Abstract

Cross-border e-commerce logistics has long prioritized delivery speed; however, the trade-offs between cost-effectiveness, carbon emissions, risk, and financial performance have received relatively little attention. To address this deficiency, this study constructs a fuzzy nonlinear multi-objective optimization framework that integrates the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm and the Sobol sensitivity analysis to capture the uncertainty and nonlinear dynamics of logistics systems. Using operational data from a Taiwanese cross-border e-commerce exporter from 2023 to 2024, empirical results show that extending the standard 25-day delivery time to an acceptable maximum of 32–37 days (i.e., an extension of 7–12 days) can reduce logistics costs per order by 22–38%, carbon emissions by 18–31%, and increase financial returns. Sobol sensitivity analysis further demonstrates that extended delivery time (T) is a significant controllable factor (). This study empirically verifies the profitability and sustainability of moderately T, challenges the current “speed-first” model, and provides a transparent, replicable, and scalable decision-making framework for promoting low-carbon, economically viable cross-border e-commerce supply chains.

1. Introduction

Cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) logistics plays a vital role in international trade. Differences in regional development stages and consumer demand for fast delivery create significant risks and environmental impacts [1]. Consumers continue to value speed over sustainability, with 55% preferring faster delivery methods [2]. Expedited logistics delivery increases carbon emissions [3]. Developed economies reduce emissions by 5.5% through industrial upgrading [4], while developing economies reduce emissions by 7.2% through infrastructure expansion [5]. Effectively addressing evolving customer needs and creating value through multiple stakeholders are ways to reduce carbon emissions [6], and consumers are one of the main factors influencing these outcomes. Time management, cost control, and quality control emerge as key levers for reducing emissions [7]. The research uses machine learning to optimize order consolidation and capacity allocation [8], but longer cycles increase cancellation rates and threaten profitability [9]. Delivery speed directly shapes cost structures and risks, with extended time raising inventory and foreign exchange exposure for SMEs [10]. Balancing delivery service level index (DSLI) with time-sensitive financial indicators remains a core challenge for CBEC logistics.

Sustainable CBEC logistics requires balancing DSLI risk, logistics costs, delivery time, carbon emissions, and financial benefits. Traditional linear models fail to capture these complexities, as logistics systems operate as fuzzy, nonlinear phenomena influenced by multiple uncertain factors. Existing fuzzy nonlinear models demonstrate potential: extending delivery time reduces emissions without harming service quality [7]; fuzzy goal programming optimizes delivery time, cost, and efficiency under uncertainty [11]; nonlinear fuzzy membership functions balance environmental and financial goals [12]. However, current research on fuzzy multi-objective optimization primarily identifies optimal solutions without analyzing how decision variables contribute to system performance. This limitation leaves decision-makers uncertain about which controllable factors deserve priority, restricting effective resource allocation.

This study bridges a critical gap in logistics research by introducing a hybrid decision-making framework that advances CBEC logistics planning. It integrates Sobol sensitivity analysis [13] and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm into a fuzzy nonlinear multi-objective model to effectively capture system uncertainties. Substantively, the findings reveal that moderating delivery speed is not merely a compromise but a strategic tool that unlocks high cost and carbon savings while stabilizing financial returns. This framework enables decision-makers to prioritize operational interventions based on precise variable hierarchies rather than relying on intuition.

With these insights as a foundation, the remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 conducts a comprehensive literature review on CBEC logistics, analyzing risk management, cost optimization, carbon emission reduction, and financial performance, and delineating the research gaps that justify the present investigation. Section 3 develops the methodological framework, explicating the integration of fuzzy nonlinear multi-objective programming (FNMOP) model, the PSO algorithm, and Sobol sensitivity analysis, while specifying the formulation of objective functions, membership functions, and constraint-handling mechanisms. Section 4 presents the empirical case study, reports the optimization outcomes generated through PSO, and quantifies the relative importance of decision variables using Sobol sensitivity analysis. This section also conducts a comparative evaluation against alternative algorithms to establish methodological robustness. Section 5 interprets the managerial implications, highlights methodological innovations, and articulates the theoretical contributions of the study, situating the results within the broader discourse on sustainable logistics. Section 6 synthesizes the principal findings, identifies limitations arising from model assumptions and data constraints, and proposes future research directions that aim to extend the framework’s applicability across diverse e-commerce contexts and geographic markets.

2. Literature Review

CBEC enhances efficiency and flexibility in international trade but introduces complex logistics trade-offs involving risk, cost, time, carbon emissions, and financial benefits. Logistics risk is a critical challenge in CBEC. Giuffrida, Jiang, and Mangiaracina (2021) [14] investigated how Chinese CBEC firms manage logistical uncertainties through tailored risk management strategies. The study used structural equation modeling (SEM) based on a survey of online exporters and third-party freight logistics providers (3PFLs) to analyze relationships between uncertainty types and risk responses. The findings show that firms adapt their approaches based on specific logistics uncertainties, with industry context playing a secondary role in systematically identifying and assessing logistics risks.

Similarly, Shan et al. (2021) [15] combined Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) with the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) to evaluate risks in express delivery services. Among 18 service failures, the six highest-risk issues were package loss, rough handling, sorting errors, privacy leakage, unauthorized delivery, and poor service attitude. Lower-risk issues included extended shipments, lack of due diligence, inconsistent rates, service acceptance errors, missed handovers, and poor network coverage. The study emphasizes the need for remedial measures to address high-risk failures, reduce operational losses, and enhance resilience.

Merkert, Bliemer, and Fayyaz (2022) [16] conducted a logit analysis of 709 urban Australian residents to explore preferences for traditional posties, parcel lockers, and drone deliveries. The results indicate a preference for conventional posties, but drones become competitive if they offer faster and cheaper services. Parcel lockers gain attractiveness when safe parcel drop-off locations are unavailable, reducing theft risks. Gruchmann, Maugeri, and Wagner (2025) [17] explored green nudging strategies that leverage consumer guilt to promote sustainable last-mile delivery choices. The study found that highlighting the environmental impact of fast deliveries through guilt-based nudging significantly increased consumer willingness to accept extended delivery time (T), reducing carbon emissions and logistics costs while maintaining satisfaction.

Nie (2022) [18] used the ELECTRE (Elimination Choice Translating Reality) method to develop a multi-attribute decision-making model for selecting transportation modes based on type, volume, distance, time, cost, safety, and service level. This approach helps enterprises choose cost-effective, safe, and low-carbon logistics methods.

Similarly, Pokrovskaya et al. (2019) [19] employed system analysis, scientific literature, archival, statistical, and comparative methods to mitigate logistics risks and reduce costs associated with accurate delivery.

