Abstract

Short food supply chains are an increasingly important topic within the academic community, as is research into the factors influencing consumers’ intention to buy at farmers’ markets. This study examines the influence of consumers’ product perception and product knowledge on purchase intention at farmers’ markets. Data were collected at farmers’ markets in Croatia. A total of 255 valid responses were analysed using exploratory factor analysis and hierarchical regression. Demographically, respondents were predominantly women aged 46–55 with higher education and middle-income levels (family annual income of EUR 20,000 to 40,000). Results indicate that both product perception and product knowledge significantly affect purchase intention at farmers’ markets. Consumers generally view farmers’ market products as superior in quality and value, and they place high trust in farmers’ expertise. The findings suggest that attributes such as freshness, safety, and authenticity, combined with product knowledge-sharing by farmers, strengthen consumer trust and increase their willingness to pay and to recommend these products to family and relatives.

1. Introduction

Food purchases at short food supply chains are increasing all around the world and are considered a more sustainable alternative to highly specialized, resource-intensive modern agri-food supply chains [1] (Giampietri et al. 2016). Markets that facilitate direct communication between producers and end consumers [2] (Bruch and Ernst, 2010) offer numerous advantages for both farmers and buyers of their products. Numerous studies have focused on the profile of consumers who purchase agricultural products directly from producers, highlighting key motivations such as the desire for higher-quality food, support for local farmers, and contribution to their economic sustainability [3,4] (Gumirakiza et al., 2014; Maples et al., 2013). Through this form of sales, producers have the opportunity to build stronger relationships of trust with consumers, avoid intermediary costs, achieve higher selling prices, and increase their income [5] (Pirog, 2004). On the other hand, consumers who buy directly from producers place high value on the firmness and texture of products, their freshness, taste, safety, and overall value [6] (Bond et al., 2006). These consumers also emphasize the importance of a diverse selection of high-quality and safe products, as well as support for local production, while factors such as convenience of purchase, product appearance, and price are less important to them compared to those who purchase through intermediaries. However, differences exist among consumers: individuals with lower incomes pay significantly more attention to product prices, whereas for higher-income consumers, this factor is less decisive. Bavorova et al. (2016) [7] found that consumers engaged in direct sales are particularly interested in knowing the origin and production methods of their food. Most respondents expressed greater trust in the quality and production processes of food purchased directly from farmers compared to other points of sale. Additionally, they are motivated by a desire to support local producers and prefer products that involve minimal transportation. Research on the behavior of organic food consumers [8] (Zamkova et al., 2023) indicates that individuals aged 26 to 35, predominantly women with higher education, are the most likely to purchase these products directly from producers. However, despite this trend, supermarkets and hypermarkets remain the most common places for purchasing organic agricultural products. This is largely attributed to the high level of consumer trust in certification authorities and in certified organic labels found on supermarket shelves [9] (Baydas et al., 2021). One of the key limitations of farmers’ markets is their operating hours, as some are open only for a few hours on specific days. This time constraint is a major reason why many consumers prefer supermarkets, particularly when market hours conflict with their work schedules. According to Stewart and Dong (2018) [10], the likelihood of purchasing food at farmers’ markets is positively correlated with the planned household spending on such products. While some authors argue that consumers are driven by political, environmental, or local-patriotic motives when buying directly from producers [1,11] (Giampietri et al., 2016; Vasquez et al., 2017), others suggest that personal concerns—such as health considerations or product pricing—play a more significant role [12] (Vasco et al., 2018). As public awareness grows regarding the importance of healthy nutrition and its impact on overall well-being, there is a noticeable increase in consumer interest in purchasing food from trusted and well-known producers [13] (April-Lalonde et al., 2020). Direct communication and direct purchase from local farmers can have multiple positive effects for consumers, such as a higher level of product quality assurance, obtaining additional information about the production method and products, and a sense of contributing to the development of the local economy [14] (Čehić et al. 2024).

Therefore, farmers’ markets should clearly emphasize the presence of local suppliers and their products and provide space for dedicated vendors who can explain in detail the origin and production of each item, thereby building trust and promoting the value of local food. The market is not only a place of commerce but also an important bridge between producers and consumers. The exchange of knowledge and experiences about products fosters trust and increases consumer awareness, while also helping producers better understand consumers’ nutritional needs. Such relationships of trust and familiarity can encourage purchase intentions and contribute to long-term, stable consumer purchasing behavior. It is thus crucial to understand consumers’ needs and preferences to enhance their willingness to buy [15] (Ou & Fang, 2018). Product knowledge represents a valuable resource for a specific region, and the amount of information available about a product can influence the purchasing behavior of individuals and groups, serving as a guide for informed purchasing decisions [16] (Cai, 2020).

In the past, many studies on farmers’ markets have investigated the frequency of farmers’ market shopping in relation to human values: attitudes towards the industrialized food market and attitudes towards the environment [17] (Cicia et al., 2021), knowledge of food safety and sociodemographic factors of consumers [18] (Monroe-Lord, 2020), and characteristics of attitudes and behaviors of consumers who shop at farmers’ markets [19] (Solanki, Inumula, 2021). However, few studies have specifically examined the characteristics of direct information about agriculture and food provided to consumers [20] (Ma & Chang, 2022), particularly in the context of preferences and product knowledge as motivations for shopping at farmers’ markets. To deepen our understanding of the role of farmers’ markets in the contemporary consumer environment, this study investigates how consumers’ perceptions of product quality and authenticity, along with the opportunity to obtain direct information and expertise from producers, influence their purchase intentions at these markets.

The aim of the paper is to determine the influence of product perception and product knowledge on the intention of purchasing agricultural and food products at farmers’ markets.

Considering the concept of a local farmers’ market and the existing level of customer knowledge about food and agricultural production, the results obtained should encourage retailers to gain a deeper understanding of their customers’ profiles, expectations, and motivations. This, in turn, allows retailers to adapt their offerings, communication, and service practices to enhance customer satisfaction, foster loyalty, and improve the overall quality of the shopping experience at the market.

