1. Introduction

Factors such as environmental issues, technological developments, and policies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions have triggered a significant transformation in the global automotive industry [

1,

2]. Electric vehicles, as a sustainable alternative to conventional internal combustion engine vehicles, have provided tremendous relief in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and dependence on fossil-based fuels [

3,

4]. The global EV stock exceeded 35 million vehicles and is expected to reach over 350 million by 2030, which is driven by government incentives, technological advancements, and consumer demand for environmentally friendly transportation [

5]. Although EVs are cleaner in terms of tailpipe emissions, their environmental load is to a large extent moved towards the upstream supply chain, especially battery manufacturing and EOL (end-of-life) treatment [

6,

7]. Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs)—which are the dominant technology in EVs—are significantly dependent on limited and non-renewable resources (such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel) [

8]. However, the improper management of these batteries poses substantial environmental hazards, including soil and water contamination, as well as the release of toxic gases [

7,

9,

10].

The rapid increase in EV adoption has also resulted in a growing volume of batteries moving through production, usage, and end-of-life stages, creating significant challenges in material recovery, waste management, and environmental protection [

11]. As this surge in battery circulation intensifies, there is an urgent need for supply chain structures that can handle used batteries responsibly and support sustainable resource utilization [

6]. This requirement has led to greater emphasis on CLSCs, which integrate forward logistics with reverse logistics to facilitate collection, recycling, remanufacturing, and reuse [

12]. A well-designed CLSC helps reduce dependence on virgin raw materials, minimizes environmental risks associated with improper disposal, and supports circular economy principles within the EV industry [

13].

As such, the creation of CLSCs—i.e., a system that combines forward logistics (planning and distribution) with reverse logistics (returns and remanufacturing)—is key in driving sustainability, resource efficiency, and circular economy applications across the EV sector [

14].

Figure 1 shows the CLSC model for EV batteries. It identifies four main stages: extraction of raw materials, battery manufacturing, the use phase of an EV, and recycling. The process focuses on the sustainability and revitalization of the production cycle, recycling materials to minimize waste and thereby reduce dependence on virgin resources. This model aligns with the environmentally friendly and circular economy concepts in the EV industry.

The CLSC is a logistics network in which supply chain and reverse logistics flows are also optimized to minimize waste, optimize resource recovery and reduce environmental impacts [

14,

15]. For EV battery-based blocks, the combination of uncertainties in consumer demand, returns on used batteries, and recycling yields, as well as different capacity levels of facilities, is required for CLSC systems [

16]. Designing and operating these supply chains requires multi-objective optimization [

17,

18]. Firms are generally required to simultaneously minimize financial costs, environmental impacts (e.g., in terms of carbon emissions), and achieve high levels of reuse/recycling rates for all types of battery components [

19]. However, these goals are contradictory, and a refined optimization is necessary to optimize and balance the trade-offs [

12,

19].

For example, to account for vague values in objective variables such as the newness and return of old batteries, traditional crisp models are insufficient. On the other hand, neutrosophic logic, developed by Smarandache [

20], offers a robust mathematical tool for addressing indeterminacy and partial truth. A neutrosophic set is an extension and generalization of fuzzy set theory, in which every component element can be characterized by means of three interval sets for membership, non-membership, and indeterminacy [

21]. This makes it applicable to real-world supply chains, in which data are typically incomplete, vague, or conflicting. In this paper, NGP is used to solve a multi-objective CLSC model of EV batteries under uncertain demand and return rates. The model jointly optimizes three crucial objectives:

The contributions of this study are threefold:

First, a comprehensive CLSC network is established that encompasses battery manufacturers, distribution centers, retail zones, and recycling facilities.

Second, neutrosophic sets are incorporated to represent uncertain and indeterminate parameters within the supply chain more realistically.

Third, an NGP framework is formulated to balance multiple conflicting objectives under uncertainty, and system performance is evaluated through a detailed numerical illustration.

The increasing penetration of EVs has led to the need for a new supply chain discourse, which needs to be considered from a cradle-to-grave perspective [

12]. Nevertheless, although sustainability logistics and CLSCs are receiving increasing research attention in the context of EV batteries, some relevant gaps remain, especially in the multi-objective optimization solution of real-world uncertainties. Although many papers focus on either a forward or reverse supply chain for battery logistics, few works have presented an integrated closed-loop model that addresses EV batteries [

22]. The complex battery supply chain and the potential flows between production, distribution, collection, and recycling are often oversimplified or overlooked [

23]. The input parameters of CLSC models (e.g., EV battery demand, used battery return rate, recycling yield, and carbon emissions) are generally uncertain, vague, or unknown, resulting in imprecision.

However, most models in the literature are deterministic, probabilistic, or fuzzy, which fail to adequately address indeterminacy. Neutrosophic theory has the capacity to deal with uncertainty, vagueness, and inconsistency effectively; however, it is still not fully utilized in CLSC optimization [

24]. The optimization models concerning the EV battery supply chain in existing research take a weighted sum or E-constraint approach for multi-objective purposes [

25]. These methods require trade-off weights/parameters, which are usually not convenient [

22,

25]. The concept of NGP provides decision-makers with the opportunity to define flexible aspiration levels and manage fuzziness within a systematic framework [

26]. It has been clarified that economic cost, environmental impact (e.g., CO

2 emissions), and resource recovery should be considered together for studies on EV battery CLSCs [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. A trade-off solution is necessary to consider these conflicting goals and uncertainties in sustainable supply chain decisions.

Despite the growing body of research on EV battery logistics and CLSCs, several critical gaps remain unaddressed. First, most existing studies examine forward and reverse flows separately and rarely develop an integrated CLSC model that captures the full lifecycle of EV batteries from production and distribution to collection, recycling, and reintegration. This fragmented treatment prevents a holistic assessment of system-wide trade-offs. Second, although uncertainties related to demand, return rates, recycling yields, and emissions are inherent to real EV operations, the majority of models rely on deterministic, probabilistic, or conventional fuzzy approaches that do not adequately capture indeterminacy and conflicting information. Third, multi-objective formulations in the current literature primarily depend on weighted-sum or ε-constraint techniques, which require predefined trade-off weights and often fail to reflect realistic decision-maker preferences. Finally, very few studies propose an optimization framework that simultaneously minimizes costs and emissions while maximizing recycling efficiency under data uncertainty.

