Abstract

The insurance sector plays a crucial role in maintaining economic stability and the financial security of households; however, the level of demand for insurance products remains lower than would be expected based on consumers’ actual risk exposure. Previous research indicates that insurance purchasing decisions are shaped not only by economic factors but also by psychological and behavioral mechanisms. The aim of this article is to identify and systematize the most important determinants influencing consumer demand for insurance products, with particular emphasis on cognitive barriers and attitudes that reduce purchase propensity. The study employs an extensive literature review and structural equation modeling (SEM-PLS), enabling the simultaneous analysis of the relationships between attitudes, knowledge, beliefs, experiences, risk perception, and actual insurance ownership. From a sustainable development perspective, this mechanism fosters a “culture of responsibility”—insurance becomes a permanent and predictable element. The results demonstrate that insurance decisions are the result of a complex interaction of multiple factors (cognitive, normative, emotional, and relational) rather than simply a response to risk levels. The most important determinants of insurance policy ownership are as follows: (1) internal standards of responsibility, (2) product competence, (3) quality of experience, (4) lack of cognitive barriers, and (5) a sense of trust in the institution and advisor. From a sustainability perspective, these results suggest that the insurance market is in a “partially balanced” phase: strong elements promoting sustainable resilience are visible (standards of responsibility, the growing importance of knowledge, the role of positive experiences), but at the same time, clear barriers remain (lack of trust, underestimation of risk, postponement of decisions), which limit the full potential of insurance as a tool for socioeconomic stabilization.

1. Introduction

The insurance industry is a crucial sector of the economy, significantly influencing the economic development of countries [1] and playing a vital role in society [2]. Insurance provides a fundamental safeguard against economic uncertainty [3]. The insurance industry contributes to the financial stability of countries by effectively managing risks for individuals and businesses [4]. Furthermore, it generates savings and capital for development projects and the growth of the capital market, thus supporting economic progress [5,6]. The literature increasingly emphasizes that a stable insurance system serves not only a financial and protective function but also an institutional one, supporting the achievement of sustainable development goals by strengthening the resilience of economies, reducing household vulnerability to shocks, and reducing the risk of economic exclusion [6,7,8].

The global insurance market is constantly evolving, driven by changes in the economic, social, legal, and natural environments [9]. Technological progress contributes to the creation of a wide range of innovative products and services [10]. Insurance products are evolving to increasingly meet customer needs and bridge the gap between the products offered by the insurance industry and consumer expectations [11]. In recent years, the role of insurers in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals has been increasingly emphasized [12]. Insurance—as a mechanism stabilizing the financial situation of individuals and enterprises—is an important pillar of a resilient and sustainable economy. Achieving sustainable development requires the stability and financial security of enterprises, ensuring continuous operation, which is why insurance is an important factor in ensuring economic sustainability [13]. Global climate, political, and social changes have also highlighted the need to introduce sustainable practices in the insurance industry [14,15]. When choosing an insurance policy, customers are also increasingly paying attention to the sustainability of insurance companies and the products they offer [16]. In this context, insurance becomes not only a financial instrument, but also a component of responsible consumer behavior supporting the resilience and sustainability of socioeconomic systems.

The primary role of insurance is to satisfy the need for security, which is one of the basic human needs. The need for security is associated with reducing uncertainty and risks related to human life and activity [17,18]. At the same time, numerous studies have shown that consumers often make mistakes in insurance markets, particularly when deciding to purchase insurance for events with a low probability of occurrence but high consequences. Consumers’ difficulties in making insurance decisions stem from challenges in obtaining and processing information to assess threats, their likelihood of occurrence, and potential consequences [19,20]. This leads to a departure from entirely rational behavior [21] and the use of ad hoc rules (“heuristics”) for assessing uncertainty and risk [22]. As a result, consumers overestimate or underestimate the probability of random events and purchase insurance policies in excess or in short supply compared to their actual risk exposure. This, on a macro scale, affects the level of household security and, thus, their economic resilience—the foundation of sustainable development.

Several factors influence a consumer’s decision to purchase an insurance policy. From the perspective of traditional economics, consumer decisions are driven by the desire to maximize the utility of total wealth [23,24]. The willingness to purchase an insurance policy depends mainly on the policy buyer’s knowledge [10] and their perception of the risk they face [25]. However, financial knowledge does not always translate into insurance knowledge; only specialized education can enhance insurance knowledge [26]. This highlights the need for risk management education, enabling consumers to rationally assess the probability of adverse events and determine their optimal insurance needs. From a sustainable development perspective, this means that insurance education serves a social function—it increases the economic resilience of households and reduces their vulnerability to shocks.

Besides the economic factors influencing the demand for insurance, such as the price of insurance, the consumer’s income and wealth, the supply of insurance, and the family’s financial security, non-economic factors also play a significant role, with psychological factors being particularly important. These factors are related to how a potential policy buyer perceives risk, losses, profits, a sense of security, and fear of harm [27]. The policyholder’s past experiences [28,29] and information about insurance obtained from family, friends, insurance intermediaries, or advertisements are also meaningful. This indicates the multitude and complexity of determinants influencing consumer insurance decisions, which in practice increases the difficulty of making the “right” decision. Poor insurance decisions undermine the financial security of individuals and, in a broader perspective, social stability and resilience, which are pillars of sustainable development. Customers who purchase sustainable insurance make conscious decisions, paying attention to economic, social, and environmental aspects.

The literature indicates that consumer decision-making regarding insurance is likely governed as much by psychology as by economics [30]. Because dealing with risk and insurance products involves complex decision-making processes, understanding behavioral factors is crucial for fully explaining customer behavior [24]. Therefore, behavioral economics provides a deeper understanding of consumer decisions in the insurance market, enabling the identification of the behavioral factors that influence these decisions [31]. At the same time, it allows the identification of “decision-making nodes” with a negative impact on demand—such as heuristics, risk perception errors, or insufficient knowledge—which can result in inadequate insurance coverage and weaken the long-term resilience of households.

Against this backdrop, the research problem of this article emerges: identifying and organizing the determinants that shape consumer demand for insurance products, with a particular emphasis on key factors that may have a potentially negative impact on insurance purchases. A review of the literature suggests that the sources of such barriers lie both in the informational sphere (cognitive difficulties, information asymmetry) and the psychological sphere (heuristics, risk perception errors, negative experiences), as well as in inadequate insurance knowledge. Importantly, these factors not only determine demand but also influence broader social processes—including the degree of economic security of the population and, therefore, the creation of conditions for sustainable development. This issue has not been sufficiently explored and addressed in the literature. Our study fills this gap by presenting results and conclusions regarding the relationships between factors shaping consumer demand for insurance products within the framework of sustainable development in Poland.

Therefore, the main research objective of this article is to identify and structure the key economic and behavioral determinants that shape consumer demand for insurance products. The main aim is developed through specific objectives, which include the following: a description of the consumer decision-making process in the insurance market, taking into account cognitive limitations, risk assessment errors, and the role of insurance knowledge; and the identification of key behavioral and psychological factors that, according to the literature, lead to underestimated or suboptimal demand for insurance products. The research problem and objectives defined in this way align with the broader trend of research on the behavioral economics of the insurance market, as well as the role of education, trust, and financial resilience of households in sustainable development processes.

