Abstract

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) in e-commerce has intensified data-driven personalization, raising important questions about its psychological implications for consumers and its role in shaping sustainable and responsible digital business practices. This study examines how AI-driven personalization affects consumer psychological well-being in the Turkish e-commerce market and investigates the roles of privacy concerns and brand trust in shaping this relationship from a social sustainability and responsible AI perspective. The research develops and empirically tests an integrated model comprising perceived personalization, privacy concerns, psychological well-being, and brand trust. Survey data from 400 active e-commerce customers were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Findings show that both perceived relevance and perceived specificity significantly enhance psychological well-being by reducing cognitive overload and increasing perceived value. However, these personalization dimensions also increase privacy concerns, with perceived specificity exerting a notably stronger effect. Privacy concerns negatively affect psychological well-being and competitively mediate the relationship between personalization and well-being, reflecting the Personalization–Privacy Paradox in AI-driven e-commerce contexts. Moreover, brand trust significantly moderates this dynamic by weakening the harmful impact of privacy concerns on psychological well-being. Overall, the findings indicate that privacy concerns represent a latent social cost that can undermine the long-term sustainability of data-intensive business models when not governed by trust-based mechanisms.

1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) in e-commerce has enabled digital retail to evolve into a highly personalized ecosystem. Algorithms developed in this direction have enabled the analysis of large behavioral datasets, thereby facilitating tremendous growth in personalization by enabling tailored recommendations, dynamic pricing, and adaptive interfaces [1,2,3]. As a result, AI-driven personalization has become a central mechanism through which firms pursue operational efficiency and competitive advantage in digital markets. Globally, e-commerce retail sales accounted for 18% of the total retail market in 2017, and the growth of e-commerce has accelerated because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with this figure expected to reach 41% by 2027 [3]. Supported by recommendation systems developed with machine learning, predictive analytics tools, and generative assistants such as Zalando’s ChatGPT Fashion Assistant and Alibaba’s Taobao Wenwen, the AI e-commerce market, which was worth between $4–6 billion in 2022, is expected to quadruple by 2032, reaching $18–22 billion [1,4]. Innovations in personalization reduce cognitive overload among consumers and increase relevance; therefore, personalization has become one of the most important components of competitive strategies for e-retailers [2,5]. Beyond efficiency gains, however, the widespread adoption of AI-driven personalization fundamentally reshapes how consumers experience digital platforms at a psychological level, raising critical questions regarding its ethical, societal, and sustainability-related implications in data-intensive digital markets.

Turkey’s transition to digital commerce is becoming increasingly evident, particularly in the online retail sector. In 2024, the share of domestic e-commerce volume in the gross domestic product (GDP), as announced by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK), was 6.5%. The ratio of e-commerce to overall trade was also announced as 19.1% for the same year [6]. While the growth rate of retail e-commerce across Europe is 18%, the growth rate in Turkey is much higher at 7% [7]. The fact that e-commerce has become so important in a country with a young and large population is a crucial issue for local and global brands in the market. Currently, oligopolistic platforms such as Trendyol and Hepsiburada, the largest local players in e-retail, have begun using artificial intelligence for dynamic pricing, chatbots, and hyper-personalized recommendations. Rather than serving as a test of culturally unique mechanisms, this context provides a high-intensity, data-intensive e-commerce environment in which the psychological consequences of AI-driven personalization are particularly relevant. These characteristics position Turkey as a suitable empirical setting for extending AI-driven personalization research beyond predominantly Western markets.

However, this data-intensive paradigm leads to a significant problem, particularly the Personalization-Privacy Paradox. In this context, consumers desire tailored experiences to enhance satisfaction and engagement; however, they express concerns regarding surveillance, algorithmic opacity, data inference, and microtargeting [8,9,10]. Such concerns extend beyond transactional discomfort and represent a broader ethical and social challenge for the social sustainability and responsible governance of AI in consumer markets. These concerns undermine psychological well-being, encompassing hedonic pleasure, eudaimonic flourishing, autonomy, and self-efficacy through mechanisms such as reactance, fatigue, and reduced agency in technology-mediated consumption [11,12,13]. Consumer psychological well-being thus represents a core indicator of social sustainability in digital commerce, reflecting the extent to which AI-enabled personalization supports long-term human welfare rather than short-term engagement optimization. Trust in brands plays a vital psychological role in reducing uncertainty and influencing privacy assessments to maintain loyalty in the face of these complexities [5,14,15]. Trust may function not only as a risk-mitigation heuristic but also as a relational governance mechanism that stabilizes consumers’ psychological well-being under intensive data use.

Despite the existence of many studies on the topic, most studies cover the market conditions of developed countries, neglecting emerging economies such as Turkey [5,16,17]. In Turkey, the integration of artificial intelligence aligns with the nation’s culturally ingrained digital proficiency, while also encountering regulatory delays. Cross-cultural disparities are prevalent; for instance, Egypt-centric personalization-trust models necessitate a comparative examination of privacy norms and technological literacy [5]. However, these contextual factors have rarely been examined as analytical components within AI-driven personalization models. Existing research has predominantly examined AI-driven personalization through behavioral outcomes (e.g., adoption, satisfaction, intention), leaving consumer psychological well-being underexamined as a core theoretical outcome. Existing studies offer limited integration of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being frameworks in conjunction with privacy calculus and trust moderators [8,17,18]. Research specific to Turkey is still in its early stages, often overlooking the psychological trade-offs associated with personalization on platforms such as Trendyol, despite its utility [2,19].

Although prior research acknowledges the benefits and risks of AI-driven personalization, three important gaps exist. First, personalization is frequently treated as a unidimensional construct, providing limited insight into whether different personalization attributes activate distinct psychological mechanisms. Second, consumer psychological well-being has rarely been positioned as a central outcome of AI-driven personalization, despite its relevance in evaluating social sustainability in data-intensive digital markets. Third, existing studies have not sufficiently integrated personalization benefits, privacy-related costs, and trust-based governance mechanisms within a single explanatory framework, particularly in high-growth emerging e-commerce contexts, where platform dominance and intensive data use are prevalent. Consequently, it remains unclear how different forms of AI-driven personalization simultaneously generate psychological benefits and costs, and under what conditions these effects translate into enhanced or diminished consumer well-being.

Addressing these gaps, this study advances theory by conceptualizing AI-driven personalization as a dual-edged psychological and sustainability-relevant mechanism. Rather than treating personalization as a homogeneous construct, the study distinguishes between perceived relevance and perceived specificity as two analytically separable dimensions of AI-driven personalization. It examines how these dimensions differentially influence consumer psychological well-being directly and indirectly through consumer privacy concerns. Additionally, brand trust is theorized to be a key moderating mechanism that shapes how privacy-related costs translate into psychological well-being. These contributions position consumer psychological well-being as a central outcome of the personalization–privacy calculus and extend prior research by empirically examining these relationships in a non-Western, rapidly digitalizing e-commerce environment.