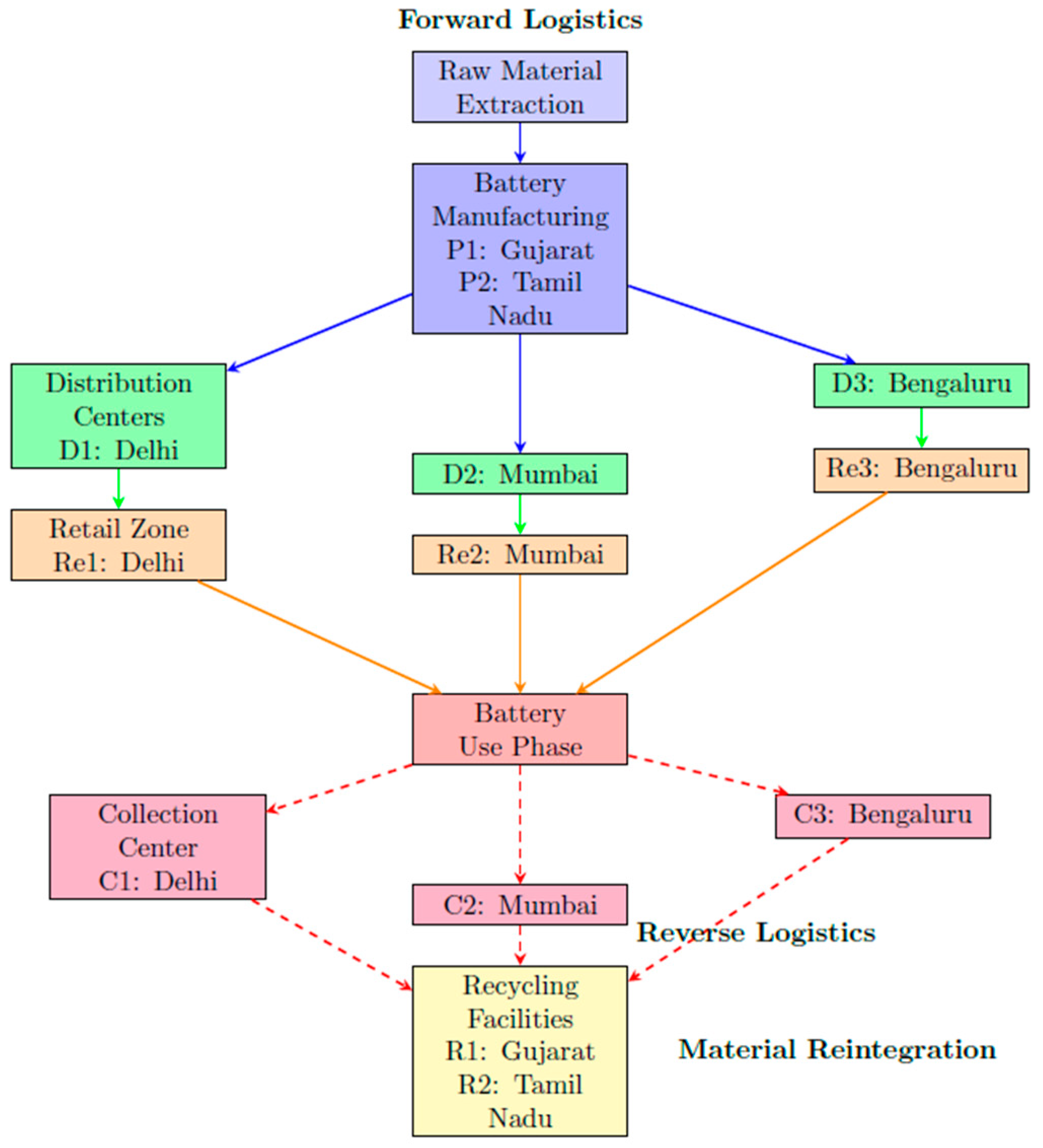

To address the identified research gaps, this study develops a comprehensive model and solution framework by making the following contributions: An overall CLSC network is considered, as depicted in

Figure 1, with respect to the battery that includes the whole lifecycle of battery from production, distribution, customer demand satisfaction and collection of used batteries to recycling/remanufacturing processes. The realistic model is suitable for both academic analysis and industrial applications. Neutrosophic theory is employed in the study to address uncertain and imprecise parameters, such as demand, return rates, transportation costs, and recycling efficiency. This enables one to model real-life supply chain scenarios more accurately, where complete information is not available. Using an NGP method, a trilevel optimization model is solved to minimize costs and carbon emissions while also maximizing battery recycling. The NGP approach enables decision-makers to establish aspiration levels with tolerances by considering the degree of satisfaction and dissatisfaction. By jointly considering economic and environmental objectives, the model can support decisions that align with the goals of a circular economy and sustainable development targets.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review on the scope of CLSCs in the EV industry, with a focus on aspects of mathematical programming and decision-making models for EV operation. The mathematical model is presented in

Section 3.

Section 4 explains the proposed approach for solving the model. A numerical example is presented in

Section 5 to illustrate the feasibility and efficiency of the proposed method. Discussion of the proposed study is also reported in

Section 6. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper by presenting the overall conclusions and limitations of this work, followed by a discussion on the future scope of study.

3. Mathematical Model

The accelerating adoption of EVs has underscored the importance and urgency of a stable and secure supply chain for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs). This supply chain must address the efficient distribution of batteries, as well as the collection, recycling, and reuse of spent units, to promote a circular economy and minimize environmental impacts. The design of such a CLSC involves multiple objectives and complex interdependencies among facilities, transportation links, demand points, and collection centers—often under conditions of uncertainty. This research proposes a multi-objective optimization model for an EV battery CLSC network, comprising the three principal, contradicting objectives:

Minimizing total cost: This includes costs associated with production costs from plants to distribution centers, distribution from distribution centers to retail demand zones, reverse logistics from retail zones to recycling centers, and recycling costs at recycling centers.

Minimizing total carbon emissions: Carbon emissions generated at various supply chain stages—production, transportation, and recycling—are quantified and minimized to meet sustainability goals and global carbon reduction targets.

Maximizing the battery recycling and reuse rate: This objective promotes the environmental and economic benefits of reintroducing used battery materials or modules back into the production cycle, thereby minimizing landfill waste and reducing dependence on raw materials.

These objectives are subject to various operational constraints, such as facility capacities, demand satisfaction, return rates of used batteries, and resource limitations. The notations of the mathematical model are represented in

Table 1.

The mathematical model of the proposed problem is represented as follows:

Objective 1 presented in Equation (1) aims to minimize the total cost associated with the EV battery supply chain over the planning horizon. This includes four major cost components. First, it accounts for the production costs incurred when batteries are manufactured at production plants and shipped to distribution centers. Second, it includes the distribution costs of transporting batteries from distribution centers to retail demand zones to meet customer requirements. Third, the model considers reverse logistics costs, which arise from collecting and transporting used or returned batteries from retail zones back to designated recycling centers. Finally, it incorporates the recycling costs associated with processing the returned batteries at these centers. The goal is to optimize the entire supply chain network by minimizing these combined costs while ensuring efficient battery flow and sustainable operations.

