Tropical Island Visual Strategies for Sustainable Tourism: Contrasting Real Photographs and AI-Generated Images

Abstract

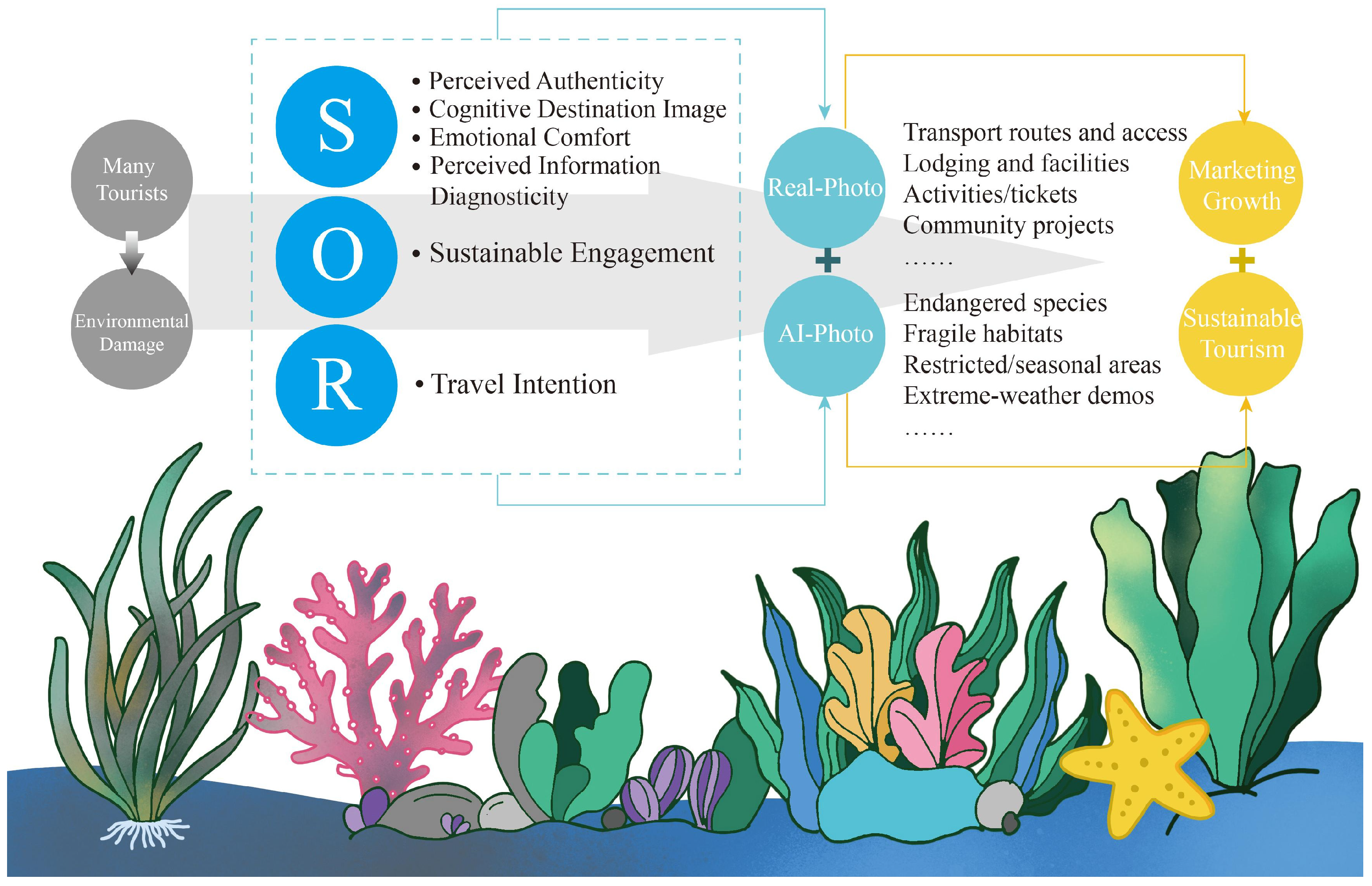

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

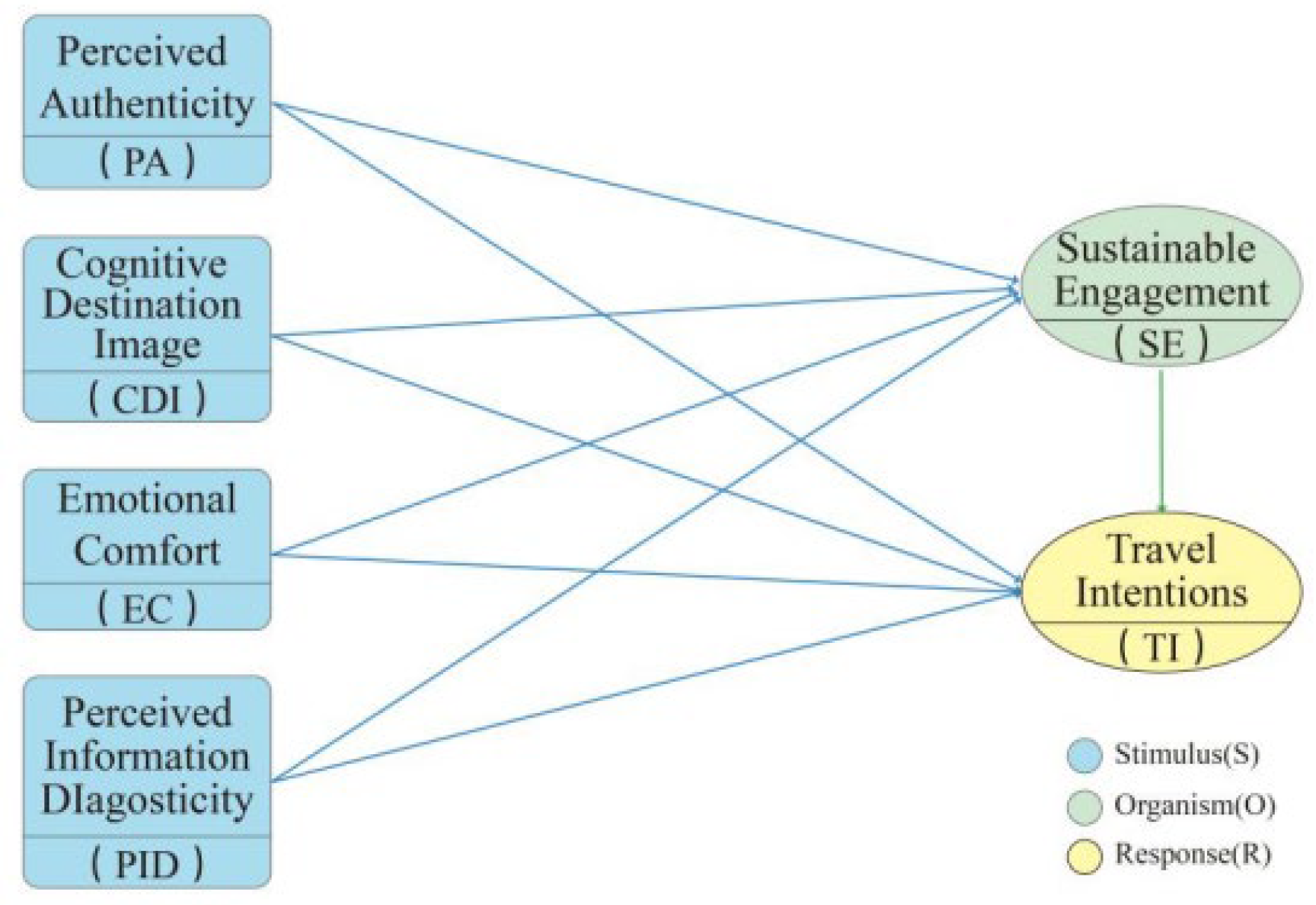

2.1. SOR Model in Tourism and Sustainability

