Estimating the Impact of Government Green Subsidies on Corporate ESG Performance: Double Machine Learning for Causal Inference

Abstract

1. Introduction

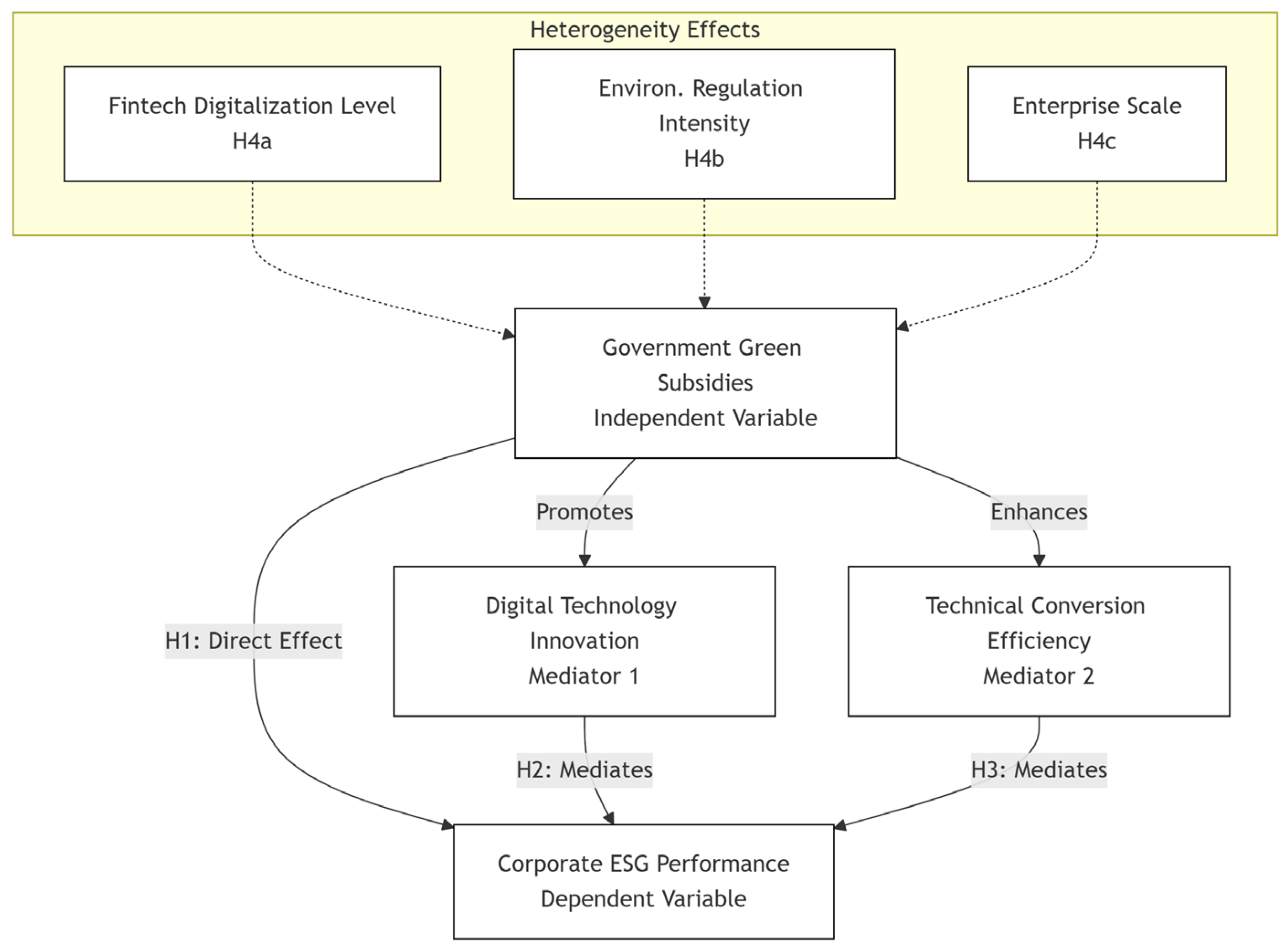

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Government Green Subsidies and Corporate ESG Performance

