Abstract

The transition to environmentally friendly mobility inevitably requires users to use sustainable modes of transport. Rapid urbanization, along with the growing demand for efficient, inclusive, and ecological transport systems, has highlighted the urgent need for research and analysis into the acceptability and experiences of transitioning to sustainable modes of transport. This article proposes a six-step procedure to support the selection of vehicles for car-sharing fleets in cities. The analysis utilizes the Analytic Hierarchy Process method, which allows for the comparison and evaluation of five vehicle variants with different powertrains, taking into account various evaluation criteria: ecological and economic. To refine the research, criterion weights were determined based on original surveys among six car-sharing operators and eighty-seven experts in the field of decarbonization of urban transport. The results indicated that plug-in hybrid vehicles are the most advantageous option for car-sharing fleets, providing a balance between emissions, cost-effectiveness and operational flexibility. The solution obtained is in line with expectations, confirming that the proposed analytical approach is a reliable decision support tool that reduces the risk of making the wrong decision regarding the choice of powertrains.

1. Introduction

Urbanization is one of the most distinctive socioeconomic megatrends globally, exerting a lasting and significant impact on virtually all areas of life, including transportation. Currently, approximately 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, and according to forecasts, this share will increase to 60% in 2030 and to 68% in 2050 [1]. In the European Union, this process is even faster—in 2030, the share of urban population in the total population will reach 77.5%, and in 2050 almost 84% [2].

The development of cities and the changing needs of their inhabitants have led to an increase in demand for individual means of transport, especially passenger cars, which have become the dominant means of meeting the transportation needs of modern agglomerations [3]. However, this phenomenon is accompanied by serious economic, environmental, and social consequences. It is estimated that the costs of road congestion in European cities amount to approximately €80 billion annually [4]. Traffic congestion not only causes economic losses but also negatively impacts the health of residents and the natural environment. The main environmental problems in cities result from the use of petroleum-derived fuels in road transport, which leads to increased CO2 emissions, deterioration of air quality, and noise [3]. Despite the gradual reduction in emissions through the introduction of EURO standards, the majority of the urban population in Europe is still exposed to exceeded permissible concentrations of major air pollutants—in 2025, as many as 88% of European city residents were exposed to NO2 concentrations and 96% to particulate matter levels exceeding WHO health limits [5]. Data from the European Environment Agency show that PM2.5 caused 253,000 deaths in the European Union (mainly due to heart disease), while nitrogen oxides caused 52,000 deaths [6]. In response to these challenges, the European Union has strengthened its air quality policy. The new Directive 2024/2881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2024 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe (AAQD) [7] consolidates existing legislation and introduces more stringent pollutant emission limits. These include, among others, reducing the permissible annual average concentrations of PM2.5 from 20 to 10 µg/m3 and NO2 from 40 to 20 µg/m3 from 2030, which is intended to enable the achievement of levels considered harmless to health and ecosystems by 2050 [8].

The results of modeling conducted by the Transport Alliance for Clean Air [3,9] indicate that achieving these values requires comprehensive transport reforms. One proposed solution is the modernization of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle fleets or their partial electrification (from 15% to 57% depending on the vehicle type). Another example is the promotion of active, public, and shared mobility by replacing 25–50% of passenger car journeys with public transport by 2040. Other ambitious measures, such as low emission zones (LEZs), also appear to be the next stage of the transformation.

In this context, shared mobility has become one of the most dynamically developing trends in modern cities, aligning with sustainable development and emission reduction strategies [10,11]. This trend encompasses transport services that enable users to use vehicles without the need to own them [12]. The most well-known solutions include car sharing, bike sharing, ride sharing, shared micromobility, and on-demand transport [13]. These services can operate in various business models, including Business-to-Consumer (B2C), Business-to-Business (B2B), and Peer-to-Peer (P2P).

Numerous studies emphasize that shared mobility brings a number of economic, social, and environmental benefits. By reducing the number of vehicles needed to meet travel demand, it reduces road congestion and the need for parking spaces—which currently occupy up to 35–50% of urban space [14]. One car in a car-sharing system can replace 7 to 11 private vehicles, freeing up over 150 m2 of urban space [15]. Furthermore, shared fleets consist of new vehicles that meet the latest EURO standards and are replaced every 2–3 years [16], which further reduces emissions. According to [17], replacing 20% of private cars with shared vehicles can reduce CO2 emissions by 15%.

Shared mobility itself also influences changes in residents’ travel behavior. It promotes multimodal mobility by combining different modes of transport within a single trip and reduces the psychological dependence on car ownership [18]. This contributes to increased social integration and better access to transport for people without their own vehicles. An additional benefit is the economic savings resulting from the “pay-only-when-you-use” model, which is particularly evident in the case of passenger cars, as the user does not bear the costs of purchasing the vehicle, nor the costs of maintenance, repairs, or insurance [19,20].

Although the development of sustainable transport systems based on the idea of sharing is becoming one of the key directions of development in modern cities, available forecasts clearly indicate that the passenger car will remain the dominant mode of transport [21,22]. Therefore, the primary challenge in this context is research into selecting the optimal vehicle propulsion system for car-sharing fleets.

Based on this, the aim of this article is to identify the most optimal propulsion system for car-sharing vehicles integrated with existing urban transport systems. To this end, a six-stage decision-making procedure based on the AHP method was developed, taking into account ten evaluation criteria covering environmental, economic, operational, and utility aspects. The originality of the presented research lies not in the AHP method itself, but in its application to the integrated assessment of multiple types of propulsion systems used in car-sharing fleets from a sustainable development perspective.

This study, for the first time, combines quantitative analysis with expert consultations from car-sharing operators and urban transport decarbonization specialists. This empirical approach enables the identification of the drivetrain configuration that best balances environmental and operational efficiency under real-world fleet operating conditions. Previous studies using MCDA methods such as TOPSIS, PROMETHEE, and fuzzy AHP analysis have focused primarily on vehicle technology assessments or general sustainability comparisons but have not considered the specific context of shared mobility and decision-making at the level of purchasing and operating the vehicle fleet itself. This study will therefore contribute to the theoretical development of decision-making frameworks in transport by extending the application of the AHP method to a multivariate assessment model dedicated to sustainable fleet management. It also represents a fresh approach presenting a synthetic comparative analysis of several drivetrain types in existing car-sharing fleets in Central and Eastern Europe, thus making a significant contribution to the scientific literature by combining research on issues related to sustainable mobility, car-sharing fleet management, and environmental impact assessment.

