Abstract

Grounded in protection motivation theory, this study investigates the influence mechanisms of different instructional media and instructional models on students’ green behavior intentions. Employing a 2 (Instructional Media: Paper-based/Digital) × 2 (Instructional Model: Lecture-Based/Gamified) between-subjects experimental design, it examines the effects of instructional media and instructional models in sustainable laboratory safety education on students’ green behavior intentions, as well as the mediating role of protection motivation decision factors (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, response efficacy, self-efficacy). The results indicate that instructional media influence students’ intention to engage in green behaviors through perceived severity, whereas instructional models positively affect this intention by enhancing self-efficacy. Aligning instructional media with instructional models positively impacts students’ green behavior intention. In the process of sustainable laboratory safety education, the interaction and applicability of multiple factors within instructional strategies should be considered.

1. Introduction

University laboratories, as vital hubs for research and teaching, face multiple challenges in their construction and operation, including high resource consumption and significant environmental impacts. Research indicates that energy consumption in Chinese university laboratories is 3.1 times that of teaching buildings on the same campus, far exceeding that of other building types and showing an upward trend [1]. This situation not only imposes substantial economic pressure on universities but also conflicts with national energy conservation and emission reduction policy goals. Issues such as chemical use and waste disposal during laboratory construction not only exert substantial environmental pressure but also pose potential safety hazards [2]. Research indicates that human factors, particularly inadequate safety training for laboratory personnel, have been the primary cause of university laboratory accidents in China over the past two decades, highlighting deficiencies in safety management and culture within academic laboratories [3]. Simultaneously, since university laboratories use far fewer materials than industrial facilities and conduct smaller-scale experiments [4], the potential hazards to humans and the environment are often underestimated. Some studies show that improper handling of laboratory waste can lead to soil and water pollution, posing long-term threats to surrounding ecosystems [2]. Facing these challenges, safety education and the dissemination of sustainable development concepts have become essential prerequisites for access to university laboratories.

Education is regarded as a fundamental element in promoting sustainable development by equipping people with knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes that support it. However, traditional education systems exhibit certain limitations in terms of distance, flexibility, and interactivity [5]. With the rapid advancement of information technology and internet infrastructure, an increasing amount of education is conducted in e-learning environments [6]. Video-based learning offers advantages such as easy device access and rich interactivity [7]. For instance, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) represent a new web-based instructional model characterized by ease of use, low cost, self-directed learning, and abundant resources [8]. The rise of online instructional models has revolutionized network education in the information age. Nevertheless, online education models still face numerous challenges in practical application. Current research on online education primarily focuses on shortcomings such as technical accessibility, low completion rates, and a lack of immediate feedback [9]. Simultaneously, it grapples with pain points like low student engagement, lack of motivation, and poor learning experiences, often overlooking the critical role of the information reception-cognitive processing-behavior formation process in enhancing students’ willingness to adopt green behaviors. Therefore, how to effectively strengthen students’ green behavior intentions during online safety education in sustainable laboratories has become a pressing issue requiring urgent resolution.

Digital platforms introduce technology into teaching, adding another advantage by improving learning efficiency in education and deepening knowledge through experiential learning. These tools, including virtual simulations, content gamification, interactive quizzes, and exams, enhance student engagement, making learning more enjoyable and memorable [10]. Gamified education has tremendous potential to address these challenges and to improve learning outcomes [11]. Games can sustain students’ attention for hours while delivering guided, immersive learning experiences [12]. Integrating game elements into real classroom settings requires consideration of numerous complex factors, including instructional media (paper-based or digital), educational objectives (such as knowledge acquisition or skill development), and instructional models, all of which influence actual teaching outcomes [13]. While extensive research has examined the effects of game-based learning on cognitive and motivational variables, a gap persists between academic studies and teaching practice due to the lack of targeted designs addressing specific instructional goals within particular scenarios.

Based on the information medium, past literature has identified two types of instructional media: paper-based and digital [14]. The high cost and difficulty of developing digital media [15] hinder large-scale teaching implementation in real classrooms. Paper-based media has emerged as a sustainable, cost-effective approach that facilitates integrating education into classrooms. While teaching effectiveness varies across media formats and contexts, research on sustainable online laboratory education scenarios remains insufficient and warrants further exploration.

To further explore the aforementioned research limitations and delve into the underlying mechanisms through which instructional strategies influence behavioral intentions, this study adopts Protective Motivation Theory (PMT) as its core theoretical framework. Although models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) are widely used to predict behavioral intentions [16], they primarily focus on social cognitive factors, such as attitudes and subjective norms. Consequently, their explanation of how external interventions drive behavior by altering individual risk perceptions and coping beliefs remains somewhat abstract. In the context of sustainable laboratory safety—which emphasizes risk perception and capability building—students’ behavioral willingness is driven not only by social pressure but also, more directly, by their assessment of potential threats and their own risk-mitigation capabilities. PMT’s unique dual-path structure offers a more nuanced explanation of how instructional strategies influence risk perception and safety compliance [17], making it more suitable than TPB for the laboratory risk perception context of this study.

Therefore, this study aims not only to compare the influence mechanisms of different instructional media and modes but also to examine their differentiated mediating effects through PMT’s dual pathways. Accordingly, we will employ a 2 × 2 between-subjects experimental design to systematically investigate the interactive effects of instructional media (print vs. digital) and instructional mode (lecture-based vs. gamified) on students’ green behavioral intentions. The anticipated outcomes of this study will not only expand the application of PMT in sustainable education but also provide a solid theoretical foundation for designing more developmentally informed laboratory safety education programs.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Formulation

The core objective of this study is to uncover the intrinsic mechanisms through which teaching media and modes influence green behavior intentions, with the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) providing an ideal explanatory framework. This section will systematically elaborate on the theoretical foundations underpinning this research and introduce specific research hypotheses based on the following three components.

2.1. Green Behavior Intention in Sustainable Laboratory Safety Education

Sustainable laboratory practices fundamentally involve applying environmental principles to the daily operations of scientific laboratories to minimize their ecological footprint. Waste management constitutes a core component. Given the hazardous nature of many laboratory wastes, implementing proper waste management within laboratories is critically essential. Sustainable practices emphasize reducing waste at the source, promoting reuse and recycling whenever possible, and ensuring responsible disposal of hazardous materials [18]. Therefore, sustainable laboratory safety education is crucial for ensuring safety by enhancing individuals’ knowledge and skills related to safe behavior practices [19]. Simultaneously improving access to safety knowledge and raising awareness of sustainability can shift perceptions of risk, ultimately promoting behavioral change [20,21]. Researchers have developed and validated various educational formats for laboratory safety education in e-learning environments, such as video-based instruction [22], websites [23], and augmented reality (AR) programs [24].

