Abstract

Biodiversity knowledge is fundamental to conservation planning and sustainable environmental decision-making; however, general-purpose Large Language Models (LLMs) frequently produce hallucinations when responding to biodiversity-related queries. To address this challenge, we propose BioChat, a domain-specific question-answering system that integrates a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) framework with a Re-Ranker–based retrieval and routing mechanism. The system is built upon a verified biodiversity dataset curated by the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR), comprising 25,593 species and approximately 970,000 structured data points. We systematically evaluate the effects of embedding selection, routing strategy, and generative model choice on factual accuracy and hallucination mitigation. Experimental results show that the proposed Re-Ranker-based routing strategy significantly improves system reliability, increasing factual accuracy from 47.9% to 71.3% and reducing hallucination rate from 34.0% to 24.4% compared with Naive RAG baseline. Among the evaluated LLMs, Qwen2-7B-Instruct achieves the highest factual accuracy, while Gemma-2-9B-Instruct demonstrates superior hallucination control. By delivering transparent, verifiable, and context-grounded biodiversity information, BioChat supports environmental education, citizen science, and evidence-based conservation policy development. This work demonstrates how trustworthy AI systems can serve as sustainability-enabling infrastructure, facilitating reliable access to biodiversity knowledge for long-term ecological conservation and informed public decision-making.

1. Introduction

Biodiversity information plays a critical role in conservation planning, ecological monitoring, environmental education, and sustainable policy development. Accurate and reliable access to species-level knowledge is essential for protecting endangered species, preventing the spread of invasive organisms, and supporting evidence-based environmental decision-making. However, biodiversity data are often fragmented, highly technical, and difficult for non-experts, educators, and policymakers to access and interpret, creating a barrier between scientific knowledge and practical conservation action.

Recent advances in Large Language Models (LLMs) [1] have increased public access to scientific knowledge by enabling natural-language question answering (QA). Despite their convenience and expressive power, general-purpose LLMs frequently generate “hallucinations”, seemingly plausible but factually incorrect statements. In biodiversity-related applications, such errors can have serious consequences, including species misidentification, incorrect ecological interpretations, and the dissemination of misinformation in educational or policy contexts.

In sustainability-sensitive domains such as biodiversity conservation, these inaccuracies are not merely technical shortcomings but pose tangible ecological and societal risks. Consequently, ensuring factual reliability and transparency in biodiversity-oriented AI systems is not only a technical objective but a fundamental prerequisite for their responsible use in sustainable environmental knowledge dissemination.

Recent advances in Large Language Models (LLMs) [1], based on the Transformer architecture [2] have increased public access to scientific knowledge by enabling natural-language question answering (QA) [3]. Despite their convenience and expressive power, general-purpose LLMs frequently generate “hallucinations”, seemingly plausible but factually incorrect statements [4]. In biodiversity domains, unlike general topics, such errors can lead to irreversible ecological consequences, including misidentification of invasive species as native ones, propagation of incorrect ecological information, and flawed decision-making in legal or conservation policy contexts. Thus, ensuring factual reliability and provenance is not merely a technical optimization but a fundamental requirement for the safe deployment of AI in environmental conservation.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) has emerged as a promising approach to reduce hallucinations by grounding LLM responses in verified external knowledge sources [5,6,7,8]. However, naive RAG approaches rely heavily on the quality of the retrieval stage; if the retrieved documents are poorly matched to the query, hallucinations still occur [9]. However, generic RAG approaches often fail in biodiversity contexts due to the strict taxonomic hierarchy and the linguistic duality of scientific (Latin) versus common names [10,11]. Standard retrieval mechanisms struggle to capture these domain-specific nuances, leading to the retrieval of irrelevant documents or data inconsistencies [9,12].

To address these challenges, this study proposes BioChat, a high-fidelity, domain-specific QA system that integrates a RAG pipeline enhanced with a Re-Ranker–based retrieval mechanism. The system leverages verified biodiversity data from the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR). Crucially, not all user queries require retrieval from the biodiversity knowledge base. Queries falling outside the domain scope (e.g., general knowledge) should be handled via a fallback path to prevent context contamination. Accordingly, a reliable routing mechanism is necessary to distinguish between RAG-relevant (Type A) and fallback-appropriate (Type B) queries, as an unreliable router can lead to critical operational errors (e.g., False Negatives or False Positives), as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Common routing errors in RAG systems.

By improving both retrieval precision and generative reliability, BioChat aims to provide trustworthy and accessible biodiversity information, thereby supporting environmental education, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable decision-making.

1.1. Research Questions

This study addresses the research questions outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Research questions of the study.

1.2. Main Contributions

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- Quantitative Component Analysis: We systematically evaluate how domain-specific embedding models, routing strategies, and generator LLMs influence hallucination rates and factual accuracy in biodiversity-oriented question answering.

- Empirical Routing Threshold Optimization: We propose a reproducible methodology for determining an optimal routing threshold (τ = 0.02) through statistical analysis of re-ranker score distributions, enabling precision-oriented routing that effectively filters irrelevant or noisy queries.

