Abstract

Green innovation holds significant importance for achieving sustainable development goals. Artificial intelligence has emerged as the primary force behind a new wave of technological and industrial transformation. Using data on Chinese A-share listed manufacturing firms from 2012 to 2023, this study examines the influence of AI policy on corporate green innovation. A chain mediation model is used to identify and test the specific pathway through which this influence operates. The results reveal three findings: First, AI policy has a significantly positive influence on corporate green innovation. Second, industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity serve as chain mediators, playing the role of transmitting the effect of AI policy to corporate green innovation. Third, AI policy more effectively stimulates green innovation in specific contexts, particularly among SMEs, non-SOEs, high-tech industries, and competitive sectors. This study deepens our understanding of how AI policy can promote corporate green innovation, providing important insights for advancing the coordinated development of green and intelligent manufacturing.

1. Introduction

In response to the urgent challenge of climate change, major global economies are significantly overhauling their development strategies. China has also come to deeply recognize that its previous extensive development model is no longer sustainable. Fundamental adjustments must be made to actively pursue an innovation-driven development strategy, transforming traditional low-cost development advantages into core competitiveness built on innovation. The Fourth Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China emphasized that economic development efforts should prioritize the real economy and adhere to the principles of intelligent, green, and integrated growth. It calls for accelerating the construction of a manufacturing powerhouse, a quality powerhouse, a space powerhouse, a transportation powerhouse, and a cyber powerhouse; maintaining a suitable share of manufacturing; and establishing a modern industrial system with advanced manufacturing at its core. As a global manufacturing leader, China has accelerated industrial restructuring in recent years through policy initiatives, such as “Made in China 2025,” to promote energy savings and pollution reduction. However, data show that China’s progress in the green transition of manufacturing has fluctuated downward since 2013, reflecting technical barriers and a lack of momentum in shifting from extensive to intensive growth [1]. Addressing how to achieve both qualitative and quantitative improvements in green technological innovation within manufacturing companies has become an urgent societal and industrial priority. The integration of digital technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, across various sectors has partially replaced traditional production methods, reduced innovation costs for companies, and optimized manufacturing processes. This has emerged as a new driver of green innovation and of enhancing its efficiency in manufacturing firms [2]. To address technical bottlenecks in artificial intelligence, promote its industrialization, and facilitate the high-end, intelligent, and green transformation of traditional industries, China’s Ministry of Science and Technology issued the “Guidelines for Establishing National New Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones” in 2019. These guidelines, often abbreviated as the “AI Pilot Zones”, led to the establishment of 18 such zones across the country. These pilot zones have advanced AI infrastructure development, offering new opportunities to enhance corporate green innovation [3].

Research relevant to this paper’s theme can be broadly classified into two types. Factors influencing corporate green innovation form the first category. Research has found that, in terms of internal corporate support, corporate governance [4], executive traits [5,6], environmental awareness among senior managers [7], top management teams’ environmental attention and education [8], and background and technical proficiency [9] significantly impact corporate green innovation. In terms of external collaborative interactions, the relationships established between enterprises and their partners influence their green innovation [10]. These include downstream customer demands [11], the formation of technology alliances between enterprises and universities or research institutions [12], the involvement of public research institutions in green R&D [13], and industry association affiliations [14], which significantly influence corporate green innovation. In terms of the macro-policy environment, environmental regulation [15], green credit [16], and government environmental concerns [17] significantly influence corporate green innovation. Second, from an internal governance perspective, research indicates that AI fosters corporate green innovation through enhanced human capital accumulation, improved organizational management efficiency, and higher-quality information disclosure [18] by boosting production efficiency and decision-making quality [19] and by bolstering corporate green capabilities through mitigated financing constraints and lowered agency costs [20]. From an external governance perspective, AI facilitates green innovation in manufacturing firms by optimizing innovation information [21], attracting institutional investors [22], and increasing media attention [23]. Financial analysts reinforce the connection between AI and corporate green innovation through information dissemination and scrutiny [24]. However, academic research on how AI macro-policies translate into corporate green innovation remains insufficient, especially concerning the underlying mechanisms. Therefore, this study delves into how AI policy shapes corporate green innovation, focusing on its underlying mechanisms. This evaluation seeks to bridge the gap between policy implementation and enterprise practice, providing evidence-based insights to support the green transformation of the manufacturing sector.

Cast within a quasi-natural experiment, the creation of AI pilot zones is used to empirically examine the effect of AI policy on corporate green innovation, using microdata from Chinese A-share listed manufacturing firms between 2012 and 2023. This study makes the following marginal contributions. First, a fresh research perspective is offered by examining AI pilot zones and systematically analyzing the role of AI policy in advancing corporate green innovation. It extends research on the economic impacts of such policy pilots, broadens the theoretical framework for corporate green innovation drivers, and offers new directions for corporate sustainability research in the era of digital intelligence. Second, in exploring the mechanism, this study reveals a chain-mediation path in which AI policy fosters industrial agglomeration and enhances knowledge diversity, which in turn promotes corporate green innovation. This clarifies the process through which AI policy facilitates the green transformation of manufacturers, underscoring the vital synergy between agglomeration effects and diverse knowledge pools. Third, regarding policy implications, this study systematically reveals variations in AI policy responses among enterprises based on ownership structure, scale, and industry attributes. These findings not only provide an empirical foundation for governments to enforce differentiated guidance policies and optimize resource allocation based on enterprise characteristics during AI strategic deployment but also offer decision-making references for enhancing policy execution precision and effectiveness.

2. Literature Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. AI Policy and Corporate Green Innovation

AI pilot zones aim to promote the adoption of AI technologies across the economy and integrate them into socioeconomic fabric. Through a series of supportive measures, these pilot zones effectively lower the barriers to enterprises adopting AI technologies [3]. Leveraging AI’s unique enabling value, they significantly foster corporate green innovation [25]. First, AI enhances enterprises’ strategic awareness and timely decision-making capabilities, empowering them to respond more swiftly and effectively to the sustainability imperative. By analyzing vast datasets, AI identifies patterns in operational and resource data to optimize allocation and decision-making [26]. This data-driven approach informs targeted green initiatives and resource allocation, directly improving corporate innovation outcomes. Second, AI technology effectively overcomes information asymmetric barriers, enabling enterprises to acquire high-quality knowledge and information. Within corporate green innovation networks, AI enables real-time, efficient, and low-cost generation and circulation of knowledge, equipping enterprises with accurate market supply intelligence [27,28]. This process enables enterprises to access valuable external information and high-quality knowledge, thereby increasing their reserves of knowledge, information, and technology and driving corporate green innovation [29]. Third, AI streamlines enterprise R&D cycles, expediting the green transformation. AI-driven simulation tools virtually eliminate the time and cost of physical prototyping [30], enabling faster iteration and advancement of environmental technologies. This acceleration drives down costs and enables faster innovation cycles, which promote successful green outcomes [31]. Accordingly, the study tests the hypothesis that:

Hypothesis 1.

