Abstract

The health and operational continuity of emergency responders are fundamental pillars of sustainable and resilient disaster management systems. These personnel operate in high-risk environments, exposed to intense physical, environmental, and psychological stress. This makes it crucial to monitor their health to safeguard their well-being and performance. Traditional methods, which rely on intermittent, voice-based check-ins, are reactive and create a dangerous information gap regarding a responder’s real-time health and safety. To address this sustainability challenge, the convergence of the Internet of Things (IoT) and wearable biosensors presents a transformative opportunity to shift from reactive to proactive safety monitoring, enabling the continuous capture of high-resolution physiological and environmental data. However, realizing a field-deployable system is a complex “system-of-systems” challenge. This review contributes to the field of sustainable emergency management by analyzing the complete technological chain required to build such a solution, structured along the data workflow from acquisition to action. It examines: (1) foundational health sensing technologies for bioelectrical, biophysical, and biochemical signals; (2) powering strategies, including low-power design and self-powering systems via energy harvesting; (3) ad hoc communication networks (terrestrial, aerial, and space-based) essential for infrastructure-denied disaster zones; (4) data processing architectures, comparing edge, fog, and cloud computing for real-time analytics; and (5) visualization tools, such as augmented reality (AR) and heads-up displays (HUDs), for decision support. The review synthesizes these components by discussing their integrated application in scenarios like firefighting and urban search and rescue. It concludes that a robust system depends not on a single component but on the seamless integration of this entire technological chain, and highlights future research directions crucial for quantifying and maximizing its impact on sustainable development goals (SDGs 3, 9, and 11) related to health, sustainable cities, and resilient infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Emergency response operations, such as urban firefighting, earthquake search and rescue, and hazardous material containment, are inherently chaotic, dynamic, and dangerous environments [1,2]. The first responders who operate in these scenarios are the single most critical asset for saving lives and mitigating damage. Their sustained health and operational capacity are paramount. However, in executing their duties, these personnel are routinely exposed to a combination of extreme physical exertion, significant psychological stress, and severe environmental hazards, including high heat, structural instability, and toxic atmospheres [3,4]. The health and safety of these responders are of paramount importance. Unfortunately, the high-stress, high-load nature of their work leads to a significant risk of over-exertion, sudden medical events (such as cardiac arrest), and physical injuries [5]. A persistent challenge for incident command is maintaining real-time situational awareness of not only the evolving disaster but also the physiological and safety status of their personnel in the field [6].

Traditional monitoring methods, which often rely on intermittent, voice-based radio check-ins, are reactive rather than proactive. They provide low-fidelity, subjective information that is often delayed. This creates a critical information gap where a responder could become incapacitated, disoriented, or suffer a medical emergency, with the command center remaining unaware until precious minutes have passed [7]. Addressing this gap is thus a fundamental requirement for building more sustainable response systems. The convergence of miniaturized, low-cost biosensors, smart fabrics, and the Internet of Things (IoT) paradigm presents a transformative opportunity to address this challenge [8]. By equipping personnel with IoT-enabled wearable systems, a continuous, real-time stream of high-resolution physiological, psychological, and environmental data can be captured and transmitted [9]. This “connected responder” concept enables a shift from reactive to proactive safety monitoring, allowing for the early detection of heat stress, over-exertion, toxic gas exposure, and other life-threatening conditions [10,11].

However, the realization of a robust and reliable IoT-based monitoring system for emergency response is a complex “system-of-systems” challenge. It is not sufficient to simply develop a novel sensor. A complete, field-deployable solution must address a chain of interconnected challenges, from the sensor–skin interface to the final visualization of data in the command center. Any single point of failure in this chain can render the entire system ineffective. This review provides a comprehensive, end-to-end analysis of the technologies required to build such a system. The overarching aim is to synthesize how integrated technological solutions can directly enhance the sustainability and resilience of emergency response. It is structured to follow the flow of data from acquisition to action. To provide a comprehensive and reproducible overview of the field, a systematic literature search was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. We queried four major academic databases: Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and PubMed. The search period covered publications from 2015 to 2025, capturing the rapid evolution of IoT and wearable technologies.

The search logic was constructed based on the intersection of three key domains: (1) Technology (e.g., wearables, WBAN, AR), (2) Application Context (e.g., disaster response, firefighting), and (3) Target Population (e.g., first responders, rescue workers). The exact Boolean query strings employed for each database are provided in Section S1 in Supplementary File. This methodological framework underpins the subsequent ‘system-of-systems’ synthesis, structured from data acquisition to decision support. This work directly supports sustainable development goals (SDGs 3, 9, and 11) related to health, sustainable cities, and resilient infrastructure.

To clarify the position of this review within the current academic landscape, we performed a comparative analysis of representative recent surveys in related domains. While numerous studies have addressed specific layers of technology, few have adopted a holistic perspective. A detailed comparison of these prior works regarding their scope, coverage, and limitations is provided in Section S2 in Supplementary File. Unlike previous reviews that isolate specific technological layers, this article adopts an “End-to-End System of Systems” perspective. Our unique contribution lies in integrating the physical layer (sensors and energy) with the computing and communication layers to address the coupled challenges of field deployment, specifically analyzing how energy harvesting strategies dictate the feasibility of edge computing architectures in infrastructure-denied zones.

Section 2 reviews the foundational personnel health sensing technologies, detailing the principles and devices for capturing bioelectrical, biophysical, and biochemical signals. Section 3 investigates the crucial bottleneck of power, exploring both low-power design principles and self-powering strategies through energy harvesting. Section 4 addresses the critical challenge of communication in disaster zones where standard infrastructure has failed, analyzing terrestrial, aerial, and space-based ad hoc networking solutions. Section 5 details the data processing and analytics architectures—from edge to cloud—required to translate raw sensor data into actionable intelligence in real-time, and examines the data visualization and decision-support tools, such as augmented reality (AR) and heads-up displays (HUDs), that present this information to responders and commanders. Finally, Section 6 discusses practical applications.

2. Principles and Devices for Personnel Health Sensing Technologies

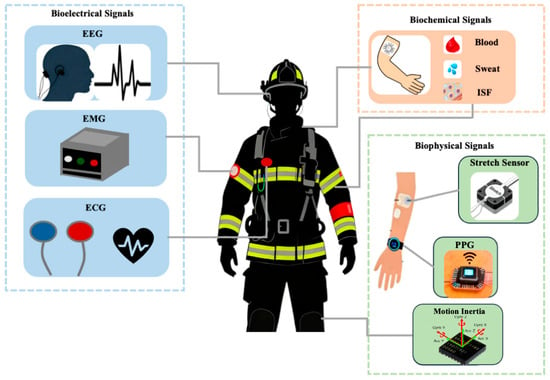

The health and safety of personnel operating in demanding or hazardous environments, such as the emergency responder depicted in Figure 1, are critically dependent on real-time physiological monitoring. Continuous tracking of vital signs, physical exertion, and stress levels is essential for preventing injury, managing fatigue, and optimizing performance. Modern wearable sensing systems achieve this by integrating a suite of sensors to capture a holistic physiological profile. These technologies can be broadly classified into three primary categories based on their sensing targets: bioelectrical, biophysical, and biochemical signals. This section will review the fundamental principles and key device innovations within each of these domains.

Figure 1.

The Health Monitoring for Emergency Responders.

2.1. Bioelectrical Signals

Bioelectrical signals, which originate from the electrical activity of cells and tissues, provide a foundational source of physiological data. The most prominent signals in this category used for health monitoring are the electrocardiogram (ECG), electroencephalogram (EEG), and electromyogram (EMG).