2. Literature Review

Research on consumer behaviour, motivations, and perceptions at farmers’ markets has expanded significantly in recent years, consistently showing that purchasing decisions in these settings are shaped by multidimensional evaluations, contextual factors, and value-driven orientations. Across diverse methodological perspectives, the literature portrays farmers’ markets as complex retail environments where notions of quality, safety, authenticity, sustainability, and community interconnect to influence consumer intentions and actual buying behaviour.

2.1. Multidimensional Perceptions of Food Quality and Safety

A substantial body of research highlights that consumers at farmers’ markets interpret food quality as a multifaceted and context-dependent construct. Garner (2023) [21] explores consumer perceptions of food quality in the context of farmers’ markets, offering a conceptual framework that broadens the meaning of quality beyond conventional definitions. Through qualitative analysis, the study identifies eight dimensions that consumers commonly associate with quality: taste, freshness, seasonality, health benefits, method of production, rarity, aesthetics, and social proof. The findings highlight that consumers’ evaluations are highly contextual and multidimensional, suggesting that quality is not a fixed construct but one shaped by individual and cultural interpretations. This nuanced perspective emphasizes the complexity of consumer decision-making processes and highlights why farmers’ markets are often perceived as superior sources of food compared to conventional retail channels. Early consumer profiling by Wolf et al. (2005) [22] provides an early profile of farmers’ market consumers in the United States, focusing on perceived advantages of farmers’ market produce. Their survey results reveal that freshness, taste, and superior quality compared to supermarket alternatives are consistently cited as primary motivators for purchases. Additionally, consumers emphasize trust in the authenticity of products and the credibility of local producers. The study concludes that these perceptions foster loyalty, with many consumers reporting repeated visits due to positive experiences with product quality. Middleton and Smith (2011) [23] focus on the purchasing habits of senior shoppers at farmers’ markets. They find that older consumers perceive farmers’ markets as opportunities to access healthy and fresh food, but also as social environments that reduce isolation. While seniors generally spend modest amounts, their regular attendance indicates strong loyalty. The study suggests that designing age-friendly market spaces and services could expand this demographic engagement further.

While quality remains central, perceptions of safety exhibit more variability. Yu et al. (2017) [24] investigate U.S. consumers’ perceptions of food safety and food quality at farmers’ markets, using survey data to assess how these perceptions in-fluence purchasing decisions. Results reveal that while many participants, particularly younger demographics, perceive farmers’ market produce as safe, these perceptions are not the strongest predictors of actual purchasing behaviour. Instead, factors such as freshness, taste, and the desire to support local producers play more significant roles. The study points to a gap between perceived safety and actual microbial risks, emphasizing the need for food safety education to align consumer beliefs with scientific realities. Khouryieh et al. (2019) [25] specifically examine perceptions of fresh produce safety at farmers’ markets. Their study highlights consumers’ mixed attitudes, with some expressing strong confidence in the naturalness and safety of farmers’ market products, while others raise concerns about hygiene, handling, and lack of regulation. Findings indicate that while positive safety perceptions enhance trust and support purchase intentions, lingering doubts can act as barriers to expanding consumer bases. The research underscores the importance of implementing visible safety practices and communication strategies to strengthen trust and reassure consumers about product integrity.

2.2. Motivations, Values, and the Role of Authenticity

The literature consistently finds that both hedonic and utilitarian motivations underlie consumer preferences for farmers’ markets. Tey et al. (2017) [26] investigate the motivational underpinnings of consumers’ preference for farmers’ markets within the broader framework of sustainable consumption. Using quantitative analysis, the authors identify both hedonic (enjoyment of the market experience, social interaction) and utilitarian (freshness, safety, transparency of origin) motivations as coexisting predictors of purchase intention. Moreover, the perception of authenticity mediates the relationship between attitudes and intention, suggesting that markets must maintain visible quality standards and personal interactions to capitalize on these motivations. The study emphasizes the need for consumer segmentation (e.g., hedonic vs. utilitarian buyers) to better tailor offerings and communication strategies.

Studies focusing on local food values provide similar insights. Zepeda and Leviten-Reid (2004) [27] examine consumers’ views on local food and their reasons for engaging with direct marketing channels. Their findings suggest that freshness and taste are the leading motivators, followed by value-based orientations such as supporting the local economy, avoiding industrial processing, and seeking transparency. While respondents express strong attitudinal support for local food, the study reveals that practical limitations such as limited product range and seasonality push consumers toward hybrid purchasing patterns, combining farmers’ market shopping with supermarket use. This research provides early evidence that community identity and values form an integral part of the motivational set for farmers’ market consumers. Dodds et al. (2014) [28] assess the ethical dimensions of consumer choice at farmers’ markets in Toronto, combining health, environmental, and social considerations. Results confirm that higher product quality and support for the community are primary motivations, while pursuing a healthier diet and addressing environmental concerns also significantly influence purchase intention. Despite positive attitudes, barriers such as higher prices, restricted hours, and location constraints remain prominent. The authors conclude that increasing consumer spending at farmers’ markets requires both a reduction in transactional costs (e.g., flexible payment systems, improved accessibility) and stronger communication of value propositions (quality, community welfare) to justify perceived higher costs. Feagan and Morris (2009) [29] develop the idea of consumers’ “quest for embeddedness,” arguing that farmers’ markets function as socio-spatial arenas where market exchange is re-embedded in relationships of trust, reciprocity, and place. Drawing on qualitative evidence, they show that shoppers pursue goods whose value exceeds functional attributes, seeking moral proximity—knowing who produced the food, how, and where. This embeddedness reframes “quality” as a composite of process transparency, producer identity, and community benefit, which, in turn, underwrites willingness to purchase despite potential price or convenience trade-offs. The study helps explain why farmers’ markets can sustain loyalty and advocacy even when they cannot match supermarkets on assortment or hours. Archer et al. (2003) [30] explore latent consumer attitudes toward farmers’ markets in Northwest England, highlighting differences between regular market shoppers and those who seldom participate. Using attitudinal segmentation, the study identifies groups with varying levels of interest in freshness, price, and community support. While frequent attendees associate farmers’ markets with authenticity and superior quality, occasional consumers often cite inconvenience and limited product scope as deterrents. These findings underscore the role of demographic and psychographic pro-files in shaping market participation.

