Abstract

Light pollution entails unnecessary energy use, higher emissions and greater pressure on natural resources, as well as disrupting wildlife and human health. Specific policies and model ordinances are available for local governments to implement to address light pollution. This study analysed the light pollution policies of Australian local governments, in terms of specific details and whether the pattern of results reflects more of a polycentric or multi-level approach. Thirty local governments representing all of the urban areas in Australia with a population over 100,000 had their public lighting policy documents analysed. Very few local governments had taken steps toward addressing light pollution. The wide array of local governments did lead to some experimentation with light pollution policy, which provides test cases for others to consider. To obtain widespread coverage a multi-level approach may be needed, requiring higher levels of government to have light pollution policies in future. For now, very few local governments in Australia have any light pollution policies and of those, even fewer are comprehensive.

1. Introduction

Inefficient or excessive illumination, commonly known as light pollution, entails unnecessary energy use, higher emissions, and greater pressure on natural resources [1]. The growth of light pollution is increasingly a significant environmental concern, with artificial lighting’s detrimental effects now impacting the majority of the world’s population [2,3,4].

The global effects of artificial lighting include but are not limited to environmental impacts, wildlife disruption and human health concerns [5]. Artificial light disrupts the stability of natural light-dark cycles that regulate the behaviour and biological processes of living organisms, influencing a wide range of physiological and psychological functions [6,7,8]. Artificial light at night (ALAN) and misdirected lighting is particularly damaging to natural ecosystems, altering biological rhythms, reproduction, and ecosystem balances [9]. Artificial lighting is also increasingly interfering with human health, influencing circadian functions, changes in physiological rhythms, and altering perceptions of safety [10,11].

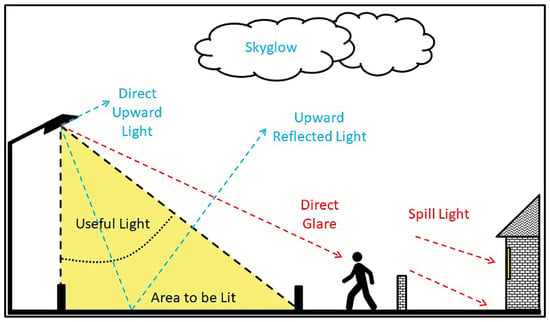

Light pollution from artificial light is commonly divided into four categorisations which often overlap depending on the context of the light source, namely: glare, light trespass, over lighting and skyglow [7]. Glare is visual discomfort or reduced visibility caused by excessive brightness or an improper distribution of light within a person’s field of view [12]. Light trespass, sometimes referred to as light spill, is artificial light that extends beyond the area it is intended to illuminate, often shining onto neighbouring properties or into the night sky causing annoyance, discomfort, or distraction [13]. Over lighting, also referred to as over illumination, occurs when artificial lighting exceeds the lighting levels strictly required for a given task or context [14]. The cumulative effect of these forms of light pollution often results in upwards light contributing to skyglow, defined as brightening of the night sky caused by artificial light scattered in the atmosphere [15,16,17]. These components of light pollution are presented in Figure 1, where the upward components are shown in blue, and downward components are shown in red. The growing impacts of artificial lighting have disrupted natural nighttime conditions and continue to influence ecosystems and environments across the world.

Figure 1.

The components of light pollution (Source: [18]).

To address light pollution a range of solutions have been tested and implemented around the world. Some of the solutions include lighting curfews [19], shielding [20], improved luminaire design [21] and the introduction of smart lighting systems [22]. Lighting curfews are a common regulatory method to reduce light pollution by mandating the dimming or extinguishing of non-essential lights after certain hours [9,23]. Shielding is also an effective method, blocking unwanted light from boundaries [24]. Replacing traditional sodium-based luminaires to light emitting diodes (LEDs) can significantly reduce energy consumption [21,25], particularly when combined with smart lighting systems that regulate the brightness, colour and timing of light fixtures [22]. When combined, these and other practices and policies can result in reductions in light pollution so substantial that the night sky can be conducive to astronomical observations, a status known as a dark sky. Internationally, several communities have been recognised by DarkSky International as global examples demonstrating the potential of coordinated frameworks to reduce light pollution while maintaining functional outdoor lighting [23,26]. These frameworks have been translated by Darksky International, with the Illuminating Engineering Society, in to model ordinances ([27]).

That is, the changes required to reduce light pollution are somewhat known. Specific practices and policies, along with model ordinances, are available for implementation by appropriate bodies. Local governments are the lowest tier of government in Australia (often referred to as ‘councils’) and are responsible for local services, including the regulation of most sources of public lighting, such as streetlights. Yet, despite the urgent need to examine legislative and practical measures that can effectively mitigate the harmful consequences of light pollution [23,28], sustainability efforts by local governments have tended to be haphazard [29]. For example, some local governments in the USA have tried to manage light pollution, although the substantial majority have not [30].

The large number of local governments should present fertile grounds for experimentation with and development of lighting policy. Where some councils that have made progress with their policies, the policies they have introduced may be able to inform the efforts of others. Consequently, the aim of this study is to investigate and assess the current status of Australian councils’ light pollution policies.

Is Policy Action Polycentric or Multilevel for Local Governments?