2. The City’s Transport System, Car-Sharing Research to Date and Multi-Criteria Assessment of the Interconnection of Issues

The dynamic growth of Polish cities and significant demographic and spatial changes are contributing to a significant increase in the transportation needs of their residents, necessitating modifications and adaptations to urban transportation systems. More and more people live and work in Polish cities [1]. Until recently, some experts believed the importance of transportation in modern cities was beginning to decline. It was assumed that with the development of communication technologies and the growing popularity of remote work, the need for travel would diminish. However, such a trend has so far been difficult to observe in Polish cities.

More people are commuting to work from suburban areas, but migration is also increasingly moving in the opposite direction. The location of many commercial, industrial, and warehouse facilities on the outskirts of large cities means that many workers commute from the city/central area. The phenomenon of suburbanization has led to a situation in which the distances between places of residence, work, and meeting other basic needs have increased significantly. Furthermore, with economic development and increasing social affluence [23], the range of activities undertaken by residents has also expanded. This also generates additional needs related to moving around in urbanized spaces, creating new communication and transportation challenges. In this situation, local transportation systems, whose development was significantly limited until the end of the 20th century due to a lack of financial resources, could not, and still cannot, allow residents to effectively meet their transportation needs.

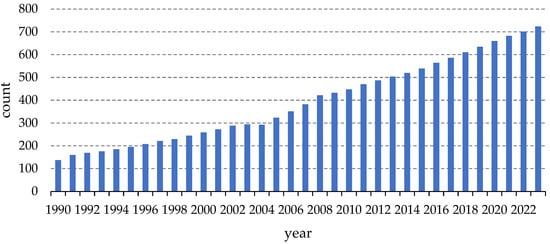

Additionally, this situation coincides with the dynamic growth of the car park size (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of registered passenger cars per 1000 population in Poland, (pcs.) [24].

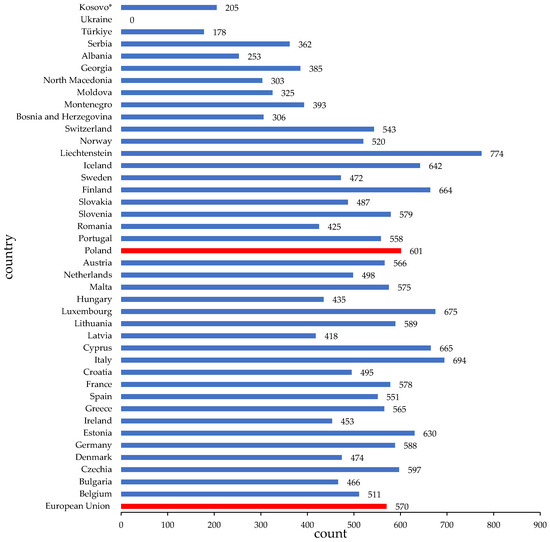

In the 21st century, a car ceased to be a luxury good and became available to every average family [25]. Currently, Poland is one of the most motorized countries in the European Union—in 2023, there were as many as 601 cars per 1000 inhabitants, while the EU average was only 570 (Figure 2) [2].

Figure 2.

Number of passenger cars per 1000 inhabitants in the European Union in 2023 [2]. Note: Ukraine: data not available. (*) This designation is without prejudice to positions on status and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

The statistics for Polish cities are even more alarming; for example, in Warsaw, there are over 815 cars per 1000 inhabitants [24] (Table 1). Considering the number of city inhabitants, it can be stated that in Warsaw or Katowice there is on average almost one passenger car per resident.

Table 1.

Motorization rate in the largest Polish cities (number of cars/1000 people).

Due to the above, the reorganization of urban transport has become a challenge in Polish cities and their transport systems. Declining population density in central areas and increasing population dispersion in the peripheries are making the existing public transport system increasingly ineffective, and accessibility is systematically declining. The specific nature of Polish suburbanization (chaotic, uncontrolled, and abrupt) means that new developments are most often located in areas without access to public transport.

In this situation, the best solution, considering the balance of transport systems and vehicle users’ preferences for using passenger cars, is the large-scale implementation of car-sharing services.

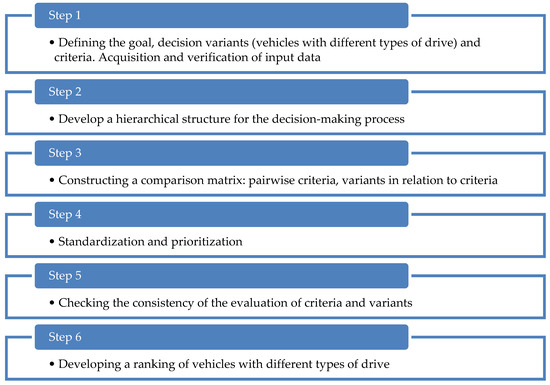

However, the car-sharing industry in Poland currently faces numerous challenges that impact the service’s costs and availability, including high claims rates for drivers, primarily those aged 18–21, inflation, and, depending on the vehicle’s powertrain type, varying fuel prices, insurance policy rates, and vehicle prices [26]. In this paper, taking into account a number of technical, economic and environmental factors characterizing vehicles with different types of drives, a tool supporting the formation of a fleet in carsharing systems was proposed, which enables the selection of the optimal vehicle in given operational and market conditions. To this end, using a multi-criteria evaluation method, the AHP method, a six-step algorithm was developed for selecting vehicles meeting specific criteria: ecological, economic, and technical (Figure 3). This tool can be used by both current and future car sharing service providers to optimize and modernize their fleets, including selecting service providers whose fleets meet their expectations in terms of upcoming environmental challenges and opportunities.

Figure 3.

Procedures for assessing vehicles used in car sharing systems.

