Abstract

The valorization of agricultural residues helps improve crop economic efficiency and alleviate environmental pressures. Owing to the merits of simplicity, high efficiency, low costs, and scalability, adsorption removal of contaminants using biochar has been widely investigated. The adsorption removal of organic and inorganic contaminants from wastewater using biochar derived from agricultural residue follows the principles of the circular economy and green chemistry, facilitating both environmental remediation and agricultural development. Due to the distinctive precursors—agricultural residues—biochar exhibits unique physicochemical properties, enabling it to interact differently with contaminants in real wastewater. Herein, this review addresses the knowledge gap in wastewater remediation using agricultural residue-based biochar. It compiles the principles of adsorption with agricultural waste-derived biochar, including general concepts, interactions between biochar and wastewater contaminants, and selective adsorption. The preparation, activation, modification, functionalization, and regeneration of such biochar, as well as their application to wastewater remediation, are comprehensively outlined. Furthermore, the economic evaluation and environmental impacts, as well as the future directions and challenges in this field, have also been presented.

1. Introduction

Wastewater from various industries poses a tremendous environmental problem and health risk to human beings and water ecosystems [1]. Abundant agricultural wastes are continuously produced globally. It has been reported that the dry biomass production is over 200 billion tons per year around the world, causing a huge agricultural burden [2]. The remediation of wastewater and the appropriate disposal of these agricultural wastes are of great significance to mitigate the aforementioned burden and address these issues.

Adsorption has been a widely applied physicochemical strategy for wastewater purification and the recovery of useful compounds from wastewater [3], owing to the various well-known merits, such as high cost efficiency, simple design and implementation, high efficiency, robustness, effectiveness, scalability, sustainability, technical flexibility, technological feasibility, and environmental friendliness, while being free of by-products and providing simultaneous removal of various contaminants and resilience against toxic contaminants [4,5,6]. On the other hand, the limitations of adsorption include the potential for secondary pollution, the production of solid wastes, and the requirement for additional treatment to degrade the adsorbed contaminants, among others [7,8,9,10]. Appropriate adsorbents are crucial to ensure excellent adsorption performance [3]. Currently, different adsorbents have been fabricated, such as biochar, activated carbon, zeolites, two-dimensional materials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes, and MXene), resin, bentonite, covalent organic frameworks, metal–organic frameworks, and composites, among others [2,11,12]. Among them, carbon materials have attracted increasing attention in recent decades due to their abundant precursors and excellent physicochemical properties, such as numerous surface functional groups, high mechanical strength, and outstanding adsorption performance and reproducibility. As a type of carbon material, biochar is relatively simple and economical to produce and has been widely used for wastewater remediation. The main advantages of biochar compared to other advanced carbon materials, such as activated carbons, carbon nanotubes, and graphene oxides, include its high sustainability (e.g., waste-to-resource principles and renewable feedstock), low energy requirements and production costs, excellent scalability, and environmental co-benefits (e.g., large-scale applications in agriculture and carbon sequestration, as well as better compatibility with other materials) [7,13,14,15]. Agricultural wastes have abundant biomass (e.g., lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose), which is accessible and affordable, and can provide sufficient carbon sources and thus can be used as green and non-toxic precursor sources of biochar. The preparation of biochar using agricultural wastes not only facilitates the valorization of these wastes but also reduces the environmental and economic burden associated with them (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions). Up to now, biochar has been prepared from date seeds [4], almond shells [16], coconut shells [5,17,18], wheat straw [19], rice husks [18,20,21,22,23], corn wastes [24,25,26,27,28], wood wastes [11,29], and rape stalk [30]. These abundant precursors give biochar various physicochemical properties and distinctive advantages compared to other types of biochar. Table 1 compares biochar derived from agricultural residues, wood, and manure. As shown, the unique advantages of agricultural residue-derived biochar include high silicon content, excellent stability, more surface oxygen-containing groups, a low liming effect, superior cation exchange capacity, and its use as a bifunctional soil conditioner and slow-release fertilizer (providing K and P for N fixation) [31,32,33]. Therefore, the use of agricultural waste-derived biochar for adsorption and decontamination is a sustainable and feasible alternative for wastewater remediation [34,35].

Table 1.

Comparison of biochar derived from agricultural residues, woods, and manure.

Unlike activated carbons, pristine biochar usually possesses a lower surface area and total pore volume and limited adsorption sites due to poor porosity [13,14,15,36], along with poor adsorption ability [37]. The dominant drawback of pristine biochar is poor dispersibility (e.g., easy to float and aggregate) [38]. Fortunately, the physicochemical properties (e.g., dispersibility; porosity; separability; mechanical strength; surface area; electronegativity; and the surface’s functional groups, pore size, interaction forces, etc.) and the adsorption properties (e.g., adsorption capacity, affinity, selectivity), adsorption kinetics, isotherm, and thermodynamics) of a specific biochar can be promoted via activation and modification to improve the porosity, adsorption sites, and surface chemical affinity and interactions [5]. The pristine biochar has been activated using strong acids, strong bases, and metal oxides and functionalized using various modifiers, via element doping (e.g., N, S, and heavy metals), and surface charge change to better catch target contaminants from wastewater [14,15,19,39,40,41,42,43].

Herein, based on the background above, this review presents the recent advances of agricultural waste-derived biochar for wastewater remediation via liquid–solid adsorption, mainly focusing on the adsorption mechanisms, biochar preparation and modification, main outcomes, economic evaluation, and environmental impacts. Moreover, the future direction and research needs are also recommended to guide and inspire the incoming work. This review follows the principle of the circular economy and waste valorization, providing a deep understanding of agricultural waste disposal and use, presenting the practical application of wastewater decontamination, and contributing to the sustainable development of agriculture and society globally, as well as resource integration and utilization locally.

2. Mechanism of Adsorption Using Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

2.1. General Conceptions of Adsorption

The performance and properties of adsorption decontamination from wastewater depends on the physicochemical properties of biochar (e.g., ash content, hydrophobicity, porous property (micro- or mesoporous), point of zero charge (pHPZC), element composites (e.g., C/O and C/H ratios), and the surface chemical functional groups), the properties of substrates (e.g., pKa value, solubility, hydrophobicity, chargeability, electron distribution, and molecular or ion size), the interaction between the components in the bulk liquid and the surface of biochar, and so forth [13,14,15,36,40,44]. The specific absorption may be the synergistic result of these as-mentioned impacts.

2.2. Interactions Between Biochar and Contaminants in Wastewater

Wastewater contains a complex mixture of compounds with a wide range of molecular sizes. Effective adsorption requires that these compounds access the micropores of biochar. Larger molecules are often preferentially adsorbed over smaller ones; however, they can block micropores and hinder the diffusion of smaller molecules into narrower pores. The particle size of the biochar, such as powder versus granular, influences adsorption kinetics by limiting intraparticle mass transfer, but it does not change the overall adsorption capacity, which depends on the total specific surface area of the biochar [39]. Biochar with a high surface area and an abundant porous structure, including mesopores and micropores, provides ample adsorption sites for physicochemical interactions with wastewater contaminants [14,15,45,46]. Adsorbent affinity is a key determinant of capacity, irrespective of contaminant concentration [47]. For example, smaller ions typically show higher affinity for reactive sites and are removed more rapidly, yielding superior adsorption performance [48]. In addition, functional groups can contribute substantially when the biochar has a low specific surface area [49]. The dominant physicochemical interactions governing adsorption are critical for contaminant removal and are summarized in Table 2 [2,4,40,50,51]. The dominant interactions that contributed to the adsorption can be identified via a comprehensive analysis of various adsorption properties and the characterization of biochar before and after adsorption [6,24,45,46,47].

Table 2.

The mechanisms of the adsorption using agricultural residue-based biochar.

