1. Introduction

The accelerating pace of environmental degradation, coupled with persistent social inequalities, has fundamentally challenged conventional marketing paradigms that prioritize economic growth without accounting for ecological limits or societal welfare. Recent evidence confirms that sustainable marketing strategies have become essential for achieving environmental goals [

1]. Paradoxically, while companies increasingly adopt green marketing initiatives, approximately two billion people globally still lack access to basic needs, including safely managed drinking water [

2]. This presents a dual challenge: advancing environmental sustainability through premium-priced green products while ensuring affordable access to essential goods. This tension raises critical questions regarding whether marketing strategies can simultaneously address environmental protection and social accessibility objectives.

Saudi Arabia provides a particularly relevant context in which to examine this tension. Vision 2030 represents a systematic attempt to reconcile economic diversification with environmental stewardship and social development—objectives that create both opportunities and tensions for marketing practices. The Kingdom’s specific targets—50% renewable energy by 2030, 95% waste diversion from landfills, and universal access to quality services [

3]—necessitate fundamental changes in marketing systems. Recent evidence from the Al-Jouf region demonstrates that integrating knowledge economy principles with sustainable development goals yields measurable progress [

4].

However, the Saudi market presents unique challenges shaped by structural and organizational factors. Recent studies highlight how technological innovation, organizational culture, and Industry 4.0–enabled governance mechanisms influence sustainability-oriented practices within Saudi firms, particularly in manufacturing and strategic management contexts [

5,

6]. While 84% of the population resides in cities with efficient infrastructure [

7], income disparities raise questions about whether sustainable products with price premiums can achieve inclusive market penetration [

8,

9].

This study addresses a critical gap. Prior research on sustainable marketing has largely focused on green branding, consumer behavior, and the effectiveness of environmental marketing strategies in shaping purchase decisions [

10], as well as the credibility and communication of sustainability performance and the risk of perceived greenwashing [

11]. Other studies have examined green marketing applications in specific service sectors, such as healthcare, and their implications for responsibility and access [

12], or evaluated the efficiency of green innovation and marketing strategies for achieving long-term environmental sustainability [

13]. However, despite the growing implementation of sustainable marketing initiatives, no empirical research has examined their simultaneous impact on environmental sustainability and basic accessibility needs. The dominant research stream examines these outcomes in isolation [

14], preventing an understanding of potential trade-offs. For instance, green product strategies may reduce environmental impacts while failing the affordability requirements for lower-income segments.

Two research questions guide this investigation:

How do sustainable marketing strategies (green product development, sustainable pricing, sustainable promotion, and sustainable distribution) influence access to basic needs and environmental sustainability in Saudi Arabia?

What mediating role does Consumer Experience Perception (CEP) play in translating sustainable marketing strategies into environmental and social outcomes?

Consumer Experience Perception emerges as a critical yet under-examined mediating construct. Recent work on sustainable business models emphasizes the role of digitally enabled governance and secure user management mechanisms in supporting sustainable value creation and user engagement [

15]. Marketing capabilities influence business sustainability primarily through enhanced consumer experiences rather than through direct effects [

16], suggesting that sustainable marketing strategies require experiential validation before producing tangible outcomes. Service-dominant logic supports this mediating relationship by positioning value as co-created through firm–consumer interactions [

17]. Empirical evidence from emerging economies further indicates that trust and corporate reputation play a central mediating role in translating sustainability-oriented and CSR-driven initiatives into competitive advantage, reinforcing the importance of experiential and relational mechanisms in market responses [

18]. In the Saudi context, where digital transformation rapidly reshapes consumer touchpoints while traditional consumption patterns persist, understanding CEP’s mediating role becomes essential.

Furthermore, Saudi Arabia’s institutional environment, shaped by the Vision 2030 reforms, including carbon pricing mechanisms and water tariff reforms [

19], fundamentally alters market conditions. These factors potentially influence how consumers perceive and respond to sustainable marketing initiatives, although their specific effects remain unempirically examined.

