Beyond Standards: Framework for Monitoring, Protection, and Conservation of Highly Vulnerable Cultural Heritage Sites in the Context of Anthropopressure and Climate Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Built Heritage, Anthropopressure and Climate Change

1.2. Anthropopressure, Climate Change and Hydrogeological Risk

1.3. Beyond Standards: Auschwitz-Birkenau Master Plan for Preservation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Laboratory Methods (Cores, Tests)

- Foundation cores were taken from pre-prepared test pits using a wet diamond drill (75 mm diameter), while cores from external walls were taken using a dry diamond drill with diameters of 100 mm and 50 mm (PN-EN 1015).

- Given the nature of the structures, sampling was kept to an absolute minimum, targeted at the least visually exposed locations and carried out so as to avoid any damage to drawings or inscriptions.

- Core diameters were intentionally smaller than the standard 150 mm recommended in normative testing methods (PN-EN 1015) in order to limit the impact on the historic fabric.

2.2. Wall Deformations, Diagnostics, and Stability Assessment Methods

- Extensive wall deformations in multiple directions were documented, alongside widespread cracking, fissuring, and spalling of brick masonry.

- To optimise repair strategies, cracks were classified by aperture (dilation), with targeted measures assigned to each class.

- Tests indicated high homogeneity in historic mortars but large variance in the compressive strength of historic bricks, and consequently in masonry core strength. The constrained sampling strategy (by necessity) also contributed to scatter in measured values.

- Overall masonry strength was below standard reference values, consistent with initial assessments of long-term environmental exposure.

2.3. Timber Roof Trusses: Condition Assessment and Reinforcement Trials

- Normative sampling for destructive laboratory tests of timber (PN-EN 1995 [45]) was not feasible. Instead, a pioneering programme of drilling-resistance testing (RESI) was undertaken (IML-RESI, F series; IML Instrumenta Mechanik Labor GmbH, Wiesloch, Germany), combined with assessment of biological surface degradation, to inform assignment of timber “classes” for structural–strength analysis.

- The only defensible approach was to correlate multiple characteristics from different non-destructive and minor-destructive tests to derive practicable design values.

2.4. Conservation and Safeguarding Methods

- Principles, developed through research, for individual load-bearing criteria of timber roof-truss elements and for their strengthening using methods that do not alter their appearance;

- Investigations recommended for implementation to verify in practice the technology for dealing with deformed and out-of-plumb gable and longitudinal walls, together with an execution manual for the practical implementation of such procedures;

- Methods for strengthening the subsoil and the foundations of the buildings based on practices proven in the field but not covered in the literature, referred to as reinforced compaction grouting.

- Restoring the original geometry and characteristics of deformed and cracked external walls while ensuring visitor safety and preserving their original structure;

- Ensuring the required safety and serviceability of roof load-bearing systems and coverings;

- Protecting fittings such as window and door joinery, chimneys, the rudimentary heating system, internal partitions, and prisoners’ bunks;

- Removing secondary safeguarding elements that have, in many cases, exacerbated damage to the original fabric;

- Stabilising the foundations of residential barracks; protecting foundations and floors against frost heave; and protecting masonry and fittings (partition walls) against capillary rising damp and moisture generated by plant growth and micro-organisms.

3. Results

3.1. Auschwitz II-Birkenau Barrack (B-145)

3.1.1. Description

3.1.2. Challenges

3.1.3. Results

3.2. Auschwitz II-Birkenau Kitchen (B-91)

3.2.1. Description

3.2.2. Challenges

3.2.3. Results

- A geotechnical analysis of the ground conditions with comparison to archival geotechnical information;

- On-site sampling and laboratory testing of concrete from the foundations;

- Investigations of the masonry walls;

- assessments of moisture content and salt contamination in the masonry and concrete; examinations of the timber elements;

- A full analysis of the deformation-measurement results for barrack B-91 and its discrete structural components, considered in the context of the proposed construction-structural safeguarding and strengthening solutions.

