Abstract

New quality productive forces (NQPFs) provide vital impetus for the development of advanced manufacturing clusters (AMCs). Using 30 provincial panel data in China from 2013 to 2023, this study employs two-way fixed effects, mediation, and threshold effect models to analyze the impact of NQPFs on AMCs. The results reveal that (1) NQPFs significantly promote the development of AMCs, and this conclusion remains robust after rigorous endogeneity tests and robustness tests. (2) NQPFs exert a stronger driving effect on AMCs in coastal regions than in inland regions (both significant), and they are significant in non-resource-based regions and highly industrialized regions. (3) NQPFs indirectly foster the development of AMCs by prompting technological innovation (encompassing imitative and independent innovation), facilitating talent agglomeration, and driving industrial structure advancement. (4) The driving effect of NQPFs exhibits a significant nonlinear upward trend. This study provides new theoretical insights and empirical evidence for the sustainable development of the manufacturing industry.

1. Introduction

Industrial clusters are an inevitable outcome of industrialization. They feature spatial agglomeration, network collaboration, local embeddedness, and self-organization [1]. A country’s competitiveness depends on its industrial strength, and industrial clustering provides vital support for industrial competitiveness [2]. Thus, cultivating globally competitive advanced manufacturing clusters (AMCs) has become a critical hallmark of leading manufacturing countries. In recent years, the United States [3], Germany [4], and Japan [5] have introduced specialized policies to accelerate the development of clusters. Since 2019, China has also launched a special action plan for AMCs, yielding remarkable results. In 2023, the output value of the leading industries within China’s AMCs surpassed 20 trillion yuan. By the end of 2024, China had cumulatively cultivated 80 national-level AMCs. This provided a comprehensive coverage of major industrial chains for the first time. Despite this progress, China’s AMCs still face significant challenges, including “agglomeration without effective synergy”, weak industrial support systems, and limited collaborative innovation capabilities. Therefore, promoting the development of AMCs remains a crucial issue for China in achieving sustainable manufacturing growth and enhancing international competitiveness.

At the historical confluence of a new round of scientific and technological revolution and industrial transformation, General Secretary Xi Jinping proposed the concept of “new quality productive forces”. This concept gives a fundamental guide for tackling the issue. New quality productive forces (NQPFs) are defined by the leapfrog development of laborers, objects of labor, means of labor, and their optimal combination. Their core characteristic is innovation. A significant increase in total factor productivity (TFP) serves as their primary hallmark. Compared with traditional productive forces, NQPFs represent an advanced state. They have higher technological levels, better quality, greater efficiency, and stronger sustainability. Thus, NQPFs serve as the core driving force for new industrialization [6]. Meanwhile, AMCs are the core carrier for advancing new industrialization. The high-tech, high-efficiency, and high-quality characteristics of NQPFs are highly consistent with the inherent requirements of AMCs for transformation towards high-endization, intelligence, and greenization. Through multiple pathways, such as technological innovation and industrial upgrading, NQPFs can create unprecedented opportunities for the development of AMCs.

Clarifying how NQPFs drive the development of AMCs is a pressing theoretical and practical issue. However, existing literature has rarely examined the relationship between NQPFs and AMCs systematically. To fill this research gap, this study integrates NQPFs and AMCs within a unified analytical framework. Using provincial panel data, it systematically examines the impact of NQPFs on China’s AMCs through an integrated theoretical and empirical approach. It also clarifies the underlying mechanisms, nonlinear increasing characteristics, and heterogeneous effects of this relationship. The findings provide empirical evidence for sustainable industrial policymaking. Moreover, the mechanisms and pathways identified provide references for transforming manufacturing clusters in other major industrial economies.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Literature Review on NQPFs

Extensive scholarly research has explored the concept of “NQPFs”. TFP traditionally measures economic efficiency through assessing output relative to total input [7,8]. In contrast, NQPFs extend beyond mere efficiency measurement by prioritizing innovation, structural upgrades, and quality improvements in production. While TFP is primarily an economic indicator, NQPFs reflect advanced productive forces driven by new technologies, the creative use of resources, and significant industrial transformations. As a result, NQPFs provide a broader and more forward-looking perspective on productivity. This section thus centers on two key dimensions of NQPFs: connotation and measurement. In terms of the connotation of NQPFs, scholars primarily adopt the perspectives of political economy, historical materialism, and systems theory. In political economics, NQPFs are defined as productive forces driven by scientific and technological innovation. They arise from major disruptive technological breakthroughs [9]. “New” manifests in novel elements and fresh forms of manifestation, while “quality” embodies new essence, high standards, superior craftsmanship, and qualitative advantages [10]. From the perspective of historical materialism, NQPFs are understood as a more advanced form of productive forces that stem from the continuous qualitative upgrading of their constituent elements [11]. They are characterized by core features of greenization, digitalization, and intelligentization [12]. In systems theory, NQPFs are described as a “factor-structure-function” integrated system. These interconnected components interact to shape performance [13]. Some scholars from an ecological perspective define NQPFs as essentially green productive forces [14].

For assessing the NQPFs’ level, scholars mainly focus on constructing evaluation indicator systems. It emerges with two principal methodological frameworks. First, based on the components of NQPFs, scholars construct evaluation systems from three aspects: laborers, labor objects, and means of labor [15]. Within this framework, Lin et al. (2024) [16], Wang et al. (2024) [17], and Gang & Hongrui (2025) [18] assessed the NQPFs’ level at the provincial, municipal, and enterprise scales in China, respectively. Second, based on NQPFs’ functions, scholars view NQPFs as entities encompassing three dimensions: science and technology, green development, and digitalization, constructing indicator systems from scientific and technological productivity, green productivity, and digital productivity [19]. Based on this framework, Cheng et al. (2025) [20] and Luo et al. (2025) [21] calculated the NQPFs’ level at the provincial and municipal scales. Additionally, some scholars measured the NQPFs’ level at municipal and enterprise scales in China using total factor productivity [22,23] and text analysis [24,25].

2.1.2. Literature Review on AMCs

In recent years, scholars have conducted extensive research on AMCs. The relevant part of this study mainly focuses on their characteristics, measurement, and influencing factors. AMCs are groups centered around high-end manufacturing that form through the aggregation of enterprises, research institutions, and service systems within specific regions. These groups display technological relevance, collaborative complementarity, and are driven by innovation. Notably, AMCs exhibit high-tech, high-end, and high-efficiency industrial qualities [26], and they feature a concentration of regional networked suppliers, inter-firm learning, and the decentralization and flattening of production chains [27]. Compared to traditional manufacturing clusters, AMCs feature more advanced industrial forms, technologies, manufacturing models, and management systems [28]. For calculating the AMCs’ level, scholars primarily use survey data collected from enterprises. Although this provides useful information, it depends on subjective opinions. Furthermore, existing empirical studies mainly focus on case studies of a few cities or provinces. There still lacks broad, comparative research at the provincial level across China.

