Abstract

Against the backdrop of accelerating urbanisation in China, the urban-rural divide continues to widen, while cave dwellings along the Yellow River have been largely abandoned, facing the challenge of cultural erosion. This study breaks from conventional conservation approaches by empirically exploring the viability of living heritage in promoting sustainable rural revitalisation and integrated urban-rural development. Employing participatory action research, it engaged multiple stakeholders—including villagers, returning migrants, and urban designers—across 60 villages in the middle reaches of the Yellow River. This collaboration catalysed a “collective-centred” adaptive reuse model, generating multifaceted solutions. The case of Fangshan County’s transformation into a cultural ecosystem demonstrates how this model simultaneously fosters endogenous social cohesion, attracts tourism resources and investment, while disseminating traditional culture. Quantitative analysis using the Yao Dong Living Heritage Sensitivity Index (Y-LHSI) and Living Heritage Transmission Index (Y-LHI) indicates that the efficacy of collective action is a decisive factor, revealing an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic development and cultural preservation. The findings further propose that living heritage regeneration should be reconceptualised from a purely technical restoration task into a viable social design pathway fostering mutually beneficial urban-rural symbiosis. It presents a replicable “Yao Dong Solution” integrating cultural sustainability, community resilience, and inclusive economic development, offering insights for achieving sustainable development goals in similar contexts across China and globally.

1. Introduction

The accelerating wave of global urbanization has profoundly reconfigured the relationship between urban and rural areas, often relegating the latter to the role of resource reservoirs or static cultural heritage repositories for cities [1]. This dynamic exacerbates spatial inequalities and precipitates a severe crisis for vernacular heritage worldwide [2,3]. In China, this crisis is acutely embodied in the rapid abandonment and cultural erosion of cave dwellings (Yaodong) along the Yellow River Basin. More than mere vernacular architecture, these structures are carriers of local memory, ecological wisdom, and millennia of socio-cultural symbiosis [4,5]. Their hollowing-out signifies not only the loss of physical fabric but, more critically, the rupture of a ‘living heritage’—the dynamic, community-centred process of intergenerational transmission and adaptation [6,7].

Prevailing conservation approaches for such living heritage tend to oscillate between two problematic extremes: museum-like preservation that fossilizes dwellings, and tourism-led commodification that stages culture for external consumption [8,9,10]. Both paradigms overlook the core ‘living’ essence of heritage and fail to address the fundamental issue of uneven urban-rural development, treating rural areas as passive recipients or resource pools rather than active partners [11,12,13,14]. Consequently, there is a pressing need for a new framework that repositions living heritage as a catalyst for mutualistic urban-rural symbiosis [15,16,17].

This study addresses a critical gap in both theory and practice: the lack of an operational, design-led framework that effectively integrates community agency, collaborative design processes, and strategic urban-rural synergy for the regenerative transformation of living heritage. While community participation and adaptive reuse are widely advocated, robust methodologies to quantify their efficacy and link them to holistic socio-ecological outcomes are scarce [18,19]. Similarly, discussions on urban-rural coordination often lack concrete mechanisms to leverage cultural heritage as a strategic platform for reciprocal exchange [20].

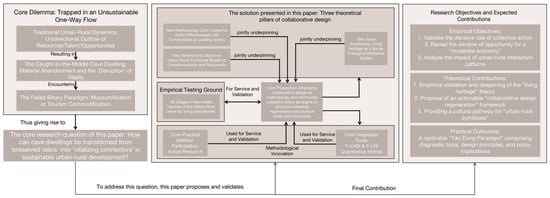

In response, we propose and empirically test a Collectively-Centered Adaptive Reuse (CCAR) framework. This framework is operationalized through a mixed-methods approach, featuring two novel diagnostic indices—the Yaodong Living Heritage Sensitivity Index (Y-LHSI) and the Yaodong Living Heritage Inheritance Index (Y-LHI). The CCAR framework is designed to (1) operationalize community collective action as a measurable core variable; (2) position collaborative design as the central mediating process that translates agency into spatial, economic, and cultural outcomes; and (3) explicitly link the regeneration of specific heritage assets to the strategic goal of fostering urban-rural symbiosis. The framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework: The “Co-Design for Regenerative Transformation” Model for Yaodong Cave Dwellings.

Conducted across 30 villages in the middle reaches of the Yellow River, this research pursues three core objectives: First, to establish and demonstrate practical models for sustainable urban-rural integration through concrete, design-led case studies. Second, to accurately identify and quantify the efficacy of community-led collective action as a critical success factor. Third, to analyze the complex relationship between local economic development levels and sustainable heritage outcomes, providing insights for nuanced policy and design interventions [21,22,23].

By bridging qualitative depth with quantitative diagnostic tools, this study aims to contribute a comprehensive and replicable ‘toolkit’ to the fields of living heritage conservation and regenerative design, offering a tangible pathway towards sustainable and symbiotic urban-rural futures.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Subsection

The Evolution of Yao Dong Value Recognition Academic research on cave dwellings originated in architectural history and anthropology, focusing on typology, construction techniques, and adaptation to the loess plateau’s water and soil environment [24,25]. Scholars termed cave dwellings “architecture without architects,” emphasising their thermal regulation and ingenious use of locally sourced loess materials [26,27]. While academically valuable, this perspective treated cave dwellings as completed relics of the past, prioritising physical form over their enduring social functions over time [28].

By the late 20th century, a global “critical turn” emerged in heritage studies, shifting focus from commemorating historical relics to living landscapes, and from material entities to integrated intangible processes [29,30]. This shift also redefined the value of cave dwellings. Influenced by UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage framework, scholars now recognise that the core value of cave dwellings, as representative vernacular architecture, lies not merely in their earthen form but in their embodiment of local memory, indigenous ecological culture, and harmonious coexistence between humanity and nature [31,32,33]. Consequently, “living heritage” has emerged as a new keyword in cave dwelling research—signifying the preservation of cultural value through sustainable, community-based residential functions, conservation measures, ritual cultures, and intergenerational transmission practices [34,35]. Accordingly, cave dwelling conservation has evolved from technical, “structure-centric” restoration to developing socio-ecological systems that sustain cultural heritage [36,37]. This pivotal shift redefines the system not as a physical relic, but as the establishment of a “chain of stewardship” connecting people, culture, and place [38].

However, living heritage faces existential threats from macro-social forces. Mainstream scholarship identifies the root cause as imbalanced urban-rural development [39]. Rapid urbanisation has triggered mass population exodus, leading to rural hollowing-out, ageing communities, and the disruption of craftsmanship and traditional cultural transmission across generations [40]. Statistical surveys reveal severe physical abandonment, with vacancy rates exceeding 60% in numerous traditional cave dwelling clusters [41]. This has precipitated multiple crises: material (structural deterioration of non-renewable earthen architecture), socio-cultural (cultural identity erosion and cultural invasion), and structural (mass exodus of human capital and assets, severely undermining rural endogenous capacity) [42]. Consequently, the current challenge transcends mere architectural conservation, demanding discussion within the complex macro-level framework of rural sustainable development and rebalancing national land planning.

2.2. Critical Impasse: Limitations of Mainstream Practice Models

In response, two dominant conservation paradigms have emerged: market-driven tourism commodification and spatial upgrading involving architectural restoration [43,44]. Tourism-oriented strategies are viewed as primary drivers of rural economic revitalisation [45]. As commodities, cave dwellings are converted into boutique hotels, homestays, or cultural experience centres [46]. While successful cases demonstrate this model’s ability to enhance visibility and generate local income, it has also faced significant academic critique [47,48]. Firstly, this model constitutes resource extraction driven by external capital. External investors and operators reap substantial economic gains while employing local villagers as low-wage labour, leading to capital flight and a severe erosion of endogenous agency. Secondly, it risks fostering “staged authenticity” where traditional culture is performed as stereotypical spectacles for tourist entertainment, severing the connection between practice and lived experience [49]. This may precipitate “gentrification driven by conservation priorities” where escalating material costs and altered social structures compel indigenous populations to relocate, ultimately creating physically intact but depopulated villages. Numerous cases of ancient villages and architectural complexes across China illustrate this acute dilemma, where tourism data growth inversely correlates with the preservation of vibrant traditional cultures [50,51].

