Abstract

The urban heat island (UHI) effect, intensified by rapid urbanization, necessitates the precise identification and mitigation of thermal sources and sinks. However, existing studies often overlook landscape connectivity and rarely analyze integrated source–sink networks within a unified framework. To address this gap, this research combines source–sink theory with the local climate zone classification to examine the spatiotemporal patterns of thermal characteristics in Fuzhou, China, from 2016 to 2023. Using morphological spatial pattern analysis, the minimum cumulative resistance model, and a gravity model, we identified key thermal source and sink landscapes, their connecting corridors, and barrier points. Results indicate that among built-type local climate zones, low-rise buildings exhibited the highest land surface temperature, while LCZ E and LCZ F were the warmest among natural types. Core heat sources were primarily LCZ 4, LCZ 7, and LCZ D, accounting for 19.71%, 13.66%, and 21.72% respectively, whereas LCZ A dominated the heat sinks, contributing to over 86%. We identified 75 heat source corridors, mainly composed of LCZ 7 and LCZ 4, along with 40 barrier points, largely located in LCZ G and LCZ D. Additionally, 70 heat sink corridors were identified, with LCZ A constituting 96.39% of them, alongside 84 barrier points. The location of these key structures implies that intervention efforts—such as implementing green roofs on high-intensity source buildings, enhancing the connectivity of cooling corridors, and performing ecological restoration at pinpointed barrier locations—can be deployed with maximum efficiency to foster sustainable urban thermal environments and support climate-resilient city planning.

1. Introduction

Currently, global urbanization is accelerating. Projections indicate that another 2.5–4 °C increase is possible by the end of the 21st century in high emissions scenarios [1]. As a result, key factors contributing to the urban heat island effect include reduced surface albedo, diminished vegetation cover, and decreased evapotranspiration in cities, alongside a marked increase in anthropogenic waste heat emissions [2,3,4,5].

The accurate assessment of UHI intensity is not merely a climatological concern but is critically linked to the built environment, as it directly governs the estimation of building energy demand. For instance, a data-driven study by Tehrani et al. demonstrated that UHI conditions significantly elevate the cooling load intensity in residential buildings, underscoring the necessity of integrating UHI effects into urban energy models for reliable predictions [6]. Furthermore, empirical analyses in cities like Rome have quantified substantial variations in heating and cooling energy demands—up to 36.5% and 81%, respectively—between urban and rural zones, directly attributable to UHI intensity differences [7]. Therefore, accurately assessing UHI intensity is crucial for predicting changes in building energy demand [8]. Consequently, it has become a focal point of research for scholars across disciplines, including urban climatology, ecology, geography, and medicine [9].

The source–sink theory, originally developed for studying air pollution and carbon cycles, has been increasingly adopted in urban climate studies, particularly for analyzing thermal environments [10,11]. In this framework, landscapes are categorized as thermal sources if they intensify urban heat, whereas thermal sinks alleviate it. Researchers have identified different land-use/land-cover (LULC) types as thermal source and sink landscapes. They have examined their spatial characteristics and influencing factors. These studies demonstrate the effectiveness of applying the source–sink theory in urban heat island research. The source–sink theory thus helps mitigate UHI effects. It does so by guiding the strategic allocation of different landscape types in space, particularly in urban environments where land resources are extremely scarce [12,13].

Although notable progress has been made in UHI studies grounded in source–sink theory, some shortcomings remain. First, many analyses have assessed how landscape patterns affect UHI using metrics and diversity of landscape patches. These patches are often considered separately and do not fully capture the landscape’s overall connectivity. Finally, prior efforts have built cooling networks using conventional land-use categories, which restricts the precision of the resistance surface [14]. Significant differences persist in the thermal environments of impervious surfaces across different urban morphologies and functional landscapes [15].

Urban climates possess significant spatiotemporal complexity, which necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the urban thermal environment to inform both climate research and urban planning [16]. Based on the LCZ system, Yan et al. investigated the impact of various urban forms on canopy UHI under regional climatic conditions [17]. Caterina et al. updated the spatial characterization of the Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI) in Tarragona using multi-sensor remote sensing data within a Local Climate Zone (LCZ) framework [18]. Studies consistently show that the environmental profile of less affluent neighborhoods—encompassing local climate, livability, heat accumulation, pollution, and power demands—differs substantially from that of other city zones [19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

To explicitly address the research gap and outline our contribution, this study aims to develop an integrated framework that combines Source–Sink Theory with the Local Climate Zone (LCZ) scheme. The primary objectives are: (1) to precisely identify thermal source and sink landscapes in Fuzhou, China, from 2016 to 2023 based on spatiotemporal LST variations across LCZ types; (2) to construct thermal environment networks by integrating Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA), the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model, and a gravity model, thereby identifying key source areas, corridors, and barrier points for both heat source landscapes and heat sink landscapes; and (3) to propose targeted mitigation strategies for optimizing the urban thermal environment. The “pattern identification–process simulation–network regulation” framework developed in this study effectively addresses three critical issues: first, it compensates for the insufficient attention to landscape connectivity in traditional thermal environment research; second, it overcomes the limitations of single urban form analysis; third, it bridges the methodological gap from static identification to dynamic regulation. By treating LCZ patches as nodes and their thermal interactions as connections, this integrated approach not only accurately identifies key areas and pathways for heat island mitigation but also provides an innovative decision-support tool for precise urban heat island diagnosis and climate-resilient urban planning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

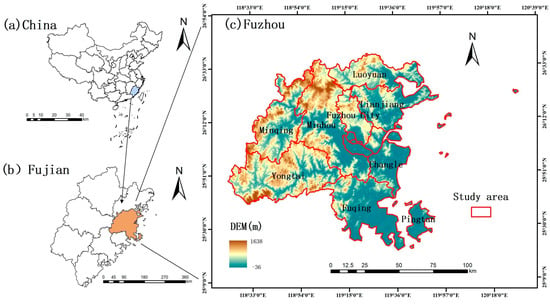

Fuzhou is the provincial capital of Fujian Province, located in the central-eastern part of Fujian (Figure 1), between latitudes 25°15′ N and 26°39′ N and longitudes 118°08′ E and 120°31′ E. The city covers an area of 11,968.53 km2 and administers six districts: Gulou, Cangshan, Taijiang, Mawei, Jin’an, and Changle, along with six counties—Luoyuan, Minqing, Yongtai, Pingtan, Lianjiang, and Minhou—and the city of Fuqing. Fuzhou’s topography is characteristic of a river delta basin, comprising plains, hills, and mountain ranges. The annual average precipitation ranges from 900 to 2100 mm [26]; The annual average temperature ranges from 20 to 25 °C. The coldest months are January and February, with average temperatures reaching 6 to 10 °C. The hottest months are July and August, with average temperatures of 33 to 37 °C. The highest recorded temperature reached 42.3 °C. In 2013, Fuzhou was ranked as the most sweltering city among China’s four major ‘furnaces’, frequently experiencing the urban heat island effect. Its basin-like topography contributes to midday temperatures exceeding 36 °C during summer. Consequently, this study selects Fuzhou City as its research area.

Figure 1.

Study Area.

