1. Introduction

Since the 1970s, the global demand for material extraction, production, consumption, and waste generation processes has been high, threatening the sustainability of resources for future generations [

1]. According to the latest United Nations Environment Programme [

2] statistics, global natural resource consumption is expected to increase by 60% by 2060 compared with 2020. This projection highlights the urgent need to transform production and consumption patterns toward sustainable models.

Goyal et al. [

3] showed that consumption habits driven more by desires than needs have led to a shift toward sustainable consumption models. This shift implies that consumers are increasingly becoming aware of the environmental impact of their decisions and are seeking alternatives to minimize their ecological footprint [

4,

5]. This approach is conducive to achieving planetary sustainability and promoting the well-being of future generations by ensuring the continued availability and suitable quality of natural resources for subsequent generations [

6].

Bulut et al. [

7] stated that the shift toward sustainable consumption behaviors (SCBs) depends on each country’s specific context and the norms and policies implemented in this regard. This implies that individual preferences and external factors, such as the availability of sustainable products, government regulations, and social norms, influence consumer decisions.

It is crucial to consider the contextual elements that effectively foster SCBs among consumers. In the case of Colombia, an emerging and mega-diverse country, a sustainable consumption, and production policy has been in place since 2010, but efforts in this direction date back to the 1990s. The National Policy on Sustainable Production and Consumption aims to guide changes in production and consumption patterns toward environmental sustainability. This policy seeks to promote sustainable practices among consumers and producers and establish a regulatory framework that facilitates transition to a more sustainable economic model.

In this context, this study aims to analyze sustainable consumption patterns in Bogotá, the most populous city in Colombia, taking into account gender and generational variables. This approach is relevant because different demographic groups may exhibit distinct consumption motivations and behaviors [

8]. Furthermore, the literature has not addressed this topic in the Colombian context.

The study employed a quantitative methodology, developing 38 items related to SCBs. Data analysis was conducted using multinomial regression analysis, enabling the identification of variations in sustainable consumption patterns across generations: centennials (Z), millennials (Y), Generation X, and baby boomers (BB).

According to Vergura et al. [

5], research on SCBs is relatively recent, beginning in the late 1990s. Studies have extensively explored SCB patterns in relation to gender, showing that women tend to engage in SCBs more frequently than men [

7,

9,

10,

11]. However, comparisons between generations (Z, Y, X, and BB) have received less attention. Bulut et al. [

7,

12,

13] have examined the influence of generations on SCBs, suggesting that this factor has a greater influence compared with other sociodemographic variables.

Despite substantial progress in understanding sustainable consumption behavior, a significant research gap remains concerning systematic cross-generational analyses, particularly within emerging economies such as Colombia. While extensive scholarship has comprehensively documented sustainable consumption patterns through the lens of gen-der differentiation [

7,

9,

10], consistently showing that women display stronger tendencies toward adopting sustainable consumption practices than men, intergenerational comparative analyses have received considerably less scholarly attention. Existing studies are largely confined to dyadic comparisons between Generations Y and Z [

11], with investigations encompassing multiple generational cohorts remaining notably scarce [

12,

13].

This limitation is particularly pronounced within Latin American contexts, creating a substantial empirical void regarding how sustainable consumption behaviors manifest differentially across generational cohorts in Bogotá, Colombia. Furthermore, existing empirical studies on sustainable consumption have rarely differentiated between strong and weak forms of sustainable practices, thereby limiting understanding of their depth and transformative potential. Examining multiple generational cohorts constitutes a fundamental research imperative, as each generational segment has been shaped by distinctive social, technological, and economic phenomena, resulting in differentiated behavioral patterns [

7,

8]. In Colombia, where coexisting generational cohorts have witnessed the economic liberalization of the 1990s, the digital revolution, and evolving trajectories of environmental awareness, understanding these generational distinctions advances scholarly knowledge on sustainability while providing essential empirical foundations for future research and sectoral discussions on responsible consumption practices. Accordingly, this study seeks to address the following research question: Do significant differences exist in sustainable consumption behaviors across generational cohorts (Generation Z/Centennials, Generation Y/Millennials, Generation X, and Baby Boomers) and gender within the context of Bogotá, Colombia?

2. Literature

2.1. Sustainable Consumer

Sustainable consumers make purchase and consumption decisions based on respect for environmental resources [

14,

15]. This perspective on consumption extends beyond the mere satisfaction of immediate needs or desires; sustainable consumers are aware that sustainable consumption habits are essential for preserving resources for future generations [

6]. In this context, improving the quality of life becomes a primary objective for such consumers [

16]. Consequently, consumption assumes a political and ethical dimension: when faced with the question “What should I consume?,” individuals respond through actions aimed at reducing or preventing harm to ecological systems.