Guided by these considerations, this study examines how different dimensions of AI-driven personalization (perceived relevance and perceived specificity) shape consumer psychological well-being through consumer privacy concerns and how brand trust moderates this process in data-intensive e-commerce environments.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. AI-Driven Personalization in E-Commerce

AI-driven personalization in e-commerce refers to the use of advanced artificial intelligence algorithms to tailor content, product recommendations, pricing, and user interfaces to individual consumers based on their behavioral data, preferences, and interactions [2,3,10]. Fundamentally, this process employs mechanisms such as machine learning, recommender systems, and predictive analytics to examine extensive datasets, including browsing history, purchase patterns, and real-time engagement, to deliver highly relevant experiences [3,20]. Recommender systems, a fundamental component of this methodology, utilize techniques such as collaborative filtering, which aligns users with similar profiles, content-based filtering, which proposes items similar to previous preferences, and hybrid models that integrate both methods to enhance accuracy [10,21]. Machine learning facilitates continuous adaptation through techniques such as clustering, classification, and deep neural networks. Concurrently, predictive analytics is employed to forecast future behaviors, thereby enabling the preemptive customization of offerings, including dynamic pricing and personalized search results [2,4]. These technologies have transitioned from rule-based segmentation to data-driven, real-time personalization, thereby enhancing platforms such as Amazon’s recommendation engine, which substantially increases conversion rates [3,22].

The rapid ascent of personalization within digital commerce on a global scale has been remarkable, driven by substantial expansion in e-commerce. Companies such as Amazon, Netflix, and Alibaba are leading the way. They use AI helpers to reach millions of users and keep them interested [4]. By 2023, the integration of AI-enhanced personalization had become widespread, with platforms employing machine learning to develop multivariant user interfaces and conduct behavioral tracking, thereby surpassing traditional product recommendation systems [3,21]. This advancement reflects a broader trend in digitalization, wherein billions of individuals engage in online shopping daily, necessitating seamless and adaptive experiences among an abundance of choices [3].

Personalization has emerged as a central marketing strategy owing to its proven ability to reduce cognitive load, optimize relevance, and improve consumer outcomes. In an age characterized by an abundance of information, artificial intelligence serves to filter extraneous data by offering relevant recommendations, thereby facilitating decision-making and reducing the phenomenon of choice paralysis. This is exemplified by intelligent search engines that prioritize items that match user queries [20,23]. This relevance boosts engagement, satisfaction, and loyalty; customized recommendations align with core needs, increasing click intentions, repeat purchases, and lifetime value [2,21]. Firms leveraging AI report up to 40% revenue gains and 20% satisfaction lifts, outpacing competitors through precision targeting that fosters perceived value and emotional connections [24,25]. In contrast to mass marketing, it allows for strategies involving “thousands of people, thousands of faces,” thereby boosting conversion rates through predictive incentives [20]. From a sustainability perspective, these efficiency gains underscore the strategic importance of personalization while also raising questions about the long-term social implications of intensive data use.

Although research on artificial intelligence and personalization is extensive, it remains predominantly concentrated in developed Western markets and major Asian economies, such as China [4,21,26]. This contextual imbalance highlights the critical need to examine AI adoption and its psychological impact in emerging markets such as Turkey. The literature clearly indicates that cultural differences, economic dynamics, and technological readiness in developing countries may constrain the direct applicability of findings from the U.S. and Europe. Consequently, localized empirical studies are crucial for enhancing the external validity and contextual breadth of AI marketing knowledge [4,21].

In Turkey, the e-commerce ecosystem mirrors this global surge with rapid AI adoption. Dominated by local giants Trendyol (Alibaba-backed, 138 million monthly visits, fashion-focused with proprietary brands) and Hepsiburada (pioneering books-to-multicategory platform offering secure mobile shopping), these platforms drive exports and SME growth [19,27]. Trendyol and Hepsiburada have integrated AI for competitive advantages, such as personalized logistics and recommendations, capitalizing on post-pandemic digital shifts in high-value sectors [28,29]. With companies such as Amazon entering the scene, advancements in personalization through machine learning-powered interfaces and chatbots are strengthening Turkey’s oligopolistic market, aligning with the behaviors of regional consumers [19,30]. This data-intensive AI paradigm significantly shapes consumer experiences, offering engagement benefits while also presenting challenges related to privacy risks, algorithmic bias, and trust erosion [2,10]. Accordingly, the sustainability of AI-driven personalization depends not only on efficiency gains but also on the presence of ethical governance mechanisms that protect consumer well-being in AI-mediated commerce. In the Turkish context, these dynamics underscore the need for transparent and responsible AI adoption to sustain long-term digital market growth.

2.2. Consumer Psychological Well-Being in AI-Driven E-Commerce

Consumer psychological well-being in digital contexts refers to individuals’ subjective assessments of their mental and emotional states during interactions with technology-mediated environments, such as e-commerce platforms [31]. Positive outcomes in these contexts include satisfaction, flow, autonomy, and flourishing, whereas negative outcomes include anxiety, overload, and reduced self-efficacy [11,13]. Unlike general mental health, consumer psychological well-being emphasizes technology-related aspects such as perceived competence (proficiency in digital activities), warmth (emotional satisfaction through AI interactions), and the balance between hedonic pleasure (instant gratification) and eudaimonic growth (meaningful involvement) [13,32,33]. In e-commerce, this is evident in shopping experiences that either foster happiness, fluency, and loyalty or induce stress due to intrusive personalization [5,20]. Frameworks highlight self-determination through the satisfaction of basic needs, such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness, within digital practices that can lead to harm (e.g., addiction) or benefits (e.g., empowerment) [11,34]. Accordingly, consumer psychological well-being has emerged as a critical evaluative outcome in AI-mediated consumption environments.

The theoretical foundations draw from digital well-being theories, integrating hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives within socio-technical systems. Digital well-being considers subjective well-being within media-rich environments, where activities such as scrolling or engaging with AI offer both benefits, such as convenience, and drawbacks, such as surveillance [34]. Hedonic well-being, similar to subjective well-being, emphasizes pleasure, happiness, and life satisfaction and is assessed through positive emotions and the absence of stress in digital services [35,36]. Eudaimonic well-being, on the other hand, emphasizes meaning, personal growth, relationships, and achievement, aligning with the PERMA model (positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment) [13,32,36]. Socio-Technical Systems theory conceptualizes technology as being strongly linked to human components. AI platforms contribute to human flourishing through adaptive interfaces; however, they also present risks such as “parametric reductionism,” which involves the oversimplification of choices, and “agency transference,” which entails the relinquishment of control [11,12]. The Technology and Consumer Well-Being Paradox Model illustrates this contradiction: while technology enhances eudaimonic depth through personalized discovery, it simultaneously diminishes hedonic pleasure due to overload [13]. According to Self-Determination Theory, the interaction between humans and AI is influenced by perceived interactivity, which enhances value and well-being, with privacy acting as a moderating factor [31].

Digital environments profoundly support well-being by reducing cognitive load through intuitive designs and personalized flows and enhancing engagement and satisfaction [32,37]. The quality of AI services, characterized by technical reliability, personalization, and hyperconnectivity, enhances perceived competence and warmth of the AI. This, in turn, improves well-being in the retail sector by providing seamless recommendations that affirm user agency [33,38]. In the domains of and e-commerce, digital interfaces facilitate the PERMA model by fostering positive emotions through gamified shopping experiences, enhancing engagement via immersive extended reality (XR)-like previews, and creating meaning through personalized value co-creation [36,39]. Mental models indicate that consumers perceive AI-driven personalization as a means of enhancing individual well-being, such as through efficient decision-making, and societal benefits, including inclusive access. This perception contributes to the development of trust-satisfaction-loyalty chains [5,17].