The Electrocardiogram (ECG) contains a wealth of information about an individual’s cardiac state by capturing the electrical potential changes generated by the heart’s activity [3]. The clinical standard for ECG acquisition relies on wet Ag-AgCl electrodes, which use an electrolyte gel to decrease the skin-contact impedance [4]. However, these electrodes are ill-suited for long-term monitoring as the gel can dehydrate, increasing impedance and causing skin irritation [4]. To overcome these defects, dry electrodes were developed. Asadi et al. developed a compact and wearable electrocardiogram (ECG) sensor using graphene-elastomer electrodes, which were characterized through tests on both electronic patient simulators and human subjects. The electrodes demonstrated high conductivity, flexibility, and ultralight weight (less than 10 mg), along with significantly lower skin impedance compared to existing electrodes, including other graphene-based sensors [5]. While functional, they are highly prone to motion artifacts, as movement can create air gaps that increase impedance. However, the transition from lab-bench to the fireground remains challenging. The extreme physical exertion of responders creates significant shear forces that can delaminate these delicate nanomaterials. Future iterations must focus on improving the adhesion strength and mechanical durability of graphene-elastomer interfaces to withstand the high-impact movements typical of search and rescue operations without degrading signal quality. Gao et al. developed and tested a prototype heart monitor using flexible capacitive ECG electrodes. The detection and amplification circuitry employed high-performance operational amplifiers (OpAmps) to filter the motion artifact effectively [6]. More advanced solutions include microneedle electrodes, which painlessly penetrate the stratum corneum to access the conductive epidermis, thereby reducing impedance and enabling high-quality signal collection even during dynamic processes [5,8]. Another alternative is the capacitive sensor, which can extract the ECG signal via capacitive coupling without direct skin contact. Wang et al. developed a novel PDMS-based flexible dry electrode with a pin structure for long-term EEG measurement, eliminating the need for conductive gel and skin preparation. The electrode demonstrated high signal quality and the ability to measure EEG effectively even on hairy sites, addressing key limitations of traditional wet electrodes [9]. This non-contact approach, however, remains highly susceptible to motion artifacts, making it challenging for real-time monitoring during strenuous activity [6,10].

The Electroencephalogram (EEG) records the electrical activity of neuronal groups in the brain, providing vital information on mental workload, stress, and cerebral diseases [7,8]. A primary challenge in wearable EEG is overcoming hair interference. To address this, needle-like or spring-contact electrodes have been designed to move hairs aside and make direct contact with the scalp, achieving high signal quality even during motion [9,10,11]. Similarly to ECG, microneedle electrodes are also employed, with their tips passing through the corneum to reduce the electrode-skin interface impedance. Ren et al. developed a novel bendable microneedle-array electrode (MAE) using magnetorheological drawing lithography for continuous EEG recording. Composed of flexible PDMS pillars with rigid microneedle tips, the electrode can penetrate the stratum corneum without skin preparation or gel electrolyte, reducing impedance and preventing breakage during use. While microneedles effectively bypass the stratum corneum, their structural integrity is a concern under the pressure of protective equipment (PPE). For practical deployment, these arrays require ruggedized backing layers to prevent fracture during accidental impacts or when compressed under tight-fitting SCBA straps. This innovation offers a promising solution for long-term EEG monitoring [12]. Capacitive sensors offer a non-contact alternative for EEG as well. Chi et al. developed wireless noncontact ECG and EEG sensors that operate through thin fabric layers without direct skin contact or conductive gel, significantly improving patient comfort and enabling long-term monitoring. Integrated into wearable devices, these sensors demonstrated performance comparable to traditional Ag/AgCl electrodes [13]. For improved user comfort, privacy, and long-term use, novel form factors have been explored, such as earplug-structured electrodes that detect EEG from within the ear canal. Goverdovsky et al. [14] introduced a novel in-ear EEG sensor utilizing viscoelastic generic earpieces and conductive cloth electrodes, offering a discreet, unobtrusive, and cost-effective solution for 24/7 brain activity monitoring. Conductive foam can also be applied in such sensors. Liao et al. [15] developed a wearable, wireless EEG-based brain–computer interface (BCI) device featuring novel dry foam-based sensors, eliminating the need for conductive gel and skin preparation.

Finally, the Electromyogram (EMG) captures the subtle changes in electrical signals caused by muscle excitation, with applications in sports science and neuromuscular rehabilitation. Hussain and Park investigated myoelectric biomarkers derived from electromyography (EMG) as predictive tools for post-stroke gait analysis and rehabilitation management [16]. Given that EMG is often measured during movement, sensor design focuses heavily on mitigating motion artifacts. Stretchable electrodes, such as snake-like patterns, can adhere to the skin and deform with it, achieving a high Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). Lee et al. [17] developed a wireless, skin-attachable, stretchable EMG sensing system using PDMS substrates and microfabrication techniques to achieve robust adhesion and reliable signal acquisition without foam tape or conductive gel. Microneedle electrodes have also been shown to reduce motion artifacts by breaking the corneum barrier to form a stable skin contact. Hou et al. introduced a Miura-ori structured flexible microneedle array electrode (M-MAE) for biosignal recording, featuring enhanced air ventilation channels to address sweat accumulation and skin irritation during long-term use [18]. While capacitive electrodes allow for non-contact EMG monitoring, they often require shielding to remove environmental interference. Demonstrating the progress in this area, Carbon/Salt/Adhesive (CSA) electrodes have shown a better SNR (38.3 dB) and signal-to-motion ratio (24.1 dB) than conventional wet electrodes [19].

2.2. Biophysical Signals

Beyond the body’s electrical output, biophysical signals, which capture mechanical and physical properties, offer a second critical layer of health information. This category primarily includes the measurement of personnel motion—both large-scale inertial movement and fine-grained body mechanics—as well as fundamental vital signs like heart rate and pulse.

Monitoring personnel movement is fundamental for assessing physical exertion, tracking activity, and predicting injuries [19,20]. This is commonly achieved using inertial sensors, such as accelerometers and gyroscopes. These body-worn devices are a practical alternative to the “gold standard” optical tracking systems, which are non-portable and high-cost. Further innovation in this area has produced self-powered inertial sensors, such as a Triboelectric Nanogenerator (TENG) configured as a gyroscope ball, which can simultaneously detect multi-axis acceleration and rotation while also harvesting energy, Shi et al. [21] developed a triboelectric nanogenerator-based gyroscope ball (T-ball) capable of self-powered motion monitoring, including multiaxis acceleration and rotation sensing.

Simply knowing a responder is moving is not the whole story. Inertial sensors often fail to capture fine-grained body motion signals, such as the bending of a joint or the act of swallowing, which also contain significant health information. To capture these more subtle motions, various strain sensors are employed. These sensors operate on piezoelectric, triboelectric, piezoresistive, or capacitive principles, generating a signal as they “deform along with a body motion” [21,22,23]. Specific examples include TENGs integrated into smart socks to self-power the monitoring of gait and plantar pressure, and liquid metal piezoresistive sensors capable of detecting a wide plantar pressure range from 0 kPa to 400 kPa. Mao et al. [24] developed a portable, flexible, self-powered biosensor based on ZnO nanowire arrays and a PET substrate for real-time motion monitoring in high humidity environments. Utilizing the piezoelectric effect, the biosensor can operate in air and water without external power, enabling the monitoring of joint angles, motion frequency, and heart rate. Low et al. [25] developed a wireless smart insole using flexible microfluidic sensors to monitor gait. The sensors, made with stretchable materials and filled with a conductive liquid, can measure foot pressure and ankle movement. Optical fiber sensors are another viable option, noted for their ability to overcome electromagnetic interference well. Leber et al. [26] created stretchable optical fibers that can sense extreme movements like stretching, bending, and pressing. These fibers can stretch up to 300% while still guiding light. They were used in devices like a knee brace to track motion, a glove to control a virtual hand, and a tennis racket to detect ball hits.

Alongside motion, heart rate and pulse are arguably the most simple and direct indicators of cardiovascular health. This data can be acquired through several methods. First, heart rate can be electrically derived from an ECG signal, typically by applying peak-seeking and window averaging algorithms to the data. Second, pressure sensors can directly detect the mechanical pulse wave. These include piezoresistive sensors, such as those fabricated from DNA-like double helix yarns, which offer “ultrafast-response/recovery” [27,28,29]; and highly sensitive capacitive sensors, which can use micro-brush structures to “amplify the signal” enough to detect weak, deep pulses like the internal jugular vein pulse [30,31,32]. Piezoelectric materials have also been used for multi-point heart rate monitoring. Pang et al. [33] developed a bioinspired microhairy sensor designed for high skin conformability and enhanced signal detection. The sensor uses microhair structures to improve contact on non-flat surfaces, achieving a 12-fold increase in signal-to-noise ratio for capacitive signals. This advancement allows the sensor to measure weak pulsations, such as internal jugular venous pulses from the human neck.

