Abstract

Health tourism, including spa-based treatments, is an important segment of global travel, and its growth reflects increasing demand for experiences that combine physical well-being with contact with nature. Polish health spa resorts are rich in balneological resources such as mineral and thermal waters, peloids, and therapeutic gases, and they offer a variety of products and services based on geoheritage. This paper introduces the concept of geoproducts—goods and services inspired by abiotic nature—and explores their role in spa tourism and sustainable regional development. Through questionnaire surveys conducted in 48 Polish spa towns, the study examines how these resources are promoted and exploited, the forms and functions of local geoproducts, and the barriers to their dissemination. The results show that, although most spas acknowledge the value of geoheritage, promotion primarily employs traditional formats and is limited in educational content. Nevertheless, there is strong local interest in developing geotourism and geoeducation, especially through the creation of unique, regionally rooted products. The study underlines the potential of geoproducts to enhance spa attractiveness, support local economies, and contribute to broader environmental awareness.

1. Introduction

Health tourism, i.e., travel aimed at improving health and physical and mental condition, constitutes a significant part of global tourism [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. All forecast data indicate a continuous increase in interest in such tourism of 15–20% per year (e.g., [8], accessed on 16 September 2025). Within health tourism, alongside spa and wellness tourism and medical tourism, there is also spa tourism. This is offered in facilities referred to as health spa resorts and involves the provision of health spa resort treatment services, including the treatment of chronic diseases, convalescence, disease prevention, health education, and the promotion of health [9]. Spas in Poland and many European countries offer therapeutic treatments based on natural balneological resources, and, although they have followed different historical paths, they share a common feature: they have always been places of relaxation based on natural resources [7]. These resources are natural abiotic features that are important for human culture and life and are referred to in the literature as “geoheritage” [10]; their richness is referred to as “geodiversity” [11]. In this context, an important role is played by geoproducts. These are goods and services created or inspired by abiotic nature; they serve both recipients and producers and influence education and sustainable regional development [12,13,14,15,16,17].

The literature on geoheritage and geoproducts in health spa resorts is scant. These aspects have been described in the example of, inter alia, the health spa resorts of Vyšné Ružbachy, Lúčky, (Slovakia) and San Giovanni (Italy) [18]. The authors drew attention to valuable forms of abiotic nature associated with travertines (travertine lakes, waterfalls, craters, springs), which are an inherent part of these health spa resorts while also constituting a potential geotourism attraction for visiting tourists [18,19,20,21]. In Poland, attention has been paid to the unique geoheritage of, among others, the health spa resorts of Swoszowice [22] and Ciechocinek [23] and health spa resorts in the balneological region of the Polish flysch Carpathians, i.e., Piwniczna-Zdrój, Muszyna-Zdrój, and Krynica-Zdrój [24]. The opportunities for developing geotourism within the national health spa resort areas have been emphasised either sporadically or as an additional feature to the main range of tourism offerings [25,26,27,28].

The aim of this article is to analyse national health spa resorts in terms of the resources that constitute their products and the opportunities for their use in promoting geoheritage. A survey relating to the nature, promotion, and current use of balneological raw materials was conducted among local government representatives in spa areas. The concept of geoproducts applied was that of a tool for education and sustainable development based on exploiting valued features of abiotic nature in health spa resorts.

Geoproducts in Spas

Geoproducts were first defined in UNESCO documents relating to the creation of geoparks as goods and services created from or inspired by geoheritage or geodiversity, and they have been similarly described in the latest documents [12,13]. Typical geoproducts include handicrafts, souvenirs, and decorations, e.g., fossil casts. Farsani et al. (2012) [14] identified the characteristics of geoproducts functioning in geoparks as follows: locality (e.g., being made of local materials or a symbol of local geological or geomorphological heritage); utility as a pedagogical tool (geoeducation that combines traditional products with concepts and interpretations in the Earth sciences); commerciality (an element of sales and local economic development); and sustainability (environmentally friendly and in tune with local culture).

Dryglas and Miśkiewicz (2014) [15] proposed categories of geoproducts according to a methodology used in the marketing of tourism services. These are the following: (1) items, e.g., geotourism guides and maps; geotourism information boards; cosmetic, medicinal, food, or handicraft products inspired by geoheritage, etc.; (2) facilities, e.g., geological museums, educational geocentres, gem shops; (3) services, e.g., geotourism guide services, (4) events, e.g., minerals fairs, geological picnics; (5 geotourism trails; and (6 areas, e.g., geoparks. However, Rodrigues et al. (2021) [16] have presented a different division of geoproducts, namely the following: (1) handicrafts, promotional products, and gadgets inspired by geodiversity; (2) medicinal products, food, and cosmetics produced from abiotic natural resources; (3) geotourism infrastructure facilities; and (4) geotourism services.

Regardless of the proposed definition or division, the key element of the geoproduct is geoheritage—abiotic elements of nature that affect how humans function, including spa activities. The creation of geoproducts is also related to the transfer of knowledge and raising awareness about geoheritage, so the educational aspect is important, as is its usefulness to sustainable development [14,16,17].

Products are the subject of economic research, and there is a rich literature on the subtype “tourist product” in which the issue is approached variously, depending on the author (e.g., [17,18]). It is not the purpose of this work to analyse the various definitions of this subtype, but to note that the scope of tourism products notably includes a special type called “Health Tourism Product” [29]. The health experience of a tourist who visits areas with valued health spa resort features is described in part based on the desire for new knowledge [30]. This knowledge should also concern geoheritage and its impact on human health, which is crucial for the creation of health spa resorts; therefore, this work attempts to analyse health spa resort products that are based on geoheritage.

