Abstract

Construction 4.0 refers to the integration of automation, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things (IoT) in the construction industry, which has changed traditional construction practices. MSc courses play a crucial role in developing the next generation of leaders within the construction industry by equipping graduates of these courses with advanced technical, managerial, and strategic skills, including the arrival of Construction 4.0. As future professionals and construction industry leaders, it is necessary to identify the current level of awareness and understanding of Construction 4.0 amongst master’s level students. As such, this paper studies these areas to help identify the gaps in education and training requirements—essential for matching academic programs with industry needs. Through the use of a survey-based approach with 112 MSc students on various Construction Management courses, a series of revealing results were obtained. The results presented herein indicate that there is a shared definition of what constitutes Construction 4.0 amongst engineering management students. However, while they are relatively aware of Construction 4.0 technologies, they do not differentiate strongly between Industry 4.0 and Construction 4.0. Therein, they are ambivalent as to the role of Education 4.0 in improving this situation. Key to this is the requirement to keep up with industry needs. The lack of application of Construction 4.0 means students lack the necessary ‘practical skills’ to implement innovations on real construction sites. Students advocated for more hands-on training, industry-linked projects, and guest lectures within the curriculum, alongside developing the essential skills of critical thinking and problem-solving. Changes in the curricula are suggested, achievable through readily existing 4.0 Frameworks.

1. Introduction

“Construction 4.0 is a comprehensive transformation with the use of the latest advanced digital technology (ADT) to improve the efficiency of the construction industry, as well as making it sustainable and increasing the level of automation.”[1]

The construction industry is often described as a slow starter when it comes to the adoption of new technologies, and it is usually considered tardy in the innovative cycle [2]. This can, in part, be explained by the nature of the industry, which has many actors and is complicated by supply chains and large-scale, risky projects.

Construction 4.0, with a greater emphasis on digitalization and automation, has an impact on the construction industry, enabling change for the better. Whilst it is likely still evolving and not yet fully understood, it has the capacity to revolutionize the processes of designing, constructing, and managing buildings, infrastructure, and the surrounding environment.

Terms like Construction 4.0 and Building 4.0 are often used interchangeably without understanding the subtleties of each. Therein, it is the term 4.0 that is most critical as it relates to the 4th Industrial Revolution. As such, one interpretation of Construction 4.0 considers the incorporation of information technology, data, and automation into the construction process to increase efficiency and output. This includes such techniques as digital twins, robotics and automation (e.g., 3D printing), unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), off-site and modular construction techniques, and virtual and augmented reality technologies. The more restricted view on Building 4.0 is that it is mostly seen as a fusion of the built environment with information and communication technology that promises significant efficiencies in improving cost, time, and quality of building works [3].

Construction 4.0 encompasses a range of social, economic, and environmental sustainability aspects. Therein, the integration of digital technologies like BIM, AI, and IoT is used to create a more environmentally, economically, and socially sustainable construction industry. As such, it cannot be ignored or created in a vacuum. It needs to deal with multiple organizations and legal and cultural reforms to help develop (and utilize) digital technology and automation in the sphere of the construction industry [4]. In addition, better consideration of the way it is dovetailed with education, not least at the postgraduate level, should be investigated. Moreover, the effect of these technologies on the overall built environment and the importance of ensuring longevity and resilience should be identified [5]. Lastly, it should reinforce the idea of tackling construction problems using an all-inclusive approach for Society, Environment, Governance, and Technology (SEGT) and economic growth [6].

The previous research on Construction 4.0 has focused on its narrow definition, but the literature is adopting a shift towards a broader definition and understanding of what constitutes Construction 4.0—to include sustainability issues, including climate change (i.e., achieving Net-Zero by 2050), urbanization, shortage of skills, and productivity stagnation [7]. Extending the scope of the literature concerning Construction 4.0 is required, delineating its probable impacts for the construction industry, the built environment and society more broadly in the 21st century. As such, an integrated approach is required to address challenges in engineering and engineering education, which plays a crucial underpinning role [6]. Therefore, providing this appropriately at the earliest stages of education prepares engineering graduates for complex, real-world challenges, both now and in the future. Education 4.0 provides such a route whereby teaching and learning frameworks are adopted to better prepare students for the Fourth Industrial Revolution [8].

Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that Education 4.0 and Construction 4.0 are, and should be, closely linked. They both attract digital skills and seek to increase efficiency, innovation, and learning by utilizing Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), Automation, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), and Building Information Modelling (BIM). Beyond education, Construction 4.0 requires a digitally competent workforce, which is enabled by smart learning environments by using augmented reality (AR)- and virtual reality (VR)-based simulations, AI-driven personalization and training to enrich their 4.0 journey. Integrating digital tools in construction education offers students, who ultimately become practicing engineers, the opportunity to utilize real-time data analysis, robotics and sustainable construction practices that are making the industry landscape change and staying competitive. Education 4.0 guarantees that upcoming professionals are suitably skilled, with problem-solving abilities and broader digital skills to thrive appropriately in the technology-driven construction sector, creating within (and being innovative for) a more efficient, sustainable, safe, and resilient built environment.

As such, master’s level students need to have knowledge and awareness of Construction 4.0 as part of Education 4.0, so they transition into this new emerging industry that has been, and will continue to be, greatly influenced by digitization and smart technology. Current innovations found in Construction 4.0 (outlined previously) should be integral to Education 4.0. To use these technologies appropriately, students must develop a solid conceptual foundation of Knowledge, Skills and Behaviors (KSBs) aligned with the industry’s requirements, better preparing them for local and global challenges [9].

Education under 4.0 is more technology-driven and personalized, which means that students acquire knowledge that is competency-based and relevant to current industry needs. It encourages hands-on training in virtual simulation, smart classrooms, and AI-based learning systems so that students can experience real-time use of project management techniques, digital collaborations, and automation in construction.

Master’s level construction management students should therefore be learning within Education 4.0 frameworks, which fully integrate Construction 4.0 principles to become industry-ready professionals with critical thinking, problem-solving, and digital fluency. Lack of adequate awareness and understanding may deprive the students of the ability to adapt to modern construction methodologies, which may jeopardize their employability and future ability to innovate. Fostering a holistic approach in student learning builds awareness, understanding, and application of these technological advances, which is key to the success of Construction 4.0.

This forms the basis of this current research, where we begin to identify, by way of a survey of MSc-level engineering students, how far we have come in this realm and what more needs to be done to fully integrate Construction 4.0 as part of Education 4.0. The research builds on a previous publication by the authors, which presented a systematic review of the application of Construction 4.0 in developing countries [10]. The next paper in this series will focus on the outcomes of the same survey on construction professionals in developing countries. Thereby, the links between Education 4.0 and the awareness, understanding, and application of Construction 4.0 on a journey from master’s level students to working adults can be investigated.

1.1. Research Questions

This research paper focuses on the following overarching research questions:

- How aware are master’s level students regarding the impact of Construction 4.0 technologies on sustainability and efficiency within the construction industry?

- What educational strategies can be implemented in master’s programs to enhance awareness and understanding of Construction 4.0 among students?

- What role do collaborative projects and internships play in shaping master’s level students’ understanding of Construction 4.0 technologies?

This study offers a thorough examination of the literature on Construction 4.0, facilitating a collective comprehension of the fundamental ideas, technology, and applications linked to this new paradigm.

1.2. Research Objectives

The objectives of the study are as follows:

- To identify if there is a universal definition of Construction 4.0 shared amongst MSc students.

- To identify the awareness, understanding and application of Construction 4.0 of MSc students within MSc modules.

- To identify the MSc students’ understanding of Education 4.0

As future professionals and construction industry leaders, it is necessary to ask master’s level students about their awareness and understanding of Construction 4.0. By identifying gaps in education and training requirements, requirements for matching academic programs with industry needs can be identified. This brings forward the need for updating curricula that cover skills required for adapting to an emerging Construction 4.0 landscape.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definitions, Conceptualizations, and Embracement of Construction 4.0

The phrase ‘Construction 4.0’ was introduced in 2016 by the consulting company Ronald Berger GMBH in a paper entitled Digitization in the Construction Industry: Building Europe’s Road to ‘Construction 4.0’ [5]. The analysis highlighted numerous crucial technologies capable of revolutionizing the construction sector (Table 1). These technologies have the potential to augment efficiency, decrease expenses, and promote cooperation and communication among stakeholders in the construction sector [6]. Building 4.0 relates to the application of Construction 4.0 to the design, execution, and management of buildings [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Note that building 4.0 is not just a ‘conventional building’ but one enhanced by the technological advancements [13]. Construction 4.0 can be seen as the entire process, and Building 4.0 is just the product (building). Innovative tech like CP, digitalization, and human-robot collaboration will facilitate a paradigm shift in design, planning, construction, use and repurposing of buildings, infrastructure, and cities [14].

