Abstract

The rise in energy demand has heightened concerns about the inefficient use of resources, escalating emissions, and unsustainable consumption trends in Bahrain. The use of conventional methods to manage such challenges has proved to be inadequate, demanding innovative approaches to balance environmental sustainability with economic growth. This study aims to investigate the impact of artificial intelligence on sustainable consumption, emission reduction, and resource optimisation in the energy sector in Bahrain. The study used a descriptive quantitative research design using a questionnaire distributed to 230 respondents from the energy sector in Bahrain using a stratified random sampling technique. According to the statistical findings, artificial intelligence has a significant positive effect on sustainable consumption (B = 0.634, t = 14.323, R2 = 0.474, p = 0.000), and reduction in emissions (B = 0.450, t = 9.950, R2 = 0.303, p = 0.000), as well as the optimisation of resources (B = 0.426, t = 10.316, R2 = 0.318, p = 0.000). These results confirm that there are strong positive correlations between AI and the three sustainability outcomes, and AI can account for between 30.3% and 47.4% of the variance of the dependent variables. This study presents new empirical insights regarding the role of artificial intelligence technologies in supporting national sustainability objectives as well as energy transition efforts.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, technological tools such as artificial intelligence (AI) are used in several sectors, including transportation, education, healthcare, and environmental sustainability and the green economy.

The serious problems caused by the global economy and population growth are environmental pollution and resource consumption [1]. These problems trigger the need to enhance sustainable development [2]. Sustainable consumption behaviour is important in the realisation of sustainable development goals. This process would enable significant reductions in the use of resources and gas emissions [3]. In protecting the environment, artificial intelligence can save energy, minimise emissions, and enhance sustainability [4].

Therefore, AI applications are of interest to this study on the green economy and environmental sustainability sector, in particular, in Bahrain. The study concentrates on AI’s contribution towards the attainment of sustainable consumption, a reduction in emissions, and resource optimisation. Before proceeding to examine the role of AI in this process, it is necessary to define AI. It is defined as a technological means that enables computers to perform several functions, such as the ability to translate, see, and understand written and spoken data, make recommendations and predictions, and analyse data [5].

In the industrial and energy sectors, AI is applied to the field of predictive maintenance, where faults in power plants and equipment are identified [6]. Consequently, it avoids wastage of energy and minimises downtime, which adds to emissions [7]. Emissions and control are monitored by utilising AI models [8]. Data that is collected by Internet of Things sensors at refineries and factories is processed by AI models to monitor the release of greenhouse gases, which allows taking immediate corrective measures [9]. AI optimises resources in heavy industries, such as oil and gas, steel, and cement, by managing the combustion of raw materials and processes used to decrease CO2 output [8].

In addition, AI supports sustainable consumption through the balancing of electricity demand and supply, integrating a more efficient and effective use of wind and solar, and reducing reliance on fossil fuels [10]. It also enhances energy operation efficiency [7]. AI-powered automation systems can optimise cooling, lighting, and heating systems in industries, reducing unnecessary energy use [3]. In addition, AI can be applied to a circular economy for the classification of waste and optimisation of recycling to bring industrial by-products to useful use [9].

The diffusion of artificial intelligence and the expansion of cloud infrastructure have increased the electricity demand worldwide exponentially, specifically for massive data centres. These facilities make up a portion of about 2% of total global electricity use, and this is estimated to rise until 2030 in the event that the present computational power remains the same [7,9]. The newer studies investigating renewable-powered and nuclear-assisted data centres are examples of the struggle to balance this rising energy footprint, which is of importance to the Bahraini digital and energy policy environment.

AI optimises resources by enhancing supply chain optimisation, material usage efficiency, and water and energy co-management [10]. To clarify, AI optimises the supply chain by reducing resource overuse by managing logistics and predicting demand for industrial raw materials and energy distribution [3]. AI enhances material usage efficiency; i.e., AI-powered simulations in manufacturing reduce scrap and enhance production design, which conserves raw materials [8]. AI is effective for water and energy co-management. AI enhances water usage in chemical processes and cooling systems, which lowers both operational costs and resource waste [7].

In Bahrain, the industrial sector is a significant issue in economic development; therefore, it is quite essential to ensure that sustainability is integrated in industrial development to prevent any degeneration of society and the environment and to sustain the economy [11]. Nevertheless, the application of AI within the energy sector in Bahrain has not been maximised due to technology, legal, and regulatory frameworks obstructing its use within industry, which limits public confidence in it and successful adoption [12].

Thus, this study examines the influence of AI in the sectors of industry and energy in Bahrain to point out how it could contribute to improvement in sustainable consumption, reducing emissions, and the optimisation of resources.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Energy Sector in Bahrain

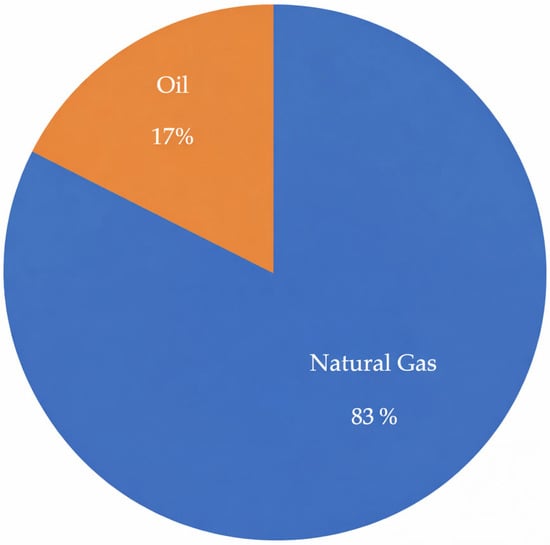

In Bahrain, the energy sector relies on indigenous hydrocarbon resources [13]. The main sources of energy in Bahrain are oil and natural gas [14]. Natural gas amounted to (83%) of total energy consumption, whereas oil accounted for (17%) [15]. In 1932, Bahrain was the first country in the Gulf region to discover oil reserves [13]. Crude oil production reached its peak in 1970 [14]. In the following years, the energy sector in Bahrain has significantly declined [16]. The expected lifetime of the oil reserves is around 11 years, whereas the natural gas reserves are projected to last approximately 15 years [15].

Natural gas is crucial for water and power generation, enhanced oil recovery, and manufacturing [14]. Nevertheless, Bahrain is projected to depend on imported gas as early as 2018 because of diminishing reserves [15]. In addition, the energy sector constitutes the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Bahrain, amounting to 77% of total emissions [13]. The energy intensity in Bahrain is higher than the world average and that of the Gulf countries, implying considerable potential for efficiency improvements [14]. In Bahrain, power encompasses a combination of captive power plants owned by industries, the Electricity and Water Authority (EWA), and independent power and water producers (IWPPs) [13]. The hydrocarbons formed the major source of energy in Bahrain in 2024, with natural gas contributing around 83 percent and oil 17 percent of total primary energy consumption, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Composition of Bahrain’s energy sector (2024).

Hydrocarbons continue to make up the majority of Bahrain’s energy, with natural gas contributing around 83 per cent and oil accounting for 17 per cent of the total primary energy usage. Although still not as large, renewable energy is a strategic priority of national transition policies, including the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NREAP) and the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan NEEAP [17].

Residential and commercial components are the largest consumers of grid electricity in Bahrain, whose on-peak demand during the summer season increases due to air conditioning requirements [14]. Fossil fuel reliance has been reduced, and energy efficiency maximisation has been exercised, and this has been achieved by efforts such as the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) and the use of renewable energy technologies [13].

Bahrain has sustainability issues that can be traced to its extremely high reliance on dwindling hydrocarbon reserves, energy intensity, and significant emissions of greenhouse gases [16]. To elaborate, the natural gas and oil reserves in Bahrain are expected to last only 11 and 15 years [18]. This led to an increasing shift to alternative energy sources and a decrease in reliance on imports [19]. Bahrain’s energy intensity is 54% higher than the world average and that of the Gulf, which implies inefficient energy use across sectors [20]. The energy sector in Bahrain contributes to 77% of Bahrain’s total emissions, with per capita carbon dioxide CO2 emissions among the highest worldwide [16].