In contrast, digital environments can negatively impact well-being due to the tensions between autonomy and technology. Specifically, AI-generated recommendations may provoke reactance, thereby reducing both performance expectancy and satisfaction [38]. Algorithmic opacity and microtargeting induce surveillance fears, algorithmic bias, and over-reliance, constraining self-identity and relational dynamics [11,12]. Excessive use leads to overconsumption or multitasking, which diminishes both hedonic pleasure and eudaimonic purposes. Personalization paradoxes further exacerbate fatigue when they do not align with individual preferences [13,40]. Privacy concerns mitigate the advantages of interactivity, thereby undermining psychological well-being in data-intensive e-commerce environments [31,41]. This context reveals dualities: while services such as AI assistants enhance fluency and happiness, they also pose the risks of addiction and reduced autonomy [20,35].

This duality is critically relevant to consumer behavior and human-AI interaction in e-commerce. Well-being drives loyalty and engagement; positive psychological loyalty correlates with repeat purchases and revenue, whereas negative loyalty spurs churn [13,21]. AI personalization affects decision-making through perceived utility and trust, which mediate engagement; however, it may falter if autonomy is compromised [37,42]. In human-AI interactions, maintaining a balanced level of agency is crucial for sustaining motivation. A moderate degree of algorithmic autonomy optimizes purchasing behavior, following an inverted effect. In contrast, extreme levels of personalization, whether excessive or insufficient, tend to increase user reactance [38,42]. In the context of Turkish platforms such as Trendyol, where rapid AI adoption mirrors global trends, promoting digital well-being necessitates the implementation of ethical designs that emphasize transparency, self-efficacy, and adherence to cultural privacy norms. Such designs are essential for improving behavioral outcomes, including sustained customer loyalty, particularly in the face of tensions between personalization and privacy [10,17]. Ensuring alignment between technological capability and consumer psychology is thus central to evaluating the long-term viability of AI-driven personalization in e-commerce markets.

2.3. Consumer Privacy Concerns in Digital Environments

Consumer privacy concerns reflect individuals’ worries about the collection, storage, use, and potential misuse of their personal information during digital interactions, with particular emphasis on the lack of control over data flows [8,9]. These concerns, defined as subjective perceptions of fairness in informational privacy, emerge when technologies facilitate surveillance, unauthorized secondary use, errors, or improper access to data, resulting in feelings of vulnerability [8,43]. Privacy concerns are distinct from related concepts: while privacy risks involve objective threats such as data breaches or identity theft, concerns are attitudinal evaluations of these risks [8,26]. Privacy calculus is the mental process in which people weigh the advantages of sharing information, such as customization, against the drawbacks, such as losing control. This often helps resolve the “privacy paradox,” which is the discrepancy between expressed concerns and actual data-sharing behavior [8]. Perceived surveillance, a subset, refers to the subjective feeling of being constantly watched, which heightens discomfort in data-rich environments without specifying particular outcomes [44].

Communication Privacy Management Theory, developed by Petronio, conceptualizes privacy as a dialectical process wherein individuals co-own the boundaries surrounding shared information and negotiate disclosure rules within relational contexts, such as online platforms [8]. Theoretical frameworks have changed because of the growth of digital technology. A key issue is informational self-determination, which means having control over how data is collected and used. This is important in e-commerce, where personal information can be very different, such as browsing data compared to health data [8,45].

In AI settings, privacy concerns grow because of unclear algorithms. These are like “black boxes” that hide how decisions are made. They can also guess private details from harmless data and create very detailed profiles of people using this information [2,26]. AI recommender systems in e-commerce aggregate behavioral traces (e.g., clicks, dwell time) to predict preferences, but Opaque Machine Learning models foster distrust, as users cannot verify fairness or audit inferences such as inferred demographics [10,26]. Microtargeting intensifies this issue by facilitating manipulative nudges that heighten surveillance concerns and bias risks, thereby perpetuating disparities [2,45]. Beyond general anxieties, context-specific concerns arise: the scale of AI enables unauthorized, low-cost data exploitation, fundamentally altering the nature of privacy [46,47]. In Turkey’s booming e-commerce, platforms such as Trendyol amplify these via AI personalization, mirroring global tensions but heightened by regulatory gaps and cultural data-sharing norms [48].

These developments give rise to the Personalization–Privacy Paradox. Consumers desire personalized experiences that enhance relevance, convenience, and satisfaction, yet simultaneously resist the intrusive data collection required to deliver such benefits [8,49]. Empirical evidence indicates that, despite high levels of expressed concern (e.g., widespread discomfort with AI-based targeting), users continue to disclose personal data in exchange for perceived value, consistent with privacy calculus mechanisms [50,51]. However, when algorithmic opacity and perceived surveillance dominate, this calculus becomes unstable, leading to trust erosion and heightened psychological discomfort. In AI-driven e-commerce, increased interactivity often coincides with diminished user control, exacerbated by concerns related to biased algorithms and insufficient ethical safeguards [2,52]. These dynamics position privacy concerns as a central psychological cost of AI-driven personalization. In the Turkish context, where data protection regulations broadly resemble the GDPR and AI adoption is accelerating, achieving this balance is critical for sustaining trust, legitimacy, and long-term platform viability.

2.4. Brand Trust in AI-Enabled E-Commerce

Brand trust, encompasses broader confidence in a company’s reliability, intentions, and ability to fulfill promises across interactions, extending beyond technology to include service quality and ethical practices [5,14]. Key distinctions are evident in the scope and focus: trust in artificial intelligence emphasizes algorithmic opacity and explainability; trust in automation prioritizes functional reliability; and brand trust incorporates relational elements such as consistency and empathy, often alleviating technology-specific concerns [53].

Trust functions as a psychological mechanism that mitigates uncertainty in data-driven environments. It acts as a heuristic shortcut, thereby reducing cognitive load in situations characterized by information overload and perceived risks associated with surveillance or bias [15,54]. In e-commerce, where vast behavioral data fuel personalization, trust fosters psychological safety, enabling disclosure despite privacy fears and encouraging engagement over reactance [37,55]. Based on Social Exchange Theory, people expect a return when AI or brands provide value. This reduces uncertainty in opaque systems [5,56].

In AI-driven personalization contexts, brand trust attenuates the psychological consequences of privacy concerns through several interrelated processes. Trust reduces anticipatory anxiety by fostering expectations that the firm will act competently, benevolently, and non-opportunistically in handling personal data. Simultaneously, the same time, trust enhances perceptions of procedural fairness and legitimacy, leading consumers to interpret data collection and personalization practices as acceptable rather than threatening. Trust also provides relational assurance that increases consumers’ tolerance for uncertainty, thereby weakening the extent to which privacy concerns translate into psychological distress or diminished well-being. Trust does not eliminate privacy concerns but conditions their emotional and cognitive interpretations in AI-mediated interactions.

Trust is crucial in AI-mediated personalization settings because it fosters satisfaction, loyalty, and adoption. Empirical evidence shows that trust positively influences satisfaction and loyalty, with personalization moderating this relationship [5]. Transparent AI fosters trust by offering explainability, which addresses fears that undermine confidence [10,57]. In particular, trust acts as a moderator or boundary condition in privacy-related judgments, buffering concerns about personalization paradoxes. High trust mitigates privacy calculus trade-offs, where consumers disclose information despite risks, as reliability perceptions outweigh surveillance fears [37,57]. Privacy worries amplify when AI infers sensitive data, but brand assurances restore trust, especially among privacy-sensitive users [14]. However, this buffering role should not be interpreted as implying that trust fully resolves privacy-related concerns. Rather, trust may increase consumers’ tolerance for privacy intrusions without necessarily addressing the underlying ethical or governance challenges associated with intensive data use. Therefore, brand trust functions as a conditional psychological buffer that shapes how privacy concerns translate into psychological well-being and relational stability without eliminating underlying privacy risks or resolving broader governance challenges associated with intensive data use [37,58].