- LLM Benchmark for Biodiversity: We establish a novel benchmark comparing six open-source LLMs (including Qwen2, Gemma-2, and Llama-3.1), demonstrating that instruction-following capability is more critical than model size for scientific reliability.

- Sustainable-Oriented System Blueprint: We present a high-fidelity, reproducible RAG framework designed to support environmental education and evidence-based conservation decision-making by reducing barriers to accessing expert-verified biodiversity data.

Rather than introducing new AI algorithms, this study demonstrates how existing retrieval-augmented generation techniques can be systematically integrated, calibrated, and evaluated to satisfy the stringent reliability requirements of biodiversity and sustainability-focused applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. Limitations of Large Language Models in Scientific Domains

Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in natural language understanding and generation, democratizing access to information across various fields [1,13]. However, in scientific domains requiring high factual precision, their utility is severely hampered by “hallucinations”—the generation of confident but factually incorrect information [4]. In ecology and conservation biology, where decisions rely on precise species identification and status verification, such ungrounded generation poses significant risks. Unlike creative writing or casual conversation, scientific inquiry demands strict adherence to provenance and factual accuracy. Consequently, reliance on parametric knowledge alone—where facts are implicitly stored in model weights—is insufficient for biodiversity applications, necessitating architectures that can ground generation in verifiable external data.

2.2. Evolution of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

To mitigate the hallucination problem, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) was introduced to combine parametric memory with non-parametric external knowledge bases [5]. Early “Naive RAG” approaches retrieved documents based solely on vector similarity (Bi-Encoder) and fed them into the generator. While effective for simple queries, this method often fails when the retrieved context is irrelevant or noisy, leading to “garbage-in, garbage-out” hallucinations [6,9]. Recent advancements have moved towards “Modular RAG” or “Advanced RAG” architectures, which incorporate intermediate validation steps. Specifically, Re-ranking strategies using Cross-Encoders have proven effective in filtering out irrelevant documents before they reach the LLM [14,15]. By scoring the relevance of retrieved candidates at a granular level, these methods significantly improve the quality of the context window, thereby enhancing the factual consistency of the final output.

2.3. Challenges in Biodiversity Informatics

Biodiversity data presents unique challenges for information retrieval and NLP systems. Unlike general web text, biological data is structured around a rigid taxonomic hierarchy and is characterized by the linguistic duality of scientific names (Latin) versus common names (vernaculars) [10]. Thessen et al. [10] highlighted that standard NLP techniques often struggle with the ambiguity of taxonomic names and the scarcity of biological entities in training corpora. Furthermore, Patterson et al. [11] emphasized the difficulties in linking digital biodiversity information due to synonymy (multiple names for one species) and homonymy (same name for different species). Zizka et al. [12] further noted that large-scale biodiversity databases like GBIF, while valuable, often contain data inconsistencies that can propagate errors if not carefully filtered. These studies suggest that a generic AI approach is ill-suited for biodiversity; instead, a domain-specific system capable of handling strict nomenclature and verifying data provenance is essential for reliable conservation decision-making.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Proposed High-Fidelity RAG Pipeline: BioChat

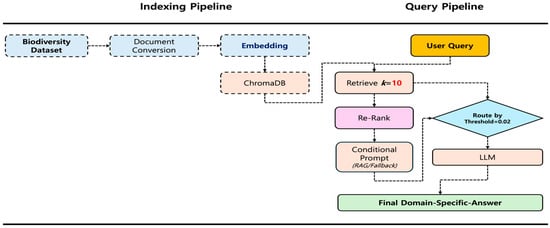

We designed and implemented a RAG pipeline optimized for high-fidelity responses and hallucination reduction. The system comprises two main phases: an offline indexing pipeline and an online query processing pipeline, integrated into a user-facing prototype.

3.1.1. Indexing Pipeline

The source data—a CSV file containing 25,593 species and 38 attributes, totaling approximately 970,000 data points—were provided by the NIBR. These were preprocessed and transformed into LangChain document objects. For each species, key textual fields such as Korean name, scientific name, overview information, morphological information, and distribution information were combined into a single formatted string to serve as the page_content, whereas essential identifiers (e.g., source_name and scientific_name) were stored in the metadata to enable precise retrieval evaluation. The resulting document objects were then embedded using a domain-specific embedding model and indexed into a persistent ChromaDB vector store for efficient similarity search and retrieval [16,17].

3.1.2. Query Processing Pipeline

The online query pipeline (Figure 1) processes user inputs through a five-stage sequence encompassing retrieval, reranking, routing, contextual generation, and postprocessing. First, the user query is embedded using the same model employed in the indexing pipeline, and a k-nearest neighbor search (k = 10) is performed on ChromaDB to obtain candidate documents. These candidates are then reranked by the Dongjin-kr/ko-reranker cross-encoder [14,15,18], which computes fine-grained relevance scores (0.0–1.0) based on query–document interactions. The highest score is compared with a predefined threshold (RERANK_THRESHOLD = 0.02) to determine the response path: if the score exceeds the threshold, the query follows the RAG path; otherwise, it is routed to the fallback path. In the RAG path, the top-ranked documents (N = 3) are assembled into a context block [19] and inserted into a RAG_PROMPT_TEMPLATE, which constrains the LLM to generate answers strictly within the provided context. In contrast, the fallback path relies on a FALLBACK_PROMPT_TEMPLATE, which permits responses based on the model’s general knowledge. Finally, the generative LLM produces the answer, any residual prompt tokens are removed, and a citation (“Source: NIBR Bioinformatics” or “Source: Generative AI Result”) is appended according to the selected path.

