The Impact of Strategic Global Integration on Sustainable Human Development in Ethiopia: Disentangling the Roles of Trade and FDI

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.2. Synthesizing Empirical Evidence: Patterns and Contradictions

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source and Variables

3.1.1. Measures of Variables

Dependent Variable

- The natural logarithm of the standard Human Development Index (lnHDI): The HDI is a composite statistic of life expectancy, education, and per capita income indicators, serving as a comprehensive measure of socio-economic development as used in numerous prior studies [54,55]. It measures three main dimensions: longevity (life expectancy), educational achievement (mean and expected years of schooling), and a decent standard of living (GNI per capita).

- The natural logarithm of a modified Human Development Index (lnHDI*): This variable is constructed by recalculating the index using only the health (life expectancy) and education (mean and expected years of schooling) indices, while explicitly excluding the income component (Gross National Income, GNI). The recalculation follows the UNDP’s standard geometric mean formula. This formulation allows for the separation of direct income effects from health and education outcomes in human development.

Independent Variables

- The natural logarithm of Trade Openness (lnTOP): This is defined as lnTOP, where TOP equals the sum of exports and imports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP. This is a standard metric that reflects a nation’s degree of international trade integration [56].

- The natural logarithm of net Foreign Direct Investment (lnFDI): This is measured as net FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP. In previous studies, FDI has often served as an independent variable and is typically normalized by GDP to account for differences in country size, facilitating cross-country comparisons [28,57]. This measurement is particularly significant for developing countries, where FDI constitutes the primary source of external financing.

Control Variables

- Personal Remittances (lnREM): Measured as personal remittances received as a percentage of GDP. Remittances are a crucial source of external finance that can help reduce poverty and promote socio-economic stability [58]. Inflation (lnINF): The annual inflation rate, measured by the annual percentage change in the Consumer Price Index. It serves as a proxy for macroeconomic instability [59,60]. Inflation is chosen over other indicators (e.g., fiscal balance, exchange rate volatility) for two reasons: its direct effect on purchasing power and social welfare, and consistent data availability. Institutional Quality Index (IQI): This is a composite measure of governance effectiveness. Reference [61] identified six key dimensions of governance. To avoid potential weighting biases and account for the intercorrelations among these dimensions, this study applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to create a single composite measure that reflects overall governance quality, rather than relying on a single indicator. Combined Public Spending (lnPS): This variable measures the combined public expenditure on education and health as a percentage of the total budget, capturing direct public investment in human capital. Lastly, GDP per capita (lnGDP). This variable is included only in the modified HDI (lnHDI*) model to control for the overall level of economic development, as the income component is excluded from the dependent variable [62].