2.2. Data

To meet requirements for imaging consistency and high-quality imagery, this study employs Landsat 8 Land Imager and thermal infrared sensor data to investigate the thermal environment patterns in Fuzhou during summer. The remote sensing data originates from the United States Geological Survey website (http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov; (accessed on 15 April 2025)), with cloud cover consistently below 5% and imaging periods corresponding to Fuzhou’s summer months (June to August).

Additionally, this paper employs high-resolution historical imagery from Google Earth Pro to extract training samples. Road density data is sourced from the China dataset of OpenStreetMap, elevation data (Digital Elevation Model, DEM) utilizes the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) digital elevation model, and slope information derived from the DEM.

2.3. Methods

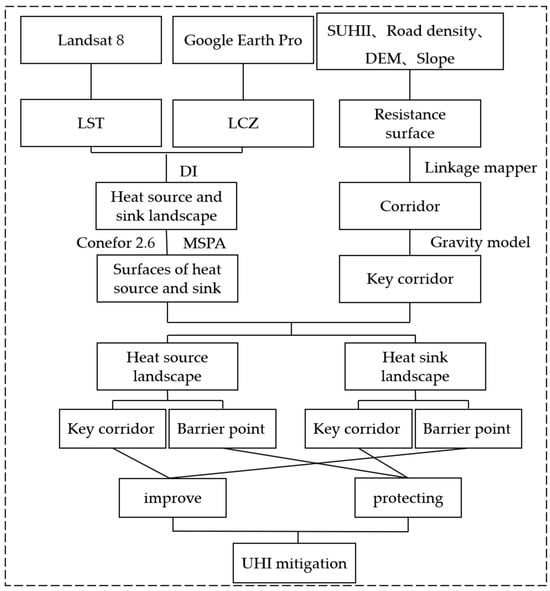

The specific steps include the following: (1) LST was inverted from pre-processed remote sensing imagery of Fuzhou City using the radiative transfer equation method. LCZ was classified using training samples from Google Earth Pro, and LCZ types were categorized as heat source landscapes and heat sink landscapes through the distribution indices. (2) MSPA analysis was conducted using Guidos 3.2 and plaque significance analysis using Confer 2.6. (3) A resistance surface was built using SUHII, Road Density, DEM, and Slope Information. The MCR model in Linkage Mapper was used to locate corridors, and the importance of these corridors was assessed with a gravity model. (4) The Barrier Mapper tool in Linkage Mapper 3.0 was utilized to detect barrier points for both heat source and heat sink landscapes. The specific process is shown in Figure 2. The heat island effect in the study area can be lessened by safeguarding barrier points in heat source landscapes and improving corridors and surface areas in heat sink landscapes, together with enhancing barrier points in heat sink landscapes and corridors/surface areas in heat source landscapes.

Figure 2.

Schematic flowchart for this study.

2.3.1. LST Retrieval

In this study, land surface temperature (LST) inversion was carried out on preprocessed Landsat-8 images using the radiative transfer equation approach.

(1) The radiative transfer equation method achieves LST inversion by utilizing radiation measurements from a thermal infrared channel and atmospheric profile data, as expressed by the following formula:

In the equation, Ts represents the actual surface temperature; B(Ts) denotes the blackbody radiance value; K1 and K2 are calibration constants. K1 is 774.89 m2·sr·μm and K2 is 1321.08 K.

(2) The blackbody radiance value is determined according to the following mathematical expression:

Blackbodies possess strong radiative capabilities, and thus are commonly used as reference standards for calculating the thermal radiation intensity of other substances. In the equation, τ represents atmospheric transmittance, L↑ denotes upward radiant flux, L↓ indicates downward radiant flux, and ε signifies the surface emissivity.

(3) Calculate the Surface Emissivity (ε)

Based on previous research, remote sensing imagery is categorized into three types: water bodies, urban areas, and natural surfaces. This study employs the following methodology to calculate the surface emissivity of the study area: Water pixel emissivity is assigned a value of 0.995. The emissivity of natural surface and urban pixels is estimated using the following equations:

In the equation, εsurface and εbuilding represent the specific emissivity of natural surface pixels and urban pixels, respectively; FV denotes the vegetation coverage.

(4) Calculate the vegetation cover fraction (FVC)

The vegetation cover fraction (FVC) is calculated using a hybrid pixel decomposition method, which broadly classifies land types in the entire scene image into water bodies, vegetation, and buildings. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula, NDVI denotes the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, while NDVImin and NDVImax represent the minimum and maximum NDVI values within the study area, respectively.

2.3.2. Classification of Local Climate Zones

An LCZ map is a classification map generated for a city or specific study area using satellite remote sensing [25,26,27] or GIS data [28,29,30] visualizing the surface morphology and local climate of the study area. Depending on the data source and analytical method, LCZ classification is primarily categorized into three approaches: manual sampling, remote sensing, and GIS mapping [29]. Manual sampling primarily involves collecting urban landscape samples through on-site fieldwork. This method is not only time-consuming and labor-intensive, but variations among different sampling operators may also introduce bias into the results. Consequently, manual sampling has yet to gain widespread application in the compilation of LCZ classification maps [30]. Landsat imagery for Fuzhou City was downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) for the years 2016, 2020, and 2023, ensuring cloud coverage is below 5%. The classification methodology adopted by this research institute follows the process outlined below:

- (1)

- Pre-process the downloaded remote sensing imagery and resample its pixel size from 30 m to 100 m to represent spectral signals consistent with the local climate classification scale.

- (2)

- Acquire high-resolution historical imagery of Fuzhou City for the years 2016, 2020, and 2023 via Google Earth Pro 7.3.6, and manually delineate training areas for each year. Each LCZ type shall comprise 10 training samples uniformly distributed.

- (3)

- Using Landsat 8 remote sensing imagery and training samples, a Random Forest (RF) method was employed within SAGA-GIS to generate the LCZ classification map.

- (4)

- Generate a random set of evaluation points within ArcGIS 10.5. Calculate the Kappa coefficient for the LCZ classification results by determining the Overall Accuracy (OA) and generating a confusion matrix, thereby assessing the precision of the LCZ classification outcomes.

For the reliability of this classification method, when manually sketching training samples on Google Earth Pro, we ensured that there were at least 10 samples per LCZ type Table 1, and these samples were evenly distributed throughout the study area in space to avoid geographical bias. Each sample is accurately interpreted based on clear morphological features (such as building density, height, vegetation cover type) in high-resolution images. The random forest algorithm itself has good robustness to noise data and overfitting, and can process high-dimensional data and evaluate the importance of features, which provides a stable classification basis for this study. In addition, it is necessary to evaluate the overall accuracy (OA) of the classification results and calculate the Kappa coefficient according to the confusion matrix.

Table 1.

Definitions of local climate zones.

2.3.3. Identifications of Heat Source and Sink Landscapes

The study mapped the heat source and heat sink landscapes for the years 2016, 2020, and 2023. Following methodologies in previous studies [31,32,33], the land surface temperature (LST) was categorized into five classes (Table S1). Areas falling into the high-temperature and sub-high-temperature categories were defined as high-temperature zones. The distribution index (DI) was determined according to the following mathematical expression:

where DI is the distribution index, S is the total area of the study region (Fuzhou City), Sh is the total area of the high-temperature and sub-high-temperature types in LST classification, Si is the total area of the i-th LCZ type, and Sih is the total area of the high-temperature and sub-high-temperature types within the i-th LCZ type.

