Abstract

Pharmaceuticals such as paracetamol and diclofenac (DCF) are among the most extensively consumed drugs worldwide and are continuously released into municipal and hospital wastewater due to incomplete human metabolism. Their persistent presence in aquatic environments, typically ranging from ng/L to µg/L, raises concerns due to endocrine disruption, chronic toxicity, and the promotion of antimicrobial resistance. Conventional wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) remove 70–90% of ACT but less than 30% of DCF, primarily because these systems were not designed to target low-concentration, recalcitrant micropollutants. As a result, pharmaceuticals frequently pass into treated effluents, highlighting the need for advanced, sustainable, and passive treatment solutions. Permeable reactive barriers (PRBs) have emerged as a promising technology for the interception and removal of pharmaceuticals from both wastewater treatment plant effluents and groundwater. This review provides a comprehensive assessment of ACT and DCF occurrence, environmental behavior, and ecotoxicological risks, followed by a detailed evaluation of PRB performance using advanced reactive media such as geopolymers, activated carbon, carbon nanotubes, and hybrid composites. Reported removal efficiencies exceed 90% for ACT and 70–95% for DCF, depending on media composition and operating conditions. The primary removal mechanisms include adsorption, ion exchange, π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and redox transformation. The novelty of this review lies in systematically synthesizing recent laboratory- and pilot-scale findings on PRBs for pharmaceutical removal, identifying critical knowledge gaps—including long-term field validation, media regeneration, and performance under realistic wastewater matrices—and outlining future research directions for scaling PRBs toward full-scale implementation. The study demonstrates that PRBs represent a viable and sustainable tertiary treatment option for reducing pharmaceutical loads in aquatic environments.

1. Introduction

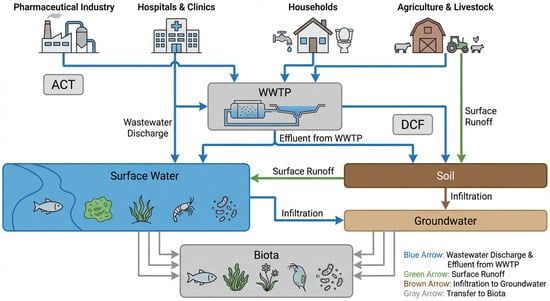

Over the past two decades, the occurrence of contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in aquatic environments has become a pressing environmental and public health issue. CECs encompass a diverse range of compounds such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products (PCPs), pesticides, veterinary drugs, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals, many of which are continuously released into wastewater streams through domestic, hospital, agricultural, and industrial activities [1,2,3,4]. Their persistence and incomplete removal in conventional wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) have led to widespread detection in effluents, surface waters, groundwater, and even drinking water sources [5,6,7,8]. Concentrations of widely used pharmaceuticals such as ACT and DCF have been reported from ng/L to several hundred µg/L, particularly near pharmaceutical manufacturing sites and hospital effluents [9,10,11,12,13]. Even at trace levels, these compounds may pose ecotoxicological risks, including oxidative stress, endocrine disruption, reproductive toxicity, and promotion of antimicrobial resistance [14,15,16,17,18,19].

Although WWTPs are highly effective at removing suspended solids, nutrients, and biodegradable organic matter, they were not engineered to eliminate low-concentration and chemically stable micropollutants such as pharmaceuticals. Their conventional biological processes rely on microbial degradation, which is efficient for readily biodegradable compounds but ineffective for structurally complex or hydrophobic molecules [20,21,22,23,24,25]. For example, ACT is removed at 70–90% due to its high water solubility, simple aromatic structure, and rapid microbial breakdown, whereas DCF persists with removal efficiencies typically below 30% because of its halogenated aromatic rings, high hydrophobicity (logKow ≈ 4.5), and limited biodegradability under aerobic conditions. These properties prevent its sorption onto activated sludge flocs and inhibit enzymatic degradation, leading to its continuous release into treated effluents even at sub-µg/L concentrations.

In addition, tertiary processes such as chlorination may further complicate removal; while disinfection eliminates pathogens, it does not mineralize pharmaceuticals and can even transform ACT into reactive quinone derivatives, including 1,4-benzoquinone and N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), which exhibit hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic effects. DCF has been placed on the European Union “Watch List” due to its persistence, widespread detection in surface waters, and poor removal in conventional WWTPs, underscoring the need for advanced treatment solutions specifically targeting recalcitrant micropollutants [26,27,28,29].

To tackle these difficulties, focus has transitioned to tertiary and advanced treatment technologies that can refine wastewater treatment plant effluents and target trace micropollutants. Common tertiary processes include advanced oxidation (ozonation, UV/H2O2, Fenton), membrane filtration (nanofiltration, reverse osmosis), and adsorption-based techniques (activated carbon, biochar, zeolites) [15,30,31,32,33]. Although these technologies are efficacious, they frequently entail high energy consumption, substantial costs, or produce potentially deleterious by-products [34,35]. Consequently, there is an increasing demand for passive, economical, and sustainable treatment methodologies.

Permeable reactive barriers (PRBs), initially designed for in situ groundwater remediation, have surfaced as a viable alternative for wastewater treatment applications [36,37]. Initially, PRBs comprised underground trenches or modules loaded with reactive material, allowing contaminated water to pass through them under natural hydraulic gradients. Contaminants are eliminated within the barrier through adsorption, precipitation, ion exchange, redox processes, or biodegradation. The benefits of PRBs encompass minimal energy demands, passive functionality, flexibility to local hydrogeological conditions, and sustained treatment capability [38]. Originally evaluated for the remediation of toxic metals, chlorinated solvents, and nitrates, PRBs are now being increasingly studied for the elimination of organic micropollutants, such as medicines [39]. Laboratory and pilot-scale investigations have shown removal efficiencies of 90% for ACT and 70–95% for DCF utilizing developed permeable reactive barrier medium. Most of the reported systems for ACT and DCF removal using PRB-type configurations are still limited to laboratory and pilot-scale column experiments. In these studies, influent concentrations typically range from tens or hundreds of ng·L−1, which mimic environmental levels found in municipal effluents and receiving waters, up to 0.1–1 mg·L−1 in scenarios representing hospital or pharmaceutical wastewaters. Under optimized conditions, carbon-based media such as granular activated carbon and biochar usually achieve more than 90% removal of ACT and 70–95% removal of DCF, resulting in residual concentrations in the low µg·L−1 or even ng·L−1 range. To date, only a few PRB or PRB-like installations have been tested under field conditions for pharmaceutical-contaminated plumes, and none has been designed exclusively for ACT and DCF, which underlines the need for further pilot and full-scale demonstrations [4,40].

Recent advancements have concentrated on creating innovative reactive materials to improve the efficiency, selectivity, and durability of PRBs. Geopolymers, activated carbon, and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have garnered significant attention. Geopolymers, derived from industrial by-products like fly ash or slag, are aluminosilicate materials noted for their great mechanical strength, porosity, and chemical stability [41]. They have demonstrated efficacy in adsorbing both cationic and anionic medicines, such as tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications [4,40,42]. Activated carbon is one of the most extensively utilized sorbents owing to its substantial surface area and recognized regeneration techniques [43]. Recent advancements in surface functionalization and integration with synthetic nanoparticles and biochar have significantly improved its efficacy across diverse pH levels and ionic strengths [20,44,45]. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), characterized by their distinctive π–π interactions, electrostatic attributes, and hydrophobic surfaces, exhibit substantial sorption capabilities for medicines and endocrine disruptors [46,47]. Challenges related to cost and potential ecotoxicity are being addressed by additional modification through surface oxidation and composite formation [48].

Notwithstanding these advancements, knowledge deficiencies persist. Most studies remain limited to laboratory-scale experiments, while long-term field applications assessing hydraulic conductivity, fouling dynamics, breakthrough behavior, and competitive sorption under realistic wastewater conditions are still scarce [49,50,51,52]. Standardized testing protocols for evaluating PRB performance against pharmaceuticals and other CECs are under development, which continues to delay regulatory approval.

Nevertheless, available evidence demonstrates that PRBs can achieve high removal efficiencies when optimized reactive media are used. Recent studies report >90% removal of ACT and 70–95% removal of DCF in PRBs filled with activated carbon, carbon nanotubes, or geopolymer–carbon hybrids under continuous-flow conditions. The primary mechanisms responsible for contaminant removal include micropore adsorption, ion exchange, π–π stacking between aromatic drug molecules and carbon surfaces, hydrogen bonding, and redox interactions occurring at the reactive media–water interface.