Figure 1.

System architecture diagram: a flowchart showing the indexing pipeline.

3.1.3. Human-in-the-Loop Feedback Mechanism

To address the static nature of the knowledge base, we implemented a human-in-the-loop feedback mechanism that enables users to report incorrect or hallucinated answers through the UI. All feedback is logged for review by a data manager. Verified corrections (e.g., taxonomic updates or new species information) are then used to manually update the source CSV file and trigger a reindexing of the vector database, ensuring the system’s long-term accuracy, adaptability, and sustainability.

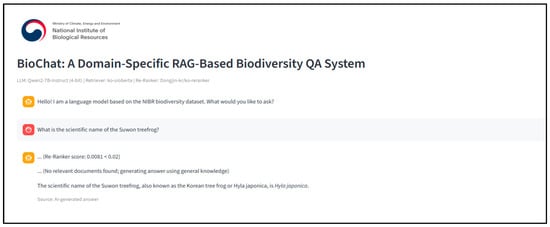

3.1.4. System Prototype

To demonstrate the practical applicability of the proposed pipeline and provide an interface for user interaction and qualitative evaluation, we developed a prototype web application, BioChat, using Streamlit (Figure 2). This application integrates all major system components—including query embedding, retrieval, reranking, routing, and answer generation—into an interactive interface that allows end users to submit natural language queries related to Korean biodiversity. Retrieved documents, relevance scores, and generated responses are displayed in real time, enabling transparent visualization of the model’s decision-making process.

Figure 2.

BioChat Streamlit application interface.

Additionally, BioChat supports dual-mode inference (RAG path and fallback path) and provides visual indicators for confidence levels, allowing users and researchers to qualitatively assess the effectiveness of the confidence-based routing strategy. This interface also facilitates comparative evaluation across multiple LLMs (Section 3.2.3), providing a practical and reproducible tool for both demonstration and empirical analysis of the proposed biodiversity-focused RAG framework.

3.2. Evaluation Setup

3.2.1. Evaluation Dataset Construction

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed pipeline, we constructed a 400-item question–answer (Q&A) evaluation dataset derived from the NIBR biodiversity data. The dataset comprises two complementary question types designed to test retrieval-based and generative capabilities. Type A includes manually crafted questions with ground-truth answers extracted directly from the NIBR dataset, using stratified sampling across taxonomic groups to ensure balanced representation of species. Type B includes manually designed questions covering general knowledge, external domain knowledge, fictional concepts, opinion/philosophical topics, and false premises—all intentionally beyond the scope of the NIBR dataset. Each record contains a unique query_id, question, ground_truth_answer, and answer_type (“RAG” or “Fallback”), along with source identifiers for Type A entries. This enables a systematic and controlled assessment of retrieval accuracy and hallucination control across distinct query types.

3.2.2. Baseline Systems

For evaluation, all experiments employed the ko-sroberta-multitask embedding model and the Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct LLM. We compared three retrieval–generation configurations to assess the impact of different routing strategies.

- Baseline 1: Naive RAG (no routing) represents a simple pipeline that always retrieves the top three documents based solely on bi-encoder similarity, forcing the RAG path regardless of query relevance.

- Baseline 2: RAG + L2 Distance Threshold Routing introduces a routing mechanism that decides between the RAG and fallback paths using the L2 squared distance obtained from ChromaDB retrieval results. The threshold value (L2_THRESHOLD = 110.0) was determined empirically from preliminary distance distribution analysis.

- Proposed: RAG + Reranker Threshold Routing represents the full pipeline described in Section 3.1.2, where the routing decision is based on the reranker score threshold (RERANK_THRESHOLD = 0.02) derived from score distribution analysis (Section 3.2.1). This configuration leverages cross-encoder-based semantic scoring to more precisely distinguish contextually relevant queries from irrelevant ones.

3.2.3. Selection of Generative Language Models

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed biodiversity-oriented RAG pipeline, six state-of-the-art open-source Large Language Models (LLMs) were compared as shown in Table 3: Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct (Alibaba Cloud, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China), Gemma-2-9B-Instruct (Google DeepMind, London, UK), EXAONE-3.5-7.8B-Instruct (LG AI Research, Seoul, Republic of Korea), Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.3 (Mistral AI, Paris, France), and KoAlpaca-Polyglot-12.8B (Kakao Brain, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea). All models were executed locally under identical conditions to ensure fair comparison. Each model was run locally using 4-bit bitsandbytes (BnB) quantization [20] to ensure consistent inference speed and memory efficiency under a 32-GB VRAM environment.

Table 3.

Specifications and configurations of the evaluated Large Language Models (LLMs).

3.2.4. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed RAG-based system, we applied three categories of evaluation metrics, each aligned with a specific experimental objective.