2.2. Key Structures of Stimulus

2.3. Key Structures of Organism (Mediating Variables)

2.4. Structures of Response and Behavior

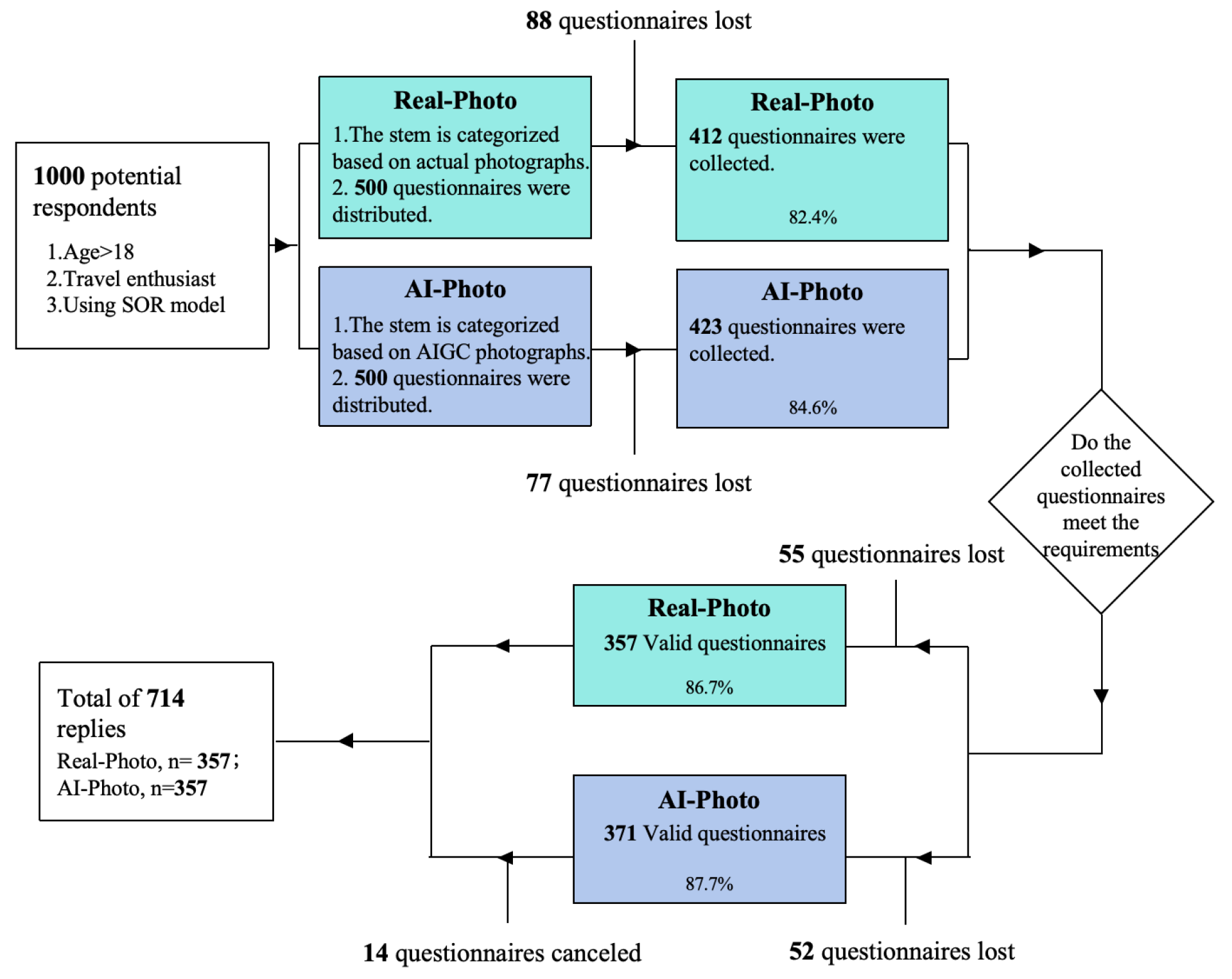

3. Methods

3.1. Measuring Instruments

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Personal Basic Information Analysis