The proposed approach brings a new perspective to car-sharing, as previous research has focused primarily on the general mechanisms of vehicle sharing systems, omitting a detailed assessment of fleet structure, particularly in terms of the type of drive used. A systematic literature review conducted for this study indicates that existing research primarily focuses on:

- Origins and development of the car-sharing concept [27,28,29,30];

- Analysis of the functioning of the car sharing services market [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40];

- Business models used by car sharing system operators [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50];

- Characteristics of car-sharing users, including their behavior, preferences, and motivations [34,44,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64];

- Vehicle fleet management, including station location and car relocation [34,51,52,65,66,67,68,69,70,71];

- Issues related to electromobility in car sharing systems [35,36,66,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78];

- Factors supporting and barriers to the development of car-sharing services from the perspective of users and service providers [32,79,80,81,82,83,84].

Analyzing the literature, it was noticed, however, that there are tools that are available for the assessment and assessment of vehicles available in sharing cars, which include multi-criteria assessment methods, e.g., in [85], the comprehensive use of conventional and plug-in vehicles, and assigned integer programming methods for assessing the effects, emissions and use of vehicles in variable applications. Subsequently, ELECTRE III was released in [86], a set of measurable technical and accessible solutions that allow vehicle model selection from the operator’s perspective. Differently, ref. [87] presents an assessment from the point of view of users frequently using carsharing systems, which concerns operational and cost parameters.

Despite the growing number of studies using multi-criteria methods, there is no work that would indicate the optimal vehicle for carsharing systems based on a wide range of economic, technical and environmental factors, important from the point of view of both operators and users, for whom the environmental aspect plays an increasingly important role. Moreover, previous studies have included different vehicle models, making comparisons between analyses difficult. In this work, a uniform base model of the vehicle was adopted, which eliminates design differences and allows for an objective comparison of drive variants using a consistent set of criteria.

The process of making decisions regarding the fleet structure in carsharing systems is fundamentally different from decisions in traditional transport companies. Operators of shared mobility systems must take into account high demand variability, short vehicle rotation cycles, urban infrastructure constraints, and the pressure to reduce emissions in urban areas. The choice of drive technology directly affects operating costs, service availability, operational flexibility, environmental emissions, and requirements for charging or refueling infrastructure. The complexity of these dependencies means that the selection of a vehicle for a carsharing fleet requires the use of tools that integrate many contradictory criteria and enable transparent ranking of solutions. In this context, it is justified to use the AHP method. The multi-criteria decision support method AHP has been used in a number of studies on transport systems. In [88] it was used to indicate the optimal locations of carsharing stations, while in studies [52,89] it was used to assess the profitability of their construction and operation. T. Saaty [90] presented wide possibilities of using AHP in the analysis of transport projects, including the selection of optimal transport connections based on a hierarchy of criteria. H. Gercek et al. [91] used AHP to evaluate variants of expanding the railway network for Istanbul, demonstrating the high effectiveness of the method in solving multi-criteria transport problems. A similar approach was used in [92,93] to evaluate alternative variants of an integrated transport system for the Poznań agglomeration.

The AHP method is characterized by universality and a number of advantages important from the point of view of comparing the considered vehicle variants. The most important include the possibility of using both a small and a large number of decision-making variants, obtaining a clear final order with quantification of differences between variants, transparency of the process of building a preference model, low computational effort, high practical usefulness and a clear graphical presentation of results facilitating decision-making.

To sum up, the AHP method is an effective tool for multi-criteria assessment of transport systems, enabling solutions to be sorted according to their effectiveness based on a coherent set of criteria. For this reason, it is particularly well suited to the problem of analyzing the structure of a carsharing fleet, especially in the context of assessing drive technology. Previous research has treated vehicles only as means of transport, without providing precise recommendations regarding the optimal fleet configuration. The approach proposed in this paper fills this gap, enabling a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness and sustainability of vehicle sharing systems.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data for the Solution Method

Choosing a specific means of transport, such as a passenger car, is a classic multi-criteria evaluation problem in the area of transport and logistics services. It is also a common practical problem faced by fleet managers, including car sharing fleets. The identified goal of the AHP method is therefore the selection of efficient means of transport by car sharing operators planning to expand their fleet or replace existing vehicles.

The passenger cars used in this research were manufactured in 2024 and belong to market segment C (compact car segment).

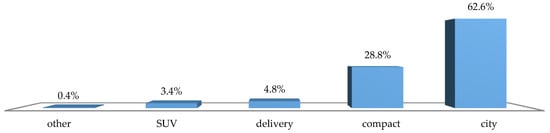

The authors identified the vehicles for the study based on secondary research conducted in 2024 among a group of car sharing operators operating in Poland. Based on this research, they found that city cars (segments A and B) and compact cars (segment C) dominate car sharing services in Poland, which together account for 91.4% of the market (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Vehicle fleet in car-sharing systems in Poland.

The analyzed vehicles have the same or comparable total power, the same body style, front-wheel drive, and automatic transmission, but differ in their power sources and drivetrains. However, all are the same vehicle model from a leading manufacturer. The comparative analysis included five vehicles, which are variants in the AHP method:

- Variant 1—car with a spark ignition engine (SI) (a1);

- Variant 2—car with a compression ignition engine (CI) (a2);

- Variant 3—with a hybrid drive (MHEV-Mild Hybrid Electric Vehicle) (a3);

- Variant 4—with a plug-in hybrid drive (PHEV-Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle) (a4);

- Variant 5—car with an electric motor (BEV-Battery Electric Vehicle) (a5).

The vehicles were assessed using typical criteria, including vehicle purchase cost, operating costs, purchase subsidies, number of refueling/charging stations, and time required to charge fuel/electricity. Their selection was based on the literature [86,94,95], supplemented with the author’s arbitrary recommendations (Table 2), taking into account the requirements of exhaustiveness of the assessment, consistency of the assessment with the decision-maker’s overarching goals, and non-redundancy of criteria [96,97,98]. Ultimately, a set of 10 criteria was proposed, which take into account all possible aspects of the problem under consideration; i.e., the environmental aspect was linked with economic and technical aspects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected partial environmental, economic and technical parameters for the tested vehicles [99,100,101,102,103,104].