2.5. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

Building on prior research that conceptualizes AI-driven personalization as a core capability of sustainable digital commerce, perceived AI-driven personalization, which involves consumers’ subjective evaluation of customized recommendations, interfaces, and content through machine learning and predictive analytics, contributes to psychological well-being by reducing cognitive overload and increasing relevance in e-commerce [5,20]. This aligns with Self-Determination Theory, which states that customization satisfies autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs, promoting hedonic pleasure (e.g., enjoyment, flow) and eudaimonic flourishing (e.g., purpose, engagement) [11,17,42].

Although prior research recognizes that AI-driven personalization encompasses multiple attributes, these elements are often examined independently or aggregated, with limited theoretical attention to whether they operate through distinct psychological mechanisms. In particular, their differentiated implications for consumer psychological well-being remain unexplored. Addressing this gap, the present study conceptualizes perceived AI-driven personalization as comprising two analytically separable dimensions—perceived relevance and perceived specificity—that exert qualitatively different effects on consumer psychological well-being.

Perceived relevance reflects the extent to which AI-generated recommendations align with consumers’ goals, preferences, and needs. Recent research indicates that relevance-oriented personalization enhances perceived value and decision efficiency by reducing information overload and simplifying choice processes in digital environments [59,60]. In AI-driven e-commerce, such efficiency gains support effective decision-making, increase perceived competence, and foster positive affective responses, all of which are central components of consumer psychological well-being [61]. Moreover, empirical studies show that personalization perceived as relevant improves satisfaction and engagement without necessarily eliciting strong concerns about data intrusiveness, provided that the recommendation logic remains congruent with user expectations [62].

In contrast, perceived specificity captures the degree to which personalization signals deep, granular, and potentially intrusive knowledge about the individual consumer. Highly specific AI-driven personalization increases consumers’ awareness of extensive data collection and inferential profiling, thereby heightening their perceptions of surveillance and violations of personal boundaries [63]. Recent studies have further demonstrated that when personalization crosses perceived personal boundaries, consumers experience heightened discomfort, resistance, and autonomy threats, even when recommendations remain functionally accurate [64,65]. These responses undermine core psychological needs related to autonomy and control, which are essential for sustaining psychological well-being in AI-mediated consumption environments [31,66].

Although perceived specificity and consumer privacy concerns are closely related, they remain conceptually distinct. Perceived specificity reflects a perceptual cue indicating the depth and granularity of personalization, whereas consumer privacy concerns represent an evaluative psychological response characterized by anxiety, perceived loss of control, and discomfort regarding the use of personal data. Thus, specificity functions as an antecedent signal, whereas privacy concerns capture the psychological cost that may be activated in response to such signals.

Accordingly, although perceived relevance and perceived specificity both originate from AI-driven personalization, they operate through two distinct psychological pathways: a cognitive efficiency pathway, whereby relevance enhances psychological well-being by reducing effort and increasing perceived value, and a boundary regulation pathway, whereby specificity activates privacy-related autonomy threats that undermine well-being. This distinction helps explain why increasingly sophisticated AI personalization does not uniformly improve consumer well-being.

In summary, AI-driven personalization is more likely to enhance consumer psychological well-being when it is perceived as relevant rather than excessively specific. Empirical research has demonstrated that personalization enhances satisfaction and loyalty, increases engagement by 20%, and augments perceived control [5,21,67]. In smart systems, high personalization perceptions exceed intrusiveness, directly enhancing the well-being of personalization-prone users [17]. Consequently, the perception of AI-driven personalization positively influences consumer psychological well-being. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H1.

Perceived AI-driven personalization positively influences consumer psychological well-being.

The perception of AI-driven personalization is positively correlated with consumer privacy concerns, as tailored recommendations and interfaces suggest extensive data collection which evokes fears of surveillance and loss of control in e-commerce [8]. This concurrent increase in utility (personalization) and the necessity for data disclosure (risk) precisely characterizes the Personalization–Privacy Paradox (PPP) [9,64,68]. Personalization relies on AI algorithms that can be opaque, potentially leading consumers to feel that their data is being collected stealthily or ubiquitously, a phenomenon known as perceived surveillance [46]. The more accurate and tailored the personalization, the higher the possibility of consumers perceiving privacy violations by AI algorithms, making them feel watched [8,69].

Empirical evidence confirms that higher levels of personalization increase privacy concerns. As data sensitivity increases, consumers begin to perceive cues as intrusive, leading to reduced acceptance [26,70]. Research indicates that recommender systems intensify these concerns through implicit profiling, which fosters reactance and reluctance to self-disclose [9,71]. In AI contexts, opaque algorithms intensify this link, as platforms like Amazon infer preferences from big data, tempering loyalty gains with equity doubts [10]. Thus:

H2.

Perceived AI-Driven Personalization is Positively Associated with Consumer Privacy Concerns (the Personalization–Privacy Paradox).

The implementation of AI-driven personalization, while offering clear utilitarian benefits, concurrently introduces a set of psychological risks stemming from the technology’s extensive reliance on consumer data [8]. Consumer privacy concerns specifically refer to the anxiety and perceived loss of control experienced by individuals regarding the collection, analysis, and potential misuse of their personal information by e-commerce platforms [46,72].

This issue presents a direct conflict with the fundamental elements of Psychological Well-Being (PWB). PWB is contingent on the satisfaction of psychological needs, such as autonomy, competence, and a sense of control over one’s environment [66,73]. When AI systems evoke perceptions of surveillance, identity theft, or unauthorized secondary use [46], they undermine consumers’ perceived security and mastery, thereby compromising essential psychological needs that are critical for PWB [74]. The ensuing anxiety and psychological discomfort resulting from engaging in the privacy calculus, which involves balancing risks against benefits, diminishes psychological fulfillment [8,9]. Consistent with empirical evidence, heightened privacy concerns function as a significant negative boundary condition, reducing the transformation of perceived value (derived from personalization) into positive psychological outcomes [31]. Therefore:

H3.

Consumer privacy concerns negatively influence consumer psychological well-being.

AI-driven personalization significantly enhances customer utility; however, its effectiveness depends on the ongoing and intensive collection of consumer data [22]. The Personalization–Privacy Paradox posits that the pursuit of relevance necessitates data disclosure, thereby establishing a positive correlation between heightened perceived personalization and increased consumer privacy concerns [75]. This relationship is driven by consumers’ perceptions of surveillance or unauthorized secondary use, which are recognized manifestations of privacy risks in AI-based recommendation systems [8,46].

As the degree of personalization intensifies, it amplifies perceived privacy concerns, which, in turn, function as a psychological cost within the framework of Privacy Calculus Theory [76]. These privacy concerns serve as negative attitudinal constraints, posing a threat to consumers’ perceived control over their digital environment. Research indicates that privacy concerns adversely influence the relationship between perceived value derived from interaction and psychological well-being [31], thereby diminishing an individual’s sense of autonomy and fulfillment of well-being [66,73]. Consequently, the requirement for data in personalization indirectly reduces psychological well-being through privacy anxiety, suggesting a mediation effect.

H4.

Consumer privacy concerns mediate the relationship between perceived AI-driven personalization and consumer psychological well-being.

Privacy Calculus Theory posits a trade-off mechanism whereby consumers evaluate the costs, specifically privacy concerns, against the benefits, such as personalization utility, prior to engaging in data disclosure [8]. This evaluative process is notably influenced by trust, which serves as a crucial psychological buffer that mitigates perceived risk and uncertainty within digital environments [77,78].