Architectural restoration projects led by architects or designers primarily focus on the structures themselves [52]. This paradigm delivers critical technical solutions, achieving structural reinforcement, integration of modern facilities, and enhanced residential comfort while preserving the integrity and unity of the architectural language [53]. However, its limitation lies in a “material-centric bias”. While design projects gain recognition for material authenticity and spatial design, they seldom address the intangible cultural transmission of living heritage. This technical bias marginalises issues of community ownership, governance, and long-term stewardship. Disconnected from the community’s ecological heart, this paradigm risks becoming an ad hoc aesthetic solution, failing to build resilient systems [54,55].

Both paradigms share an oversimplified, unidirectional urban-rural relationship. Cities are simplistically viewed as sources of capital and tourists, while rural areas are perceived as providers of localised commodities or passive recipients. This approach fails to recognise cave dwellings as platforms for urban-rural symbiosis and mutual learning [56]. It overlooks the potential for bidirectional flows of knowledge (such as traditional ecological knowledge moving to cities, digital skills moving to villages), talent (such as returning youth and “new villagers”), and resilient economic cycles [57]. Persistent economic disparities and intensifying cultural erosion demonstrate that these paradigms do not constitute the optimal solutions for resilient, sustainable systems as envisioned by contemporary sustainability agendas [58].

2.3. Emerging Paradigms: Community Agency, Collaborative Design, and Urban-Rural Symbiosis

Regarding overcoming these limitations, cutting-edge research and exemplary practices demonstrate a growing trend towards more holistic, participatory, and collaborative integration [59].

Firstly, the regeneration of living heritage must centre on empowering community agency and collective action. This entails not tokenistic consultation, but defining local residents as primary actors in value definition, decision-making, and benefit sharing—aligning with the “people-centred” ethos of cultural policy [60,61]. Elinor Ostrom demonstrated that robust, locally evolved collective decision-making and equitable benefit-sharing systems are pivotal for managing common-pool resources [62]. This translates into practical mechanisms such as community cooperatives, heritage trusts, or profit-sharing agreements, integrated with legal and financial requirements for community stewardship [63]. A notable example is Yunnan’s Hani Terraces “A-Zhe-Ke Scheme” where villagers contribute traditional dwellings, terraces, and even household registrations as equity shares. This collective tourism management rigorously links benefits to conservation actions. Other analogous collective ownership and benefit-sharing models are actively being explored in architectural regeneration. Examples include villagers in Shenmu’s Fenghuang Village receiving rental income and employment from collectively managed cave dwellings, and the Goulan Yao Village in Jiangyong securing household income and dividends through policies transferring housing ownership to the collective [64,65].

The second paradigm shift transforms design from a service into a more strategic, participatory “co-design” approach [66]. Employing participatory design and social innovation principles, co-design redefines the designer as a collaborator who works alongside communities to translate local knowledge, visions, and agency into tangible spatial and systemic solutions. This constitutes a process of “designing with people, not for people” [67,68]. This approach fosters a sense of ownership, ensures cultural appropriateness, and builds local capacity [69]. Examples include participatory planning workshops centred on cave dwelling clusters or co-developing prototypes for adaptive reuse with villagers [70].

Thirdly, the concept of urban-rural symbiosis. This transcends core-periphery or extraction models, aiming to establish mutually beneficial relationships based on complementarity and reciprocity [71]. The cave dwelling serves as both catalyst and vessel for such relationships. It involves strategic connections facilitating two-way flows: urban markets, digital tools, and ideas, paired with rural cultural assets, ecosystems, and community labour [72]. Promising initiatives include ‘university-village’ partnerships (such as Beijing Institute of Technology collaborating with villages to introduce talent and innovative concepts), digital platforms supporting community-led narratives and e-commerce, and responsible investment approaches prioritising local connections over extraction [73,74]. Zhejiang Yunhe’s “Street-Town Co-governance” model (though focused on migrant integration) offers significant governance innovation insights for managing complex urban-rural flows and shared development processes [75]. The objective is to establish virtuous cycles, building heritage regeneration to strengthen rural communities. This empowers them to engage with urban systems from positions of resilience and shared value creation, thereby fostering regional sustainability.

2.4. International Comparative Perspectives and Theoretical Positioning of the CCAR Framework

To situate the proposed theoretical framework within the global discourse, it is instructive to briefly examine alternative paradigms from international contexts. In Europe, adaptive reuse of heritage buildings often emphasizes technical restoration and value-led approaches aligned with the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) recommendation. Projects like the conversion of historic warehouses in Rotterdam into modern apartments prioritize architectural integrity and aesthetic continuity, sometimes within strong regulatory frameworks [76,77]. While successful in preserving material fabric and integrating historic structures into contemporary urban fabric, these approaches can sometimes prioritize expert-led, top-down decision-making, potentially marginalizing deep community stewardship and long-term socio-economic adaptation [78].

Conversely, community-centric models in the Global South, such as the community-based tourism management of the Hani Terraces in Yunnan, China [79] or the participatory safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage in Oaxaca, Mexico, powerfully demonstrate the primacy of local agency and equitable benefit-sharing [80]. These models excel at fostering social cohesion and cultural continuity. However, they may face challenges in systematically integrating external design expertise or scaling up interventions without triggering commodification, and often lack the quantitative diagnostic tools to measure the ‘health’ of the living heritage system itself.

To solve this, this study proposes and validates a “collaborative design for regenerative transformation” framework tailored to cave dwelling cultural heritage. Building upon adaptive reuse techniques, this framework integrates three central conceptual strands: (1) regenerative design methodologies aimed at minimising harm and generating positive impacts on socio-ecological systems [81,82]; (2) participatory design community-centred principles advocating living heritage governance [83]; (3) an urban-rural synergistic development strategy that integrates cultural, knowledge, value, and opportunity promotion. The analysis demonstrates that empowering local communities as central custodians is essential for achieving sustainable rural revitalisation, whilst simultaneously leveraging the collaborative design process to transform stakeholders into tangible, effective outcomes.

The CCAR framework proposed in this study seeks to synthesize the strengths of these diverse approaches while addressing their gaps. Table 1 provides a structured comparison, contrasting CCAR with other dominant models.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Dominant Heritage Regeneration Models and the Proposed CCAR Framework.

2.5. Research Gaps: Towards an Integrated, Design-Led Framework

While significant progress exists gaps persist in interdisciplinary research under the new paradigm. Though community participation is advocated, studies lack robust methodologies to quantify effectiveness and directly link outcomes to holistic regeneration achievements. Design research offers technical solutions, yet gaps persist in areas requiring deep integration of socio-economic and governance models. Discussions on urban-rural coordination lack detailed, authentic frameworks for establishing rules on how to synergistically leverage the strategic role of cultural heritage [84].

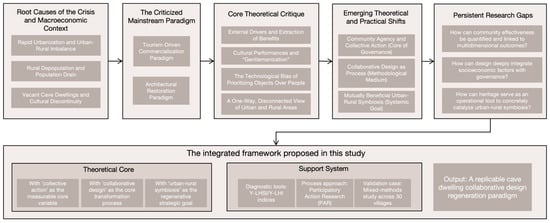

Consequently, an integrated operational framework is required: (1) operationalise community collective action as a measurable core variable; (2) position collaborative design as the central mediating process transforming agency into outcomes (spatial, economic, and cultural); (3) explicitly link the regeneration of specific heritage assets (e.g., cave dwellings) to strategic objectives for fostering urban-rural symbiosis, while providing diagnostic conditions and pathways to evaluate and advance these goals. The proposed “Collaborative Design for Regenerative Transformation” framework, integrating the Yaodong Living Heritage Sensitivity Index and Heritage Continuity Index, delivers precisely such a tailored solution meeting these requirements. This framework aims to transcend conceptualisation by offering a replicable model to transform vulnerable yaodong into community resilience and a dynamic force supporting regional sustainable development. The conceptual framework for the literature review is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework: From Critique of Prevailing Models to an Integrated Co-Design for Regenerative Transformation.