Liao (2025) [20] addressed sales prediction challenges in CBEC using a fuzzy logic multi-criteria (FLMC) algorithm. This algorithm leverages fuzzy logic to handle imprecision and ambiguity, improving decision-making and operational efficiency in unpredictable environments.

Gong (2024) [21] proposed a fuzzy logic-based framework for optimizing resource allocation in CBEC supply chains, validated through root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) metrics, enhancing efficiency and profitability in dynamic settings.

Oteri et al. (2023) [22] found that integrating data analysis, automation, and lean management principles optimizes inventory, transportation, and warehousing while maintaining service quality, balancing short-term savings with long-term sustainability.

Zhang et al. (2023) [23] identified customer requirements, sustainable business value, environmental legitimacy, and competitive pressure as key drivers of carbon neutrality in CBEC. Influenced by external stakeholders (customers, competitors) and internal forces (shareholders, managers), these factors encourage low-carbon transformations that yield long-term economic benefits.

Huang et al. (2024) [24] applied horizontal transshipment with enhanced algorithms to optimize split-order distribution and reduce costs and time, while Derpich et al. (2024) [25] examined multi-modal transport to lower costs and CO2 emissions.

Golpîra and Javanmardan (2022) [26] developed a robust optimization model for sustainable closed-loop supply chains, incorporating carbon emission schemes to balance cost efficiency and environmental sustainability. These studies underscore the need to integrate cost reduction with carbon emission strategies for sustainable logistics. Financial benefits drive CBEC logistics strategies.

Iвaнoвa et al. (2021) [27] proposed using the stability of the “ratio of operating results to logistics costs” as an indicator of logistics chain efficiency, employing vector cointegration to analyze long-term equilibrium relationships.

Chen and Liu (2025) [28] examined the financial impact of tariffs on freight costs, finding that free delivery is optimal under low tariffs but becomes unsustainable as tariffs rise, prompting exporters to adopt slower logistics to optimize profits. Risk-oriented extended delivery strategies can simultaneously achieve cost control, carbon emission reduction, and long-term financial benefits. Extending transportation time within acceptable customer ranges reduces errors and risks from rushed deliveries, saving costs and energy while avoiding emissions from redeliveries.

Based on the findings of the above related studies, it is necessary to enable enterprises to maintain flexible, low-risk, and sustainable logistics systems in a turbulent market and enhance financial competitiveness through stable income and carbon emission reduction. CBEC logistics must face risk identification, cost optimization, sustainability, and economic benefits. From a management perspective, risk management and error mitigation can enhance operational resilience. From an operational standpoint, cost-effective decisions can cope with uncertainty and complexity. How can short-term cost savings be balanced with long-term environmental goals under sustainable development measures? Can extending delivery time reduce errors, financial losses, costs, and carbon emissions, thereby improving profitability?

Drawing on the methodologies identified in the literature review, this study introduces a critical innovation: a fuzzy, nonlinear, multi-objective optimization framework that integrates the PSO algorithm to combine Sobol sensitivity analysis [29]. This hybrid approach actively addresses and navigates the complexity and uncertainty inherent in CBEC logistics.

First, to address optimization challenges, this study employs PSO [30]. Traditional linear models often fail to capture the fuzziness and nonlinear characteristics of logistics systems. As highlighted by Wang and Wang (2024) [31] and Mirsadeghi (2021) [32], PSO demonstrates exceptional robustness in handling continuous variables under high uncertainty. Moreover, PSO provides rapid convergence and effective exploration of complex solution spaces, making it particularly well-suited for evaluating trade-offs among cost, time, carbon emissions, and financial returns.

Second, to ensure analytical precision, this study incorporates Sobol sensitivity analysis, utilizing the methodology proposed by [33]. By calculating Sobol indices through Monte Carlo simulations, this approach overcomes the input limitations of structured models. Implemented in Python 3.9, it provides a precise and stable assessment of variable influence, thereby enhancing the overall reliability of the decision-making framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Framework and Hypotheses

This study develops a framework that systematically reveals the interrelationships within CBEC logistics, with sustainability as the overarching objective. The framework examines how logistics operations impact delivery times, influencing cost parameters and financial performance. Longer delivery windows mitigate the risks and costs associated with urgent deliveries, thereby reducing carbon emissions and supporting sustainable development.

Figure 1 presents the research framework illustrating how extended delivery time (T) affects cost, risk, carbon emissions, and financial benefit in CBEC logistics, optimized through PSO and Sobol sensitivity analysis. These methods create a measurable decision-support tool that helps businesses weigh their options, set priorities, and use their resources wisely. Building on this foundation, the study proposes four related hypotheses (H) to guide empirical validation.

Figure 1.

Proposed research framework.

H1.

Extended delivery time (T) is inversely related to total logistics cost.

H2.

T is inversely related to total carbon emissions.

H3.

T has a nonlinear relationship with risk.

H4.

A successful trade-off exists that can maximize the net financial benefit while remaining within customer-acceptable time limits.

3.2. Project Methodology

The application steps for PSO and Sobol sensitivity analysis in the CBEC logistics system are outlined as follows: 1. Model the problem in the CBEC logistics system as a multi-objective optimization problem. Delivery time window: extend the delivery time to provide greater flexibility. Objective: minimize transportation costs, maximize DSLI, and ensure the goods are delivered to the right place and consignee. Minimize carbon emissions: reduce greenhouse gas emissions during transportation. Maximize profit: achieve revenue by reducing costs and improving efficiency. Constraints: delivery time window (extended time range).

In the PSO algorithm, each particle represents a possible logistics solution. The specific design steps of PSO are as follows: Initialize particle swarm, randomly generate a set of particles, and each particle contains a delivery schedule (considering the flexibility of T). Calculate the initial Fitness for each particle, based on a weighted combination of DSLI, cost, carbon emissions, and profit.

The fitness function needs to balance multiple objectives:

: The calculated fitness value for particle i at its current position at time t. The goal of PSO is to find a particle position that minimizes this value.

: The total logistics cost incurred by the solution represented.

: The DSLI of the solution risk. Multi-objective optimization wants to maximize accuracy, which is equivalent to minimizing inaccuracy. The A(T) function (DSLI) is employed as a component of the overall financial benefit to reflect the nonlinear market perception of delivery service quality relative to the T. While the functional form A(T) is quadratic, it is designed to represent a relative composite index of service level, rather than a probability or rate. Therefore, values exceeding 1 should be interpreted as exceeding the baseline service level benchmark, not as a mathematical probability error. This study explicitly ensures that the contribution of A(T) to the financial benefit is capped to avoid unrealistic overestimation of the revenue impact.

: The carbon emissions solution.

: The financial profit or benefit generated.

Since multi-objective optimization minimizes the overall fitness, a higher economic benefit should lead to a lower re-delivery value.