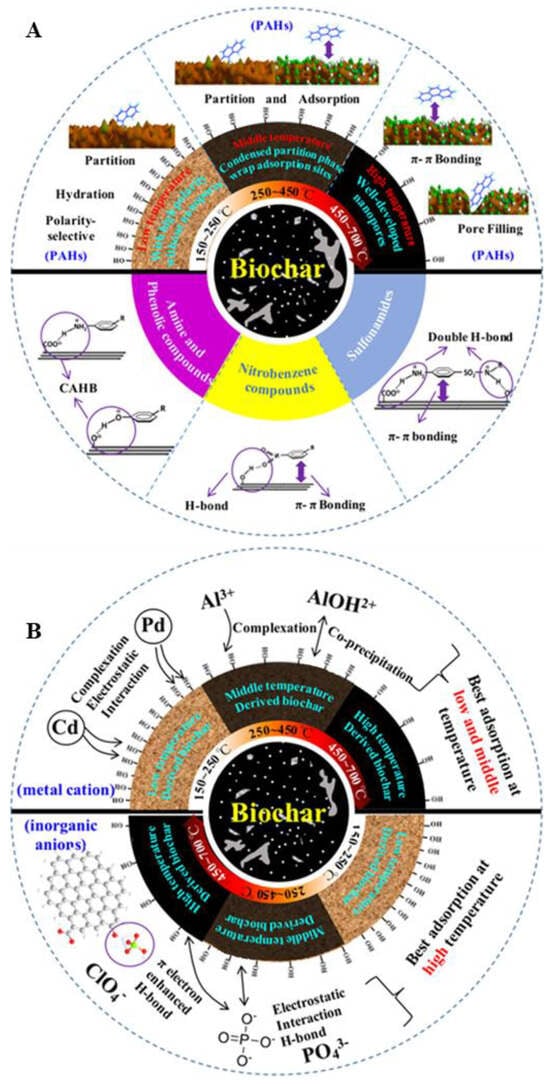

The assumed adsorption mechanisms of organic and inorganic substances on biochar are compiled in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The assumed adsorption mechanisms of organic (A) and inorganic (B) substances on biochar. Reprinted from Ref. [31]. Copyright (2018), with permission from ACS.

2.3. Selective Adsorption

Achieving selective interaction of biochar with specific substrates (also known as selective adsorption) is crucial for targeted wastewater remediation. The selectivity of biochar is determined by the interaction between its surface properties and the molecular characteristics of the pollutant, as shown in Table 1. In particular, hydrophobic compounds are generally adsorbed more readily via hydrophobic interactions than hydrophilic compounds [60]. The -OH and -NH2 groups on the biochar surface are reported to be the dominant groups responsible for the adsorption of anionic dyes [52]. Interactions between the aromatic rings of biochar and those of organic pollutants facilitate the selective adsorption of aromatic compounds [14,59]. π-π interaction and O-containing groups (e.g., -OH and C=O) on the surface of biochar composites can facilitate the adsorption of cations through surface polarization and electrostatic attraction [58,61]. Negatively charged biochar can adsorb ammonium ions via electrostatic attraction and H-bonding between O-containing groups, -OH, C-O, -COOH, and -COC- of biochar and ammonium ions, and phosphate via surface precipitation [23,24,62]. Cations Mg2+ and Ca2+ in biochar can trap PO43− and H2PO4− in liquids via precipitation, while anion Cl− of biochar contributes to adsorbing PO43− via electrostatic forces [24,63,64]. The specific interactions of SiO2 in biochar can enhance the affinity towards PO43− via electrostatic interactions and H-bonding (or ligand exchange) by its -OH group, especially at acidic pH levels [23]. Groups like -OH, -COOH, -Ar, Ar-NH2 (aromatic amines), R1-CO-N-R2R3 (amides), and -C5H10N- (pyridine) of biochar are beneficial to the adsorption of ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate through ion exchange [17]. Biochar can interact with both ammonium- and nitrate-N via electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, and physisorption, with electrostatic attraction being particularly significant [51]. Positively charged biochar surfaces can also interact with cationic compounds via Coulombic interactions under acidic conditions [49]. Additionally, small organic molecules can be physically trapped within the micro- and mesopores of biochar via pore filling [42,55].

Selective adsorption by biochar can be influenced by its preparation and adsorption conditions. For example, low pyrolysis temperature (<400 °C) results in more oxygen-containing functional groups, making it better for inorganic or heavy metal adsorption through complexation. High temperature (>600 °C) increases surface area and aromaticity, making it more selective for organic pollutants via π-π stacking and pore filling. Solution pH alters the surface charge of biochar; if the pH is above the pHPZC, the biochar becomes negatively charged, enhancing its selectivity for positively charged metal cations. Thus, the chemical and physical structure of biochar can be tailored through specific preparation strategies (e.g., molecular imprinting), production conditions, and post-treatment to improve its selective adsorption, as described in Section 3.3.

3. Preparation, Regeneration, and Characterization of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

3.1. General Conceptions and Properties of Biochar

Biochar, a porous C-rich material, can be prepared via high-temperature (200–1700 °C) pyrolysis of biomass (e.g., lignocellulose) under anaerobic, O2-limited, or O2-free atmospheres, such as inert gases and vacuum environments [12,18,37,39,48]. In general, biochar has a rough surface, irregular shape, condensed structure, relatively high pore volume and surface area (lower than activated carbon), density, greatly aromatized and graphitized architectures, and abundant surface functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH, -NH2, and C=O) [19,27,40,65]. Biochar’s C contents can be identified as high (≥60%), middle (30–60%), and low (10–25%) [18,51,52]. Biochar has the strengths of rich C content, stable C structure, abundant precursors, sustainable production, renderability, high cost-effectiveness, convenient modification and surface functionality, high catalytic activity and thermal stability, high accessibility for dissolved pollutants, and can remove both inorganic metal ions and organic contaminants [12,38,42,65]. The limitations of biochar include poor affinity, low selectivity, and small co-adsorption capacity [51,65].

3.2. Preparation of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

Various approaches have been developed for the biochar preparation, including conventional high-temperature carbonization [29,42,66], microwave-assisted high-temperature carbonization [15,30,67], strong acid carbonization [68], conventional hydrothermal carbonization [14,15], and microwave-assisted hydrothermal carbonization [15] using different agricultural wastes as precursors at present. Different agricultural wastes have different elemental compositions and thus exhibit different properties [39]. In general, these agricultural wastes require pre-treatment to clean and dry the material and to reduce them to a small and uniform size, as shown in Figure 2 [4].

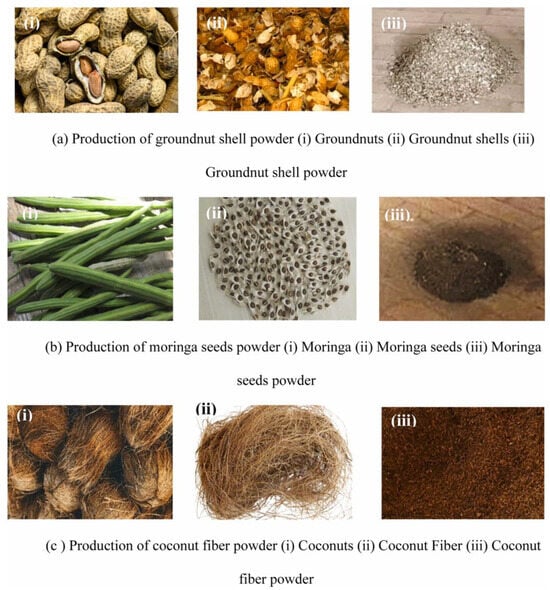

Figure 2.

Pre-treatment of agricultural wastes for the preparation of biochar. Reprinted from Ref. [69]. Copyright (2025), with permission from Elsevier.

Conventional carbonization is often operated at high temperature under inert gas atmosphere or vacuum conditions in open or closed systems using a muffle furnace, tubular furnace, curable tube, heat pipe reactor, top-lit updraft two-barrel furnace, portable charring kiln, microwave oven, and so forth [12,19,42,48,51,70]. According to the preparation conditions, pyrolysis can be divided into slow (300–700 °C, several hours, 35–50 wt% of yields), fast (400–600 °C, <10 s, <30 wt% of yields), and flash (about 1000 °C, <3 s, <20 wt% of yields) [48]. The dynamic molecular structures of the biochar produced at different pyrolysis temperatures are presented in Figure 3.

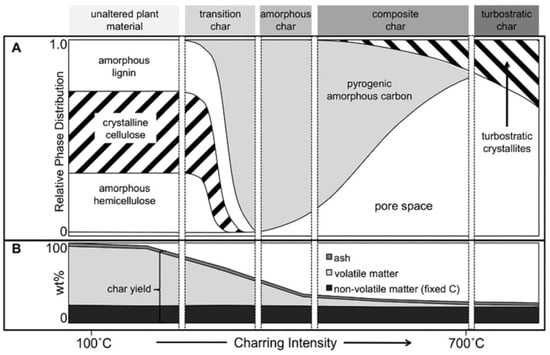

Figure 3.

Dynamic molecular structure of the biochar produced at different pyrolysis temperatures: relative phase distribution (A) and weight loss (B). Schematic representation of the four proposed char categories and their individual phases. Reprinted from Ref. [71]. Copyright (2015), with permission from ACS.