3.4. Analytical Method

4. Results

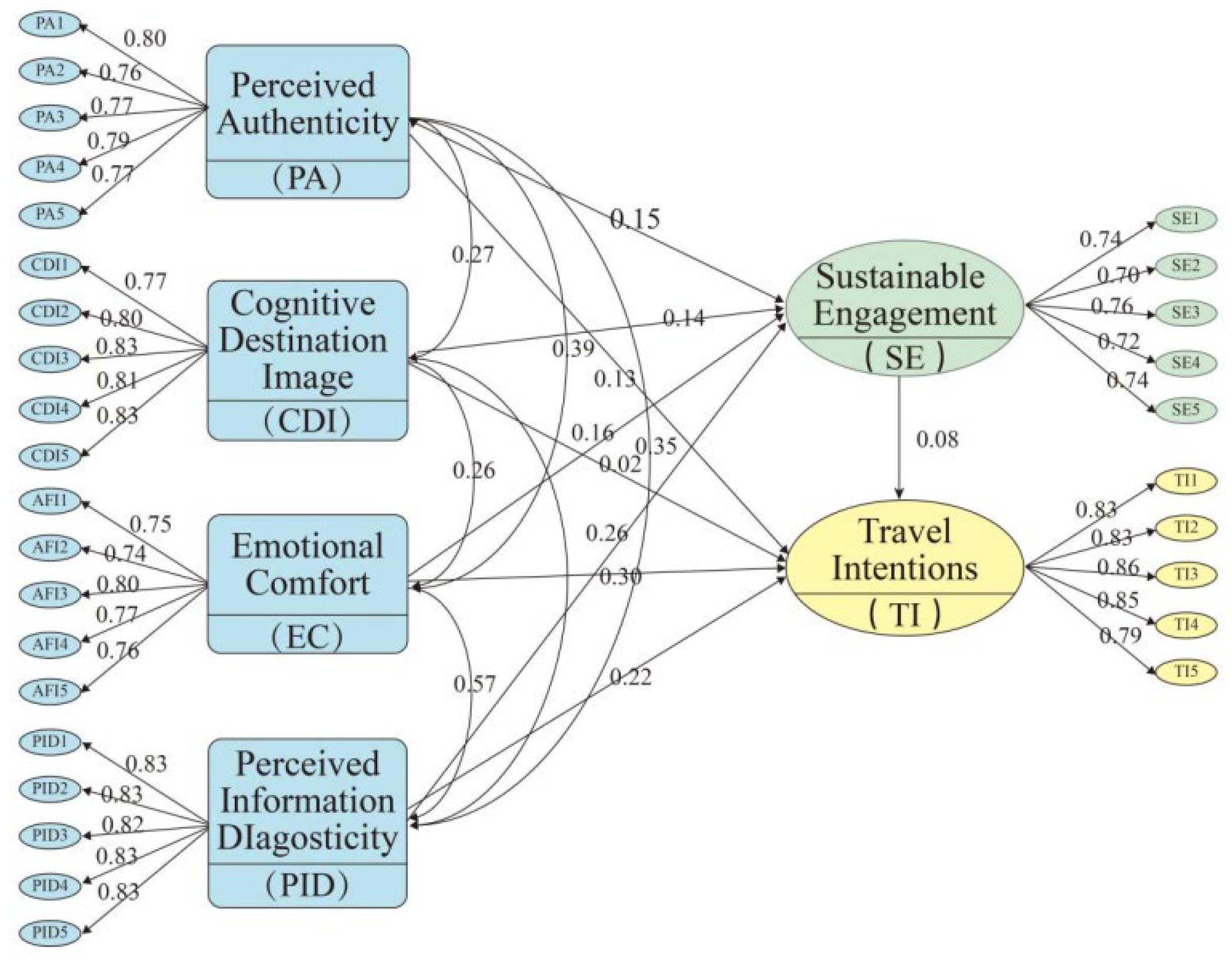

4.1. Analysis Measurement Model

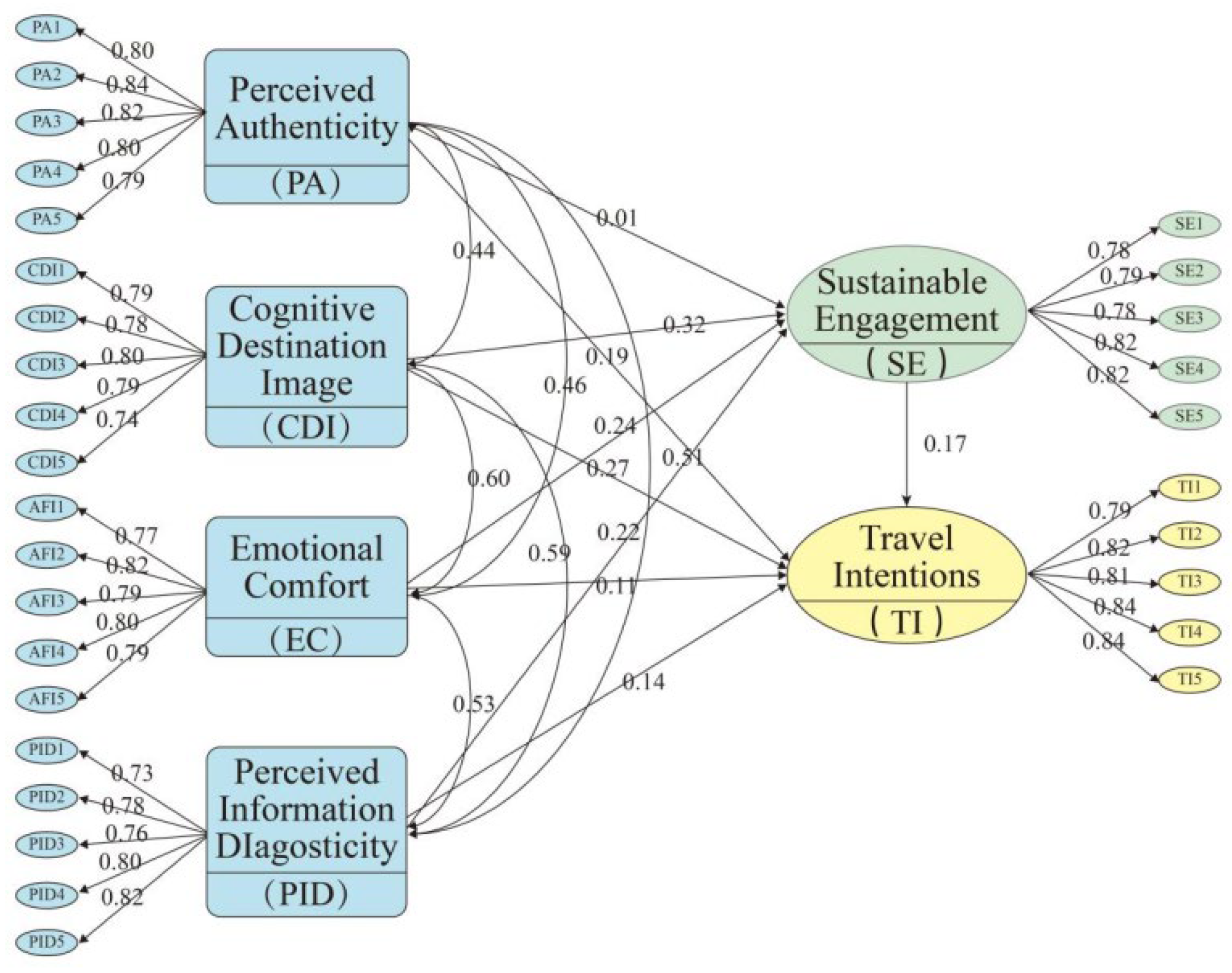

4.2. SEM and Direct and Mediated Path Tests

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Dual-Track Marketing Strategy and Sustainable Conversion

6.2. Limitations

6.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Personal Basic Information

| Personal Basic Information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Options | Frequency (N=) | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Male | 488 | 68.35% |

| Female | 226 | 31.65% | |

| Age | Under 18 | 62 | 8.68% |

| 18–25 | 68 | 9.52% | |

| 26–35 | 144 | 20.17% | |

| 36–45 | 216 | 30.25% | |

| 46–60 | 196 | 27.45% | |

| 60 years and over | 28 | 3.92% | |

| Educational background | High school and below | 64 | 8.96% |

| Junior college/Undergraduate | 514 | 71.99% | |

| Master’s degree or above | 136 | 19.05% | |

| Employment status | Student | 194 | 27.17% |

| Civil servant | 224 | 31.37% | |

| Staff | 146 | 20.45% | |

| Freelancer | 92 | 12.89% | |

| Retiree | 40 | 5.60% | |

| Other | 18 | 2.52% | |

| Income | 50,000 and below | 94 | 13.17% |

| 50,000–100,000 | 100 | 14.01% | |

| 100,000–200,000 | 260 | 36.41% | |