- Retrieval Performance

Retrieval effectiveness was evaluated using Type A questions to evaluate the effectiveness of the initial retrieval stage. Two standard information retrieval metrics were used: Recall@K and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR). Recall@K (K = 1, 3, 5, 10) represents the proportion of queries in which the correct source document appears within the top-K retrieved results. MRR indicates the average reciprocal rank of the first correct document across all queries, thereby indicating the overall ranking precision of the embedding model.

- 2.

- Routing Performance

Routing accuracy was evaluated using all 400 questions to assess the reliability of the confidence-based routing mechanism that distinguishes between the RAG and fallback paths. Four standard binary classification metrics were used: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, with the RAG path defined as the positive class. These indicators collectively assess the classification performance and stability of the routing decision process.

- 3.

- Final Answer Performance

The quality of the final answers was manually annotated to evaluate factual consistency and hallucination tendency [24]. Factual accuracy denotes the proportion of model-generated responses that were factually consistent with the ground_truth_answer (scored as 1 = correct, 0 = incorrect). The hallucination rate indicates the proportion of responses containing information not grounded in the ground_truth_answer or, for RAG outputs, the retrieved context (1 = hallucination, 0 = none). Together, these metrics capture the factual reliability and grounding effectiveness of the proposed system. All 400 queries (Type A = 300, Type B = 100) were manually annotated by two domain experts following standardized guidelines. Interannotator agreement (Cohen’s κ = 0.87) [25] confirmed annotation consistency. Each annotation included binary labels for factual accuracy (1 = correct, 0 = incorrect) and hallucination presence (1 = hallucination, 0 = none). Detailed annotation protocols and examples are provided in Appendix B to support reproducibility and data transparency.

3.3. Implementation Details

The proposed BioChat system was implemented using Python (v3.11.14; Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA). The RAG pipeline was constructed with LangChain (v1.0.2; LangChain Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) [26]. Models were loaded and executed using Hugging Face Transformers (v4.57.1; Hugging Face Inc., New York, NY, USA), sentence-transformers (v2.7.0), bitsandbytes (v0.48.1), and langchain-huggingface (v1.0.0). The vector store employed was ChromaDB (v1.2.1; Chroma Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), and the Web UI prototype (BioChat) was built using Streamlit (v1.50.0; Streamlit Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) as described in Section 3.1.4. All experiments were conducted on a server running Ubuntu (v24.04.3 LTS; Canonical Ltd., London, UK) equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5090 GPU (NVIDIA Corp., Santa Clara, CA, USA) featuring 32,607 MiB of VRAM. Evaluation scripts were developed to ensure systematic execution and consistent data collection. Additionally, all hyperparameters, prompt templates, and configuration parameters were fixed across experiments for reproducibility. The full RAG and fallback prompt templates, along with the parameter settings (Top-k = 10, Top-N = 3, RERANK_THRESHOLD = 0.02), are provided in Appendix A. To ensure transparency, all evaluation scripts and metadata have been prepared. To ensure reproducibility while maintaining the review process protocols, the full project repository URL will be provided in the final version of the manuscript upon acceptance.

4. Results

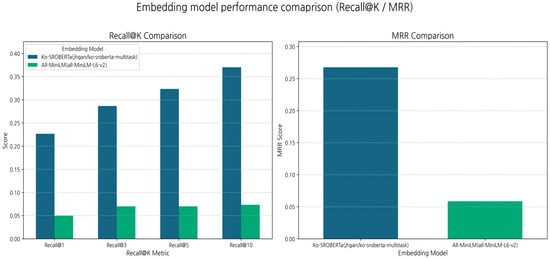

4.1. Experiment 1: Embedding Model Performance

As shown in Table 4 and Figure 3 and Figure 4, the Korean-specific model ko-sroberta-multitask significantly outperformed the general-purpose model all-MiniLM-L6-v2 across all retrieval metrics. Its MRR was approximately 4.6× higher (0.2675 vs. 0.0587), and Recall@10 was five times higher (0.3700 vs. 0.0733). These results confirm that domain- and language-specific embeddings [27,28,29] are crucial for achieving strong initial retrieval performance (addressing RQ1). However, a Recall@10 value of 0.3700 indicates that the initial retrieval still fails to identify the correct document in over 60% of cases [30], highlighting the need for a reranker.

Table 4.

Embedding model retrieval performance comparison.

Figure 3.

Embedding model performance comparison (Recall@K/MRR).

Figure 4.

Routing strategy performance comparison (Dark blue bars represent the L2 Threshold; green bars represent the proposed Re-Ranker).