2. Materials and Methods

The empirical basis for the analyses presented in this article is data from a nationwide, representative public opinion survey conducted on a sample of N = 1000 adult Polish residents. The sample selection was based on representativeness criteria with respect to key demographic variables, such as gender, age, education, region of residence, and city size. The survey was conducted in April 2025 using a standardized survey questionnaire. The collected data enabled a precise analysis of attitudes, beliefs, experiences, and consumer behaviors related to the insurance market.

The sustainability implications discussed in this study should be understood as indirect and conditional. The empirical analysis focuses on identifying behavioral and attitudinal determinants of insurance usage, which constitute micro-level prerequisites for sustainable development in the insurance market, rather than direct measures of sustainability outcomes.

2.1. Questionnaire Structure and Measurement Scales

The survey instrument was constructed to capture multiple dimensions of consumer interaction with insurance services, including attitudes, experience, usage intensity, perceived knowledge, and organizational competencies. Different question formats were intentionally applied to ensure adequate measurement of conceptually distinct constructs and to reflect successive stages of consumer engagement in the insurance market.

The structure of the questionnaire reflected the determinants shaping the extent of insurance usage. The questions varied depending on the specific dimension being measured, as the study addressed issues related to opinions, attitudes, knowledge, and the scope of insurance utilization. Accordingly, the questionnaire included both individual questions and multi-item scales, each selected to be appropriate for measuring a given construct or phenomenon. Most perceptual constructs were measured using Likert-type scales, while factual and behavioral aspects were assessed using categorical or frequency-based questions. This approach ensured consistency between the nature of the measured variables and the applied measurement instruments.

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

The empirical study was conducted on a nationwide, representative sample of adult residents of Poland aged 18 years and above. The sample was constructed to reflect the structure of the general population with respect to key sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age distribution, level of education, size of place of residence, and region (voivodeship). Such a sampling design ensures that the obtained results may be cautiously generalized to the adult population of Poland. The representativeness of the sample strengthens the external validity of the study and supports the robustness of the conclusions drawn from the structural equation modeling analysis.

The study sample consisted of 51% women and 49% men. In terms of age structure, 8% of respondents were aged 18–24 years, 14% were aged 25–34 years, 20% were aged 35–44 years, 25% were aged 45–59 years, and 33% were aged 60 years and above. Regarding educational attainment, 13% of respondents had primary or lower secondary education, 23% had basic vocational education, 37% had secondary education, and 28% held a higher education degree. The regional distribution of the sample reflected all Polish voivodeships, including Lower Silesian (8%), Kuyavian–Pomeranian (6%), Lublin (6%), Lubusz (2%), Łódź (7%), Lesser Poland (10%), Masovian (13%), Opole (2%), Subcarpathian (6%), Podlaskie (3%), Pomeranian (6%), Silesian (13%), Świętokrzyskie (3%), Warmian–Masurian (3%), Greater Poland (10%), and West Pomeranian (4%). With respect to the size of place of residence, 41% of respondents lived in rural areas, 6% in towns with up to 10,000 inhabitants, 7% in towns with 10,001–20,000 inhabitants, 9% in towns with 20,001–50,000 inhabitants, 8% in towns with 50,001–100,000 inhabitants, 10% in cities with 100,001–200,000 inhabitants, 7% in cities with 200,001–500,000 inhabitants, and 12% in cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants.

Data collection was carried out using a structured questionnaire distributed by a professional research agency in accordance with ESOMAR standards. Only fully completed questionnaires were included in the final dataset; responses with missing or incomplete data were excluded from further analysis.

The system of latent and measurable variables is presented in Table 1. They were subsequently used to estimate a structural equation model (SEM-PLS), which forms the basis of the presented results. Structural equation modeling (SEM) is one of the most important analytical methods used in social sciences, marketing, psychology, and behavioral economics. SEM enables the simultaneous analysis of relationships between multiple latent variables and observables (indicators), allowing for the modeling of complex relationships between theoretical constructs [32,33]. Traditionally, two approaches are distinguished: CB-SEM (covariance-based SEM) and PLS-SEM (variance-based SEM, partial least squares). CB-SEM focuses on providing the best possible representation of the covariance matrix and is particularly suitable when the goal is to test a theory, especially in situations where the model is well established in the literature [34]. PLS-SEM, on the other hand, is predictive in nature—its primary goal is not to reproduce the correlation matrix but to maximize the explained variance of endogenous variables (predictive relevance). Therefore, PLS-SEM is ideal for exploratory research, multi-construct models, data with partial normality, and in situations where the sample size is not very large [33,35]. According to Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt [36], the evaluation of PLS-SEM models should encompass two primary components: a measurement model and a structural model.

Table 1.

Specification of model variables.

The choice of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was motivated by the aims and analytical focus of the study. Although the sample size would allow for the application of covariance-based SEM, the primary objective was not theory confirmation but the exploration and prediction of relationships among psychological and perceptual constructs influencing insurance behavior. PLS-SEM is particularly appropriate in this context, as it emphasizes variance explanation, allows for the simultaneous estimation of complex models with multiple mediating relationships, and is robust to deviations from multivariate normality. Furthermore, the study focuses on identifying empirically supported directional effects rather than reproducing a predefined covariance structure. For these reasons, PLS-SEM was considered the most suitable methodological approach for addressing the research objectives of the study.

2.3. Measurement Model

A measurement model describes how latent variables are represented by a set of observable variables. In PLS-SEM, reflective constructs are most commonly used, in which indicators reflect a common latent factor. Assessment of the measurement model includes Indicator reliability, assessed through factor loadings (≥0.70 preferred), and internal construct reliability, assessed through Cronbach’s α, Composite Reliability (CR), and rho_A. Values > 0.70 are considered satisfactory [37]. Convergent validity—assessed through Average Variance Extracted (AVE), where AVE ≥ 0.50 indicates that the constructs explain more than half of the variance in their indicators [38]. Discriminant validity—assessed by using the Fornell–Larcker method and the HTMT (Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio), where values < 0.85 or <0.90 indicate adequate distinctiveness of the constructs [36].

2.4. Structural Model

A structural model defines the relationships between latent variables. Its evaluation includes the R2 (coefficient of determination), which describes the percentage of variance that the model explains. In the social sciences, values are categorized as follows: 0.19—weak, 0.33—moderate, and 0.67—strong [35]. f2 (effect size) describes the strength of influence of a single predictor: 0.02—small, 0.15—medium, and 0.35—large. Q2 (Stone-Geisser) describes the predictive ability of the model (values > 0 suggest predictive accuracy). Global fit refers to the SRMR and NFI. Although PLS-SEM does not primarily emphasize global fit, SRMR < 0.08 is considered good. PLS-SEM is particularly valuable in analyzing consumer behavior, where psychological variables (such as attitudes, beliefs, and emotions) jointly influence decisions. In insurance research, this method enables the simultaneous capture of rational, emotional, normative, and experiential effects.