3. Materials and Methods

This study selected the middle reaches of the Yellow River Basin, which exemplifies cultural heritage while facing urgent rural transformation needs [85,86]. Employing a mixed-methods approach combining participatory action research (PAR) with spatial and quantitative analysis, multiple villages across four provinces were investigated, with rich case studies validating the findings. Two diagnostic indices represent key methodological innovations: the Yao Dong Living Heritage Sensitivity Index (Y-LHSI) and the Yao Dong Living Heritage Inheritance Index (Y-LHI). These aim to quantitatively analyse the vitality and vulnerability of entire systems, thereby bridging qualitative research with scalable diagnostic tools.

The study employs a sequential mixed-methods research design, strategically integrating quantitative spatial diagnostics, statistical modelling, and in-depth qualitative investigations. The overarching logic involves conducting a systematic condition diagnosis across a broad sample, followed by targeted case studies to reveal underlying socio-political mechanisms. The research was conducted in 30 traditional cave dwelling villages along the middle reaches of the Yellow River. The design exhibits spatial specificity and process sensitivity to capture both geographical patterns and dynamic human processes—such as decision-making, adaptation, and negotiation—related to living heritage preservation.

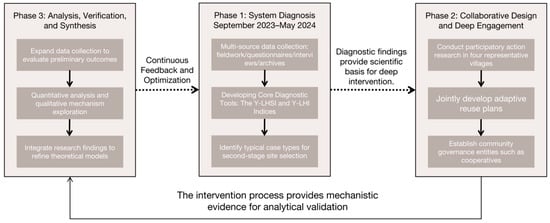

To ensure the feasibility of the technical pathway, we devised a two-year (2023–2025) work plan (Figure 3) that progresses incrementally from preliminary mapping and diagnosis to collaborative design and intervention in focal zones, culminating in cross-sectional analysis and synthesis. This approach grounds our quantitative models in reality-based fieldwork while embedding qualitative insights within broader patterns. Through participatory workshops, the research team collaborated with villagers to identify spatial functional requirements (such as a cultural salon and community archives). These shared decisions formed the core design brief for subsequent adaptive reuse design proposals.

Figure 3.

Sequential Mixed-Methods Research Design and Process.

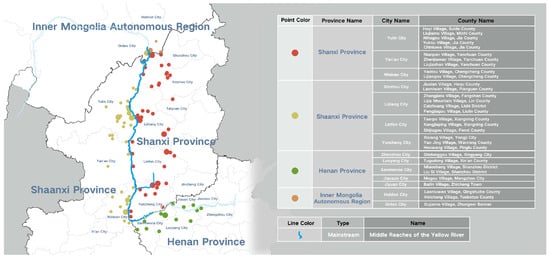

3.1. Study Area and Stratified Sampling

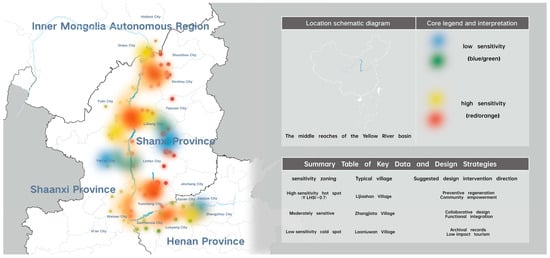

The study area encompasses the most concentrated and diverse cave dwelling settlements within the Jin-Shan Gorge of the Middle Yellow River, which simultaneously faces significant urban-rural transition pressures. To capture this heterogeneity, we employed stratified purposive sampling, selecting 30 case studies from over 200 villages identified through historical archives and remote sensing data. Stratification was based on three theoretically significant dimensions: (1) urban-rural interaction (distance from county seats, tourist numbers); (2) Economic development (village per capita income); (3) Cave dwelling settlement integrity (based on preliminary remote sensing analysis). This approach ensures the sample encompasses settlements ranging from subsistence-oriented villages remote from urban centres to suburbanised villages undergoing tourism-driven commodification, enabling robust comparative analysis. The spatial distribution of sample villages is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Spatial Distribution Map of the Study Area and 30 Sample Villages.

3.2. Data Collection: Multi-Source Triangulation Method

This study employs triangulation from four complementary sources to reduce bias and construct a comprehensive understanding.

- Questionnaire Survey: We conducted structured questionnaire surveys among households in 30 sample villages, distributing 234 questionnaires and collecting 187 valid responses. The core section of the questionnaire measured key constructs such as collective action efficacy (see Appendix A.1 for excerpts).

- In-Depth Interviews and Focus Group Discussions: We conducted 52 semi-structured in-depth interviews and 18 focus group discussions with key informants, including village elders, traditional artisans, returning youth, and village officials. Interview guides centered on cave dwelling memories, inheritance challenges, and community visions (see Appendix A.2 for interview guide examples).

- Participatory Design Workshop: To translate research into concrete design actions, we organized a participatory design workshop in Zhangjiata Village, Fangshan County. Through drawing exercises and model discussions, villagers collaboratively diagnosed spatial issues and conceived renovation proposals. Core processes and outputs are documented in Appendix A.3.

- Field Surveying and Ethnographic Research: The research team conducted on-site surveys and condition assessments of over 600 cave dwellings, collecting primary spatial and material data to construct the Y-LHSI and Y-LHI indices.

The timing, subjects, and core objectives of the aforementioned multi-source data collection are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Multi-Source Data Collection.

3.3. Core Analytical Tools: Y-LHSI and Y-LHI Diagnostic Indices

A methodological innovation of this study is the development of two complementary indices bridging qualitative concerns with quantitative measurement. The Yao Dong Living Heritage Sensitivity Index (Y-LHSI), serving as a pre-intervention diagnostic tool, assesses the vulnerability of Yao Dong socio-ecological systems to disturbance and loss of “livingness” (see Table 3 for variable details).

Table 3.

Comparison of the Y-LHSI and Y-LHI Indices: Composition, Construction, and Application.

Its calculation formula is as follows:

In this diagnostic model, D_normalised, AF_normalised, and CI_normalised represent the normalised values of cave dwelling density, living activity frequency, and community participation intensity, respectively. The weights (*w*1 = 0.4, *w*2 = 0.3, *w*3 = 0.3) were assigned via the Analytic Hierarchy Process based on judgments from a panel of ten experts, with an inconsistency ratio of less than 0.1 confirming acceptable consistency.

The Cave Dwelling Living Heritage Transmission Index serves as a tool for evaluating the comprehensive health status of the system post-intervention (or under current conditions), measuring the effectiveness of conservation and regeneration efforts at a specific point in time. Its formula is:

In this evaluation model, S_s, M_a, and C_p denote the scores for structural safety, material authenticity, and living cultural practice, respectively. The weight coefficients (0.4, 0.3, 0.3) reflect the relative importance assigned to each dimension within our conservation performance framework, as derived from the literature and the project’s theoretical focus.