A: in the analyzed case, five variants of vehicles operated in car sharing systems were taken into account:

The set G of criteria for assessing the distinguished variants of decision solutions was defined as a set with the following elements:

where:

- gk—evaluation criterion;

- k—evaluation criterion number.

3.2. Solving the Problem Using the AHP Method

The multi-criteria method for hierarchical analysis of decision problems, AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process), was proposed by T. Saaty in 1980 [105]. This method utilizes the principles of multi-attribute utility theory and allows for the decomposition of a complex decision problem, leading to the ordering of a finite set of decision alternatives [106]. It is based on three fundamental principles: the structure of the decision problem is presented as a hierarchy of objectives, criteria, subcriteria, and alternatives; preference modeling is performed by comparing parallel elements at each level of the hierarchy; and alternatives are ranked by synthesizing preference scores from all levels of the hierarchy [107,108,109].

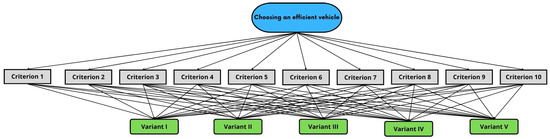

Hierarchical Structure of the Decision-Making Process

The AHP method is based on the construction of a hierarchical tree representing the structure of a decision problem. The hierarchical structure of the analyzed decision problem, developed for this research, is presented in Figure 5 and includes the goal of the decision-making process, the criteria, and the options being evaluated. The overarching goal of the decision-making process was assigned to Level 1. Level 2 contains the criteria evaluating the options, and Level 3 contains the options constituting solutions to the problem within the problem area.

Figure 5.

Hierarchical structure for the problem being solved.

Next, a pairwise comparative analysis was performed for each level. Individual groups of criteria were compared pairwise. The criteria within a given group were also compared separately. In the final step, the solution options within the problem area were compared pairwise, based on each criterion individually.

Stage 2 involved determining the decision-makers’ subjective preferences and expressing them in a manner characteristic of the AHP method. At this stage, relative importance ratings were defined at each level of the hierarchy using the standard AHP rating scale of 1–9 points, for pairs of criteria and decision options, respectively.

A score of 1 was therefore assigned to equivalent elements, characterized by equal importance. An extreme value of −9 was assigned to elements that were extremely strongly preferred over the second element being compared. Intermediate values, however, reflect the proportional intensity of the relative advantage of one element over the other. All coefficients are compensatory in nature (so-called pairwise consistency), meaning that the rating value for the less important (less preferred) element in a given pair is the inverse of the value assigned to the more important (more preferred) element. As a result, if the weight assessment of the criterion no. k in relation to criterion number k′ amounted to ωk′k, in the case of assessment criteria k′ in relation to the criterion k, the assessment adopted the value 1/ωk′k, tj.

where ωk′k is the assessment of the advantage of the k-th criterion over k′-th is. Elements compared ‘diagonally’ were estimated at 1.

The comparison matrix was developed using the results of our own surveys conducted among managers of car-sharing companies in Poland and urban transport experts, who provided preferential information in the form of relative importance ratings for pairs of criteria and decision options.

The sample was selected purposefully—representatives of entities with experience in the organisation and development of shared mobility services and specialists involved in the planning and operation of transport systems in cities were invited to participate. Ultimately, representatives of six car-sharing operators and 87 experts took part in the survey.

The survey was prepared in electronic form and made available to respondents by e-mail. The survey was conducted between September 2024 and April 2025.

The results of the pairwise comparison of criteria are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Elements of the pairwise criteria comparison matrix (preferences, matrix Ω = [ωk′k]K×K).

After establishing the preference matrix, a normalisation process was carried out, which consisted of dividing each element of the matrix of criterion comparisons in pairs in individual columns by the sum of all coefficients in a given column. Then, the arithmetic mean of the elements determined in each row has an interpretation of the priority (weight) of a given criterion. Therefore, the elements of the Ω matrix were successively normalized according to formula:

The values obtained formed the basis for calculating the priorities (weights) of the decision-making criteria (column 11 in Table 4), in accordance with the formula:

Table 4.

Normalised matrix with priority (weight) assigned to each criterion.

The normalised matrix with designated priorities is presented in Table 4.

In the next step of the AHP algorithm, the consistency of individual evaluation matrices at all levels of the hierarchy was tested; i.e., the degree of logical and homogeneous preferential information provided by decision-makers was verified. For this purpose, the consistency coefficient CR (Consistency Rario) (9) was used, whose value should not be greater than 0.1. If the consistency index value were greater than 0.1, it would be necessary to verify the preferential information provided by the decision-makers, as it would be characterized by too much inconsistency or an error. In such a situation, the stage of constructing the matrix of pairwise comparisons of criteria would be returned.

Determining the consistency index required calculating the product of two matrices: a matrix containing pairwise comparisons of criteria Ω (Table 3) and the “priority” columns of the vector W (Table 4). Then the result of the product was divided by the priority for each criterion, and then the average of these values was determined, which allowed us to obtain the index λ (7) together with the RI index reading, determining the consistency index CR.

where:

ΩW = C = [ck]K×1

- K—number of compared criteria (or variants);

- CI—consistency index;

- RI—random index that would be obtained for K elements for which the comparison would be made completely randomly [105,110].

In the calculations, the number of compared criteria, K, was 10; therefore, the RI coefficient value was assumed to be 1.49. Coefficients λ and RI allowed for estimation of the cohesion index CR:

The calculations showed that the CR index value was less than 0.1, which allowed us to conclude that the decisions regarding the importance of the criteria were consistent. This allowed us to proceed to further calculations comparing the alternatives against the criteria, which were performed similarly to the comparison of the criteria themselves. The only difference was that each decision alternative was compared with each decision alternative for each criterion. The local priorities of the alternatives against each criterion allowed for the creation of a ranking. Each comparison matrix was also checked for consistency according to the procedure described above.

The calculations showed that the CR index value for each level of the hierarchy (Table 5) was less than 0.1; therefore, there was no need to verify the preferential information provided by the decision-makers (this indicates information consistency).

Table 5.

Results of the matrix consistency test for the analyzed variants according to the criteria.