However, the combined effects of complex wastewater matrices—such as natural organic matter, competing ions, surfactants, and pharmaceutical transformation products—on long-term PRB performance remain insufficiently characterized [11,53]. These gaps highlight the need for field-scale trials and comprehensive mechanistic studies before full-scale implementation can be realized.

Several reviews have previously summarized the application of permeable reactive barriers and related in situ sorptive or reactive barriers for the removal of organic micropollutants and pharmaceuticals from contaminated groundwater and wastewater [36,37,38,39]. These studies have mainly focused on mixed contaminant plumes or broad classes of contaminants of emerging concern, outlining general PRB design principles, commonly used reactive media, and selected field applications, but they do not provide a dedicated analysis of ACT and DCF. To the best of our knowledge, no review has specifically examined the removal of ACT and DCF using PRBs or PRB-like systems, nor compared the performance of different reactive materials for these two representative pharmaceuticals. This gap motivates a focused assessment of ACT- and DCF-targeted PRBs in terms of removal mechanisms, media selection, and prospects for practical implementation.

The present review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the current state of PRB research for the removal of CECs, with particular emphasis on ACT and DCF as representative pharmaceuticals. We discuss the occurrence and environmental risks of these compounds, critically examine the properties and performance of advanced reactive media (geopolymers, activated carbon, CNTs), and identify knowledge gaps that must be addressed for successful field implementation. Finally, perspectives on hybrid PRB systems and regulatory frameworks are offered to guide the integration of PRBs into sustainable wastewater treatment strategies. The novelty of this review lies in systematically analyzing the potential of PRBs for the removal of ACT and DCF as representative pharmaceuticals, with a particular focus on the performance of advanced sorbent materials and hybrid composites. By synthesizing current findings, this paper highlights the opportunities and limitations of PRBs in wastewater treatment and outlines future directions for scaling up this technology toward sustainable application.

2. Wastewater Treatment Plants and Limitations in Removing CECs

2.1. Primary and Secondary Treatment

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) constitute essential infrastructures for protecting public health and aquatic ecosystems. Their conventional design relies on a sequence of primary, secondary, and, in some cases, tertiary processes intended to eliminate suspended solids, nutrients, and biodegradable organic matter [11,17,35,53]. Primary treatment employs mechanical separation (screening, grit removal, sedimentation), while secondary treatment applies biological processes such as activated sludge and biofilm reactors. Together, these stages are highly effective for bulk pollutants, yet they are not optimized for micropollutants such as pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and endocrine disruptors, collectively referred to as CECs [53].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that pharmaceuticals often persist through biological treatment. ACT owing to its high biodegradability, is removed at 70–90% efficiency, whereas DCF, with its halogenated aromatic structure and poor microbial degradability, typically exhibits removal rates below 30% [9,54,55]. This discrepancy underscores a major limitation of conventional WWTPs: their inability to consistently attenuate CECs to environmentally safe levels [50,56,57].

2.2. Tertiary Treatment Approaches

To address these shortcomings, WWTPs increasingly incorporate tertiary or advanced treatment technologies designed specifically for micropollutant removal. Although these systems can remove >90% of suspended solids, organic matter, nutrients, and pathogens, they do not eliminate all pharmaceuticals because most tertiary treatments target bulk pollutants rather than trace, persistent organic compounds present at ng/L–µg/L levels [58,59]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs)—including ozonation, UV/H2O2, and Fenton reactions—produce hydroxyl radicals capable of degrading many pharmaceuticals. However, degradation is often incomplete, leading to the formation of toxic transformation products; for instance, ACT can be converted into 1,4-benzoquinone and N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), known hepatotoxicants and nephrotoxicants. DCF, due to its halogenated aromatic structure and high hydrophobicity, remains comparatively resistant to oxidative degradation, with reported removal efficiencies varying between 40 and 80% depending on pH, oxidant dose, and residence time [60,61].

Membrane-based processes such as nanofiltration (NF) and reverse osmosis (RO) can remove pharmaceuticals via size exclusion and electrostatic repulsion, often achieving >95% rejection of ACT and DCF. However, their large-scale application is constrained by high energy demand, membrane fouling, and challenges related to concentrate disposal [62]. Adsorption remains one of the most established and scalable tertiary treatments. Activated carbon—both granular (GAC) and powdered (PAC)—regularly achieves >90% removal of ACT and 70–95% of DCF under optimized conditions. Its effectiveness stems from its large specific surface area (typically 800–1500 m2/g), well-developed microporosity (<2 nm), and abundant surface functional groups enabling π–π interactions, hydrophobic adsorption, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic attraction with pharmaceutical molecules [63,64,65,66,67]. Removal efficiency is strongly dependent on pore size distribution: ACT, being smaller and more polar, readily fits into micropores, while DCF shows enhanced adsorption in materials with both micropores and mesopores (2–50 nm).

Biochar-based adsorbents are gaining attention as low-cost alternatives, though their performance varies significantly due to inconsistent pore structure and surface chemistry. Nature-based systems such as constructed wetlands and soil aquifer treatment provide additional polishing but show inconsistent removal of pharmaceuticals, which remain sensitive to temperature, hydraulic loading, and microbial community composition. Overall, although tertiary treatments demonstrate considerable advancements, pharmaceutical pollutants require more specialized and intensive treatment approaches due to their stability, low concentrations, and resistance to biodegradation, which limits their full removal in conventional WWTP configurations [67,68,69,70].

2.3. The Potential Use of PRBs in Tertiary Treatment

Permeable reactive barriers (PRBs), initially developed for in situ groundwater remediation, are increasingly considered as an innovative tertiary treatment strategy for WWTP effluents [71,72,73,74]. Originally, PRBs consist of subsurface trenches or modular units filled with reactive media, through which contaminated water passes under natural hydraulic gradients. Removal of micropollutants occurs via adsorption, ion exchange, precipitation, redox reactions, or biodegradation, depending on the selected medium [3,12,75,76,77].

Recent laboratory- and pilot-scale studies demonstrate that PRBs equipped with advanced reactive media—including geopolymers [42], activated carbon [44], and carbon nanotubes [43]—can achieve high pharmaceutical removal efficiencies, typically >90% for ACT and 70–95% for DCF under optimized flow and loading conditions. Their effectiveness is attributed to multiple removal mechanisms operating simultaneously. Activated carbon provides extensive microporosity and aromatic surfaces that promote π–π interactions, hydrophobic adsorption, and pore-filling of both ACT and DCF. Carbon nanotubes enhance adsorption through graphitic π-electron systems, enabling strong π–π stacking and rapid mass transfer, while geopolymers contribute ion-exchange sites, surface hydroxyl groups, and electrostatic interactions that facilitate the binding of charged pharmaceutical species.

In addition to their high removal capacity, PRBs offer significant practical advantages: they operate passively without energy input, require minimal maintenance, and can be tailored to site-specific hydrogeological conditions. These features make PRBs a sustainable and flexible option to complement or replace conventional tertiary treatment processes for mitigating CEC release into aquatic environments [38,78,79].

3. Contaminants of Emerging Concern

3.1. Sources of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) in Wastewater and Implications for PRB Implementation

CECs originate from a diverse array of human activities and enter municipal and industrial wastewater through various pathways. These contaminants include pharmaceuticals, personal care products (PCPs), pesticides, industrial additives, microplastics, and other bioactive substances [51,78,79,80]. The persistent introduction of these pollutants into wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) presents an ongoing challenge, as conventional treatment processes only partially remove many CECs [46,62,81,82]. Identifying the primary sources of CECs is crucial for developing targeted removal strategies and selecting appropriate reactive media for permeable reactive barriers (PRBs) [15,20,83].

The primary sources of CECs and their typical concentration ranges are summarized in Table 1. Each source contributes distinct contaminant profiles that present specific challenges for wastewater treatment and influence the selection of suitable reactive media for permeable reactive barriers (PRBs).

Table 1.

Major sources of contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in wastewater, representative pharmaceuticals, literature-reported concentration ranges, and their relevance for PRB design and implementation.

Beyond identifying the sources, it is equally important to understand how pharmaceuticals such as ACT and DCF are released into the environment and the associated ecotoxicological risks. Environmental pathways and ecotoxicological impacts of ACT and DCF are summarized schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Environmental pathways and ecotoxicological impacts of ACT and DCF. Pharmaceuticals released from production, wastewater, and soil can enter aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, where they exert toxic effects on plants, microorganisms, fish, and algae. Scheme developed by the authors based on literature analysis.