The factors influencing the development of AMCs are multifaceted. At the enterprise level, an enterprise’s capacity and its ability to implement advanced manufacturing modes are key factors determining whether cluster enterprises can do so [29]. Relational embeddedness also exerts a positive impact on the innovation performance of intra-cluster enterprises [30]. Inter-firm knowledge spillovers and inter-firm innovation linkages effectively facilitate cluster growth. Among the three dimensions of inter-firm innovation linkages, including enterprise collaboration, personnel mobility, and enterprise spin-offs, all play mediating roles [31]. In the internal cluster environment, four factors exert a decisive effect on determining technological learning opportunities within industrial cluster networks. They are intrinsic technological complexity, interconnectedness between products and processes, path dependency in knowledge search, and the incremental nature of cluster technological development [32]. In the external cluster environment, the restructuring of global value chains provides new opportunities for fostering world-class AMCs [33]. Foreign direct investment (FDI) can drive AMCs by promoting cluster networking, industrial chain optimization, and labor mobility, while also indirectly facilitating their growth through technological innovation [34]. Furthermore, Dai & Luo (2021) [35] pointed out that cluster collaborative innovation performance is directly or indirectly affected by the external environment for collaborative innovation in AMCs, the innovation learning capabilities of cluster firms, and inter-firm collaboration in clusters. Wojciech & Valentina (2022) [36] argued that business support organizations (BSO) can help enterprises in clusters overcome key barriers to adopting Industry 4.0. Chen & Wang (2024) [37] found that industrial foundations, technological innovation capabilities, social institutional environments, and government policies can have favorable effects on the development of AMCs.

2.1.3. Literature Review on the Relationship Between NQPFs and AMCs

Existing literature has primarily focused on the role of NQPFs in driving manufacturing development, thus far only touching on the broader manufacturing sector without delving into its sub-fields. Zhang (2024) [38] posited that NQPFs can drive manufacturing enterprises to achieve green transformation. Their impact mainly manifests in four dimensions: enhancing resource utilization efficiency, optimizing industrial structure, improving environmental governance, and promoting technological innovation and green development. Song & Wang (2024) [39] found that NQPFs can significantly strengthen the resilience of the manufacturing industry chain. This strategic substitutability of domestic value chains exerts a positive moderating effect. Liu et al. (2025) [40] proposed that NQPFs enhance the international competitiveness of the manufacturing industry via technological, green, and digital pathways. Although the literature has not directly explored the relationship between NQPFs and AMCs, it provides a crucial foundation for understanding the impact of NQPFs on AMCs.

Above all, few studies have empirically tested the impact of NQPFs on AMCs; this paper fills this research gap through provincial-level panel data. In view of this, this paper seeks to make the following contributions. (1) It innovatively analyzes the impact of NQPFs on AMCs. This provides new insights into understanding and assessing the economic effects of NQPFs. It also expands on relevant research on NQPFs in AMCs and offers policy implications for further developing NQPFs and exploring new pathways for AMC progress. (2) The paper reveals the mechanism by which NQPFs impact AMCs. It assesses how NQPFs promote AMCs’ development through the talent agglomeration effect, technological innovation effect, and industrial structure advancement effect, thus widening research in the AMCs field. (3) It examines the heterogeneous impact of NQPFs on AMCs based on geographical location, resource endowment, and industrialization level. The findings can guide more targeted policies and provide practical guidance to accelerate NQPFs and AMCs.

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

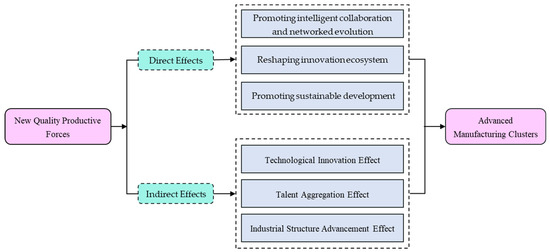

2.2.1. Direct Effects of NQPFs on AMCs

NQPFs provide a strong impetus for the development of AMCs, mainly manifested in the following three aspects: First, NQPFs promote the intelligent collaboration and networked evolution of clusters. Enterprises within AMCs already possess inherent advantages in industrial linkages and spatial proximity. According to Porter’s theory of industrial clusters, the AMCs’ sustained competitiveness hinges on systemic inter-firm collaboration and dynamic knowledge networks, moving beyond mere physical proximity. NQPFs further break the boundaries of enterprises through the integration of digital technologies, prompting clusters to shift from “physical aggregation” to “intelligent collaboration”. By leveraging technologies such as the industrial Internet and cloud platforms, enterprises within clusters can achieve real-time data interaction, resource sharing, and process collaboration. This promotes a flat, platform-based production organisation mode. The intelligent scheduling system strengthens inter-enterprise linkages within the cluster, improving response speed and collaboration efficiency. This enhances the flexible manufacturing and system integration capabilities of the entire cluster [41].

Second, NQPFs reshape the innovation ecosystem of clusters. Under the guidance of NQPFs, the innovation organization logic of AMCs has evolved. Innovation is no longer solely led by a few leading enterprises but has evolved into a collaborative innovation ecosystem involving multiple stakeholders and cross-border integration. Specifically, digital tools lower collaboration costs, enabling widespread participation of small and medium-sized enterprises in joint R&D. This process strengthens the knowledge spillover effect in geographic proximity. At the same time, the technical connection mechanism based on big data and artificial intelligence enhances the speed and breadth of knowledge flow, promotes the rapid diffusion of advanced manufacturing elements and the improvement of local absorption capacity, driving the entire cluster to transform from “manufacturing aggregation” to “innovation aggregation” [42].

Third, NQPFs promote the sustainable development of clusters. NQPFs emphasize green, low-carbon development. Through guiding the use of clean energy, the application of green technologies, and the intelligent monitoring of carbon emissions, NQPFs promote the ecological transformation of AMCs. They support the development of green supply chains and industrial ecosystems. They also facilitate the formation of cooperation mechanisms, including energy sharing, resource recycling, and pollution co-management, among enterprises within the cluster [43]. At the same time, relying on digital governance platforms, the government and parks can more efficiently implement dynamic supervision of cluster operations and precise policy delivery, enhance the governance efficiency of clusters, build an efficient, fair, and transparent collaborative governance system, and strengthen the green competitive advantages and social responsibility image of clusters. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

NQPFs can significantly drive AMCs by directly fostering clusters’ intelligent collaboration, reshaping their innovation ecosystem, and enabling their sustainable development.

2.2.2. The Effect of Technological Innovation

According to Schumpeter’s innovation theory, strengthening technological innovation is a key driver for AMCs’ growth. As innovative enablers, NQPFs can substantially enhance technological innovation, thereby further advancing the development of AMCs.

Building upon this theoretical foundation, NQPFs serve as a powerful impetus for technological innovation [44]. As an innovation-driven form of productivity, their development requires the constant introduction and use of new technologies, processes, and methods. This ongoing need for innovation encourages enterprises, research institutions, and other entities to scale up their investment in technological R&D initiatives. As a result, technological innovation activities advance. Furthermore, NQPFs facilitate the optimal allocation of resources for technological innovation. Driven by them, resources, such as talent, funds, and equipment, are allocated and employed more effectively. Their development attracts top talent and innovation teams, building a solid foundation for technological innovation. They also motivate capital markets to invest in technological innovation, ensuring enough financial support for these efforts. Moreover, NQPFs accelerate the transformation and application of technological innovation outcomes. Their growth not only advances technological innovation but also helps turn innovation results into practical, productive forces. Mechanisms such as industry-university-research collaboration, technology transfer, and outcome transformation serve as key enablers for NQPFs. Specifically, they empower NQPFs to translate innovation outputs efficiently into tangible productivity. This drives industrial upgrading and economic growth. They also broaden the application of these innovations, raising society’s overall technological level and innovation capacity.