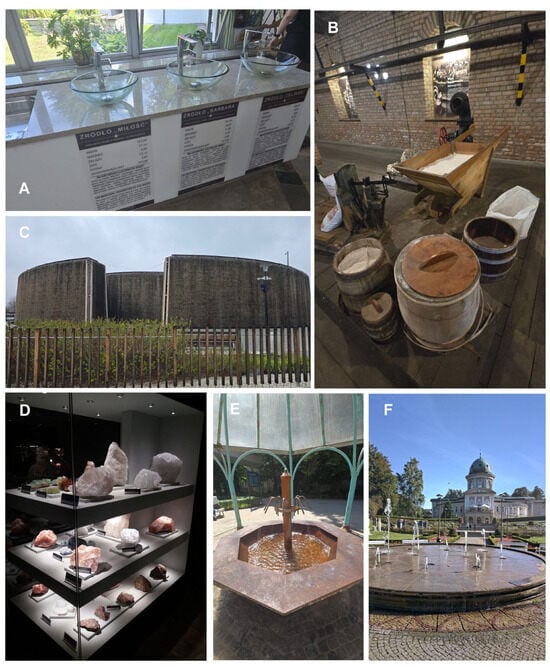

Health spas clearly rely on natural abiotic resources—primarily, underground waters (i.e., mineral, medicinal, unique waters, brines, and thermal waters), peloids (medicinal muds), and medicinal gases (e.g., [22,23]). The main chemical types are bicarbonate, sulphate, and chloride waters, which, depending on the concentrations of specific components or their temperature, can be ferrous, fluoride, iodide, sulphide, silicic, or carbonic acid or oxalic, radon, and thermal waters. Peloids (medicinal muds) include medicinal peats, lake muds, gyttjas, clays, loams, and loess. H2S, CO2, and Rn are considered medicinal gases. The natural resources of health spa resort areas also include the climate and landscape, which is sometimes referred to as the “therapeutic landscape” [31]. It can be safely stated that the landscape of spa areas is influenced mainly by the nature of the local geoheritage. All these resources can be used to create geoproducts and thus to develop geotourism and geoeducation in health spa resorts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Examples of products and facilities available in Polish health resorts. (A) mineral water drinking hall in Nałęczów, the descriptions in the Polish language on this figure mean the names of the springs and its and their mineralogical composition, (B) Museum of the Saltworks and Spa Medicine in Ciechocinek, (C) graduation tower in Busko-Zdrój, (D) educational exhibition in the Salt Mine in Wieliczka, (E) inhalation mushroom-shaped fountains in Sopot, (F) historic spa building and park in Lądek-Zdrój.

2. Materials and Methods

The methods used in this study included library research, a questionnaire method, and simple GIS analyses.

The first step the authors took to develop this topic was a literature review, primarily of publications describing health resorts (e.g., [1,7,23,24,26,32,33,34]) and geological, hydrological, and hydrogeological maps. This step also involved an analysis of the national register of health resorts and protected health resort areas, along with their treatment directions [35]. This library search allowed us to select the 70 locations where survey research was conducted.

The questionnaire method was conducted in May and June 2025. A survey form was sent to 70 recipients. The recipients were government offices of towns that have the status of a health spa resort (48) or health spa resort protection area (7), and of former health spa resorts (11) and towns with a high health spa resort potential (5) (according to the list by Chowaniec & Zuber, 2008 [26]).

The survey consisted of 14 questions, mainly closed-ended, which concerned the following information: (i) the availability and methods of transferring knowledge about the origin of balneological minerals in the health resort or spa town; (ii) the need to promote knowledge about these raw materials, methods of this promotion, sources of its financing, and barriers that the authorities have to deal with when creating promotional products (open-ended question); (iii) the availability of health resort geoproducts and local products or souvenirs in the health resort or spa town, as well as problems with cheap souvenirs not related to the cultural heritage of the region; (iv) cooperation with scientific institutions (open-ended question) and participation in cyclical meetings called the GEO-PRODUCT Forum [36] (English version of the form attached as a Supplementary File).

The survey form was sent by email, and two weeks later an email reminder to complete the survey was sent. Ultimately, the authors contacted by telephone the towns that had not responded to the emails. Ultimately, 48 out of 70 towns participated in the research, which constitutes 68.57% of all surveyed towns, of which statutory health spa resorts constitute 83.3%. Respondents were primarily well-educated employees of spa communes and cities who are responsible for reporting directly to the spa town or are involved in issues related to environmental protection and sustainable development.

Maps and spatial analyses were performed using ArcGIS Pro 3.2.1 software.

3. Study Area

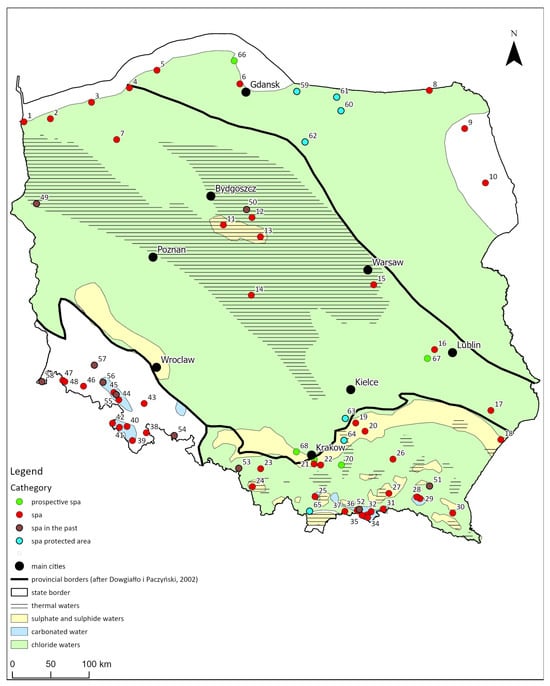

Due to the diverse geological structure of Poland, the authors of many scientific publications have attempted to characterise the hydrogeological structure and divide Poland into provinces according to differences in types and conditions of occurrence of water (e.g., [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]). In this article, the authors employ the division based on the occurrence of mineral waters in connection with tectonic units, as proposed by Dowgiałło and Paczyński (2002) [46]. The authors distinguish the Precambrian platform province (A), the Palaeozoic platform province (B), the Sudetes province (C), and the Carpathian province (D) (Figure 2).

The diversity of mineral and thermal waters found in Poland is also characterised by the degree of mineralisation, temperature, and the medicinal properties of the waters. Therefore, three main types of water have been distinguished: carbonic acid and acidic waters, sulphate and sulphide waters, and chloride waters. Acidic waters occur only in mountainous areas (the Carpathians and the Sudetes); sulphate and sulphide waters dominate in the Carpathians and Pre-Carpathian Sinkhole and in some regions of the Palaeozoic platform province; and chloride waters are the most common and occur throughout almost the entire country except for the Sudetes and local platform provinces [47]. One unique phenomenon is the occurrence of radon waters in the Sudetes.

The Precambrian platform province (A) is characterised by the presence of a crystalline basement located at depths ranging from 200 to 3500 m, on which lies an overburden of Palaeozoic and Mesozoic sediments [48,49,50]. The waters occurring in Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks are chloride-containing and their mineralisation depends on depth and on the degree to which they are isolated from the surface by overlying formations. Mineralisation values range from 10 to 50 g/dm3 to 200–300 g/dm3 (located in Mesozoic formations within the Peri-Baltic Depression, where their salinity is due to the Zechstein evaporite series) [47].