Unlike pyrolysis under atmospheres, vacuum decomposition induces faster volatile removal, slighter pore blockage, lower loss of surface groups, and shorter combustion duration, followed by greater yields and properties of the biochar [1]. Hydrothermal carbonization is usually performed by mixing the precursor with less solvent (e.g., distilled, acidified, or alkaline water and or organic reagents), subsequently reacting under high temperature (80–250 °C) and pressure (2–6 MPa) [14,15]. Microwave heating can assist both the regular and hydrothermal carbonization owing to the distinct heating ways [13,14,15,59,72]. These approaches have been described in detail in our previous works [13,14,15,59,73]. Additionally, the molten salt method has also been used, in which micropores are formed via the partial oxidation of components under high temperature and air atmospheres, while larger pores are formed thanks to the etching and the template impacts of the molten inert salts [61]. Among the above-mentioned approaches, the conventional high-temperature carbonization is the most widely applied approach for biochar preparation [43,74]. The limitations and advantages of these approaches for the preparation of biochar are compiled in Table 3. The optimal strategy for biochar preparation heavily depends on the properties of biomass (e.g., moisture content, composition, type of agricultural wastes) and the intended application of biochar (e.g., soil amendment, adsorbent, catalyst).

Table 3.

The advantages and limitations of developed strategies for biochar preparation [13,14,15,59,61,72].

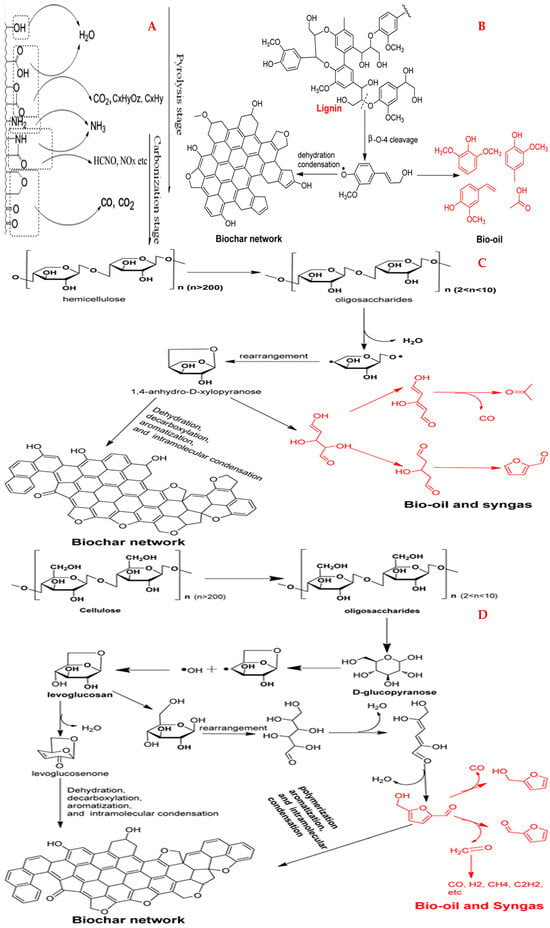

During the preparation processes, the biomass undergoes melting, softening, vesicle formation, and decomposition with gas emission [61]; the light organics of biomass precursors are highly reacted and disrupted via volatilization [18]; the hemicellulose and cellulose usually decompose at 200–300 °C and 300–400 °C, respectively (the mechanism of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose pyrolysis during biochar preparation are shown in Figure 4) [61]; the existing metal components may accelerate the pyrolysis of the biomass and improve the porosity of biochar [23,75]; the oxidation induces low ash components and high gas emission under air atmosphere [49]; the pHPZC value can be increased (due to the elimination of acidic O-containing groups, like -COOH, -OH, and R-CH=O), and yields of C and biochar can be improved (due to low oxidation) under high temperatures and limited O2 atmosphere [23,76]; the exterior of biomass usually suffers more rapid decomposition compared to the inside part, leading to visible cracks and the exposure of the inner Si-containing structure [77]; the aromatic groups can be formed via the condensation and pyrolysis of lignocellulosic [35]; and the C yield and ash fractions relate to the lignocellulose contents in the precursors [18]. Moreover, the porous structure of biochar can be blocked by tarry and alkaline metal components during the biomass preparation [40].

Figure 4.

Decomposition of biomass with the increase in pyrolysis temperature (A); the pyrolysis mechanisms of lignin (B), hemicellulose (C), and cellulose (D). Reprinted from Ref. [71]. Copyright (2015), with permission from ACS.

Precursor types, carbonization strategies, heating approaches (temperature, way, rate, and holding duration of heating), and carbonization atmosphere (e.g., air, N2, Ar, vacuum, and adiabatic conditions) can influence the physicochemical and structural properties of biochar [19,48,49,70]. Various precursors include different metals and inorganic and organic components, impacting the pHPZC value, morphology, and C/H and C/O ratios of biochar [76]. Wood-based biochar is usually reported to exhibit higher stability and better surface and adsorption properties than the others [45]. Alkali metals in the precursor help broaden the biochar lattice and the pore size [41]. Mg and Ca remaining in biochar after pyrolysis favor cation adsorption via ion exchange [63,64]. SiO2 and its content in precursors, especially for rice husk, have been reported to promote the texture, architecture, and porosity of biochar [23,77]. SiO2 can also react with H2O to produce Si-OH on the biochar’s surface, which favors adjusting its surface charge at different pH values [52]. Biochar’s hydrophobicity, aromaticity, and graphitization improve with the augmented carbonization temperature [40]. On the other hand, these metal components may induce the reduction of biochar’s surface area and the obstruction of its pores [35]. Low carbonization temperatures (<400 °C) lead to low specific surface area (<10 m2/g) but favor protecting the functional groups, increasing the hydrophilicity of biochar (due to the preservation of O-containing groups) and the removal of polar or inorganic contaminants via surface functional group-induced precipitation, ion exchange, and electromagnetic gravity [17,48,76]. In contrast, raising the temperature (500–700 °C) greatly improved the surface area (>100 m2/g), pore volume, and porosity, owing to the rapid generation of volatile substances (e.g., H2, CO, and CH4), the sufficient discharge of them, decomposition of by-products in pores (e.g., tar oil), and the occurrence of aromatic condensation [23,41,78]. Nevertheless, high carbonization temperatures are not always beneficial. Excessive temperature (>700 °C) could decrease the surface functional group (e.g., C=O, -COOH, -OH) content via dehydration and deoxygenation, reduce the surface area and yield of biochar, increase the alkalinity of biochar (due to the removal of acidic groups), raise the pHPZC of biochar (since the dehydration and decarboxylation and the presence of basic carboxylate and hydroxide groups) intensifies), disrupt the biochar’s structure, and limit the adsorption ability [23,45,51,61,78]. Moreover, the C content of biochar can be improved via H2SO4 and sonication treatment in sequence [68].