Table 1.

Awareness and understanding of Construction 4.0 from the literature.

Even though Construction 4.0 is a relatively new concept, it has its roots in the 1960s and 1970s. Back then, the construction industry began using computer-aided design (CAD) and other digital technologies, along with new manufacturing ideas. However, significant progress was made in the 1990s with the coming of BIM, which was widely recognized in the industry throughout the 2000s [15]. The process of creating a model of a construction or infrastructure project that can be shared with the parties involved. The model covers all aspects of the project in complete detail. This includes design, building, maintenance, and operation. This allowed stakeholders to work together more effectively, reducing errors and costs. Construction is the sole sector that makes use of BIM, which was examined long before the inception of terms like “Industry 4.0”, “4th Industrial Revolution” (4IR), or “Construction 4.0” [16].

Even though Construction 4.0 is becoming popular, there is still no agreement on its definition. It is often linked with Industry 4.0 and associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution. It does include a new era of technological development resulting from the combination of digital, physical, and biological systems. This includes the use of advanced technology, such as artificial intelligence, automated machinery, robots, and the Internet of Things, which is being used to transform our living and working environment, primarily in the current manufacturing sector. Industry 4.0 was first presented in Germany in 2011 as a component of the nation’s high-tech strategy and has since achieved international acclaim as a framework for digital transformation across several sectors, including automation and healthcare. At the core of Industry 4.0 is the amalgamation of versatile technologies that allow the creation of integrated systems, whereby the cumulative benefits exceed the singular contributions of each element.

2.2. Student Engagement and Technological Preparedness (SEGT) for Construction 4.0

Given the Construction 4.0 imperative, student engagement and technological preparedness (SEGT) constitute exciting areas to explore, especially among master’s level students entering the field as leaders and technical staff. Certain technologies, such as automation, robotics, Building Information Modelling (BIM), and artificial intelligence, that make up Construction 4.0 have been a pointed issue in the current literature since construction has been taught in educational institutions, instilling a deep level of knowledge of construction trends. However, there has been little research as to how well-prepared students are in terms of awareness and preparedness to apply these technologies in real-world construction scenarios [17].

Many studies point to the growing reliance on high-tech digital devices in the construction industry. However, research on how effective a university course program is in imparting these skills is very limited. Within the SEGT framework, we understand how students can learn technologically advanced concepts through their degree programs, along with the degree programs that shape students to function effectively within a Construction 4.0-mediated environment. It is crucial to understand this gap because a lack of exposure to Construction 4.0 technologies could lead to a workforce unprepared to tackle technological challenges [18].

The study carried out by [19] sought to investigate the perceptions, preparedness, and transitions of policymakers, facilitators (lecturers), and beneficiaries (students) on education 4.0 in the ASEAN region within the globalization context of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR). This investigation employed a research design that combined qualitative and quantitative methods. The quantitative data utilized a 1–5 Likert Scale, which consisted of the following: (1) Not Ready, (2) Ready, (3) Not Sure, (4) Quite Ready, and (5) Extremely Ready. The open-ended questions allowed quantification of a qualitative method to explore the depth of respondents’ views about Education 4.0 [19]. The reliability index of the test items measured at 0.744 and was therefore ranked as acceptable. Respondents consisted of educational policymakers, facilitators, and recipients to elucidate their shared definitions of each construct (i.e., knowledge, industry, and humanity). This research highlighted the significance of understanding and documenting the interconnected elements of the educational ecosystem present in higher education (HE) throughout the ASEAN area [19]. Respondents therein exhibited a high level of personal preparation for Education 4.0; nonetheless, concerns were expressed about the financial and management preparedness of schools across the area. Table 1 shows the various technologies used in Construction 4.0 and identifies from the literature both their importance and aspects relevant to the awareness and understanding of master’s level students.

The idea of student involvement and improved engagement is a puzzling issue for educators and researchers. There are constant disputes over its exact nature and complexity. At the same time, various experts critique the theoretical and operational frameworks of other players in the empirical studies for their adequacy and coverage. This research also applies to educational technology and its use in higher education institutions. There is no denying the important role that technology plays in education and the ability to engage students [20].

2.3. Students’ Perception Towards Construction 4.0

Due to digitization, the construction sector is required to develop a techno-savvy labor force. The technology of Industry 4.0 is, to some extent, already present in the workplace and has guidelines (although not direct boundedness). Integrating Industry 4.0 with Education 4.0 in the pedagogy of construction engineering is equally important for the future of the construction industry and creates awareness for newly developed technologies, not least automation [21]. The construction sector has been slower to adopt Industry 4.0, and likewise, educators have been slower to embrace Education 4.0. In addition, the body of research knowledge in this field is in its infancy, especially the comparative awareness between industry and academics on Construction 4.0. The construction industry has been slower to adopt Industry 4.0 due to a combination of high costs, fragmented industry structure, resistance to change, and a significant skills and knowledge gap [21]. Key barriers therein include high upfront development costs, a lack of long-term planning, insufficient training for the workforce, financial constraints, and resistance from employees and management [21]. The barriers to education are less clear-cut.

Zabidin [74] undertook an investigation into the cognizance and impediments regarding the application of Industry 4.0 and Education 4.0 in the minds of industry and academia professionals through a construction engineering viewpoint. A standardized questionnaire was created and disseminated among public building projects and public universities across Peninsular Malaysia [74].

Data for this research was obtained via in-person meetings and the dissemination of online surveys [74]. Results from the two distinct groups of respondents, differing in age range and academic credentials, provide both analogous and divergent findings for awareness and knowledge relative to their professional roles [74]. Nevertheless, both unique responders have identified financial limitations as the primary obstacle to the implementation of Industry 4.0 and Education 4.0. The research reveals the present awareness, knowledge, and obstacles among stakeholders in construction engineering, and these insights might inform future action plans to further the adoption of Industry 4.0 in the area. This study’s findings indicated that age and educational qualification have almost the same relation to knowledge and awareness. This study also identified that both these variables (age, qualification) of respondents found that financial constraint is the biggest barrier for the adoption of Industry 4.0 and construction 4.0 [74].

The Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) sector is poised to enter a new industrial era. A primary objective of business 4.0 is the digitalization of Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) business [75]. Building Information Modelling (BIM) advances this objective by establishing a digital repository of information about building structures. Building Information Modelling (BIM) represents a pivotal focus in contemporary building development, so understanding this technology is crucial throughout higher education [75]. A range of motivating and instructional initiatives were implemented to enhance awareness of BIM technology among students at the Faculty of Civil Engineering at the Technical University of Košice in Slovakia. A questionnaire survey was conducted to assess the awareness level of graduates from 2017 to 2019 [75]. The survey investigated how effective motivational and instructional initiatives are in schools and identified that educational institutions are key to the BIM technologies adoption journey. This curriculum’s development improves knowledge and awareness of the students for the easier uptake of BIM technologies [75]. Struková et al. [76] stated that humanity is on the brink of a technology revolution that will drastically alter our modes of living, working, and communicating. The magnitude and intricacy of this transition will be as crucial to humanity as any prior technological development [76,77].

2.4. Students’ Perception Towards Education 4.0

“Education 4.0 is about evolving with the times, and for higher education institutions, this means understanding what is required of their future graduates”[72]

Research by [78] analyzed students’ perceptions of the integration of social media networks into the educational process at seven institutions in the northern area of Jordan. To attain this objective, the authors used a descriptive survey methodology, including one dichotomous question, one open-ended question, and a questionnaire with fifteen items on a 5-point Likert scale [78]. Results revealed that 82.41% of 762 student respondents exhibited favorable views regarding the incorporation of social media into the educational process and identified their favorite social media apps [78].