3.2. Hospital and Clinical Sources

Clinical establishments and hospitals represent one of the most concentrated point sources of CECs in sewer systems. Unlike municipal wastewater, which contains diluted pharmaceutical residues primarily originating from households, hospital effluents contain markedly higher concentrations of biologically active compounds, including analgesics, antibiotics, cytostatics, radiocontrast media and disinfectants [21,46,87,88]. This elevated load results from intensive drug administration, short hydraulic retention times within internal sewer systems and, critically, the widespread absence of dedicated onsite treatment units in most hospitals. Consequently, hospital discharges disproportionately elevate the pharmaceutical burden received by wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and complicate the removal of target compounds such as ACT and DCF [89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99].

Monitoring data are not uniformly collected across all hospitals, as pharmaceutical concentrations in hospital effluents are typically measured only in selected facilities within targeted research projects. Nevertheless, available studies consistently report ACT concentrations in untreated hospital wastewater frequently exceeding 500 µg·L−1 [100] and DCF levels in the range of 10–200 µg·L−1, with occasional peaks above 300 µg·L−1 depending on consumption patterns [89,90,101]. Cytostatics such as cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide are often detected at 0.1–5 µg·L−1 [102,103], while iodinated radiocontrast agents can reach mg·L−1 levels during diagnostic imaging events. These values are substantially higher than typical municipal influent concentrations and show that ACT and DCF belong to the dominant pharmaceutical species in hospital discharges.

From a regulatory perspective, compound-specific maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for ACT and DCF in drinking water have not yet been formally established by major international agencies such as the WHO or the US EPA. Instead, environmental risk assessments rely on predicted no-effect concentrations (PNECs) and environmental quality standards (EQSs) derived from chronic toxicity tests. For ACT, PNECs generally fall in the low µg·L−1 range, whereas for DCF proposed EQSs under the European Water Framework Directive are on the order of 0.04–0.05 µg·L−1 in surface waters, reflecting its comparatively higher ecotoxicological concern. Monitoring studies show that these threshold values can be approached or locally exceeded downstream of WWTPs receiving hospital effluents, which underlines the need for additional polishing steps such as tertiary treatment or PRB-based systems [104,105,106,107,108,109].

Under non-chlorinated environmental conditions, ACT and DCF also undergo biotic and abiotic transformation. ACT is primarily degraded via deacetylation and oxidation to intermediates such as 4-aminophenol, hydroquinone and 1,4-benzoquinone, followed by ring-cleavage to low-molecular-weight carboxylic acids. Some of these metabolites, particularly 4-aminophenol and hydroquinone, remain redox-active and can contribute to oxidative stress in aquatic organisms. For DCF, microbial and photochemical pathways lead to hydroxylated metabolites (e.g., 4′-hydroxydiclofenac, 5-hydroxydiclofenac), diclofenac-lactam and carboxylated derivatives. These products are generally more polar and less bioaccumulative than the parent compound, but several studies have shown that they can still induce sub-lethal effects, including oxidative stress and tissue damage in exposed biota. Thus, both parent compounds and their transformation products must be considered when designing treatment technologies and monitoring strategies.

In addition to chemical contaminants, hospital effluents frequently harbor resistant microbial strains and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). Elevated antibiotic concentrations (10–100 µg·L−1) create strong selective pressures that promote the proliferation of resistant bacteria and facilitate horizontal gene transfer [96,103,104,105]. Although PRBs are not designed to directly remove ARGs, they can reduce antibiotic concentrations and overall microbial loads, thereby indirectly mitigating the selective conditions that sustain ARG persistence and dissemination. Taken together, these characteristics identify hospital outlets as strategic intervention points: they are both major sources of ACT and DCF and priority locations where PRB systems—either as stand-alone barriers or as part of hybrid treatment trains—could be deployed to intercept pharmaceutical plumes before they mix with municipal wastewater and enter receiving waters [110,111,112,113,114].

Overall, published ecotoxicological studies consistently show that paracetamol and diclofenac exert measurable effects on aquatic organisms at concentrations spanning from the mg L−1 range in acute tests to the low µg L−1 range in chronic exposures. For ACT, acute LC50 and EC50 values for fish, crustaceans and algae are generally in the tens to hundreds of mg L−1, indicating relatively low acute toxicity, whereas sublethal endpoints such as growth inhibition and oxidative stress have been reported at sub-mg L−1 levels. In contrast, DCF exhibits markedly higher ecotoxicological concern: acute EC50 values for algae, macrophytes and invertebrates are often one to two orders of magnitude lower than for ACT, and chronic NOEC or EC10 values for fish have been reported in the low µg L−1 range, associated with histopathological lesions in gills, kidneys and liver, as well as reproductive and developmental impairments [115]. These data, which are discussed in detail in the cited ecotoxicological literature, underpin the inclusion of DCF in environmental quality standards and confirm that even trace, environmentally relevant concentrations of both ACT and DCF can contribute to mixture toxicity in aquatic ecosystems.

3.3. Industrial Sources

Industrial activities are recognized as some of the most significant contributors to CECs in aquatic environments. While municipal and hospital effluents discharge pharmaceuticals at µg/L levels, industrial facilities—particularly pharmaceutical manufacturing plants—are capable of releasing CECs at concentrations several orders of magnitude higher [116]. The resulting effluents often contain complex mixtures of pharmaceuticals, solvents, dyes, and chemical intermediates, posing severe challenges to conventional wastewater treatment systems.

3.4. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

Pharmaceutical production facilities represent critical “hotspots” for environmental contamination, particularly in regions with intensive generic drug manufacturing. Although municipal WWTPs typically receive only diluted pharmaceutical residues, effluents from industrial facilities may contain active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) at concentrations several orders of magnitude higher. In most countries, pharmaceutical manufacturers are legally required to implement onsite pre-treatment systems to reduce API concentrations before discharge into municipal sewer networks. These systems commonly include advanced oxidation processes, adsorption units, and membrane technologies. In recent years, several facilities have begun piloting nano-enabled technologies—such as nano-adsorbents and catalytic nanoparticles—for improved API degradation; however, their adoption remains limited to experimental or demonstration-scale applications due to cost and regulatory uncertainty.

Industrial operators are also obligated to perform routine sampling of wastewater at discharge points, although in practice monitoring frequency and analytical coverage vary substantially between plants and across regions. While ACT is relatively biodegradable, DCF remains particularly problematic due to its hydrophobicity (logKow ≈ 4.5), low biodegradability, and resistance to microbial and oxidative degradation [116,117]. Municipal WWTPs may reduce DCF concentrations to 0.1–3 µg/L, whereas pharmaceutical factories can release effluents containing concentrations two to three orders of magnitude higher, exceeding the treatment capacity of downstream WWTPs, and causing direct ecological harm [13,118,119]. Even ACT, when discharged at high levels (>1 mg/L), can pose toxicity risks to aquatic organisms and form hazardous transformation products under oxidative treatment [30,112,120].

These findings illustrate that while some pharmaceutical manufacturing plants operate dedicated pre-treatment systems, many facilities still discharge inadequately treated effluents, underscoring the need for stricter monitoring requirements, wider implementation of advanced treatment technologies, and the potential for emerging nano-enabled solutions to play a future role in industrial wastewater management.

Chemical and textile industries. Beyond pharmaceuticals, chemical processing and textile dyeing industries also contribute to the release of CECs. Textile effluents frequently contain high concentrations of dyes, surfactants, and finishing agents, many of which are resistant to biodegradation and may act as co-contaminants that interfere with pharmaceutical removal [115]. Solvents and industrial additives, including phthalates and bisphenols, are also present in chemical manufacturing wastewater and have been identified as endocrine-disrupting compounds [101,121,122,123]. These substances complicate wastewater treatment by contributing to high chemical oxygen demand (COD), variable pH, and complex pollutant mixtures that reduce the efficiency of biological and physicochemical treatment processes.

Environmental and regulatory implications. Industrial effluents containing high pharmaceutical loads pose acute risks to local environments. Elevated DCF concentrations have been linked to fish mortality, renal damage in aquatic vertebrates, and bioaccumulation in benthic organisms [46]. Chronic exposure scenarios are particularly concerning in regions where rivers receiving pharmaceutical effluents serve as drinking water sources for downstream communities. The ecological consequences of cytostatic, antibiotics, and endocrine-disrupting compounds discharged from industrial sources include genotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, and the proliferation of antimicrobial resistance [120,124,125].

Implications for PRB deployment. The extreme pollutant loads and complexity of industrial effluents highlight both challenges and opportunities for PRB applications. Traditional PRBs designed for groundwater remediation may not withstand the chemical strength and flow variability of industrial discharges. However, modified PRBs employing robust reactive media—such as metal-doped geopolymers, functionalized activated carbon, and CNT-based composites—offer promising potential for intercepting industrial streams before they enter municipal systems or natural water bodies [71].