Fischer et al. [

17] indicated that improving quality of life through sustainable consumption depends on various factors, including resource efficiency, adopting renewable energy sources, minimizing waste, and understanding the lifecycle of consumed goods and services. In this context, sustainable consumers seek to reduce or avoid external consequences to achieve intra- and inter-generational justice [

18].

Thus, rational, and informed sustainable consumers aim to minimize the external consequences of consuming goods and services by optimizing the use of non-renewable natural resources and reducing waste generated after consumption [

11].

In essence, SCBs are characterized by the extent to which individual actions related to the selection, acquisition, use, and disposal or prosumption of goods contribute to the creation or maintenance of external conditions that enable all human beings to satisfy their fundamental needs in the present and in the future [

19].

2.2. Sustainable Consumer Behavior

Research on SCBs has demonstrated a direct relationship between consumer actions and their impact on the environment [

5,

20,

21,

22]. In this context, Kempton et al. [

23] highlighted that SCBs can take various forms, such as purchasing green products, recycling waste, using energy-efficient appliances, making ethical investments, switching to organic foods, modifying transportation methods, buying recycled products, or adopting minimalist habits. However, a concern for environmental impact underlies all these actions, translating into conscious consumption habits on a small scale.

Antonides and Raaij [

24] defined consumer behavior as “a set of physical and mental actions of individuals and small groups, including considering, purchasing, using, maintaining, and disposing of market products, domestically produced goods, and services from the market, public, and domestic sectors” (p. 24). Their definition highlights that consumption decisions are linked to consumers’ values such as environmental concerns and are also influenced by governmental policies and regulations at national and global levels. According to Harris et al. [

25], such regulations are crucial for promoting SCBs and fostering an environment that encourages responsible behaviors aimed at environmental conservation.

The United Nations has classified SCBs based on the primary essential activities of human life [

26]. Recent literature supports this perspective, emphasizing that these activities are essential for studying SCBs (see

Table 1).

Recent studies [

36] have classified SCBs into two main groups: (1) market behaviors, which include purchasing eco-friendly products, acquiring goods responsibly, and reducing waste; and (2) household behaviors, which involve reducing consumption, engaging in collaborative consumption, minimizing waste, and properly disposing post-consumption waste.

Literature identifies various categories and areas related to SCBs [

37]; however, these behaviors can manifest as either strong or weak, depending on the geographical context and the cultural and social norms influencing each individual [

7].

Furthermore, SCBs can be classified into weak and strong behaviors; the former is characterized as superficial as the practices adopted by consumers do not effectively address structural problems related to sustainability and economic growth [

38]. A consumer may engage in sustainable actions, such as recycling or purchasing eco-friendly products, but this does not necessarily imply that their lifestyle is genuinely sustainable.

In contrast, a consumer displaying strong SCBs adopts a more comprehensive approach, prioritizing the reduction in consumption of essentials and adopting a minimalist lifestyle. Such a consumer seeks information about product lifecycles and ensures that their purchasing decisions contribute to environmental protection and resource preservation for future generations; thus, consumers with strong SCBs prioritize well-being that is not based on consumption [

39].

2.3. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Patterns

Regarding SCB patterns, [

7,

10,

11,

40] found that women tend to exhibit more environment-friendly consumption behaviors than men [

41]. Additionally, [

11] highlighted that gender is a key sociodemographic factor influencing SCBs, noting that women’s concern for sustainability significantly affects their purchase decisions.

Few studies have compared SCBs across the four generations (Z, Y, X, and BB) [

7,

11,

12].

Table 2 presents the relevant findings regarding SCB patterns in these generations.

Eryiğit et al. [

49] reveal that younger generations, particularly Generation Z, display distinctive patterns of sustainable fashion consumption, characterized by a stronger inclination toward second-hand apparel acquisition and circular fashion practices. Their findings suggest that generational cohorts operate under different motivational frameworks guiding sustainable consumption decisions, with younger consumers prioritizing environmental activism, whereas older generations emphasize resource conservation. Moreover, research on gender differences consistently demonstrates that women exhibit higher levels of environmental awareness in their consumption decisions. Tyagi [

50] empirically examined gender dynamics in sustainable consumption within emerging market contexts, finding that women engage more frequently in environmentally conscious behaviors, such as preferring eco-friendly alternatives, product repair and maintenance, and resource conservation practices. Collectively, these studies highlight the importance of simultaneously examining gender and generational factors, as their interaction generates complex behavioral patterns that demand nuanced understanding to inform effective policy and marketing interventions.