AI policy positively influences corporate green innovation.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Industrial Agglomeration

Marshall (1890) [32] proposed that the positive externalities generated by industrial agglomeration primarily stem from three core channels: labor pools, shared intermediate inputs, and knowledge spillovers. As a key vehicle for external policy influencing industrial agglomeration, the establishment of AI pilot zones prioritizes regions rich in scientific and educational resources, possessing solid industrial foundations, well-developed infrastructure, and clear supportive policies. This combination of locational advantages and policy empowerment effectively attracts relevant enterprises and innovation resources to cluster within the pilot zones, further strengthening regional industrial agglomeration and driving corporate green innovation [33]. First, regarding labor pools, establishment of AI pilot zones accelerates the clustering of related industries, thereby fostering specialized labor pools. This not only attracts a dense concentration of high-caliber talent in the AI domain but also propels comprehensive human capital upgrading across the pilot zones, laying a robust intellectual foundation and talent base to underpin enterprises’ eco-innovation. Compared to general labor, highly skilled talent possesses more systematic knowledge reserves [34] and better-aligned skill structures [35]. This enhances enterprises’ green knowledge integration capabilities and the efficiency of green technology absorption and transformation, ultimately achieving a leap in green innovation capacity. Second, regarding shared intermediate inputs, enterprises within AI pilot zones can leverage agglomeration advantages to share infrastructure such as AI computing power platforms, cloud computing platforms, and information service platforms [36]. This centralized resource allocation model alleviates cost constraints on corporate green innovation [37]. Simultaneously, policy-driven clustering of technical consulting, evaluation, and transformation services provides comprehensive intermediary support for corporate green innovation [38], empowering enterprises in this domain. Third, regarding knowledge spillovers, establishing AI pilot zones facilitates technical exchanges and collaborations among enterprises, research institutions, and AI industry associations. This directly reduces firms’ search and contract costs, promotes knowledge and technology flows, and generates knowledge spillover effects [39]. This enables enterprises not only to obtain complementary resources from other companies through R&D collaborations but also to absorb cutting-edge AI knowledge from research institutions and industry associations, thereby enhancing their own intelligence and ultimately driving the output of green innovation achievements [40]. Accordingly, the study tests the hypothesis that:

Hypothesis 2.

Industrial agglomeration mediates the relationship between AI policy and corporate green innovation.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Knowledge Diversity

The knowledge-based theory posits that knowledge serves as the core strategic resource for building competitive advantage and driving innovation [41]. A firm’s knowledge base encompasses all types of knowledge within the organization, including information, technology, and know-how [42]. Knowledge diversity, as an indicator measuring the extent of heterogeneous knowledge elements within an enterprise, reflects the scope of expertise spanning diverse technological fields [43]. Establishing AI pilot zones helps optimize the corporate knowledge ecosystem, enabling enterprises to acquire, absorb, and reorganize knowledge more effectively, thereby driving green innovation. First, regarding knowledge acquisition, AI pilot zones are dedicated to building collaborative innovation mechanisms that involve multiple stakeholders, such as enterprises, universities, and research institutions. This effectively breaks down knowledge barriers and constraints within individual organizations, transforming traditional knowledge-acquisition pathways and models. It creates favorable conditions for enterprises to access and absorb technical knowledge from diverse fields, thereby promoting the diversification of corporate knowledge reserves [44]. This diversified knowledge base supports low-cost, high-frequency knowledge experimentation and iterative pathfinding during green innovation [45], thereby enhancing corporate green innovation capabilities. Second, regarding knowledge absorption, through the development and refinement of knowledge-sharing infrastructure—such as large-scale public service platforms—the AI pilot zone promotes deep application of AI technologies within enterprises. AI technology, with its logical reasoning and autonomous learning capabilities, enhances a corporation’s capacity to absorb knowledge. Enterprises with strong knowledge absorption capabilities can accurately identify and manage valuable information, continuously internalize external knowledge, update and expand their knowledge bases, and drive the effective integration of internal and external knowledge [46]. This enhances corporate knowledge diversity and drives the sustained growth of green innovation activities. Third, regarding knowledge restructuring, as a hub aggregating multi-stakeholder, multi-domain knowledge resources, AI pilot zones significantly enhance a corporation’s capacity to absorb knowledge [47]. Enterprises can leverage the integrative utilization of heterogeneous internal knowledge elements to achieve secondary innovation and value amplification. Furthermore, by employing divergent thinking, they enhance creative outputs in areas such as green product design and process improvement [48]. Accordingly, the study tests the hypothesis that:

Hypothesis 3.

Knowledge diversity mediates the relationship between AI policy and corporate green innovation.

2.4. Chain-Mediated Effect of Industrial Agglomeration and Knowledge Diversity

The above analysis indicates that industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity both acted as mediators for the AI policy’s influence on corporate green innovation. Existing research further reveals that industrial agglomeration provides abundant shared innovation resources for regional innovators, serving as a crucial mechanism for corporate knowledge diversity. Industrial agglomeration enhances the regional mobility of factors such as capital and labor, accelerating the spatial spillover of knowledge and technology, thereby facilitating enterprises’ access to cross-regional heterogeneous knowledge. The capital-intensive R&D infrastructure generated by industrial agglomeration—including a shared pool of highly skilled labor, key laboratories, advanced instruments and equipment, and information service networks—reduces firms’ costs of accessing innovative ideas, thereby promoting the enhancement of corporate knowledge diversity. Accordingly, the study tests the hypothesis that:

Hypothesis 4.

AI policy enhances corporate green innovation through the chain-mediated effect of industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity.

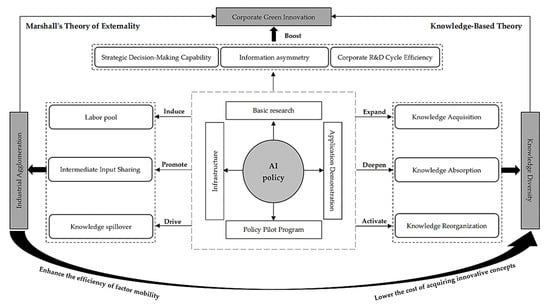

Following the above analysis, the conceptual model diagram for this study is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model Diagram.