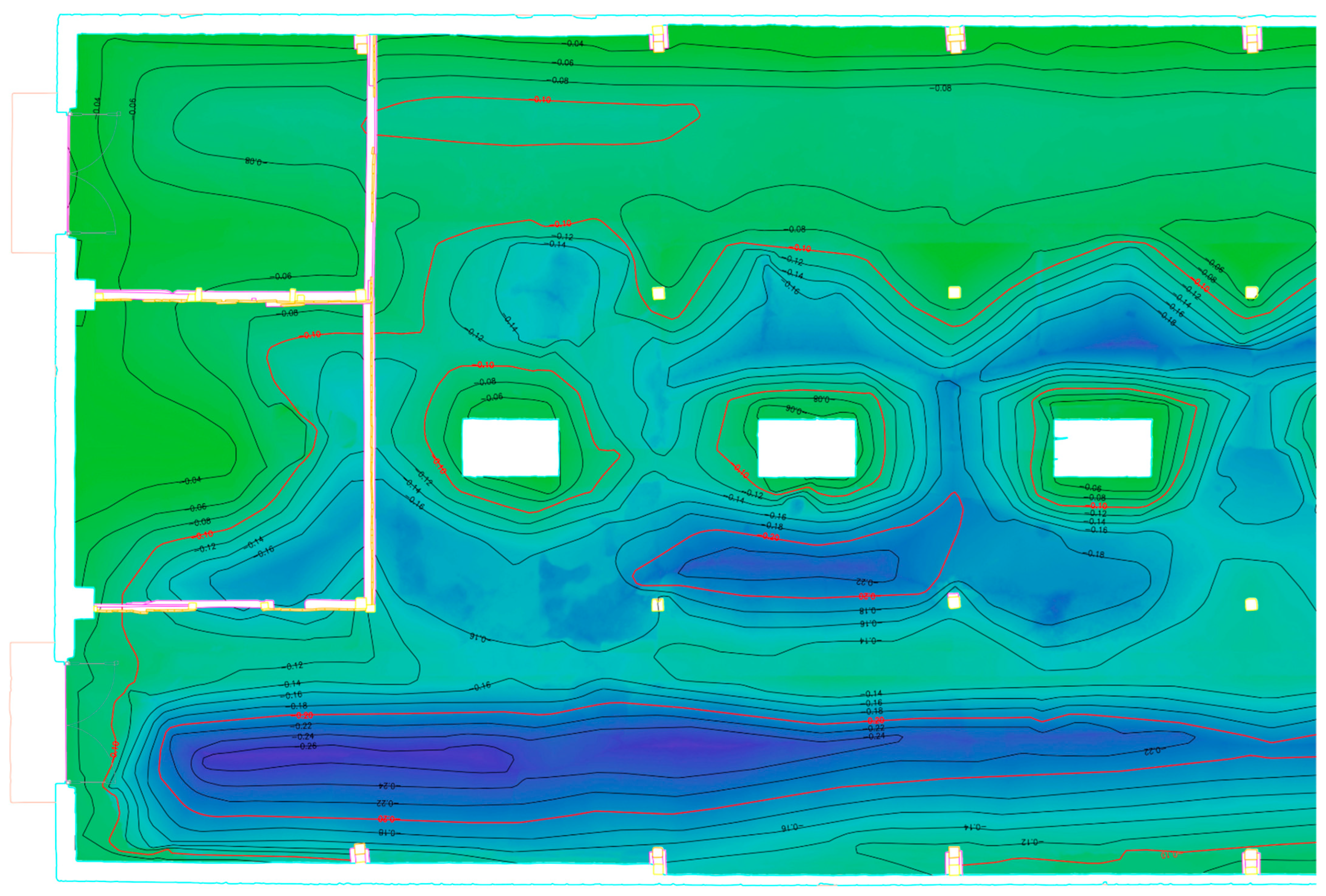

3.3. Auschwitz II-Birkenau Lavatory (B-112)

3.3.1. Description

3.3.2. Challenges

3.3.3. Results

3.4. Summary of the Results

| Deformations [mm] | B-91 | B-112 | B-145 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal walls | −20 | −40 | −20 |

| +100 | +40 | +60 | |

| Δ120 | Δ80 | Δ80 | |

| Gable walls | −0 | −20 | −40 |

| +60 | +40 | +60 | |

| Δ60 | Δ60 | Δ100 | |

| Floors | +60 | +80 | +40 |

| −260 | −200 | −160 | |

| Δ320 | Δ280 | Δ200 |

| Load-Bearing Capacity | B-91 | B-112 | B-145 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundations | Not exceeded 1 | Not exceeded 1 | 125% |

