1. Introduction

As China shifts from rapid growth to high-quality development, traditional industrial policies have evolved toward new, value chain-centered industrial policies, with increasing emphasis on innovation policies such as research and development. Existing studies have extensively examined innovation policies from multiple perspectives—including theoretical interpretation, logical framework construction, and performance evaluation—producing systematic, quantitative, and evolutionary analyses [

1,

2,

3]. At their core, innovation policy assessments fall within the domain of public policy evaluation, where the key challenge lies in achieving a “soft landing” in the realization of public value. Adjusting governance models has therefore become essential [

4]. By improving cooperative production models, the functions of the public sector can be optimized and policy performance enhanced, thereby co-creating public value through shared preferences, collaboration, and networks [

5]. In the context of digital innovation and technological transformation, the reorganization of production factors has accelerated. Guided by a public value model emphasizing social circulation, business value creation driven by industrial circulation has been integrated, reshaping patterns of value co-creation among multiple stakeholders and promoting the effective convergence of public policy and governance [

2,

6]. However, limited attention has been given to another critical dimension of high-quality development—quality policy. Within the framework of new governance models, it is vital to establish systematic theories, structures, and behavioral foundations for quality policies, while innovating evaluation approaches and strengthening assessment effectiveness. Such efforts can guide both macro-level quality policy-making and micro-level quality practices, thereby deepening the integration of industrial, economic, and social high-quality development and advancing the construction of a modern quality governance system.

Despite the growing scholarly interest in innovation and industrial policies, research on quality policy performance evaluation remains limited in both scope and depth. At the theoretical level, most studies are grounded in the concepts of public value and new public governance, emphasizing administrative efficiency, legitimacy, and citizen participation [

7,

8]. However, these frameworks rarely consider the interaction between government and market mechanisms, which jointly determine policy effectiveness under the logic of value co-creation [

9,

10]. At the methodological level, conventional evaluation approaches—such as Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) [

11], fuzzy comprehensive evaluation [

12], and multi-criteria decision-making methods [

13]—tend to measure static efficiency or short-term performance but seldom capture the dynamic evolution and multi-dimensional coordination of policy tools. At the empirical level, research has focused mainly on regional or sectoral policies, such as environmental or innovation policies [

14,

15], while national-level quality policies—integrating supply, demand-, and environment-side instruments—remain largely unexplored. Moreover, few studies have examined the long-term evolution of policy systems spanning several decades within the paradigm of value co-creation [

16,

17,

18].

Therefore, a theoretical, methodological, and empirical gap exists in constructing a comprehensive and dynamic framework that integrates public value creation, market participation, and long-term policy evolution. This study addresses these gaps by developing a value co-creation-oriented framework for assessing the performance and evolutionary dynamics of China’s national-level quality policies, thereby enriching the theoretical foundation, enhancing methodological rigor, and strengthening empirical evidence for sustainable quality governance. The concept of quality policy can be understood broadly and narrowly. In the broad sense, it refers to the government’s measures for planning, organizing, coordinating, and controlling quality development, which are widely and persistently applied at both national and local levels to meet industrial demands and ensure sustainable economic and social development [

19]. In the narrow sense, quality policy refers to a combination of policies covering quality infrastructure, quality supervision, quality safety, quality innovation, and quality development. Driven by growth models and industrial planning needs, governments employ diverse tools to enhance public awareness of quality, improve the social environment for quality development, and raise the overall standards and management capabilities of major industries [

20]. In this study, quality policy is defined as single or combined measures adopted by national and local governments to meet industrial demands and ensure high-quality economic and social development, encompassing quality infrastructure, supervision, safety, innovation, and development. In fact, China began formulating and issuing quality policies as early as the 1970s, starting with the 1978 “Notice on Launching Quality Month Campaign,” which focused on product quality at the enterprise level [

21]. Unfortunately, systematic evaluations of quality policy performance have yet to be conducted, making this a pressing issue under discussion in both academic and policy circles. Two urgent questions require answers through performance evaluation: (1) Has the supply of quality policies achieved the intended effectiveness? (2) Has the supply process adequately considered market demand, and how well are policy supply–demand coordination and comprehensiveness ensured?