2.3.4. Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis

MSPA provides a robust approach for analyzing the geometric and structural attributes of spatial patterns, enabling the identification of connectivity features within landscape imagery [34]. The seven MSPA categories are defined in Table S2. Among these, the core category has been shown to significantly affect the SUHII [35]. Consequently, this research designated core areas as the surface representations for both heat sources and sinks. The MSPA was performed using Guidos Toolbox 3.2, applying an 8 neighborhood rule and setting the edge width to 1 pixel.

2.3.5. Spatial Connections

Spatial connections describe how landscape patches either facilitate or hinder ecological flows [35,36]. Connectivity analysis commonly employs a suite of indices to assess the contribution of individual nodes to overall landscape connectivity [37]. Thus, this study utilized Conefor 2.6 software to calculate the IIC and PC values, thereby evaluating the functional importance of individual thermal source and sink patches. The calculation of the IIC and PC indices necessitates the determination of a distance threshold. Building upon prior research, this study employs the distance gradient method to determine distance thresholds, utilizing four metrics to evaluate the scale effects generated by different distance thresholds. Results indicate that when the distance threshold is set at 1400, all metrics for 2016, 2020, and 2023 exhibit a plateau phase (Figure S1). The min-max scaling technique was applied to adjust the IIC and PC metrics to a common numeric range, each assigned a weighting of 0.5, thereby constructing a composite importance index for Fuzhou’s thermal source and sink landscapes. The 30 areas with the highest composite importance indices were selected as key source locations. The IIC and PC indices are defined by the following mathematical expressions:

where n is the number of patches within the heat source or heat sink landscape; ai and aj are the areas of patches i and j, respectively; nlij is the number of shortest paths between patches i and j; AL is the maximum area among all patches within the heat source or heat sink landscape; P*ij is the maximum product probability of all paths connecting patches i and j within the heat source or heat sink landscape.

2.3.6. Construction of Resistance Surface

The resistance surface represents the spatial variation in impedance that the landscape structure imposes on heat flow processes. Drawing on established methodologies [35,36,37,38,39,40], in the LCZ assessment, the following parameters received these proportions of influence: 0.70 for urban heat island intensity, 0.15 for traffic corridor density, and 0.075 each for terrain height and steepness (Table 2).

Table 2.

Resistance values of heat source and sink landscapes in Fuzhou in 2023.

A higher SUHII value for an LCZ class implies lower resistance for heat source landscapes but higher resistance for heat sink landscapes traversing that area. Road density approximates anthropogenic heat, with vehicles and urban infrastructure being its direct sources [14]. Consequently, in our model, higher road density values correspond to increased resistance for heat source landscapes and decreased resistance for heat sink landscapes. Areas at higher elevations generally experience stronger winds and cooler air temperatures [40]. Therefore, higher DEM values were assigned greater resistance for heat source landscapes and lower resistance for heat sink landscapes. Steeper slopes can hinder the exchange of latent heat between source and sink areas. Accordingly, steeper slopes were assigned higher resistance values for heat source movement and lower resistance for heat sink movement. The calculation of SUHII is performed as follows:

where SUHIILCZ X is the SUHII of LCZ X, LSTLCZ X is the LST of LCZ X, and LSTLCZ D is the LST of LCZ D.

2.3.7. Definition of Corridors and Source Landscape

In this study, corridors for both heat source and heat sink landscapes were delineated using the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model. The concept of resistance surfaces originated in ecology to model the movement barriers species face. It is now extensively applied to identify potential corridors, including those for urban thermal processes [14].

where Dij is measured as the separation between landscapes i and j (heat source or sink), and Ri quantifies the resistance coefficient opposing ecological flows for landscape i.

A gravity model was subsequently used to quantify the interaction strength between node pairs and determine the comparative impact of the identified corridors within the thermal landscape networks. The magnitude of this interaction reflects the corridor’s potential effectiveness and ecological importance [41]. The gravitational model formula employed in the study is as follows:

The gravitational interaction Gab is calculated for thermal landscape patches a and b, with pa and pb indicating their respective friction coefficients, and Sa and Sb their sizes. Here, Lab is the total friction along the least-cost path between them, and Lmax the maximum such value among all possible connections.

2.3.8. Identification of Barrier Points

Using the constructed resistance surfaces and identified corridors, the Barrier Mapper tool in Linkage Mapper 3.0 was applied to pinpoint areas that significantly impede corridor quality or alter optimal pathways. The modification or removal of these barrier points has the potential to substantially improve the connectivity and functional efficiency of the corridors. Therefore, a strategic approach for mitigating the SUHI effect involves preserving barrier points located within heat source landscapes, while improving or removing those found within heat sink landscapes.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial–Temporal Variation Analysis of Temperature Based on LCZ Classification

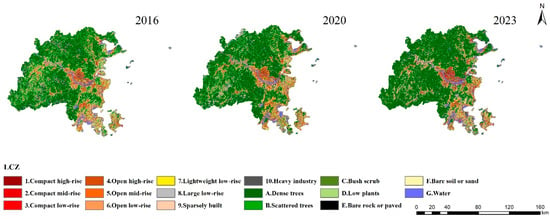

An initial LCZ mapping output was generated through the application of the random forest method. These were compared with contemporaneous high-resolution imagery from Google Earth Pro, and the training samples were appropriately adjusted. This ultimately yielded the final LCZ classification map (Figure 3). Using Google Earth Pro, samples for validation were obtained from the same period. Employing random sampling, 3000 randomly generated sampling points were validated, yielding final overall accuracies for each year of 66.03% (Table S3), 60.85% (Table S4), and 64.53% (Table S5), with Kappa coefficients for each year of 0.6302 (Table S3), 0.6085 (Table S4) and 0.6136 (Table S5).

Figure 3.

LCZ classification of study area.

Combining the area changes across LCZ types (Table 3) reveals that among building types, LCZ 9 experienced the most significant reduction in area, decreasing by 135.8 km2, while LCZ 1 exhibited the largest increase, growing by 120.7 km2. Regarding building height, the low-rise building types LCZ3, LCZ6, LCZ7, and LCZ8 all experienced area reductions, decreasing by 76.52 km2, 17.56 km2, 60.02 km2, and 50.43 km2, respectively, with a total area reduction of 204.53 km2. Among mid-to-high-rise buildings, LCZ 1, LCZ 2, and LCZ 5 increased by 120.7%, 17.55%, and 59.97%, respectively, totaling 108.55 km2, while LCZ 4 decreased. In terms of building density, the combined area of high-density building types LCZ 1, LCZ 2, and LCZ 3 increased by 61.73 km2, while the combined area of open-plan building types LCZ 4, LCZ 5, and LCZ 6 decreased by 47.26 km2. The replacement of some open-plan buildings by high-density structures indicates a denser building layout within the study area. Among natural cover types, LCZ A increased by 1514.15 km2, whilst LCZ B, LCZ C, and LCZ D decreased by 626.07 km2, 121.35 km2, and 689.53 km2, respectively. This indicates a transition in vegetation cover from low, sparse vegetation towards dense woodland within the study area. The areas of LCZ E, LCZ F, and LCZ G increased by 1.96 km2, 13.16 km2, and 105.88 km2, respectively, with annual change rates of 27.18%, 1.91%, and 2.34%. Among these, the increase in water area was particularly significant, while changes in the other types were relatively minor.