Relatedly, Benos et al. (2022) [31] link mindful consumption with short food supply chains (SFSCs), proposing that reflective, values-driven consumer orientations complement the structural characteristics of direct marketing channels. Using quantitative modelling, they find that consumers scoring higher on mindfulness measures report stronger pro-environmental motivations, reduced impulsivity, and greater attention to prove-nance, which translate into higher purchase intentions in SFSC contexts such as farmers’ markets. The paper suggests that markets can amplify this alignment through choice architecture (clear origin cues, minimal packaging), producer storytelling, and nudges that keep environmental and social impacts salient at the point of decision.

2.3. Purchase Intentions vs. Actual Purchasing: Operational and Behavioural Determinants

Numerous studies distinguish between stated purchase intentions and realized behaviour, emphasizing operational constraints. Tsai et al. (2019) [32] examine determinants of actual purchase behaviour, emphasizing the distinction between intention and realized buying. Using structural equation modelling, the study finds that subjective norms (social influence), perceived value, and satisfaction with previous experiences directly drive repeat purchases. Although environmental concerns and local loyalty positively correlate with purchase intention, their impact on actual purchasing is mediated through satisfaction and perceived convenience (e.g., location and market hours). These findings confirm the relevance of the theory of planned behaviour but highlight that operational factors play a decisive role in converting consumer values into real transactions.

Conner et al. (2010) [33] analyse consumer attitudes and behaviours toward locally grown foods and farmers’ markets, combining survey data on motivations, frequency of attendance, and spending patterns. Their findings show that freshness, taste, and support for local farmers are dominant drivers of consumer intention, while price accessibility and convenience of location or hours often act as barriers. Purchase intention is strongly associated with perceived quality and trust in direct exchange with producers; however, many consumers continue to conduct most of their grocery shopping in supermarkets due to wider product variety and greater convenience. The authors suggest that operational innovations such as extended hours and pre-order systems could help transform positive attitudes into higher actual purchases.

Stanton et al. (2012) [34] identify and profile so-called “locavores”—consumers highly committed to local food systems. Locavores are found to be more educated, health-conscious, and environmentally aware, often demonstrating strong purchase intentions that translate into actual buying behaviour. They value seasonality, authenticity, and sustainability, making them a crucial consumer segment for farmers’ markets. However, their relatively narrow demographic base highlights the challenge of expanding farmers’ market appeal beyond this niche group.

Behavioural and operational insights further clarify this gap. Rigotti et al. (2023) [35] use transaction-level data to test interventions aimed at increasing customer purchases, demonstrating that small, data-informed tweaks such as stall placement, cross vendor bundling, and targeted loyalty prompts produce measurable gains in basket size and conversion. Evidence suggests that information frictions (unclear prices, inconsistent formats) suppress spending, while standardized price displays, digital payments, and recipe bundles raise throughput and average transaction value. The study advances a behavioural operations perspective: by tightening the link between shoppers’ prosocial motives and low-friction purchasing, markets can unlock latent demand without compromising their relational character. Murphy (2011) [36] conceptualizes farmers’ markets as retail servicescapes, emphasizing how spatial design, vendor mix, signage, and interactional scripts shape the shopper experience and, ultimately, spending. Rather than merely transactional venues, markets operate as experiential retail environments in which authenticity and face-to-face exchange substitute for conventional guarantees (branding, packaging). The paper argues that queue management, payment options, and layout legibility (clear aisles, wayfinding, clustering by product categories) reduce friction costs and extend dwell time, thereby improving conversion from browsing to purchase. By framing farmers’ markets within retail and place-making theory, the study explains how embeddedness is operationalized through concrete design and managerial choices.

2.4. Education, Knowledge, and Trust-Building Mechanisms

Several studies highlight the role of knowledge-building and educational activities in strengthening trust and shaping intentions. Ma and Chang (2022) [20] explore the impact of food and agricultural education at Taiwanese farmers’ markets on purchase intention. Structural equation modelling applied to 351 survey responses shows that product knowledge and perceived green value significantly increase purchase intentions, while trust strengthens the link between knowledge and intention. Furthermore, local attachment combined with trust further enhances this relationship, suggesting that farmers’ markets serve not only as retail venues but also as educational platforms that raise consumer awareness. The study highlights that knowledge-building activities such as storytelling, tastings, and demonstrations are effective tools for encouraging purchasing behaviour.

Bavorova et al. (2016) [7] investigate consumer profiles of those who buy from farmers’ markets and farm shops in Germany. Their analysis reveals that higher-income, better-educated, and urban consumers are more likely to frequent these outlets. However, product preferences also vary: families with young children often prioritize safety and health, while older consumers tend to value tradition and trust in producers. The study emphasizes that farmers’ markets are not homogeneous spaces but attract different social groups with diverse motivations and constraints.

Lyon et al. (2009) [37] extend this line of inquiry by exploring the shopping experiences of consumers at farmers’ markets. Their research indicates that consumers perceive farmers’ markets as distinct retail environments where freshness and quality are guaranteed through direct producer–consumer interactions. Shoppers value transparency and the ability to inquire about production methods, which reinforce confidence in quality claims. However, the study also reveals that while quality is a central attraction, market limitations such as seasonality and availability sometimes prevent farmers’ markets from fully meeting consumers’ grocery needs.