The overall model fit was assessed using multiple fit indices recommended for PLS-SEM analysis (Table 2). The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) reached a value of 0.074, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.08, indicating an acceptable level of model fit. The discrepancy measures d_ULS (1.871), d_G1 (0.562), and d_G2 (0.465) further suggest that the differences between the empirical and model-implied correlation matrices remain within an acceptable range, supporting the adequacy of the proposed model structure. Although the normed fit index (NFI) equals 0.650, which indicates moderate rather than strong model fit, such values are not uncommon in complex PLS-SEM models focused on prediction rather than covariance reproduction. Taken together, the fit statistics suggest that the model demonstrates an acceptable overall fit and is suitable for further interpretation of the structural relationships.

Table 2.

Model Fit Statistics.

Some constructs in the measurement model exhibit reliability indicators slightly below conventional thresholds. These constructs were retained based on their theoretical importance and their contribution to explaining the structural relationships of interest. Importantly, only statistically significant paths were included in the final model, and lower reliability implies more conservative estimates rather than inflated effects. As a result, the observed significant relationships involving these constructs can be regarded as robust, although their interpretation should take into account the potential presence of measurement error.

3. Results

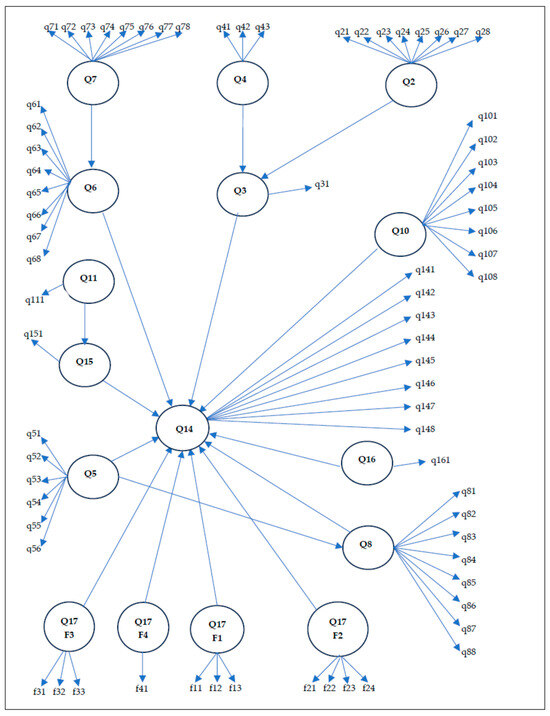

Structural equation modeling analysis allows for the reconstruction of the complex system of psychological, social, and cognitive relationships that shape consumer decisions regarding insurance purchases. The results clearly indicate that a single, dominant factor does not drive insurance behavior; rather, a multidimensional combination of attitudes, experiences, concerns, knowledge, and beliefs about the insurance market is at play. The individual elements of the model create interconnected cognitive-emotional chains that collectively determine consumers’ willingness to enter into insurance contracts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of conditions for using insurance.

3.1. Measurement Model Assessment

Reliability—most reliable constructs: Q10 (knowledge about offers): CR = 0.93, α = 0.91; Q6 (concerns): CR = 0.90; Q2 (whether get insurance): CR = 0.90; Q8 (offer matching): CR = 0.90. Exploratory constructs with lower reliability: Q17_F1, Q17_F2, Q17_F3 (α < 0.60); Q7 (events)—AVE < 0.50; AVE of most constructs >0.50, except for Q14 and Q7. HTMT is below 0.90 for most pairs, one case close to 0.94—acceptable; Q14—insurance held: R2 = 0.41; Q3—normative attitude: R2 = 0.33; Q6—R2 = 0.18; Q15—R2 = 0.19; Q8—R2 = 0.03; SRMR = 0.057 (insurance customization)—very good; NFI = 0.72—acceptable in PLS.

3.2. Model Path Graph

The normative attitude exerts the most substantial direct influence on actual insurance ownership, specifically the statement “I must/want to insure” (β = 0.29) (Table 2). This means that the stronger the belief that “insurance is necessary,” “it is worth insuring,” and that having a policy is an element of responsible and rational behavior, the greater the likelihood of actual purchase. This attitude serves a regulatory function and is a central construct of the entire model, acting both as a strong predictor of behavior and as a mediator of the influence of other variables, particularly the perceived value of insurance.

From a sustainable development perspective, this is a clearly pro-sustainability path: the internal norm “it’s worth insuring yourself” promotes household resilience to shocks, reduces their vulnerability to crises, and reduces the risk of a sudden decline in well-being following unexpected events. This attitude reinforces the micro-foundations of socioeconomic system stability, which are one of the pillars of sustainable development.

The second most influential factor is the level of knowledge and the ability to evaluate insurance offers, which has an impact on policy ownership, with a beta coefficient of 0.20 (Table 3). Consumers who can consciously compare products, understand the differences between coverage options, and know what risks are covered by a policy are significantly more likely to purchase insurance. This knowledge reduces uncertainty, strengthens a sense of empowerment, and increases the ability to assess the actual value of insurance.

Table 3.

Direct effects between constructs (β).

Such insurance competencies are one of the key conditions for “financially sustainable” households: they enable better risk management, limit losses in the event of a claim, and make decisions based on understanding rather than fear or stereotypes. This path is therefore also consistent with the logic of sustainable development, as it supports inclusiveness (by reducing the knowledge barrier), stability (by reducing vulnerability to shocks), and financial responsibility.

Barrier beliefs, or negative attitudes toward insurance, also play a significant role, including beliefs that “nothing will happen to me,” that “insurance isn’t worth it,” that “insurance companies won’t pay out anyway,” or that it is “too expensive.” Their direct impact on insurance ownership is β = 0.14, while their indirect impact—through a reduced sense of fit—is β = 0.014. These beliefs act as an interpretive filter: individuals with substantial barriers are less receptive to objectively favorable offers, more likely to reject them as unreliable or unnecessary, and are significantly less likely to purchase.

From a sustainable development perspective, this is a clearly unsustainable path: barrier beliefs perpetuate the lack of insurance coverage, increase vulnerability to adverse events, and reinforce “systemic fragility”—both at the individual and population levels. They also create a form of psychological exclusion from the insurance market, which contradicts the idea of an inclusive, sustainable financial system. A significant factor in reducing insurance coverage is postponing decisions to the future, with an effect of β = −0.19. Consumers who express the belief that they will “insure themselves someday” when they are older, wealthier, or their life situation stabilizes are among the group with the lowest levels of insurance activity. This mechanism suggests a psychological strategy of rationalizing avoidance—creating boundary conditions that rarely materialize spontaneously.

This path also operates contrary to the logic of sustainable development: insurance procrastination maintains a state of low risk resilience, especially in lower-income groups. It promotes the accumulation of inequalities in access to financial security. Instead of strengthening long-term stability, the “I’ll get insurance later” mechanism shifts risk into the future, increasing the scale of potential social losses.

