Abstract

A comparative study on the adsorption of ciprofloxacin (CIP) and sulfamethoxazole (SMX) onto CO2-activated biochars derived from leather tannery waste (ABT) and Sargassum brown macroalgae (ABS) is presented. N2 physisorption revealed that ABS possesses a higher Langmuir surface area (1305 m2/g) and a hierarchical micro–mesoporous structure, whereas ABT exhibits a lower surface area (412 m2/g) and a predominantly microporous texture. CHNS and FTIR analyses confirmed the presence of N-, O-, and S-containing heteroatoms and functional groups on both adsorbents, enhancing surface reactivity. Adsorption isotherms fitted well to the Langmuir model, with ABS showing superior maximum capacities of 256.41 mg/g (CIP) and 256.46 mg/g (SMX) compared to ABT (210.13 and 213.00 mg/g, respectively). Kinetic data followed a pseudo-second-order model (R2 > 0.998), with ABS exhibiting faster uptake due to its mesoporosity. Over eight reuse cycles, ABS retained >75% removal efficiency for both antibiotics, while ABT declined to 60–70%. pH-dependent adsorption behavior was governed by the point of zero charge (pHPZC≈ 9.0 for ABT; ≈7.2 for ABS), influencing electrostatic and non-electrostatic interactions. These findings demonstrate that ABS is a highly effective, sustainable adsorbent for antibiotic removal in water treatment applications.

1. Introduction

Antibiotics, as antimicrobial compounds, are significantly used in animal and human medicine, as well as their extensive utilization in livestock and agriculture [1]. Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and Ciprofloxacin (CIP) are widely consumed antibiotics. SMX, as a second-generation quinolone, has a suitable antibiotic virtue against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus and is highly beneficial in animal husbandry, medical, and aquaculture [2]. CIP is introduced as a third-generation fluoroquinolone antibiotic and is used for the treatment of anthrax, urinary tract infections, and tuberculosis [3]. However, they have issued rising micro-pollutions in aquatic ecosystems, which have caused serious health and environmental concerns. Studies reporting antibiotic pollution in the Asia–Pacific region exist [4], but similar investigations remain limited across the Middle East and North Africa [5]. In Iran, antibiotic consumption in Tehran Province was assessed in 2016 using the ATC/DDD method (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC)/Defined Daily Dose (DDD) system and reported as DDD/1000 inhabitants/day). Ciprofloxacin (79.62 mg/1000 inh/day) showed the highest influent loads at wastewater treatment plants in Tehran [6]. Thus, it is of crucial importance to find efficient and appropriate techniques for the removal of these pharmaceuticals from water [1].

Various methods have been employed to treat water contaminated with antibiotics and pharmaceuticals, including adsorption [7], catalytic/photocatalytic degradation [8,9], microbial degradation [10], liquid extraction [11], reverse osmosis [12], ozone oxidation [12], electrocoagulation [13], and membrane filtration [14]. However, many of these approaches face significant challenges, such as high operational costs, limited effectiveness at low contaminant concentrations, the generation of chemical sludge, and excessive consumption of time, chemicals, and energy [7,15]. Among these, adsorption stands out for its simplicity, efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and ability to safely eliminate micro-pollutants at trace levels without producing harmful byproducts [16,17].

A wide range of carbon-based and carbonaceous materials, such as activated carbon [18], carbon nanotubes [19], graphene oxide [20], and biochar [21], have been extensively utilized as adsorbents in wastewater treatment. Among these, biochar has emerged as an up-and-coming option for removing pollutants from both water [22] and soil [23], owing to its exceptional surface area, advanced pore networks, strong adsorption capabilities, abundant self-functional groups and self-doped heteroatoms, hydrophobic characteristics, and environmentally friendly nature. Furthermore, adopting biochar as an alternative adsorbent paves the way for its commercialization while advancing global carbon sequestration efforts [24]. These carbon-rich materials are generated through medium or slow pyrolysis, where organic substances of biological origin are heated under conditions with limited oxygen [25]. Feedstocks like industrial solid waste, agricultural byproducts, sludge, and compost are commonly utilised for producing biochar [26]. It is important to highlight that the chemical and structural characteristics of biochar are significantly influenced by the type of raw biomass, the conditions under which pyrolysis occurs, and the activation process used [27]. Various activation methods for carbon materials have been documented, broadly categorized into two main approaches: chemical activation, which employs agents such as KOH, NaOH, ZnCl2, HCl, NH3, K2CO3, and H2SO4, and physical activation, which utilizes steam, CO2, or ozone at elevated carbonization temperatures. These activation techniques result in partial oxidation of the carbon, enhancing the material’s surface area and porosity [25,26,27,28,29].

This research focuses on exploring the potential of biochar as a sustainable and efficient carbon-based adsorbent for SMX and CIP, aiming to reduce their environmental impact. Therefore, two distinct biomass types were studied for developing biochar-based adsorbents: (a) leather tannery waste, which is an animal-based raw material, and industrial waste categorized as a second-generation biomass with a high content of collagen and proteins; (b) Sargassum brown macroalgae from the Venice lagoon, with vegetal origin represents a third-generation biomass, abundant in carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. To the best of our knowledge, there has been limited research exploring the effectiveness of biochar derived from leather tannery waste and Sargassum macroalgae in adsorbing SMX and CIP. Additionally, tannery shaving waste is a significant byproduct generated from key industrial sectors in Italy. The widespread presence of Sargassum in the lagoon has become an environmental concern due to issues such as the release of unpleasant odors during decomposition, the stimulation of bacterial growth that may lead to skin irritation, and the generation of harmful toxins [30]. In our previous research, we discovered that the biochar derived from leather tannery waste and Sargassum macroalgae demonstrated effective and promising performance in the adsorption of cationic dyes [31], anode for lithium-ion batteries [32], an electrode for a supercapacitor [33], and catalytic support for various reactions [34,35,36].

Recent studies have explored the adsorption of antibiotics, including SMX and CIP, using biochar derived from different biomass classes. For instance, Ashebir et al. [37] investigated the biochar synthesized from the pyrolysis of Prosopis juliflora (PJ) to adsorb antibiotic residues, specifically SMX and CIP, from pharmaceutical sectors’ wastewater. The biochar exhibited remarkable characteristics, including a high BET surface area of 875 m2/g, diverse functional groups identified by FTIR, significant thermal stability as shown by TGA, an amorphous structure confirmed by XRD, a well-developed surface morphology observed through SEM, and a dominant carbon composition of 97% according to EDX analysis. These findings highlighted the potential and effectiveness of biochar as an adsorbent. The concentrations of CIP and SMX in actual wastewater were measured at 8.29 mg/L and 5.3 mg/L, with removal efficiencies of 80.4% and 76.7%, respectively. Hou and co-workers [38] reported a series of biochars with hierarchical pore structures synthesized from pyrolysis and chemical activation of wheat straw using ZnCl2 and assessed for their ability to adsorb SMX. The modified biochar showed notable improvements in specific surface area, pore volume, and adsorption efficiency (54-fold increase) compared to the unmodified biochar. Another study investigated the synergistic interactions of three (N)-containing sites on cow dung biochar surfaces for SMX adsorption. Results showed that the coexistence of pyridinic N and pyrrolic N significantly enhanced charge transfer to SMX, leading to stronger electrostatic attraction. These findings provided valuable insights into the role of active surface sites in improving the removal efficiency of contaminants [39]. Nguyen et al. [40] synthesized biochar from three types of algae, green algae (Ulva ohnoi), red algae (Agardhiella subulata), and brown algae (Sargassum hemiphyllum), using ZnCl2 as a chemical activator. These biochars were evaluated as long-term adsorbents for removing CIP from water. Among them, the activated biochar derived from brown algae (ZBAB) exhibited superior physicochemical properties, producing mesoporous structures with exceptional adsorption capacity ranging from 190 to 300 mg/g across varying conditions. Recent research suggests that tailoring biochar structures can help align with the specific properties of contamination. This includes developing appropriate porous texture, enhancing aromatization, and introducing doped heteroatoms and functional surface groups to enable effective contamination removal. Indeed, the adsorption of SMX and CIP onto biochar can be influenced by its structural variations, with mechanisms such as hydrogen bonding, complexation reactions, electrostatic attractions, and hydrophobic interactions potentially contributing to the process. The nature of biomass, the pyrolysis and activation processes conditions play a crucial role in refining biochar’s microstructure, as it enhances the availability of adsorption-active sites.