Figure 2.

Location of the studied facilities (spa resorts) in the context of Poland’s mineral and thermal water resources [26,51].

There are five health spa resorts in the Precambrian platform province: Ustka (5), Sopot (6), Gołdap (8), Augustów (9), and Supraśl (10), and four health spa resort protection areas: Miłomłyn (62), Lidzbark Warmiński (60), Górowo Iławieckie (61), and Frombork (59) (numbering in brackets in accordance with Figure 1). The aforementioned chloride-sodium and iodide water is found in the health spa resorts of Ustka (5), Sopot (6), Gołdap (8), Frombork (59), and Lidzbark Warmiński (60). This water has also been documented in the town of Puck (66). Alongside mineral waters, other valuable balneological resources found in this area include peat deposits: Augustów (9), Supraśl (10), Gołdap (8), Miłomłyn (62), and Górowo Iławieckie (61). These deposits are associated with an impermeable Quaternary substrate, in which ice-dammed lakes formed after the last glaciation. These conditions became an excellent place for the decomposition of organic matter and the development of peat bogs in the late Quaternary and Holocene.

The Palaeozoic platform province (B) is located southwest of the Teisseyre–Tornquist line and it is a single, contiguous unit encompassing Palaeozoic and Mesozoic formations [49,50]. The total thickness of the formations is over 9000 m. A characteristic feature of this area is the presence of Zechstein rock series forming salt structures (diapirs).

These structures influence the mineralisation of contemporary or older waters originating from atmospheric precipitation. However, the formation of sodium chloride waters is not only related to this infiltration, as there are also relict ones. These are the remains of the contents of Zechstein and Triassic lakes created by the precipitation of chemical sediments [47]. The occurrence of relict marine waters in Mesozoic series is also probable. These waters are found mainly in the health spa resorts of Kołobrzeg (3), Świnoujście (1), Kamień Pomorski (2), Połoczyn (7), Innowrocław (11), Ciechocinek (12), Wieniec (13), Uniejów (14), Konstancin Jeziorna (15), and in the former health spa resort of Czerniewice (50).

In many places, complex hydrodynamic conditions and tectonics cause the ascent of mineralised chloride waters, which sometimes appear at or near the surface. Natural brine springs were often used in the production of table salt in the Middle Ages (Kołobrzeg), but also today (Kujawy) [47]. Within the Palaeozoic platform, there are also sulphate and sulphate-sulphide waters (Wieniec-Zdrój (13), Krzeszowice (68)). Their presence is associated with the occurrence of gypsum and anhydrite. Mineralised chloride-sodium waters extracted from great depths are often thermal waters (Ciechocinek (12), Uniejów (14)). The Palaeozoic platform province also features peat deposits from which medicinal peat is extracted for use in the health spa resorts of Dąbki (4), Kołobrzeg (3), Świnoujście (1), Kamień Pomorski (2), Połoczyn (7), Wieniec (13), and Krasnobród (17), as well as in the health spa resort protection area in Pinczów (63). Peat was also the main medicinal product used in the former spa town of Trzcińsko (49).

The Sudetes Province (C) is divided into two regions: the Sudetes and the Fore-Sudetic Monocline [49,50,52], which are separated by the Sudetes Marginal Fault [47,52]. The distinguishing feature of these regions is the presence of younger Cenozoic sediments in the Fore-Sudetic Monocline, whereas these sediments appear only rarely in the Sudetes. Complexes of Precambrian and Palaeozoic metamorphic rocks, as well as Variscan igneous intrusions (which occur on the surface in the Sudetes), are buried under Cretaceous and Cenozoic formations in the Fore-Sudetic Monocline. Disjunct structures also extend into the Fore-Sudetic Monocline and play an important role in groundwater circulation. The most characteristic type of mineral waters found in the Sudetes province is that of bicarbonate waters. These have various cationic compositions (iron, magnesium, calcium, silicon, sodium) and are additionally supersaturated with carbon dioxide (acid). Carbon dioxide is the main factor responsible for the increased mineralisation of the waters, as it intensifies their interaction with the rocks bearing them (which are mainly metamorphic and igneous). Its transport from great depths and its saturation of shallow-circulating groundwater is greatly facilitated by tectonic discontinuities, which are one of the most characteristic elements of the geological structure of the Sudetes.

Apart from the sour waters, another important balneological mineral is thermal water, which occurs here in the form of springs: Cieplice Śląskie-Zdrój (46), Lądek-Zdrój (38), and boreholes Duszniki-Zdrój (41) [47]. The thermal waters owe their high temperature to the deep circulation of underground waters and their geothermal heating in areas with significant differences in elevation. A unique feature of the Sudetes mineral waters is their radon waters, whose occurrence is related to the migration of water in highly weathered and tectonised igneous and metamorphic rocks. Radon waters occur in the health spa resorts of Lądek-Zdrój (38), Długopole (39), Przerzeczyn-Zdrój (43), Szczawno-Zdrój (45), and Świeradów-Zdrój (47) [47].

Due to its diverse geological structure [53], the Carpathian province (D) has been divided into three regions: the Pre-Carpathian Sinkhole (northern part of the province), the Outer Carpathians (central part of the province), and the Inner Carpathians (southern, near-Tatra part of the province) [47]. The northern border of the Carpathian province was determined based on the extent of Miocene chemical sediments (series containing gypsum, anhydrite, and rock salt). These formations are also associated with the formation of sulphate-calcium, sulphide, and chloride-sulphate-calcium waters, as well as weakly mineralised, unique sulphide waters. These waters are used in the health spa resorts of Horyniec (18), Busko-Zdrój (19), Solec-Zdrój (20), Goczałkowice-Zdrój (23), and Swoszowice (21), and in the prosperous Mateczny spa park (69). These waters also occur in the former health spa resorts of Jastrzębie-Zdrój (53) and Brzozów (51), and in the health spa resort protection area of Kazimiera Wielka (64). An additional balneological feature is the spa facility of the former salt mines in Wieliczka (22) and Bochnia (70).

The sulphur waters of the Carpathian province are formed by the dissolution of hydrogen sulphide resulting from the bacterial reduction in sulphate minerals in the presence of organic matter [47,54]. Mineralised sulphate waters also contain a chloride ion, whose origin is related to the leaching of Miocene saline sediments and the presence of sea waters that may come from the Neogene and older periods. In the southern part of the Pre-Carpathian Sinkhole, there are chloride waters containing iodine (Goczałkowice-Zdrój (23)).