For pharmaceutical manufacturing plants, PRBs have been proposed as passive polishing units positioned at effluent discharge points to adsorb or degrade active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), especially hydrophobic compounds such as DCF. Although the concept is well supported by laboratory experiments, only a limited number of pilot-scale studies have directly evaluated PRB deployment at industrial outlets. Existing pilot studies demonstrate that PRBs filled with activated carbon, carbon nanotubes, and CNT–geopolymer composites can achieve 70–95% removal of DCF and >90% removal of readily adsorbable APIs under continuous-flow conditions [47,126]. In these investigations, influent and effluent samples were collected at regular intervals—typically daily or weekly—to validate performance stability over time. However, full-scale applications at pharmaceutical factories remain scarce, and most existing studies were performed either under controlled laboratory conditions or at small pilot units treating synthetic or moderately contaminated wastewater. Therefore, further research is needed to verify long-term PRB performance under the high API concentrations, variable pH, and complex chemical matrices characteristic of real industrial effluents, as well as to establish standardized monitoring protocols for routine sampling and regulatory compliance.

3.5. Agricultural Sources

Untreated livestock wastewater is not discharged directly into surface water in the United States; instead, it is commonly stored in lagoons or applied to agricultural fields, where storm runoff or infiltration can transport contaminants into nearby surface and groundwater systems [127,128]. Veterinary antibiotics—such as tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and fluoroquinolones—are frequently detected in agricultural runoff, typically at ng/L to µg/L levels, while hotspots associated with intensive livestock operations may reach concentrations in the tens of µg/L [128,129]. Hormones, including natural estrogens and synthetic contraceptives, are also of concern because endocrine disruption can occur at concentrations of only a few ng/L [128,130]. The land application of treated sewage sludge (biosolids) may further introduce persistent pharmaceuticals into agricultural soils, where accumulation and long-term leaching have been documented. Clarke and Smith [131] detected DCF and carbamazepine in biosolid-amended soils, raising concerns about their persistence in the environment.

Regarding treatment practices, agricultural waste streams are rarely treated using conventional wastewater treatment processes before entering the environment. Most livestock operations rely on manure storage lagoons, anaerobic digestion, constructed wetlands, or land-application systems rather than chemical or biological treatment specifically designed for pharmaceutical removal. When no treatment is applied, regulatory frameworks typically require setback distances from waterways, nutrient management plans, and restrictions on land application during rainfall events to reduce the risk of runoff. However, these measures primarily address nutrients and pathogens and do not effectively remove pharmaceuticals, which remain highly mobile and persistent. As a result, agricultural sources can act as diffuse contributors of CECs to downstream water bodies, underscoring the need for improved pre-treatment strategies and expanded monitoring.

From an ecotoxicological perspective, antibiotics in agricultural runoff contribute to the selection and proliferation of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) in soil and aquatic microbiomes [132]. Hormones and pesticides, even at trace concentrations, are linked to reproductive toxicity in fish and amphibians, raising alarms for biodiversity in agricultural watersheds.

In terms of treatment, agricultural runoff poses unique challenges due to its diffuse and intermittent nature. Unlike point sources such as hospitals or industrial discharges, agricultural inputs are distributed across landscapes and may vary seasonally. This makes centralized treatment impractical. Permeable reactive barriers (PRBs), when strategically located along field drainage systems or at the interface with receiving water bodies, offer a promising passive solution. Geopolymer-based PRBs could be tailored for cationic antibiotics, while carbon nanotube composites provide strong sorption of hydrophobic pesticides and hormones [132,133]. Pilot-scale applications have suggested that PRBs can reduce antibiotic loads in agricultural runoff by more than 70%, though long-term performance under variable hydraulic conditions remains to be validated [7,62].

3.6. Stormwater and Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs)

Urban stormwater and combined sewer overflows (CSOs) are episodic but significant sources of CECs. During heavy rainfall events, untreated wastewater mixed with stormwater may bypass WWTPs entirely, discharging directly into rivers, lakes, or coastal zones [115]. This results in sudden spikes of pollutants that can exceed the buffering capacity of receiving environments.

Stormwater carries hydrocarbons, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), tire wear particles, plastic additives, and trace pharmaceuticals from roads, landfills, and improperly disposed wastes [125]. Concentrations of pharmaceuticals in stormwater are typically lower than in hospital or industrial effluents, but their variability is much higher. Episodic peaks of ACT and DCF in the range of several µg/L have been observed following urban storm events. These transient discharges can cause acute toxic effects on aquatic organisms, particularly in small streams and low-flow systems.

Combined sewer overflows are especially problematic in older urban areas with integrated stormwater and wastewater networks. A single overflow event can release massive amounts of untreated wastewater, including pharmaceuticals, ARGs, and other CECs, into the environment [125]. Unlike continuous sources, CSOs are difficult to predict and control, creating monitoring and mitigation challenges. The prevalence of stormwater and CSO discharges highlight the need for adaptability of treatment options. PRBs could be integrated into stormwater retention basins or constructed wetlands as passive polishing units. Reactive media with high adsorption capacity, such as activated carbon or biochar composites, may help buffer episodic spikes in pharmaceutical concentrations. However, their long-term performance under fluctuating hydraulic loads and particulate matter content remains underexplored [76].

3.7. Implications for PRB Deployment

The diverse sources of CECs—from continuous domestic and hospital effluents to intermittent agricultural runoff and stormwater surges—illustrate the complexity of mitigating micropollutant pollution. While municipal WWTPs effectively remove bulk organic matter, they are not optimized for trace CECs such as ACT and DCF. PRBs provide a flexible platform that can be tailored to different contaminant profiles and hydraulic settings.

PRBs equipped with carbonaceous media such as activated carbon (AC) and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have demonstrated >90% removal of ACT and 70–95% removal of DCF in laboratory and pilot-scale systems treating hospital and domestic effluents [5,7,134]. Hybrid PRBs incorporating geopolymer–CNT composites have achieved similar efficiencies for DCF and have shown 60–90% removal for selected cytostatic agents under controlled flow conditions. Functionalized geopolymers combined with AC have been tested for industrially impacted wastewaters, achieving 70–90% removal even under elevated pharmaceutical loads. Distributed PRBs installed along agricultural drainage channels have shown 50–85% removal of veterinary antibiotics and hormones, depending on flow rate, media type, and contaminant mixture.

However, PRBs are not universally applicable to all treatment plants. Their deployment is most suitable for point source discharges, such as hospital outlets, pharmaceutical factory effluents, drainage ditches, stormwater channels, or small WWTP polishing stages, where hydraulic loads are moderate and flow paths can be controlled. In large centralized WWTPs with high and variable flows, PRBs cannot replace primary or secondary treatment but may serve as complementary tertiary polishing units. Thus, while PRBs exhibit high treatment efficiency for a range of pharmaceuticals, their practical use depends on site-specific hydraulic, chemical, and operational conditions.

To date, the use of PRBs specifically targeting ACT and DCF remains largely confined to laboratory column studies and a limited number of pilot-scale systems. Most experiments have been carried out in packed-bed columns or small pilot trenches treating synthetic solutions or pre-treated WWTP effluents containing mixtures of pharmaceuticals. Reported influent concentrations typically range from several µg/L to a few tens of µg/L for ACT and DCF, and effluent concentrations are often reduced to below 0.1–1 µg/L under optimized conditions, corresponding to >90% removal for ACT and 70–95% for DCF. Field-scale PRBs have been widely implemented for other contaminants such as chlorinated solvents and metals, demonstrating the long-term hydraulic and structural feasibility of this technology, but full-scale barriers dedicated specifically to pharmaceutical removal have not yet been reported. Pilot systems that integrate reactive barriers into soil–aquifer treatment schemes or tertiary polishing units indicate that the PRB concept can be adapted to complex wastewater matrices, but further research is needed to validate long-term performance under variable flow conditions and in the presence of multiple co-contaminants.

The analysis of CEC sources demonstrates that pharmaceuticals such as ACT and DCF enter aquatic systems through multiple pathways, with concentrations ranging from ng/L in diffuse agricultural runoff to mg/L in industrial hotspots. Domestic and hospital effluents provide continuous inputs, while industrial discharges and CSOs represent episodic but highly concentrated releases. Conventional WWTPs cannot adequately mitigate these inputs, particularly for recalcitrant compounds such as DCF. By summarizing concentration ranges and source-specific challenges (Table 1), this review highlights the necessity for adaptable and resilient treatment strategies. PRBs, when tailored with advanced reactive media, provide a versatile platform to intercept CECs across different settings, from household effluents to industrial outfalls. This synthesis underscores the urgency of integrating PRBs into wastewater management frameworks to address both continuous and episodic pollution.