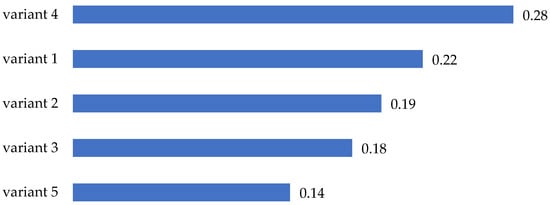

In the final stage of the AHP analysis, a ranking of the analyzed decision variants was determined (Figure 6). This required multiplying the matrix resulting from the local priorities obtained from comparing the variants against each criterion, i.e., P, and the global criteria weight vector W.

Figure 6.

Final ranking of variants.

The values of the global sub-criteria weight matrix W were calculated by multiplying the weights of the main criteria by the weights of their sub-criteria.

The result of the multiplication, in the form of a single-column matrix, contains the evaluation of the individual variants.

The variant with the highest value indicates the preferred solution to the decision problem.

4. Results

The AHP method enabled a comprehensive evaluation of five vehicle drivetrain options used in car-sharing systems. The analysis, based on expert comparison matrices, revealed a clear differentiation between the evaluated alternatives (Figure 6). The plug-in hybrid vehicle (PHEV, a4) received the highest global priority value, indicating its highest overall efficiency in the studied set. Subsequent places in the ranking were occupied by vehicles with a spark-ignition engine (SI, a1), a compression-ignition engine (CI, a2), a mild hybrid (MHEV, a3), and an electric vehicle (BEV, a5).

The resulting ranking structure reflects the relative influence of the adopted decision criteria. As presented in Table 4, the highest weights were assigned to economic criteria—in particular, the vehicle purchase cost (g1 ≈ 0.33) and the cost of driving 100 km (g2 ≈ 0.18)—which had the greatest impact on the final results. Among the environmental criteria, CO2 emissions were the most important, while technical factors such as range, charging time and the number of charging stations were of a complementary nature. The consistency index (CR < 0.1) confirmed the reliability of the comparison matrix and the internal consistency of the expert ratings (Table 5). The dominance of the PHEV variant (a4) stems from its favorable balance of economic, environmental, and operational aspects. As shown in Table 2, this variant combines low operating costs (PLN 8.62/100 km) and reduced CO2 emissions (26 g/km) with a long total range (3333 km) and dual-fuel capability (fuel and electricity), ensuring high operational flexibility in Poland’s infrastructure conditions. In contrast, the BEV variant (a5), despite having no local emissions, achieved the lowest score due to significant operational limitations—long charging time (330 min charging at an AC charging station), shorter range (416 km), and a limited number of charging stations (2101).

The internal combustion variants (ZI and ZS) achieved intermediate results. Their higher emissions are offset by low purchase costs, short refueling times, and full infrastructure availability, which remains a significant operational factor in the current market conditions.

The results confirm that the PHEV configuration currently represents the most rational solution for car-sharing fleets in Poland. Its quantitative advantage in economic and environmental dimensions indicates that plug-in hybrid systems may represent a transitional stage and a practically optimal solution between conventional and fully electric technologies.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In an era of increasing urbanization and growing demands for sustainable urban development, optimizing urban transport systems while taking into account environmental criteria is becoming a key challenge. Shared mobility, with car-sharing as one of its most dynamically developing forms, may become a key direction of transport development. In principle, a properly designed and managed vehicle fleet can contribute to reducing the number of individual vehicles in city centers. At the same time, it provides an environmental opportunity to reduce pollutant emissions. However, the effectiveness of such solutions depends largely on the proper selection of the type of drive, which constitutes a significant analytical and organizational challenge.

This article presents a methodology supporting the decision-making process in this area, based on the AHP method. The analysis included ten evaluation criteria, reflecting both environmental conditions and the needs of fleet operators and the expectations of vehicle users.

The research conducted allowed us to formulate the following conclusions:

- The obtained results confirm that the AHP method can be an effective tool for supporting the selection of the optimal drive type based on multiple criteria, enabling the integration of economic, ecological, and technical aspects into a single assessment model. The authors indicate that the method can also be useful in the analysis of other urban fleets, supporting sustainable mobility planning.

- The selection of the type of drive in car fleets, despite the growing interest in low- and zero-emission vehicles, still poses an environmental and operational challenge. According to the data presented in the market report [8], only about 2% of surveyed small and medium-sized enterprises use fully electric vehicles (5% among medium-sized companies), 3% use plug-in hybrid cars, and every tenth company has a classic hybrid. Combustion vehicles still dominate, appearing in almost all fleets. The results obtained in this study confirm this trend—combustion-powered vehicles ranked higher than BEVs in the AHP analysis, which indicates that in current market conditions their economic and operational advantage still outweighs environmental aspects. These data are consistent with other European studies [60,61,62], which indicate that infrastructural and economic barriers continue to hinder the development of electromobility in car-sharing.

- The analysis showed that the most environmentally and economically advantageous drive is PHEV. It combines low CO2 and PMx emissions with the lowest travel cost per 100 km, which is important considering the rising costs of fuel and vehicle servicing. Additionally, the PHEV drive is distinguished by the greatest operational flexibility—it allows both charging from the network and refueling, which reduces the risk of downtime and increases the operating range of the vehicle. Thanks to this, it can be effectively used in car-sharing systems where the availability of charging infrastructure is still limited. The results are consistent with the findings of Bardhi et al. [63], who pointed out that plug-in hybrid vehicles provide a balance between ecological efficiency and operational flexibility.

- Despite the dynamic development of electromobility, cars with combustion engines—both spark ignition (SI, a1) and diesel (ZS, a2)—remain the least environmentally beneficial drive variants and still pose a challenge in the context of fleet decarbonization.

Car sharing fits into the idea of the sharing economy, in which use is more important than ownership. The results of the study show that decisions regarding fleet electrification can actually support the implementation of sustainable urban transport goals. The increasing importance of ecology, the development of electromobility and the gradual reduction in private car traffic in city centers favor the popularization of vehicle sharing services. Thanks to the rapid renewal of fleets and operational flexibility, car-sharing can become an important element of the transformation towards low-emission transport. This is particularly important because passenger car fleets are among the market segments that are renewed the fastest—mainly for tax and cost reasons [111].