According to the theory of dual innovation, technological innovation is categorized into imitative innovation and independent innovation [45]. From the perspective of evolutionary economics, each type plays a distinct role at different stages of AMCs. Imitative innovation focuses on the introduction, absorption, and re-creation of existing technologies, products, or processes [46]. With its features of rapid launch, low risk, and quick results, it helps enterprises quickly narrow the gap with advanced technologies and improve their basic technological level. The early stage of AMCs represents a “germination-growth” phase of gradual evolution. Imitative innovation enables AMCs’ enterprises to quickly acquire technologies, boost production, and gain an initial advantage. With local adaptation, it also strengthens unique capabilities through assimilating foreign technologies. This establishes a foundation for future advancement. As AMCs grow in scale and technological complexity, they reach a mature stage that demands qualitative breakthroughs. At this point, independent innovation [47] becomes essential for overcoming path dependencies and establishing core competitiveness. It refers to original technological breakthroughs made by enterprises or R&D entities based on mastering core intellectual property rights. By independently developing key core technologies, cluster enterprises can break free from reliance on external technologies and boost their added value and leading position in the global industrial chain. Additionally, independent innovation can stimulate the collaboration effect of innovation within the cluster and promote the fusion development of emerging technologies and industries. This further spawns new growth drivers and industrial forms, which in turn strengthen the systemic resilience and innovation vitality of manufacturing clusters. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.

NQPFs can foster the development of AMCs by prompting technological innovation.

2.2.3. The Effect of Talent Aggregation

AMCs’ cultivation requires the joint efforts of various resources. Especially, talent resources can leverage their subjective activity to coordinate other resources, thereby playing a leading role. NQPFs, with talent as their key element, can promote talent aggregation, thereby advancing the development of AMCs.

First, NQPFs can create diverse employment opportunities. During the development of NQPFs, new industries and economic models are continuously fostered. This not only expands the scale of demand in the talent market but also enriches the diversity of job types. It thereby forms a powerful talent aggregation effect [48]. Second, NQPFs can provide high-quality living conditions for talents. The development of NQPFs boosts regional economic strength. It allows more resources to be allocated to optimizing the layout of healthcare, education, and other key sectors, as well as to upgrading community service systems and transportation infrastructure. In turn, this makes talents’ lives more convenient and comfortable. This high-quality living environment reduces the push factors that drive talent outflow, as it not only attracts talent from other regions but also retains local talent, thereby accelerating talent concentration [49]. Finally, NQPFs can facilitate the virtual aggregation of talents. Talents can leverage digital collaboration platforms and remote work technologies, eliminating the need for spatial concentration. They can carry out work through online collaboration, which not only overcomes geographical barriers to attract talent from diverse regions but also fosters virtual-level talent aggregation, thereby providing new pathways for talent advancement.

Talent aggregation primarily promotes the development of AMCs in three ways. First, it reduces AMCs’ operating costs. The influx of talent into AMCs generates economies of scale. This enables enterprises within the cluster to secure suitable talent without lengthy recruitment cycles, thereby significantly cutting time and labor costs [50]. With sufficient talent, each enterprise in the cluster can focus on its comparative advantage, promoting specialized division of labor within the cluster and thereby reducing redundant investment. Second, it stimulates innovative vitality in AMCs. Talent aggregation provides continuous knowledge and intellectual support for AMCs’ innovation. Frequent interaction among talents not only accelerates the dissemination of knowledge and information but also promotes inter-field knowledge recombination and recreation. Thus, it drives the emergence of new technologies, products, and processes [51]. The aggregation of talent exhibits a Matthew effect: the more talent a cluster attracts, the stronger its ability to draw further talent becomes, thereby providing sustained intellectual resources for cluster innovation. Third, it optimizes the ecological environment of AMCs. The agglomeration of high-quality talent can attract more enterprises to invest in and settle in local AMCs. To tap into this talent pool, enterprises are compelled to continuously boost their competitiveness, thereby promoting the high-quality development of AMCs. By aggregating diverse talents, the industrial chains within AMCs can be further improved, and the synergy among enterprises strengthened. The concentration of talent also heightens demand for high-quality products, driving enterprises to innovate and optimize. This fosters an interactive dynamic within the cluster where companies compete while cooperating and elevate each other through collaboration. Consequently, it further enhances the stability and vitality of the cluster ecosystem [52]. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

NQPFs can foster the development of AMCs by facilitating talent agglomeration.

2.2.4. The Effect of Industrial Structure Advancement

NQPFs serve as a key driver of industrial structure upgrading, encompassing both its rationalization and advancement. Previous research has demonstrated that traditional manufacturing agglomeration may hinder the development of industrial structure rationalization [53]. AMCs embody an advanced form of manufacturing agglomeration. Therefore, this study focuses solely on the mechanism by which NQPFs foster the development of AMCs by driving industrial structure advancement.

NQPFs can effectively drive the advancement of the industrial structure. First, NQPFs reshape the division of labor in the industrial value chain. By leveraging technologies such as artificial intelligence and advanced manufacturing, NQPFs disrupt the rigid structure of traditional value chains, driving the migration of R&D, design, production, manufacturing, marketing, and services toward high-end segments. Through technological innovation, enterprises gain a foothold in high-value-added segments of the value chain. This not only accelerates the restructuring of the global industrial division of labor but also enhances overall industry competitiveness. Second, they catalyze new forms of industrial organization. Relying on technologies such as the Internet of Things and big data, NQPFs transcend geographical constraints. They further drive the transformation of industrial organization models through virtual network collaboration and cloud-based resource coordination. Enterprises establish open ecosystems through data sharing and resource collaboration. This accelerates the flow of factors and collaborative innovation within industrial chains. Thus, industrial organization evolves from a decentralized to an intensive model [54]. Finally, they stimulate the driving force of demand upgrading. New products created by NQPFs, such as smart terminals and new energy equipment, trigger changes in market demand. This forces enterprises to optimize their product mix and increase investment in technology-intensive fields. Consequently, the evolution of industrial structure is propelled to a higher level.

The advancement of industrial structure drives the development of AMCs mainly through the following three aspects. Firstly, the advancement of the industrial structure plays a fundamental role in optimizing the allocation of production factors. Driven by both market price signals and technological progress, resources are gradually shifted from labor-intensive, low-value-added industries to technology-intensive, high-efficiency industries. This achieves a dual improvement in efficiency and performance, thereby providing high-quality production resource support for AMCs. Secondly, the industrial structure advancement promotes the concentration of high-tech enterprises in specific regions. Strategic emerging industries, such as new-generation information technology, high-end equipment manufacturing, and energy conservation and environmental protection, have steadily developed amid industrial transformation and upgrading. This has attracted many high-end talents, R&D funds, and innovation resources to gather in advantageous regions. Within these regions, enterprises utilize shared platforms to integrate technologies, information, and resources. This reduces R&D risks and enhances the conversion efficiency of innovation achievements [55]. Thirdly, it facilitates cooperation between upstream and downstream enterprises. The widespread application of digital technology enables manufacturing enterprises to optimize internal management and resource integration. They leverage data platforms, intelligent supply chains, and other tools to foster a close linkage effect across the industrial chain. Upstream raw material supply, manufacturing and processing, and downstream distribution services realize cost savings and efficiency gains through synergies. This builds a stable development chain for AMCs. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4.

NQPFs can foster the development of AMCs by driving industrial structure advancement.

Based on the above theoretical analysis, the mechanism by which NQPFs drive AMCs is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of NQPFs on AMCs.