, , , : Weighting factors for each objective. These are positive real numbers that reflect the relative importance of each objective. Their sum may or may not be 1, depending on your normalization strategy for the individual objective values.

The movement of each particle in the swarm is governed by standard PSO velocity and position update equations, which balance individual exploration (cognitive term) and collective exploitation (social term). In this study, the particle position directly represents the single decision variable, ∈ [1,12] days, making the search space one-dimensional and the problem highly constrained. The fitness function evaluates the aggregated membership degree (Section 3.3.4), incorporating fuzzy nonlinear objectives for cost, carbon emissions, risk, and financial benefit. A reflective boundary handling mechanism ensures that any particle attempting to exceed the acceptable time range [1,12] is immediately reflected back into the feasible region, maintaining solution validity throughout the optimization process.

The equation determines the new velocity of particle in the iteration. It consists of three parts: an inertial term that ensures the particle retains some of its old direction and velocity, maintaining its wide-area exploration capability; a cognitive term that drives the particle toward its own found optimal position , representing individual experience; and a social term that drives the particle toward the group’s found optimal position , representing group learning. Here, and are random numbers between [0, 1] to increase the randomness of the search.

: The new velocity of particle in dimension at time .

(Inertia Weight): A scalar factor that determines the influence of the particle’s previous velocity on its current velocity. A higher encourages global exploration, while a lower encourages local exploitation.

(Cognitive Learning Factor): A scalar factor that determines how much the particle is influenced by its own personal best-found position (pBest).

A random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1, used to introduce stochasticity.

: Particle i’s best position in dimension up to time . This is the position that yielded the best fitness value for particle itself historically.

: The current position of particle in dimension at time .

(Social Learning Factor): A scalar factor that determines how much the particle is influenced by the global best-found position (gBest).

: Another random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1, independent of r1.

: The best position found by any particle in the entire swarm in dimension d up to time t.

Equation (3) applies the calculated new velocity to particle at current position in the iteration, thus determining its new position in the iteration. This new position represents the potential solution after one iteration of optimization.

: The new velocity calculated from the velocity update equation.

This iterative process continues until a predefined maximum number of iterations or a satisfactory fitness level is reached.

T allows more flexible path planning and vehicle scheduling, reducing the need for emergency delivery, thereby reducing the risk and cost of redistribution. It can also reduce carbon emissions by integrating multiple orders and reducing empty miles.

The PSO [34,35] algorithm is utilized in this study to efficiently solve the nonlinear multi-objective optimization problem under a fuzzy framework. PSO is favored for its simplicity, fast convergence, and robustness in navigating complex search spaces compared to other metaheuristics.

The standard velocity and position update equations are employed, which guide particles based on their historical best position () and the global best position (). The key parameters governing the search process are specifically tailored for our CBEC logistics problem:

- Inertia Weight Schedule: A Linearly Decreasing Inertia Weight (w) strategy is implemented, starting from and linearly decreasing to . This approach guarantees sufficient global exploration in the initial stages and accelerates local exploitation toward the end of the search.

- Acceleration Coefficients: The cognitive () and social () coefficients are both set to 2.0 to equally balance the particle’s tendency to follow its own experience and the swarm’s collective intelligence.

- Constraint Handling: Since the decision variable, T, is subject to a rigid constraint ( days), a Reflective Boundary Handling mechanism is employed. Any particle attempting to move outside the acceptable time range is immediately reflected into the feasible search space.

3.3. Integration of Fuzzy Set into the Multi-Objective Model

Although real-world CBEC logistics parameters (demand fluctuation, consumer tolerance for delayed delivery, carbon emission factors under different weather/customs conditions, and unit transportation cost under fuel-price volatility) exhibit significant uncertainty and ambiguity, they cannot be adequately captured by stochastic distributions alone. Following Chiang (2024) [7], Gupta et al. (2021) [11], and Miah et al. (2023) [12], this study therefore transforms the original crisp multi-objective problem into an FNMOP model using triangular fuzzy numbers and nonlinear membership functions.

3.3.1. Selection of Fuzzy Parameters and Triangular Membership Functions

Three key parameters are treated as triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs) based on data from the case company (SASSWOOD, Taipei City, Taiwan) and forwarder quotations (2023–2024). Triangular membership functions were selected for their ease of elicitation from logistics managers and computational simplicity, consistent with prior applied research [12].

This study converts the model from a deterministic structure to a multivariate fuzzy framework to tackle the issue of the structural dependence of total cost and total carbon emissions on T in Sobol sensitivity analysis. Rather than using total and as Sobol inputs, this study introduces two exogenous, structurally independent fuzzy factors to encapsulate uncertainty shocks in the supply chain that a single variable cannot adequately elucidate. Guarantees the fulfillment of the independent assumption of input variables necessary for analysis.

Cost–benefit uncertainty parameter (): Represents the magnitude of cost variation in logistics costs caused by process optimization or market fluctuations.

Carbon emission optimization uncertainty parameter (): Represents the magnitude of emission variation in total carbon emissions caused by the adoption of low-carbon technologies. The specific values and settings for these parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Triangular fuzzy parameters and their membership function settings used in the FNMOP model.

3.3.2. Fuzzy Objective Functions

The four original crisp objectives are rewritten in fuzzy form:

where DSLI(T) is the Delivery Service Level Index (a composite performance indicator, not a probability), and (1 − DSLI(T)) approximates the relative error rate compared to baseline. Clarification on A(T) formulation: In the optimization model, A(T) is included in the fitness function (Equation 1) as (1 − A(T)) to represent the expected loss due to service degradation. Since A(T) is an index (not bounded to [0, 1]), the model interprets: −A(T) = 1.0: Baseline service level (25-day standard) − A(T) > 1.0: Improved service (lower error rate due to less rush) − A(T) < 1.0: Degraded service. This formulation allows the model to quantify the risk-reduction benefits of T while maintaining mathematical consistency with the other objectives.

DSLI/Time Constraint: DSLI is primarily governed by the customer-acceptable range for T, which is treated as a Hard Boundary Constraint ) on the decision variable. Because it is controlled via the boundary mechanism, it is not listed as a separate, continuously optimized objective function, which maintains the conciseness and solvability of the multi-objective model.

3.3.3. Nonlinear Membership Functions for Each Objective

Following Miah et al. (2023) [12], defined continuous nonlinear membership functions that reflect diminishing marginal returns and decision-maker risk preference:

where αi are shape parameters calibrated from managerial interviews (α1 = 0.012, α2 = 0.018, α3 = 0.025, α4 = 0.008).

3.3.4. Aggregated Fuzzy Decision-Making (Max-Additive Operator)

The fuzzy multi-objective problem is converted into a crisp single-objective problem by maximising the aggregated membership degree:

Weights wj are determined by the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) with the case company’s logistics director ().