4. Removal of ACT and DCF Using PRBs

4.1. Other Treatment Technologies

Besides PRBs, several other treatment technologies have been studied for the removal of pharmaceuticals and related contaminants of emerging concern. Constructed wetlands (CWs) provide a cost-effective, nature-based solution that relies on plant uptake and microbial degradation, though their efficiency is often limited for recalcitrant compounds [135]. Adsorption processes using AC and biochar are widely applied; AC exhibits high removal efficiency across a broad spectrum of pharmaceuticals but involves higher costs, whereas biochar offers a lower-cost alternative with variable performance depending on feedstock and activation method [11,43,44]. Membrane bioreactors (MBRs), which combine biological treatment with membrane filtration, produce high-quality effluent but face challenges such as high energy demand and membrane fouling [15,89]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), including ozonation, photocatalysis, and solar photodegradation, achieve efficient degradation of persistent pharmaceuticals, although they require substantial energy input and may generate potentially harmful by-products [3,33]. Collectively, these technologies complement PRBs by offering alternative or integrated solutions, and their selection depends on site-specific conditions, economic feasibility, and the target pollutants present in wastewater. The efficiency of AC and biochar (BC) in removing pharmaceutical contaminants is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative Performance of AC and BC in the Removal of Pharmaceutical Contaminants.

It should be emphasized that most of the performance data summarized in this section originate from laboratory- and pilot-scale studies, often conducted with synthetic or pre-filtered effluents under controlled conditions. Full-scale applications of advanced oxidation processes, membrane filtration and activated carbon adsorption for the specific removal of ACT and DCF from WWTP effluents remain limited and are typically implemented as polishing steps at a small number of large treatment plants. Consequently, the reported removal efficiencies should be interpreted as indicative of the technological potential rather than as representative of widespread full-scale practice.

4.2. Paracetamol

Although ACT and DCF are not directly applied in agricultural practices, their presence in agricultural environments has been frequently reported through indirect pathways. These include the land application of sewage sludge and biosolids, irrigation with treated wastewater, and diffuse inputs from domestic and hospital effluents that enter agricultural watersheds. Importantly, both ACT and DCF are among the most detected pharmaceuticals worldwide and are widely employed as benchmark pollutants in laboratory and pilot-scale studies. Their contrasting physicochemical properties—ACT being polar and more readily biodegradable, while DCF is hydrophobic, persistent, and resistant to biodegradation—make them valuable model compounds for assessing PRB media performance under realistic wastewater and mixed-source contamination scenarios.

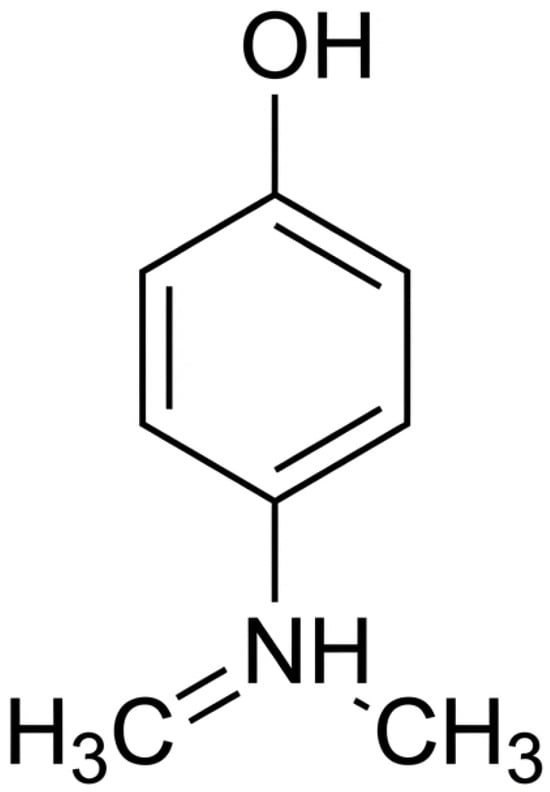

Paracetamol (acetaminophen, ACT) is one of the most widely consumed over-the-counter analgesics and antipyretics worldwide, with global production exceeding 100,000 tons annually. Its physicochemical characteristics—moderate polarity (logKow ≈ 0.46), high water solubility (≈14 g·L−1 at 25 °C), and weakly acidic pKa of ≈9.5—explain its comparatively high biodegradability under aerobic conditions. ACT (C8H9NO2, MW 151.16, IUPAC name N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) acetamide) is commonly used to treat headaches, back pain, and rheumatic ailments. The molecular structure of ACT is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of ACT. Drawn by the authors using structural data from PubChem [136].

Despite its relatively favorable biodegradability, ACT is consistently detected in WWTP effluents at concentrations typically ranging from 0.1 to 10 µg·L−1 and reaching several hundred µg·L−1 in hospital discharges, reflecting incomplete removal during secondary treatment. Toxicological investigations highlight the considerable ecological impacts of ACT and its transformation products: concentrations above 160 mg·L−1 have been associated with mortality in Oryzias latipes (Japanese medaka), while growth inhibition of Scenedesmus subspicatus has been reported at levels as low as 1.34 mg·L−1. Even at much lower, environmentally relevant concentrations, chronic exposure may contribute to oxidative stress and the selection of antimicrobial resistance in aquatic microbiota [49,99,133,134,135,137,138,139,140].

Under non-chlorinated environmental conditions, ACT is primarily degraded via microbial deacetylation and oxidation to intermediates such as 4-aminophenol, hydroquinone and 1,4-benzoquinone, followed by ring-cleavage to low-molecular-weight carboxylic acids. These metabolites remain redox-active and can still induce sub-lethal effects in exposed organisms, indicating that partial transformation does not automatically eliminate ecotoxicological risk. In chlorinated systems, such as drinking water disinfection or tertiary treatment, ACT rapidly reacts with chlorine at the amino group, forming chlorinated quinone derivatives including 1,4-benzoquinone and N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), which are recognized for their hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic properties. Thus, both ACT and its transformation products need to be controlled.

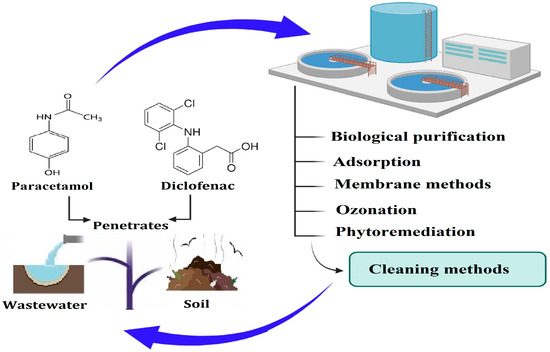

A range of treatment technologies has been investigated for ACT and DCF removal. Biological treatment in conventional activated sludge systems typically removes 70–90% of ACT but is much less efficient for DCF. Adsorption onto activated carbon (AC) can achieve >90% removal for both compounds, whereas biochar (BC) generally shows more variable performance depending on feedstock and activation. Membrane processes (RO, NF) and advanced oxidation (e.g., ozonation) are capable of almost complete removal but are associated with high energy demand, membrane fouling or the formation of potentially toxic by-products. A concise comparison of ACT and DCF removal by these major technologies is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Methods of treatment of ACT and DCF.

The main sources, concentration ranges and environmental pathways of ACT and DCF in wastewater and aquatic environments are summarized in Figure 3. As the figure indicates, both compounds are continuously introduced into surface and groundwaters through domestic, hospital, industrial and agricultural routes, which underlines the need for robust multi-barrier treatment strategies.

Figure 3.

Main sources and pathways of ACT and DCF in wastewater and aquatic environments. Scheme developed by the authors based on the general literature on pharmaceutical contamination in wastewater.