3. Research Design

3.1. Variable Selection

3.1.1. Explained Variable

The explained variable of this paper is AMCs. The first step is to define the scope of advanced manufacturing. To begin, the Statistical Classification of New Industries, New Business Forms and New Business Models (2018), issued by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, provides a classification of advanced manufacturing. However, relevant data under this classification is not readily available. Because the 2018 classification is based on China’s National Economic Industry Classification (GB/T 4754-2017) [56], the process starts by mapping the advanced manufacturing minor categories from the 2018 classification onto the minor categories in the 2017 National Economic Industry Classification. Once this mapping is complete, the industries containing these minor categories are identified. The process then narrows the focus: only those industries in which the proportions of advanced manufacturing minor categories meet the characteristic standards are included in the defined statistical scope. By the end of this step, nine industries from the National Economic Industry Classification (GB/T 4754-2017) are designated as advanced manufacturing. These industries are: Manufacturing of Raw Chemical Materials and Chemical Products (C26), Manufacturing of Medicines (C27), Manufacturing of General Purpose Machinery (C34), Manufacturing of Special Purpose Machinery (C35), Manufacturing of Automobiles (C36), Manufacturing of Railway, Ship, Aerospace, and Other Transport Equipment (C37), Manufacturing of Electrical Machinery and Apparatus (C38), Manufacturing of Computers, Communication and Other Electronic Equipment (C39), and Manufacturing of Measuring Instruments and Machinery (C40).

The second and final step involves measuring the AMCs’ level. The location quotient method can calculate the concentration of an industry within a region. It removes the effects of regional differences in size. Thus, it accurately shows the spatial distribution of geographical factors. Based on Feng et al. (2024) [34], this study adopts the location quotient method and uses the business revenue of industrial enterprises above designated size to measure the AMCs level:

In Equation (1), i and t represent province and year, respectively; represents the AMCs level of province i in year t; represents the business revenue of advanced manufacturing enterprises above designated size of province i in year t; represents the total business revenue of industrial enterprises above designated size of province i in year t; represents the sum of the business revenue of advanced manufacturing enterprises above designated size across the 30 provinces selected in this study in year t; and represents the sum of the total business revenue of industrial enterprises above designated size across the 30 provinces in year t.

3.1.2. Core Explanatory Variable

The core explanatory variable of this paper is NQPFs. Marxist theory states that productive forces include laborers, labor objects, and means of labor. Productive forces arise when laborers’ physical and mental abilities are combined with labor objects and means of labor. NQPFs are essentially advanced forms built on these three elements. Therefore, drawing on research by Wang & Wang (2024) [15], this study constructs an evaluation indicator system for NQPFs across three aspects: laborers, labor objects, and means of labor, as shown in Table 1. At the laborer level, talent is considered across efficiency, quality, and spirit. Industrial development and the ecological environment shape labor objects. Means of labor include both tangible and intangible labor resources. The weights of each indicator are determined by the entropy weight method [57,58].

Table 1.

NQPFs’ evaluation indicator system.

3.1.3. Mediating Variables

The mediating variables of this paper are technological innovation (TEC), talent agglomeration (TAG), and industrial structure advancement (ADV). TEC is divided into imitative innovation (IMIT) and independent innovation (IND). IMIT is measured by the technological renovation expenditure of industrial enterprises above designated size [59], and IND is measured by the internal R&D expenditure of industrial enterprises above designated size. TAG is measured by the proportion of the sum of the number of employees in the Information Transmission, Software, and Information Technology Services, and Scientific Research and Technical Services in urban units to the total number of employees [60]. ADV is measured by the product of the output share of each industrial sector and its labor productivity:

In Equation (2), represents the ADV level of province i in year t; and represents the added value and number of employees in industry j in province i in year t, respectively; represents the total output value of province i in year t.

Previous studies grouped all industries into just three major sectors [61,62]. This ignores internal differences. For example, both industry and construction are part of the secondary industry. However, industrial enterprises can drive efficient production through technological innovation. In contrast, the on-site nature of construction leads to a low mechanization rate, creating a significant gap in labor productivity. Considering data availability, this paper subdivides industries into nine categories: Agriculture, Forestry, Animal Husbandry and Fishery, Industry, Construction, Wholesale and Retail Trades, Transport, Storage and Post, Hotels and Catering Services, Financial Intermediation, Real Estate, and Others. It enables a more accurate measurement of the ADV level.

3.1.4. Control Variables

Given the influence of other confounding factors, relevant control variables should be added to improve the accuracy of the regression results on the impact of NQPFs on AMCs. Four control variables are selected: urbanization level (Urb), measured by the proportion of the urban population in the regional year-end total population; financial development level (Fin), measured by the ratio of year-end deposit and loan balances of financial institutions to the regional GDP; social consumption level (Sum), measured by the proportion of total retail sales of consumer goods to the regional GDP; openness level (Open), measured by the ratio of total import and export of goods by foreign-invested enterprises to the regional GDP.

3.2. Model Specification

3.2.1. Baseline Regression Model

To test the direct impact of NQPFs on AMCs, this study constructed the benchmark regression model as follows:

In Equation (3), represents AMCs level in province i in year t; represents NQPFs level in province i in year t; encompasses a series of control variables; represents the intercept term, represents the impact coefficient of NQPFs on AMCs, and represents the impact coefficient of control variables on AMCs; , , and represent province fixed effects, year fixed effects, and random error terms, respectively.

3.2.2. Mediation-Effect Model

To verify the mediating role in the process of NQPFs promoting AMCs, according to Jiang (2022) [63], this study constructed the mediating effect model [64] based on Equation (3):

In Equation (4), represents the mediating variable, with other variables defined as in Equation (3). If the coefficient is significant, it means that the NQPFs can promote AMCs through this mediating variable. It is important to note that the causal interpretation of the above mediation analysis relies on the assumption of no hidden confounding.

3.3. Data Source and Processing

This study selected 30 provinces in China from 2013 to 2023 as the research sample (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). The data required are mainly sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, local statistical yearbooks, and local government work reports. Specifically, the revenue of advanced manufacturing enterprises above designated size used to measure the level of AMCs is sourced from the China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, China Economic Census Yearbook, and local statistical yearbooks. Among the indicators for measuring NQPFs level, the entrepreneurial activity indicator is derived from the Index of Regional Innovation and Entrepreneurship in China (IRIEC) compiled by the Enterprise Big Data Research Center of Peking University; the density of industrial robot installations is derived from the International Federation of Robotics (IFR); the consumption of renewable energy electricity is sourced from the National Energy Administration; the digital economy indicator is referenced from the research of Zhao et al. (2020) [65] and Shao et al. [66], which measures the indicator from two dimensions: Internet development and digital finance accessibility. Some missing data were imputed using interpolation and moving average methods. Control variables were log-transformed to alleviate the impact of dimensional differences, as well as to control heteroscedasticity and statistical bias. The results of the descriptive statistical analysis of the main variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of main variables.