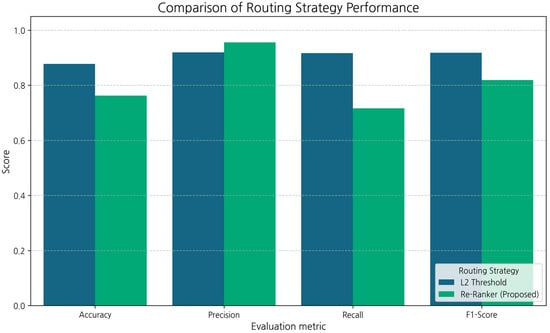

4.2. Experiment 2: Routing Strategy Performance

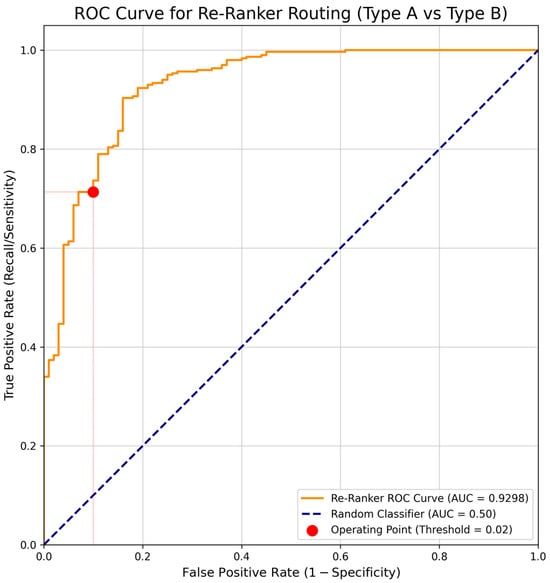

We first examined the reranker score distribution for Type A (RAG) and Type B (fallback) questions. Type A questions exhibited a median score of 0.13, whereas 90% of Type B questions scored below 0.018. To optimize recall without excessively reducing precision, we set the RERANK_THRESHOLD = 0.02. Table 5 and Figure 5 compare the performances of the routing strategies (excluding Naive RAG, which lacks a router). The L2 Threshold method achieved higher accuracy and recall, whereas the proposed (reranker) method achieved significantly higher precision (0.9556). This suggests that although the L2 method attempts the RAG path more frequently (high recall), it also produces more errors. Conversely, the reranker demonstrates high reliability when selecting the RAG path, resulting in substantially fewer false positives.

Table 5.

Routing strategy accuracy comparison.

Figure 5.

ROC curve for reranker routing (Type A vs. Type B).

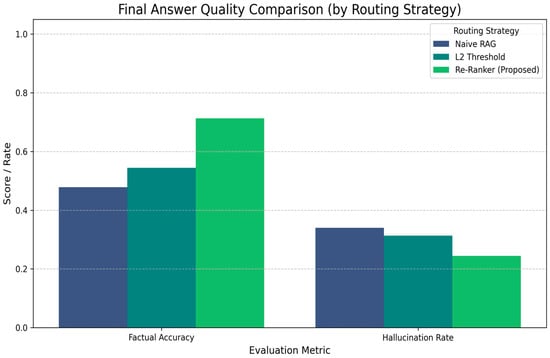

Final Answer Quality

The true impact of routing was assessed through manual annotation of the final answer quality. Table 3 and Figure 6 present the results. The proposed (reranker) system demonstrates clear superiority, achieving the highest factual accuracy (71.3%) and, most importantly, the lowest hallucination rate (24.4%). This validates RQ2, confirming that the reranker’s high-precision routing effectively minimizes context contamination and prevents the LLM from hallucinating, even though its routing recall (Table 2) is lower than that of the L2 method. Naive RAG, which always forces context, performed worst, exhibiting the lowest accuracy (47.9%) and the highest hallucination rate (34.0%).

Figure 6.

Final answer quality comparison by routing strategy (Darker bars represent Baseline 1 and 2; the green bar represents the proposed BioChat system).

As shown in Figure 6, the reranker displayed strong discriminative capability in distinguishing Type A and Type B queries (AUC = 0.93). The selected operating point (Threshold = 0.02, red marker) lies near the knee of the curve, providing the optimal balance between recall and precision.

The results in Table 6 are definitive. The proposed (reranker) strategy achieved the highest factual accuracy (71.3%), significantly outperforming L2 Threshold (54.5%) and Naive RAG (47.9%). These findings indicate that precise query routing (high precision) contributes more to final answer accuracy than routing a larger number of queries (high recall). Most importantly, the reranker strategy yielded the lowest hallucination rate (24.4%), representing a 9.6 percentage point reduction compared to Naive RAG (34.0%) and a clear improvement over L2 Threshold (31.4%). This reduction (vs. Naive RAG) directly demonstrates that the reranker, by filtering out irrelevant context (false positives) and properly managing fallback queries, is a highly effective mechanism for mitigating LLM hallucination, thereby validating RQ2.

Table 6.

Final answer quality by routing strategy.

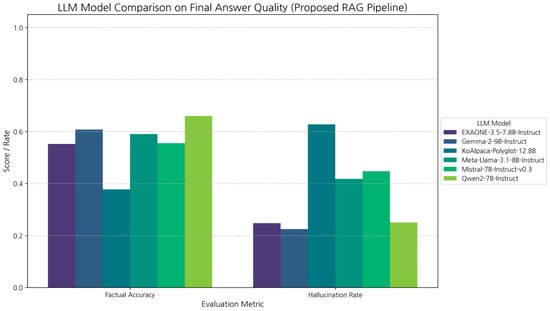

4.3. Experiment 3: LLM Model Comparison

Using the optimized proposed RAG pipeline (Reranker + Threshold = 0.02), we evaluated six different LLMs. All answers were manually annotated for factual accuracy and hallucination rate. Table 7 and Figure 7 show the results. Qwen2-7B-Instruct achieved the highest factual accuracy (66.0%), making it the most accurate model for this task. Gemma-2-9B-Instruct exhibited the lowest hallucination rate (22.5%), closely followed by EXAONE (24.8%) and Qwen2 (25.0%), demonstrating superior instruction adherence and safety. Llama 3.1 and Mistral 7B showed significantly higher hallucination rates (over 40%). Notably, KoAlpaca-Polyglot-12.8B performed worst on both metrics, indicating that model size or basic Korean tuning alone does not ensure strong RAG performance (addressing RQ3).