Managing light pollution represents one of the simplest and most cost-effective steps local governments can take toward sustainability [31], helping to reduce energy consumption, lower emissions, and improve environmental quality [32,33]. Local governments often have high levels of autonomy and, with their much larger numbers relative to other levels of government, present a context that is likely to have experimented with a variety of mechanisms for addressing the common problems they face [34]. Municipalities with sufficient capacity, technical expertise and/or leaders actively developing environmental policy could adopt sustainability policies on their own, providing an example to other municipalities [35], yet few local governments have implemented sustainability policies. The sophistication of municipal light pollution policies appears to be driven primarily by technological assessment capabilities and local experimentation. However, there’s a notable gap between scientific advances and their transfer to political decision-making [28], suggesting that local technological assessment capabilities are uncommon. Two key theories that have been used to try to explain how policy action regarding sustainability emerges are polycentricism, a governance model with multiple independent decision-making centers, and multi-level theory, emphasizing collaborative governance across geographic and institutional levels [36]. The section below will briefly outline polycentrism and then multilevel approaches to explaining the adoption of sustainability policies such as light pollution in local (and other levels of) government.

Polycentric theory grew out of seminal research on police services and water resource management [37] that demonstrated that polycentric systems, with multiple independent decision-making centers, could be more effective than hierarchical governance models [38]. The theory emerged from public choice perspectives, arguing that decentralized authorities could generate more innovative and responsive governance structures based on their better understanding of local needs [37] and the ability of local governments to act independently [39] to provide a diversity of choice [40].

Such local experimentation has led to pioneering rural areas in France developing mechanisms that integrate biodiversity preservation and energy transition goals [26]. The end result is often that there is considerable variation in definitions, control strategies, and regulatory frameworks, although that variety is such that most cities do not address light pollution in their municipal codes (e.g., in the USA [30]).

In contrast to polycentrism, multilevel theory as applied to local governments emphasizes the need for collaborative governance across geographic spheres, with cross-level and cross-agency interactions, and has been applied to efforts to adapt to climate change, such as in Mexico City [41]. The result is that local governments operate through networks involving horizontal collaboration with neighboring entities and vertical interactions with higher-level governmental authorities [42].

National and cross-national authorities have sometimes begun efforts to address light pollution, but with varying degrees of success. The European Union has regulations and plans that nibble around the edges of light pollution policy, but do not regulate ALAN [28]. Countries are starting to develop national minimum approaches, but they may need further refinement. For example, in Germany the federal laws have been deemed to be inadequate because they rely on legal assessments that are hard to apply with ALAN [43]. However, countries such as Spain have several laws directly addressing light pollution that set the basic requirement upon which regional authorities can build additional rules [28]. These national frameworks are an important beginning, not least because there are some cases where national rules may be necessary to achieve a desired result (e.g., to provide large scale wildlife corridors across regions [43]), but, particularly for ALAN and light pollution, are still at the early stages of development.

Furthermore, the extent to which a multi-level framework applies may vary by the degree of autonomy held by the local government. Some local governments may be direct agents of state governments, whereas in other contexts local governments may set their own rules, as long as they exceed minimum standards, reflecting the interplay between levels of technical knowledge and local knowledge of society [36]. Australian local governments may be somewhere in the middle of the spectrum of autonomy held by local governments, because they have to deal with levels of oversight of their activities in many areas, especially by their state governments, to the extent that calling them autonomous could be misleading [44].

Other than nation- or state-based regulations there are also technical authorities that may be considered in the development of light pollution policy. For example, in Australia there is an independent, non-governmental advisory body, known as Standards Australia, that has developed some guidelines relevant to light pollution. The standards that they release are not legally binding in themselves, but are legally binding if a state or federal law requires conforming to a particular standard [45].

A further key characteristic that may modify or explain whether local governments develop lighting and light pollution policies is the size of the population in the municipality. In Australia, towns with populations over 100,000 house nearly 80% of the population and generate over 80% of the economic wealth, which means that these larger towns are critical policy laboratories for addressing climate change [46]. The Australian situation is in sharp contrast to the USA where only approximately 30% of the population are in towns with a population over 100,000 [36]. Consequently, the Australian situation presents a relatively under-explored context for investigating light pollution policy, relative to the more distributed population centres of other developed economies such as the USA and Europe.

The aim of this study is to assess the current status of lighting and light pollution policy in local governments and associated entities across Australia. The lighting policies will be assessed in terms of their breadth across the four components of light pollution (glare, light trespass, over lighting and skyglow [7]) and in terms of the eight DarkSky criteria (detailed in the method below). The pattern of results arising from assessing the lighting policies will then be considered in terms of polycentrism or multilevel drivers to generate considerations for the future development of light pollution policy.

2. Materials and Methods

The study assesses the effectiveness of light pollution management by Australian local councils through comparison with international best-practice communities. A qualitative, exploratory approach using framework analysis was adopted, allowing for systematic interpretation of large, complex policy datasets and identification of emerging themes within applied policy research [47,48].