The third and most common method in commercial wearables is Photoplethysmography (PPG). This optical technique detects “volume changes in blood flow through the skin.” Despite its ubiquity, conventional PPG hardware is often rigid, consumes significant power, and struggles to acquire accurate data during strenuous exercise or optical noise. To overcome these limitations, Rasheed et al. [34] developed a self-powered wearable sensor that can continuously monitor heart rate and blood pressure at multiple points on the body. The sensor uses piezoelectric materials (PVDF) combined with a special thin-film transistor to generate power from body movements, eliminating the need for batteries. Research into organic photoelectric sensors is also enabling the development of flexible, skin-conformable PPG sensors that are far more suitable for continuous, active monitoring. Simões et al. [35] created a flexible photodetector for wearable health sensors, making them more comfortable and accurate. Current sensors are often stiff and struggle to detect near-infrared (NIR) light well. The researchers used new materials to improve NIR sensitivity.

2.3. Biochemical Signals

The final category, biochemical signals, moves beyond physical or electrical properties to analyze the body’s chemistry. This is most often achieved by sampling biofluids, with sweat, blood, and interstitial fluid (ISF) being the primary targets.

Sweat is an increasingly important body fluid for non-invasive analysis. The monitoring principle involves performing continuous in situ sweat analysis for key biomarkers such as lactic acid, glucose, various ions, and pH. Sempionatto et al. [36] developed smart eyeglasses that monitor sweat in real-time. Sensors in the nose pads measure lactate and potassium levels, while a Bluetooth system in the arms sends data to a device. This analysis is typically conducted using either electrochemical sensors, which can detect biomarkers like lactic acid and potassium ions, or optical sensors. Optical methods offer several routes: colorimetric sensors provide simple, visual feedback and can be used to quickly distinguish dehydration from overhydration by observing color changes [37,38]; fluorescence-based sensors can be integrated into wearable patches to detect glucose, lactate, pH, and chloride [39,40]; and eletrochemiluminescence (ECL) has been applied to detect lactic acid to distinguish the intensity of the exercise [41].

While sweat analysis is minimally invasive, blood remains the gold standard. The goal for wearable systems is to non-invasively test for critical health markers. Blood oxygen, for instance, is commonly measured using Photoplethysmography (PPG), which uses an LED and a photodetector (PD) to detect transmitted or reflected light from biological tissues [41,42]. This technology is being improved with flexible, skin-adapted Organic Photodetectors (OPDs) for better comfort [43]. For non-invasive blood glucose, optical methods such as Near-Infrared (NIR) or Raman spectroscopy are being explored [44]. Other novel approaches include microwave-range electromagnetic sensors, which can be placed on the limbs to detect blood lactate [45].

As a compromise between the accessibility of sweat and the rich data of blood, Interstitial Fluid (ISF) has emerged as a key target. Its composition is mostly determined by the types of cells around it and has many chemicals similar to blood, making it a viable proxy for blood-level analysis. Several methods exist to access ISF. Reverse Iontophoresis (RI) uses a potential difference between two skin-surface electrodes, causing ions and neutral species like glucose to permeate out with water flow [46]. Its primary drawback is a slow extraction rate (5–10 min), which hinders real-time detection [47]. To “break the defect” of slow extraction, microneedle arrays are used to painlessly penetrate the stratum corneum, enabling continuous real-time detection of markers like ketone bodies [48]. A third method, sonography, uses ultrasound to induce cavities, increasing the porosity of the skin, which, when combined with a vacuum, extracts the ISF [49].

In summary, while the field of wearable health sensing has advanced significantly, several persistent challenges remain. A primary limitation across many sensor types, particularly bioelectrical and optical sensors, is susceptibility to motion artifacts, which severely degrades data quality during the strenuous activity typical of emergency response. As noted, motion artifacts in responder scenarios are often ten times greater in amplitude than the target bio-signals. To transition from raw data to clinical reliability, robust signal processing is required. Current methodologies can be categorized into three approaches: First, Adaptive Noise Cancelation (ANC) is particularly viable for emergency responders equipped with multi-modal suits. This method uses an auxiliary reference signal—typically from the inertial sensors (accelerometers) already embedded for localization—to model and subtract the motion component from the contaminated ECG or PPG signal [50]. Second, for multi-sensor arrays, Blind Source Separation (BSS) techniques such as Independent Component Analysis (ICA) are employed [51]. ICA decomposes the signal into independent sources, allowing the isolation and removal of motion artifacts under the assumption that the physiological signal and the mechanical motion are statistically independent. Third, emerging Learning-Based Approaches are addressing the complex, non-linear artifacts caused by the chaotic movements of firefighting or rescue tasks. Deep Learning architectures, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTMs), are increasingly used to automatically feature-extract and reconstruct clean waveforms without relying on the linear assumptions of traditional filters [51].

Furthermore, many current devices face limitations in power consumption, rigidity, and long-term user comfort, hindering their practical utility. For biochemical analysis, a key challenge remains in balancing the trade-off between invasiveness and real-time data fidelity. Beyond signal quality, the ‘robustness gap’ remains a significant barrier. Many promising prototypes, such as skin-conformable films, currently lack the thermal stability to survive high-heat environments or the encapsulation necessary to resist heavy perspiration and chemical exposure. Table 1 concluded all types of sensors mentioned in the current review, along with their key advantages, limitations and challenges, wearability and maturity status. Bridging this gap requires shifting focus from pure sensitivity optimization to the development of ruggedized, environmentally hardened sensor packaging.

Table 1.

Summary for Personnel Monitoring technologies.

Future research is trending in several key directions to address these shortcomings. A dominant trend is the development of flexible, stretchable, and skin-conformable materials to create sensors that move with the body, improving both comfort and signal stability. Second, there is a strong push towards multi-modal sensor fusion, where data from different sources (e.g., ECG and accelerometry) are algorithmically combined to achieve a more robust and accurate physiological picture. Third, energy harvesting and low-power electronics (e.g., TENG-based or piezoelectric devices) are critical for extending operational life. Finally, the application of advanced signal processing and machine learning is becoming essential for filtering noise, correcting artifacts, and translating complex, multi-stream sensor data into actionable insights for personnel safety.

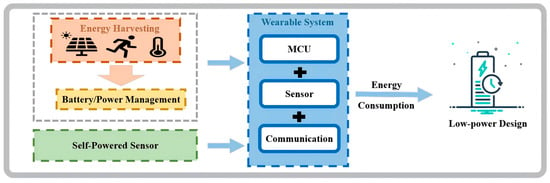

3. Powering Strategies for Wearable Devices

The operational endurance of wearable IoT systems in emergency response is fundamentally constrained by their power source. Continuous, long-term monitoring of personnel health is a primary objective, yet it is dependent on the development of smart, low-power wearable devices [52]. Conventional battery-powered systems present a critical bottleneck [53]. The inclusion of a battery imposes significant constraints on the device’s final volume and weight, and its finite lifespan leads to the disruption of continuous monitoring when depleted. In the harsh or inaccessible environments typical of emergency response, battery replacement or charging is often costly and labor-intensive, making it a major logistical challenge [54]. A complete self-powered system is an integrated architecture comprising an energy harvesting unit, a power management circuit (PMC), an energy storage unit, and the functional sensor circuits (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Power Management Circuit for Wearable Power-Loop.

The primary modality for powering these systems involves harvesting biomechanical energy from the responder’s inherent motion. Two key technologies dominate this domain: Piezoelectric Nanogenerators (PENGs) and Triboelectric Nanogenerators (TENGs). Hu et al. [55] developed a PENG using optimized ZnO nanowires that achieved a high output of 20 V and 6 μA, sufficient to replace batteries for small electronics. Fan et al. [56] introduced a flexible triboelectric generator (TEG) based on stacked polymer films with distinct triboelectric properties to harvest mechanical energy through friction. This low-cost, scalable device achieved an output voltage of 3.3 V and a power density of 10.4 mW/cm3. PENGs generate electricity via mechanical stress applied to piezoelectric materials. TENGs, which leverage contact electrification and electrostatic induction [57,58], generally offer a higher power output by converting frictional energy from textiles rubbing or contact separation during movement. This TENG-based approach has proven viable for driving wireless sensors and even life-critical devices like symbiotic cardiac pacemakers [59,60], demonstrating its potential for responder-grade systems. However, a significant challenge remains: both PENGs and TENGs typically produce pulsed outputs. Consequently, sophisticated power management circuits are essential to rectify, regulate, and condition this intermittent output into a stable, low-voltage DC supply suitable for microelectronics [53]. It is also worth noting that widespread commercial deployment faces engineering challenges regarding long-term durability and environmental stability. Current translational research is focusing on ruggedized encapsulation to ensure these devices can withstand the frictional wear and humidity typical of disaster zones, bridging the gap between laboratory prototypes and field-ready gear.