Table 3.

LCZ area changes in study area from 2016 to 2023.

3.2. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Air Temperature Variations Based on LCZ Types and Source–Sink Landscape Classification

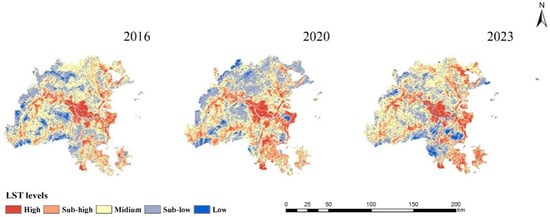

Surface temperature inversion was performed using remote sensing data, with LST maps classified into temperature categories via the mean-standard deviation method. This yielded a surface temperature classification map for Fuzhou City covering the period 2016–2023 (Figure 4). High-temperature zones predominantly concentrate in the central urban area, which comprises built-up zones including commercial districts, industrial zones, and residential areas characterised by high population density.

Figure 4.

Surface Temperature Classification Map.

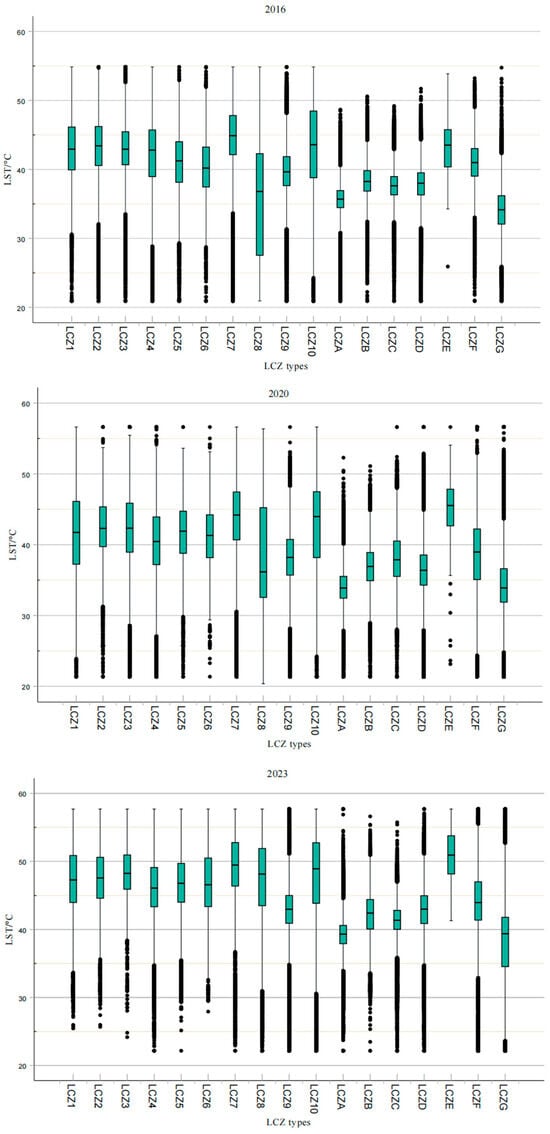

Statistical distributions and LST box plots for each LCZ were made through overlay analysis (Figure 5, Table 4). Within built-up areas, low-rise buildings excluding large structures exhibited the highest average LST (LCZ7 (45.69 °C), LCZ10 (44.36 °C), LCZ3 (44.34 °C)), while building types with sparse, open structures exhibited the lowest average LST (LCZ9 (40.15 °C), LCZ8 (40.07 °C)). Densely built-up areas generally recorded higher average LST than sparsely built-up areas. Regarding natural cover types, LCZ E (46.22 °C) and LCZ F (40.47 °C) exhibited the hottest average LST, while LCZA (36.12 °C) and LCZG (35.80 °C) recorded the coldest. LCZE demonstrated the fastest LST increase rate; its LST could be mitigated by planting trees on bare ground. Regarding LST distribution across LCZ types, LCZA, LCZB, LCZC, and LCZD exhibited the smallest internal surface temperature variations and highest homogeneity.

Figure 5.

LST distribution box diagram.

Table 4.

LST Statistics from the LCZ Perspective.

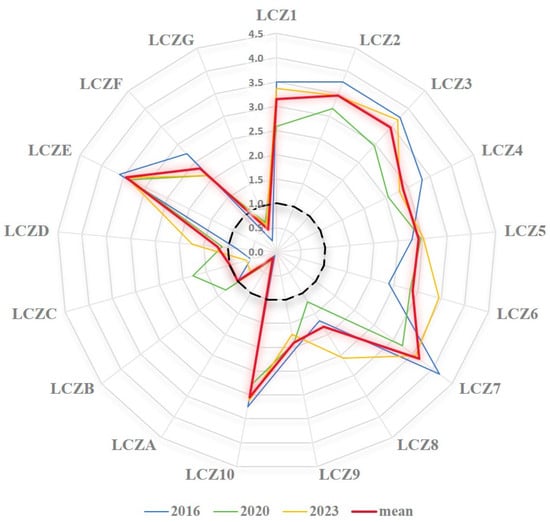

Based on Fuzhou’s LCZ for 2016, 2020 and 2023, DIs for each LCZ type in Fuzhou during these years were calculated (Table 5, Figure 6). This indicates that the distribution of heat sources and sinks across LCZ types in Fuzhou remained largely consistent throughout 2016, 2020 and 2023. Therefore, this study employs the average value method for the distribution indices of each LCZ type across 2016, 2020, and 2023. It identifies LCZ A, LCZ B, LCZ C, and LCZ G—whose average distribution indices are all below 1—as heat sink landscapes, while the remaining LCZ types with average indices above 1 are classified as heat source landscapes.

Table 5.

DIMEAN of LCZ types.

Figure 6.

Pie Charts of DI Values for Each LCZ Type in 2016, 2020, and 2023.

3.3. Analysis of MSPA and Connectivity

Table 6 analyzes and reveals the dynamic characteristics of thermal environment network evolution: Between 2016 and 2020, the IIC and PC of thermal source landscapes decreased at rates of 25.76% and 37.11%, respectively. From 2020 to 2023, the decline accelerated further to 30.86% and 33.41%, indicating an accelerating trend of fragmentation. Conversely, heat sink landscapes achieved rapid growth of 45.13% and 59.53% during 2016–2020. Although growth rates slowed slightly from 2020 to 2023, they remained high at 43.34% and 38.11%, indicating the significant and sustained effectiveness of cooling network construction.

Table 6.

Network Connection Metric Change Rate.