2.2. Mediating Effects

2.2.1. Digital Technology Innovation

2.2.2. Technical Conversion Efficiency

2.3. Heterogeneity Effects

2.3.1. Fintech Digitalization Level

2.3.2. Environmental Regulation Intensity

2.3.3. Enterprise Scale

3. Research Design

3.1. Variable Selection

3.1.1. Dependent Variable

3.1.2. Independent Variable

3.1.3. Mediating Variables

3.1.4. Control Variables

3.2. Models Specification

3.3. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Main Analysis

4.2. Roustness Tests

4.2.1. Changing the Dependent Variable

4.2.2. Excluding 2020 Data

4.2.3. Elimination of Extreme Values

4.2.4. Excluding Policy Shocks

4.2.5. Endogeneity Analysis

4.2.6. Reset the Double Machine Learning Models

5. Further Discussion

5.1. Mediating Effeccts

5.1.1. Digital Technology Innovation

5.1.2. Technical Conversion Efficiency

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.2.1. Fintech Digitalization Level

5.2.2. Environmental Regulation Intensity

5.2.3. Enterprise Scale

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Implications

6.2.1. Strategies for Policymakers

6.2.2. Strategies for Corporate ESG Officers

6.2.3. Strategies for Regulators

6.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Chen, P.; Hao, Y.; Dagestani, A.A. Tax incentives and green innovation—The mediating role of financing constraints and the moderating role of subsidies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1067534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, F.; Pizzi, S.; Lippolis, S. Sustainability reporting and ESG performance in the utilities sector. Util. Policy 2023, 80, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y. The Synergy Green Innovation Effect of Green Innovation Subsidies and Carbon Taxes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Mao, X.; Yu, X.; Yang, L. Government environmental protection subsidies and corporate green innovation: Evidence from Chinese microenterprises. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tong, Y.; Ye, F.; Song, J. The choice of the government green subsidy scheme: Innovation subsidy vs. product subsidy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4932–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yan, X. Impact of Government Subsidies, Competition, and Blockchain on Green Supply Chain Decisions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Tu, Y.; Li, Z. Enterprise digital transformation and ESG performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Feng, C.; Mirza, S.S.; Ahsan, T.; Qureshi, M.A. How uncertainty can determine corporate ESG performance? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2290–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, N.; Schiehll, E. The Effect of Financial Materiality on ESG Performance Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, M.; Dong, T.; Zhang, Z. Do ESG ratings promote corporate green innovation? A quasi-natural experiment based on SynTao Green Finance’s ESG ratings. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 87, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, R.A.; Khan, M.K.; Anwar, W.; Maqsood, U.S. The role of audit quality in the ESG-corporate financial performance nexus: Empirical evidence from Western European companies. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, S200–S212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, J. Does the Supervision Mechanism Promote the Incentive Effects of Government Innovation Support on the R&D Input of Agricultural Enterprises? IEEE Access 2021, 9, 3339–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, B. Machine Learning Algorithms—A Review. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 2020, 9, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cai, L. Digital transformation and corporate ESG: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Meng, L.; Zhang, J. Environmental subsidy disruption, skill premiums and ESG performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 90, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, A.; Robinot, É.; Trespeuch, L. Improving ESG Scores with Sustainability Concepts. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Xu, J.; Yuan, X. Sustainable Digital Shifts in Chinese Transport and Logistics: Exploring Green Innovations and Their ESG Implications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lyu, C. Can ESG Ratings Stimulate Corporate Green Innovation? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhu, Q. ESG performance and green innovation in a digital transformation perspective. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2024, 83, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Liu, G.; Cheng, S. How does ESG performance affect green transformation of resource-based enterprises: Evidence from Chinese listed enterprises. Resour. Policy 2024, 89, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Ma, D.; Sun, H. Green Agricultural Products Supply Chain Subsidy Scheme with Green Traceability and Data-Driven Marketing of the Platform. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Hu, K.; Nghiem, X.-H.; Acheampong, A.O. Urban climate adaptability and green total-factor productivity: Evidence from double dual machine learning and differences-in-differences techniques. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 350, 119588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, A.; Hansen, C.B.; Schaffer, M.E.; Wiemann, T. Model Averaging and Double Machine Learning. J. Appl. Econ. 2025, 40, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pan, W.; Yip, P.S.F.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, T. Uncovering the heterogeneous effects of depression on suicide risk conditioned by linguistic features: A double machine learning approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 152, 108080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Li, W.; Xiao, S. Does mixed ownership reform affect private firms’ ESG practices? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Financial Mark. Inst. Instrum. 2022, 31, 47–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.T.; Li, X. Too much of a good thing? Exploring the curvilinear relationship between environmental, social, and governance and corporate financial performance. Asian J. Bus. Ethic 2022, 11, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, C.; Albitar, K. ESG ratings and green innovation: A U-shaped journey towards sustainable development. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 4108–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hong, Z.; Long, H. Digital Transformation Empowers ESG Performance in the Manufacturing Industry: From ESG to DESG. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231204158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Ren, Z.; Ke, H. Green Housing Subsidy Strategies Considering Consumers’ Green Preference. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Jiang, Q.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Chen, Q. Corporate environmental governance and firm value: Beyond greenwashing for sustainable development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 21383–21400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, R.A.; Taran, A.; Khan, M.K.; Chersan, I.-C. ESG, dividend payout policy and the moderating role of audit quality: Empirical evidence from Western Europe. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2023, 23, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Liu, K.; Tao, Y.; Ye, Y. Digital finance and corporate ESG. Finance Res. Lett. 2022, 51, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Du, J.; Huang, M. Competition between Green and Non-Green Travel Companies: The Role of Governmental Subsidies in Green Travel. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Qiu, L.; She, M.; Wang, Y. Sustaining the sustainable development: How do firms turn government green subsidies into financial performance through green innovation? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 2271–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. Can Digital Transformation Promote Green Technology Innovation? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiao, S.; Bu, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Digital transformation and manufacturing companies’ ESG responsibility performance. Finance Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhu, B.; Sun, Y. Digitalization transformation and ESG performance: Evidence from China. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Li, Y.; Cao, L.; Hu, L.; Xu, B. Institutional Shareholders and Firm ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, J.; Ziru, A. Clients’ digitalization, audit firms’ digital expertise, and audit quality: Evidence from China. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2023, 31, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pan, Y.; Yang, W.; Ma, J.; Zhou, M. Effects of government subsidies on green technology investment and green mar-keting coordination of supply chain under the cap-and-trade mechanism. Energy Econ. 2021, 101, 105426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, S.C.; Fernández, F.R. Financial Digitalization: Banks, Fintech, Bigtech, And Consumers. J. Financ. Manag. Mark. Inst. 2020, 8, 2040001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, I.M.; Aysan, A.F. Fintech, Digitalization, and Blockchain in Islamic Finance: Retrospective Investigation. FinTech 2022, 1, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousrih, J. The impact of digitalization on the banking sector: Evidence from fintech countries. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2023, 13, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, S.; Ho, T.C. Digital technology, digital capability and organizational performance. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2019, 11, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Du, X.; Tu, W. Can corporate digital transformation alleviate financing constraints? Appl. Econ. 2024, 56, 2434–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K.; Abdoush, T.; Hussainey, K. Do corporate governance mechanisms and ESG disclosure drive CSR narrative tones? Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 28, 3876–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhong, M. Do ESG Ratings of Chinese Firms Converge or Diverge? A Comparative Analysis Based on Multiple Domestic and International Ratings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ge, Y. The Geopolitical Energy Security Evaluation Method and a China Case Application Based on Politics of Scale. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5682–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hu, M.; Dang, C.N. The Potential of Sino–Russian Energy Cooperation in the Arctic Region and Its Impact on China’s Energy Security. Sci. Program. 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zhao, S. On the green subsidies in a differentiated market. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 257, 108758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Boland, R.J., Jr.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A. Organizing for Innovation in the Digitized World. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 1398–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital Innovation Management: Reinventing Innovation Management Research in a Digital World. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIPO. Guide to the International Patent Classification; World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Wei, Y. Digital product imports and export product quality: Firm-level evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2023, 79, 101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Li, J. The Knowledge Spillover Effect of Multi-Scale Urban Innovation Networks on Industrial Development: Evidence from the Automobile Manufacturing Industry in China. Systems 2024, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénin, J.; Hussler, C.; Burger-Helmchen, T. New shapes and new stakes: A portrait of open innovation as a promising phenomenon. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2011, 7, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, S.; Laitala, E.; Kallio-Mannila, K. Evaluation of the Finnish action plan for the sustainable use of pesticides 2018–2022. Agric. Food Sci. 2023, 32, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purbasari, R.; Muhyi, H.A.; Sukoco, I. Actors and Their Roles in Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: A Network Theory Perspective: Cooperative Study in Sukabumi, West Java. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2020, 9, 240–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yu, Y.; Li, X. ESG performance, auditing quality, and investment efficiency: Empirical evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 948674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asante-Appiah, B.; Lambert, T.A. The role of the external auditor in managing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reputation risk. Rev. Account. Stud. 2022, 28, 2589–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.J.; Hoitash, R.; Hoitash, U. Auditor Response to Negative Media Coverage of Client Environmental, Social, and Governance Practices. Account. Horizons 2019, 33, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Suárez-Fernández, O.