Despite evidence demonstrating gender differences in sustainable consumption behaviors [

50], no studies have systematically examined these differences within urban Colombian contexts, thereby limiting our understanding of gender dynamics in this emerging market.

2.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Generational and Gender Differences

Cohort theory [

51,

52] conceptualizes generations as social locations defined by shared historical experiences during formative periods. Individuals exposed to common socio-historical events in adolescence develop stratified worldviews, wherein early impressions shape a fundamental lens through which later experiences are interpreted. These formative experiences generate distinctive value systems that persist throughout life, influencing consumption preferences and behavioral patterns [

53].

Contemporary lifespan [

54,

55] development perspectives suggest that generational differences arise from historical events and cultural transformations. During adolescence and emerging adulthood, critical periods for identity formation, individuals construct value systems that translate into lasting behavioral commitments. However, Costanza and Finkelstein [

56] acknowledge that precisely delineating generational boundaries presents significant methodological challenges; nevertheless, they argue that generational categorizations remain valuable for understanding differentiated patterns of behavior and social orientations.

Regarding gender schema theory [

57], it posits that through early socialization, men and women internalize cultural content associated with masculine and feminine roles. Otnes and Zayer [

57] and Zhao et al. [

58] affirm that gender is a social, dynamic, and contextual construct; therefore, the norms, values, beliefs, and identities acquired during individuals’ development influence self-perception, decision-making, and consumption behavior. This perspective is grounded in the notion that men and women acquire not only differentiated attributes and skills but also social obligations and expectations that modulate their relationship with the environment and consumer goods [

57,

58].

In this regard, [

58] show that women, socialized toward care and cooperation, tend to maintain more altruistic and biospheric values, which favor the adoption of green and prosocial consumption practices, while men exhibit more utilitarian and egoistic orientations, shaped by social expectations of competitiveness and efficiency [

58]. These differences not only reflect individual dispositions but also stem from social and cultural norms that assign differentiated roles to each gender [

57,

58]. Furthermore, recent research indicates that sustainable consumption is culturally associated with feminine characteristics, creating psychological barriers among men who fear deviating from traditionally masculine values [

59,

60,

61].

On the other hand, the value-belief-norm theory [

61] posits that gender differences in values and personal norms influence specific purchasing patterns [

58,

59,

60]. From a relational and situated perspective on gender, it can therefore be argued that observed differences in consumption, especially in responsible or sustainable consumption, reflect trajectories of socialization, normative expectations, and particular sociocultural contexts [

58,

59,

60].

2.5. Hypothesis

H1. There are significant differences in sustainable consumption behaviors across Generations Y, Z, and X+BB.

The sustainable consumer behavior literature indicates that each generation develops sustainability-related behaviors shaped by its specific historical, technological, and cultural context. Eryiğit et al. [

49,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

61] demonstrate that younger cohorts, particularly Millennials (Generation Y) and Centennials (Generation Z), tend to engage more proactively in responsible consumption behaviors, emphasizing waste reduction, product reuse, and support for brands aligned with environmental values. In contrast, Generation X exhibits a more pragmatic orientation toward sustainability, focusing on resource efficiency, product durability, and rational consumption planning. These generational contrasts, also reported by [

8,

12], suggest that environmental awareness and sustainable behaviors evolve according to the formative experiences and prevailing value systems of each generational cohort.

H2. There are significant gender-based differences in sustainable consumption behaviors.

Empirical evidence indicates that gender is a key factor explaining variations in sustainable consumption. Tyagi [

50,

52,

58,

59,

60] found that women consistently demonstrate higher engagement in environmentally responsible behaviors, including purchasing eco-friendly products, reusing containers, and separating household waste. Similarly, [

7,

10] reported greater female participation in actions such as minimizing food waste, conserving resources, and choosing locally produced goods. These patterns correspond to strong forms of sustainable consumption [

7,

39], which entail lifestyle changes and heightened ethical awareness. In contrast, men predominantly display weak sustainable consumption behaviors, characterized by utilitarian and efficiency-oriented choices—improving resource use without major shifts in overall consumption volume or habits.

3. Methodology

The study sample consisted of 746 participants recruited online via Qualtrics using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method. Detailed sociodemographic and generational characteristics of the sample are presented in

Table 3. Regarding the studied generations, we considered the following cohorts: BB (1946–1964), X (1965–1980), Y (1981–1996), and Z (1997–2012).

Given the small sample size of the BB generation, we merged it with the Generation X sample because both generations share similar sociocultural characteristics, particularly in terms of experimenting with methods to address emerging global issues related to sustainability. This enhanced the representativeness of our data and helped fulfill the research objectives by enabling a more detailed and meaningful analysis.

