Abstract

Conventional urea nitrogen (N) fertilizers are characterized by low use efficiency, resulting in substantial economic losses and environmental degradation. To address this issue, we developed a novel carbon-based stabilized coated urea by incorporating biochar, the urease inhibitor NBPT, and the nitrification inhibitor DCD through a low-energy in situ coating process. This study evaluated the effects of this fertilizer on N transformation and loss via soil column leaching and ammonia volatilization experiments, as well as its impact on choy sum (Brassica chinensis L.) yield, N use efficiency (NUE), and product quality under field conditions. Results indicated that coatings containing both NBPT and DCD (specifically, formulations with 0.5%NBPT + 1.0%DCD, and 1.0%NBPT + 1.5%DCD) significantly reduced cumulative ammonium-N leaching by 41.5–53.8% and nitrate-N leaching by 45.3–59.4% compared to conventional urea. All coated treatments suppressed ammonia volatilization by over 10%, with the highest inhibition (26.92%) observed in the treatment with 1.0%NBPT + 1.5%DCD. The synergistic coating also modulated key soil enzyme activities involved in N cycling. Field trials demonstrated that the formulations with 0.5%NBPT + 1.0%DCD and 0.5%NBPT + 1.5%DCD increased choy sum yield by 56.1% and 58.1%, respectively, while significantly improving NUE and agronomic efficiency. Moreover, these treatments enhanced vegetable quality by reducing nitrate content and increasing vitamin C and soluble sugar concentrations. In conclusion, this carbon-based stabilized coated urea, which integrates biochar with NBPT and DCD, represents a promising strategy for minimizing N losses, improving NUE, and advancing sustainable vegetable production.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is an essential component of proteins, genetic material, chlorophyll, and other critical organic compounds in plants [1,2]. As the primary N source in crop production, N fertilizer directly influences crop uptake and utilization, playing a vital role in enhancing agricultural productivity and ensuring global food security [3]. However, the pursuit of high yields has often led to excessive and imprecise N application, resulting in substantial N losses via leaching and volatilization [4,5]. These losses contribute to severe environmental issues, including water eutrophication, soil acidification, and greenhouse gas emissions, while concurrently reducing N use efficiency (NUE) [6,7,8].

Temperature and moisture are key factors regulating microbial activity, thereby influencing N mineralization and nitrification rates [9]. Warmer and moist soils typically accelerate these processes, whereas colder or drier conditions suppress them [10,11]. High rainfall increases leaching losses of soluble N, such as nitrate, while warm and waterlogged soils promote denitrification, converting valuable N into gaseous forms lost to the atmosphere [12,13]. Southern China experiences a tropical and subtropical climate, supporting high multiple cropping indices and substantial fertilizer inputs. Concurrently, high temperature and humidity accelerate nutrient leaching, mineralization, and organic matter decomposition [9,14]. Therefore, innovations in fertilizer products and optimization of fertilization practices are essential to ensure grain production and quality, meet demands for green and safe agricultural products, and promote sustainable agricultural development and ecological health.

In this context, choy sum (Brassica chinensis L.) was selected as the model crop for this study. As a fast-growing leafy vegetable with a high N demand and short growth cycle (typically 30–40 days), choy sum is highly sensitive to N availability and management practices, making it an excellent indicator crop for assessing NUE and loss dynamics. Moreover, it holds significant economic and dietary importance across Southern China, where it is intensively cultivated in sequential cropping systems. Its tendency to accumulate nitrate in edible tissues also makes it a relevant model for evaluating the impact of fertilization strategies on vegetable quality and food safety. Thus, choy sum provides a robust and agronomically meaningful system to test the efficacy of our novel coated urea under realistic production conditions.

Biochar, urease inhibitors, and nitrification inhibitors can effectively reduce N fertilizer loss and enhance NUE to varying degrees [15,16,17]. Biochar possesses a stable structure, high specific surface area, a developed pore network, and high cation exchange capacity. Its application improves soil aggregation, water retention, and microbial activity, making it an environmentally friendly soil amendment [18]. Studies show that biochar can adsorb both ammonium-N and nitrate-N, reducing nutrient leaching and imparting slow-release and N-fixing properties to fertilizers [19,20,21]. Consequently, biochar is increasingly used in slow-release fertilizer development. Urease inhibitors reduce ammonia volatilization by suppressing urease activity and delaying urea hydrolysis, thereby directly reducing N2O and NO emissions and nitrate leaching [22,23,24]. Nitrification inhibitors impede the conversion of ammonium-N into nitrate-N by inhibiting key enzymatic steps, directly reducing N2O and NO emissions [25,26,27]. Combined application of these inhibitors with fertilizers can enhance NUE, boost crop yields, and mitigate environmental risks [28]. An incubation study in yellow clayey soil demonstrated that urease inhibitors could reduce the peak ammonia volatilization rate by 35.0% [29]. Nitrification inhibitors and combined inhibitors (urease/nitrification) decreased nitrate-N leaching by 15.9% and 37.5%, and N2O emissions by 17.2% and 34.5%, respectively [30,31]. Field experiments indicate that urease/nitrification inhibitors can suppress soil urease activity by 8.2% to 40.1%, while enhancing catalase, phosphatase, and sucrase activities and increasing soil organic matter [32,33]. These inhibitors also improve crop yields and promote N, phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) uptake [34]. Current research on biochar-based fertilizers primarily focuses on combining biochar with other coating materials [35,36] or granulating biochar with inorganic fertilizers [37]. However, studies on the combined application of biochar coatings with inhibitors remain limited. Moreover, studies on the synergistic integration of biochar with both urease and nitrification inhibitors in a single coated urea system remain scarce. This study aims to bridge this gap by developing and evaluating a novel carbon-based stabilized coated urea that synergistically combines biochar, NBPT, and DCD.