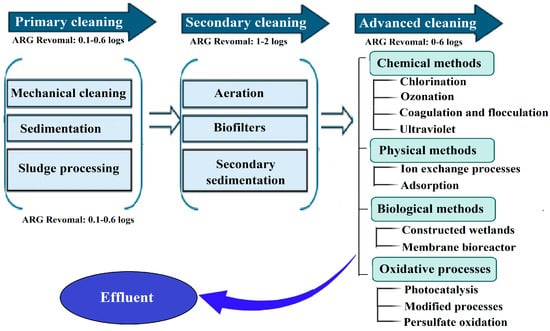

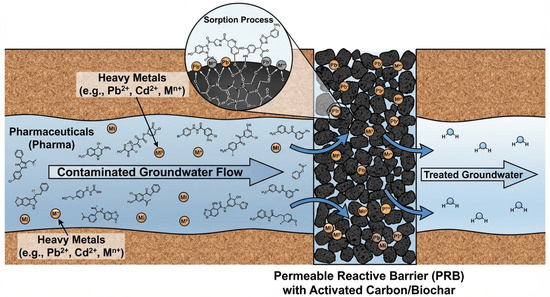

PRBs provide a sustainable option for ACT removal, particularly in subsurface plumes and as tertiary polishing steps downstream of WWTPs. In PRB-type systems, ACT is primarily removed via adsorption and, in some cases, catalytic transformation within the reactive media. Geopolymer-based media offer ion-exchange sites and surface hydroxyl groups that can participate in hydrogen bonding and surface complexation with ACT. Activated carbon provides a large specific surface area and a microporous network that favor pore filling, hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions between the aromatic ring of ACT and the carbon surface. Biochar derived from agricultural residues can serve as a lower-cost alternative, albeit with more variable performance due to differences in pore structure and surface chemistry. Typical PRB configurations and the main types of reactive media used for the removal of pharmaceuticals, including ACT and DCF, are schematically illustrated in Figure 4. The scheme shows how contaminated groundwater or wastewater is directed through a reactive zone filled with materials such as granular activated carbon, biochar, Fe-/Al-modified geopolymers and CNT-based composites, where sorption, ion exchange and redox processes attenuate ACT and DCF before the plume reaches downgradient receptors.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of primary, secondary and advanced wastewater treatment stages and indicative ranges of antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) removal at each step.

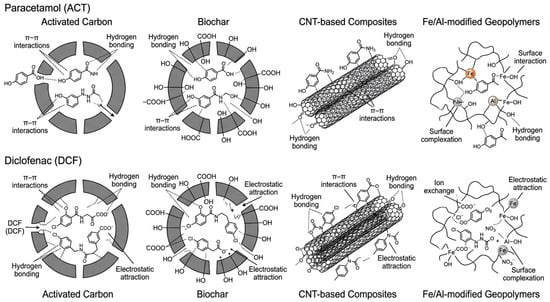

To synthesize the discussion above, the dominant interaction mechanisms of ACT and DCF with the main reactive media considered in this review are summarized schematically in Figure 5. For each pharmaceutical, the figure highlights how π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attraction, ion exchange and surface complexation contribute to adsorption on activated carbon, biochar, CNT-based composites and Fe-/Al-modified geopolymers.

Figure 5.

Conceptual illustration of the main interaction mechanisms governing the adsorption of paracetamol (ACT, top row) and diclofenac (DCF, bottom row) on activated carbon, biochar, CNT-based composites and Fe-/Al-modified geopolymers. The scheme emphasizes the relative roles of π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attraction, ion exchange and surface complexation for each type of reactive medium.

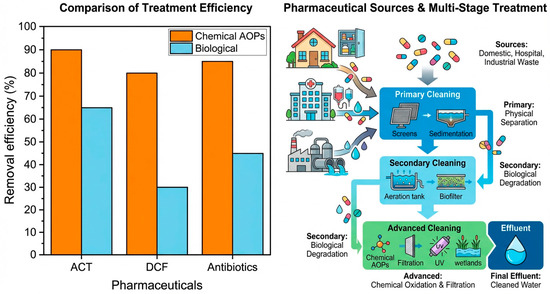

In addition to the multi-stage configuration of wastewater treatment plants, it is important to compare how efficiently different treatment approaches remove specific pharmaceuticals. Figure 6 provides an illustrative comparison of typical removal efficiencies reported for ACT, DCF and representative antibiotics by conventional biological processes and by chemical advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). As can be seen, AOPs generally achieve higher removal of ACT and particularly of more persistent compounds such as DCF, whereas biological treatment shows lower and more variable efficiencies, especially for DCF and many antibiotics. This comparison highlights the need to integrate high-performance chemical or hybrid processes into treatment trains when targeting ACT, DCF and antibiotic residues, and motivates the development of complementary passive technologies such as PRBs for polishing residual concentrations.

Figure 6.

Illustrative comparison of typical removal efficiencies of paracetamol (ACT), diclofenac (DCF) and representative antibiotics by conventional biological processes, blue bars, and chemical advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), orange bars, based on data compiled from the literature.

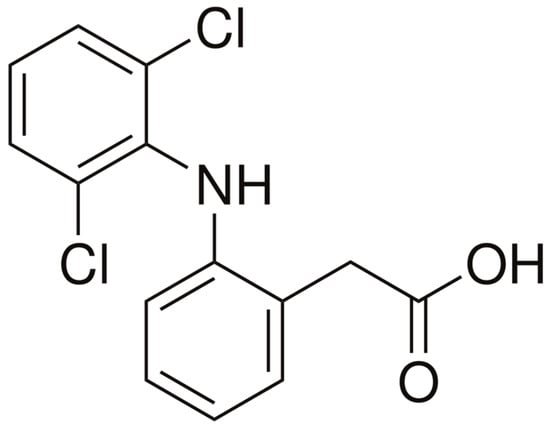

4.3. Diclofenac

Diclofenac (DCF) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) extensively prescribed worldwide and recognized as one of the most problematic pharmaceuticals in aquatic environments [9,141]. Its widespread use, combined with poor removal in conventional wastewater treatment plants, has led to frequent detection of DCF in influents, effluents and receiving waters on all continents. Typical concentrations reported in WWTP effluents range from 0.1 to 3 µg/L, while levels in surface waters downstream of discharge points are usually in the ng/L–µg/L range, depending on dilution and local consumption patterns [37,72,124]. Even at environmentally relevant concentrations of about 1 µg/L, DCF has been associated with kidney damage in fish, oxidative stress in aquatic organisms and reproductive toxicity in invertebrates [142]. The molecular structure of DCF is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Molecular structure of DCF. Drawn by the authors using structural data from PubChem (CID 3033) [143].

DCF exhibits markedly different physicochemical properties compared with ACT. It has low water solubility (≈2.37 mg/L at 25 °C), pronounced hydrophobicity (logKow ≈ 4.5) and a pKa of ≈4.1, which means that at circumneutral pH it exists predominantly in its anionic form [4,36]. These characteristics contribute to its persistence and poor removal in conventional secondary treatment, where biological processes often achieve less than 30% DCF elimination [37,72]. In addition, DCF shows a strong tendency to partition to organic matter and solid phases, which may temporarily remove it from the water column but can lead to accumulation in sediments and benthic organisms.

In non-chlorinated aquatic environments, DCF undergoes microbial and photochemical transformation. Reported transformation products include hydroxylated derivatives such as 4′-hydroxydiclofenac and 5-hydroxydiclofenac, diclofenac-lactam and various carboxylated metabolites. These products are more polar and less bioaccumulative than the parent compound, but several studies have shown that they can still induce oxidative stress and histopathological changes in exposed biota, contributing to mixture toxicity when co-occurring with DCF and other pharmaceuticals. Under chlorinated conditions, additional halogenated products may be formed, which can further increase toxicological concern. Consequently, both DCF and its transformation products must be considered when evaluating treatment performance and environmental risk [144,145,146].

4.4. Comparative Analysis

A comparative assessment of the physicochemical properties of ACT and DCF provides valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities associated with their removal from wastewater. While both compounds are frequently detected in municipal and industrial effluents, their environmental behaviors differ significantly due to variations in solubility, ionization potential, hydrophobicity, and biodegradability [46,147].

Such differences strongly influence the design and performance of PRBs. For example, ACT’s higher polarity and solubility enhance its biodegradability but reduce its affinity for nonpolar sorbents, whereas DCF’s hydrophobic and aromatic characteristics promote strong interactions with carbon-based materials but demand cationic binding sites due to its anionic nature at neutral pH [71,72]. These contrasts underscore the importance of tailoring PRB media to match specific contaminant profiles rather than adopting a “one-size-fits-all” approach.

Table 4 presents the physicochemical properties of ACT and DCF, highlighting their significance in the design of PRBs. ACT is characterized by its higher biodegradability and increased water solubility; however, its polar nature renders it less compatible with purely hydrophobic sorbents. Conversely, DCF’s hydrophobic and aromatic characteristics make it particularly amenable to removal by carbon-based materials, although its anionic charge necessitates the use of media with cationic sites.

Table 4.

Physicochemical properties of ACT and DCF relevant to their environmental behavior and removal in PRBs. All values are compiled from previously published studies [83,103,110,111,114,115,116,148,149].

The physicochemical parameters summarized in Table 4 are essential for understanding the environmental behavior of ACT and DCF and their removal mechanisms in permeable reactive barrier (PRB) systems. These properties—such as pKa, logKow, aqueous solubility, and molecular descriptors—directly influence contaminant mobility, degree of ionization, sorption affinity, and reactivity with PRB media. The values presented in the table were not experimentally measured in the present study; instead, they were compiled from peer-reviewed literature sources [83,103,110,111,114,115,116,148,149].