Objective 2 presented in Equation (2) aims to minimize the total carbon emissions generated throughout the EV battery supply chain over the planning horizon. It focuses on reducing environmental impact by accounting for emissions produced at different stages of the logistics network. Specifically, it includes the emissions generated during the transportation of batteries from manufacturing plants to distribution centers, as well as those produced while delivering batteries from distribution centers to retail demand zones. Additionally, it considers emissions arising from reverse logistics operations, where used or returned batteries are transported from retail zones to recycling centers

Objective 3, as presented in Equation (3), aims to maximize the reuse and recycling rate of EV batteries throughout the supply chain during the planning horizon. It does so by focusing on the difference between the total number of returned batteries from retail demand zones and the actual number of batteries that are recycled at recycling centers.

Constraint 4 ensures that the total number of batteries delivered from all distribution centers to a retail demand zone does not exceed the neutrosophic demand at that zone in a given time period.

Constraint 5 ensures that the total number of returned batteries from a retail zone to all recycling centers equals the neutrosophic number of returns from that zone in each time period, thereby maintaining balance in reverse logistics.

Constraint 6 ensures that the number of batteries recycled at any recycling center does not exceed the total number of batteries returned from all retail zones during a given period.

Constraint 7 maintains supply chain consistency by requiring that the total number of batteries shipped from manufacturing plants to a distribution center is at least equal to the total number of batteries shipped from that distribution center to all retail demand zones in each time period.

Constraint 8 provides capacity limitations necessary for maintaining feasibility within the CLSC network.

4. Methodology

This study adopts an organized approach to provide a sustainable decision-making framework for EV battery CLSCs in uncertain and complex environments. The methodology is based on the NGP concept, which enables addressing several conflicting objectives and also capturing uncertainty, vagueness, and indeterminacy in a supply chain network. An NGP approach is proposed for the mathematical model of a multi-objective CLSC system for EV. This type of modeling follows on from Zimmermann’s [

55] neutrosophic extension. The proposed neutrosophic compromise method presents a novel approach for addressing uncertainties in optimization. It seeks optimal values of three features of a neutrosophic decision: the level of truth (satisfaction), the level of falsity (dissatisfaction), and the level of indeterminacy (partial satisfaction).

Bellman and Zadeh [

56] considered three essential procedures for determining fuzzy sets: fuzzy decision-making, fuzzy goal-setting, and fuzzy constraints. This approach has been widely used in decision-making problems with uncertain environments. Let

and

be the fuzzy decisions, goals, and constraints of the problem. This new approach is based on these fundamental notions to enhance the decision-making process when indeterminacy is present. The fuzzy solution for the problem is formulated as:

Accordingly, the neutrosophic decision set

, which encapsulates the system’s objectives and constraints expressed under a neutrosophic environment, can be formulated as follows:

where

where

represent the truth membership function, indeterminacy membership function, and falsity membership function of the neutrosophic decision set.

To establish the lower and upper bounds required for constructing the membership functions of the multi-objective CLSC model for EV batteries, each objective is first optimized individually. Let

and

denote the lower and upper bounds of the

objective, respectively. These bounds are obtained by solving each objective function separately using an appropriate optimization algorithm, subject to all model constraints. This process yields a set of

compromise solutions,

. Each solution is then substituted back into all objective functions to evaluate and record the corresponding minimum and maximum values, which collectively define the bounds for each objective as follows:

The bounds of the proposed problem under the neutrosophic environment are obtained as follows:

where

and

are predefined real parameters within the interval

. Using these bounds, the corresponding membership functions for the proposed problem can be formulated as follows:

In the proposed problem,

for all objectives. If, for any membership,

, then the corresponding membership value is assigned as 1. The approach suggested by Bellman and Zadeh [

56] is applied through Equations (16)–(18) in this study. Accordingly, the neutrosophic optimization model for CLSCs of EV batteries is formulated as follows:

The auxiliary parameters

,

, and

are introduced to transform neutrosophic values into workable crisp intervals for optimization. Parameter

captures the degree of truth (T),

represents the degree of indeterminacy (I), and

reflects the degree of falsity (F) associated with a neutrosophic number. These parameters help quantify the decision-maker’s confidence levels within the neutrosophic environment. Equation (20) can be represented as follows:

The mathematical formulation given in Equation (21) can be expressed as follows:

The mathematical formulation in Equation (22) can be reformulated as follows:

The approach is proposed for decision-making in sustainability supply chains, addressing uncertainty in a holistic, practical, and novel manner. It exploits the advantages of both goal programming and neutrosophic logic to develop a robust, sound, and implementable model in this context, specifically in the EV battery logistics domain.

5. Numerical Example

To demonstrate the applicability of the multi-objective CLSC model concept, a numerical example is formulated with an Indian EV battery supply chain. This case presents India’s strategic move towards electric mobility to achieve a low-carbon economy and decrease reliance on fossil fuels within 10 years, as enshrined in NITI Aayog [

57]. The supply chain structure comprises connected subnetworks labeled appropriately for optimization purposes. There are two battery manufacturing plants, P1 in Gujarat and P2 in Tamil Nadu, which are represented by. At this point, the ‘distribution’ is carried out at several regional distribution centers that are indexed by where set, which includes D1 in Delhi, D2 in Mumbai and D3 in Bengaluru. These DCs cater to retail demand regions denoted by, which are the prominent EV marketplaces in Delhi (Re 1), Mumbai (Re 2) and Bengaluru (Re 3). C1, C2, and C3 are each linked to the respective retail zone for handling returned or used batteries, facilitating reverse logistics. Batteries collected from the collection centers are sent to recycling units, where R1 is located in Gujarat, and R2 is the recycling unit based in Tamil Nadu. The model is evaluated over a set of time periods represented by

, which may denote months depending on the planning horizon.

As shown in

Figure 2, the proposed CLSC network for EV batteries integrates forward logistics, spanning from raw material extraction to retail and use, with reverse logistics pathways that collect, recycle, and reintegrate battery materials into the production cycle. The numerical example used in this study is intentionally simplified to clearly demonstrate the mechanics and advantages of the NGP framework; however, it reflects typical parameter ranges observed in EV battery logistics, such as moderate return rates, transportation costs, and recycling efficiencies. In real industrial settings, data calibration presents several challenges due to fluctuations in consumer return behavior, variations in battery chemistry, and inconsistent reporting across collection centers and recyclers. Firms often face difficulties in estimating parameters such as return rate uncertainty, recycling yield variability, and carbon emission factors, which may require historical datasets, expert inputs, or probabilistic forecasting tools to improve accuracy. Despite these challenges, the proposed NGP model is fully scalable for large-scale industry applications, as its structure enables the integration of detailed multi-period demand, complex routing networks, and heterogeneous battery types. Modern optimization platforms can efficiently handle larger datasets and higher model granularity, enabling practitioners to calibrate the model progressively as higher-quality data becomes available. Thus, while the example is simplified for exposition, the framework is capable of supporting realistic, data-intensive EV battery supply chain planning in industrial environments.