This study aims to fill the knowledge gap regarding the characteristics and performance of activated biochar from two different original biomasses (leather tannery waste and Sargassum macroalgae) for the first time, in the adsorption of SMX and CIP, in accordance with the principles of the circular economy and the upcycling concept. The biochars were prepared via pyrolysis of two biomasses followed by physical activation with CO2, which is considered an eco-friendly and efficient approach compared to the chemical activation technique. The obtained activated biochars were applied as adsorbents of pharmaceutical contaminants (CIP and SMX) in aqueous systems. The adsorption capacities of the two activated biochars were evaluated and compared to assess the impact of the type of original biomass and, thus, the physicochemical properties of the activated biochars on their sorption efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Two distinct biomasses were chosen for the preparation of biochar-based adsorbents: (a) tannery shaving waste (T) sourced from PASUBIO S.p.A. tannery (Arzignano, Italy), provided by GOAST technology, Green Organic Agents for Sustainable Tanneries (LIFE project, LIFE16 ENV/IT/000416); (b) Sargassum brown macroalgae (S) harvested from the Venice lagoon near the train station. Both biomass wastes have become environmental concerns in Italy.

2.2. Adsorbent Preparation

Before pyrolysis, biomass T was air-dried for 48 h, whereas biomass S was first washed with tap water and distilled water, then air-dried for 48 h and further dried in an oven at 110 °C for 2h. The biochars were prepared by slow pyrolysis of the biomasses in a fixed-bed quartz reactor, which was placed in a horizontal furnace. The setup included an electric heating system, thermocouples, a PID temperature controller, gas flow controllers from Brooks, a condensation trap in an ice bath for capturing liquid products (bio-oil), and an exit trap for bio-gas. About 40 g of biomass (size < 0.250 mm) was placed in the reactor, and pyrolysis was performed at 600 °C, with a heating rate of 5 °C/min, using a 100 mL/min flow of nitrogen lasting for 30 min. The produced biochars were labelled BT for leather tannery waste and BS for Sargassum brown macroalgae. The pyrolysis process produced three distinct products: gas (bio-gas), liquid (bio-oil), and solid (biochar). Slow pyrolysis was specifically chosen for this study to maximize the biochar yield, which was aimed to exceed 30% of the total product. After 30 min of pyrolysis, the temperature was gradually raised to 700 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min while maintaining a nitrogen flow of 100 mL/min. Subsequently, the gas was switched to CO2, which acted as the activation agent at a flow rate of 100 mL/min, and the activation process continued for 4 h. To eliminate inorganic residues (meaning ashes), the obtained activated biochar was treated with a 1 M HCl solution (Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) ≥37.0 wt%) and sonicated for 1 h. The mixture was then filtered, washed with deionized water until the pH was neutral, and dried in an oven at 110 °C for 12 h. Finally, the materials were ground and sieved to achieve a particle size of less than 180 μm. The resulting activated biochar adsorbents were labelled as ABT and ABS, respectively.

2.3. Characterization Techniques

The CHNS elemental compositions of the biomasses, biochars, and activated biochars were determined using a UNICUBE organic elemental analyzer (Elementar, Langenselbold, Germany). The inorganic residue content (ash) was quantified through thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using a TGA 8000 instrument (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) following the ASTM-D7582 protocol [41]. The oxygen content percentage was calculated using the following formula:

O (%) = 100 − (C% + H% + N% + S% + ash%)

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was conducted using a PerkinElmer Spectrum One spectrometer (Shelton, CT, USA). The analyses were carried out at room temperature with a wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1 and a resolution of 4 cm−1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was conducted using a LEO 1525 Field Emission Gun Scanning Electron Microscope (Oberkochen, Germany). Before imaging, samples were metalized with chromium. Images were captured using an In-lens detector, while the elemental composition was analyzed with a Bruker Quantax energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) system (Billerica, MA, USA).

The crystallinity, mineral phases, and structural order/disorder of the samples were analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (PW1769, Philips Analytical, Eindhoven, The Netherlands), (Malvern PANalytical Empyrean, 1.8 kW Cu Kα ceramic tube). The interlayer distance of graphitic layers (d002) is calculated by using the Bragg equation:

where λ is the wavelength of the X-ray beam.

λ = 2d002 sinθ

The specific surface areas and pore size distributions of the samples were determined through N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms measured at −196 °C using a Tristar II Plus Micromeritics instrument (MICROMERITICS, Norcross, GA, USA). The micropore and total surface areas were calculated using the t-plot and Langmuir methods, respectively. Additionally, the micropore volume was derived from the t-plot method, while the total pore volume was determined based on the nitrogen adsorbed at a relative pressure (P/Po) close to 0.98.

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

2.4.1. Batch Adsorption

Simple solutions of CIP and SMX were prepared at concentrations of 40–210 mg·L−1 and 80–550 mg·L−1, below which 100% adsorption was achieved by activated biochar. Batch adsorptions were performed by adding 2 mg of activated biochar to 5 mL of the solution and shaking on a horizontal bench shaker at 200 rpm in three replicates. The maximal absorption wavelengths of CIP and SMXS were 260 nm and 274 nm, respectively, as determined by a UV–vis spectrophotometer (UNICO, SQ-2800, Shanghai, China). Adsorption experiments were also conducted to determine the effects of dye concentration, contact time, temperature, and pH on the adsorptive removal of the dye by activated biochar. The removal percentage (%) and qe, which is the absorption capacity at equilibrium, and qt (the absorption capacities of predetermined intervals), were determined by Equations (1)–(3):

where C0, Ce and Ct are initial, equilibrium and time-dependent concentrations (mg L−1), respectively. V is the volume of drug solution (L), and m can be indicated as the mass of adsorbent (g).

%Drug removal = ((C0 − Ce)/C0) × 100

qe = ((C0 − Ce) V)/m

qt = ((C0 − Ct) V)/m

2.4.2. Adsorption Isotherm and Kinetic Study

The data were analysed at the equilibrium by four of the most traditional isotherm models (Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and Dubinin-Radushkevich isotherms) to analyse the adsorption process on activated biochar. The kinetic models, including Pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second order, and intraparticle diffusion, were applied to determine the best adsorption mechanism.

2.4.3. Regeneration Test

The regeneration tests of the adsorption of CIP and SMX over activated bio-char were performed at a temperature of 25 °C in eight cycles with C0 (CIP) = 80 ppm and C0 (SMX) = 80 ppm. Regeneration of the activated carbon was carried out using HNO3 (0.1 mol/L) as the desorbing agent. Initially, the adsorbent was recovered by centrifugation, and then regenerated using nitric acid. The adsorbent was subsequently washed multiple times with a mixture of ethanol and deionized water. Finally, it was dried at a temperature of 100 °C in an oven for 24 h.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Adsorbents Characterization

Table 1 presents the CHNS elemental analysis results for the biomasses, biochars, and activated biochars. The data reveal that the pyrolysis and activation processes resulted in elevated carbon content and reduced H/C ratios across all samples, indicative of carbonization and aromatization effects [42]. Looking at the activated biochars, ABT exhibited higher carbon contents, indicating its more aromatic, carbon-rich, and stable structures. The distribution of heteroatoms across the biochars was influenced by the original biomass type. The reduction in hydrogen content through treatments is attributed to the cracking and breaking of weak bonds within the carbonaceous framework of biomass and biochar [43]. Different trends of N, O, S percentages in two biomasses through pyrolysis and activation could demonstrate various strengths of C–N, C–O, S–O covalent bonds in the biomass and biochar structure being as functionalized or doped groups. In addition, both ABT and SBS showed significant nitrogen contents of 9.4% and 6.8%, respectively, derived from the protein content in T and S biomasses. Conversely, ABS has a notably higher sulfur content (2.8%) compared to the ABT, derived from the lipid fraction of algae. The presence of sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen heteroatoms suggests the incorporation of S, O, and N-doped and functional groups in the activated biochar, which are essential for enhancing the anchoring of antibiotic contaminants in absorbents. The higher ash content observed in ABS may be attributed to the presence of a higher amount of elements like Si (Figure S2), which remained unaffected by the acid-washing process [44]. Overall, the elemental distribution differed from one feedstock to the other, strongly influenced by the nature of the starting materials. These differences are related to the complexity of the biomass structures, which are made of different components (Carbohydrates, protein, and lipid in S, proteins, and vegetable tanning agents in T) that have different tendencies to cleavage at high temperatures. Studies in the literature revealed that self-doped and self-functionalized biochar with sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen groups could improve the hydrophilicity of biochar, which helped biochar expand in water, thereby boosting its adsorption performance. Additionally, the alterations in biochar’s electronic properties may enhance the electrostatic attraction between the biochar and antibiotic contaminants [45,46].