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1. Typical Fact Analysis

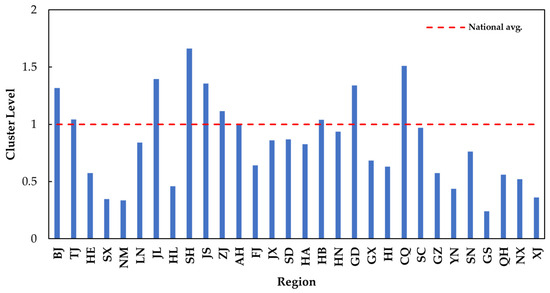

Based on the calculation results, this study analyzes the average levels of AMCs across regions and sub-industries from 2013 to 2023. As shown in Figure 2, the spatial distribution of AMCs exhibits pronounced regional heterogeneity during the sample period. In the figure, the bars denote the average cluster level for each region, and the red reference line (Cluster Level = 1) indicates the national average level of AMCs. Specifically, the average levels of AMCs in Beijing, Tianjin, Jilin, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hubei, Guangdong, and Chongqing all exceed 1, indicating that these levels are higher than the national average. This illustrates that these regions have achieved better cluster development. The average levels of AMCs in Anhui, Hunan, and Sichuan are just below 1, but their levels exceeded 1 in certain individual years, demonstrating that cluster development in these regions is approaching the national average and possesses considerable growth potential. The average levels of AMCs in the rest remain low.

Figure 2.

Average Level of AMCs by Region (2013–2023).

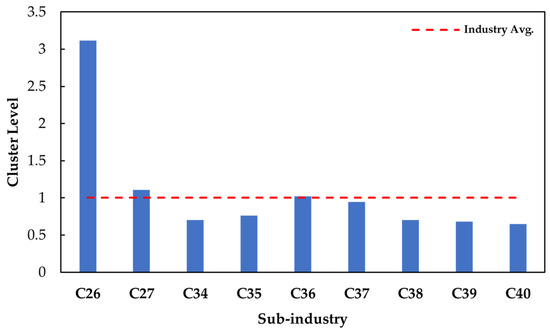

By industry, as shown in Figure 3, the average levels of AMCs vary considerably across sub-industries during the sample period. In the figure, the height of each bar denotes the average cluster level of a sub-industry. The red line (Cluster Level = 1) represents the industry average. The average levels of AMCs in the Manufacturing of Raw Chemical Materials and Chemical Products (C26), Manufacturing of Medicines (C27), and Manufacturing of Automobiles (C36) all exceed 1, indicating that these industries have significant development advantages for cluster development. The average levels in the Manufacturing of Railway, Ship, Aerospace, and Other Transport Equipment (C37) are close to 1, indicating that cluster development in these sub-industries is approaching the average level of advanced manufacturing cluster development. The average cluster levels of AMCs in other sub-industries remain low.

Figure 3.

Average level of AMCs by sub-industry (2013–2023).

4.2. Baseline Regression Analysis

Multicollinearity problems were first examined. For each explanatory variable, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was below 10, with an average of 1.86 and a maximum of 2.66. This suggests that there are no serious multicollinearity problems among the variables. The Hausman test was then used to determine whether random effects or fixed effects were more appropriate. Since the results rejected the null hypothesis at the 1% significance level, fixed effects were chosen for the regression. Due to regional differences such as industrial foundations and resource endowments, these individual features that do not change over time may exert potential influence on the study outcomes. The accuracy of research findings may also be affected by time-varying common shocks. For example, in 2023, the emphasis on “placing AMCs at the forefront” has driven changes in macro policy orientation, market settings, and other aspects. Therefore, the two-way fixed effects model was chosen for the subsequent regression analysis. Concurrent F-tests yielded a p-value of 0.0000, further validating the appropriateness of the two-way fixed effects model.

The baseline regression results are reported in Table 3. Column (1) shows that, without adding other control variables, the impact coefficient of NQPFs on AMCs is 0.3324 and significant at the 5% level. This suggests that NQPFs have a positive influence on AMCs, offering preliminary support for hypothesis 1. Columns (2) through (5) sequentially included the four control variables, with one added in each subsequent column: urbanization level (Urb), financial development level (Fin), social consumption level (Sum), and openness level (Open). That is, Column (2) includes the first control variable, Column (3) adds the second on top of the first, and so on until Column (5) incorporates all four. Ultimately, the influence coefficient of NQPFs on AMCs is 0.4984, which is significantly positive at the 1% level. This indicates that, assuming all other variables remain constant, every unit increase in NQPFs level can result in a 0.4984 unit increase in AMCs level. Assuming all other variables remain constant, for every 1-unit increase in the level of NQPFs, the level of AMCs increases by 0.4984 units. The regression results show that the coefficient of the impact of NQPFs on AMCs remains positive and passes the 1% significance test in all cases, thus confirming hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

Baseline regression results.

4.3. Endogeneity Tests

Considering the potential for reverse causality and omitted variables, this paper adopts the approach of Zhang et al. (2020) [67]. It used the spherical distance from each provincial capital to Hangzhou as an instrumental variable for NQPFs to test for endogeneity. As a frontier for developing NQPFs, Hangzhou’s practical experience and development model have influenced surrounding regions and even the entire nation. This influence creates a significant negative correlation between the development of NQPFs across provinces and the spherical distance from Hangzhou, satisfying the correlation condition.

The exogeneity of the spherical distance from each provincial capital to Hangzhou must be justified. To begin with, to satisfy the exclusion constraint, this study must show that this distance has no direct impact on AMCs through omitted variables, such as infrastructural levels. Zhejiang is one of several provinces in China with relatively high infrastructure. Thus, a greater distance from Hangzhou does not necessarily indicate lower infrastructure, supporting the plausibility of the exogeneity assumption. While provinces closer to Hangzhou, such as Jiangsu, generally have stronger infrastructure, this potential bias is mitigated by the two-way fixed effects model, which includes province and year fixed effects, thereby controlling for time-invariant regional characteristics and national trends. Moreover, time-varying control variables, including Urb, Fin, Sum, and Open, are included to capture observable, evolving aspects of each province’s economic development and infrastructure. These steps reduce the influence of omitted variables and mitigate potential spurious associations between geographic distance and AMCs. Therefore, after these adjustments, the spherical distance from each provincial capital to Hangzhou is treated as sufficiently exogenous.

Since the spherical distance from each provincial capital to Hangzhou forms cross-sectional data, this paper follows the method of Nunn & Qian (2014) [68]. It uses the interaction term between this distance and the average level of NQPFs across all other provinces (excluding the province in question) as the instrumental variable (IV). The regression results are shown in Table 4. The results show that the instrumental variable passes both the underidentification and weak identification tests, indicating that the choice of instrumental variable for NQPFs is valid. The coefficient on the impact of NQPFs on AMCs remains significantly positive, suggesting that, even after accounting for endogeneity, NQPFs continue to promote the development of AMCs.

Table 4.

Endogeneity test results.

4.4. Robustness Tests

To further verify the reliability of the research results, this paper used four methods to conduct robustness tests: sample winsorization, replacing the explained variables, replacing the core explanatory variables, and excluding municipal samples.

4.4.1. Sample Winsorization

To reduce the potential impact of outliers on research conclusions, all variables were winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels. The results after re-regression are shown in Column (1) of Table 5. The impact coefficient of NQPFs on AMCs is 0.5889 and significant at the 1% level, indicating that NQPFs can positively and significantly promote the development of AMCs, thus verifying the robustness of the regression results.

Table 5.

Robustness test results.

4.4.2. Substitution of Explained Variable

Drawing on the research by Devereux et al. (2004) [69], the Herfindahl Index (HI) method was adopted to calculate the AMCs’ levels of each province during the sample period. The regression results after replacing the explained variable are shown in Column (2) of Table 5. The impact coefficient of NQPFs on AMCs is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that NQPFs continue to have a significant positive effect on the development of AMCs.