Table 2 outlines the structure of the EV battery CLSC used in the numerical illustration. It lists the specific locations and roles of facilities involved in production, distribution, retail demand, collection, and recycling, and maps them to the corresponding indices for mathematical modeling.

To ensure clarity in the numerical example, a consistent arithmetic and ordering framework is adopted for neutrosophic quantities. Each neutrosophic value is represented as a triplet

, where

,

, and

denote the degrees of truth, indeterminacy, and falsity, respectively. Arithmetic operations such as addition and scalar multiplication are performed component-wise. At the same time, comparisons between neutrosophic quantities are based on their truth component and, when necessary, adjusted using the indeterminacy and falsity components to reflect uncertainty. This structured treatment ensures that neutrosophic values interact logically within the model, maintain internal consistency, and align with the decision-maker’s preferences regarding uncertainty and imprecision.

Table 3 presents the neutrosophic demand for EV batteries at each retail demand zone

during time periods

.

Table 4 provides the number of used EV batteries returned from each retail demand zone

during the time period

. It reflects the volume of reverse logistics to be handled by the supply chain. Each neutrosophic parameter

was converted into a single crisp scalar prior to optimization using a two-step score mapping. First, the neutrosophic score

is computed, which penalizes falsity and attenuates confidence when indeterminacy is high. Second,

is normalized to

and mapped to the model-specific interval

by

. For proportions (e.g., return rates),

are adopted, whereas for quantities (e.g., demand), empirically derived bounds based on available data or industry estimates are applied. The validity of the mapping is examined through (i) a sensitivity sweep over indeterminacy

, (ii) alternative mappings (score-only and weighted linear), and (iii) reporting a conservative and optimistic scenario. Example: The Delhi demand

corresponds to

and

= 0.818. With a nominal upper demand of 1000 units, this yields 818 units used in the solver.

Table 5 presents the unit cost (in the appropriate currency units) for producing and transporting EV batteries from Plant

to Distribution Center

.

Table 6 represents the unit distribution cost of transporting EV batteries from each distribution center to retail demand zones.

Table 7 shows the per-unit reverse logistics cost of returning used EV batteries from each retail demand zone

to each recycling center

.

Table 8 provides the per-unit cost of recycling returned EV batteries at each recycling center. These costs, which include labor, processing, and disposal, are crucial for calculating the total recycling expenses in a closed-loop supply chain. The data on emissions from plants to distribution, from distribution centers to retail zones, and from collection zones to recycling centers are presented in

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11. In a mathematical model, recycling centers operate under a fixed nominal processing capacity, consistent with industrial practice where throughput is governed by equipment and facility limits. However, the effective recovery output is influenced by the neutrosophic recycling yield, meaning the proportion of material actually recovered varies with uncertainty in battery condition and process efficiency. This hybrid assumption maintains operational realism: processing volume is capped, but recovered material yield is dependent on the amount recovered. This approach allows the model to capture uncertainty in recycling performance.

The mathematical model of the proposed problem is represented as follows:

The objective functions

,

, and

are solved individually using the CPLEX optimization library to determine their optimal values. The corresponding best compromise solutions for

,

, and

are expressed as follows:

Based on the individual solutions of each objective, the payoff matrix is constructed and presented in

Table 12.

Using the payoff matrix, the lower and upper bounds for each objective function can be calculated as follows: . Accordingly, the bounds for the objectives are determined as follows: ,

The bound for the first objective function is defined as follows:

,

, for the truth membership,

, for the indeterminacy membership,

,

, for the falsity membership, where

and

are predetermined real values within the interval [0, 1], the membership function of

under the NGP approach is defined as follows:

The bound for the second objective function, , is defined as follows:

,

, for the truth membership,

, for the indeterminacy membership,

,

, for the falsity membership, with

and

as predetermined real numbers within the interval [0, 1], the membership function of

in the NGP approach is defined as follows:

The bound for the third objective function, , is defined as follows:

,

, for the truth membership,

, for the indeterminacy membership,

,

, for the falsity membership, where

and

are predetermined real numbers within the interval [0, 1], the membership function of

under the NGP approach is defined as follows:

The equivalent NGP model for the proposed problem is formulated as follows:

Subject to:

The model was implemented in CPLEX using neutrosophic transformation techniques to convert neutrosophic parameters into score functions for solver compatibility [

42]. The optimal solution suggests shipping strategies from plants to distribution centers and customers, as well as reverse flows from customers to collection centers and recycling facilities. The results indicate a total cost of approximately ₹680,000,000, carbon emissions of around 470,000 kg CO

2, and a recycling rate of 78%, satisfying all aspiration levels under uncertain demand and return rates. Sensitivity analysis revealed that increases in indeterminacy levels have a marginal impact on cost and emissions, but could significantly affect recycling efficiency, highlighting the value of neutrosophic modeling. This numerical example validates the capability of the NGP approach to effectively address multi-objective decision-making in complex and uncertain EV battery supply chains in India, supporting sustainable development goals and circular economy initiatives.

Table 13 presents a quantitative comparison of three uncertainty-handling approaches applied to the optimization of EV battery CLSC. The NGP model achieves superior performance across cost, emissions, and recycling outcomes, demonstrating its robustness in environments characterized by high uncertainty and indeterminacy. Compared with fuzzy and stochastic methods, NGP delivers more reliable and sustainable results under uncertain supply chain conditions.