Primary data were collected from publicly available lighting and light pollution policies published on official Australian council websites. Thirty councils were purposively selected to represent a wide demographic and spatial distribution across the nation, encompassing both large metropolitan and regional populations. All of the councils for medium-sized cities were analysed. For large cities covering multiple councils, three councils were randomly selected per location. Council selection was guided by the Australian Government Centre for Population [49] interactive dashboard to identify those councils with larger populations. The final sample comprised eight councils from New South Wales, six from Victoria, six from Queensland, three from South Australia, two from Western Australia, two from Tasmania, two from the Northern Territory, and one from the Australian Capital Territory.

Most large Australian cities are close to significant parklands, which reflects how over 22.57 percent of Australia’s land area is within the national reserve system, a network of protected land including national parks and conservation areas [50]. Australia’s heavily urbanized population are in cities that are often bordered by significant parklands (e.g., the Royal National Park near Sydney, the Dandenongs near Melbourne). None of the towns or cities in Australia with a population over 20,000 are DarkSky certified by DarkSky International as at December 2025. These parklands and conservation areas could potentially benefit from light pollution controls.

Targeted keyword searches, such as “light pollution policy”, “lighting policy”, “street lighting policy”, and “nuisance lighting”, were used to identify relevant documents. Each policy was categorised according to the lighting context (street, public, or private). Once categorised, data was entered into the comparative framework and then studied for key terms and themes.

To provide a benchmark for best practice, data were also collected from the DarkSky International database [51]. Certified DarkSky Communities were filtered by population size, selecting communities with populations above 14,000 to have more comparability with the chosen Australian councils.

The collected documents were examined using the five-step framework analysis process: familiarisation, thematic framework development, indexing, charting, and interpretation [47]. Themes were derived from established light pollution literature and included glare, light trespass, over-lighting, and skyglow, as well as broader considerations such as human health, wildlife impacts, cost efficiency, and emissions reduction. During analysis, two additional themes emerged, council reliance on Australian Standards (AS/NZS 4282:2023 [52] and AS/NZS 1158 series [53]) and the influence of electricity providers on local policy control, which were subsequently integrated into the framework. The comparative framework enabled systematic evaluation of Australian council policies relative to international best practice, highlighting policy gaps and opportunities for improvement.

All data were sourced from publicly accessible websites. No human or animal participants were involved; therefore, ethics approval was not required. All analysed policy documents and DarkSky community materials remain publicly available and can be accessed directly via the respective council and DarkSky websites.

3. Results

Overall, the vast majority of the councils of large population centres in Australia had little in the way of light pollution policy. Half of the councils that were assessed did not have any policies that addressed any of the key characteristics of light pollution. The sections below provide the lighting policy context for the councils and then the details of the results.

The results of the study are grouped in terms of: ownership and operation of lighting, the extent to which policies addressed each of the four components of light pollution (glare, light trespass, over lighting and skyglow), and how many of the eight DarkSky controls were addressed. Those analyses are followed by checks of the matching between Australian Standards and energy providers in terms of the DarkSky requirements.

3.1. Relationship Between Australian Councils and Energy Providers

The relationship between energy providers or distributors and the Australian councils in the analysed sample was examined. Table 1 identifies four major types of relationships concerning lighting policy. The relationships are lighting owned, maintained, and operated entirely by the council; ownership by the council with maintenance or operation by the energy provider; partial ownership by the council with the energy provider, with maintenance and operation shared; and lighting owned, operated, and maintained solely by the energy provider. Regardless of ownership, all lighting costs were paid by either the local councils or the state government.

Table 1.

Ownership of lighting, Australian councils.

The results showed that only 6.7% of councils analysed—both located in the Northern Territory—completely owned, operated, and maintained their lighting. Councils that owned lighting but relied on energy providers for maintenance and operation comprised 40% of the sample, with all councils from Queensland having such operational and maintenance arrangements with their energy providers.

Full ownership of lighting by councils was not necessarily linked to the presence or absence of an existing lighting policy. For example, the City of Darwin (NT), the City of Launceston (TAS), and the City of Hobart (TAS) all maintain ownership of their lighting as assets, but no formal light pollution policy was found on their websites.

There appears to be an association between outsourcing the ownership, operation, and maintenance of lighting infrastructure to energy providers and having only one or no lighting policy in place. In Western Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia councils often have their lighting fully owned, operated, and maintained by energy providers. Considering the ownership of lighting in Australia, an investigation into the ownership of the energy providers themselves was conducted, seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ownership of energy providers between state and private actors.

Notably, all of the energy providers for Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales were privately owned. The results indicate a potential constraint on light pollution policy implementation due to the implications of the different ownership structures.

3.2. Australian Council Policies by Component of Light Pollution Addressed

Controls addressing components of light pollution (glare, light trespass, over lighting, and skyglow) were analysed across the Australian local councils. The results for Australian councils are compared with those of DarkSky-certified communities (communities certified by DarkSky International for responsible outdoor lighting), and potential areas for evidence-based practice are identified (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Light pollution components considered in the policies of Australian councils and selected DarkSky International (DS) certified communities.

Three of the assessed Australian councils, the Sunshine Coast Regional Council (QLD), the City of Sydney (NSW), and the Blacktown City Council (NSW), had lighting policy provisions that addressed all four key components of light pollution. The Brisbane City Council (QLD) was the only council to incorporate light trespass, over-lighting, and skyglow across its lighting policies. Five councils implemented controls for two forms of light pollution, with light trespass being common to all five. Seven councils included a single control, most frequently targeting light trespass (five councils), while glare and over-lighting were each addressed by one council, respectively. The remaining fifteen councils had no identifiable light pollution controls within their policies.