Index selection is based on literature review and field validation. Index standardisation employs the minimum-maximum method to scale values to the [0, 1] interval. Weights for y-lhsi are w1 = 0.4, w2 = 0.3, w3 = 0.3, determined via the Analytic Hierarchy Process by ten experts (heritage scholars, architects, rural sociologists). The inconsistency ratio is less than 0.1, indicating acceptable consistency. The weighting process for the Y-LHSI was conducted rigorously using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to ensure methodological transparency and reduce arbitrariness. A panel of ten experts was assembled, comprising four heritage conservation scholars, three registered architects with experience in rural projects, and three rural sociologists. Each expert independently completed pairwise comparison matrices, rating the relative importance of the three core variables (Density, Activity Frequency, Community Participation) in determining a system’s sensitivity. The individual judgments were aggregated, and the final weights (w1 = 0.4, w2 = 0.3, w3 = 0.3) were derived by calculating the principal eigenvector of the aggregated comparison matrix. The consistency ratio (CR) for the aggregated judgment was 0.07, well below the acceptable threshold of 0.1, confirming the logical coherence of the expert judgments. This AHP-based weighting anchors the Y-LHSI in expert consensus, enhancing its validity as a diagnostic tool.

3.4. Integrated Data Analysis Methodology

Data analysis in this study is divided into four interconnected phases, with the software toolkits used as follows.

Stage 1: Spatial Layout Analysis. Village-level Y-LHSI and Y-LHI scores were imported into ArcGIS Pro 3.0. Kernel density estimation was employed to visualise spatial gradients, while hotspot analysis identified statistically significant clusters of high or low values, revealing spatial patterns linked to geographical factors.

Stage 2: Quantitative Modelling of Influencing Factors. Using SPSS 26, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses on Y-LHI to generate a series of models. Key independent variables included the Collective Action Efficacy Index (derived from survey sub-items concerning decision-making, benefit distribution, and dispute management), economic level, and tourism pressure. To test the “moderate economy” hypothesis, the model incorporated a quadratic term (economic level2).

Stage 3: Qualitative Mechanism Analysis. Transcripts from all interviews and focus group discussions were analysed in NVivo 12 Plus. Mixed coding was employed: first, deductive coding derived from the CCAR framework (e.g., community agency, external leverage); second, inductive coding generated from the data (e.g., generational tension, nostalgia-driven investment). This process elucidates the modes and causes within quantitative relationships, particularly in distinguishing interactive patterns.

Stage 4: Data Integration and Validation. Findings from preceding phases underwent iterative, dialogic integration. For instance, spatial cold spots with low YLHI values were cross-referenced with qualitative accounts of governance failures. Statistical outliers were examined through qualitative lenses to explore contextual nuances. This triangulation enhanced the validity and depth of conclusions.

3.5. Case Selection for In-Depth Analysis

The initial survey and spatial analysis encompassed all 30 villages. However, for comparative analysis and discussion in subsequent results sections, seven villages were deliberately selected as a subset. Selection was based on a stratified sampling strategy designed to maximise representativeness and analytical efficiency:

- 1.

- Diversity of key indicatorsSample villages were differentiated based on scores from the Cave Dwelling Living Heritage Sensitivity Index, ensuring the sample encompassed the full spectrum of vulnerability from high-sensitivity clusters to lowv sensitivity areas.

- 2.

- Representative economic contextWithin each Y-LHSI stratum, villages were selected to represent regional economic development levels (measured by per capita income), with particular attention to including cases below, within, and above the assumed ‘moderate economic threshold’.

- 3.

- Diversity of spatial and socio-cultural contextsFinally, considering the geographical location of the case villages (distance from the city centre), the villages’ demographic data, and preliminary findings on community roles and participation, this ensured the subset could encompass the principal socio-spatial dynamics present within the larger sample.

Lijia Mountain Village in Lin County, Nihegou Village in Jia County, Laoniwan Village in Qingshuihe County, Laoniwan Village in Pianguan County, Nianpan Village in Yanchuan County, and Miaoshang Village in Shanzhou District thus constitute a strategically informative cluster of typical cases. This selection ensures coverage across the full spectrum of the study’s core analytical variables—particularly the Yaodong Living Heritage Sensitivity Index (Y-LHSI) and economic development levels—from high-sensitivity, economically transitioning villages to low-sensitivity, remote settlements. This diverse yet strategically sampled subset enables a clear comparative analysis of how these core variables, alongside community agency and external interactions, interact to produce differing regeneration outcomes (The overview of the seven villages is shown in Table 4). Consequently, it allows for the testing of the proposed CCAR framework under varied conditions, strengthening the validity and transferability of the findings.

Table 4.

Profile of the Seven In-Depth Case Study Villages.

4. Results

This section presents empirical findings from a mixed-methods analysis of 30 cave dwelling villages, structured from spatial diagnostics to core drivers of regeneration. Crucially, we interpret data through an opportunity-strategy lens, elucidating not only “what it is” but also “where it is,” indicating “how” design-led interventions prove most effective and explaining why community-centred approaches succeed or fail. Evidence synthesised from spatial analysis, statistical modelling, and qualitative surveys underpins the design framework proposed in the discussion section.

4.1. Spatial Diagnosis: Identifying Priority Areas for Design Interventions

The Cave Dwelling Living Heritage Sensitivity Index applied across 30 villages yielded a spectrum of varying indices (range: 0.32–0.88, mean = 0.61, standard deviation = 0.14), serving as the basis for allocating design resources. Spatial hotspot analysis transformed the index into a usable design opportunity map, in Figure 5. Near the centre-east of prefecture-level cities like Lüliang, the sensitivity index revealed a cluster of villages with high Y-LHSI–termed “high-sensitivity hotspots”. High Y-LHSI correlates strongly with proximity to urban centres (r = 0.75, p < 0.001), indicating high pressure on these villages from population outflow. However, these villages also possess exceptionally high heritage density. This hotspot represents a priority area for preventative and regenerative design—only proactive measures can avert irreversible loss, while leveraging proximity to urban markets enables reuse.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity Spatial Distribution Map.

Conversely, in the northwest, distant from village clusters, the index forms cold spots. Their current vulnerability is low due to isolation. For designers, this suggests a different strategy: these cold spots may serve as repositories for traditional knowledge and architectural integrity. Suitable interventions here include documentation-focused projects and low-impact, community-led cultural tourism aimed at recording rather than refurbishing.

The spatial pattern of the Living Heritage Transmission Index reveals that the highest Y-LHI values occur not in the hottest or coldest spots, but in villages situated at medium distances from the city. Geographically weighted regression further unravels non-stationary relationships, supporting a context-specific approach to design solutions—rather than relying solely on universal policies: from structural reinforcement and cultural documentation in hotspot vulnerability zones, to bold repurposing and reimagining in villages where community capacity, connectivity, and stability are already established.

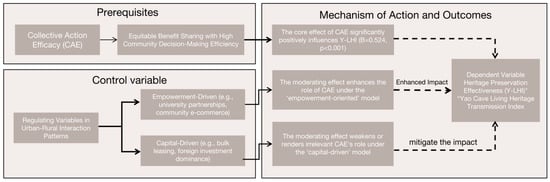

4.2. Design Catalysts: Grounded in Collective Action Effectiveness

Multivariate linear regression identified collective action efficacy as the strongest predictor of Y-LHI. This constitutes not merely a sociological finding, but a core design insight. It signifies that the success of any physical spatial design intervention ultimately hinges upon the pre-existing or co-constructed “social architecture” within the community. Decomposing CAE reveals that transparent decision-making and equitable benefit-sharing prove more critical than mere reconciliation. In design terms, participatory co-design processes and clear benefit models must be embedded from conception, not presented as fait accompli. The assessment results of the Y-LHI index and its constituent dimensions are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Living Heritage Preservation in Seven Villages Cave Dwellings.

“Qualitative” data, such as that from efficient villages like Shangfeng Village in Lin County, illustrates this point. A public maintenance “points system” designed by villagers and linked to future tourism revenues fostered a sense of ownership. This constitutes a social design in itself, preceding and enabling successful physical space transformation. It generates “social licence” and sustained momentum for subsequent workshops and conservation activities, empowering genuine resident participation. Conversely, where external investment bypasses village community governance, outcomes are described as: “a beautifully restored shell belonging to others”—a stark warning against neglecting this foundational social layer of the design process.