| Longitudinal walls | 336% 2 | 126% 2 | 158% 2 |

| Gable walls | 512% 2 | 250% 2 | 215% 2 |

| Brick pillars | 345% 2 | 338% 2 | 379% 2 |

| Rafters | 138% | 135% | 155% |

4. Discussion

4.1. Beyond Categories and Standards

4.2. Net Zero Vulnerability

- Rising anthropopressure on heritage areas and assets, understood not only as a socio-economic phenomenon but also as prolonged physical action that affects the building fabric;

- Multifaceted impacts of climate change;

- Limited scope for mitigation measures within protected areas.

5. Conclusions

- Comprehensively recognise dynamic processes such as anthropopressure and climate change,

- Correctly and realistically determine the scope and form of protection within buffer zones, and

- Undertake remedial or compensatory measures at the source of the problem, or where mitigation of its effects is feasible—thereby achieving the condition that the authors term Net Zero Vulnerability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CUT | Cracow University of Technology also known as Politechnika Krakowska, Poland |

| MPP | Master Plan for Preservation |

| PN-EN 338 | Structural timber: Strength classes |

| PN-EN 771 | Specification for masonry units. Part 6: Natural stone masonry units |

| PN-EN 1015 | Methods of testing mortar for masonry. Part 1: Determination of particle size distribution (by sieve analysis) |

| PN-EN 16455 | Conservation of cultural heritage: Extraction and determination of soluble salts in natural stone and related materials used in and from cultural heritage |

| PN-EN 16682 | Conservation of cultural heritage: Methods of measurement of moisture content, or water content, in materials constituting immovable cultural heritage |

| PN-EN 1912 | Structural Timber: Strength classes. Assignment of visual grades and species |

| PN-EN 1991 | Eurocode 1: Actions on structures. Part 1–1: General actions: Densities |

| PN-EN 1992 | Eurocode 2: Design of concrete structures. Part 1–1: General rules and rules for buildings, bridges and civil engineering structures |

| PN-EN 1995 | Eurocode 5: Design of timber structures. Part 1–1: General rules and rules for buildings |

| PN-EN 1996 | Eurocode 6: Design of masonry structures. Part 1–1: General rules for reinforced and unreinforced masonry structures |