Behavior intention, within the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), refers to an individual’s subjective judgment of the likelihood of initiating a specific behavior, reflecting their intention to engage in that action or the effort they are prepared to invest [25]. Based on their social, cultural, and personal characteristics, individuals in each community exhibit varying attitudes and behaviors toward the environment. These behaviors may be positive and pro-environmental, or negative and anti-environmental [26]. Green intention (GI) and green behavior (GB) refer to intentions and actions that do not harm the environment and may even benefit it [27]. Research by Sultan et al. indicates that many contemporary environmental issues stem directly or indirectly from human misbehavior and harmful behavioral intention. Despite significant technological advancements in environmental solutions, translating these achievements into sustainable green intentions and behavior remains challenging [28]. Green intention constitutes an integral dimension of individual decision-making and personal green behavior [29]. Consequently, perceptions of environmental behavior and intentions among educated younger generations, such as students, have garnered significant attention. Students have matured sufficiently to recognize the severity of ecological degradation and recognize the necessity of taking action to address these issues [30]. However, students’ insufficient self-efficacy and green behavioral intention often constrain the emergence of actual green behaviors.

Existing research has identified key factors through which various educational formats influence users’ green behavior intention. For instance, a video-based online instructional model that engages students in discussions, requires completion of quizzes and final exams, and culminates in a graduation score effectively overcomes temporal and spatial constraints. This approach delivers complex sustainability knowledge in a standardized, scalable manner, significantly reducing barriers to learning and facilitating knowledge dissemination to a broader audience [31]. This instructional model offers advantages such as excellent device accessibility and rich interactivity [7]. Research by Wenya Xu et al. indicates that participants in sustainability education delivered via digital platforms demonstrate significantly higher levels of environmental knowledge [5]. Concurrently, studies by Werbach, K. et al. show that integrating gamification into online education—applying game design elements and mechanisms in non-game contexts to support learning and encourage learner engagement [32]—can yield positive outcomes in educational settings when implemented appropriately [33]. Specifically, gamification enables the integration of game-like features and mechanisms into instruction, transforming learning into a more enjoyable process, enhancing learners’ self-efficacy, and thereby fostering behavioral intention [34,35]. However, systematic and in-depth research on how online educational models influence individual or collective green behavior intention remains scarce.

2.2. Gamified Instruction

Gamification is defined as “the use of game elements in non-game contexts” [35]. Its successful application across marketing, health, social, management, and entertainment fields has drawn educators’ attention [36]. In education, gamification aims to modify student behavior, spark interest in course content, and boost motivation and engagement.

2.2.1. Instructional Media and Information Processing Theory

Instructional media refers to the tools and media used to collect, transmit, store, and process educational information. It serves to carry and convey information during the teaching process, helping establish connections between teachers and students while enhancing teaching efficiency. Based on information carriers, past literature has identified two types of instructional media: paper-based and digital. Digital media, such as computers and tablets, are used for designing digital games. Conversely, paper-based media such as cards or other non-electronic tools offer a technology-independent, non-digital approach that facilitates easier student engagement in game activities [14,37]. However, research comparing the impact of paper-based versus digital media on learning outcomes remains scarce, and existing findings are inconsistent. For instance, one study found no significant difference between paper-based and digital media in improving students’ science learning outcomes. At the same time, another reported significantly higher performance among students taught via digital media compared to paper-based groups [37]. Research on sustainability education using media demonstrated that both paper-based and digital media enhanced students’ knowledge and attitudes [38]. Conversely, another study reported that the paper-based media group outperformed the digital media group in vocabulary learning and knowledge retention [14]. Therefore, further research is needed to accurately assess the impact of paper-based and digital media on students’ green behavior intentions.

Information processing theory posits that the human cognitive system resembles a computer’s information processing system, viewing cognitive processes as sequences of input, encoding, storage, retrieval, and output [39]. Paper-based media facilitates deeper construction of mental models in “linear long-text” contexts, thereby reducing working memory load. In contrast, digital media promotes instant feedback and rapid navigation in multimedia and interactive contexts [40]. Research by Rutten et al. indicates that digital environmental education with multimedia and interactive design significantly enhances deep knowledge processing and transfer [41].

In summary, digital media outperforms print media in knowledge-gain effects for sustainable laboratory safety education, more readily enhances user self-efficacy, and thus positively predicts green behavior intentions. Based on this, the study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

In sustainable laboratory online safety education, digital media will elicit higher green behavior intention than paper-based media.

2.2.2. Instructional Model

An instructional model refers to the stable, structural form of instructional activities conducted within a specific environment, guided by certain educational philosophies, teaching theories, and learning theories [42]. It defines teaching objectives, procedures, teacher-student roles, instructional conditions, and evaluation methods [43]. The basic sequence of traditional instructional models is: stimulating learning motivation, reviewing prior knowledge, presenting new knowledge, consolidating application, and assessing learning outcomes. This model supports the teacher’s leadership role by aiding in classroom organization, management, and control. However, it fails to address the specific needs of individual students, and teachers receive only limited feedback to assess students’ comprehension [44]. It is unrealistic to expect students to maintain focus during prolonged lectures. Consequently, digital platforms integrate technology into teaching to enhance educational outcomes. These tools include virtual simulations, gamified content, interactive quizzes, and assessments, making learning more engaging and memorable by actively involving students [10].

When activities are perceived as enjoyable, gamified learning occurs. It helps students find meaning in their tasks or studies, actively engages their minds through iterative thinking, and provides opportunities for social interaction. When game elements are integrated into lecture-based online education models, they offer students contextually acquired knowledge, thereby developing holistic cognitive, creative, physical, social, and emotional skills [45]. Effective feedback is a powerful tool for enhancing learners’ motivation and capabilities [46]. Mechanisms such as instant feedback, level progression, and repeatable challenges in educational gamification provide learners with affirmation and guidance for their correct behaviors. These mechanisms effectively build their sense of efficacy and increase their willingness to engage in desired actions. Research indicates that websites utilizing augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR) technology enhance students’ understanding of sustainability concepts compared to traditional lecture-based teaching, increasing information retention by 40%. Furthermore, according to Liu et al. (2024), big data analytics can be employed to assess student engagement and comprehension on these platforms, as well as to refine these learning processes to foster changes in green behavior [47]. Chittaro et al. directly compared the effectiveness of interactive game simulations versus non-interactive videos in emergency training. They found that interactive game simulations significantly outperformed non-interactive videos in knowledge retention and risk perception, while also fostering stronger motivation for self-protection [48].

Based on three forms of learning experiences: context-based cognitive experiences, collaborative social experiences, and motivation-based agency experiences. Learners can acquire tacit knowledge in cognitively authentic game environments, experience embodied cognition, while game elements and feedback mechanisms stimulate learning motivation and support metacognitive processes [49]. Knowledge transmission in traditional lecture-based education remains abstract and passive. Though efficient, it fosters passive learning and fails to fully engage students. However, research on gamification in occupational safety training reveals that when virtual simulation—a gamification tool—is applied to safety training, abstract safety rules are transformed into concrete, perceptible challenges, thereby enhancing learner engagement and risk awareness [50]. Gamification effectively builds knowledge, develops practice, and explores experiences and impacts by constructing compelling virtual scenarios [51].

In summary, when a traditional lecture-based instructional model integrates gamification elements, it optimizes users’ cognitive and agency experiences, thereby stimulating their intention to engage in green behaviors. Based on this, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2.

In online safety education for sustainable laboratories, a gamified education model can generate higher green behavior intentions than a lecture-based model.