3.2. Theoretical and Empirical Model Specification

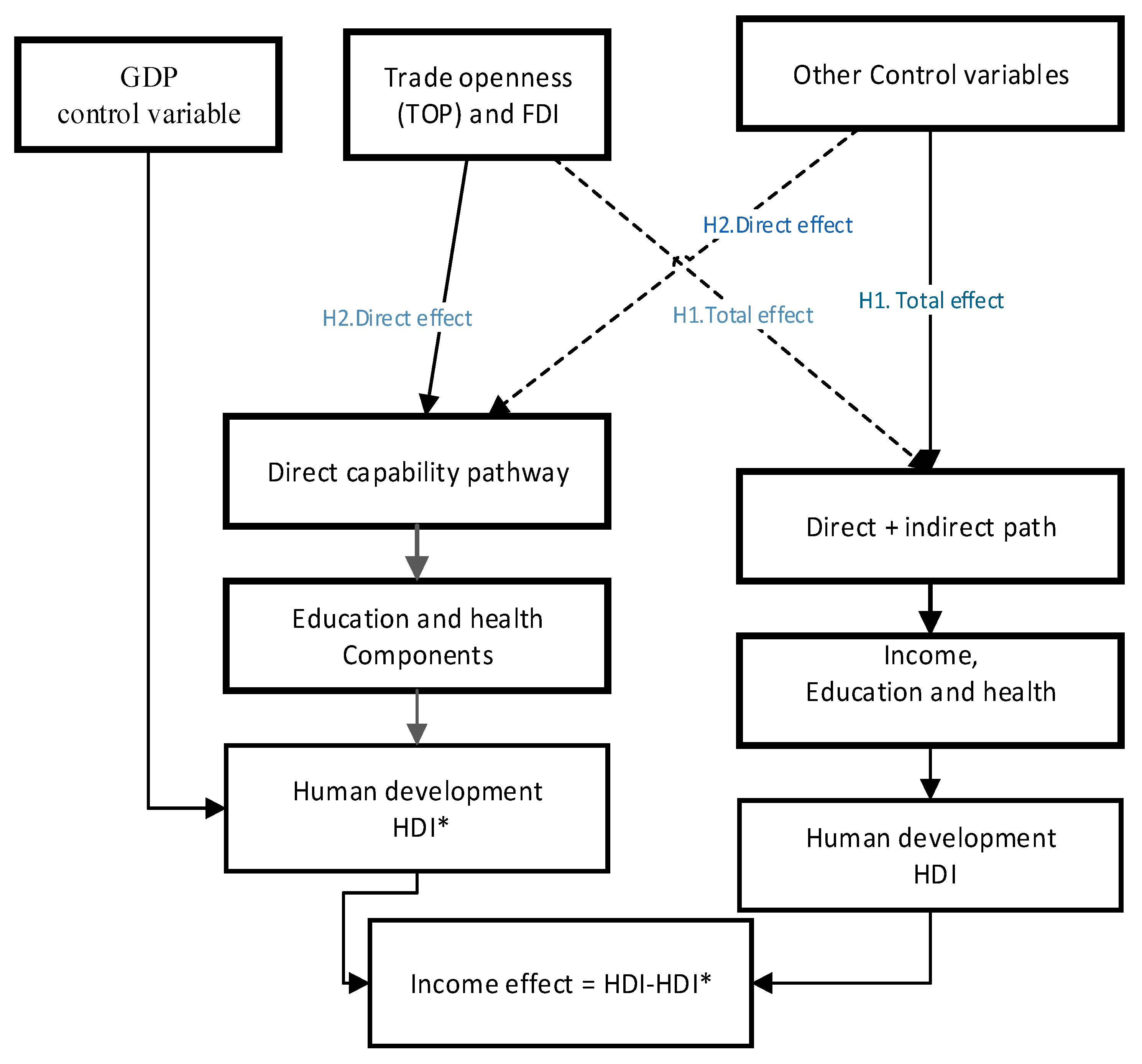

3.2.1. Theoretical Dual Pathways Models

3.2.2. Model Specification and Estimation Strategy

3.3. Econometric Procedures and Diagnostic Testing

4. Results

4.1. Pre-Estimation Diagnostics

4.1.1. Unit Root Test

4.1.2. Lag Length Selection and Cointegration Test

4.2. Long-Run Estimation and Interpretation

4.3. Short-Run Dynamics and Error Correction

5. Model Validation and Robustness Checks

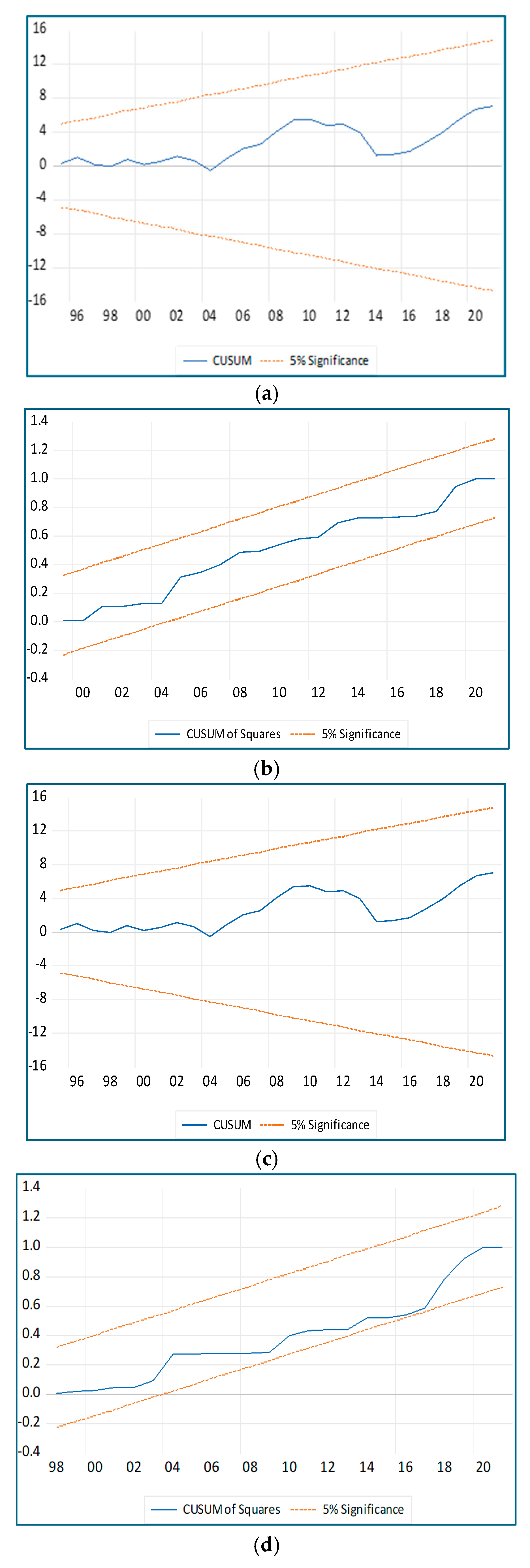

Model Stability Tests

6. Concluding Remarks

6.1. Policy Recommendations

6.2. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| LAG | LL | LR | FPE | AIC | HQIC | SRIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 102.278 | 0.001947 | 0.9468 | 0.01784 | 8.18646 | |

| 1 | 34.6331 | 273.82 | 5.1 × 10−7 | −0.343195 | −0.084939 | 1.09662 |

| 2 | 68.0952 | 66.924 | 3.4 × 10−7 | −0.970016 | −0.185104 | 1.66965 |

| 3 | 108.612 | 81.034 | 2.0 × 10−7 | −2.11942 | −0.977732 | 1.7201 |

| 4 | 193.204 | 169.18 * | 1.4 × 10−8 * | −6.53365 * | −5.03518 * | 1.49428 * |

Appendix B

| Lag | LL | LR | FPE | AIC | HQIC | SRIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −102.164 | 0.001928 | 7.93811 | 8.00946 | 8.17808 | |

