Abstract

This study creates and refines a risk–effectiveness–integrated dynamic simulation framework that brings together risk and effectiveness factors affecting qualified workforce allocation in multi-project contexts, specifically in the construction of industrial production facilities. Based on a case study of three overlapping projects in West Java, Indonesia, this study examines the requirements for an expert workforce across the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) phases. Conventional mitigation measures generally assume that a qualified expert workforce is immediately available. However, hiring the right personnel with specific qualifications for a project takes time. To fill this gap, this paper presents a system dynamics-based model that explicitly integrates quantified project risks and execution effectiveness to determine expert workforce requirements at the multi-project level. This aspect is often addressed implicitly in the existing workforce planning approaches. This mixed-methods strategy includes a literature review, variable validation, simulation modeling, and case analysis. The results show that workforce planning based on integrated risk and effectiveness factors significantly improves project delivery by anticipating expert workforce shortages and reducing the need for reactive solutions. Model validation using real project data demonstrates that the simulated expert workforce demand reproduces both the average behavior and variability observed in real-world practice, satisfying quantitative behavioral validation criteria across projects and the EPC phases. The model contributes to sustainability by enhancing long-term workforce resilience, reducing resource waste, and supporting more efficient industrial project delivery.

1. Introduction

Innovation and product development are crucial to addressing production needs in an organization’s daily operation while supporting long-term organizational sustainability. These things ensure that an organization stays in business and becomes more competitive. Projects are activities planned to achieve innovation or development within a specified time and resource limits [1,2]. These undertakings need practical resources and good time management to be successful [1]. Many organizations commonly undertake projects to address internal needs [3,4] and fulfill strategic objectives [3,5], such as enhancing efficiency, creating new products, and adapting to changing market and regulatory demands [6]. Projects aimed at diversifying products or meeting current requirements may result in the development of industrial production facilities, thereby affecting the company’s operational strategy [7,8]. The project life cycle represents a series of steps from start to finish [9,10]. It provides project leaders with an organized method to ensure projects move forward and achieve their goals within defined execution and resource constraints [5,10,11,12]. The first stage is the feasibility assessment, during which the business case is analyzed to assess the project’s viability in relation to scope, resources, and execution risk [13]. The subsequent phase involves planning and organization to coordinate activities, resources, and responsibilities. This ensures the organization is prepared to achieve its objectives by establishing a management framework, forming teams, and allocating resources. Engineering, construction, and testing are important parts of the implementation process that require coordinated expert workforce involvement. They ensure that the project’s deliverables meet quality requirements before they are handed over. The closure phase formally ends the project by documenting all the deliverables and ensuring that the organization receives the intended benefits from an operational and resource perspective. This project life cycle framework can be used in several ways, including in sequential order and with overlapping phases. Its practical application depends on the complexity and uniqueness of each project, particularly in terms of resource coordination and execution dynamics. There are three primary project types: infrastructure, building, and industrial [14]. Human resources are significant for industrial initiatives, especially those involving the construction and development of production facilities [7]. The main factor in determining whether a project will be successful is having qualified personnel [10]. An expert team is essential during the engineering phase, as they turn project requirements into a clear scope of work. Experts plan, analyze, and monitor the acquisition of goods and equipment during procurement [9]. During the construction and installation phase, a team of experts is responsible for planning, reviewing, supervising, and testing to ensure that every work item meets the project’s quality requirements [15]. In a multi-project setting, where projects may develop simultaneously, overlap, or run one after the other, it becomes harder to manage them due to dynamic workforce demand and execution uncertainty [4,16,17,18,19]. There are numerous ways to manage the building of production facilities in industrial construction projects. The project owner may manage the project themselves, utilizing their own resources [1,16,18,20]. Another method is to hire consultants to help with planning, design, supervision, and implementation. The project owner would then contract the vendors and subcontractors directly [21]. A third option is to hire a main contractor to complete the entire project under a lump sum or EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction) contract. The contractor takes on all the project’s risks. This study focuses on the execution phase of industrial construction projects, during which the project owner is tasked with hiring consultants to supervise implementation and provide expert the workforce with resources. These professionals are used throughout various phases, including planning, engineering, procurement, construction, and the setup of production facilities [22]. In this situation, one of the most significant problems is accurately planning and assigning an expert workforce, especially when multiple projects are underway simultaneously or overlap, which makes the required workforce dynamic and difficult to anticipate [4,16,17]. When there are differences between the planned and actual demand for an expert workforce, shortages often occur, affecting project timelines and outcomes [1]. Project owners relying on external expert workforce contractors face inherent constraints related to availability, qualification specificity, and timing alignment, which have direct implications for project sustainability and long-term resource efficiency [4,21]. To address these challenges, this study presents a predictive and adaptive modeling approach grounded in system dynamics that integrates quantifiable project risks and execution effectiveness into a feedback loop to support sustainable expert workforce planning. This system enables organizations to dynamically predict the needs of their expert workers and make better decisions across multiple projects. This research also contributes to the broader sustainability discourse by linking human–capital planning to industrial resource efficiency. Sustainable project management requires not only minimizing environmental and financial waste but also ensuring the long-term availability and effectiveness of expert personnel, a vital yet often neglected component of organizational sustainability.