3.3. Improved Fabrication of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

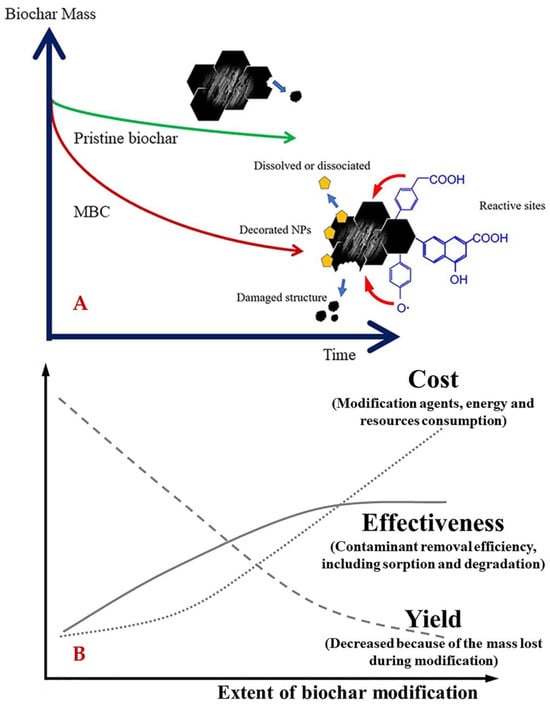

The physicochemical processing, including activation, modification, and functionalization, favors the improvement of biochar’s surface and pore properties [40,51]. In general, biochar can be chemically and physically activated using KOH, K2O, NaOH, NH3·H2O, MgCl2, ZnCl2, CaCl2, HNO3, H2SO4, H3PO4, HCl, CO2, steam, etc. [14,15,19,39,40,41,42]. Compared to chemical activation (450–900 °C), physical activation commonly requires a higher temperature and longer duration [41]. Chemical treatment can increase the pHPZC through protonating the functional group and removing carbonates and hydroxide in biochar [51]. Particularly, activation using NH3·H2O can trigger the dehydration, decarbonization, and dehydrogenation of substances containing C=O, changing the H/C and C/O fractions and introducing basic N-containing groups [65]. Washing with KOH or H3PO4 can increase the density of specific functional groups to target either acidic or basic pollutants [59,79]. Activation using CO2 can induce the oxidation of biochar and introduce O-containing groups [75]. Nevertheless, the use of these activators could cause negative environmental effects and low cost-effectiveness. For instance, ZnCl2 is known as a toxic activator, which may induce secondary pollution and pose potential environmental risks. Biochar has been functionalized using a variety of modifiers, like CS2, sodium alginate, cellulose, chitosan, coal fly ash, inorganic elements (e.g., N and S), and transition metals (e.g., La) and their salts (e.g., Fe3O4) [5,22,28,38,58,75,80]. Specifically, incorporating sodium alginate in biochar can enhance metal cations adsorption via coordination interactions [81]. Coal fly ash is conductive to promoting the surface aromaticity and hydrophobicity and reducing C=O but protecting R1(R2)C=O groups [75]. S-doping is conducive to immobilizing the metals and introducing functional groups (e.g., S2− and SO32−) [58]. N-doping can enhance the surface polarization and electrostatic attraction of metal cations [58,61]. Adding N or S into the carbon lattice can create specific sites that have a high affinity for mercury or gold [82,83]. Metal doping in biochar can decrease the electronegativity and alter the surface charge distribution and thus improve its affinity [27]. La-doping can enhance the specific affinity of PO43− [57]. Fe-doping could promote various properties of biochar, such as surface texture, magnetism, surface charge density, mechanical strength, thermal stability, redox ability, etc. [38,48]. It has been reported that Fe-impregnated biochar can selectively pull out arsenic or phosphates and be easily removed from water using magnets [15,28,72]. Ca-doping contributes to broadening the pH suitability of biochar, as well as improving the biochar decomposition, improving the porosity, and supporting the Fe doping [48,84,85]. However, the modifiers may lead to some adverse effects on biochar, e.g., the blockage of pores, the decrease in the surface area, and the reduction of the economic efficiency, yield, and effectiveness of biochar (Figure 5) [58].

Figure 5.

The effect of modification on the carbon structure stability (A) and the cost, effectiveness, and yield (B) of biochar. Reprinted from Ref. [86]. Modification can decrease the stability of biochar structures, while reducing yield but increases the cost and effectiveness. Copyright (2021), with permission from ACS.

3.4. Regeneration of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

Regeneration of biochar are crucial for evaluating its stability, economic efficiency, sustainability, feasibility, and practicality [1]. In general, biochar used for wastewater remediation can be regenerated to restore its surface-active sites and adsorption capacity. Reusing biochar multiple times makes the process economically viable and environmentally sustainable. Reported approaches for biochar regeneration include thermal, chemical, and biological methods [87]. Among these, thermal regeneration is the most common, involving heating the spent biochar to high temperatures (200–500 °C) under conventional or microwave heating in an inert atmosphere (such as N2) to decompose or volatilize the adsorbed pollutants. Although this method is very effective at restoring pore structure, it can cause a slight loss of biochar mass (carbon burn-off) and may destroy some surface functional groups (such as -OH or -COOH) over multiple cycles. Chemical regeneration refers to the use of solvents (e.g., ethanol, acetone, or acids/bases) to wash the contaminants off the biochar surface or oxidizing agents (e.g., H2O2 and S2O82−) to chemically degrade them, with the latter approach commonly requiring the activation of the oxidizing agents. For example, washing using H3PO4 can remove accumulated mineral deposits and metallic ions that block the pores of biochar. Bio-regeneration is an emerging, eco-friendly approach that uses colonized microorganisms on the biochar surface to digest organic pollutants trapped in the biochar’s pores. This method requires low energy consumption and operates at ambient temperatures, but it is much slower than thermal or chemical methods [29,42,71,88]. Typically, thermal, chemical, and biological regeneration are suitable for the removal of volatile substances, heavy organics, and biodegradable compounds from spent biochar, respectively.

Many authors have stated that biochar can be reused at least three to five times [5,87]. The decrease in adsorption capacities of biochar after several adsorption–desorption cycles has been frequently reported, which can be attributed to the inactivation of certain adsorption sites owing to the reduced surface area and pore obstruction after thermal processing, the disruption of surface functional groups and the loss of some functional elements (e.g., N, S, and mental) by solvents and under high temperature processing, incomplete desorption due to the strong bonding, and the interference of other compounds in wastewater [28,36,51,58,85]. The consumed biochar can be regenerated via high-temperature treatment (e.g., 150 °C [51]) and solvent elution (e.g., 30% EtOH, distilled water, 0.1 M EDTA, HCl, NaOH, HNO3, and H2SO4 solutions), which are favorable for the valorization of waste biochar and the removal of the secondary pollution risk from the enriched contaminants in biochar [12,14,18,19,28,51,68,78].

4. Use of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar for Wastewater Remediation

Agricultural waste biochar adsorption is a low-cost and effective wastewater remediation strategy that is able to remove different contaminants, including dyes, antibiotics, pesticides, pharmaceutical residues, heavy metal ions, nutrient substances, and organic carbon, as well as improve the wastewater quality (e.g., turbidity, chroma, smell, pH value, and toxicity) [35]. The adsorption capacity of biochar is commonly lower in wastewater than in clean water due to the competitive adsorption among the target compounds with other contaminants, caused by the complex composites of wastewater [47]. Thus, biochar has been combined with other materials, e.g., poly(N-hydroxyethylacrylamide) hydrogel, to achieve better decontamination performance of wastewater [3,62,89,90]. Adsorption decontamination facilitates decreasing the total solids (TS), total suspended solids (TSS), total volatile suspended solids (TVSS), total dissolved solids (TDS), total organic carbon (TOC), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), and chemical oxygen demand (COD) of wastewater [15,37,39]. Meanwhile, the recovered macronutrients such as N, P, and K (in the forms of ammonium, nitrate, phosphate, and potassium salts) from certain types of eutrophication wastewaters like human urine, septic tank wastewater, blackwater, and biogas wastewater via adsorption can be reused to support the growth of crops [23,24,51]. Similarly, the recovery of phenolic compounds from olive mill wastewater and N and S from latex industrial wastewater can also be further valued [37,70]. Generally, the adsorption decontamination performance of wastewater by agricultural waste-based biochar depends on the preparation processes (e.g., the pyrolysis temperature, gas atmosphere, and heat approaches), the target substrates, the complexity of liquids, the operation conditions like dosage of adsorbents, volume of liquids, reaction temperature, content of contaminants, pH of the matrix, contact duration, adsorption mode (batch and column modes), co-existing ions, etc. [15,69].

In general, high initial concentrations favor adsorption due to the large concentration gradient and high driving force leading to great interphase mass transfer, intrapore molecule diffusion, and improved affinity of biochar towards the target compounds, followed by rapid adsorption with high capacity [1,11,57,78,91]. At the initiation of adsorption, the process proceeds rapidly, attributed to the sufficient and accessible adsorption sites, a high concentration difference driving force, and low diffusion resistance. With prolonged connection time, the adsorption will gradually slow down due to the limited adsorption sites and low mass transfer and molecular diffusion. Eventually, a dynamic adsorption–desorption equilibrium will be reached, where the total adsorption capacity becomes stable, and the adsorption site may continue the empty–occupy cycle, and the adsorbed compounds might influence the remaining ones in liquids via electrostatic repulsion, size exclusion, or other weak interactions [1,2,18,37,58,78]. High dosages of biochar do not always favor adsorption. Appropriate dosages can not only offer enough surface adsorption sites and ensure economical and fast operation but also avoid the biochar congestion [11,27,28,58]. The influence of pH on adsorption is complex. For biochar, the pH of adsorption systems can change the types and distribution of biochar’s surface charge via altering the zeta potential of biochar relative to its pHPZC and the dissociation of chemical groups of biochar’s surfaces, thus affecting the electrical interactions with the target substrates in liquids [1,5,49]. It has been reported that the alternation of biochar’s surface charge can promote its adsorption selectivity [51]. For the target substances (e.g., dyes, TC, phosphorates, ammonium, and Fe ions), especially the amphoteric compounds, pH can change their existence form (molecule or ion) in liquids and thus impact their affinity with biochar [6,11,27,76]. Usually, acidic conditions (pH 5–6) facilitate metal sorption, whereas alkaline conditions facilitate the organics and PO43− sorption [48,77]. Under very acidic conditions, competitive adsorption between target compounds (e.g., metal ions and NH4+) and H+ and electrostatic repulsion will occur, limiting the adsorption [11,58,61]. In contrast, alkaline conditions are favorable for biochar adsorption by promoting their surface negative charge density and enhancing the induced electrostatic interaction [48,76]. Meanwhile, organics are highly ionized under alkaline conditions, allowing high mitigation and diffusion of them [77]. Alkaline conditions also help cation adsorption via electrostatic attraction, surface complexation, and precipitation but inhibit anion adsorption via the competitive adsorption of OH− ion and electrostatic repulsion [18]. High temperature is usually conducive to endothermic adsorption, while low temperature is conducive to exothermic adsorption. However, high temperatures can decrease the adsorption interaction and intensify molecular motion, which may result in the desorption of substances [1,11]. The effect of temperature can be detailed via the thermodynamic investigations [13,14,59]. The co-existing ions (e.g., Cl−) change the ionic strength of the liquids, impacting the adsorption via the salting-out effect, molecular dissociation, competitive adsorption, and electrostatic screening effect [51,58]. Thus, the optimal adsorption conditions are crucial for the desired adsorption performance.