Research by [79] illustrated the development of (and need for) an educational system in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (IR 4.0). It was found that IR 4.0 initiated a transformation in schooling. Education 4.0 prepares students for the challenges of Industry 4.0 by increasing student motivation, developing individual skills and improving learning outcomes [80].

Education 4.0 is a prominent term among educators today and is both appropriate and necessary. Ref. [80] delineates the nine trends of Education 4.0, the preferences of 21st-century learners, and the competencies required for 21st-century educators, these are as follows [80]:

- Learning can be anytime, anywhere.

- Students have a choice in determining how they want to learn.

- Learning is personalized to individual students.

- Students will be exposed to more project-based learning.

- Students will be exposed to more hands-on learning through field experience.

- Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

- Students will be assessed on real-time projects.

- Students’ opinions will help shape the design and help update the curriculum.

- Students will become more independent in their own learning.

The research also presents students’ comments about their experiences in an Education 4.0 environment. The findings of this study stated that Education 4.0 emphasizes the integration of new technologies like IoT, microcontrollers, and sensors to enhance teaching through visualization and simulation [80]. Tools like TinkerCad (https://www.tinkercad.com/ (accessed on 5 November 2025)) enable programming and visualizations on platforms such as Arduino and Raspberry Pi. Blockchain technology plays a significant role in education by securing and digitizing educational data, certificates, and results [5,80,81,82,83,84,85,86].

2.5. Research Gap

The research gap for this current study is based on insufficient studies done to explore the level of awareness and understanding of master’s level students about the scope and application of domains within Construction 4.0 technologies within the construction industry. Although there is extensive research on the deployment of Industry 4.0 in the construction sector, a more granular view of this emphasis is observed, mainly with the absence of studies focused on the educational part, including the readiness of future construction professionals. This study attempts to address this gap by first studying master’s students’ understanding and awareness related to Construction 4.0 to identify educational needs and opportunities to incorporate these emerging technologies into academic curricula as part of Education 4.0.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

In this research, a quantitative survey-based research design was conducted to explore the awareness and understanding of the technologies of Construction 4.0 among master-level students studying in construction-related programs. The research approach is wholly appropriate to the research questions posed. Although it should be noted that the best way to fully assess a student’s awareness and understanding of any subject area, using a pedagogical approach, is through both subjective and objective methods that garner evidence over time. This is beyond the scope of this current research, which seeks to identify, at a baseline level, what the current level of awareness and understanding is, in order that appropriate changes to the curriculum can be put in place to improve the situation.

The aim was to first determine the amount of familiarity with the root technologies like Building Information Modelling (BIM), the Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI) and other upcoming digital tools. In particular, the study focuses on engagement levels of the students, their understanding of the advantages and drawbacks of these changes, and their readiness to integrate these innovations into the real world.

3.2. Sampling Method

The stratified random sampling process was used to ensure the sampling represents the target population provided by various universities that offer construction management programs. The strata were categorized based on education, terminal year, and whether they had exposure to technological tools in the construction sector or not. Such a stratification approach reflected a wide gamut of experiences and opinions on various matters about Construction 4.0 in the sample. The general objective was to achieve a sound allocation that would appropriately and at the same time, provide quality results representative of the target population.

3.3. Data Collection

The information was obtained using a questionnaire that was distributed to master’s level students within the construction field. The questionnaire contained 53 questions, of which 52 were closed-ended, and 1 was open-ended. The questionnaire was validated using face and content validity (i.e., expert review was used to check questions for clarity and to identify if all aspects are appropriately covered).

The questions are related to the knowledge, awareness, and understanding of the students about Construction 4.0. The survey was carried out online to maximize the number of participants. The responses clarified the present situation of the knowledge of students; therefore, they identified the learning gaps and evaluated the willingness of these students to learn about new technologies within Construction 4.0. This study utilized snowball sampling techniques to increase response rates. In addition, this questionnaire utilizes Likert’s five-point scale (i.e., from 1 to 5) to develop a deeper understanding of the findings. The questionnaire is split into seven distinct parts (referred to herein as categories), as detailed below.

Questions 1 to 9 were used to identify the demographics of the respondents to the questionnaire to determine if these were influential to the responses given. The questions posed and the results obtained can be seen in Section 4.1

Questions 10 to 12 were used to identify if the respondents had any awareness of Industry 4.0 prior to completing the questionnaire and, if so, how well they understood its concepts. Students were given five choices from unaware (1 on the Likert scale) to highly aware (5 on the Likert scale). The questions posed and the results obtained can be seen in Section 4.2.

Questions 13 to 22 are designed to identify if there is a widely accepted understanding of the definition and practices of Construction 4.0. Students were given five choices from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The questions posed and the results obtained can be seen in Section 4.3.

Questions 23 to 25 focused on the awareness, understanding, and exposure of the MSc students to Construction 4.0, focusing down from the general construction industry to the individual MSc students. Students were given five choices from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The questions posed and the results obtained can be seen in Section 4.4.

Questions 26 to 35 focused on the awareness, understanding, and exposure of the MSc students (from developing countries) to Construction 4.0, focusing down from the general construction industry to the individual MSc students. Students were given five choices from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The results can be seen in Section 4.5.

Questions 36 to 38 focused on improving awareness, understanding, and exposure of MSc students to Construction 4.0. Students were given five choices from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The questions posed and the results obtained can be seen in Section 4.6.

Questions 39 to 52 focused on the status and future role of Education 4.0 for MSc students. Students were given five choices from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The questions posed and the results obtained can be seen in Section 4.7.

3.4. Data Analysis

Analysis of the data collected by the methods of descriptive statistics allowed the extraction of key insights. Means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions were used to describe responses and characterize the understanding and awareness of the students of Construction 4.0 technology. Inferential methods were also used, especially the Chi-squared tests, to check the correlation between some of the variables, like the academic background and knowledge level. In addition, factor analysis was used to identify latent factors that could be affecting perceptions and interaction with Construction 4.0 by students, hence providing a more detailed analysis of the results.

4. Results

For many exploratory or internal studies, >100 responses provide a substantial and appropriate base to draw conclusions from. The target population was provided by various universities that offer construction management programs. Hence, the responses are conclusive to these MSc students and any previous institutions they would have attended. As such, the margin of error is low for this specific cohort of students. However, the results may not be fully representative of the UK or, more generally, globally. More data would be needed from other universities around the world to substantiate this with greater certainty.

The results are split into seven categories according to the key theme (as previously mentioned in Section 3).

4.1. Demographics

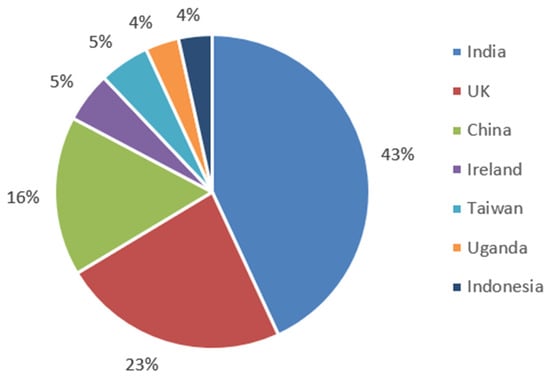

Nine questions related to respondent demographics were posed as shown below—the results of these can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of home countries (n = 112).

- Where is your home country?

- In what country have you completed your master’s degree?

- Age (respondent selects age group for ease of data collection).

- How many years of total work experience do you have in the construction industry (including internship, training, or professional roles)?

- What best describes your professional role or function?

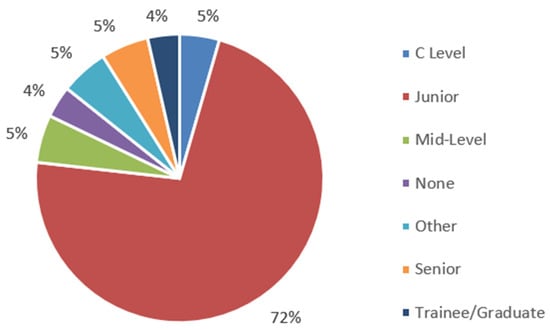

- What is your current level of position?