This study makes three distinct contributions to sustainable marketing theory and practice. First, it provides the first empirical examination of how marketing strategies simultaneously affect environmental and social outcomes in an emerging market context, moving beyond the isolated analysis that characterizes existing research. Second, it identifies and tests Consumer Experience Perception as the mechanism by which marketing strategies translate into societal benefits, addressing the “black box” problem in sustainability research. Third, it examines these relationships within Saudi Arabia’s unique transformation context, where rapid modernization meets traditional values, offering insights for other emerging markets that pursue ambitious sustainability agendas.

For practitioners, the findings reveal which marketing strategies effectively balance environmental protection with social accessibility, thus enabling more informed resource allocation. For policymakers, the results demonstrate how market-based mechanisms complement regulatory interventions to achieve Vision 2030′s dual objectives. The study ultimately questions whether sustainable marketing can deliver “win-win” outcomes or whether organizations must make explicit trade-offs between environmental and social goals.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study adopted a quantitative cross-sectional survey design to examine the relationships between sustainable marketing strategies, consumer experience perception, and dual sustainability outcomes. While cross-sectional designs limit causal inference, this approach was selected to capture the current market dynamics during Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 transformation period. The design enabled the simultaneous measurement of predictor, mediator, and outcome variables, facilitating the analysis of both direct and indirect pathways through structural equation modeling. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to establish causality and to track the evolution of sustainable marketing effectiveness over time.

3.2. Sampling and Participants

The target population consisted of Saudi Arabian consumers with direct experience in purchasing or using products marketed as sustainable within the preceding 12 months. While this experiential criterion ensured the relevance and validity of respondents’ evaluations, it may have excluded lower-income segments with limited access to sustainable products, representing a potential limitation that is acknowledged in the discussion.

The sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula for unknown populations. This calculation yielded a minimum sample of 384 participants, based on a 95% confidence level, a 5% margin of error, and a population variability estimate of 0.5. Although this sample size represents approximately 0.001% of the Saudi Arabian population and thus limits broad generalizability, it satisfies established methodological requirements for PLS-SEM analysis [

33,

34,

35]. Moreover, the achieved sample exceeds the commonly cited guideline of a minimum of ten observations per indicator variable [

35], providing adequate statistical power to test the hypothesized relationships.

Geographic stratification attempted to enhance representativeness across the six administrative regions. However, 54.7% of the participants came from Riyadh (29.2%) and Makkah/Jeddah (25.5%), creating an urban bias that limits applicability to rural populations where basic needs accessibility is most critical. The data collection produced 384 valid responses, and

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics. The overrepresentation of educated (69.0% bachelor’s degree or higher) and middle-income respondents (57.8% earning SAR 5000–15,000) further constrains generalizability to vulnerable populations.

The age distribution reflected Saudi Arabia’s youth demographics, with 53.1% under 35 years, although this may overrepresent early adopters of sustainable consumption. Gender representation (59.9% male, 40.1% female) approximated workforce participation patterns but may not reflect household purchasing decision-makers.

3.3. Instrumentation

Table 2 presents all measurement items with their sources.

Green Product Development items (GPD1-GPD4) assessed environmental attributes, resource efficiency, recyclability, and certification, adapted from Khan et al. [

21] and Wasiq et al. [

2]. Sustainable Pricing items (SPC1-SPC4) measured affordability, value perception, fairness, and accessibility, based on Adam et al. [

8]. Sustainable Promotion items (SPM1-SPM4) looked at how clear, trustworthy, educational, and culturally appropriate the content was, based on Hasnin [

27] and Alharthey [

25]. Sustainable Distribution items (SDB1-SDB4) assessed availability, accessibility, convenience, and environmental efficiency, following Acheampong et al. [

26].

Consumer Experience Perception items (CEP1-CEP4) measured satisfaction, trust, emotional connection, and behavioral intention, synthesized from Hanaysha and Al-Shaikh [

16]. The outcome variables maintained parallel, four-item structures for consistency.

Pilot testing with 45 consumers refined the item wording and confirmed its cultural appropriateness. All constructs demonstrated Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.850 and 0.879, exceeding the 0.70 threshold.