Trust is willingness to be vulnerable to a partner’s actions despite potential risks [77]. In the context of AI-driven commerce, elevated trust in the platform or system functions as a “psychological lubricant,” enabling consumers to reduce the cognitive monitoring costs associated with privacy infringement [22,79]. When brand trust is high, consumers are more likely to perceive the exchange as fair and legitimate, even when faced with high levels of personalization that require data sharing [26].

In this evaluative process, brand trust shapes how privacy-related risks are psychologically appraised rather than merely accepted. Given that consumer privacy concerns undermine psychological well-being (PWB) by diminishing perceived autonomy and control [31,66], high levels of brand trust weaken the extent to which such concerns translate into anxiety, perceived vulnerability, and psychological discomfort. When trust in the brand is established, data collection and personalization practices are more likely to be interpreted as legitimate and aligned with consumers’ interests, thereby attenuating the negative psychological consequences of privacy concerns. Importantly, this buffering role does not imply that trust eliminates privacy risks or resolves underlying ethical tensions; rather, it conditions the emotional and cognitive impact of privacy concerns on psychological well-being.

Therefore:

H5.

Brand trust moderates the relationship between consumer privacy concerns and psychological well-being, such that the negative association is weaker at higher levels of trust.

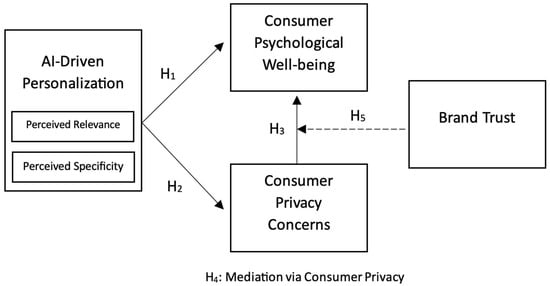

Considering the relationship between variables in the literature, the research hypotheses are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study adopted a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design to examine how AI-driven personalization in e-commerce influences consumer psychological well-being and privacy concerns in Turkey. Consistent with a quantitative, theory-testing research approach, this study employed structured measurement and hypothesis testing to examine the relationships among the proposed latent constructs.

The empirical context comprises two leading Turkish e-commerce platforms, Trendyol and Hepsiburada, which operate in an oligopolistic, data-intensive market and deploy AI for recommendation systems, customer reviews, customer support, and interface personalization. Respondents were instructed to think about one platform, depending on their initial choice as their primary online shopping site, and answer all questions with reference to that platform.

The focus on these dominant platforms reflects their central role in shaping everyday e-commerce experiences in Turkey, where a substantial share of online transactions, product discovery, and personalized interactions are concentrated on a small number of large platforms. Consequently, consumer perceptions of AI-driven personalization, privacy practices, and brand trust are likely to be formed in environments characterized by frequent platform use, extensive data collection, and well-established brand reputations. Accordingly, the selection of Trendyol and Hepsiburada follows a purposive sampling logic based on platform dominance, the intensity of AI-driven personalization, and relevance for studying consumer responses in data-intensive digital markets.

Platform selection represents a deliberate methodological boundary that anchors the study in a high-intensity personalization context rather than a neutral marketplace average. This contextual focus is essential for understanding psychological well-being outcomes in data-intensive e-commerce environments while delineating the scope within which the findings should be interpreted.

Given the study’s objective of explaining the variance in consumer psychological well-being and to examining complex relationships involving multiple latent constructs, a mediating mechanism, and a moderating (interaction) effect, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was selected as the primary analytical technique. Unlike covariance-based SEM, which emphasizes theory confirmation and overall model fit, PLS-SEM prioritizes variance explanation and the predictive relevance of endogenous constructs, making it particularly suitable for theory extension in emerging research contexts. In addition, because the measurement items were collected using Likert-type scales, strict multivariate normality could not be assumed, further supporting the use of PLS-SEM, which is robust to deviations from normality. Accordingly, PLS-SEM was deemed more appropriate than covariance-based SEM for estimating the proposed model, which combines mediation and moderation effects and focuses on prediction-oriented explanations rather than exact model reproduction.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

Data were collected from consumers in Turkey who had made at least one purchase from Trendyol or Hepsiburada in the previous six months. An online panel from a reputable local research company was used to recruit active e-commerce users from different age groups and regions. The survey was conducted between September and October 2025. After screening out ineligible respondents, 400 valid responses were retained for analysis.

Prior to the main data collection, a pilot test was conducted with 40 consumers who met the same screening criteria as the target sample. The pilot study was conducted to assess item clarity, questionnaire flow, and overall comprehensibility in the e-commerce context. The pilot test did not reveal any substantive issues; therefore, no modifications were made to the survey instrument before full-scale data collection.

At the beginning of the questionnaire, participants were asked which platform they mainly use for online shopping. Based on this choice, the platform name was piped into the subsequent items (e.g., “this platform”), and the respondents were explicitly instructed to answer all questions with that platform in mind. The questionnaire was administered in Turkish. All measurement items were translated from English to Turkish using Brislin’s [80] back-translation procedure to ensure semantic and conceptual equivalence between the original and translated versions.

Table 1 presents the sample demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the participants (N = 400).

Several procedural remedies were implemented to mitigate the common method bias. Respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, informed that there were no right or wrong answers, and instructed that responses would be used only in the aggregate form. The order of the construct blocks was randomized across the questionnaire versions, and demographic and platform-usage questions were inserted between key constructs to achieve proximal separation.

The achieved sample size exceeds the common minimum guidelines for PLS-SEM applications, which typically recommend either ten times the largest number of structural paths pointing at a construct or ten times the largest number of indicators in any construct [81,82].

3.3. Measures

All constructs were operationalized using items adapted from established scales in the literature. All items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale.

Consistent with the recent literature, Perceived AI-Driven Personalization was operationalized as a multidimensional construct comprising two subdimensions: Perceived Relevance and Perceived Specificity. Perceived Relevance captures the degree to which the platform’s AI-generated recommendations and content are aligned with the consumer’s interests and needs. Three items were adapted from Shanahan [83] and rephrased to explicitly refer to AI recommendations on e-commerce platforms. Perceived Specificity reflects the perceived depth and granularity of personalization, that is, the extent to which consumers feel that the platform tailors content based on their unique personal data and profile. Three items were adapted from Bleier and Eisenbeiss [84]. While both dimensions relate to personalization intensity, the former emphasizes goal congruence and usefulness, whereas the latter captures perceived data depth and inferential intrusiveness, allowing respondents to cognitively distinguish between functional relevance and perceived boundary penetration.

To measure the specific anxiety regarding data collection and usage in an AI environment, the scale from Xu et al. [85] was adapted to measure Consumer Privacy Concerns (CPC). This scale has 5 items. The items explicitly focus on apprehension, loss of control, and concern about personal data usage rather than evaluations of platform performance or satisfaction, thereby conceptually separating privacy-related anxiety from personalization perceptions.

Consumer Psychological Well-being (PWB) was measured using a context-specific scale with four items adapted from the Subjective Well-being with the Platform scale developed by Lee et al. [86]. The scale integrates core CPWB dimensions; including psychological satisfaction (PWB2–3), positive affect (PWB4), and life congruence (PWB1), while being explicitly designed for online shopping platforms. The items capture respondents’ internal psychological states rather than transactional satisfaction or service quality assessments. Respondents were thus prompted to reflect on how interacting with the platform affected their psychological state, not on how well the platform performed. The scale was recently developed and validated to specifically measure well-being outcomes in the online shopping platform context, thereby ensuring high contextual validity for this study.