2.5. Socio-Demographic Profiles and Participation Patterns

The literature demonstrates notable demographic patterns among farmers’ market attendees. Gumirakiza et al. (2014) [3] study attendance patterns at U.S. farmers’ markets and the reasons underlying consumer participation. Their findings suggest that women, middle-aged individuals, and households with higher education levels are overrepresented among attendees. Motivations range from freshness and taste to supporting local farmers, but demographics strongly influence frequency and spending. For example, higher-income groups tend to spend more per visit, while younger attendees are often more sporadic in their purchasing. This highlights the importance of targeted marketing strategies tailored to specific demographic segments. A recent and highly relevant addition to this body of work is the systematic review conducted by Maró et al. (2023) [38], who synthesize survey-based empirical studies to identify recurring consumer profiles at farmers’ markets internationally. Their review highlights several consistent patterns: consumers tend to be older, more educated, more health-conscious, and more environmentally oriented than the general population. Importantly, the review also notes significant heterogeneity between countries, with cultural, economic, and policy factors shaping who participates in farmers’ markets and why. This synthesis strengthens the empirical foundation for demographic segmentation strategies and confirms that farmers’ markets attract consumers who combine quality-driven and value-based motivations. Witzling et al. (2025) [39] investigate the characteristics, behaviours, and motivations of farmers’ market attendees in the United States using a nearly nationally representative survey. The research focused on five key areas: the frequency and seasonality of farmers’ market attendance, shopping behaviours and preferences, non-shopping activities and perceived impacts of attendance, motivations and challenges associated with market participation, and differences in demographic and life-style characteristics between attendees and non-attendees. Among the 5141 respondents, over 80% reported attending a farmers’ market at least once per year, highlighting widespread, albeit often infrequent, engagement with these markets. Key findings include that most attendees value farmers’ markets for fresh, high-quality food, and for supporting local farmers. Common challenges include forgetting about the markets, high prices, and convenience-related issues. Attendees also reported non-shopping activities such as socializing and learning, suggesting the role of farmers’ markets as community spaces. Demographic analyses showed that attendees were more likely to be female, older, white, and from higher-income households, though at-tendance spanned diverse groups. Another recent contribution is provided by Bavorova et al. (2025) [40], who investigate the factors shaping purchase intentions at farmers’ markets among urban consumers in Moldova. Using the theory of planned behaviour, the study demonstrates that attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control significantly influence the intention to buy from farmers’ markets. The typical customer profile emerging from their findings is a middle-aged, educated consumer with low to medium household income. Key determinants that support market participation include encouragement from friends and family, trust in vendors, and personal preferences. The authors also highlight that consumer intentions are affected by shifting purchasing habits in Moldova, where supermarkets and online retail increasingly attract younger consumers. Their insights offer an important contribution to understanding how changing retail landscapes and behavioural drivers shape farmers’ market engagement in an Eastern European context.

However, several studies identify constraints for marginalized groups. Onianwa et al. (2006) [41] analyse consumer characteristics at Alabama farmers’ markets using on-site survey data. Their findings confirm that white, middle-class, and middle-aged consumers dominate attendance, with younger and lower-income groups less represented. Although respondents across income levels express appreciation for freshness and local support, price sensitivity limits participation among economically constrained consumers. The authors conclude that while farmers’ markets are valued for their community role, they may inadvertently exclude some social groups, raising questions about equity and accessibility. Rice (2015) [42] examines privilege and exclusion at farmers’ markets, providing critical insights into how these venues may reinforce socio-economic divides. Survey results suggest that farmers’ markets often cater disproportionately to wealthier and predominantly white consumers, creating barriers for marginalized groups. The study emphasizes that while farmers’ markets promote values of sustainability and community, they may simultaneously reproduce patterns of exclusion. Addressing these disparities requires policies aimed at equitable access, such as subsidies, inclusive out-reach, and culturally diverse product offerings.

2.6. Sustainability Orientations, Localism, and Food System Resilience

Sustainability-related perceptions play a significant but often indirect role in purchasing. Van Bussel et al. (2022) [43] provide a systematic review of consumer perceptions of food-related sustainability, distilling evidence that most consumers endorse sustainability in principle but face intention–behaviour gaps driven by price, convenience, and information overload. The review highlights that credible attributes (e.g., low food miles, eco-friendly practices) require credible, low-friction signaling at the point of sale to influence actual purchasing. In the context of farmers’ markets, the authors’ synthesis implies that visible cues of local origin, simple sustainability labels, and direct producer communication are likely to be especially effective at translating pro-sustainability attitudes into repeat purchases, because the short, relational chain reduces skepticism and search costs. González-Azcárate et al. (2021) [44] examine why buying directly from producers is valued, identifying a bundle of perceived benefits—freshness, fairness, transparency, and relational trust that cohere into a distinct value proposition relative to long chains. Survey evidence indicates that consumers perceive direct purchase as supporting rural livelihoods and fairer price distribution, while enabling traceability that reduces information asymmetry. These drivers positively affect both attitudes and purchase intentions, especially among consumers with stronger local attachment and sustainability orientations. The authors argue that policy and managerial efforts should safeguard these relational qualities (e.g., stable vendor presence, certification of origin) to preserve competitive differentiation.

Beyond individual motivations, farmers’ markets contribute to system-wide resilience. Lucas et al. (2024) [45] consider farmers’ markets as resilience infrastructures within food systems, synthesizing cross-national cases from members of the World Farmers’ Market Coalition. They argue that markets enhance resilience via redundancy (multiple producers), modularity (localized nodes), transparency (short chains), and civic engagement, features that sustain access to food during shocks such as COVID-19. The study documents adaptive capacities (e.g., rapid adoption of pre-order/pick-up, reconfigured layouts) and transformative roles (community organizing, policy visibility), positioning farmers’ markets as more than retail outlets: they are institutional actors capable of stabilizing supply, maintaining quality, and preserving consumer trust under stress—factors that ultimately protect purchase confidence and continuity.

2.7. Operational Factors, Market Design, and Consumer Experience

Operational and infrastructural dimensions strongly shape consumer satisfaction and loyalty. Hassanein et al. (2025) [46] test a service quality sustainability model in Indian farmers’ markets (Maharashtra) using structural equation modelling on 235 consumers. All examined dimensions—convenience, variety, quality, price, health and hygiene, and service conditions—exert significant positive effects on customer satisfaction, with convenience and service conditions showing the greatest magnitudes; satisfaction, in turn, predicts loyalty. Beyond operational levers, the authors frame these dimensions as sustainability enablers (e.g., reliable hygiene practices for public health; convenience that normalizes low-impact local shopping), implying that improving basic market operations can simultaneously advance social, economic, and environmental goals while converting favorable perceptions into repeat purchasing. Infrastructure-related studies, such as Crawford et al. (2018) [47], situate farmers’ markets within urban planning and public health objectives, showing that markets are perceived as nodes for fresh food access and support for local producers. Survey and qualitative insights indicate that proximity to residential areas, transport connectivity, and amenity co-location (parks, community facilities) enhance visit frequency and perceived neighborhood livability. Consumers valorise opportunities for producer interaction and food education, yet note that limited hours and weather exposure constrain routine shopping. The findings suggest that municipal planning (permitting, infrastructural support, stable locations) can translate pro-local attitudes into regular purchasing behaviour.