3. Results

3.1. Sample and Data

This research analyzes Chinese A-share listed manufacturing enterprises between 2012 and 2023, using a multi-period DID model to assess how AI policy influences corporate green innovation. The sample excludes financial firms, ST/ST*/PT entities, and observations with substantial missing data, yielding 26,024 firm-year observations. Data on green innovation and corporate finance are retrieved from the CNRDS and CSMAR databases.

3.2. Reference Model and Variable Measurement

In August 2019, China’s Ministry of Science and Technology issued the “Guidelines for Establishing National New Generation Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones,” sparking a wave of pilot zone establishment across China. As of 31 December 2021, China had established 18 pilot zones, including 17 prefecture-level cities and above and 1 county. The first batch of pilot zones was established in 2019, including Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Hefei, and Deqing (county); the second batch was established in 2020, including Chongqing, Chengdu, Xi’an, Jinan, Wuhan, and Guangzhou; and the third batch was established in 2021, including Suzhou, Changsha, Zhengzhou, Shenyang, and Harbin.

The impact of AI pilot zones on corporate green innovation is identified using a multi-period DID model, employing their three-batch rollout as a quasi-experiment, specified as follows:

Among these, we measure corporate green innovation (Green), the dependent variable, by the total count of granted green patents. The number of patent grants must undergo rigorous examination across multiple dimensions, including novelty, inventiveness, and utility. Consequently, it serves as a crucial indicator of an organization’s or region’s technological capabilities and R&D levels. Furthermore, granted patents enjoy legal protection, and their quantity more accurately reflects substantive innovation outcomes [49]. The core explanatory variable is Treat Post. As a policy variable, Treat indicates whether city i hosts such a pilot zone in year t. It takes a value of 1 if city i established the pilot zone in year t and 0 otherwise. represents provincial fixed effects; represents the year fixed effect; is the random error term; is the double difference estimator, the primary focus of this paper; and represents the set of control variables affecting corporate green innovation in year t.

To mitigate regression bias, this study controlled for a series of factors potentially influencing corporate green innovation, specifically including: firm size (Size), measured by the natural logarithm of total assets; the proportion of independent directors on the board (Indep); the debt-to-asset ratio (Lev); the ratio of net cash flow from operating activities to total assets (Cashflow); revenue growth rate (Growth), calculated as (current year revenue/previous year revenue − 1); the natural logarithm of the number of board members (Board); and a binary variable (Dual) reflecting leadership structure, valued at 1 when the chairman and chief executive roles are combined and 0 otherwise.

3.3. Mediated Effect Model

We constructed models (2) to (5) to test the mediating effect:

Equations (2) and (3) are models based on Equation (1) that treat the mediating variable as the explained variable. K-diversity is an abbreviation for knowledge diversity and IA is an abbreviation for industrial agglomeration, while the meanings of other variables remain unchanged. To test the chain-mediated effect of “AI policy → industrial agglomeration → knowledge diversity → corporate green innovation,” models (6) to (8) are constructed.

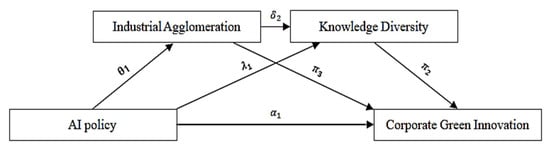

If in Equation (1), Equation (6), and in Equation (7), and , and in Equation (8) are all significant, this indicates that the chain-mediated effect exists whereby AI pilot zones accelerate industrial agglomeration, enhance knowledge diversity, and ultimately promote corporate green innovation. The corresponding functional model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework.

This study employs the metric (provincial industrial value-added/total industrial value-added)/(provincial GDP/total GDP) to measure regional industrial agglomeration levels. Drawing on the work of Li et al. (2024) [50], the International Patent Classification (IPC) codes are used to assess knowledge diversity. China’s IPC coding system comprises five hierarchical levels: Division, Class, Subclass, Group, and Subgroup. Following the approach of Chatterjee & Blocher (1992) [51], this study primarily classifies IPC codes by subclass and employs the entropy method to measure knowledge diversity, using the variable K-diversity. The specific calculation method is presented in Equation (9):

In Equation (9), for an enterprise holding m distinct subclass-level invention patents, represents the proportion of patents in the technical field of subclass-level invention patent i.

4. Empirical Test

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 reveals considerable divergence in corporate green innovation among the listed manufacturers, as evidenced by a range of 0 to 27, a mean of 1.141, and a standard deviation of 3.702.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Baseline Regression

The baseline analysis of the AI policy’s effect on corporate green innovation is reported in Table 2. The initial specification in column (1) includes province and time fixed effects but omits firm-level controls. Even after adding these controls in column (2), the key Treat × Post estimate of 0.589 is still positive and significant at the 1% level. This consistency across models strongly supports the positive impact of AI policy.

Table 2.

Empirical results of the baseline regression.

4.3. Endogeneity Test

4.3.1. Incorporating Reference Variables to Mitigate Selection Bias

Evaluating the AI policy could be subject to bias if regional selection correlates with time-varying confounders, including economic development and the degree of informatization, which also drive corporate green innovation. The baseline model corrects for potential selection bias by interacting with city benchmark factors with the time trend [52]. The specific specification is presented in Equation (10):

The estimates in columns (1) to (3) in Table 3 consistently show that AI policy significantly enhances corporate green innovation at the 1% level. This finding holds true whether the interaction term between city benchmark factors, such as provincial capital and location southeast of the Hu Huanyong Line, and the time trend are included individually or together, as outlined in Equation (10). Thus, the results remain robust when accounting for biases stemming from inherent disparities among urban areas.

Table 3.

Empirical results of the endogeneity analysis.

4.3.2. Instrumental Variable

While the policy pilot program exhibits some degree of exogeneity, pilot city selection is often linked to the local development of AI and could remain susceptible to unobserved factors, resulting in potential selection bias. To address endogeneity issues, this study employs the 1984 landline telephone penetration rate as an instrumental variable [53]. On one hand, the early penetration rate of landline telephones mirrors the baseline status of urban information infrastructure. Urban areas that launched informatization initiatives earlier gained a preliminary edge in digital technologies, making them more likely to be selected as pilot sites and thereby meeting the relevance requirement for this IV. On the other hand, advances in communication technology have led to the replacement of landline telephones with modern digital communication methods. Since this historical data has no direct bearing on firms’ current green innovation, it plausibly satisfies the exclusion restriction for an instrumental variable.