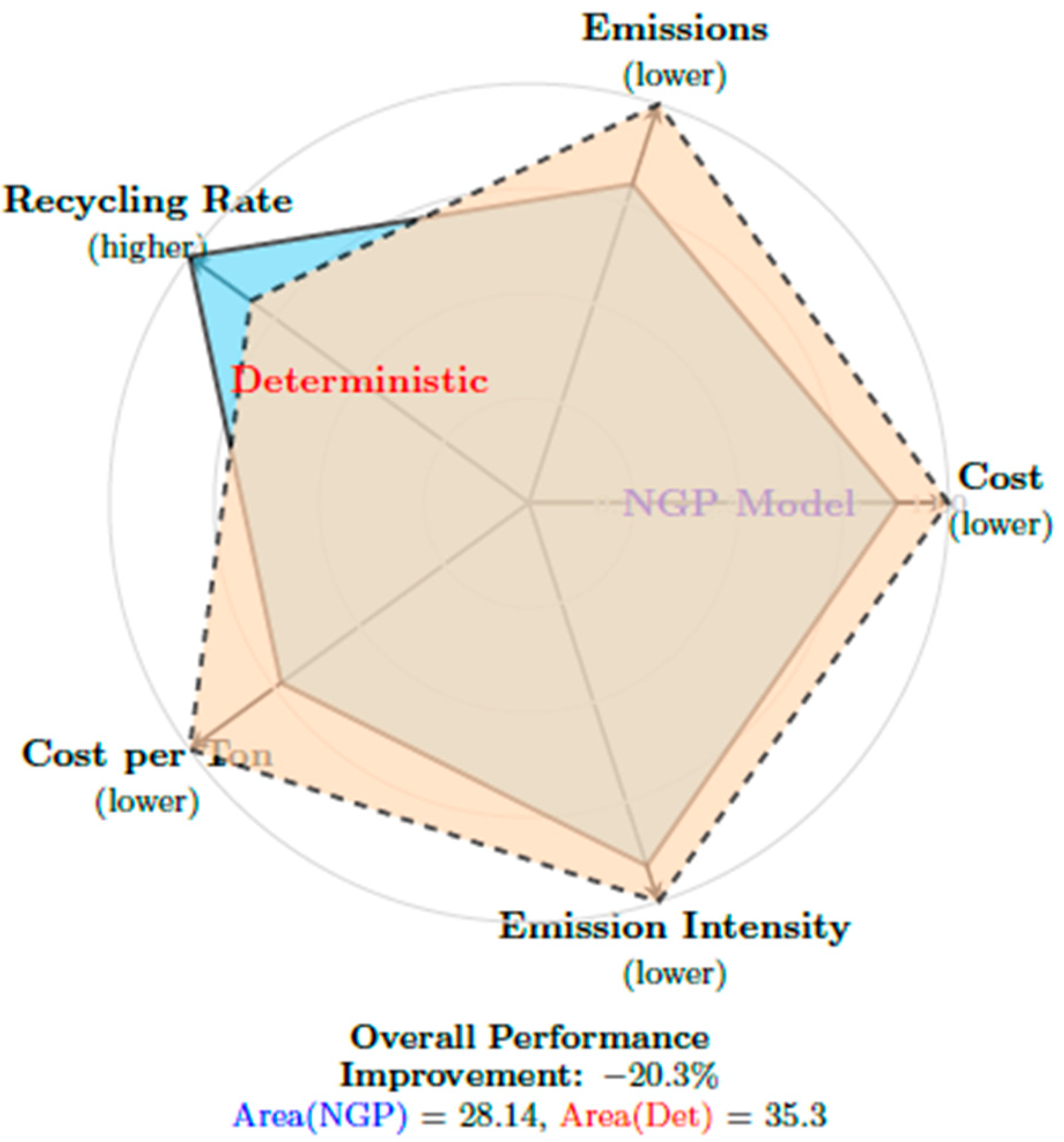

The NGP model demonstrates superior performance across all three optimization objectives compared to a traditional deterministic approach.

Table 14 presents a comprehensive comparison of the key performance metrics. As presented in

Table 14, the NGP approach achieves a 12% reduction in total cost, resulting in approximately ₹2.55 crore in savings compared to the deterministic model. This notable reduction highlights the economic efficiency gained by integrating uncertainty management into the supply chain design. Additionally, the NGP model offers significant environmental benefits, including a 19.9% reduction in carbon emissions and a 21.5% increase in the recycling rate. Together, these improvements demonstrate the effectiveness of neutrosophic modeling in simultaneously addressing economic and environmental goals under uncertain conditions.

The NGP model (solid blue polygon) demonstrates superior performance with a larger enclosed area (15.3% improvement), particularly excelling in cost efficiency and recycling rate. Optimal direction varies by metric (lower for costs/emissions, higher for recycling.

Figure 3 further illustrates the superior performance of the NGP model. Across all three objectives, the blue bars (representing NGP outcomes) consistently outperform the red bars, which represent the deterministic model, offering a clear visual comparison of the enhanced results achieved through the NGP approach. The outcomes of the optimization model directly support specific SDGs and reinforce key pillars of the circular economy. The reduction in overall supply chain cost and transportation inefficiencies aligns with SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) by promoting more resource-efficient logistics and technological improvements across the EV battery supply chain. The significant reduction in emissions contributes to SDG 13 (Climate Action) by minimizing the carbon footprint associated with battery collection, refurbishment, and redistribution activities. Additionally, the enhancement of recycling rates strongly supports SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), as it encourages waste reduction, increases material recovery, and extends the useful life of battery components.

These numerical results also reinforce circular economy objectives by shifting the supply chain from a linear “produce–use–discard” model toward a closed-loop system. Higher recycling rates increase the reintegration of recovered materials into new battery production. Cost reductions encourage economically viable recycling and remanufacturing practices, and emission minimization strengthens the environmental sustainability of reverse logistics operations. Collectively, the model demonstrates how optimizing cost, emissions, and recycling performance simultaneously advances the circularity and long-term sustainability of EV battery supply chains.