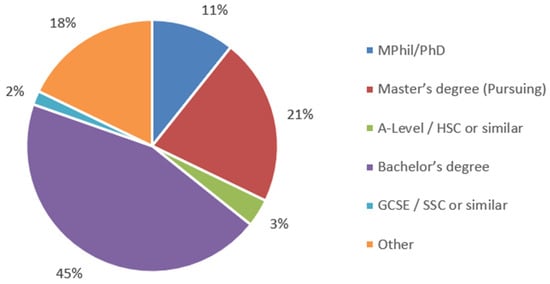

- What is your highest educational qualification?

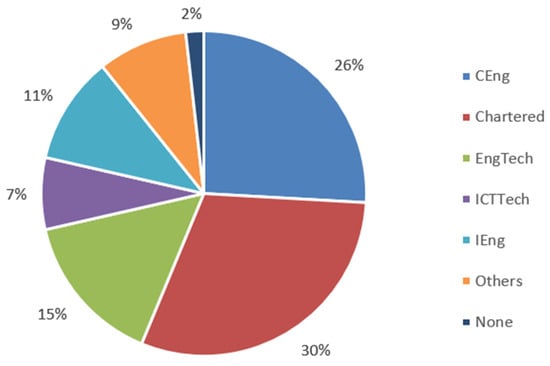

- Do you have any professional qualifications?

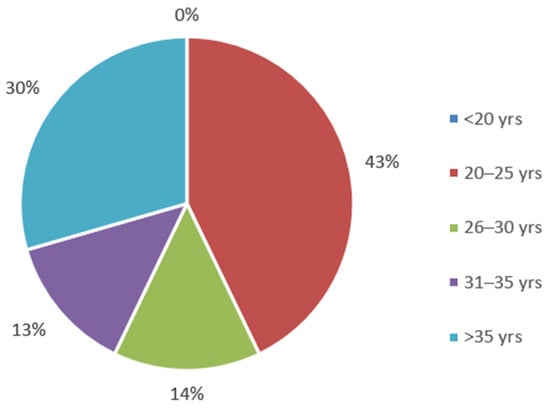

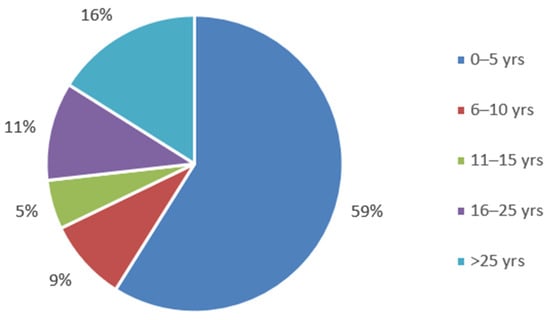

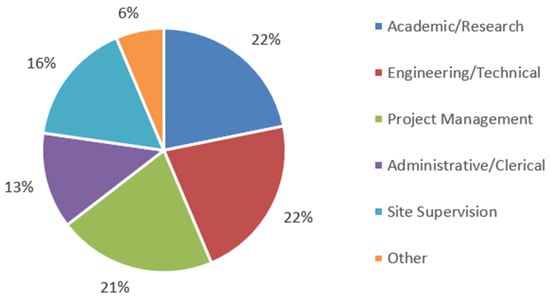

Figure 1 shows 112 responses to Q1. Therein, the top three countries represented were India (43%), the UK (23%), and China (16%). Moreover, 68% of the respondents had completed their master’s in India and 32% in the UK. Figure 2 shows that 43% of the students were between 20 and 25 years of age, 25% of the students were between 26 and 35 years of age, and 30% were over 35 years of age. Figure 3 shows that the students predominantly had 0 to 5 years of experience (59%), accompanied by an even spread of professional roles (Figure 4), 72% of which were at a junior level (Figure 5) and 76% of which had gained bachelor’s degrees and were pursuing an MSc (Figure 6). Over half of the respondents (56%) were of chartered status—reflecting significant expertise in the field of engineering (Figure 7).

Figure 2.

Breakdown of age (n = 112).

Figure 3.

Breakdown of years of work experience (n = 112).

Figure 4.

Breakdown of professional role or function (n = 112).

Figure 5.

Breakdown of current level or position (n = 112).

Figure 6.

Breakdown of highest educational certification (n = 112).

Figure 7.

Breakdown of professional certification (n = 112).

4.2. Awareness of Industry 4.0

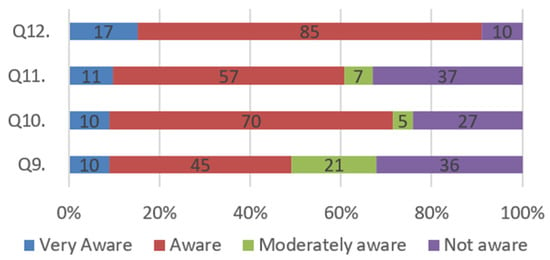

Figure 8 shows the results of Q9 to Q12 listed below:

Figure 8.

MSc student awareness of Industry 4.0 (n = 112).

- 9.

- Before this questionnaire, how aware were you of Industry 4.0?

- 10.

- How aware are you currently regarding Industry 4.0?

- 11.

- How aware are you currently of the concepts of Industry 4.0?

- 12.

- How aware are you currently of the application of Industry 4.0?

The above figure depicts the awareness of MSc students regarding Industry 4.0 before and after completing the survey. It shows how students’ awareness levels evolved, with responses indicating varying degrees of familiarity with Industry 4.0 concepts and their applications. The figure highlights a general increase in awareness after the survey from 49% to 91% (i.e., from 55 to 102 respondents either aware or very aware), suggesting an educational impact of engaging with the topic through this survey.

4.3. A Universal Definition of Construction 4.0

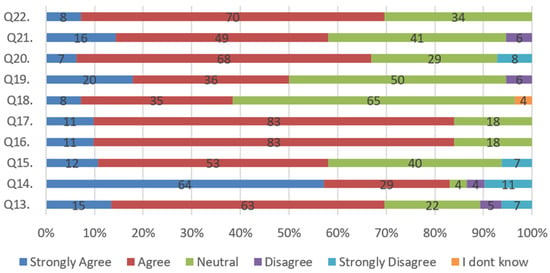

Figure 9 shows the results of Q13 to Q22 listed below:

Figure 9.

Results of a universal definition of construction 4.0 (n = 112).

- 13.

- Construction 4.0 is universally understood as the integration of digital technologies into construction practices.

- 14.

- There is a clear and widely accepted definition of Construction 4.0 within the construction industry in the country in which I reside.

- 15.

- Construction 4.0 is synonymous with Industry 4.0 but tailored for the construction sector.

- 16.

- Construction 4.0 focuses on improving productivity and efficiency through technological advancements.

- 17.

- The term Construction 4.0 encompasses a wide range of technologies, from robotics to artificial intelligence.

- 18.

- There is a significant difference between Industry 4.0 and Construction 4.0.

- 19.

- Construction 4.0 aims to address specific challenges unique to the construction industry.

- 20.

- Construction 4.0 is primarily about digital transformation in construction.

- 21.

- The definition of Construction 4.0 enables sustainable and eco-friendly practices.

- 22.

- Construction 4.0 is defined by its ability to integrate data and analytics into construction processes.

The above figure depicts the universal definition of Construction 4.0 as understood by MSc students. It shows students’ views on whether Construction 4.0 is synonymous with Industry 4.0, its focus on improving productivity, efficiency, and sustainability through technological advancements like automation and AI, and whether it addresses specific challenges unique to the construction industry. The highest level of agreement was found for Q16 and Q17 at 84% (either agreeing or strongly agreeing). The lowest level of agreement was found for Q18 at 38% (either agreeing or strongly agreeing).

4.4. Awareness, Understanding, and Exposure of MSc Students to Construction 4.0

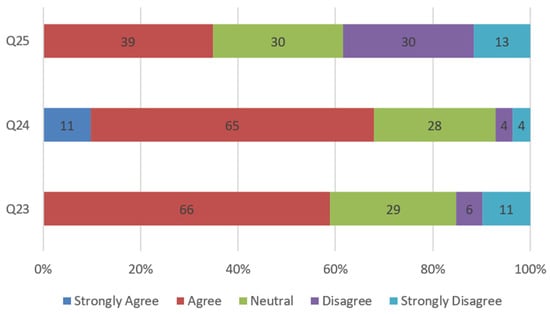

Figure 10 shows the results of Q23 to Q25 listed below:

Figure 10.