3.4. Data Collection

Data collection proceeded through mixed-mode administration between January and March 2025. The mixed approach aimed to reach diverse demographics, although online distribution (60% of responses) may have excluded digitally marginalized populations. Face-to-face collection occurs at shopping centers and public spaces, potentially missing homebound individuals or those in remote areas.

The Scientific Research Ethics Committee gave the study the go-ahead (Approval No. 7 March 2025). All participants provided informed consent after receiving information regarding the research objectives, voluntary participation, and withdrawal rights. No incentives were offered, which may have influenced participation patterns toward those with an intrinsic interest in sustainability.

3.5. Data Analysis

The study employed partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) rather than covariance-based SEM for three reasons: (1) the exploratory nature of examining simultaneous environmental and social outcomes, (2) the complex model with multiple mediating relationships, and (3) the focus on prediction rather than theory confirmation [

35]. The data were analyzed using SmartPLS software (version 4.0; SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt, Germany).

The initial data screening addressed missing values (<3% per variable, replaced through mean substitution), outliers (retained after verification), and response patterns. The absence of control variables (education, income, and region) represents a limitation, as these factors likely influence both sustainable marketing exposure and outcome perceptions.

The two-step analytical approach assessed:

Measurement Model:

- ▪

Internal consistency: Cronbach’s α and composite reliability > 0.70

- ▪

Convergent validity: Average Variance Extracted (AVE) > 0.50

- ▪

Discriminant validity: Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT < 0.85

- ▪

Indicator reliability: Outer loadings > 0.70

Structural Model:

- ▪

Path coefficient significance via bootstrapping (5000 resamples)

- ▪

R2 values for endogenous constructs

- ▪

Effect sizes (f2) were assessed using established guidelines for interpreting small, medium, and large effects.

- ▪

Q2 values for predictive relevance using blindfolding procedure

Mediation analysis was conducted by distinguishing full mediation (significant indirect effects with non-significant direct effects) from partial mediation (both direct and indirect effects being significant). Common-method bias was assessed using Harman’s single-factor test, with no single factor explaining more than 40% of the variance.

Model fit indices (SRMR < 0.08, NFI > 0.90) have been reported despite ongoing debates regarding their applicability in PLS-SEM. Multicollinearity diagnostics confirmed that all variance inflation factors were less than 5.0.

4. Results

The descriptive statistics (

Table 3) indicate satisfactory measurement properties across all constructs, with means ranging from 3.68 to 3.86 on a five-point scale, and Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.850 and 0.879, confirming robust reliability. Green Product Development showed the highest mean among the marketing strategies (M = 3.82, SD = 0.71), whereas Sustainable Pricing demonstrated the lowest (M = 3.68, SD = 0.76). Both outcome variables—Access to Basic Needs (M = 3.86) and Environmental Sustainability (M = 3.83)—exhibited higher means than the predictor variables, with Consumer Experience Perception intermediate at 3.78.