| 1 | 61.2139 | 326.76 | 7.1 × 10−8 | −2.31214 | −1.88401 | −0.872325 |

| 2 | 95.4753 | 68.523 | 4.4 × 10−8 | −2.99817 | 2.21326 | −0.3585 |

| 3 | 137.666 | 84.381 | 2.3 × 10−8 | −4.27154 | −3.12985 | −0.432025 |

| 4 | 204.789 | 134.25 * | 5.8 × 10−9 * | −7.39178 * | −5.89331 * | −2.35241 * |

References

- Lind, N. A development of the human development index. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 146, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornia, G.A.; Jolly, R.; Stewart, F. Adjustment with a Human Face: Volume II: Country Case Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as capability expansion. J. Dev. Plan. 1990, 1, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, K.; Batool, S.; Shah, A. Authoritarian regimes and economic development: An empirical reflection. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2016, 55, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssepuuya, G.; Namulawa, V.; Mbabazi, D.; Mugerwa, S.; Fuuna, P.; Nampijja, Z.; Ekesi, S.; Fiaboe, K.; Nakimbugwe, D. Use of insects for fish and poultry compound feed in sub-Saharan Africa—A systematic review. J. Insects Food Feed 2017, 3, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, M.S.; Harttgen, K. What Is Driving the ‘African Growth Miracle’? National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Hodler, R. Do natural resource revenues hinder financial development? The role of political institutions. World Dev. 2014, 57, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.L. The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wyett, K. Cambodia Economic Diversificsation Pathways. In Cambodia’s New Growth Strategy—An Assessment of Medium and Long-term Growth for Resilient, Inclusive, and Sustainable Development; CDRI: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, J.; Gupta, V.; Shrawan, A. Economic Growth and Human Development in India–Are States Converging? Indian Public Policy Rev. 2024, 5, 94–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Siqueira, J.H.; Mtewa, A.G.; Fabriz, D.C. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). In International Conflict and Security Law: A Research Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 761–777. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeiwu, S. The Nexus of Structural Adjustment, Economic Growth and Sustainability: The Case of Ethiopia. In Financial Crises, Poverty and Environmental Sustainability: Challenges in the Context of the SDGs and COVID-19 Recovery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J. Human development is economic development. In Proceedings of the Larger Community Foundations Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–24 February 2017; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A.; Quinlivan, G. A panel data analysis of the impact of trade on human development. J. Socio-Econ. 2006, 35, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Shabbir, M.S.; Saleem, S.; Yahya Khan, G.; Abbasi, B.A.; Lopez, L.B. An empirical analysis among foreign direct investment, trade openness and economic growth: Evidence from the Indian economy. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2023, 12, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menamo, M.D. Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Economic growth of Ethiopia A Time Series Empirical Analysis, 1974–2011. Master’s Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wondimu, M. An empirical investigation of the impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth in Ethiopia. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2023, 11, 2281176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, H.; Hakimi, A. Trade openness, foreign direct investment, and human development: A panel cointegration analysis for MENA countries. Int. Trade J. 2022, 36, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.I. FDI and economic development in Africa. In Proceedings of the ADB/AERC International [Online], Tunis, Tunisia, 22–24 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, P. Does trade liberalization reduce child mortality in low-and middle-income countries? A synthetic control analysis of 36 policy experiments, 1963–2005. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 205, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novignon, J.; Atakorah, Y.B.; Djossou, G.N. How does the health sector benefit from trade openness? Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2018, 30, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, H.; Helmi, H. Financial development and human development: A non-linear analysis for Oil-exporting and Oil-importing countries in MENA region. Econ. Bull. 2019, 39, 2484–2498. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, D.K.; Jones, A.P.; Goryakin, Y.; Suhrcke, M. Is foreign direct investment good for health in low and middle income countries? An instrumental variable approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 181, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keho, Y. The impact of trade openness on economic growth: The case of Cote d’Ivoire. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2017, 5, 1332820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elistia, E.; Syahzuni, B.A. The correlation of the human development index (HDI) towards economic growth (GDP per capita) in 10 ASEAN member countries. Jhss (J. Humanit. Soc. Stud.) 2018, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, S.A.; Kamaruddin, M.N. Examining the relationship between human development index and socio-economic variables: A panel data analysis. J. Int. Bus. Econ. Entrep. 2018, 3, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Taqi, M.; e Ali, M.S.; Parveen, S.; Babar, M.; Khan, I.M. An analysis of human development index and economic growth. A case study of Pakistan. Irasd J. Econ. 2021, 3, 261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Gökmenoğlu, K.K.; Apinran, M.O.; Taşpınar, N. Impact of foreign direct investment on human development index in Nigeria. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2018, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, Y.; Gündüz, M. The impact of foreign direct investment inflows and trade liberalization on human capital development in EU transition economies. Online J. Model. New Eur. 2020, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Trade and human development: Case of ASEAN. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int. 2017, 9, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Onakoya, A.; Johnson, B.; Ogundajo, G. Poverty and trade liberalization: Empirical evidence from 21 African countries. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2019, 32, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiani, S.; Knack, S.; Xu, L.C.; Zou, B. The effect of aid on growth: Evidence from a quasi-experiment. J. Econ. Growth 2017, 22, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A.; Langlotz, S.; Marchesi, S. Information transmission and ownership consolidation in aid programs. Econ. Inq. 2017, 55, 1671–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebresilassie, B.A.; Legesse, T.; Gebre, G.G. Impact of foreign aid on economic growth in Ethiopia. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 5288–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, C.A. The relationship between aid and economic growth of developing countries: Does institutional quality and economic freedom matter? Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2062092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, T.; Tilahun, S. Predictability of foreign aid and economic growth in Ethiopia. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2098606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.Z.; Arzu, S. The role of remittances on human development: Evidence from developing countries. Bull. Bus. Econ. (BBE) 2017, 6, 74–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yadeta, D.B.; Hunegnaw, F.B. Effect of international remittance on economic growth: Empirical evidence from Ethiopia. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2022, 23, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Nadeem, M.I.; Ahmed, K.; Hassan, I.; Eldin, S.M.; Ghamry, N.A. Is Greenfield investment improving welfare: A quantitative analysis for Latin American and Caribbean developing countries. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Rehman, H.U. Macroeconomic instability and its impact on gross domestic product: An empirical analysis of Pakistan. Pak. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2015, 53, 285–316. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Kwilinski, A. Green development of the country: Role of macroeconomic stability. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 2273–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ganapati, S. Do transparency mechanisms reduce government corruption? A meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2023, 89, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, F.; Kartal, M.T.; Kılıç Depren, S.; Depren, Ö. Asymmetric effect of economic policy uncertainty, political stability, energy consumption, and economic growth on CO2 emissions: Evidence from G-7 countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 47422–47437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddafa, T. The Effects of Domestic Private Investment on Ethiopian Economic Growth: Time Series Analysis. Int. J. Financ. Insur. Risk Manag. 2023, 13, 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gizaw, D. The impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth. The case of Ethiopia. J. Poverty Investig. Dev. 2015, 15, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bedasa, Z.; Alemun, M. Economic Growth Nexus Trade Liberalization in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Johnson’s Multivariate Cointegration Analysis. Int. J. Latest Res. Eng. Technol. (IJLRET) 2017, 3, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe, T.H. The Dynamics of Trade Liberalization and Economic Growth of Ethiopia: A Vector Error Correction (VEC) Model Approach. Int. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 8, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Pinglu, C.; Hussain, S.I.; Ullah, A.; Qian, N. Does regional integration matter for sustainable economic growth? Fostering the role of FDI, trade openness, IT exports, and capital formation in BRI countries. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M.; Halicioglu, F. Turkish trade in eight service categories and role of the exchange rate. Econ. Change Restruct. 2025, 58, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Sim, N.; Zhao, H. Does FDI actually affect income inequality? Insights from 25 years of research. J. Econ. Surv. 2020, 34, 630–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, L.; Pilling, D. My Model Is Capitalism’: Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Plans Telecoms Privatization. Financ. Times 2019, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C.T. The meaning and uses of privatization: The case of the Ethiopian developmental state. Africa 2022, 92, 602–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Governance Indicators. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators/interactive-data-access (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Raza, A.; Azam, M.; Tariq, M. The impact of greenfield-FDI on socio-economic development of Pakistan. Econ. J. High. Sch. Econ. 2020, 24, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Khan, A.Q.; Zafeiriou, E.; Arabatzis, G. Socio-economic determinants of energy consumption: An empirical survey for Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1556–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanıkkaya, H.; Altun, A.; Tat, P. The impacts of openness and global value chains on the performance of Turkish sectors. Panoeconomicus 2024, 71, 265–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboye, F.B.; Osabohien, R.; Olokoyo, F.O.; Matthew, O.; Adediran, O. Institutional quality, foreign direct investment, and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Khoso, I.; Taraki, M. Role of macroeconomic indicators and strategic management in Afghanistan’s economic growth. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2024, 6, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.; Qureshi, I.A. Income inequality and macroeconomic instability. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2021, 25, 758–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, B.N.; Odhiambo, N.M.; Owusu, E.L. Stock Market Development and Economic Growth in African Countries. In Finance for Sustainable Development in Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues1. Hague J. Rule Law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaid, S.T.; Waheed, A. Contribution of international trade in human development of Pakistan. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 1155–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous technological change. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98, S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as freedom. Dev. Pract. 2000, 10, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Hao, F.; Hao, X.; Gozgor, G. Economic policy uncertainty, outward foreign direct investments, and green total factor productivity: Evidence from firm-level data in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenceson, J.; Chai, J.C. Financial reform and economic development in China. In Financial Reform and Economic Development in China; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- David, O.O.; Saba, C.S.; Grobler, W. Trade openness and economic prosperity in South Africa: Pre-and post-1994 analysis. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 13, 122–149. [Google Scholar]