The model also identifies three moderately influential factors: fear of random events (β = 0.07), a sense of fit between offers (β = 0.07), and positive experiences with insurance (β = 0.07). While fears are motivating, their impact is limited; a sense of fit serves a perceptual function and only supports decisions when the consumer believes the offer is adequate. Experiences, on the other hand, build long-term trust—fair claims settlement, transparent policies, and good service increase the likelihood of repeat purchases.

From a sustainability perspective, two of these elements—a sense of fit and positive experiences—can be considered the building blocks of a sustainable insurance market: they strengthen trust, a sense of agency, and the predictability of the relationship between the customer and the institution. However, fear itself, if not grounded in knowledge and trust, is ambivalent: it can encourage purchases, but also lead to avoidance or impulsive, irrational choices, which do not promote financial stability or well-being.

Complementing this are higher-order relationships that shape the emotional and cognitive foundation for decisions:

- Perceived insurance value → normative attitude, β = 0.48, meaning that the belief in the product’s reasonableness is a strong predictor of the emergence of the “it’s worth insuring” norm;

- Experiences of random events → fear of events, β = 0.42, confirming that real risk experience creates awareness of threats;

- The role of the advisor and the need for knowledge → positive experiences, β = 0.44, indicating the crucial importance of education and interpersonal relationships in shaping market trust.

From a sustainability perspective, the first and third paths are particularly constructive. The strong relationship between perceived value and the norm “insurance makes sense” (β = 0.48) promotes decision-making that strengthens the long-term resilience of households and, consequently, the stability of the system. In turn, the role of advisors and the need for knowledge (β = 0.44 → positive experiences) demonstrate that well-designed human-institution interaction can be a tool for building trust and inclusiveness, key to a sustainable financial market. The second path—from experiences of random events to fear (β = 0.42)—is more reactive, as it strengthens risk awareness only “after the event,” thereby supporting sustainable development indirectly and belatedly, rather than fostering prevention.

Indirect Effects: Analysis of indirect effects reveals the mechanisms that hold the entire decision-making system together. The most substantial indirect effect is found in the path: perceived value of insurance → normative attitude → insurance ownership, where the total effect is β = 0.14 (Table 3). This means that even high product value does not translate into purchase without activating normative beliefs about the value of insurance. This is an example of a pro-sustainability path: a consumer who understands the value of the product and recognizes insurance as part of responsible living internally strengthens their financial resilience and stability in a manner consistent with the concept of sustainable development.

The second critical chain is: experiences of random events → concerns → ownership, with an effect of β = 0.03 (Table 4). The experience of risk increases concerns, and these, albeit moderately, significantly encourage purchase.

Table 4.

Indirect effects between constructs (β).

This mechanism is indirectly and reactively linked to sustainable development: the insurance decision appears as a response to an adverse event, rather than as an element of long-term planning. From a public policy perspective, this suggests the need to shift the emphasis from “learning after the event” to prevention and education in anticipation of random events.

The next mechanism is: the advisor’s role and need for knowledge → positive experiences → ownership, also β = 0.03 (Table 3), confirming that education, transparency, and the quality of interaction with the advisor strengthen the genuine willingness to purchase. This path is critical from the perspective of an inclusive, sustainable market: a good advisor, clear communication, and positive experiences reduce behavioral barriers, increase access to insurance coverage for broader groups, and enhance the overall level of trust in the institution.

The final indirect effect is: barrier beliefs → sense of fit → ownership, with a value of β = 0.014.

Negative beliefs distort market perception—consumers begin to perceive even favorable offers as “inappropriate,” which reduces their willingness to purchase. From a sustainable development perspective, this mechanism is particularly unfavorable: it perpetuates insurance exclusion, creates “psychological barriers to entry,” and weakens the insurance market’s protective function for the most vulnerable household groups.

Together, all paths create a multi-channel decision-making model in which key factors play: normative attitude (β = 0.29), knowledge and ability to evaluate offers (β = 0.20), barrier beliefs (β = 0.14), decision postponement (β = −0.19), and the indirect effect of insurance value through normative attitude (β = 0.14).

Concerns, experiences, and perceived fit (β = 0.07) act as amplifiers and regulators, but they do not, in and of themselves, determine behavior. Consumers’ insurance purchasing decisions appear to be the result of the parallel influence of knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and experiences, rather than a simple response to a single market stimulus. From a sustainable development perspective, it can be said that some of these paths (normative attitude, knowledge, positive experiences, advisory role, product value perception) strengthen the resilience and stability of the system, while others (barrier beliefs, postponed decisions, distorted perception of fit) create “weakness points” where the idea of a sustainable, inclusive insurance market is not fully realized.

3.3. Direct Effects—Interpretation

The obtained PLS-SEM model enabled the identification of several direct effects between constructs (Table 3). The interpretation of the effects is as follows:

1.1. The “I have to/want to insure” attitude → insurance ownership. The attitude based on the internal belief that “insurance is necessary/worth it and should be done” is the strongest direct predictor of actual insurance ownership. This means that consumers do not buy policies “on impulse,” but rather when they consider insurance to be a norm, an obligation, or an element of responsible living. Psychologically, this is a motivational mechanism: a normative attitude becomes an “internal command to act.” From a sustainable development perspective, such an internal norm enhances the financial resilience of households and promotes more stable and predictable functioning in the face of unexpected events. Insurance becomes not only an individual choice, but also an integral part of a “sustainable” lifestyle, mitigating the scale of socioeconomic shocks following a loss.

1.2. Knowledge of offers and the ability to choose → insurance ownership. Another key factor is knowledge and competence in selecting insurance—the ability to distinguish between offers, understand how a policy works, and identify its key parameters. The relationship is direct: the greater the knowledge, the greater the self-confidence, and therefore the greater the willingness to make a purchase. This result confirms the concept of financial “self-efficacy”: knowledge reduces the fear of making a mistake and increases the desire to act. Such insurance competence also serves as “sustainable capital”—enabling more informed risk management, reducing the likelihood of drastic declines in well-being, and contributing to a more even distribution of the effects of random events over time and across social groups.

1.3. Barrier beliefs (“Nothing will happen to me,” “Insurance isn’t worth it”) → insurance coverage. Beliefs act as cognitive filters. If a consumer believes that nothing will happen to them, insurance is unnecessary, insurers are deceiving, or “it’s too expensive,” their willingness to purchase significantly decreases. The model suggests that barrier beliefs actually hinder purchasing decisions, influencing them systematically rather than incidentally. From a sustainable development perspective, these mechanisms weaken the system’s resilience, as they perpetuate low insurance penetration, increase vulnerability to shocks, and effectively lead to the “insurance exclusion” of some households, which contradicts the idea of an inclusive, balanced financial market.

1.4. Delaying decisions (“I’ll get insurance when…”) → insurance coverage. An interesting and very important predictor is the group of responses in which consumers declare: “I’ll get insurance when I’m older,” “when I earn more,” and “when I have children.” All of these declarations create constructs of conditional thinking—shifting responsibility into the future. The model clearly shows that people who postpone decisions statistically have significantly less insurance in the present. In other words, this isn’t an actual plan, but a psychological “justification for inaction.” In terms of sustainable development, this means maintaining a state of “fragility”—the lack of ongoing coverage promotes rapid declines in financial stability after a loss, shifting the burden of risk from the insurance system to households and the public sector.