To bridge this gap, this study innovatively integrated biochar, NBPT, and DCD with a modified starch binder to develop a carbon-based stabilized coated urea via a low-energy in situ coating process. The specific objectives were to (1) evaluate the effects of this novel fertilizer on N leaching and ammonia volatilization; (2) investigate its impacts on key soil enzyme activities governing the N cycle; and (3) assess its agronomic performance in terms of choy sum yield, NUE, and product quality. This research aims to provide a scientific basis for the application of advanced, eco-friendly fertilizers that support the goals of sustainable agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Preparation of Carbon-Based Stabilized Coated Urea

Biochar was produced from peanut shells pyrolyzed at 400 °C for 2 h under anoxic conditions, followed by treatment with 1 mol L−1 KOH, grinding, and sieving to <100 mesh. The resulting biochar was characterized for key properties relevant to nutrient retention and soil interaction: it had an alkaline pH (9.8 ± 0.2, measured in a 1:10 water suspension), an ash content of 18.5 ± 1.1%, and a carbon content of 72.4 ± 2.1% with low H/C (0.46) and O/C (0.055) molar ratios, indicating a relatively stable, carbon-rich structure. The specific surface area was 315 ± 15 m2 g−1, with a total pore volume of 0.21 ± 0.02 cm3 g−1 and an average pore width of 3.2 nm, reflecting a well-developed microporous structure. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) was 45.2 ± 3.8 cmol(+) kg−1. Large granular urea (N 46.0%), controlled-release fertilizer (CFS), and slow-release fertilizer (SFS) were supplied by China BlueChemical Ltd. (Beijing, China). The inhibitors NBPT and DCD were provided by Shanghai Maclin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Soil (lateritic red earths, Chinese Soil Taxonomy) samples (0–20 cm depth) were collected from a summer maize field at the experimental farm of Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering (113°16′ E, 23°6′ N). After air-drying, the soil was sieved (2 mm) to remove stones, plant roots, and other extraneous materials. Basic soil physical and chemical properties were: organic matter 15.11 g kg−1, total N 1.25 g kg−1, alkaline-hydrolysable N 93.74 mg kg−1, available P 11.02 mg kg−1, available K 87.25 mg kg−1, nitrate-N 28.17 mg kg−1, ammonium-N 22.51 mg kg−1, and pH 5.02.

Six types of carbon-based stabilized coated urea were prepared by coating large granular urea (2.5–3.5 mm) with biochar (by mass of urea) using a BYC-400 coating machine (Shenzhen Leiyue Mechanical Equipment CO., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). Formulations were: Bio1 (biochar only), Bio2 (0.5% NBPT), Bio3 (1.0% DCD), Bio4 (0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD), Bio5 (0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD), and Bio6 (1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD). Dosages of NBPT and DCD were selected based on preliminary trials and literature reports [38,39] indicating effective inhibition within these ranges while avoiding phytotoxicity. The resulting coated granules had a coating thickness of 0.2–0.4 mm and a total nitrogen content of 42–44%. Preliminary dissolution tests in water indicated a sustained urea release profile over 7–10 days.

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Soil Column Leaching Experiment

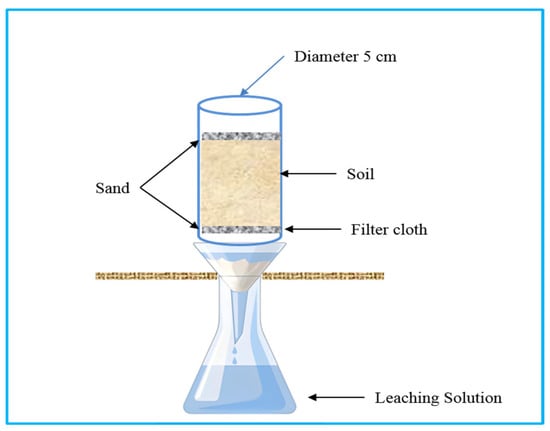

A leaching experiment was conducted at an N application rate of 600 mg kg−1 soil (300 mg per column). The rate corresponds to ~300 kg N ha−1, a typical high-input scenario for intensive vegetable production in Southern China, used here to accentuate leaching and volatilization losses for clearer treatment differentiation. The treatments were applied: no urea (CK), common urea (Urea), Bio1–Bio6, CFS, and SFS, each with three replicates. PVC columns (5 cm diameter × 50 cm height) were sealed at the bottom with a 0.75 mm mesh and layered with 25 g of sand (Figure 1). The lower section contained 250 g air-dried soil (bulk density 1.3 g cm−3), simulating the plough layer. Each soil (adopt the lateritic red earths in Section 2.1) layer (250 g) was packed to a depth of approximately 10 cm, achieving a bulk density of 1.3 g cm−3, which simulates typical field conditions in the region. The upper section contained 250 g of soil mixed with fertilizer. Another 25 g of river sand was added on top to minimize disturbance. Before fertilizer application, all columns were pre-leached with 100 mL of deionized water and allowed to drain for 24 h to remove readily soluble nitrogen and establish a consistent initial soil moisture condition. This step also helped to stabilize the soil structure and minimize the impact of initial nutrient variability. On day 1, 190 mL of deionized water was added for saturation, and the 24 h leachate was collected. The top was covered with perforated film. This initial 190 mL event, combined with the subsequent leaching volumes, was designed to simulate a series of rainfall events. Each 50 mL leaching event applied on days 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14 corresponds to approximately 25 mm of rainfall, based on the cross-sectional area of the column (19.6 cm2). This intensity is representative of moderate to heavy rainfall events common in Southern China during the vegetable growing season. Between leaching events, the columns were maintained in a constant-temperature incubator at 25 ± 1 °C. The perforated film covers minimized evaporation while allowing gas exchange, and no additional water was added, allowing the soil to undergo natural wetting-drying cycles between scheduled leaching events. On days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14, 50 mL of deionized water was applied for leaching. Each leachate was diluted to 100 mL and analyzed for total N, urea-N, nitrate-N, and ammonium-N.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the soil column eluvial device.

2.2.2. Ammonia Volatilization Inhibition Experiment

The experiment used the same ten treatments as above, with three replicates. For each, 500 g air-dried soil (2 mm sieved) was placed in a beaker. The amount of N fertilizer applied was consistent with that in the soil column leaching experiment. Soil moisture was adjusted to 70~75% field capacity using deionized water. A small beaker containing 10 mL of 2% boric acid indicator solution was placed inside to capture volatilized ammonia. Containers were incubated at 25 °C. On days 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 25, and 31, the boric acid was collected, and absorbed ammonia quantified by titration with 0.1 mol L−1 1/2H2SO4; the solution was then replenished.

2.2.3. Field Experiment

A field experiment was conducted to evaluate the agronomic performance of the carbon-based stabilized coated urea (formulations Bio1–Bio6, prepared as described in Section 2.1). The experiment was arranged in a randomized complete block design with three replicates. Each plot measured 2 m × 3 m. Choy sum (Brassica chinensis L.) seedlings at the four-leaf stage were transplanted at a spacing of 20 cm × 20 cm. Nitrogen was applied at a rate of 180 kg N ha−1, with 60% as basal fertilizer and 40% top-dressed at the rosette stage. Phosphorus (P2O5) and potassium (K2O) were uniformly applied at 90 kg ha−1 and 120 kg ha−1, respectively, as basal fertilizers. The field was located at the experimental farm of Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering (113°16′ E, 23°6′ N). Soil samples (0–20 cm depth) collected before planting had the following properties: organic matter 30.9 g kg−1, total N 1.8 g kg−1, alkaline-hydrolyzable N 130.6 mg kg−1, available P 116.1 mg kg−1, available K 213.4 mg kg−1, and pH 6.95. Note that the soil used in the field trial differs from that in the leaching experiment, reflecting typical soil variability across vegetable production areas in Southern China. This design enhances the practical relevance of our findings.