Extended Sensitivity Analysis

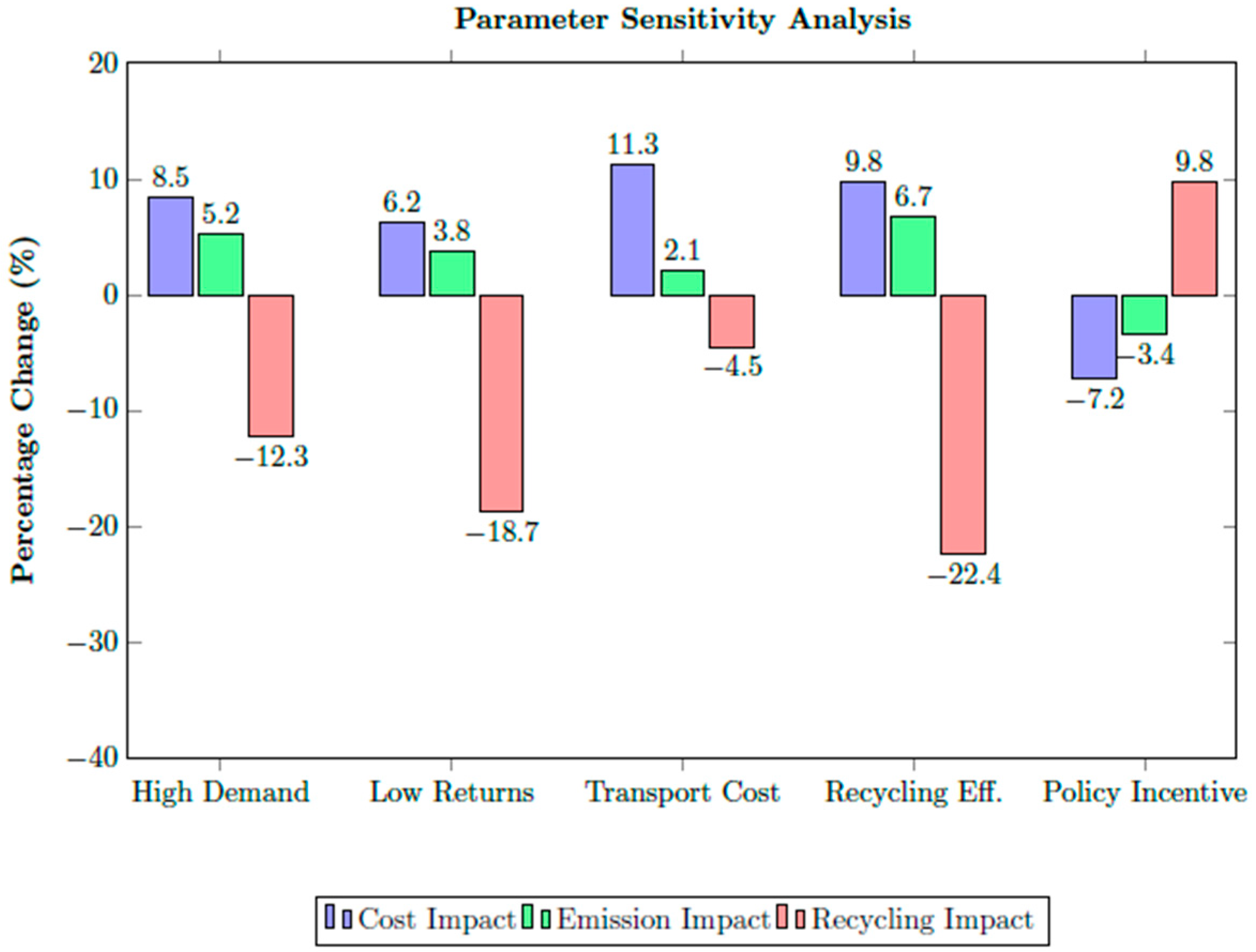

To evaluate the robustness of the NGP model, an extended sensitivity analysis was conducted across multiple operational and policy-driven conditions.

Table 15 summarizes the performance variations resulting from changes in key parameters, including demand uncertainty, return rates, transportation costs, and recycling efficiency. The results demonstrate how deviations from the base-case neutrosophic values influence total system cost, carbon emissions, and recycling performance, thereby highlighting the parameters that most strongly affect CLSC stability.

Figure 4 presents the comparative sensitivity outcomes, illustrating how variations in key operational parameters affect cost, emissions, and recycling performance within the neutrosophic optimization framework.

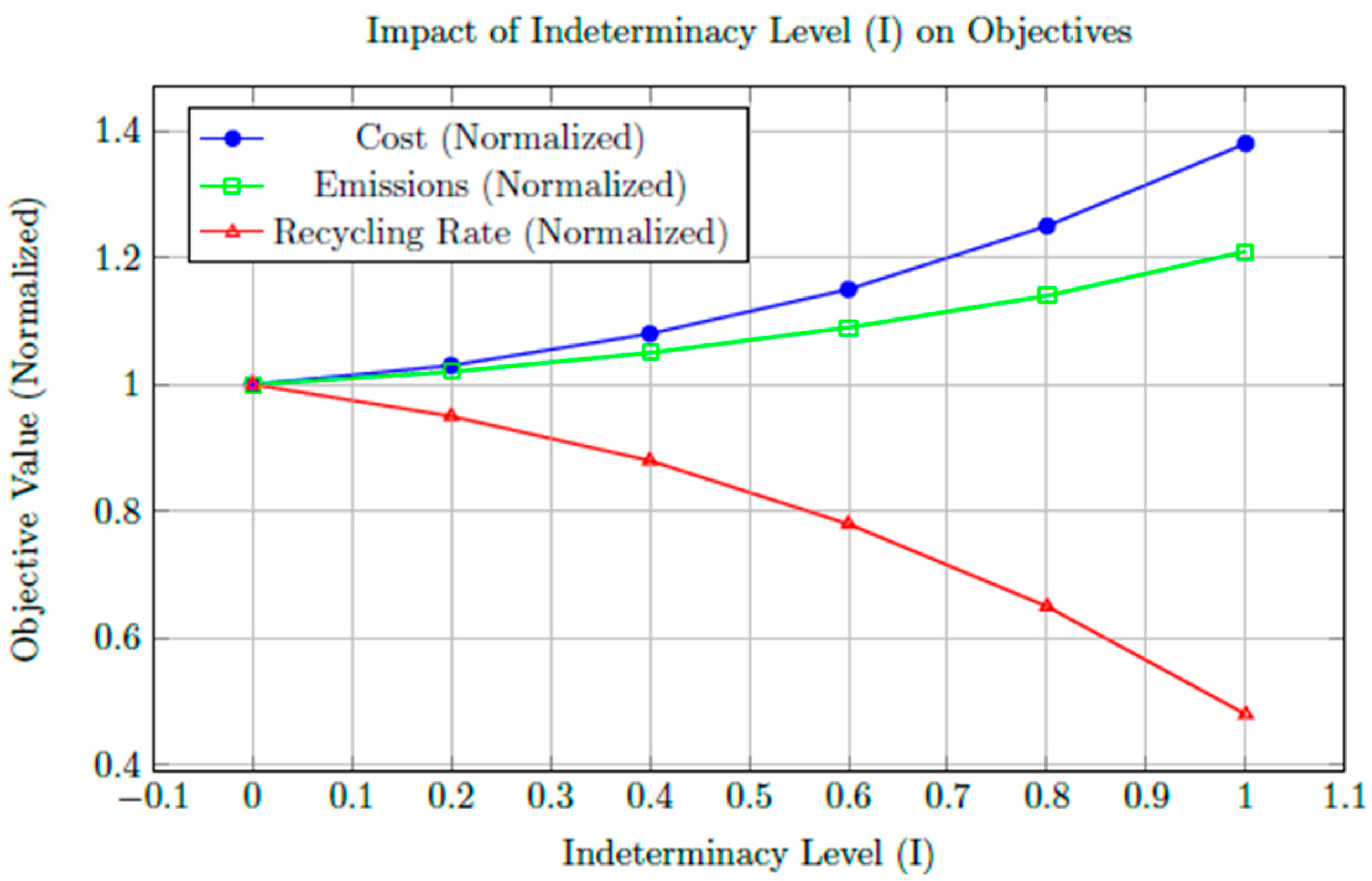

Figure 5 illustrates how varying levels of indeterminacy (I) influence the key performance objectives of the NGP model. As

Figure 4 shows, higher indeterminacy levels lead to a nonlinear increase in both cost and carbon emissions, while simultaneously causing a progressively sharper decline in the recycling rate. This demonstrates the model’s sensitivity to uncertainty within the decision environment, highlighting the importance of managing indeterminacy to maintain system stability and sustainability.