1.5. Attractive offers, clear rules, and a trusted advisor → having insurance. This factor is positive: people who believe that clear rules, a reasonable price, and a trusted advisor are key statistically are more likely to have insurance. Interpretation: These consumers are more proactive and open, and the declaration “I need clear rules” doesn’t indicate resistance, but rather the demands of an informed customer. Clarity of rules, transparency, and the role of the advisor are also prerequisites for building institutional trust, without which it is difficult to speak of a sustainable insurance market. Such relationships foster more equitable access to protection and increase the chances that products will be used long-term, rather than incidentally.

1.6. Fear of random events → insurance ownership. Fears influence decisions, but not as strongly as often assumed in insurance marketing. The effect is positive, but moderate: fear itself does not drive insurance purchases. This means that intensive campaigns to scare consumers are less effective than commonly assumed. From a sustainable development perspective, this is a significant signal: policies based solely on “fear management” do not establish lasting, stable patterns of protection and, therefore, do not foster sustainable systemic resilience. It is essential to combine risk awareness with knowledge, trust, and a sense of purpose when making purchasing decisions.

1.7. Tailoring offers to needs → insurance ownership. The consumer’s impression that the offers available on the market are well-suited to their life and situation has a small but significant positive effect. This is a perceptual factor: consumers need to feel that the market is on their side. A well-perceived tailoring of offers is also an element of the “sustainable design” of financial products: it increases the likelihood that insurance coverage will be used rationally, in line with real needs, rather than through haphazard or forced purchases.

1.8. Positive experiences with previous insurance → insurance ownership. Positive experiences, such as efficient claims settlement, good product explanation, and advisory support, increase the number of policies held. This is a classic “learning through experience” mechanism. From a sustainable development perspective, positive experiences build long-term trust and foster lasting relationships between customers and institutions. This is one of the key conditions for the stability of the insurance system: consumers who feel they are treated fairly are willing to maintain their coverage and expand it as their needs change.

3.4. Indirect Effects

The most significant value of the PLS-SEM model lies in its ability to analyze indirect effects, thereby revealing hidden psychological mechanisms (Table 4). All relevant relationships are presented below.

2.1. Perceived value of insurance → normative attitude → insurance ownership. This is the strongest indirect chain in the entire model. The mechanism works as follows: The consumer believes that insurance has real value (economic or life). This increases their normative belief that “insurance is necessary/worth it.” A normative attitude leads to a higher number of insurance policies. This is the classic role of attitude as a mediator between cognition and behavior, consistent with Ajzen’s theory [39] and modern cognitive models.

From a sustainable development perspective, this is a particularly desirable path: decisions are not the result of momentary fear, but of a lasting belief in the product’s value, which promotes the development of stable, long-term protection at both the individual and system levels.

2.2. Experience of life events → fears → insurance coverage. This is a chain of moderate strength but strong psychological coherence. If someone has experienced serious events (such as theft, fire, illness, or accident—in themselves or their loved ones), their concerns about the future and safety increase. And these fears lead to a slight increase in insurance coverage. Experiential learning is effective, but it is not the primary driver of purchasing decisions. From a sustainable development perspective, this is a more reactive than preventative mechanism: the system learns only after the event. This means that for the insurance market to fulfill a fully sustainable stabilizing function, it cannot rely solely on the experience of traumatic events to “push” consumers into insurance.

2.3. Need for knowledge and the role of an advisor → positive experiences → insurance coverage. This mechanism is fascinating and practically significant. Consumers believe that an advisor is necessary and that knowledge is essential. This increases the chances of positive experiences when dealing with insurance. Positive experiences lead to more insurance policies purchased. The advisor’s role is crucial; every contact with an advisor can change market perceptions to a more positive one. In the logic of sustainable development, this path highlights the importance of the market’s “human infrastructure”—competent advisors and good communication foster the inclusion of additional customer groups in the insurance system, reduce inequalities in access to knowledge, and strengthen long-term relationships based on trust.

2.4. Barrier beliefs → tailored offers → insurance ownership. This indirect effect is weak but cognitively significant. Barrier beliefs influence how consumers perceive market offers, which ultimately influences their purchasing decisions. This means that consumers don’t see the market as it is. They see it as their own beliefs allow them to do so. For sustainable development, this is a “weak point” in the system: even well-designed, potentially inclusive products can be ignored by people with strong barriers, perpetuating segments of the population that remain permanently outside the insurance system.

3.5. Integration of Direct and Indirect Effects

The greatest direct impact includes normative attitudes (“I must/want to insure”), knowledge and competencies, an attractive and understandable offer/agent role, and barrier beliefs. The following paths determine the greatest indirect impact:

- Perceived value → attitude → ownership;

- Experience → concerns → ownership;

- Advisor → experiences → ownership.

Regardless of the path, the most influential factor is whether insurance is perceived as a value and norm. Knowledge also plays a huge role. Fears and worries are secondary. Barrier beliefs are blocking. From a sustainable development perspective, it can be said that paths based on value, knowledge, trust, and positive experiences build a “sustainable architecture” of the insurance market—strengthening resilience, inclusiveness, and stability. In turn, paths based on cognitive barriers, decision-making delays, and distorted perceptions of fit create risk areas where the potential of insurance as a tool for sustainable development is not fully utilized.

Consumers buy insurance not because they are afraid, but because they consider it sensible, understandable, valuable, and consistent with their own standards of responsibility. It is this set of factors—reinforced by education, trust, and positive experiences—that brings the insurance market closest to operating in the spirit of sustainable development.

4. Discussion

The obtained results contribute to the growing trend of research on the determinants of insurance demand, while also clearly clarifying and deepening them in several key areas. Above all, the presented model confirms the central role of internal normative attitudes—the belief that “insurance is necessary/worth it”—as the strongest predictor of actual policy ownership. This is directly consistent with Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, which posits that attitudes and norms are the primary drivers of intentional behavior, including financial decisions [39]. In their research on travel insurance, Huang, Chang, and Sia [40] demonstrated that attitudes toward insurance and subjective norms are significant determinants of purchase intentions, with perceived usefulness and trust in the product strongly reinforcing pro-insurance attitudes. In the insurance market, similar conclusions were presented in Achmadi’s study [41], which demonstrated that attitudes and subjective norms significantly influence the intention to purchase health insurance. The presented model takes this idea a step further by showing the real impact of normative attitudes, understood in this way, not only on intention but also on actual insurance possession.