2.2.3. Interaction Effect

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) refers to the mental or informational burden imposed on an individual’s cognitive system during learning or task execution [52]. CLT posits that the human cognitive system has limited processing capacity, capable of handling only a finite amount of information within a short timeframe. The CLT identifies three types of cognitive load: Intrinsic Cognitive Load (ICL), Extrinsic Cognitive Load (ECL), and Beneficial Cognitive Load (GCL) [53].

Digital media inherently feature dynamic visuals, hyperlinks, and interactive elements. While these can boost motivation, research confirms that poorly designed digital media significantly increase ECL, thereby distracting learners from core instructional content [54]. Gamified instruction, through its inherent goal-orientation, immediate feedback, and narrative structure, redirects cognitive resources diverted by digital media back toward learning itself. Research indicates that carefully designed gamification can transform ECL into GCL by guiding learners toward deeper cognitive processing [55]. Thus, in high-ECL-risk digital media environments, gamified instruction provides sufficient cognitive resources to foster green behavior intention by reducing ECL while enhancing GCL. This combined effect significantly outperforms using either digital media or gamified instruction alone.

Research indicates that learners experience inherently lower ECL when using paper-based materials, as working memory is not consumed by extraneous interactive elements [54]. Lecture-based instruction, while highly efficient for information delivery, offers low interactivity. Given the inherently low ECL of paper-based media, lecture-based instruction does not significantly increase ECL. However, it also lacks the gamification mechanisms that effectively stimulate GCL. Consequently, although the total cognitive load remains low with paper-and-lecture instruction, insufficient cognitive resources prevent learners from engaging in deep cognitive processing. This leads to low motivation, limited learning effectiveness, and consequently, restricted stimulation of green behavior intention.

It can thus be inferred that in sustainable laboratory online safety education, the combination of instructional media and models does not simply add up. Instead, it significantly interacts with green behavior intention by influencing the dynamic balance between learners’ ECL and GCL.

H3.

In sustainable laboratory online safety education, instructional media and instructional methods exhibit a significant interactive effect on green behavior intention.

2.3. Conservation Motivation Theory and Decision Factors

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) was first proposed by Rogers in 1975. This theory posits that an individual’s decision to engage in protective behaviors is governed by two cognitive processes—threat appraisal and coping appraisal, which involve four protection motivation factors: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, response efficacy, and self-efficacy [56,57]. Milne et al.’s meta-analysis of PMT indicates that, as a mediating framework, PMT has been successfully applied in numerous studies to explain how health or safety interventions exert their effects [58]. Furthermore, existing research demonstrates that enhancing these four protective motivation factors promotes individuals’ adoption of proactive coping behaviors to mitigate risk [59]. Perceived severity and perceived vulnerability emerge within the threat assessment cognitive process [60]. Rogers defines perceived severity as an individual’s perception of the degree to which a behavior may harm them, while perceived vulnerability refers to an individual’s belief in their likelihood of being harmed [56]. In the sustainable laboratory context, this study defines severity as students’ perceived threat level to their safety from a behavior, and susceptibility as the perceived likelihood of safety threats arising from a behavior’s consequences. Regarding the relationship between severity and behavioral intention, prior research indicates that heightened perceived severity motivates protective behavior: individuals who believe current harmful behaviors pose safety threats tend to adopt protective or consumption behaviors [61,62,63]. Beyond understanding the perceived threat level of destructive behaviors to personal safety, a higher likelihood of this threat occurring is more likely to lead to greater behavioral intention [64]. Taylor and Thompson’s research indicates that the presentation format of information significantly influences risk perception. Compared to abstract text, vivid and concrete audiovisual information more effectively evokes individuals’ imagination and emotional resonance, thereby making them perceive risks as closer to themselves [65]. For example, a study in Iran targeting agricultural students at a green university found that when experimental cases of waste-liquid pollution were presented alongside vivid images and data, perceived susceptibility was significantly higher than in the low-intensity text group. This indirectly increased green behavioral intention through perceived susceptibility and perceived severity in the threat assessment process [66].

Response efficacy and self-efficacy emerge during the coping assessment [67]. Reactive efficacy refers to individuals’ confidence or perception regarding the effectiveness of protective or preventive behaviors, representing outcome expectations for subsequent behavioral choices. Self-efficacy denotes an individual’s perceived confidence or belief in their capacity to engage in coping assessments [68]. Both response efficacy and self-efficacy increase the likelihood of adaptive and effective coping behaviors [69]. Past literature has examined the relationships among response efficacy, self-efficacy, and behavioral intention from various perspectives. For instance, Jensen and Sørensen found that self-efficacy is a significant predictor of pro-environmental behaviors, such as waste recycling or monetary donations [70]; Floyd et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 65 studies on conservation motivation theory, confirming that response efficacy and self-efficacy are associated with behavioral intention [59]. Cox et al. identified four variables—severity, susceptibility, response efficacy, and self-efficacy, which can promote consumer selection of health-promoting products, with response efficacy and self-efficacy being the most critical indicators [71]. Landers and Armstrong’s research model demonstrates that gamification elements optimize training outcomes by enhancing self-efficacy and response efficacy. Incorporating gamification in training alters perceptions of training efficacy, and this sense of efficacy correlates with all subsequent training outcomes—including responses, learning, behavioral change, and organizational results [72].

Based on the above empirical findings, the following research hypotheses are proposed:

H4a.

Perceived vulnerability mediates the effect of instructional media on green behavior intention.

H4b.

Perceived severity mediates the effect of instructional media on green behavior intention.

H4c.

Rresponse efficacy mediates the effect of instructional media on green behavior intention.

H4d.

Self-efficacy mediates the effect of instructional media on green behavior intention.

H5a.

Perceived vulnerability mediates the effect of instructional models on green behavior intention.

H5b.

Perceived severity mediates the effect of instructional models on green behavior intention.

H5c.

Response efficacy mediates the effect of instructional models on green behavior intention.

H5d.

Self-efficacy mediates the effect of instructional models on green behavior intention.

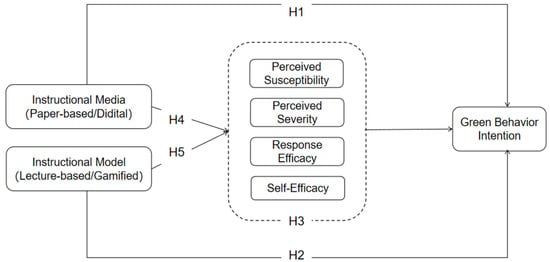

The research model for this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Experimental Design

The study aims to examine the effects of instructional media, instructional models, and their interaction on students’ green behavior intentions within a sustainable laboratory safety education context. A 2 (paper-based media/digital media) × 2 (lecture-based teaching/gamified teaching) between-subjects experimental design was employed. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four experimental groups. Learning tasks elicited changes in participants’ protective motivation decision factors, with pre- and post-tests measuring shifts in students’ green behavior intentions.

3.2. Experimental Material Design

For this study, the waste classification-treatment-recycling process in a sustainable laboratory was selected as the theme for designing the experimental materials. Consequently, all participants were required to study the same core safety education knowledge points.