Table 1.

CHNS elemental analyses of biomasses, biochars, and activated biochars (The content of elements is reported in mass percentage).

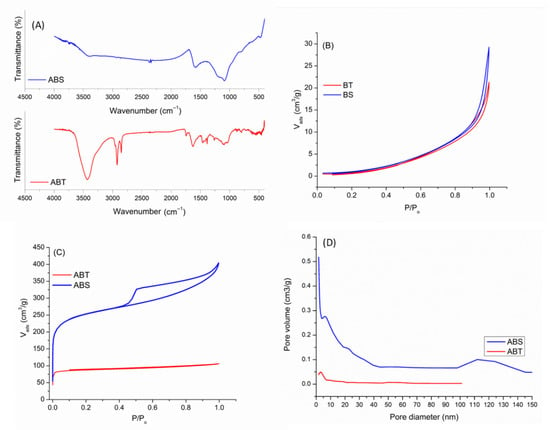

Figure 1A illustrates the FTIR spectra of ABT and ABS, highlighting the existence of multiple functional groups. The FTIR spectra of both samples exhibit a band around 3400 cm−1, attributed to the vibrations of hydroxyl functional groups [47]. The increased intensity of this band for ABT is associated with the vibrations of nitrogen-containing functional groups, specifically -NH2, derived from amines and amides, which originate from the protein components of the initial biomass sources. The band observed at 1600 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of aromatic C=C bonds and C=O bonds from conjugated ketones and quinones [48]. Furthermore, a broad peak within the range of 1400–900 cm−1 likely represents a combination of overlapping bands attributed to O-, N- based and S-based dopants and functional groups in both samples and ABS, respectively. These groups include C-O bonds in alcohols, phenols, and ethers, which form bridges between aromatic rings, N-COO and N-C groups, S=O in sulfuric acid, S–O in sulfonates, and SO2 in sulfonic acid and sulfones [35,49,50]. Moreover, both activated biochars display characteristic bands for C-H stretching vibrations of alkenes at 2850 and 2920 cm−1, along with out-of-plane aromatic C-H vibrations observed at approximately 800 cm−1 [51]. Overall, the FTIR spectra of the activated biochars varied, reflecting diverse functional groups, as supported by CHNS elemental analysis in Table 1, which revealed differing heteroatom contents. These differences are inherently linked to the distinct characteristics of the original biomass.

Figure 1.

(A) FTIR spectra of ABT and ABS adsorbents; N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of (B) BT and BS; (C) ABT and ABS; (D) Pore size distribution of ABT and ABS.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of two biochars and their activated counterparts are presented in Figure 1B,C. As is demonstrated in Figure 1B, the isotherms of the BT and BS biochars align with type III, characteristic of non-porous materials according to the IUPAC classification. These results underscore the substantial role that the original biomass plays in shaping the texture and characteristics of the resulting biochar. Indeed, this fact can be confirmed with studies in the literature in which the biochar obtained from some lignocellulosic biomasses, such as hazelnut shells and walnut shells, showed a porous texture with a high surface area [52,53], while the biochar obtained from plant leaves demonstrated a non-porous texture with a low specific surface area [54]. Furthermore, insufficient surface area and porosity can pose challenges to the adsorption process. To mitigate these limitations, an activation procedure was implemented to enhance the porosity and increase the surface area of the biochar-based materials.

As shown in Figure 1C, ABT demonstrated isotherms type I, indicating a texture dominated by micropores and a narrow hysteresis loop, displaying a limited number of mesopores. In contrast, the isotherm for ABS was a combined feature of types I and IV, characteristic of materials containing microporous and mesoporous structures, as classified by IUPAC. The sharp rise in gas adsorption at low relative pressures reflects the microporous nature typical of type I isotherms. Additionally, the hysteresis loop observed within the pressure range of 0.4 < p/po < 0.99 signifies the presence of mesopores and macropores. The H4 hysteresis loop indicates the presence of narrow slit-like pores in the ABS sample. In addition, pore size distribution of the adsorbents in Figure 1D confirms the micro-, meso- and macroporous nature for ABS and microporous texture for the ABT. Comparing the textural properties of two activated biochars indicates a higher Langmuir and microporous surface area, along with a higher pore volume for ABS (Table 2), which is expected to affect its performance in drug adsorption positively.

Table 2.

Textural properties of ABT and ABS activated biochars.

Figure S1 presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of ABT and ABS. Both materials display two main diffraction peaks at around 2θ ≈ 25° and 44°, which correspond to the (002) and (100) planes characteristic of turbostratic (hard) carbon structures. Using Bragg’s law, the interlayer spacings (d002) were determined to be approximately 0.351 nm for ABT and 0.357 nm for ABS, values larger than that of crystalline graphite (0.335 nm). This expanded d-spacing, together with the turbostratic disorder, indicates improved adsorption-related features such as facilitated mass transfer. Between the two activated biochars, ABS exhibits a slightly wider interlayer spacing, contributing to its superior adsorption performance. Additionally, sharp diffraction peaks appear in the patterns, attributed to residual inorganic phases including NaCl (ICSD-41439), likely originating from the HCl washing step, as well as crystalline SiO2 phases such as quartz (ICSD 83849) and tridymite (ICSD 176), commonly introduced from quartz reactor contamination [32,33].

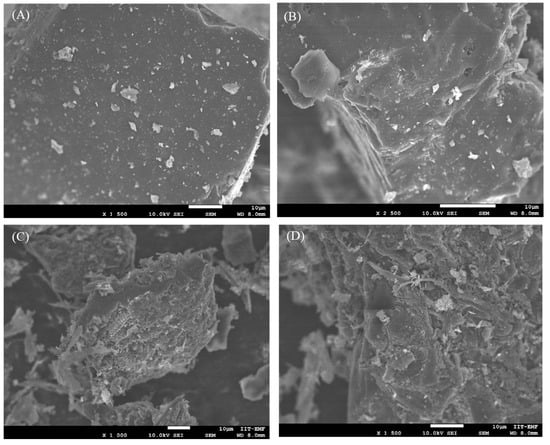

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was carried out to analyze the surface morphology of ABT and ABS (Figure 2). As depicted in Figure 2A,B, the SEM images of ABT reveal a flat surface with some porosity of various sizes. However, as was confirmed by N2-physisorption analysis, the majority of pores on the ABT surface are micropores, which are not detectable at the magnification used for the SEM images. In contrast, portions of the ABS surface display a beehive-like structure composed of interconnected pores and internal channels (Figure 2C,D). This morphology is reminiscent of biochars derived from lignocellulosic biomass, likely attributable to the carbohydrate content [35]. also characteristic of Sargassum brown macroalgae. Other regions of the ABS surface exhibit a rough, irregular porous texture, resulting in a heterogeneous structure linked to the elevated ash content observed in activated biomass-derived chars (Table 1).

Figure 2.

SEM images of (A,B) ABT and (C,D) ABS.

The energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectra and elemental mapping of ABT and ABS, presented in Figure S2A,B, reveal a uniform distribution of elements. The CHNS analysis (Table 1) confirms the presence of heteroatoms such as N, O, and S, which serve as dopants contributing to the functionalities of ABT and ABS derived from protein and collagen, and from protein, carbohydrate, and lipid-rich Tannery waste and Sargassum, respectively. Additionally, Figure S2 shows the distribution of these elements alongside C, Na, Cl, and Si for ABT and C and Si for ABS.

3.2. Adsorption Test

The purpose of this study is to compare the adsorption capacities of two activated biochars and to investigate how the origin and structural characteristics of the initial biomasses, derived from both animal-based industrial wastes and vegetal-based algal biomass sources across different generations, influence the properties and performance of the resulting activated biochars in removing pharmaceutical contaminants from aqueous systems.

3.2.1. Adsorption Isotherm

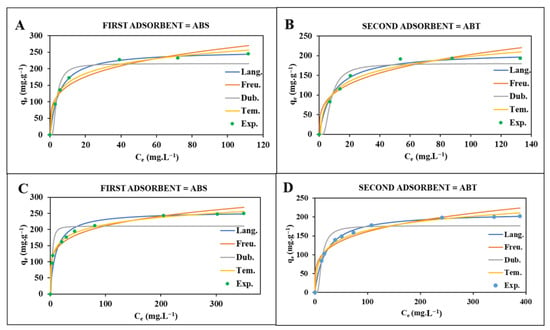

The equilibrium adsorption data for CIP and SMX on CO2-activated biochars (ABT and ABS) were analysed using four isotherm models: Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R), as shown in Table 3 and Figure 3. Among these models, the Langmuir model gave the best fit for all systems, with very high correlation coefficients (R2 > 0.997 in all cases). This indicates that the adsorption process can be well described by monolayer coverage on a surface with relatively uniform energy distribution, a characteristic often found in microporous carbon materials with consistent active sites.

Table 3.

Isotherms and their statistical parameters of CIP and SMX absorption on both adsorbents (T = 25 °).

Figure 3.

(A,B) the adsorption isotherms of, respectively, ABS and ABT for CIP (initial concentration = 40–210 ppm) at 25 °C and pH = 7.0 at equilibrium; (C,D) the adsorption isotherms of, respectively, ABS and ABT for SMX (initial concentration = 80–550 ppm) at 25 °C and pH= 7.0 at equilibrium. (Symbols: experimental data; solid lines: Langmuir model (Lang.), dashed lines: Freundlich model (Freu.), dotted lines: Temkin (Tem.) and Dubinin–Radushkevich (Dubin.)). Error bars represent ±5% relative error based on triplicate measurements).

The Langmuir maximum adsorption capacities (qm) show a consistent trend: ABS outperforms ABT for both antibiotics. For CIP, ABS reached a qm of 256.41 mg/g, compared to 210.13 mg/g for ABT. For SMX, ABS had a qm of 256.46 mg/g, while ABT had 213.00 mg/g. This is consistent with a higher performance of ABS compared to ABT and supports the presence of mesopores with high pore volume due to structural characteristics of macroalgae and their composition, suitable for the development of the pores during CO2 activation. This higher capacitance is in line with the texturalN2 physisorption analyzes (Table 2). ABS has a Langmuir surface area of 1305 m2/g, more than triple that of ABT (412 m2/g), and a much larger total pore volume (0.56 cm3/g and 0.16 cm3/g). The N2 adsorption/desorption isotherm of such a sample (Figure 1C) shows a mixture of type I and type IV isotherms and an H4 hysteresis loop, which is attributed to a well-developed network of micropores and slit-like mesopores. These hierarchical characteristics make ABS well-suited for adsorbing molecules like CIP and SMX, which contain planar aromatic systems and polar groups. In contrast, ABT displays a more typical type I isotherm with little hysteresis, suggesting it is mainly microporous with very few mesopores, which limits its ability to support diffusion.

Although the Langmuir model provided the best statistical fit (R2 > 0.997), indicating predominant monolayer coverage on relatively homogeneous energetic sites, the Freundlich and Temkin models also showed good correlation (R2 = 0.88–0.96 and 0.962–0.989, respectively), revealing additional important features of the adsorption process [55,56]. The Freundlich constant 1/n, ranging from 0.19 to 0.29 (all < 1), confirms highly favorable adsorption and reflects a certain degree of surface heterogeneity, especially pronounced in ABS due to its hierarchical micro–mesoporous structure and diverse heteroatom-containing functional groups (N, O, S) [56,57]. Higher K_F values for ABS than ABT further corroborate its stronger affinity and greater density of active sites [56]. The Temkin constant b_T (related to the heat of adsorption) ranged between 0.065 and 0.098 kJ/mol and was consistently higher for ABS, indicating stronger adsorbate–adsorbent interactions mediated by hydrogen bonding and π–π electron donor–acceptor interactions with oxygen- and sulfur-containing groups [56,58]. Finally, the mean free energy of adsorption (E) derived from the D–R model (0.25–0.50 kJ/mol) is far below 8 kJ/mol, confirming that physical forces (van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, and pore-filling mechanisms) dominate the process for both antibiotics on both biochars [56,59].

The Freundlich model was applied to fit the adsorption data of CIP and SMX on ABT and ABS, and 0.88 < R2 < 0.96, revealing that the adsorption is favorable. ABS exhibits higher Kf than ABT, probably due to its larger surface area and pore volume and stronger affinity towards both antibiotics. All n values are greater than 2 (from 3.49 to 5.22), indicating favorable and heterogeneous adsorption, and the adsorption isotherms are more favorable for ABS than for ABT and for SMX than for CIP, showing that the uptake tends to be more gradual, the distribution of the active sites is broader, and ABS has larger n values than ABT. This behavior is related to the presence of a complex micro-mesoporous system in the ABS, observed in the N2 isotherm of Figure 1C, permitting multi-interaction sites. The fairly good agreement of the Freundlich model with the Langmuir model indicates that the monolayer adsorption is predominant; however, there are some degrees of surface heterogeneity and varied interactive mechanisms (e.g., hydrogen bonding, π–π interactions, and pore filling). The higher values of Kf and n of SMX on both adsorbents can be explained by its more planar molecular configuration, which most likely allows a better penetration into the pores of these adsorbents and hence a better interaction with aromatic domains. When compared to literature values, the Kf values in this study are notably high, emphasizing the effectiveness of ABS as an adsorbent. The general persisting superiority of ABS over ABT throughout the Freundlich parameters confirms the dominating role of the feedstock source in governing an antibiotic adsorptive surface, and that the Sargassum seaweed was a more competitive source than tannery waste.

The Temkin isotherm model is based on the fact that the adsorption energy decreases in stages and is given linearly as a function of the adsorption coverage, either because of the adsorbate–adsorbate interactions or the surface heterogeneity. As can be seen from the R2 values (0.962–0.989), the data can be sufficiently described by the model, indicating that such an interaction is involved for CIP and SMX adsorption on two biochars (Table 3).

The higher A values for ABS against ABT reflect stronger binding, which is consistent with its larger surface area and higher density of functional groups. The B parameter, which correlates with the heat of adsorption, also favors stronger initial interactions on ABS.

The D-R isotherm model estimated mean adsorption energies (E) between 0.25 and 0.5 kJ/mol, which are well below the 8 kJ/mol threshold typically used to distinguish physisorption from chemisorption. This indicates that adsorption is primarily governed by physical forces, such as van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonding, rather than by chemical bonding or electron transfer. These weak, reversible interactions are characteristic of physisorption, which often occurs on porous carbonaceous materials like biochars. This interpretation is consistent with the high correlation coefficients observed in the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and with the Langmuir isotherm’s indication of monolayer adsorption, predominantly driven by physical adsorption mechanisms. Similar low E values have been reported in recent studies on antibiotic adsorption onto heteroatom-doped biochars, supporting that the adsorption process involves mostly non-specific interactions rather than chemisorption [60].