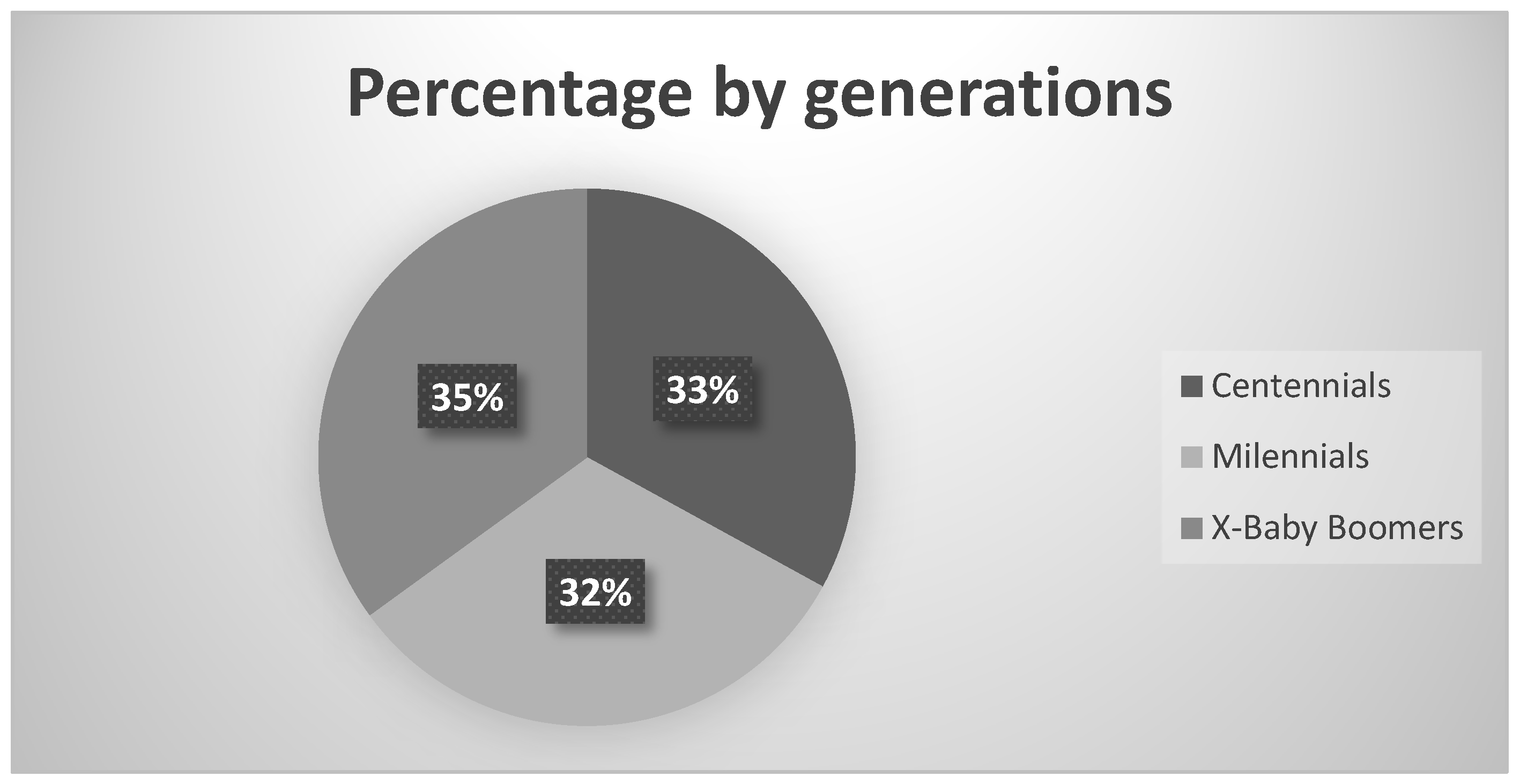

Figure 1 presents the percentage of participants by generation.

3.1. Instrument

To develop a comprehensive set of items measuring sustainable consumption behaviors, an exhaustive literature review was conducted across multiple academic databases, from which 43 preliminary items were derived. These items were subsequently evaluated by a panel of three experts, two full professors specializing in sustainable consumption and one associate professor with expertise in quantitative methods, who assessed each statement for relevance and conceptual coherence. Following consensus, five items were discarded due to ambiguity, resulting in a final instrument comprising 38 items. A pilot study involving 10 participants was then conducted to evaluate item clarity and instrument reliability, allowing for further refinement prior to large-scale implementation.

Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert-type scale measuring the frequency of SCBs, where 1 indicated “never”, 2 “seldom”, 3 “sometimes”, 4 “frequently”, and 5 “always”.

3.2. Data Analysis

The analysis was conducted in three phases. In the first phase, we used principal component analysis to estimate the weight of each behavioral item in a conceptual dimension of sustainable consumption by each generation. Principal component analysis is a multivariate analytic technique that combines information of several variables in a small number of components [

62]. This technique can estimate the weight of each variable or item in the component. In the second phase, we used multinomial regression to compare the probability that each behavior is related to a generation. Multinomial regression models are a multivariate technique used on nominal dependent variables and estimate the odds that an independent variable is present in a group [

63]. For the purpose of estimation, a comparison group is necessary, and the analysis is conducted in relation to this group. When the odds are lower than 1 and statistically significant, the studied behavior is considered to have been more frequent in the comparison group. In contrast, when the odds are above 1 and statistically significant, the studied behavior is more frequent in the other group.

To compare SCBs by gender, we used a multinomial regression model for each gender.

4. Results

4.1. Description of Sustainable Consumption Behaviors by Generation

Table 4 presents the results of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for each item, providing an initial descriptive assessment by item and generation. The closer an item’s value is to 1, the higher the frequency of the behavior associated with sustainable consumption. The results are visualized through a heat map that displays items from highest to lowest frequency of sustainable consumption behaviors (SCBs) across generations. The values shown in the heat map correspond to component loadings obtained from the PCA, ranging from −1 to 1. These values should not be interpreted as means, but as indicators of the relative weight or frequency of each behavior within each generation—the closer a value is to 1, the greater its contribution or significance in that generational group.

The heatmap employs a warm color gradient ranging from red (indicating the highest frequency or weight of the behavior in the principal component) through orange and yellow, to beige and white, which denote the lowest values. This color scale facilitates rapid visual interpretation: red highlights the most frequent behaviors, orange and yellow indicate intermediate frequencies, and lighter tones represent the least adopted practices within each generation.

The significant differences in consumption frequency and the evaluated items reveal generational dynamics in SCBs. Among the 38 items, Generation Z stands out with five high-frequency behaviors: B17 (0.711), B18 (0.765), B20 (0.745), B29 (0.745), and B36 (0.723). These behaviors are related to water conservation, proper waste disposal, and environmental care, reflected in reducing meat consumption and avoiding products that harm the environment, provided information about the product’s effects is available.

Generation Y exhibits moderate levels of sustainable consumption behaviors. Although its overall pattern is less pronounced compared to Generations Z and X+BB,

Table 3 indicates that Millennials actively engage in specific practices such as recycling old items (B5) and seeking information online prior to purchasing (B30). These behaviors reflect a selective yet consistent commitment to sustainability across certain dimensions of everyday consumption.

4.2. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Patterns by Generation

The multinomial logistic regression analysis presented in

Table 5 provides robust empirical support for Hypothesis 1, which posits that significant differences exist in sustainable consumption behaviors among Generations Y, Z, and X+BB. The results reveal 15 statistically significant behavioral distinctions across the three generational pairwise comparisons, with confidence intervals and significance levels ranging from

p < 0.05 to

p < 0.001, thereby confirming the hypothesis in its entirety.

Critically, the analysis reveals a dual pattern: while 39.5% of behaviors (15 items) demonstrate significant generational differentiation, 60.5% of evaluated behaviors (23 items) show no statistically significant differences across any generational comparison. This convergence indicates a substantial shared baseline of sustainability engagement across cohorts, suggesting that certain environmental practices transcend generational identity. This nuanced finding moves beyond simple generational dichotomies, revealing that Colombian consumers across age cohorts share foundational environmental values while expressing distinct behavioral emphases shaped by cohort-specific experiences.

4.2.1. Generation Z vs. X+BB

The multinomial logistic regression analysis comparing Generation Z to Generation X+BB in terms of sustainable consumption identified 11 SCBs with significant differences. Of these, four behaviors are more likely to be adopted by Generation Z, while seven behaviors occur more frequently in Generation X+BB.

Among the notable behaviors, buying second-hand clothing and using it until the end of its lifespan (B1) showed a significant result, with an odds ratio of 1.65 and a confidence interval of 1.36–2.01. This finding indicates that Generation Z is 65% more likely to opt for second-hand clothing. Additionally, they are 78% more likely to order only the food they can consume (B15); they also show a 30% greater tendency to carry a reusable water bottle (B31) and have a 26% higher likelihood of reusing shower or washing machine water (B38).