The problem is worsened by the fact that Bahrain depends on air conditioning and desalination plants, which are very energy-consuming, owing to the poor climate [19]. Bahrain is faced with seasonal electricity demand due to the summer seasons, primarily attributable to the air conditioning, which constitutes 60–65% of the electricity consumption in buildings [16]. In order to satisfy peak demand, this problem requires expensive additional generation [19]. Some of the other issues that are challenges to environmental sustainability and economic competitiveness are dependence on fossil fuels, attempts to lower the cost of energy, and high emissions [18].

In addressing Bahrain’s sustainability challenges, AI plays a considerable role by improving resource management, reducing emissions, and optimising energy use [21]. AI has significant advantages in terms of improving sustainability by optimising energy resources [22]. In an attempt to explain, AI may be used to examine energy consumption patterns in industries, transportation, and buildings to suggest how they can be improved and what inefficiencies can be detected [23]. Moreover, AI-powered smart grids could be more efficient in distributing electricity, controlling peak loads, and minimising the transmission losses [24]. Moreover, AI is able to forecast the production of renewable energy sources (e.g., wind and solar) based on the weather, which can be integrated into the energy grid in a more effective way [23].

AI could streamline the performance of renewable energy systems by ensuring the highest level of reliability and efficiency [21]. In addition, AI has predictive maintenance; i.e., AI could monitor equipment in industries and power plants to predict failures, schedule maintenance, improve efficiency, and decrease downtime [23]. AI could support demand response programs and dynamic pricing, which encourages consumers to change their energy consumption to off-peak periods to reduce the pressure on the grid [24]. In addition, AI can also streamline transport schedules and routes, encouraging more people to use more eco-friendly forms of transport [25].

AI can be used to facilitate the fuelling of electric vehicles by optimising vehicle routes and charging systems [23]. It further supports the implementation of electric cars through improved vehicle movements and charging systems [24]. Moreover, AI could facilitate the effectiveness of the desalination plants because it can minimise the waste and maximise the consumption of energy [20]. It also has the ability to track water piping systems to ensure that they are used effectively, as well as to detect leaks [21]. AI is capable of analysing large datasets to present insights for policymakers by assisting them in designing effective sustainability programs and energy efficiency [20]. In addition, the artificial intelligence-based applications can inform consumers about energy-saving measures and offer them customised advice to reduce their use [23]. The use of AI in these fields will also give Bahrain the possibility of changing to a more sustainable and energy-efficient future sooner, overcoming its energy peculiarities. The oil and gas sector in Bahrain has the largest application of AI, with predictive maintenance, drilling optimisation, and asset monitoring becoming part of operational efficiency. Electricity generation and desalination are also being adopted, which demonstrates slow digital diversification in the energy industry.

2.2. Sustainability in Bahrain

As the sustainability report of the Government of Bahrain defines, sustainability is deemed one of the fundamental principles on which the Bahrain Economic Vision 2030 is based [26]. This vision is aimed at changing the perspective of the economy, government, and society concerning competitiveness, fairness, and sustainability [27].

The scope of key issues in sustainability in Bahrain focuses on sustainable environmental and resource management, biodiversity, marine conservation, waste management, urban growth, transport, energy, water, and urban development [28]. To attain sustainability in its diverse dimensions, numerous governmental institutions and committees have been set up in Bahrain [29].

According to the Economic Vision 2030, sustainability is the key to the long-term development of Bahrain [30]. It aims at balancing environmental preservation with economic growth [31]. Sustainability guarantees the resilience of Bahrain by diversifying away from hydrocarbons and consolidating sustainable urban development, water conservation, and renewable energy [32]. In addition, the concept of sustainability contributes to the international image of Bahrain, focusing on the development of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) systems and adhering to international treaties [27].

Bahrain will be carbon neutral by 2060 with the help of the National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP), Blueprint Bahrain, and the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) [33]. The major landmarks incorporate carbon emission decreases of 6%, developing renewable energy projects such as wind and solar farms, and incentivising sustainable production by implementing the Green Factory Label programme [34]. Moreover, the establishment of the Supreme Council for the Environment and the Ministry of Sustainable Development demonstrates a strong institutional commitment to attain the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [35].

Nevertheless, Bahrain faces various problems in achieving sustainability: first, an environmental–economic challenge with regard to achieving high economic growth along with maintaining price stability [36]—this includes, moreover, the entire utilisation of production despite the shortage of natural resources [37]; second, climate change, i.e., its negative effects on health, infrastructure, coastal installations, biodiversity, agricultural resources, and water [28].

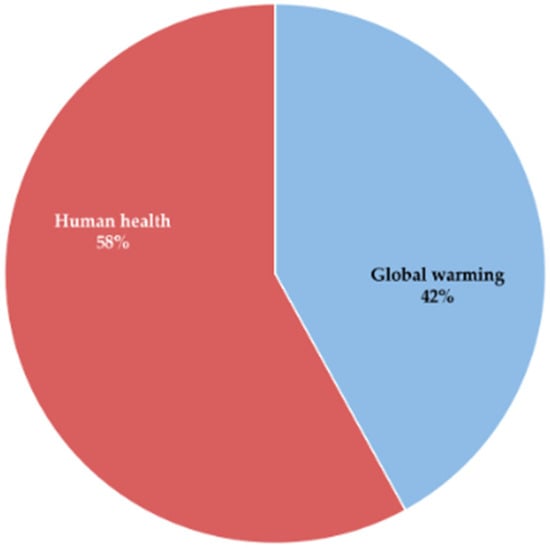

This requires immediate intervention in the form of the transfer of green technologies, capacity building, financing, and the popularisation of community consciousness on consumption patterns and sustainable production [36]. The third challenge is global partnership, which means enhancing global partnerships to fund development initiatives to make partners sustainable [38]. In spite of these challenges, Bahrain is committed to the well-being of its citizens and the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by means of resource conservation as a legacy to the future generation [28]. Figure 2 below demonstrates the correspondence between national policy on energy-related areas and the SDGs.

Figure 2.

Bahrain’s energy policy alignment with SDGs.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are consistent with the policy direction in Bahrain, especially SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), and SDG 13 (Climate Action). NREAP and NEEAP operationalize these objectives by setting specific targets on renewable integration, efficiency improvement, and by 2060, carbon neutrality.

2.3. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainability

Artificial intelligence, as well as smart applications, is employed to attain sustainability goals [39]. Nowadays, addressing environmental challenges demands combining sustainable consumption with artificial intelligence [40]. AI-powered smart apps, such as AI, transform several aspects of our lives, like resource use [41]. Smart apps, AI, and sustainable consumption promote positive environmental effects as well as a more sustainable future [42].

This is due to the fact that such technologies consume resources because they have the capability of identifying patterns, making well-informed decisions, and analysing large amounts of data [39]. AI-driven smart applications and artificial intelligence accelerate a considerable shift towards sustainability in various industries, from empowering consumers and streamlining supply chains to transforming transportation networks and energy efficiency [40].

Therefore, it is critical to address environmental issues by integrating AI as well as sustainable consumption practices to reduce emissions and optimise resources. In this respect, [42] asserts that AI promotes energy consumption, optimises resources, and minimises waste. Moreover, AI helps to reduce emissions and increase the overall resource efficiency [41]. In the context of the Economic Vision 2030 of Bahrain, AI plays a central role in enhancing the sustainability agenda in the kingdom, through enhancing resilience in business and governance, efficiency, and accountability [43].

2.4. Sustainable Consumption

Sustainable consumption is the consumption of natural resources in a conscious manner by taking into account future generations [39]. Sustainable consumption behaviour means an ecological, green, and moderate consumption method, which focuses on decreasing the influence on the environment without influencing the individual’s quality of life [44]. Such a consumption pattern is anchored on the notions of low-carbon environmental protection and the circular economy [45]. It prompts individuals to opt for renewable resources and reusable products, and to adopt environmentally friendly and sustainable lifestyles [46]. Such patterns decrease resource consumption and energy, mitigate climate change, improve the living conditions of humans and animals on Earth, and protect the environment [44].