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) allocated objective weights methodically to ensure that each target’s priority was consistently evaluated. The team created a matrix to compare couples, utilizing both the standard AHP method and Saaty’s 1–9 scale. Because they had been in charge for over 10 years, management was able to make sound decisions. To ensure that the compared ratings were genuine, the matrix underwent a consistency test. The result yielded a Consistency Ratio (CR) of 0.07. AHP involved systematically changing each weight by ±20% and proportionately adjusting the other weights. Despite significant diversity in individual weights, the optimal delivery extension time differed by only 15% [37]. The optimization results are sufficient to handle minor fluctuations in weight. This careful method assigns weights based on the information available to the person making the decision. AHP maintains the stability and long-term validity of the weights, providing a solid, provable foundation for future optimization assessments.

3.3.5. Solution by Particle Swarm Optimization in the Fuzzy Environment

The particle position Xi now represents the T. The fitness function of each particle is exactly the aggregated satisfaction degree λ computed above (after defuzzifying the fuzzy objectives using the centroid of the resulting fuzzy solution set when needed). The standard PSO velocity and position updates (Equations (2) and (3)) remain unchanged, but the fitness evaluation loop now incorporates fuzzy arithmetic and nonlinear membership functions.

3.3.6. Defuzzification of the Final Set

After PSO terminates, the non-dominated solutions still contain fuzzy objective values. This study fuzzified them using the widely accepted center-of-gravity (COG) method to obtain crisp values for reporting and Sobol sensitivity analysis. By explicitly incorporating triangular fuzzy parameters, nonlinear membership functions, and a fuzzy aggregation operator, the model accurately reflects the ambiguity and non-compensatory preferences inherent in real-world CBEC logistics decision-making, representing a significant advancement over the crisp linear or simplified relations commonly used in most existing studies.

4. Sample Problem and Results

This study implements a fuzzy nonlinear multi-objective optimization framework that integrates PSO with Sobol sensitivity analysis to balance critical objectives in CBEC logistics effectively. Derived through multi-objective trade-off analysis, these objectives aim to achieve sustainable and financially robust logistics operations.

4.1. Project Introduction

This study focuses on the CBEC operations of SASSWOOD Corporation (founded 2003, Taipei, Taiwan), a small-to-medium enterprise (SME) specializing in cross-border distribution of toilet urinal anti-clogging filters to cleaning management companies in major North American cities (primarily New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Toronto). The company processes approximately 1200–1500 orders monthly, with an average order size of 15–20 units per shipment.

Baseline Delivery Policy and Customer Tolerance: SASSWOOD’s standard delivery commitment is 25 days from the date of order placement to final delivery. Customer tolerance for extended delivery was assessed through an internal survey conducted in 2023–2024 (n = 487 B2B customers, 68% response rate), which revealed that 82% of respondents would accept delays of up to 7 days without penalty, and 61% would tolerate delays of up to 12 days if informed proactively. These findings established the acceptable extension range of T ∈ [1, 12] days (i.e., 26–37 days total delivery time) used in the optimization model.

Data Sources and Parameterization: Key model parameters were derived from three proprietary data sources: (1) Shipment cost structure (2023–2024): Freight forwarder quotations and consolidation rate cards (confidential commercial contracts with DHL). (2) Carbon emission factors: Forwarder-provided CO2 audits per kg-km (aligned with GHG Protocol Scope 3 Category 4 guidelines). (3) Error rates and re-delivery costs: SASSWOOD’s internal logistics database (2023–2024), tracking mis-deliveries, address errors, and associated rectification expenses. Due to non-disclosure agreements with freight partners and competitive sensitivity, precise cost coefficients and contractual terms cannot be publicly disclosed; however, relevant information may be provided upon request in a confidential manner. However, the ranges presented in Table 2 (e.g., USD 10–40 per order, 0.5–2.5 kg CO2 per package) accurately reflect observed operational realities and are consistent with published industry benchmarks [1,7]. Table 2 summarizes the key empirical inputs used in the model.

Table 2.

Empirical parameter ranges and definitions for SASSWOOD Corporation’s CBEC logistics optimization (2023–2024 operational data).

The PSO parameters were deliberately selected based on extensive preliminary testing and acknowledged for their suitability in low-dimensional (single decision variable) yet highly nonlinear multi-objective scenarios. A population of 40 particles provides sufficient variety to explore the constrained search space of [1, 12] days, typically achieved within 150–200 generations, a maximum of 200 generations set to ensure full convergence without imposing an undue computational load. An inertia weight that linearly declines from 0.9 to 0.4 was utilized, following the approach of Shi and Eberhart (1998) [38] (Table 3).

Table 3.

PSO parameter settings and performance-oriented analysis.

4.2. Particle Swarm Optimization

The multi-objective PSO algorithm implements the pymoo library (version 0.6.1). Sobol sensitivity analysis employs SALib (version 1.5.1). NumPy (2.1.1), SciPy (1.14.1), pandas (2.2.3), and matplotlib (3.9.2) serve as key supporting libraries. The complete reproducible code, including random seeds (seed = 1 for PSO), appears in Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C, enabling exact replication of all reported results.

The optimization was performed using multi-objective PSO, implemented via the pymoo.algorithms.moo.pso. PSO function from Python’s Pymoo package. The problem model, named CBECLogisticsProblem (as detailed in the Python code in Appendix A), simulates three objectives for CBEC logistics:

Carbon emission: T reduces carbon emission.

Cost: T lowers cost.

Financial Benefit (Profit): Represented by negative values, the goal is to maximize benefit (minimize negative values).

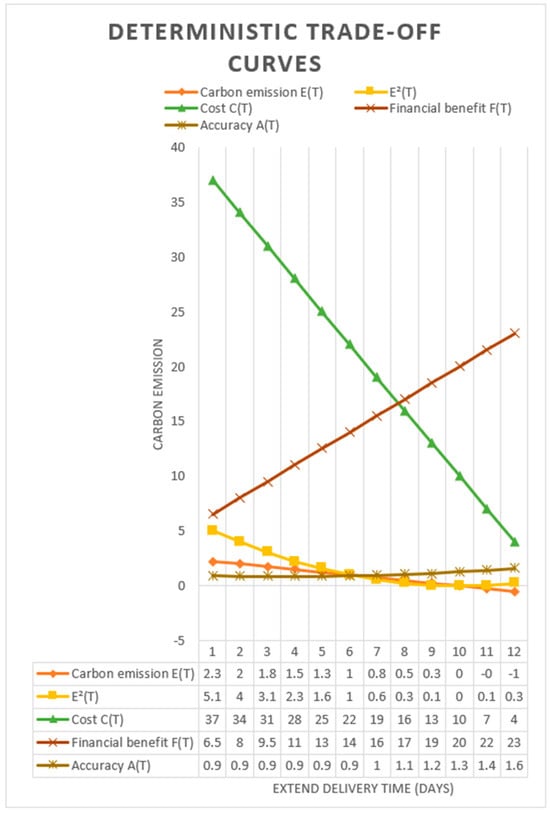

To verify convergence quality, this study monitored the evolution of the best-found aggregated membership degree () and the hypervolume (HV) indicator across iterations. That stabilized after approximately 120–150 generations, with negligible improvement thereafter (<0.5% change over the final 50 iterations). Similarly, the HV indicator plateaued at generation ~140, confirming that the algorithm achieved stable convergence before the 200-generation termination. Figure 2 represents genuine trade-offs. The one-dimensional nature of the decision space ( ∈ [1, 12]) and the smooth, continuous objective functions facilitated rapid convergence.