The Outer Carpathians region is rich in mineralised waters, often specific ones, among which the specific mineral waters found in 13 health spa resorts have so far been recognised as medicinal. In the western part of the region, these are mainly chloride and iodide waters: Ustroń (24), Rabka-Zdrój (25); in the central part, there are carbonated waters: Krynica-Zdrój (32), Muszyna (34), Piwniczna-Zdrój (36), Iwonicz-Zdrój (28), Rymanów-Zdrój (29), Wysowa-Zdrój (31), Złockie (33), Żegiestów (35), and Szczawnica (37); and, in the eastern part, there are bicarbonate-chloride waters: Polańczyk (30) and Wapienne (27) [55].

The mineralised waters of the Outer Carpathians region are characterised by their diverse origin and the occurrence of both monogenetic and polygenetic mixtures [56]. The first region includes shallow-infiltration waters (max. 200 m) that saturated into tectonic discontinuity zones with carbon dioxide migrating from greater depths. Polygenetic mixtures include waters that, in addition to the infiltration component, also contain variously abundant admixtures of water of non-infiltration origin, i.e., relict sea waters, waters released from clay minerals in the processes of diagenesis and/or metamorphism, and in some places also waters constituting the product of hydrocarbon oxidation. Unlike monogenetic waters, they are more highly mineralised, most often being chloride and/or bicarbonate waters, and are enriched in heavy isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen [47].

The last region of the Inner Carpathians is associated with the occurrence of an Artesian basin in the Podhale basin, where mineralised thermal waters occur in Eocene and Triassic carbonate formations at depths ranging from 1000 to 3500 m and are exploited for heating and recreational purposes [57,58]. The capacity of Artesian springs of temperatures up to 80–86 °C is up to 500 m3/h, and the water mineralisation remains within the range of 0.1–0.25% [47,59]. Also in the Inner Carpathians region, in the Orava–Nowy Targ Basin, there are deposits of peat and therapeutic mud, which are extracted and used medicinally [60,61,62,63]. The area protected by the health spa resort in Czarny Dunajec contains an area of peat deposits.

4. Results

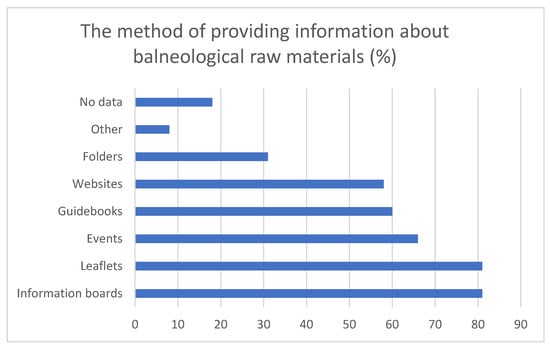

The survey results can be divided into three thematic blocks. The first block relates to the methods of conveying knowledge about the origin of mineral waters, peat, or other balneological raw materials that can be found in the area of a health spa resort/town with the status of a health spa resort protection area. Eighty-six percent of respondents answered that such information is available in their towns and is mainly available on information boards (81%), in leaflets (81%), in guidebooks (60%), in folders (31%), or on the websites of the spa towns or municipalities and cities (58%). This information is also disseminated during events held at health spa resorts (66%) or in other ways, e.g., special scientific publications or promotion in tourist information centres (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Communication method by which the studied spa towns provide information about balneological raw materials.

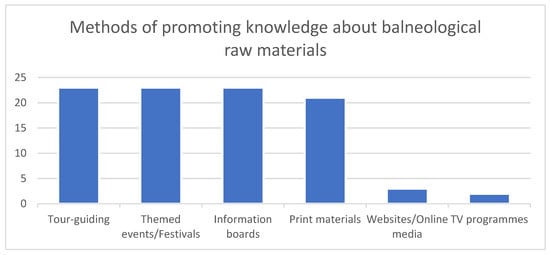

The second group of questions related to the need to promote knowledge about natural balneological resources. Respondents were asked how they would like to promote this knowledge, what the main sources of financing for promotional activities are, and what the greatest barriers to promotion are. Almost all surveyed spa towns see the need to promote knowledge about natural balneological resources (98%). The preferred forms of promotion include guide services, themed events, or festivals and information boards (23% each). Printed materials are also important (21%), while online promotion via websites and social media, as well as promotion on television, was shown to be the least preferred (3% and 2%, respectively; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Methods of promoting knowledge about natural balneological resources in the studied spa towns.

As can be seen, spa towns tend to use traditional forms of promotion (tour-guiding, festivals, information boards, print materials) rather than modern ones (websites, online media, or TV programmes). The authors are not surprised by these responses, as the primary target group for spa products and services is the elderly and retirees, with whom such promotional forms resonate best.

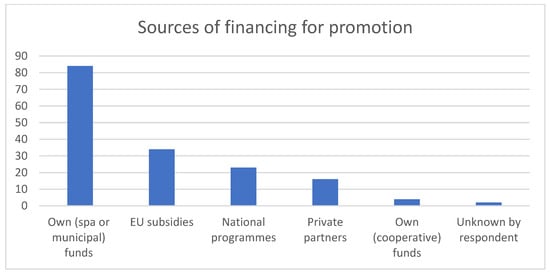

Regarding sources of financing for all promotional activities, respondents most often indicated the municipality’s/spa’s own funds (84%). EU grants were indicated by 34%, national programmes by 23%, private partners by 16%, and the company’s own funds by 4% (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sources used by spa towns to finance the promotion of natural balneological resources.

The chi-square test analysis reveals no clear correlation between forms of spa promotion and sources of financing (x2 = 6,26; p = 0.97).

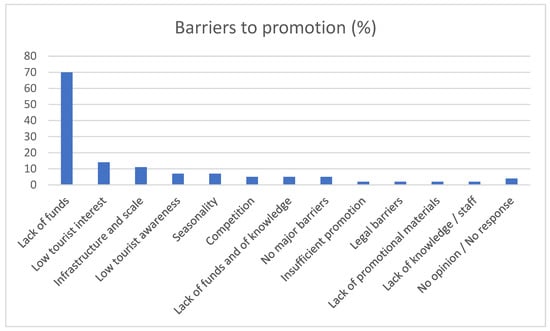

The most common barrier to promotion indicated by the surveyed group was mainly lack of funds (70%). Other barriers include low tourist interest (14%), infrastructure scale (11%), low tourist awareness and seasonality (7%), competition, lack of funds and lack of knowledge (5%), insufficient promotion, legal restrictions, lack of promotional materials, and lack of knowledge or staff (2%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Barriers that spas face when creating promotional marketing.