Despite the importance of sustainable consumption behaviour, the literature indicates that this behaviour is not sustainable [45]. To encourage sustainable consumption, it is necessary to identify the factors influencing sustainability [44]. The literature on sustainable consumption behaviour has relied on internal factors that are both personal and psychological factors, such as beliefs, attitudes, emotions, and behaviour patterns [47]. Nevertheless, the influence of external factors such as those provided by information technology has been overlooked in the literature [46]. An example of this information technology is AI, which has inundated every aspect of people’s lives [47]. In addition, AI has several advantages in various sectors, including the industrial sector, due to its ability to achieve tasks in a timely and efficient manner [46].

2.5. Emission Reduction

The accumulation of heat-retaining greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide (CO2), contributes to global warming and poses a severe risk to the planet [48]. The main driver of global warming is CO2 emissions [49]. The main contributor to CO2 emissions is the energy sector [50]. According to Lamb et al. [51], the energy sector is responsible for roughly 34% of global CO2 emissions, which considerably heightens this problem. As such, there is a need to minimise such emissions in order to reduce the drastic effects of climate change [52]. One of these solutions is AI tools, which can be applied to solve various problems in many sectors where they have wide applications.

In addition to environmental degradation, there are quantifiable public health costs from emissions. The World Health Organization (WHO) (2023) [53] states that energy production causes air pollution that increases respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity in the Gulf. Furthermore, global warming increases these risks through increasing heat exposure and reducing the quality of the air. Therefore, AI-enhanced emission optimisation within the Bahraini energy industry has environmental and human health implications.

AI can be used to optimise these processes [54]. There are promising possibilities of AI in increasing the efficiency of renewable energy sources, managing energy requirements, and optimising energy use [55]. Modern AI technologies may offer optimisation measures to reduce emissions in other industries, especially in the energy industry [40]. AI helps in controlling quality in industrial sectors [56]. AI tools can be used to support decisions [54]. They may be used to combat CO2 emissions in the energy sector, as it relies on efficiency [55]. Hence, the need to harness the potential of AI for the reduction in emissions arises because of its influence on informational policy and investment choice, facilitating further innovation, and environmental benefits [57]. The role of artificial intelligence in achieving greenhouse gas reduction is also prominent due to the efficiency of energy use and optimisation of processes [58]. AI enhances the precision of forecasting renewable energy, aids predictive maintenance, and optimises the parameters of energy generation, which all decrease unnecessary fuel emissions and CO2 emissions [58]. Nonetheless, AI-driven systems demand significant computational resources and power to process the data, and the model training is a source of indirect emissions when facilities are powered by fossil-dependent grids [59]. Such environmental implications raise the question of energy-efficient AI models and low-carbon infrastructure so that the positive environmental effects can exceed the computational costs [60]. Recent research also indicates that major AI training may lead to substantial emissions when not justified by sustainable computing strategies, unless they are adopted, which supports the relevance of integrating AI implementation with national decarbonisation plans [61].

2.6. Resource Optimisation

Resource optimisation refers to the strategic utilisation and administration of resources or personnel, material, money, and time in order to reduce waste and maximise efficiency [62]. The importance of resource optimisation, especially in organisational and industrial settings, is associated with the growing stress on efficiency demands, economic pressures, and environmental issues [63]. Resource optimisation emerges as one of the main concerns for all firms, regardless of the sector, in the 21st century [64]. The need for advanced optimisation becomes of the utmost importance for organisations due to the increased pressures of global competition, along with the increasing importance of environmental sustainability [65]. Resource optimisation approaches, as well as real-world allocation to resource allocation, are uncertain and complicated because the traditional approaches used for allocating resources take into consideration mathematical optimisation [63].

AI plays a critical role in the optimisation of resources due to its importance for using, scheduling, and revolutionising resource allocation [65]. AI-based applications can be used to overcome the limitations of traditional approaches used for resource optimisation and allocation [63]. This occurs by incorporating the best practices of machine learning techniques and algorithms like evolutionary computation and neural networks [62]. AI alters how organisations attempt to solve complicated, multi-subject optimisation problems and permits complicated solutions that have not been computationally feasible [63]. AI-based applications can adjust real-time conditions and dynamically optimise [66]. AI-based applications, in optimising resources, tend to combine control theory, machine learning, and operations research [64].

AI can be used in various disciplines, spanning environmental resource utilisation, cloud computing, supply chain activities, energy management, and manufacturing [65]. In resource optimisation, AI-based applications outperform traditional optimisation methods in sustainability metrics, cost savings, and efficiency [62]. In optimising resources, metaheuristic algorithms, such as simulated annealing, particle swarm optimisation, and genetic algorithms, have been augmented with machine learning processes to optimise their parameters [63]. Such hybrid approaches demonstrate an enhanced ability for solving problems with NP-hard optimisation, typical of resource allocation problems [64].

However, applying AI-based applications for resource optimisation has some challenges that have resulted in new developments in explainable AI, quantum-enhanced optimisation, federated learning, interpretability, scaling, and data quality [66].

These results are consistent with the previous research, which has continued to emphasise the potential of artificial intelligence for transforming the nature of consumer behaviour, improving energy consumption, and offering new optimisation solutions in various environments [39,48,67,68]. Like these investigations, the current research has affirmed the potential of artificial intelligence to shape the nature of consumer behaviour, enhance energy consumption, and offer advanced optimisation strategies in various settings, including China, Turkey, and other energy industries across the globe. Nevertheless, those studies are different since, in contrast to the previous ones, this study focuses on the particular region of Bahrain, where the increasing energy consumption, poor resource use, and high emissions are the most pressing issues at present [11,16].

Although past works focused on general technological, behavioural, or global implications [69,70], they have not focused on the specific situation of Bahrain, which is heavily dependent on hydrocarbons, and the acute necessity to find new instruments that would allow for a balance between economic growth and sustainability. This study, therefore, bridges a significant gap by becoming the first empirical study that offers the existing understanding of AI in facilitating sustainable consumption, reduction in emissions, and optimisation of resources in the energy sector in Bahrain, and contextualises all the international findings for a national context where AI adoption is underexplored [12].

In this study, the researcher examines the impact of artificial intelligence on achieving sustainable consumption, emission reduction, and resource optimisation. The literature focused on the individual impact of artificial intelligence on each of these variables. None of the previous studies tackled all these variables collectively, particularly in the energy sector in Bahrain. Therefore, this study was conducted to fill this gap in the literature by investigating this issue from the perspectives of the employees in the energy sector in Bahrain. In spite of the significant sustainability advantages of AI, it comes with environmental costs associated with the energy-intensive nature of data processing, and ethical issues of data governance and transparency. These effects require strict regulatory control and energy-saving infrastructure for AI to balance in such a way that the value of sustainability surpasses the expense of resources.

2.7. Hypothesis Development

2.7.1. Artificial Intelligence Improves Sustainable Consumption

Several studies were conducted to investigate the impact of AI in achieving sustainable consumption. Cao and Liu [67] examined the role of AI in promoting sustainable consumption behaviour in Ant Forest users in China. The study further examined the mediating impact of customer stickiness and customer-perceived value. The study adopted the theory of planned behaviour and stimulus–organism–response theory. To this end, a questionnaire was distributed to 280 Ant Forest users. The data were analysed using regression analysis. The findings showed that AI can promote sustainable consumption by influencing consumer behaviour with gamified and entertaining experiences to make consumers become sticky, strive to enhance the emotional value, and produce consistent, environmentally friendly behaviour online and offline.

Artificial intelligence’s effectiveness in facilitating sustainable consumption in Turkey was studied [39]. The study found that AI applications enhanced informed decision-making, delivered positive environmental impact, and maximised resource management. However, they argue that some natural challenges should be taken into account, including data privacy issues, the digital divide, and algorithmic biases. AI facilitates sustainable consumption by encouraging supply chains to minimise waste [71] and promoting smarter resource management [72], energy efficiency [20], and information and personalised decision-making by consumers, resulting in greener decisions [73]. The first hypothesis is based on the above and is as follows:

H1.