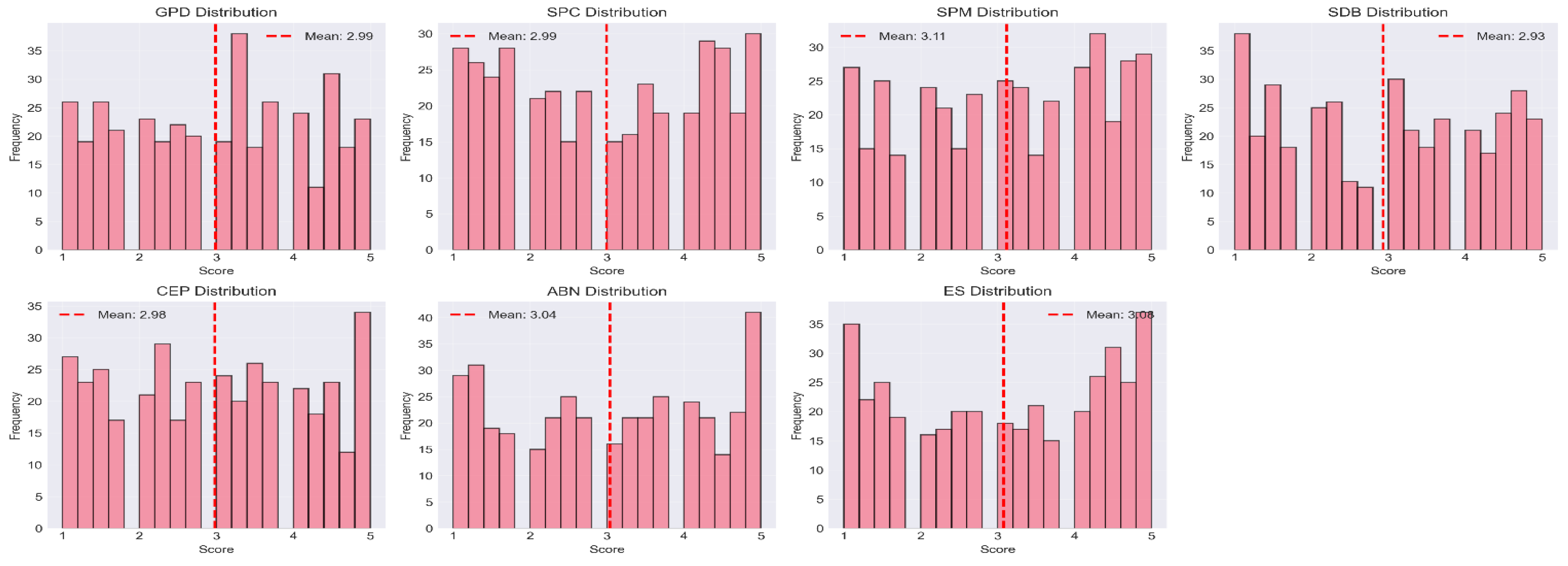

Distribution patterns (

Figure 2) confirmed negative skewness across all constructs, with responses concentrated toward higher-scale values. The histograms reveal approximately normal distributions despite left-skewing, with marketing strategy dimensions clustering around means of 2.93–3.11 and outcome variables showing slightly higher central tendencies (3.04–3.06).