The optimized adsorption of various contaminants from wastewater using biochar derived from various agricultural wastes is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

The adsorption of contaminants from wastewater using biochar derived from agricultural residues.

As listed in Table 4, a variety of agricultural wastes have been used for the adsorption of different contaminants and nutrients from various wastewater. The calcined temperature and duration for biomass carbonization are in the range of 300–900 °C and 0.5–6.0 h, respectively, under a N2, Ar, or vacuum atmosphere, depending on the agricultural wastes. The specific surface area, pore diameter, and total pore volume of different pristine biochars range from 1.65 to 428.98 m2/g, from 1.1 to 20.9 nm, and from 0.0005 to 0.5320 cm3/g, respectively. The activated biochar usually possesses better porosity and higher surface areas. The functional groups -OH, -COOH, C-H, C=C, and C=O are crucial for the effective adsorption of contaminants from various wastewater. The adsorption equilibrium duration lasts from 40 min to 5 days. Most biochar adsorbents demonstrate strong performance and reusability in real wastewater treatment. In municipal, industrial, livestock, textile, and synthetic effluents, the adsorption capacities of agricultural residue-based biochar are 78 mg/g, 14–140 mg/g (or 0.5–1.1 mg/L), 28 mg/g, 5–582 mg/L, and 3–241 mg/g, respectively. Municipal wastewater typically contains nutrients (N and P), pathogens, and emerging micropollutants (such as pharmaceuticals) in large volumes with relatively low concentrations of diverse pollutants. In this context, the main roles of biochar are physical trapping in pores and supporting biodegradation. Industrial wastewater comprises heavy metals, phenols, and complex organics with high toxicity at elevated concentrations and extreme pH levels. Here, ion exchange and surface complexation with oxygen-containing functional groups (-OH and -COOH) are crucial, and biochar often requires functionalization. Livestock wastewater contains high levels of ammonia, nitrates, and antibiotics, where biochar adsorption primarily occurs through electrostatic attraction for ammonium ions and pore filling for bulky antibiotic molecules. Textile wastewater is rich in residual dyes and surfactants, with high turbidity and recalcitrant aromatic structures; in this case, biochar with a higher surface area, more aromatic rings, and enhanced π–π interactions facilitates adsorption. It is worth noting that the abundant diversity of biochar, contaminants, and wastewater types, as well as insufficient data samples make comparisons of adsorption performance more challenging and require greater caution. Unlike stable synthetic wastewater, adsorption in real cases is complicated by varying components and conditions. Most studies focus on batch adsorption. Few authors have discussed the impact of actual wastewater instability on adsorption, and research on wastewater has primarily aimed to validate the potential feasibility of biochar for remediation. Comparative adsorption studies across different wastewater streams and investigations into reusability for wastewater remediation are even more rarely reported.

5. Economic Evaluation and Environmental Impacts

Owing to the high cost-effectiveness, adsorption ability, and large agricultural biomass reserves, biochar has been seen as an excellent alternative adsorbent for activated carbons [51,78]. Accordingly, biochar is ~6-fold cheaper compared to the majority of activated carbons (up to 9 USD/kg) [40]. Compared to activated carbon, the production cost of wheat straw-based biochar is reduced by 34-fold [51]. The energy requirement for preparing biochar was reported to be 15-fold lower compared to activated carbon [51]. Another work states that the cost of biochar (0.08 USD/kg) is 12 times lower than that of other C-based adsorbents [93]. Specifically, in the Philippines, the evaluated costs are 0.09 USD/kg for plant-based biochar and 1.1–1.7 USD/kg for activated carbons [2]. The costs of biochar prepared from coconut shells [94], pine wood [94], rotten sugarcane bagasse [61], and pomelo peel [41] are 0.8, 0.9, 2.4, and 9.8 USD/kg, respectively. It has been reported that the biochar market share will reach USD 0.45 billion by 2030 globally [48]. Furthermore, the evaluated cost for treating real antibiotic wastewater using biochar is in the range of 9–914 USD/m3 [12]. For treating livestock wastewater, the cost is expected to be as high as 61.6 thousand USD/year [77]. On the other hand, the recovered nutrients and bioactive compounds from wastewater can be valorized as fertilizer or bio-products to enhance the process’s economic viability and sustainability. Moreover, the spent biochar can be used for soil improvement, while the silicon element also helps plants resist pests and diseases, strengthens cell walls to prevent lodging (falling over), and improves drought tolerance. Overall, by using agricultural wastes, optimizing the pyrolysis process for energy efficiency, valorizing the absorbed substances and using biochar, and ensuring responsible management of the spent biochar, the environmental benefits of wastewater remediation can significantly outweigh the localized or production-related burdens.

The positive environmental impacts of the preparation of biochar using agricultural waste for wastewater remediation are as follows: (i) Preventing the decomposition or open burning of agricultural waste minimizes the release of greenhouse gases and other harmful air pollutants. (ii) Biochar is highly effective at adsorbing and immobilizing a wide range of water contaminants, including heavy metals, nutrients, and recalcitrant organic pollutants, favoring the production of cleaner effluent, safeguarding aquatic ecosystems and human health. (iii) The pyrolysis process converts the carbon in the agricultural biomass into a highly stable, recalcitrant form of C in the biochar, while the used biochar is often co-disposed or applied to soil (where applicable and safe). Around 50% of the original carbon in the biomass feedstock is retained in the stable biochar for centuries, acting as a carbon-negative technology. (vi) Even though the biochar preparation releases certain waste gases into the atmosphere, the total emission is much decreased compared to the direct incineration, and the good reusability and regeneration properties of biochar reduce the potential environmental impacts [41]. A sustainability assessment described that the preparation of wheat straw-based biochar decreased fossil depletion by 35% and human toxicity by 13% [51]. (v) By substituting traditional chemical adsorbents or treatment methods, biochar application can indirectly reduce emissions associated with the production of those alternatives. (vi) Mitigating the pollution risk of soil induced by agricultural wastes.

Nevertheless, the topic can pose several potential environmental issues, including the following: (i) Energy consumption. A study shows that low-temperature slow pyrolysis can be an energetically efficient strategy, with the energy produced per unit energy input ranging from 2 to 7 MJ/MJ [95]. The pyrolysis process used to create biochar requires energy (heat), which, if derived from non-renewable sources (e.g., grid electricity or fossil fuels), can contribute to the value of the global warming potential and other environmental burdens. (ii) Gas emissions. It has been reported that the energy consumption for biochar production was 0.40 and 0.45 kg CO2(eq) per ton of wood waste during pre-treatment (e.g., chipping and drying) and pyrolysis, respectively. The total for the production process can be up to 0.9.5 kg CO2(eq) per ton of wood waste [96]. Another work stated that the greenhouse gas emissions (76.6 kg CO2(eq) per ton) for biochar production were far exceeded by the amount of biochar sequestered long-term (2430 kg CO2(eq) per ton) [97]. Improper pyrolysis conditions (e.g., low temperature, incomplete combustion) can lead to the release of volatile organic compounds and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are environmental and health concerns. (iii) Precursor transportation. The environmental impact of transporting bulky agricultural waste from its source to the biochar production facility can be significant, influencing overall CO2 emissions. (iv) Long-term/post-application impacts. Although biochar initially immobilizes heavy metals, its aging in the environment can, under certain conditions (e.g., changes in Ph or redox potential), lead to the slow release of contaminants back into the environment; (v) Contaminants in biochar. Suppose the agricultural waste itself contains high levels of pollutants (e.g., heavy metals from contaminated soil or feed). In that case, these can become concentrated in the resulting biochar, limiting its safe use for subsequent soil application. These issues can be addressed by valorizing the syngas generated during pyrolysis (e.g., to power the process), using higher temperatures and well-controlled systems, locating facilities close to precursor sources, ensuring proper post-treatment disposal, and carefully selecting precursors, respectively. Fortunately, the negative impacts associated with biochar production, such as energy consumption and gas emissions, represent only a minor fraction of the overall life cycle assessment. The process often yields a net environmental benefit owing to carbon sequestration and energy substitution.