Participants accessed the online laboratory education through a specialized interface, as illustrated in Figure 2. The core task involved receiving various waste streams generated by a virtual experimental platform and establishing a sustainable green laboratory through three key steps: proper classification, safe disposal, and resource recovery. The webpage interface displayed the user’s avatar, current level, and a progress bar for points at the top. The learning process was structured as a green laboratory challenge mission. Level 1: Participants drag different types of waste into the correct bins. Each correct classification provides instant feedback and unlocks knowledge points about the chemical substance, teaching students about inherent hazards. Level 2: Participants respond to emergency scenarios in an interactive virtual lab environment. By properly donning protective gear and following protocols for handling spilled waste, students train in safety protocols and spill response procedures. In the third stage, participants must recycle and reuse waste materials. By correctly sequencing recycling steps to maximize recovery rates, students develop concepts of resource circulation and sustainable development while generating maximum economic value for the laboratory. Upon completing each stage, the system awards points based on performance, grants exclusive titles, and displays a summary page indicating the amount of resources virtually conserved through this learning experience.

Figure 2.

Gamified Online Education Video Process.

The interface incorporates seven gamification elements categorized by Toda et al. for educational environments [73], as illustrated in Figure 3: Storytelling (presentation of game narratives through text, voice, or sensory elements, including animated scenes and audio cues) Progress (enabling students to visualize task completion via progress bars) Goals (quantifiable or spatial objectives, short- to long-term, presented as “map unlocks”) Restart (allowing retries or resets, featured in recycling sorting segments) Recognition (feedback praising specific player actions, including badges, medals, trophies) Points (units measuring student learning ability, quantifying performance through experience points (XP)), and Reputation (titles or ranks earned by students within the game).

Figure 3.

Gamification Elements Display.

3.3. Variable Measurement and Scale Design

The five variables measured in this study employed items grounded in prior research and grounded in sustainable laboratory safety education. Participants’ responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Internal consistency for each dimension was confirmed using Cronbach’s alpha.

Perceived Vulnerability. Perceived vulnerability is an individual’s perception of their risk of experiencing threats [59]. This study applied it to students’ assessment of potential safety risks in laboratories, such as chemical spills or improper waste disposal. Drawing from Chaohui Lin et al.’s [74] Laboratory Safety Risk Perception Scale, sample items included: “Hazardous substances could come into contact with my skin and cause injury.”

Perceived Severity. According to PMT [56], perceived severity refers to an individual’s assessment of the extent of harm a threat poses. This study examines students’ evaluation of the severity of consequences arising from improper laboratory waste disposal and non-compliance with green protocols. Drawing from Chaohui Lin et al.’s [74] Perceived Laboratory Safety Risk Scale, example items include: “Direct hand contact without protective gloves will immediately cause chemical burns or poisoning.”

Response efficacy. This variable measures individuals’ belief that the recommended behavior can effectively avert the threat [56]. In this study’s context, it translates to students’ belief that adopting green laboratory practices will genuinely reduce environmental risks. Response efficacy measurement references Hartmann et al.’s scale [75], with sample items including: “Strict adherence to waste classification and disposal protocols can significantly reduce the risk of environmental contamination and safety incidents in laboratories.”

Self-Efficacy. Self-efficacy, as defined by Bandura, refers to confidence in one’s ability to perform recommended behaviors successfully. This study operationalizes it as students’ confidence in their ability to successfully execute a series of green safety behaviors. The Chinese adaptation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) [76], developed by German psychologists Ralf Schwarzer and Matthias Jerusalem and revised by Zhang, J.X. & Schwarzer, R. [77], was used to measure participants’ self-efficacy. Sample items include: “I am confident I can properly handle unexpected situations in the laboratory.”

Green Behavior Intention. This variable measures an individual’s subjective willingness and likelihood to proactively adopt sustainable green behaviors in future activities, serving as the primary outcome of threat and coping assessment processes. Referencing the Environmental Behavior Scale by Lincoln R. L et al. [78], sample items include: “I will take proactive measures to reduce chemical and water usage, minimizing waste generation at the source.”

For the experimental scenario of waste management in sustainable laboratory safety education, the measurement items across the five scales were appropriately adapted to form a final set of 15 items. All items underwent iterative translation from English to Chinese with equivalent meaning and were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale. Detailed variables and corresponding measurement items are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Research Variables and Corresponding Measurement Items.

3.4. Experimental Tasks and Procedures

Participants were recruited through an online subject recruitment platform. Eligibility criteria included: (1) enrollment in a science or engineering program at a university laboratory; (2) average laboratory operation frequency of 1–2 times per week. These standards ensured participants engaged in laboratory activities, making them a target group for sustainable laboratory safety education. Experimental staff first briefly introduced the procedure to eligible participants. Participants signed informed consent forms and completed pre-test questionnaires to gather baseline information. They were then randomly assigned to one of four experimental groups, each receiving instructional interventions identical in content but differing in format and strategy: the paper-based lecture-based group, the paper-based gamified group, the digital lecture-based group, and the digital gamified group.

During the formal experiment, participants were instructed to assume the role of students and diligently study the sustainable laboratory safety education course. The learning task was scheduled between two identical green behavior intention tests, ensuring that any shifts in behavioral intention were attributable solely to the safety education and were precisely measured by the difference in scores between the pre- and post-tests. Finally, participants completed the post-test based on their experience and filled out the variable measurement scale. The entire experiment lasted 5–8 min.

4. Research Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The study recruited 165 students for the experiment. Among them, 4 participants were excluded during screening for failing to meet the experimental requirements, resulting in a final sample size of 161 participants. The sample comprised 89 females (55.3%) and 72 males (44.7%). The average age of participants was 20.94 (SD = 1.798), ranging from 19 to 25 years old. Educational attainment distribution was as follows: 70.2% (N = 113) held undergraduate degrees, and 29.8% (N = 48) held master’s degrees. Before testing the research hypotheses, reliability analysis was conducted on the 161 valid data sets. Results indicated that Cronbach’s α coefficients for all five variable factors exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.7: Perceived Severity (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.860), Perceived Vulnerability (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.935), Reactive efficacy (2 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.769), Self-efficacy (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.921), and Green behavior intention (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.864). The overall Cronbach’s α coefficient for the 15-item scale was 0.809, indicating good reliability. KMO = 0.785 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a significance level of p < 0.05, demonstrating adequate construct validity. All data analyses were performed using SPSS 27.

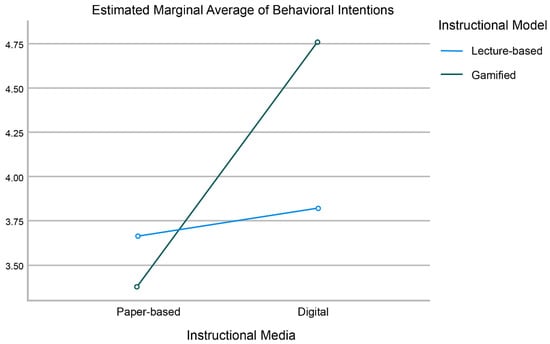

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four instructional media and model groups for laboratory-based access safety education. The gender and age ratios across these groups were comparable, with sizes of 40, 41, 41, and 39, respectively. Students exhibited the strongest green behavior intention in the gamified online teaching mode (M = 4.761, SD = 0.721) and the weakest in the gamified paper-based teaching mode (M = 3.382, SD = 0.509). No gender or educational level preferences for teaching media/modes were observed, nor were any interaction effects.