| 200,000 and over | 196 | 27.45% | |

| Not willing to disclose | 64 | 8.96% | |

| Total | 714 | ||

Appendix B. Reliability and Validity of Questionnaire

| Real-Photo | AI-Photo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Items | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha | Items | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| Perceived Authenticity | PA1 | 0.739 | 0.885 | 0.627 | 0.885 | PA1 | 0.755 | 0.905 | 0.656 | 0.905 |

| PA2 | 0.705 | PA2 | 0.791 | |||||||

| PA3 | 0.718 | PA3 | 0.765 | |||||||

| PA4 | 0.741 | PA4 | 0.752 | |||||||

| PA5 | 0.71 | PA5 | 0.745 | |||||||

| Cognitive Destination Image | CDI1 | 0.725 | 0.905 | 0.655 | 0.901 | CDI1 | 0.734 | 0.886 | 0.605 | 0.886 |

| CDI2 | 0.752 | CDI2 | 0.729 | |||||||

| CDI3 | 0.782 | CDI3 | 0.732 | |||||||

| CDI4 | 0.765 | CDI4 | 0.74 | |||||||

| CDI5 | 0.781 | CDI5 | 0.685 | |||||||

| Emotional Comfort | EC1 | 0.693 | 0.874 | 0.682 | 0.875 | EC1 | 0.715 | 0.895 | 0.632 | 0.895 |

| EC2 | 0.683 | EC2 | 0.772 | |||||||

| EC3 | 0.725 | EC3 | 0.738 | |||||||

| EC4 | 0.715 | EC4 | 0.749 | |||||||

| EC5 | 0.694 | EC5 | 0.737 | |||||||

| Perceived Information Diagnosticity | PID1 | 0.779 | 0.916 | 0.686 | 0.916 | PID1 | 0.678 | 0.884 | 0.604 | 0.882 |