The study is based on specific assumptions and opinions of experts related to the Polish car-sharing market; therefore, the results obtained should be interpreted in this context. In the future, it will be worth verifying the possibility of applying the proposed approach in other cities and their vehicle fleets.

Certain limitations of the study should also be noted. The AHP method, although effective in multi-criteria assessment, relies on subjective expert assessments, which may influence the results. Therefore, for a comprehensive assessment, it is worth expanding the evaluation to include other decision-making techniques, such as TOPSIS or DEA. Furthermore, the analysis only included five drive variants and a limited set of criteria, so it does not fully reflect the complexity of the market. In further research, it is worth extending the analysis to include total cost of ownership (TCO) and life cycle analysis (LCA) indicators, as well as using other multi-criteria methods or dynamic models to obtain a broader decision-making perspective.

The authors also indicate further research directions that should focus on:

- -

- Adapting the proposed methodology to other geographical conditions in which car-sharing fleets have a similar scale and structure;

- -

- Extending the analyzes to the entire urban transport system, including public transport and taxis, taking into account the comparison of the drives used;

- -

- Developing a coherent set of criteria and preference models for assessing variants in the field of technical diagnostics and shared fleet management;

- -

- Introduction of an additional variable in the form of the TCO indicator, which allows for better consideration of economic aspects related to the use of vehicles;

- -

- Conducting long-term simulations of the profitability of using BEVs under various scenarios of energy prices and the development of charging infrastructure.