This study contributes to the literature by introducing a dynamic risk–effectiveness workforce allocation model designed explicitly for multi-project EPC environments. Unlike the existing system dynamics approaches, the proposed framework integrates interactions across overlapping projects and incorporates execution effectiveness as a dynamic modifier of expert man-hour requirements. These aspects are typically simplified or absent in the existing workforce planning models that assume isolated or static project conditions. The framework is strengthened through validation using real historical project data, resulting in more adaptive and accurate workforce estimates than those of the conventional static methods.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Multi-Project Environment

A multi-project environment occurs when an organization works on multiple related projects simultaneously. Managing multiple projects differs fundamentally from managing a single project [16]. This complexity creates challenges in workforce assignments, such as achieving an appropriate balance between workloads and project lifespans [1,18]. Numerous studies have underscored the essential function of resource and personnel management in ensuring the efficacy of multi-project management [23]. Construction projects frequently encounter numerous unique complications, especially in multi-project environments, including the following: (1) meeting expectations and getting the attention of senior management; (2) clearly defining what a multi-project environment is; (3) effectively managing shared resources; (4) setting up and keeping an integrated scheduling system; (5) ensuring good communication and coordination across projects; and (6) managing the risks that come up when conducting multiple projects at once [17]. Projects may differ significantly in complexity and quality, and they are often tied to one another [16]. This can also refer to situations in which one organization works on multiple initiatives simultaneously, even if they are not immediately related. In this managerial setting, there are unique problems, such as allocating resources, coordinating teams, and maintaining standards across projects [16].

In summary, the descriptions of multi-project settings as provided in prior research generally cover the following aspects: (1) organizational activities that involve doing several projects at the same time, whether or not these projects are related [16,19,22]; (2) projects that use intangible resources, such as ideas and innovation, but are limited by physical resources that change over time, which requires accurate scheduling and coordination [1,16]; (3) the management of multiple projects within a company at the same time, which often includes planning and optimizing at the portfolio level [16,19]; and (4) organizational and operational conditions in which several projects are carried out either at the same time or one after the other, depending on the company’s strategic and capacity needs [1,16]. Under multi-project conditions, resource flows, risk interactions, and effective feedback loops constantly change and affect one another. Understanding these interdependencies is the first step toward building a system-based model that supports adaptive decision making to deploy an expert workforce across multiple projects simultaneously.

2.2. Risk and Dynamic Systems in Industrial Development Project

Risk could either advance or impede a project’s goals [24,25]. In project management, they can affect the schedule, budget, and quality of a product or service [26]. Risk analysis entails assessing the likelihood of a risk occurring and how it could affect a project’s goals, which in turn requires the use of suitable control measures [24]. Modeling and simulation can improve this analysis, particularly by using a system dynamics approach. This method helps capture the complex and changing nature of risks in project environments [27]. System dynamics is a strategy used for analyzing and managing complex, changing systems. It involves creating and using simulation models [28,29]. This method, which was first developed in the late 1950s, was initially used to evaluate industrial systems [30].

In construction and project management, system dynamics modeling helps tackle challenges that involve (1) complex systems with many interconnected parts and (2) dynamic ones defined by processes that include feedback loops [31]. Industrial projects relate to building or renovating facilities that support industrial activities. This includes commercial production facilities and buildings, which might be used to process or manufacture raw materials into final products. These projects include a variety of facility types, such as production, power, and chemical plants and refineries, along with their related components [14]. Building industrial facilities requires a thorough approach encompassing planning, design, construction, operation, and maintenance. These procedures must follow the existing technical and environmental regulations. This study combines risk analysis and system dynamics to examine how uncertainty and feedback loops shape the need for an expert workforce in industrial development initiatives. This approach provides a foundation for a practical system innovation framework.

3. Methodology

The technique applied in this research combines literature analysis with a case study approach to address issues in multi-project management, specifically within the construction industry. This study identifies and validates critical variables affecting project execution by integrating qualitative and quantitative methodologies, particularly through the allocation of expert personnel in multi-project settings [4,28]. Based on this approach, the methodological steps followed in this study are outlined in the subsequent sections.

Initially, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify relevant and valid variables from previous studies. Thereafter, these variables were examined through questionnaires distributed to experts and practitioners pertinent to the research focus. The verified variables highlighted the underlying study issues, which were further confirmed by field observations from different ongoing construction projects. Risk and effectiveness variables were confirmed through structured expert judgment and validated using standard reliability and construct assessment procedures applied to expert questionnaire responses, where each identified risk variable was operationalized as a model construct and subsequently linked to a normalized numerical index derived from historical probability–impact–based project risk assessment data, with probability and impact values obtained from recorded project execution data reflecting observed historical conditions rather than subjective expert scoring, ensuring that the variables incorporated into the dynamic model were both conceptually sound and empirically grounded for use in system dynamics simulation rather than for statistical inference.