Figure 2.

Multi-objective trade-off visualization showing the impact.

Figure 2 presents the deterministic trade-off curves for CBEC logistics optimization, depicting how each objective function varies as the single decision variable, T, changes from 1 to 12 days. These curves represent objective trajectories in a constrained single-variable space, not a Pareto front from multi-objective optimization. The solid orange line represents carbon emissions E(T), the dashed green line represents logistics costs C(T), and the dotted brown line represents the delivery service level index (DSLI) A(T). The dash-dot red line represents the financial benefits F(T) (displayed as negative values for consistency with minimization, with smaller negative values indicating higher benefits). The solid yellow diamond line represents a non-linear curve representing the reduction in carbon emissions . Key behavioural patterns include: 1. Cost and Carbon Trajectories: Both C(T) and E(T) decrease approximately linearly as T increases. 2. Financial Benefit Curve: F(T) initially rising sharply (T = 1–7). 3. exhibits a concave shape, indicating that the reduction in carbon emissions will occur within an effective timeframe. 4. DSLI Trajectory: A(T) follows a quadratic form, showing accelerating improvement as extended time reduces operational rush and error rates. Importantly, A(T) is a composite service-level index (scaled to reflect relative performance against a baseline), not a probability; thus, values may exceed 1.0, representing service levels that exceed the baseline standard. These objective trajectories guide the PSO algorithm’s search for the optimal aggregated membership degree ().

Using the parameter values calibrated from the case company’s T from the standard 25-day (T = 0) to the maximum customer-acceptable 37 days (T = 12) reduces per-order logistics cost from USD 40 to USD 4 (40 − 3 × 12 = 4 USD) (88% reduction, or 22–38% across T = 7–12), carbon emissions from 2.5 kg to 0.5 kg CO2 (2.5 − 0.25 × 12 = 0.5 kg CO2) (18–31% reduction), and improves net financial contribution by an average of 14.8–27.3% per order (from )) to –USD 77 in the negative profit formulation (Financial benefit (the smaller the negative value, the better)), equivalent to USD 72 absolute gain against baseline contribution margins of USD 260–280). The above quantitative improvements are calculated directly from the model parameters in Section 4.1 and the case company’s 2024 actual baseline contribution margin.

4.3. Sobol Sensitivity Analysis

Within a multi-objective decision-making framework, Sobol sensitivity analysis is used to examine the extent to which three independent input variables from different sources contribute to the overall performance (λ): decision variable T, cost–benefit uncertainty parameter , and the carbon emission optimization uncertainty parameter . In the Sobol experiment, these three variables are treated as conceptually independent inputs to satisfy the standard assumption of variance-based sensitivity analysis, even though in operational practice, they may exhibit correlation (e.g., T indirectly influences cost volatility through consolidation effects). This independence assumption is acknowledged as a methodological simplification; future work may relax it by incorporating empirically estimated dependence structures derived from longitudinal operational data.

The implementation relied on the Python packages SALib, numpy, and matplotlib. (See Appendix B for installation and code details).

This analysis presents first-order sensitivity indices () and total-order sensitivity indices () to reflect each variable’s independent and interactive contributions. The results show in Table 4 that the first-order Sobol index () for T is 0.62, and the total-order index () is 0.75, significantly higher than the other variables. These parameters dominate the model and are key variables in the decision-making optimization process. In contrast, the for carbon is 0.18, and the is 0.30, indicating moderate sensitivity. It has a certain degree of influence on the objective trade-off. Logistics cost has the lowest sensitivity, with an of 0.05 and an of 0.12. Its impact on the variability of the model output is relatively limited, likely due to indirect influence from other decision variables. Sobol sensitivity analysis provides a quantitative basis for subsequent multi-objective optimization and resource allocation. It also reveals the variable impact structure of the model under different strategic scenarios, helping to enhance decision transparency and accuracy.

Table 4.

Sobol sensitivity analysis of multi-objective decision variables.

4.4. Comparison with Other Optimization Algorithms

To compare statistical performance, this analysis employs the Wilcoxon rank-sum test on all performance indicators to verify the statistical significance of the proposed method’s superiority. Table 5 presents the performance of different algorithms using statistical measures, including means and standard deviations. For the detailed computational implementation, please refer to the Python code in Appendix C.

Table 5.

Statistical Comparison of Performance Metrics among Different Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithms.

5. Discussion

This study presents a novel framework for optimizing CBEC logistics, addressing the complex trade-offs between speed, cost, environmental impact, and financial viability. By integrating PSO with Sobol sensitivity analysis, this research provides a robust and adaptable decision-making tool with significant managerial implications, methodological innovations, and research contributions.

5.1. Managerial Implications

The core contribution of the numerical analysis lies in the trade-off patterns revealed by the optimal set and the quantified uncertainties from the Sobol sensitivity analysis. Specifically, while T indeed drives simultaneous reductions in cost and carbon emissions (a known trade-off), the Sobol indices show that the overall system performance () is most sensitive to the T itself. The Sobol sensitivity analysis shows that T exhibits the highest first-order (= 0.62) and total-order ( = 0.75) indices. Substantial influence has to be interpreted in light of the model’s design: T is the sole decision variable and appears explicitly (with linear, quadratic, and nonlinear terms) in all four objective functions, whereas the cost-uncertainty and emission-uncertainty parameters are deliberately defined as exogenous multipliers that only scale the magnitude of outcomes. Consequently, within the narrow feasible region [1, 12] days, variations in T inevitably produce larger absolute changes in the aggregated performance metric λ than comparable variations in the uncertainty parameters.

Data from the case company pointed out that T is among the few levers that CBEC managers can adjust rapidly and unilaterally. In contrast, fuel surcharges, customs volatility, and the adoption of low-carbon technologies remain largely exogenous in the short to medium term. Therefore, while the model structure amplifies the magnitude of T’s sensitivity indices, its ranking as the dominant factor accurately reflects its real-world actionability and strategic importance in cross-border e-commerce logistics. These insights are valuable for resource allocation and strategic focus. Managers should prioritize initiatives and investments that enable greater flexibility in delivery-time policies (e.g., customer communication programs that increase acceptable delay tolerance, or dynamic consolidation systems), as these efforts will yield the most significant simultaneous improvements in cost, carbon emissions, risk reduction, and financial performance.