Existing policy performance evaluation methods can be broadly divided into three categories. The first category, based on public service value, constructs evaluation frameworks along dimensions such as ecological, economic, and social benefits [

22,

23,

24]. While effective in measuring policy processes and outcomes, these methods demand strong logical frameworks but often overlook structural considerations. The second category, based on input–output analysis, employs Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and related models to evaluate efficiency across multiple dimensions [

25,

26], including scale and technical efficiency. However, DEA is highly dependent on expert judgment and weights, which can inflate efficiency values. The third category employs propensity score matching with difference-in-differences (PSM-DID) to assess policy impacts, requiring comparable samples between experimental and control groups to detect policy shocks. Against this backdrop, this study adopts a value co-creation perspective to construct a classification framework for quality policies, establish dual-dimensional rules for assessing policy intensity and effectiveness, clarify the logic of policy evaluation, and forecast evolutionary dynamics [

27,

28]. By providing quality policies with both market influence and public service characteristics, this study aims to optimize policy supply–demand structures and efficiency, thereby supporting China’s industrial upgrading and high-quality development. Accordingly, to address the above methodological limitations and to integrate public-value and market-oriented logics within a unified lens, we articulate the study’s objective and sub-objectives as follows.

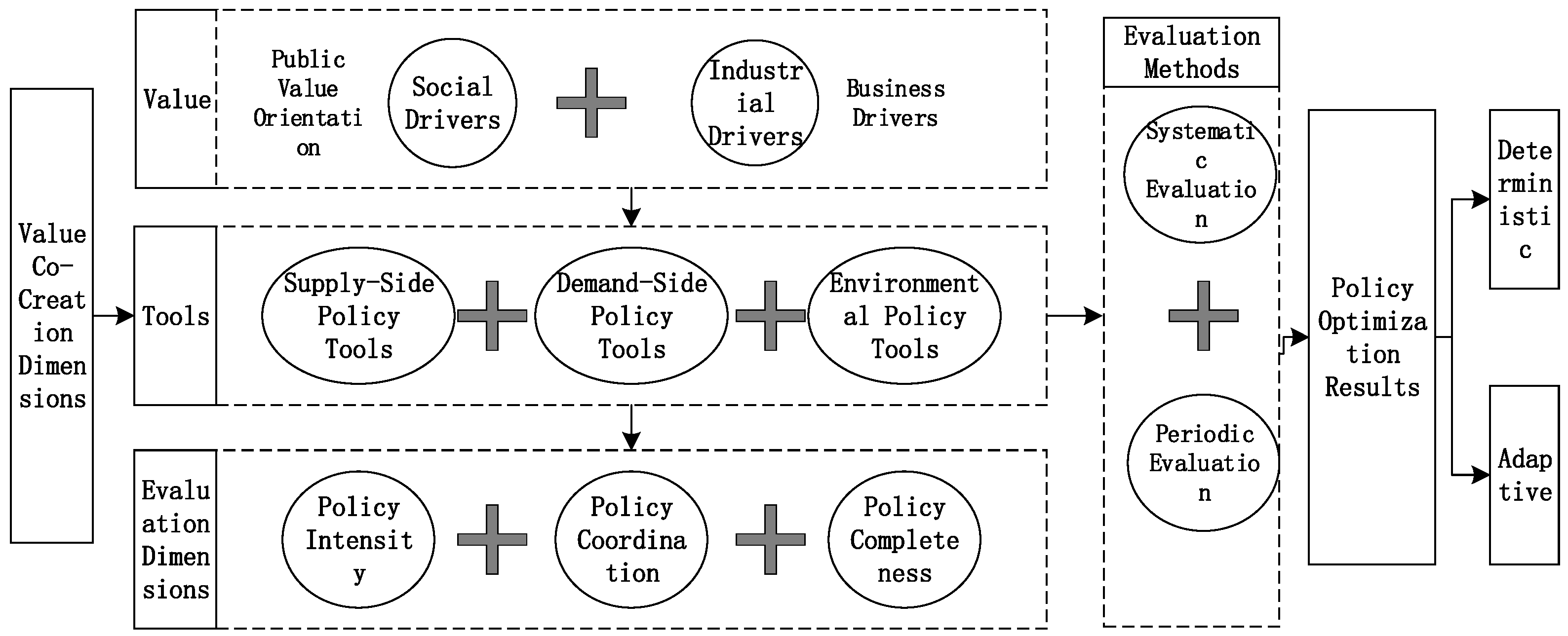

This study aims to build and apply a value co-creation-oriented framework to evaluate China’s quality policies (1979–2023). Specifically, we quantify intensity, coordination, and comprehensiveness in a unified system; estimate comprehensive effects and test evolutionary dynamics via punctuated-equilibrium and breakpoint analyses; examine alignment with the three industries; and formulate actionable, demand-side-oriented recommendations (see

Figure 1).