- Visalakshmi, S.; Lakshmi, P. BRICS market nexus for cross listed stocks: A VECX* framework. J. Financ. Data Sci. 2016, 2, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Shrivastav, R.K.; Mohapatra, A.K. Dynamic linkages and integration among five emerging BRICS markets: Pre-and post-BRICS period analysis. Ann. Financ. Econ. 2022, 17, 2250018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Li, Z.; Fatema, F. The effects of sectoral trade composition on inequality: Evidence from emerging economies. Asian J. Empir. Res. 2017, 7, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magombeyi, M.T.; Odhiambo, N.M. Foreign direct investment and poverty reduction. Comp. Econ. Research. Cent. East. Eur. 2017, 20, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megbowon, E.; Mlambo, C.; Adekunle, B. Impact of china’s outward fdi on sub-saharan africa’s industrialization: Evidence from 26 countries. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2019, 7, 1681054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzel, S.; Keesoonah, L. A dynamic investigation of foreign direct investment and sectoral growth in Mauritius. Afr. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, A.M.; Ibrahim, M. Foreign direct investment, economic growth and financial sector development in Africa. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2020, 10, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.H.; Ju, Y.; Hassan, S.T. Investigating the determinants of human development index in Pakistan: An empirical analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 19294–19304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menza, S.K.; Kelbore, Z.G.; Duka, T.A.; Shano, B.K. Adequacy of governance in the link between foreign direct investment and structural transformation. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2280337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe Mamo, Y.; Mesele Sisay, A.; Dessalegn WoldeSilassie, B.; Worku Angaw, K. Corporate social responsibilities contribution for sustainable community development: Evidence from industries in Southern Ethiopia. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2024, 12, 2373540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolisah, C.P. The Question of Insecurity and Sustained Socio-Economic Development in Nigeria. Niger. J. Philos. Stud. 2022, 1, 20–42. [Google Scholar]