The molecular properties of the antibiotics also influence. At pH 7.0, CIP is zwitterionic (pKa1 ≈ 6.1, pKa2 ≈ 8.7), allowing it to form electrostatic links, hydrogen bonds, and π–π interactions with the biochar’s aromatic surfaces. SMX, being a weak acid (pKa ≈ 5.7), exists mostly as an anion under these conditions, which may reduce electrostatic attraction to the slightly negative or neutral surface of the biochars. However, its aromatic ring and sulfonamide group contribute to such π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding, facilitating high uptake, particularly when tested on ABS because of its higher surface area and electron-donating capacity for molecular interaction.

Heteroatoms like nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, identified through CHNS analysis (Table 1) and FTIR (Figure 1A), seem to improve the surface reactivity. In particular, ABS has lower nitrogen content (6.8%) than that of ABT (9.4%), but higher oxygen (7.9%) and significant sulfur (2.8%), presumably resulting in better polarity and hydrogen bonds. ABT, derived from protein-rich tannery scrap, showed additional nitrogen, of which some was lost through activation. These heteroatoms, also observed from elemental mapping (Figure S2), are evenly distributed, forming the active zones that enable polar interactions with the antibiotic molecules.

To contextualize the adsorption performance, Table 4 compares the maximum Langmuir capacities (qm) of ABT and ABS with those of other biochar adsorbents reported in the recent literature. ABS demonstrates markedly higher capacities than most unmodified or mildly modified biochars, affirming its efficacy for practical water treatment applications under eco-friendly preparation conditions.

Table 4.

Comparison of maximum adsorption capacities (qm, mg/g) for CIP and SMX using selected biochar adsorbents from the literature (conditions: ~25 °C, pH ~7 unless specified).

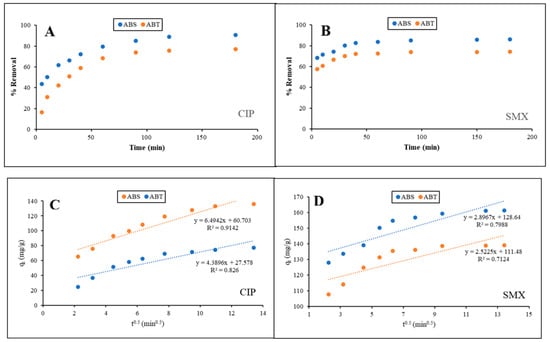

3.2.2. Adsorption Kinetics

The adsorption kinetics of CIP and SMX onto CO2-activated biochars derived from ABT and ABS were thoroughly studied to explore the mechanisms controlling the rate and the temporal dynamics of the process. As shown in Figure 4A,B, the removal of antibiotics increased rapidly in the initial period of contact for both antibiotics and adsorbents, followed by attaining equilibrium in the adsorption process. This rapid initial phase is ascribed to a large number of unoccupied active sites on the biochar surface, which only facilitated rapid external surface adsorptions. The adsorption kinetics decreased at the next stage due to saturation of sites and an increase in resistance to intraparticle diffusion. Equilibrium typically occurs within 180 to 240 min, which is indicative of the necessity for a sufficient contact time to achieve optimal removal, based upon the system. Table 5 summarizes the results for the pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), and intraparticle diffusion models. The PSO model provided the best fit. The high correlation coefficients (R2 > 0.997) and the close alignment between calculated and experimental equilibrium adsorption capacities (qe,calc ≈ qe,exp) point to a strong agreement. This indicates that chemisorption is the dominating rate-controlling process, which is caused by the interactions between the functional groups of the biochar surface and the ionizable parts of the antibiotics [66]. This result is consistent with previous studies of antibiotic adsorption by heteroatom-doped biochars and also suggests that surface complexation, π–π interaction, and hydrogen bonding played important roles in the adsorption process [31,67]. Comparing the PSO rate constants (k2) indicated that ABS presents a much faster adsorption kinetics in relation to ABT for both CIP and SMX. For instance, k2 for SMX adsorption on ABS is much greater than that on ABT, which is consistent with the steeper slope at the initial zone of the kinetic curves (Figure 4B). The enhanced kinetic behaviour is likely due to the better textural properties of ABS (higher specific surface area, larger pore volume and more developed mesoporous structure). These characteristics help in the rapid diffusion and availability of active sites. Marine seaweed, including Sargassum or Gracilaria, has a high abundance of fibrous polysaccharides, which cause a porous and defective carbon structure formed on pyrolysis and CO2 activation [68,69]. The faster adsorption rate of ABS is similar to our previous report on dye adsorption, in which activated biochar derived from Sargassum remarkably removed methylene blue and malachite green due to its high S/N content and mesoporous texture [31].

Figure 4.

The effect of contact time at 25 °C and pH = 7 on the content of (A) CIP (C0 = 60 ppm) and (B) SMX (C0 = 150 ppm) removal for both adsorbents in percentage; Plot of qt vs. t1/2 for adsorption of (C) CIP and (D) SMX dyes on both adsorbents to calculate kinetic constants (Kp, C, and R2) according to the Intraparticle diffusion model (qt = kpt1/2 + C). Symbols: experimental data; solid lines: pseudo-second-order model (PSO), dashed lines: pseudo-first-order (PFO). (C,D) Linear segments correspond to Stage I (film diffusion/surface adsorption), Stage II (intraparticle diffusion), and Stage III (equilibrium). (Error bars represent ±5% relative error based on triplicate measurements).

Table 5.

Kinetic models and other statistical parameters of CIP and SMX absorption on both adsorbents at 25 °C, pH 7.

The intraparticle diffusion model used to describe possible rate-controlling steps is shown in Figure 4C,D. The multi-linear features for either CIP or SMX confirm that adsorption occurs through multiple stages. The first linear segment represents rapid boundary layer diffusion or surface adsorption, the second slower intraparticle diffusion into meso- and micropores, and the third, the final equilibrium phase, characterized by pore saturation. Importantly, the lines do not cross through the origin, implying that intraparticle diffusion is not the only rate-controlling process, but that film diffusion (external mass transfer) is also important. The magnitude of the intercept (C) provides quantitative insight into the relative contribution of film diffusion: higher C values signify greater resistance from the boundary layer and/or stronger initial surface adsorption [11,68]. For instance, the large C values for SMX on ABS (C = 128.6) and ABT (C = 111.5) reflect rapid external surface uptake dominated by film diffusion in the first stage consistent with the steep initial slope in Figure 4B. The higher kp of ABS versus ABT (Table 5) further confirms its superior intraparticle mass transfer, enabled by its mesoporous network (Figure 1C, Table 2). This hierarchy of rate-controlling steps film diffusion (Stage I) → intraparticle diffusion (Stage II) → equilibrium (Stage III) is characteristic of adsorption on heterogeneous porous carbons and underscores the synergy between ABS’s textural and surface-chemical properties. ABS has higher intraparticle diffusion rate constants (kp) than ABT, which contributes to its improved mass transfer efficiency. Additionally, larger intercepts (C) of ABS indicate a larger surface adsorption contribution in the first stage, which is consistent with a higher mesoporous structure and surface functionality.

It is important to mention that SMX has faster uptake kinetics (as compared to CIP) in general on both adsorbents particularly at the initial concentration ≤ 100 mg/L, being due to its smaller molecular size (less steric hindrance) and pKa values, thus resulted in a minimum target surface coverage, which had the favorable necessary for diffusion and electrostatic interaction under the studied pH. This behavior is common in both kinetic and isotherm studies, which suggests that molecular configurations and diffusion capacity have obvious effects on adsorption.

3.2.3. Regeneration/Life Span of Activated Biochar Adsorbent

The economic feasibility and practical applicability of any adsorbent material for water remediation on an industrial scale are heavily dependent on its recyclability and long-term stability after multiple adsorption–desorption cycles. To assess the reusability of CO2-activated biochars (ABT and ABS), eight consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles were performed for both CIP and SMX under consistent experimental conditions (80 ppm, 25 °C, pH 7.0). As shown in Figure 5, both adsorbents displayed excellent regeneration performance, though their retention efficiency and decay profiles varied, which can be attributed to their unique textural and surface chemical properties.

Figure 5.

Reusability of both activated biochars in 8 cycles for CIP and SMX drugs. (The relative error of analysis was generally less than ±5%).