6. Future Directions and Challenges

The future perspective of biochar derived from agricultural wastes for wastewater remediation is highly promising, positioning it as a key sustainable technology within the circular economy. This topic converts agricultural residues (a waste management problem) into a value-added adsorbent and provides a cost-effective, eco-friendly alternative to conventional, energy-intensive wastewater treatment methods. The future studies in this field should move beyond simple, pristine biochar to highly engineered, designer materials for specific contaminants and applications. The most urgent research gaps include pilot-scale studies, the applicability of biochar to the complexity of real wastewater, standardization of biochar quality criteria, and regulatory barriers. The additional aspects are related to (i) the advanced biochar modification to fabricate nanocomposites and the development of innovative biochar (e.g., magnetic biochar) with great reusability, good recyclability, and easy separation from the adsorption systems; (ii) the investigation of the fixed bed adsorption and promotion of the biochar’s regeneration and recycling properties; (iii) the chemical and physical activation utilizing chemical and physical activators to optimize the porosity and surface chemistry for targeted contaminants; (iv) developing ‘intelligent’ or ‘smart’ biochar that can adjust their properties (like surface charge) in response to environmental conditions (e.g., Ph), allowing for better contaminant retention in dynamic systems; (v) removal of emerging contaminants such as pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and microplastics, where traditional treatments often fall short; (vi) recovering valuable resources like nutrients (N and P) and heavy metals from wastewater, turning a pollution problem into a resource opportunity; (vii) synergistic integrating biochar not just as a standalone adsorbent but within hybrid systems, for instance, microbial fuel cells (biochar can serve as an electrode material to enhance electricity generation and pollutant breakdown simultaneously), membrane bioreactors (using biochar as a component in membranes or as a pre-treatment to reduce fouling and improve effluent quality), and algal biochar systems (utilizing biochar to support microalgae growth for enhanced bioremediation, CO2 capture, and even biofuel production); (viii) estimation of the feasibility of the long-term use of biochar in biofilters; (ix) simultaneous adsorption, decomposition, and mineralization via biodegradation using bacterial-loaded biochar, photocatalysis or sonocatalysis using biochar as catalysts, and activation of peroxymonosulfate or persulfate for wastewater purification [6,15,21,38,98]; (x) optimizing biochar production technologies through innovations in pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal carbonization to improve energy efficiency, enhance scalability, and ensure consistent biochar quality from diverse agricultural feedstocks; (xi) integrating machine learning and artificial intelligence with biochar production and application to accurately predict material properties, optimize treatment systems, and manage regeneration/disposal; and (xii) establishing closed-loop systems where agricultural waste is converted to biochar, used in wastewater treatment, and then the spent biochar (rich in recovered nutrients/carbon) is safely reused as a soil amendment, further supporting sustainable agriculture.

Several challenges should be overcome for scaling up and commercialization: (i) Material variability. Establishing standardized protocols for biochar production, characterization, and quality control to ensure consistent performance. (ii) Regeneration and disposal. Developing cost-effective and environmentally friendly regeneration methods (e.g., chemical, thermal, biological) for spent biochar to ensure its long-term reusability and prevent secondary pollution. (iii) Scalability and cost. Reducing production and modification energy costs to make engineered biochar competitive with established commercial adsorbents like activated carbon on a large scale. (iv) Long-term ecotoxicity. Conducting extensive long-term field studies and life cycle assessments to fully understand the environmental stability and potential ecological risks of modified biochar.

7. Conclusions

Various agricultural wastes are valorized to produce biochar, which enables efficient decontamination and recovery of valuable compounds from a range of wastewaters. Such biochar has specific surface areas and pore diameters of 1.7–429.0 m2/g and 1.1–21.0 nm, respectively. Most adsorption capacities of biochar in real and synthetic wastewater streams are in the ranges of 13–140 mg/g (or 0.5–582.0 mg/L) and 3–241 mg/g, respectively. Pore trapping, ion exchange/surface complexation, electrostatic attraction/pore filling, and π-π interactions are commonly the primary mechanisms for the adsorption of N/P in municipal wastewater, heavy metals/phenols/complex organics in industrial wastewater, ammonium/ammonia/nitrates/antibiotics in livestock wastewater, and dyes/surfactants in textile wastewater by such biochar, respectively. Urgent challenges include material variability, standardization of biochar quality criteria, regeneration, scalability, and long-term ecotoxicity. Further validation and scale-up are essential for the practical implementation of agricultural waste-derived biochar in wastewater remediation.

Author Contributions

P.L.: data curation, writing—original draft preparation, investigation, and validation; L.B.: investigation, methodology, and supervision; G.C.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—reviewing and editing, etc. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the University of Turin (Rilo 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BOD | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| PhL | Ph of liquids |

| pHPZC | Point of zero charge |

| TC | Total carbon |

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| TDS | Total dissolved solids |