Despite the increasing recognition of quality policy as a cornerstone of high-quality development, its overall performance, coordination mechanisms, and long-term evolution remain insufficiently understood. Existing studies rarely integrate public value creation and market participation within a coherent analytical framework, and few provide longitudinal evidence capturing multi-dimensional policy dynamics over several decades. Moreover, empirical research seldom explores how these dynamics affect industrial structures and inter-sectoral linkages. Addressing these gaps is crucial for advancing both the theoretical understanding and the practical optimization of China’s quality governance system.

The main contributions of this study are as follows.

- (1)

Theoretical contribution: This study extends the application of value co-creation theory to quality policy evaluation by establishing an integrated framework that connects public value, market participation, and long-term policy evolution.

- (2)

Methodological contribution: It develops a multidimensional, dynamic evaluation model that jointly measures policy intensity, coordination, and comprehensiveness, introduces a punctuated-equilibrium-based evolution test, and integrates breakpoint analysis and AHP weighting to capture both static and dynamic policy characteristics.

- (3)

Empirical contribution: It conducts a longitudinal evaluation of 10,962 national-level quality policies issued between 1979 and 2023, revealing evolutionary stages, coordination effects, and dynamic linkages across the three industrial sectors. The results not only fill a long-standing gap in empirical quality policy research but also provide evidence-based insights for optimizing China’s quality governance system and improving the policy supply structure.

3. Quality Policy Performance Assessment Framework Under Value Co-Creation

3.1. Quality Policy Performance Evaluation System Led by Value Co-Creation

In the digital economy era, production factors are increasingly interconnected and reorganized, reshaping the logic behind quality policy choices [

35]. Driven by business value considerations, policy orientation has been shifting from a public-value-dominant model to a value co-creation model among multiple stakeholders. Commercial value creation promotes integration of quality policies with industrial upgrading, while public value considerations ensure alignment with governance needs. Together, these reinforce the effectiveness and stability of quality governance [

36]. The developmental trajectory of quality policies exhibits both long periods of stability and abrupt shifts, aligning with the punctuated equilibrium theory [

37]. Accordingly, this study proposes a value co-creation-oriented framework for assessing quality policy performance (see

Figure 1).

3.2. Weight Calculation for Quality Policy Performance Evaluation System

Based on the logical framework, this study employs the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and expert scoring to construct the evaluation index system. Five experts were invited, including three senior policymakers from the State Administration for Market Regulation and two academic researchers specializing in quality policy evaluation. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using the standard 1–9 scale, and the consistency of each judgment matrix was verified through the consistency ratio (CR), which was required to be below 0.1. When any inconsistency was detected, the corresponding pairwise judgments were reviewed and adjusted collaboratively until the threshold was met. All calculations were performed using the Yaahp 12.3 software, which automatically computed normalized weights and consistency indices for all hierarchical levels. After these procedures, the verified weights were assigned at each indicator level, and the final weighting structure is summarized in

Table 4.

Although AHP offers a structured and transparent approach for weight determination, it is not without limitations. This method relies on expert judgment, which introduces potential subjectivity and bias, particularly when the number of indicators is large or when experts have heterogeneous professional backgrounds. To mitigate this issue, we combined multiple expert opinions and verified consistency at each level, thereby enhancing the reliability of the resulting weights.

3.3. Collection and Statistical Analysis of Quality Policy Samples

The dataset consists of national-level quality policies retrieved from the Peking University Law Database (China Legal Information Database) for the period 1979–2023. Keywords included terms such as ‘quality management,’ ‘standardization,’ ‘metrology,’ ‘product quality,’ ‘quality brand,’ ‘quality award,’ ‘quality governance,’ and related terms for supply side, demand-side, and environmental-side policies. After multiple rounds of screening and verification, 10,962 valid policy documents were obtained.