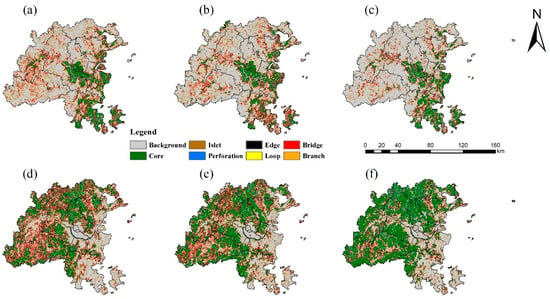

Figure 7 presents the analysis of distribution patterns and connectivity. Findings indicate that heat source landscapes predominantly occur in the city’s core and its southeastern quadrant, whilst heat sink landscapes are primarily distributed across the western and northern zones. Statistical analysis of MSPA results (Table 7) indicates that the predominant LCZ types within the core heat source landscape are LCZ 4, LCZ 7 and LCZ D. Their respective areas over the three years were 300.64 km2, 208.35 km2 and 331.21 km2, accounting for 19.71%, 13.66% and 21.72% of the core heat source area. The LCZ types of core heat sink landscapes encompassed LCZA, LCZB, LCZC, and LCZG, with LCZA occupying the largest proportion. Over the three years, it accounted for 86.28%, 91.36%, and 91.17% of the total core heat sink area respectively. The MSPA results map indicates dense forestation in Fuzhou’s outer urban districts, contributing significantly to heat sink landscapes. Connectivity analyses of core heat source and sink landscapes in 2016, 2020, and 2023 identified 30 key source areas in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

MSPA analysis results for heat source landscapes and heat sink landscapes in Fuzhou City across different years (2016, 2020, and 2023): (a), (b), and (c) represent the MSPA analysis results for heat source landscapes in Fuzhou City for 2016, 2020, and 2023 respectively; (d), (e), and (f) represent the MSPA analysis results for heat sink landscapes in Fuzhou for 2016, 2020, and 2023 respectively.

Table 7.

MSPA statistics of heat source and sink landscapes (km2).

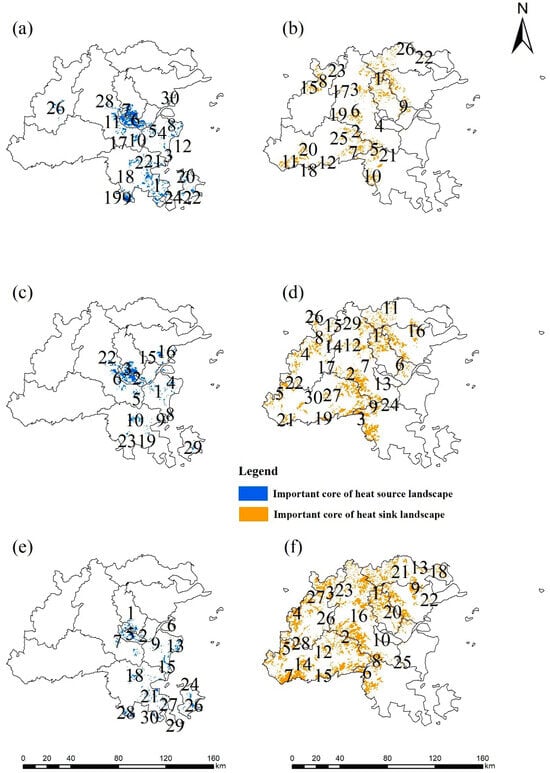

Figure 8.

Connectivity analysis results for heat source and heat sink landscapes in Fuzhou City across different years (2016, 2020, and 2023): (a), (c), and (e) represent connectivity analysis results for heat source landscapes in Fuzhou City for 2016, 2020, and 2023 respectively; (b), (d), and (f) represent the connectivity analysis results for heat sink landscapes in Fuzhou for 2016, 2020, and 2023 respectively.

The area of thermal bridges within the heat source landscape decreased significantly from 956.2 km2 to 593.39 km2 between 2016 and 2023. This indicates a heightened fragmentation of thermal radiation pathways and increased heat island fragmentation, facilitating heat accumulation within isolated zones. Conversely, the pore area within heat sink landscapes surged from 234.6 km2 to 510.1 km2, while connecting bridge areas plummeted from 1542.43 km2 to 605.32 km2. This signifies the severing of heat sink landscape corridors, where forest fragmentation has isolated heat sink landscapes into islands. Consequently, urban cooling capacity diminishes, amplifying the urban heat island effect. This phenomenon demonstrates that heightened aggregation of LCZ types driving surface temperature increases directly reflects urban spatial expansion and evolving surface temperature patterns. It signifies a phase transition in the urban heat island effect, shifting from ‘discrete patches’ to ‘regional linkage’.

Data from 2023 was employed in the further examination.

3.4. Key Sources, Corridors and Barriers for Heat Sources and Heat Sinks in Landscapes

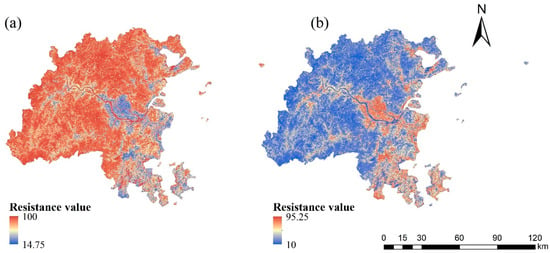

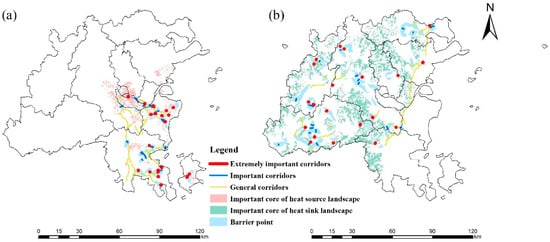

Utilising LCZ data including SUHII, road density, DEM and slope, a resistance surface for thermal source–sink landscapes in Fuzhou was established (Figure 9). Based on key source and sink locations alongside the resistance surface, Linkage Mapper 3.0’s MCR algorithm was applied to detect corridors for both thermal source and sink landscapes. Gravity models were then employed to identify critical corridors (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

The resistance surface: (a) represents the heat source landscape; (b) Indicates the heat sink landscape.

Figure 10.

The important sources, corridors and barrier points: (a) represents the heat source landscape; (b) represents the heat sink landscape.

The analysis detected precisely 75 linkages spanning the thermal source areas, spanning a combined length of 563.85 km. The majority are concentrated within the central urban area, with a smaller portion extending southeast towards the coastline. The predominant landscape corridor types are LCZ 7 and LCZ 4, accounting for 21.96% and 29.25% respectively. Within the heat sink landscape, 70 corridors were identified with a combined length of 350.81 km. These are predominantly distributed across the western and northeastern regions, with LCZ A constituting the primary LCZ type, accounting for a substantial 96.39% of the total.

Using the Barrier Mapper within Linkage Mapper 3.0, barrier points were extracted for both heat source landscapes and heat sink landscapes. 40 barrier points were identified within the heat source landscape, primarily comprising LCZ G and LCZ D, accounting for 22.50% and 17.50% respectively. Within the heat sink landscape, 84 barrier points were extracted, predominantly comprising LCZ A, LCZG, LCZC, and LCZD. Among these, LCZ A accounted for 36.90%, while LCZ 9, LCZ C, and LCZ D collectively constituted 14.29%, with LCZ G representing 9.52%.