Light trespass controls were the most prevalent, present in thirteen of the fifteen councils that implemented light pollution regulations. Glare controls were the second most common, appearing in seven councils, followed by over-lighting controls in six councils and skyglow controls in four. With the exception of the Northern Beaches Council (NSW), councils lacking a formal lighting policy had no provisions addressing any form of light pollution.

All of the DarkSky communities analysed had provisions for each of the four light pollution components analysed in this study. In contrast, only one-tenth of the analysed Australian councils implemented measures covering all four components. Furthermore, half of the Australian councils examined had no provisions for any form of light pollution control. A further assessment of light pollution policies was conducted relative to the best-practice standards of DarkSky.

3.3. Adherence to DarkSky Requirements for Effective Lighting

The DarkSky eligibility criteria consider both technical lighting requirements and broader social or environmental objectives. The DarkSky framework outlines eight key lighting control requirements encompassing: shielding, short-wavelength restrictions, limits on unshielded luminaires, over-lighting controls, public outdoor lighting frameworks, signage lighting restrictions, sports-field regulations, and amortisation periods for non-compliant installations [54]. This section evaluates the degree to which Australian local councils meet these technical criteria, relative to certified DarkSky communities to identify strengths, deficiencies, and potential pathways toward best-practice alignment.

3.3.1. DarkSky Requirements Adherence

None of the councils achieved more than four of the eight DarkSky requirements (fully), with Wyndham City (VIC) representing the highest level of compliance (see Table 4). Twelve councils failed to meet any requirements beyond basic accounting requirements, seven of which had no publicly accessible lighting policy. Councils with recently revised policies tended to perform better; however, no consistent pattern was observed across states, population sizes, or urban–rural classifications. Note that all of the DarkSky communities assessed explicitly enforced all eight control requirements.

Table 4.

The specific DarkSky light pollution controls found for the assessed Australian councils.

Eighteen of the Australian councils implemented two or more of the control tactics, with the use of over lighting controls being the most common DarkSky requirement that was met. Eight of the thirty councils had suitable public lighting frameworks or had enforced adaptive controls. Four of the councils had sports and recreation lighting. Wyndham City Council and Sunshine Coast Regional Council were the only two out of thirty councils to enforce suitable colour temperature requirements. Only two of the councils enforced signage lighting restrictions (the City of Sydney and the City of Port Adelaide-Enfield). To meet the amortization period, all existing private and public lighting fixtures needed to be compliant within 10 years resulting in seven councils partially meeting the strict requirement. Of the 30 Australian councils, four of them partially met shielding requirements, falling short of the DarkSky standard but still a noteworthy attempt. None of the councils implemented unshielded lighting provisions.

3.3.2. Correlated Colour Temperature and Minimum Colour Rendering Index Lighting Controls

Lighting colour quality was found to be one of the weakest areas of alignment between Australian and DarkSky policies, as seen below in Table 5. Only six of the 30 councils referenced correlated colour temperature (CCT) or colour rendering index (CRI) in their documents. Two councils enforced CCT below 3000 K, while three required “cool-white” lighting of 4000 K or higher, in contradiction to environmental and health recommendations. Six councils referenced minimum CRI levels of ≥70, primarily to ensure roadway visibility rather than ecological protection.

Table 5.

Australian councils and DarkSky (DS) certified communities that enforce colour temperature or rendering index criteria in their lighting policy.

All of the DarkSky communities mandated CCT below 3000 K, with several recommending 2700 K or lower depending on land use and ecological sensitivity. Groveland and Flagstaff differentiated CCT thresholds according to lighting class, demonstrating a flexible yet environmentally responsible approach. These findings emphasise the disparity between Australian policy and global evidence-based practice, where lower CCT is a standard requirement for sustainable outdoor lighting.

3.3.3. Australian Standards and Energy Provider Adherence to DarkSky Requirements

Many councils rely on either the standard or the energy providers as a default compliance method instead of creating their own policies. Consequently, to further check the relationships between institutions and regulations that may impact the policies of the Australian councils, the characteristics of the Australian Standards (Table 6) and both Australian Standards and energy providers (Table 7) in terms of the eight DarkSky controls are summarised.

Table 6.

Australian standards adherence to DarkSky light pollution controls.

Table 7.

Australian energy provider adherence to DarkSky light pollution controls and Australian Standards.

The Australian standards examined were AS 4282:2023—Control of the Obtrusive Effects of Outdoor Lighting and the AS 1158 series: Lighting for roads and public spaces. AS 4282:2023 was the only standard that complied with any DarkSky light pollution controls, meeting three of the requirements. The requirements met by AS 4282:2023 were lighting colour restrictions, restrictions for over lighting and regulations on new installations of publicly owned outdoor lighting. The DarkSky lighting restrictions reflect a similar pattern to the common lighting controls enforced by the local councils indicating that the assessed councils’ strongest mitigation efforts are typically to reduce over illuminance and controlling the type of light emitted. Of the seven standards in the AS 1158 series, none of them comply with any of the DarkSky light pollution controls. The AS 1158.6:2015 standard focuses on luminaire performance and is the only standard in the AS 1158 series to not comply with AS 4282:2023, reinforcing a gap between technical performance criteria and broader environmental protection measures.