In contrast, Generation Z is less likely to adopt several SCBs compared with Generation X+BB. Specifically, they are 33% less likely to use public transportation (B2), 28% less likely to choose products with biodegradable packaging (B3), and 31% less likely to dispose of their waste in designated bins (B20). Additionally, they are 19% less likely to practice home recycling (B21), 40% less likely to print only what is necessary (B26), 26% less likely to avoid littering in public spaces (B28), and 33% less likely to seek information about sustainable products before making a purchase (B30).

4.2.2. Generation Y vs. X+BB

Comparing Generation Y and Generation X+BB revealed eight behaviors with significant differences. Three behaviors are more likely to be adopted by members of Generation Y, while five behaviors are less likely to be adopted by them.

Generation Y is 23% more likely to minimize excessive consumption to preserve natural resources for future generations (B4). Although

Table 4 indicates a higher descriptive mean for Generation X+BB (0.704) compared with Generation Y (0.609), this difference is reversed in the multinomial regression once sociodemographic factors are controlled. The positive and significant odds ratio (1.23) therefore reflects a conditional effect: under comparable conditions of occupation, gender, and education, the likelihood of engaging in this behavior is higher among millennials than among older cohorts. This finding suggests that Generation Y exhibits a relatively stronger sensitivity to resource preservation when other contextual variables are accounted for.

They are also 44% more likely to order only the food they can consume to avoid waste (B15) and 43% more likely to reduce meat consumption due to environmental concerns (B36). Conversely, Generation Y is less likely to engage in certain SCBs. For example, they are 3% less likely to use public transportation (B2) (not statistically significant), 26% less likely to bring reusable bags when shopping (B25), 33% less likely to print only when strictly necessary (B26), 25% less likely to avoid littering in public spaces (B28), and 34% less likely to search online for information about sustainable products before making a purchase (B30).

4.2.3. Generation Y vs. Z

The multinomial regression analysis revealed six statistically significant differences between the SCBs of Generation Y to Generation Z. Public transportation use (B2) is a significant behavior among Generation Y, who are 44% more likely to adopt this practice than Generation Z. Additionally, they are 25% more likely to implement home recycling (B21) and 37% more likely to avoid littering in public spaces (B29).

In contrast, Generation Y is 25% less likely to purchase second-hand clothing (B1) than Generation Z. They are also 19% less likely to carry a reusable water bottle (B31), although they tend to favor the purchase of energy-efficient products and appliances (B32). Additionally, they exhibit a greater tendency to reduce meat consumption for environmental reasons (B36).

4.3. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Among Men Across Generations

The analysis of sustainable consumption behaviors among men across generational cohorts provides robust empirical support for Hypothesis 2, which posits that gender exerts a significant influence on sustainable consumption practices. As shown in

Table 6, male respondents consistently exhibit patterns of weak sustainable consumption [

38,

39], characterized by efficiency-oriented and utilitarian behaviors rather than transformative lifestyle changes. Across Generations X+BB, Y, and Z, men predominantly engage in actions focused on resource optimization and waste prevention—such as energy efficiency (B10, B11, B32), responsible water use (B27), and selective recycling (B19, B21)—reflecting a pragmatic rather than value-driven or deeply transformative orientation toward sustainability. Although these behaviors hold environmental relevance, they align with the notion of weak sustainability, emphasizing “doing more with less” without implying substantial reductions in overall consumption levels or fundamental shifts in consumption patterns (

Table 6).

4.3.1. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Patterns Among Men: Z vs. X+BB

Analyzing SCBs among men from Generation Z vs. X+BB reveals eight behaviors with significant differences in their likelihood of adoption. In particular, Generation Z stands out for their greater inclination toward sustainable practices. They are 55% more likely to buy products made from recycled plastic or cardboard (B19), 47% more likely to carry a reusable water bottle (B31), and 2.07 times (107%) more likely to order only the food they can consume (B15).

However, Generation Z is less likely to engage in certain SCBs; they are 38% less likely to use public transportation (B2) and 41% less likely to choose products with biodegradable packaging (B3). Additionally, they are 45% less likely to practice recycling at home (B21) and 40% less inclined to avoid littering in public spaces (B28). Finally, they are 43% less likely to wash their clothes using a full load in the washing machine (B29) and show significant reluctance to seek online information about sustainable products before making a purchase (B30).

4.3.2. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Patterns Among Men: Y vs. X+BB

Three SCBs show significant differences in the likelihood of adoption by men from Generation Y vs. X+BB. For example, Generation Y men are 41% more likely to consume goods and services efficiently to avoid waste (B11) and 131% more likely to order only the food they can consume (B15). Conversely, they are 31% less likely to reduce their water and electricity consumption considering the well-being of others (B10).