2.3. Sampling and Chemical Analysis

At 21 days and 42 days (harvest) after planting, soil samples from the 0–20 cm depth were collected from choy sum rows using a stainless-steel soil auger for nitrate-N, ammonium-N, and enzyme activity analysis. Ten plants per plot were randomly sampled. Fresh samples were analyzed for vitamin C, soluble sugar, and nitrate; the remaining samples were oven-dried (105 °C, then 65 °C to constant weight) and ground for total N determination. All three enzymes were measured using kits from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The determination of soil urease activity is based on using urea as the substrate, and the indophenol blue colorimetric method is employed to measure the NH3-N produced through the hydrolysis of urea by urease. Soil nitrate reductase catalyzes the reduction of nitrate to nitrite. Under acidic conditions, the generated nitrite can quantitatively react with p-aminobenzene sulfonic acid and α-naphthylamine to form a red azo compound, which has a maximum absorption peak at 540 nm. The activity of nitrite reductase is determined by the ability of nitrite reductase to reduce NO2− to NO, thereby decreasing the amount of NO2− involved in the diazotization reaction in the sample and resulting in the formation of a purple-red compound. The change in absorbance at 540 nm can reflect the activity of nitrite reductase in the soil.

2.4. Calculation Formulas and Statistical Analysis

NUE (%) = (Aboveground N uptake in N treatment − Aboveground N uptake in CK)/N application rate × 100

Agronomic efficiency (kg kg−1) = (Yield in N treatment − Yield in CK)/N application rate

Data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2010. ANOVA was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) software. When the ANOVA results indicated significant treatment effects (p < 0.05), the means were separated through the application of the Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc test. Graphics were created with Origin 2018 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Influence on N Leaching

3.1.1. Urea-N

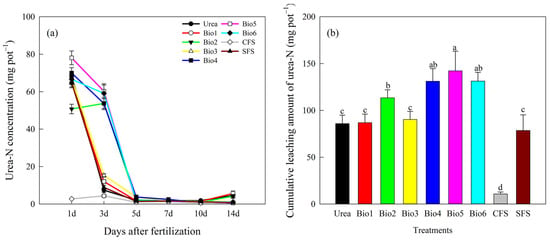

Urea-N leaching per event decreased with successive leaching events (Figure 2a). For Urea, Bio1, and Bio3, urea-N concentration dropped sharply after the second leaching. For NBPT-containing treatments (Bio2, Bio4, Bio5, and Bio6), a significant decrease began after the third leaching. In the first leaching, Bio5 showed the highest urea-N leaching (78.06 mg). In the second leaching, NBPT treatments (Bio2, Bio4, Bio5, and Bio6) leached 53.73, 53.72, 60.22, and 59.05 mg L−1, respectively, significantly higher than Urea. By the third leaching, Urea treatment leached only 2.09 mg L−1, similar to others. Cumulative urea-N leaching for Urea, Bio1, Bio2, Bio3, Bio4, Bio5, Bio6, CFS, and SFS was 85.81, 86.93, 113.43, 90.30, 131.15, 142.20, 131.38, 10.69, and 78.49 mg L−1, accounting for 46.3%, 45.7%, 51.6%, 44.6%, 59.7%, 61.0%, 63.6%, 23.2%, and 42.4% of total N leaching, respectively (Figure 2b). Bio2, Bio4, Bio5, and Bio6 showed significantly higher cumulative urea-N leaching than Urea; other treatments showed no significant difference. This initial increase in urea-N leaching reflects the delayed hydrolysis of urea due to NBPT inhibition, which temporarily retains nitrogen in the urea form—a mechanism that contributes to reduced subsequent ammonium and nitrate losses.

Figure 2.

Effect of carbon-based stabilized coated urea on urea-N (a) per event and (b) cumulative. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters on the bar indicate significant differences based on the LSD method (p < 0.05). Bio1, biochar only; Bio2, 0.5% NBPT; Bio3, 1.0% DCD; Bio4, 0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD; Bio5, 0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; Bio6, 1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; CFS, controlled-release fertilizer; and SFS, slow-release fertilizer.

3.1.2. Ammonium-N

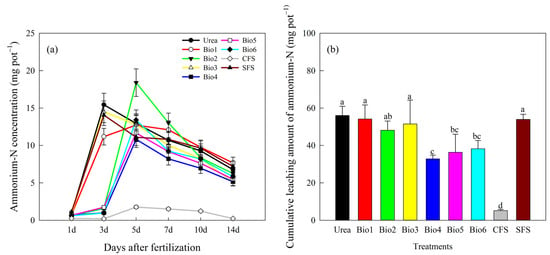

Ammonium-N leaching varied significantly among treatments (Figure 3a). Leaching patterns generally increased and then decreased. During the second leaching, Bio2, Bio4, Bio5, Bio6, and CFS showed stable leaching levels, while others increased sharply. No differences were observed in the first leaching. In the second leaching, ammonium-N concentrations in Bio2, Bio4, Bio5, Bio6, and CFS were 1.58, 0.99, 1.73, 0.96, and 0.20 mg L−1, respectively, lower than those of other treatments. Leaching gradually decreased in subsequent stages. Cumulative ammonium-N leaching after six cycles was 56.02 mg L−1 for Urea (30.20% of total N) (Figure 3b). For Bio1, Bio2, Bio3, Bio4, Bio5, Bio6, CFS, and SFS, cumulative leaching was 54.16, 48.15, 51.46, 32.78, 36.34, 38.23, 5.17, and 53.89 mg L−1, accounting for 28.5%, 21.9%, 25.4%, 14.9%, 15.6%, 18.5%, and 29.1% of total N, respectively. Bio4, Bio5, and Bio6 showed significantly lower leaching than Urea; no significant differences were found between Urea and Bio1, Bio2, Bio3, or SFS.

Figure 3.

Effect of carbon-based stabilized coated urea on ammonium-N leaching (a) per event and (b) cumulative. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters on the bar indicate significant differences based on the LSD method (p < 0.05). Bio1, biochar only; Bio2, 0.5% NBPT; Bio3, 1.0% DCD; Bio4, 0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD; Bio5, 0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; Bio6, 1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; CFS, controlled-release fertilizer; and SFS, slow-release fertilizer.