Energy provider documentation demonstrated weak alignment with the DarkSky controls. Of the nine Australian energy providers identified to own or influence public lighting regulations for the assessed councils, none of their policies align with any of the DarkSky light pollution controls. Ausgrid, Energex and TasNetworks all explicitly state and conform to the Australian lighting Standards. Endeavour, Jemena and SAPN only comply with the 1158 series, while Western Power does not comply with any of the Standards. Two of the providers (AusNet and Powercor) did not have a public policy to examine.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the state of lighting and light pollution policy in local governments and associated entities across Australia and found that very little has been done. The changes required to reduce light pollution are known and include: lighting curfews [19], shielding [20], improved luminaire design [21] and the introduction of smart lighting systems [22]. Many of these changes would also save the parties involved money, while also reducing emissions. Yet only three of the 30 assessed councils have any mention of light pollution and of those three, only the Sunshine Coast Regional Council (QLD) and the City of Wyndham (VIC) have updated their lighting policies in the last five years to note light pollution effects (e.g., with the inclusion of a light pollution fact sheet at the Sunshine Coast Council [55]). The same two councils met at least three of the DarkSky criteria. Furthermore, while DarkSky communities tended to have colour controls for their lighting, very few councils did, despite the known associations between colour impacts and health for wildlife and humans. Taken more broadly, the findings of this study show that Australian local governments and cities are at least haphazard (as found by [29]), or blocked outright by higher-level entities. That is, across Australia, there were a few examples of local governments that had taken some steps toward implementing policies and practices addressing light pollution, but they were the exception, not the norm.

The experimentation that local governments are often able to do thanks to their autonomy and variety [34] (e.g., as found in parts of rural France [26]), may have led to a few councils having sufficient technical expertise at the same time as having leaders that took an active approach to environmental and lighting policy (the conditions suggested by [35]) that they developed some lighting policy. That is, as would be expected with polycentricism, a few of the local governments were more innovative than their peers [37] and there was a variety of approaches to lighting policy, due to the ability of some local governments to act independently (per [39]), but, overall, very few acted.

The rare and notable example of local governments and cities developing light pollution policies is represented by cities such as Groveland (USA), where after substantial community involvement, the town has been recognised as a DarkSky Place. The community needed to implement dimming measures, shielding and substantial community education, yet once complete the community has found considerable satisfaction in their efforts [56] Another notable example is Palm Beach, Australia, which became the first recognised DarkSky Urban Place in the Southern Hemisphere in 2024. Upgrading LED lighting to amber luminaires and policy reforms targeted at reducing the duration and number of lights, transformed Palm Beach into a haven for astronomical observation, despite its proximity to Sydney, a major urban centre [57]. These communities show that effective light pollution policy is achievable, but they remain among the few exceptions. The reliance on independence and variety generating experimentation, key forces of polycentrism, appears to lead to too few cases of policy action regarding light pollution.

Groveland (USA) and Palm Beach (Australia) are relatively small communities. In contrast, Flagstaff, Arizona which has the largest population of any DarkSky community (currently approx. 75,000), stands as a model for successful light pollution control through local self-regulation [58]. The city relies almost entirely on municipal enforcement, because there are no strong state or federal laws in the United States mandating DarkSky compliance. Instead, the initiative was driven internally by community advocacy and local governance, with the city embedding DarkSky requirements into binding municipal law through its Outdoor Lighting Code (Division 10-50.70) [59]. The presence of the Lowell Observatory, one of the city’s most significant scientific and cultural institutions, further strengthen the local priority to preserve dark skies, motivating early adoption and continued enforcement of lighting controls [60]. Thus, polycentric environments have led to examples of urban settings with rigorous light pollution controls, although none of the DarkSky communities had a population over 100,000.

Electricity providers, state governments and Standards Australia provided little if any impetus to further the efforts of the local governments, although they could have had a substantial dampening impact. An interesting corollary that has received little attention before is that quite often the local governments outsourced the operation and management of their lighting infrastructure to state- and privately-owned energy providers. Further reducing their autonomy, the majority of the councils that were in partnership with energy providers had explicit provisions that lighting infrastructure design was “pending energy distributor approval” [61]. That extra hurdle of having to get an external party on side may also have played a role in the poor state of light pollution policy in local governments across Australia.

That is, a possible constraint on the light pollution policies of local governments in Australia may be that their autonomy is often limited due to the high levels of involvement of state-level entities (per [44]). For example, approximately half of the Australian councils assessed were reliant on their energy provider to manage and operate their lighting. That lack of autonomy may have held back many of the councils from experimentation, precluding the unfettered application of polycentrism and perhaps holding back or entirely thwarting local desires for change. The end result is that, just as with local governments in the USA [30], the substantial majority of Australian local governments have not introduced many policies or practices to manage light pollution.