4.4.3. Substitution of Core Explanatory Variable

From the perspective of systems theory [70], NQPFs are considered to stem from the synergy of three elements: laborers, labor objects, and means of labor. The coupling coordination model is used to remeasure the level of NQPFs. The regression results after replacing the core explanatory variable are shown in Column (3) of Table 5. The impact of NQPFs on AMCs remains significantly positive, thus reaffirming the robustness of the baseline regression.

4.4.4. Excluding Municipalities

Considering the uniqueness of the four municipalities in terms of NQPFs and AMCs levels, the sample data for Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing were excluded to avoid potential bias. After re-estimation, the results are shown in column (3) of Table 5. The impact coefficient of NQPFs on AMCs is 0.4627 and is significant at the 1% level, further strengthening the robustness of the baseline regression results.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

Previous regression results have demonstrated that NQPFs can significantly promote the development of AMCs. However, differences in regional geography, resource conditions, and other factors may affect the promotive effect of NQPFs. Therefore, this paper conducted group regressions based on geographical location, resource endowment, and industrialization level to examine the heterogeneous impact of NQPFs on the development of AMCs.

4.5.1. Geographical Location Heterogeneity

Given that the influence of NQPFs on China’s AMCs may vary across regions, this paper divided the 30 provinces in the sample into coastal and inland areas. The regression results are shown in Table 6. The results indicate that the enabling effect of NQPFs on AMCs in coastal areas is significantly stronger than that in inland regions. The stronger performance of coastal areas can be attributed to their greater openness, more advanced market mechanisms, and higher concentration of technological innovation resources. These factors facilitate the integration of NQPFs into the manufacturing system, enabling industrial clusters to progress toward high-end development. In contrast, while inland regions also exhibit some positive effects, their impact is comparatively weaker. This disparity is likely due to the inland regions’ slower pace of opening to external markets, lower concentration of high-end resources, and slower transformation and upgrading of industrial structures.

Table 6.

Heterogeneity analysis results.

4.5.2. Resource Endowment Heterogeneity

Resource endowment is crucial for regional manufacturing growth. Variations in resource endowments can influence how NQPFs affect AMCs. According to Shi & Shi (2024) [71], this study used the average production of raw coal, crude oil, and natural gas for each province during the sample period as a reference. It classified the top 10 provinces by total production as resource-based regions and the remaining provinces as non-resource-based regions. The regression results are presented in Table 6. Findings show that the impact of NQPFs on AMCs is significantly positive in non-resource-based areas but not in resource-based regions, indicating that resource endowments limit the promotion of NQPFs on AMCs.

This may be due to the long-term reliance of resource-based regions on resource development, resulting in over-concentration of factor allocation at the front end of the industrial chain and an insufficient supply of knowledge-intensive factors required for NQPFs. In contrast, non-resource-based regions have built stronger technology-absorption capacity through industrial diversification, making them more conducive to the transformation and application of NQPFs. Furthermore, deficiencies in environmental regulation intensity and the stock of highly skilled talent in resource-based regions further weaken the marginal contribution of NQPFs to cluster development.

4.5.3. Industrialization Level Heterogeneity

The promotive effect of NQPFs on AMCs may vary due to differences in industrialization levels. Referring to the research of Luo & Huang (2024) [72], this paper used the average proportion of industrial value in the regional gross product across provinces during the sample period as a reference, defining the top 15 regions ranked by this average proportion as highly industrialized regions, and the remaining as less industrialized regions. The regression results are shown in Table 6. The results indicate that the promotive effect of NQPFs on AMCs is more pronounced in highly industrialized areas, while it has no significant impact in less industrialized regions.

This may be because highly industrialized regions have their complete manufacturing systems and well-developed innovation ecosystems, which allow them to more effectively absorb NQPFs and, in turn, promote the development of AMCs. In contrast, less industrialized regions may lack the necessary industrial foundation and innovation environment, making it difficult to fully capitalize on NQPFs. Furthermore, enterprises within clusters in highly industrialized regions are more sensitive to changes in market demand, leveraging NQPFs to enhance product competitiveness and service quality, thereby satisfying consumers’ pursuit of personalization.

4.6. Mechanism Analysis

Based on the previous theoretical analysis, the study posits that technological innovation (TEC), talent agglomeration (TAG), and industrial structure advancement (ADV) mediate the process by which NQPFs foster the development of AMCs. To verify these hypotheses, the mechanism of action was tested using the mediating effect model constructed earlier. The test results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Mechanism analysis results.

Columns (1) to (2) report the test results of TEC. The impact coefficients of NQPFs on imitative innovation (IMIT) and independent innovation (IND) are both significantly positive. This indicates that NQPFs can effectively prompt IMIT and IND. According to existing theories, TEC serves as the core driving force for AMCs to overcome development bottlenecks and achieve iterative upgrading. Specifically, IMIT enables AMCs to rapidly absorb cutting-edge technological achievements in the industry and reduce innovation trial-and-error costs. Meanwhile, IND promotes clusters to break through barriers in key core technologies and establish a technological system with independent intellectual property rights, thereby forming a differentiated competitive advantage. Consequently, NQPFs can foster the development of AMCs by prompting IMIT and IND. That is, hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

Column (3) reports the test results of TAG. The coefficient of the impact of NQPFs on TAG is significantly positive, indicating that NQPFs can effectively facilitate TAG. At the same time, the existing literature also notes that TAG can accelerate knowledge and technology exchange among enterprises within the cluster. It can also exert the scale effect and collaborative innovation [73]. Therefore, NQPFs can foster the development of AMCs by facilitating TAG. That is, hypothesis 3 is verified.

Column (4) reports the test results of ADV. The impact coefficient of NQPFs on ADV is significantly positive, indicating that NQPFs can effectively drive ADV. In turn, ADV can optimize the industrial layout of clusters, guide the agglomeration of factors toward high-end manufacturing fields, and enhance the competitiveness of cluster industrial chains. Therefore, NQPFs can foster the development of AMCs by driving ADV. That is, hypothesis 4 is verified.

4.7. Further Analysis

The realization of NQPFs’ dividends necessitates governmental support. Government intervention contributes positively through policy guidance, resource integration, and market regulation. Conversely, inadequate intervention may impede the effectiveness of NQPFs. As the influence of NQPFs on AMCs may exhibit nonlinear characteristics contingent on the degree of government intervention, this study employs a threshold-effect model [74,75,76], using government intervention as the threshold variable in the empirical analysis:

In Equation (5), represents the piecewise indicator function; represents the threshold value; represents the threshold variable of the government intervention degree. , , , and represent impact coefficients. This study used the ratio of local public budget expenditure to regional GDP to measure government intervention.

First, the existence and number of threshold effects were assessed. Following 300 bootstrap resampling iterations, the government intervention level passed the single-threshold test, with a threshold p-value of 0.0100, which is significant at the 5% level. The dual-threshold and triple-threshold tests were insignificant. Thus, the single-threshold model was selected, with a threshold of 3.8324. The regression results for the threshold effect are presented in Table 8. When the degree of government intervention is below 3.8324, the impact coefficient of NQPFs on AMCs is 0.4123, significant at the 1% level. When the degree of government intervention exceeds the threshold value, the impact coefficient increases to 4.6522 and remains significant at the 1% level. This substantial increase in the regression coefficient suggests that greater government intervention strengthens the driving effect of NQPFs on AMCs.

Table 8.