Case studies were employed throughout the project life cycle to support model development and validate both the conceptual structure and the simulation results.

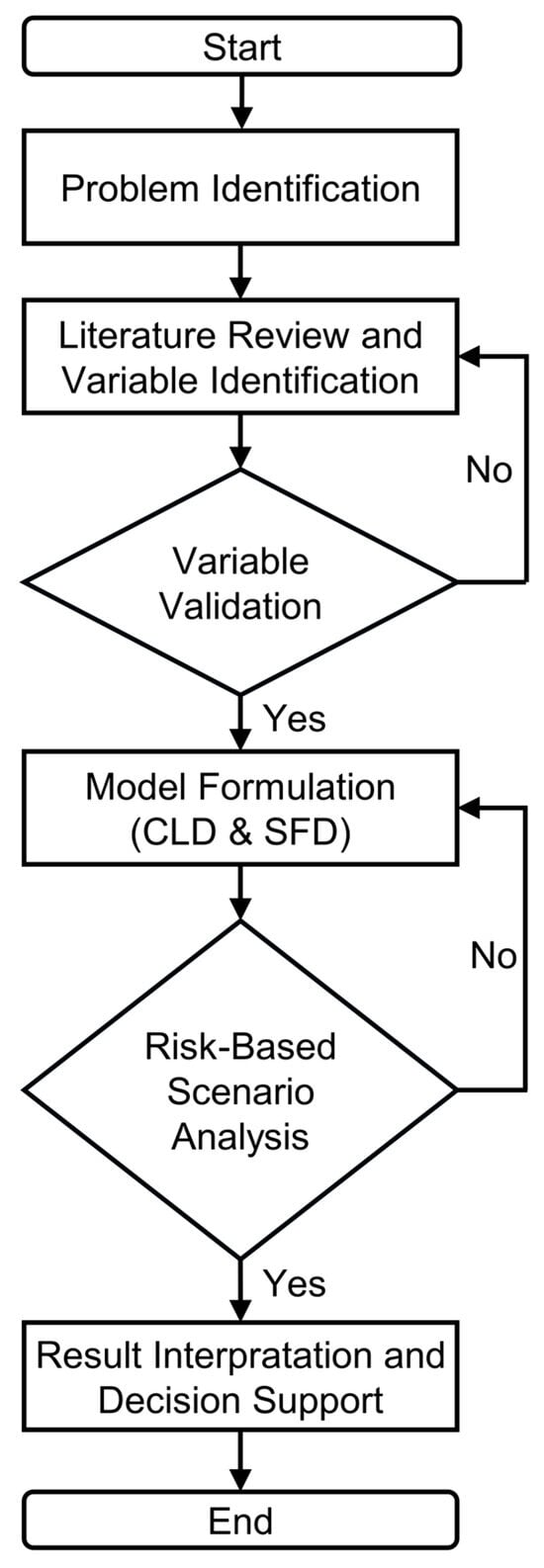

Building on this variable identification process, the study then followed a structured, sequential workflow consisting of four main stages. First, relevant risk and effectiveness variables were identified through a comprehensive literature review and subsequently validated through expert input and field observations. Second, a conceptual system model was developed using Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) to illustrate feedback relationships, followed by stock–flow diagrams (SFDs) to represent the dynamic accumulation of expert man-hours. Third, the simulation model was parameterized using historical project data along with validated risk and effectiveness indices, expressed as dimensionless values ranging from 0 to 1 to represent relative risk intensity and execution effectiveness. Finally, the model was validated using Barlas’ (1989) multi-test framework [32], including structural consistency checks and behavioral reproduction tests. This staged methodology provides a transparent and replicable basis for developing and evaluating the proposed dynamic workforce allocation model.

Within this framework, Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) were used to capture and feedback mechanism linking expert workforce demand, project-level risks, multi-project interactions, and execution effectiveness. Stock and Flow Diagram (SFDs) were subsequently developed to translate the causal structure into a quantitative, time-dependent model. The stock–flow formulation enables explicit representation of expert workforce accumulation, backlog formation, and corrective workforce responses as project conditions, quantified risk exposure, and execution effectiveness evolve across the EPC phases.

Model validation was performed across the EPC phases using data from previous projects to estimate expert workforce man-hours requirements. The model was subsequently applied in scenario-based risk analysis to evaluate the influence of different risks and effectiveness inputs on workforce demand over time.

This analysis identified key factors affecting expert workforce requirements, including resource availability, organizational structure, environmental conditions, external influences, design complexity, and technical challenges [6,7].