4.2. Effects of Instructional Media and Instructional Model on Green Behavior Intentions

Hypotheses H1 and H2 predicted the effects of instructional media and instructional models on students’ green behavior intentions in sustainable laboratory safety education. The study employed a two-way ANOVA to examine the influence of instructional media and modes. Results indicated that instructional media exerted a significant main effect on students’ green behavior intentions in laboratory safety education (F(1,157) = 63.116, p < 0.001). Furthermore, digital teaching media (M = 4.279, SD = 0.821) significantly induced higher green behavior intentions than paper-based media (M = 3.522, SD = 0.558), validating H1. The instructional model also exhibited a significant main effect on students’ green behavior intentions in laboratory safety education (F(1,157) = 11.521, p < 0.001). The game-based teaching model (M = 4.054, SD = 0.928) significantly increased green behavior intentions more than the lecture-based teaching model (M = 3.744, SD = 0.604), confirming H2.

Simultaneously, a significant interaction effect between instructional media and instructional model on green behavior intention (F(1,157) = 40.240, p < 0.001) was observed, as illustrated in Figure 4. A simple effects analysis further revealed that the instructional model had a significant main effect under the paper-based media condition (F(1,157) = 4.377, p = 0.038). Similarly, a significant simple main effect of the instructional model was also observed under the digital media condition (F(1,157) = 47.109, p < 0.001), with the online gamified teaching group demonstrating significantly higher green behavior intentions than the online lecture-based group (M Gamified = 4.761, M Lecture-based = 3.821). Conversely, the simple main effect of instructional media was not significant when the instructional model was lecture-based (F(1,157) = 1.290, p = 0.258). However, when gamification was integrated into the instructional model, a significant simple main effect of media was found (F(1,157) = 101.421, p = 0.038). In this case, the online gamified teaching mode elicited significantly higher green behavior intentions than the paper-based gamified mode (Mdigital = 4.761, MPaper-based = 3.382).

Figure 4.

Interaction Effect of Instructional Media and Instructional Model on Green Behavior Intention.

4.3. Mediating Role of Protective Motivation Decision Factors

This study analyzed the mediating role of protective motivation decision factors (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, response efficacy, self-efficacy) in the influence of sustainable laboratory safety education on students’ green behavior intentions. Results were evaluated using SPSS PROCESS Model 4 with a 95% confidence interval (CI), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean and Standard Deviation of Students’ Green Behavior Intentions Under Sustainable Safety Education.

Mediation analysis revealed that the total effect of instructional media on green behavior intention was significant (β = 0.7565, 95% CI = [0.5384, 0.9747]). However, after controlling for the four mediating variables (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, response efficacy, self-efficacy), its direct effect became non-significant (β = 0.2078, 95% CI = [−0.0602, 0.4758]). Perceived severity had a significant direct impact on green behavior intention (β = 0.4599, 95% CI = [0.1858, 0.4057]). The indirect effect of instructional media on green behavior intention via perceived severity was (β = 0.5410, 95% CI = [0.2862, 0.8123]), indicating that perceived severity fully mediated the influence of instructional media on green behavior intention, thus supporting Hypothesis H4b. The instructional media had no significant effect on perceived susceptibility, response efficacy, or self-efficacy. Perceived susceptibility (β = 0.0000, 95% CI = [−0.1026, 0.0175]), response efficacy (β = 0.0021, 95% CI = [−0.0199, 0.0288]), and self-efficacy (β = 0.0057, 95% CI = [−0.0881, 0.1069]) on the path from instructional media to green behavior were not significant. Therefore, hypotheses H4a, H4c, and H4d were not validated.

The overall effect of the instructional model on green behavior intention was significant (β = 0.3093, 95% CI = [0.0658, 0.5528]). However, after controlling for the four mediating variables (perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, response efficacy, self-efficacy), its direct effect became insignificant (β = 0.0828, 95% CI = [−0.1464, 0.3120]). Self-efficacy exerted a significant direct impact on the intention to engage in green behavior (β = 0.3437, 95% CI = [0.1567, 0.3836]), and the instructional model exerted a significant indirect effect on the intention for green behavior through self-efficacy (β = 0.3290, 95% CI = [0.1774, 0.4927]). This indicates that self-efficacy fully mediated the influence of instructional model on the green behavior intention, confirming hypothesis H5d. The instructional model did not significantly influence perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, or response efficacy. Perceived susceptibility (β = 0.0005, 95% CI = [−0.0248, 0.0228]), perceived severity (β = −0.1032, 95% CI = [−0.2373, 0.0373]), and response efficacy (β = 0.0003, 95% CI = [−0.0171, 0.0178]) on the path from instructional model to green behavior intention were not significant. Therefore, hypotheses H5a–H5c were not validated.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings

This study examined how instructional strategies, instructional media (paper-based/digital) and instructional models (lecture-based/gamified) affect students’ green behavior intentions during sustainable laboratory safety access education. It also investigated the mediating roles of four protective motivational decision factors: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, response efficacy and self-efficacy. Findings reveal that within sustainable laboratory safety education contexts, digital media and the gamified instructional model synergistically enhanced students’ green behavior intentions through dual pathways: the former by elevating perceived severity, and the latter by strengthening self-efficacy. These effects reflect, respectively, threat- and coping-assessment mechanisms within protective motivation theory [56,57].

When leveraging sustainable laboratory safety education to enhance green behavior intentions, students exhibited significantly stronger intentions when using digital media than when using paper-based media [79]. Moreover, when digital media information is presented in diverse formats such as text, images, and animations, it aligns better with human information processing systems, reducing cognitive load and deepening understanding of laboratory safety risks. Furthermore, in sustainable laboratory safety education scenarios, students exhibited more pronounced green behavior intentions under the game-based instructional model. It aligns with findings from research on gamified occupational safety training [50]. Drawing on key game elements for educational settings—such as storytelling, progress, goals, restarts, and recognition—the study develops two distinct instructional strategies: a digital media model and a gamified model. Results indicate that when students continuously engage in the closed-loop cycle of decision-verification-correction within game-based safety education, they transition from passive recipients to active participants. This shift synchronously increases both cognitive and emotional investment. In laboratory safety education contexts, this high-engagement state enables students to tightly associate green operational norms with the game-based learning process, thereby fostering stronger green behavior intentions post-education.

The study indicates a significant interaction between instructional media and instructional model in shaping students’ green behavior intentions within sustainable laboratory safety education. When both media and model are employed concurrently, the effectiveness of instructional strategy interventions is not determined by any single attribute but rather depends on the alignment between media and model. Specifically, when content is delivered via digital media, the gameified instruction enhances green behavior intentions more effectively than the lecture-based instruction. However, when switching to paper-based media, the gamified instruction actually weakens green behavior intentions compared to the lecture-based instruction, consistent with research by Sailer, M. et al. [80]. When instructional media and models are highly matched, a powerful synergistic effect emerges, significantly boosting green behavior intentions. In this study, students exhibited the highest green behavior intention when receiving sustainable laboratory safety education through an online gameified instructional model. Mayer’s Multimedia Learning Theory posits that learning is most effective when instructional information is presented through both visual and auditory channels, while maintaining close temporal and spatial correspondence [79]. The immersive, interactive, and instant feedback capabilities of digital media provide an ideal platform for gamified instruction. Students engage in experiential learning through exploration, trial-and-error, and task completion in virtual laboratories, thereby elevating their green behavior intentions. The success of gamification hinges on its integration with the learning context. Optimal outcomes occur when game elements seamlessly blend with learning content and activities [80]. However, static, linear paper-based media severely limit this integration, leading to game elements becoming disconnected from learning objectives. Attempts to gamify outcomes on paper often result in cumbersome rules, clunky interactions and unengaging tasks. The gap between expectations of a game-like experience and the dull reality not only fails to spark interest but may also increase cognitive load, severely inhibiting the emergence of green behavior intentions. Consequently, sustainability lab safety education delivered through a paper-based and gamified instructional model elicits the lowest levels of green behavior intentions among students.