4. Discussion

4.1. Core Contributions of an Integrated LCZ and Source–Sink Framework for Modeling Urban Thermal Networks

In general, expanding vegetation and water body coverage is considered the most efficient approach for reducing the urban heat island effect [15,42]. Pointing and optimizing pivotal zones for mitigating the urban heat island effect is vital for attaining the most effective thermal environment enhancement tactics in cities. In this paper, the resistance surface results vary from earlier studies, as previous resistance surfaces mainly relied on restricted LULC classes, comprising impervious surfaces, forests, grasslands, water bodies, croplands, and bare land [35,40,43].

This study categorises land resources into built and natural cover types, comprehensively considering factors such as building density, height, surrounding environment, and vegetation types. It establishes SUHII as the primary factor influencing the resistance surface within LCZ types. Methods for constructing corridors and identifying key nodes are commonly employed in research on biodiversity, species migration, and ecological security patterns. This study achieves a fundamental transcendence of the traditional LCZ research paradigm through innovative methodological integration. While early research primarily focused on analyzing temperature characteristics and statistical relationships across different LCZ categories, our work introduces three fundamental shifts: from static morphological classification to dynamic functional process analysis, treating LCZ units as landscape components with clear thermodynamic functions (sources or sinks); from isolated patch research to interactive network analysis, revealing heat transmission pathways and critical corridors between LCZ patches through thermal environment network construction; and from macro-level problem diagnosis to precise intervention planning, with our method capable of identifying key nodes and barrier points that decisively influence the overall thermal environment, providing urban planning with targeted mitigation strategies that traditional LCZ analysis cannot achieve.

Heat flow within urban thermal environments constitutes a dynamic, diffusive process. Different land use types influence thermal conditions through their absorption and reflection of radiation, as well as through interactions between adjacent land use types. Land use and land cover (LULC) is the dominant factor influencing the urban thermal environment. Hence, utilizing the combined principles of microclimate categorization and transfer theory to examine urban heating structures and formulate intervention measures demonstrates both utility and reliability.

4.2. Implications for Adaptation Strategy Development

Research findings indicate that among all LCZ types, LCZ2, LCZ3, LCZ7, LCZ10 and LCZE exhibit higher SUHII values, while LCZ G, LCZ A, LCZ D, LCZ C and LCZ B demonstrate lower SUHII. As larger impervious surface areas yield poorer cooling effects, high-SUHII heat-source landscapes within urban areas can be segmented into smaller patches by interposing low-SUHII heat-sink landscapes [44]. Conversely, excessively small heat sink landscapes may diminish heat island mitigation efficacy. Therefore, heat sink landscapes (particularly within urban areas) should be appropriately expanded and their connectivity enhanced to improve cooling effects. Ecological conduits are of fundamental importance for enhancing biological mobility and environmental interactions, whereas barriers impede these movements and processes. Therefore, based on the results of in-depth analysis of the thermal environmental ecological network, barriers within heat source landscapes and corridors within heat sink landscapes should be protected. At the same time, proactively eliminating obstructions in cooling zones and optimizing connectivity channels within heat-emitting areas are key measures for alleviating urban overheating and boosting thermal regulation.

The thermal source landscape corridors in Fuzhou City are primarily distributed across Gulou District, Cangshan District, and Changle District, extending southwards to Fuqing City. They mainly comprise LCZ 7 and LCZ 4. The thermal sink landscapes are predominantly located in the western counties of Yongtai, Minqing, and Minhou, extending from northern Fuqing City to eastern Luoyuan County, and are primarily composed of LCZ A. The corridors of thermal sink landscapes are more dispersed in comparison to those of thermal source landscapes. Obstruction points for heat source landscapes are predominantly concentrated along the corridor extending from the central urban area towards eastern Fuzhou and in eastern Fuqing City. In contrast, obstruction points for heat sink landscapes are dispersed across western, northern, and central Fuzhou, specifically in Yongtai County, Minqing County, Minhou County, and Luoyuan County. The barrier points for both heat source and heat sink landscapes primarily comprise LCZ 9, LCZ C, LCZ D, and LCZ G. Compared to heat sink landscapes, the distribution of barrier points in heat source landscapes is more concentrated. Within these corridors and barrier points, within built-up areas, high-SUHII LCZs can be transformed into low-SUHII LCZs through measures such as green roofs and vertical greening [45]. Previous studies indicate that 540,000 square meters of green roofs reduced the regional average LST by 0.91 °C. For every additional 1000 square meters of green roof area, the average LST decreases by 0.4 °C, with a cooling effect extending up to 100 m [46]. Greening 3.2% of building rooftops can reduce the regional average LST by 1.96 °C [47]. Vertical greening lowers the air temperature around foliage by 2–4 °C through plant transpiration [48]. For natural cover types, green space quality can be enhanced through strengthened conservation and afforestation efforts [49]. Adopting planning interventions that prioritize a network of vegetated public areas, safeguarded ecosystems [50], restored wet landscapes, and conserved waterfront zones can also effectively alleviate elevated temperatures [51]. The specific remedial measures for the associated issues are as follows:

- (1)

- For the identified heat source corridors, which are predominantly composed of LCZ 7 and LCZ 4, implementing green roofs and cool roofs is a highly targeted strategy to disrupt the propagation of heat along these pathways.

- (2)

- The barrier points within heat sink landscapes, largely comprising LCZ 9, LCZ C, and LCZ D, represent prime opportunities for ecological restoration. Converting these specific patches through afforestation or creating ecological culverts can effectively reconnect the fragmented cooling corridors.

- (3)

- LCZ1 and LCZ2, which are key heat sources, vertical greening and increasing urban tree canopy are prioritized measures to enhance evapotranspiration and shading.

- (4)

- The protection and expansion of the core heat sink areas, overwhelmingly dominated by LCZ A, must be enforced through ecological conservation redlines to preserve the city’s primary cooling capacity.

4.3. Challenges of the Current Inquiry and Directions for Further Exploration

First, this study focuses on analyzing the daytime surface urban heat island intensity (SUHII). While this approach effectively reveals the spatial patterns of daytime heat sources/sinks, it fails to capture the complete diurnal cycle dynamics of the urban heat island (UHI). Municipal engineering elements (such as structural cement and road surfacing) demonstrate significant heat storage capacity and, after ingesting and retaining solar energy during the day, they slowly release it at night, causing urban areas to cool much more slowly than suburban areas [52]. For instance, this study identifies water bodies (LCZ G) and dense vegetation (LCZ A) as potent daytime cooling sources. However, prior research indicates that under stable atmospheric conditions, water bodies may become relative heat sources at night due to their substantial thermal inertia, while vegetation’s cooling effect diminishes nocturnally. Therefore, Future research should integrate nighttime surface temperature data from sensors like MODIS to construct diurnal thermal source–sink networks. This will provide more comprehensive scientific evidence for developing all-day, precision-targeted heat mitigation strategies.