To complement the intermittent nature of biomechanical harvesting, other energy sources are integrated. Lee et al. [61] developed flexible thermoelectric generators (TEGs) with magnetically self-assembled soft heat conductors and stretchable interconnects, enabling efficient heat transfer and conformal contact with curved surfaces. These TEGs achieved high power output, mechanical durability, and successfully powered wearable devices. TEGs exploit the Seebeck effect, generating a continuous DC current from the thermal gradient between the responder’s body heat and the ambient environment. This provides a stable baseline power, particularly when motion is minimal. Furthermore, ambient energy sources can be scavenged. Kaltenbrunner et al. [62] developed ultra-thin, flexible perovskite solar cells with a stabilized efficiency of 12% and an exceptional power-per-weight ratio of 23 , enabled by chromium oxide–metal contacts for improved air stability. Such flexible, lightweight organic photovoltaic cells can be integrated into textiles to harvest solar energy. In parallel, Biofuel cells represent a biochemical harvesting method, capable of generating electricity directly from the redox reactions of body fluids, such as sweat [63,64,65].

To assist system designers in selecting the most appropriate power sources for specific emergency scenarios, we present a comparative analysis of energy harvesting technologies in Table 2. The choice of energy source involves a critical trade-off between power density and environmental constraints. For instance, while photovoltaic cells offer the highest power density (up to 100 mW/cm2 outdoors) suitable for extended outdoor missions, their utility is severely limited in low-light conditions typical of smoke-filled structures or night operations. The table further details the output voltage ranges and limiting conditions for each technology, emphasizing the need for hybrid power management strategies in complex disaster environments.

Table 2.

Energy Harvesting Technologies Comparison.

Given that any single energy source may be unreliable, the most resilient solution is the development of Hybrid Cells. Xu et al. [66] developed a hybrid energy harvesting cell combining dye-sensitized solar cells and piezoelectric nanogenerators using aligned ZnO nanowire arrays, enabling simultaneous or individual harvesting of solar and mechanical energies. This strategy involves the synergistic integration of multiple harvesting modalities, such as combining TENGs for motion with PVs for light. By creating a redundant power-generation architecture, hybrid systems can compensate for the intermittent drawbacks from one single energy source, thereby ensuring the robust and continuous operation required for life-critical personnel monitoring. Where active harvesting is unfeasible, alternative (non-autonomous) strategies include wireless power transmission via Near-Field Communication (NFC) or Radio Frequency (RF) beacons [67,68,69].

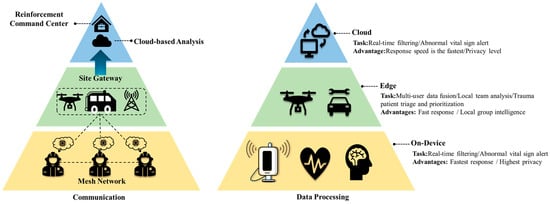

4. Communication Methods for IoT-Enabled Wearable System

In disaster scenarios, where terrestrial communication infrastructure is often significantly compromised or non-functional, ensuring the reliable transmission of health data from IoT-enabled wearable systems worn by frontline personnel to a rear command center necessitates an ad hoc networking strategy (Figure 3). This strategy hinges on integrating terrestrial, aerial, and space-based assets [70].

Figure 3.

The Disaster-Scene Data Flow and Computing Continuum Pyramid.

At the most immediate level, recovery of terrestrial networks is the primary goal. When infrastructure is damaged, solutions like rapidly deployable vehicle-mounted base stations, known as movable and deployable resource units (MDRUs), can be used to restore connectivity swiftly [71]. Another terrestrial solution is the network-in-a-box (NIB) concept, which fits all necessary hardware and software into portable devices, creating a dynamic and versatile architecture [72,73]. For low-power, long-distance data transfer from sensors, technologies like the Long Range (LoRa) protocol are particularly effective, though they offer limited capacity [74]. In the absence of any infrastructure, personnel and their devices can form mobile ad hoc networks (MANETs) or utilize device-to-device (D2D) communications [75,76]. Table 3 provides approximate values based on the literature for typical range, latency, bandwidth, and power consumption, serving as a comparative reference for coherent technology development and application.

Table 3.

Communication Technologies Comparison.

Since recovering terrestrial networks can be a slow process, aerial networks are frequently installed, using platforms like drones, balloons, or gliders as flying aerial base stations (ABSs) [76]. These are broadly categorized as low-altitude platforms (LAPs), such as multi-rotor drones [82], or high-altitude platforms (HAPs), like balloons operating at altitudes up to 50 km. LAPs offer fast implementation, while HAPs provide much longer endurance, capable of staying aloft for months, and a wider coverage radius. A notable example includes Alphabet’s Project Loon, which provided essential connectivity to over one hundred thousand people in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. The primary challenges for aerial networks involve their rapid deployment, controlling their trajectories, and ensuring sufficient flight endurance [83].

Ultimately, these ground and air-based networks often rely on space networks for resilient backhaul connectivity [84,85]. While emerging low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellations, such as Starlink [86], have been used to provide backup networks in disaster zones, satellites are most crucial for providing the backhaul link to aerial nodes, especially HAPs. This integration of all three layers forms a Space-Air-Ground Integrated Network (SAGIN) [70]. In this paradigm, data from a first responder’s IoT sensor (ground) might be relayed through a UAV (air), which then uses a satellite link (space) to transmit the data back to the core network and command center.

Managing such a complex, dynamic, and heterogeneous network requires advanced networking layer paradigms. Hoque et al. [87] proposed a hybrid architecture combining Software Defined Networking (SDN) and Delay Tolerant Networking (DTN) to enhance communication in post-disaster scenarios, featuring layers for victim nodes, DTN storage, monitoring, and control. Given the intermittent connectivity and unpredictable topology, DTNs rely on a “Store and Forwarding” routing mechanism, where a node can store a message until it finds a connection to the next hop, which is essential when no direct end-to-end path exists. To manage the overall network, Software-Defined Networking (SDN) can be employed to decouple the network’s control plane from the data plane, easing management [88,89]. Furthermore, to minimize latency and conserve precious backhaul bandwidth, UAV-enabled multi-access edge computing (MEC) can be utilized [90]. This allows voluminous IoT health data to be analyzed at the network edge, with only critical alerts and summaries being transmitted back, which is vital for real-time health monitoring in low-bandwidth environments [91].

5. Data Processing and Visualization

5.1. Data Processing and Analytics

In a large-scale emergency response scenario, such as a building collapse or wildfire, terrestrial communication infrastructure is often damaged, overloaded, or non-existent. Wearable sensors on frontline personnel (e.g., firefighters, rescue teams) generate a massive, constant stream of health data. Transmitting this raw data to a distant cloud command center is frequently unfeasible, consuming limited bandwidth and creating life-threatening latency [92]. The solution is a tiered processing architecture that analyzes data as close to the personnel as possible [93]. This edge-to-cloud model is bifurcated into Fog Computing and Cloud Computing.

Fog computing is a decentralized computing infrastructure that moves data processing closer to where the data originates, at the network’s edge [94]. This hierarchical model is distributed across three distinct layers: the ‘On-Device’ Edge, the Fog Layer, and the Cloud. At the lowest level, ‘On-Device’ Edge computing occurs directly on the wearable microcontroller. Its processing boundary is strictly personal—handling high-frequency signal conditioning (e.g., filtering motion artifacts from raw ECG) and triggering immediate, life-critical haptic alerts for the individual responder. One step up is Fog Computing. Unlike the wearable device, the Fog Layer serves as a local tactical hub. In an emergency, these “fog nodes” are not remote data centers but the physical hardware deployed at the scene—devices like a vehicle-mounted command unit, an aerial drone, or a portable network-in-a-box at the incident command post, responsible for aggregating data from multiple personnel to assess team-level status before transmitting summaries to the cloud. This architecture is ideal for time-sensitive applications like emergency response systems. Its primary advantage is overcoming infrastructure failure. By processing data at or near its source, it dramatically reduces latency and bandwidth usage, which is critical in regions with unreliable connectivity [95]. This capability can be the difference between life and death in urgent scenarios. For example, a fog node can perform local pre-processing and analysis of a firefighter’s vital signs, enabling real-time diagnostics that would be impossible over a congested or failed network [96].