4.3. The “Moderate Economy” Window: Strategic Context for Design Investment

Analysis confirms an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic level and Y-LHI. An optimal ‘moderate economic window’ exists. This finding provides a critical economic filter for targeting design-led regeneration. Villages within this window possess the fundamental resources to invest in conservation while remaining economically dependent on their cultural assets, meaning community incentives align with conservation objectives. For designers and policymakers, this implies pilot projects and catalytic design investments should concentrate on such villages to amplify impact and demonstrate feasibility. Collective Action Effectiveness (CAE) scores for each dimension and overall ranking are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparative Analysis of Collective Action Effectiveness (CAE) Across Seven Villages.

Below this window, “capacity constraints” prevail, indicating that design interventions here may need to combine with basic livelihood strategies or micro-grant mechanisms to unlock community capacity. Above the window, “value displacement” occurs—as seen in Yanchuan Village, where mass tourism led to the commercialisation of rituals. At this juncture, the design intervention shifts towards mitigation and rebalancing—creating spaces or objects that can salvage cultural remnants and re-engage local participation. This might be achieved by embedding community-managed zones within tourist sites or designing experiences focused on depth rather than volume.

4.4. How Design Modulates Urban-Rural Interaction: Empowerment vs. Substitution Models

Random Forest ranked “urban-rural interaction patterns” as the second most influential factor after CAE. Moderation analysis revealed that interaction patterns significantly altered the relationship between CAE and Y-LHI. This statistically validates a core tenet of design practice: the nature of external collaboration fundamentally shapes the spatial outcomes and results of community-centred design. The relationship diagram is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

A Pathway Diagram of How Empowerment and Substitution Models Moderate Community Design Outcomes.

Villages exhibiting “community-empowering interactions”—such as those involving technical collaborations with universities or jointly owned e-commerce platforms demonstrate high positive correlations with both CAE and Y-LHI. In these instances, external designers, planners, or technical specialists function as enablers and capacity-builders; their skills are amplified through collaborative design processes, allowing local agency to flourish. External inputs are designed to integrate into community-owned visions. Conversely, “capital-driven interactions” reinforce their disconnect as external actors circumvent local governance. Here, design often devolves into a service for external masterplans, risking the creation of physically stunning yet socially hollow spaces. This dichotomy presents clear design ethical and methodological choices: pursuing processes that foster collaborative connections or accepting those that lead to displacement.

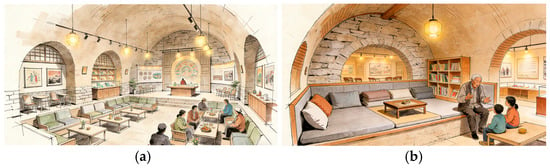

4.5. Integrated Case Study: Zhangjiata—A Blueprint for Design-Driven Symbiosis

Zhangjiata Village offers a blueprint for design-driven urban-rural symbiosis, exemplifying the synergistic operation of the aforementioned factors. Situated within a “moderate economic window” it boasts optimal connectivity. Based on the above consensus, the design intervention transformed a group of abandoned cave dwellings into a multifunctional complex. The scheme improved lighting and ventilation deep within the caves by embedding a lightweight light well, while converting the main chamber into a flexible cultural salon. The original heated brick bed (huo kang) was preserved as a vessel for cultural memory. This strategy of synergistically renovating both the physical space and its social functions was key to the project’s success. Its design regeneration emerged from a ground-up process initiated by a villagers’ cooperative, collaborating with the Research Practice Design Team from Beijing Institute of Technology in an advisory/co-design capacity, while co-creating tourism experience marketing strategies with an online travel agency.

The spatial design outcomes—a cultural salon, archive room, and homestay—emerged directly from this process, circumventing potential large-scale commodification. The design actively created a new socio-spatial feedback loop: enhancing community pride and youth engagement by 20% and 25, thereby elevating the score for living cultural practices. The cultural vibrancy embedded within the designed spaces attracted quality tourism itineraries. Revenue generated is transparently managed by the cooperative and reinvested in further conservation, demonstrating how physical design and social design interweave to produce a self-reinforcing, enduring value system. This case empirically validates the proposed “collective-centred adaptive reuse” not merely as a conservation model, but as a design framework embodying the potent forces of integrated regeneration.

5. Discussion

Our investigation of thirty cave dwelling villages reveals that living heritage regeneration should transcend technical conservation tasks, necessitating instead the cultivation of quality models fostering urban-rural symbiosis a strategic, design driven process. This study explores the collective-centred adaptive reuse model, demonstrating its feasibility while identifying essential refined conditions. This discussion synthesises these findings to articulate a practical design architecture. We contend that successful regeneration hinges upon a synergistic triadic system, with design serving as a moderator: healthy community governance forms the foundational canvas, favourable socio-economic windows constitute the strategic context, and external partnerships represent resources requiring integration through collaborative design.

5.1. Designing with, Not for, the Community: Collective Action as the Social Infrastructure of Collaborative Creation

The primacy of collective action efficacy is most explicit. For design practice, it transcends sociological observation to become a fundamental operating principle—the quality of social “infrastructure” determines the efficacy and sustainability of any spatial design intervention. Its key sub-dimensions of transparency and fairness indicate that effective regeneration requires not merely tokenistic “participation”, but the co-design of ownership models and decision-making mechanisms. This constitutes a social design act in itself, which must precede and guide spatial design. This study demonstrates that “design” plays a pivotal role in translation and catalysis within this process: it translates community collective decision-making (social architecture) into concrete, buildable spatial solutions; simultaneously, it catalyzes traditional architectural forms into cultural hubs that accommodate new functions, thereby solidifying and amplifying the outcomes of social collaboration at the physical level.

Thus, the CCAR model is primarily a design process model. It redefines the designer’s role, shifting from the production of formal transformations to the facilitation of community agency, capacity building, and visual translation. Village cooperatives embody Elinor Ostrom’s principles of commons governance. The value of design expertise is maximised when applied to enhance such endogenous governance capacities, translating them into clear, buildable spatial briefs and equitable benefit sharing mechanisms. This insight demands a paradigm shift in architectural and planning education, towards cultivating competencies in process facilitation, negotiation, and social process design beyond spatial form. This principle is exemplified in Zhangjiata Village. The villagers’ cooperative first co-designed a ‘points system’ for maintenance and benefit-sharing. This social architecture—not the physical design—became the bedrock of trust. Only then did the collaborative design process with Beijing Institute of Technology translate this social agreement into the physical layout of the cultural salon (see Section 4.5). The high Collective Action Effectiveness (CAE) score (0.81, Table 4) was a prerequisite for its high Y-LHI outcome (0.81, Table 3).

5.2. The “Moderate Economy” Window: Strategic Context for Catalytic Design Investment

The inverted U-shaped relationship between economic conditions and conservation outcomes provides a crucial strategic selector for design-led pilot initiatives: the “moderate economy” paradox identifies an optimal socio-economic inflection point where communities possess necessary resources yet remain economically dependent on their cultural assets. This aligns perfectly with community-centred regeneration as an incentive framework. For designers and policymakers, this reveals a funnel strategy: concentrating catalytic design resources and complex collaborative design efforts within this window to demonstrate feasibility and generate replicable prototypes.

This finding necessitates distinct design approaches according to economic spectrum, as illustrated by our case studies. Lijia Mountain Village serves as a prime example of operating within the identified ‘moderate economic window.’ With a per capita income near the regional average (CNY 32,100) and high Y-LHI (0.85), it possessed sufficient resources for conservation while community incentives remained tightly aligned with heritage value. This context enabled catalytic design investments, such as the integration of modern amenities into traditional structures without triggering displacement, to succeed and become replicable prototypes. In contrast, in low-income villages like Laoniwan in Qingshuihe County, design interventions required prior integration with micro-infrastructure projects to unlock basic community capacity. In high-income, high-pressure areas transformed by mass tourism, such as Nianpan Village, the design challenge shifted to mitigation and rebalancing—creating “community anchors” within tourist destinations or designing experiences prioritising cultural depth and local engagement over visitor flow. This stage-based approach ensures design resources are deployed where they can catalyse sustainable change, rather than serving merely as cosmetic enhancements or ineffective subsidies.