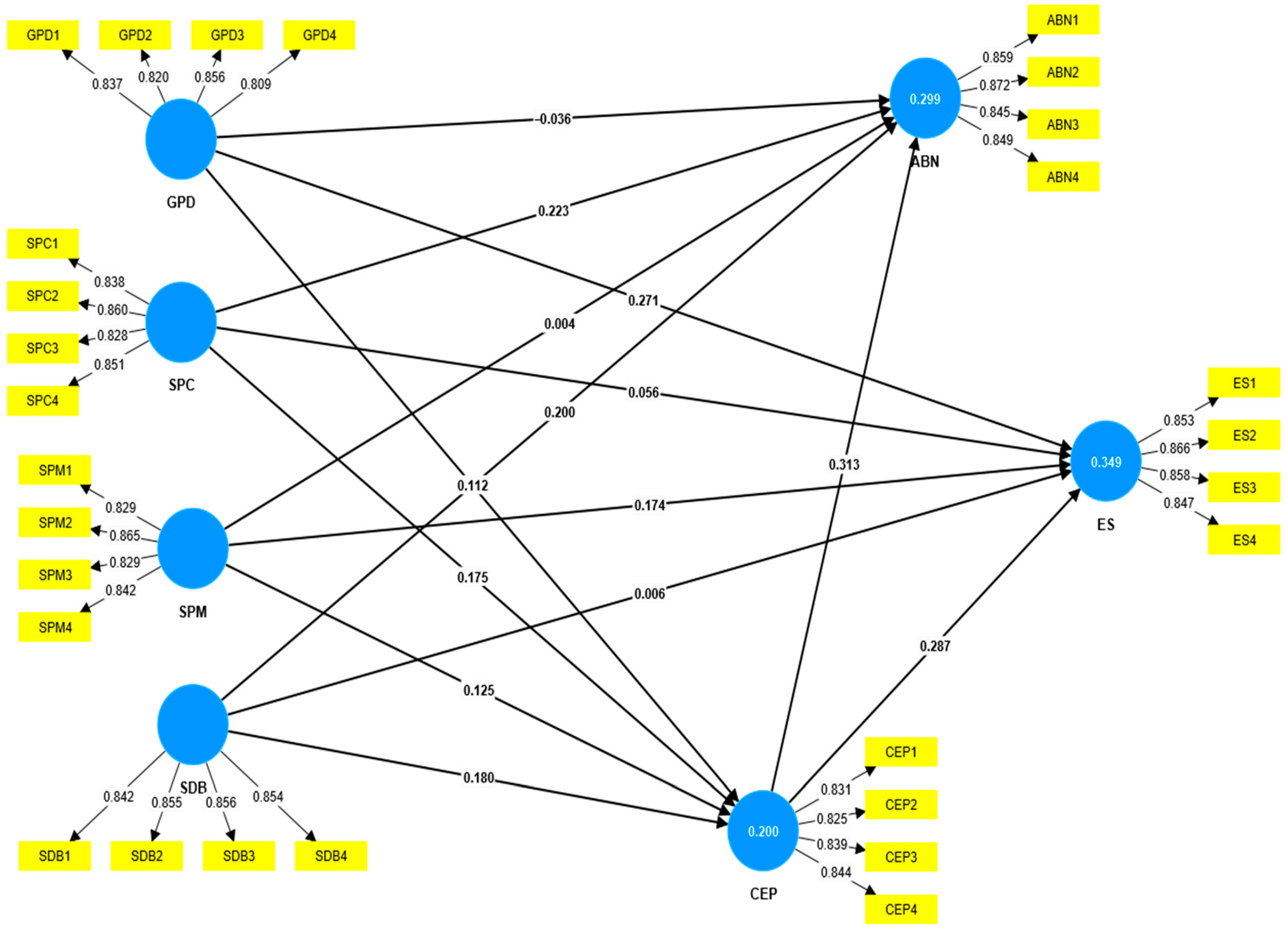

Figure 3 illustrates the structural model that reveals divergent pathways for sustainability outcomes. Green Product Development shows a strong positive relationship with Environmental Sustainability, but no connection to access to Basic Needs, while Sustainable Pricing and Distribution demonstrate the opposite pattern—substantial effects on Basic Needs with minimal environmental impact. Sustainable Promotion moderately contributes to environmental outcomes. Consumer Experience Perception strongly mediates both relationships, confirming its central role in converting marketing strategies into social benefits.

The psychometric properties of the measurement instrument demonstrated satisfactory performance across all seven constructs (

Table 4). Factor loadings ranged from 0.809 to 0.872, with sustainable pricing items showing a particularly strong convergence (SPC2 = 0.860). The relatively narrow range of loadings within each construct suggests minimal item redundancy, which aligns with guidance on optimal loading patterns [

35,

36]. Notably, the lowest loading (GPD4 = 0.809) still exceeded [

36] conservative threshold of 0.70, indicating that even the weakest indicators contributed meaningfully to their constructs. Reliability metrics revealed consistent internal consistency, with composite reliability values clustering between 0.899 and 0.917. This tight range suggests that the constructs perform similarly, despite measuring distinct theoretical domains. The AVE values, ranging from 0.690 to 0.733, not only satisfy Fornell and Larcker’s [

34] convergent validity criterion but also indicate that latent constructs explain approximately 70% of their indicators’ variance, leaving limited room for measurement error.

Table 5 presents two complementary approaches for the discriminant validity assessment. The Fornell-Larcker matrix reveals that the strongest inter-construct correlation exists between green products and sustainable pricing (r = 0.494), which raises questions about whether consumers perceive these as distinct strategies or bundled offerings. This correlation, while below the discriminant validity threshold, suggests a potential conceptual overlap that warrants theoretical consideration [

36].