The chi-square test analysis reveals a clear correlation between spas’ barriers to marketing and their source of financing (x2 = 39, 39; p = 0.003). Lack of funding was the most frequently cited barrier, with these spas relying primarily on their own resources. To measure the strength of the relationship, Cramér’s V coefficient was used, which is 0.335. This value indicates a moderate strength of the relationship between types of barrier and types of financing.

The last group of questions concerned spa geoproducts and the availability of local souvenirs. Most of the respondents’ answers related to mineral-water-based products, i.e., mineral water pump rooms (57%) and bottled water (45%). Fifty-five percent of respondents listed cosmetics produced from local raw materials, and 36% listed brine or salt products and therapeutic treatments based on natural balneological materials. In three health spa resorts (7%), peat is also used as a product (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Balneological products offered by the surveyed spas.

Chi-square test analysis again reveals no clear correlation between products offered by spa towns and sources of financing (x2 = 17; p = 0.318). Cramér’s V coefficient indicates a weak relationship between these variables (V = 0.169).

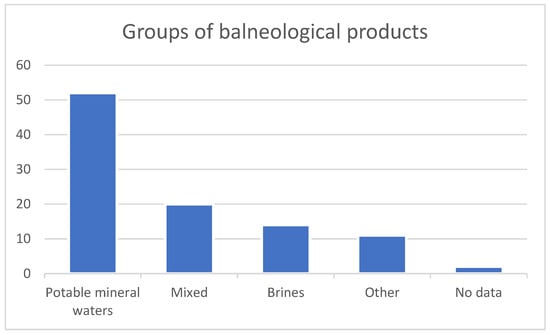

Fifty-two percent of the surveyed health spa resorts use only one balneological raw material, i.e., mineral water, and sell it in the health spa resort’s pump rooms and as bottled water. Twenty percent of spas offer a variety of products based on mineral water, brine, and mud. Fourteen percent are health spa resorts that specialise in brine-based products: brine graduation towers, inhalations, brine baths, and salt products. Eleven percent of the health spa resorts surveyed additionally indicated other offers related to thermal waters or recreation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Groups of balneological products offered by health spa resorts.

In the surveyed spas, 75% of responses regarding the sale of local souvenirs were positive. The respondents mainly indicated the presence of handicrafts, ceramics, wood products, glass, sculptures, paintings, salt- and brine-based products, jewellery, food products, honey and bee products, amber products, and cosmetics in the spa offer, but also magnets, clothes, and pens. Respondents also indicated an abundance of cheap products from outside the region (64% of respondents indicated this problem).

The last two questions concerned the cooperation of spa towns with scientific or educational institutions. Seventy-seven percent of the surveyed spas confirmed such cooperation. Spas mainly cooperate with universities, which also conduct scientific research on their premises. The respondents also expressed their desire to participate in the activities of the National GEO-PRODUKT Forum (86%).

Analysing Polish health spa resorts and their resources, nine products and services created using balneological raw materials stand out as being the most characteristic:

- Bottled waters (mineral and medicinal), both offered locally and circulated nationwide (currently, 47 types of bottled water trade names are available on the market);

- Mineral water drinking halls, which are located within spa towns, often in buildings with spa architecture, connected to spa parks and tourist infrastructure;

- Comestibles other than water, i.e., products based on rock salt or carbon dioxide from mineral waters (used, for example, in the food industry to carbonate drinks or in therapeutic baths);

- Graduation towers (including inhalation fountains) which are a specific facility combined with an outdoor inhalation service;

- Thermal, mineral, and thermal-mineral bathing pools (indoor and outdoor), as well as geothermal recreational complexes (also used for therapeutic and cosmetic treatments, heating, and wood drying);

- Cosmetic and body-care services and products, based on balneological raw materials, e.g., creams, balms, gels, soaps, shampoos, bath salts, oils, ointments, etc., offered on-site and sold nationwide;

- Medical services (therapeutic, rehabilitation, and preventive treatments) based on balneological raw materials provided within the spa areas (natural medicine facilities) and outside them, i.e., baths, compresses, inhalations, rinsing, washing, drinking cures, as well as medicinal products available on-site and nationwide, e.g., medicinal waters, medicinal salts and brines, sludges, pastes and lyes, medicinal muds, and others (e.g., green clays from Gąski, sulphur muds, and a group of sulphur medicines from Busko-Zdrój);

- Regional souvenirs made using or inspired by the local spa geoheritage, e.g., rock salt products;

- Informational and educational materials, i.e., information available in health spa resorts that explains, among other things, the origin of balneological resources and the influence of abiotic nature on the functioning of areas of value as health spa resorts (e.g., geoeducation using information boards).

All the products mentioned can be termed “geoproducts”, i.e., they are in accordance with the idea that was initiated by UNESCO and has been developed by many authors—products created with or inspired by geoheritage or geodiversity [12,14,15,16].

Additionally, there are other spa offers related to geoheritage, such as the following: trails, e.g., the Małopolska Mineral Water Trail (http://www.mineralnamalopolska.pl; accessed on 16 September 2025); events, e.g., the Mineral Water Festival in Muszyna; or larger designated spa areas, such as the Poprad, Podhale, Busko, Kłodzko, and Jelenia Góra regions [51]. For the Poprad region in the Carpathians, the creation of a mineral water geopark has been proposed [24]. A stay in a health spa resort can itself constitute a specific type of product, due to the use of health spa resort goods and services, due to the curative properties of the climate and landscape, and due to the experience of learning about the regional geoheritage.

5. Discussion

UNESCO Global Geoparks currently have the most experience in creating geoproducts [13,14,16,64]. A meta-analysis of these areas indicates that effective management relies, among other things, on supporting local cooperation, improving public education, building product brands, and strengthening institutional interactions [65]. The survey indicates that the greatest limitation for Polish spa municipalities is the lack of funding for such activities. On the other hand, most respondents declare that the funds they use are primarily local, which significantly limits investment in geoproducts. Addressing these funding issues will rely largely on creating sustainable financing mechanisms [66], supporting local producers [64], and involving local communities [67]. Researchers also point to the positive experience of national organisations supporting the protection and promotion of geoheritage [68]. Positive feedback from respondents to participating in the national “GEO-PRODUKT Forum” offers a promising new perspective. Other effective measures include combining local government financial policies with dedicated funds for geoconservation and geotourism, support from national geological surveys, and private enterprise investment in regional development [69].