To sum up, the presented research does not cover the entire spectrum of challenges faced by car-sharing fleets on the way to sustainable urban transport, but it constitutes an important contribution to research on the transformation of urban mobility towards environmentally friendly solutions. The combination of a quantitative approach with decision support methods strengthens both the theoretical and practical foundations of shared fleet management in the context of sustainable development and energy transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; methodology, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; software, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; validation, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; formal analysis, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; investigation, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; resources, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; data curation, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; writing—review and editing, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; visualization, E.S.-M., W.L. and Z.Ł.; supervision, E.S.-M. and W.L.; project administration, E.S.-M. and W.L.; funding acquisition, Z.Ł. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by Institution Committee due to Legal Regulations (https://www.ncn.gov.pl/sites/default/files/pliki/regulaminy/2021_12_wytyczne_dla_wnioskodawcow_kwestie_etyczne_ang.pdf, accessed on 10 August 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- CleanCities. Available online: https://cleancitiescampaign.org/research-list/state-of-european-transport-in-cities/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment Report. 2023. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/document/download/2f6d95b0-7a76-4074-a080-341d417f34c1_en?filename=IMPACT%20ASSESSMENT%20REPORT_SWD_2023_421_part1_0.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- WHO. Ambient Air Pollution: A Global Assessment of Exposure and Burden of Disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511353 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Europe’s Air Quality Status 2022. Available online: https://www-eea-europa-eu.translate.goog/publications/status-of-air-quality-in-Europe-2022?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=pl&_x_tr_hl=pl (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- European Commission. Directive (EU) 2024/2881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2024 on Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europe. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202402881 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Electric Vehicles Promotion Foundation. 2024. Available online: https://fppe.pl/dyrektywa-aaqd-propozycja-rewizji/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Transport and Environment. Available online: https://www.transportenvironment.org/articles (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Mitropoulos, L.; Kortsari, A.; Ayfantopoulou, G. A systematic literature review of ride-sharing platforms, user factors and barriers. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopeć, K. Przekształcenia transportowe miast służące poprawie jakości życia. Pr. Kom. Geogr. Komun. PTG 2021, 22, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansubuga, B.; Kowalkowski, C. Carsharing: A systematic literature review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 55–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MarketResearch.biz. Available online: https://marketresearch.biz/about-us/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Rodrigue, J.P. The Geography of Transport Systems: 8.2–Urban Land Use and Transportation. 2024. Available online: https://transportgeography.org/contents/chapter8/urban-land-use-transportation/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Shaheen, S. Carsharing Trends and Research Highlights; Transportation Sustainability Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- PSPA. New Mobility Development Strategy in Poland Until 2030. 2023. Available online: https://psnm.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/PSPA_Strategia_Nowej_Mobilnosci_Raport_2023.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders. New Car CO2 Report; SMMT: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, A.; Constantine Samaras, C.; Hendrickson, C.T.; Matthews, C.S.; Wong-Parodi, G. Integrating public transportation and shared autonomous mobility for equitable transit coverage: A cost-efficiency analysis. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 14, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WysokieNapięcie.pl. 10 Pros and Cons of Car Sharing. How to Drive a Car for “Minutes”? 2023. Available online: https://wysokienapiecie.pl/7693-carharing_wynajem_auta_na_minuty_test_vozilla_traficar_panek_4mobility/ (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- BIOGAZ-TECHPL. What Are the Benefits of Car Sharing in Big Cities? 2023. Available online: https://biogaz-tech.pl/jakie-sa-korzysci-z-car-sharingu-w-duzych-miastach/#Ekonomiczne_korzysci_z_carsharingu (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/ (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Hui, Y.; Wang, W.; Ding, M.; Liu, Y. Behavior Patterns of Long-term Car-sharing Users in China. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 4662–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trading Economics. Available online: https://pl.tradingeconomics.com/poland/gdp-per-capita (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Central Statistical Office. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Komornicki, T. Changes in Poles’ Everyday Mobility Against the Backdrop of Motorization Development; No. 227; Geographical Works of the Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IBRM SAMAR. Available online: https://www.samar.pl/wiadomosci/carsharing-w-polsce-2024 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Shaheen, S.; Chan, N.; Micheaux, H. One-way carsharing’s evolution and operator perspectives from the Americas. Transportation 2015, 42, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Sperling, D.; Wagner, C. A Short History of Carsharing in the 90’s. J. World Transp. Policy Pract. 1999, 5, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, P.; Ryan, F.; Coughlan, M. Undertaking a literature review: A step-by-step approach. Br. J. Nurs. 2008, 17, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muheim, P.; Reinhardt, E. Car-Sharing: The Key to Combined Mobility Energy 2000; BFE Swiss Federal Office of Energy: Bern, Switzerland, 1998; pp. 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.d.M. To Use or Not Use Car Sharing Mobility in the Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic? Identifying Sharing Mobility Behaviour in Times of Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.-Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Tahara, K.; Chinen, K.; Endo, H. Exploring factors affecting car sharing use intention in the Southeast Asia region: A case study in Java, Indonesia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, F.; Perboli, G.; Rosano, M.; Vesco, A. Car-sharing services: An annotated review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, Y.; Ko, J. Factors underlying vehicle ownership reduction among carsharing users: A repeated cross-sectional analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 76, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, M.; D’Orso, G.; Caminiti, D. The environmental benefits of carsharing: The case study of Palermo. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 48, 2127–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, J. The evolution of cooperative electric carsharing in Germany and the role of intermediaries. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 37, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Cohen, A. Innovative Mobility: Carsharing Outlook; Carsharing Market Overview, Analysis and Trends. 2020. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/61q03282 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Tennøy, A.; Usterud Hanssen, J.; Visnes Øksenholt, K. Developing a tool for assessing park-and-ride facilities in a sustainable mobility perspective. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2020, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terama, E.; Peltomaa, J.; Rolim, C.; Baptista, P. The Contribution of Car Sharing to the Sustainable Mobility Transition. Transfers 2018, 8, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoń, K.; Kubik, A. Business Innovations in the New Mobility Market during the COVID-19 with the Possibility of Open Business Model Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, V.A.; Rooke, F.; Cocca, M.; Vassio, L.; Almeida, J.; Vieira, A.B. Characterizing client usage patterns and service demand for car-sharing systems. Inf. Syst. 2019, 98, 101448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, N.; Zhang, Y.; Mannering, F. Individuals’ willingness to rent their personal vehicle to others: An exploratory assess-ment of peer-to-peer carsharing. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Ostertag, F.; Lehr, A.; Büttgen, M.; Benoit, S. I like it, but I don’t use it: Impact of carsharing business models on usage intentions in the sharing economy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1404–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Ki, H.; Lee, S. Factors affecting carsharing program participants’ car ownership changes. Transp. Lett. 2019, 11, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meelen, T.; Frenken, K.; Hobrink, S. Weak spots for car-sharing in The Netherlands? The geography of socio-technical regimes and the adoption of niche innovations. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 52, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, K.; Boon, W.; Frenken, K.; Blomme, J.; van der Linden, D. Explaining carsharing supply across Western European cities. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, L. Reconstituting Automobility: The Influence of Non-Commercial Carsharing on the Meanings of Automobility and the Car. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourinejad, M.; Roorda, M. Carsharing operations policies: A comparison between one-way and two-way systems. Transportation 2015, 42, 97–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenbach, J.; Jeffrey, M.; Chicco, A.; Diana, M. Car Sharing in Europe: A Multidimensional Classification and Inventory, Deliverable D2.1. 2018. Available online: http://stars-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/STARS-D2.1.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Valor, C. Anticipated emotions and resistance to innovations: The case of p2p car sharing. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 37, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L. Intention of Chinese college students to use carsharing: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 75, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. An Evaluation Framework for the Planning of Electric Car-Sharing Systems: A Combination Model of AHP-CBA-VD. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Sheok, C. A Study on Optimizing Depot Location in Carsharing Considering the Neighborhood Environmental Factors. J. Korea Inst. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 16, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhrort, L.; Steiner, J.; Graff, A.; Hinkeldein, D.; Hoffmann, C. Carsharing with electric vehicles in the context of users’ mobility needs-Results from user-centred research from the BeMobility field trial (Berlin). Int. J. Automot. Technol. Manag. 