The second pillar of insurance demand turned out to be knowledge and competence in selecting insurance, which are among the strongest direct predictors of the number of policies held. The results indicate that consumers who understand the structure of insurance products, can compare offers, and evaluate their parameters, are significantly more likely to purchase coverage. The effects of financial and insurance education have been repeatedly emphasized in the literature: Wang et al. [42] demonstrated that the level of financial literacy positively correlates with the demand for life insurance, which aligns well with broader research on the role of financial literacy in insurance decisions. Lin et al. [43] demonstrated that individuals with higher financial literacy are more likely to use advisors and are less likely to avoid complex products, resulting in a higher likelihood of owning life insurance. Research on insurance behavior in developing countries continues in a similar vein, emphasizing that insufficient knowledge leads to misperceptions about the risks, costs, and benefits of insurance. The presented results align with this trend, but also emphasize an additional aspect: not only is a general level of financial literacy critical, but above all, specific, product-specific knowledge about how to choose a policy that suits individual needs is crucial. This is more about “practical competence” than abstract financial education.

Similar conclusions are drawn from the work of Ćurak et al. [17], who analyzed the demand for property insurance, showing that a higher level of financial literacy increases the likelihood of purchasing policies. The presented results further emphasize this point, suggesting that it is not general financial knowledge alone, but rather detailed, practical knowledge of insurance products and the ability to evaluate them, that directly influences consumer behavior.

In the context of the role of education, it is worth citing studies that present a more ambivalent picture of its effectiveness. Dercon et al. [44] analyzed the demand for insurance under conditions of limited trust and found that financial education alone does not always increase the propensity to purchase insurance. Instead, belief in the enforceability of benefits and the effectiveness of claims payments is far more critical. The results partially confirm this conclusion: risk awareness or general education alone are insufficient if the consumer remains trapped in negative beliefs (“insurers won’t pay anyway,” “it’s not worth it”) or lacks prior experiences that build trust. On the other hand, the significant role of positive experiences with insurance and a sense of fit with the offer suggests that knowledge must be coupled with the quality of relationships and experiences, rather than being limited solely to the theoretical layer.

The literature on the demand for life insurance and other protection products has long emphasized the importance of economic factors, including income, wealth, and household demographic structure. Beck and Webb [45], Çelik and Kayalı [46], as well as Kurdyś-Kujawska and Sompolska-Rzechuła [47], analyzing the demand for insurance from a macro- and microeconomic perspective, consistently show that higher income, higher education level, and a specific family profile (e.g., the presence of children) increase the likelihood of having insurance. The presented study primarily focuses on psychological and cognitive factors and does not explicitly model income or wealth. However, the interpretation of the path related to “postponing decisions to the future” corresponds well with macroeconomic findings. Consumers who declare that they will “take out insurance when they are older/wealthier/more settled” constitute a specific category of people with low insurance activity here and now, despite their declared “awareness of the need.” This can be interpreted as the micro-psychological equivalent of macroeconomic observations: real demand appears only when economic and psychological conditions coincide in time.

Barrier beliefs, or negative attitudes such as “nothing will happen to me,” “insurance isn’t worth it,” or “insurance companies can’t be trusted,” are also an important area of discussion. These beliefs effectively block purchasing decisions. Research on microinsurance and emerging markets indicates that structural distrust (beliefs that the system doesn’t work for me) can inhibit demand regardless of income or objective risk exposure [48]. The presented model demonstrates that barrier beliefs not only directly influence insurance ownership but also act indirectly through perceived fit, as consumers with substantial barriers perceive the offer as less relevant. They are therefore less likely to take out insurance. Furthermore, the path of temporary decision-making (“I’ll get insurance when I’m older/earning more”) turns out to be a strong, negative predictor of insurance ownership. This is reflected in the findings of studies combining economic and psychological approaches: income and financial status are significant determinants of insurance ownership [45,46], but from a psychological perspective, postponing decisions may be a mechanism for rationalizing inaction, contributing to the broader issues of financial procrastination and low insurance penetration in lower-income groups.

The role of perceived risk and fear is also a significant area of discussion. Richter et al. [23] emphasize that insurance decisions are increasingly analyzed in light of behavioral experiments, in which the level of risk and risk aversion have a complex, not always linear, impact on individual choices. In the presented model, fear is a statistically significant factor, but a secondary one—its direct effect on insurance ownership is relatively small. This indicates that while risk awareness may be a necessary condition, it is not sufficient in itself for purchase; A sense of product value, a normative recognition of insurance as a “right choice,” and competencies in selecting offers are all necessary. It is widely accepted in the insurance literature that fear of loss, risk aversion, and awareness of the financial consequences of accidental events should favor the purchase of insurance. In a review of the determinants of demand for microinsurance, Eling et al. [48] identify, among other things, the level of risk exposure, risk aversion, and factors related to product quality and trust as key determinants of demand. Eling et al. [49] demonstrated that the propensity to take financial risk has a complex relationship with insurance ownership: individuals who are more prone to risk do not necessarily forgo policies, but may treat them as part of a broader portfolio of decisions. These results suggest that fear of accidental events is a significant, but clearly secondary, factor: their impact on actual insurance ownership is moderate and significantly weaker than the impact of normative attitudes and knowledge. This represents a significant correction to marketing intuitions, which suggest that “sufficiently scaring a customer” should automatically lead to a purchase. Fear without a sense of purpose, without trust in institutions, and without the ability to choose a product can, in practice, encourage decision-making rather than closing deals.

The literature is increasingly emphasizing the role of trust—both in financial institutions and in specific agents. The role of trust, experience, and advisors is increasingly identified as a key factor influencing insurance decisions and customer loyalty [50]. In the presented model, the “advisor role → positive experiences → insurance ownership” path confirms that not only the product itself matters, but also the quality of the relationship and the consumer’s experience with insurance. Furthermore, the perception of offer fit serves as an indirect mechanism through which barrier beliefs influence behavior, aligning with the literature on offer perception and trust [40]. In the Polish context, the literature worth reviewing is “Financial and Insurance Literacy in Poland” by Kawiński and Majewski [51], which highlights the low level of insurance knowledge among Poles and points to the need to simultaneously build competencies and improve trust, which is consistent with the message from the presented results.

Studies on insurance markets in developing countries also show that a lack of trust in a company’s solvency, the fairness of the claims settlement process, or the durability of a contract can completely “block” demand, regardless of risk and income levels (see, among others, studies published on SSRN and in journals devoted to microinsurance). In the context of more developed markets, Agyei [50] demonstrated that trust in an insurance company and its intermediary has a significant impact on customer engagement and relationship retention, extending beyond individual purchases. Similar conclusions emerge from studies on customer loyalty in insurance markets, where service quality, satisfaction, and trust shape long-term relationships and the propensity to renew policies. The presented model clearly demonstrates that positive insurance experiences and the belief in the advisor’s important role influence the number of policies held, both directly and by strengthening normative attitudes and reducing cognitive barriers. This result, therefore, aligns with the theme of trust and relationship quality: consumers who have experienced reliability and transparency are not only more likely to purchase insurance but also more likely to consider it a “normal” element of responsible behavior.