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Female directors and impression management in sustainability reporting. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manita, R.; Bruna, M.G.; Dang, R.; Houanti, L.’H. Board gender diversity and ESG disclosure: Evidence from the USA. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2018, 19, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in an emerging economy: Evidence from commercial banks of Kazakhstan. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 19, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Failler, P.; Chen, L. Can Mandatory Disclosure Policies Promote Corporate Environmental Responsibility?—Quasi-Natural Experimental Research on China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Michael, E.; Feller, A.; Rothstein, J. The Augmented Synthetic Control Method. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2021, 116, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Deng, Z.; Chen, M.; Yin, D.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zou, H.; Zhang, C.; Sun, C. Changes in Mental Health and Preventive Behaviors before and after COVID-19 Vaccination: A Propensity Score Matching (PSM) Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Demirer, M.; Duflo, E.; Hansen, C.; Newey, W.; Robins, J. Double/debiased machine learning for treatment and structural parameters. Econ. J. 2018, 21, C1–C68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, S.; Tibshirani, J.; Wager, S. Generalized random forests. Ann. Stat. 2019, 47, 1148–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knittel, C.R.; Stolper, S. Machine Learning about Treatment Effect Heterogeneity: The Case of Household Energy Use. AEA Pap. Proc. 2021, 111, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-C.; Chuang, H.-C.; Kuan, C.-M. Double machine learning with gradient boosting and its application to the Big N audit quality effect. J. Econ. 2020, 216, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, D.P.D.; Hsu, Y.; Hartauer, C.; Hartauer, A. Investigating the Interconnection between Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG), and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Strategies: An Examination of the Influence on Consumer Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lau, S.; Liu, S.S.; Hu, Y. How Firm’s Commitment to ESG Drives Green and Low-Carbon Transition: A Longitudinal Case Study from Hang Lung Properties. Sustainability 2024, 16, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; You, X.; Xu, T. Sustainable Supplier Evaluation: From Current Criteria to Reconstruction Based on ESG Requirements. Sustainability 2024, 16, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Quan, M.; Li, H.; Hao, X. Is environmental regulation works on improving industrial resilience of China? Learning from a provincial perspective. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 4695–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, Y. An Evolutionary Game Analysis on Green Technological Innovation of New Energy Enterprises under the Heterogeneous Environmental Regulation Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Wang, L.; Wu, J. Environmental Regulations, Green Technology Innovation, and High-Quality Economic Development in China: Application of Mediation and Threshold Effects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, M.-M.; He, L.-Y. Environmental Regulation, Environmental Awareness and Environmental Governance Satisfaction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Yuan, J.; Xiao, D.; Chen, Z.; Yang, G. Research on environmental regulation, environmental protection tax, and earnings management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1085144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Li, W.; Wang, D. Analysis on current situation of China’s intelligent connected vehicle road test regulations. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 259, 02003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Ahmad, M.; Rjoub, H.; Kalugina, O.A.; Hussain, N. Economic growth, renewable energy consumption, and ecological footprint: Exploring the role of environmental regulations and democracy in sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xue, H. An Analysis of the Dimensional Constructs of Green Innovation in Manufacturing Enterprises: Scale Development and Empirical Testing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, I.; Joseph, M.; Francis, D. Enterprise Risk Management Practices and Survival of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Nigeria. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2020, 15, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffour, J.K.; Amoako, A.A.; Amartey, E.O. Assessing the Effect of Financial Literacy Among Managers on the Performance of Small-Scale Enterprises. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2022, 23, 1200–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, S.M.; Shafiullah, M.; Hasan, A.; Gazder, U.; Al Mamun, A.; Mansoor, U.; Kashifi, M.T.; Reshi, O.; Arifuzzaman, M.; et al. Energy Demand of the Road Transport Sector of Saudi Arabia—Application of a Causality-Based Machine Learning Model to Ensure Sustainable Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, B. Revisiting residential self-selection and travel behavior connection using a double machine learning. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 128, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Y. Can companies get more government subsidies through improving their ESG performance? Empirical evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Chadha, G.; Singhania, M. ESG Measurement: An Interdisciplinary review using Scientometric Analysis. Int. J. Manag. Financ. Account. 2025, 1, 205–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, E.; Paolucci, G. Board Diversity and ESG Performance: Evidence from the Italian Banking Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. A Review of ESG Performance as a measure of stakeholder’s theory. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2023, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Han, J.; Yuan, H. Urban digital economy development, enterprise innovation, and ESG performance in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 955055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yin, T. Resource Bundling: How Does Enterprise Digital Transformation Affect Enterprise ESG Development? Sustainability 2023, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, F. Transformational Leadership, Organizational Innovation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from SMEs in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | 2337 | 4.9276 | 0.9436 | 2.25 | 6.75 |