2014, 14, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmöller, S.; Weikl, S.; Müller, J.; Bogenberger, K. Empirical analysis of free-floating carsharing usage: The Munich and Berlin case. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2015, 56, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namazu, M.; Mackenzie, D.; Zerriffi, H.; Dowlatabadi, H. Is carsharing for everyone? Understanding the diffusion of carsharing servces. Transp. Policy 2018, 63, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Guo, D.; Yuen, K.F.; Sun, Q.; Ren, F.; Xu, X.; Zhao, C. The influence of continuous improvement of public car-sharing platforms on passenger loyalty: A mediation and moderation analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagadic, M.; Verloes, A.; Louvet, N. Can carsharing services be profitable? A critical review of established and developing busi-ness models. Transp. Policy 2019, 77, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Gifford, K.; Anable, J.; Le Vine, S. Business-to-business carsharing: Evidence from Britain of factors associated with employer-based carsharing membership and its impacts. Transportation 2015, 42, 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoniti, E.; Kim, J.; Rasouli, S.; Timmermans, H.J. Intrapersonal heterogeneity in car-sharing decision-making processes by activity-travel contexts: A context-dependent latent class random utility–random regret model. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 15, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrone, A.P.; Hoening, V.M.; Jensen, A.F.; Mabit, S.E.; Rich, J. Understanding car sharing preferences and mode substitution patterns: A stated preference experiment. Transp. Policy 2020, 98, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Ciari, F.; Axhausen, K. Comparing car-sharing schemes in Switzerland: User groups and usage patterns. Transp. Res. Part A 2017, 97, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balac, M.; Becker, H.; Ciari, F.; Axhausen, K.W. Modeling competing free-floating carsharing operators–A case study for Zurich, Switzerland. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 98, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repoux, M.; Kaspi, M.; Boyacı, B.; Geroliminis, N. Dynamic prediction-based relocation policies in one-way station-based car-sharing systems with complete journey reservations. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 130, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moein, E.; Awasthi, A. Carsharing customer demand forecasting using causal, time series and neural network methods: A case study. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2020, 35, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kypriadis, D.; Pantziou, G.; Konstantopoulos, C.; Gavalas, D. Optimizing relocation cost in free-floating car-sharing systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 4017–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubik, A. Impact of the Use of Electric Scooters from Shared Mobility Systems on the Users. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Joint infrastructure planning and fleet management for one-way electric car sharing under time-varying uncertain demand. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 128, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chen, P.; Lin, H.; Xie, C.; Chen, X. Promoting carsharing attractiveness and efficiency: An exploratory analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 65, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiani, L.; Prencipe, L.P.; Ottomanelli, M. A static relocation strategy for electric car-sharing systems in a vehicle-to-grid framework. Transp. Lett. 2020, 13, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruglieri, M.; Colorni, A.; Luè, A. The relocation problem for the one-way electric vehicle sharing. Networks 2014, 64, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartenì, A.; Cascetta, E.; de Luca, S. A random utility model for park & carsharing services and the pure preference for electric vehicles. Transp. Policy 2016, 48, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deza, A.; Huang, K.; Metel, M.R. Charging station optimization for balanced electric car sharing. Discret. Appl. Math. 2020, 308, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firnkorn, J.; Müller, M. Free-floating electric car-sharing fleets in smart cities: The dawning of a post-private car era in urban environments? Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 45, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Shao, Z.; Song, H.; Wang, W. Charging and relocating optimization for electric vehicle car-sharing: Anevent-based strategy improvement approach. Energy 2020, 207, 118285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y. Electric vehicle car-sharing optimization relocation model combining user relocation and staff relocation. Transp. Lett. 2021, 13, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikl, S.; Bogenberger, K. A practice-ready relocation model for free-floating carsharing systems with electric vehicles–Mesoscopic approach and field trial results. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2015, 57, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, C.; Bruno, R.; Laarabi, M.H. Weak signals in the mobility landscape: Car sharing in ten European cities. EPJ Data Sci. 2019, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. MOMO Car-Sharing Project—Business Plan for Car-Sharing. 2017. Available online: https://trimis.ec.europa.eu/project/more-options-energy-efficient-mobility-through-car-sharing (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- European Environment Agency. Ensuring Quality of Life in Europe’s Cities and Towns. 2009. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/quality-of-life-in-Europes-cities-and-towns (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Hjorteset, M.A.; Böcker, L. Car sharing in Norwegian urban areas: Examining interest, intention and the decision to enrol. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 84, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugion, R.G.; Toni, M.; di Pietro, L.; Pasca, M.G.; Renzi, M.F. Understanding the antecedents of car sharing usage: An empirical study in Italy. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2019, 11, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.; Simkins, T. Consumers’ processing of mindful commercial car sharing. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquillat, A.; Zoepf, S. Deployment and utilization of plug-in electric vehicles in round-trip car-sharing systems. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2018, 12, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoń, K.; Kubik, A.; Chen, F. What Car for Car-Sharing? Conventional, Electric, Hybrid or Hydrogen Fleet? Analysis of the Vehicle Selection Criteria for Car-Sharing Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoń, K. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis during Selection of Vehicles for Car-Sharing Services—Regular Users’ Expectations. Energies 2022, 15, 7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Deng, H. Siting of Carsharing Stations Based on Spatial Multi-Criteria Evaluation: A Case Study of Shanghai EVCARD. Sustainability 2017, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Breuil, D.; Singh Chauhan, S.; Parent, M.; Reveillere, T. A Multicriteria Decision Making Approach for Carsharing Stations Selection. J. Decis. Syst. 2007, 16, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. Transport planning with multiple criteria: The Analytic hierarchy process. Applications and progress review. J. Adv. Transp. 1995, 29, 81–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gercek, H.; Karpak, B.; Kilincaslan, T. A Multiple Criteria Approach for the Evaluation of the Rail Transit Networks in Istambul. Transportation 2004, 31, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żak, J.; Fierek, S. Design and Evaluation of Alternative Solutions for Integrated Urban Transportation System. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Transport Research, Berkeley, CA, USA, 24–28 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Żak, J.; Fierek, S. Konstruowanie i Ocena Wielokryterialna Zintegrowanych Systemów Transportu Miejskiego. In Proceedings of the VI Konferencja Naukowo-Techniczna: Wspomaganie Decyzji w Projektowaniu i Zarządzaniu Transportem, Poznań, Poland, 23–25 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Turoń, K. Carsharing Vehicle Fleet Selection from the Frequent User’s Point of View. Energies 2022, 15, 6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoń, K. Selection of Car Models with a Classic and Alternative Drive to the Car-Sharing Services from the System’s Rare Users Perspective. Energies 2022, 15, 6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.; Greco, S.; Ehrgott, M. (Eds.) Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B. Decision Science or Decision-Aid Science? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1993, 66, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincke, P. Multicriteria Decision-Aid; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Autocentrum. Independent Automotive Portal. 2024. Available online: https://www.autocentrum.pl/dane-techniczne/peugeot/308/iii/hatchback-plug-in/silnik-hybrydowy-1.6-hybrid-180km-od-2021/ (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Car Labelling. Recherche Multicritères. 2024. Available online: https://carlabelling.ademe.fr/recherche?searchString=&co2=&brand=peugeot&model=308&category=&range=&carbu%5B%5D=EL&transmission=&price=0%2C500000&maxconso=&energy=0%2C7&RechercherL=Rechercher&offset=0&orderby[]=particules%20desc&searchString (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Chargemap. Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://chargemap.com/about/stats/poland (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Motonews.pl. 2024. Available online: https://www.motonews.pl/auta-nowe/auto-14867-peugeot-308.html (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- PEUGEOT. 2024. Available online: https://www.peugeot.pl/ (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Transport & Environment. CO2 and Emissions Performance of PHEV Vehicles. 2023. Available online: https://www.transportenvironment.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023_02_TE_PHEV_Testing_2022_TU_Graz_report_final.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet-Lagreze, E.; Siskos, J. Assessing a Set of Additive Utility Functions for Multicriteria Decision Making, the UTA Method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1982, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cascales, M.S.; Lamata, M.T. Solving a decision problem with linguistic information. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2007, 28, 2284–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. Axiomatic foundation of the analytic hierarchy process. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.; Ozdemir, M. Why the magic number seven plus or minus two. Math. Comput. Model. 2003, 38, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, G.; Mikulik, J.; Lewicki, W.; Niekurzak, M. Assessment of the Energy Efficiency of Individual Means of Transport in the Process of Optimizing Transport Environments in Urban Areas in Line with the Smart City Idea. Energies 2025, 18, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.