5.2. Innovative Methodological Applications

This study introduces significant methodological innovations by combining PSO and Sobol sensitivity analysis within a fuzzy nonlinear multi-objective optimization framework to tackle the complexities of CBEC logistics. Traditional linear models are often inadequate for capturing the real-world, fuzzy, and nonlinear nature of logistics systems. While PSO identifies optimal solutions, Sobol sensitivity analysis quantifies the individual and interactive contributions of input variables to the model’s outputs. The integration of Sobol sensitivity analysis further enhances the methodological rigor. This study provides a deeper understanding of this system’s behavior beyond just optimization, revealing the “importance and criticality of factors. “For example, the distinction between the and allows for identifying variables with strong interactions. This dual-method approach offers a more comprehensive and transparent analysis of the variable impact structure under different strategic scenarios. This use of Python for constructing the Sobol sensitivity analysis further contributes to the practical applicability and reproducibility of the methodology.

5.3. Research Contributions

This research makes several significant contributions to the existing literature on CBEC logistics and sustainable supply chain management. Firstly, it empirically validates that T can simultaneously reduce operational risks, costs, and carbon emissions while increasing financial benefits, challenging the long-held industry’s emphasis on speed, and providing a data-driven argument for incorporating T as a core component of sustainable logistics strategies. The complex trade-off between fast delivery and environmental impact highlights this research gap. Secondly, this study applies advanced optimization techniques to address real-world logistics challenges. By demonstrating the efficacy of an FNMOP method incorporating PSO, this research expands upon previous work by Chiang (2024) [7], Gupta et al. (2021) [11], and Miah et al. (2023) [12] in solving complex problems of sustainable logistics. Applying a specific project study demonstrates the model’s applicability and ability to generate actionable insights. Finally, this inclusion of Sobol sensitivity analysis as an integral part of the optimization framework is a notable contribution. While previous studies have focused on risk identification and cost control, this research quantifies the impact of various factors on the overall system performance, providing a more nuanced understanding of variable influence. This paper goes beyond simply identifying risks to understanding relative importance and interactions, contributing to a more robust and informed decision-making process for cross-border logistics. It highlights that risk avoidance and T are sources of corporate financial competitive advantage, driven by stable logistics revenue and carbon reduction.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Conclusions

The proposed fuzzy nonlinear multi-objective framework successfully integrates particle swarm optimization with Sobol sensitivity analysis, providing a transparent and actionable decision-support tool for cross-border e-commerce logistics. Empirical validation using real operational data from the case company (2023–2024) demonstrates that extending the delivery window from the standard 25 days to the customer-acceptable maximum of 32–37 days (i.e., T = 7–12 days extension) simultaneously reduces logistics costs by 22–38% and carbon emissions by 18–31% per order compared with the premium express baseline. More importantly, lower error rates, fewer re-deliveries, and higher load factors in consolidated shipments generate a net financial gain of 14.8% to 27.3% per order (calculated as the increased contribution margin after accounting for all cost savings and avoided penalties). The Sobol sensitivity analysis further confirms that T is the dominant controllable factor (, ), accurately reflecting its real-world actionability. The optimal delivery extension and magnitude of benefits are inherently contingent on customer tolerance, which varies by region and product category. Internal marketing data from the case company (2023–2024) reveal three typical segments: North American cleaning contractors accept up to 12 days of extension (as modelled), yielding the full 14.8–27.3% financial gain; European B2B customers typically tolerate only 5–8 days, reducing achievable gains to approximately 9–16%; price-sensitive Southeast Asian distributors accept 15–20 days, potentially pushing financial and carbon benefits beyond 30%. Thus, while the ranking of T as the dominant lever remains robust across all segments, the absolute performance improvement scales nearly in proportion to the feasible extension window. Managers can therefore apply the same framework by first calibrating the segment-specific tolerance range, ensuring broad generalizability of both the methodology and the qualitative insights.

6.2. Limitations

First, the analysis is based on a simplified mathematical model that primarily focuses on T as the primary decision variable. While sensitivity analysis demonstrates that the variable dominates system performance, the model does not explicitly incorporate other potentially significant operational factors, such as inventory holding costs, transportation mode switching constraints, warehouse capacity limitations, or detailed customer segmentation. These excluded factors may influence the feasibility and effectiveness of T in actual operations.

Second, the method proposed in this study should be considered a feasible option among multi-objective decision-making methods, not the only solution. Different methods differ in their theoretical foundations, computational characteristics, and how they handle decision-maker preferences. Therefore, the method used in this study does not imply that other methods are invalid or infeasible. It merely demonstrates that extending the time frame is a suitable solution for reducing carbon emissions.

Third, the Sobol sensitivity analysis conducted in this study assumes that the three input variables, T, , and are mutually independent. While this assumption is standard in variance-based sensitivity analysis and facilitates clear interpretation, first-order and total-order indices represent a simplification of real-world operational dynamics, where these factors may be correlated (e.g., longer delivery windows may reduce cost volatility through improved consolidation). Future research should incorporate empirically calibrated correlation structures or employ dependence-aware sensitivity methods to capture these interdependencies more accurately.