3.1.3. Nitrate-N

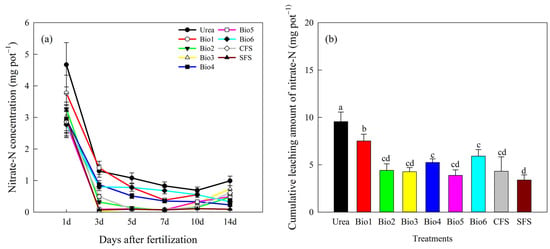

Nitrate-N leaching trends were consistent across treatments, decreasing most rapidly in the second leaching stage (Figure 4a). Throughout, nitrate-N levels in all treatments remained lower than in Urea. Cumulative nitrate-N leaching after six cycles for Urea, Bio1, Bio2, Bio3, Bio4, Bio5, Bio6, CFS, and SFS was 9.56, 7.51, 4.40, 4.26, 5.24, 3.88, 5.91, 4.31, and 3.39 mg L−1, accounting for 5.2%, 4.0%, 2.0%, 2.1%, 2.4%, 1.7%, 2.9%, 9.3%, and 1.8% of total N leaching, respectively (Figure 4b). All treatments showed significantly lower nitrate-N leaching than Urea.

Figure 4.

Effect of carbon-based stabilized coated urea on nitrate-N leaching (a) per event and (b) cumulative. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters on the bar indicate significant differences based on the LSD method (p < 0.05). Bio1, biochar only; Bio2, 0.5% NBPT; Bio3, 1.0% DCD; Bio4, 0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD; Bio5, 0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; Bio6, 1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; CFS, controlled-release fertilizer; and SFS, slow-release fertilizer.

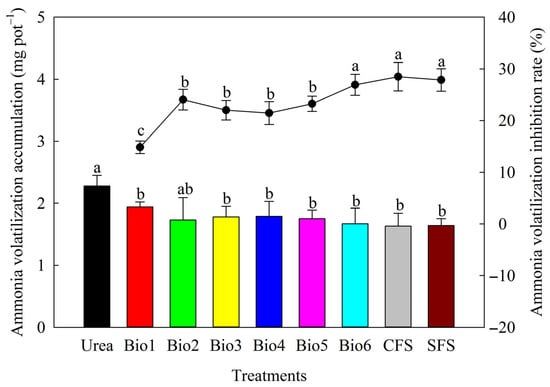

3.2. Influence on Ammonia Volatilization Loss

All carbon-based coated urea formulations reduced ammonia volatilization compared to Urea (Figure 5). Volatilization for Bio1–Bio6, CFS, and SFS was 1.94, 1.73, 1.78, 1.79, 1.75, 1.67, 1.63, and 1.64 mg, respectively. All carbon-based coated urea formulations reduced ammonia loss by >10%. Bio6 showed the highest inhibition rate (26.92%).

Figure 5.

Effect of carbon-based stabilized coated urea on ammonia volatilization accumulation and its inhibition rate. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters on the bar or line indicate significant differences based on the LSD method (p < 0.05). Bio1, biochar only; Bio2, 0.5% NBPT; Bio3, 1.0% DCD; Bio4, 0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD; Bio5, 0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; Bio6, 1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; CFS, controlled-release fertilizer; and SFS, slow-release fertilizer.

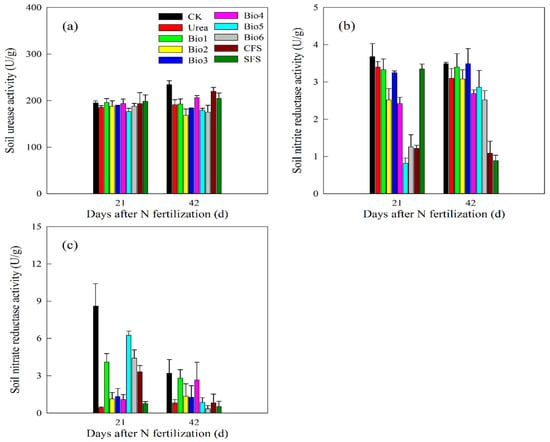

3.3. Influence on Soil Enzyme Activity

At 21 days, nitrite reductase activity in Bio2, Bio4, Bio5, and Bio6 decreased by 25.9%, 28.8%, 75.9%, and 62.9%, respectively, indicating effective nitrification inhibition (Figure 6b). Nitrate reductase activity was significantly enhanced in all coated fertilizer treatments at 21 days (Figure 6c). By 42 days, urease activity decreased in NBPT-containing treatments, confirming the sustained inhibitory effect.

Figure 6.

Effect of carbon-based stabilized coated urea on soil (a) urease; (b) nitrite; and (c) nitrate activities. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3). Bio1, biochar only; Bio2, 0.5% NBPT; Bio3, 1.0% DCD; Bio4, 0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD; Bio5, 0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; Bio6, 1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; CFS, controlled-release fertilizer; and SFS, slow-release fertilizer. The units of the three enzymes are uniformly expressed as U/g, representing the quantity of enzyme necessary to catalyze the conversion of 1 μmol of substrate per minute under optimal conditions (25 °C).

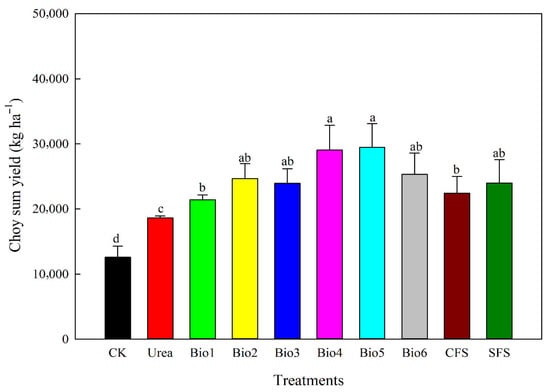

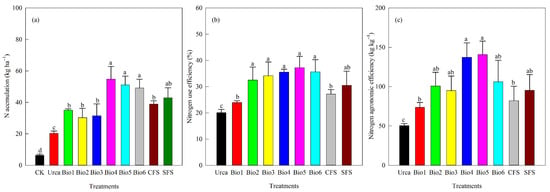

3.4. Choy Sum Yield, N Accumulation, and N Efficiency

Choy sum yield varied among treatments (Figure 7). Compared to Urea, carbon-based coated urea increased yield by 14.9–58.1%. Bio4 and Bio5 showed the highest increases (56.1% and 58.1%). No significant differences were found among Bio2, Bio3, and Bio6. All coated urea treatments significantly enhanced N accumulation compared to Urea (Figure 8a). N accumulation under Bio4, Bio5, and Bio6 was significantly higher than under Bio1, Bio2, and Bio3. Both NUE and agronomic efficiency were significantly improved in all coated urea treatments compared to Urea, though no significant differences were observed among the different coated urea formulations (Figure 8b,c).