Table 7.

LLM comparison on final answer accuracy and hallucination rate.

Figure 7.

Final answer quality comparison by LLM model.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

Our experimental results collectively demonstrate the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed RAG pipeline. First, the embedding analysis confirmed that the use of a domain-specific encoder is crucial for specialized knowledge bases such as Korean biodiversity. It achieved a retrieval performance 4.5–5× higher than that of a general-purpose model, emphasizing that language- and domain-adapted embeddings [31,32] significantly enhance the quality of retrieved contexts. Second, the proposed reranker-based routing mechanism effectively serves as a safeguard against hallucination. By prioritizing precision (95.6%), it successfully filtered out irrelevant contexts before reaching the generator, resulting in the lowest hallucination rate (24.4%) and the highest factual accuracy (71.3%)—representing a +23.4-point improvement over the Naive RAG baseline. This finding validates the importance of precision-oriented routing for enhancing system reliability. Furthermore, the LLM comparison revealed that the generator is not merely an interchangeable component; despite operating under the same RAG pipeline, factual accuracy and hallucination behavior varied substantially across models. Qwen2-7B achieved the highest factual accuracy (66.0%), whereas Gemma-2-9B and EXAONE-3.5-7.8B excelled in instruction adherence [33,34] and safety, with notably low-hallucination rates. In contrast, Llama-3.1-8B and Mistral-7B often ignored the retrieved context and injected prior (sometimes incorrect) knowledge, indicating that alignment and safety tuning [35,36,37] are more critical than model size (as illustrated by the failure of KoAlpaca-12.8B).

Qualitative observations further corroborate these findings. When the reranker threshold was too low (e.g., query A_001, “Asplenium varians Wall. ex Hook. & Grev.”), all models were routed to fallback and produced fully hallucinated answers. In contrast, for general questions such as “What is the capital city of the Republic of Korea?,” all models correctly answered “Seoul” through appropriate fallback routing. These patterns highlight that model behavior under RAG depends not only on architecture but also on the interplay among embedding quality, routing precision, and generator alignment—together forming the foundation of a reliable, low-hallucination RAG system.

5.2. Implications and Contributions

This study offers academic and practical contributions to the field of domain-specific, reliability-oriented RAG systems [38]. From an academic perspective, we quantitatively isolate the effects of individual RAG components—embedding, routing, and generation—on retrieval accuracy and hallucination mitigation. In particular, we propose a systematic approach to routing threshold calibration based on reranker score distribution analysis, providing a replicable method for optimizing routing precision. In addition, this work establishes a benchmark that evaluates six state-of-the-art LLMs on a manually annotated Korean RAG dataset (Table 7), offering empirical evidence that instruction adherence and safety alignment are more critical than model size when selecting generator models for reliable RAG applications.

From a practical standpoint, we implement BioChat, a high-fidelity RAG prototype (Figure 2) built upon verified biodiversity data curated by the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR). The system demonstrates how domain-specific pipelines can achieve both factual accuracy and operational reliability in real-world biodiversity information retrieval. By effectively minimizing hallucinations, BioChat provides trustworthy, context-grounded responses that support environmental education and scientifically informed conservation decision-making.

From a sustainability perspective, this study further illustrates how domain-specific AI systems can function as reliable intermediaries between large-scale biodiversity databases and diverse end users, including educators, citizen scientists, and policy practitioners. By grounding all biodiversity-related responses in authoritative national data sources, BioChat contributes to sustainable biodiversity knowledge management, reduces barriers to ecological information access, and promotes environmental literacy while maintaining scientific integrity.

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

This study has several limitations. (1) The 400-item Q & A dataset, although manually annotated, is small relative to the 25,593-species knowledge base, with annotation carrying inherent subjectivity. (2) The knowledge base remains static. Although a feedback mechanism was designed (Section 3.1.3), a dynamic update pipeline for taxonomic changes was not implemented. (3) The static RERANK_THRESHOLD (0.02) led to false negatives; therefore, a dynamic, query-dependent threshold could be explored, utilizing techniques such as entropy-based uncertainty estimation or calibration layers to adaptively set cutoffs per query [39]. (4) Hardware constraints limited our LLM comparison to 4-bit quantized small-to-medium-sized LLMs (7–12.8 B). The performance of larger or nonquantized models was not assessed. However, the proposed BioChat architecture is designed as a modular blueprint, allowing for seamless scaling to larger infrastructures (e.g., multi-GPU setups or cloud-based deployment) in future implementations. Future work should focus on the following: (1) implementing the human-in-the-loop feedback pipeline for dynamic updates; (2) conducting in-depth comparisons of this RAG system versus fine-tuning the LLM directly on the NIBR dataset [40]; (3) exploring a RAG–fine-tuning hybrid approach using high-quality RAG Q & A pairs as training data [41]; and (4) expanding the system to a multimodal RAG framework [42] capable of identifying species from user-uploaded images.