To summarize the overall methodological flow, as illustrated in Figure 1, the research methodology follows a structured sequence linking variable identification, model development, simulation, and validation to support expert workforce planning in multi-project environments [28]. This approach was created to simulate and improve the allocation of expert personnel in environments across multiple projects. It provides a structured approach to efficiently deploy expert workforce resources [28,29,32].

Figure 1.

Research flow diagram.

A stock–flow system dynamics structure is employed as the expert workforce demand represents an accumulative process that evolves over time as the project conditions, quantified risk exposure, and execution effectiveness change across the EPC phases. Static or linear methods cannot capture these feedback-driven adjustments in multi-project environments. The use of a stock–flow formulation allows for the explicit representation of backlog accumulation and corrective workforce responses, while maintaining a transparent and tractable model structure.

In multi-project settings, when several projects are underway at the same time, a specific method is required to track how the need for expert workforce resources evolves over time, especially when it pertains to the risks encountered in project execution [17,33]. These risks may vary in intensity and impact throughout the project life cycle, and they may coincide, affecting the overall demand for experts [24,25,34,35,36,37,38,39]. The model adopts a conservative representation that reflects the dominant risk’s influence on expert workforce demand. System dynamics is used to address these complex, continually evolving situations. This modeling technique enables to determine and adapt the number of expert workers needed across multiple projects, which is beneficial for allocation when risk profiles change [27,28].

Sensitivity and uncertainty were examined by varying key model parameters, including the risk and effectiveness indices, within their standard deviation ranges to observe the changes in expert workforce demand over time. Model robustness was evaluated using Barlas’s behavioral validation framework, focusing on reproducing observed workforce behavior [32]. In this context, validation assessed the consistency between the simulated and actual data in terms of average behavior and variability using mean and amplitude comparison tests.

4. Result

This case study examined three chemical-process-based production facility projects in West Java, Indonesia. These facilities, commonly referred to as processing plants, were used during the project implementation phase, which includes planning, detailed engineering design, procurement, construction, and installation. The combined scope of work covers Projects A, B, and C, as shown in Table 1, which outlines the overall effort required to complete each project from engineering to commissioning.

Table 1.

Volumes of work for EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction).

To clarify the rationale for selecting the empirical cases, the three projects included in this study were not chosen merely based on convenience. Rather, they were selected because they represent typical industrial EPC projects commonly undertaken in Indonesia. All three were run by a multinational project owner with mature governance structures and delivered by top-tier Indonesian EPC contractors, ensuring high data reliability and professional execution standards. Their scale, complexity, and EPC configuration align with the industry norms for chemical production facilities, making them representative cases for validating the proposed dynamic workforce allocation model and enhancing the external validity of the findings. This clarification strengthens the empirical foundation of this study and supports the validity of the model evaluation presented in the following sections.

The expert workforce is responsible for performing work during the planning and engineering phases in accordance with the project owner’s requirements and specifications. The group of experts works across many fields, including civil and architectural, mechanical and piping, electrical and instrumentation, and process control engineering and project management [20,21]. During the procurement phase, the expert personnel are responsible for planning and acquiring materials and equipment for the production facility that comply with the project’s design specifications. During construction and installation, the expert workforce is crucial to ensuring the work proceeds according to the plans developed during the engineering phase. Table 2 shows the estimated man-hours of the expert workforce on the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) phases. All the numbers are given in man-hours.

Table 2.

Estimated total expert workforce allocation (man-hours) by project phase.

Figure 2 presents a histogram showing the relationship between the number of man-hours assigned to a project and the cost required to complete it. This figure also shows how the demand for an expert workforce is spread across the different phases. The findings show that the engineering phase has the most demand for expert personnel across all projects. The phrase “expert mh” refers to the total number of expert man-hours, and “cost” denotes the project’s total cost. Both these numbers have been adjusted to 100%.

Figure 2.

Distribution of expert workforce man-hours and project cost across EPC phases.

Each organizational unit assigned to a project is responsible for planning and providing its respective expert workforce man-hour loading, as illustrated in Figure 3 for Project A. Within a multi-project management framework, the project owner supervises and coordinates the overall allocation of expert workforce man-hours across all ongoing projects.

Figure 3.

Distribution of planned expert workforce man-hours in Project A.

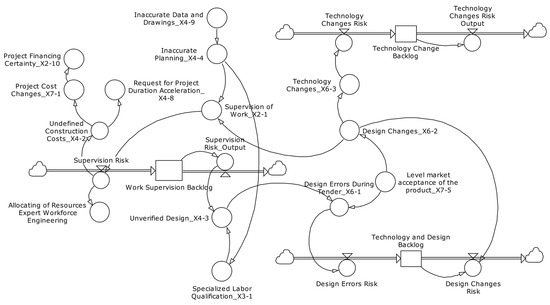

Risks affecting the demand for expert workers’ hours emerge at both the project and multi-project levels. Modeling these demands at both these levels improves the ability to identify potential expert shortages throughout project execution. Field observations and a literature review were conducted to identify relevant risk variables and evaluate the effectiveness of multi-project implementation. These variables were then validated statistically based on the feedback from construction professionals. Figure 4 presents a simplified Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) that illustrates the interrelationships among expert workforce man-hour demand, multi-project effectiveness, and project-level and multi-project risks.