| PN-EN 1997 | Eurocode 7: Geotechnical design. Part 1: General rules |

References

- Brimblecombe, P. Refining climate change threats to heritage. J. Inst. Conserv. 2014, 37, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, J.; Fluck, H.; Wiggins, M. Predicting and adapting to climate change: Challenges for the historic environment. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2017, 8, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosher, L.; Kim, D.; Okubo, T.; Chmutina, K.; Jigyasu, R. Dealing with multiple hazards and threats on cultural heritage sites: An assessment of 80 case studies. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2019, 29, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Nearly Three-Quarters of World Heritage Sites Are at High Risk from Water-Related Hazards. UNESCO World Heritage Convention. 1 July 2025. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2788 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- ICOMOS Climate Change and Heritage Working Group. The Future of Our Past: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/Future-of-Our-Pasts-Report-min.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Nixon, S. EU Overview of Methodologies Used in Preparation of Flood Hazard and Flood Risk Maps; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Porębska, A.; Godyń, I.; Radzicki, K.; Nachlik, E.; Rizzi, P. Built heritage, sustainable development, and natural hazards: Flood protection and UNESCO world heritage site protection strategies in Krakow, Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, K.; Jackson, R.; O’Connell, S.; Karunarthna, D.; Anantasari, E.; Retnowati, A.; Niemand, D. Cultural heritage and risk assessment: Gaps, challenges, and future research directions for the inclusion of heritage within climate change adaptation and disaster management. Clim. Resil. Sustain. 2021, 1, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatorić, S.; Seekamp, E. Are cultural heritage and resources threatened by climate change? A systematic literature review. Clim. Change 2017, 142, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzicki, K.; Porębska, A.; Paruch, R.; Godyń, I.; Muszyński, K. Net Zero Vulnerability: Zagrożenia związane z oddziaływaniem wód powierzchniowych i podziemnych na obszary i obiekty zabytkowe; Korelacja zagrożeń i minimalizacja ryzyka w kontekście antropopresji i zmian klimatu/Correlating hazards and minimising risk from surface- and groundwater impacts on built heritage in the context of anthropopressure and climate change. In Scientific Conference on Cultural Heritage and Hydrogeological Risk, Kraków, Poland, 14–15 November 2022; Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa/National Institute of Cultural Heritage: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Porębska, A.; Paruch, R. Net Zero Vulnerability: Problematyka określania zakresu i obszarów negatywnych oddziaływań na szczególnie wrażliwe obiekty podlegające ochronie konserwatorskiej/Defining the scope and zones of adverse influence on highly vulnerable built heritage subject to statutory protection. In Scientific Conference on Cultural Heritage and Climate Change, Warsaw, Poland, 28–29 November 2023; Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa/National Institute of Cultural Heritage: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowska, M.; Czop, M. An Assessment of Hydrological Risks to Historic Buildings and Compounds with a View to Their Prevention and Limiting the Negative Impacts of Climate Change and Anthropopressure; Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa/National Institute of Cultural Heritage: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://ksiegarnia.nid.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Ocena-i-profilaktyka-zagrozn-hydrologicznych_EN.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Del Blanco, C.; Montedoro, L. Cultural tourism pressure on historic centres: Its impact on public space and intervention strategies for its mitigation. Florence, Italy, as a case study. Hous. Environ. 2023, 42, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sesana, E.; Gagnon, A.S.; Ciantelli, C.; Cassar, J.; Hughes, J. Climate change impacts on cultural heritage: A literature review. WIREs Clim. Change 2020, 12, e710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 15999-1:2025; Standards Preserving Cultural Heritage: Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Guidelines for Design of Showcases for Exhibition and Preservation of Objects. Part 1: General Requirements. European Standards Institution: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. Available online: https://www.cencenelec.eu/news-events/news/2025/eninthespotlight/2025-08-04_culturalheritage/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Fassina, V. CEN TC 346 Conservation of Cultural Heritage-Update of the Activity After a Height Year Period. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory: Preservation of Cultural Heritage; Lollino, G., Giordan, D., Marunteanu, C., Christaras, B., Yoshinori, I., Margottini, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassina, V. The activity of the European Standardization Committee CEN/TC 346 Conservation of Cultural Heritage from 2004 to 2020. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auschwitz-Birkenau Master Plan for Preservation. Available online: https://www.auschwitz.org/en/museum/preservation/master-plan-for-preservation (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Karczmarczyk, S.; Bereza, W.; Paruch, R.; Šefčić, E.; Metych, W.; Celadyn, W. Raport Końcowy: Badania nad Opracowaniem Metod Konserwacji, Zabezpieczenia i Wzmocnienia Konstrukcji Obiektów, Elementów ich Wykończenia Oraz ich Podłoża Gruntowego z Uwzględnieniem Statyki i Fizyki Budowli Występujących na Terenie Państwowego Muzeum Auschwitz—Birkenau; Politechnika Krakowska: Kraków, Poland. 2015. Available online: https://auschwitz.org/gfx/auschwitz/userfiles/auschwitz/gpk/04_badania_wstep/konstrukcja_obiektow/04.02._wyniki_badan.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Kańka, S.; Stryszewska, T.; Tracz, T. Methods of testing and assessing technical condition of chosen building structures located in the area of Auschwitz-Birkenau National Museum in Oświęcim. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2015, 19, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysek, P.; Stryszewska, T.; Kańka, S. Experimental studies of brick masonry in the Auschwitz II-Birkenau former death camp buildings. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 68, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaś-Maciaszczyk, J.; Pióro, R. Conservation issues and assumptions for the protection of objects of the former KL Auschwitz-Birkenau. Prot. Cult. Herit 2017, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryszewska, T.; Kańka, S. Współczesne metody badania materiałów budowlanych pochodzących z zabytkowych obiektów murowanych. Mater. Bud. 2019, 559, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szociński, M.; Miszczyk, A.; Darowicki, K. Condition of reinforced concrete structures and their degradation mechanism at the former Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp. Stud. Conserv. 2019, 64, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celadyn, W.; Porębska, A.; Paruch, R.; Karczmarczyk, S. Methods for protecting, conserving, repairing and reinforcing highly vulnerable world heritage sites: Guidelines for the sector BI of the former KL Auschwitz II-Birkenau Master Plan for Preservation. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 68S, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromysz, K.; Szoblik, Ł.; Drabczyk, Z.; Tanistra-Różanowska, A. Analysis of causes of damage to masonry walls in the historic barrack No. B-115 in the former KL Auschwitz II—Birkenau camp. MATEC Web Conf. 2024, 396, 05003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartyzel, B. (Ed.) To Preserve Authenticity: The Conservation of Brick Barracks at the Former KL Auschwitz II-Birkenau; Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu: Oświęcim, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bartyzel, B.; Lipiński, Ł.; Sawicki, P. (Eds.) Education and Remembrance. Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum and Memorial 2024 Annual Report; Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu: Oświęcim, Poland, 2025; Available online: https://www.auschwitz.org/muzeum/aktualnosci/pamiec-zobowiazuje-sprawozdanie-muzeum-auschwitz-2024-,2573.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Webber, J. The future of Auschwitz: Some personal reflections. Relig. State Soc. 1992, 20, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, D. Oświęcim ring road development as UNESCO world cultural heritage site buffer zone protection case study. Architectus 2023, 75, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. World Heritage Resource Manual Preparing World Heritage Nominations, 2nd ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/preparing-world-heritage-nominations/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural Natural Heritage. The General Conference of UNESCO Adopted on 16 November 1972 the Recommendation Concerning the Protection at National Level of the Cultural Natural Heritage; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 1972. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Konwencja w Sprawie Ochrony Światowego Dziedzictwa Kulturalnego i Naturalnego Przyjęta w Paryżu Dnia 16 Listopada 1972 r Przez Konferencję Generalną Organizacji Narodów Zjednoczonych dla Wychowania Nauki i Kultury na jej Siedemnastej sesji, D.z.U. 1976 nr 32 poz. 190. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19760320190 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- 2025 Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. WHC.25/01. 16 July 2025. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 23 Lipca 2003 o Ochronie Zabytków i Opiece nad Zabytkami. Dz.U.2003.162.1568 as Amended. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20031621568/U/D20031568Lj.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 27 Marca 2003 r. o Planowaniu i Zagospodarowaniu Przestrzennym. Dz.U.80.717 as Amended. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20030800717/U/D20030717Lj.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 7 Lipca 1994 Prawo Budowlane. Dz.U.2025.418. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20250000418/U/D20250418Lj.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- PN-EN-1996-1-1:2010; Eurocode 6: Projektowanie Konstrukcji Murowych; Część 1-1; Reguły Ogólne dla Zbrojonych i Niezbrojonych Konstrukcji Murowych/Design of Masonry Structures. Part 1–1: General Rules for Reinforced and Unreinforced Masonry Structures. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2010.