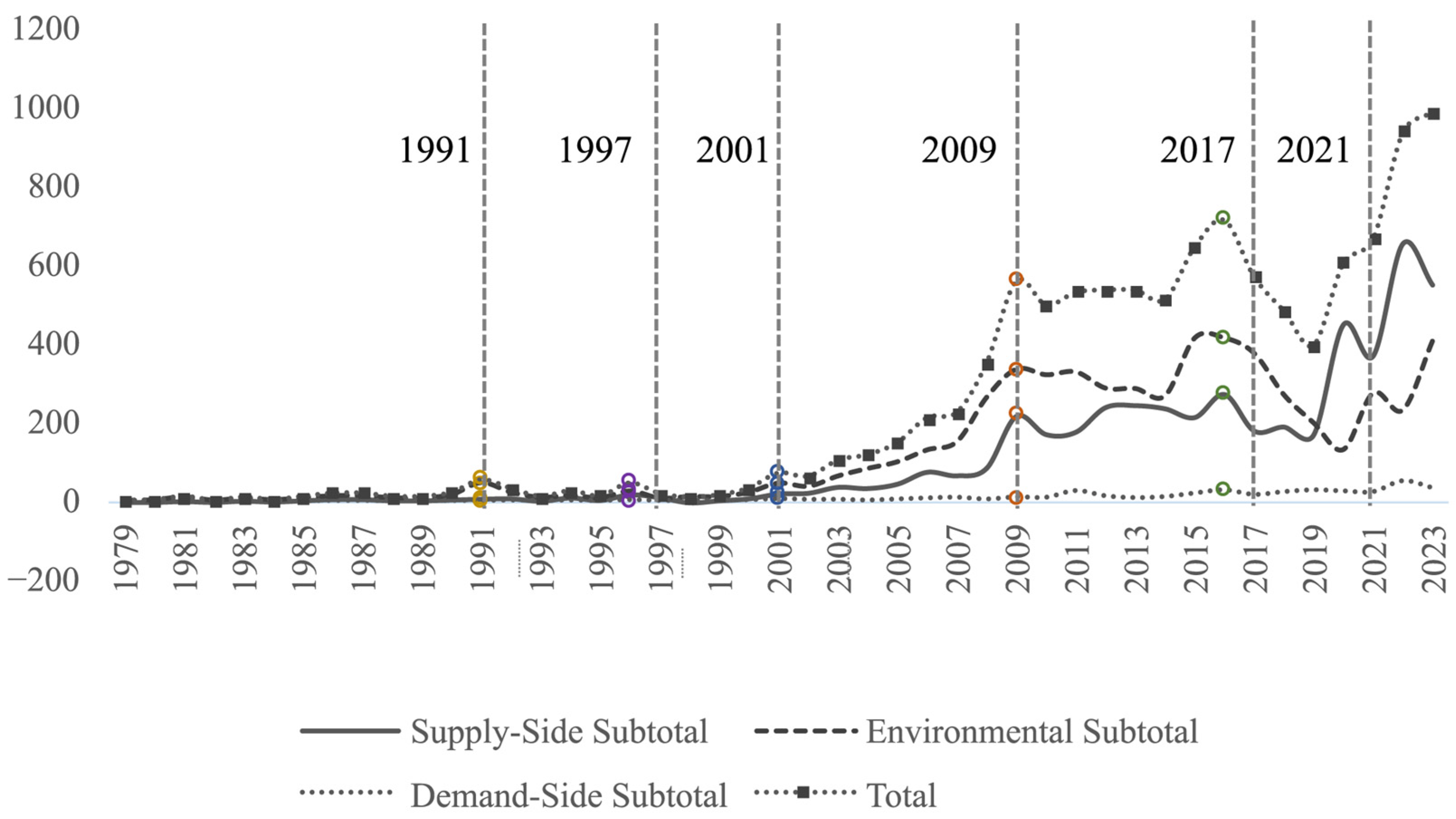

Figure 2 presents the yearly distribution of policies.

In the 44 years since the reform and opening-up, China’s quality policy has achieved long-term sustainable supply, but there are significant dimensional differences in policy numbers: environmental-side quality policies > supply side quality policies > demand-side quality policies. These differences have expanded over the years, with particular emphasis on the significant shortage of demand-side quality policy supply, which needs attention. Additionally, according to the discontinuity-equilibrium theory, China’s quality policy issuance followed a long period of balanced development and experienced key policy shift points in 1991, 1997, 2001, 2009, 2017, and 2021. Key documents and the historical context are summarized below.

The 13th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China pointed out in 1991 that economic work should focus on improving economic efficiency, with industrial production quality, variety, and efficiency showing significant progress. In 1996, the “9th Five-Year Plan” and the 2010 Vision clearly stated the need to improve China’s overall product quality, engineering quality, and service quality, marking the first national-level strategic document, the “Quality Revitalization Outline (1996–2010).”

From 2000, quality policies showed rapid growth, linked to China’s WTO accession and increasing foreign trade. Measures like the establishment of the National Quality Award in 2001 and the enactment of the Agricultural Product Quality Safety Law in 2006 further defined the path for quality development.