Table 3, columns (4) to (5) report the IV estimation results. First, the p-value (0.000) of the Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic indicates that the hypothesis of inadequate identification of the IVs is dismissed. The corresponding Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F-statistic (33.48) surpasses the 10% significance threshold, verifying no presence of weak instrumentality. Second, in the first stage, the instrument variable coefficient is significantly positive, satisfying the correlation requirement. In the second stage, the coefficient on Treat × Post is positive and significant at the 1% level. This indicates that, after addressing endogeneity concerns, the study’s benchmark conclusions remain valid.

4.3.3. PSM-DID

Although the selection of pilot cities for the “AI Pilot Zones” involves a degree of randomness, this randomness is not entirely arbitrary. Instead, it is based on a set of specific criteria and conditions that comprehensively evaluate multiple factors, such as infrastructure levels, industrial foundations, and economic development status. This selection mechanism may create inherent systematic disparities between pilot areas and their non-pilot counterparts prior to the policy’s rollout, thereby compromising the accurate evaluation of policy impacts. To mitigate selection bias arising from human factors, mitigate or eliminate systematic disparities between the treatment and control groups, and thereby more precisely estimate treatment effects, we adopted Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to match the treatment group with more appropriate control samples. We then conducted a Difference-in-Differences (DID) estimation based on the matched samples. This approach aims to precisely match pilot and non-pilot cities on relevant or observable variables, preventing cities with significant characteristics from being erroneously assigned to the control group. Consequently, this helps reduce estimation inaccuracies attributable to sample selection bias.

This study sets the firm-level characteristics from the year prior to policy implementation (control variables in Model (1)) as covariates. Employing a 0.05 caliper, this research adopts 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching to select matched control samples for the experimental group. Following propensity score matching, a DID test is conducted using Model (1). Column (6) of Table 3 reports the regression results, where the coefficient for the Treat × Post interaction variable remains significantly positive at the 1% confidence level.

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Parallel Trend Test

Adherence to the parallel trend assumption proves crucial for causal inference via the DID method. We leveraged an event study to examine whether the parallel trend held prior to the policy. Since counterfactual scenarios cannot be directly observed, the parallel trend assumption is difficult to verify directly [54]. This test typically entails verifying whether the coefficients for the pre-policy period fail to achieve statistical significance. The absence of significant coefficients across all pre-treatment periods upholds the parallel trend assumption, thereby justifying the adoption of the DID model. To verify the parallel trend assumption, we estimate the model specified in Equation (1). We further construct the dynamic regression model specified in Equation (11) for this purpose.

In Equation (11), Treat × Post is a set of dummy variables. If the city has established AI pilot zone in year t, it takes the value 1; otherwise, it takes the value 0. The notation for other variables retains their definitions from Equation (1). This study focuses on the coefficient in this equation, which reflects the difference in green innovation between treatment and control group firms in year t following the establishment of AI Pilot Zones.

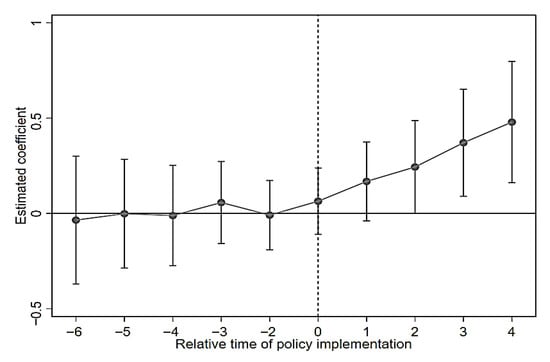

Following Beck et al. (2010) [55], data from the six pre-policy years are consolidated into a single period (−6), with the year immediately preceding the policy’s enactment designated as the reference. The parallel trend test confirms the alignment of green innovation trend before the policy, as all pre-treatment coefficients are insignificant and fluctuate around zero. Thus, the sample meets this condition, as confirmed visually by Figure 3. Additionally, this paper conducted a joint significance test on the prior estimation coefficients. The results indicate that the F-value for the joint significance test is 0.18, with a p-value of 0.971. This demonstrates that the prior estimation coefficients lack joint significance, confirming the robustness of the parallel trend test results.

Figure 3.

Parallel trend test.

4.4.2. Placebo Test

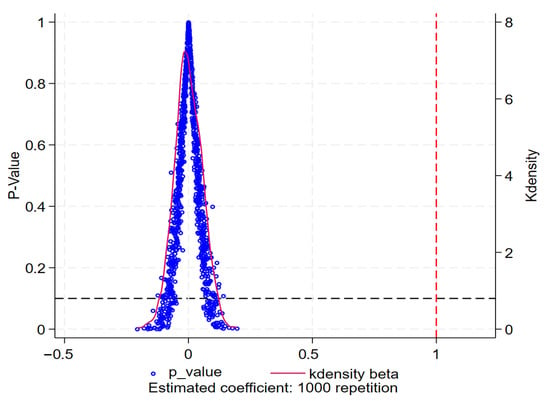

We perform a placebo test to assess the randomness behind the observed effect of AI pilot zones on green innovation. For the placebo test, a “pseudo-policy dummy variable” was constructed by drawing 1000 random values from the baseline regression’s pilot zone distribution. We re-estimated the model in Equation (1) and plotted the distributions of its coefficients and p-values in Figure 4. The average estimated coefficient for the pseudo-policy dummy variable in the corporate green innovation regression is both close to zero and lower than that in the baseline model. The estimated coefficients form a bell-shaped distribution centered on zero, with most being statistically insignificant (p-values > 0.10). The placebo test results confirm the reliability of our findings by ruling out the possibility that the observed effect is driven by random, system-specific factors.

Figure 4.

Placebo test.

4.4.3. Other Robustness Tests

The baseline regression analysis is supplemented with a set of robust tests. First, China launched green financial reform and innovation pilot zones in 2017, covering eight regions across the five provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Guangdong, Guizhou, and Xinjiang. These zones leverage regional advantages by enhancing green financial organizational structures, innovating green financial services systems, refining local green financial standards, and continually strengthening incentives, constraints, and risk prevention mechanisms. These measures create favorable conditions for enterprises to pursue green innovation. To mitigate this concern that corporate green innovation may be confounded by this policy [56], the green finance pilot zone initiative serves as an additional shock in out-of-sample tests. Building on the econometric model (1), we added the didW shock variable for this policy to conduct a re-examination. Second, to gain clearer insights into the policy shock’s effects, we exclude enterprise samples listed after the establishment of AI pilot zones (2019). Third, drawing on Yao et al. (2024) [57], we employ machine learning methods. Based on annual reports and patent data from listed manufacturing enterprises, we follow the steps of data collection, text extraction, AI lexicon formation, and AI indicator construction. We remeasure corporate AI application levels (AI) using the natural logarithm of “total AI word frequency + 1.” The results of the robustness checks are reported in columns (1) to (3) of Table 4. The estimated coefficients for Treat Post and AI were significant, with signs consistent with the expected direction of the effects. This further demonstrates the robustness of the core conclusion that AI policy significantly enhances corporate green innovation.