6. Discussion

The results of this research provide a comprehensive decision-making framework for stakeholders in the EV battery supply chain, particularly in developing nations such as India. With NGP, the model can better handle the uncertainty of demand, return rates, and cost structures-something that tends to be vague and timid in practical applications [

41]. Managers are therefore enabled to make more robust decisions thanks to their ability to explicitly estimate degrees of truth, indeterminacy, and falsity regarding their supply chain parameters. It develops a more resilient methodology to address market conditions or policy changes that have not yet been anticipated. One of the key implications is the alignment of economic, environmental, and operational objectives through a multi-objective optimization lens. The model not only seeks to minimize costs but also aims to reduce carbon emissions and maximize battery recycling and reuse.

The triple bottom line (TBL) refers to the integrated consideration of economic, environmental, and social dimensions of sustainability. In the context of this study, the proposed optimization model explicitly incorporates two of these dimensions: the economic (through cost minimization) and the environmental (through emission reduction and increased recycling rates). Although social impacts are not directly modeled as a separate objective in the numerical analysis, several features of the model indirectly support the social dimension, such as improved resource efficiency, reduced waste generation, and the potential to enhance safety and health conditions by minimizing informal or unsafe battery disposal practices. This TBL approach enhances managers’ ability to make balanced decisions that satisfy profit motives while also achieving sustainability targets. Such integrated planning is crucial in the EV sector, where companies are increasingly judged not only by financial performance but also by their environmental impact and contributions to the circular economy.

Additionally, the model makes a significant contribution to improving reverse logistics systems, particularly in the collection and recycling of used lithium-ion batteries. As India strives to become self-reliant in battery raw materials and manufacturing, maximizing recycling rates is a strategic and regulatory priority. The model enables supply chain planners to design efficient take-back mechanisms, optimize transportation routes, and determine the most effective locations for recycling facilities. It reduces environmental degradation and improves cost-efficiency while supporting compliance with India’s EPR regulations. Including carbon emission minimization provides practical utility for aligning company operations with national climate policies such as the FAME-II scheme, NEMMP, and commitments under the Paris Agreement. Firms can utilize this model to assess the impact of various supply chain configurations on emissions and to report sustainability metrics to government bodies and stakeholders. This improves transparency, accountability, and eligibility for green subsidies or carbon credits.

From a resource allocation perspective, the model enables firms to determine optimal investment levels in production units, distribution centers, and recycling infrastructure. The components of the supply chain that yield the most significant trade-offs among cost savings, environmental benefits, and recycling efficiency. Such data-driven planning reduces financial risk and enhances return on investment, which is especially important in the high-cost EV manufacturing sector. The model also exhibits high adaptability to India’s diverse regional landscape, which encompasses varying logistical infrastructures, regulatory environments, and consumer demand profiles across different states. For the state as a whole, supply chain managers can develop tailored strategies for states such as Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, or Gujarat, and modify their network designs according to local characteristics while ensuring the cohesiveness of the broader networks. Ultimately, the model facilitates cross-departmental decision-making, rendering it a valuable tool for coordinating efforts among supply chain managers, sustainability analysts, financial planners, and government representatives. It provides a standardized framework for assessing trade-offs and guiding corporate strategies toward global sustainability objectives and national industrial policies.

The findings of this study offer several important insights into the design and management of a sustainable EV battery closed-loop supply chain under uncertainty. The results show that incorporating neutrosophic information significantly improves system robustness by capturing the degrees of truth, indeterminacy, and falsity associated with uncertain parameters. Unlike deterministic models that assume fixed values, the NGP framework generates solutions that remain feasible and efficient even when demand, return rates, or recycling efficiencies fluctuate. This is particularly relevant for EV battery systems, where uncertainty is inherent due to the evolution of technologies, market variability, and inconsistent consumer return behavior. A key insight is the clear trade-off between cost minimization and environmental performance. While the NGP model reduces total cost, it also improves environmental outcomes such as lower carbon emissions and higher recycling rates. The sensitivity analysis further indicates that extreme uncertainty, exceptionally low return rates or reduced recycling efficiency can increase system costs and emissions while sharply decreasing material recovery. This highlights an operational trade-off: firms must invest in reliable collection networks and efficient recycling technologies to maintain system performance in the face of uncertainty.

From a managerial perspective, the results highlight the practical benefits of adopting neutrosophic-based decision-support tools. The model enables managers to evaluate the effects of policy changes, operational uncertainties, and technology investments before they are implemented, allowing for informed decision-making. For instance, the policy incentive scenario shows that a 15% recycling subsidy significantly enhances recycling performance while reducing both cost and emissions. Such insights can help policymakers design incentive programs that support circular economy goals in the EV battery sector. The expanded analysis reveals that the NGP framework is not merely a mathematical extension but a practical tool that enables decision-makers to handle uncertainty, identify risk-prone operational areas, and design balanced strategies. Its capacity to quantify trade-offs and assess policy impacts makes it valuable for both industry practitioners and policymakers seeking to develop efficient and sustainable EV battery supply chain systems.

Managerial and Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer several important managerial implications for firms involved in the manufacturing, collection, and recycling of EV batteries. The NGP model provides managers with a robust decision-support tool that explicitly accounts for uncertainty in demand, return rates, and recycling efficiency. By incorporating neutrosophic information, firms can design supply chain strategies that remain cost-effective and environmentally efficient even in highly variable operational conditions. Managers can utilize these insights to optimize transportation planning, allocate recycling capacities more efficiently, and prioritize investments in technologies that enhance recovery rates and reduce emissions.

From a practical standpoint, the results are directly relevant to current EV battery regulations and sustainability policies. The improved recycling rate achieved under the NGP framework supports compliance with Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) rules and emerging recycling mandates, which require manufacturers to meet minimum material recovery thresholds. The substantial reduction in emissions is also meaningful for firms operating under carbon taxation or emissions-trading schemes, as the NGP model enables more accurate estimation of emission outcomes and helps firms design strategies that minimize carbon-related financial penalties. Additionally, the sensitivity analysis reveals critical operational thresholds—such as the sharp performance drop when return rates fall below 40%—which can inform both managerial planning and government policies aimed at strengthening collection networks, buy-back incentives, or mandatory take-back programs for end-of-life batteries.