Awareness, understanding, and exposure of MSc students to Construction 4.0 (n = 112).

- 23.

- I am aware of how Construction 4.0 technologies (e.g., BIM, IoT, AI, automation) contribute to improving sustainability in the construction industry.

- 24.

- I understand how Construction 4.0 technologies enhance efficiency in construction processes, such as reducing costs, minimizing waste and improving project timelines.

- 25.

- I have received adequate exposure (through coursework, seminars, or self-learning) to understand the role of Construction 4.0 technologies in promoting sustainable construction practices.

The above figure illustrates the awareness, understanding, and exposure of MSc students to Construction 4.0 technologies. It highlights students’ recognition of how these technologies, such as BIM, IoT, and AI, contribute to improving sustainability and efficiency in construction. The figure shows that 68% of respondents were either aware or very aware of the purpose of Construction 4.0 (Q24), and yet only 35% of respondents were either aware or very aware of what these technologies were (Q25).

4.5. Awareness, Understanding, and Exposure of MSc Students (From Developing Countries) to Construction 4.0

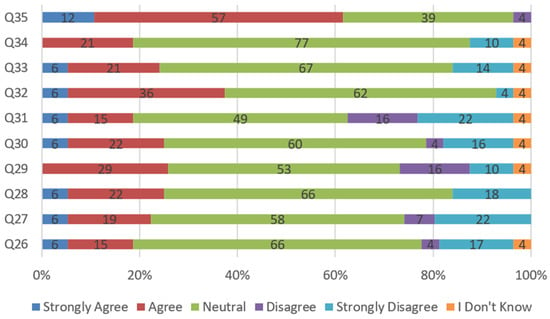

Figure 11 shows the results of Q26 to Q35 listed below:

Figure 11.

Awareness, understanding, and exposure of MSc students (from developing countries) to Construction 4.0 (n = 112).

- 26.

- There is a high level of understanding of Construction 4.0 among construction professionals in developing countries.

- 27.

- Home-grown construction companies in developing countries are actively investing in Construction 4.0 technologies.

- 28.

- Construction 4.0 is increasingly adopted in developing countries, especially by home-grown construction companies aiming to boost efficiency and innovation.

- 29.

- Educational institutions in developing countries offer courses related to Construction 4.0.

- 30.

- The governments of developing countries support the adoption of Construction 4.0.

- 31.

- The construction workforce in developing countries is skilled in using Construction 4.0 technologies.

- 32.

- Construction projects in developing countries are increasingly using BIM.

- 33.

- Robotics and automation are being adopted by construction companies in developing countries.

- 34.

- Digital twins are used in major construction projects in developing countries.

- 35.

- Construction firms in developing countries face challenges in adopting Construction 4.0 technologies.

The above figure depicts the awareness, understanding, and exposure of MSc students from developing countries to Construction 4.0. It highlights the increasing adoption of technologies such as BIM, robotics, automation, and digital twins in construction projects within these regions. The figure shows that the awareness, understanding and exposure of MSc students to Construction 4.0 is low (Q26), with 19% of respondents rating this as agree or strongly agree. In addition, 62% of respondents (Q35) either agreed or strongly agreed that developing countries face significant challenges in adopting the required technologies for Construction 4.0.

4.6. Improving Awareness, Understanding, and Exposure of MSc Students to Construction 4.0

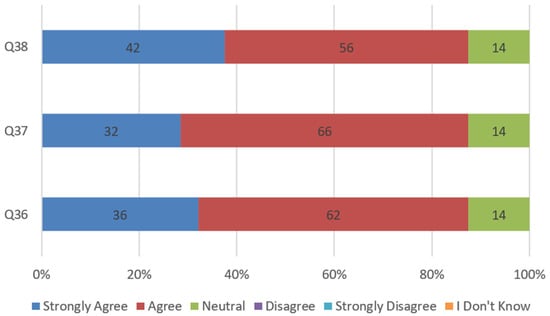

Figure 12 shows the results from Q36 to Q38 listed below:

Figure 12.

Improving awareness, understanding and exposure of MSc students to Construction 4.0.

- 36.

- Integrating hands-on training (e.g., workshops, lab sessions, or simulations) on Construction 4.0 technologies would improve my understanding of their application in the construction industry.

- 37.

- Including industry expert lectures and guest sessions on Construction 4.0 technologies in the curriculum would enhance my awareness of their impact on sustainability and efficiency.

- 38.

- Project-based learning and case studies focusing on real-world applications of Construction 4.0 technologies would help me better understand their role in modern construction practices.

The above figure depicts the improvement of MSc students’ awareness, understanding, and exposure to Construction 4.0. It highlights the importance of integrating hands-on training, industry expert lectures, and project-based learning to enhance students’ practical understanding of Construction 4.0 technologies. The figure emphasizes how such initiatives can better prepare students for real-world applications in modern construction practices. In all three questions, 88% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the suggested methods for improving awareness, understanding and exposure of MSc students to Construction 4.0. No student disagreed or strongly disagreed, showing a strong argument for implementing all three aspects.

4.7. The Role of Education 4.0 for MSc Students

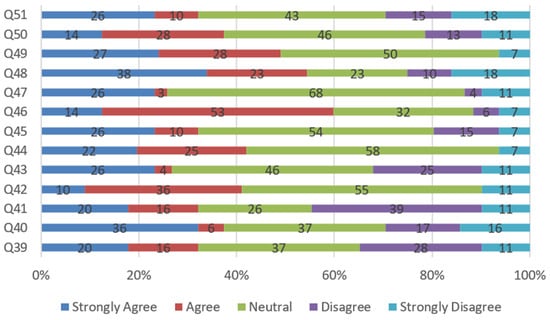

Figure 13 shows the results from Q39 to Q51 listed below:

Figure 13.

The role of Education 4.0 for MSc students (n = 112).

- 39.

- Education 4.0 enhances student engagement and motivation in learning.

- 40.

- The integration of AI, VR, and IoT in education improves the overall learning experience.

- 41.

- Personalized learning through Education 4.0 helps cater to individual students’ needs effectively.

- 42.

- Teachers are well-prepared and trained to implement Education 4.0 technologies in classrooms.

- 43.

- Education 4.0 fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills among students.

- 44.

- The transition from traditional learning to digital learning under Education 4.0 is smooth and effective.

- 45.

- Education 4.0 enhances collaboration and teamwork through digital and online platforms.

- 46.

- There are sufficient resources and infrastructure to support the implementation of Education 4.0 in educational institutions.

- 47.

- Education 4.0 promotes lifelong learning and adaptability to future technological advancements.

- 48.

- The use of automation and AI in education may reduce the need for traditional teacher roles.

- 49.

- I am aware of the key principles of Education 4.0, including personalized learning, digital transformation, and industry-aligned curricula.

- 50.

- Technology-driven learning methods (such as AI-based learning platforms, virtual labs, and gamification) play a crucial role in enhancing the effectiveness of Education 4.0.

- 51.

- The integration of real-world industry projects and interdisciplinary learning in Education 4.0 better prepare students for future job markets.

- 52.

- Do you have any general comments about understanding the perspective of Education 4.0?

The above figure illustrates the role of Education 4.0 for MSc students, highlighting various aspects of how this educational framework enhances student learning. It focuses on the integration of AI, VR, and IoT in education, personalized learning strategies, and the impact on critical thinking, collaboration, and future job market preparation. The figure also discusses how Education 4.0 promotes lifelong learning and adaptability, ensuring students are equipped for technological advancements. The results in this section showed lower numbers of respondents either in agreement or strong agreement with the statements given, ranging from a low of 26% for Q47 to 61% for Q46. Interestingly, only 32% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that Education 4.0 enhances student engagement and motivation in learning (Q39). Moreover, only 41% of respondents thought teachers were sufficiently trained with respect to Education 4.0 (Q42).