Unfortunately, in terms of multi-level theory, most of the higher level or technical institutions influencing the light pollution policies of local governments in Australia have little in the way of light pollution policies themselves, leaving little opportunity for councils to leverage multi-level expertise, efforts and connections to help them improve their lighting policies. Of the energy providers analysed in this study, none incorporated provisions into their lighting policy that met DarkSky light pollution requirements and of the nine energy providers examined, six had no reference to AS 4282:2023, a minimum standard addressing the control and mitigation of light pollution effects. Therefore, energy provider inaction constitutes an additional hurdle for Australian councils to overcome before positive actions can be undertaken to address ALAN. Exceptions do exist, such as in New South Wales where the relationship between the energy provider AusGrid and Palm Beach (Australia) helped create the Southern Hemisphere’s first DarkSky place. Overall though, the lack of light pollution provisions or reference to relevant standards demonstrates that, for the majority of energy providers, light pollution is not a primary issue.

Perhaps a key step in the direction of harnessing some of the strengths of a multi-level approach would be if national or state governments in Australia introduced more laws such as those introduced in Spain (per [28]), with considerations for their enforceability by addressing the concerns raised about Germany’s ALAN regulations (per [43]). However, the mere existence of national and state regulation sets up pools of technical expertise that can be harnessed in a multi-level approach. For example, Fulda, Germany follows a clear lighting framework that connects European, national, state, and local rules. At the highest level, the city follows DIN (national) and EN (European) standards for street lighting and for workplace lighting, which set the main technical requirements for brightness and safety [62]. These standards are supported by the Hessische Bauordnung (HBO), the state building code that covers construction and environmental requirements. Fulda further applies federal environmental guidelines that limit light emissions, while also enforcing its own local lighting policy [63]. Together these rules ensure Fulda meets both technical standards and environmental goals, making it one of the leading cities in Europe for responsible nighttime lighting. These examples suggest that having light pollution policies at national and state levels may provide a supportive context for policies at the local level, especially because not all councils have the funding to be able to develop a critical mass of expertise in light pollution or other aspects of sustainability.

There are other characteristics of national legislation from around the world that could be informative for the development of Australian light pollution legislation, potentially enabling Australia to leapfrog some of the problems faced by some systems. For example, ALAN regulation could include the binding mitigation measures in Korean legislation, combined with flexibility of British regulations, to reduce the impact of lighting [43]. Once those higher-level entities start taking steps forward, then local governments will be able to use the collaborative, network oriented approaches to multi-level policy development discussed by [41,42] to develop more of their own light pollution policies.

Limitations

Perhaps the main limitation of this study is its focus on the Australia context, which has a very urbanised population with almost 80% of the population in towns and cities with a population over 100,000 [46], whereas in other countries the concentration of the populace in large urban areas may be considerably less. For example, approximately 30% of the population are in towns with a population over 100,000 in the USA [36]. Larger population centres may face extra difficulties with light pollution controls, which may make the low rates of policy found in this study a sign of substantial efforts at scale, yet that same scale also makes the possible cost savings that arise from many light pollution controls more substantial. At the least, this study is a key step in trying to bridge from the light pollution policies of larger urban areas toward the possibilities for controlling light pollution achieved by DarkSky communities.

Another limitation is that this study was based on policy document analysis, rather than alternative data-collection methods such as satellite imaging. Future research could incorporate satellite data to explore the extent to which local government policies impact actual lighting outcomes, such as skyglow and start to be able to determine which policies effectively mitigate different light pollution indicators.

5. Conclusions

A lot of energy is wasted through inefficient or excessive illumination, resulting in higher greenhouse gas emissions [1]. Beyond the emissions’ impacts, the light pollution itself has direct environmental consequences that damage natural ecosystems [9] and detrimentally impact human health [10,11]. Light pollution needs to be reduced and a key lever in the system for managing light pollution are the entities responsible for operating and regulating much of the lighting, local governments.

Low rates of light pollution policies were found in this study despite managing light pollution being one of the simplest and most cost-effective steps local governments can take toward sustainability [31], because addressing light pollution helps to reduce energy consumption, lower emissions, and improve environmental quality [32,33]. Yet very little action to address light pollution has been taken by local governments in Australia, entailing that step-changes in effort are needed for these councils to get to a broader state of sustainability.

The few examples of Australian local governments having introduced some light pollution policies and practices may be a reflection of the breadth of experimentation possible in a polycentric system, but those few examples are not spreading. The power of polycentrism may be constrained in the Australian context due to fiscal capacity and externalities such as climate change (per [36]). Polycentrism may not lead to wide scale change in the Australian context, but it does help generate pilot cases and test sites and their associated model ordinances.

The polycentric approach may not be leading to wide change among Australian local governments, but the multi-level approach might work, if there were light pollution policies at higher levels to leverage. If national regulations were developed, learning from the strengths and weaknesses of the national policies of other countries (per [43]), then local governments could use collaborative, network oriented approaches to multi-level policy development (as discussed by [41,42]) to develop more of their own light pollution policies.

