Employees’ Intentions to Engage in Green Practices: A Multilevel Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective

Abstract

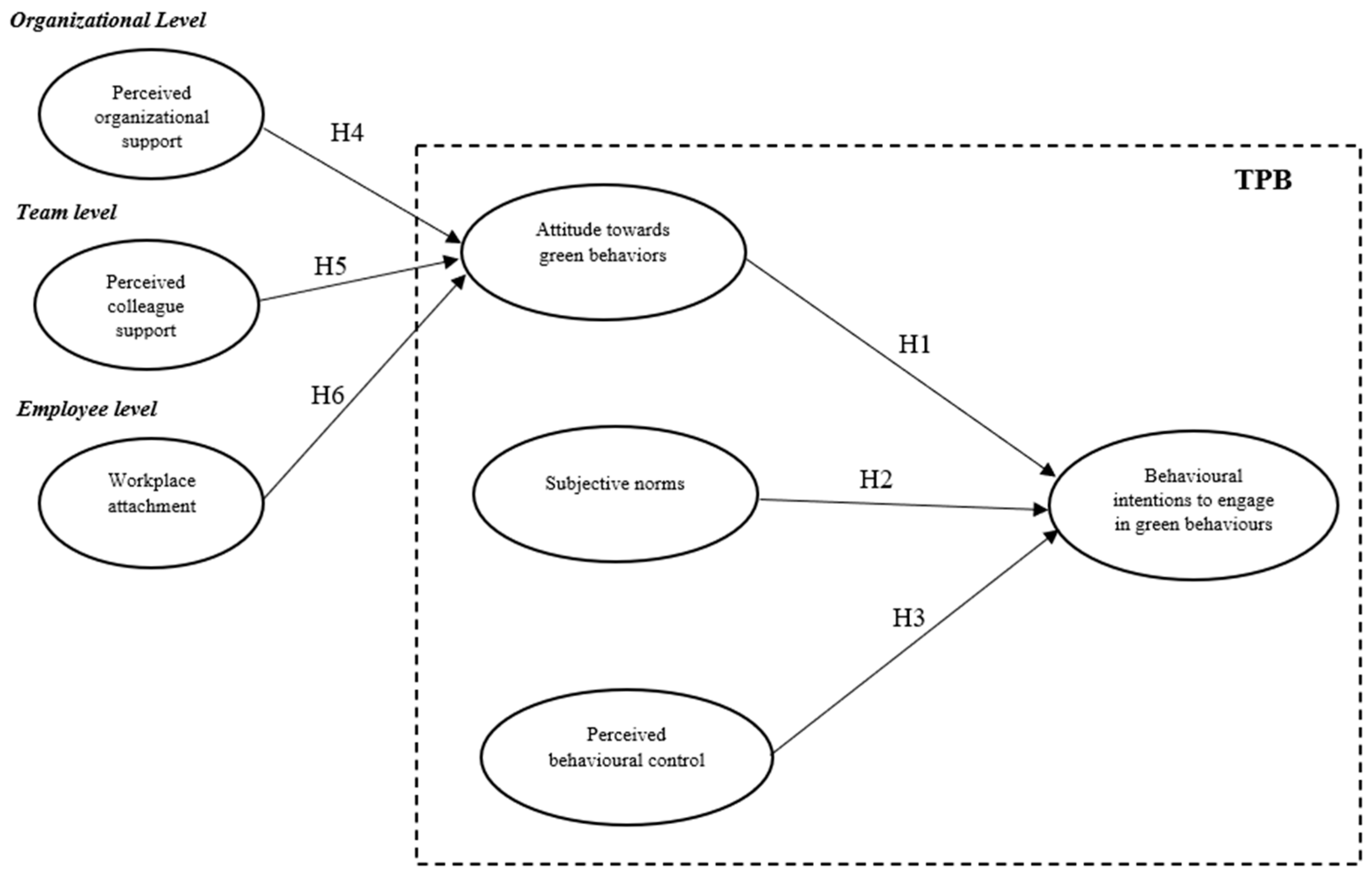

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Hypothesis Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Approach