| PID2 | 0.791 | PID2 | 0.722 | |||||||

| PID3 | 0.779 | PID3 | 0.709 | |||||||

| PID4 | 0.783 | PID4 | 0.742 | |||||||

| PID5 | 0.79 | PID5 | 0.752 | |||||||

| Sustainable Engagement | SE1 | 0.666 | 0.852 | 0.636 | 0.852 | SE1 | 0.724 | 0.896 | 0.634 | 0.895 |

| SE2 | 0.634 | SE2 | 0.734 | |||||||

| SE3 | 0.692 | SE3 | 0.732 | |||||||

| SE4 | 0.655 | SE4 | 0.763 | |||||||

| SE5 | 0.671 | SE5 | 0.766 | |||||||

| Travel Intensions | TI1 | 0.796 | 0.92 | 0.697 | 0.918 | TI1 | 0.75 | 0.913 | 0.678 | 0.913 |

| TI2 | 0.789 | TI2 | 0.779 | |||||||

| TI3 | 0.822 | TI3 | 0.771 | |||||||

| TI4 | 0.806 | TI4 | 0.797 | |||||||

| TI5 | 0.753 | TI5 | 0.796 | |||||||

Appendix C. Correlation Analysis Between Structural Variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-photo | 1. Perceived authenticity | 3.748 | 0.95 | 0.779 | |||||

| 2. Cognitive destination image | 3.231 | 1.000 | 0.240 ** | 0.809 | |||||

| 3. Emotional comfort | 3.417 | 1.103 | 0.342 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.763 | ||||

| 4. Perceived information diagnosticity | 3.248 | 1.125 | 0.320 ** | 0.245 ** | 0.508 ** | 0.828 | |||

| 5. Sustainable engagement | 3.61 | 1.000 | 0.299 ** | 0.259 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.392 ** | 0.732 | ||

| 6. Travel intensions | 3.615 | 1.066 | 0.322 ** | 0.199 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.835 | |

| AI-photo | 1. Perceived authenticity | 3.713 | 1.038 | 0.810 | |||||

| 2. Cognitive destination image | 3.425 | 1.117 | 0.391 ** | 0.780 | |||||

| 3. Emotional comfort | 3.538 | 1.068 | 0.419 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.795 | ||||

| 4. Perceived information diagnosticity | 3.511 | 1.031 | 0.454 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.778 | |||

| 5. Sustainable engagement | 3.376 | 1.011 | 0.338 ** | 0.538 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.483 ** | 0.796 | ||

| 6. Travel intensions | 3.097 | 1.035 | 0.449 ** | 0.548 ** | 0.483 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.823 |

References

- UN Tourism. World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex: 2024 Year-End Update; UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W.; Dodds, R. Island tourism: Vulnerable or resistant to overtourism. Highlights Sustain. 2022, 1, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, L.; Liu, H.; Song, H. Predicting tourism recovery from COVID-19: A time-varying perspective. Econ. Model. 2024, 135, 106706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel&Tourism Council (WTTC). Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2024: Maldives; WTTC: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hainan Pushes Full Throttle to Become an International Tourism Destination. China Daily. 20 January 2025. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Long, C.; Lu, S.; Chang, J.; Zhu, J.; Chen, L. Tourism environmental carrying capacity review, hotspot, issue, and prospect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, K.M.; Uchiyama, Y.; Quevedo, J.M.D.; Kohsaka, R. Tourism impacts on small island ecosystems: Public perceptions from Karimunjawa Island, Indonesia. J. Coast. Conserv. 2022, 26, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism and the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity. J. Herit. Tour. 2010, 5, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lan, J.; Chien, F.; Sadiq, M.; Nawaz, M.A. Role of tourism development in environmental degradation: A step towards emission reduction. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M. International tourism and climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2012, 3, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, J.N.; Raymond, E. National destination pledges: Visitor management through emotional engagement, commitment and interpretation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulchand-Gidumal, J. Impact of artificial intelligence in travel, tourism, and hospitality. In Handbook of e-Tourism; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1943–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Collaborative destination marketing: A case study of Elkhart county, Indiana. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Clavé, S.A. Tourism analytics with massive user-generated content: A case study of Barcelona. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel, I.L. The Palau legacy pledge: A case study of advertising, tourism, and the protection of the environment. Westminst. Pap. Commun. Cult. 2020, 15, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yao, R. Supporting Sustainable Island Tourism Through Infrastructuring Co-Design: A Case Study from Mayu Island. Isl. Stud. J. 2025. Early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, H.R. Digitalization and sustainable branding in tourism destinations from a systematic review perspective. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deringer, S.A.; Hanley, A. Virtual reality of nature can be as effective as actual nature in promoting ecological behavior. Ecopsychology 2021, 13, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, C.; Lo, L.S.H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Gao, J.; Clara, U.; Dai, Z.; Nakaoka, M.; Yang, H.; et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted environmental DNA metabarcoding and high-resolution underwater optical imaging for noninvasive and innovative marine environmental monitoring. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Escobar, O.; Lan, S. Virtual reality tourism to satisfy wanderlust without wandering: An unconventional innovation to promote sustainability. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Meng, T. Image Generative AI in Tourism: Trends, Impacts, and Future Research Directions. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2025, 10963480251324676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, K.; Walters, G.; Hughes, K. The effectiveness of virtual vs. real-life marine tourism experiences in encouraging conservation behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 742–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynova, E.; West, S.G.; Liu, Y. Review of principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2018, 25, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z. Greenwashing versus green authenticity: How green social media influences consumer perceptions and green purchase decisions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneideriene, A.; Legenzova, R. Greenwashing prevention in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures: A bibliometric analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 74, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, Q.; Huang, X.; Xie, J.; Xie, M.; Shi, J. Image and text presentation forms in destination marketing: An eye-tracking analysis and a laboratory experiment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1024991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Xu, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L. A study on the influence of rural tourism’s perceived destination restorative qualities on loyalty based on SOR model. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1529686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockemer, D.; Stockemer, G.; Glaeser, J. Quantitative Methods for the Social Sciences; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 50, p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Pahor Zvanut, A.; Zabukovec Baruca, P. Social Media Marketing Strategy in the Tourism Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Han, J.; Gandolfi, F.; Alturise, F.; Alkhalaf, S. Fostering eco-conscious tourists: How sustainable marketing drives green consumption behaviors. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, V.A. Stimuli–organism-response framework: A meta-analytic review in the store environment. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, A.; Keles, H.; Uslu, F.; Keles, A.; Yayla, O.; Tarinc, A.; Ergun, G.S. The effect of responsible tourism perception on place attachment and support for sustainable tourism development: The moderator role of environmental awareness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ahn, S. Exploring user behavior based on metaverse: A modeling study of user experience factors. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Stepchenkova, S. Effect of tourist photographs on attitudes towards destination: Manifest and latent content. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wei, C.; Nie, L. Experiencing authenticity to environmentally responsible behavior: Assessing the effects of perceived value, tourist emotion, and recollection on industrial heritage tourism. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1081464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y. Tourists’ negative emotions: Antecedents and consequences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1987–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, W. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. In The Political Nature of Cultural Heritage and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 469–490. [Google Scholar]