AI improves sustainable consumption.

2.7.2. Artificial Intelligence Reduces Emissions

The use of AI in changing traditional consumption behaviour into more sustainable patterns is essential because it can be used to extract insights and analyse large amounts of data [56]. AI technologies are also used to optimise resources, reduce waste, integrate renewable energy sources, and consume less energy, increasing sustainable practices [49]. AI resulted in increased energy efficiency, mitigating the key obstacles in industries such as marketing, transport, and energy, and carbon footprints were abated [50]. Alatalo et al. [48] reviewed the literature on the advantages of AI in reducing CO2 emissions in the energy sector, reviewing 16 papers related to the topic under investigation. The study found that AI reduces CO2 emissions.

The study further found that AI models can optimise energy generation processes in terms of modelling such processes and identifying their optimal parameters. Moreover, [48] states that AI technologies can be employed in predicting, which helps to plan production, transmit energy, and optimise decision-making. In addition, [48] reports that AI is used to enhance energy efficiency, particularly through building performance optimisation. Therefore, it can be concluded that AI applications can potentially decrease emissions. According to the latter, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

AI tools contribute significantly to emission reduction.

2.7.3. Artificial Intelligence Leads to Resource Optimisation

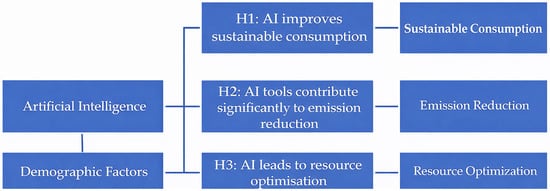

Multiple studies [69,70,74] assert the implementation of AI in energy industries, electrical engineering, and smart buildings to enhance sustainability, operational efficiency, and energy optimisation. Jatoth [68] reviewed the literature on the use of AI for optimising resources. He found that AI optimises efficiency, sustainability, and cost savings by scheduling and enabling advanced allocation. Furthermore, AI leverages real-time optimisation, deep learning, and algorithms that are better than traditional approaches in terms of processing multi-objective, dynamic, and difficult problems [70]. According to his research, [75] suggests that AI has the ability to optimise resources, decision-making, and minimise risks. With respect to resource optimisation, [75] explains that AI guarantees the completion of projects in a cost-effective and timely manner. In addition, AI is effective at analysing real-time inputs and historical project data to predict future resource needs and identify patterns with greater precision compared to traditional methods [66]. Figure 3, presented in the conceptual framework summarizes hypothesised relationships investigated in the present study.

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework of the study.

Based on the above, the third hypothesis is postulated:

H3.

AI leads to resource optimisation.

The conceptual framework illustrates the hypothesised connections between artificial intelligence (independent variable) and three aspects of sustainability, namely sustainable consumption, emission reduction, and resource optimisation (dependent variables), within the Bahraini energy sector. The demographic variables, including age, education level, and years of experience, were incorporated to examine the possible moderating effects that can influence the strength or direction of these relationships.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

With a descriptive quantitative research design, this cross-sectional study sought to explore the effectiveness of AI in improving sustainable consumption, emission reduction, and resource optimisation in Bahrain. This method gathers quantified data, undertakes re-relationship, and delineates patterns among variables through statistical techniques.

The design is cross-sectional, which facilitates the establishment of statistical relationships as opposed to causal processes. In turn, the relationships between AI use and the sustainability outcomes reported should be viewed as correlation patterns rather than as evidence of causation.

3.2. Sample of the Study

The study sample included all employees who interact with AI-based applications in their work or everyday experience, especially those who work in the energy industry. The research sample was 230 respondents in the energy industry in Bahrain. To make sure that the sample was equally representative of the different groups in terms of demographic factors such as age, gender, and occupation, a stratified random sampling method was used.

3.3. Data Collection

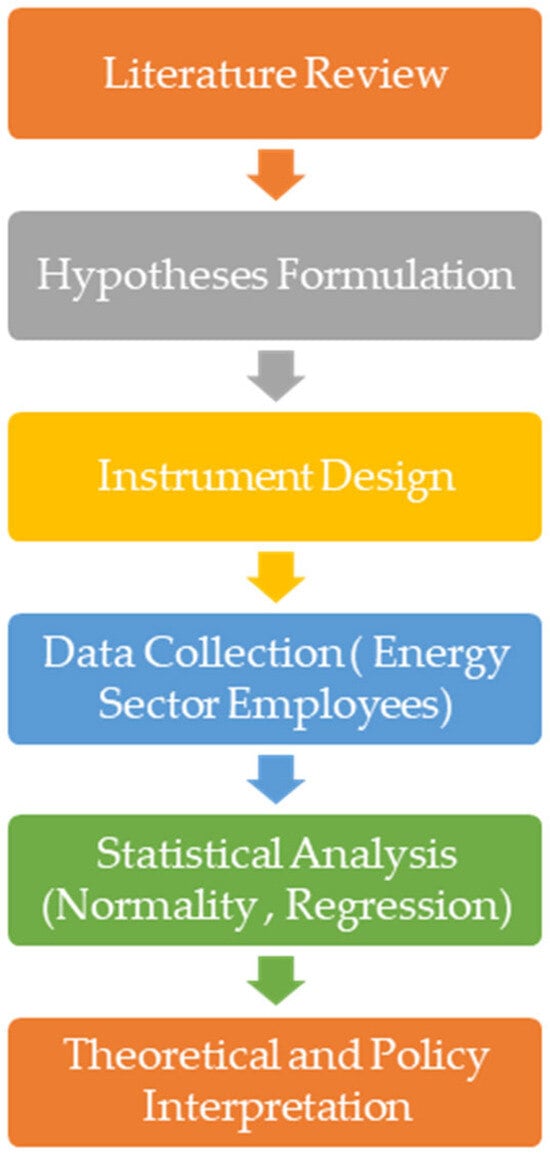

The researcher used a questionnaire to gather data in this research study, but distributed it to the employees in the energy industry in Bahrain through Google Forms (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA). The survey was a questionnaire that was divided into demographic questions such as age, gender, education level, occupation, and years of experience with technology. The second section consists of 5 items for the independent variable ‘artificial intelligence’. The third section contains 5 items for the dependent variable ‘sustainable consumption’. The fourth section includes 5 items for the dependent variable ‘emission reduction’. The fifth section includes 5 items for the dependent variable ‘resource optimisation’. The study measured the items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). The questionnaire employed in the study was derived from the literature, but it was reformulated to suit the objectives of the study. The overall research process and variable flow are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Research design flow.

The operationalisation of AI usage in this study took the form of the frequency and extent of interaction with the artificial intelligence system regarding both operational and sustainability-related activities. This consisted of (a) general workplace applications of AI, e.g., automation tools and predictive analytics, and (b) sustainability-related applications, e.g., energy monitoring, optimisation, and emission control systems. The fact that both types are included also indicates the integrated character of digital transformation in the energy sector in Bahrain, where the role of AI functions can be used in a variety of overlapping ways.

To check the validity of the questionnaire, the instrument was presented to a group of academic researchers (with sustainability and AI experience) to verify its relevance and appropriateness, and the intelligibility of the questions. To determine reliability, Cronbach’s Alpha was used to evaluate internal consistency. When the values are more than 0.70, the instrument is regarded as a reliable instrument. The scholar adhered closely to ethical considerations, i.e., the confidentiality of the respondents and their anonymity. The researcher has received informed consent from the respondents by advising them that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any stage in the study.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data were coded and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (SPSS, version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Both descriptive statistics and inferential statistics were used. The former extracted means, standard deviations, and frequencies to summarise responses for each variable and demographic information. The latter executed correlation and multiple regression analysis to test the relationship between variables.