Table 4.

Results of Other Robustness Tests.

5. Mechanism Analysis and Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1. Testing the Mediating Effect of a Single Factor

5.1.1. The Intermediary Effect of Industrial Agglomeration

From Column (1) of Table 5, we observe that the Treat × Post interaction term is significantly positive at the 5% level, affirming that AI pilot zones facilitate industrial agglomeration. Column (2) further reveals significantly positive coefficients for both industrial agglomeration and Treat × Post, indicating that AI policy boosts corporate green innovation by enhancing regional industrial agglomeration, thus supporting Hypothesis 2.

Table 5.

Mechanism analysis.

5.1.2. Mediating Effect of Knowledge Diversity

The findings in Table 5 support the mediating role of knowledge diversity. Column (3) shows that the AI policy has a significant positive effect on knowledge diversity. Building on this, column (4) reveals that knowledge diversity itself exerts a significant positive influence on green innovation, and the direct effect of AI policy remains significant. This pattern of results confirms that the AI policy partially fosters corporate green innovation by promoting knowledge diversity, thereby validating Hypothesis 3.

A Sobel mediation test is also performed, and Table 6 displays the results for the industrial agglomeration channel.

Table 6.

Sobel Test for Industrial Agglomeration Mediating Effect.

Table 7 shows the Sobel test for knowledge diversity effects. Among the scales mentioned above, Goodman-1 (Aroian) yielded a Z statistic that was significant at the 1% level, indicating robust findings.

Table 7.

Sobel Test for Knowledge Diversity Mediating Effect.

5.2. Testing for Chain-Mediated Effect

The results of testing the chain-mediated effect “AI policy → industrial agglomeration → knowledge diversity → corporate green innovation” are shown in Table 8. Industrial agglomeration shows significance at the 5% level, while knowledge diversity is significant at the 1% level. Hypothesis 4 is thus validated.

Table 8.

Chain-Mediated Effects.

When multiple mediators exist in an influence pathway, the bootstrap method is a crucial technique for testing multi-layered mediating effects. This research elucidates the pathway through which AI policy affects corporate green innovation, the chained mediation of industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity. Bootstrap testing was conducted at a 95% confidence level with 5000 repeated samples, yielding the results presented in Table 9. Findings show that the AI policy promotes corporate green innovation through three distinct mediating channels. For Path 1 (AI policy → industrial agglomeration → corporate green innovation), the mediation effect test for industrial agglomeration shows that the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero, further validating Hypothesis 2. For Path 2 (AI policy → knowledge diversity → corporate green innovation), the mediation effect test for knowledge diversity also shows that the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero, further validating Hypothesis 3. For Path 3 (AI policy → industrial agglomeration → knowledge diversity → corporate green innovation), chain mediation tests for industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity yielded 95% confidence intervals not containing zero, indicating that AI policy promotes corporate green innovation by fostering industrial agglomeration and enhancing knowledge diversity, thereby further validating Hypothesis 4.

Table 9.

Chain Mediation Bootstrap Test.

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

The preceding findings clearly demonstrate that AI policy can significantly enhance corporate green innovation. However, whether this effect varies across enterprise types and industries remains to be verified. To explore the underlying mechanisms, heterogeneity is analyzed across firm size, ownership, industry attributes, and competitiveness.

5.3.1. Enterprise Size

Firm size determines resource, technological, and managerial capabilities, leading to varied impacts of AI policy on green innovation. This study measures enterprise scale by total assets and divides the sample at the median into LSEs and SMEs for group-specific tests. Findings presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 10 demonstrate that, for the SME subsample, the coefficient of the interaction term Treat × Post is positively significant at the 5% significance level. This suggests that AI policy can promote green innovation among SMEs. In contrast, the Treat × Post interaction coefficient fails to reach statistical significance in LSEs, implying that AI policy does not substantially boost green innovation among large enterprises. This indicates that AI policy is more effective at promoting green innovation among SMEs than among LSEs. The reasons lie in the fact that, on one hand, SMEs often face resource constraints in their green innovation processes. Their R&D expenditures and proportion of specialized technical personnel generally lag behind those of large enterprises. This resource gap makes them more reliant on external forces to overcome dual barriers of technology and funding, thereby driving corporate green innovation. Conversely, AI pilot zones, by furnishing intelligent technologies and financial support, assist SMEs in optimizing production processes, elevating management efficiency, and mitigating resource waste and environmental pollution—thereby fostering their eco-innovation. Meanwhile, LSEs boast substantial R&D investments, talent pools, and technological accumulations, coupled with mature innovation systems and steady funding streams. They can conduct R&D in green technology independently, making them less dependent on external policy support and less responsive to such initiatives.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity Analysis: Firm Size and Ownership Structure.

5.3.2. Nature of Property Rights

Heterogeneity in firms’ ownership structures, which gives rise to distinct production technologies and resource allocation efficiencies, may lead to heterogeneous effects of the AI policy on enterprises’ green innovation practices. Based on ownership characteristics, the sample was categorized into SOEs and non-SOEs, with group-specific tests conducted for each category. Findings in columns (3) and (4) of Table 10 reveal that, among non-SOEs, the interaction term Treat × Post yields a significantly positive coefficient at the 5% significance level. This confirms that AI policy exerts a significant positive impact on corporate green innovation among non-SOEs. In contrast, Treat × Post is not significant for SOEs, suggesting the AI policy does not promote their green innovation. This indicates that, compared to SOEs, AI policy proves more effective in promoting green innovation within non-SOEs. The underlying reason is that non-SOEs typically prioritize economic efficiency and market competitiveness. Consequently, they are more motivated to adopt AI to optimize production efficiency, costs, and product quality. Additionally, they possess greater flexibility and initiative, enabling them to autonomously select innovation directions and investment strategies. SOEs, often guided and supported by the government, prioritize public interests and may lack intrinsic motivation for independent innovation. They primarily rely on government policy incentives, financial support, or project collaborations to drive the application and innovation of AI technology within their organizations.