6. Conclusions

This study designed, implemented, and systematically evaluated BioChat, a high-fidelity RAG–QA system for verified biodiversity data, focusing on mitigating LLM hallucinations. We demonstrated that each component of the RAG pipeline is critical for reliability. First, we confirmed the essence of a domain-specific embedding model, improving retrieval MRR by 4.6× over a general-purpose model (RQ1). Second, the proposed reranker-based routing mechanism (proposed) was validated to be a highly effective strategy for hallucination control. By optimizing the routing threshold based on score distribution analysis, this approach achieved the highest factual accuracy (71.3%) and the lowest hallucination rate. Among the various LLMs examined, Gemma-2-9B achieved the best hallucination control (22.5%), demonstrating that model size is less important than instruction-following capability. This research confirms that a carefully optimized pipeline, combining specialized embeddings, high-precision reranker routing, and a generator LLM with strong instruction adherence, is essential for developing reliable, domain-specific QA systems. We also provide a reproducible methodology and benchmark for future advancements in this area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-S.J. and Y.-S.H.; methodology, D.-S.J.; software, D.-S.J.; validation, D.-S.J., J.-S.Y. and H.-B.J.; formal analysis, D.-S.J.; investigation, D.-S.J.; data curation, J.-S.Y.; biological data review, H.-B.J.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-S.J.; writing—review and editing, Y.-S.H.; visualization, D.-S.J.; supervision, H.-B.J. and Y.-S.H.; project administration, Y.-S.H.; funding acquisition, H.-B.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR), Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment, grant number NIBR202504102. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was also funded by the NIBR.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were derived from public datasets provided by the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR), Ministry of Climate, Environment and Energy, Republic of Korea, and are openly available at the following website: http://species.nibr.go.kr (accessed on 15 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the administrative and technical staff of the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR) for their technical assistance and administrative support during the implementation of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| Bi-Encoder | Bidirectional encoder |

| BnB | Bits and bytes quantization |

| CE | Cross-Encoder |

| ChromaDB | Chroma Database |

| GBIF | Global Biodiversity Information Facility |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| k-NN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LLM | Large language model |

| MRR | Mean reciprocal rank |

| NIBR | National Institute of Biological Resources |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| QA | Question answering |

| Q&A | Question–Answer |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| Recall@K | Recall at K |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| RQ | Research question |

| SBERT | Sentence-BERT |

| UI | User interface |

Appendix A

- Query Templates and Example Questions

The BioChat system used two distinct query types for evaluation: Type A (RAG-based) and Type B (Fallback/general knowledge).

- Type A template (RAG):

- System: “You are a biodiversity expert AI assistant using verified NIBR data.”

- User: “{{question}}”

- Type B template (Fallback):

- System: “You are a general-purpose assistant.”

- User: “{{question}}”

- Example Type A queries (RAG):

- “What is the scientific name of the Suwon tree frog?”

- “Where is Drosera rotundifolia distributed in Korea?”

- “Which species of genus Quercus are endemic to Jeju Island?”

- Example Type B queries (Fallback):

- “Who proposed the theory of evolution?”

- “What is the average temperature of the Amazon rainforest?”

The full set of 400 evaluation queries is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Appendix B

- Annotation Protocol and Evaluation Criteria

Two biodiversity experts annotated all model-generated answers using a standardized guideline. Each response was assessed by two binary metrics:

Table A1.

Evaluation criteria used for manual annotation.

Table A1.

Evaluation criteria used for manual annotation.

| LLM Model | Definition | Criteria for “1” (Positive) | Criteria for “0” (Negative) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factual Accuracy | Whether the answer is factually correct and grounded in context | Consistent with ground truth or NIBR data | Incorrect or unverifiable |

| Hallucination | Whether the answer contains fabricated or unsupported content | Contains any non-grounded statement | Fully grounded or empty |

Inter-annotator agreement reached Cohen’s κ = 0.87, confirming high annotation consistency. The full annotation dataset (400 queries × 6 models) is not included due to size constraints but can be made available upon reasonable request.