- Beerli, A.; Martin, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Pratt, G. A description of the affective quality attributed to environments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Benbasat, I. Virtual product experience: Effects of visual and functional control of products on perceived diagnosticity and flow in electronic shopping. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2004, 21, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, L.D.; Sevilha Gosling, M.D. Dimensions of image: A model of destination image formation. Tour. Anal. 2018, 23, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Jung, T. Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, J.; Yang, W.; Yan, W.; Nah, K. The Impact of Role-Playing Game Experience on the Sustainable Development of Ancient Architectural Cultural Heritage Tourism: A Mediation Modeling Study Based on SOR Theory. Buildings 2025, 15, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jamal, T. Touristic quest for existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Back to the past: A sub-segment of Generation Y’s perceptions of authenticity. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.; Björk, P.; Weidenfeld, A. Authenticity and place attachment of major visitor attractions. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.T.H.; Lee, W.I.; Chen, T.H. Environmentally responsible behavior in ecotourism: Exploring the role of destination image and value perception. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Ye, N.; Zhang, X. The influence of environmental cognition on pro-environmental behavior: The mediating effect of psychological distance. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference on Modern Management, Education Technology, and Social Science (MMETSS 2018), Zhuhai, China, 28–30 September 2018; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Timothy, D.J. Authentic or comfortable? What tourists want in the destination. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 3, 1437014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yue, T.; Wang, C.; Yang, W.; Hansen, P.; You, F. Experimental study on abstract expression of human-robot emotional communication. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Shani, A.; Belhassen, Y. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, N.; Dada, Z.A.; Shah, S.A. Developing tourist typology based on environmental concern: An application of the latent class analysis model. SN Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.L.; Kim, J.; An, M. The role of VR shopping in digitalization of SCM for sustainable management: Application of SOR model and experience economy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Hofacker, C.F.; Alguezaui, S. What makes information in online consumer reviews diagnostic over time? The role of review relevancy, factuality, currency, source credibility and ranking score. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Staelin, R. Effects of quality and quantity of information on decision effectiveness. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, D.; Srivastava, J. Effect of manufacturer reputation, retailer reputation, and product warranty on consumer judgments of product quality: A cue diagnosticity framework. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 10, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: Compared analysis of first-time and repeat tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Chung, N. Does virtual reality (VR) affect visitors’ experience? Understanding the role of sensory imagery and visitor behavior. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2015, 15, 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wu, M. Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour in travel destinations: Benchmarking the power of social interaction and individual attitude. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1371–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, J.E.; Sanchez, M.I.; Sánchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, Y. Investigating the factors influencing urban residents’ low-carbon travel intention: A comprehensive analysis based on the TPB model. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 22, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. Destination image, on-site experience and behavioural intentions: Path analytic validation of a marketing model on domestic tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1653–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhart, F.; Malär, L. Authenticity in luxury branding. In Research Handbook on Luxury Branding; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.M.; Lester, L.; Bulsara, C.; ECtterson, A.; Bennett, K.; Allen, E.; Joske, D. Patient Evaluation of Emotional Comfort ExECrienced (ECECE): Developing and testing a measurement instrument. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.R.; Lehmann, D.R.; Xie, Y. Decision comfort. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R. What makes online reviews helpful? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative influences in e-WOM. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yan, W.; Gong, J.; Wang, S.; Nah, K.; Cheng, W. Motivation of University Students to Use LLMs to Assist with Online Consumption of Sustainable Products: An Analysis Based on a Hybrid SEM–ANN Approach. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H. Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.; Hole, G.J. How to Design and Report Experiments; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Wang, Y. Chinese outbound tourism research: A review. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Reza, M.N.H.; Al Mamun, A.; Masud, M.M.; Rahman, M.R.C.A. Predicting guest satisfaction and willingness to pay premium prices for green hotels. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, M.; McLean, G. Examining tourism consumers’ attitudes and the role of sensory information in virtual reality experiences of a tourist destination. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1666–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Kasra, M.; O’Brien, J. This photograph has been altered: Testing the effectiveness of image forensic labeling on news image credibility. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.07951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mansournia, M.A.; Jewell, N.P.; Greenland, S. Case–control matching: Effects, misconceptions, and recommendations. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; McCleary, K.W. An Integrative Model of Tourists’Information Search Behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, R.; De Wever, B.; Nissinen, K.; Cincinnato, S. What makes the difference–PIAAC as a resource for understanding the problem-solving skills of EuroEC’s higher-education adults. Comput. Educ. 2019, 129, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T.; Marcoulides, G.A. A method for comparing completely standardized solutions in multiple groups. Struct. Equ. Model. 2000, 7, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgerwood, A.; Shrout, P.E. The trade-off between accuracy and precision in latent variable models of mediation processes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Revised Ed.); Routledge: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-El-Fattah, S.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2010, 5, 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, S.S.; Leong, A.M.W.; Hung, C.W.; Huan, T.C. Destination authenticity influence on tourists’ behavioral intentions, involvement and nostalgic sentiments. Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.; Filimonau, V.; Sezerel, H. AI-thenticity: Exploring the effect of perceived authenticity of AI-generated visual content on tourist patronage intentions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 34, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wu, J. Sport tourist perceptions of destination image and revisit intentions: An adaption of Mehrabian-Russell’s environmental psychology model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.C.; Lo, M.C.; Ibrahim, W.H.W.; Mohamad, A.A.; bin Suaidi, M.K. The effect of hard infrastructure on perceived destination competitiveness: The moderating impact of mobile technology. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, G.; Xu, S.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Seeing destinations through short-form videos: Implications for leveraging audience involvement to increase travel intention. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1024286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.T.; Zhu, D.; Liu, C.; Kim, P.B. A systematic review of empirical studies of pro-environmental behavior in hospitality and tourism contexts. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3982–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Yang, F.; Sotiriadis, M.D. Experiential consumption dimensions and pro-environment behaviour by Gen Z in nature-based tourism: A Chinese perspective. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; McLeay, F.; Tsui, B.; Lin, Z. Consumer perceptions of information helpfulness and determinants of purchase intention in online consumer reviews of services. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, S.; Hashim, N.H. The Mediating Effect of Perceived Diagnosticity on eWOM Elements and Restaurant Selection Intention. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herédia-Colaço, V. Pro-environmental messages have more effect when they come from less familiar brands. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variation | Items |