It has been noted that the transfer of knowledge about balneological raw materials and their origins should constitute an important feature of geoproducts in health spa resorts; accordingly, respondents were asked about the current state of knowledge-promotion in health spa resorts. The data obtained show that most centres conduct such activities in a variety of forms. However, the wording in the question addressed “information about the origin of” balneological raw materials (genesis), and this may have been confused with “information about the product”. The authors’ observations show that geoheritage and its importance are rarely mentioned in health spa resort information materials; instead, the physicochemical characteristics of mineral waters and their impact on health are communicated.

Consumer awareness of pro-ecological and environmental activities will further support sustainable development [70]. For example, widespread understanding of the geoheritage values of spas may increase demand for local, sustainable products.

Despite various forms of promotion being used, they are notably traditional and do not involve innovative methods. This may have various reasons, but respondents certainly place financial and staffing problems among them. At the same time, almost all respondents expressed their desire to provide more information about geoheritage in health spa resorts. The preferred form seems to be services, such as tour guiding or promotional events. Meanwhile, research shows that digital promotion methods play a key role in attracting tourists to alternative forms of tourism, such as geotourism [71]. This is influenced by both the visual and substantive aspects of websites, as well as the engaging dissemination of information, such as newsletters, educational programmes, digital applications, and social media.

The topic of geoeducation in health spa resorts requires further research and more detailed analysis. There is great potential for the development of this issue, especially since the majority of respondents declared their desire to promote spa geoheritage and engage in the activities of the GEO-PRODUKT Forum. This is a national association of people and organisations involved in developing geotourism and promoting geoheritage in Poland.

In popular tourist locations, local souvenirs are often displaced by cheaper substitutes, sometimes of unknown origin and poor quality, which additionally damage the image of the region (e.g., [72,73]). The responses to the survey questions about local products sold in spas suggest a significant positive change in the trend of souvenirs being sold that are intended to showcase the region. Although cheap products of questionable origin are still present in health spa resorts, respondents indicate that a significant number of souvenirs are from local artists.

However, the local market may be difficult to define. For example, can glass products, which probably come from various glass factories (e.g., from Krosno), be considered souvenirs that are local to health spa resorts throughout the Carpathians? Ceramic products sold in some health spa resorts are also of questionable origin, as these towns do not have direct access to ceramic clays ([74], accessed on 16 September 2025).

Some of the spas also listed souvenirs such as magnets, clothes, and pens as local souvenirs. These types of products can be considered geoproducts when they are manufactured from local raw materials and relate to the geoheritage in areas with spas. So, these examples are also questionable. Survey respondents mentioned local food products, which, if created using geoheritage, can also be classed as geoproducts.

Good examples of geoproducts are souvenirs related to rock salt (if it is that which is used in the spa) or jewellery featuring amber, which is sold in seaside resorts. Cosmetics and medicinal products produced from natural and local balneological raw materials are also unique geoproducts.

6. Conclusions

Based on the surveys conducted and the review of spa offers, it can be stated that Polish spas, spa protection areas, and towns with special balneological resources have a high potential in terms of geoproducts based on balneological raw materials. As the survey showed, each analysed town offers at least two, but most often five or six, products based on balneological raw materials.

The surveyed spas also understand the need to promote knowledge about balneological raw materials and topics related to geoheritage. However, promotional mechanisms vary widely and depend primarily on the financial capabilities of the spas, which can be affected by difficulties in obtaining external funding. Most spas rely on their own resources to create promotional materials. Other barriers limiting promotional opportunities are a lack of knowledge or experience among staff and limited collaboration with scientific institutions.

It is encouraging that the surveyed localities try to promote geoheritage in a sustainable way using local geoproducts. However, this process is not guided by any explicit strategy; it takes place selectively, without supervision or certification. Local governments in spa towns also point to the problem of cheap souvenirs that are neither directly related to local heritage nor produced by local people.