Of particular interest is the topic of barrier beliefs and how they distort market perception. Literature reviews on microinsurance and insurance in lower-income countries indicate that, alongside objective factors (income, price, availability), those above “structural distrust” is crucial—the belief that “the system is against me,” that “they’ll cheat me anyway,” and that “it’s not worth it” (see works cited on SSRN, among others). The presented results show that similar mechanisms also operate in a more developed context—individuals with strong barrier beliefs are not only less likely to buy insurance but also less likely to perceive offers as tailored to their needs. In other words, these beliefs “filter” information from the market, causing neutral or even favorable messages to be interpreted as unreliable or irrelevant. This is an important addition to the discussion on financial literacy: simply providing knowledge is not enough without parallel work to reframe deeply ingrained narratives about insurance. The obtained results are also consistent with observations regarding the specificity of the Polish insurance market. Sliwiński, Michalski, and Roszkiewicz’s research [52] on the determinants of life insurance consumption in Poland highlights the importance of economic factors, as well as the significant role of psychological factors, including perceptions of financial institutions and previous experiences with the sector. Simultaneously, analyses of Poles’ online purchasing behavior highlight the importance of trust, concerns about data security, and the need for transparency as conditions for adopting digital channels in insurance. The presented model, which emphasizes both education and positive experiences, as well as a sense of fit, fits this picture well; it shows that the growing importance of digital channels does not eliminate the need for trust and transparency, but instead reinforces it.

Finally, the presented results can be related to the extensive literature on financial and insurance literacy as a public policy objective. More recent reports and analyses indicate that countries are developing strategies to enhance financial literacy, seeing it as a tool for strengthening the stability of the financial system and household security. At the same time, studies are emerging that differentiate the impact of general and specific (insurance) literacy, demonstrating that how well consumers understand a particular product is more important than their knowledge of abstract financial concepts. The results strongly reinforce this theme: actual insurance ownership is determined not only by the level of general knowledge, but also by the practical ability to evaluate and select policies, combined with a normative attitude.

From a sustainable development perspective, the results allow for a better understanding of where insurance decisions contribute to building economic and social resilience, and where this potential remains untapped. A strong normative attitude and a high level of practical insurance knowledge support more stable and predictable financial behavior among households, which in turn translates into better protection against shocks and thus serves as the microfoundations of sustainable development. On the other hand, barrier beliefs, financial procrastination (“I’ll get insurance later”), and low trust in institutions work in the opposite direction, weakening insurance protection, increasing vulnerability to random events, and perpetuating inequalities in access to financial security. It can therefore be concluded that, from a sustainable development perspective, positive attitudes towards insurance, trust, and insurance competencies function as factors that enhance resilience and stability—both at the individual and system levels. Cognitive barriers, lack of knowledge, negative experiences, and structural distrust create “critical nodes” where the concept of sustainable development is not realized in practice, despite the availability of suitable products. The study results suggest that public policies and market strategies that simultaneously enhance insurance competencies, reduce behavioral barriers, and strengthen trust in the sector can play a crucial role in building a more resilient and, therefore, more sustainable socioeconomic system.

5. Conclusions

The presented results enable us to draw several key conclusions regarding the determinants of insurance ownership and the mechanisms that influence policy purchase decisions. In a broader perspective, they also allow us to assess the extent to which current behavioral patterns support the sustainable development of the insurance market and the financial security of households.

The central predictor of insurance behavior turned out to be an internal normative attitude—the belief that insurance is a natural, responsible, and appropriate element of life’s risk management. From a sustainable development perspective, this mechanism fosters a “culture of responsibility”—insurance becomes a sustainable and predictable element of risk management, thus strengthening the financial resilience of households and the overall stability of the system.

Consumer competence and knowledge play a significant role, both in terms of general financial literacy and more detailed product knowledge. At the same time, this knowledge works synergistically with other elements, such as trust and previous experience. From a sustainable development perspective, such an increase in insurance competence can be viewed as an investment in “resilience capital”: it limits the scale of the negative effects of random shocks and contributes to more equitable and inclusive access to insurance.

Barrier beliefs, including a lack of trust in the insurance sector or a low perception of one’s own risk, constitute a significant obstacle to purchasing insurance. This phenomenon suggests that effective insurance interventions should focus not only on education but also on building trust, transparency, and maintaining consistent service quality. At the same time, it reveals an area of “sustainable underdevelopment”: significant cognitive and emotional barriers keep some households structurally outside the insurance system, thus increasing their vulnerability to shocks and contradicting the idea of an inclusive, stable financial system.

Fear of accidental events and subjective risk perception are not the main factors influencing insurance purchasing decisions. They have a significantly weaker impact than normative attitudes and product knowledge. From a sustainable development perspective, this is a necessary correction: an insurance system focused on long-term stability cannot be based on “fear management,” but on building lasting, conscious motivations and skills—only then will market participation be stable, not reactive and episodic.

The results emphasize the importance of experience and the quality of relationships—particularly the role of the advisor, the fairness of the claims settlement process, and the transparency of communication. Positive insurance experiences strengthen both normative attitudes and the willingness to make subsequent purchase decisions. This mechanism confirms that insurance services are not treated solely as a product, but also as a relationship based on trust and a sense of security. From a sustainability perspective, such relationships constitute a kind of “soft infrastructure” for the system—they increase stability, reduce the risk of conflict and disputes, and foster long-term loyalty, which in turn strengthens both the stability of insurance portfolios and customer security.

This study demonstrates that insurance decisions are the result of a complex interaction of multiple factors—cognitive, normative, emotional, and relational—rather than a simple response to risk levels. The most important determinants of policy ownership are (1) internal liability standards, (2) product competence, (3) quality of experience, (4) lack of cognitive barriers, and (5) a sense of trust in the institution and advisor. From a sustainability perspective, these results suggest that the insurance market is in a “partially balanced” phase: strong elements promoting sustainable resilience are evident (standard of liability, the growing importance of knowledge, the role of positive experiences), but at the same time, clear barriers remain (lack of trust, underestimation of risk, postponement of decisions), which limit the full potential of insurance as a tool for socioeconomic stabilization. This approach allows for a better understanding of both the micro-psychological and market mechanisms behind the demand for insurance and indicates the directions of public policy and industry practice: the development of insurance education combining theory with practice, consistent strengthening of trust and quality of services, reductions in cognitive and emotional barriers, and support of the norm according to which insurance is one of the basic elements of sustainable, responsible functioning of households.