Future research should further explore the influence of energy providers and identify community or political mechanisms to encourage improved lighting practices, especially for larger urban communities. Overcoming current barriers through further investigation will enhance future understanding and support Australian councils in adopting more consistent and effective light-pollution management frameworks so as to reduce light pollution, reduce emissions and enhance the sustainability of our urban and natural environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S., J.L., S.R. and J.R.; methodology, J.S., J.L., S.R. and J.R.; formal analysis, J.S., J.L., S.R. and J.R.; investigation, J.S. and J.L.; data curation, J.S. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.S., S.R. and J.R.; supervision, S.R. and J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used as the basis for analyses in this article are all publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACT | Australian Capital Territory |

| ALAN | Artificial light at night |

| AS | Australian Standards (a formal institutional name) |

| CCT | Colour correlated temperature |

| CRI | Colour Rendering Index |

| DS | DarkSky |

| HBO | Hessische Bauordnung |

| LED | Light emitting diode |

| NSW | New South Wales (the most populace state in Australia) |

| NT | Northern Territory |

| QLD | Queensland |

| SA | South Australia |

| TAS | Tasmania |

| VIC | Victoria (the second most populace state in Australia) |

| WA | Western Australia |

References

- Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic. Light Pollution Reduction Measures in Europe: Working Paper. In Proceedings of the International Workshop Light Pollution 2022, During the Czech Presidency of the Council of the European Union, Brno, Czech Republic, 26 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bará, S.; Falchi, F. Artificial light at night: A global disruptor of the night-time environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyba, C.C.M.; Kuester, T.; Sánchez de Miguel, A.; Baugh, K.; Jechow, A.; Hölker, F.; Bennie, J.; Elvidge, C.D.; Gaston, K.J.; Guanter, L. Artificially lit surface of Earth at night increasing in radiance and extent. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1701528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchi, F.; Cinzano, P.; Duriscoe, D.; Kyba, C.C.M.; Elvidge, C.D.; Baugh, K.; Portnov, B.A.; Rybnikova, N.A.; Furgoni, R. The New world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barentine, J.C. Artificial light at night: State of the science 2023. In Zenodo; 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candolin, U.; Filippini, T. Light pollution and its impact on human health and wildlife. BMC Environ. Sci. 2025, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.E. Light pollution and its effects on human health and the environment: A review. Asian J. Environ. Ecol. 2024, 23, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, C.; Garbazza, C.; Spitschan, M. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie 2019, 23, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcón, J.; Torriglia, A.; Attia, D.; Viénot, F.; Gronfier, C.; Behar-Cohen, F.; Martinsons, C.; Hicks, D. Exposure to artificial light at night and the consequences for flora, fauna, and ecosystems. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 602796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, S. Light at night and circadian rhythms: From the perspective of physiological anthropology research. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2024, 43, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-C.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, G.; Li, J. Research progress about the effect and prevention of blue light on eyes. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 11, 1999–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweater-Hickcox, K.; Narendran, N.; Bullough, J.; Freyssinier, J. Effect of different coloured luminous surrounds on LED discomfort glare perception. Light. Res. Technol. 2013, 45, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, Y.; Kim, I.; Choi, A.; Sung, M. A preliminary study of an evaluation method for discomfort glare due to light trespass. Light. Res. Technol. 2016, 49, 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchi, F.; Cinzano, P.; Elvidge, C.D.; Keith, D.M.; Haim, A. Limiting the impact of light pollution on human health, environment and stellar visibility. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2714–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Energy. What Is Sky Glow? Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/ssl/text-alternative-version-what-sky-glow (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Kocifaj, M.; Barentine, J. Air pollution mitigation can reduce the brightness of the night sky in and near cities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luginbuhl, C.B.; Walker, C.E.; Wainscoat, R.J. Lighting and astronomy. Phy. Today 2009, 62, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, S.; Alam, F.; Lovreglio, R.; Ooi, M. How to measure light pollution: Systematic review of methods and applications. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 92, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska-Dabkowska, K.M.; Schernhammer, E.; Hanifin, J.P.; Brainard, G.C. Reducing nighttime light exposure in the urban environment to benefit human health and society. Science 2023, 380, 1130–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LED Light Expert. Light Shields Explained—Outdoor Parking Lot Light Shielding. Available online: https://www.ledlightexpert.com/Light-Shields-Explained--Outdoor-Parking-Lot-Light-Shielding_b_42.html?srsltid=AfmBOor90aj3Kb6DxZ70Ou9YbupV3VoZyc9-cn-MlQD0r3d-7tKMfNrl (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Esposito, T.; Radetsky, L.C. Specifying non-white light sources in outdoor applications to reduce light pollution. Leukos 2023, 19, 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.D. Analysis of the benefits of intelligent LED lighting control systems in commercial environments. Energy Rep. 2025, 4, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Jia, D. A review of the characteristics of light pollution: Assessment technique, policy, and legislation. Energies 2024, 17, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroer, S.; Hölker, F. Light pollution reduction. In Handbook of Advanced Lighting Technology, 1st ed.; Karlicek, R., Sun, C.-C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 109–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Fryc, I.; Listowski, M.; Martinsons, C.; Fan, J.; Czyżewski, D. A paradox of LED road lighting: Reducing light pollution is not always linked to energy savings. Energies 2024, 17, 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapostolle, D.; Challéat, S. Making darkness a place-based resource: How the fight against light pollution reconfigures rural areas in France. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2021, 111, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DarkSky International. Lighting Zones for Codes and Ordinances. Available online: https://darksky.org/resources/guides-and-how-tos/lighting-zones (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Méndez, A.; Prieto, B.; Aguirre i Font, J.M.; Sanmartín, P. Better, not more, lighting: Policies in urban areas towards environmentally-sound illumination of historical stone buildings that also halts biological colonization. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeemering, E.S. Sustainability management, strategy and reform in local government. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothukuchi, K. Mitigating urban light pollution: A review of municipal regulations and implications for planners. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 9, 1663–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.W.; Smyth, T. Why artificial light at night should be a focus for global change research in the 21st century. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, A.M. The increasing effects of light pollution on professional and amateur astronomy. Science 2023, 380, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölker, F.; Moss, T.; Griefahn, B.; Kloas, W.; Voigt, C.C.; Henckel, D.; Hänel, A.; Kappeler, P.M.; Völker, S.; Schwope, A.; et al. The dark side of light: A transdisciplinary research agenda for light pollution policy. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R. Streetlighting in England and Wales: New technologies and uncertainty in the assemblage of streetlighting infrastructure. Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 2228–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Kern, K. Local government and the governing of climate change in Germany and the UK. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2237–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsy, G.C.; Warner, M.E. Cities and sustainability: Polycentric action and multilevel governance. Urban Aff. Rev. 2015, 51, 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Reflections on Vincent Ostrom, public administration, and polycentricity. Public Admin. Rev. 2012, 72, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Organizational economics: Applications to metropolitan governance. J. Institutional Econ. 2010, 6, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebout, C.M. A pure theory of local expenditures. J. Political Econ. 1956, 64, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, V.; Tiebout, C.M.; Warren, R. The organization of government in metropolitan areas: A theoretical inquiry. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1961, 55, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, A.; Siqueiros-García, J.M.; Mazari-Hiriart, M.; Guerra, A.; Lerner, A.M. Mobilizing institutional capacities to adapt to climate change: Local government collaboration networks for risk management in Mexico City. npj Clim. Action 2024, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, R. Local governments in multilevel systems: Emergent public administration challenges. Am. Rev. Public Admin 2014, 44, 47S–62S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroer, S.; Huggins, B.J.; Azam, C.; Holker, F. Working with inadequate tools: Legislative shortcomings in protection against ecological effects of artificial light at night. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, B.; Dollery, B. Autonomy versus oversight in local government reform: The implications of “home rule” for Australian local government. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 2012, 46, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standards Australia. 2025. Available online: https://www.standards.org.au/standards-catalogue/sa-snz (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Kelly, K. National urban policy. Urban Policy Res. 2013, 31, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. In The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion, 2nd ed.; Huberman, A.M., Miles, M.B., Eds.; Sage Publications INC: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Thomson, S.B. Framework analysis: A qualitative methodology for applied policy research. J. Admin. Gov. 2008, 4, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Population. Population in Local Government Areas. Available online: https://population.gov.au/data-and-forecasts/dashboards/population-local-government-areas (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- DCCEEW. Protected Area Locations. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Commonwealth of Australia. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/land/nrs/science/protected-area-locations#:~:text=Over (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- DarkSky International. Dark Sky Place Finder. Available online: https://darksky.org/what-we-do/international-dark-sky-places/all-places/?_select_a_place_type=international-dark-sky-community (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- AS 4282; Control of the Obstructive Effects of Outdoor Lighting. Australian Standards: Sydney, Australia, 2023.