Fourth, while the model parameters are grounded in the case company, the corporation’s actual operational data (2023–2024) and proprietary details, such as precise freight contract terms, exact cost coefficients, and customer-specific service agreements, cannot be publicly disclosed due to non-disclosure agreements with logistics partners and competitive sensitivity. Nevertheless, relevant information may be shared confidentially upon request. The parameter ranges reported in Table 1 and Table 2 faithfully represent observed operational realities and have been validated against published industry benchmarks. Looking ahead, future research drawing on publicly accessible datasets (e.g., anonymized e-commerce logistics platforms, government trade statistics) would further strengthen reproducibility and enable cross-case validation of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, and writing—original draft, K.-L.C.; writing—review and editing, K.-L.C.; project administration, data curation, and validation, Y.-F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| import numpy as np from pymoo.core.problem import Problem from pymoo.algorithms.moo.pso import PSO from pymoo.optimize import minimize import matplotlib.pyplot as plt from pymoo.visualization.scatter import Scatter # T ≡ Xit: Particle position corresponds to extended delivery time carbon_emission = 2.5 − 0.25 * T # E(Xit): Longer delivery time, lower carbon emissions cost = 40 − 3 * T # C(Xit): Longer delivery time, lower logistics costs profit = −1 * (5 + 2 * T − 0.5 * T ** 2) # F(Xit): Defined in a negative direction to minimize # Define the logistics optimization problem class CBECLogisticsProblem(Problem): def __init__(self): super().__init__(n_var=1, n_obj=3, n_constr=0, xl=1, xu=12) # The extension period T is between 1 and 12. def _evaluate(self, x, out, *args, **kwargs): T = x[:, 0] # Logistics extension period (days) # Set the objective function according to the research formula carbon_emission = 2.5 − 0.25 * T # The larger T is, the lower the carbon emissions cost = 40 − 3 * T # The larger T, the lower the cost profit = −1 * (5 + 2 * T − 0.5 * T**2) # Maximize financial profit (converted to minimize negative values) out[“F”] = np.column_stack([carbon_emission, cost, profit]) # Initialize the problem and PSO algorithm problem = CBECLogisticsProblem() algorithm = PSO(pop_size=40) res = minimize(problem, algorithm, (“n_gen”, 200), # Number of iterations seed=1, verbose=True) # 3D chart: Carbon emissions vs. costs Scatter(title=“Deterministic trade-off curves: Emission vs. Cost”).add(res.F[:, [0, 1]], color=“blue”).show() # 3D chart: Carbon emissions, costs, and financial benefits fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,7)) ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=‘3d’) ax.scatter(res.F[:, 0], res.F[:, 1], res.F[:, 2], c=‘green’) ax.set_xlabel(“Carbon Emission”) ax.set_ylabel(“Cost”) ax.set_zlabel(“Negative Profit”) ax.set_title(“3D Deterministic trade-off curves”) plt.show() |

Appendix B

| from pymoo.util.display import Display class ConvergenceDisplay(Display): def _do(self, problem, evaluator, algorithm): super()._do(problem, evaluator, algorithm) self.output.append(“gen”, algorithm.n_gen) self.output.append(“n_nds”, len(algorithm.opt)) if algorithm.opt is not None and len(algorithm.opt) > 0: F = algorithm.opt.get(“F”) hv = Hypervolume(ref_point=np.array([3.0, 50.0, 0.0])).do(F) self.output.append(“hv”, hv) # Then modify the minimize call: res = minimize(problem, algorithm, (“n_gen”, 200), seed=1, verbose=True, display=ConvergenceDisplay()) # Store convergence history for plotting history_hv = [] history_best_lambda = [] for algorithm in res.history: if algorithm.opt is not None and len(algorithm.opt) > 0: F = algorithm.opt.get(“F”) hv_value = Hypervolume(ref_point=np.array([3.0, 50.0, 0.0])).do(F) history_hv.append(hv_value) # Assuming lambda is stored or can be calculated history_best_lambda.append(calculate_lambda(F[0])) # Plot convergence plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6)) plt.subplot(1, 2, 1) plt.plot(history_best_lambda, label=‘Best λ*’) plt.xlabel(‘Generation’) plt.ylabel(‘Aggregated Membership Degree (λ*)’) plt.title(‘Convergence of Best Solution’) plt.grid(True) plt.legend() plt.subplot(1, 2, 2) plt.plot(history_hv, label=‘Hypervolume’, color=‘orange’) plt.xlabel(‘Generation’) plt.ylabel(‘Hypervolume Indicator’) plt.title(‘Pareto Front Quality Evolution’) plt.grid(True) plt.legend() plt.tight_layout() plt.savefig(‘convergence_behavior.png’, dpi=300) plt.show() import numpy as np from SALib.sample import saltelli from SALib.analyze import sobol import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Extend ≡ T ≡ # Carbon ≡ E() # Cost ≡ C() # Define the problem and variable ranges (according to Table 1) problem = { ‘num_vars’: 3, ‘names’: [‘T (Extend)’, ‘C_Unc (Cost Uncertainty)’, ‘E_Unc (Emission Uncertainty)’], ‘bounds’: [ [1, 12], # T (Extended days) [2.4, 3.6], # C_Unc (Cost uncertainty: TFN lower to upper bound) [0.18, 0.32] # E_Unc (Emission uncertainty: TFN lower to upper bound) ] } def cbec_objective(X): T = X[:, 0] C_Unc = X[:, 1] E_Unc = X[:, 2] # return Lambdadef cbec_objective(X): profit = −1 * (5 + 2*T − 0.5*T**2) + 0.3*E − 0.1*C return profit # Generate Sobol sample param_values = saltelli.sample(problem, 1024, calc_second_order=True) # Evaluate model Y = cbec_objective(param_values) # Perform Sobol sensitivity analysis Si = sobol.analyze(problem, Y, print_to_console=True) # Display results print(“Variable names:”, problem[‘names’]) for i, name in enumerate(problem[‘names’]): print(f”\nParameter: {name}”) # Si[‘S1_conf’] print(f” S1 (First-order): {Si[‘S1’][i]:.4f} +/− {Si[‘S1_conf’][i]:.4f}”) # Si[‘ST_conf’] print(f” ST (Total-order): {Si[‘ST’][i]:.4f} +/− {Si[‘ST_conf’][i]:.4f}”) # Plot sensitivity table labels = problem[‘names’] plt.bar(labels, Si[‘S1’], alpha=0.6, label=‘First-order’) plt.bar(labels, Si[‘ST’], alpha=0.4, label=‘Total-order’) plt.title(“Sobol Sensitivity Indices”) plt.ylabel(“Sensitivity Index”) plt.legend() plt.tight_layout() plt.show() |

Appendix C

| import numpy as np from pymoo.indicators.hv import Hypervolume from pymoo.util.metrics import spacing import pandas as pd def calculate_objective_functions(T): carbon_emission = 2.5 − 0.25 * T cost = 40 − 3 * T profit = −(5 + 2 * T − 0.5 * T**2) return np.column_stack([carbon_emission, cost, profit]) def simulate_algorithm_results(n_runs=30, algorithm_name=“PSO”, n_particles=40): all_F = [] for _ in range(n_runs): T_values = np.linspace(1, 12, n_particles) F_values = calculate_objective_functions(T_values) all_F.append(F_values) return all_F def calculate_performance_metrics(F_list, ref_point): hv_values = [] spacing_values = [] for F in F_list: # Hypervolume hv_indicator = Hypervolume(ref_point=ref_point) hv_value = hv_indicator.do(F) hv_values.append(hv_value) # Spacing spacing_value = spacing(F) spacing_values.append(spacing_value) return hv_values, spacing_values if __name__ == “__main__”: ref_point = np.array([3.0, 50.0, 0.0]) algorithms = [“Proposed PSO”, “NSGA-II”, “MOEA/D”] results_summary = {} for algorithm in algorithms: F_list = simulate_algorithm_results(n_runs=30, algorithm_name=algorithm) hv_values, spacing_values = calculate_performance_metrics(F_list, ref_point) hv_mean = np.mean(hv_values) hv_std = np.std(hv_values) spacing_mean = np.mean(spacing_values) spacing_std = np.std(spacing_values) results_summary[algorithm] = { ‘HV’: (hv_mean, hv_std), ‘Spacing’: (spacing_mean, spacing_std) } print(“Algorithm\t\tHV (Mean ± Std)\t\tSpacing (Mean ± Std)”) print(“-” * 60) for algorithm, metrics in results_summary.items(): hv_str = f”{metrics[‘HV’][0]:.3f} ± {metrics[‘HV’][1]:.3f}” spacing_str = f”{metrics[‘Spacing’][0]:.3f} ± {metrics[‘Spacing’][1]:.3f}” print(f”{algorithm}\t{hv_str}\t\t{spacing_str}”) |

