | 3.94 | - | - | 0.64616 | 0.353285656 | 3.88 | |

| KIM4: Encourage a culture of continuous improvement and responsible growth | 33 | 0.042416452 | 0.81 | 4.22 | - | - | 0.67309 | 0.357753226 | 3.93 | |