| Subsidy | 2337 | 14.7674 | 3.4312 | 0 | 19.0947 |

| Lev | 2337 | 0.5542 | 0.2247 | 0.074 | 0.9363 |

| Age | 2337 | 2.4304 | 0.7178 | 0 | 3.3673 |

| Growth | 2337 | 0.197 | 0.4998 | −0.6888 | 2.6055 |

| OC | 2337 | 0.367 | 0.1659 | 0.0838 | 0.733 |

| Board | 2337 | 2.2314 | 0.2455 | 1.6094 | 2.7081 |

| Indep | 2337 | 0.3848 | 0.0591 | 0.3333 | 0.5714 |

| Balance | 2337 | 0.4317 | 0.297 | 0.026 | 0.9953 |

| Institution | 2337 | 0.6487 | 0.207 | 0.0976 | 0.9338 |

| DTI | 2337 | 3.1221 | 2.2419 | 0 | 8.3354 |

| TCE | 2337 | 0.0409 | 0.0464 | 0.0002 | 0.2814 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| Subsidy | 0.0816 *** | 0.0793 *** | 0.0667 *** | 0.0675 *** | 0.0513 *** |

| (5.426) | (5.414) | (4.433) | (4.360) | (3.361) | |

| _cons | 0.0035 | 0.0038 | −0.0221 | −0.0204 | −0.0237 |

| (0.230) | (0.246) | (−1.529) | (−1.445) | (−1.642) | |

| CV First-order | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CV Second-order | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Obs | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| Subsidy | 0.0361 *** | 0.0228 *** | 0.0411 *** | 0.0289 *** | 0.0207 * | 0.0134 ** | 0.0144 ** | 0.0136 ** | 0.1825 ** |