Similarly, Alonso and O’Neill (2011) [48] compare visitor needs and wants at two Alabama markets—one rural and nascent, one urban and established—finding consistent shopper priorities for greater product variety, extended seasons, and more vendors. Markets also function as community gathering spaces, with social interaction and opportunities to “meet the farmer” ranking highly alongside product attributes. Despite context differences, both sites reveal operational levers for increasing purchase: reliable schedules, expanded assortment, and better amenities (seating, shade, restrooms). The study concludes that iterative visitor feedback loops should guide retail decisions to sustain relevance and grow market share. Berg and Preston (2017) [49] estimate willingness to pay (WTP) at the Otago Farmers Market, revealing significant WTP premiums for local provenance and producer-direct verification. Transaction and travel behaviour data indicate that access factors (parking convenience, market congestion, travel time) materially affect realized spending, even among consumers with high stated WTP. The authors argue that capturing value-based demand requires operational alignment of streamlined entry/exit, adequate parking, and predictable stall locations so that the price value of trade-off remains favorable at the moment of purchase. Their evidence links transport/parking management to basket size and repeat visitation. Adanacıoğlu (2021) [50] analyses determinants of purchase behaviour in farmers’ markets, finding that freshness, taste, and trust in producers are the strongest positive predictors, while price sensitivity and availability constraints dampen expenditure. Demographic factors (education, income) and visit frequency shape both average spend and product mix, and satisfaction mediates the relationship between perceived quality and repeat purchase. The study underscores that market managers can leverage assortment breadth, hygiene visibility, and consistent vendor presence to stabilize expectations and convert occasional visitors into loyal shoppers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Context of Data Collection

Field research was conducted on a sample of farmers’ market visitors at the locations of Poreč and Vrsar, in Istria County, Croatia, during the period from June to September 2024. This period was selected for field data collection due to the greater availability of fresh fruits and vegetables at farmers’ markets. The City of Poreč and the Municipality of Vrsar are situated on the west coast of the Istrian Peninsula and represent a convenient location for organizing farmers’ markets, given their proximity to rural areas where farmers are located and the presence of a large consumer base in urban centers. In addition, this location is representative of the Croatian coastal area because the population increases significantly during the summer months due to the large number of tourists who temporarily become part of the local community. For example, in the City of Poreč and the Municipality of Vrsar, the number of tourists during the summer is almost three times higher than the number of residents. A similar situation occurs along other parts of the Croatian coast (Službeni Glasnik Grada Poreča, 21/2024) [51].

The farmers’ markets where the research was conducted are organized as an activity of the Association of Producers from the Istria County (“Istarska web tržnica”), aimed at promoting direct sales. The farmers’ markets are held once a week in the afternoon, bringing together approximately ten to fifteen local producers offering a variety of goods, including fresh fruits and vegetables, olive oil, honey, processed foods, aromatic herbs, cured meats, and more. The farmers’ market is frequented by a large number of local customers.

3.2. Data Collection and Questionnaire

During the data collection process, researchers informed farmers’ market visitors about the purpose of the study, ensured their anonymity, and obtained their consent to participate. Respondents were then provided with either a paper questionnaire or a sheet containing a QR code, depending on their preference. This flexible approach contributed to a higher response rate and encouraged participation in the research [52] (Olson and Ganshert, 2025). Respondents who received a paper questionnaire completed it on-site, while those who opted for the QR code accessed the online version at a time that was most convenient for them. The online version of the questionnaire was created in Microsoft Forms. The questionnaire comprised several sections, including questions on customers’ perceptions of the characteristics of products purchased at the farmers’ market, farmers’ knowledge about the products, future purchase intentions, and the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

The scale was adapted from previous studies and modified for the purposes of this research (Table 1). All items were measured using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Product perception was measured with six items, product knowledge was measured on three items and purchase intention on three items.

Table 1.

Items used for measuring factors.

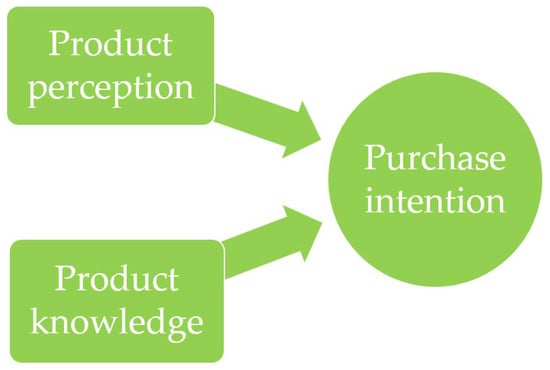

The proposed scale items were developed as the basis for analyzing the relationships among Product Perception (PP), Product Knowledge (PK), and Purchase Intention (PI), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The proposed model scheme. Source: Authors.

The target sample size was 200 or more to ensure the planned statistical analysis could be appropriately conducted (Hair et al. 2009) [53]. During the data collection process, 255 valid questionnaires were obtained, including 97 completed on-site and 158 completed electronically.

3.3. Data Analysis

The data were first entered into an Excel database and subsequently transferred to SPSS version 21 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) for further analysis. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample were described using percentages. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation was conducted to identify the underlying factors. Factors with eigenvalues of 1.00 or higher were retained for further analysis. Varimax rotation was employed to maximize the dispersion of factor loadings by increasing the number of high and low coefficients, thereby facilitating the identification of homogeneous groups of variables [54] (Richman, 1986). Internal reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (Ursachi et al. 2015) [55], and factor scores were computed as the mean of the items for each respondent. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from a minimum acceptable value of 0.70 (or 0.60 for exploratory research) to the recommended range of 0.80–0.90 (Hair et al., 2017 [56]). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using six items to measure Product Perception (PP), three items to measure Product Knowledge (PK), and three items to measure Purchase Intention (PI). The application of EFA is a commonly used analytical approach in marketing research to assess scale reliability.