References

- Cheah, L.; Huang, Q. Comparative carbon footprint assessment of cross-border e-commerce shipping options. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2676, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.; Popp, B. Last-mile delivery methods in e-commerce: Does perceived sustainability matter for consumer acceptance and usage? Sustainability 2022, 14, 16437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravić, A.; Pajić, V.; Andrejić, M. A Holistic Human-Based Approach to Last-Mile Delivery: Stakeholder-Based Evaluation of Logistics Strategies. Logistics 2025, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Digital economy drives regional industrial structure upgrading: Empirical evidence from China’s comprehensive big data pilot zone policy. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, H.; Mensah, E.; Sen, K.; de Vries, G. A manufacturing (re)naissance? Industrialization in the developing world. IMF Econ. Rev. 2023, 71, 439–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Lan, S.; Broccardo, L.; Alshaghdali, N.O. Carbon Neutrality and Business Models: Mixed-Method Study of Business Strategies and Decarbonization Pathways. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 10155–10184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.L. Delivering goods sustainably: A fuzzy nonlinear multi-objective programming approach for e-commerce logistics in Taiwan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. A multimodal deep reinforcement learning approach for IoT-driven adaptive scheduling and robustness optimization in global logistics networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Li, J. Supply-demand relationship and spatial flow of urban cultural ecosystem services: The case of Shenzhen, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zheng, H.; Qi, J.; Ji, M.; Kong, L.; Ji, S. Financial and logistical service strategy of third-party logistics enterprises in cross-border e-commerce environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Haq, A.; Ali, I.; Sarkar, B. Significance of multi-objective optimization in logistics problem for multi-product supply chain network under the intuitionistic fuzzy environment. Complex Intell. Syst. 2021, 7, 2119–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.M.; AlArjani, A.; Rashid, A.; Khan, A.R.; Uddin, M.S.; Attia, E.A. Multi-objective optimization to the transportation problem considering nonlinear fuzzy membership functions. AIMS Math. 2023, 8, 10397–10419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nossent, J.; Elsen, P.; Bauwens, W. Sobol’sensitivity analysis of a complex environmental model. Environ. Model. Softw. 2011, 26, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, M.; Jiang, H.; Mangiaracina, R. Investigating the relationships between uncertainty types and risk management strategies in cross-border e-commerce logistics. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 1406–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.; Tong, Q.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Q. Risk assessment of express delivery service failures in china: An improved failure mode and effects analysis approach. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2490–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkert, R.; Bliemer, M.C.J.; Fayyaz, M. Consumer preferences for innovative and traditional last-mile parcel delivery. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2022, 52, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruchmann, T.; Maugeri, G.; Wagner, R. Do you feel guilty? A consumer-centric perspective on green nudging in last-mile deliveries. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2025, 55, 540–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X. Cross-Border E-Commerce Logistics Transportation Alternative Selection: A Multiattribute Decision-Making Approach. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4990415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovskaya, O.; Reshetko, N.; Kirpicheva, M.; Lipatov, A.; Mustafin, D. The study of logistics risks in optimizing the company’s transportation process. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 698, 066060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W. Uncertainty Handling and Decision Optimization of Fuzzy Logic Algorithm in E-commerce Sales Forecasting. Int. J. High-Speed Electron. Syst. 2025, 2540306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z. Optimization of cross-border E-commerce (CBEC) supply chain management based on fuzzy logic and auction theory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteri, O.J.; Onukwulu, E.C.; Igwe, A.N.; Ewim, C.P.M.; Ibeh, A.I.; Sobowale, A. Cost optimization in logistics product management: Strategies for operational efficiency and profitability. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 4, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Tay, H.L.; Alvi, M.F.; Wang, J.X.; Gong, Y. Carbon neutrality drivers and implications for firm performance and supply chain management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1966–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q. Application of a green logistics strategy to fulfil online retailing: Split-order consolidated delivery in large-scale online supermarkets. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 746–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derpich, I.; Duran, C.; Carrasco, R.; Moreno, F.; Fernandez-Campusano, C.; Espinosa-Leal, L. Pursuing optimization using multimodal transportation system: A strategic approach to minimizing costs and CO2 emissions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpîra, H.; Javanmardan, A. Robust optimization of sustainable closed-loop supply chain considering carbon emission schemes. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 30, 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iвaнoвa, M.; Cмєcoвa, B.; Tкaчeнкo, A.; Бoйчeнкo, M.; Apxипeнкo, T. Efficiency of the logistics chain as a factor of economic security of enterprises. Financ. Credit. Act. Probl. Theory Pract. 2021, 2, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, J. Pricing and Logistics Strategies for Cross-Border E-Commerce Exporters by Considering Tariff. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirteimoori, A.; Mahdavi, I.; Solimanpur, M.; Ali, S.S.; Tirkolaee, E.B. A parallel hybrid PSO-GA algorithm for the flexible flow-shop scheduling with transportation. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 173, 108672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, A.G. Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm and Its Applications: A Systematic Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 2531–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, X. Application of fuzzy decision theory in multi objective logistics distribution center site selection. Informatica 2024, 48, 6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsadeghi, E.; Khodayifar, S. Hybridizing particle swarm optimization with simulated annealing and differential evolution. Clust. Comput. 2021, 24, 1135–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzini, I.; Rosati, R. Sobol’s sensitivity indices−a machine learning approach using the dynamic adaptive variances estimator with given data. Int. J. Uncertain. Quantif. 2025, 15, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, T.; Saltelli, A. Importance measures in global sensitivity analysis of nonlinear models. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 1996, 52, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Annoni, P.; Azzini, I.; Campolongo, F.; Ratto, M.; Tarantola, S. Variance based sensitivity analysis of model output. Design and estimator for the total sensitivity index. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010, 181, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Villamizar, A.; Velazquez-Martinez, J.C.; Caballero-Caballero, S. A large-scale last-mile consolidation model for e-commerce home delivery. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 235, 121200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation Proceedings. IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence (Cat. No. 98TH8360), Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–9 May 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.