- The Heritage Foundation. Index of Economic Freedom: Ethiopia. 2024. Available online: https://www.heritage.org/index/country/ethiopia (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Anetor, F.O. Human capital threshold, foreign direct investment and economic growth: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Dev. Issues 2020, 19, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Z.; Mohd Amin, R. Trade and human development in OIC countries: A panel data analysis. Islam. Econ. Stud. 2013, 21, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujianto, A.E.; Dwiningtias, K.; Luksita, A.C.; Narmaditya, B.S. Human Development Index, good governance practice and export: Evidence from ASEAN countries. J. East. Eur. Cent. Asian Res. (JEECAR) 2023, 10, 468–477. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi, H.K.; Sameti, M.; Isfahani, R.D. The effect of macroeconomic instability on economic growth in Iran. Res. Appl. Econ. 2012, 4, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Notation | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Development Index | lnHDI | Log of standard HDI | UNDP |

| Modified HDI | lnHDI* | Log of HDI (health + education only) | Author’s Calculation |

| Trade Openness | lnTOP | Log of (Exports Imports)/% GDP | IMF, WDI |

| Foreign Direct Invest. | lnFDI | Log of Net FDI inflows (% of GDP) | WB, WDI |

| Economic Development | lnGDP | Log of real GDP per capita (constant 2015 $) | WB, WDI |

| Institutional Quality | IQ | Governance and Institutional Performance Index | WGI |

| Remittance | lnREM | Personal remittances received (% of GDP) | WB, WDI |

| Public spending | lnPS | Public spending (education + health sector) % of total budget | NBE, WB |

| Macroeconomic Stability | lnINF | Consumer Price Index annual % | IMF, WDI |

| Variable | At Level, I (0) | At First Difference, I (1) | Order of |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADF Statistic (p-Value) | ADF Statistic (p-Value) | Integration | |

| lnHDI | −4.920 (0.023) ** | - | 1(0) |

| lnHDI* | −1.009 (0.736) | −2.834 (0.05) ** | I (1) |

| lnTOP | −0.954 (0.767) | −4.874 (0.04) ** | I (1) |

| lnFDI | −2.611 (0.020) ** | - | I (0) |

| lnGDP | −1.312 (0.998) | −2.963 (0.048) ** | I (1) |

| IQ | −2.002(0.027) ** | - | I (0) |

| lnREM | −1.802 (0.704) | −2.027 (0.026) ** | I (1) |

| lnPS | −1.579 (0.063) | −3.232 (0.002) ** | I (1) |

| lnINF | −1.598 (0.481) | −7.253 (0.035) ** | I (1) |

| Models | F-Statics | Lower Bound 5% | Upper Bound (5%) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDI | 10.3 | 3.99 | 5.06 | Long-run relation exists |