5.3.3. Industry Attributes

Given disparities in technological innovation capabilities and employee quality across enterprises with differing technological attributes, the impact of AI policy on corporate green innovation may exhibit heterogeneity. This study employs the CSRC’s 2012 industry classification standards and the National Key Supported High-Tech Fields of China to define high-tech industries, with the remaining samples categorized as non-high-tech industries for grouped testing. Columns (1) and (2) in Table 11 illustrate that among high-tech enterprises, the Treat × Post interaction term is significantly positive at the 1% significance level. This demonstrates that AI policy acts as a catalyst for green innovation in high-tech enterprises. Among non-high-tech firms, the interaction coefficient Treat Post is not significant, suggesting that AI policy does not significantly promote green innovation. This indicates that AI policy is more effective at advancing green innovation among high-tech enterprises than among non-high-tech enterprises. The reason lies in the fact that high-tech industries, as leaders in national innovation and R&D, excel at conducting high-tech innovation activities and possess extensive experience in innovation and R&D. Their R&D willingness far exceeds that of other industries, making them highly sensitive to the innovative resources and technological conditions brought about by AI policy, thereby more effectively advancing the improvement of their corporate green innovation capabilities. In contrast, non-high-tech industries, constrained by limited innovation experience and insufficient R&D motivation, tend to imitate existing technologies or implement minor improvements. Consequently, AI policy fails to significantly promote green innovation in these sectors.

Table 11.

Heterogeneity Analysis: Industry Attributes and Industry Competitiveness.

5.3.4. Industry Competitiveness

Industry competitiveness may influence corporate green innovation. On one hand, classical Schumpeter theory posits that firms in regulated industries are more likely to innovate, while competitive market structures hinder innovation. On the other hand, the new Schumpeter innovation theory suggests that when innovation gaps among firms within an industry are small, most firms will choose to innovate to escape competition. In such cases, moderately enhanced industry competitiveness can promote corporate innovation [58]. Thus, how AI policy influences corporate green innovation varies across industries depending on the level of competition. This study classifies regulated industries following the 2012 CSRC sector classification system, as detailed below: B07, B08, B09, B10, B11, C25, C31, C32, C36, C37, D44, D45, D46, E48, G53, G54, G55, G56, I63, I64, K70, R85, R86, R87, and R88. All remaining sectors are classified as competitive industries. For enterprises in such industries, the Treat × Post interaction in columns (3) to (4) of Table 11 is statistically discernible at the 5% significance level. This confirms that AI policy significantly fosters green innovation among enterprises in competitive industries. Conversely, for enterprises in regulated industries, this interaction term is not statistically significant, suggesting that AI policy has no discernible impact on green innovation in these sectors. These findings suggest that AI policy is more effective at promoting green innovation in competitive industries than in regulated ones. This occurs because firms in competitive industries face greater competition. To escape this competitive pressure, they urgently leverage AI to enhance their green innovation, thereby strengthening their core competitiveness and market influence within the industry. Enterprises in regulated industries, constrained by monopolistic characteristics, are dominated by the Schumpeter effect. Consequently, AI policy has failed to rapidly enhance corporate green innovation in regulated industries.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Based on 2012–2023 data of Chinese A-share listed manufacturing enterprises, this study constructs a multi-period DID model by taking the establishment of AI pilot zones as a quasi-natural experiment to explore the impact of the policy and its underlying mechanisms on enterprises’ green innovation practices. Key findings are summarized as follows: (1) The beneficial influence of AI policy on enterprises’ green innovation capabilities remains robust after undergoing a series of strict robustness tests. (2) Through mechanism analysis, we find that both industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity act as partial mediators in the relationship between AI policy and corporate green innovation, thereby fostering the advancement of firms’ green innovation performance. Additionally, a chain mediation mechanism is identified: “AI policy → industrial agglomeration → knowledge diversity → corporate green innovation”. (3) Heterogeneity analysis indicates that the policy’s effects vary with firm-specific and industry-related characteristics. Specifically, SMEs and non-SOEs exhibit significant improvements in green innovation. Compared with non-high-tech enterprises and those in regulated industries, high-tech enterprises and firms operating in competitive sectors demonstrate a more pronounced green innovation response to the AI policy.

6.2. Implications

6.2.1. Theoretical Implications

(1) Confirm that AI policy significantly promotes corporate green innovation. This conclusion is supported not only by empirical findings from a sample of Chinese listed companies spanning all industries [3] but also by related research at the technology-application level [24]. Together, these findings demonstrate that artificial intelligence serves a pivotal function in facilitating corporate green innovation. Theoretically, this further underscores that corporate green innovation arises not only from internal technology adoption and accumulation but also from external institutions and environmental factors. Corporate green transformation and sustainable development cannot be achieved without external institutional guidance and incentives. Therefore, strengthening research on external driving mechanisms holds significant academic value and practical implications for deepening our understanding of and promoting corporate green innovation.

(2) Confirm that industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity mediate the relationship between AI policy and corporate green innovation. Although existing research has explored potential pathways through which AI policy may influence corporate green innovation from various perspectives [59], these studies predominantly focus on single pathways or partial mechanisms. They have yet to examine the chain-like transmission process—“AI policy–industrial agglomeration–knowledge diversity–corporate green innovation”—simultaneously within an integrated framework. Therefore, this study incorporates industrial agglomeration from an environmental external perspective and knowledge diversity from a factor reallocation perspective into a unified analytical model. It examines the mediating effects through two distinct channels—“environmental driving” and “factor activation”—and adopts a chained mediation model to systematically uncover the multiple transmission paths via which AI policy affects corporate green innovation.

6.2.2. Policy Implications

(1) Expand the promotion and implementation of AI pilot zones to unleash the driving force of green innovation. Findings show that AI policy facilitates corporate green innovation, enabling enterprises to pursue green development more effectively. First, we should gradually broaden the coverage of AI pilot zones. Building on the experience of existing pilot zones, we should extend them to more regions with industrial foundations to create a policy spillover effect. Second, targeted support for green innovation among enterprises within pilot zones should be strengthened. This includes reducing costs associated with integrating AI technology applications and green innovation through measures such as special subsidies and tax incentives. Concurrently, supporting infrastructure, such as data-sharing platforms and computing facilities, should be enhanced to provide hardware support for enterprises adopting AI technologies for green innovation. Third, a dynamic policy effectiveness evaluation mechanism should be established to monitor enterprise green innovation outputs in real time. This enables timely adjustments to policy priorities, ensuring resources are precisely directed toward areas with higher green innovation efficiency.