|---|---|

| Perceived Authenticity (PA) | Based on research in the fields of tourism studies and marketing communication concerning destinations and media (Ning, 2017) [41]. |

| Cognitive Destination Image (CDI) | It originates from the classic cognitive and affective dual-dimension framework of destination imagery (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Beerli & Martín, 2004) [22,42]. |

| Emotional Comfort (EC) | Based on the research on low-impact positive emotions and designed emotions within the circumplex model of emotion (Russell, 1980) [43]. |

| Perceived Information Diagnosticity (PID) | It stems from the “information diagnosticity framework” in information systems and marketing (Jiang & Benbasat, 2004) [44]. |

| Measure | Reference Scale | Scale Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Authenticity (PA) | Kolar and Zabkar (2010) [73] Ning (2017) [41] Morhart and Malär (2020) [74] | PA1 | I believed this picture depicted a real island rather than a fictional one. |

| PA2 | I regarded the depiction as authentic overall. | ||

| PA3 | I felt the elements in the scene fit together | ||

| PA4 | I did not detect any exaggeration or unrealistic embellishment in the photo. | ||

| PA5 | I regarded the depiction as true to life. | ||

| Cognitive Destination Image (CDI) | Baloglu and McCleary (1999) [22] Stylidis et al. (2017) [57] | CDI1 | I thought the destination’s infrastructure is well-developed. |

| CDI2 | I felt the place was well-managed. | ||

| CDI3 | I perceived a distinctive local culture (e.g., arts, crafts, performances). | ||

| CDI4 | I saw the surroundings as clean and orderly. | ||

| CDI5 | I found it easy to get around within the destination, with clear routes. | ||

| Emotional Comfort (EC) | Williams et al. (2017) [75] Parker et al. (2016) [76] | EC1 | I felt relaxed after viewing the image. |

| EC2 | When I saw this picture, I felt calm | ||

| EC3 | When I saw this picture I felt composed. | ||

| EC4 | I felt reassured rather than agitated when I saw this picture | ||

| EC5 | After viewing this image, I felt at ease. | ||

| Perceived Information Diagnosticity (PID) | Jiang and Benbasat (2004) [44] Filieri (2015) [77] | PID1 | I found this image useful for judging the destination’s overall quality. |

| PID2 | When I saw this picture, I had a clear understanding of the specific situation of this island. | ||

| PID3 | I can used this image to reach an overall judgment about the destination. | ||

| PID4 | When I saw this picture, I felt less uncertain about the destination. | ||

| PID5 | I can compare this location to other options thanks to this picture. | ||

| Sustainable Engagement (SE) | Munar and Jacobsen (2014) [67] Han (2015) [78] Yu et al. (2025) [79] | SE1 | When I travel, I would rather use low-impact and ecologically friendly techniques. |

| SE2 | I’ll abide by destination policies that preserve the environment. | ||

| SE3 | I’m prepared to take part in activities that support the destination’s sustainable growth. | ||

| SE4 | I perceived the destination’s efforts toward sustainability. | ||

| SE5 | I’ll abide by destination policies that uphold and preserve cultural traditions. | ||

| Travel Intention (TI) | Han et al. (2010) [63] Lam and Hsu (2006) [80] | TI1 | I intend to visit this destination within the next year. |

| TI2 | I am likely to book a trip to this destination. | ||

| TI3 | I am inclined to add this destination to my shortlist for upcoming trips. | ||

| TI4 | Given comparable options, I would prioritize this destination. | ||

| TI5 | I am willing to allocate time and budget to visit this destination. | ||

| CMIN | DF | CMIN/DF | RMR | GFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Value | - | - | <3 | <0.08 | >0.9 | >0.9 | <0.08 | - |