This local processing power enables real-time predictive analytics. By deploying AI and ML models at the edge, the fog node can analyze data streams to anticipate complications before they become critical. In a rescue context, this means detecting a sudden vital sign anomaly—such as a pattern indicative of an impending heart attack from overexertion or a potential decline in health from smoke inhalation—and issuing an immediate, local alert to the team leader, rather than waiting for a delayed analysis from a remote command center [96,97,98]. This decentralized architecture also bolsters security. Transmitting sensitive health data over ad hoc, potentially unsecured networks poses significant risks. Fog computing mitigates these risks by processing data locally, reducing the exposure to potential cyber threats and minimizing data transmission [99].

The cloud (i.e., the rear command center) still serves a vital function for further processing and long-term storage. It receives summaries and critical alerts from the on-site fog nodes, allowing commanders to maintain situational awareness of the big picture—such as overall team health and resource allocation. Crucially, the strategic value of this layer lies in the cloud-native properties of elastic scaling and distributed resilience. Unlike local fog nodes which have fixed computational limits, the cloud infrastructure can dynamically allocate resources to handle massive, unpredictable surges in data traffic during a mass casualty incident, ensuring operational continuity and fault-tolerant service orchestration even when local infrastructure is under severe stress. However, this architecture’s challenges are amplified in a disaster. Responders from different agencies bring a diverse array of devices and systems, making interoperability a significant hurdle. The system must scale as more teams arrive, and managing and updating numerous decentralized nodes in a chaotic environment is a complex logistical and technical challenge.

5.2. Data Visualization and Decision-Making Support

In emergency response, advanced visualization technologies are critical for supporting personnel’s situational awareness (SA) and aiding decision-making [100]. Technologies like Augmented Reality (AR) can streamline cognitive processing in high-stress, time-sensitive situations and reduce the time to action. This section explores the visualization technologies used to present data to both frontline personnel (on-site) and command centers (rear) [101,102].

The hardware platforms used to deliver this information are varied. According to one systematic review of 90 relevant papers, visualization hardware for first responders is primarily divided into three categories. The most common form in research is Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs), which include both Optical See-Through (OST HMD) [103,104,105,106] and Video See-Through (VST HMD) [107,108,109,110] variants. The other categories are Handheld Devices, such as familiar smartphones or tablets [111,112,113,114], and Stationary Devices, which are mainly used in command centers and include desktop displays or large touch-walls [115,116,117,118,119,120].

Within AR head-mounted displays, the context of information presentation is crucial and is mainly divided into two types. The first is a Heads-Up Display (HUD), which refers to 2D or 3D interface elements bound to the user’s orientation. This information is “stuck” to the user’s field of view (i.e., screen-locked) and remains in the same position regardless of where the user turns their head [104,105,106,113,121,122,123,124,125]. The second, Spatial Augmentation, refers to projecting virtual objects (2D or 3D) into the real environment and “locking” them to a real-world position. For example, a virtual arrow will be fixed on the ground, and the user can walk around it [107,114,126,127,128]. To support decision-making, AR interfaces display a variety of specific “building blocks” that form the core of the user interface. These elements can be grouped by their function.

First, Environment Awareness elements enhance perception in degraded conditions. This includes Edge Detection, which enhances perception in low-visibility conditions like smoke by overlaying object outlines; one study reported this “significantly improved search and rescue time and enhanced the ability to detect unexpected hazards” [129,130]. It also includes X-Ray visualization, which provides the ability to “see through” occluding surfaces (like walls) to display hidden dangers or locate teammates [107,116,123,131], and Spatial Reconstruction, which overlays a 3D virtual model (like a wireframe) of a building to help responders understand the original structure of a collapsed building [112,132].

Second, Object Awareness is achieved via Object Highlighting. This technique uses visual cues (like colored borders, outlines, or shading) to emphasize important objects in the scene [133], and is widely used to mark victims, suspects, evidence, or hazardous materials [131,134,135]. The DARLENE system, for example, uses a deep neural network to automatically identify and highlight objects and was shown to “improve situational awareness” under stress [133,136].

Third, Navigation elements, which are the most frequently discussed interface category in the research, guide the user. Traditional navigation includes displaying 2D or 3D maps, compasses, and radars showing nearby teammates or hazards in the field of view [137,138,139]. Neo-navigation techniques are more integrated, including “breadcrumbs” (marking the path taken) [105,140], “Points of Interest” (PoIs, marking key locations) [112,137,141], and navigation arrows or lines drawn directly in the environment [105,142].

Fourth, Augmented Guidance provides direct procedural and informational support. This can be in the form of Augmented Support, which provides step-by-step procedural guidance such as an AR checklist for triage [99,136,137], or allows for receiving real-time “Annotations” from a command center or remote expert, who can draw markers directly into the responder’s field of view [109,143,144]. It also includes Augmented Enhancement, which directly displays information from IoT sensors, such as showing a patient’s “Vitals Monitor” in the field of view [103,144,145], or displaying a “Live Video Feed” from devices like drones [118,133,136,140,146].

Finally, Interface Management elements are crucial for preventing information overload. This includes Alerts, which warn responders of critical dangers (like environmental heat or discovery of a weapon) using visual, auditory, or haptic cues [124,136,147,148]. A key strategy to reduce persistent visual clutter and associated cognitive load is the use of On-Demand Interfaces, where the interface remains hidden by default and only appears when “summoned” by the user via a specific gesture (like turning the palm up) [140,145,149].

6. Application of Smart Wearable Systems in Emergency Response

The preceding sections have deconstructed the core technological components—sensors, power, communication, and data processing. This section now synthesizes these elements, illustrating their integrated application in distinct, high-stakes emergency response scenarios. We aim to demonstrate how the “system-of-systems” approach (introduced in Section 1) provides tangible safety and operational advantages by tailoring the technology stack to solve the primary, and often unique, challenge of each scenario. Table 4 shows the integrated mapping of IoT technologies to specific emergency response scenarios, illustrating how the technology stack is tailored to address unique challenges in high-stakes environments.

Table 4.

Integrated Mapping of IoT Technologies to Emergency Response Scenarios.

6.1. Urban Firefighting: Managing Coupled Physio-Thermal Stress

Urban firefighting presents an extreme case of coupled physiological and environmental stress. The core challenge is not just high heat or exertion, but the ambiguity of their combined effect. A high heart rate (HR) is expected, but when does it transition from operational tachycardia to life-threatening cardiac strain (e.g., ischemia)? The leading cause of line-of-duty death, cardiac arrest, often results from this lethal combination [5]. An integrated IoT system must therefore move beyond simple threshold alerts.

The solution requires fusing data from multiple sources (Section 2): textile-based ECG electrodes [4] to monitor not just HR but specific morphological changes (like ST-segment depression) indicative of cardiac distress, coupled with skin-contact or ingestible sensors tracking core body temperature (CBT). This multi-stream data is transmitted to a fog computing node (Section 5.1), likely integrated into the SCBA (Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus) to ensure proximity and power. This edge device runs a real-time Physiological Strain Index (PSI) algorithm, which algorithmically combines HR and CBT rate-of-change, while a parallel process scans ECG data for critical arrhythmias.

This enables a sophisticated, tiered decision support workflow. When the PSI model predicts a critical state, it triggers: (1) A local, non-visual haptic alert (Section 5.2) in the firefighter’s helmet. (2) A “High-Risk” alert, pushed via the on-site MANET (Section 4), to the team leader’s AR display. (3) If an ST-segment anomaly is detected, an automated, high-priority “MAYDAY—CARDIAC” alert is propagated directly to the incident commander’s dashboard. This proactive, model-driven approach allows intervention before incapacitation.

6.2. Earthquake and Urban Search and Rescue (USAR): 3D Localization and Fatigue in Comms-Denied Environments

In USAR operations, the environment is defined by its three-dimensional, GPS-denied complexity and the complete, prolonged failure of communication infrastructure. The primary challenge is twofold: (1) tracking a responder’s 3D position inside a collapsed structure, and (2) managing long-term fatigue over multi-day operations. The core technical problem for localization is that IMU-based dead reckoning (Section 2.2, [20]) suffers from inevitable accumulated drift, rendering it useless alone after minutes.