Although in this research, reliability was mainly measured by the use of internal consistency measures (Cronbach’s alpha), the constructs were theoretically based on previously validated tools in the literature, and they were content- and face-validated by subject matter experts. This ensured that the measured items had conceptually coherent elements of AI utilisation, sustainable consumption, emission cut-down, and resource optimisation. Nevertheless, since the convergent and discriminant validations were not conducted in an explicit manner, using exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis, future research should include those analyses to confirm the dimensional choice and reduce the possibility of construct overlap or multicollinearity between different variables.

4. Results

This section presents the demographic results regarding the demographic distribution of the energy sector among employees using AI applications, the normality test, and the hypothesis testing, as illustrated below:

4.1. Demographic Distribution of Energy Sector Employees Using AI Applications

The demographic data of the study sample in terms of age, gender, education, occupation, and technology experience of the employees in the energy industry are presented in Table 1, shown below, which includes frequencies and percentages. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of energy sector employees using AI applications.

The sample data indicates that the 55 years and above category forms the majority of the workforce (32.2%), then the 25–34 age group (23.5%), and then the 35–44 age group (18.3%). The male proportion of the participants is 59.1%, and the female proportion of the participants is 40.9%. The majority of the workforce has bachelor’s degrees (23.5%), followed by master’s degree holders (18.3%). The sample contains a team of engineers and tech geniuses in the field of IT and artificial intelligence, demonstrating the level of development of this field. In terms of years of experience in the area of technology, the findings indicated that the largest proportion of the participants had over 10 years of experience (32.3%). It is also clear that there is a variation in the years of experience of the participants, which reflects the diversity of the level of experience and skill in this field.

4.2. Descriptive Analysis of Study Variables

To identify the current state of artificial intelligence, its use in Bahrain’s energy sector, the level of sustainable consumption, and the practice of activities for emission reduction and resource optimisation, the means and standard deviations were calculated. The following table presents these values.

The results of Table 2 showed a tendency to employ artificial intelligence and its technologies, as the mean score reached 3.73, which reflects employees’ reliance on AI technologies. Employees frequently use AI-based applications in daily life (mean = 3.81, SD = 0.81), while the item “I use AI applications to manage resources more efficiently” obtained the lowest mean score (mean = 3.67, SD = 0.73). These results indicate that the use of AI in daily and practical activities is greater than its use in sustainability issues.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables.

Moreover, the findings also revealed that employees in the energy industry were conscious of the significance of sustainable consumption and taking up measures to enhance the practice, as the mean score was (4.04). The highest rating (mean = 4.14, SD = 0.72) was received by the item “I actively try to reduce unnecessary consumption in my everyday life” and the lowest rating (mean = 3.88, SD = 0.86) by the item “I use AI or other tools to enable more sustainable consumption choices”. These findings indicate that sustainable consumption is a by-product of personal conduct, personal beliefs and the recognition of its role in attaining sustainability.

The results also revealed the employees’ commitment to reducing emissions by adopting effective behaviours to limit environmental pollution and reduce energy consumption, as the overall mean score reached (mean = 3.93, SD = 0.40). The item “I actively try to reduce my personal or workplace carbon emissions” ranked first (mean = 4.02, SD = 0.80), while the item “I make consistent efforts to decrease my overall environmental emissions” ranked last (mean = 3.83, SD = 0.77). This result confirms the tendency of organisations and employees in the energy sector to implement comprehensive practices and strategies to reduce harmful emissions.

With regard to resource utilisation, the results showed that the energy sector is keen on making use of available resources efficiently and effectively, as this variable achieved a high mean score (mean = 4.00, SD = 0.37). These findings showed that employees are seeking to remain productive by consuming fewer resources (mean = 4.16, SD = 0.53), and they are also aiming to be continuous to reduce resource waste in their activities, but with less efficiency (mean = 3.88, SD = 0.69). These findings represent the existence of some areas that can be invested in to maximise optimal resource utilisation.

4.3. Normality Test

To verify that the data used for statistical analysis and hypothesis testing follow a normal distribution, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was conducted. According to Sager (2025) [61], data are considered to follow a normal distribution if the significance level is greater than 0.05. The following table presents these results.

As shown in Table 3, the values of all the statistical tests of the study variables are at p-values greater than 0.05, which is an indication that the data of the study are normally distributed.

Table 3.

Normality test.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

To test the three hypotheses of the study, simple regression analysis was used; the following tables present these results. The coefficient of determination (R2) was derived as

where denotes observed values, predicted values, and the sample mean. R2 thus quantifies the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variable.

4.4.1. Results of Testing the First Hypothesis

H1.

AI improves sustainable consumption.

Table 4 indicates that AI improves sustainable consumption, as evidenced by the t-value of (14.323) at p-value (0.000), which is statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.05). Referring to the R value of (0.688), this indicates a positive relationship between artificial intelligence and sustainable consumption.

Table 4.

Regression results: AI and sustainable consumption.

In addition, the R2 value reached (0.474), meaning that artificial intelligence explains (47.4%) of the variance in sustainable consumption. Furthermore, the B value was (0.634), which means that a one-unit change in artificial intelligence corresponds to an increase of (0.634) in sustainable consumption. Therefore, the null hypothesis stating that AI improves sustainable consumption is supported.

4.4.2. Results of Testing the Second Hypothesis

H2.

AI tools contribute significantly to emission reduction.

Table 5 indicates that AI tools contribute significantly to emission reduction, as evidenced by the t-value of 9.950 at p-value (0.000), which is statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.05). Referring to the R value of 0.550, this indicates a positive relationship between artificial intelligence and emission reduction. Moreover, the value of R2 was (0.303), which implies that artificial intelligence explains (30.3%) of the reduction in emissions. Also, the B value was (0.450), implying that a unit shift in artificial intelligence correlates with a rise of (0.450) in emission reduction. Therefore, the null hypothesis stating that AI tools contribute significantly to emission reduction is supported.

Table 5.

Regression results: AI and emission reduction.

4.4.3. Results of Testing the Third Hypothesis

H3.

AI leads to resource optimisation.

Table 6 indicates that AI leads to resource optimisation, as evidenced by the t-value of (10.316) at p-value (0.000), which is statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.05). Referring to the R value of (0.564), this indicates a positive relationship between artificial intelligence and resource optimisation. Moreover, the value of R2 obtained (0.318) indicates that artificial intelligence accounts for (31.8%) of the variance in resource optimisation. Furthermore, its B value was (0.426), implying that an increase in resource optimisation by one unit is associated with a corresponding increase of (0.426) in artificial intelligence. Therefore, the null hypothesis stating that AI leads to resource optimisation is supported.

Table 6.

Regression results: AI and resource optimisation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Demographic Findings

The demographic characteristics of the employees in the energy industry of Bahrain show significant patterns concerning the use of AI. The highest percentage of the respondents was in the 55 years and above category (32.2%), then 25–34 years (23.5%), and then 35–44 years (18.3%). This implies that although younger workers comprise a significant portion of the workforce, the older professionals make up the majority. This variety indicates that the implementation of AI cuts across generations, including traditional expertise and current technological flexibility.

Regarding gender, males composed 59.1% and females 40.9%, with a large percentage of females in what has always been a male-dominated industry. Such a balance implies that the use of AI can be facilitated by a more diverse workforce.

In terms of education, the highest percentage of the participants had bachelor’s degrees (23.5%), followed by master’s degrees (18.3%), and a significant amount of the respondents were under “Other” (32.2%), which could include specialised certification or a professional diploma. This is a sign of a highly educated workforce capable of working in technical and managerial roles integrating AI.

Engineers (19.1%), IT/AI specialists (17.4%), and energy analysts/researchers (17.0%) were a substantial proportion occupationally, which verifies that the industry is dependent on technical skills and digital innovation. Lastly, 32.2% had over 10 years of technological experience and demonstrated the maturity of the technical capabilities of the industry, and the other groups of experience were relatively equal, which demonstrates a balanced composition of experienced professionals and young talent.