Figure 7.

Effect of carbon-based stabilized coated urea on choy sum yield. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters on the bar indicate significant differences based on the LSD method (p < 0.05). Bio1, biochar only; Bio2, 0.5% NBPT; Bio3, 1.0% DCD; Bio4, 0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD; Bio5, 0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; Bio6, 1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; CFS, controlled-release fertilizer; and SFS, slow-release fertilizer.

Figure 8.

Effect of carbon-based stabilized coated urea on (a) N accumulation; (b) N use efficiency; and (c) agronomic efficiency. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters on the bar indicate significant differences based on the LSD method (p < 0.05). Bio1, biochar only; Bio2, 0.5% NBPT; Bio3, 1.0% DCD; Bio4, 0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD; Bio5, 0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; Bio6, 1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; CFS, controlled-release fertilizer; and SFS, slow-release fertilizer.

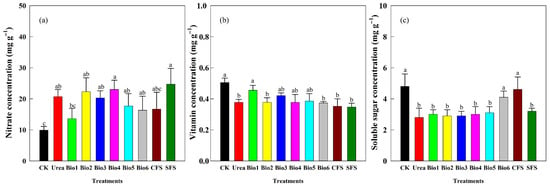

3.5. Choy Sum Quality

Nitrate, vitamin C, and soluble sugar concentrations were key quality indicators (Figure 9). Compared to CK, all N treatments increased nitrate concentration, with the lowest levels in Bio1, Bio5, and Bio6 (Figure 9a). Vitamin C concentration was highest in Bio1 (0.46 mg g−1); no significant difference was observed among Bio3, Bio4, and Bio5 (Figure 9b). Soluble sugar concentration was highest in Bio6 (4.1 mg g−1), significantly higher than other treatments and Urea (Figure 9c).

Figure 9.

Effect of carbon-based stabilized coated urea on (a) nitrate; (b) vitamin; and (c) soluble sugar concentrations of choy sum quality. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters on the bar indicate significant differences based on the LSD method (p < 0.05). Bio1, biochar only; Bio2, 0.5% NBPT; Bio3, 1.0% DCD; Bio4, 0.5% NBPT + 1.0% DCD; Bio5, 0.5% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; Bio6, 1.0% NBPT + 1.5% DCD; CFS, controlled-release fertilizer; and SFS, slow-release fertilizer.

4. Discussion

Urea is the primary N fertilizer in agriculture, yet only 30–60% of applied N is typically utilized by crops, with efficiency averaging ~40% in China [40]. This inefficiency leads to substantial economic and environmental costs. Coated urea can enable slow- or controlled-release, synchronizing N availability with crop demand and improving NUE [41,42]. However, high production costs limit widespread adoption [43]. Developing efficient N fertilizers is crucial for global food security and environmental sustainability [44]. This study successfully developed a novel carbon-based stabilized coated urea by synergistically combining biochar, NBPT, and DCD. Our results demonstrate that this coating technology effectively modulates soil N transformation, reduces N losses via leaching and volatilization, and enhances choy sum yield, NUE, and quality.

4.1. Modulation of N Leaching Dynamics

In the current study, the initial higher urea-N leaching in treatments containing NBPT (Bio2, Bio4, Bio5, Bio6) during the first and second leaching events is a direct consequence of the inhibitor’s intended function. NBPT effectively suppresses urease enzyme activity, thereby delaying the hydrolysis of urea to ammonium (NH4+) [23,28]. This delay resulted in urea persisting longer in the soil solution, making it more susceptible to leaching in the early stages following fertilizer application and irrigation [45]. While this initially increased urea-N loss, it indicates a slower-release mechanism, which is beneficial for aligning N availability with the plant’s longer-term nutrient uptake needs, potentially reducing the peak concentration of ammonium available for nitrification or volatilization. Importantly, the initially higher urea-N leaching in treatments containing NBPT should not be interpreted as an increased environmental risk. Urea itself is not a direct pollutant of primary concern for groundwater or aquatic ecosystems. The key environmental risk from nitrogen fertilizers stems from the conversion of urea to nitrate (NO3−), which is highly mobile and a major contributor to water eutrophication and groundwater contamination [46,47]. In our coated urea formulations, while NBPT delayed urea hydrolysis, the concomitant presence of DCD effectively inhibited the subsequent nitrification process—the biological oxidation of ammonium to nitrate [26]. This “double-locking” mechanism ensured that even though urea persisted longer, its rapid transformation into the highly leachable nitrate form was prevented. Therefore, the observed pattern reflects a strategic shift in the timing and form of N release, which successfully curtails the ultimate loss of the more environmentally detrimental nitrate species, thereby mitigating the overall environmental footprint of the fertilization practice [22,27].

The significant reduction in cumulative ammonium-N leaching in the combined inhibitor treatments (Bio4, Bio5, Bio6) underscores a critical synergistic effect. While NBPT delayed urea hydrolysis, DCD simultaneously inhibited the nitrification process, specifically the oxidation of ammonium to nitrate (NO3−) [26]. By slowing both hydrolysis and nitrification, these treatments maintained N in the ammonium form for a longer duration. Ammonium ions (NH4+) are positively charged and are more readily adsorbed onto the negatively charged exchange sites of soil particles and biochar, thereby reducing their mobility and leaching potential [19,21]. This “double-locking” mechanism—locking N in the urea form temporarily and then locking the resultant ammonium in the soil—proved highly effective in minimizing the total leaching loss of soluble N. Furthermore, the consistently lower nitrate-N leaching across all coated treatments, especially notable in Bio5, confirms the efficacy of DCD in inhibiting nitrification. Nitrate is highly mobile and is the primary form of N lost through leaching. The reduction in nitrate-N loss is environmentally significant, as it directly contributes to the mitigation of groundwater contamination and eutrophication [46,47]. The biochar component likely contributed to this reduction not only by adsorbing ammonium but also by providing a habitat for microbes that may immobilize N temporarily, thus enhancing the overall retention capacity of the soil [18,20].