The integrated solution is a sensor-fusion approach run on the responder’s personal device. The high-frequency data from IMUs (tracking vector and rotation) is continuously processed through an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF). This filter is then periodically corrected by low-frequency, absolute-position “pings” from UWB (Ultra-Wideband) beacons deployed by the team as they advance. This fusion of IMU and RF beacon data solves the drift problem and generates a reliable 3D path.

Given the multi-day timeline, the power strategy (Section 3) becomes critical, necessitating biomechanical energy harvesting (e.g., PENGs in boot soles) to provide trickle-charging for these essential localization and communication circuits. The system must operate in a Delay-Tolerant Network (DTN) mode (Section 4, [150]). Non-critical data, such as cumulative exertion patterns from IMUs and EMG (Section 2.1 and Section 2.2), is stored locally for later “data-ferrying” by a drone-based aerial node (Section 4). Only critical alerts, such as a “Man-Down” signal triggered by a specific IMU signature (sudden high-G impact followed by prolonged motionlessness), are given priority to propagate immediately through the fragile mesh network.

6.3. Hazardous Materials (Hazmat) and Chemical, Biological, Radiological or Nuclear (CBRN) Incidents: Monitoring the Sealed Microclimate

For Hazmat and CBRN incidents, the responder is encapsulated within impermeable PPE, creating a unique, sealed microclimate. The threat is twofold and immediate: external chemical breakthrough and internal asphyxiation or hyperthermia. The responder is in a race against time against their own metabolism.

The sensing system must therefore be dual-facing. External electrochemical sensors (Section 2.3), laminated onto the suit, monitor for target Toxic Industrial Chemicals (TICs). Simultaneously, a suite of in-suit sensors monitors the microclimate (O2, CO2, temperature, humidity) while skin-contact sensors (Section 2.1 and Section 2.2) track the responder’s core temperature and metabolic rate (estimated from HR).

This data feeds an in-suit fog node (Section 5.1) running a predictive microclimate model. This model uses the responder’s real-time metabolic rate to forecast the future rate of CO2 buildup and heat accumulation, projecting when the in-suit atmosphere will become untenable (e.g., CO2 > 2.0% or CBT > 39 °C). This output is rendered as the primary decision aid: a dynamic “Time-to-Decon: 12:30” countdown displayed directly on the responder’s in-mask HUD (Section 5.2). This countdown is instantly overridden by a high-priority “SUIT BREACH” alert if the external sensors detect a chemical, providing unambiguous, actionable intelligence for managing the life-critical work-rest cycles.

6.4. Mass Casualty Incidents (MCI): Augmented Decision Support and Cognitive Unloading

During an MCI, the responder’s primary challenge shifts from personal survival to managing overwhelming cognitive load. The triage officer acts as a “human data router,” a bottleneck forced to manually assess, categorize, and remember the state of dozens of victims. The IoT system’s role here is to automate data routing and offload this cognitive burden.

The workflow is enabled by AR-enabled HMDs (Section 5.2) and low-cost, disposable biosensor tags (Section 2.2 and Section 2.3). When the triage officer applies a tag, their HMD “commissions” it, linking that tag’s ID to a GPS location. The tag (e.g., using PPG for HR/SpO2) broadcasts its data. When the officer looks at a victim, the HMD pulls that tag’s real-time vitals and locally runs the START/SALT triage algorithm, immediately suggesting a category (e.g., “IMMEDIATE—RED”) in the AR view.

The officer simply confirms this assessment (e.g., via voice command). Upon confirmation, the HMD instantly performs three actions: (1) It renders a persistent “digital tag” (a large red “I”) over the victim in the officer’s AR view [149,151,152]. (2) It broadcasts this confirmed digital tag to the HMDs of other nearby responders (e.g., stretcher-bearers). (3) It pushes the victim’s full data (ID, vitals, location, triage category) to the fog-node command post (Section 5.1), auto-populating a “digital twin” of the casualty collection point. This transforms a single officer’s action into a real-time, network-wide update, converting a chaotic scene into an organized, actionable dashboard.

7. Conclusions

Emergency responders operate in some of the most hazardous environments, where their health and safety are critical to the success of life-saving operations and sustainable management in disasters. Traditional methods, such as voice-based check-ins, fail to provide real-time, high-resolution data on responders’ physiological and environmental conditions, leaving dangerous gaps in situational awareness. IoT-enabled wearable systems present a transformative solution by enabling continuous, real-time monitoring of bioelectrical, biophysical, and biochemical signals. These systems, coupled with advanced communication networks, edge computing architectures, and augmented reality visualization tools, allow incident commanders to proactively manage responders’ safety and optimize decision-making in high-stress scenarios.

This review has highlighted the key technological components required to build such systems, including innovations in sensing technologies, self-powering strategies, communication methods for infrastructure-denied zones, and data processing architectures. The integration of these components into a seamless system is essential to ensure reliability and robustness in emergency response scenarios. Practical applications, such as urban firefighting, search-and-rescue missions, hazardous material incidents, and mass casualty events, demonstrate the potential of IoT-based systems to enhance personnel safety, improve situational awareness, and accelerate decision-making.