4. Quality Policy Performance Evaluation Results and Evolutionary Trend Analysis

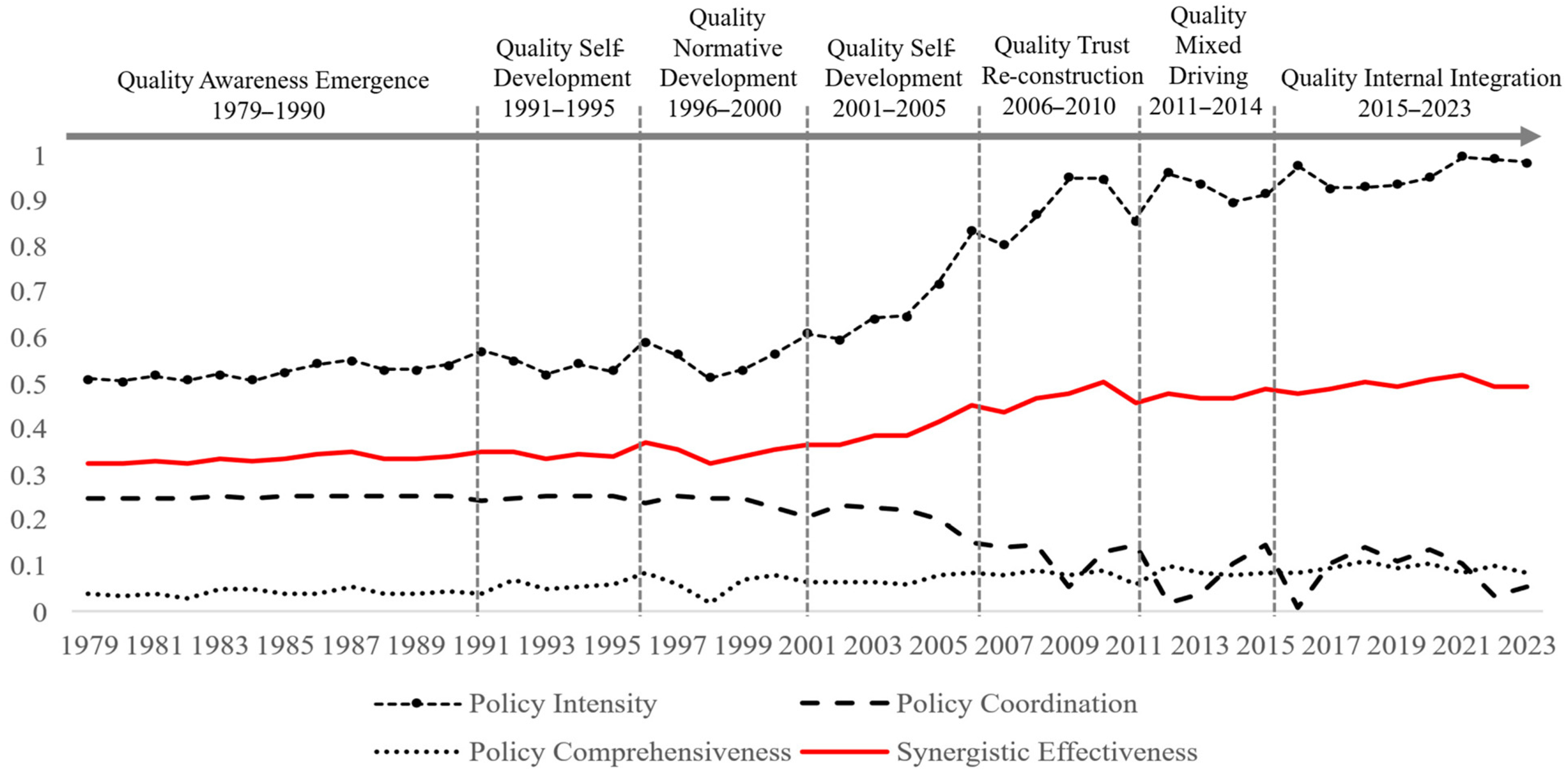

4.1. Quality Policy Performance Evaluation Values and Development Stages

Based on the quality policy assignment framework presented earlier, the policy intensity, effectiveness, coordination, and improvement values were calculated and converted to the Sigmoid scale to standardize the data. The comprehensive effect value of quality policies was then derived using a weighted average approach. The results are shown in

Table 5. The evaluation values are divided into four stages based on the following intervals: [0, 0.3] represents the “lightly imbalanced period,” (0.3, 0.5] represents the “general effect period,” (0.5, 0.8] represents the “good effect period,” and (0.8, 1] represents the “excellent effect period.” The results are visualized in

Figure 3, which illustrates the temporal evolution of quality policy performance across the four dimensions, and the corresponding development stages are further summarized in

Table 5.