In sustainable laboratory safety education, instructional media and instructional models indirectly influence student learning outcomes through protective motivation decision factors. Instructional media enhance students’ green behavior intentions by influencing their perceived severity in safety education. The multi-channel and high vividness of digital media naturally amplify fear appeals [81]. In this study, dynamic accident footage and real-time data in online instruction vividly depicted the severity and consequences of laboratory waste-disposal crises, thereby amplifying students’ perceived severity and enhancing green behavior intentions. It aligns with the Extended Parallel Process Model [82], which posits that high-intensity threat information is crucial for triggering fear and subsequent behavioral change. O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole also noted that, while requiring careful use, visually impactful environmental disaster imagery significantly enhances public awareness of issue severity [83]. The instructional model influences students’ green behavior intentions by boosting self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is regarded as the most proximate determinant of behavioral change. Observing others’ experiences or receiving positive feedback from external sources is a vital source of self-efficacy [84]. This study gamified the project workflow, involving virtual sorting, processing, and recycling of waste, enabling students to gain direct success experiences that embody “I can do it.” The establishment of this intrinsic confidence, coupled with recognition of the problem’s severity or the effectiveness of its solutions, became the fundamental driving force behind the enhancement of their green behavior intentions.

Notably, perceived susceptibility and response efficacy did not play significant roles in either pathway, suggesting specific complexities in the mechanisms underlying motivation formation in safety education contexts. The lack of significance for perceived susceptibility may stem from the inherent abstractness and delayed nature of environmental issues. Research by Spence, A., confirms that the public generally perceives climate change as psychologically distant, which directly weakens perceived susceptibility, even when individuals acknowledge the overall severity of the problem [85]. Students may recognize the global seriousness and consequences of improper laboratory waste disposal through instructional media, such as environmental pollution, yet not perceive themselves as immediately and directly threatened. The lack of significance in response efficacy may reflect a ceiling effect within the study sample, where students already widely endorsed the effectiveness of green behaviors. Hornik, J. research indicates that knowledge about recycling is typically widespread, yet it alone is insufficient to predict recycling behavior; other factors, such as convenience, are more critical [86]. Students reached a social consensus on the efficacy of green behaviors before the laboratory safety education intervention, leading to response efficacy failing to induce significant incremental changes in predicting students’ green behavior intentions. If people cannot clearly see the benefits of their actions, their motivation to act is significantly diminished [87]. In this study, although the teaching model enhanced self-efficacy, the mediating pathway of response efficacy was weak when the direct benefits of action were not sufficiently clear and immediate.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The theoretical implications of this study include three points: (1) It enriches the research on teaching strategies in sustainable laboratory safety education, revealing the relationship between teaching media and teaching modes and students’ green behavior intentions, along with their influencing mechanisms. Traditional protection motivation theory typically applies cognitive appraisal processes to health contexts. This study extends the applicability of protection motivation theory to laboratory safety and sustainable green behavior domains, particularly demonstrating how gamified elements such as feedback and narratives function as external stimuli to specifically enhance students’ coping appraisals, thereby refining and expanding the theoretical pathway. (2) This study focuses on specific strategies for sustainable laboratory safety instruction, revealing the influence mechanisms of teaching media and instructional modes on students’ green behavior intentions. It provides theoretical foundations for designing curricula on laboratory safety access education. (3) It uncovers the interactive relationship between teaching media and instructional modes. A simple digital lecture offers limited advantages over paper-based teaching, indicating that multimedia’s cognitive benefits require active learner engagement in the assessment process—such as through gamification—to achieve high interactivity and fully realize their potential. This enriches the boundary conditions of multimedia learning theory within laboratory safety education.

The practical implications of this study comprise four points: (1) Curriculum designers should spearhead the development of novel safety education modules centered on digital gamification to stimulate students’ willingness to adopt green behaviors. Specifically, rather than merely listing laboratory rules, they should leverage the narrative capabilities of digital media to construct virtual risk scenarios. Visualizing negative consequences heightens learners’ perception of severity. Simultaneously, setting clear objectives, providing immediate feedback, and implementing achievement systems significantly boost students’ self-efficacy, transforming external safety requirements into enduring green behavioral intentions. (2) Research confirms that digitizing paper content yields limited effects, whereas adding interactive modules genuinely alters students’ green behavioral intentions. University safety administrators can phase out standalone paper lab safety manuals and instead require students to complete a brief, interactive, digital, and gamified training platform as a prerequisite for lab access. This will substantially enhance safety and environmental compliance. (3) For educational policymakers, it is recommended to encourage and fund the development of a national, evidence-based, standardized digital repository of gamified safety education resources. These modules should explicitly target enhancing risk perception and operational confidence, and be promoted as open-source to ensure foundational teaching quality, avoid redundant investments, and facilitate cross-institutional experience sharing—systematically elevating the overall standard of sustainable laboratory education. (4) For educational technology developers, this study reveals that efforts should extend beyond providing generic gamification elements. Instead, the dual-path mechanism of protection motivation theory should be deeply integrated into the development and design logic of educational technology. An ideal technology platform should guide educators in easily creating customized teaching experiences that target either risk-severity cognition (e.g., through immersive story-driven narratives) or safety self-efficacy building (e.g., through interactive skill training), thereby enabling precise interventions.

6. Conclusions

This study focuses on the application of gamified online teaching models in sustainable education on laboratory safety access. However, the research has several limitations.

- (1)

- The experimental focus was on sustainable laboratory safety education; the external validity of the findings requires validation in other educational contexts.

- (2)

- While this study examines the direct impact of gamified instruction on students’ green behavior intentions, the process may be influenced by individual differences among students. Personal factors such as prior gaming experience, learning preferences, and digital literacy may serve as moderating variables that affect students’ behavioral intentions. By ensuring random assignment of participants to groups, this study maintains an approximate normal distribution of individual characteristics within groups, thereby minimizing such influences.

- (3)

- Two primary limitations exist in the experimental design: First, no non-intervention control group was established. The current 2 × 2 factorial design aims to compare the relative effectiveness of four active teaching strategies, a common approach in comparative studies in educational technology [88]. However, future research should incorporate a control group to more reliably assess the net effect of the teaching strategies themselves after controlling for factors such as pretest interference. Another limitation is that the intervention lasted relatively briefly (5–8 min). While this aligns with the focused, immediate model of microlearning [89], it may be insufficient to trigger deep learning, and observed effects could partially stem from novelty effects [90]. Therefore, future studies should adopt longitudinal designs, such as tracking students’ intentions and behaviors throughout an entire semester in actual experimental courses, to examine the persistence of effects.