The results of the present research can be used by policymakers and the insurance industry. Knowledge about the factors influencing consumer purchases of insurance can be used by politicians to shape insurance policies, particularly those that provide the greatest level of safety. In turn, the insurance industry can use the research findings to tailor product offerings to customer needs and to emphasize customer information policies regarding insurance services. The limitations of the study may stem from the sample, which included Poland. When applying the study results to populations in other countries, it is important to consider, among other factors, different economic, social, and political/legal conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I. and J.M.; methodology, M.I.; validation, M.I. and J.M.; formal analysis, M.I.; investigation, M.I. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, M.I. and J.M.; visualization, J.M.; supervision, M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to Poland‘s National Science Centre Guide. Respondents were informed of the research’s purpose, how the results would be used, and their rights, including the right to withdraw at any stage. Data collected from participants is protected against unauthorized access and used solely for research purposes.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Outreville, J.F. The Relationship Between Insurance and Economic Development: 85 Empirical Papers for a Review of the Literature. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2013, 16, 71–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamtarana, K.; Sornsaruht, P. Antecedents to Thai Consumer Insurance Policy Purchase Intention: A Structural Equation Model Analysis. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241239474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maman, D.; Rosenhek, Z. Facing Future Uncertainties and Risks through Personal Finance: Conventions in Financial Education. J. Cult. Econ. 2020, 13, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yuan, X. Financial Inclusion in China: An Overview. Front. Bus. Res. China 2021, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R.; Prasad, K.; Mandal, N.; Singh, S.; Vardhan, M.; Pamucar, D. Performance Evaluation of an Insurance Company Using an Integrated Balanced Scorecard (BSC) and Best-Worst Method (BWM). Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2021, 4, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terdpaopong, K.; Rickards, R.C. Thai Non-Life Insurance Companies’ Resilience and the Historic 2011 Floods: Some Recommendations for Greater Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Mubeen, M.; Jatoi, W.N.; Tahir, M.; Ahmad, S.; Farid, H.U.; ur Rahman, M.H.; Ali, M.; Qaisrani, S.A.; Ahmad, I. Sustainable Development Goals and Governments’ Roles for Social Protection. In Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture: Concepts, Issues and Policies for Developing Countries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Xia, X.; Chen, Z. The Effect of Agricultural Insurance Participation on Rural Households’ Economic Resilience to Natural Disasters: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemkowska, M. Funkcje ubezpieczeń gospodarczych a zrównoważony rozwój. Wiadomości Ubezpieczeniowe 2020, 2, 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weedige, S.S.; Ouyang, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y. Decision Making in Personal Insurance: Impact of Insurance Literacy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnert, J.R.; Schmeiser, H.; Zehnle, M. Consumer Perceptions and Purchasing Behavior of Sustainable Insurance Products. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2025, 50, 619–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.; Ismail, N.A.; Rahman, M. A Conceptual Framework for Purchase Intention of Sustainable Life Insurance: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 14, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska-Tyszko, J.; Soliwoda, M. Agricultural insurance vs. economic and financial sustainability of farms. Pract. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2017, 478, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskas, G.; Raišienė, A.G. Reflections on the Customer Decision-Making Process in the Digital Insurance Platforms: An Empirical Study of the Baltic Market. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Lee, C.Y.; Fan, C.K. Analysis of Innovative Green Marketing Corresponding to Consumer Preferences: A Case Study of the Insurance Industry. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, P.; Ramos, R.F. Global Research Trends in Consumer Behavior and Sustainability in E-Commerce: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Knowledge Structure. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, S.; Śmigla, M. Zarządzanie ryzykiem cenowym w rolnictwie w praktyce wybranych krajów na świecie. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW W Warszawie-Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2012, 12, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, K. Do Personal Values Explain Variation in Satisficing Measures of Risk? Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 1642–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunreuther, H.; Pauly, M. Insurance Decision-Making and Market Behavior. Found. Trends® Microecon. 2006, 1, 63–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunreuther, H.C.; Pauly, M.V. Behavioral Economics and Insurance: Principles and Solutions. In Research Handbook on the Economics of Insurance Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, C.; Gatzert, N.; Schmeiser, H. How Does Price Presentation Influence Consumer Choice? The Case of Life Insurance Products. J. Risk Insur. 2015, 82, 401–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakvarelidze, A. The Impact of Behavioral Economics on Consumer Decision-Making in The Insurance Industry. Health Policy Econ. Sociol. 2024, 8, 2960–9992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Schiller, J.; Schlesinger, H. Behavioral Insurance: Theory and Experiments. J. Risk Uncertain 2014, 48, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Ruß, J.; Schelling, S. Insurance Customer Behavior: Lessons from Behavioral Economics. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2019, 22, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinnewijn, J. Insurance and Perceptions: How to Screen Optimists and Pessimists. Econ. J. 2013, 123, 606–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Bruhn, A.; William, J. Extending Financial Literacy to Insurance Literacy: A Survey Approach. Account. Financ. 2019, 59, 685–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicka, A.; Świstak, J. Homo Sapiens Oeconomicus, Komo Oeconomicus—Are Our Decisions on Insurance Are Taken on the Basis of Rational Factors Only? Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Szczecińskiego Finans. Rynk. Finans. Ubezpieczenia 2017, 89, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fezzi, C.; Menapace, L.; Raffaelli, R. Estimating Risk Preferences Integrating Insurance Choices with Subjective Beliefs. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 135, 103717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, O. Out of Time? The Effect of an Infrequent Traumatic Event on Individuals’ Time and Risk Preferences, Beliefs, and Insurance Purchasing. J. Health Econ. 2022, 86, 102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baicker, K.; Congdon, W.J.; Mullainathan, S. Health Insurance Coverage and Take-Up: Lessons from Behavioral Economics. Milbank Q. 2012, 90, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan S., S.; Iyer, S.S.; Balaji Smr, S. Insights from Behavioral Economics for Policymakers of Choice-based Health Insurance Markets: A Scoping Review. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2022, 25, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.S.; Chang, C.T.; Sia, W.Y. An Empirical Study on the Consumers’ Willingness to Insure Online. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 20, 2081–7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmadi, H.; Suk, K.S.; Meranga, I.; Samuel, S. The Influence of Attitude, Perceived Behavior Control, Subjective Norms, Sex and Age to Intention to Purchase Healthcare Insurance. J. Manag. Mark. Rev. (JMMR) 2024, 9, 2636–9168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, D.; Guariglia, A.; Fan, G.Z. Growing out of the Growing Pain’: Financial Literacy and Life Insurance Demand in China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2021, 66, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Hsiao, Y.J.; Yeh, C.Y. Financial Literacy, Financial Advisors, and Information Sources on Demand for Life Insurance. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2017, 43, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercon, S.; Gunning, J.; Zeitlin, A. The Demand for Insurance Under Limited Trust: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya. 2019. Available online: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:c59af3dd-67b8-4c10-b9b4-4536a8c5caf5/files/sqn59q4471 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Beck, T.; Webb, I. Economic, Demographic, and Institutional Determinants of Life Insurance Consumption across Countries. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2003, 17, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S.; Kayali, M.M. Determinants of Demand for Life Insurance in European Countries. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2009, 7, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdyś-Kujawska, A.; Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. Determinants of Demand for Life Insurance: The Example of Farmers from North-West Poland. Pract. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2019, 63, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, M.; Pradhan, S.; Schmit, J.T. The Determinants of Microinsurance Demand. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2014, 39, 224–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, M.; Ghavibazoo, O.; Hanewald, K. Willingness to Take Financial Risks and Insurance Holdings: A European Survey. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2021, 95, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, J.; Sun, S.; Abrokwah, E.; Penney, E.K.; Ofori-Boafo, R. Influence of Trust on Customer Engagement: Empirical Evidence from the Insurance Industry in Ghana. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019899104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawiński, M.; Majewski, P. Financial and Insurance Literacy in Poland. Wiadomości Ubezpieczeniowe 2016, 4, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski, A.; Michalski, T.; Roszkiewicz, M. Demand for Life Insurance—An Empirical Analysis in the Case of Poland. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2013, 38, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.