4.3.3. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Patterns Among Men: Y vs. Z

Comparing Generation Y with Generation Z reveals significant differences in various sustainability-related behaviors. For example, Generation Y men are 65% more likely to use public transportation (B2), 69% more inclined to avoid purchasing products they consider harmful to the environment (B17), 69% more likely to practice recycling at home (B21), and 136% more willing to wash their clothes using a full load in the washing machine (B29).

In contrast, Generation Y men are less likely to adopt certain behaviors compared with Generation X+BB. In particular, they are 38% less likely to reduce their water and electricity consumption considering the well-being of others (B10). Additionally, they are 38% less inclined to turn off the faucet while brushing their teeth (B27), 29% less likely to carry a reusable water bottle (B31), and 32% less willing to purchase energy-efficient products and appliances (B32).

4.4. Sustainable Consumption Behaviors Among Women Across Generations

The analysis of sustainable consumption behaviors among women across generational cohorts provides complementary empirical evidence supporting Hypothesis 2, which posits that gender significantly influences sustainable consumption practices. As shown in

Table 7, female respondents exhibit a consistent tendency toward strong sustainable consumption behaviors [

38,

39,

61], characterized by transformative lifestyle changes and value-driven actions rather than solely efficiency-oriented practices. Across Generations X+BB, Y, and Z, women predominantly engage in circular economy practices and consumption reduction—such as second-hand purchasing (B1), sustainable mobility (B2), waste prevention (B12, B15, B26), local consumption (B13), product repair and lifespan extension (B14), responsible disposal (B18), resource conservation (B23, B27, B38), informed purchasing (B30), and dietary changes motivated by environmental concerns (B36). These behaviors reflect a transformative and deeply value-driven orientation toward sustainability (

Table 7). Environmentally significant and socially conscious, they align with the concept of

strong sustainability, emphasizing fundamental reductions in overall consumption and substantial shifts in consumption habits—moving beyond operational efficiency to embrace lifestyle transformation.

4.4.1. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Patterns Among Women: Z vs. X+BB

The differences between Generation Z and X+BB are evident in several significant behavioral aspects. For example, women from Generation Z are 108% more likely to buy second-hand clothes and use them for an extended period (B1). Additionally, they are 69% more inclined to consume local products, contributing to a reduced ecological footprint associated with transportation (B13). They are also 67% more likely to repair products to extend their lifespan (B14) and 82% more likely to purchase only the amount of food they can consume when shopping (B15). Furthermore, they are 55% more likely to reuse shower or washing machine water for other household tasks (B38).

Conversely, women from Generation Z exhibit certain behaviors less frequently than BB. They are 36% less likely to use public transportation (B2), 47% less inclined to spend their money in a way that prevents waste and excessive purchases (B12), 51% less likely to use both sides of the paper for writing and printing (B23), 54% less likely to print only what they consider necessary (B26), and 48% less likely to turn off the water while brushing their teeth (B27).

4.4.2. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Patterns Among Women: Y vs. X+BB

Comparing Generations Y and X+BB reveals that Generation Y women are 47% more likely to buy second-hand clothes and use them to their full potential (B1). Additionally, they are 72% more likely to reduce their meat consumption due to environmental concerns (B36). In contrast, they are 40% less likely to print only what they consider necessary (B26) and 40% less likely to seek online information about sustainable products before making a purchase (B30).

4.4.3. Sustainable Consumption Behavior Patterns Among Women: Y vs. Z

Comparing Generations Y and Z shows that Generation Y women are 52% more likely to use public transportation (B2) compared with Generation Z women. They are also 50% more inclined to avoid wasteful spending and excessive purchases (B12) and 63% more likely to dispose of batteries and mobile devices at designated recycling points (B18); however, they are 30% less likely to buy second-hand clothes and use them for an extended period (B1) and 32% less likely to reuse washing machine water.

5. Discussion

The results of this study confirm both hypotheses and provide a deeper understanding of sustainable consumption within the Colombian context.

Hypothesis 1, which proposed that generational cohort membership significantly influences sustainable consumption behaviors, was confirmed. Statistically significant differences were identified in 15 of the 38 behaviors analyzed (

p < 0.05 to

p < 0.001), indicating the existence of distinct patterns across generations. Generation Z exhibits an adaptive form of sustainability integrated into daily life, expressed through practices such as using reusable bottles, purchasing second-hand clothing, and reusing water [

32,

33,

46,

47]. These actions reflect a flexible approach to sustainability embedded in everyday habits rather than grounded in a structured ideology.