Given the aforementioned research limitations, future studies could conduct cross-sectional comparative research across diverse educational settings, focusing on universally applicable educational environments. Additionally, efforts should be made to extend the research paradigm to more complex experimental scenarios, thereby further clarifying the application boundaries of online game-based instructional strategies in professional domains and user interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H. and Y.C.; methodology, W.H. and X.S.; software, W.H.; validation, W.H., Y.C., and X.S.; formal analysis, W.H.; investigation, Y.C.; resources, W.H. and X.S.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.H. and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, X.S.; visualization, Y.C.; supervision, X.S.; project administration, X.S.; funding acquisition, X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Youth Project of Humanities and Social Sciences Fund, 2022: “Promote the multi-modal interaction and service system design research of social intelligence of elderly care robots” (No. 22YJCZH156).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the College of Furnishings and Industrial Design, Nanjing Forestry University, with protocol code No. 2025039 and date of approval 5 February 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

All participating students were fully informed of the study’s purpose, content, and methodology, and provided their informed consent by signing consent forms, explicitly indicating their voluntary participation and agreement to the use of their data for this study.

Data Availability Statement

All collected data were anonymized to protect the privacy of participants. The data presented in this study are available in this article. All data was stored on secure servers with appropriate security measures in place to prevent data leakage or misuse.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt thanks to the students who participated in the research experiments. We are equally grateful to the experts who generously shared their insights and expertise in the online survey. The authors especially thank Wenkui Jin from the College of Furnishings and Industrial Design at Nanjing Forestry University for his assistance with the experiments in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PMT | Protection Motivation Theory |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| CLT | Cognitive Load Theory |