Secondly, in conducting a detailed analysis of thermal landscape networks, this study focused solely on the distribution of corridors and barrier points constituting the network, along with LCZ typology characteristics, without delving into corridor width. Future research should explore the optimal width of critical corridors based on their importance, thereby preventing further deterioration of thermal landscape impacts on the thermal environment. It should also analyse resource allocation structures that maximise the cooling effect of heat sink landscapes [51]. Additionally, the current study relies primarily on remote sensing data and modeling simulations. A fruitful direction for future research would be the introduction of expert and stakeholder focus groups. For instance, convening professionals from urban planning, landscape architecture, climatology, and local government departments to discuss our identified networks of heat source/sink landscapes, corridors, and barrier points could be highly valuable. This qualitative approach would serve to validate the rationality and prioritization of our model results from a practical standpoint, assess the technical feasibility and social acceptability of the proposed mitigation strategies and gather invaluable insights regarding policy implementation, cost–benefit considerations, and community engagement.

Finally, while achieving the aforementioned findings, this study acknowledges certain limitations in its temporal scale and research scope. Temporally, although the three strategic time points (2016, 2020, and 2023) effectively capture the medium-term evolutionary trajectory of the thermal environment pattern, monitoring over a longer time series would help verify the stability of these patterns. In terms of research scope, the current work focuses on the urban heat island phenomenon and has not yet extended this methodology to other typical urban ecological challenges. Building on this, we plan to expand the application of this method in subsequent research, applying it to the analysis of more urban ecological issues such as air pollution dispersion and urban ventilation corridor identification. By incorporating data from more time points and integrating nighttime land surface temperature monitoring, we aim to construct a more comprehensive, multi-factor integrated urban ecological environment assessment framework, thereby providing more holistic scientific evidence for urban planning and development decision-making.