Figure 4.

Simplified Causal Loop Diagram (CLD).

Table 3 lists the main risk variables that affect expert workforce man-hour allocation, particularly during engineering-related activities. The risk index values quantify factors such as the degree of supervision and adoption of new technologies; higher scores indicate greater effects on the number of man-hours required. The level of supervision is a crucial factor that directly affects the additional man-hours needed to mitigate project risks. These indices represent the relative risk intensity derived from probability–impact–based project risk assessments conducted during project execution and subsequently normalized for use as inputs to the simulation model.

Table 3.

Risks affecting required expert man-hours for engineering work.

Figure 5 depicts a Stock and Flow Diagram (SFD), demonstrating the impact of accumulated risks on the distribution of expert workforce man-hours in engineering operations. By capturing the cumulative effect of engineering-related risks through reinforcing feedback loops, key variables such as supervision levels and technology changes dramatically increase the demand for an expert workforce.

Figure 5.

Stock and Flow Diagram (SFD) representing risk factors influencing expert workforce allocation during engineering work.

Besides engineering-related risks, the quality of contractor performance could impact the allocation of expert workforce man-hours. Factors including environmental conditions, changes in labor regulations, and delays in contractor payments are incorporated into a risk index that measures the possible escalation in necessary man-hours. A higher score signifies a bigger potential impact, especially in multi-project contexts where stakeholder collaboration is essential. The engineering phase model accurately delineates the effect of accumulated risks on the allocation of expert personnel through supervision levels, technological changes, and feedback loops. The analytical methodology utilized here can be extended to both the procurement and construction phases, adopting the same modeling principles.

The dynamic model reveals that quality and coordination risks significantly influence workforce requirements through rework and process inefficiencies. Higher rework and coordination risks increase the additional workforce demand needed to manage inter-project interactions and stakeholder alignment. In contrast, effective multi-project coordination improves allocation efficiency by minimizing losses. A dynamic system model was developed to determine the optimal allocation of expert man-hours during the engineering phase. The model consists of two simulated scenarios, as shown in Figure 6. In Scenario 1, the estimated expert workforce assumes a static allocation model, in which expert resources are immediately available from the market whenever shortages occur. This reflects a simplified assumption that an expert workforce can be mobilized on demand, leading to minimal change in the overall workforce profile over time.

Figure 6.

Stock and Flow Diagram (SFD) comparing Scenarios 1 (static expert allocation) and 2 (risk–effectiveness dynamic allocation). This figure illustrates how project risk, multi-project effectiveness interact to generate dynamic expert workforce man-hour requirements over time.

Scenario 2, on the contrary, employs a dynamic modeling technique that leverages the quantifiable risk and effectiveness variables created in this study. As risks arise and effective values evolve, the needs of the expert workforce change throughout the project. As a result, the entire allocation of experts to the workforce expands over time, including changes that may not be obvious when employing solely an estimated expert workforce without dynamic modeling. In the real world, insufficient workers might affect the timing, scope, quality, and cost of a project. It also combines multi-project maturity by continually changing workforce demands based on risk and effectiveness feedback.

The simulation integrates the three-phase categories—Engineering (E), Procurement (P), and Construction (C)—within this EPC framework to reflect how functional risks influence man-hour requirements across the phases, resulting in a distinct quantitative impact distributed throughout the EPC process, with uncertainty and delay parameters, as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Simulation parameters influencing expert workforce man-hours across Engineering, Procurement, and Construction phases.

The simulation results reflect real-world conditions by integrating quantified risk and effectiveness factors as mitigation inputs to estimate expert workforce man-hour requirements. Figure 7 illustrates how this method compares the real project data with the expert workforce need over time for both situations. Scenario 2 incorporates additional man-hours as risks change and effectiveness of the multi-project; however, Scenario 1 projects workforce demands without accounting for effectiveness or risk. The third curve in Figure 7 shows the actual data from Project A (2021–2023), validating the simulation results.

Figure 7.

Expert workforce man-hour demand for engineering design work of Project A.

The simulation results show how Scenarios 1 and 2 diverge from the actual man-hour data across the project timeline. Scenario 2 aligns more closely with the real-world variations, confirming its suitability as a reliable simulation-based method for estimating expert workforce requirements. Model validation was performed by comparing the simulation outputs with the actual historical data, as summarized in Table 5. This comparison evaluates the model’s consistency with real engineering man-hour patterns from 2021 to 2023. Further detailed validation for procurement and construction phases following the same modeling approach is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 5.