(2) Fully leverage the transmission effects of industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity to enhance the impact of policy interventions. Mediation analysis confirms that both industrial agglomeration and knowledge diversity partially mediate the effect of AI policy on manufacturers’ green transformation. Furthermore, a chain-mediated effect exists in the pathway: “AI policy → industrial agglomeration → knowledge diversity → corporate green innovation.” Therefore, the guiding role of AI pilot zones should be fully leveraged to promote high-quality industrial clustering among manufacturing enterprises. Measures such as scientifically planning specialized industrial parks and improving supporting infrastructure should be implemented to reduce spatial transaction costs between enterprises, thereby facilitating the spatial clustering and efficient allocation of green innovation factors. Simultaneously, cross-subject and cross-domain knowledge exchange platforms should be established to incentivize collaborative research and development among enterprises, universities, and research institutions within industrial clusters. This will break down knowledge barriers, enhance knowledge diversity, and accelerate the cross-fertilization and diffusion of AI technologies with knowledge of green innovation. Furthermore, synergistic linkages across all chain-transmission segments should be strengthened. Addressing shortcomings such as insufficient clustering or inefficient conversion, targeted policy support and institutional innovation should ensure that the dividends from establishing AI pilot zones are effectively transformed into endogenous drivers for corporate green innovation.

(3) Enhance policy targeting and implementation adaptability by integrating enterprise types with industry characteristics. The effect of establishing AI pilot zones is more pronounced in non-SOEs and SMEs, with particularly strong incentives for green innovation found in high-tech and competitive sectors. Consequently, policies should prioritize supporting non-SOEs, SMEs, and technology-intensive enterprises in adopting AI technologies to accelerate breakthroughs in core green technologies and deepen the integration of AI with production operations in traditional industries. Concurrently, market access mechanisms should be refined to enhance transparency and fairness, stimulate proactive competition among market participants, and foster a healthy, orderly market ecosystem. Establishing a scientific evaluation system for green innovation, with publicly disclosed results, will strengthen positive competition among enterprises. Furthermore, advocating collaboration amid competition will promote efficient coordination along the industrial chain, from upstream to downstream, across technology, resources, and information. This will cultivate collaborative innovation networks, consolidate developmental effects, and jointly advance the green transformation and industrial upgrading.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This research remains subject to certain limitations and calls for additional exploration and extension in subsequent studies.

(1) Limitations of the Empirical Analysis. Regarding the research sample, the observational data in this study are truncated in 2023, thereby excluding the most recent data on Chinese A-share listed manufacturing firms. And given that AI pilot zones were established relatively recently, a natural time lag exists between policy implementation and corporate response resulting in data gaps or inadequate observations for certain relevant firms. Subsequent research may extend the data period to include more recent data and further explore the implications of AI policy initiatives for enterprises’ green innovation practices. Regarding causal inference, this study examines the mechanism by which AI-driven industrial agglomeration impacts corporate green innovation. While the instrumental variable method mitigates endogeneity between AI policy and green innovation, higher levels of green innovation may attract related firms to form industrial clusters, potentially creating a reverse causal relationship between agglomeration and green innovation. Future research should further explore this possibility.

(2) Limitations of Measurement Standards. In this study, green innovation is measured solely by the number of green patent grants, which fails to encompass non-patentable innovation activities such as clean production processes and may not fully reflect its multidimensional nature. Industrial agglomeration is calculated using provincial-level data, potentially oversimplifying the concentration and interaction patterns of economic activities at smaller geographic units and hindering the accurate identification of localized agglomeration effects. Knowledge diversity was assessed solely on the basis of IPC classification data, overlooking non-patent knowledge such as managerial expertise and employee skills, thereby failing to fully characterize corporate knowledge structures. Future research should develop a more systematic and diversified green innovation indicator system, employ granular geographic data to measure industrial agglomeration, and integrate both patent and non-patent knowledge sources to construct a more comprehensive knowledge diversity metric.

(3) Limitations of Policy Evaluation. This paper uses a binary dummy variable to identify the presence or absence of AI policy, focusing on its effect on corporate green innovation. Although AI pilot zones are implemented only in specific regions, their policy effects may radiate or spill over into non-pilot zones within the same province or into adjacent areas through demonstration learning mechanisms. However, due to data constraints and the focus of this paper, the study did not empirically explore potential spillover effects between pilot and non-pilot zones. Future research should further examine the transmission pathways and impact boundaries of spillover effects to improve the credibility of research findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and C.Y.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L.; validation, C.Y.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L.; resources, J.L.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; visualization, C.Y.; supervision, C.Y.; project administration, C.Y.; funding acquisition, C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 20BGL019), the Guangxi Provincial Social Planning Fund (Grant No. 24GLB001), and the Shanxi Provincial Social Planning Fund (Grant No. 2025ZK060).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Green | Corporate Green Innovation |