References

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Smith, G.S.; Liu, Z.; Fung, P. Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.-T.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, H. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2024, 13, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M. REALM: Retrieval-Augmented Language Model Pre-training. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML’20), Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 3887–3898. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, J. Hallucination Mitigation for Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models: A Review. Mathematics 2025, 13, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstätter, S.; Lin, S.; Yang, J.-H.; Khattab, O.; Mitra, B.; Hanbury, A. Efficiently Teaching an Effective Dense Retriever with Balanced Topic Aware Sampling. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval SIGIR ‘21, Virtual Event, 11–15 July 2021; pp. 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Thessen, A.E.; Cui, H.; Mozzherin, D. Applications of Natural Language Processing in Biodiversity Science. Adv. Bioinform. 2012, 2012, 391574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D.J.; Egloff, W.; Agosti, D.; Eades, D.; Haskins, N.; Hyam, R.; Mozzherin, D.; Shorthouse, D.P.; Thessen, A. Challenges with Using Names to Link Digital Biodiversity Information. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, A.; Antunes Carvalho, F.; Vergara, D.; Calvente, A.; Baez-Lizarazo, M.R.; Cabral, A.; Coelho, J.F.R.; Colli-Silva, M.; Fantinati, M.R.; Fernandes, M.F.; et al. No One-Size-Fits-All Solution to Clean GBIF. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language Models Are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. OpenAI Technical Report. 2019. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/better-language-models/language_models_are_unsupervised_multitask_learners.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Nogueira, R.; Cho, K. Passage Re-Ranking with BERT. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Intelligent Information Processing and Natural Language Generation, Santiago de Compopstela, Spain, 7 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Ping, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; You, J.; Zhang, C.; Shoeybi, M.; Catanzaro, B. RankRAG: Unifying Context Ranking with Retrieval-Augmented Generation in LLMs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 121156–121184. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Douze, M.; Jégou, H. Billion-Scale Similarity Search with FAISS. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2021, 7, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Ma, R.; Wang, Z.; Song, J. A Comprehensive Survey on Vector Databases. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2024, 17, 4116–4129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Shao, Z.; Ma, Y.; Dai, H.; Chen, B.; Mao, L.; Lei, C.; Ding, Y.; Li, H. InfoGain-RAG: Boosting Retrieval-Augmented Generation through Document Information Gain-based Reranking and Filtering. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Suzhou, China, 4–9 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.F.; Lin, K.; Hewitt, J.; Paranjape, A.; Bevilacqua, M.; Petroni, F.; Liang, P. Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 12, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmers, T.; Lewis, M.; Shleifer, S.; Zettlemoyer, L. LLM.int8(): 8-bit Matrix Multiplication for Transformers at Scale. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. 2023, 35, 30318–30332. [Google Scholar]

- Gemma Team; Riviere, M.; Pathak, S.; Sessa, P.G.; Hardin, C.; Bhupatiraju, S.; Hussenot, L.; Mesnard, T.; Shahriari, B.; Ramé, A.; et al. Gemma 2: Improving Open Language Models at a Practical Size. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Keshwam, A.; Faulkner, A.; Holt, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Yang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Zhou, C.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen2 Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.10671. [Google Scholar]

- Saad-Falcon, J.; Finlayson, M.G.; Saggere, A.; Khattab, O.; Potts, C.; Zaharia, M. ARES: An Automated Evaluation Framework for Retrieval-Augmented Generation Systems. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 33965–33979. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsakal, O.; Akinci, T.Ç. Creating Large Language Model Applications Utilizing LangChain: A Primer on Developing LLM Apps Fast. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Engineering and Natural Sciences, Konya, Turkey, 10–12 July 2023; pp. 1050–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Shin, Y. Using Multiple Monolingual Models for Efficiently Embedding Korean and English Conversational Sentences. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fureby, L. Domain Adaptation of Retrieval Systems from Unlabeled Corpora. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings Using Siamese BERT-Networks. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 3982–3992. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, N.; Reimers, N.; Rücklé, A.; Srivastava, A.; Gurevych, I. BEIR: A Heterogeneous Benchmark for Zero-shot Evaluation of Information Retrieval. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 25206–25222. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, N.; Reimers, N.; Daxenberger, J.; Gurevych, I. Augmented SBERT: Data Augmentation Method for Improv-ing Bi-Encoders for Pairwise Sentence Scoring Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 296–310. [Google Scholar]

- Karpukhin, V.; Oğuz, B.; Min, S.; Lewis, P.; Wu, L.; Edunov, S.; Chen, D.; Yih, W.-T. Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 2895–2907. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Zhao, V.Y.; Guu, K.; Yu, A.W.; Lester, B.; Du, N.; et al. Finetuned Language Models Are Zero-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2022, Virtual Event, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, P.; Xu, P.; Iyer, S.; Sun, J.; Mao, Y.; Ma, X.; Efrat, A.; Yu, P.; Yu, L.; et al. LIMA: Less Is More for Alignment. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 22165–22185. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, D.M.; Stiennon, N.; Brown, T.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Radford, A.; Amodei, D.; Christiano, P.; Irving, G. Fine-Tuning Language Models from Human Preferences. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.08593. [Google Scholar]

- Rafailov, R.; Sharma, A.; Mitchell, E.; Manning, C.D.; Ermon, S.; Finn, C. Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 53728–53741. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, R. Retrieval-Augmented Domain Adaptation via In-Context Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 7250–7264. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Yao, X.; Chen, D. SimCSE: Simple Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 16973–16985. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, J.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, O.; Levine, Y.; Dalmedigos, I.; Muhlgay, D.; Shashua, A.; Leyton-Brown, K.; Shoham, Y. In-Context Retrieval-Augmented Language Models. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 12, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunaga, M.; Aghajanyan, A.; Shi, W.; James, R.; Leskovec, J.; Liang, P.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Yih, W. Retrieval-Augmented Multimodal Language Modeling. Proc. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. (ICML) 2023, 202, 39755–39769. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.