3.2. Participants

3.3. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Outer Model Assessment

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implication

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonfanti, R.C.; Ruggieri, S.; Schimmenti, A. Psychological Trust Dynamics in Climate Change Adaptation Decision-Making Processes: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S.A.; Odhiambo, N.M. Enhancing Governance for Environmental Sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2021, 39, 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental Sustainability at Work: A Call to Action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee Green Behavior. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. The Relationship Between Pro-Environmental Attitude and Employee Green Behavior: The Role of Motivational States and Green Work Climate Perceptions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships Between Daily Affect and Pro-environmental Behavior at Work: The Moderating Role of Pro-environmental Attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kim, M.; Han, H.-S.; Holland, S. The Determinants of Hospitality Employees’ pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Moderating Role of Generational Differences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, C.L.Z.; Dubois, D.A. Strategic HRM as Social Design for Environmental Sustainability in Organization. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What Influences an Individual’s pro-Environmental Behavior? A Literature Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manika, D.; Wells, V.K.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Gentry, M. The Impact of Individual Attitudinal and Organisational Variables on Workplace Environmentally Friendly Behaviours. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 663–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkorezis, P.; Petridou, E. Corporate Social Responsibility and Pro-Environmental Behaviour: Organisational Identification as a Mediator. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2017, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Steger, U. The Roles of Supervisory Support Behaviors and Environmental Policy in Employee “Ecoinitiatives” at Leading-Edge European Companies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; De Young, R. Intrinsic Satisfaction Derived from Office Recycling Behavior: A Case Study in Taiwan. Soc. Indic. Res. 1994, 31, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.W.; Hon, A.H.Y. Application of Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Ecological Behavior Intentions in the Food and Beverage Service Industry. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2020, 23, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Mejía-Morelos, J.H. Antecedents of Pro-Environmental Behaviours at Work: The Moderating Influence of Psychological Contract Breach. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Abredu, P.; Kwasi Sampene, A.; Oteng Agyeman, F. Does Green Human Resource Management Stimulate Employees’ Green Behavior Through a Green Psychological Climate? Sage Open 2025, 15, 21582440241279274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, A.U.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y. The Psychological Benefits of Green HRM: A Study of Employee Well-Being, Engagement, and Green Behavior in the Healthcare Sector. Acta Psychol. 2025, 254, 104823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Activating Tourists’ Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: The Roles of CSR and Frontline Employees’ Citizenship Behavior for the Environment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1178–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Explore Environmental Behavioral Intentions in the Workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, B.; Shahzad, K.; Shafi, M.Q.; Paille, P. Predicting Required and Voluntary Employee Green Behavior Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1300–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, D.R.; Hadiyanto, H.; Hadi, S.P. Pro-Environmental Behavior from a SocialCognitive Theory Perspective. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 23, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Evaluating Determinants of Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intentions. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S. How Does Environmental Concern Influence Specific Environmentally Related Behaviors? A New Answer to an Old Question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, K.L.; Dmitrieva, A.; Adriasola, E. Changing Behaviour: Increasing the Effectiveness of Workplace Interventions in Creating Pro-environmental Behaviour Change. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, G.J.O.C.V.; O’Keefe, G.J. Intention to Conserve Water: Environmental Values, Planned Behavior, and Information Effects. A Comparison of Three Communities Sharing a Watershed. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2001, 14, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S.; Katz-Gerro, T. Predicting Proenvironmental Behavior Cross-Nationally. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S. Predicting Intention to Save Water: Theory of Planned Behavior, Response Efficacy, Vulnerability, and Perceived Efficiency of Alternative Solutions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 2803–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.A.; Finley, J.C. Determinants of Water Conservation Intention in Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 20, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Schmidt, P. Incentives, Morality, or Habit? Predicting Students’ Car Use for University Routes with the Models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Y.; Gifford, R. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: Predicting the Use of Public Transportation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 2154–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.; Steg, L. General Beliefs and the Theory of Planned Behavior: The Role of Environmental Concerns in the TPB. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1817–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; McDonald, R.; Louis, W.R. Theory of Planned Behaviour, Identity and Intentions to Engage in Environmental Activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-Environmental Behaviors Through the Lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Scoping Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Z. How to Facilitate Employees’ Green Behavior? The Joint Role of Green Human Resource Management Practice and Green Transformational Leadership. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashirun, S.N.; Noranee, S.; Hasan, Z. Theoretical Perspective on Employee Green Behavior. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Social. Sci. 2022, 12, 2782–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, D.E.; Morrow, P.C.; Montabon, F. Engagement in Environmental Behaviors Among Supply Chain Management Employees: An Organizational Support Theoretical Perspective. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2012, 48, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.M.; Rauvola, R.S.; Rudolph, C.W.; Zacher, H. Employee Green Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.S. Infant–Mother Attachment. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Retrospect and Prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornara, F.; Scopelliti, M.; Carrus, G.; Bonnes, M.; Bonaiuto, M. Place Attachment and Environment-Related Behavior. In Place Attachment; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C.; Devine-Wright, P. Place Attachment; Manzo, L., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; ISBN 9780429274442. [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K.; Kyttä, M.; Hartig, T. Restorative Experience, Self-Regulation, and Children’s Place Preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangunić, N.; Granić, A. Technology Acceptance Model: A Literature Review from 1986 to 2013. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green Purchasing Behaviour: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Investigation of Indian Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L. Sampling in Developmental Science: Situations, Shortcomings, Solutions, and Standards. Dev. Rev. 2013, 33, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osgood, C.E.; Suci, G.J.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Knight, K. Energy at Work: Social Psychological Factors Affecting Energy Conservation Intentions within Chinese Electric Power Companies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochwarter, W.A.; Kacmar, C.; Perrewé, P.L.; Johnson, D. Perceived Organizational Support as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Politics Perceptions and Work Outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, A.; Tennant, A.; Ching, A.; Parker, J.; Prior, Y.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Verstappen, S.M.M.; O’Brien, R. Psychometric Testing of the British-English Perceived Workplace Support Scale, Work Accommodations, Benefits, Policies and Practices Scale, and Work Transitions Index in Four Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Conditions. Musculoskelet. Care 2023, 21, 1261–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L. Construction d’une Échelle d’attachement Au Lieu de Travail: Une Démarche Exploratoire. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2006, 38, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J. Introducing LISREL; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 9780761951711. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Determinants of Employee Electricity Saving: The Role of Social Benefits, Personal Benefits and Organizational Electricity Saving Climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Gifford, R.; Vlek, C. Factors Influencing Car Use for Commuting and the Intention to Reduce It: A Question of Self-Interest or Morality? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.N.; Tarquinio, C.; Vischer, J.C. Effects of the Self-Schema on Perception of Space at Work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zoonen, W.; Banghart, S. Talking Engagement Into Being: A Three-Wave Panel Study Linking Boundary Management Preferences, Work Communication on Social Media, and Employee Engagement. J. Comput. -Mediat. Commun. 2018, 23, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L.; Pignault, A. Workplace Attachment and Meaning of Work in a French Secondary School. Span. J. Psychol. 2013, 16, E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Green Human Resource Practices and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: The Roles of Collective Green Crafting and Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, K.; Liu, W. Value Congruence: A Study of Green Transformational Leadership and Employee Green Behavior. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, H.; Knappstein, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P.; Kabst, R. How Effective Are Behavior Change Interventions Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior? Z. Psychol. 2016, 224, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the Gap Between Green Behavioral Intentions and Employee Green Behavior: The Role of Green Psychological Climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.34 | 10.74 | 0.952 | 0.792 |