HTMT ratios provide a more nuanced picture. The GPD-SPC relationship (HTMT = 0.581) approaches, but does not exceed conservative threshold of 0.85, although it surpasses the more stringent 0.50 cutoff suggested for conceptually similar constructs. Meanwhile, the relatively low correlations between sustainable marketing strategies and outcome variables (ABN and ES) indicate that these relationships operate through mechanisms rather than direct associations, a pattern confirmed by the subsequent mediation analysis.

Table 6 presents the hypothesis testing results, revealing distinct patterns in how sustainable marketing strategies affect environmental sustainability (ES) and access to basic needs (ABN). The structural model explains 34.9% of variance in ES and 29.9% in ABN, indicating moderate explanatory power.

The results demonstrate divergent sustainability pathways. For environmental outcomes, green product development (GPD: β = 0.271, p < 0.001) and sustainable promotion (SPM: β = 0.175, p < 0.001) show significant positive effects, while sustainable pricing (SPC: β = 0.003, ns) and distribution (SDB: β = 0.006, ns) have negligible impacts. Conversely, for social accessibility, sustainable pricing (β = 0.223, p < 0.001) and distribution (β = 0.200, p < 0.001) significantly improve basic needs access, whereas green products (β = −0.036, ns) and promotion (β = 0.004, ns) show no effect.

Consumer Experience Perception (CEP) demonstrates robust positive effects on both outcomes (ABN: β = 0.313; ES: β = 0.287, both p < 0.001), suggesting its pivotal role in translating marketing strategies into sustainability outcomes.

The mediation patterns reveal differential dependence on experiential processing. Full mediation occurs when strategies lack direct effects but operate entirely through consumer experience—notably for GPD → ABN, SPM → ABN (social outcomes), and SPC → ES, SDB → ES (environmental outcomes). These findings indicate that certain strategy-outcome combinations require complete experiential translation to generate impact.

Partial mediation characterizes relationships where both direct and indirect pathways operate simultaneously (SPC → ABN, SDB → ABN, GPD → ES, SPM → ES), suggesting these strategies affect outcomes through both cognitive evaluation and experiential processing.

The effect size analysis reveals predominantly small effects (f

2 < 0.15) across all relationships. Green Product Development shows the largest impact on Environmental Sustainability (f

2 = 0.075), while Sustainable Pricing has the strongest impact on Access to Basic Needs (f

2 = 0.048). Several strategy–outcome combinations demonstrate negligible effects (f

2 ≤ 0.001), notably Sustainable Promotion on ABN and Sustainable Distribution on ES. Consumer Experience Perception exhibits the most consistent effects across both outcomes (f

2 = 0.112 for ABN; f

2 = 0.101 for ES), as summarized in

Table 7.

The model explains 34.9% of the variance in Environmental Sustainability and 29.9% in Access to Basic Needs, with Consumer Experience Perception accounting for 20.0%. All Q

2 values exceed zero, confirming predictive relevance, with ES showing the highest value (0.248). Variance inflation factors remain below 1.530, indicating no multicollinearity issues (see

Table 7).

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Existing Literature

The divergent effects of sustainable marketing strategies on environmental and social outcomes contradict the prevailing sustainability frameworks. The substantial environmental impact of Green Product Development (β = 0.271) alongside its minimal social effect (β = −0.036) directly contests Porter and Kramer’s [

37] shared value hypothesis, which posits a reciprocal enhancement between environmental and social objectives. This finding is consistent with Huang et al. [

13], who reported green premiums excluding vulnerable populations, but contrasts with Scandinavian studies, where integrated policies yield balanced outcomes via government intervention. The Saudi context presents unique challenges that are absent in developed markets, where decades of sustainability education and infrastructure development have reduced implementation barriers.

Sustainable Pricing exhibits an inverse trend that builds upon Adam et al.’s [

8] research on pricing accessibility, simultaneously uncovering a previously unreported lack of environmental benefits in emerging markets. The strong effect on basic needs (β = 0.223) with negligible environmental impact (β = 0.003) contrasts sharply with European carbon pricing studies, in which social rebates maintain both affordability and environmental incentives. The Saudi economy’s historical reliance on subsidies may explain this divergence, as consumers expect affordability without environmental premiums, creating resistance to price signals that internalize ecological costs.