5.3. Design as Interpreter and Mediator of Urban-Rural Connections

The discovery of outcomes is significantly modulated by urban-rural interaction patterns, shifting focus from the quantity of exchange to its qualitative characteristics. Design possesses unique advantages in shaping these qualities.

In “Community-Empowered Interaction” external actors serve as both enablers and co-creators. Here, design functions as an interpretive and synthesising process, translating urban technical knowledge into locally appropriate solutions, and transforming rural cultural narratives into compelling spatial symbols and marketable brand identities. Mutual interpretation constitutes a critical design capacity, facilitating bidirectional value exchange: cities gain authenticity and reconnection, while rural areas receive appropriate technologies, market access, and strengthened identity.

Conversely, the “capital-driven interactions” observed in Nianpan Village demonstrate the risks of alternative models. There, external investment focused on rapid tourism infrastructure, bypassing the village cooperative. While physical restoration occurred, design served the external masterplan, contributing to the commercialisation of rituals and a sense among residents of a “beautifully restored shell belonging to others.” This case highlights how such interactions risk creating socially hollow enclaves. This dichotomy presents the design profession with an ethical and methodological choice: either to engage in building collaborative connections through co-design, or to tacitly endorse models that lead to cultural displacement. Thus, fostering sustainable integration requires designers to consciously “design” the collaborative process itself, striving to mediate and secure opportunities for community agency to become central to spatial outcomes.

5.4. Towards a Symbiotic Design Framework Centred on Living Heritage

In summary, this study posits that cave dwelling revitalisation constitutes a socio-spatial design project of the highest order. The constructed CCAR model, alongside its complementary Y-LHSI/Y-LHI diagnostic indices, collectively provide a replicable design-action framework. Effective collective governance, a moderate economic foundation, and enabling external connections form both a pre-design checklist and an ongoing evaluative lens.

Its implications are far-reaching. For design and planning, this demands long-term embeddedness and participation, alongside capacities for facilitation and socio spatial analysis. Schemes must commence with co-designed governance and benefit-sharing arrangements, making the “social architecture” the blueprint for physical space. For policy, this indicates funding programmes should support process-oriented design residencies and community capacity-building, rather than merely construction costs.

The ultimate vision is a design-curated feedback loop: living heritage regeneration strengthens community cohesion, attracting respectful partnerships willing to share benefits, thereby funding itself and empowering communities to shape their own futures. Within this cycle, the cave dwellings transform from derelict dwellings into a dynamic “urban-rural interaction hub” a physical node facilitating cultural exchange, economic reciprocity, and social learning through collaborative design. This elevates heritage conservation beyond nostalgic preservation into a forward-looking design strategy for building inclusive, resilient, and symbiotic urban-rural relationships.

6. Conclusions

The research reveals an urgent dilemma: how to regenerate moribund cave dwellings not merely structurally, but as living community vitality and a sustainable springboard for socio-urban transformation. Through a design-led mixed-methods study across 30 villages, this paper proposes and empirically tests a “collective-centred adaptive reuse” model. This prompts further reflection: heritage regeneration is not a simple technical remedy, but a socio-spatial design project. Community agency, economic context, and the quality of external collaboration must be aligned and coherent all of which can be consciously coordinated and proactively guided through deliberate design processes.

Our research distils three core principles for designing living heritage regeneration frameworks:

- 1.

- Social infrastructure is a prerequisite:Collective action efficacy is the primary determinant of success. This translates into an uncompromising design principle: The co-design of governance and benefit-sharing mechanisms must precede and guide physical interventions. Successful projects begin with designing the “social architecture”—the rules, roles, and relationships governing the space.

- 2.

- Context as a strategic filter:The identified “moderate economic window” provides a strategic lens for defining objectives and calibrating design interventions. It advocates a differentiated design approach: catalysing community-led innovation within this optimal window; integrating foundational design with livelihood support in low-income settings; and prioritising cultural reintegration and community anchoring in high-pressure, tourism-saturated areas.

- 3.

- Partnership as the design interface:The quality of urban-rural symbiotic interaction is paramount. Thus, the partnership itself—central to design—becomes a critical design task. We cultivate “community-empowered interaction” transforming external actors like designers into enablers and co-creators who facilitate knowledge and value flows. This requires positioning design at the mediating core, converting urban resources into local opportunities, and transforming local culture into shared assets.

The theoretical contributions of this work are rearticulated through a design lens:

- Methodologically, the Y-LHSI/Y-LHI indices serve both as assessment tools and participatory design support instruments, aimed at diagnosing vulnerabilities and collaboratively setting regeneration priorities with communities.

- Theoretically, it broadens the scope of “adaptive reuse” theory from physical spaces to the adaptive redesign of socio-economic relationships, shifting the focus of design thinking towards the core of socio-ecological resilience.

- Framework-wise, the CCAR model serves as an extensible design-action framework, clearly linking heritage conservation with the co-creation of new synergies between urban and rural areas.

Translating these insights into practice requires redefining roles and actions:

- For designers and planners: Actively pursue roles as process architects and facilitators. Engagement must be long-term and governed through co-designed models. Core competencies should shift towards mediating diverse interests, visualising complex systems, and prototyping new community functions and revenue models (beyond mere buildings).

- For policymakers: Move beyond funding built outcomes to support process-oriented design residencies, community capacity-building, and platform services for enabling partnerships. Policies should incentivise co-designed outcomes demonstrating improved community governance and shared benefits.

- For communities and external partners: Invest in establishing legitimate, inclusive collective institutions as primary vehicles for interaction. Pursue partnerships grounded in mutual learning and respect for local agency, treating heritage as a platform for negotiating new social contracts with external stakeholders.

This study has several limitations. First, its empirical focus is on the middle Yellow River region; the transferability of the CCAR framework and the specific ‘moderate economic window’ to other socio-cultural and geographical contexts requires further validation. Second, while the Y-LHSI and Y-LHI indices operationalize key dimensions of ‘livingness’, capturing its full, dynamic qualitative essence remains a methodological challenge. Future research should employ longitudinal design ethnography to trace the evolution of co-designed spaces and social dynamics over time, and test the framework in diverse heritage settings to refine its generalizable principles.

In summary, the cave dwelling revitalisation case offers profound insights: the most crucial design intervention may not be constructing more new buildings, but designing and empowering the underlying social, economic, and relational structures that sustain them. By empowering communities to become co-designers of their own futures and integrating them with relational structures (such as partnerships) that facilitate equitable value exchange, abandoned cave dwellings can be transformed into living “urban-rural hubs”. These hubs exist not merely as tourist attractions but are designed to perpetuate cultural continuity, community resilience, and a new, more equitable model of integrated development. Thus, living heritage regeneration emerges as a pioneering practice in design intervention, offering a tangible pathway towards a sustainable and symbiotic future.