The identified factors through EFA served as input variables for testing the proposed model. Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted, with purchase intention as the dependent variable, and product perception and product knowledge as the independent variables. Multicollinearity among the variables was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF). The data were analysed using the Statistical Software Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Results and Discussion

A total of 255 validly completed questionnaires were collected. Nearly three-quarters of the respondents are women, predominantly within the 46 to 55 age group. The majority hold a university degree and report an annual family income ranging from €20,001 to €40,000. This demographic profile aligns with findings from previous research by Ma and Chang (2022) [20], which identified a similar composition among farmers’ market visitors. Gumirakiza et al. (2014) [3] and Bavorova et al. (2016) [7] found that regular visitors to these markets are generally more educated, have higher incomes, and hold more positive attitudes towards sustainability and healthy eating (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted to identify the underlying dimensions of consumers’ perceptions of products, their perceptions of farmers’ product knowledge, and their future purchase intentions toward farmers’ markets. The identified factors are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of explanatory factor analysis.

The KMO of the data was 0.869, and Bartlett’s test was significant (0.000), which means that the data set was suitable for factors analysis.

All three factors account for 69.69% of the cumulative variance, with factor loadings exceeding 0.6 for all items. The values of Cronbach’s α for the measurement scales ranged from 0.859 (Products Perception scale) to 0.898 (Purchase intention scale). The identified unidimensional factors namely were called (1) Products perception, (2) Products knowledge, and (3) Purchase intention.

Consumers’ perceptions of farmers’ market products range from agreement to a slightly neutral stance. Most participants strongly agree with statement (PP1) Products on farmers’ market is superior (M = 4.56). The second most valued item is (PP3): ‘Products at the farmers’ market are of better quality’ (M = 4.48). This confirms the results of previous studies, which found that consumers most appreciate the quality of products sold at farmers’ markets [22,30] (Archer et al. (2003); McGarry et al. (2005)).

The statement (PP5) Products from farmers’ markets are less likely to cause diseases (M = 3.75) evokes a somewhat more neutral agreement.

Statement (PK1) Farmers who are familiar with their own agricultural products are trustworthy for their promotion of the knowledge of agricultural products in the food and agricultural education (M = 4.29) is the most valued statement from the Products knowledge scale. Also, the other two statements from this scale have a similar level of agreement. Similar consumer evaluations regarding product knowledge have also been reported in previous research (Ma and Chang, 2022) [20]. The Purchase Intention scale also showed a relatively high level of agreement among respondents, while some respondents are more likely to recommended farmers’ markets.

Table 4 presents the results of the hierarchical regression analysis. This analysis was applied to explore the relationship between consumers’ perceptions of farmers’ market products, product knowledge, and purchase intention.

Table 4.

Results of hierarchical regression analysis.

The proposed model had a significant F-test, indicating that product perception and product knowledge have a significant influence on customers’ purchase intention. The relatively low R-squared and adjusted R-squared values in the model suggest somewhat limited representativeness of the independent variables. This means that the proportion of variance in customers’ purchase intention explained by Product perceptions and Product knowledge is 26%. The variance inflation factor is 1.509, which is below 3.00 and, thus, below the threshold of 10 (Hair et al. 2009) [53].

When considering consumer behavior, perception as a psychological factor plays an important role, as it enables consumers to select, organize, and interpret information that serves as input in their purchase decision-making process (Wee et al. 2014) [57]. In this context, consumers’ product perception refers to the attributes of the product as perceived by consumers. In general, consumers perceived products sold at markets as fresher, healthier, and of higher quality compared to those available at other retail outlets, including supermarkets, a finding confirmed by this study.

Consumers’ product perception is often analyzed as an independent variable in studies examining the purchase intention process (Wang et al., 2023) [58]. However, in recent research, including the present study, it is also examined as having a direct impact on purchase intention. This is consistent with previous findings, which confirm the positive and significant influence of product perception on purchase intention [7,24,25,28,33,39,44] (Bavorova et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2017; Khouryieh et al., 2019; Dodds et al., 2014; Conner et al., 2010; Witzling et al., 2025; González-Azcárate et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the concept of product knowledge also confirms a positive and significant impact on purchase intention. Similarly, recent research also finds strong and positive relationships of product knowledge on purchase intention (Ma and Chang, 2022) [23]. In other words, providing customers with more information during the purchasing process increases the likelihood that they will not only make a purchase but also become repeat buyers. This is particularly relevant in direct sales contexts such as farmers’ markets, where interaction and personal contact between producers and consumers play a central role. Producers at farmers’ markets play an important role in sharing information and knowledge about how their products are made. By communicating directly with consumers, they can promote more environmentally friendly partnerships. This is supported by the advantages of direct selling, such as transparency, trust, and greater awareness of sustainable production methods.

It is important to highlight the limitations of the conducted study and their possible implications for the obtained results. The sample location reflects a specific context that includes both local residents and tourists visiting farmers’ markets during the summer months. Consequently, it can be concluded that the results may differ in other settings or seasons.

5. Conclusions

The aim of the study was to determine the influence of product perception and product knowledge on the intention to purchase agricultural and food products at farmers’ markets, based on an analysis of 255 valid questionnaires. The results show that farmers’ market consumers are women with higher education and middle incomes. Consumers’ perceptions of product quality and their knowledge about products positively influence their intention to purchase at farmers’ markets. The findings indicate that consumers strongly agree that farmers’ market products are superior and of higher quality, trust knowledgeable farmers, and report generally high purchase intentions.