5.2. Discussion of Hypothesis One: AI Improves Sustainable Consumption

The outcome of the regression (Table 4) proved that AI has a great contribution to sustainable consumption (B = 0.634, t = 14.323, R = 0.688, R2 = 0.474, p = 0.000). This implies that AI describes a sustainable level of consumption among the employees by 47.4%, which is a significant percentage. The employees are actively using AI in their everyday life (mean = 3.81), although it played a less significant role in influencing the sustainability of consumption (mean = 3.88).

Although AI accounts for almost half of the variance in sustainable consumption, the remaining part reflects behavioural, institutional, and cultural influences that are not reflected by technological use alone. This suggests that although AI can be used to guide sustainable behaviour, AI is part of a wider socio-technical system, in which values around the environment, policy incentives, and organisational culture will have the ultimate impact. A notable result is the translation gap between the adoption of general AI tools and their application to sustainability. Employees regularly use AI tools (M = 3.81), but their use for making sustainability-related decisions is lower (M = 3.88). This means that the adoption of technology is not a direct and automatic driver of environmental intent, which resonates with recent debates about digital sustainability alignment [76].

These results are consistent with [67], who demonstrated that AI promotes sustainable behaviour by gamifying and improving decision-making. Likewise, [39] concluded that AI applications aid informed decision-making and have a positive environmental effect. The consistency of these studies adds to the fact that AI is an enforcer of behavioural change, particularly affecting individual decision-making and awareness.

The implication is that AI tools in Bahrain’s energy sector can effectively steer employees toward more environmentally responsible consumption patterns. However, the difference in the score of AI-driven sustainable decisions is slightly lower, which indicates that there is not yet a tendency of alignment between technological potential and day-to-day sustainability practices. This demonstrates that there is a need to integrate AI applications more closely with sustainability endeavours by means of particular policy and training programmes.

5.3. Discussion of Hypothesis Two: AI Tools Contribute Significantly to Emission Reduction

The second hypothesis was analysed (Table 5), and it was revealed that AI tools play a significant role in the reduction in emissions (B = 0.450, t = 9.950, R = 0.550, R2 = 0.303, p = 0.000).

This comparatively low explanatory power suggests that emission reduction does not depend solely on the predictive or optimisation capacities provided by AI, but is also dependent on structural and regulatory conditions. In the context of Bahrain, energy infrastructure and policy frameworks play a critical role as mediators in AI’s environmental performance. Recent literature (Jebbor, Benmamoun, & Hachimi, 2025) [77] emphasises this interplay between digital intelligence and systemic governance in achieving carbon-efficient operations. The contribution of AI to the reduction in emissions was 30.3%, and it indicates a strong yet less prominent effect than sustainable consumption. The employees are proactive in trying to minimise carbon emissions (mean = 4.02), which reflects the commitment of the individual employees, with a facilitative role of AI.

This finding is aligned with [48], who had determined that AI decreases CO2 emissions through energy process optimisation and building efficiency. In the same way, [8,50] highlighted the vital role of the energy sector in CO2 emissions and the relevance of technological remedies to overcome this challenge.

This means that AI can be very instrumental in the Bahraini energy industry since it can be applied to monitor, predict, and optimise the emissions. However, since the share of AI contributes only one-third, there are other factors, including the regulatory frameworks, company policies, and the readiness of infrastructure, that have a decisive impact on the results of emission reduction. Therefore, national energy and emission policy should also include the application of AI programs to ensure their maximum efficiency.

5.4. Discussion of Hypothesis Three: AI Tools Led to Resource Optimisation

The findings of the third hypothesis (Table 6) showed that AI causes resource optimisation (B = 0.426, t = 10.316, R = 0.564, R2 = 0.318, p = 0.000). This value validates the positive but partial role of AI: technological systems improve the efficiency of operations, but optimisation results are still subject to managerial decision-making and data reliability. Similar observations were made by Jebbor, Hachimi, & Benmamoun (2025) [78], who found that AI-driven resource scheduling attains its fullest potential only in digitally mature industrial environments. The results imply that AI predicts 31.8% of the variance in resource optimisation, which has a strong positive relationship. Employees also reported high engagement in terms of ensuring productivity with minimal resource use (mean = 4.16), which aligns with the optimisation of AI.

These findings are supported by Bajwa et al. [74], Hanafi et al. [69], and Chui et al. [70], who identified that AI improves efficiency, operational performance, and sustainable resource management. In addition, [68] reported the role of the AI in optimisation and scheduling in real-time, and Nabeel [75] noted the efficiency of the AI in decision-making and cost reduction.

This implies that with AI support, the energy sector in Bahrain can afford to greatly transform how it manages its limited resources, such as water, energy, and raw materials, to be more efficient and waste-reducing. Nevertheless, the issues associated with infrastructure and explainable AI, which are outlined in the literature, need to be resolved to guarantee long-term scaling and integration.

The overall results indicate that AI can greatly enhance sustainable consumption, make a contribution to a reduction in emissions, and improve resource optimisation. Its findings validate and expand upon the arguments of the previous literature [39,48,67,74], especially with empirical evidence on the energy sector of Bahrain, a relatively unexplored setting.

For policymakers, the implications are clear: utilising AI not only contributes to the national sustainability goals but also aids the energy transition amidst decreasing hydrocarbon reserves. For industry leaders, the findings underscore the need to invest in AI-based tools and workforce education, so as to make the largest contributions to sustainable practices. Lastly, for researchers, the results demonstrate that more research should be conducted to understand how demographic variables, regulatory policies, and cultural forces influence the process of adopting and implementing AI to drive sustainability.

5.5. Theoretical Contribution: AI as a Conditional Enabler of Sustainable Transformation

The findings of this study contribute to current theoretical perspectives on digital sustainability by conceptualising Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a conditional enabler of, rather than an autonomous driver of, sustainability outcomes. The significant but moderate values of R2 for all three models (0.474, 0.303, and 0.318) show that AI explains a significant variance in sustainable consumption, emission reduction, and resource optimisation, but not in isolation. This is the evidence that technological adoption may not be enough to guarantee environmental progress without other complementary behavioural, organisational, and institutional mechanisms.

Moreover, the translation gap, that is, the gap between general AI usage and selected sustainability use in sustainability applications, shows the lack of alignment between technological innovation and ecological intentionality at the structural level. This finding underlines the socio-technical nature of sustainability transitions: the environmental potentials of AI emerge only when digital initiatives are strategically embedded in governance, cultural, and policy frameworks.

Theoretically, this research is part of the developing discussion on digital sustainability and socio-technical transition theory for empirically confirming that technology is a mediating mechanism in broader systemic interactions. It serves as a bridge between individual-level adoption (micro) and institutional match (macro), providing a framework of particular relevance to developing economies such as Bahrain, where digital maturity is developing, but policy integration is emergent. Although these theoretical contributions deepen the conceptual basis of AI-driven sustainability, the scope of the study and the methodological approach impose some limitations that still have to be recognised and overcome in future studies. Each dimension of sustainability was analysed in isolation, but the findings indicate possible structural interdependencies between them. As an example, sustainable consumption behaviours may indirectly contribute to optimising resources through lowering material throughput, and emission reduction efforts usually make use of efficient resource management systems. Future studies need to thus adopt structural equation modelling (SEM) or path analysis to measure the mediating and sequencing relationships between these constructs, thus producing a more comprehensive model of AI-enabled sustainability. The models (R2 ranged 0.30–0.47) provide evidence that AI explains a significant, but not complete, portion of sustainability performance. It means that even though AI serves as a powerful technological enabler, it exists within larger socio-technical arrangements that are determined by human capacity, organisational culture, and regulatory practices. On this score, the results are aligned with the socio-technical systems theory that argues that the transformative energy of technology is variable depending on whether it is embedded in the institutional and behavioural settings. In the context of the energy scene in Bahrain, where policy-driven innovation and developing digital infrastructure define the current situation, AI does not present a driver of sustainability on its own, but as an enabler that can accelerate the already existing institutional and organisational practices aimed at sustainable practice.

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are limitations to this study that do not exclude valuable possibilities of future investigation.