Consumer Experience Perception’s universal mediation role supports Hanaysha and Al-Shaikh’s [

16] finding that marketing capabilities operate through experience, although our effect sizes (0.032–0.056) fall substantially below developed market benchmarks, where indirect effects typically range from 0.08 to 0.12. This extends Schmitt’s [

38] experiential framework to sustainability contexts, while revealing weaker experiential processing in emerging markets, possibly reflecting lower baseline sustainability awareness or different cultural interpretations of environmental value. The moderate variance explained (R

2 = 0.299 for ABN, 0.349 for ES) falls below integrated sustainability studies that report R

2 values exceeding 0.45, confirming that marketing strategies alone provide limited explanatory power for sustainability outcomes.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study advances the sustainable marketing theory through three key contributions. First, evidence of systematic trade-offs, rather than synergies, necessitates the reconceptualization of how sustainability objectives interact in emerging markets. While the triple bottom line framework [

38] assumes complementarity between environmental, social, and economic dimensions, our results demonstrate zero-sum dynamics, where advancing environmental goals may compromise social accessibility and vice versa. This suggests that the boundary conditions for sustainability integration exist based on market maturity, institutional development, and cultural context, challenging the universal application of Western-derived frameworks.

Second, differential mediation patterns advance service-dominant logic [

17] by identifying when value co-creation through experience is necessary versus optional for sustainability outcomes. Full mediation for the distribution’s environmental impact indicates complete dependence on experiential translation, as logistics sustainability remains invisible to consumers until it is experienced through service encounters. Conversely, the partial mediation of product impacts allows direct cognitive evaluation of environmental attributes. This distinction, which was not previously identified in sustainability contexts, suggests that different marketing strategies require different levels of experiential processing to generate societal value.

Third, the weak direct effects seen in most relationships, with path coefficients below 0.20 and effect sizes below 0.05, show that sustainable marketing is more of a facilitator than a driver of sustainability transformation. This finding challenges the prevailing assumptions about market-based solutions and suggests that marketing operates within larger institutional, regulatory, and cultural systems that ultimately determine sustainability outcomes. The implication is that sustainable marketing strategies represent the necessary but insufficient conditions for achieving Vision 2030′s ambitious environmental and social objectives.

5.3. Practical Implications

For managers operating in the Saudi market, our findings mandate explicit strategic choices rather than pursuing integrated sustainability, which attempts to achieve all objectives simultaneously. Companies that want to be leaders in the environment should focus their resources on making green products, which have the biggest impact on the environment, and on promoting those products in a way that is sustainable to build awareness and trust. Conversely, firms prioritizing social impact should focus on pricing strategies that maintain affordability and distribution systems that ensure geographic accessibility, accepting that they may not yield environmental benefits. Current attempts at balanced sustainability appear ineffective, given these divergent pathways, suggesting that specialization may yield superior outcomes compared to integration.

Universal mediation through Consumer Experience Perception reveals a critical capability gap in Saudi organizations. Sustainable marketing effectiveness depends not only on product attributes or pricing strategies but also on the quality of customer experience across all touchpoints. This necessitates investment in service design, customer journey mapping, and relationship management, competencies traditionally underdeveloped in sustainability-focused organizations. Saudi firms should consider strategic partnerships that combine sustainability expertise with service excellence, as these capabilities rarely coexist within single organizations, and their development requires different organizational cultures and skill sets.

For the Vision 2030 implementation, our findings reveal that achieving the Kingdom’s dual objectives requires differentiated rather than unified approaches. The 50% renewable energy target aligns well with green product strategies, given their strong environmental impact, while universal service access demands different instruments, specifically progressive pricing mechanisms and expanded distribution networks. The current policy framework’s assumption of synergies between these objectives appears misaligned with market realities, suggesting that separate initiatives with distinct success metrics may prove more effective than integrated programs that attempt to achieve multiple goals simultaneously.