5. Findings and Further Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were undertaken using JASP (Jeffreys’ Amazing Statistics Program), a free, open-source statistical software developed by the University of Amsterdam https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

5.1. Mean, Standard Deviation, and Cronbach’s Alpha of All Six Categories

Table 2 shows the mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha (α) of categories considered. Therein, α was used to provide a measure of internal consistency over these categories. Three categories (i.e., Categories 4, 5, and 6) have excellent internal consistency (i.e., α > 0.9), two categories (i.e., 1 and 2) have ‘questionable’ internal consistency (i.e., α > 0.6), although it borders ‘Acceptable’ (i.e., α > 0.7), whilst Category 3 has poor internal consistency (i.e., α > 0.5)

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha results.

The highest mean value at 4.14 is for Category 5, showing students highly advocate the need for improving awareness, understanding, and exposure to Construction 4.0. The lowest mean at 2.53 is for a universal definition of Construction 4.0—this is not surprising given that there is no single, universally agreed-upon definition for this within the academic and professional literature. It is well-known to be an evolving term therein. What is surprising is that the mean for Category 6 is the second lowest at 2.62, showing that students are ambivalent as to the role Education 4.0 plays—this is surprising given that both are deeply linked, with one providing the necessary skills and adaptable teaching methods for the other. As such, further exploration of the role of Education 4.0 will be undertaken in Section 5.2 and Section 5.3.

5.2. Further Analysis of Education 4.0 (Category 6)

The data shown in Section 4. were used to show how participants assessed Education 4.0 in terms of three dimensions:

- The impacts Education 4.0 brings to student engagement and motivation,

- The integration of the latest technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI), virtual reality (VR),

- The Internet of Things (IoT) and the effectiveness of personalized learning strategies

The data provides a central tendency, as well as dispersion measures that allow the formation of an overall evaluation of the opinion and attitude towards the process of modernizing education in modern times.

In Dimension 1, Education 4.0 can be used to increase student participatory activities in learning; the item received a mean score of 3.16, meaning that it falls above the midpoint and hence, on average, there is agreement with the state. However, the standard deviation of 1.12 that comes with it suggests a significant variation, pointing to the fact that it is not the same among all participants. The range between the minimum of one and the maximum of five considers the widest possible selection of stances; though a small proportion of respondents strongly disagree with the statement, another proportion of respondents also strongly agree, showing the variation in opinion. Interquartile range, with the values between 3 and 4, implies that 50 percent of the responses can be situated between moderate agreement and strong agreement, which demonstrates polarization within the middle category of respondents in terms of the levels of response.

The second dimension considered the adoption of AI, VR, and IoT to enhance learning processes and generated an average score of 2.95, which is slightly lower than the neutral two. This 1.36 standard deviation indicates a large variation: some participants strongly agree, whereas other participants simply disagree or are undifferentiated. The score ranges of 1 and 5 reveal that there is polarization; the lower quartile of 2 means that a significant portion do not positively perceive these technologies, and the 75th percentile of 4 means that the upper half of the respondents do take a more positive posture, albeit with a range of opinions. This variability could be due to the different degrees of exposure to such tools enjoyed by the participants, such that some of them lack familiarity or show no evidence of the educational value of the tool.

The third dimension was used to determine the effectiveness of personalized learning within the framework of Education 4.0. An average value of 3.27 indicates an overall quite positive perception in general, with most of the responses accepting the statement that personalized learning is a positive attribute of Education 4.0. With the standard deviation of 1.14, there is limited variability, and thus, even though several participants think there is a clearly perceived value in personalized learning, some still seem to be neutral or not convinced enough about its effects. A range of 1 through 5 points indicates a high dispersion of views. Remarkably, the first quartile of 3 is evidence that 25% of respondents scored this statement at or lower than the neutral median, implying that a significant proportion of individuals do not seem so confident in the usefulness of personalized learning. The increase in the positive asset 75th percentile score of 4 shows that those members who have more favorable attitudes towards Education 4.0 perceive its advantages with more certainty, meaning that personalized learning can be of particular importance to the people who have greater experience with the technologies. Altogether, the score distribution seems to show that the concept of personalized learning is commonly viewed as the encouraging aspect of Education 4.0, but the attitude hinges on personal experiences and expectations at the same time.

In summary, all the descriptive statistics make up an ambivalent but overwhelmingly positive evaluation of Education 4.0. There is widespread confidence that Education 4.0 can increase levels of student engagement and facilitate personal learning, with less confidence around the incorporation of newer technologies in the form of AI, VR, and IoT. The large scale of the scores (1–5) implies the necessity to pay attention to different points of view and experiences in assessing the potential of Education 4.0. The varying perspectives might be explained by such factors as exposure to different models of education, knowledge of technological progress, and individual preferences for education. Therefore, the tendency towards the progressive development of educational practice, Education 4.0, may be viewed as a positive movement overall; however, its execution and success will have to be improved and directed towards accommodating different needs and expectations of students and teachers.

5.3. Bartlett, Chi-Square, and KMO Tests

The sample adequacy and suitability of data related to Education 4.0 were validated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO), Bartlett, and Chi-squared test. The Bartlett test showed a p-value of <0.01, which is considered ‘very good’ (i.e., highly significant). This is consistent with a Chi-squared value of <0.01, which suggests that the data is unlikely to occur by chance. Hence, the sample can be considered adequate [87].

The KMO of 0.637 (above a threshold of 0.6) means it can be considered as acceptable for factor analysis, which will be undertaken in Section 5.3.

5.4. Factor Analysis

Table 3 focuses on the factor analysis used to identify latent factors influencing students’ perceptions of Education 4.0. The applied rotation used is Promax. The analysis reveals three primary factors:

Table 3.

Factor analysis.

- Factor 1: student engagement and technological integration;

- Factor 2: institutional and teacher readiness;

- Factor 3: barriers and resistance to change.

These factors provide insights into how different variables, such as the integration of AI, VR, IoT, and personalized learning, relate to students’ experiences with Education 4.0. The results help highlight areas for improvement in educational practices, particularly in terms of preparing students for a technology-driven workforce.

Factor 1 shows the strong correlation between student engagement and the integration of modern technologies in learning, while Factor 2 emphasizes institutional readiness and teacher preparedness. Factor 3 identifies challenges related to resistance to change, particularly in the context of resource limitations and the adaptation of traditional teaching methods. Factor analysis is a very popular statistical method used to uncover patterns and clusters in large data sets and simplify the analysis by showing how bits of data relate to each other as part of a latent factor term (usually using the observed variables in equations or regressions). The current investigation resulted in three latent factors, which organized the data collected through the survey, considering its main dimensions of Education 4.0.

Individual factors have a set of variables within them that are all characterized by a similar focus, with the respective factor loaders explaining which factors each variable carries on to the specified latent dimensions. The factor-loading table provides the raw correlations of the variables and the factors, hence explaining relations between different educational factors and ideas of Education 4.0. The findings of the factor analysis cannot be ignored in understanding the specifics that responders relate to Education 4.0, technological integration and readiness to such changes.

The initially identified factor proves to be the most substantial, with consistently high loadings on many variables, especially those relevant to issues of student engagement, personalization of learning, technology-rich teaching, and inclusion of industry-related projects. The specified factor has an impressive positive loading to Education 4.0 as the proportion of student engagement (0.956), individualized learning (0.997), and technologically oriented teaching (1.043) and the implementation of practical work in the field with the industry (1.082). These values can be interpreted as a very high correlation between Factor 1, on the one hand, and, on the other, the general benefits of Education 4.0—especially those associated with student engagement and digital and technological innovations in the classroom. This element puts into focus the major theme of modernization of education, noting that education 4.0 introduces more interactive, personalized and technology-driven learning platforms. Additionally, it highlights the importance of workplace, industry-related experiences and actual and real practice, a factor which has been touted as crucial in making students ready and suitable in the new labor markets. The high values achieved for Factor 1 may indicate the common opinion that places Education 4.0 in a positive aspect in terms of engagement activity among students, the development of critical thinking, and the improvement of learning processes by means of technology. The conclusion indicates a strong interest among respondents in new teaching techniques that Education 4.0 advocates and justifies the statements that a significant part of the participants agree with the integration of digital tools, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and meaningful relationships with industry into educational practice.