From a dynamic development perspective,

Figure 3 clearly shows that the intensity, coordination, and improvement of quality policies have all exhibited a fluctuating upward trend, with policy intensity slightly higher than policy coordination and significantly higher than policy improvement. Policy intensity entered a phase of excellent supply strength around 2000 and reached a mature state in 2006. In contrast, policy coordination remained at an average or good level for a long period, achieving excellent coordination for the first time in 2006. Between 2010 and 2015, a distinct “W-shaped” fluctuation appeared, reflecting the self-adjustment and balance process between policy supply and demand, which aligns with the development pattern of overall policy effectiveness. Policy improvement, which reflects the coverage of supply, demand-, and environment-side dimensions, was in a lightly imbalanced state before 1999 but then showed a steady upward trend, eventually reaching a general improvement level. Nevertheless, it still lagged behind intensity and coordination, indicating that the limited coverage of demand-side policies remains a weakness in overall policy performance.

Based on these six turning points, China’s quality policy evolution can be divided into seven equilibrium development stages, as summarized in

Table 5. According to the framework of discontinuity–equilibrium theory, six local peaks in the synergistic effectiveness of quality policies were identified as breakpoints, occurring in 1991, 1996, 2000, 2006, 2009, and 2015. These points correspond to major turning periods in China’s Five-Year Plan cycles. The year 2000 marked the conclusion of the Ninth Five-Year Plan, during which China revised the Product Quality Law for the first time, signifying a new stage of product quality supervision. In 2009, following the melamine crisis, the government strengthened regulatory oversight and issued a large number of quality-related policy documents. By 2015, policy effectiveness became particularly evident as the country implemented supply side structural reforms.

4.2. Analysis of Policy Effectiveness Cycles

Considering the public and commercial values embedded in quality policies, this paper establishes a VAR model between quality policy supply and its comprehensive effect values. Using statistical tests such as LR test statistics, final prediction error (FPE), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Schwarz Information Criterion (SC), and Hannan-Quinn Information Criterion (HQ), the lag period of quality policy effects is tested. The results show that the optimal lag period for quality policies is one year, indicating that quality policies typically have a short-term stimulatory effect (

Table 6). This is consistent with the finding that quality policies serve as key tools for regulating industrial transformation and promoting high-quality economic development.

All multi-indicator evaluation criteria confirm that the optimal lag period is one year, significant at the 5% level. This finding implies that the policy cycle—from issuance to observable effectiveness—is approximately one year.

Economically, the one-year lag effect reflects the short-term responsiveness of industrial sectors to policy signals, as enterprises and local governments can quickly adjust production structures, quality control systems, and investment strategies following the release of new quality-related regulations or incentives. However, it also reveals the transitory nature of policy impacts: without continuous or follow-up measures, the stimulatory effects may fade, reducing the long-term cumulative influence of quality governance.

For policy design, this result highlights the importance of improving marginal efficiency and intertemporal coordination. Policymakers should align quality-related instruments with fiscal and monetary policies, strengthen the continuity of quality incentives, and ensure that follow-up mechanisms are introduced within one policy cycle. This would enhance the persistence of policy effectiveness, reduce uncertainty in implementation, and better achieve value co-creation between the government, market, and society.

4.3. Analysis of the Impact of Policy Coordination Effectiveness on Manufacturing Value-Added

Further analysis of the relationship between the quality policy coordination effect and the added value of manufacturing was conducted using a least squares regression model. The Chow breakpoint test was applied to test the significance of the six identified breakpoints in quality policies (

Table 7). The results show significant impacts of quality policies on manufacturing value-added, with increasing effectiveness and coordination over time.

In the process of analyzing the impact of quality policies on manufacturing, policy adjustments and optimizations become particularly necessary. Initially, quality policies had a limited effect on manufacturing, resulting in problems such as insufficient quantity supply and structural bias. However, over time, the effectiveness of quality policies has gradually been demonstrated. 1996 marked a turning point, with quality policies beginning to have a significant impact on manufacturing growth. By 2000, the impact of quality policy coordination on manufacturing value-added slightly weakened, but it was still statistically significant. In 2006, the effect of quality policies on manufacturing continued to grow, with the impact becoming highly significant by 2009, and the strength of this effect has continued to increase. For the future, adjusting and optimizing quality policies to address the structural problems in manufacturing is crucial. Policymakers should focus on improving manufacturing quality through optimized measures and promoting industrial structure upgrades, which will enhance overall industrial development and sustain growth. This will be an important direction for future policy-making, facilitating the optimization of China’s manufacturing industry and quality development.