| TS | The total solids |

| TSS | Total suspended solids |

| TVSS | Total volatile suspended solids |

References

- Shi, T.-T.; Yang, B.; Hu, W.-G.; Gao, G.-J.; Jiang, X.-Y.; Yu, J.-G. Garlic Peel-Based Biochar Prepared under Weak Carbonation Conditions for Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue from Wastewater. Molecules 2024, 29, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshakhs, F.; Gijjapu, D.R.; Aminul Islam, M.; Akinpelu, A.A.; Nazal, M.K. A Promising Palm Leaves Waste-Derived Biochar for Efficient Removal of Tetracycline from Wastewater. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1296, 136846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Ding, S.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Liu, G.; Fang, J. Recent Advances and Perspectives of Biochar for Livestock Wastewater: Modification Methods, Applications, and Resource Recovery. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlović, I.; Hgeig, A.; Novaković, M.; Gvoić, V.; Ubavin, D.; Petrović, M.; Kurniawan, T.A. Valorizing Date Seeds into Biochar for Pesticide Removal: A Sustainable Approach to Agro-Waste-Based Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, X. Magnetic Coconut Shell Biochar/Sodium Alginate Composite Aerogel Beads for Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue from Wastewater: Synthesis, Characterization, and Mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 284, 137945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Mo, Y.; Lin, X.; Gao, S.; Chen, M. Efficient Removal of Atrazine in Wastewater by Washed Peanut Shells Biochar: Adsorption Behavior and Biodegradation. Process Biochem. 2025, 154, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Lee, J.; Cravotto, G. Sonocatalytic Degrading Antibiotics over Activated Carbon in Cow Milk. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Cavitational Technologies for the Removal of Antibiotics in Water and Milk. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Turin, Turin, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Cannizzo, F.T.; Mantegna, S.; Cravotto, G. Removal of Antibiotics from Milk via Ozonation in a Vortex Reactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 129642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Cravotto, G. Sonolytic Degradation Kinetics and Mechanisms of Antibiotics in Water and Cow Milk. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 99, 106518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M.; Liao, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, S.; Liao, W.; Zhao, X. Removal of Anthracene from Vehicle-Wash Wastewater through Adsorption Using Eucalyptus Wood Waste-Derived Biochar. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 317, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizkallah, B.M.; Galal, M.M.; Matta, M.E. Characteristics of Tetracycline Adsorption on Commercial Biochar from Synthetic and Real Wastewater in Batch and Continuous Operations: Study of Removal Mechanisms, Isotherms, Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Desorption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Ye, J. Comparison Study of Naphthalene Adsorption on Activated Carbons Prepared from Different Raws. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 2086–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Ge, X.; Yang, X. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Microwave-Assisted Activation of Starch-Derived Carbons as an Effective Adsorbent for Naphthalene Removal. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 11696–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Manzoli, M.; Cravotto, G. Magnetic Biochar Generated from Oil-Mill Wastewater by Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Treatment for Sonocatalytic Antibiotic Degradation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 114996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cui, Z.; Ding, H.; Wan, Y.; Tang, Z.; Gao, J. Cost-Effective Biochar Produced from Agricultural Residues and Its Application for Preparation of High Performance Form-Stable Phase Change Material via Simple Method. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin, T.; Komala, P.S.; Mera, M.; Zulkarnaini, Z.; Jamil, Z. Coconut Shell Biochar as a Sustainable Approach for Nutrient Removal from Agricultural Wastewater. J. Water Land Dev. 2025, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konneh, M.; Wandera, S.M.; Murunga, S.I.; Raude, J.M. Adsorption and Desorption of Nutrients from Abattoir Wastewater: Modelling and Comparison of Rice, Coconut and Coffee Husk Biochar. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Ali Baig, S.; Shams, D.F.; Hussain, S.; Hussain, R.; Qadir, A.; Maryam, H.S.; Khan, Z.U.; Sattar, S.; Xu, X. Dye Wastewater Treatment Using Wheat Straw Biochar in Gadoon Industrial Areas of Swabi, Pakistan. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2022, 7, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.; Nizamuddin, S.; Griffin, G.; Selvakannan, P.; Mubarak, N.M.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Synthesis and Characterization of Rice Husk Biochar via Hydrothermal Carbonization for Wastewater Treatment and Biofuel Production. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, P.T.; Jitae, K.; Al Tahtamouni, T.M.; Le Minh Tri, N.; Kim, H.-H.; Cho, K.H.; Lee, C. Novel Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by Biochar Derived from Rice Husk toward Oxidation of Organic Contaminants in Wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 33, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Chu, T.T.H.; Nguyen, D.K.; Le, T.K.O.; Obaid, S.A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Kim, J.; Nguyen, M.V. Alginate-Modified Biochar Derived from Rice Husk Waste for Improvement Uptake Performance of Lead in Wastewater. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, Q.; Nguyen, K.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Duong, T.D.; Dong, M.N.T.; Tran, H.M.T.; Van Hoang, H. Evaluation of Adsorption and Desorption of Wastewater onto Rice Husk Biochar on the Course of Hydroponic Nutrient Production. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 18615–18628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, Q.; Nguyen, K.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Van Hoang, H.; Duong, T.D.; Dong, M.T.N.; Tran, H.T.M. Transforming Domestic Wastewater into Hydroponic Nutrients Using Corncob-Derived Biochar Adsorption. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 3708–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Bojmehrani, A.; Zare, E.; Zare, Z.; Hosseini, S.M.; Bakhshabadi, H. Optimization of Antioxidant Extraction Process from Corn Meal Using Pulsed Electric Field-subcritical Water. J. Food Process Preserv. 2021, 45, e15458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walanda, D.K.; Anshary, A.; Napitupulu, M.; Walanda, R.M. The Utilization of Corn Stalks as Biochar to Adsorb BOD and COD in Hospital Wastewater. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynam. 2022, 17, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, L.; Li, W.; Yao, H.; Luo, H.; Liu, G.; Fang, J. Corn Stover Waste Preparation Cerium-Modified Biochar for Phosphate Removal from Pig Farm Wastewater: Adsorption Performance and Mechanism. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 212, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.T.H.; Nguyen, M.V. Improved Cr (VI) Adsorption Performance in Wastewater and Groundwater by Synthesized Magnetic Adsorbent Derived from Fe3O4 Loaded Corn Straw Biochar. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, F.; Slijepcevic, A.; Piantini, U.; Frey, U.; Abiven, S.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Charlet, L. Real Wastewater Micropollutant Removal by Wood Waste Biomass Biochars: A Mechanistic Interpretation Related to Various Biochar Physico-Chemical Properties. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 17, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Guo, H.; Jiang, D.; Cheng, S.; Xing, B.; Meng, W.; Fang, J.; Xia, H. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Rape Stalk to Prepare Biochar for Heavy Metal Wastewater Removal. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 134, 109794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Chen, B.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, L.; Schnoor, J.L. Insight into Multiple and Multilevel Structures of Biochars and Their Potential Environmental Applications: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 5027–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijitkosum, S. Biochar Derived from Agricultural Wastes and Wood Residues for Sustainable Agricultural and Environmental Applications. Int. Soil. Water Conserv. Res. 2022, 10, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasubramanian, K.; Thangagiri, B.; Sakthivel, A.; Dhaveethu Raja, J.; Seenivasan, S.; Vallinayagam, P.; Madhavan, D.; Malathi Devi, S.; Rathika, B. A Complete Review on Biochar: Production, Property, Multifaceted Applications, Interaction Mechanism and Computational Approach. Fuel 2021, 292, 120243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainaina, S.; Awasthi, M.K.; Sarsaiya, S.; Chen, H.; Singh, E.; Kumar, A.; Ravindran, B.; Awasthi, S.K.; Liu, T.; Duan, Y.; et al. Resource Recovery and Circular Economy from Organic Solid Waste Using Aerobic and Anaerobic Digestion Technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Ghosh, G.K.; Avasthe, R. Conversion of Crop, Weed and Tree Biomass into Biochar for Heavy Metal Removal and Wastewater Treatment. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 4901–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Barge, A.; Boffa, L.; Martina, K.; Cravotto, G. Determination of Trace Antibiotics in Water and Milk via Preconcentration and Cleanup Using Activated Carbons. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmoudi, M.A.; Abid, N.; Feki, F.; Karray, F.; Chamkha, M.; Sayadi, S. Study of Olive Mill Wastewater Adsorption onto Biochar as a Pretreatment Option within a Fully Integrated Process. EuroMediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2024, 9, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fito, J.; Abewaa, M.; Nkambule, T. Magnetite-Impregnated Biochar of Parthenium Hysterophorus for Adsorption of Cr(VI) from Tannery Industrial Wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, M.; Babaee, S.; Worku, A.; Msagati, T.A.M.; Nure, J.F. The Development of Giant Reed Biochar for Adsorption of Basic Blue 41 and Eriochrome Black T. Azo Dyes from Wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Illankoon, W.A.M.A.N.; Milanese, C.; Calatroni, S.; Caccamo, F.M.; Medina-Llamas, M.; Girella, A.; Sorlini, S. Preparation and Modification of Biochar Derived from Agricultural Waste for Metal Adsorption from Urban Wastewater. Water 2024, 16, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Zhang, X.; Varjani, S.; Liu, Y. Feasibility Study on a New Pomelo Peel Derived Biochar for Tetracycline Antibiotics Removal in Swine Wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hu, H.; Wu, X.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, R.; Zheng, H. Coupling of Biochar-Mediated Absorption and Algal-Bacterial System to Enhance Nutrients Recovery from Swine Wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 701, 134935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, B.; Sommer-Márquez, A.; Ordoñez, P.E.; Bastardo-González, E.; Ricaurte, M.; Navas-Cárdenas, C. Synthesis Methods, Properties, and Modifications of Biochar-Based Materials for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Resources 2024, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Liu, P.; Li, Q.; Yang, R.; Yang, X. Competitive Adsorption of Naphthalene and Phenanthrene on Walnut Shell Based Activated Carbon and the Verification via Theoretical Calculation. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 10703–10714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashebir, H.; Nure, J.F.; Worku, A.; Msagati, T.A.M. Prosopis Juliflora Biochar for Adsorption of Sulfamethoxazole and Ciprofloxacin from Pharmaceutical Wastewater. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Du, W.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Kang, W. Adsorption Characteristics and Removal Mechanism of Quinoline in Wastewater by Walnut Shell-Based Biochar. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Mo, H.; Gao, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. Adsorption of Crystal Violet from Wastewater Using Alkaline-Modified Pomelo Peel-Derived Biochar. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonam; Bharti, S.K.; Kumar, N. Kinetic Study of Lead (Pb2+) Removal from Battery Manufacturing Wastewater Using Bagasse Biochar as Biosorbent. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.; Lan, X.; Guo, J.; Cai, A.; Liu, P.; Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Lei, Y. Preparation of Iron/Calcium-Modified Biochar for Phosphate Removal from Industrial Wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illankoon, W.A.M.A.N.; Milanese, C.; Karunarathna, A.K.; Liyanage, K.D.H.E.; Alahakoon, A.M.Y.W.; Rathnasiri, P.G.; Collivignarelli, M.C.; Sorlini, S. Evaluating Sustainable Options for Valorization of Rice By-Products in Sri Lanka: An Approach for a Circular Business Model. Agronomy 2023, 13, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, B.; Petropoulos, E.; Duan, J.; Yang, L.; Xue, L. The Potential of Biochar as N Carrier to Recover N from Wastewater for Reuse in Planting Soil: Adsorption Capacity and Bioavailability Analysis. Separations 2022, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuff, A.S.; Popoola, L.T.; Ibrahim, I.S. Adsorptive Removal of Anthraquinone Dye from Wastewater Using Silica-Nitrogen Reformed Eucalyptus Bark Biochar: Parametric Optimization, Isotherm and Kinetic Studies. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 166, 105503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.J.; Sánchez-Albores, R.; Ashok, A.; Escorcia-García, J.; Cruz-Salomón, A.; Reyes-Vallejo, O.; Sebastian, P.J.; Velumani, S. Carica Papaya Seed- Derived Functionalized Biochar: An Environmentally Friendly and Efficient Alternative for Dye Adsorption. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.J.; Reyes-Vallejo, O.; Sánchez-Albores, R.M.; Sebastian, P.J.; Cruz-Salomón, A.; Hernández-Cruz, M.d.C.; Montejo-López, W.; González Reyes, M.; Serrano Ramirez, R.d.P.; Torres-Ventura, H.H. Activated Biochar from Pineapple Crown Biomass: A High-Efficiency Adsorbent for Organic Dye Removal. Sustainability 2024, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Vaccari, M.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Amrane, A.; Rtimi, S. Mechanisms and Adsorption Capacities of Biochar for the Removal of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants from Industrial Wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 3273–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, M.; Keskin, M.E.; Mazlum, S.; Mazlum, N. Hg(II) and Pb(II) Adsorption on Activated Sludge Biomass: Effective Biosorption Mechanism. Int. J. Min. Process 2008, 87, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zeng, W.; Xu, H.; Li, S.; Peng, Y. Adsorption Removal and Reuse of Phosphate from Wastewater Using a Novel Adsorbent of Lanthanum-Modified Platanus Biochar. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 140, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Tan, W.; Liu, X.; Jin, Y.; Qu, J. Adsorption of Cd(II) onto Auricularia Auricula Spent Substrate Biochar Modified by CS2: Characteristics, Mechanism and Application in Wastewater Treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 132882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Cravotto, G. In Situ Modification of Activated Carbons by Oleic Acid under Microwave Heating to Improve Adsorptive Removal of Naphthalene in Aqueous Solutions. Processes 2021, 9, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.O.; Yaqoob, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.N.M.; Ahmad, A.; Alshammari, M.B. Introduction of Adsorption Techniques for Heavy Metals Remediation. In Emerging Techniques for Treatment of Toxic Metals from Wastewater; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, M.; Niu, B.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Jiang, K. Rotten Sugarcane Bagasse Derived Biochars with Rich Mineral Residues for Effective Pb (II) Removal in Wastewater and the Tech-Economic Analysis. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 132, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaime, G.; Baçaoui, A.; Yaacoubi, A.; Lübken, M. Biochar for Wastewater Treatment—Conversion Technologies and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewoye, T.L.; Ogunleye, O.O.; Abdulkareem, A.S.; Salawudeen, T.O.; Tijani, J.O. Optimization of the Adsorption of Total Organic Carbon from Produced Water Using Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebrehiwot, H.; Fynn, R.; Morris, C.; Kirkman, K. Shoot and Root Biomass Allocation and Competitive Hierarchies of Four South African Grass Species on Light, Soil Resources and Cutting Gradients. Afr. J. Range Forage Sci. 2006, 23, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Lei, Z.; Zheng, B.; Xia, H.; Su, Y.; Ali, K.M.Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Beryllium Adsorption from Beryllium Mining Wastewater with Novel Porous Lotus Leaf Biochar Modified with PO43−/NH4+ Multifunctional Groups (MLLB). Biochar 2024, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdeha, E. Biochar-Based Nanocomposites for Industrial Wastewater Treatment via Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation and the Parameters Affecting These Processes. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 23293–23318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motasemi, F.; Afzal, M.T. A Review on the Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis Technique. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, R.; Gopinath, K.P.; Kumar, P.S. Adsorptive Separation of Toxic Metals from Aquatic Environment Using Agro Waste Biochar: Application in Electroplating Industrial Wastewater. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soundari, L.; Prasanna, K. Optimum Usage of Biochar Derived from Agricultural Biomass in Removing Organic Pollutant Present in Pharmaceutical Wastewater. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2025, 10, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutarut, P.; Cheirsilp, B.; Boonsawang, P. The Potential of Oil Palm Frond Biochar for the Adsorption of Residual Pollutants from Real Latex Industrial Wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-J.; Jiang, H.; Yu, H.-Q. Development of Biochar-Based Functional Materials: Toward a Sustainable Platform Carbon Material. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12251–12285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.W.; Mubarak, N.M.; Sahu, J.N.; Abdullah, E.C. Microwave Induced Synthesis of Magnetic Biochar from Agricultural Biomass for Removal of Lead and Cadmium from Wastewater. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 45, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Boffa, L.; Chemat, A.; Cravotto, D. Review and Perspectives on the Role of Microwaves in Membrane Processes. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.S.; Jalil, A.A.; Izzuddin, N.M.; Bahari, M.B.; Hatta, A.H.; Kasmani, R.M.; Norazahar, N. Recent Advances in Lignocellulosic Biomass-Derived Biochar-Based Photocatalyst for Wastewater Remediation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 163, 105670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Goldfarb, J.L. Heterogeneous Biochars from Agriculture Residues and Coal Fly Ash for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Coking Wastewater. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 16018–16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, N.-T.; Do, K.-U. Insights into Adsorption of Ammonium by Biochar Derived from Low Temperature Pyrolysis of Coffee Husk. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 2193–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lap, B.Q.; Thinh, N.V.D.; Hung, N.T.Q.; Nam, N.H.; Dang, H.T.T.; Ba, H.T.; Ky, N.M.; Tuan, H.N.A. Assessment of Rice Straw–Derived Biochar for Livestock Wastewater Treatment. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2021, 232, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fseha, Y.H.; Shaheen, J.; Sizirici, B. Phenol Contaminated Municipal Wastewater Treatment Using Date Palm Frond Biochar: Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. Emerg. Contam. 2023, 9, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Philip, L. Sustainability Assessment of Acid-Modified Biochar as Adsorbent for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products from Secondary Treated Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Maitra, J.; Khan, K.A. Development of Biochar and Chitosan Blend for Heavy Metals Uptake from Synthetic and Industrial Wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 4525–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Han, J.; Choi, Y.-K.; Park, S.; Lee, S.H. Reswellable Alginate/Activated Carbon/Carboxymethyl Cellulose Hydrogel Beads for Ibuprofen Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 249, 126053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Luo, G.; Li, X.; Tian, H.; Yao, H. Theoretical Research on Role of Sulfur Allotropes on Activated Carbon Surface in Adsorbing Elemental Mercury. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 404, 126639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghenaatian, H.R.; Shakourian-Fard, M.; Kamath, G. The Effect of Sulfur and Nitrogen/Sulfur Co-Doping in Graphene Surface on the Adsorption of Toxic Heavy Metals (Cd, Hg, Pb). J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 13175–13189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X.; Abbas, G. Phosphorus Removal Using Ferric–Calcium Complex as Precipitant: Parameters Optimization and Phosphorus-Recycling Potential. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 268, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumi, A.G.; Ibrahim, M.G.; Fujii, M.; Nasr, M. Petrochemical Wastewater Treatment by Eggshell Modified Biochar as Adsorbent: Atechno-Economic and Sustainable Approach. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2022, 2022, 2323836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Duan, W.; Peng, H.; Pan, B.; Xing, B. Functional Biochar and Its Balanced Design. ACS Environ. Au 2022, 2, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsawy, T.; Rashad, E.; El-Qelish, M.; Mohammed, R.H. A Comprehensive Review on the Chemical Regeneration of Biochar Adsorbent for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. NPJ Clean Water 2022, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Ou, Y.; Khanal, S.K.; Sun, L.; Shu, W.; Lu, H. Biochar-Based Strategies for Antibiotics Removal: Mechanisms, Factors, and Application. ACS EST Eng. 2024, 4, 1256–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeonuegbu, B.A.; Machido, D.A.; Whong, C.M.Z.; Japhet, W.S.; Alexiou, A.; Elazab, S.T.; Qusty, N.; Yaro, C.A.; Batiha, G.E.-S. Agricultural Waste of Sugarcane Bagasse as Efficient Adsorbent for Lead and Nickel Removal from Untreated Wastewater: Biosorption, Equilibrium Isotherms, Kinetics and Desorption Studies. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruthi, S.; Vishalakshi, B. Hybrid Banana Pseudo Stem Biochar- Poly (N-Hydroxyethylacrylamide) Hydrogel and Its Magnetic Nanocomposite for Effective Remediation of Dye from Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egila, J.N.; Dauda, B.E.N.; Iyaka, Y.A.; Jimoh, T. Agricultural Waste as a Low Cost Adsorbent for Heavy Metal Removal from Wastewater. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2011, 6, 2152–2157. [Google Scholar]