4.2. Suppression of Ammonia Volatilization

All carbon-based coated urea formulations significantly reduced ammonia volatilization compared to conventional urea, with the highest inhibition rate (26.92%) observed in Bio6, which contained the highest dosage of NBPT (1.0%). This result unequivocally demonstrates the role of NBPT in mitigating gaseous N loss. By inhibiting urease, NBPT slows the rapid rise in soil pH around the urea granule that drives ammonia volatilization [48,49]. The fact that treatments with higher NBPT loads (Bio6) performed better than those with lower loads (Bio2) suggests a dose-dependent effect, highlighting the importance of optimizing inhibitor concentration for maximum efficacy [28]. The biochar coating may have provided a physical barrier, slowing the diffusion of urea and its hydrolysis products, thereby complementing the chemical inhibition by NBPT.

4.3. Responses of Soil Enzyme Activities and Implications for N Cycling

The soil enzyme activity data provide a mechanistic explanation for the observed N dynamics. The absence of significant differences in urease activity at 21 days, followed by a reduction in NBPT-containing treatments at 42 days, indicates that the inhibitory effect of NBPT may not be immediately apparent in measurements of potential enzyme activity but is more accurately reflected in its functional consequence—namely, the delayed hydrolysis of urea observed in the leaching experiment. The marked suppression of nitrite reductase activity in DCD-containing treatments (Bio3, Bio4, Bio5, and Bio6) at 21 days serves as a clear biochemical indicator of effective nitrification inhibition, given the enzyme’s role in a later stage of the nitrification pathway. The transient increase in nitrate reductase activity observed in coated treatments at 21 days is noteworthy. As this enzyme is involved in microbial and plant assimilation of nitrate, the observed enhancement may be attributed to the biochar component, which is known to enhance soil aeration and microbial habitat, potentially stimulating microbial activity and increasing demand for nitrate-N for biomass synthesis (i.e., immobilization), thereby reducing its leachability [35,50,51]. By harvest (42 days), as readily available N pools were depleted or transformed, enzyme activities across treatments converged, suggesting that the coatings primarily modulated early to mid-term N transformation processes. Furthermore, biochar may influence the release kinetics and longevity of NBPT and DCD through adsorption interactions. Biochar’s porous structure and high surface area can adsorb organic molecules, potentially modulating the availability of inhibitors in the soil solution. While this study did not directly measure inhibitor release rates, future research should investigate how biochar properties (e.g., pyrolysis temperature, surface chemistry) affect inhibitor stability, release dynamics, and ultimately their efficacy over time in different soil environments. Notably, the transient increase in nitrate reductase activity at 21 days, particularly pronounced in biochar-containing treatments, points towards a key mechanism for N retention. Nitrate reductase is involved in the assimilatory nitrate reduction pathway, where microorganisms convert nitrate into ammonium for incorporation into biomass. The biochar component, by improving soil aeration, porosity, and providing habitat, likely stimulated microbial activity and growth. This enhanced microbial demand for nitrate created a competitive sink, immobilizing nitrate-N and thus reducing its leaching potential. This shift towards microbial immobilization, facilitated by the coated fertilizers, effectively conserved N within the soil–plant system and underlies the concurrent improvements in crop N accumulation and NUE documented in our study.

4.4. Agronomic Performance: Yield, NUE, and Quality Enhancement

The superior agronomic performance of the coated urea, particularly Bio4 and Bio5, is the ultimate validation of their effectiveness. The yield increases of 56.1% and 58.1%, respectively, coupled with significantly higher N accumulation and NUE, can be directly attributed to the more efficient N supply strategy. By reducing losses through leaching and volatilization, a greater proportion of the applied N was conserved in the soil–plant system and made available for plant uptake over a more extended period. This synchronous release with crop demand is a hallmark of enhanced fertilizer efficiency [15]. Notably, although Bio6 (with the highest inhibitor load) also performed well, its yield was slightly lower than that of Bio4 and Bio5. This may suggest that excessive concentrations of NBPT and DCD could induce transient suppression of key soil microbial communities involved in N mineralization and nitrification, thereby subtly altering the timing and magnitude of plant-available N release [26,32]. Furthermore, an overly strong inhibition of nitrification might temporarily limit the supply of nitrate-N, which is a preferred N form for rapid vegetative growth in many crops, including choy sum [27]. This observation underscores the existence of an optimal inhibitor dosage window—where the synergy between delayed hydrolysis and nitrification inhibition maximizes N availability in synchrony with crop demand without disrupting essential soil biological functions [20,28]. Future studies incorporating soil microbial community analysis and real-time N flux monitoring could further elucidate this dose-dependent response.

The improvement in choy sum quality parameters is another significant benefit. The reduction in nitrate concentration in the edible parts of the plant (e.g., in Bio5 and Bio6) is particularly important for food safety, as high nitrate levels in vegetables can be harmful to human health, being associated with methemoglobinemia and potential carcinogenic nitrosamine formation [49,50]. From a regulatory perspective, maintaining low nitrate content is increasingly critical to meet stringent food safety standards for leafy vegetables in many markets [51]. The observed reduction in tissue nitrate is not merely an indicator of improved safety; it also likely reflects a more efficient and balanced nitrogen assimilation process. This reduction is likely due to the more controlled N release, preventing excessive nitrate accumulation in the plant tissues. By moderating the soil nitrate flux, our coated urea treatments may have reduced the passive, luxury uptake of nitrate by the plant, promoting instead a closer synchrony between N supply and demand, which is a hallmark of enhanced NUE [52,53]. The increases in vitamin C and soluble sugar content in certain treatments further indicate an improvement in nutritional quality, which may be related to better overall plant growth and metabolic efficiency under a more balanced N supply.

4.5. Evidence for Interactive Effects and Study Limitations

The superior performance of formulations containing both NBPT and DCD alongside biochar (Bio4, Bio5, Bio6) suggests a positive interaction among these components. For instance, the reduction in N losses and the improvement in yield and NUE for these combined treatments were consistently greater than what was observed with any single component (Bio1, Bio2, Bio3). This aligns with the proposed “double-locking” mechanism, where the sequential inhibition of urea hydrolysis and nitrification creates a complementary effect that is inherently interactive. While the current formulation-comparison approach provides strong indirect evidence for synergy, we acknowledge that a formal factorial experiment explicitly testing the main and interaction effects of biochar, NBPT, and DCD would offer the most rigorous statistical confirmation of their relationships. Such a design is a recommended focus for future research to precisely quantify the contribution of each component and their interactions. Nevertheless, the marked efficacy of the integrated coating demonstrated here underscores its practical potential for sustainable N management.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully developed a carbon-based stabilized coated urea using a low-energy coating process that synergistically integrates biochar, NBPT, and DCD. The formulation significantly reduces N losses via leaching and volatilization, improves NUE, and enhances the yield and quality of choy sum. This technology offers a practical and eco-friendly fertilization strategy for smallholder and commercial vegetable growers, with potential to reduce fertilizer input costs, minimize environmental pollution, and enhance crop quality—key goals for sustainable agricultural policies. This technology represents a promising strategy for advancing sustainable intensification in vegetable production systems, particularly in regions vulnerable to high N losses. Future research should focus on (1) optimizing the biochar-to-inhibitor ratio for different soil types and crop species, (2) evaluating the long-term effects of coated urea on soil microbial communities and carbon sequestration, and (3) conducting economic feasibility analyses under real farm conditions to assess scalability and farmer adoption.