| HDI* | 11.19 | 3.99 | 5.06 | Long-run relation exists |

| Variables | Model A: lnHDI | Model B: lnHDI* |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (p-Value) | Coefficient (p-Value) | |

| lnTOP | 0.343 (0.040) ** | 0.235 (0.007) *** |

| lnFDI | 0.214 (0.008) *** | 0.136 (0.001) *** |

| lnGDP | -------------- | 0.129 (0.000) *** |

| IQ | 0.157 (0.002) ** | 0.014 (0.335) |

| lnREM | 0.102 (0.027) ** | 0.012 (0.032) ** |

| lnPS | 0.026 (0.025) ** | 0.047 (0.295) |

| lnINF | −0.002 (0.426) | −0.018 (0.070) * |

| Constant | 0.051 (0.000) *** | 0.010 (0.034) ** |

| R-squared | 0.802 | 0.832 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.723 | 0.758 |

| Variables | HDI | HDI* | Income | % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Model A) | (Model B) | Mediated | Effect via Income | |

| lnTOP | 0.343 | 0.235 | 0.108 | 31.50% |

| lnFDI | 0.214 | 0.136 | 0.078 | 36.40% |

| Variables | Model A: lnHDI | Model B: lnHDI* |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (p-Value) | Coefficient (p-Value) | |

| ΔlnHDI (−1) | 0.232 (0.047) ** | - |

| ΔlnHDI* (−1) | - | 0.157 (0.002) *** |

| ΔlnTOP | 0.116 (0.000) *** | 0.015 (0.004) *** |

| ΔlnTOP (−1) | 0.05 (0.242) | 0.013 (0.195) |

| ΔlnFDI | 0.084 (0.044) ** | 0.035 (0.057) * |

| ΔlnGDP | - | 0.128 (0.032) ** |

| ΔIQ | 0.058 (0.046) ** | 0.014 (0.335) |

| ΔlnREM | 0.073 (0.409) | 0.026 (0.186) |

| ΔlnREM (−1) | 0.013 (0.642) | 0.003 (0.158) |

| ΔPS | 0.018 (0.028) ** | 0.012 (0.032) ** |

| ΔINF | −0.042 (0.022) ** | −0.011 (0.027) ** |

| ΔINF (−1) | −0.0012 (0.720) | −0.042 (0.022) ** |

| EC (−1) | −0.284 (0.005) *** | −0.178 (0.015) *** |

| Test | HDI Model | HDI* Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic (p-Value) | Statistic (p-Value) | Null Hypothesis | Conclusion | |

| Breusch Godfrey LM | 4.879 (0.163) | 1.930 (0.207) | No serial correlation | Not rejected |

| Breusch–Pagan | 3.970 (0.137) | 1.088 (0.580) | Homoscedasticity | Not rejected |

| Jarque–Bera | 1.695 (0.429) | 1.228 (0.541) | Normal distribution | Not rejected |

| Ramsey RESET | 0.470 (0.708) | 0.142 (0.931) | Correct functional form | Not rejected |

| DW-statistic | 2.342 | 2.184 | No serial correlation | Not rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, H.; Atnafu, M.W. The Impact of Strategic Global Integration on Sustainable Human Development in Ethiopia: Disentangling the Roles of Trade and FDI. Sustainability 2026, 18, 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010436

Huang H, Atnafu MW. The Impact of Strategic Global Integration on Sustainable Human Development in Ethiopia: Disentangling the Roles of Trade and FDI. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):436. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010436

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Huiping, and Michu Woreket Atnafu. 2026. "The Impact of Strategic Global Integration on Sustainable Human Development in Ethiopia: Disentangling the Roles of Trade and FDI" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010436

APA StyleHuang, H., & Atnafu, M. W. (2026). The Impact of Strategic Global Integration on Sustainable Human Development in Ethiopia: Disentangling the Roles of Trade and FDI. Sustainability, 18(1), 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010436