Comparison of expert workforce man-hour demand for engineering phase (Scenario 2 versus actual).

Following Barlas [32], two validation criteria were applied. First, the model’s average monthly allocation of expert workforce man-hours was compared with the actual values, and the model was considered valid when the deviation was within ±5%. Second, data variation was assessed by comparing the standard deviation of simulated and actual allocations; deviations within ±30% were considered to be valid.

These validation results provide direct evidence addressing the research objectives introduced earlier. The dynamic simulation demonstrates that project risk factors generate fluctuating expert workforce requirements across the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction phases, highlighting their influence on man-hour demand over time. In addition, the inclusion of execution effectiveness factors in Scenario 2 modifies both the magnitude and timing of projected expert workforce requirements, illustrating how execution conditions shape workforce needs in multi-project environments. Furthermore, the close alignment between Scenario 2 and the actual project data—evaluated using Barlas’ (1989) [32] behavioral validation criteria for average behavior and variability—indicates that the proposed risk–effectiveness dynamic model reproduces observed workforce patterns more reliably than the conventional static estimation approaches.

From a managerial perspective, the comparison between the static and dynamic scenarios highlights important implications for expert workforce planning in multi-project environments. The static scenario assumes immediate availability of expert resources and therefore tends to underestimate expert workforce shortages and their timing, potentially leading to reactive staffing decisions, schedule pressure, and inefficiencies during project execution. In contrast, the dynamic scenario enables project owners and managers to anticipate risk-driven fluctuations in the demand for expert workforce, allowing earlier workforce mobilization, improved coordination across concurrent projects, and more informed trade-offs between resource availability, project priorities, and execution effectiveness. As a result, the dynamic approach provides practical decision support for proactive resource planning and enhances managerial control over expert workforce deployment in complex EPC environments.

The validation results confirm that the Scenario 2 model is valid and consistent with the actual project data, effectively supporting the entire man-hour estimation for the expert workforce as part of the overall risk mitigation and effectiveness strategy in multi-project environments. The validation structure refers to Barlas’ multiple-test framework to ensure both pattern and amplitude validity. Table 6 presents the results of the average error (<±5%) and amplitude error (<±30%) tests for Projects A, B, and C, demonstrating that the model’s behavior closely aligns with actual expert workforce utilization across the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction phases.

Table 6.

Validation model (Scenario 2).

The Scenario 2 results also indicate that expert workforce man-hours are required across the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction phases. Figure 8 shows this relationship, showing the expert workforce man-hours required for both the scenarios. Scenario 2 enables accurate estimation of the number and qualification level of experts needed, directly supporting risk mitigation and improving overall execution effectiveness.

Figure 8.

Expert workforce demand for multi-project implementation (Projects A, B, and C).

From a practical perspective, the proposed risk–effectiveness dynamic model provides structured decision support for expert workforce planning in multi-project EPC environments by translating routinely observed project execution conditions into time-dependent expert workforce demand profiles.

For project owners, the model supports portfolio-level planning by enabling earlier visibility of potential expert workforce shortages across overlapping projects. This facilitates proactive coordination, prioritization of critical activities, and informed engagement of external expert resources, thereby reducing reliance on reactive staffing once shortages materialize.

For EPC contractors, the framework provides a structured mechanism to align engineering, procurement, and construction workforce planning with evolving execution conditions. By accounting for risk-driven rework, coordination requirements, and variations in execution effectiveness, the model supports improved workload balancing across concurrent projects and strengthens managerial control over expert workforce deployment throughout the EPC life cycle.

The proposed model contributes to sustainable industrial operations by ensuring optimal allocation of scarce expert resources, minimizing backlog accumulation, and reducing the need for reactive staffing. This strengthens long-term workforce sustainability and supports more resilient project execution environments.

In this context, sustainable workforce allocation refers to the proactive provision of the right expert resources at the right time across the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction phases. By anticipating risk-driven fluctuations in workload, the proposed model helps minimize engineering rework, improve supervision quality during construction, and support timely procurement decisions. These mechanisms contribute to more stable project execution and reduced inefficiencies. Consequently, project cost control is strengthened, operational efficiency is improved, and execution effectiveness is enhanced through timely and appropriate expert deployment.

From a broader sustainability perspective, the findings align with established project sustainability frameworks that emphasize long-term capability development, efficient resource utilization, and organizational resilience. By reducing reactive staffing and stabilizing expert workforce deployment across concurrent projects, the model contributes to economic sustainability through efficiency gains and to social sustainability through improved workforce stability and resilience.

The integration of risk exposure and execution effectiveness into workforce planning aligns with sustainability principles that recognize human capital as a critical and finite organizational resource. By stabilizing expert workforce deployment and mitigating risk-driven workload volatility across concurrent projects, the model contributes to economic sustainability through efficiency gains and to social sustainability through enhanced workforce stability and resilience. Accordingly, expert workforce allocation is positioned as an integral component of sustainable industrial project delivery rather than a purely operational concern.