To begin with, the cross-sectional character of this design limits the possibility of making causal conclusions about the relationship between AI usage and the sustainability outcomes. The statistical correlations are strong, but cannot prove directionality and time stability. The future longitudinal or quasi-experimental studies may help understand whether the introduction of AI results in behaviour change over the years or whether the sustainability orientations of organisations are more likely to invest in the implementation of AI systems.

Second, the research is based on self-reported perceptions and behaviour, which might be affected by social desirability or subjective bias. This drawback highlights the necessity of incorporating objective performance indicators, e.g., actual electricity consumption (kWh) reductions, resource efficiency ratios, or certifiable CO2 emissions data. This type of measure would make the researchers match the perceptual data with quantifiable sustainability successes. Moreover, data were gathered at the individual level, when the constructs of resource optimisation and reduction in emissions are conceptualised at the organisational scale. Although the perceptions of employees are useful in informing about the realities of how operations take place, they may not be a true reflection of firm-level performance indicators. The combination of multi-level designs, which will involve the use of employee surveys and those of organisational indicators, needs to be incorporated in future studies to attain analytical uniformity.

Third, the absence of operational/organisational level of performance indicators would suggest that the study expands on attitudinal preparedness and reflects on realised efficiency. In terms of future research, a mixed-method design may be employed to achieve better research results by employing quantitative data with qualitative interviews to comprehend how employees and managers utilise AI tools and how they view their consequences concerning sustainability.

Finally, there is a limitation to the generalisability of the results due to the fact that the investigation was limited to the energy industry in Bahrain. Disparities in AI and policy frameworks and digital infrastructures differ significantly across sectors and countries. Comparative studies between the economies of the Gulf Cooperation Council or other developing worlds can help shed light on the moderating variables of the context, including regulation, cultural orientation, and the availability of digital infrastructure. Since the research involved only the energy sector in Bahrain, the research results must not be generalised to other areas or other countries without warning. The structural, regulatory, and technological conditions can have varied results in other areas.

These limitations can be overcome to make AI-based sustainability research more precise in theory and more practical in application. Future research should not focus on perception-based studies but on data-driven analysis that can prove the visible environmental impact. The research results are of an inherently contextual nature, as they demonstrate the characteristics of the specific policy framework, industry structure, and technological cycle of the energy industry in Bahrain. The results have been influenced by national efforts, including the National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP) and National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP), which inform the priorities of local sustainability. Accordingly, careful generalisation of these findings is warranted because conditions within an institution, economy, and infrastructure affecting the adoption of AI in Bahrain might not refer to other countries or sectors.

7. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on sustainability within the Bahraini energy sector, by considering three objectives: sustainable consumption, decrease in emissions, and resource optimisation, and by measuring self-reported behaviours and the use of AI among employees. Based on stratified random sampling, 230 employees took part, which is representative of a mature and technically competent workforce: the largest sub-groups were 55+ years (32.2%), males (59.1%), females (40.9%); education was higher with bachelor’s degree being the most prevalent (23.5%), followed by master‘s(18.3%); and the orientation towards a technical profession was high (engineers 19.1%, IT/AI specialists 17.4%, energy analysts/researchers 17. Interestingly, over 32.2% had over 10 years of technology experience, which might be a promising place to introduce AI-enabled practices. Data were collected via a researcher-designed questionnaire (Google Form) covering demographics and four constructs—AI use, sustainable consumption, emission reduction, and resource optimisation—each measured with five Likert items (1–5). Content validity was assured through expert review; reliability targeted Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.70; ethical protocols included informed consent, confidentiality, and anonymity. Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests indicated normality for all constructs (p > 0.05).

Descriptively, participants indicated moderate-to-high levels of AI engagement (overall M = 3.73), strong sustainable consumption (M = 4.04), active emission-reducing behaviours (M = 3.93), and high resource optimisation (M = 4.00). All hypotheses were supported with regression analyses. AI also significantly impacted sustainable consumption (B = 0.634 at t = 14.323, R = 0.688, R2 = 0.474, p = 0.000) and explained 47.4% of the variance, which is consistent with the literature showing AI nudges to pro-environmental decisions. It also played a crucial part in the reduction in emissions (B = 0.450, t = 9.950, R = 0.550, R2 = 0.303, p = 0.000), explaining 30.3% of the variance and reiterating the reviews that AI is energy-optimising and decreases CO2. Lastly, AI resulted in resource optimisation (B = 0.426, t = 10.316, R = 0.564, R2 = 0.318, p = 0.000), which explained 31.8% of the variance and supported the claim that AI contributed to efficiency and smart operations. Nevertheless, despite the commonality of AI implementation in employees’ daily life (M = 3.81), the item about “using AI to support sustainable choices” was somewhat lower (M = 3.88), which indicates the translation gap between general use of AI and sustainability-oriented use of AI.

To make the process faster, policymakers can include AI in the national energy-efficiency and decarbonisation strategies, whereas the leaders of industries must invest in decision support, predictive maintenance, and demand optimisation to transform sustainability intentions into tangible results. This research is one of the first Bahrain-based empirical studies on the overall impact of AI on consumption, emissions, and resource consumption, between individual behaviour and operational performance. Its limitations encompass a cross-sectional, self-reported study, measures adapted, sector- and country-specific situations, and objective data, which would encompass kWh savings or CO2 reductions. Future studies are advised to employ longitudinal and/or quasi-experimental designs, objective measurements of energy and emissions, and look at mediators and moderators. Practically, AI capabilities should be matched with sustainable decision-making, involve explainable AI, and match initiatives to the energy strategy in Bahrain to benefit at the system levels. Although this study adds to the emerging body of empirical research on the contribution of artificial intelligence to the attainment of sustainability, the results of the research are limited by the socio-economic and regulatory environment of Bahrain. The interaction of the adoption of AI, the mechanisms of governance, and the structural peculiarities of the energy sector restricts the direct generalisability of the results to other areas. In this regard, future studies must replicate this framework in other settings to confirm the strength of these relationships under other institutional environments.

The research confirms that AI is an important factor in boosting sustainable consumption, minimising emissions, and optimising resources in the energy industry of Bahrain. Nevertheless, the impacts are not complete and situationally constrained in terms of institutional, regulatory, and technological considerations. AI can therefore be perceived as an enabling factor to a larger socio-technical system instead of a self-sustainable stimulus. Future studies need to be longitudinal and multi-level, and combine objective performance measures and sectoral and regional differences to enhance empirical and theoretical accuracy.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics/IRB Approval Waiver signed by the relevant authority in accordance with national regulations in the Kingdom of Bahrain. The attached waiver confirms that: 1. The study was conducted with adult professional participants. 2. Participation in the questionnaire was entirely voluntary. 3. No personal or sensitive data were collected. 4. The study is classified as minimal-risk survey research. Therefore, does not require IRB approval under national guidelines and institutional practices in Bahrain.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified survey data and SPSS syntax are available from the corresponding author (Jaafer Mohammed Al-Mesaiadeen) on reasonable request due to privacy/ethical restrictions. Upon acceptance, a de-identified dataset, codebook, and analysis scripts can be deposited to an open repository (e.g., OSF/Zenodo link to be added).