The elements of Factor 1 are described by substantive loadings, which indicate that these elements were perceived to be central in the realization of the potential of Education 4.0 towards the actualization of an educational practice. Advanced technologies and real-life applications also have high loadings, indicating that respondents consider integration of advanced technologies and real-life related problem-solving exposure as an evolutionary and essential restructuring of the learning environment. Additionally, the exceptional position assigned to industry projects and practical learning indicates a stronger tendency to align education systems to the current challenge and market demands, marking a deeper desire to have educational institutions prepare students for the workforce market in the future, which is characterized by technological innovation and multidisciplinary cooperation.

Factor 2 is not as strong as Factor 1; however, it represents a significant aspect of the data and makes a difference in the moderate weightings due to the high rate of involvement of most educators who are ready to apply Education 4.0 technologies. A value of −0.209 is a moderate negative loading related to the variable ‘teachers are well-prepared to implement Education 4.0 technologies’, implying the perceived values of teacher preparation are inversely proportional to other educational factors. The positive loadings are also associated with education, stimulating critical thinking (0.991) and personalized learning (0.521); however, the presence of variable responses to the preparedness of teachers to the influence of Education 4.0 and critical thinking shows doubts about the real ability of the teaching body to adopt and implement Education 4.0 changes efficiently. Factor 2, therefore, describes the concerns of institutional readiness, especially in relation to the capacity to stimulate and to capitalize Education 4.0 technologies among the teachers. The lower level of factor loadings in the construct also indicates that although the factor related to it is taken into consideration, readiness is a secondary aspect of the spectrum of perceptions of Education 4.0 due to the additive reliance on an optimistic candidacy provided by Factor 1.

The negative coefficients given on the variable of teacher’s preparedness in Factor 2 show a denoted skepticism or reservation towards the understanding of the ability of teachers to institute crucial transformation practices in the classroom. These findings form an outstanding barrier towards the application of Education 4.0 effectively, based on the premise that the preparedness of the instructors is recognized to be one of the favored conditions before the successful educational transformation can take place. The ambivalence on Factor 2 further demonstrates a contradiction: those answering respondents admit to the pedagogical usefulness of critical thinking and individualized learning, but at the same time express a similar amount of uncertainty in relation to the practical possibility of achieving those goals, considering the limited training and scarce resources that teachers could theoretically use.

With respect to Factor 3, a more subtle configuration is observed. Although the loadings of this dimension are relatively smaller and less in relation to those attributed to Factors 1 and 2, the negative coefficients given to teachers’ preparedness (−0.579) and critical thinking (−0.694) indicate that this dimension is characterized by resistance to change or structural barriers within the educational apparatus. In the case of technology-driven methods, the slightly positive coefficient of loading (0.047) shows that the respondents are open to what Education 4.0 has to offer, but there are considerable barriers on their way to embracing this fully. Generally, the pattern of factor loading indicates that, despite the high rhetorical support of technology and innovation, the empirical uptake of technology in general comes with challenges, such as a lack of resources, a lack of teacher training, and resistance by the establishment regarding innovative approaches.

Hence, Factor 3 proves that, despite the rhetorical convergence in the educational community with the goals of Education 4.0, its actual implementation is hindered by resource problems and shortcomings of professional training, as well as the high persistence of pedagogical traditions. The use of negative loadings on teachers’ preparedness and critical thinking speaks to the fact that the identified obstacles are especially keen in such spheres as educator training and institutional support, implying that work on these aspects should be deemed essential to long-term success and at-scale applicability of Education 4.0 efforts.

6. Discussion

6.1. General Overview of Findings

MSc students have awareness, understanding, and exposure to Construction 4.0 technologies and Education 4.0. Of critical importance, which this paper has looked at in part, is students’ preparedness for the technological changes in the construction sector and how Education 4.0 can benefit them in this context.

According to the descriptive analysis done herein, the respondents are somewhat aware of essential technologies like BIM, IoT, UAVs (drones), AI, 3D printing, etc., but their exposure to these technologies has been mostly limited to theoretical knowledge or demonstrations. A good number of students are aware of BIM and IoT, but do not have any hands-on knowledge of real-life applications such as smart site management or energy monitoring. According to the study, the students clearly understand the theory; however, there is a lack of training when it comes to practical functionality and application. More training, like case studies and workshops, will help to bridge the gap.

Engaging the students’ personalized learning was shown to have a high correlation with student engagement and teachers integrating technology, albeit at a moderate level. There was shown to be an apprehension about the educational program and whether the inclusion of Education 4.0 is teacher- or institution-ready. Structural and attitudinal barriers, such as resistance to change and limited resources, could be additional reasons why the adoption of new teaching strategies and technologies is not yet mainstreamed. The implications for Education 4.0 are further discussed in Section 6.2.

6.2. Implications for Education 4.0

6.2.1. Why Does Education Not Keep Up with Industry Demands?

It is well-reported within the literature that education does not always keep up with industry [88,89]. The question is why? When assessing what inhibits higher education institutions from addressing industry-driven change in Irish Construction Management Programs, O’Neil et al. [90] suggested 78 factors under five core themes of resources (23), organizational (13), human (11), administrative (11), and external influences (20). Therein, the leading factors are related to resources or a lack thereof.

6.2.2. What Changes Are Needed in Curricula?

The current paper highlights a mismatch between the hypothetical promise of Education 4.0 and the relative organizational readiness of education systems and teachers to adopt the technologies needed. This also suggests that a change in curricula is required. Educational strategies can be implemented in master’s programs to enhance awareness and understanding of Construction 4.0 among students. The question is what changes in curricula are required? It is suggested that curriculum development should become more proactive, innovative, and focus on competency development that includes technical and non-technical aspects [91]. Therein, the role of the educator should evolve from one of being a knowledge transmitter to more of a facilitator—one that increasingly uses remote learning for theoretical-based knowledge and only uses face-to-face for improving practical skills-based learning [11,91]. Chacón [92] advocates for a Construction 4.0-rich complementary learning pathway. Ref. [92] goes on to suggest that STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, and math) activities should be used to foster creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. Therein, collaborative projects and internships will play an important part in shaping master’s level students’ understanding of Construction 4.0 technologies [93].

6.2.3. How to Develop Frameworks for the Introduction of Construction 4.0?

A framework for the introduction of Construction 4.0 is hugely important because it provides a structured, holistic approach to a complex digital and organizational transformation. The question is, how could this be developed? The World Economic Forum proposed the Education 4.0 framework in 2023 [91], which emphasized a reorientation of education systems towards more holistic learning outcomes. The taxonomy provided therein consists of a comprehensive set of aptitudes (i.e., abstract, transferable aspects of learning) organized into a tree structure.

Elragal and Habibipour [94] contributed further to this by operationalizing the abstract Education 4.0 framework into something that was tangible at the course level. The authors commented on the need for longitudinal studies to investigate how redesigned courses influence student outcomes over time.

6.3. Further Considerations

Conventional education with a focus on theory and passive learning will need to change to a more practical style of education that more readily embraces 4.0 technologies and 4.0 teaching environments. In other words, through the implementation of smart classrooms and virtual simulations. Education 4.0, in a construction-focused perspective, could be as simple as augmented reality (AR) to showcase different construction designs from the classroom or using IoT (Internet of Things) to simulate monitoring the project site, or BIM to showcase current, future and historical buildings [84]. Students would need to engage with technologies that are currently building the industry and ensuring successful project outcomes. Education 4.0 should also allow students to acquire crucial soft skills, for instance, leadership, communication, and teamwork skills, which are also important in the construction sector. It has become essential to work with different teams on various platforms as projects become more complex and multifaceted. Education 4.0 should equip students with the ability to operate modern technologies and be trained in leadership in a hyper-connected digital and collaborative work environment [95,96].

6.4. Limitations of Work

The findings of this study can be considered fully representative of the students on various construction management courses. Whilst it might be inferred that this could be representative of the national and international situation, it cannot and should not be concluded as such. This should not be considered as a limitation but more as a starting point towards achieving this aim. Research should be undertaken at other academic institutions to avoid bias by using a significantly larger dataset. In addition, it would be worth investigating what the current awareness, understanding, and exposure are within the industry and what their current needs are. This is part of a follow-up study that will try to match industry needs with education requirements.