4.4. Discussion and Implications

4.4.1. Comparative Positioning Against Prior Studies

Our findings—namely the persistent dominance of environmental- and supply side instruments over demand-side tools and the fluctuating yet upward trajectories of intensity, coordination, and improvement—are broadly consistent with the literature on policy system evolution and instrument mixes in innovation/industrial policy [

30,

42]. While OECD and EU member states tend to emphasize demand-pull and market participation earlier in the policy cycle, China’s quality policy mix remains more state-anchored and structure-oriented, prioritizing standard setting, supervision, and capacity building before deepening market co-incentives. This pattern echoes the “developmental-state” path reported in comparative governance studies while extending it to the domain of quality governance. Our longitudinal evidence (1979–2023) adds a multi-decade, multi-dimension perspective that has been limited in prior work, and it links stage shifts to macro planning cycles and salient events, complementing system-level narratives with empirical breakpoints.

Interpreting the results through value co-creation and public governance. The shift we document—from unilateral government provision (public-value logic) to dual government–market regulation (mixed commercial value), and toward pluralistic co-governance—aligns with the value co-creation paradigm in public administration [

42,

43]. In this lens, the observed coordination gains after major reform nodes can be read as incremental institutionalization of co-production: government clarifies rules and standards (environment-side), industry develops technological and organizational quality capabilities (supply side), and market actors signal preferences that should be met by demand-side instruments [

44]. The remaining weakness we find in “policy improvement/comprehensiveness” largely stems from insufficient coverage of demand-oriented tools; under a co-creation logic, expanding demand-side incentives is essential to close the loop between public value and market value [

45].

4.4.2. Cross-National Incentive Systems and Policy Learning

Comparative evidence from the United States, Japan, and Germany further contextualizes China’s system. The U.S. Baldrige framework demonstrates how reputational, socially administered recognition—anchored in professional associations—can sustain long-term quality improvement [

46]. Japan’s hybrid model layers national and prefectural honors while simplifying participation and emphasizing lifelong symbolic prestige, consistent with its collaborative public–private culture. Germany’s civil-society-driven awards illustrate how social legitimacy and “craftsmanship ethos” reinforce voluntary compliance and innovation diffusion [

47]. In contrast, China’s centralized, government-led incentive regime provides coherence and authority but underutilizes market and civic co-incentives. These global contrasts suggest that expanding socially sponsored awards, strengthening non-material recognition, and broadening eligible participants—including citizens and researchers—could improve inclusiveness and demand responsiveness.

4.4.3. Explaining the Observed Phenomena

The empirical short-cycle (≈1-year) lag we identify between policy issuance and measurable effects is compatible with stimulus-type industrial instruments and with the rapid administrative transmission of standards and supervision. Yet, durable gains in “policy improvement” require more than short-cycle pushes: they demand institutionalized demand-side channels (procurement, certification-linked consumer incentives, award systems with social legitimacy) that transmit market signals to policy design and firm-level quality investments [

48]. The “W-shaped” coordination fluctuation around 2010–2015 can be read as self-adjustment between expanding supply/environment instruments and still-nascent demand-side complements, a common transitory pattern when systems pivot from administration-dominant to co-governance [

49].

4.4.4. Critical Reflection on Data and Methods

Several caveats merit attention. First, our corpus—though comprehensive at the national level—does not fully capture local implementation heterogeneity or enforcement intensity; future work could fuse national-local text corpora and administrative enforcement data. Second, AHP weighting, while transparent, relies on expert judgment; robustness checks using unsupervised text mining (topic models, document embeddings) and data-driven instrument salience could mitigate subjectivity. Third, breakpoint identification and VAR-based lag inference remain correlational; causal identification (e.g., event studies leveraging exogenous shocks to specific instruments) would strengthen claims about dynamics and sectoral impacts.

4.4.5. Policy and Theoretical Implications

The findings reinforce a co-evolution view of quality governance: only when supply and environment-side foundations are complemented by sustained demand-side incentives can value co-creation be fully realized. Three directions follow.

- (1)

Rebalance the instrument mix. Expand demand-side mechanisms such as quality-linked procurement, consumer-subsidy programs, and socially sponsored awards.

- (2)

Institutionalize symbolic and reputational incentives. High-profile, socially recognized awards can generate long-term motivational effects that extend beyond fiscal rewards, enhancing trust and awareness.

- (3)

Strengthen coordination across policy cycles. Integrate quality policy planning with fiscal, technological, and digital-governance instruments to ensure continuity and cumulative gains. Together, these measures translate the value co-creation paradigm into actionable pathways for upgrading China’s quality governance toward greater inclusiveness, responsiveness, and sustainability.