| ICL | Intrinsic Cognitive Load |

| ECL | Extraneous Cognitive Load |

| GCL | Germane Cognitive Load |

References

- Li, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, S.; Hu, Y. Status and Characteristics of Energy Consumption of Campus Scientific Research Buildings. Build. Energy Effic. 2015, 7, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, S.; Fetter, É.; Staude, C.; Vierke, L.; Biegel-Engler, A. Short-Chain Perfluoroalkyl Acids: Environmental Concerns and a Regulatory Strategy under REACH. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2018, 30, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Liu, Y.; Qi, M.; Roy, N.; Shu, C.-M.; Khan, F.; Zhao, D. Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions of University Laboratory Safety in China. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2022, 74, 104671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, W.G. Fighting lab fires. Chem. Eng. News 2005, 83, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. Sustainability Education Through Digital Platforms: Evaluating Digital Tools for Eco-Conscious Behavior Promotion. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. 2025, 23, 1425–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhute, V.J.; Inguva, P.; Shah, U.; Brechtelsbauer, C. Transforming Traditional Teaching Laboratories for Effective Remote Delivery—A Review. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 35, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraimi, K.M.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P. Understanding the MOOCs Continuance: The Role of Openness and Reputation. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. The Evolution of MOOCs and Their Influence on Higher Education. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2013, 2, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Kumar, L. Online Education- Benefit or Misuse:A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Res. Trends Innov. 2023, 8, 621–627. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, G.A.; Aldous, S.M. Digital Innovation in Green Learning: Ensuring Safety While Fostering Environmental Stewardship. In Legal Frameworks and Educational Strategies for Sustainable Development; Alqodsi, E., Abdallah, A., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 307–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Parks, S.; Shang, J. To learn scientifically, effectively, and enjoyably: A review of educational games. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokac, U.; Novak, E.; Thompson, C.G. Effects of Game-based Learning on Students’ Mathematics Achievement: A Meta-analysis. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2019, 35, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gampell, A.V.; Gaillard, J.C.; Parsons, M.; Le Dé, L.; Hinchliffe, G. Participatory Minecraft Mapping: Fostering Students Participation in Disaster Awareness. Entertain. Comput. 2024, 48, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, S.; Moafian, F. The Victory of a Non-Digital Game over a Digital One in Vocabulary Learning. Comput. Educ. Open 2023, 4, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Peng, Z. Digital Game-based Learning in a Shanghai Primary-school Mathematics Class: A Case Study. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2020, 36, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, E.J.; Ling, M.; North, M.; Klas, A.; Mullan, B.A.; Novoradovskaya, L. Protection Motivation Theory and Pro-environmental Behaviour: A Systematic Mapping Review. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How to Green Your Lab. Available online: https://mygreenlab.org/how-to-green-your-lab/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Withers, J.H.; Freeman, S.A.; Kim, E. Learning and Retention of Chemical Safety Training Information: A Comparison of Classroom versus Computer-Based Formats on a College Campus. J. Chem. Health Saf. 2012, 19, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.A.; Ronan, K.R.; Johnston, D.M.; Peace, R. Evaluations of Disaster Education Programs for Children: A Methodological Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 9, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Becerra, E.; Barrero, L.H.; Ellegast, R.; Kluge, A. The Effectiveness of Virtual Safety Training in Work at Heights: A Literature Review. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 94, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekdag, B. Video-Based Instruction on Safety Rules in the Chemistry Laboratory: Its Effect on Student Achievement. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2020, 21, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camel, V.; Maillard, M.-N.; Descharles, N.; Le Roux, E.; Cladière, M.; Billault, I. Open Digital Educational Resources for Self-Training Chemistry Lab Safety Rules. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Feng, M.; Lowe, H.; Kesselman, J.; Harrison, L.; Dempski, R.E. Increasing Enthusiasm and Enhancing Learning for Biochemistry-Laboratory Safety with an Augmented-Reality Program. J. Chem. Educ. 2018, 95, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Savari, M.; Khaleghi, B. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting the Behavioral Intentions of Iranian Local Communities toward Forest Conservation. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1121396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan Hoang, T.T.; Kato, T. Measuring the Effect of Environmental Education for Sustainable Development at Elementary Schools: A Case Study in Da Nang City, Vietnam. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2016, 26, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.T.; Sharmin, F.; Badulescu, A.; Stiubea, E.; Xue, K. Travelers’ Responsible Environmental Behavior towards Sustainable Coastal Tourism: An Empirical Investigation on Social Media User-Generated Content. Sustainability 2020, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagiliūtė, R.; Liobikienė, G.; Minelgaitė, A. Sustainability at Universities: Students’ Perceptions from Green and Non-Green Universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, E.; Sousa, S.; Viseu, C.; Leite, J. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand the Students’ pro-Environmental Behavior: A Case-Study in a Portuguese HEI. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 1070–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ma, P. Knowledge Flow Research in MOOC Platform Based on Super Network. Libr. Inf. 2015, 6, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbach, K.; Hunter, D. For the Win: How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business; Wharton Digital Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto, J.; Hamari, J. The Rise of Motivational Information Systems: A Review of Gamification Research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J. Why do people use gamification services? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 29–30 September 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: Tampere, Finland, 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendeleg, G.; Murwa, V.; Yun, H.-K.; Kim, Y.S. The Role of Gamification in Education–a Literature Review. Contemp. Eng. Sci. 2014, 7, 1609–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, X. Using Game-Based Learning to Support Learning Science: A Study with Middle School Students. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2021, 30, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-J.; Hsu, Y.-S.; Lai, C.-H.; Chen, F.-H.; Yang, M.-H. Applying Game-Based Experiential Learning to Comprehensive Sustainable Development-Based Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, A.; Simon, H.A. Human Problem Solving; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, P.; Vargas, C.; Ackerman, R.; Salmerón, L. Don’t Throw Away Your Printed Books: A Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Reading Media on Reading Comprehension. Educ. Res. Rev. 2018, 25, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, N.; Van Joolingen, W.R.; Van Der Veen, J.T. The Learning Effects of Computer Simulations in Science Education. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K. Constructivist Instructional Models, Instructional Methods, and Instructional Design. J. Beiiing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 1997, 5, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, B.; Calhoun, E. Models of Teaching, 10th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, R.; MacDonald, T.; DiGiuseppe, M. A comparison of lecture-based, active, and flipped classroom teaching approaches in higher education. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2019, 31, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barblett, L.; Knaus, M. Learning Through Play in Early Childhood Education. In Encyclopedia of Teacher Education; Peters, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The Power of Feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Horng, J.-S.; Chou, S.-F.; Yu, T.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Ng, Y.-L.; Lin, J.-Y. How Big Data Applications and Digital Learning Change Students’ Sustainable Behaviours—the Moderating Roles of Hard and Soft Skills. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 32, 6751–6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittaro, L.; Sioni, R. Serious games for emergency preparedness: Evaluation of an interactive vs. a non-interactive simulation of a terror attack. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shang, J. A Theoretical Study on Game-based Learning from the Perspective of Learning Experiences. E-Educ. Res. 2018, 6, 11–20, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colan, C.C.; Peralta, D.B.; Flores, R.V.; Morales Gomero, J.C. Gamification in Occupational Safety Training: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Houston, TX, USA, 12–15 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Galeote, D.; Rajanen, M.; Rajanen, D.; Legaki, N.-Z.; Langley, D.J.; Hamari, J. Gamification for Climate Change Engagement: A User-Centered Design Agenda. In Proceedings of the 26th International Academic Mindtrek Conference, Tampere, Finland, 3–6 October 2023; pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Element Interactivity and Intrinsic, Extraneous, and Germane Cognitive Load. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 22, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 55, pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.L.; Ley, K. A Learning Strategy to Compensate for Cognitive Overload in Online Learning: Learner Use of Printed Online Materials. J. Interact. Online Learn. 2006, 5, 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khresheh, M.H. The Cognitive and Motivational Benefits of Gamification in English Language Learning: A Systematic Review. Open Psychol. J. 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change1. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. Cognitive and Physiological Processes in Fear Appeals and Attitude Change: A Revised Theory of Protection Motivation. In Social Psychophysiol: A Sourcebook; Cacioppo, J.T., Petty, R.E., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, S.; Sheeran, P.; Orbell, S. Prediction and Intervention in Health-Related Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of Protection Motivation Theory. J Appl. Soc. Pyschol 2000, 30, 106–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, D.L.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. A Meta-Analysis of Research on Protection Motivation Theory. J. Appl. Soc. Pyschol 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippetoe, P.A.; Rogers, R.W. Effects of Components of Protection-Motivation Theory on Adaptive and Maladaptive Coping with a Health Threat. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnikoff, R.C.; Higginbotham, N. Protection Motivation Theory and Exercise Behaviour Change for the Prevention of Heart Disease in a High-Risk, Australian Representative Community Sample of Adults. Psychol. Health Med. 2002, 7, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. Protection Motivation Theory and preventive health: Beyond the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Res. 1986, 1, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W.; Prentice-Dunn, S. Protection Motivation Theory. In Handbook of Health Behavior Research 1: Personal and Social Determinants; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele, S.K.; Maddux, J.E. Relative Contributions of Protection Motivation Theory Components in Predicting Exercise Intentions and Behavior. Health Psychol. 1987, 6, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.E.; Thompson, S.C. Stalking the elusive “vividness” effect. Psychol. Rev. 1982, 89, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghani, A.; Bijani, M.; Valizadeh, N. What Makes Students of Green Universities Act Green: Application of Protection Motivation Theory. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 838–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmaimool, P. Application of Protection Motivation Theory to Investigate Sustainable Waste Management Behaviors. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection Motivation and Self-Efficacy: A Revised Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F. Extending the Protection Motivation Theory Model to Predict Public Safe Food Choice Behavioural Intentions in Taiwan. Food Control 2016, 68, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.L.; Sørensen, E.B. Recreation, Cultivation and Environmental Concerns: Exploring the Materiality and Leisure Experience of Contemporary Allotment Gardening. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.N.; Koster, A.; Russell, C.G. Predicting Intentions to Consume Functional Foods and Supplements to Offset Memory Loss Using an Adaptation of Protection Motivation Theory. Appetite 2004, 43, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N.; Armstrong, M.B. Enhancing Instructional Outcomes with Gamification: An Empirical Test of the Technology-Enhanced Training Effectiveness Model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, A.M.; Oliveira, W.; Klock, A.C.; Palomino, P.T.; Pimenta, M.; Gasparini, I.; Shi, L.; Bittencourt, I.; Isotani, S. A Taxonomy of Game Elements for Gamification in Educational Contexts: Proposal and Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), Maceio, Brazil, 15–18 July 2019; pp. 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zheng, K.; Man, S.S. Risk Perception Scale for Laboratory Safety: Development and Validation. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2025, 105, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza, V.; D’Souza, C.; Barrutia, J.M.; Echebarria, C. Environmental Threat Appeals in Green Advertising: The Role of Fear Arousal and Coping Efficacy. Int. J. Advert. 2014, 33, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. General Self-Efficacy Scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Schwarzer, R. Measuring Optimistic Self-Beliefs: A Chinese Adaptation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Psychol. Int. J. Psychol. Orient 1995, 38, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, L.R.; Stedman, R.C.; Cooper, C.B.; Decker, D.J. Understanding the Multi-Dimensional Structure of pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Multimedia Learning, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Homner, L. The Gamification of Learning: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. College Students’ Intention to Adopt Protective Health Behaviors during Pandemic. J. Res. 2022, 2, 17–33, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K. Putting the Fear Back into Fear Appeals: The Extended Parallel Process Model. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. “Fear Won’t Do It”: Promoting Positive Engagement With Climate Change Through Visual and Iconic Representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W H Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G. The Psychological Distance of Climate Change Is Overestimated. One Earth 2023, 6, 362–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, J.; Cherian, J.; Madansky, M.; Narayana, C. Determinants of Recycling Behavior: A Synthesis of Research Results. J. Socio-Econ. 1995, 24, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E.; Johnson, C.I. Adding Instructional Features That Promote Learning in a Game-Like Environment. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2010, 42, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monib, W.K.; Qazi, A.; Apong, R.A. Microlearning beyond Boundaries: A Systematic Review and a Novel Framework for Improving Learning Outcomes. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, C.; Filippou, J.; Cheong, F. Towards the Gamification of Learning: Investigating Student Perceptions of Game Elements. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2014, 25, 233–244. [Google Scholar]