| (4.4507) | (3.2687) | (4.9545) | (3.9192) | (1.8834) | (2.110) | (2.479) | (2.486) | (2.463) | |

| _cons | 0.0085 | −0.0338 * | −0.0063 | 0.0143 | −0.0489 ** | −0.027 * | −0.036 ** | −0.027 * | −0.025 |

| CV First-order | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CV Second-order | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 | 1312 | 2070 | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 |

| Variable | Sample Splitting Ratio 1:9 | Gradient Boosting | Lasso Regression | Ensemble Machine Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| ESG | ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| Subsidy | 0.0131 ** | 0.0232 *** | 0.0138 *** | 0.0151 *** |

| (2.2114) | (4.2547) | (2.9627) | (3.3568) | |

| _cons | −0.0273 * | −0.0064 | −0.0316 ** | −0.0186 |

| (−1.8157) | (−0.3851) | (−2.2823) | (−1.3776) | |

| CV First-order | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CV Second-order | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTI | ESG | TCE | ESG | |

| Subsidy | 0.2346 *** | 0.0338 ** | 0.0005 *** | 0.0503 *** |

| (9.0115) | (2.0390) | (2.8017) | (3.1038) | |

| DTI | 0.0788 *** | |||

| (5.4654) | ||||

| TCE | 1.4800 *** | |||

| (2.9236) | ||||

| _cons | 0.0059 | −0.0204 | 0.0004 | −0.0269 * |

| (0.2796) | (−1.3979) | (0.8864) | (−1.7800) | |

| CV First-order | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CV Second-order | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 | 2337 |

| Variable | Low | Medium | High |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| Subsidy | −0.0092 | 0.0450 *** | 0.0286 *** |

| (−0.8653) | (4.3804) | (3.3681) | |

| _cons | −0.0520 ** | −0.0271 | −0.0274 |

| (−2.0093) | (−0.9263) | (−1.0189) | |

| CV First-order | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CV Second-order | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 780 | 780 | 777 |

| Variable | Low | Medium | High |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| Subsidy | 0.0287 *** | 0.0152 * | 0.0282 ** |

| (3.6138) | (1.8069) | (2.4945) | |

| _cons | −0.0273 | −0.0236 | −0.0290 |

| (−1.0738) | (−0.7556) | (−1.0380) | |

| CV First-order | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CV Second-order | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 834 | 741 | 762 |

| Variable | Low | Medium | High |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| ESG | ESG | ESG | |

| Subsidy | 0.0339 *** | 0.0001 | 0.0046 |

| (3.2211) | (0.0144) | (0.7142) | |

| _cons | −0.0043 | −0.0110 | −0.0010 |

| (−0.1599) | (−0.4100) | (−0.0393) | |

| CV First-order | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CV Second-order | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Enterprise FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 779 | 779 | 779 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, Y.; Hizam-Hanafiah, M.; Fahmi Ghazali, M.; Ab Razak, R.; Zheng, Y. Estimating the Impact of Government Green Subsidies on Corporate ESG Performance: Double Machine Learning for Causal Inference. Sustainability 2026, 18, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010281

Cao Y, Hizam-Hanafiah M, Fahmi Ghazali M, Ab Razak R, Zheng Y. Estimating the Impact of Government Green Subsidies on Corporate ESG Performance: Double Machine Learning for Causal Inference. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010281

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Yingzhao, Mohd Hizam-Hanafiah, Mohd Fahmi Ghazali, Ruzanna Ab Razak, and Yang Zheng. 2026. "Estimating the Impact of Government Green Subsidies on Corporate ESG Performance: Double Machine Learning for Causal Inference" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010281

APA StyleCao, Y., Hizam-Hanafiah, M., Fahmi Ghazali, M., Ab Razak, R., & Zheng, Y. (2026). Estimating the Impact of Government Green Subsidies on Corporate ESG Performance: Double Machine Learning for Causal Inference. Sustainability, 18(1), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010281