7. Conference Proceeding

An earlier version of this research, focusing on the preliminary conceptual framework of a collectively-centered adaptive reuse approach, was presented at the Rural Revitalization Symposium 2025 [87]. This article constitutes a substantially expanded and revised study, incorporating extensive empirical data from 30 villages, the development and application of the Y-LHSI and Y-LHI diagnostic indices, a comprehensive comparative case analysis, and the formulation of the integrated CCAR design-action framework presented herein.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and J.Y.; methodology, L.Z.; software, L.Z.; validation, L.Z., Z.O. and Y.W.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, L.Z.; resources, L.Z.; data curation, L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, L.Z.; funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived by the Medical and Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Beijing Institute of Technology for this study due to its non-invasive and anonymous questionnaire studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by project funding from the Research Institute of Beijing Institute of Technology. During the preparation of this study, the authors used Doubao AI (https://www.doubao.com/) for the purpose of assisting in the creation of schematic sketches presented in Appendix A.3. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCAR | Collectively-Centered Adaptive Reuse |

| Y-LHSI | Yaodong Living Heritage Sensitivity Index |

| Y-LHI | Yaodong Living Heritage Inheritance Index |

| C-AE/CAE | Collective Action Effectiveness |

| PAR | Participatory Action Research |

Appendix A

This appendix provides core research tool samples and key process documentation referenced in the “Materials and Methods” section of the main paper, ensuring the traceability and reproducibility of the research process. Content excerpts from the villager survey questionnaire, examples of semi-structured interview outlines, and the proceedings and on-site photographs from the inaugural participatory design workshop conducted in Zhangjiata Village. Corresponding descriptions in the main text can be found in Section 2.2 and Section 3.3.

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Village Resident Survey Questionnaire (Excerpt).

Table A1.

Village Resident Survey Questionnaire (Excerpt).

| Name | Description | Questionnaire Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village Resident Survey Questionnaire (Excerpt) | This questionnaire employs stratified random sampling and was distributed across 30 target villages. It comprises four sections: basic information, perception of cave dwelling conditions, willingness to participate in community activities, and expectations for development. The following excerpts represent core sections of the questionnaire. | No. | Question Statement | Measurement Scale (1–5 points) |

| C1 | I believe the old cave dwellings in the village hold significant cultural and historical value. | 1 = Strongly disagree 2 = Somewhat disagree 3 = Neither agree nor disagree 4 = Somewhat agree 5 = Strongly agree | ||

| C2 | I am willing to participate in cave dwelling maintenance or renovation activities organized by the village collective. | |||

| C3 | I believe that the benefits generated from cave dwelling renovations should be distributed fairly among all villagers. | |||

| E1 | I support converting some unused cave dwellings into guesthouses or public cultural spaces. | |||

| E2 | I am concerned that tourism development may disrupt our traditional way of life and cultural heritage. | |||

| … | … | … | ||

Appendix A.2

Interview guides tailored to different respondent groups (veteran artisans, returning youth, ordinary villagers) were designed with distinct focuses to gather in-depth qualitative data.

The core design principle of this guide is to piece together a multidimensional portrait of traditional craftsmanship—its past, present, and future—through the diverse perspectives of these distinct communities. Excerpted guide as follows:

Table A2.

Semi-Structured Interview Guide (Excerpt).

Table A2.

Semi-Structured Interview Guide (Excerpt).

| Respondent Group | Core Questions |

|---|---|

| Veteran Craftsman | Could you describe in detail the specific steps and secrets of a key technique you excel at but may rarely use today—such as a particular arch construction method or plastering skill? |

| Over the decades of your apprenticeship and career, what fundamental shifts have you observed in the very “needs” this craft serves—for instance, people’s expectations for cave dwellings? | |

| Looking back, what do you consider the golden age of this craft? How did craftsmen collaborate during that time? How was your work valued by society? | |

| Have you ever taken on apprentices? In your view, what is the most significant hurdle for young people learning this craft today? (Is it the skill itself, economic returns, or something else?) | |

| If you could leave something behind for future generations to inherit from this craft, what would you most wish to document or preserve? (It could be a tool, a set of mantras, or a spirit.) | |

| Ordinary Villager | How long has your family lived in cave dwellings? In your childhood memories, which corner of the cave was the coolest in summer and the warmest in winter? Are there any family stories related to this? |

| In your view, what makes a cave dwelling a “good cave dwelling”? Besides sturdiness, what other criteria matter? (For example, feng shui, lighting, or proximity to neighbors?) | |

| Was it a major event when a family in the village dug a new cave dwelling or repaired an old one? How did villagers help each other? Were there any customary rules or rituals? | |

| How do the materials and methods used for new or renovated cave dwellings in the village today differ from the past? Which changes do you think are positive, and which ones do you find regrettable? | |

| Returning Youth | What motivated you to return to your hometown and pursue work related to cave dwellings and traditional crafts? Was there a pivotal moment or event that led to this decision? |

| When you first applied your modern knowledge—such as design, engineering, and internet technology—to your hometown’s traditional crafts, what was the most significant clash or the most surprising point of alignment? | |

| In your practice or entrepreneurship, what new concept did you find most difficult to persuade older artisans to accept? Conversely, what principle did they insist on that ultimately made sense to you? | |

| How do you introduce and explain your hometown’s cave dwelling culture to friends or clients from outside the region? Which aspect do you emphasize most? (Is it comfort, cultural uniqueness, or environmental value?) |

Appendix A.3

Table A3.

Participatory Design Workshop Process Documentation (Case Study: Zhangjiata Village).

Table A3.

Participatory Design Workshop Process Documentation (Case Study: Zhangjiata Village).

| Description | Activity Showcase |

|---|---|

| This document records the key stages and outputs of the inaugural collaborative design workshop held in Zhangjiata Village in November 2023. | Activity 1: Memory Map Creation. Invite villagers to mark locations holding collective memories on satellite imagery (e.g., the ancient locust tree, the old mill). |

| Activity 2: Requirement Card Ranking Villagers vote to rank functional cards such as “Guesthouse,” “Tea House,” “Library,” and “Workshop.” | |

| Activity 3: Collaborative Sketching. Designers and the villager group jointly sketch spatial layouts for the highest-voted “public cultural salon” function (see Figure A1). |

Figure A1.

Initial concept sketch for the “Cultural Salon” co-created by Zhangjiata Village residents and the design team (Image generated by AI). (a) Conceptual Diagram of the Village Reading Experience Zone; (b) Conceptual Diagram of the Interaction Zone. The authors used Doubao AI for the purpose of assisting in the creation of schematic sketches presented in Appendix A.3.

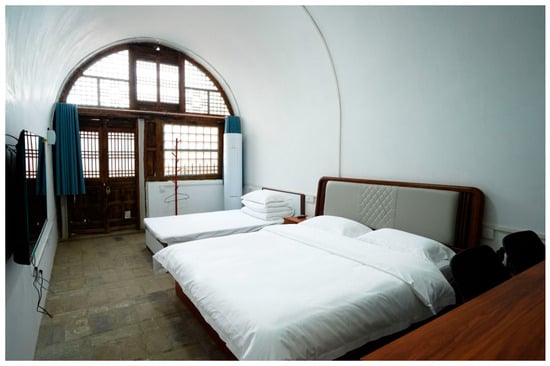

Appendix A.4

Visual Documentation of Case Study Transformations.

This section provides visual evidence of the physical transformations discussed in the case studies, primarily focusing on Zhangjiata Village.

Figure A2.

Adaptive Reuse Transformation of Cave Dwellings in Zhangjiata Village. (a) Before intervention: The original facade of an abandoned cave dwelling. (b) After intervention: The same structure transformed into the entrance of the ‘Cultural Salon’, featuring improved lighting and a restored entrance arch.

Figure A3.

Preserved Architectural Detail in Lijia Mountain Village.

The interior of a successfully restored cave dwelling in Lijia Mountain Village, showcasing the preserved traditional kang (heated bed) and the authentic loess arch structure, which now functions as a community guest room.