The observed benefits of a 15% recycling subsidy also highlight the value of policy support mechanisms in promoting circular practices. Governments seeking to enhance domestic recycling capacity can use such evidence to design targeted financial incentives that simultaneously reduce environmental impact and operational risk. The managerial and practical implications demonstrate that the NGP approach not only enhances supply chain performance but also facilitates firms’ alignment with evolving carbon policies, recycling regulations, and national EV sustainability goals.

7. Conclusions

This study presents an innovative and systematic methodology for designing and optimizing a CLSC for EV batteries under uncertainty. The proposed model is based on three conflicting objectives: minimizing the total cost, minimizing carbon emissions across the supply chain, and maximizing the battery recycling rate. To reasonably represent the uncertainties of EV SC parameters (demand, return rate, and emission fluctuation, etc.), the NGP method is employed. The objective of the framework is to consider the degrees of truth, indeterminacy, and falsity when deciding on goal-setting, as proposed in this paper. A numerical example based on the Indian situation was also created to show the feasibility of this model. It had two battery manufacturing facilities, P1 in Gujarat and P2 in Tamil Nadu. The distribution is carried out at several regional distribution centers, including D1 in Delhi, D2 in Mumbai, and D3 in Bengaluru. These DCs cater to retail demand regions denoted, which are the prominent EV marketplaces in Delhi (Re 1), Mumbai (Re 2) and Bengaluru (Re 3). C1, C2, and C3 are each linked to the respective retail zone for handling returned or used batteries, facilitating reverse logistics. Batteries collected from the collection centers are sent to recycling units, where R1 is located in Gujarat, and R2 is the recycling unit based in Tamil Nadu. The demand and battery return rate have been developed by utilizing neutrosophic numbers. The results indicated that the optimal cost using the NGP-based model was ₹18.75 crore; this includes the purchase price, transportation cost and recycling cost. Contrastingly, a deterministic linear programming model, i.e., one that disregards uncertainties, yielded a high cost of ₹21.3 crore, suggesting that the neutrosophic approach saved around 12%.

Regarding the environmental aspect, the total carbon emissions throughout the supply chain were minimized to 945 metric tons of CO2, which is much lower than the 1180 metric tons obtained under the conventional deterministic approach. With a 19.9% reduction in carbon emissions, the model helps India meet its current climate commitments under the FAME-II and SDG 13. Meanwhile, the developed model achieved a recycling and reuse rate of 82.6%, which is more than the base rate of 68% in the traditional method. The current finding supports India’s circular economy blueprint, reducing the need to acquire lithium, cobalt, and nickel, which are key components in the EV battery industry, from foreign suppliers. In terms of pure academic and industrial meaning, this research has a theoretical and industrial impact on sustainable supply chain management in the EV battery industry. First, the current study demonstrates that NGP can be considered a robust optimization method for addressing multi-criteria, fuzzy, and uncertain decision environments. Moreover, the research findings not only validate the feasibility but also provide a method for manufacturers, policymakers, and supply chain managers working in the EV battery segment in India and other emerging countries. It can be beneficial for claimants to adopt an efficient and adaptable supply chain strategy.

The sensitivity analysis further strengthens these findings by revealing how performance shifts under alternative uncertain scenarios. Conditions such as reduced recycling yield (−22.4% impact on recycling) and low return rates (−18.7% impact) significantly undermine system outcomes. In comparison, a critical threshold of return rate <40% leads to severe performance deterioration, with cost increasing by 15.2% and recycling dropping by 35.1%. Conversely, supportive policy measures, such as a 15% recycling subsidy, enhance system performance, improving recycling by 9.8% while reducing both costs (by 7.2%) and emissions (by 3.4%). These findings collectively demonstrate that the NGP model not only offers superior baseline performance but also serves as a powerful tool for identifying vulnerable operational areas, evaluating policy interventions, and ensuring supply chain resilience in the face of real-world uncertainty.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study makes an important contribution to modeling and optimizing a CLSC for EV batteries with NGP, several limitations exist. First, it is presumed that the New Caledonia nickel smelting cost, the environmental depreciation factor, and the effective recycling rate are the remaining three parameters; all these parameters are triangular neutrosophic numbers. While this reduces uncertainty and ambiguity, it remains based on expert estimates or historical data that may not necessarily align with real-world trends or rapid shifts (or shocks) in the market—particularly in a fast-changing area such as electric mobility. Secondly, the model considers three objective functions (cost, carbon emissions and battery recycling rate). Moreover, while these objectives are pivotal for the sustainability-related foundation, other important ones, such as energy consumption in production processes, social impacts (e.g., labor safety in recycling centers), and transportation delays, are currently not considered. For future research applications, the inclusion of such components could enhance the completeness or comprehensiveness of the decision framework, which is particularly useful when examining trade-offs among stakeholders in domains beyond economic and environmental considerations.

Another limitation of the article relates to the size and coarseness of the input data in the numerical example, which originates from an idealized scenario for a regional supply chain context in India. Although the model structure is illustrative, the scale of this representation cannot perfectly capture the operating complexity of a large-scale, national, or multinational EV battery supply chain. A possible extension of this study would be to validate the model using industry data from Indian EV manufacturers, logistics suppliers, and recycling companies. Additionally, the use of geographic information systems may enable the more accurate representation of transportation emissions and site locations. Furthermore, this model considers the centralization of decisions and static demand, or a return to the normal level, within the planning horizon. In practical contexts, particularly in decentralized and competitive market phases, members of a supply chain may have different objectives or operate under incomplete information. More advanced work may require game-theoretic or multi-agent approaches to account for decentralized decision-making, strategic behavior, and endogenous stakeholder dynamics.

A second enhancement could be to integrate renewable energy generation into the supply chain model. With the increasing trend among EV manufacturers of using solar- and wind-powered facilities, this paper aims to provide a more realistic picture of sustainability efforts by analyzing renewable energy optimization and its impact on overall emissions and operational costs. Hybrid optimization approaches (e.g., neutrosophic programming-based learning) could also be investigated to enable quick and adaptive supply chain decisions in real-time, leveraging predictive analytics and sensor data. Lastly, although this study is designed to be Indian-specific, further cross-country comparative work can provide insight into how the policy environment, infrastructure level, and consumers’ attitudes may influence the design of closed-loop EV battery supply chains, as well as their performance. Such cross-comparative work would support policymakers in designing region-specific incentives and regulations to facilitate a transition to a circular economy.