| IA | Industrial Agglomeration |

| K-diversity | Knowledge Diversity |

References

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Ren, X.; Shi, Y. AI Adoption Rate and Corporate Green Innovation Efficiency: Evidence from Chinese Energy Companies. Energy Econ. 2024, 132, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Ying, J.; He, S.; Zhang, C.; Yan, J. Artificial Intelligence and Green Transformation of Manufacturing Enterprises. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 104, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijit, R.; Hu, Q.; Xu, J.; Ma, G. Greening through AI? The Impact of Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Pilot Zones on Green Innovation in China. Energy Econ. 2025, 146, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, M.D.; Bennedsen, M. Corporate Governance and Green Innovation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2016, 75, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Cho, T.S.; Chen, M.J. The Influence of Top Management Team Heterogeneity on Firms’ Competitive Moves. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 659–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Drivers of Green Innovations: The Impact of Export Intensity, Women Leaders, and Absorptive Capacity. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Maqsood, U.S.; Zahid, R.M.A.; Anwar, W. Regulating CEO Pay and Green Innovation: Moderating Role of Social Capital and Government Subsidy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 46163–46177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Cheng, J.; Ding, X. Impact of the Top Management Teams’ Environmental Attention on Dual Green Innovation in Chinese Enterprises: The Context of Government Environmental Regulation and Absorptive Capacity. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L. Senior Management’s Academic Experience and Corporate Green Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.; Leitão, J. Cooperation in innovation practices among firms in Portugal: Do external partners stimulate innovative advances? Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2009, 7, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalabik, B.; Fairchild, R.J. Customer, regulatory, and competitive pressure as drivers of environmental innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavova, K.; Jong, S. University Alliances and Firm Exploratory Innovation: Evidence from Therapeutic Product Development. Technovation 2021, 107, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prencipe, A.; Corsi, C.; Rodríguez-Gulías, M.J. Influence of the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem and its knowledge spillovers in developing successful university spin-offs. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 72, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.C.; Guo, Q.; Tsinopoulos, C. The bright and dark sides of institutional intermediaries: Industry associations and small-firm innovation. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Dai, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X. Does Environmental Regulation Induce Green Innovation? A Panel Study of Chinese Listed Firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z. Can Green Credit Interest Subsidy Policy Promote Corporate Green Innovation?—From the Perspective of Fiscal and Financial Policy Coordination. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Wu, X.; Shang, D.; Pan, L. How Government Environmental Attention Influences Corporate Green Innovation: A Chain Mediating Model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 218, 124195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhou, N.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Corporate Green Innovation: Can “Increasing Quantity” and “Improving Quality” Go Hand in Hand? J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Sun, J. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Green Innovation Efficiency: Moderating Role of Dynamic Capability. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Liu, Y.; Hu, F.; Wu, B. Effect of Digital Transformation on Enterprises’ Green Innovation: Empirical Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Energy Econ. 2023, 128, 107135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, F.; Guo, J.; Hu, G.; Song, Y. Can Artificial Intelligence Technology Improve Companies’ Capacity for Green Innovation? Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Energy Econ. 2025, 143, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Bai, Y. Strategic or Substantive Innovation?—The Impact of Institutional Investors’ Site Visits on Green Innovation Evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Lin, B. The AI-Sustainability Nexus: How Does Intelligent Transformation Affect Corporate Green Innovation? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 102, 104107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Yang, S.; Maqsood, U.S.; Zahid, R.M.A. Tapping into the Green Potential: The Power of Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Corporate Green Innovation Drive. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4375–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Machado, I.; Magrelli, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Artificial Intelligence in Innovation Research: A Systematic Review, Conceptual Framework, and Future Research Directions. Technovation 2023, 122, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicerone, G.; Faggian, A.; Montresor, S.; Rentocchini, F. Regional Artificial Intelligence and the Geography of Environmental Technologies: Does Local AI Knowledge Help Regional Green-Tech Specialization? Reg. Stud. 2023, 57, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, M.F.; Petraite, M. Industry 4.0 Technologies, Digital Trust and Technological Orientation: What Matters in Open Innovation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 161, 120332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, R.; Alraja, M.N.; Khashab, B. Sustainable Performance and Green Innovation: Green Human Resources Management and Big Data as Antecedents. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 4191–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canhoto, A.I.; Clear, F. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning as Business Tools: A Framework for Diagnosing Value Destruction Potential. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, M.F.; Tiwari, S.; Petraite, M.; Mubarik, M.; Raja Mohd Rasi, R.Z. How Industry 4.0 Technologies and Open Innovation Can Improve Green Innovation Performance? Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, T.; Fedyk, A.; He, A.; Hodson, J. Artificial Intelligence, Firm Growth, and Product Innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 151, 103745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics; Macmillan: London, UK, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, R.; Swann, P. Do Firms in Clusters Innovate More? Res. Policy 1998, 27, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Balezentis, T.; Shen, S.; Streimikiene, D. Human capital mismatch and innovation performance in high-technology enterprises: An analysis based on the micro-level perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. The Race between Man and Machine: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares, and Employment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018, 108, 1488–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, G.; Glaeser, E.L.; Kerr, W. What Causes Industry Agglomeration? Evidence from Coagglomeration Patterns. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 1195–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokovin, S.; Molchanov, P.; Bykadorov, I. Increasing Returns, Monopolistic Competition, and International Trade: Revisiting Gains from Trade. J. Int. Econ. 2022, 137, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, I. National Industry Trade Shocks, Local Labour Markets, and Agglomeration Spillovers. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2020, 87, 1399–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kallal, H.D.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Shleifer, A. Growth in Cities. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 1126–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmers, C. Choose the Neighbor before the House: Agglomeration Externalities in a UK Science Park. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a Knowledge-based Theory of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Zander, U. Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology. Organ. Sci. 1992, 3, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, J.M.; Walker, O.C. Selecting influential business-to-business customers in new product development: Relational embeddedness and knowledge heterogeneity considerations. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2004, 21, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qi, N.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Han, X.; Xuan, L. How Do Knowledge Diversity and Ego-Network Structures Affect Firms’ Sustainable Innovation: Evidence from Alliance Innovation Networks of China’s New Energy Industries. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, M.; Posinković, T.O.; Vlačić, B.; Gonçalves, R. A configurational approach to new product development performance: The role of open innovation, digital transformation and absorptive capacity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnabuci, G.; Operti, E. Where Do Firms’ Recombinant Capabilities Come from? Intraorganizational Networks, Knowledge, and Firms’ Ability to Innovate Through Technological Recombination. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1591–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollok, P.; Amft, A.; Diener, K.; Lüttgens, D.; Piller, F.T. Knowledge Diversity and Team Creativity: How Hobbyists Beat Professional Designers in Creating Novel Board Games. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Dechezleprêtre, A.; Hemous, D. Carbon taxes, path dependency and directed technical change: Evidence from the auto industry. J. Political. Econ. 2016, 124, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Lin, Y.X.; Li, D.D. How Does the Application of Artificial Intelligence Technology Affect Corporate Innovation? China Ind. Econ. 2024, 41, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Blocher, J.D. Measurement of Firm Diversification: Is It Robust? Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 874–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Sun, Y.J.; Chen, D.K. Evaluating the Effects of Government Air Pollution Control: An Empirical Study from China’s “Low-Carbon City” Development. Manag. World 2019, 35, 95–108+195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.H.; Yu, Y.Z.; Zhang, S.L. Internet Development and Manufacturing Productivity Enhancement: Internal Mechanisms and Chinese Experience. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 36, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L.S.; LaLonde, R.J.; Sullivan, D.G. Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 685–709. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big Bad Banks? The Winners and Losers from Bank Deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Razzaq, A.; Sharif, A.; Yang, X. Influence Mechanism between Green Finance and Green Innovation: Exploring Regional Policy Intervention Effects in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.Q.; Zhang, K.P.; Guo, L.P.; Feng, X. How Does Artificial Intelligence Enhance Corporate Productivity?—A Perspective Based on Labor Skill Structure Adjustment. Manag. World 2024, 40, 101–116+133+117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Bloom, N.; Blundell, R. Competition and innovation: An inverted-U relationship. Q. J. Econ. 2005, 120, 701–728. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Zhu, Y. The impact of artificial intelligence policy on green innovation of firms. Energy Econ. 2025, 148, 108524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.