Despite significant advancements, challenges remain in areas such as interoperability across diverse devices, ensuring data security in ad hoc networks, and optimizing power efficiency for long-term deployments. A critical barrier to the wide-scale adoption of IoT systems in emergency response is the significant disparity in Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) across the component stack. While fundamental sensors such as optical PPG and electrochemical gas detectors are commercially mature (TRL 8–9), their effective readiness often drops to TRL 7 upon integration due to the inability of consumer-grade packaging to withstand the severe thermal and mechanical shocks of firefighting. In contrast, emerging technologies like triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) and biochemical sweat sensors largely remain at TRL 4 (Lab Validation) or TRL 5, as they currently lack the standardized encapsulation required to survive extreme conditions, such as 200 °C heat or full water immersion. Consequently, bridging this “Ruggedization Gap” necessitates a strategic shift in research focus from pure sensitivity enhancement to advanced materials engineering—specifically, the development of robust thermal shielding and self-healing encapsulations that allow these promising laboratory-grade components to function reliably in TRL 9 operational environments. Future research should focus on addressing these challenges, as well as exploring emerging technologies such as hybrid energy harvesting, advanced machine learning algorithms for predictive analytics, and more intuitive augmented reality interfaces. By overcoming these barriers, IoT-enabled wearable systems can become indispensable tools for ensuring the safety and effectiveness of emergency response personnel in the most demanding environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010365/s1, Figure S1: PRISMA figure; Table S1: Comparison with Previous Works.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and F.H.; methodology, J.W., Y.T. (Yongqi Tang) and F.H.; validation, Y.T. (Yunting Tsai); formal analysis, W.W.; investigation, J.W. and Y.T. (Yongqi Tang); resources, W.W.; data curation, J.W. and F.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W., Y.T. (Yongqi Tang) and F.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.T. (Yunting Tsai), Z.H. and W.W.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, J.W. and W.W.; funding acquisition, J.W., Z.H. and W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2023YFC3008700), National Natural Science Foundations of China (No. 52504231, 72404160, 72521001), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2024YFC3014703), and Opening Fund of State Key Laboratory of Fire Science (SKLFS) under Grant No. HZ2025-KF06.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vijayan, V.; Connolly, J.P.; Condell, J.; McKelvey, N.; Gardiner, P. Review of Wearable Devices and Data Collection Considerations for Connected Health. Sensors 2021, 21, 5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiana Da Costa, T.; De Fatima Fernandes Vara, M.; Santos Cristino, C.; Zoraski Zanella, T.; Nunes Nogueira Neto, G.; Nohama, P. Breathing Monitoring and Pattern Recognition with Wearable Sensors. In Wearable Devices—The Big Wave of Innovation; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhani, M.A.; El Kassabi, T.H.; Ismail, H.; Nujum Navaz, A. ECG Monitoring Systems: Review, Architecture, Processes, and Key Challenges. Sensors 2020, 20, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachowicz, T.; Ehrmann, G.; Ehrmann, A. Textile-Based Sensors for Biosignal Detection and Monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; He, Z.; Heydari, F.; Li, D.; Yuce, M.R.; Alan, T. Graphene Elastomer Electrodes for Medical Sensing Applications: Combining High Sensitivity, Low Noise and Excellent Skin Compatibility to Enable Continuous Medical Monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 13967–13975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Soman, V.V.; Lombardi, J.P.; Rajbhandari, P.P.; Dhakal, T.P.; Wilson, D.G.; Poliks, M.D.; Ghose, K.; Turner, J.N.; Jin, Z. Heart Monitor Using Flexible Capacitive ECG Electrodes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 4314–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Park, S.J. HealthSOS: Real-Time Health Monitoring System for Stroke Prognostics. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 213574–213586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Young, S.; Park, S.-J. Driving-Induced Neurological Biomarkers in an Advanced Driver-Assistance System. Sensors 2021, 21, 6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-F.; Liu, J.-Q.; Yang, B.; Yang, C.-S. PDMS-Based Low Cost Flexible Dry Electrode for Long-Term EEG Measurement. IEEE Sensors J. 2012, 12, 2898–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-T.; Liu, C.-H.; Wang, P.-S.; King, J.-T.; Liao, L.-D. Design and Verification of a Dry Sensor-Based Multi-Channel Digital Active Circuit for Human Brain Electroencephalography Signal Acquisition Systems. Micromachines 2019, 10, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-T.; Yu, Y.-H.; King, J.-T.; Liu, C.-H.; Liao, L.-D. Augmented Wire-Embedded Silicon-Based Dry-Contact Sensors for Electroencephalography Signal Measurements. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 3831–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Dou, Z.; Liu, B.; Jiang, L. Fabrication of Bendable Microneedle-Array Electrode by Magnetorheological Drawing Lithography for Electroencephalogram Recording. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 8328–8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.M.; Ng, P.; Cauwenberghs, G. Wireless Noncontact ECG and EEG Biopotential Sensors. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2013, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goverdovsky, V.; Looney, D.; Kidmose, P.; Mandic, D.P. In-Ear EEG from Viscoelastic Generic Earpieces: Robust and Unobtrusive 24/7 Monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.-D.; Chen, C.-Y.; Wang, I.-J.; Chen, S.-F.; Li, S.-Y.; Chen, B.-W.; Chang, J.-Y.; Lin, C.-T. Gaming Control Using a Wearable and Wireless EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interface Device with Novel Dry Foam-Based Sensors. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Park, S.-J. Prediction of Myoelectric Biomarkers in Post-Stroke Gait. Sensors 2021, 21, 5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yoon, J.; Lee, D.; Seong, D.; Lee, S.; Jang, M.; Choi, J.; Yu, K.J.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.; et al. Wireless Epidermal Electromyogram Sensing System. Electronics 2020, 9, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yu, H. Miura-Ori Structured Flexible Microneedle Array Electrode for Biosignal Recording. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2021, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada-Quintero, H.F.; Rood, R.T.; Burnham, K.; Pennace, J.; Chon, K.H. Assessment of Carbon/Salt/Adhesive Electrodes for Surface Electromyography Measurements. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2016, 4, 2100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmes, E.; de Ruiter, C.J.; Bastiaansen, B.J.C.; van Zon, J.F.J.A.; Vegter, R.J.K.; Brink, M.S.; Goedhart, E.A.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M.; Savelsbergh, G.J.P. Inertial Sensor-Based Motion Tracking in Football with Movement Intensity Quantification. Sensors 2020, 20, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, H.; Lee, C. Self-Powered Gyroscope Ball Using a Triboelectric Mechanism. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1701300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Jia, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, T. An Effective Self-Powered Piezoelectric Sensor for Monitoring Basketball Skills. Sensors 2021, 21, 5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Yue, W.; Zhao, T.; Shen, M.; Liu, B.; Chen, S. A Self-Powered Biosensor for Monitoring Maximal Lactate Steady State in Sport Training. Biosensors 2020, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Jia, C.; Bian, M.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B. A Portable and Flexible Self-Powered Multifunctional Sensor for Real-Time Monitoring in Swimming. Biosensors 2021, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.-H.; Chee, P.-S.; Lim, E.-H.; Ganesan, V. Design of a Wireless Smart Insole Using Stretchable Microfluidic Sensor for Gait Monitoring. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leber, A.; Cholst, B.; Sandt, J.; Vogel, N.; Kolle, M. Stretchable Thermoplastic Elastomer Optical Fibers for Sensing of Extreme Deformations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1802629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Jia, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q. Portable Mobile Gait Monitor System Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Monitoring Gait and Powering Electronics. Energies 2021, 14, 4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Mahmood, M.; Kwon, S.; Maher, K.; Kang, J.W.; Yeo, W.-H. Wireless, Skin-Like Membrane Electronics with Multifunctional Ergonomic Sensors for Enhanced Pediatric Care. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 67, 2159–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodeheaver, N.; Herbert, R.; Kim, Y.-S.; Mahmood, M.; Kim, H.; Jeong, J.-W.; Yeo, W.-H. Strain-Isolating Materials and Interfacial Physics for Soft Wearable Bioelectronics and Wireless, Motion Artifact-Controlled Health Monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.; Luo, N.; Sun, F.; Venkatesan, H.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, Y. Ultrafast-Response/Recovery Flexible Piezoresistive Sensors with DNA-Like Double Helix Yarns for Epidermal Pulse Monitoring. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2104313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Xing, S.; Brandt, J.D.; Pan, T. Droplet-Based Interfacial Capacitive Sensing. Lab Chip 2012, 12, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Li, R.; Brandt, J.D.; Pan, T. Iontronic Microdroplet Array for Flexible Ultrasensitive Tactile Sensing. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.; Koo, J.H.; Nguyen, A.; Caves, J.M.; Kim, M.-G.; Chortos, A.; Kim, K.; Wang, P.J.; Tok, J.B.-H.; Bao, Z. Highly Skin-Conformal Microhairy Sensor for Pulse Signal Amplification. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Iranmanesh, E.; Li, W.; Ou, H.; Andrenko, A.S.; Wang, K. A Wearable Autonomous Heart Rate Sensor Based on Piezoelectric-Charge-Gated Thin-Film Transistor for Continuous Multi-Point Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2017 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 11–15 July 2017; pp. 3281–3284. [Google Scholar]