5. Conclusions

In this era of rapid urbanisation, the urban heat island effect has become an environmental issue that cannot be ignored. It is necessary to construct a comprehensive thermal environment network to separately represent the spatiotemporal variations in both the intensification and mitigation of the heat island effect. This paper proposes a methodology integrating the concepts of LCZ and source–sink theory. Remote sensing imagery of Fuzhou City is first processed to derive LST inversion maps and LCZ classifications. Based on LST distribution patterns and spatiotemporal variations across LCZ types, these zones are categorised as heat-source landscapes and heat-sink landscapes. Morphological spatial pattern analysis and connectivity analysis are then employed to identify key source and sink locations within each landscape type. The core heat source landscape is primarily constituted by LCZ 4, LCZ 7, and LCZ D, which accounted for 19.71%, 13.66%, and 21.72% of the total core heat source area respectively between 2016 and 2023. Within the core heat sink landscape, LCZ A held the largest proportion, accounting for 86.28%, 91.36%, and 91.17% of the core heat sink area in 2016, 2017, and 2023 respectively. A total of 75 corridors were identified within heat source landscapes, spanning 563.85 km in total length. These primarily clustered around the central urban area and extended towards the southeast, with LCZ 7 and LCZ 4 constituting the predominant types, accounting for 21.96% and 29.25% respectively. Within heat sink landscapes, 70 corridors were identified, totaling 350.81 km in length, primarily distributed across the western and northeastern regions. The predominant LCZ type was LCZ A, accounting for 96.36%. The extensive forested resources of the Beifeng Mountains and Gushan in the north and west, comprising large, contiguous forest patches, constitute the ‘sources’ of the city’s cold islands. Consequently, the corridors connecting these areas prioritise traversing forest regions with the most favourable ecological baseline. Spatially, this manifests as corridors being almost entirely covered by forest vegetation. 40 barrier points were extracted within the heat source landscape, primarily comprising LCZ G and LCZ D, accounting for 22.50% and 17.50% respectively. Within the heat sink landscape, 84 barrier points were identified, mainly consisting of LCZ A, LCZ 9, LCZ C and LCZ D, representing 36.90%, 14.29%, 14.29% and 9.52% respectively. To mitigate Fuzhou’s urban heat island effect, key heat source areas within the heat source landscape shall be segmented using heat sink landscapes to reduce their heat storage capacity. Buildings exhibiting high SUHII values shall implement green roof construction to lower SUHII. Upgrade degraded habitats in urban-rural transition zones and advance naturalisation projects along waterfronts. Ecologically rehabilitate barrier points within the heat sink landscape network through measures such as constructing ecological culverts and expanding linear green belts. Implement ecological restoration for topographical discontinuities within forests and linear infrastructure, enhancing the configuration and condition of urban foliage, along with conserving ponds, streams, and designated saturation zones in focal regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010260/s1, Figure S1: The distance gradient map of connectivity indicators of heat source and sink landscapes in Fuzhou from 2016, 2020 and 2023: NL, NC, EC(IIC) and EC(PC) are number of links, number of components, equivalent connectivity corresponding to the integral index of connectivity, and equivalent connectivity corresponding to the probability of connectivity; Table S1: Classification of land surface temperature grades; Table S2: The descriptions of morphological spatial pattern analysis; Table S3: Confusion matrix of LCZ classification maps for Fuzhou, 2016; Table S4: Confusion matrix of LCZ classification maps for Fuzhou, 2020; Table S5: Confusion matrix of LCZ classification maps for Fuzhou, 2023.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.; methodology, S.Z.; software, S.Z.; validation, S.Z.; formal analysis, S.Z.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, S.Z.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.Z., Y.C. (Yanhong Chen), W.P.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, Y.C. (Yuanbin Cai). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Fujian Province Education Science Planning Routine Project for 2024 (FJJKBK24-018).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Klein, T.; Anderegg, W.R.L. A vast increase in heat exposure in the 21st century is driven by global warming and urban population growth. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 73, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Yu, Z.; Yang, G.; Liu, T.Y.; Liu, T.Y.; Hung, C.H.; Vejre, H. How to cool hot-humid (Asian) cities with urban trees? An optimal landscape size perspective. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 265, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Kolokotsa, D. On the impact of urban overheating and extreme climatic conditions on housing, energy, comfort and environmental quality of vulnerable population in Europe. Energy Build. 2015, 98, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Guo, X.; Jørgensen, G.; Vejre, H. How can urban green spaces be planned for climate adaptation in subtropical cities? Ecol. Indic. 2017, 82, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yu, Z.; Jørgensen, G.; Vejre, H. How can urban blue-green space be planned for climate adaption in high-latitude cities? A seasonal perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, A.A.; Sobhaninia, S.; Nikookar, N.; Levinson, R.; Sailor, D.J.; Amaripadath, D. Data-driven approach to estimate urban heat island impacts on building energy consumption. Energy 2025, 316, 134508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cristo, E.; Evangelisti, L.; Battista, G.; Guattari, C.; De Lieto Vollaro, R.; Asdrubali, F. Annual Comparison of the Atmospheric Urban Heat Island in Rome (Italy): An Assessment in Space and Time. Buildings 2023, 13, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Ji, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Cui, X.; Tong, H. Combined impact of climate change and urban heat island on building energy use in three megacities in China. Energy Build. 2025, 331, 115386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estoque, R.C.; Murayama, Y.; Myint, S.W. Effects of landscape composition and pattern on land surface temperature: An urban heat island study in the megacities of Southeast Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 577, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Miao, C.; Ye, X.; Min, M. Linking Heat Source–Sink Landscape Patterns with Analysis of Urban Heat Islands: Study on the Fast-Growing Zhengzhou City in Central China. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cao, Q.; Lang, K.; Wu, J. Linking potential heat source and sink to urban heat island: Heterogeneous effects of landscape pattern on land surface temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Fu, B.; Zhao, W. Source-sink landscape theory and its ecological significance. Front. Biol. China 2008, 3, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Ouyang, S.; Gou, M.; Tang, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Lei, P.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, C.; Xiang, W. Detecting the tipping point between heat source and sink landscapes to mitigate urban heat island effects. Urban Ecosyst. 2023, 26, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Cheng, X.; Hu, Y.; Corcoran, J. A landscape connectivity approach to mitigating the urban heat island effect. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Peng, C.; Huang, C.; Dian, Y.; Teng, M.; Zhou, Z. Seasonal Variations of the Relationship between Spectral Indexes and Land Surface Temperature Based on Local Climate Zones: A Study in Three Yangtze River Megacities. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Gao, C.; Pan, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z. Research on Optimal Cooling Landscape Combination and Configuration Based on Local Climate Zones—Fuzhou, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, L.; Mu, K.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J. Urban heat island effects of various urban morphologies under regional climate conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimolai, C.; Aguilar, E. Urban Heat Hotspots in Tarragona: LCZ-Based Remote Sensing Assessment During Heatwaves. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ren, C.; Lau, K.K.-L.; Ng, E. Investigating the influence of urban land use and landscape pattern on PM2.5 spatial variation using mobile monitoring and WUDAPT. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.K.C.; Shooshtarian, S.; Kenawy, I. Assessment of urban physical features on summer thermal perceptions using the local climate zone classification. Build. Environ. 2023, 236, 110265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Huang, H.; Hong, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, L. Modeling intra-urban differences in thermal environments and heat stress based on local climate zones in central Wuhan. Build. Environ. 2022, 225, 109625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhan, W.; Dong, P.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Miao, S.; Jiang, L.; Du, H.; Wang, C. Surface air temperature differences of intra- and inter-local climate zones across diverse timescales and climates. Build. Environ. 2022, 222, 109396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Voogt, J.; Ren, C.; Ng, E. Spatial-temporal variations of surface urban heat island: An application of local climate zone into large Chinese cities. Build. Environ. 2022, 222, 109378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, H. Analysis of Spatio-temporal patterns and related factors of thermal comfort in subtropical coastal cities based on local climate zones. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Jiang, S.; Zhan, W.; Bechtel, B.; Liu, Z.; Demuzere, M.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Xia, W.; et al. Mapping local climate zones for cities: A large review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 292, 113573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, C.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Lai, S.; Sha, J. Does land use change decline the regional ecosystem health maintenance? Case study in subtropical coastal region, Fuzhou, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danylo, O.; See, L.; Bechtel, B.; Schepaschenko, D.; Fritz, S. Contributing to WUDAPT: A Local Climate Zone Classification of Two Cities in Ukraine. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 1841–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonck, M.-L.; Okujeni, A.; van der Linden, S.; Demuzere, M.; De Wulf, R.; Van Coillie, F. Influence of neighbourhood information on ‘Local Climate Zone’ mapping in heterogeneous cities. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2017, 62, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Ren, C.; Xu, Y.; Lau, K.K.-L.; Wang, R. Investigating the relationship between local climate zone and land surface temperature using an improved WUDAPT methodology—A case study of Yangtze River Delta, China. Urban Clim. 2018, 24, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitraka, Z.; Frate, F.D.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.P. Exploiting Earth Observation data products for mapping Local Climate Zones. In Proceedings of the 2015 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE), Lausanne, Switzerland, 30 March–1 April 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, P.; Li, J.; Cao, L.; Pu, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Gong, H. Assessing spatiotemporal characteristics of urban heat islands from the perspective of an urban expansion and green infrastructure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhan, W.; Wang, J.; Voogt, J.; Wang, M. Multi-temporal trajectory of the urban heat island centroid in Beijing, China based on a Gaussian volume model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 149, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Su, J. Block-based variations in the impact of characteristics of urban functional zones on the urban heat island effect: A case study of Beijing. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soille, P.; Vogt, P. Morphological segmentation of binary patterns. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2009, 30, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, G. How to build a heat network to alleviate surface heat island effect? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Yu, L. Effects of urban agglomeration and expansion on landscape connectivity in the river valley region, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 34, e02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, S.; Pascual-Hortal, L. A new habitat availability index to integrate connectivity in landscape conservation planning: Comparison with existing indices and application to a case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Hortal, L.; Saura, S. Comparison and development of new graph-based landscape connectivity indices: Towards the priorization of habitat patches and corridors for conservation. Landsc. Ecol. 2006, 21, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shan, B.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, Q. Comprehensive effect of the three-dimensional spatial distribution pattern of buildings on the urban thermal environment. Urban Clim. 2022, 46, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Li, X. A cold island connectivity and network perspective to mitigate the urban heat island effect. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 94, 104525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Yin, H.; Nakagoshi, N.; Zong, Y. Urban green space network development for biodiversity conservation: Identification based on graph theory and gravity modeling. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 95, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, P.; Pan, W. Quantifying the Impact of Land use/Land Cover Changes on the Urban Heat Island: A Case Study of the Natural Wetlands Distribution Area of Fuzhou City, China. Wetlands 2016, 36, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, H. Reverse Thinking: The Logical System Research Method of Urban Thermal Safety Pattern Construction, Evaluation, and Optimization. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Z.; He, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, C. Spatiotemporal Regulation of Urban Thermal Environments by Source–Sink Landscapes: Implications for Urban Sustainability in Guangzhou, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertop, H.; Atılgan, A.; Jakubowski, T.; Kocięcka, J. The Benefits of Green Roofs and Possibilities for Their Application in Antalya, Turkey. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Dong, J.; Jones, L.; Liu, J.; Lin, T.; Zuo, J.; Ye, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, T. Modeling green roofs’ cooling effect in high-density urban areas based on law of diminishing marginal utility of the cooling efficiency: A case study of Xiamen Island, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, A.; Arefi, H.; Fathipoor, H. Simulation of green roofs and their potential mitigating effects on the urban heat island using an artificial neural network: A case study in Austin, Texas. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 1846–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Chen, J.; Zeng, L.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, X. Comparative Study on Different Forms of Vertical Greening of Building External Walls (Taking Guangzhou as an Example). Guangdong Archit. Civ. Eng. 2019, 26, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Piao, Y. The Cooling Effect and Its Stability in Urban Green Space in the Context of Global Warming: A Case Study of Changchun, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Yang, C. Analyzing Cooling Island Effect of Urban Parks in Zhengzhou City: A Study on Spatial Maximum and Spatial Accumulation Perspectives. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tong, C. Spatiotemporal evolution of urban green space and its impact on the urban thermal environment based on remote sensing data: A case study of Fuzhou City, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Liu, G.; Chen, J.; Xu, Z. Coupling between local climate zones and diurnal urban heat island effect. J. Nanjing Univ. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2022, 14, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.