A strong potential and willingness among local producers have been observed, but this is only the beginning of the path toward developing sustainable geoproducts. More extensive research in this area is necessary, as well as the promotion of the concept of geoheritage and the involvement of spa towns in the development of geotourism. This present study shows that two key barriers—the shortage of qualified professionals and the lack of knowledge about geoheritage (including its potential and promotional opportunities)—can be addressed through cooperation with the scientific community. One possible approach is to include local governments in the GEO-PRODUKT Forum. Periodic meetings between local government officials and spa town employees could, under the guidance of relevant experts, address these knowledge gaps while also establishing contacts with other municipalities to create joint packages promoting geoheritage in spa towns.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010066/s1, Supplementary File: Survey Form: Assessment of the Promotion of Geological Heritage in Polish Spa Resorts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; methodology, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; software, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; validation, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; formal analysis, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; investigation, A.C.-Ž., K.M., and P.K.; resources, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; data curation, A.C.-Ž., K.M., and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; writing—review and editing, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; visualisation, A.C.-Ž.; supervision, K.M.; project administration, A.C.-Ž. and K.M.; funding acquisition, A.C.-Ž. and K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from AGH University of Krakow 16.16.140.315 and the University of the National Education Commission Krakow Grants nos. WPBU/2024/03/00098 and WPBU/2025/02/00097.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the UKEN Rector’s Committee for Research Ethics due to Legal Regulations of the Rector’s Committee for Research Ethics at the University of the National Education Commission, Krakow (https://nauka.uken.krakow.pl/rektorska-komisja-ds-etyki-badan-naukowych/ accessed on 16 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all representatives of spa towns who participated in the survey. The authors are grateful to the reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wolski, J. Turystyka Zdrowotna a Uzdrowiska Europejskich Krajów Socjalistycznych; Polskie Towarzystwo Balneologii, Bioklimatologii i Medycyny Fizykalnej: Warszaw, Poland, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, J.N. Socialist Cuba: A Study of Health Tourism. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacchi, M. Sustaining tourism by managing health and sanitation conditions. In Proceedings of the XVII Inter-American Travel Congress, San José, Costa Rica, 10 April 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gaworecki, W. Turystyka (Tourism); Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.; King, B.; Milner, L. The health resort sector in Australia: A positioning study. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004, 10, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A. Turystyka uzdrowiskowa (Spa Tourism). In Study Materials; Scientific Publishing House of the University of Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dryglas, D. Rodzaje turystyki uzdrowiskowej i jej wpływ na realizację zadań promocji zdrowia. In Uzdrowiska i ich Funkcja Turystyczno-Lecznicza; Szromek, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Proksenia: Kraków, Poland, 2012; pp. 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Market.us Media. 2025. Available online: https://media.market.us (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Łoś, A. Turystyka zdrowotna—Jej formy i motywy: Czynniki rozwoju turystyki medycznej w Polsce. Econ. Probl. Relat. Serv. 2012, 84, 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E.; Brilha, J. Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 0470848952. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Geoparks Programme—A New Initiative to Promote a Global Network of Geoparks Safeguarding and Developing Selected Areas Having Significant Geological Features; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Geotourism for UNESCO Global Geoparks: A Toolkit for Developing and Managing Tourism; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Farsani, N.T.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C.; Carvalho, C.N. Geoparks and Geotourism: New Approaches to Sustainability for the 21st Century; Brown Walker Press: Irvine, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dryglas, D.; Miśkiewicz, K. Construction of the geotourism product structure on the example of Poland. In Proceedings of the 14th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference & EXPO SGEM2014, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; Volume 5, pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, J.; Neto de Carvalho, C.; Ramos, M.; Ramos, R.; Vinagre, A.; Vinagre, H. Geoproducts—Innovative development strategies in UNESCO Geoparks: Concept, implementation methodology, and case studies from Naturtejo Global Geopark, Portugal. Int. J. Geoheritage Park. 2021, 9, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, K. Geotourism Product as an Indicator for Sustainable Development in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, A.; Ugolini, F.; Pearlmutter, D.; Raschi, A. Thermal Tourism and Geoheritage: Examining Visitor Motivations and Perceptions. Resources 2020, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Chrobak, A.; Pearlmutter, D.; Raschi, A. Examining the tourism value of geological landscape features: The case of Terme San Giovanni in the Siena clay lands of Tuscany. Acta Geoturistica 2016, 7, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chrobak, A. Analiza i Ocena Potencjału Geoturystycznego Podtatrza; praca dokt; Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny w Krakowie, Instytut Geografii: Kraków, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chrobak, A.; Bąk, K. Poznawczo-Edukacyjne Aspekty Atrakcji Geoturystycznych Podtatrza; Wydawnictwo Naukowe UP: Kraków, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jamorska, I. The significance of therapeutic waters of Swoszowice, Krzeszowice and Mateczny in the development of spa tourism. Geotourism/Geoturystyka 2008, 4, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawiec, A.; Jamorska, I. Ciechocinek Spa—The Biggest Health Resort in the Polish Lowlands in Terms of Geotourism. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, K.; Golonka, J.; Waśkowska, A.; Doktor, M.; Słomka, T. Transgraniczny geopark Karpaty fliszowe i ich wody mineralne. Przegląd Geol. 2011, 59, 611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Bubniak, M.; Solecki, T. Przewodnik Geoturystyczny po Szlaku Geo-Karpaty; Wydawnictwo RUTHENUS: Krosno, Poland, 2013; ISBN 9788375302202. [Google Scholar]

- Chowaniec, J.; Zuber, A. Touristic geoattractions of Polish Spas. Przegląd Geol. 2008, 56, 706–710. [Google Scholar]

- Golonka, J.; Waśkowska, A.; Doktor, M.; Krobicki, M.; Słomka, T. The geotourist attractions in the vicinity of Szczawnica spa. Geotourism 2014, 37, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wasiluk, R.; Radwanek-Bąk, B.; Bąk, B.; Kopciowski, R.; Malata, T.; Kochman, A.; Świąder, A. A conception of a mountain geopark in a SPA region; example of a projected Geopark „Wisłok Valley—The Polish Texas”, in the Krosno region. Geotourism 2016, 46–47, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryglas, D. Designing a Health Tourism Product Structure Model in the Process of Marketing Management; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dryglas, D.; Różycki, P. Profile of tourists visiting European spa resorts: A case study of Poland. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2017, 9, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryglas, D.; Salamaga, M. Therapeutic Landscape as Value Added in the Structure of the Destination-Specific Therapeutic Tourism Product: The Case Study of Polish Spa Resorts. Tour. An Int. Interdiscip. J. 2023, 71, 782–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawiec, A. Therapeutic waters as geotourism values of the Polish Baltic sea coast. Geoturystyka 2012, 28–29, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zglinicki, K.; Szamałek, K. Kopaliny balneologiczne jako surowiec kluczowy. Przegląd Geol. 2021, 69, 218–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dryglas, D. Spa and wellness tourism as a spatially determined product of health resorts in Poland. Curr. Issues Tour. Res. 2012, 2, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Zdrowia. Rejestr Uzdrowisk i Obszarów Ochrony Uzdrowiskowej Wraz z Kierunkami Leczniczymi. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/rejestr-uzdrowisk-i-obszarow-ochrony-uzdrowiskowej-wraz-z-kierunkami-leczniczymi (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Miśkiewicz, K.; Poros, M. Ogólnopolskie Forum GEO-PRODUKT: Projekt integracji działań z zakresu udostępnienia i promocji dziedzictwa geologicznego Polski. Przegląd Geol. 2022, 70, 568–570. [Google Scholar]

- Świdziński, H. Zagadnienia Geologiczne Wód Mineralnych w Szczególności na Niżu Polskim iw Karpatach; Materiały pozjazdowe NOT w Krynicy: Katowice, Poland, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Kolago, C. Geologiczne regiony wód mineralnych Polski. Przegląd Geol. 1957, 5, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Agopsowicz, T.; Pazdro, Z. Zasolenie wód kredowych na Niżu Polskim. Zesz. Nauk. PGd Bud. Wod. 1964, 49, 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dowgiałło, J. Występowanie wód leczniczych w Polsce. In Geologia Surowców Balneologicznych; Dowgiałło, J., Karski, A., Potocki, L., Eds.; Wydawnictwa Geologiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 1969; pp. 143–211. [Google Scholar]

- Dowgiałło, J. Studium genezy wód zmineralizowanych w utworach mezozoicznych Polski północnej. Biul. Geol. Wydz. Geol. UW 1971, 13, 133–224. [Google Scholar]