7. Conclusions

Future graduates are to work in the context of high-tech innovations; thus, students should have a thorough understanding of such cutting-edge technologies as Building Information Modelling (BIM), Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and digital twins—to name a few. Even though these technologies are quite common knowledge among students, they lack experience with them. The empirical evidence displays an apparent preparedness gap in the readiness of students to implement the use of such technologies in real construction environments, hence showing a great need for change.

This study investigated the awareness, understanding, and application of Construction 4.0 amongst 112 MSc students on various construction management courses. The results presented herein indicate that there is a shared definition of what constitutes Construction 4.0 amongst engineering management students in their home countries. However, while they are relatively aware of Construction 4.0 technologies, they do not differentiate strongly between Industry 4.0 and Construction 4.0. Therein, they are ambivalent as to the role of Education 4.0 in improving this situation. Key to this is the requirement to keep up with industry needs. The lack of application of Construction 4.0 means students lack the necessary ‘practical skills’ to implement innovations on real construction sites. Students advocated for more hands-on training, industry-linked projects, and guest lectures within the curriculum, alongside developing the essential skills of critical thinking and problem-solving. Changes in the curricula are suggested, achievable through readily existing 4.0 frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V.J. and D.V.L.H.; methodology, S.V.J.; validation, S.V.J.; formal analysis, S.V.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.V.J.; writing, S.V.J.; review and editing, D.V.L.H. and R.J.D.; visualization S.V.J. and D.V.L.H.; supervision, D.V.L.H. and R.J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

S.V.J. received the financial support of the Department of Social Welfare, Government of Maharashtra, India. D.V.L.H. received the financial support of the UK EPSRC under grant EP/J017698/1 (Transforming the Engineering of Cities to Deliver Societal and Planetary Wellbeing, known as Liveable Cities) and EP/P002021 (From Citizen to Co-innovator, from City Council to Facilitator: Integrating Urban Systems to Provide Better Outcomes for People, known as Urban Living Birmingham).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Committee at the University of Birmingham (protocol code ERN_4165-Apr2025 and approved on 4 October 2025). All survey distribution and data storage were undertaken according to the approved application.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

S.V.J. gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the State Government of Maharashtra given to him during his doctoral studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Lau, S.E.; Aminudin, E.; Zakaria, R.; Saar, C.C.; Roslan, A.F.; Abd Hamid, Z.; Zain, M.Z.; Maaz, Z.N.; Ahamad, A.H. Talent as a spearhead of Construction 4.0 transformation: Analysis of their challenges. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1200, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.J.; Oyekan, J.; Stergioulas, L.; Griffin, D. Utilising Industry 4.0 on the construction site: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyika, J.; Chui, M.; Miremadi, M.; Bughin, J.; George, K.; Willmott, P.; Dewhurst, M. A Future that Works: AI, Automation, Employment, and Productivity; McKinsey & Company: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- LForcael, E.; Ferrari, I.; Opazo-Vega, A.; Pulido-Arcas, J.A. Construction 4.0: A literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, D.; Liu, Z.; Osmani, M.; Demian, P. Construction 4.0, Industry 4.0, and Building Information Modelling (BIM) for sustainable building development within the smart city. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonbeck, P.; Lofsjogard, M.; Ansell, A. Quantitative review of construction 4.0 technology presence in construction project research. Buildings 2020, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statsenko, L.; Samaraweera, A.; Bakhshi, J.; Chileshe, N. Construction 4.0 technologies and applications: A systematic literature review of trends and potential areas for development. Constr. Innov. 2023, 23, 961–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, N.; Bled, A.; Bourgault, M.; Cousin, N.; Danjou, C.; Pellerin, R.; Roland, T. Construction 4.0, a survey of research trends. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2020, 25, 416–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, O.; Papp, I.; Szabó, R.Z. Construction 4.0 organizational level challenges and solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Nadeem, A. Towards digitizing the construction industry: State of the art of construction 4.0. In Proceedings of the International Structural Engineering and Construction Conference 2019, Chicago, IL, USA, 20 May 2019; Volume 10, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón, R. Designing construction 4.0 activities for AEC classrooms. Buildings 2021, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osunsanmi, T.O.; Aigbavboa, C.; Oke, A. Construction 4.0: The future of the construction industry in South Africa. Int. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2018, 12, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar, A.; Delhi, V.S. Construction 4.0, what we know and where we are headed? J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 526–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B. Building information modelling framework: A research and delivery foundation for industry stakeholders. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrowshahi, F.; Arayici, Y. Roadmap for implementation of BIM in the UK construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2012, 19, 610–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S. Building information modelling (BIM): Trends, benefits, risks, and challenges for the AEC industry. Leadersh. Manag. Eng. 2011, 11, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Koskela, L.; Dave, B.A.; Owen, R. Interaction of lean and building information modelling in construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, T. The Future of Construction Automation: Technological Disruption and the Upcoming Ubiquity of Robotics. Autom. Constr. 2015, 59, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B.; Sher, W.; Williams, A. Measuring BIM performance: Benefits and challenges. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2012, 8, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Barak, R. Impact of three-dimensional parametric modelling of buildings on productivity in structural engineering practice. Autom. Constr. 2008, 17, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovska, M.; Klosova, D.; Strukova, Z. Impact of Industry 4.0 platform on the formation of construction 4.0 concept: A literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begić, H.; Galić, M. A Systematic Review of Construction 4.0 in the Context of the BIM 4.0 Premise. Buildings 2021, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, G.G.; Satyro, W.C.; Bonilla, S.H.; Contador, J.C.; Barbosa, A.P.; de Paula Monken, S.F.; Martens, M.L.; Fragomeni, M.A. Construction 4.0, Industry 4.0 enabling technologies applied to improve workplace safety in construction. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e280101220280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boton, C.; Rivest, L.; Ghnaya, O.; Chouchen, M. What is at the Root of Construction 4.0, A systematic review of the recent research effort. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 2331–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Soto, B.; Agustí-Juan, I.; Joss, S.; Hunhevicz, J. Implications of Construction 4.0 to the workforce and organizational structures. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osunsanmi, T.O.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Emmanuel Oke, A.; Liphadzi, M. Appraisal of stakeholders’ willingness to adopt construction 4.0 technologies for construction projects. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2020, 10, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafei, H.; Radzi, A.R.; Algahtany, M.; Rahman, R.A. Construction 4.0 technologies and decision-making: A systematic review and gap analysis. Buildings 2022, 12, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunde, N.A.; Gento, A.M.; Okorie, V.N.; Oyewo, O.W.; Mewomo, M.C.; Awodele, I.A. Construction 4.0 technologies in a developing economy: Awareness, adoption readiness and challenges. Front. Eng. Built Environ. 2023, 3, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, M. Construction 4.0, Advanced Technology, Tools and Materials for the Digital Transformation of the Construction Industry; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-La Rivera, F.; Mora-Serrano, J.; Valero, I.; Oñate, E. Methodological-technological framework for construction 4.0. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jazzar, M.; Schranz, C.; Urban, H.; Nassereddine, H. Integrating construction 4.0 technologies: A four-layer implementation plan. Front. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 671408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamak, P.; Aital, P.; Daftardar, A. A comprehensive overview of Construction 4.0 technologies and their implementation in the construction industry. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Gao, S. Construction 4.0 technology and lean construction ambidexterity capability in China’s construction industry: A sociotechnical systems perspective. Constr. Innov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Shukla, V.; Islam, N.; Manghat, S. Construction industry 4.0 and sustainability: An enabling framework. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekan, A.; Clinton, A.; Fayomi, O.S.; James, O. Lean thinking and industrial 4.0 approach to achieving construction 4.0 for industrialisation and technological development. Buildings 2020, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murguia, D.; Soetanto, R.; Szczygiel, M.; Goodier, C.I.; Kavuri, A. Construction 4.0 implementation for performance improvement: An innovation management perspective. Constr. Innov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafei, H.; Rahman, R.A.; Lee, Y.S. Evaluating construction 4.0 technologies in enhancing safety and health: Case study of a national strategic plan. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2025, 23, 1211–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]