ABS consistently performed better than ABT, both in terms of how much it could initially adsorb and how well it held onto that adsorption over multiple cycles. After the first cycle, ABS’s efficiency for CIP was about 86%, and it continued to be above 75% after the eighth. Likewise, for SMX, it started strong with about 95% removal efficiency, slowly decreasing to about 80% by the eighth cycle. On the other hand, ABT showed a more noticeable decline: CIP removal dropped from around 74% in the first cycle to 61% in the eighth, and SMX adsorption fell from around 84% to 71% over the same period. The superior recyclability of ABS is linked to its well-developed micro–mesoporous structure, which supports higher initial uptake and makes it easier to release antibiotic molecules during regeneration. The slit-like mesopores (seen in the H4 hysteresis loop of the N2 isotherms in Figure 1C) help reduce pore blockage and facilitate better access for the desorbing agent (0.1 M HNO3), which aids in minimizing irreversible binding.

The progressive decline in adsorption efficiency of both adsorbents across cycles results from the incomplete desorption of residual antibiotic molecules that remain firmly attached to high-affinity sites, particularly those affected by hydrogen bonding, π–π interactions, or electrostatic forces associated with heteroatom-functionalized regions. This aligns with the pseudo-second-order kinetic model (Section 3.2.2), suggesting that the processes involved are characteristic of chemisorption, which depends on specific surface functionalities.

Additionally, it seems that reusability is a result of the stability of the carbon matrix itself. The highly aromatic and graphitic nature of the condensed carbon structure produced at high-temperature pyrolysis and subsequent CO2 activation imparts remarkable chemical and mechanical stability, ensuring no collapse in structure or leaching of functional groups after multiple cycles. Moreover, the higher ash content in ABS (14.2%, Table 1), mainly containing inorganic elements like Si, might also contribute to increased rigidity, thereby improving its long-term stability.

3.2.4. Effect of pH on Adsorption Capacity

Solution pH critically modulates adsorption by governing (i) the ionization state of antibiotic molecules and (ii) the net surface charge of the biochar. As experimentally determined (Figure 6B,D), ABT exhibits a high pHpzc (~9.0), consistent with its N-rich, protein-derived structure bearing abundant amine/amide groups; in contrast, ABS has a lower pHpzc (~7.2), reflecting its algal origin and higher content of acidic oxygen- and sulfur-containing groups (e.g., -COOH, -SO3H).

Figure 6.

(A,C) Effect of pH on the removal efficiency of CIP and SMX (C0 = 80 ppm), and (B,D) Determination of pHpzc for activated biochars. (The relative error of analysis was generally less than ±5%).

Ciprofloxacin (CIP) is amphoteric, with pKa1 = 6.1 (carboxyl) and pKa2 = 8.7 (piperazinyl), existing as CIP+ (pH < 6.1), zwitterionic CIP± (6.1–8.7), or CIP− (pH > 8.7). Sulfamethoxazole (SMX), a weak acid (pKa = 5.7), transitions from neutral SMX0 to anionic SMX- above pH 5.7.

The interplay between these equilibria and surface charge explains the observed trends: In acidic media (pH 3–5), both ABT and ABS surfaces are positively charged (pH < pHpzc), favoring electrostatic attraction of CIP+. SMX remains neutral and adsorbs via hydrophobic and H-bonding interactions. In near-neutral conditions (pH 6–8), CIP± adsorption remains high on ABS despite emerging negative surface charge (pH > 7.2), indicating that non-electrostatic forces, particularly π-π EDA interactions between its quinolone ring and biochar’s graphitic domains, plus H-bonding with -OH/-COOH groups, dominate over electrostatic repulsion. This aligns with recent findings by Sun et al. [45], which show that zwitterionic antibiotics maintain strong affinity for heteroatom-doped biochars even under charge-mismatched conditions. At alkaline pH (≥9), CIP- adsorption on ABS declines moderately (Figure 6A), as electrostatic repulsion intensifies, yet remains substantial (>65%), underscoring the resilience of dispersion-driven mechanisms. In contrast, SMX adsorption on ABS drops sharply above pH 8: here, both the adsorbent surface (net negative) and SMX (predominantly SMX−, α > 0.98) are anionic, leading to strong Coulombic repulsion. ABT, however, maintains high SMX uptake until pH ~9 (Figure 6C), as its surface stays near-neutral or slightly positive (pH < pHpzc ≈ 9.0), enabling electrostatic attraction or dipolar interaction with SMX−.

These patterns confirm that pH exerts a dual regulatory role: altering molecular speciation and interfacial charge. The dominance of physical adsorption (E = 0.25–0.5 kJ/mol, Table 3) further supports that non-electrostatic contributions (e.g., π–π, H-bonding, pore filling) often compensate for, or even override, electrostatic constraints, especially on high-surface-area, heteroatom-rich ABS. This mechanistic insight is consistent with recent biochar studies that emphasize the critical role of surface functionality over purely electrostatic interactions in antibiotic sequestration [39,40,70].

3.2.5. Mechanistic Insights into the Superior Performance of ABS over ABT

The superior performance of ABS over ABT is not solely due to its higher surface area and hierarchical micro–mesoporous structure, but is strongly amplified by differences in heteroatom content and the resulting surface polarity. ABS contains significantly higher sulfur (2.8 wt% vs. trace in ABT) and oxygen-containing functional groups (evidenced by higher O% after normalization and stronger FTIR bands in the 1400–900 cm−1 region), derived from the lipid-rich and carbohydrate fractions of Sargassum algae. Sulfur-doping introduces highly polar S=O, C–S–C, and sulfonic-like groups that dramatically enhance hydrogen bonding and dipole–dipole interactions with the polar moieties of both CIP (carbonyl, piperazine) and SMX (sulfonamide, amine, S=O) [39,45]. Recent studies have demonstrated that sulfur incorporation increases the electron-donor capacity and hydrophilicity of biochar, leading to stronger specific interactions with sulfonamide and fluoroquinolone antibiotics compared to undoped or N-rich biochars [26,39]. Conversely, ABT’s markedly higher nitrogen content (9.4 wt% vs. 6.8 wt% in ABS), originating from collagen/protein-rich tannery waste, provides abundant amine and amide groups that are more basic and therefore particularly effective for electrostatic attraction of anionic antibiotic species at alkaline pH (as discussed in Section 3.2.4) [38]. However, at neutral pH (where experiments were conducted), these N-sites contribute less to H-bonding strength than the O- and S-rich surface of ABS [39,49]. The synergistic combination in ABS of (i) hierarchical porosity for fast diffusion and high capacity, and (ii) elevated S/O heteroatoms for stronger non-electrostatic interactions (H-bonding, π–π EDA with electron-rich S/O sites) ultimately results in its superior qm, faster pseudo-second-order kinetics, and better reusability compared to the predominantly microporous, N-rich ABT [26,45].

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the effective adsorption of ciprofloxacin and sulfamethoxazole on biochars derived from leather tannery waste and Sargassum macroalgae, highlighting the influence of biomass origin, surface chemistry, and pore structure. The adsorption mechanisms predominantly involve physical interactions, including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and π-π interactions, as supported by isotherm and kinetic analyses. While these findings illustrate the potential of such biochars as sustainable adsorbents for pharmaceutical contaminants, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the study was conducted at a laboratory scale with controlled conditions; thus, the scalability and practical application in complex real wastewater systems require further investigation. Additionally, factors such as regeneration efficiency over extended cycles, impact of competing contaminants, and cost-effectiveness analyses merit future exploration to assess feasibility for large-scale water treatment applications. Addressing these aspects will strengthen the pathway toward real-world implementation and environmental impact mitigation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010280/s1. Figure S1: XRD patterns of ABT and ABS. Figure S2. EDX and elemental mapping of (A) ABT, and (B) ABS.