To measure the moderating role of Brand Trust (BT), the short-form version of the Trusting Beliefs scale by McKnight et al. [87] was adopted. This four-item scale reflects overall confidence in the platform’s benevolence and integrity.

All measurement items and their sources are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Constructs measurement items.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

This study complied with institutional and national ethical guidelines for research involving human participants, including the Turkish Personal Data Protection Law. Prior to data collection, the research proposal was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Protocol ID: 2025/15–04) of Maltepe University. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without any negative consequences. Informed consent was obtained electronically before the questionnaire was administered. No identifying information was collected, and the responses were analyzed in aggregate form only.

4. Results

The hypotheses were tested using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS 4 [88]. Analyses followed the two-step procedure recommended in the PLS-SEM literature: evaluation of the measurement model, followed by an assessment of the structural model [89].

All the constructs were modeled as first-order reflective constructs. Indicator reliability was assessed using outer loadings, with values above 0.70 considered satisfactory. Internal consistency reliability was evaluated using composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha, and convergent validity was examined through the average variance extracted (AVE), seeking values above 0.50. Discriminant validity was assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT), with confidence intervals obtained through bootstrapping.

To test the structural relationships, a nonparametric bootstrapping procedure with 5000 bootstrap subsamples and bias-corrected confidence intervals was applied to the data. Aside from the direct effects, mediation and moderation were also tested using modern procedures for indirect effects in PLS-SEM [89].

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

All constructs were specified as first-order reflections. The measurement model was evaluated in terms of indicator reliability, internal consistency, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity criteria [89].

Standardized outer loadings were examined using composite scores for each construct. As shown in Table 3, all items loaded strongly on their intended constructs, with loadings above the threshold of 0.70, indicating satisfactory reliability. Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) were used to assess the internal consistency. For all constructs, Cronbach’s α values were clearly above the recommended minimum of 0.70, supporting internal consistency and reliability.

Table 3.

Measurement model results.

Convergent validity was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE). As shown in Table 3, the AVE values for all constructs were above 0.50, indicating that each construct explained more than half of the variance of its indicators, on average. This supports the convergent validity [89].

Discriminant validity was evaluated based on Fornell–Larcker criteria and heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT). Following the methodology outlined by Hair [89], the analysis of cross-loadings indicated that each item achieved its highest factor loading on the respective construct. Moreover, in accordance with the criterion proposed by Fornell and Larcker [90], the square root of the mean AVE value for each construct was greater than its correlation with other constructs as shown in Table 4. Finally, consistent with the recommendations of Henseler et al. [91] and Ringle et al. [88], the HTMT analysis revealed that all values were below 0.85, thereby supporting discriminant validity. The HTMT values are presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 5.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) matrix.

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

After confirming the adequacy of the measurement model, the structural model was evaluated. Prior to hypothesis testing, multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF). All VIF values were below 3.3, indicating that multicollinearity and common-method bias were not a concern [89,92]. The results of the direct effects are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Structural model results.

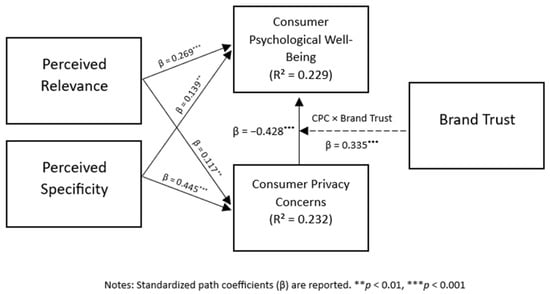

The results show that AI-driven personalization positively influences consumer psychological well-being. Specifically, Perceived Relevance (β = 0.269; p < 0.001; f2 = 0.09) and Perceived Specificity (β = 0.139; p < 0.01; f2 = 0.02) both significantly predicted Consumer Psychological Well-Being (R2 = 0.229). A comparison of effect sizes indicates that perceived relevance exerts a substantively stronger influence on psychological well-being than perceived specificity, suggesting that alignment with consumers’ goals and situational needs contributes more to well-being than granular personalization. These findings indicate that a higher perceived relevance and specificity of AI-driven recommendations enhance consumers’ sense of well-being, thereby supporting H1.

Consumer privacy concerns have a strong negative influence on psychological well-being. The path from CPC to PWB was substantial and significant (β = −0.428; p < 0.001; f2 = 0.17), confirming that elevated privacy concerns diminish consumers’ psychological well-being. The effect size indicates that privacy-related psychological costs are a central determinant of well-being in AI-driven e-commerce environments. Given the strength and significance of this relationship, H2 was supported.

The results show that both dimensions of AI-driven personalization significantly increase consumer privacy concerns. Perceived Relevance exhibited a positive effect (β = 0.117; p < 0.01; f2 = 0.02), whereas Perceived Specificity had a substantially stronger effect (β = 0.445; p < 0.001; f2 = 0.25). The model accounted for 23.2% of the variance in CPC (R2 = 0.232). These findings demonstrate that personalization perceived as highly specific is considerably more likely to trigger privacy concerns than personalization perceived as merely relevant, highlighting an asymmetry in the psychological costs associated with different forms of AI-driven personalization. Together, these results support H3.

4.2.1. Mediation via Consumer Privacy Concerns

The mediation analysis examined whether consumer privacy concerns transmitted the effects of AI-driven personalization on psychological well-being. Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples revealed that both personalization dimensions exerted significant negative indirect effects on psychological well-being through consumer privacy concerns. Specifically, Perceived Relevance demonstrated a significant indirect effect (β = −0.049, 95% CI [−0.088, −0.012]), indicating that higher relevance increases Consumer Privacy Concerns, which subsequently diminishes Consumer Psychological Well-Being. Likewise, Perceived Specificity showed a stronger negative indirect effect (β = −0.190, 95% CI [−0.256, −0.134]), suggesting that more precise and individualized recommendations amplify CPC and reduce PWB (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Bootstrapped indirect effects.

The relative magnitude of these indirect effects indicates that specificity-driven personalization incurs a substantially greater psychological cost through privacy concerns than relevance-driven personalization. The results provide clear evidence of competitive partial mediation, whereby personalization directly enhances well-being but simultaneously decreases it indirectly through increased privacy concerns. This pattern illustrates that AI-driven personalization generates simultaneous benefits and costs, with the balance between them depending on the specific form of personalization experienced by the consumer. Therefore, H4 is supported by the data.

4.2.2. Moderation of Brand Trust

Moderation analysis was used to examine whether Brand Trust buffers the negative effect of Consumer Privacy Concerns on Consumer Psychological Well-Being. The interaction term between CPC and BT was positive and statistically significant (β = 0.335, p < 0.001; f2 = 0.07), indicating that BT weakens the detrimental impact of CPC on PWB.

To clarify the substantive meaning of this interaction, the results indicate that when brand trust is low, privacy concerns translate more directly into anxiety, perceived loss of control, and reduced psychological well-being. In contrast, at higher levels of brand trust, the negative association between privacy concerns and well-being is substantially attenuated, suggesting that trust buffers but does not eliminate the psychological impact of privacy-related risks. In other words, when consumers exhibit higher levels of trust in an e-commerce platform, privacy concerns exert a less negative influence on their psychological well-being. Conversely, at low levels of brand trust, privacy concerns had a noticeably stronger negative effect. These findings confirm the hypothesized moderating role of brand trust, thereby supporting H5.