| Real-photo | 453.975 | 390 | 1.164 | 0.057 | 0.923 | 0.989 | 0.990 | 0.021 |

| AI-photo | 486.655 | 390 | 1.202 | 0.024 | 0.919 | 0.987 | 0.988 | 0.024 |

| Measurement | CMIN/DF | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | NFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | PNFI | PCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | <3 | >0.8 | >0.8 | <0.08 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.5 | >0.5 |

| Real-Photo | 1.161 | 0.923 | 0.909 | 0.021 | 0.933 | 0.990 | 0.989 | 0.990 | 0.836 | 0.888 |

| AI-Photo | 1.198 | 0.919 | 0.903 | 0.024 | 0.935 | 0.989 | 0.987 | 0.989 | 0.838 | 0.886 |

| Hypothesis | Path | STD. Estimate | Non.Std. | S.E. | C.R. | p | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | ||||||||

| Real- photo | - | PA → SE | 0.154 | 0.161 | 0.064 | 2.466 | 0.014 | Supported |

| - | CDI → SE | 0.140 | 0.123 | 0.051 | 2.427 | 0.015 | Supported | |

| - | EC → SE | 0.160 | 0.146 | 0.067 | 2.200 | 0.028 | Supported | |

| - | PID → SE | 0.258 | 0.226 | 0.062 | 3.658 | *** | Supported | |

| H1 | PA → TI | 0.127 | 0.152 | 0.069 | 2.208 | 0.027 | Supported | |

| H3 | CDI → TI | 0.140 | 0.123 | 0.051 | 2.427 | 0.046 | Supported | |

| H5 | EC → TI | 0.299 | 0.313 | 0.072 | 4.343 | *** | Supported | |

| H7 | PID → TI | 0.224 | 0.224 | 0.066 | 3.383 | *** | Supported | |

| - | SE → TI | 0.077 | 0.088 | 0.070 | 1.257 | 0.039 | Supported | |

| AI-photo | - | PA → SE | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.058 | 0.163 | 0.871 | Not Supported |

| - | CDI → SE | 0.322 | 0.326 | 0.073 | 4.471 | *** | Supported | |

| - | EC → SE | 0.236 | 0.232 | 0.066 | 3.530 | *** | Supported | |

| - | PID → SE | 0.225 | 0.197 | 0.060 | 3.294 | *** | Supported | |

| H1 | PA → TI | 0.188 | 0.175 | 0.052 | 5.352 | *** | Supported | |

| H3 | CDI → TI | 0.273 | 0.257 | 0.067 | 3.826 | *** | Supported | |

| H5 | EC → TI | 0.111 | 0.102 | 0.059 | 1.724 | 0.035 | Supported | |

| H7 | PID → TI | 0.144 | 0.118 | 0.054 | 2.187 | 0.029 | Supported | |

| - | SE → TI | 0.215 | 0.26 | 0.077 | 3.396 | *** | Supported |

| Real-Photo | AI-Photo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Hypothesis | Effect | 95% CI | SE | z/t | p | Effect | 95% CI | SE | z/t | p | Result | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| PA → SE → TI | H2 | 0.026 | 0.005 | 0.049 | 0.011 | 2.274 | 0.023 | 0.006 | −0.011 | 0.027 | 0.009 | 0.620 | 0.535 | Supported (Real-Photo) Not Supported (AI-Photo) |

| CDI → SE → TI | H4 | 0.077 | 0.038 | 0.113 | 0.019 | 3.971 | *** | 0.046 | 0.019 | 0.091 | 0.018 | 2.535 | 0.011 | Supported |

| EC → SE → TI | H6 | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.066 | 0.015 | 2.126 | 0.034 | 0.038 | 0.014 | 0.074 | 0.016 | 2.418 | 0.016 | Supported |

| PID → SE → TI | H8 | 0.061 | 0.023 | 0.111 | 0.022 | 2.733 | 0.006 | 0.034 | 0.010 | 0.065 | 0.014 | 2.418 | 0.016 | Supported |

| Real-Photo | AI-Photo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation | Direct Effects (to TI) | Rank | Mediated Effects (Via SE to TI) | Rank | Direct Effects (to TI) | Rank | Mediated Effects (Via SE to TI) | Rank |

| EC | 0.299 *** | 1 | 0.032 * | 3 | 0.111 * | 5 | 0.038 * | 2 |

| PID | 0.224 *** | 2 | 0.061 ** | 2 | 0.144 * | 4 | 0.034 * | 3 |

| CDI | 0.14 * | 3 | 0.077 *** | 1 | 0.273 *** | 1 | 0.046 * | 1 |

| PA | 0.127 * | 4 | 0.026 * | 4 | 0.188 *** | 3 | 0.006 | Not Supported |

| SE | 0.077 * | 5 | - | - | 0.215 *** | 2 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cheng, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Yan, W.; Nah, K.; Gong, J. Tropical Island Visual Strategies for Sustainable Tourism: Contrasting Real Photographs and AI-Generated Images. Sustainability 2026, 18, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010285

Cheng W, Yu J, Wang S, Yan W, Nah K, Gong J. Tropical Island Visual Strategies for Sustainable Tourism: Contrasting Real Photographs and AI-Generated Images. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010285

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Wei, Junjie Yu, Siqin Wang, Wenjun Yan, Ken Nah, and Jiaxuan Gong. 2026. "Tropical Island Visual Strategies for Sustainable Tourism: Contrasting Real Photographs and AI-Generated Images" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010285

APA StyleCheng, W., Yu, J., Wang, S., Yan, W., Nah, K., & Gong, J. (2026). Tropical Island Visual Strategies for Sustainable Tourism: Contrasting Real Photographs and AI-Generated Images. Sustainability, 18(1), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010285