Threshold effect regression results.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This paper examines the impact of NQPFs on AMCs from a theoretical perspective and conducts empirical analysis using provincial panel data from China from 2013 to 2023. The main findings are: (1) NQPFs have a marked positive impact on the development of AMCs. This conclusion remains robust after robustness tests, including the endogeneity test, sample winsorization, substitution of the explained variable, substitution of the core explanatory variable, and exclusion of municipalities. (2) NQPFs indirectly promote AMCs through technological innovation (including imitative and independent innovation), talent concentration, and industrial structure advancement. (3) The impact of NQPFs on AMCs varies by location, resource endowment, and industrialization. The effect is stronger in coastal areas than in inland areas. NQPFs have a significant impact in non-resource-based or highly industrialized regions, but no significant effect in resource-based or less industrialized areas. (4) The influence of NQPFs on AMCs is nonlinear when considering government intervention, and the effect becomes stronger after a certain threshold is crossed. These findings offer significant theoretical insights and practical guidance for promoting AMCs through NQPFs.

Theoretically, the research integrates NQPFs and AMCs within a unified analytical framework. It systematically identifies three primary pathways of impact: prompting technological innovation, attracting high-end talent, and driving advancements in industrial structure. Furthermore, the study reveals that the influence of NQPFs exhibits significant heterogeneity across regions, resource endowments, and industrialization levels, as well as a nonlinear threshold effect under conditions of government intervention. These findings enhance the theoretical understanding of how NQPFs drive industrial transformation and provide new insights into the complex interactions at play.

At the practical and policy level, this study confirms NQPFs as a key driver of AMCs, offering actionable insights in three main areas. First, tailored policy support should be strengthened to foster the three key pathways identified in this research: technological innovation, talent agglomeration, and industrial structure advancement. Second, policies must fully account for regional heterogeneity in location, resource endowment, and industrialization. Innovation ecosystem building should be prioritized in regions where NQPFs are most effective (such as coastal, non-resource-based, highly industrialized), while others may focus on foundational improvements like infrastructure and diversification. Third, given the nonlinear role of government intervention, policymakers should adopt adaptive governance, intensifying support once certain thresholds are reached to amplify the impact of NQPFs.