Figure 2 presents the final PLS-SEM structural model estimated using SmartPLS, with standardized coefficients and significance levels.

Figure 2.

Final PLS-SEM structural model with standardized path coefficients.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion of Hypotheses Results

This study explored how AI-driven personalization, privacy concerns, and brand trust jointly shape consumer psychological well-being within the Turkish e-commerce ecosystem. Beyond confirming the proposed hypotheses, the findings highlight that different forms of AI-driven personalization generate asymmetric psychological outcomes for consumers. Rather than operating as isolated effects, the findings reveal a multilayered psychological process in which AI-enabled personalization generates both value and vulnerability, with brand trust determining whether these effects translate into enduring and positive consumer outcomes.

The support for H1 confirms that perceived relevance and perceived specificity significantly enhance psychological well-being. These findings align with prior literature emphasizing that personalization improves decision quality, reduces cognitive burden, and fosters positive affective states [5,20]. Consistent with Self-Determination Theory [11,17,42], consumers experience greater autonomy and competence when AI-generated recommendations match their preferences. Simultaneously, the results suggest that relevance-driven personalization contributes more strongly to psychological well-being than specificity-driven personalization, indicating that goal alignment and situational fit are particularly important for positive consumer experiences. These results indicate that well-designed AI personalization can strengthen consumers’ sense of agency and psychological comfort in digital marketplaces. This effect emerges clearly within the empirical context examined, where high platform dependence and frequent mobile commerce create efficient conditions for AI to improve user fluency and satisfaction.

The confirmation of H2 shows that both personalization dimensions heighten privacy concerns, with perceived specificity exerting a stronger influence. This distinction reveals that consumers infer intrusive data practices when they see highly tailored, granular recommendations. This pattern suggests that personalization perceived as highly specific is more likely to activate privacy-related concerns than personalization perceived as merely relevant. This result supports the theoretical expectations surrounding algorithmic opacity and profiling [8,10,26,46]. While relevance may indicate usefulness, specificity signals the depth of data inference, triggering fears of surveillance and potential misuse.

In contrast, the strong negative effect identified for H3 reinforces that privacy concerns substantially diminish psychological well-being. Consistent with previous studies on perceived surveillance and data vulnerability [31,46,66,72], this result underscores privacy-related anxiety as a significant psychological cost of AI-mediated commerce. When consumers perceive a loss of informational self-determination, the psychological benefits of personalization are eroded, reducing emotional comfort and perceived control over consumption experience.

H4 provides compelling evidence of the Personalization–Privacy Paradox through competitive partial mediation. While personalization directly enhances well-being, the privacy concerns it generates simultaneously undermine well-being. The mediation results indicate that the indirect psychological costs associated with specificity-driven personalization are more pronounced than those associated with relevance-driven personalization, partially offsetting its direct benefits to the user. This dual pathway extends Privacy Calculus Theory [76], demonstrating that personalization imposes a psychological cost beyond behavioral trade-offs. The Turkish digital context, characterized by rapid AI adoption, uneven digital literacy, and evolving regulation, likely amplifies this paradox.

Finally, the confirmation of H5 demonstrates that brand trust significantly mitigates the harmful impact of privacy concerns on consumer psychological well-being. Trust acts as a psychological buffer [31,77,79], allowing consumers to tolerate perceived risks while maintaining a sense of competence and emotional stability. The moderation effect indicates that privacy concerns translate less strongly into reduced well-being when brand trust is high, whereas under low-trust conditions, the same concerns have a more detrimental psychological impact. Additional research on AI-supported collaboration similarly shows that trust reduces uncertainty, strengthens cooperative intentions, and enhances positive user responses even in data-intensive environments, underscoring its essential role in shaping how users evaluate AI-driven systems [93]. In AI-driven e-commerce, brand trust therefore stabilizes consumer evaluations when transparency or direct control over data use is limited. This effect is highly relevant for Turkish platforms, where brand reputation and perceived integrity continue to shape digital consumption norms.

Taken together, the findings indicate that AI-driven personalization enhances consumer psychological well-being in a conditional manner, depending on the balance between personalization benefits, privacy-related costs, and the presence of brand trust. Within the empirical scope of this study, which focuses on consumers’ perceptions in an AI-enabled e-commerce context, the results suggest that trust can attenuate but not eliminate the psychological strain associated with data-driven personalization. When trust is absent, privacy concerns dominate, offsetting the benefits personalization is designed to deliver and potentially undermining positive consumer experiences in data-intensive digital environments. Although the present findings do not allow for direct normative claims regarding responsible AI design, they offer empirically grounded insights that are relevant to broader discussions on consumer well-being and sustainability in AI-enabled commerce, while acknowledging that wider ethical and governance implications remain an important avenue for future research.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study advances theory by integrating personalization, privacy, and trust into a unified framework that explains consumer psychological well-being in AI-mediated e-commerce. Beyond integrative synthesis, this study contributes to theory by explicating the distinct psychological mechanisms through which different attributes of AI-driven personalization and governance-related factors shape consumer well-being. By positioning psychological well-being as a central theoretical outcome rather than a peripheral consequence, this study extends dominant AI marketing frameworks beyond efficiency- and behavior-oriented explanations and repositions well-being as a key indicator of social sustainability in digital commerce ecosystems.

First, it confirms that AI-driven personalization enhances well-being, enriching Self-Determination Theory within digital contexts [11,17]. By demonstrating that autonomy-supportive personalization can generate psychological benefits, the findings contribute to sustainability-oriented perspectives that emphasize human-centered and responsible AI design. Evidence from an emerging market extends the external validity of personalization–well-being relationships beyond predominantly Western-centric empirical settings without presuming distinct cultural mechanisms.

Second, by showing that privacy concerns strongly and negatively affect psychological well-being, this study deepens the theoretical understanding of the psychological costs associated with data-intensive environments [46,78]. Privacy concerns are conceptualized not merely as behavioral inhibitors of disclosure or adoption but as direct threats to emotional security, perceived control, and cognitive balance. This reconceptualization positions privacy concerns as a direct pathway through which inadequately governed AI-driven systems may erode well-being and social sustainability.

Third, a central theoretical contribution of this study lies in distinguishing between perceived relevance and perceived specificity as two analytically separable dimensions of AI-driven personalization that activate fundamentally different psychological mechanisms. While relevance-based personalization enhances psychological well-being primarily through cognitive efficiency and value facilitation, specificity-based personalization operates through a boundary-regulation mechanism that heightens perceptions of surveillance, vulnerability, and loss of autonomy. By demonstrating that these dimensions exert qualitatively different effects on well-being and privacy perceptions, this study moves personalization theory beyond aggregate or intensity-based treatments and offers a dual-pathway perspective that explains why increasingly accurate AI personalization does not uniformly improve consumer outcomes.

Fourth, the identification of a competitive partial mediation effect extends Privacy Calculus Theory [76] by demonstrating that AI-driven personalization simultaneously generates psychological benefits and costs that directly shape consumer well-being. Rather than framing personalization–privacy trade-offs solely as antecedents of behavioral intentions, the findings reveal their concurrent influence on internal psychological states, thereby shifting the privacy calculus toward a more welfare-oriented and sustainability-relevant theoretical lens. This insight moves the privacy calculus beyond behavioral trade-offs toward a more holistic understanding of psychological welfare in human–AI interactions, thereby aligning the privacy calculus with sustainability-oriented evaluations of long-term consumer welfare and offering a richer account of the Personalization–Privacy Paradox.