Author Contributions

L.L.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft preparation. Y.T.: Writing—review and editing, Software, Methodology. H.L. (Huang Li): Writing—review and editing, Formal analysis. H.L. (Haili Lv): Investigation, Data curation. B.H.: Writing—review and editing. H.C.: Writing—review and editing, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. J.D.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported financially by the Key Technologies R&D Program of Guangdong Province (2023B0202080002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mulvaney, R.L.; Khan, S.A.; Ellsworth, T.R. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers deplete soil nitrogen: A global dilemma for sustainable cereal production. J. Environ. Qual. 2009, 38, 2295–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimkpa, C.O.; Fugice, J.; Singh, U.; Lewis, T.D. Development of fertilizers for enhanced nitrogen use efficiency—Trends and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 139113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, N.; Brym, Z.; Oyola, L.A.M.; Sharma, L.K. Nitrogen fertilization impact on hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) crop production: A review. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 1557–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebarth, B.J.; Drury, C.F.; Tremblay, N.; Cambouris, A.N. Opportunities for improved fertilizer nitrogen management in production of arable crops in eastern Canada: A review. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 89, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.A.; Ayyub, M.; Tariq, L.; Iltaf, J.; Asbat, A.; Bashir, I.; Umar, W. Nitrogen fertilizers and the future of sustainable agriculture: A deep dive into production, pollution, and mitigation measures. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 70, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Lin, W.F.; Chen, Y. Pollution problems of nitrogen fertilizer application in agriculture and countermeasures. Chin. J. Trop. Agric. 2003, 23, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ladha, J.K.; Pathak, H.; Krupnik, T.J.; Six, J.; van Kessel, C. Efficiency of fertilizer nitrogen in cereal production: Retrospects and prospects. Adv. Agron. 2005, 87, 85–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Ye, C.; Su, Y.W.; Peng, W.C.; Lu, R.; Liu, Y.X.; Huang, H.C.; He, X.H.; Yang, M.; Zhu, S.S. Soil Acidification caused by excessive application of nitrogen fertilizer aggravates soil-borne diseases: Evidence from literature review and field trials. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, B.; Slaton, N.; Norman, R.; Gbur, E.; Wilson, C. Nitrogen release from environmentally smart nitrogen fertilizer as influenced by soil series, temperature, moisture, and incubation method. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2011, 42, 1809–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.F.; Ji, H.F.; Wang, L.Y.; Zheng, X.L.; Xin, J.; Nai, H. Effects of various combinations of fertilizer, soil moisture, and temperature on nitrogen mineralization and soluble organic nitrogen in agricultural soil. Environ. Sci. 2018, 39, 4717–4726. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.Z.; Hu, Y.L.; Song, C.N.; Yu, Y.Z.; Jiao, Y. Interactive effects of soil moisture, nitrogen fertilizer, and temperature on the kinetic and thermodynamic properties of ammonia emissions from alkaline soil. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2023, 14, 101805. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, D.; Hannah, M.; Robertson, F.; Rifkin, P. A bayesian network for comparing dissolved nitrogen exports from high rainfall cropping in southeastern Australia. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.Y.; Ju, X.T.; Wei, Y.P.; Li, B.G.; Zhao, L.L.; Hu, K.L. Simulation of bromide and nitrate leaching under heavy rainfall and high-intensity irrigation rates in North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Larrard, T.; Poyet, S.; Pierre, M.; Benboudjema, F.; Le Bescop, P.; Colliat, J.B.; Torrenti, J.M. Modelling the influence of temperature on accelerated leaching in ammonium nitrate. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2012, 16, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.H.; Yuan, J.J.; Luo, J.F.; Lindsey, S.; Xiang, J.; Lin, Y.X.; Liu, D.Y.; Chen, Z.M.; Ding, W.X. Combined application of biochar with urease and nitrification inhibitors have synergistic effects on mitigating CH4 emissions in rice field: A three-year study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Huang, Y.X.; Song, X.; Deng, O.P.; Zhou, W.; Luo, L.; Tang, X.Y.; Zeng, J.; Chen, G.D.; Gao, X.S. Biological nitrification inhibitor co-application with urease inhibitor or biochar yield different synergistic interaction effects on NH3 volatilization, N leaching, and N use efficiency in a calcareous soil under rice cropping. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronska, M.; Kusmierz, S.; Walczak, J. Selected carbon and nitrogen compounds in a maize agroecosystem under the use of nitrogen mineral fertilizer, farmyard manure, urease, and nitrification inhibitors. Agriculture 2024, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Q.M.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.F.; Sun, M.; Liu, Z.X.; Chen, J.L. Effect of biochar application amount on the soil improvement and the growth of flue-cured tobacco. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 2016, 30, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, C.; Quilodrán, C.; Navia, R. Evaluation of biochar-plant extracts complexes on soil nitrogen dynamics. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2014, 8, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, A.I.; Xu, Y.H.; Shi, D.P.; Li, J.; Li, H.T.; El-Sappah, A.H.; Elrys, A.S.; Alharbi, S.A.; Zhou, C.J.; Wang, L.Q.; et al. Nitrogen transformation genes and ammonia emission from soil under biochar and urease inhibitor application. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 223, 105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Y.; Yang, J.Q.; Liu, W.Z.; Li, X.Q.; Zhang, W.Z.; Wang, A.J. Effects of alkaline biochar on nitrogen transformation with fertilizer in agricultural soil. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Cobena, A.; Sánchez-Martín, L.; García-Torres, L.; Vallejo, A. Gaseous emissions of N2O and NO and NO3− leaching from urea applied with urease and nitrification inhibitors to a maize (Zea mays) crop. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 149, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Purakayastha, T.J.; Pendall, E.; Dey, S.; Jain, N.; Kumar, S. Nitrification and urease inhibitors mitigate global warming potential and ammonia volatilization from urea in rice-wheat system in India: A field to lab experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atav, V.; Gürbüz, M.A.; Kayali, E.; Yalinkiliç, E. Optimizing nitrogen management in maize (Zea mays L.) using urease and nitrification inhibitors. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2025, 56, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosolem, C.A.; Ritz, K.; Cantarella, H.; Galdos, M.V.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Whalley, W.R.; Mooney, S.J. Enhanced plant rooting and crop system management for improved N use efficiency. Adv. Agron. 2017, 146, 205–239. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, F.; Liang, T.; Li, L.W.; Wang, J.J.; Chen, X.P.; Wang, X.Z. Impact of nitrification inhibitors on vegetable production yield, nitrogen fertilizer use efficiency and nitrous oxide emission reduction in China: Meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. 2022, 43, 5140–5148. [Google Scholar]