The study provides practical implications for farmers in developing their marketing and communication strategies, emphasising the importance of clearly communicating intrinsic attributes such as higher quality, healthiness, nutritional value, and overall quality, as these are the main drivers of purchase decisions at farmers’ markets. When farmers provide information about products, production methods, and origin, they can convert their product knowledge into consumer trust and increase purchase intention. Additionally, by addressing safety information, proper product handling, low-chemical production practices, and certification, farmers can reassure consumers who consider both food safety and quality. Farmers’ market managers should focus on clearly highlighting the superior quality, freshness, and health benefits of products, as these attributes strongly influence purchase intention. Creating opportunities for farmers to share product knowledge through demonstrations or short educational events can further enhance customer trust and engagement. There are also practical implications for policymakers in supporting farmers’ markets by promoting programmes that improve transparency and consumer education about locally produced foods. Encouraging training or certification schemes can help farmers communicate product attributes more effectively, reinforcing trust and sustainability. Investments in local food infrastructure and market promotion can strengthen the role of farmers’ markets as platforms for healthy and environmentally responsible consumption.

The study also makes a scientific contribution by integrating product perception and product knowledge as predictors of purchase intention in a direct-sales context, addressing a gap in the literature where these constructs have often been examined separately. The findings strengthen the literature on farmers’ market consumers by providing empirical evidence from a different market, such as Croatia. The importance of this research for academia lies in deepening the understanding of the behavioural mechanisms shaping consumer responses in farmers’ markets and advancing theoretical frameworks within the fields of consumer behaviour, sustainable consumption, food marketing, and agricultural economics. By demonstrating how perceptions and knowledge interact to influence purchasing behaviour, the study offers a model applicable to similar contexts and provides a foundation for future research. In future, the sample could include underrepresented demographic segments (e.g., younger and lower- or higher-income consumers), as well as different regional markets (Continental vs. Adriatic) across Croatia. Future studies could also compare urban and rural markets and consumers’ intentions to buy at farmers’ markets. As already stated, the current model focuses only on perceptions and knowledge, while future research could examine food safety perceptions in greater depth, as well as location, product accessibility, and willingness to pay for local products, to assess purchasing intention with additional factors. Future research could also employ longitudinal methods to show how consumers’ habits and preferences change over time and what influences their buying decisions. This would also help to understand customer loyalty and how factors such as product quality, promotions, and social interactions affect their choice to shop at farmers’ markets.