This model is based on several assumptions that should be acknowledged. The selected projects were executed under a consistent organizational and governance context with established project management practices and delivered by experienced EPC contractors, providing a consistent context for modeling expert workforce dynamics in industrial EPC environments. The model assumes relatively stable organizational maturity, governance structures, and workforce allocation practices. Consequently, applying the model to organizations or projects with substantially different maturity levels, governance arrangements, and execution approaches may require recalibration. In addition, the representation of risk interactions and effectiveness dynamics is necessarily simplified. It does not capture all the possible managerial or organizational responses, which should be considered when extending the model to different industrial contexts.

While the model was calibrated and validated using three chemical process EPC projects in West Java, the underlying dynamic mechanisms are broadly applicable to other industrial settings. Risk-induced fluctuations in Engineering, Procurement, and Construction workloads and effectiveness-driven adjustments represent behaviors commonly found in both greenfield and brownfield industrial developments. Therefore, the model can be transferred to other regions and industry sectors—including power generation, oil and gas, manufacturing expansions, and facility upgrades—by recalibrating the risk indices, adjusting the effectiveness profiles, and revising the baseline man-hour parameters to reflect the local project characteristics. Nevertheless, its generalizability remains influenced by contextual factors, such as organizational maturity, and data availability. These considerations define the boundaries within which the proposed framework can be reliably applied.

For practical implementation, users can follow a structured workflow consisting of the following: (1) defining the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction phases for the project or portfolio; (2) entering the baseline expert man-hour estimates; (3) applying validated risk and effectiveness indices as adjustment factors; and (4) running scenario simulations to identify workforce adjustments over time. The model boundaries, parameter definitions, and scenario inputs presented in this study allow practitioners to reproduce the model logic and apply it consistently across different EPC environments.

In multi-project settings, the dynamic modeling technique offers a valuable and thorough framework for evaluating risks and effectiveness and enabling the proactive, data-driven distribution of expert workforce resources.

5. Conclusions

This study emphasizes the importance of risk-based expert workforce allocation for multi-project management. A dynamic model that integrates risk analysis into the allocation process was developed to adjust workforce requirements in real time. Emerging risks, including poor supervision, rework, and differences in project management effectiveness, cause expert demand to shift across concurrent or overlapping projects. By precisely predicting and modifying allocations based on detected risk variables, the suggested methodology reduces the risk of expert workforce shortages that could interfere with project delivery. It also corrects the distribution of the expert workforce from the standpoint of multi-project execution effectiveness.

A system dynamics approach was employed to model expert workforce requirements across the design, procurement, and construction phases. This approach enables the prediction and adjustment of workforce needs in response to evolving risks and changing project conditions. In multi-project environments—where concurrent execution is common—timely and accurate workforce planning remains a significant challenge. Critical risk factors, such as supervision quality, design changes, and external influences, substantially affect workforce demand. The model was validated using real project data, demonstrating that a risk-based allocation strategy can minimize delays and enhance overall execution efficiency.

This study further highlights the significance of standardized management techniques in multi-project settings, including transparency of information, availability of resources, and project managers’ proficiency. The suggested approach anticipates future expert workforce shortages and dynamically adjusts allocations in response to new risks that arise during implementation. Real-world data validation confirmed that workforce planning that accounts for risk variables greatly enhances project outcomes. Therefore, by providing a systematic framework to reduce risks and improve execution effectiveness in multi-project, cross-industry situations, this study adds real value to construction activities in the industrial sector.