- Paczyński, B.; Pałys, J. Geneza i paleohydrogeologiczne warunki występowania wód zmineralizowanych na Niżu Polskim. Kwart. Geol. 1970, 14, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bojarski, L. Solanki paleozoiku i mezozoiku w syneklizie perybaltyckiej. Pr. Inst. Geol. 1978, 88, 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Paczyński, B.; Płochniewski, Z. Wody Mineralne i Lecznicze Polski; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bojarski, L. Atlas Hydrochemiczny i Hydrodynamiczny Paleozoiku i Mezozoiku oraz Ascenzyjnego Zasolenia wód Podziemnych na Niżu Polskim, 1:1 000 0000; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dowgiałło, J.; Paczyński, B. Podział regionalny wód leczniczych Polski Poradnik metodyczny. In Ocena Zasobów Dyspozycyjnych wód Potencjalnie Leczniczych. Poradnik Metodyczny; Paczyński, B., Ed.; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2002; pp. 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dowgiałło, J. Przegląd regionalny wód zmineralizowanych, termalnych oraz uznanych za lecznicze. In Hydrogeologia Regionalna Polski. T II: Wody Mineralne, Lecznicze oraz Kopalniane; Paczyński, B., Sadurski, A., Eds.; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2007; pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova, S.V.; Gorbatschev, R.; Garetsky, R.G. The East European Craton. In Encyclopedia of Geology; Selley, R.C., Cocks, L.R., Plimer, I.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Żelaźniewicz, A.; Aleksandrowski, P.; Buła, Z.; Karnkowski, P.H.; Konon, A.; Oszczypko, N.; Ślączka, A.; Żaba, J.; Żytko, K. Regionalizacja Tektoniczna Polski (Tectonic Subdivision of Poland); Komitet Nauk Geologicznych PAN: Wrocław, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki, J.; Becker, A. Geological Atlas of Poland; Polish Geological Institute: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Felter, A.; Filippovits, E.; Gryszkiewicz, I.; Lasek-Woroszkiewicz, D.; Skrzypczyk, L.; Socha, M.; Sokołowski, J.; Sosnowska, M.; Stożek, J. Mapa Zagospodarowania wód Podziemnych Zaliczonych do Kopalin w Polsce; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Różycka, M.; Migoń, P. Tectonic geomorphology of the Sudetes (Central Europe)—A review and re-appraisal. Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 2017, 87, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poprawa, D.; Nemčok, J. Geological Atlas of the Western Outer Carpathians and Their Foreland, 1:500,000; Polish Geological Institute: Warszawa-Łódż, Poland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rajchel, L.; Rajchel, J. Karpackie źródła wód mineralnych i specyficznych-pomnikami przyrody nieożywionej. Przegląd Geol. 1999, 47, 911–913. [Google Scholar]

- Rajchel, L. Występowanie, chemizm oraz geneza szczaw i wód kwasowęglowych Karpat Polskich. Biul. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 2013, 456, 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- Dowgiałło, J. Poligenetyczny model karpackich wód chlorkowych i niektóre jego konsekwencje. In Współczesne Problemy Hydrogeologii Regionalnej; Wydawnictwa Geologiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 1980; pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Chowaniec, J.; Poprawa, D.; Witek, K. Wystepowanie wód termalnych w polskiej części Karpat. Przegląd Geol. 2001, 49, 734–742. [Google Scholar]

- Chowaniec, J.; Freiwald, P.; Operacz, T. Różnorodność wód podziemnych województwa małopolskiego i ich wykorzystanie/The diversity of the Małopolskie voivodeship groundwaters and their usage. Ann. UMCS Geogr. Geol. Mineral. Petrogr. 2012, 67, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kępińska, B. Znaczenie badań podhalańskiego systemu geotermalnego dla eksploatacji wód geotermalnych. Geoterm. Zrównoważony Rozw. 2009, 2, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Łajczak, A. Torfowiska Kotliny Orawsko-Nowotarskiej. Rozwój, Antropogeniczna Degradacja, Renaturyzacja i Wybrane Problemy Ochrony; Instytut Botaniki im. W. Szafera, Polska Akademia Nauk: Kraków, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lipka, K.; Kosiński, K. Torfowiska w okolicy Czarnego Dunajca na tle sieci hydrograficznej. In Sesja Naukowa “Melioracje Terenów Górskich a Ochrona Srodowiska”; Akademia Rolnicza: Kraków, Poland, 1993; pp. 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Lipka, K.; Zając, E. Peatbogs in the Orawa-Nowy Targ Basin. Acta Hortic. Regiotect.—Mimoriadne Cislo 2003, 6, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Niezabitkowski-Lubicz, E. Wysokie torfowiska Podhala i konieczność ich ochrony. Ochr. Przyr. 1922, 3, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- El Hamidy, M.; Errami, E.; Neto de Carvalho, C.; Rodrigues, J. Innovative Geoproduct Development for Sustainable Tourism: The Case of the Safi Geopark Project (Marrakesh–Safi Region, Morocco). Sustainability 2025, 17, 6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdowsi, S.; Németh, K. Geoparks Management in Tourism Destinations: Integrating Development and Conservation. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, V.; Jaswal, A.; Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R.; Agarwal, N. Sustainable Financing for ESG Practices. In Sustainable Energy Transition; Circular, E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffelen, A. Where is the community in geoparks? A systematic literature review and call for attention to the societal embedding of geoparks. Area 2020, 52, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megerle, H.E.; Ellger, C. Germany’s UNESCO Global Geoparks and National GeoParks: Experiences from a Two-Tier System. Land 2023, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wu, W. Geoparks and Geotourism in China: A Sustainable Approach to Geoheritage Conservation and Local Development—A Review. Land 2022, 11, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B. Sustainability Assessment of Geotourism Consumption Based on Energy–Water–Waste–Economic Nexus: Evidence from Zhangye Danxia National Geopark. Land 2024, 13, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthakis, M.; Simatou, A.; Antonopoulos, N.; Kanavos, A.; Mzlonas, N. Alternative Forms of Tourism: A Comparative Study of Website Effectiveness in Promoting UNESCO Global Geoparks and International Dark Sky Parks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.C.L.; Mosquera, D.S. Souvenirs and Territorial Representations: A Case Study in Santiago de Compostela. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2012, 3, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Nainggolan, H.; Tamba, O.; Sihotang, D.; Sinaga, T. Souvenir Traders and Their Impact on Cultural Tourism and Economic Development. J. Ilmu Pendidik. Dan Hum. 2022, 11, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maps 2025. Mapa Rozmieszczenia złóż Surowców Ceramicznych i Ogniotrwałych. Polish Geological Institute—National Research Insitute, Warszawa. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/surowce/mapy#scbcb-2024 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.