- PN-EN 16455:2014; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Determination of Soluble Salts in Natural Stone and Related Materials Used in Cultural Heritage. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2014.

- PN-EN 1991-1-1:2004; Eurokod 1: Oddziaływania na Konstrukcje; Część 1-1; Oddziaływania Ogólne, Ciężar Objętościowy, Ciężar Własny, Obciążenia Użytkowe w Budynkach/Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures; Part 1-1; General Actions—Densities, Self-Weight, Imposed Loads for Buildings. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2004.

- PN-EN 1991-1-3:2004; Eurokod 1: Oddziaływania na Konstrukcje; Część 1-3; Oddziaływania Ogólne–Obciążenie Śniegiem/Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures—Part 1-3: General Actions–Snow Loads. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2004.

- PN-EN 1991-1-4:2004; Eurokod 1: Oddziaływania na Konstrukcje; Część 1-4; Oddziaływania ogólne–Obciążenie Wiatru/Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures–Part 1-4: General Actions–Wind Actions. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2004.

- PN-EN 1992; Eurokod 2: Projektowanie Konstrukcji z Betonu. Część 1-1: Reguły Ogólne i Reguły dla Budynków, Mostów i Obiektów Inżynierii Budowlanej/Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures. Part 1–1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings, Bridges and Civil Engineering Structures. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2008.