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the AI and sustainability experts who provided content validity feedback on the instrument and the Bahrain energy-sector employees who participated.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders (if any) had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| NEEAP | The National Energy Efficiency Action Plan |

| NREAP | National Renewable Energy Action Plan |

| SDGs | The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- Rehman, A.; Ma, H.; Ozturk, I.; Ulucak, R. Sustainable development and pollution: The effects of CO2 emission on population growth, food production, economic development, and energy consumption in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 17319–17330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Xu, D. Relationship between energy consumption, economic growth and environmental pollution in China. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavič, P. Evolution and current challenges of sustainable consumption and production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wu, C.; Liu, J. Can artificial intelligence effectively improve China’s environmental quality? A study based on the perspective of energy conservation, carbon reduction, and emission reduction. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuett, J. Defining the scope of AI regulations. Law Innov. Technol. 2019, 15, 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.H.H.; Chowdhury, B.R.; Reza, S.A.; Shovon, M.S.S.; Karmakar, M.; Islam, M.R.; Ridoy, M.H.; Rahman, A.; Ripa, S.J. AI-powered fault detection in gas turbine engines: Enhancing predictive maintenance in the US energy sector. J. Ecohumanism 2025, 4, 658–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molęda, M.; Małysiak-Mrozek, B.; Ding, W.; Sunderam, V.; Mrozek, D. From corrective to predictive maintenance—A review of maintenance approaches for the power industry. Sensors 2023, 23, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassef, A.M.; Olabi, A.G.; Rezk, H.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Application of artificial intelligence to predict CO2 emissions: Critical step towards sustainable environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojadi, J.O.; Odionu, C.S.; Onukwulu, E.C.; Owulade, O.A. AI-enabled smart grid systems for energy efficiency and carbon footprint reduction in urban energy networks. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval. 2024, 5, 1549–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adanma, U.M.; Ogunbiyi, E.O. Artificial intelligence in environmental conservation: Evaluating cyber risks and opportunities for sustainable practices. Comput. Sci. IT Res. J. 2024, 5, 1178–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.H.; Rashdan, S.A.; Ali-Mohamed, A.Y. Towards effective environmental sustainability reporting in the large industrial sector of Bahrain. Sustainability 2021, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheed, R.A.R. Building public trust in Bahrain: Leveraging artificial intelligence to combat financial fraud and terrorist financing through cryptocurrency tracking. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarti, M.; Dubey, K. Benefits of energy efficiency programs for residential buildings in Bahrain. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 18, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuflasa, H. Renewable Energy in Bahrain: Background Paper; University of Bahrain: Zallaq, Bahrain, 2019; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Energy Unit. The Kingdom of Bahrain’s National Energy Efficiency Action Plan; Ministry of Electricity and Water Affairs & United Nations Development Programme: Manama, Bahrain, 2017; Available online: https://www.undp.org/bahrain (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Alnaser, W.E.; Tomaszkiewicz, M.; Buzaboon, A.; Alnaser, N.W. The need for artificial intelligence to encounter the impact of future climate change on the renewable energy potential in the Kingdom of Bahrain. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Open Innovation and Digital Transformation (OIDT), Manama, Bahrain, 12–14 March 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tazikeh, S.; Mohammadzadeh, O.; Zendehboudi, S.; Saady, N.M.C.; Albayati, T.M.; Chatzis, I. Energy development and management in the Middle East: A holistic analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 323, 119124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Badi, A.; AlMubarak, I. Growing energy demand in the GCC countries. Arab J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2019, 26, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhaldi, F.; Altaei, S. Theorising the concept of energy security in the Kingdom of Bahrain as an oil-exporting country. In Proceedings of the 2020 Second International Sustainability and Resilience Conference: Technology and Innovation in Building Designs (51154), Manama, Bahrain, 11–12 November 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Adewoyin, M.A.; Adediwin, O.; Audu, A.J. Artificial intelligence and sustainable energy development: A review of applications, challenges, and future directions. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval. 2025, 6, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriarte-Gallastegi, N.; Arana-Landín, G.; Landeta-Manzano, B.; Laskurain-Iturbe, I. The role of AI in improving environmental sustainability: A focus on energy management. Energies 2024, 17, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukoba, K.; Olatunji, K.O.; Adeoye, E.; Jen, T.C.; Madyira, D.M. Optimising renewable energy systems through artificial intelligence: Review and prospects. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 3833–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltersmann, L.; Kiemel, S.; Stuhlsatz, J.; Sauer, A.; Miehe, R. Artificial intelligence applications for increasing resource efficiency in manufacturing companies—A comprehensive review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunaiya, O.G.; Soyombo, O.T.; Ogunsola, O.Y. Sustainable energy solutions through AI and software engineering: Optimising resource management in renewable energy systems. J. Adv. Educ. Sci. 2022, 2, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaku, E.; Vyshka, E.; Kapçiu, R.; Shehi, A.; Smajli, E. Utilising artificial intelligence in energy management systems to improve carbon emission reduction and sustainability. Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu Terapan Univ. Jambi 2025, 9, 393–405. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Bahrain. Sustainability. 2025. Available online: https://www.bahrain.bh/wps/portal/en/!ut/p/z0/fcw9DoJAEEDhq2xDPSMq0PqTiBZqCduQASa4ArMIA_H4cgLLl3x5YCEDK7S4htR5oW7t3EbF5rrHNDkhpvfnGaNHmsRhfNzuLiHcwP4H68G9Px97AFt5Uf4qZKUMBUuAVPpZjb7YtE6a2vcBsixu9NKzqCGpjZDOIwc4ckfKtVE_uGoKcJonJSdUdgxDa_MfYHIHjg!!/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Al Astal, A.Y.M.; Ateeq, A.; Milhem, M.; Ali, S.A.; Allaymoun, M.; Al-Mesaiadeen, J.M. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices in Bahrain: A comprehensive analysis of sustainable development in the corporate and financial sectors. In Business Sustainability with Artificial Intelligence (AI): Challenges and Opportunities: Volume 2; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Aldada, A.; Alrasheed, R.; Khalifa, M. Sustainable development in Bahrain: Analysis of industry sectors, the economy, sustainable communities, the environment and the quality of government institutions. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASU International Conference in Emerging Technologies for Sustainability and Intelligent Systems (ICETSIS), Manama, Bahrain, 15–17 January 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 2007–2013. [Google Scholar]

- AlKhalifa, S. An Examination of the Integration of Sustainable Development Principles in Governmental Project Management in the Government of the Kingdom of Bahrain. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zayani, M.; Baher, M.; Al Beeshi, S.; Al Ajmi, H.; Alaghbari, M. The reality of SMEs and sustainable development from the perspective of the innovative economic vision of the Kingdom of Bahrain 2030. Int. J. Technol. Innov. Manag. 2023, 3, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.H. The path toward the 2030 Agenda: The implementation status of sustainable development goals in the large industrial sector of Bahrain. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 15393–15420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muamalah, R.; Ghazali, I. Bahrain’s economic evolution: A journey from the oil era to sector diversification. ALADALAH J. Polit. Soc. Law Humanit. 2025, 3, 270–282. [Google Scholar]

- Alsabbagh, M.; Alnaser, W.E. Transitioning to carbon neutrality in Bahrain: A policy brief. Arab Gulf J. Sci. Res. 2022, 40, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, K.; Rahman, S.M.; Khondaker, A.N.; Abubakar, I.R.; Aina, Y.A.; Hasan, M.A. Renewable energy utilisation to promote sustainability in GCC countries: Policies, drivers, and barriers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 20798–20814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabbasi, A.I. Sustainable Generation Expansion Planning with Renewables: A Case Study of Bahrain. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Information and eGovernment Authority. Kingdom of Bahrain Voluntary National Review Report on the SDGs: Key Messages and Statistical Booklet; Information and eGovernment Authority: Isa Town, Bahrain, 2025.

- Aldada, A.M.; Alrasheed, R.; Khalifa, M. Sustainable development in light of the Bahraini National Action Charter: An analytical study. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidan, E.; Al-Saidi, M.; Hammad, S.H. Sustainable development in the Arab world—Is the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region fit for the challenge? Dev. Pract. 2019, 29, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargın, S. Artificial intelligence, smart applications and sustainable consumption: A theoretical overview. İktisadi İdari Siyasal Araşt. Derg. (İKTİSAD) 2024, 9, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenow, S.; Pimenowa, O.; Prus, P. Challenges of artificial intelligence development in the context of energy consumption and impact on climate change. Energies 2024, 17, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayashot, Z.A. The contribution of AI-powered mobile apps to smart city ecosystems. J. Softw. Eng. Appl. 2024, 17, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A. AI-driven solutions for energy optimisation and environmental conservation in digital business environments. Asia Pac. J. Energy Environ. 2022, 9, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]