- Simões, J.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Non-Fullerene Acceptor Organic Photodetector for Skin-Conformable Photoplethysmography Applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempionatto, J.R.; Nakagawa, T.; Pavinatto, A.; Mensah, S.T.; Imani, S.; Mercier, P.; Wang, J. Eyeglasses Based Wireless Electrolyte and Metabolite Sensor Platform. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 1834–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3D Bioprinting for Fabricating Artificial Skin Tissue. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 208, 112041. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Han, H.; Naw, H.P.P.; Lammy, A.V.; Goh, C.H.; Boujday, S.; Steele, T.W.J. Real-Time Colorimetric Hydration Sensor for Sport Activities. Mater. Des. 2016, 90, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promphet, N.; Rattanawaleedirojn, P.; Siralertmukul, K.; Soatthiyanon, N.; Potiyaraj, P.; Thanawattano, C.; Hinestroza, J.P.; Rodthongkum, N. Non-Invasive Textile Based Colorimetric Sensor for the Simultaneous Detection of Sweat pH and Lactate. Talanta 2019, 192, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; He, J.; Chen, X.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, F.; Xia, Q.; Yu, L.; Lu, Z. A Wearable, Cotton Thread/Paper-Based Microfluidic Device Coupled with Smartphone for Sweat Glucose Sensing. Cellulose 2019, 26, 4553–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Yan, J.; Chu, H.; Wu, M.; Tu, Y. An Exercise Degree Monitoring Biosensor Based on Electrochemiluminescent Detection of Lactate in Sweat. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 143, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Ochoa, M.; Jiang, H.; Rahimi, R.; Ziaie, B. A Mass-Customizable Dermal Patch with Discrete Colorimetric Indicators for Personalized Sweat Rate Quantification. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2019, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Bandodkar, A.J.; Valdés-Ramírez, G.; Windmiller, J.R.; Yang, Z.; Ramírez, J.; Chan, G.; Wang, J. Electrochemical Tattoo Biosensors for Real-Time Noninvasive Lactate Monitoring in Human Perspiration. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 6553–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.-H.; Kim, D.; Chang, S.-Y.; Hur, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.-W.; Zhu, B.; Han, T.-H.; Choi, C.; Huffaker, D.L.; et al. Hybrid Integrated Photomedical Devices for Wearable Vital Sign Tracking. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 1582–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.M.; Jain, P.; Mohanty, S.P.; Agrawal, N. iGLU 2.0: A New Wearable for Accurate Non-Invasive Continuous Serum Glucose Measurement in IoMT Framework. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2020, 66, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Paz, E.; Barfidokht, A.; Rios, S.; Brown, C.; Chao, E.; Wang, J. Extended Noninvasive Glucose Monitoring in the Interstitial Fluid Using an Epidermal Biosensing Patch. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 12767–12775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Mason, A.J. Hardware Efficient Automatic Thresholding for NEO-Based Neural Spike Detection. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 64, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymourian, H.; Moonla, C.; Tehrani, F.; Vargas, E.; Aghavali, R.; Barfidokht, A.; Tangkuaram, T.; Mercier, P.P.; Dassau, E.; Wang, J. Microneedle-Based Detection of Ketone Bodies along with Glucose and Lactate: Toward Real-Time Continuous Interstitial Fluid Monitoring of Diabetic Ketosis and Ketoacidosis. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 2291–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Zou, C.; Wang, R.; Lai, X.; Yu, H.; Xu, K.; Li, D. A Continuous Glucose Monitoring Device by Graphene Modified Electrochemical Sensor in Microfluidic System. Biomicrofluidics 2016, 10, 011910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, M.R.; Madhav, K.V.; Krishna, E.H.; Komalla, N.R.; Reddy, K.A. A Novel Approach for Motion Artifact Reduction in PPG Signals Based on AS-LMS Adaptive Filter. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2012, 61, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Bian, G.-B.; Tian, Z. Removal of Artifacts from EEG Signals: A Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegan, R.; Nimi, W.S. On the Development of Low Power Wearable Devices for Assessment of Physiological Vital Parameters: A Systematic Review. J. Public Health 2024, 32, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.L. Self-Powered Sensing in Wearable Electronics─A Paradigm Shift Technology. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 12105–12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherazi, H.H.R.; Zorbas, D.; O’Flynn, B. A Comprehensive Survey on RF Energy Harvesting: Applications and Performance Determinants. Sensors 2022, 22, 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Replacing a Battery by a Nanogenerator with 20 V Output. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.-R.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Wang, Z.L. Flexible Triboelectric Generator. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Nanogenerators as New Energy Technology for Self-Powered Systems and as Active Mechanical and Chemical Sensors. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9533–9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Lin, L. Progress in Triboelectric Nanogenerators as a New Energy Technology and Self-Powered Sensors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2250–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, N.; Shi, B.; Zou, Y.; Xie, F.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Symbiotic Cardiac Pacemaker. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Hu, Q.; Hu, B.; Wang, Z.L.; Zhou, J. Fiber-Based Generator for Wearable Electronics and Mobile Medication. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 6273–6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Cho, H.; Park, K.T.; Kim, J.-S.; Park, M.; Kim, H.; Hong, Y.; Chung, S. High-Performance Compliant Thermoelectric Generators with Magnetically Self-Assembled Soft Heat Conductors for Self-Powered Wearable Electronics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenbrunner, M.; Adam, G.; Głowacki, E.D.; Drack, M.; Schwödiauer, R.; Leonat, L.; Apaydin, D.H.; Groiss, H.; Scharber, M.C.; White, M.S.; et al. Flexible High Power-per-Weight Perovskite Solar Cells with Chromium Oxide–Metal Contacts for Improved Stability in Air. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandodkar, A.J.; You, J.-M.; Kim, N.-H.; Gu, Y.; Kumar, R.; Mohan, A.M.V.; Kurniawan, J.; Imani, S.; Nakagawa, T.; Parish, B.; et al. Soft, Stretchable, High Power Density Electronic Skin-Based Biofuel Cells for Scavenging Energy from Human Sweat. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandodkar, A.J.; Gutruf, P.; Choi, J.; Lee, K.; Sekine, Y.; Reeder, J.T.; Jeang, W.J.; Aranyosi, A.J.; Lee, S.P.; Model, J.B.; et al. Battery-Free, Skin-Interfaced Microfluidic/Electronic Systems for Simultaneous Electrochemical, Colorimetric, and Volumetric Analysis of Sweat. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, F.; Gong, H.; Wei, F.; Zhuang, J.; Karshalev, E.; Esteban-Fernández de Ávila, B.; Huang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. Enzyme-Powered Janus Platelet Cell Robots for Active and Targeted Drug Delivery. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eaba6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.L. Nanowire Structured Hybrid Cell for Concurrently Scavenging Solar and Mechanical Energies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5866–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, V.; Yang, X.; Xiong, Z.; Li, R.R.; Yao, H.; Godaba, H.; Obuobi, S.; Singh, P.; Guan, X.; Tian, X.; et al. Wirelessly Operated Bioelectronic Sutures for the Monitoring of Deep Surgical Wounds. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverå Ejneby, M.; Jakešová, M.; Ferrero, J.J.; Migliaccio, L.; Sahalianov, I.; Zhao, Z.; Berggren, M.; Khodagholy, D.; Đerek, V.; Gelinas, J.N.; et al. Chronic Electrical Stimulation of Peripheral Nerves via Deep-Red Light Transduced by an Implanted Organic Photocapacitor. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Suh, J.M.; Shin, J.; Liu, Y.; Yeon, H.; Qiao, K.; Kum, H.S.; Kim, C.; Lee, H.E.; Choi, C.; et al. Chip-Less Wireless Electronic Skins by Remote Epitaxial Freestanding Compound Semiconductors. Science 2022, 377, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodheli, O.; Lagunas, E.; Maturo, N.; Sharma, S.K.; Shankar, B.; Montoya, J.F.M.; Duncan, J.C.M.; Spano, D.; Chatzinotas, S.; Kisseleff, S.; et al. Satellite Communications in the New Space Era: A Survey and Future Challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 70–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakano, T.; Kotabe, S.; Komukai, T.; Kumagai, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Takahara, A.; Ngo, T.; Fadlullah, Z.M.; Nishiyama, H.; Kato, N. Bringing Movable and Deployable Networks to Disaster Areas: Development and Field Test of MDRU. IEEE Netw. 2016, 30, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozza, M.; Rao, A.; Flinck, H.; Tarkoma, S. Network-In-a-Box: A Survey About On-Demand Flexible Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 2407–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review and Implementation of Resilient Public Safety Networks: 5G, IoT, and Emerging Technologies. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9387696 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Ganesh, S.; Gopalasamy, V.; Sai Shibu, N.B. Architecture for Drone Assisted Emergency Ad-Hoc Network for Disaster Rescue Operations. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on COMmunication Systems & NETworkS (COMSNETS), Bangalore, India, 5–9 January 2021; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Deepak, G.C.; Ladas, A.; Politis, C. Robust Device-to-Device 5G Cellular Communication in the Post-Disaster Scenario. In Proceedings of the 2019 16th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–14 January 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Deepak, G.C.; Ladas, A.; Sambo, Y.A.; Pervaiz, H.; Politis, C.; Imran, M.A. An Overview of Post-Disaster Emergency Communication Systems in the Future Networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2019, 26, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard for a Smart Transducer Interface for Sensors and Actuator—Wireless Communication Protocols and Transducer Electronic Data Sheet (TEDS) Formats—LoRa Protocol. Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/ieee/1451.5.5/10611/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- IEEE 802.11, The Working Group Setting the Standards for Wireless LANs. Available online: https://www.ieee802.org/11/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Collotta, M.; Pau, G.; Talty, T.; Tonguz, O.K. Bluetooth 5: A Concrete Step Forward toward the IoT. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaric, S.; Malaric, K. ZigBee Wireless Standard. In Proceedings of the ELMAR 2006, Zadar, Croatia, 7–9 June 2006; pp. 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Shafi, M.; Molisch, A.F.; Smith, P.J.; Haustein, T.; Zhu, P.; De Silva, P.; Tufvesson, F.; Benjebbour, A.; Wunder, G. 5G: A Tutorial Overview of Standards, Trials, Challenges, Deployment, and Practice. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2017, 35, 1201–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdelj, M.; Natalizio, E. UAV-Assisted Disaster Management: Applications and Open Issues. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Kauai, HI, USA, 11–15 February 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bushnaq, O.M.; Mishra, D.; Natalizio, E.; Akyildiz, I.F. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for Disaster Management. In Nanotechnology-Based Smart Remote Sensing Networks for Disaster Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 159–188. [Google Scholar]