In the referenced studies, these parameters were determined using internationally standardized analytical methods, including OECD Test Guidelines 105 (solubility), 107/117 (partition coefficient), and 112 (acid dissociation constant). The inclusion of these literature-based physicochemical properties provides a validated foundation for interpreting ACT and DCF behavior during adsorption, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic partitioning within different PRB materials.

4.5. Standardized Biodegradation Tests (OECD/ISO)

Standardized ready biodegradation tests (e.g., the OECD 301 series) play a foundational role in environmental fate assessment by providing a stringent screen for a compound’s potential to undergo rapid and essentially complete biological mineralization under aerobic conditions. Under these tests, substances must achieve high levels of DOC removal or CO2 evolution within defined criteria to be considered readily biodegradable; this status is commonly interpreted as evidence of low persistence in many natural aquatic compartments. However, the very strict conditions of ready tests—low inoculum density, short duration, and exclusion of adapted biomass—can lead to false negatives, particularly for complex or slow-degrading chemicals, despite the fact that they may be broken down under real-world conditions [150].

Inherent biodegradability tests (OECD 302 series) occupy the next tier in the OECD/ISO hierarchy and are deliberately less stringent, using higher microbial biomass and allowing for longer or more favorable degradation conditions. Because of this, inherent tests have a higher probability of detecting biodegradation for compounds that fail ready tests and are regarded as more predictive of behavior in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and technical systems. Substances that show significant degradation in an inherent test are likely to be biodegradable under many natural or engineered treatment conditions, even though they may not meet the strict ready criteria. Thus, in a tiered assessment strategy, ready tests efficiently identify readily biodegradable substances, while inherent tests provide essential information on the potential for biodegradation under more realistic, biomass-rich conditions such as WWTPs, helping to bridge the gap between laboratory screening and environmental or technical treatment outcomes [150].

Thus, standardized biodegradation tests provide additional insight into the environmental persistence of ACT and DCF. In ready and inherent biodegradability assays according to OECD and ISO guidelines (e.g., OECD 301/302), paracetamol is generally classified as readily biodegradable, typically reaching the pass levels for dissolved organic carbon or theoretical oxygen demand within the 28-day test period. In contrast, diclofenac systematically fails to meet the criteria for ready biodegradability, with low mineralization and removal yields being reported even in prolonged test configurations. These outcomes corroborate field observations, where ACT is efficiently attenuated in many biological treatment systems, whereas DCF exhibits pronounced persistence and tends to accumulate in effluents and receiving waters. Including data from OECD/ISO tests is therefore essential for understanding why ACT can, at least in principle, be managed by optimized biological processes, while DCF requires additional advanced treatment or sorptive barriers such as PRBs. These data are presented in Table 5, the values shown representing typical ranges reported in the literature under the specified test conditions. Exact outcomes depend strongly on inoculum source, acclimation, test substance concentration and analytical endpoint (DOC, CO2 evolution, parent compound removal).

Table 5.

Biodegradation of diclofenac and paracetamol in standardized OECD tests.

5. Permeable Reactive Barriers (PRBs)

The restoration of polluted groundwater is essential to ensure the sustainability of this water source, and technologies for both active and passive groundwater restoration have been introduced to this end. Passive recovery with the help of PRBS has been applied for 1995 year. Figure 8 shows how PRBs are used to restore groundwater.

Figure 8.

Principle of groundwater remediation using a PRB. In the context of this review, the PRB may be filled with carbon-based media such as activated carbon or biochar, which remove pharmaceuticals and, partly, heavy metals via sorption processes. Scheme developed by the authors based on literature analysis.

In groundwater remediation, a distinction is commonly made between active and passive restoration technologies. Active restoration involves externally driven processes such as pump-and-treat systems, in situ chemical oxidation or reduction, and recirculation wells, where energy input and intensive operation and maintenance (O&M) are required to extract, treat, and re-inject groundwater. In contrast, passive restoration relies on natural hydraulic gradients and in situ treatment zones, including permeable reactive barriers (PRBs), reactive zones coupled to soil–aquifer treatment, and monitored natural attenuation. PRBs therefore belong to the class of passive remediation technologies: once installed, they operate with minimal energy input, and treatment is achieved as contaminated groundwater or effluent flows through the reactive zone under natural or slightly modified hydraulic conditions.

PRBs seem to be an attractive option, since the plume of pollutants consists of various groundwater pollutants, such as heavy metals and organic and inorganic pollutants, moves through the reactive zone along a natural hydraulic gradient, providing passive treatment without attracting external energy. For this reason, a full recovery can take many years. This concept can be extended to apply PRBs in the treatment of persistent/priority pollutants as we focus on this work.

5.1. Design and Configuration

The appropriate PRB configuration is crucial for an engineering project, which must be selected taking into account specific hydrogeological conditions and characteristics of the pollutant plume. The most common PRB configuration is a continuous permeable reactive barrier (C-PRB) located perpendicular to the groundwater flow, otherwise known as a crossflow.

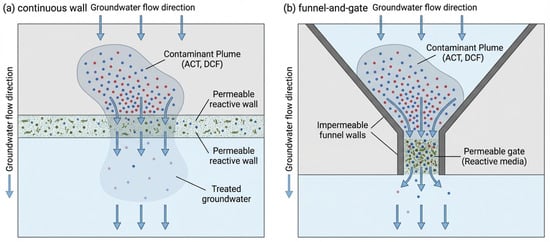

Another configuration is a funnel and a gate. The system consists of a permeable gate (as a reactive medium) located between two impermeable walls that direct the contaminated plume to the reactive medium. The precise, adequate, optimized PRB design increases processing efficiency and reduces maintenance costs. PRB processing is more economical than traditional pump and processing technology. Figure 9 shows a comparison of two widely used configurations, a solid wall or trench and a funnel with a gate. The choice between the two configurations depends on the hydrogeological parameters of the site and the cost of reactive materials. The funnel and gate configuration are recommended for PRB design, as this installation requires less reactive material in the processing area. These limitations can be eliminated by using an effective barrier design that takes into account the plume and the characteristics of the site.

Figure 9.

Schematic illustration of PRB configurations: (a) continuous wall; (b) funnel-and-gate design. Scheme developed by the authors based on literature data.

An important condition for successful elimination of consequences is the requirement that a plume of pollutants pass through a jet gate of a given thickness b at a certain velocity. This means that the pollutant will come into contact with the reactive environment at the specified time tRES (residence time). Considering the SF safety factor, it is extremely important to design a reaction gate with sufficient thickness. The wall thickness of the PRB can be estimated by Equation (1).

b = υ · tres SF

Another important part is the composition of the barrier. Mixing with several solid materials such as solid industrial waste, mineral materials, carbon-containing materials, (reducing) graphene oxide, and biochar to create permeable barriers is popular in the production of reactive materials due to simplicity, cost, environmental friendliness, and limited use of chemical agents.

In mixed reactive media, the removal of contaminants does not rely on the formation of chemical bonds between the individual components. Instead, each component contributes its own removal mechanism, and the combined material often achieves higher overall performance than any single sorbent. For example, when activated carbon, biochar, zeolites, or sand are blended with materials that have high hydraulic conductivity, the resulting composite improves water permeability while maintaining strong sorption potential.

The statement that the mixed material “can disinfect multicomponent contaminants” requires clarification. In practice, mixed reactive media do not disinfect contaminants in the strict microbiological sense. Rather, they remove or transform different classes of pollutants through multiple simultaneous mechanisms, including adsorption, ion exchange, redox reactions, surface catalysis, and physical filtration. Thus, the term “disinfection” should be interpreted as the ability of the composite to reduce concentrations of multiple pollutant classes (e.g., pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, nutrients, and organic micropollutants) rather than its ability to inactivate pathogens.

Overall, the enhanced removal efficiency of mixed materials results from synergistic effects: one component may provide high sorption capacity for pharmaceuticals, another may contribute redox activity for transformation reactions, and a third may improve hydraulic conductivity or prevent clogging. This multi-mechanism interaction explains why mixed PRB materials often perform better than single-media barriers.

The choice and use of PRB materials depend on conditions such as the type of target pollutants (organic or inorganic), their concentration, the mechanisms necessary for their removal (biodegradation, adsorption, etc.), as well as the cost of the materials. In addition, considerations affecting the choice of materials for permeable reactive barriers include:

Hydraulic conductivity: the barrier must have sufficient permeability to allow the passage of contaminated groundwater without significantly slowing its velocity. Environmental compatibility: The material used should not potentially release toxic substances into the host environment. Long-term physical and chemical stability: The material must have sufficient long-term stability to eliminate the need for maintenance of the barrier during its service life.