A limitation of the research is its location, as geographical constraints in tourist-oriented areas of Istria restrict the generalizability of the results. The research was conducted in a representative Croatian coastal area, where the population increases significantly during the summer months due to tourism. The authors acknowledge that the geographical sites and the time of year in which the research was conducted may also produce different results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O., J.G. and A.Č.M.; methodology, A.Č.M. and T.Č.; software, A.Č.M.; validation, M.O., A.Č.M. and M.N.; formal analysis, A.Č.M.; investigation, M.O., J.G. and A.Č.M.; resources, M.O.; data curation, A.Č.M. and T.Č.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O., J.G., T.Č., M.N. and A.Č.M.; writing—review and editing, M.O., T.Č., M.N., J.G. and A.Č.M.; supervision, M.N. and M.O.; project administration, M.O.; funding acquisition, M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and publication of this work were funded by the Farmers Web Market project, which is financially supported by the Istrian County, the City of Pula-Pola, the City of Poreč-Parenzo, the City of Buje-Buie, the Municipality of Vrsar-Orsera, and the Municipality of Tar-Vabriga-Torre Abrega (Klasa: 402-08/24-01/157, Ur.broj: 2163-03/1-24-04).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the first author due to contractual obligations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the all anonymous contributors/farmers for participating in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Giampietri, E.; Koemle, D.B.A.; Yu, X.; Finco, A. Consumers’ Sense of Farmers’ Markets-Tasting Sustainability or Just Purchasing Food. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruch, M.L.; Ernst, M.D. Choosing Direct Marketing Channels for Agricultural Products; The University of Tennessee; Institute of Agriculture: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2010; Available online: https://utia.tennessee.edu/publications/wp-content/uploads/sites/269/2023/10/PB1796.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Gumirakiza, J.; Curtis, K.; Bosworth, R. Who attends farmers’ markets and why? Understanding consumers and their motivations. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Maples, M.; Morgan, K.; Interis, M.; Harri, A. Who buys food directly from producers in the southeastern United States? J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirog, R. Ecolabel Value Assessment Phase II: Consumer Perceptions of Local Foods; Iowa State University Leopold Center: Ames, IA, USA, 2004; Available online: https://farmlandinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/09/050504_ecolabels2_1.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Bond, J.K.; Thilmany, D.; Bond, C.A. Direct Marketing of Fresh Produce: Understanding Consumer Purchasing Decision. Choices 2006, 21, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Bavorova, M.; Unay-Gailhard, I.; Lehberger, M. Who buys from farmers’ markets and farm shops: The case of Germany. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zámková, M.; Rojík, S.; Prokop, M.; Činčalová, S.; Stolín, R. Consumers’ Behavior in the Field of Organic Agriculture and Food Products during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Czech Republic: Focus on a Comparison of Hyper-, Super- and Farmers’ Markets and Direct Purchases from Producers. Agriculture 2023, 13, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydas, A.; Yalman, F.; Bayat, M. Consumer Attitude towards Organic Food: Determinants of Healthy Behaviour. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2021, 1, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, H.; Dong, D. How strong is the demand for food through direct-to-consumer outlets? Food Policy 2018, 79, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, A.; Sherwood, N.E.; Larson, N.; Story, M. Community-supported agriculture as a dietary and health improvement strategy: A narrative review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, C.; Sánchez, C.; Limaico, K.; Abril, V.H. Motivations to consume agroecological food: An analysis of farmers’ markets in Quito, Ecuador. J. Agric. Rural. Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 2018, 119, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- April-Lalonde, G.; Latorre, S.; Paredes, M.; Hurtado, M.F.; Muñoz, F.; Deaconu, A.; Cole, D.C.; Batal, M. Characteristics and Motivations of Consumers of Direct Purchasing Channels and the Perceived Barriers to Alternative Food Purchase: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Ecuadorian Andes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čehić Marić, A.; Težak Damijanić, A.; Oplanić, M. Customers motivations for purchasing agricultural food products direct from farmers. AEC 2024, 14, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, J.; Fang, Z. Exploring the relevance of consumers’ awareness and demand of local food from the concept of local consumption. Agric. Ext. J. 2018, 63, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, G. Impact of media use on consumer product knowledge. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2020, 48, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicia, G.; Furno, M.; Del Giudice, T. Do consumers’ values and attitudes affect food retailer choice? Evidence from a national survey on farmers’ market in Germany. Agric. Food Econ. 2021, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe-Lord, L. Food Safety Knowledge and Socio-Demographic Factors of Participants in DC Farmers Markets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, A52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, S.; Inumula, K.M. Farmers Markets: An Analysis of the Determinants of Consumers Attitudes and Behavior. Asian J. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2021, 11, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.C.; Chang, H.P. Consumers’ Perception of Food and Agriculture Education in Farmers’ Markets in Taiwan. Foods 2022, 11, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, B. Theorizing Consumer Perceptions of Food “Quality” at Farmers’ Markets. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2023, 36, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.M.; Spittler, A.; Ahern, J. A profile of farmers’ market consumers and the perceived advantages of produce sold at farmers’ markets. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2005, 36, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, C.; Smith, S. Purchasing habits of senior farmers’ market shoppers. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 30, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.Y.; Gibson, K.E.; Wright, K.G.; Neal, J.A.; Sirsat, S.A. Food safety and food quality perceptions of farmers’ market consumers in the United States. Food Control 2017, 79, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouryieh, M.; Khouryieh, H.; Daday, J.K.; Shen, C. Consumers’ perceptions of the safety of fresh produce sold at farmers’ markets. Food Control 2019, 105, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, Y.S.; Arsil, P.; Brindal, M.; Teoh, C.T.; Lim, H.W. Motivations underlying consumers’ preference for farmers’ markets in Klang Valley: A means-end chain approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Leviten-Reid, C. Consumers’ views on local food: Insights from a survey of Madison, Wisconsin residents. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2004, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R.; Holmes, M.; Arunsopha, V.; Chin, N.; Le, T.; Maung, S.; Shum, M. Consumer Choice and Farmers’ Markets. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2014, 27, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagan, R.B.; Morris, D. Consumer quest for embeddedness: A case study of the Brantford Farmers’ Market. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, G.P.; Sánchez, J.G.; Vignali, G.; Chaillot, A. Latent consumers’ attitude to farmers’ markets in NorthWest England. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benos, T.; Burkert, M.; Hüttl-Maack, V.; Petropoulou, E. When mindful consumption meets short food supply chains: Empirical evidence on how higher-level motivations influence consumerss. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, B.-K.; Lee, K.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Somsong, P. Determinants of actual purchase behavior in farmers’ markets. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, D.; Colasanti, K.; Ross, R.B.; Smalley, S.B. Locally grown foods and farmers markets: Consumer attitudes and behaviors. Sustainability 2010, 2, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J.L.; Wiley, J.B.; Wirth, F.F. Who are the locavores? J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, L.; LeRoux, M.N.; Schmit, T.M. Increasing customer purchases at farmers markets using point-of-sale Scanner Data. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. Assoc. 2023, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.J. Farmers’ markets as retail spaces. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 582–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, P.; Collie, V.; Kvarnbrink, E.; Colquhoun, A. Shopping at the farmers’ market: Consumers and their perspectives. J. Foodserv. 2009, 20, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maró, Z.M.; Maró, G.; Jámbor, Z.; Czine, P.; Török, Á. Profiling the consumers of farmers’ markets: A systematic review of survey-based empirical evidence. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2023, 38, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzling, L.; Shaw, B.; Wolnik, D. U.S. farmers market attendance and experiences: Descriptive results from a national survey. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2025, 14, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavorova, M.; Sănduță, D.C.; Pieroni, A.; Ahado, S.; Pilarova, T. Why and how often urban people buy food at farmers’ markets: Insights from Moldova. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 3513–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onianwa, O.; Mojica, M.N.; Wheelock, G. Consumer characteristics and views regarding farmers’ markets: An examination of on-site survey data of Alabama consumers. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2006, 37, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, J.S. Privilege and exclusion at the farmers market: Findings from a survey of shoppers. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bussel, L.M.; Kuijsten, A.; Mars, M.; van’t Veer, P. Consumers’ perceptions on food-related sustainability: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Azcárate, M.; Maceín, J.L.C.; Bardají, I. Why buying directly from producers is a valuable choice? Expanding the scope of short food supply chains in Spain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Moruzzo, R.; Granai, G. Farmers’ markets contribution to the resilience of the food systems. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, F.R.; Solanki, S.; Inumula, K.M.; Daouk, A.; Abdel Rahman, N.; Tahan, S.; Ibnou-Laaroussi, S. The Role of Sustainability in Shaping Customer Perceptions at Farmer’ Markets: A Quantitative Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, B.; Byun, R.; Mitchell, E.; Thompson, S.; Jalaludin, B.; Torvaldsen, S. Seeking fresh food and supporting local producers: Perceptions and motivations of farmers’ market customers. Aust. Plan. 2018, 55, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; O’Neill, M.A. A comparative study of farmers’ markets visitors’ needs and wants: The case of Alabama. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, N.; Preston, K.L. Willingness to pay for local food?: Consumer preferences and shopping behavior at Otago Farmers Market. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adanacıoğlu, H. Factors affecting the purchase behaviour of farmers’ market consumers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Službeni Glasnik Grada Poreča, 21/2024. Available online: https://www.porec.hr/cmsmedia/sadrzaj/glasnik/2024/SLU%C5%BDBENI%20GLASNIK%20GRADA%20PORE%C4%8CA-PARENZO%2021%202024.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Olson, K.; Ganshert, A. Remember, You Can Complete This Survey Online! Web Survey Links and QR Codes in a Mixed-Mode Web and Mail General Population Survey. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2025, 43, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis. A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, M.B. Rotation of principal components. J. Clim. 1986, 6, 293–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursachi, G.; Horodnic, I.A.; Zait, A. How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.S.; Ariff, M.S.B.M.; Zakuan, N.; Tajudin, M.N.M.; Ismail, K.; Ishak, N. Consumers perception, purchase intention and actual purchase behavior of organic food products. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014, 3, 378. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Liu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S. The influence of consumer perception on purchase intention: Evidence from cross-border E-commerce platforms. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.