References

- Lin, Y.; Chen, J.F. From the perspective of historical urban landscape layering, strategies for protecting ancient towns: A case study of Chikan Ancient Town in Jiangmen City. China Urban Planning Society People’s City, Planning Empowerment. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Urban Planning Annual Conference (18 Small Town Planning), Hangzhou, China, 5–8 July 2024; Guangzhou Urban Planning Survey and Design Research Institute: Guangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the World. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeayter, H.; Mansour, A.M.H. Heritage conservation ideologies analysis—Historic urban landscape approach for a Mediterranean historic city case study. HBRC J. 2018, 14, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wu, C. The current situation and development trends of research on Chinese village culture. Sci. Soc. 2014, 6, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Xu, M. Characteristics and influencing factors on the hollowing of traditional villages—Taking 2645 villages from the Chinese traditional village catalogue (Batch 5) as an example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Xia, H.; Miao, J.; Yang, J. Changes of the ecological environment status in villages under the background of traditional village preservation: A case study in Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. Resident perceptions in the urban-rural fringe. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Q. Influencing factors of traditional village protection and development from the perspective of resilience theory. Land 2022, 11, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.-F. Reflections on the Protection and Development of Traditional Chinese Villages in the Context of Rural Revitalization. Archit. Cult. 2023, 2023, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Jiang, X.-J.; Huang, J.-C.; Liu, H. Research on Tourism Planning of Traditional Village Space Based on Syntax Analysis: Take Xixiangping Village of Linzhou City in Henan Province as Example. Areal Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Naheed, S.; Shooshtarian, S. The role of cultural heritage in promoting urban sustainability: A brief review. Land 2022, 11, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Liu, F.; Yang, C.; Cheng, Y.X.; Shen, J. Challenges and trends in the preservation and utilization of traditional villages in rapidly urbanized area: A case study of the Pearl River Delta. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1867–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Xu, J.B.; Yang, W.Y.; Cao, X.S. Study on the spatial correlation between traditional villages and poverty-stricken villages and its influencing factors in China. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 3156–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-B.; Wu, M.-M.; Li, X.; Wu, Z.C.; Li, W. Cognitive Reconstruction and the Evolution of Tourism Innovation in Traditional Village Community: A Case Study of Zhangguying Village in Hunan Province. Areal Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 92–96+102. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Herman, S.S.B.; Salih, S.A.; Ismail, S.B. Sustainable characteristics of traditional villages: A systematic literature review based on the Four-Pillar theory of sustainable development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Li, Q.; Li, M. Evaluation and development strategy of urban-rural integration under ecological protection in the Yellow River Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 92674–92691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Chu, S.; Du, X. Safeguarding traditional villages in China: The role and challenges of rural heritage preservation. Built Herit. 2019, 3, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Fei, X.; Luo, L.; Kong, X.; Zhang, J. Social network analysis of heterogeneous subjects driving spatial commercialization of traditional villages: A case study of Tanka Fishing Village in Lingshui Li Autonomous county, China. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Y.; Yang, K.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Jin, T. Spatio-temporal dynamic characteristics and revitalization strategies of characteristic protection villages in China: Based on the perspective of population ecology. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 2203–2220. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Lu, L. Probing the long-term evolution of traditional village tourism destinations from a glocalisation perspective: A case study of Wuzhen in Zhejiang province, China. Habitat Int. 2024, 148, 103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyaswari, M.; Susanto, S.F.; Nusantara, W.; Agustina, I. Integration of Local Wisdom in Sustainable Tourism Development Strategy in the Traditional Village of Ende Tribe. In International Joint Conference on Arts and Humanities 2024 (IJCAH 2024); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2025; Volume 2, pp. 1675–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, N. Urban and rural event tourism and sustainability: Exploring economic, social and environmental impacts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Chen, M.H.; Su, C.H.J.; Zhi, Y.; Xi, J. Effects of rural revitalization on rural tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wu, Y.; Bian, C.; Gao, X. Spatial characteristics and influencing factors of Chinese traditional villages in eight provinces the Yellow River flows through. River Res. Appl. 2023, 39, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Liu, Y. Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages Distribution in the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, X.; Tian, Y. The Impact of Spatial Models on the Thermal Environment of Rural Residential Buildings During Summer: A Case Study of Guanzhong Area, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, F.; Zhang, L. Comparative analysis on energy consumption of typical residence in rural areas of Northern China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2011, 27, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ning, Q. Triple understanding of Guanzhong Narrow Courtyard and its house space. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselberger, M.; Krist, G. Applied Conservation Practice Within a Living Heritage Site. Stud. Conserv. 2022, 67, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, W. A scientometric review of cultural heritage management and sustainable development through evolutionary perspectives. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, D. Evaluation on cultural value of traditional villages and differential revitalization: A case study of Jiaozuo City, Henan Province. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, J.; Zhu, Y. Research on the paradigm of traditional villages protection based on dynamic integrity. Urban Dev. Stud. 2024, 31, 8–13+33. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, R. The spatial relationship characteristics and differentiation causes between traditional villages and intangible cultural heritage in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Deng, Y.; Lin, M.; Zhang, C. A new approach to protecting historical and cultural towns and villages. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2018, 3, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S. Research on the Protection Planning of Traditional Villages with Artistic Characteristics in Regong from the Perspective of Historic Townscape (HUL). Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, K.E.; Antariksa; Marjono; Sukesi, K. The Development of HUL (Historic Urban Landscape) concept for community based conservation in Surabaya City. Evergreen 2024, 11, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Place Attachment and Landscape Improvement of Historical Places in Hui’gang Traditional Village of Hangzhou: Based on Multiple Stakeholders’ Perspective. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- China Social Sciences Network. Ethical Reflections on the Digital Preservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://www.cssn.cn/zkzg/zkzg_gxzkdzyx/zkzg_gxdzyx_yc/202505/t20250519_5874570.shtml (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Hauschild, M.Z.; McKone, T.E.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K.; Hald, T.; Nielsen, B.F.; Mabit, S.E.; Fantke, P. Risk and sustainability: Trade-offs and synergies for robust decision making. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, X. Improving the Framework for Analyzing Community Resilience to Understand Rural Revitalization Pathways in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 94, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, P.; Dou, Y.; Zeng, C.; Chen, C. Research progress on transformation development of traditional villages’ human settlement in China. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1886–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Sun, Y. Governing for spatial reconfiguration in tourism-oriented peri-urban villages: New Developments from three cases in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Clarke, N.; Hracs, B.J. Urban-rural mobilities: The case of China’s rural tourism makers. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 95, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Duan, L.; Liritzis, I.; Li, J. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Yellow River Basin. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zuo, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z. Evaluation and prediction of the level of high-quality development: A case study of the Yellow River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kang, K.H. The interaction effect of tourism and foreign direct investment on urban-rural income dis parity in China: A comparison between autonomous re gions and other provinces. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juschten, M.; Hössinger, R. Out of the city-but how and where? A mode-destination choice model for urban-rural tourism trips in Austria. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Duignan, M. Progress in Tourism Management: Is urban tourism a paradoxical research domain? Progress since 2011 and prospects for the future. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Shekari, F.; Mohammadi, Z.; Azizi, F.; Ziaee, M. World heritage tourism triggers urban-rural reverse migration and social change. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, K.; Gan, C.; Ma, X. The Impacts of Tourism Development on Urban–Rural Integration: An Empirical Study Undertaken in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Land 2023, 12, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Nijkamp, P.; Lin, D. Urban-rural imbalance and tourism-led growth in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 64, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Ryan, C.; Deng, Z.; Gong, J. Creating a softening cultural-landscape to enhance tourist experiencescapes: The case of Lu village. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.H. A study on the design development of rural and traditional village for sightseeing resources. Arch. Des. Res. 2006, 19, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Tian, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, F.; Arif, M. Study of the Evolving Relationship Between Tourism Development and Cultural Heritage Landmarks in the Eight Chengyang Scenic Villages in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guan, C.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.; Ye, C.; Zhu, C.; Li, S.; Wang, K.; Gan, M. Spatial Identification and Evaluation of Rural Vitality from a Function-Element-Flow Perspective: Evidence of Lin’an District in Hangzhou, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 1228–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Tuo, S.; Lei, K.; Gao, A. Assessing quality tourism development in China: An analysis based on the degree of mismatch and its influencing factors. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 9525–9552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]