It is important to clarify that PRB technology is traditionally designed for in situ groundwater remediation, where contaminated groundwater flows passively through a subsurface reactive zone. In contrast, wastewater treatment typically relies on engineered reactors, aeration tanks, membranes, or adsorption units under controlled conditions. Thus, PRBs cannot be used as a “single universal technique” that identically treats both groundwater and wastewater.

However, the underlying reactive materials (e.g., activated carbon, biochar, zero-valent iron, geopolymers) employed in PRBs can also be adapted for use in ex situ wastewater treatment units. In this sense, the concept is not that the same PRB installation treats both systems, but that the same reactive media and mechanisms—sorption, ion exchange, redox reactions, or catalytic degradation—can operate in different treatment configurations. For groundwater, the materials are placed in a permeable subsurface trench; for wastewater, they may be applied in packed-bed columns, filters, hybrid systems or polishing units after conventional treatment.

Therefore, the “expansion” of PRB technology in this work refers not to applying an identical PRB structure to wastewater, but to the transferability of reactive media and their mechanisms to different treatment contexts. The specific performance still depends on water chemistry, hydraulic conditions, contaminant type, and operational parameters. Clarifying this distinction highlights that while groundwater PRBs and wastewater treatment units differ in design, they can share the same reactive principles and materials, enabling more sustainable and comprehensive contaminant removal strategies.

5.2. Inexpensive Fillers for Permeable Reactive Barriers

Adsorption is a fundamental mass transfer process suitable for removing pollutants, especially organic ones, from wastewater streams. According to the different forces of attraction between substances, adsorption can be divided into chemisorption and physical adsorption.

During physical adsorption, pollutants accumulate on the surface of the adsorbent due to physical forces such as van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, polarities, and spatial forces. Dipole-induced dipole interactions and the chemistry of π-π interactions also cause adsorption effects. Chemisorption of molecular and atomic particles on the surfaces of solid materials is a central concept in chemistry, physics, and materials science. The main difference is that chemisorption involves strong chemical interactions and often leads to irreversible binding, while physical adsorption involves weaker, non-chemical interactions and is usually reversible [39,151]

Moreover, the adsorbent dosage, temperature, pH, adsorbate concentration, and contact time, among others, are some of the factors that directly affect adsorption. The physical presence of the barrier reduces the flow rate, which promotes the deposition of solid particles, while the permeability of the barrier allows solid particles to be filtered by the medium as the runoff passes through it.

PRBs are made of various materials and can be configured in various ways, depending on the location, volume and nature of the wastewater being treated. Some filtration materials may primarily use physical filtration processes to remove pollutants, while other materials such as compost or vegetation may also contribute to the removal of pollutants through chemical and biological reactions within the environment. Due to the mass transfer process, the barrier will be positioned as a tertiary stage of purification at the end of wastewater treatment plants to achieve a higher quality of treated wastewater, which will allow it to be reused in irrigation works [71].

5.3. Operational Costs, Limitations and Future Prospects of PRBs for ACT and DCF Removal

Operational costs and economic feasibility are critical factors when considering the implementation of PRBs for ACT and DCF removal. Compared to conventional pump-and-treat systems, PRBs typically require a higher upfront capital investment associated with site characterization, excavation, and installation of the reactive media, but their long-term operation and maintenance (O&M) costs are considerably lower because treatment occurs passively without continuous energy input or complex mechanical equipment. The dominant cost components for ACT- and DCF-targeted PRBs are the procurement and replacement or regeneration of reactive media (e.g., granular activated carbon, biochar, CNT–geopolymer composites), periodic hydraulic monitoring, and eventual barrier refurbishment after breakthrough. Economic analyses performed for PRBs treating other contaminants indicate that, over a 10–20-year life span, passive barriers can be more cost-effective than active technologies, particularly at sites with moderate and relatively stable flow rates.

Despite these advantages, several limitations must be addressed before PRBs can be widely deployed for pharmaceutical removal. First, the long-term hydraulic performance of PRBs in contact with WWTP effluents is still uncertain: fouling due to particulate matter, biofilm growth, and precipitation of inorganic solids can reduce permeability and shorten the effective life of the barrier. Second, the sorption capacity of carbonaceous media for ACT and especially for DCF is finite, and breakthrough will eventually occur unless media are replaced or regenerated. Third, the presence of natural organic matter and co-contaminants can compete for sorption sites, lowering the effective capacity for target pharmaceuticals and altering breakthrough behavior. Finally, regulatory acceptance of PRBs for tertiary treatment of WWTP effluents is still limited by the lack of standardized design protocols and long-term field data for pharmaceuticals.

Future prospects for PRBs targeting ACT and DCF lie in the development of hybrid and composite reactive media that combine high adsorption capacity with chemical or catalytic functionality. Geopolymer–carbon hybrids and CNT-modified geopolymers show promise for enhancing selectivity toward anionic pharmaceuticals such as DCF while maintaining sufficient mechanical stability and permeability. Coupling PRBs with managed aquifer recharge or soil–aquifer treatment systems also offer a route to increase water reuse while simultaneously attenuating a broad spectrum of contaminants of emerging concern. To enable large-scale implementation, future research should prioritize (i) long-term pilot and field demonstrations under realistic effluent conditions, (ii) mechanistic studies of competitive sorption and transformation pathways for ACT and DCF, and (iii) cost–benefit analyses comparing PRBs with other tertiary treatment options at different scales and hydraulic regimes.

6. Geopolymers

Geopolymers (GP) are one of the environmentally friendly cementing materials, the research of which began in the 1970s. GP attracts a lot of attention for its heat resistance, low permeability, excellent durability, mechanical performance, and other characteristics. GP is an inorganic aluminosilicate material consisting primarily of tetrahedral silica (SiO)4 and alumina (AlO)4, which are formed because of polycondensation of an aluminosilicate-rich precursor and an alkaline activator, resulting in the formation of solidified three-dimensional molecular networks. GP has a wide range of applications depending on the Si/Al 80 ratio used in the synthesis process [152,153].

One of the sources of alumosilicate material is fly ash (FA) and it is the most used and suitable material for geopolymerization waste due to the significant amount produced worldwide, estimated at about 780 million tons per year, and its excellent workability. Fuel assemblies are a by-product produced during the combustion of coal powders and collected by mechanical and electrostatic separators from the flue gases of power plants.

As a result of its large-scale production, there is a growing need to reduce its accumulation, improve the way it is disposed of, and focus mainly on how to reuse this material, allowing it to be returned to the economy and contribute to the development of a closed-loop economy.

While most of GP’s research has focused on the cement and concrete industries, it has recently attracted attention as an alternative material for solving environmental problems related to water and wastewater contamination. This implies the potential of this new material as an innovative means for wastewater treatment, as these environmentally friendly materials have attractive advantages such as low cost, high efficiency, ease of production and easily scalable characteristics. GP has a three-dimensional mesh structure that provides GP with high porosity and multiple mesopores that increase adsorption capacity by providing more open binding sites to pollutants and impurities on the surface. Table 6 shows some examples described in the literature on the use of GP as an adsorbent, the pollutants contained in them in the form of adsorbates, and some results of adsorption tests.

Table 6.

Examples of geopolymers (GPs) used as adsorbents for water and wastewater treatment.

Table 6 presents selected examples from the literature on the use of geopolymers as adsorbents for water and wastewater treatment, the contaminants studied, and the reported adsorption performances.

7. Activated Carbon

ACs are non-graphitic carbonaceous materials characterized by exceptionally high surface area and a well-developed microporous structure. Their extensive porosity and large number of active adsorption sites make ACs one of the most widely applied adsorbents in environmental remediation. Activated carbons are extensively used in the food, beverage, cosmetic, pharmaceutical, and chemical industries for the removal, separation, and recovery of trace contaminants and dissolved organic compounds [126,127,128].

Growing interest in sustainable and low-cost sorbents has stimulated research into renewable precursors sourced locally from waste biomass or industrial by-products. The production of activated carbon generally involves two major steps: carbonization and activation. Carbonization consists of controlled pyrolysis of carbon-rich materials such as bituminous coal, coconut shells, bones, sawdust, or agricultural residues, resulting in the formation of a carbonaceous char. Activation—either physical (steam/CO2) or chemical (e.g., KOH, ZnCl2, H3PO4)—enhances the surface area and develops a hierarchical pore structure essential for high adsorption performance [129,130].