- AS 1158; Lighting for Roads and Public Spaces. Australian Standards: Sydney, Australia, 2020.

- Darksky International. DarkSky Recognized Codes and Statutes Guidelines. Available online: https://darksky.org/what-we-do/advancing-responsible-outdoor-lighting/darksky-recognized-codes-and-statutes/darksky-recognized-codes-and-statutes-guidelines/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Sunshine Coast Council. Environmental Pollution. Available online: https://www.sunshinecoast.qld.gov.au/environment/environmental-nuisances-and-pollution/environmental-pollution (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- DarkSky International. Dark Sky Community: Groveland, FL—Official Website. Available online: https://www.groveland-fl.gov/592/Dark-Sky-Community (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Northern Beaches Council. Palm Beach Headland Urban Night Sky Place Application December 2023. Available online: https://files-preprod-d9.northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au/nbc-prod-files/media/files/2024-06/palm-beach-headland-urban-night-sky-place-application.pdf?1762478413 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Flagstaff Dark Skies Coalition. Available online: https://flagstaffdarkskies.org/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Flagstaff Zoning Code Division 10-50.70: Outdoor Lighting Standards. Available online: https://www.codepublishing.com/AZ/Flagstaff/html/Flagstaff10/Flagstaff1050070.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Lowell Observatory, History of Pluto. Available online: https://lowell.edu/discover/history-of-pluto/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Townsville City Plan. Available online: https://www.planning.townsville.qld.gov.au/townsville-city-plan (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- PIL International. Lighting Products. Available online: https://www.performanceinlighting.com/ww/en/en-13201-2-2015 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- City of Fulda. Application for Provisional Designation of the City of Fulda as an International Dark Sky Community. Available online: https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/776b212d-9d74-4e20-a387-913f01166c7e/downloads/FULDA_Germany_RZ_DarkSkyCity_11-2018.pdf?ver=1729471969254 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.