- PN-EN 1995-1-1; Eurokod 5: Projektowanie Konstrukcji Drewnianych. Część 1-1: Zasady Ogólne/Eurocode 5: Design of Timber Structures. Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for buildings. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2010.

- PN-EN 1997-1-2008; Eurokod 7: Projektowanie Geotechniczne. Część 1: Zasady Ogólne./Eurocode 7: Geotechnical Design. Part 1: General Rules. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2008.

- PN-EN 1015-1:2002; Metody Badań Zapraw do Murów—Część 1: Określenie Gęstości Objętościowej Suchej Mieszanki i Gęstości Objętościowej Stwardniałego Zaprawy/Methods of Testing Mortar for Masonry. Part 1: Determination of Particle Size Distribution (by Sieve Analysis). Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2002.

- PN-EN 16682:2017; Konserwacja Dziedzictwa Kulturowego–Metody Pomiaru Zawartości Wilgoci lub wody w Materiałach Dziedzictwa Kulturowego/Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Methods of Measurement of Moisture Content, or Water Content, in Materials Constituting Immovable Cultural Heritage. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2017.

- PN-EN 771-6; Wymagania Dotyczące Elementów Murowych–Część 6: Elementy Murowe z Kamienia Naturalnego/Specification for Masonry Units. Part 6: Natural Stone Masonry Units. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; (Amended in 2015).

- PN-EN 338:2009; Drewno Konstrukcyjne. Klasy Wytrzymałości/Structural Timber: Strength Classes. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2009.

- PN-EN 1912:2012; Drewno Konstrukcyjne—Klasy Wytrzymałości—Przyporządkowanie klas Sortowania Wizualnego i Gatunków/Structural Timber: Strength Classes. Assignment of Visual Grades and Species. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny/Polish Standardization: Committee: Warsaw, Poland, 2009; Amended in 2024.

- UNESCO WHC: Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940–1945). Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/31/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Romão, X.; Paupério, E.; Pereira, N. A framework for the simplified risk analysis of cultural heritage assets. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 20, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Aarrevaara, E. Review of potential risk factors of cultural heritage sites and initial modelling for adaptation to climate change. Geosciences 2018, 8, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śladowski, G.; Paruch, R. Expert cause and effect analysis of the failure of historical structures taking into account factors that are difficult to measure. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2017, 63, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorczak-Cisak, M.; Kowalska-Koczwara, A.; Pachla, F.; Radziszewska-Zielina, E.; Szewczyk, B.; Śladowski, G.; Tatara, T. Fuzzy model for selecting a form of use alternative for a historic building to be subjected to adaptive reuse. Energies 2020, 13, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Adopted by the UNESCO General Conference on 17 October 2003. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- EU Policy for Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://culture.ec.europa.eu/cultural-heritage/eu-policy-for-cultural-heritage (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Łopuska, A. Autentyzm vs. udostępnienie. Granice kompromisów w konserwacji byłego obozu Auschwitz-Birkenau. Ochr. Dziedzictwa Kult. 2017, 3, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.; Barnett, J.; Brown, K.; Marshall, N.; O’Brien, K. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porębska, A.; Muszyński, K.; Godyń, I.; Racoń-Leja, K. City and water risk: Accumulated runoff mapping analysis as a tool for sustainable land use planning. Land 2023, 12, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Paruch, R.; Porębska, A. Beyond Standards: Framework for Monitoring, Protection, and Conservation of Highly Vulnerable Cultural Heritage Sites in the Context of Anthropopressure and Climate Change. Sustainability 2026, 18, 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010409

Paruch R, Porębska A. Beyond Standards: Framework for Monitoring, Protection, and Conservation of Highly Vulnerable Cultural Heritage Sites in the Context of Anthropopressure and Climate Change. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010409

Chicago/Turabian StyleParuch, Roman, and Anna Porębska. 2026. "Beyond Standards: Framework for Monitoring, Protection, and Conservation of Highly Vulnerable Cultural Heritage Sites in the Context of Anthropopressure and Climate Change" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010409

APA StyleParuch, R., & Porębska, A. (2026). Beyond Standards: Framework for Monitoring, Protection, and Conservation of Highly Vulnerable Cultural Heritage Sites in the Context of Anthropopressure and Climate Change. Sustainability, 18(1), 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010409