Author Contributions

S.J.: Supervision, Resources, Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Validation, Conceptualization. S.T.: Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Validation, Conceptualization. A.M.L.B.: Methodology, Data curation. M.S.: Writing—review and editing, Validation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available under a creative common license. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was financed by a research grant from the University of Mazandaran. Conceria Pasubio S.p.A, Arzignano, Italy is acknowledged for supplying leather shaving waste.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Jian, H.; Wang, C.; Xing, B.; Sun, H.; Hao, Y. Effect of Biochar-Derived Dissolved Organic Matter on Adsorption of Sulfamethoxazole and Chloramphenicol. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 396, 122598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Qiu, X.; Gao, J.; Ji, M. Adsorption of Sulfamethoxazole on Polypyrrole Decorated Volcanics over a Wide PH Range: Mechanisms and Site Energy Distribution Consideration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 283, 120165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Fazal, T.; Iqbal, J.; Din, A.A.; Ahmed, A.; Ali, A.; Razzaq, A.; Ali, Z.; Rehman, M.S.U.; Park, Y.K. Integrated Adsorptive and Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceutical Micropollutant, Ciprofloxacin Employing Biochar-ZnO Composite Photocatalysts. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 115, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Managaki, S.; Murata, A.; Takada, H.; Bui, C.T.; Chiem, N.H. Distribution of Macrolides, Sulfonamides, and Trimethoprim in Tropical Waters: Ubiquitous Occurrence of Veterinary Antibiotics in the Mekong Delta. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 8004–8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafaei, R.; Papari, F.; Seyedabadi, M.; Sahebi, S.; Tahmasebi, R.; Ahmadi, M.; Sorial, G.A.; Asgari, G.; Ramavandi, B. Occurrence, Distribution, and Potential Sources of Antibiotics Pollution in the Water-Sediment of the Northern Coastline of the Persian Gulf, Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, R.; Mesdaghinia, A.; Hoseini, S.S.; Yunesian, M. Antibiotics in Urban Wastewater and Rivers of Tehran, Iran: Consumption, Mass Load, Occurrence, and Ecological Risk. Chemosphere 2019, 221, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, J.; Mala, A.A. Removal of Antibiotic from the Water Environment by the Adsorption Technologies: A Review. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 82, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Cao, S.; Xi, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, G.; Chen, Z. A Novel Fe3O4/Graphene Oxide/Citrus Peel-Derived Bio-Char Based Nanocomposite with Enhanced Adsorption Affinity and Sensitivity of Ciprofloxacin and Sparfloxacin. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 121951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Z.H.; Xu, X.R.; Jiang, D.; Liu, J.J.; Kong, L.J.; Li, G.; Zuo, L.Z.; Wu, Q.H. Simultaneous Photocatalytic Cr(VI) Reduction and Ciprofloxacin Oxidation over TiO2/Fe0 Composite under Aerobic Conditions: Performance, Durability, Pathway and Mechanism. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 315, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tian, D.; Hu, J.; Shen, F.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Hu, Y. Fates of Hemicellulose, Lignin and Cellulose in Concentrated Phosphoric Acid with Hydrogen Peroxide (PHP) Pretreatment. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 12714–12723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Qiao, G.L.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y. Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters of Ciprofloxacin Adsorption onto Modified Coal Fly Ash from Aqueous Solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2011, 163, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.J.S.; El Kori, N.; Melián-Martel, N.; Del Río-Gamero, B. Removal of Ciprofloxacin from Seawater by Reverse Osmosis. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nariyan, E.; Aghababaei, A.; Sillanpää, M. Removal of Pharmaceutical from Water with an Electrocoagulation Process; Effect of Various Parameters and Studies of Isotherm and Kinetic. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 188, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalova, L.; Siegrist, H.; Singer, H.; Wittmer, A.; McArdell, C.S. Hospital Wastewater Treatment by Membrane Bioreactor: Performance and Efficiency for Organic Micropollutant Elimination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarahy, A.M.; Elwakeel, K.Z.; Mohammad, S.H.; Elshoubaky, G.A. A Critical Review of Biosorption of Dyes, Heavy Metals and Metalloids from Wastewater as an Efficient and Green Process. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M. Industrial Wastes as Low-Cost Potential Adsorbents for the Treatment of Wastewater Laden with Heavy Metals. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 166, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgariu, L.; Escudero, L.B.; Bello, O.S.; Iqbal, M.; Nisar, J.; Adegoke, K.A.; Alakhras, F.; Kornaros, M.; Anastopoulos, I. The Utilization of Leaf-Based Adsorbents for Dyes Removal: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 276, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamphile, N.; Xuejiao, L.; Guangwei, Y.; Yin, W. Synthesis of a Novel Core-Shell-Structure Activated Carbon Material and Its Application in Sulfamethoxazole Adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 368, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, H.; Johari, K.; Gnanasundaram, N.; Appusamy, A.; Thanabalan, M. Investigation of Green Functionalization of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes and Its Application in Adsorption of Benzene, Toluene & p-Xylene from Aqueous Solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Lin, Z.; Xiao, X.; Li, C.; Chen, Z. One-Step Biosynthesis of Hybrid Reduced Graphene Oxide/Iron-Based Nanoparticles by Eucalyptus Extract and Its Removal of Dye. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, G.; Pan, L.; Li, C.; You, F.; Wang, Y. Ciprofloxacin Adsorption by Biochar Derived from Co-Pyrolysis of Sewage Sludge and Bamboo Waste. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 22806–22817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Z. Application of Mg–Al-Modified Biochar for Simultaneous Removal of Ammonium, Nitrate, and Phosphate from Eutrophic Water. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, N.; Fang, Z. In Situ Remediation of Hexavalent Chromium Contaminated Soil by CMC-Stabilized Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron Composited with Biochar. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 1622–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroušek, J.; Strunecký, O.; Stehel, V. Biochar Farming: Defining Economically Perspective Applications. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Lim, J.E.; Zhang, M.; Bolan, N.; Mohan, D.; Vithanage, M.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Biochar as a Sorbent for Contaminant Management in Soil and Water: A Review. Chemosphere 2014, 99, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Feng, K.; Su, J.; Dong, J. The Mechanism of Cadmium Sorption by Sulphur-Modified Wheat Straw Biochar and Its Application Cadmium-Contaminated Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar Physicochemical Properties: Pyrolysis Temperature and Feedstock Kind Effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.S.; Park, S.H.; Jung, S.C.; Ryu, C.; Jeon, J.K.; Shin, M.C.; Park, Y.K. Production and Utilization of Biochar: A Review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.F.; Liu, S.B.; Liu, Y.G.; Gu, Y.L.; Zeng, G.M.; Hu, X.J.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.H.; Jiang, L.H. Biochar as Potential Sustainable Precursors for Activated Carbon Production: Multiple Applications in Environmental Protection and Energy Storage. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 227, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.; Norouzi, O.; Tavasoli, A.; Di Maria, F.; Signoretto, M.; Menegazzo, F.; Di Michele, A. Catalytic Conversion of Venice Lagoon Brown Marine Algae for Producing Hydrogen-Rich Gas and Valuable Biochemical Using Algal Biochar and Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 19918–19929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarian, S.; Bolouk, A.M.L.; Norouzian, R.S.; Taghavi, S.; Mousavi, F.; Kianpour, E.; Signoretto, M. Sargassum Macro-Algae-Derived Activated Bio-Char as a Sustainable and Cost-Effective Adsorbent for Cationic Dyes: A Joint Experimental and DFT Study. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 678, 132397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, P.; Tieuli, S.; Taghavi, S.; Venezia, E.; Fugattini, S.; Lauciello, S.; Prato, M.; Marras, S.; Li, T.; Signoretto, M.; et al. Sustainable Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Metal-Free Tannery Waste Biochar. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 4119–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Taghavi, S.; Bellani, S.; Salimi, P.; Beydaghi, H.; Panda, J.K.; Isabella Zappia, M.; Mastronardi, V.; Gamberini, A.; Balkrishna Thorat, S.; et al. Venice’s Macroalgae-Derived Active Material for Aqueous, Organic, and Solid-State Supercapacitors. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 496, 153529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.; Ghedini, E.; Peurla, M.; Cruciani, G.; Menegazzo, F.; Murzin, D.Y.; Signoretto, M. Activated Biochars as Sustainable and Effective Supports for Hydrogenations. Carbon Trends 2023, 13, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, L.; Taghavi, S.; Ghedini, E.; Menegazzo, F.; Di Michele, A.; Cruciani, G.; Signoretto, M. Selective Hydrogenation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural to 1-Hydroxy-2,5-Hexanedione by Biochar-Supported Ru Catalysts. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202200437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, L.; Taghavi, S.; Riello, M.; Ghedini, E.; Menegazzo, F.; Di Michele, A.; Cruciani, G.; Signoretto, M. Waste Biomasses as Precursors of Catalytic Supports in Benzaldehyde Hydrogenation. Catal. Today 2023, 420, 114038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashebir, H.; Nure, J.F.; Worku, A.; Msagati, T.A.M. Prosopis Juliflora Biochar for Adsorption of Sulfamethoxazole and Ciprofloxacin from Pharmaceutical Wastewater. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Bao, W.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; Chen, L.; Di, G.; Zhou, Q.; Li, X. Characteristics and Mechanisms of Sulfamethoxazole Adsorption onto Modified Biochars with Hierarchical Pore Structures: Batch, Predictions Using Artificial Neural Network and Fixed Bed Column Studies. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 54, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kong, L.; Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Li, N.; Yan, B.; Chen, G. New Insight into the Synergy of Nitrogen-Related Sites on Biochar Surface for Sulfamethoxazole Adsorption from Water. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Truong, Q.M.; Chen, C.W.; Chen, W.H.; Dong, C.D. Pyrolysis of Marine Algae for Biochar Production for Adsorption of Ciprofloxacin from Aqueous Solutions. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7582-15; Test Methods for Proximate Analysis of Coal and Coke by Macro Thermogravimetric Analysis. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Angin, D. Effect of Pyrolysis Temperature and Heating Rate on Biochar Obtained from Pyrolysis of Safflower Seed Press Cake. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 128, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thue, P.S.; Lima, D.R.; Lima, E.C.; Teixeira, R.A.; Dos Reis, G.S.; Dias, S.L.P.; Machado, F.M. Comparative Studies of Physicochemical and Adsorptive Properties of Biochar Materials from Biomass Using Different Zinc Salts as Activating Agents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Hu, C. Pyrolysis of High-Ash Natural Microalgae from Water Blooms: Effects of Acid Pretreatment. Toxins 2021, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Ji, L.; Cai, L.; Lu, S.; Li, R.; He, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, H. Multiple Defects Algal Biochar Derived from Ulva Lactuca with Enhanced Adsorption Performance for Ciprofloxacin. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 421, 126857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; Wei, G.; Fan, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Z.; Huang, X.; Wei, L. Super Facile One-Step Synthesis of Sugarcane Bagasse Derived N-Doped Porous Biochar for Adsorption of Ciprofloxacin. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa, J.M.; Paneque, M.; Miller, A.Z.; Knicker, H. Relating Physical and Chemical Properties of Four Different Biochars and Their Application Rate to Biomass Production of Lolium Perenne on a Calcic Cambisol during a Pot Experiment of 79 Days. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 499, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Huang, Y.; Nie, Z.; Qiu, X.; Su, D.; Wang, G.; Yuan, J.; Xie, X.; Wu, Z. Facile Synthesis of Camellia Oleifera Shell-Derived Hard Carbon as an Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 20424–20431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Zeng, Z.; Deng, S. Sulfonic Acid Functionalized Hydrophobic Mesoporous Biochar: Design, Preparation and Acid-Catalytic Properties. Fuel 2019, 240, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Luz Corrêa, A.P.; Bastos, R.R.C.; da Rocha Filho, G.N.; Zamian, J.R.; da Conceição, L.R.V. Preparation of Sulfonated Carbon-Based Catalysts from Murumuru Kernel Shell and Their Performance in the Esterification Reaction. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 20245–20256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Uchimiya, M. Comparison of Biochar Formation from Various Agricultural By-Products Using FTIR Spectroscopy. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2015, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfattani, R.; Shah, M.A.; Siddiqui, M.I.H.; Ali, M.A.; Alnaser, I.A. Bio-Char Characterization Produced from Walnut Shell Biomass through Slow Pyrolysis: Sustainable for Soil Amendment and an Alternate Bio-Fuel. Energies 2021, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.N.; Yildiz, Z.; Ceylan, S. Preparation and Characterisation of Biochar from Hazelnut Shell and Its Adsorption Properties for Methylene Blue Dye. Politek. Derg. 2018, 21, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutenaei, S.S.; Vatankhah, G.; Esmaeili, H. Ziziphus Spina-Christi Leaves Biochar Decorated with Fe3O4 and SDS for Sorption of Chromium (III) from Aqueous Solution. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 10251–10264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, É.C.; Adebayo, M.A.; Machado, F.M. Kinetic and Equilibrium Models of Adsorption. In Carbon Nanomaterials as Adsorbents for Environmental and Biological Applications; Carbon Nanostructures; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 33–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; You, S.J.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Chao, H.P. Mistakes and Inconsistencies Regarding Adsorption of Contaminants from Aqueous Solutions: A Critical Review. Water Res. 2017, 120, 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Zou, W.; He, F.; Hu, X.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Ok, Y.S.; Gao, B. Biochar Technology in Wastewater Treatment: A Critical Review. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Chen, H.; Gao, B. Ball Milled Biochar Effectively Removes Sulfamethoxazole and Sulfapyridine Antibiotics from Water and Wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Shen, Y. Generation of Microbial Protein Feed (MPF) from Waste and Its Application in Aquaculture in China. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccia, V.; Avena, M.J. On the Use of the Dubinin-Radushkevich Equation to Distinguish between Physical and Chemical Adsorption at the Solid-Water Interface. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 41, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadeen, H.M.; Elkhatib, E.A. New Nanostructured Activated Biochar for Effective Removal of Antibiotic Ciprofloxacin from Wastewater: Adsorption Dynamics and Mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2022, 210, 112929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Liu, G.; ur Rehman, M.Z.; Yousaf, B.; Ahmed, R.; Mian, M.M.; Ashraf, A.; Mujtaba Munir, M.A.; Rashid, M.S.; Naeem, A. Carbon Dioxide Activated Biochar-Clay Mineral Composite Efficiently Removes Ciprofloxacin from Contaminated Water—Reveals an Incubation Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 130079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, W.; Ma, L. Adsorption Behavior of Graphite-like Walnut Shell Biochar Modified with Ammonia for Ciprofloxacin in Aqueous Solution. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2025, 100, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Ali, A.; Su, J.; Liu, S.; Yan, H.; Xu, L. Removal of Sulfamethoxazole from Water by Biosurfactant-Modified Sludge Biochar: Properties and Mechanism. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, A.; Latifi, H.; Samani, K.M.; Fassnacht, F.E. Introducing a Computationally Light Approach to Estimate Forest Height and Fractional Canopy Cover from Sentinel-2 Data. J. Arid Environ. 2025, 228, 105343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Na, P.T.; Tuyen, N.D.K.; Dang, B.T. Sorption of Four Antibiotics onto Pristine Biochar Derived from Macadamia Nutshell. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 394, 130281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Huang, D.; Zheng, Q.; Yan, C.; Feng, J.; Gao, H.; Fu, H.; Liao, Y. Enhanced Adsorption Capacity of Tetracycline on Porous Graphitic Biochar with an Ultra-Large Surface Area. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 10397–10407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revellame, E.D.; Fortela, D.L.; Sharp, W.; Hernandez, R.; Zappi, M.E. Adsorption Kinetic Modeling Using Pseudo-First Order and Pseudo-Second Order Rate Laws: A Review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikuku, V.O.; Zanella, R.; Kowenje, C.O.; Donato, F.F.; Bandeira, N.M.G.; Prestes, O.D. Single and Binary Adsorption of Sulfonamide Antibiotics onto Iron-Modified Clay: Linear and Nonlinear Isotherms, Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Mechanistic Studies. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Xie, R.Y.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, X.J.; Li, B.; Xie, P.F.; Wu, C.F.; Jiang, L. Diamine-Appended Metal-Organic Framework for Carbon Capture from Wet Flue Gas: Characteristics and Mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 328, 125018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.