Although this research focuses primarily on industrial facility construction, particularly new or greenfield projects, its applicability extends beyond these contexts. The model can be adapted to brownfield projects by incorporating more complex risk factors and varying levels of implementation effectiveness influenced by site-specific conditions, regional dynamics, project types, and ownership structures. Future research should further examine the allocation of the skilled workforce in scenarios in which project owners directly contact the contractors. In industrial construction projects, synergy between experts and skilled workers is critical to achieving efficient, effective task execution. These two workforce groups play complementary roles in maintaining quality and meeting project timelines. Therefore, applying risk-based workforce allocation models for both expert and skilled workforces is essential for achieving optimal project outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010487/s1. Supporting information for “A Risk-Based System Dynamics Model for Sustainable Expert Workforce Allocation in Industrial Multi-Project Environments” is provided in the Supplementary File. This document includes the following elements: 1. Estimated expert workforce man-hours for multi-project implementation—Scenario 1 (Tables S1–S3); 2. Risk and effectiveness factors for EPC phases (Tables S4–S6); 3. Stock and Flow Diagram—SFD (Figures S1–S3); 4. Risk and effectiveness profiles over time (Figures S4–S7); 5. System dynamics model documentation (Tables S7–S9); and 6. Validation and simulation setup summary (Tables S10 and S11, Sections S6 and S7). These materials provide detailed model parameters, risk indices, effectiveness factors, and validation results supporting the findings presented in the main article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.S., S.W.A., and O.G.; methodology, S.B.S., S.W.A., and O.G.; software, S.B.S.; validation, S.B.S., S.W.A., and O.G.; formal analysis, S.B.S., S.W.A., and O.G.; investigation, S.B.S.; resources, S.B.S.; data curation, S.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.S.; writing—review and editing, S.B.S., S.W.A., and O.G.; visualization, S.B.S.; supervision, S.W.A. and O.G.; project administration, S.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Materials accompanying this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Engwall, M.; Jerbrant, A. The resource allocation syndrome: The prime challenge of multi-project management? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkova, N.; Tukkel, I. Specifics of multi-project management: Interaction and resource constraints. SHS Web Conf. 2017, 35, 01056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artto, K.; Kujala, J.; Dietrich, P.; Martinsuo, M. What is project strategy? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 26, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsuo, M.; Ahola, T. Multi-project management in inter-organizational contexts. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.K.; Slevin, D.P. Critical factors in successful project implementation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1987, EM-34, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.W.; Gray, C.F. Project Management: The Managerial Process, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lock, D. Project Management, 9th ed.; Gower Publishing, Ltd.: Aldershot, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tonchia, S. Industrial Project Management: Planning, Design, and Construction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kerzner, H. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling, 10th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ika, L.A. Project success as a topic in project management journals. Proj. Manag. J. 2009, 40, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 7th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.pmi.org/standards/pmbok (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Rand, G.K. Critical chain: The theory of constraints applied to project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2000, 18, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Müller, R. The project manager’s leadership style as a success factor on projects: A literature review. Proj. Manag. J. 2005, 36, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Construction Industry Institute (CII). Project Definition Rating Index (PDRI) Overview; Construction Industry Institute: Austin, TX, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.construction-institute.org/resources/knowledgebase/pdri-overview (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Leon, H.; Osman, H.; Georgy, M.; Elsaid, M. System dynamics approach for forecasting performance of construction projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04017063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.H. Management of multiple simultaneous projects: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1995, 13, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.M.; Vicridge, I.G. Best Practices for Multi-Project Management in the Construction Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, Manchester, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elonen, S.; Artto, K.A. Problems in managing internal development projects in multi-project environments. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanakul, P. Key drivers of effectiveness in managing a group of multiple projects. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2013, 60, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arivalagan, A. Industrial project management: Methods, issues and strategies. IPPTA J. 1998, 10, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Velde, R.R.; Van Donk, D.P. Understanding bi-project management: Engineering complex industrial construction projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2002, 20, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanakul, P.; Milosevic, D. The effectiveness in managing a group of multiple projects: Factors of influence and measurement criteria. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglander, A.; Hedberg, M. Handling Multi-Projects: An Empirical Study of Challenges Faced in Management. Master’s Thesis, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, M.; Grela, G. Project portfolio risk categorisation—Factor analysis results. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2022, 6, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. A classified bibliography of recent research relating to project risk management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1995, 85, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS 31100:2021; Risk Management: Code of Practice and Guidance for the Implementation of BS ISO 31000:2018. BSI Standards Publication: London, UK, 2021.

- Nasirzadeh, F.; Afshar, A.; Khanzadi, M. System dynamics approach for construction risk analysis. Int. J. Civil Eng. 2008, 6, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.; Liu, Y. A system dynamics model for risk analysis during project construction process. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.G. Managing and modeling project risk dynamics: A system dynamics-based framework. In Proceedings of the Fourth European Project Management Conference, London, UK, 6–7 June 2001; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J.W. Industrial Dynamics; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Sterman, J.D. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; Irwin McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barlas, Y. Multiple tests for validation of system dynamics type of simulation models. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1989, 42, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chang, S.; Castro-Lacouture, D. Dynamic modeling for analyzing impacts of skilled labor shortage on construction project management. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04019035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunbin, L.; Yunqi, L.; Shuke, L. Human resources risk element transmission model of construction project based on system dynamic. Open Cybern. Syst. J. 2015, 9, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F.; Sari, M.H.M.; Yousefi, V.; Falsafi, R.; Tamošaitienė, J. Project portfolio risk identification and analysis, considering project risk interactions and using Bayesian networks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micán, C.; Fernandes, G.; Araújo, M. Project portfolio risk management: A structured literature review with future directions for research. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2020, 8, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, H.; Robert, B.; Bourgault, M.; Pellerin, R. Risk management applied to projects, programs, and portfolios. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2009, 2, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taroun, A.; Yang, J.B.; Lowe, D. Construction risk modeling and assessment: Insights from a literature review. Built Hum. Environ. Rev. 2011, 4, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wideman, R.M. Project and Program Risk Management: A Guide to Managing Project Risks and Opportunities; Project Management Institute, Inc.: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.