In terms of sustainable development and broader applicability, manufacturing upgrades driven by NQPFs represent a shift toward green, intelligent, and efficient practices. This shift facilitates decoupling economic growth from resource and environmental constraints. It makes them valuable references for other emerging economies facing similar industrial upgrading challenges. By adapting policy tools, regional implementation sequences, and cross-sectoral coordination mechanisms to their specific endowments and institutional contexts, these countries can effectively foster their own NQPFs and enhance national industrial competitiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and W.Z.; methodology, J.W.; software, W.Z.; validation, J.W. and W.Z.; formal analysis, J.W.; investigation, W.Z.; resources, J.W.; data curation, W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.W. and W.Z.; supervision, J.W. and W.Z.; project administration, J.W. and W.Z.; funding acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Project of Philosophical and Social Sciences Research in Jiangsu Universities (2025SJZD035), the Project of the National Statistical Science Research Program (2023LY072), and the General Project of the 24th Batch of University Students’ Scientific Research Project Approval of Jiangsu University (Y24C014).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, Z.; Rayman-Bacchus, L.; Wu, Y. Self-organization of industrial clustering in a transition economy: A proposed framework and case study evidence from China. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 1280–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, E.B.; Uygun, Y. Strengthening advanced manufacturing innovation ecosystems: The case of Massachusetts. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 134, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, M. Unpacking the Provision of the Industrial Commons in Industry 4.0 Cluster. Eco. Bus. Rev. 2019, 5, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T.; Okazaki, T.; Tomiura, E. Industrial Cluster Policy and Transaction Networks: Evidence from Firm-level Data in Japan. Can. J. Econ. 2022, 55, 1990–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.X.; Yan, M. New Quality Productive Forces and New Industrialization: Dialectical Relationship, Mutual Promotion Mechanism and Coordinated Advancement Strategy. Economist 2025, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Q. Impact of Digital Transformation in Agribusinesses on Total Factor Productivity. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2024, 27, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ding, X.; Chen, M.; Song, H.; Imran, M. The Impact of Resource Spatial Mismatch on the Configuration Analysis of Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity. Agriculture 2025, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Xu, L.Y. On New Quality Productivity: Connotative Characteristics and Important Focus. Reform 2023, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.L. Political Economy Interpretation of New Quality Productive Forces. Stud. Marx. 2024, 3, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Cui, H.Y. On New Quality Productivity from the Perspective of Historical Materialism: Connotation, Formation Conditions and Effective Paths. J. Chongqing Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 30, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L. Scientifically Understanding New Quality Productive Forces from the Perspective of Historical Materialism. J. Yunnan Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 24, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.H.; Sheng, F.F. New Productive Forces System: Factor Characteristics, Structural Bearing and Functional Orientation. Reform 2024, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Qiao, L.; Zhu, G.; Di, K.; Zhang, X. Research on the Driving Factors and Impact Mechanisms of Green New Quality Productive Forces in High-Tech Retail Enterprises under China’s Dual Carbon Goals. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, R.J. New Quality Productivity: Index Construction and Spatiotemporal Evolution. J. Xi’an Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 37, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Gu, T.; Shi, Y. The Influence of New Quality Productive Forces on High-Quality Agricultural Development in China: Mechanisms and Empirical Testing. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, X. Can New Quality Productive Forces Promote Inclusive Green Growth: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1499756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, W.; Hongrui, Z. Research on the Impact of Cost of Equity Capital on Firm New Quality Productive Forces in China. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2025, 36, 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, K. Research on the Measurement and Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics of New Quality Productive Forces in China’s Marine Economy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1497167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Yin, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, M. The Impact Pathway of New Quality Productive Forces on Regional Green Technology Innovation: A Spatial Mediation Effect Based on Intellectual Property Protection. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Y. Green Revolution vs. Digital Leap: Decoding the Impact of Environmental Regulation on New Quality Productive Forces in China’s Yangtze River Basin. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, P.; Wang, X.; Ran, R.; Wu, W. New Energy Policy and New Quality Productive Forces: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on Demonstration Cities. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 1670–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Sun, G.L. Data Elements and New Quality Productive Forces: A Perspective from Total Factor Productivity of Enterprises. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2024, 44, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Lu, W. Heterogeneity Analysis of the Effects of New Quality Productive Forces on Ecological Resilience in the Yangtze River Delta Economic Belt. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Lai, H.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L.; Lai, X. Does Public Data Openness Accelerate New Quality Productive Forces? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.N.; Xin, N. International Experiences and Policy Recommendations of China’s Advanced Manufacturing Clusters under Global Production Networks. Intertrade 2019, 5, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrian, P.; Mulhern, C. From Metal Bashing to Materials Science and Services: Advanced Manufacturing and Mining Clusters in Transition. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.L. Accelerating the Cultivation of China’s World-Class Advanced Manufacturing Clusters. Academics 2019, 5, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.G.; Liu, J.J.; Cao, H.W. Research on Competition Diffusion of the Multiple-Advanced Manufacturing Mode in a Cluster Environment. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2013, 64, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Q.; He, C.Q.; Xia, G.J. Advanced Manufacturing Cluster in Jiangsu: Embedding, Dynamic Capabilities and Enterprise Innovation Performance. East China Econ. Manag. 2019, 33, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Q.; Huang, P.P.; Cai, W.J.; Wang, Y.Y. Knowledge Spillover and the Growth of Advanced Manufacturing Cluster Enterprises—A Study on the Mediating Effect of Enterprise Innovation Correlation. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2022, 40, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Guo, J.J. Patterns of Technological Learning within the Knowledge Systems of Industrial Clusters in Emerging Economies: Evidence from China. Technovation 2011, 31, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.Y.; Cheng, P.F. Reconstructing the Global Value Chain and Fostering the World-Class Advanced Manufacturing Clusters. Huxiang Forum 2019, 32, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.L.; Zhou, L.H.; Han, M. FDI, Technological Innovation, and Advanced Manufacturing Clusters Development in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. East China Econ. Manag. 2024, 38, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Luo, W. Research on the Development Strategy of Advanced Manufacturing Cluster from the Perspective of Collaborative Innovation—Based on the Empirical Evidence of Changzhou Advanced Manufacturing Cluster. China Bus. Mark. 2021, 35, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciech, D.; Valentina, M.D. On the Road to Industry 4.0 in Manufacturing Clusters: The role of Business Support Organisations. Compet. Rev. 2022, 32, 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. Governance Path of the Digital Innovation Ecosystem in Advanced Manufacturing Cluster: A Case Study of China’s Tai-Xin Integrated Economic Zone. Kybernetes 2024, 54, 7302–7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.W. Exploration of New Quality Productive Forces Empowering the Green Transformation of the Manufacturing Industry. Financ. Account. Mon. 2024, 45, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.G.; Wang, Z.Q. New Quality Productivity and Manufacturing Industry Chain Supply Chain Resilience: Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Test. J. Henan Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 52, 29–42+2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.L.; Guo, T.Z.; Zhang, P.J. Research on the Impact of New Quality Productivity on the International Competitiveness of China’s Manufacturing Industry—A Moderated Mediation Effect Model Test Based on Human Capital Upgrading. Dongyue Trib. 2025, 46, 72–81+191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatica-Neira, F.; Ramos-Maldonado, M.; Andrés Ascua, R.; Revale, H.; Fernández, V. Digital Technologies 4.0 in Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturing Industries: Cases of the Central Region of Argentina and the Biobío Region of Chile. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H. How are Knowledge Dissemination and Innovation Performance Created in Manufacturing Firms? The Case of the Korea Innovation Survey (KIS). Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2025, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Fisher, R.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Santibañez Gonzalez, E.D.R. Green and Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Platform Economy. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 25, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J. Schumpeter and the Revival of Evolutionary Economics: An appraisal of the literature. J. Evol. Econ. 2003, 13, 125–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Zheng, Y. The New Quality Productive Force, Science and Technology Innovation, and Industrial Structure Optimization: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hwang, S.J.; Yoon, W. Industry Cluster, Organizational Diversity, and Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2023, 7, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Vanhaverbeke, W. The Influence of Scope, Depth, and Orientation of External Technology Sources on the Innovative Performance of Chinese Firms. Technovation 2011, 31, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Link, A.N. Employment in China’s High-Tech Zones. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Adler, P.; Mellander, C. The City as Innovation Machine. Reg. Stud. 2017, 51, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Resseger, M.G. The Complementarity Between Cities and Skills. J. Reg. Sci. 2010, 50, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breschi, S.; Lissoni, F. Knowledge Spillovers and Local Innovation Systems: A Critical Survey. Ind. Corp. Change. Ind. Corp. Change 2001, 10, 975–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M.E.; Stern, S. Clusters and Entrepreneurship. J. Econ. Geogr. 2010, 10, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, M.S.; Zhong, S.C. The Influence of Manufacturing Agglomeration on Industrial Structure Upgrading in Resource-based Regions: A Case Study of Shanxi Province. Inq. Into Econ. Issues 2020, 2, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Y.; Yang, S.Y. New Quality Productivity and Advanced Industrial Structure: Two-way Empowerment or One-way Drive. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.L.; Yao, Y.; Yang, C.C. Research on the Impact of Coupling Coordination Between the Digital Economy and Business Environment on Innovation Efficiency in High-Tech Industries. J. Hohai Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2025, 27, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 4754-2017; National Economic Industry Classification. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Tang, H.; Chen, M. Can the Chinese Cultural Consumption Pilot Policy Facilitate Sustainable Development in the Agritourism Economy? Agriculture 2025, 15, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, T.; Teng, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, R.; Guo, Z. Model Construction for Field Operation Machinery Selection and Configuration in Wheat-maize Double Cropping System. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Hui, N. Transformation of Innovation Mode and Financial Structure of China’s Manufacturing—Empirical Evidence from Chinese Provincial Panel Data. Econ. Surv. 2019, 36, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Y.J.; Zhu, J.H. Talent Introduction and Total Factor Productivity from the Perspective of New Quality Productivity Force. Bus. Manag. J. 2024, 46, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Li, J.Z. Determining Industry by Water: Fee to Tax of Water Resources and Industrial Transformation and Upgrading. Stat. Res. 2023, 40, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sarkar, A.; Rahman, A.; Hossain, M.S.; Memon, W.H.; Qian, L. Research on the Industrial Upgrade of Vegetable Growers in Shaanxi: A Cross-Regional Comparative Analysis of Experience Reference. Agronomy 2022, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T. Mediating Effects and Moderating Effects in Causal Inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z. A Study on the Utilization Rate and Influencing Factors of Small Agricultural Machinery: Evidence from 10 Hilly and Mountainous Provinces in China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, S.K. Digital Economy, Entrepreneurship, and High-Quality Economic Development: Empirical Evidence from Urban China. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Gong, J.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M. Cost Comparison between Digital Management and Traditional Management of Cotton Fields—Evidence from Cotton Fields in Xinjiang, China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Wang, G.H. Digital Finance and Household Consumption: Theory and Evidence from China. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, N.; Qian, N. US Food Aid and Civil Conflict. American Economic Review 2014, 104, 1630–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, M.P.; Griffith, R.; Simpson, H. The Geographic Distribution of Production Activity in the UK. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2004, 34, 533–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.C.; Wei, Y.D.; Zhang, F.Y. China’s New Quality Productivity: Development Level and Dynamic Evolution Characteristics. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.Y.; Shi, D.M. Green Finance: An Effective Way to Break the “Carbon Curse”. Stat. Res. 2024, 41, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Huang, W. Coordinating Economic Growth and Environmental Protection: From the Perspective of the Emissions Abatement Effect of the Decline in Trade Policy Uncertainty. Financ. Econ. 2024, 45, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.M.; Chai, C.X. Research on the Effect of Innovative Talent Agglomeration on the Development of High Quality Economy—Empirical Analysis Based on 41 Urban Panel Data in Yangtze River Delta. Soft Sci. 2022, 36, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhong, K.; Zhang, D.; Shi, B.; Wang, H.; Shi, J.; Battino, M.; Wang, G.; Zou, X.; Zhao, L. The Enhancement of the Perception of Saltiness by Umami Sensation Elicited by Flavor Enhancers in Salt Solutions. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xing, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wang, J.; Mao, R. Effects of Low-Phosphorus Stress on Use of Leaf Intracellular Water and Nutrients, Photosynthesis, and Growth of Brassica napus L. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Hu, J.; Liu, C.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. An Experimental Study on the Charging Effects and Atomization Characteristics of a Two-Stage Induction-Type Electrostatic Spraying System for Aerial Plant Protection. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.