In broader terms, these cross-national experiences highlight that international quality governance increasingly depends on hybrid incentive systems that combine governmental regulation, social participation, and market-based mechanisms. For China, aligning future policy instruments with such hybrid models could facilitate mutual policy learning, enhance compatibility with global quality standards, and promote the international diffusion of best practices in value co-creation-based governance.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

Grounded in the concept of value co-creation, this study establishes a multidimensional evaluation framework for assessing the performance of China’s national-level quality policies from 1979 to 2023. The analysis reveals notable structural imbalances in policy supply: environmental-side instruments remain dominant, followed by supply side measures, while demand-side policies are underrepresented and insufficiently developed. From a dynamic perspective, policy intensity, coordination, and comprehensiveness have all shown a fluctuating upward trend. Among these dimensions, intensity is consistently the highest, whereas policy improvement—particularly within the demand-side dimension—emerges as the principal weakness. Thus, optimizing the policy supply structure and strengthening inter-dimensional coordination are essential for future improvement.

Using discontinuity–equilibrium theory, six major breakpoints (1991, 1996, 2000, 2006, 2009, and 2015) were identified, corresponding to key transitions in China’s Five-Year Plan cycles. These inflection points delineate seven equilibrium stages of policy evolution: the awareness awakening period (1979–1990), self-development period (1991–1995), normative development period (1996–2000), externally driven period (2001–2005), trust reconstruction period (2006–2010), mixed driving period (2011–2014), and internal integration period (2015–2023). The results indicate that China’s quality governance has evolved from unilateral government provision focused on public value, to hybrid government–market regulation guided by mixed commercial value, and finally toward pluralistic governance underpinned by value co-creation. The Vector Autoregression (VAR) analysis further demonstrates that quality policies have a one-year lag effect, underscoring their short-term stimulatory role in promoting industrial transformation and high-quality growth. However, without continuous follow-up and coordination with broader macroeconomic instruments, their long-term cumulative effects remain limited.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

To enhance the effectiveness, sustainability, and inclusiveness of China’s quality policies, this study proposes differentiated short-term and long-term recommendations aligned with the empirical findings.

- (1)

Short-Term Recommendations

First, expand the supply of demand-oriented quality policies to address the structural deficiencies identified in the empirical results. Improving the balance among supply, demand-, and environment-side instruments will strengthen coordination and enhance responsiveness to market and consumer needs.

Second, improve the synchronization and timeliness of policy implementation. Given the one-year lag in policy effects, coordination among quality, fiscal, and monetary policies is essential to maximize the short-term stimulatory impact. Establishing an integrated quality policy coordination platform can help reduce redundancy, align objectives, and improve marginal effectiveness during short policy cycles.

Third, prioritize key industries to ensure differentiated policy impacts. Manufacturing (the secondary industry) should remain the main focus, emphasizing digital quality management, process standardization, and smart manufacturing. The primary industry should strengthen traceability and certification systems, while the tertiary industry should focus on service quality improvement and mechanisms for enhancing consumer trust.

- (2)

Short-Term Recommendations

First, institutionalize a multi-stakeholder governance system within the value co-creation paradigm. Quality governance should evolve toward a collaborative model involving government, enterprises, industry associations, and consumers. Building a comprehensive legal framework, encouraging local regulatory participation, and promoting inter-regional coordination will support the transition from quality management to quality governance.

Second, establish long-term mechanisms for policy continuity and feedback to mitigate the transient nature of quality policies. Periodic evaluations and adaptive adjustments can maintain policy consistency and implementation stability. Incorporating digital monitoring and big-data feedback systems would further enhance transparency and responsiveness.

Third, promote industrial differentiation and long-term structural balance. For the primary industry, policies should emphasize green certification and ecological branding; for the secondary industry, innovation-driven competitiveness and global standard alignment; and for the tertiary industry, improved service quality and digital governance. These differentiated strategies will foster sustained industrial upgrading and consolidate quality as a long-term driver of high-quality development.

5.3. Summary

Overall, China’s quality policy system has continuously improved but still faces challenges related to supply balance and policy continuity. Implementing short-term measures to strengthen coordination and responsiveness, together with long-term mechanisms for sustained governance and industrial differentiation, can help advance a value co-creation model that integrates government, market, and society to achieve high-quality development. It should be acknowledged that the AHP approach relies on expert judgment, which may introduce subjectivity. Although consistency checks were applied to ensure reliability, future research could address this limitation by incorporating complementary quantitative or data-driven weighting methods. Beyond the national context, the analytical framework and empirical findings presented in this study also offer insights for international quality governance. As countries worldwide pursue sustainable and inclusive development, the value co-creation-based approach provides a transferable lens for balancing governmental authority, market incentives, and social participation. Applying this framework in comparative settings could foster shared learning and enhance policy interoperability within the global quality governance landscape.