Finally, the moderating role of brand trust highlights its conditional function as a relational buffer in AI-enabled consumption. Rather than operating as a formal governance mechanism, brand trust mitigates the negative impact of privacy concerns by reducing uncertainty and perceived vulnerability when transparency or user control is limited. In this sense, trust operates as an informal governance mechanism that complements formal regulatory frameworks, stabilizing psychological well-being under conditions of algorithmic opacity and intensive data use. However, this buffering role should not be interpreted as implying that trust fully resolves privacy-related tensions. Rather, brand trust conditions the psychological consequences of privacy concerns by shaping how consumers interpret and emotionally respond to data-related risks and may increase their tolerance of privacy intrusions without necessarily addressing the underlying ethical or governance challenges. By preserving psychological well-being and reducing perceived harm within the empirical scope of this study, trust reinforces its foundational role in sustaining positive consumer–AI relationships, while broader ethical and institutional challenges associated with AI governance remain beyond the explanatory scope of the present model.

5.3. Managerial Implications

The results emphasize the need for e-commerce platforms to balance personalization benefits with responsible data practices. Importantly, the findings indicate that not all forms of AI-driven personalization generate equivalent psychological outcomes. Although personalization enhances psychological well-being, its deeper forms, especially high specificity, can unintentionally increase privacy concerns. Managers should therefore distinguish between relevance-oriented personalization, which enhances perceived value and decision fluency, and specificity-oriented personalization, which may be interpreted as intrusive if not carefully governed. Managers should also communicate data practices transparently and ensure that recommendation systems feel supportive, not intrusive.

Given the strong negative effect of privacy concerns on psychological well-being, platforms should invest in clear and easily understandable consent mechanisms, robust data security infrastructures, and transparent explanations of how consumer data are collected and used. Privacy protection should be viewed not only as a regulatory obligation, but also as a core component of consumer well-being and socially sustainable platform design. Reducing perceptions of surveillance and loss of control is critical for maintaining consumer comfort and emotional stability in AI-mediated shopping environments.

Brand trust emerged as a critical buffer against privacy-related psychological harm. To strengthen trust, platforms should continually demonstrate honesty, integrity, and consumer-centric values, aligning their operations and communication strategies with benevolence and reliability [14]. By signaling ethical data stewardship and responsible AI use, trusted platforms can reduce perceived vulnerability even when personalization relies on complex or opaque algorithms. Clear communication about the benefits of AI-driven personalization can help consumers form more favorable privacy judgments [8]. Offering meaningful user control over personalization depth may enhance feelings of autonomy and reduce reactance.

Finally, because privacy norms, regulatory expectations, and technological perceptions vary across markets, Turkish platforms such as Trendyol and Hepsiburada should adopt context-sensitive trust-building and transparency practices rather than uniform personalization strategies. Personalization strategies that prioritize psychological well-being and minimize privacy-related anxiety are more likely to support durable platform relationships and the long-term viability of data-intensive business models. Culturally grounded transparency practices, adaptive consent designs, and ethically informed personalization strategies are essential for sustaining consumer trust, psychological well-being, and long-term platform resilience in contemporary AI-enabled commerce environments.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study offers meaningful theoretical and empirical insights into the consequences of AI-driven personalization in e-commerce, several limitations present opportunities for further research. First, the cross-sectional survey design restricts the causal inference. Although the proposed structural relationships are theoretically grounded and statistically robust, the findings should be interpreted as associational rather than strictly causal. In particular, simultaneity bias and reverse causality cannot be fully ruled out; for example, consumers’ psychological well-being may influence their perceptions of brand trust or privacy concerns rather than solely resulting from them. Longitudinal or experimental studies would allow researchers to observe how personalization experiences, privacy concerns, trust, and psychological well-being evolve over time, particularly as platforms adjust their AI capabilities or transparency practices, and would provide stronger evidence regarding temporal ordering and causal mechanisms.

Second, the study is contextually bound to Turkey, a rapidly digitalizing emerging market characterized by unique cultural norms, evolving regulatory conditions, and varying levels of digital literacy. Although this context extends AI personalization research beyond Western markets, it may limit generalizability to countries with different privacy expectations, technological infrastructures, or trust dynamics. Future cross-cultural or multi-country studies could assess whether the dual pathways identified in this research manifest similarly across diverse institutional and cultural settings.

Third, the study relies on self-reported measures, which may be influenced by perceptual bias, social desirability, or limited introspective accuracy regarding psychological well-being and privacy concerns. Despite implementing procedural remedies to mitigate common method bias, reliance on a single survey instrument to measure psychologically salient constructs may still inflate observed relationships. Subsequent research could incorporate behavioral metrics, such as clickstream data, dwell time, or personalization opt-out behaviors, to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of how users respond to AI-driven personalization. Incorporating physiological or affective measures may further deepen understanding of the emotional processes underlying personalization–privacy trade-offs.

Finally, although the moderating effect of trust in brand was examined, other boundary conditions remain unexplored. Individual differences such as digital literacy, privacy sensitivity, algorithmic awareness, or varying levels of experience with personalized platforms may shape how consumers interpret personalization signals. Moreover, future studies may investigate how different types of AI personalization (predictive, generative, contextual, or behavioral) differentially influence privacy concerns and well-being. Experimental designs manipulating personalization intensity or transparency cues, as well as longitudinal approaches capturing dynamic feedback effects, would be particularly valuable for extending the present model and strengthening causal inference. Examining platform design features, transparency cues, and user control mechanisms may further clarify how organizations can reduce privacy-related psychological costs while preserving the benefits of personalization.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that AI-driven personalization exerts both beneficial and adverse psychological effects on consumers in data-intensive e-commerce environments. While perceived relevance and specificity enhance psychological well-being by improving the quality and efficiency of digital interactions, these same personalization mechanisms also increase privacy concerns, which substantially harm well-being. The competitive mediation effect underscores the inherent tension at the core of the Personalization–Privacy Paradox.

Importantly, brand trust emerges as a critical buffer that mitigates the psychological burden of privacy concerns, preserving consumer well-being in AI-mediated contexts. Within the empirical scope of this study, these findings indicate robust associations between personalization, privacy concerns, trust, and psychological well-being rather than definitive causal relationships. By framing psychological well-being as a social sustainability outcome of AI deployment, the findings highlight that efficiency-oriented personalization strategies are more likely to be sustainable when accompanied by responsible data governance and trust-based mechanisms.

Together, these insights emphasize that the sustainability of AI-driven e-commerce depends not only on technological sophistication or operational efficiency, but also on the ability of firms to protect consumer autonomy, emotional security, and perceived control. However, reliance on a cross-sectional design and self-reported measures suggests that these conclusions should be interpreted with caution. Transparent AI design, ethically grounded data practices, and sustained trust-building efforts emerge as important considerations suggested by the findings, rather than prescriptive solutions, for aligning AI-driven personalization with responsible innovation and long-term business sustainability, particularly in rapidly evolving and data-intensive digital markets.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Maltepe University (7 August 2025–protocol code 2025/15-04).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to Turkish national law of privacy protection.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| CR | Composite reliability (CR) |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations |

| PLS-SEM | Partial least squares structural equation modeling |

| PERMA | Positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment |

| PWB | Psychological well-being |

| SME | Small and medium enterprises |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

References

- Chornous, G.; Dimitrov, R.; Fareniuk, Y.; Penkova, M.; Nosko, R. Integration of feeling AI tools to support marketing solutions in e-commerce. Access J. Access Sci. Bus. Innov. Digit. Econ. 2025, 6, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]