5.4. Policy Recommendations

The evidence suggests three critical policy interventions to address the identified trade-offs: First, the green premium paradox requires targeted subsidies to enable lower-income segments to access sustainable products without compromising their basic needs. International precedents, such as Germany’s Sozialticket system for public transport or California’s Clean Vehicle Assistance Program, demonstrate how progressive support mechanisms can bridge affordability gaps. Adaptation to the Saudi context should consider cultural factors such as large family sizes and extreme climate conditions that influence consumption patterns differently than those in Western markets.

Second, regulatory frameworks should recognize that environmental and social sustainability necessitate separate policy instruments, rather than a singular approach. Environmental objectives benefit from emission standards, technology mandates, and carbon pricing mechanisms that create market incentives for green innovation. But for social accessibility to work, there needs to be protections for affordability, universal service obligations, and geographic coverage requirements. These may not work well with market-based environmental tools. The current regulatory framework’s attempt to achieve both through a single policy is ineffective.

Third, the total mediation of effects via consumer experience indicates that conventional awareness campaigns produce minimal behavioral modifications in the absence of experiential reinforcement. Policy support should shift from information provision to experiential engagement through demonstration projects, trial programs, and hands-on learning opportunities that allow consumers to experience sustainability benefits directly. This method is especially important for sustainable distribution because our research shows that environmental benefits depend entirely on experiential translation.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

Several methodological constraints limit the generalizability of our findings. The cross-sectional design precludes causal claims, as the observed relationships may reflect reverse causation or unmeasured confounders. Longitudinal research tracking the evolution of sustainable marketing effectiveness during Vision 2030′s implementation would strengthen the causal inference and reveal whether trade-offs persist or diminish as markets mature. The sample’s urban concentration, with 54.7% of respondents from Riyadh and Jeddah, potentially excludes rural populations where basic needs challenges are the most acute, and sustainable product availability remains limited. Similarly, the overrepresentation of educated (69% bachelor’s degree or higher) and middle-income respondents may not capture the experiences of vulnerable populations that are most affected by sustainability trade-offs.

The measurement limitations warrant consideration when interpreting the results. The absence of control variables, such as education level, income, and regional differences, represents a significant constraint, as these factors likely influence both exposure to sustainable marketing and perception of outcomes. The four-item scales, while demonstrating acceptable reliability, may inadequately capture the complexity of multifaceted constructs, such as environmental sustainability, which encompasses climate, biodiversity, pollution, and resource dimensions that aggregate measures potentially obscure.

Future research should examine the moderating factors that explain when sustainable marketing strategies achieve simultaneous and divergent outcomes. Cultural values, institutional maturity, and digital infrastructure may create conditions that enable synergies, rather than trade-offs. Islamic finance principles, including zakat, waqf, and prohibitions on excessive profit (riba), may offer culturally aligned approaches to sustainable marketing that are not captured in Western-derived frameworks. Given Saudi Arabia’s high digital penetration rates, exceeding 90%, the role of digital transformation in reshaping sustainability perceptions and behaviors warrants dedicated investigation, particularly as younger generations demonstrate different sustainability values than their predecessors.

6. Conclusions

This study reveals systematic trade-offs between environmental and social objectives in Saudi Arabia’s sustainable marketing landscape, challenging assumptions of automatic synergies in emerging markets. The divergent pathways—environmental strategies failing to address basic needs while social strategies yield minimal ecological benefits—necessitate explicit strategic prioritization.

Three contributions advance sustainable marketing theory: (1) establishing boundary conditions where emerging markets face trade-offs rather than synergies, (2) identifying Consumer Experience Perception as the critical mechanism translating strategies into outcomes, and (3) demonstrating differential mediation patterns across strategy types.

For Vision 2030 implementation, our findings mandate differentiated approaches: green product strategies for environmental targets and progressive pricing for social accessibility. Organizations must choose between environmental leadership and social impact rather than pursuing ineffective balanced strategies. The universal mediation through consumer experience illustrates the importance of experiential marketing capabilities beyond traditional sustainability attributes.

Future research should examine conditions enabling synergistic outcomes and explore whether Islamic finance principles offer culturally aligned alternatives to Western sustainability frameworks.