- Tufail, M.A.; Irfan, M.; Umar, W.; Wakeel, A.; Schmitz, R.A. Mediation of gaseous emissions and improving plant productivity by DCD and DMPP nitrification inhibitors: Meta-analysis of last three decades. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 64719–64735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.; Saggar, S.; Blennerhassett, J.D.; Singh, J. Effect of urease and nitrification inhibitors on N transformation, gaseous emissions of ammonia and nitrous oxide, pasture yield and N uptake in grazed pasture system. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, L.H.; Dai, F. Inhibition effect of inhibitors on nitrogen transformation affected by interaction of soil temperature and water content. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017, 33, 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, L.H.; Dong, C.H.; Jia, L. Effects of nitrogen fertilization combined with biochemical inhibitors on leaching characteristics of soil nitrogen in yellow clayey soil. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 1804–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, S.N.; Wang, L.; Lu, Y.L.; Bai, Y.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Jiang, H.; Wang, L.B. Study on the fate of fertilizer nitrogen during summer maize season based on high abundance of 15N under application of urease/nitrification inhibitors. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2024, 30, 1092–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, S.S.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ma, X.M.; Kong, Y.H. Effect of different nitrogen application measures on soil enzyme activities and nitrogen turnover in winter wheat cropland. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2020, 29, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.Q.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Ma, X.Y.; Zhu, S.J.; Zhao, T.L. Effects of a new nitrogen fertilizer synergist N-life II application on soil nitrogen supply and related enzyme activities in cotton fields. Cotton Sci. 2025, 37, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.X.; Xu, W.H.; Chen, X.G.; Li, Y.H.; Chi, S.L.; Li, T.; Feng, D.Y.; He, Z.M. Effects of slow-release fertilizer containing urease inhibitor and nitrification inhibitor on nutrients contents and enzymes activities in soil. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2019, 35, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L.; Yang, M.; Ba, C.; Yu, S.S.; Jiang, Y.F.; Zou, H.T.; Zhang, Y.L. Preparation and characterization of slow-release fertilizer encapsulated by biochar-based waterborne copolymers. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, D.H.H.; Tan, I.A.W.; Lim, L.L.P.; Hameed, B.H. Encapsulated biochar-based sustained release fertilizer for precision agriculture: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 127018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Q.; Luo, D.; Zhang, X.; Huang, R.; Cao, Y.J.; Liu, G.G.; Zhang, Y.S.; Wang, H. Biochar-based slow-release of fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: A mini review. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2022, 10, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, D.P.; Wu, Z.J.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Nie, Y.X. Effect of urease/nitrification inhibitors on transformation of urea-N in albicsoil. Plant Nutr. Fertil. Sci. 2011, 17, 646–650. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Guo, Y.J.; Zhang, L.J.; Li, B.W.; Liu, Q.; Han, J. Effects of DCD and DMPP on the nitrous oxide emissions and ammonia violation from greenhouse soil under different water contents. J. Hebei Agric. Univ. 2019, 42, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.X.; Sun, H.C.; Liu, L.T.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.J.; Li, A.C.; Bai, Z.Y.; Wang, G.Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Dong, H.Z.; et al. Optimizing crop yields while minimizing environmental impact through deep placement of nitrogen fertilizer. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, M.Y.; Sulaiman, S.A. Slow release coating remedy for nitrogen loss from conventional urea: A review. J. Control. Release 2016, 225, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riseh, R.S.; Vazvani, M.G.; Kennedy, J.F. The application of chitosan as a carrier for fertilizer: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 252, 126483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Q.F.; Jiang, S.; Chen, F.Y.; Li, Z.X.; Ma, L.T.; Song, Y.; Yu, X.J.; Chen, Y.X.; Liu, H.S.; Yu, L. Fabrication, evaluation methodologies and models of slow-release fertilizers: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Shivay, Y.S. Fertilizer nitrogen and global warming—A review. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 89, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motasim, A.M.; Samsuri, A.W.; Nabayi, A.; Akter, A.; Haque, M.A.; Sukor, A.S.A.; Adibah, A.M. Urea application in soil: Processes, losses, and alternatives—A review. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Zeng, L.H.; Qin, W.; Feng, J. Measures for reducing nitrate leaching in orchards: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.M.K.; Li, P.Y.; Fida, M. Groundwater nitrate pollution due to excessive use of N-fertilizers in rural areas of bangladesh: Pollution status, health risk, source contribution, and future impacts. Expo. Health 2024, 16, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, S.S.; Urrutia, O.; Martin, V.; Peristeropoulos, A.; Garcia-Mina, J.M. Efficiency of urease and nitrification inhibitors in reducing ammonia volatilization from diverse nitrogen fertilizers applied to different soil types and wheat straw mulching. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 1569–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlage, B.; Cook, R.L. Soil property and fertilizer additive effects on ammonia volatilization from urea. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2018, 82, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Xia, H.; Riaz, M.; Liu, B.; El-Desouki, Z.; Jiang, C.C. Various beneficial microorganisms colonizing on the surface of biochar primarily originated from the storage environment rather than soil environment. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 182, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qiu, Y.; Yi, F.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, Q.; Fu, X.; Yao, Z.; Dai, Z.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Biochar dose-dependent impacts on soil bacterial and fungal diversity across the globe. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incrocci, L.; Maggini, R.; Cei, T.; Carmassi, G.; Botrini, L.; Filippi, F.; Clemens, R.; Terrones, C.; Pardossi, A. Innovative Controlled-Release Polyurethane-Coated Urea Could Reduce N Leaching in Tomato Crop in Comparison to Conventional and Stabilized Fertilizers. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarpa, P.; Mikusová, D.; Antosovsky, J.; Kucera, M.; Ryant, P. Oil-Based Polymer Coatings on CAN Fertilizer in Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.) Nutrition. Plant 2021, 10, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.