In contrast, Generation X and Baby Boomers (X+BB) display a more systematic orientation toward sustainability, focused on resource conservation, waste reduction, and the deliberate search for information on the environmental impact of products [

7]. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as the social and historical experiences of these cohorts differ substantially: Generation X matured during the digital transition, while Colombian Baby Boomers were shaped by internal conflict and economic instability. These contextual differences may bias the combined estimates; therefore, the results for X+BB should be regarded as conservative reflections of potentially heterogeneous trends.

A relevant finding is that the generational differences observed do not appear to be determined by the availability of sustainable products or by current production and consumption policies. The generational patterns identified seem to be primarily shaped by individual dispositions and lifestyle orientations rather than by market stimuli [

30,

34]. In this sense, the sustainability observed across cohorts emerges from personal and cultural frameworks rather than institutional or economic mechanisms [

51,

52]. This suggests that, although public policies on sustainable production and consumption assume that a greater supply of sustainable products will foster responsible behaviors, such a supply-driven approach has not yet translated into real changes in consumption.

Hypothesis 2, which proposed that gender is a determining factor in sustainable consumption, was also confirmed. Across all generational cohorts, women showed significantly greater engagement in transformative practices, while men’s behaviors were predominantly utilitarian. This finding aligns with previous studies identifying women as more responsible in their consumption decisions [

7,

11,

12,

62], but it extends this evidence by demonstrating that, within the Colombian urban context, women’s practices align with the principles of strong sustainability.

Women’s actions—such as repairing, reusing, reducing consumption, and purchasing locally—reflect a lifestyle oriented toward care, moderation, and intergenerational responsibility that transcends efficiency-driven motivations. In contrast, men tend to adopt more selective or instrumental actions, such as recycling or using public transportation, associated with weak sustainability, which emphasizes efficiency over transformation.

Within generational subgroups, Generation Z women stand out for their particularly strong commitment to circular practices and consumption reduction [

46,

47], while Millennial men exhibit patterns more oriented toward efficiency. Meanwhile, men and women from Generation X+BB adopt sustainable behaviors linked to informed decision-making and traditional conservation practices.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that both generation and gender are key dimensions for understanding sustainable consumption. They also suggest that promoting responsible behaviors requires the inclusion of cultural, motivational, and ethical perspectives, beyond economic incentives or product availability.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that sustainable consumption in Colombia arises primarily from individual practices grounded in personal agency, values, and identity, rather than from institutional or market frameworks alone. The analysis reveals clear generational and gender-based patterns in sustainable consumption behaviors, carrying significant implications for both theory and practice.

Empirically, the study operationalizes the distinction between weak and strong sustainable consumption behaviors at the individual level. It shows that women systematically exhibit strong behaviors characterized by transformative, reduction-oriented practices, whereas men predominantly display weak behaviors centered on efficiency improvements without lifestyle change. This distinction validates the weak–strong dichotomy as a measurable behavioral construct. Notably, thirteen behaviors dependent on the availability of sustainable products show no generational differences, despite Colombia’s policy efforts to expand the supply of green products, suggesting that increased availability alone does not lead to differentiated consumption patterns. In contrast, genuine generational differences emerge mainly in discretionary, lifestyle-transformative behavior, such as participation in the circular economy, dietary shifts, and mobility choices, where consumer agency and values exert the strongest influence.

These findings carry direct theoretical significance. They operationalize weak and strong sustainable consumption as measurable constructs, demonstrate that policy-driven product availability is insufficient to shape distinct consumption patterns, and underscore the primacy of lifestyle choices guided by individual agency and identity. For practitioners and policymakers, the documented heterogeneity in behaviors across gender and generation calls for segmented sustainability strategies. Managers should tailor product offerings and marketing messages to resonate with each segment’s motivational drivers, while policymakers must move beyond expanding product supply to facilitate and incentivize behavioral transformation through social-norm campaigns, fiscal instruments, and community programs that embed sustainable habits into everyday life. A monitoring framework incorporating generation- and gender-specific indicators would further support adaptive policy refinement.

This research has several limitations. First, the use of fixed birth-year thresholds to define cohorts may introduce classification errors for individuals born in boundary years. Second, aggregating Baby Boomers with Generation X due to sample size constraints may obscure distinctive cohort characteristics. Third, the sample’s restriction to Bogotá limits the generalizability of findings to rural populations. Moreover, while this study did not examine the underlying motivations for sustainable consumption behaviors, it establishes a foundation for future research to explore the influence of Colombia’s National Policy on Sustainable Production and Consumption on individual behaviors and the broader social and economic contexts shaping sustainable consumption across gender and generational groups.