- El Ouassif, H.; Gayh, U.; Ghomi, M.R. Biochar Production from Agricultural Waste (Corncob) to Remove Ammonia from Livestock Wastewater. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2024, 13, 132409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, J.; Galinato, S.; Granatstein, D.; Garcia-Pérez, M. Economic Tradeoff between Biochar and Bio-Oil Production via Pyrolysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fdez-Sanromán, A.; Pazos, M.; Rosales, E.; Sanromán, M.A. Unravelling the Environmental Application of Biochar as Low-Cost Biosorbent: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, J.L.; Lehmann, J. Energy Balance and Emissions Associated with Biochar Sequestration and Pyrolysis Bioenergy Production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 4152–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.Y.; Hwang, G.Y.; Um, J.B. An A Nalysis of the Influence Factors o f Farmers’ Acceptance Intention o n Low Carbon Agricultural Technology Bio-Char. J. Agric. Ext. Community Dev. 2023, 30, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, R.D.; Zhang, H.; Englund, K.; Windell, K.; Gu, H. Estimating GHG emissions from the manufacturing of field-applied biochar pellets. In Proceedings of the 59th International Convention of Society of Wood Science and Technology, Curitiba, Brazil, 6–10 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van Thuan, D.; Chu, T.T.H.; Thanh, H.D.T.; Le, M.V.; Ngo, H.L.; Le, C.L.; Thi, H.P. Adsorption and Photodegradation of Micropollutant in Wastewater by Photocatalyst TiO2/Rice Husk Biochar. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.