| Attitude towards green behaviors | 22.3 | 4.94 | −0.603 | 0.332 |

| Subjective norms | 3.83 | 1.95 | −0.112 | −0.093 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 13.47 | 2.15 | 0.113 | 0.283 |

| Perceived organizational support | 29.97 | 5.37 | 0.115 | −0.402 |

| Perceived colleague support | 23.30 | 6.08 | 0.284 | −0.617 |

| Workplace attachment | 16.10 | 4.55 | 0.594 | −0.378 |

| Behavioural intentions to engage in green behaviours | 16.28 | 3.07 | −1.014 | 1.579 |

| Construct/Indicators | Outer Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtGB_1 | 0.931 | 0.91 | 0.979 | 0.870 |

| AtGB_2 | 0.941 | |||

| AtGB_3 | 0.936 | |||

| AtGB_4 | 0.937 | |||

| AtGB_5 | 0.920 | |||

| AtGB_6 | 0.927 | |||

| AtGB_7 | 0.937 | |||

| SN_1 | 0.815 | 0.77 | 0.798 | 0.663 |

| SN_2 | 0.814 | |||

| PBC_1 | 0.864 | 0.76 | 0.907 | 0.709 |

| PBC_2 | 0.767 | |||

| PBC_3 | 0.851 | |||

| PBC_4 | 0.881 | |||

| BIGR_1 | 0.912 | 0.965 | 0.958 | 0.851 |

| BIGR_2 | 0.924 | |||

| BIGR_3 | 0.933 | |||

| BIGR_4 | 0.920 | |||

| POS_1 | 0.922 | 0.923 | 0.983 | 0.879 |

| POS_2 | 0.953 | |||

| POS_3 | 0.945 | |||

| POS_4 | 0.944 | |||

| POS_5 | 0.931 | |||

| POS_6 | 0.929 | |||

| POS_7 | 0.933 | |||

| POS_8 | 0.942 | |||

| PCS_1 | 0.931 | 0.911 | 0.982 | 0.874 |

| PCS_2 | 0.941 | |||

| PCS_3 | 0.937 | |||

| PCS_4 | 0.937 | |||

| PCS_5 | 0.930 | |||

| PCS_6 | 0.937 | |||

| PCS_7 | 0.930 | |||

| PCS_8 | 0.937 | |||

| WA_1 | 0.916 | 0.935 | 0.976 | 0.855 |

| WA_2 | 0.914 | |||

| WA_3 | 0.935 | |||

| WA_4 | 0.923 | |||

| WA_5 | 0.926 | |||

| WA_6 | 0.943 | |||

| WA_7 | 0.917 |

| AtGB | SN | PBC | BIGR | POS | PCS | WA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtGB | 0.933 | ||||||

| SN | 0.198 | 0.814 | |||||

| PBC | 0.014 | 0.198 | 0.842 | ||||

| BIGR | 0.080 | 0.000 | 0.360 | 0.923 | |||

| POS | 0.236 | 0.026 | 0.489 | 0.620 | 0.938 | ||

| PCS | 0.204 | 0.119 | 0.088 | 0.135 | 0.308 | 0.935 | |

| WA | 0.136 | 0.236 | 0.162 | 0.116 | 0.231 | 0.246 | 0.925 |

| Relationship Direct Paths | β-Value | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude → Behavioural intention | 0.367 | 0.017 | 0.000 |

| Subjective norms → Behavioural intention | 0.057 | 0.035 | 0.222 |

| Perceived behavioural control → Behavioural intention | 0.369 | 0.032 | 0.000 |

| Perceived organizational support → Attitude | 0.399 | 0.087 | 0.000 |

| Perceived colleague support → Attitude | 0.323 | 0.043 | 0.003 |

| Workplace attachment → Attitude | 0.401 | 0.074 | 0.000 |

| Relationship Indirect paths | |||

| Perceived organizational support → Attitude → Behavioural intention | 0.132 | 0.012 | 0.000 |

| Perceived colleague support → Attitude → Behavioural intention | 0.149 | 0.011 | 0.003 |

| Workplace attachment → Attitude → Behavioural intention | 0.131 | 0.023 | 0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bonfanti, R.C.; Billeci, N.; Lavanco, G.; Ruggieri, S. Employees’ Intentions to Engage in Green Practices: A Multilevel Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Sustainability 2026, 18, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010486

Bonfanti RC, Billeci N, Lavanco G, Ruggieri S. Employees’ Intentions to Engage in Green Practices: A Multilevel Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010486

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonfanti, Rubinia Celeste, Nicolò Billeci, Gioacchino Lavanco, and Stefano Ruggieri. 2026. "Employees’ Intentions to Engage in Green Practices: A Multilevel Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010486

APA StyleBonfanti, R. C., Billeci, N., Lavanco, G., & Ruggieri, S. (2026). Employees’ Intentions to Engage in Green Practices: A Multilevel Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Sustainability, 18(1), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010486